Introduction

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a life-saving

emergency technique used after cardiac arrest to restore

spontaneous circulation and maintain oxygenated blood flow to vital

organs, particularly the brain and heart (1). It involves chest compressions and

artificial ventilation; compressions simulate the heart's pumping

action, while ventilation supplies oxygen to the lungs (2).

Despite its importance, CPR faces challenges.

Survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests remain low, with

only 5–10% of patients surviving to hospital discharge (3). Several factors affect outcomes,

including delays in CPR initiation, the quality of compressions,

the cause of the arrest and reversible conditions such as pulmonary

embolism or myocardial infarction (4,5).

Inadequate advanced interventions and post-resuscitation care also

reduce success rates, driving ongoing efforts to enhance CPR

effectiveness and neurological outcomes (6).

Thrombolytic therapy, or fibrinolysis, uses drugs to

dissolve clots that block critical blood vessels (7). In cardiac arrest, thrombolysis

targets clots contributing to circulatory failure, such as those

from myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism (8). This strategy is well-established in

acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, where prompt clot

dissolution improves perfusion and limits tissue damage (9). Applying thrombolytics during CPR is

based on the premise that thrombotic occlusions may trigger or

worsen cardiac arrest (10). By

incorporating thrombolytic agents into CPR protocols, blood flow is

considered to be more effectively restored, thereby enhancing the

chances of successful resuscitation and improving overall outcomes

(8). However, this approach

carries bleeding risks, so its use requires careful risk-benefit

assessment.

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is a

bioengineered version of a naturally occurring enzyme that plays a

critical role in the breakdown of blood clots. rtPA converts

plasminogen, a blood protein, into plasmin, an enzyme that

dissolves fibrin clots (11). Due

to its targeted action on fibrin, rtPA is highly effective in

dissolving clots while minimizing systemic effects (12). In the context of thrombolytic

therapy for CPR, rtPA is considered one of the most promising

agents. Its efficacy has been well-documented in the treatment of

acute ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction, leading

researchers to explore its potential benefits in cardiac arrest

scenarios (13). rtPA presents

advantages over conventional TPA, including a more favorable

pharmacokinetic profile that enables faster thrombolysis, which is

crucial in cardiac arrest. Additionally, rtPA has a lower risk of

immunogenic reactions, enhancing its safety (14). The administration of rtPA during

CPR could potentially address the thrombotic component of certain

cardiac arrests, thus enhancing the likelihood of restoring

spontaneous circulation (15). The

present review aims to critically analyze the efficacy of

thrombolytic therapy, specifically focusing on the role of rtPA in

CPR. The present review evaluated the current evidence surrounding

rtPA administration during CPR, considering its effect on patient

outcomes, such as survival rates, neurological function and

long-term prognosis. By synthesizing available research findings

the present review provided insights into the potential benefits,

limitations and optimal protocols for implementing rtPA in CPR

protocols, ultimately contributing to informed decision-making and

advancements in resuscitative care strategies.

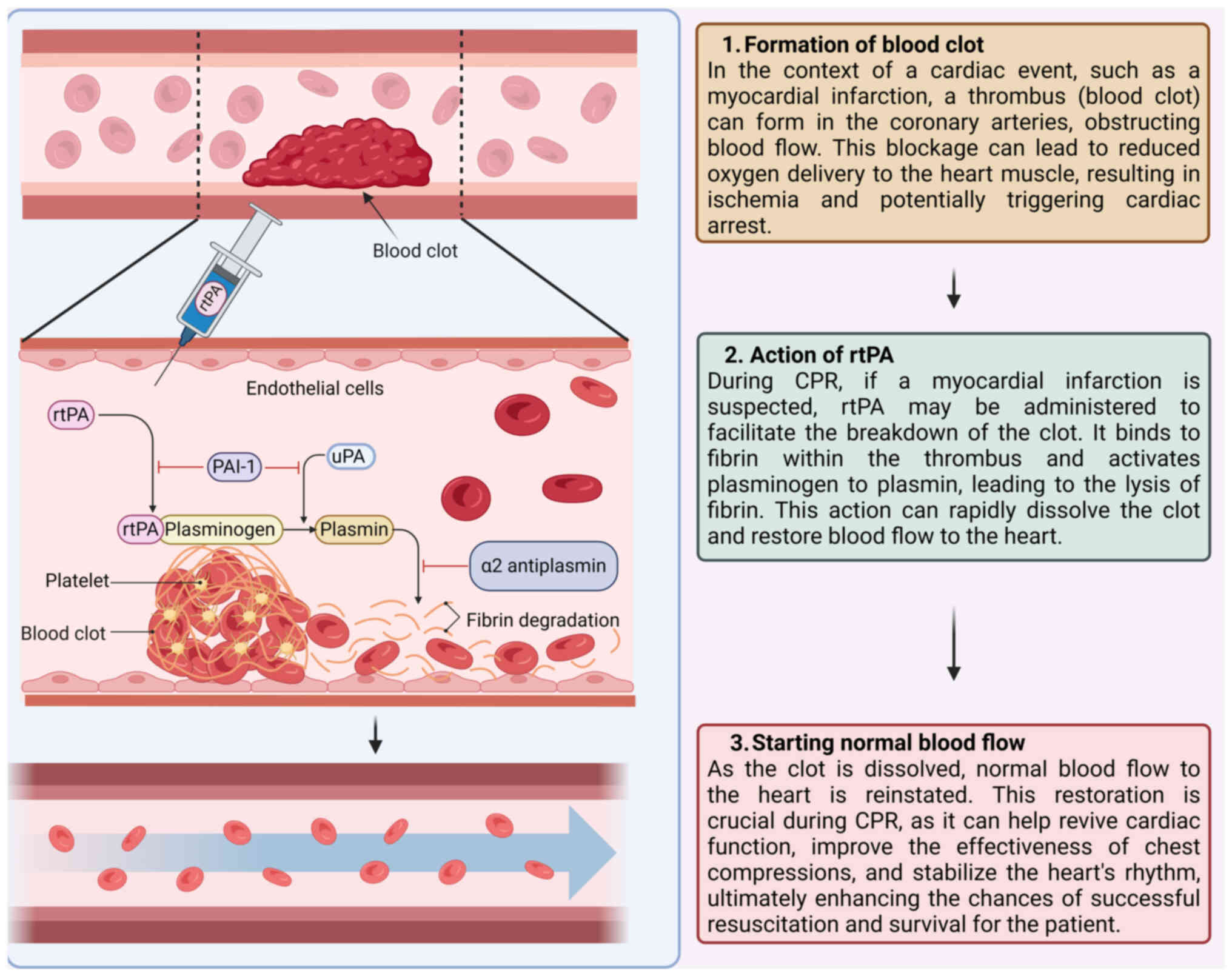

Mechanism of action of thrombolytic therapy

in CPR

The fibrinolytic pathway and clot

dissolution

The fibrinolytic pathway is a crucial biological

mechanism responsible for the breakdown of thrombi. This pathway

removes unnecessary or harmful clots, maintaining vascular patency

and normal blood flow, but it can also disrupt normal hemostasis,

increasing the risk of bleeding (16). The process begins with activating

plasminogen, a precursor glycoprotein converted into its active

form, plasmin (17). Plasmin is a

serine protease that digests fibrin, the primary protein

constituent of blood clots (18)

(Fig. 1). The fibrinolytic system

can be activated via two pathways: The intrinsic pathway, initiated

by contact with negatively charged surfaces, and the extrinsic

pathway, which is triggered by tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)

or urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) released from endothelial

cells in response to injury or stress (17,19).

In considering thrombolytic therapy, a comparative analysis of tPA

and uPA is crucial. tPA is widely preferred for its rapid action

and specificity for fibrin-bound plasminogen, making it effective

in acute ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction. However, its

use may be restricted by bleeding risks and contraindications

(20,21). Conversely, uPA, while less commonly

used, offers advantages in patients with higher bleeding risk or

contraindications to tPA and it can be effective in various

thrombotic conditions, including pulmonary embolism. A thorough

comparison of these agents can guide clinicians in making informed

decisions tailored to individual patient needs and specific

clinical scenarios (22).

The use of tPA and uPA carries inherent bleeding

risks and specific contraindications. For tPA, the reported risk of

symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is ~6.4% when

administered for acute ischemic stroke, with overall bleeding risks

reaching 10–15%. Contraindications for tPA include recent

intracranial hemorrhage, active bleeding, significant head trauma,

major surgery within the past three months and severe uncontrolled

hypertension (23). By contrast,

uPA is associated with a lower overall bleeding risk, estimated at

1–2% for major events, although its specific risk profile is less

characterized compared with tPA (24). Regarding efficacy, tPA has

demonstrated 30–35% effectiveness in achieving functional

independence in ischemic stroke patients and is effective in

myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism (25). In comparison, uPA has shown

variable efficacy rates, typically lower than tPA and is not as

widely accepted in acute stroke or myocardial infarction. tPA has

high fibrin specificity, a half-life of <5 min and is

administered via bolus and infusion over 90 min, while uPA lacks

fibrin specificity, has a half-life of 10–20 min and is given as an

infusion. The two agents have similar ICH risks, but tPA shows

higher rates of recanalization and improved long-term recovery

outcomes (26). In terms of roles

in stroke, tPA is critical for acute thrombolysis, affecting

vascular permeability and inflammation, while uPA promotes synaptic

recovery during the recovery phase. tPA disrupts the blood-brain

barrier, increasing permeability and leukocyte infiltration,

whereas uPA may enhance neovascularization (27). Overall, tPA can enhance synaptic

plasticity but may induce excitotoxicity, while uPA supports

neuronal recovery and synaptic repair. Understanding these

parameters is crucial for optimizing thrombolytic therapy and

managing associated risks effectively.

Role of rtPA in converting plasminogen

to plasmin

rtPA is a synthetic form of the naturally occurring

tPA designed for therapeutic use to enhance clot dissolution

(28). rtPA functions by binding

to fibrin within the clot and converting the adjacent plasminogen

to plasmin (29). This localized

conversion is critical as it ensures that plasmin is generated

primarily at the site of the thrombus, minimizing systemic

activation, which could lead to widespread bleeding complications

(30,31). Once administered, rtPA enhances the

conversion efficiency of plasminogen to plasmin, amplifying the

fibrinolytic activity at the site of the thrombus. This increase in

plasmin leads to the more rapid and effective breakdown of fibrin,

the structural framework of the clot. By dissolving the fibrin

mesh, rtPA facilitates the disintegration of the thrombus, thereby

restoring blood flow through the occluded vessel (32).

In comparing rTPA with conventional plasminogen

activators such as TPA, several key differences emerge that

highlight the advantages of rTPA in clinical practice. rTPA

specifically targets fibrin-bound plasminogen, which enhances

fibrinolysis directly at the site of the clot. This targeted action

increases its effectiveness in dissolving thrombi, a critical

factor in acute ischemic events (33). Furthermore, rTPA demonstrates a

more rapid onset of action compared with conventional TPA, allowing

for quicker therapeutic effects in urgent situations. This rapid

response is crucial for improving patient outcomes in acute stroke

management. The pharmacological profile of rTPA also emphasizes its

preferential action on clot-bound fibrin, which markedly boosts its

efficacy in thrombus dissolution (34). The safety profile of rTPA is more

thoroughly characterized in the literature, with studies indicating

a clearer understanding of its potential adverse drug reactions

(35). Notably, while both agents

carry a risk of bleeding, the specific safety data of rTPA provide

clinicians with more reliable information for risk assessment.

Additionally, rTPA has a shorter half-life, which is beneficial for

managing acute ischemic events, as it allows for rapid clinical

adjustments based on the patient's response (36). These distinctions not only

elucidate the pharmacological advantages of rTPA but also

underscore its role in improving therapeutic outcomes in patients

requiring acute thrombolytic therapy (37).

Potential benefits of thrombolysis in

restoring coronary and pulmonary blood flow

Thrombolytic therapy, particularly with agents such

as rtPA, holds significant potential benefits during CPR.

Thrombotic occlusions during cardiac arrest can impair coronary and

pulmonary circulation, worsening myocardial and cerebral ischemia

and lowering resuscitation success rates. By dissolving these

clots, thrombolytic therapy can restore blood flow and improve

oxygen delivery to vital organs (38). In acute myocardial infarction or

massive pulmonary embolism (PE)-induced arrest, rtPA can rapidly

dissolve the causative thrombi, reestablish coronary perfusion and

potentially convert non-perfusing rhythms, such as ventricular

fibrillation or pulseless electrical activity, into perfusing ones

(39,40). Similarly, in PE, thrombolysis can

alleviate the obstruction in the pulmonary arteries, reduce right

ventricular strain and enhance cardiac output. Restoring coronary

and pulmonary circulation during CPR can improve resuscitation

efficacy, stabilize hemodynamics and increase return of spontaneous

circulation (ROSC) rates (41).

Reducing ischemic time may also lessen post-resuscitation

myocardial dysfunction and limit ischemic damage to the heart and

other organs (42,43). Consequently, integrating

thrombolytic therapy into CPR protocols, especially in cases where

thrombotic occlusions are suspected, can be a crucial strategy to

improve survival outcomes and neurological recovery in cardiac

arrest patients (44).

Diagnosing PE and ST-elevation myocardial infarction

(STEMI) during CPR poses significant challenges for clinicians.

Rapid decision-making is crucial, often relying on clinical

history, symptoms and immediate ECG findings. In STEMI, chest pain

and ST-segment elevation guide diagnosis, while PE may present with

sudden dyspnea and hemodynamic instability (45). To confirm thrombotic causes

quickly, point-of-care ultrasound and imaging techniques such as

computed tomography pulmonary angiography are helpful, though not

always available during CPR. Clinicians may also use risk

stratification tools, such as the Wells score for PE and the TIMI

score for STEMI (38), along with

biomarkers such as cardiac troponins and D-dimer levels, to inform

their decisions regarding rtPA administration. Ultimately, timely

identification requires a high level of clinical awareness and

effective teamwork (46).

Application of thrombolytic therapy in

CPR

Clinical studies and trials evaluating

thrombolytic therapy in CPR

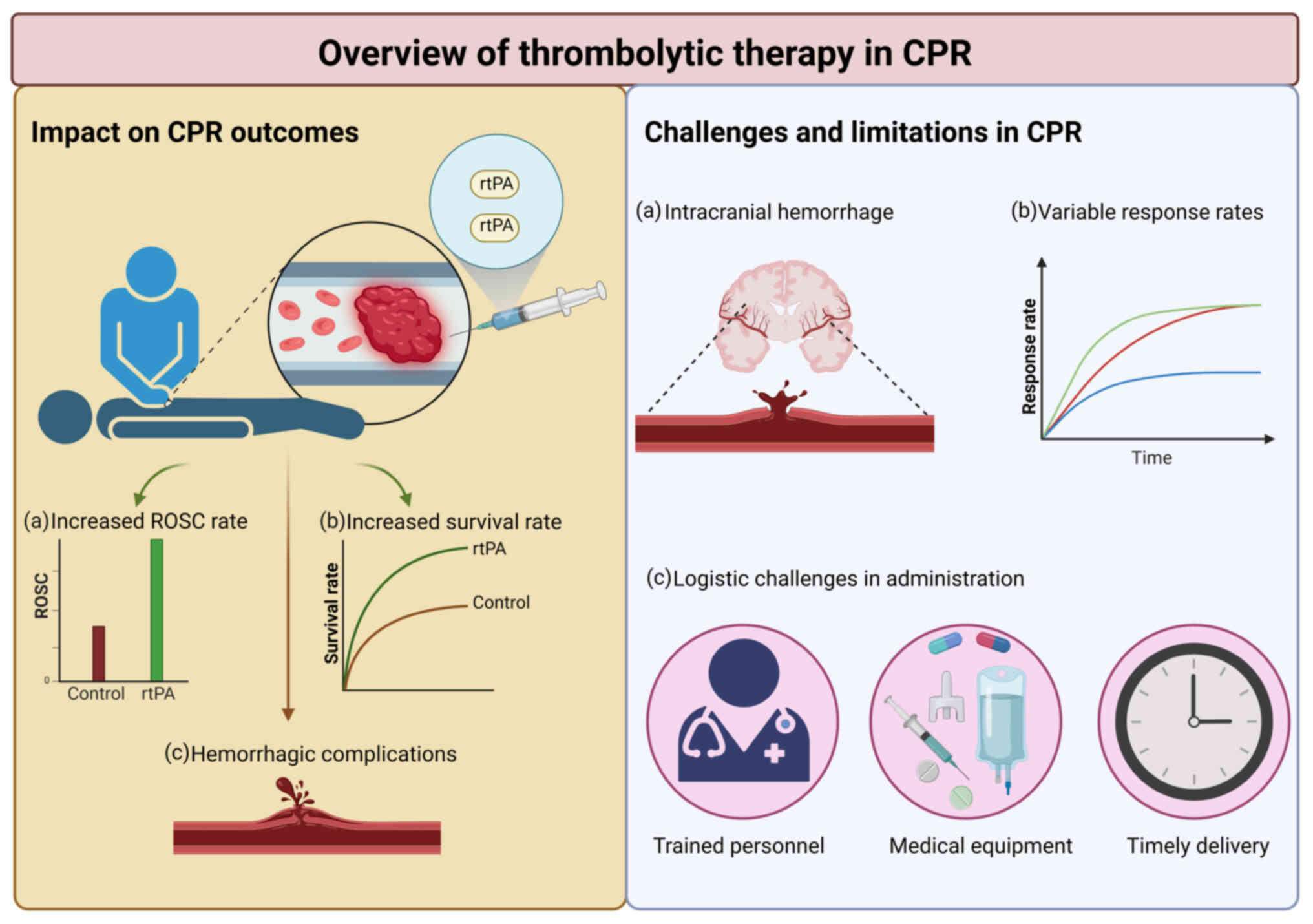

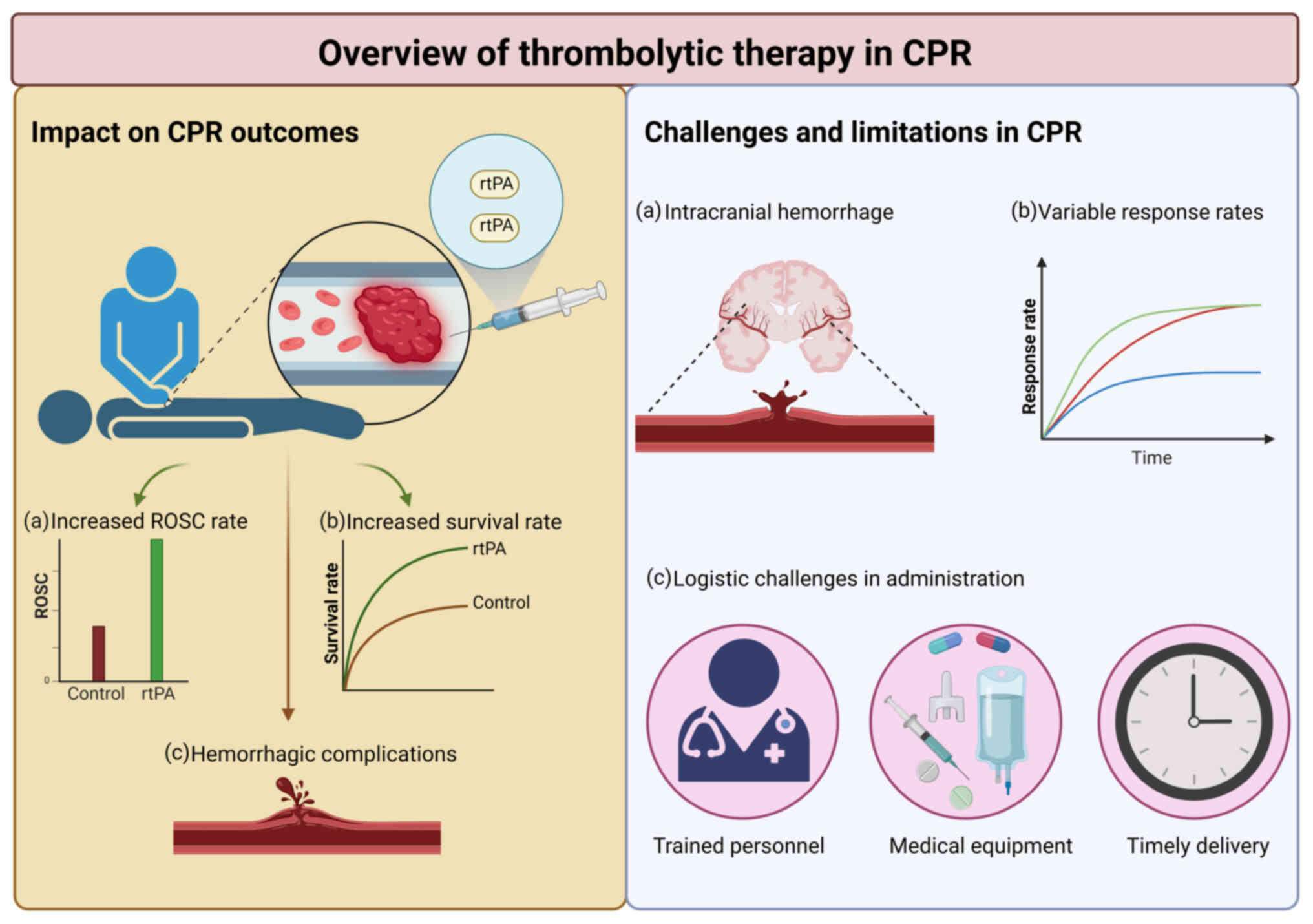

Thrombolytic therapy, particularly rtPA, has been

explored as an adjunct to standard CPR protocols in several

clinical studies and trials (Fig.

2). For instance, the TICA trial indicated that rtPA could

improve ROSC rates, with reported rates of ~35% in the rtPA group

compared with ~20% in standard CPR cases (47). However, it also raised concerns

about safety, necessitating further research on optimal dosing and

outcomes. In a study by Bozeman et al (48), the use of tenecteplase (TNK) after

failed Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) measures resulted in a

ROSC rate of 26% compared with 12.4% in the control group (P=0.04).

Additionally, 12% of TNK patients survived to admission compared

with none in the control group (P=0.0007). This study emphasized

the potential benefit of timely intervention, as TNK was given

after an average of 30 min of cardiac arrest.

| Figure 2.The potential benefits of

thrombolytic therapy, particularly rtPA, in improving rates of ROSC

during CPR are highlighted. It emphasizes observed outcomes, such

as increased ROSC rates and early survival, while also addressing

significant challenges and limitations, including the risk of

bleeding complications, variable patient responses and logistical

hurdles in therapy administration. Together, these elements

underscore the complex considerations that healthcare providers

must navigate when integrating thrombolytic therapy into CPR

protocols. Created with BioRender.com. rtPA, recombinant tissue

plasminogen activator; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation;

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. |

In a prospective study, 108 patients received rtPA

during CPR, while 216 matched controls received standard CPR

without thrombolysis. The rtPA group demonstrated markedly improved

outcomes, with ROSC achieved in 70.4% compared with 51.0% in the

control group. Additionally, 24-h survival was 48.1% in the rtPA

group compared with 32.9% in controls. Survival to hospital

discharge was also higher in the rtPA group at 25.9%, although

exact comparative data for the control group was not specified.

Among patients with presumed PE, outcomes were even more favorable:

24-h survival was 57.9% and discharge survival reached 31.6%.

Bleeding complications occurred in 5.6% of rtPA patients, including

one case of intracranial hemorrhage (0.9%), which was equal to the

ICH rate of the control group (0.9%) (30). In a retrospective study of 66

patients with CA, rtPA administered during or shortly after CPR was

associated with improved early survival outcomes compared with

standard CPR protocols. ROSC was achieved in 67% of patients in the

rtPA group compared with 43% in the standard CPR protocol group and

24-h survival was markedly higher at 53% compared with 23% in

controls. Importantly, prolonged CPR (≥10 min) did not correlate

with increased bleeding risk. The data suggest that administration

of rtPA during CPR for CA could improve ROSC and short-term

survival compared with the standard CPR protocols (49).

In another prospective study involving 90 patients

with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, 40 received rt-PA during CPR,

while 50 received standard CPR alone. Thrombolytic therapy markedly

improved clinical outcomes. ROSC occurred in 68% of rt-PA patients

compared with 44% of controls and 58% were admitted to a cardiac

intensive care unit compared with 30% of controls. Although 24-h

survival (35 vs. 22%) and hospital discharge rates (15 vs. 8%)

favored the rtPA group, these differences were not statistically

significant. Notably, no bleeding complications related to CPR were

observed. However, two rtPA patients experienced gastrointestinal

bleeding requiring transfusion, occurring 2- and 12-days

post-arrest (19). In a

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 233

patients with cardiac arrest and presumed cardiovascular etiology,

the efficacy of tPA during CPR was evaluated against standard CPR

alone. Patients were randomized to receive either tPA or placebo in

addition to standard CPR. ROSC occurred in 21.4% of the tPA group

and 23.3% of the placebo group, showing no significant benefit.

Only one patient (0.9%) in the tPA group survived to hospital

discharge, compared with none in the placebo group. Four tPA

patients survived more than 24 h post-admission, but this did not

translate into improved overall outcomes (50).

The Thrombolysis in Cardiac Arrest (TROICA) study

(51), an international

multicenter trial, evaluated the efficacy and safety of

tenecteplase during CPR for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Despite

its larger scale, TROICA found no significant improvement in

long-term survival or neurological outcomes compared with placebo.

The study reported ROSC rates of ~30% in the rtPA group compared

with 20% in the control group. Timing was critical; rtPA was

administered as soon as feasible after ROSC, typically within 30

min. However, the quality of post-resuscitation care varied, which

may have obscured the potential benefits of thrombolysis.

Furthermore, Bakkum et al (36) demonstrated that an accelerated

regimen of rtPA (0.6 mg/kg in 15 min) resulted in a trend toward

higher ROSC rates (67 compared with 43%; P=0.06) compared with no

thrombolysis in patients with pulmonary embolism-induced

circulatory arrest. Amini et al (35) investigated the efficacy and safety

of reduced doses of rtPA in patients with acute pulmonary embolism,

comparing it to standard doses and anticoagulation therapy.

Analyzing data from 13 studies, including four observational

studies with 4,223 patients and nine randomized controlled trials

involving 780 patients, the authors found that the reduced dose was

associated with a markedly lower incidence of total bleeding events

(RR 5.08; 95%CI 1.39–18.6) compared with anticoagulants.

Furthermore, when comparing standard and reduced doses of rtPA, the

standard dose showed a greater incidence of bleeding (RR 1.48;

95%CI 1.00–2.19). Importantly, there were no significant

differences in all-cause mortality or recurrence of PE between the

treatment groups, suggesting that a reduced dose of rtPA offers a

safer alternative without compromising efficacy. Doelare et

al (52) investigated the

relationship between fibrinogen levels and major bleeding risk

during catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute limb ischemia. Of

443 patients treated with rtPA, the overall incidence of major

bleeding was 7%. Patients with fibrinogen levels below 1.0 g/l had

a markedly higher bleeding rate (15 vs. 6%; P=0.041), highlighting

low fibrinogen as a critical risk factor. Additionally, high-dose

thrombolytic regimens and older age were independent predictors of

major bleeding. The TROICA study reported a lower incidence of

major bleeding complications at ~3%, attributed to careful patient

selection and monitoring (51).

The contrasting results across these studies may be attributed to

several factors, including variability in patient characteristics

(such as age or comorbidities) that may influence outcomes, as seen

in the TROICA study where patient selection criteria were stringent

(53). The timing of rtPA

administration markedly affected outcomes; studies that

administered rtPA more quickly after cardiac arrest generally

reported improved results. Additionally, differences in dosing

strategies (standard compared with accelerated or reduced doses)

could explain variations in efficacy and safety profiles observed

in different trials (54).

Finally, variability in post-resuscitation care protocols across

studies can markedly affect observed outcomes. Factors such as the

availability of advanced monitoring, therapeutic hypothermia and

comprehensive cardiac care can differ widely between institutions

and trials. Inconsistent care may obscure the potential benefits of

thrombolytic therapy, as optimal post-resuscitation management is

crucial for patient recovery and overall survival (55) (Table

I). It is important to note that neurological outcomes have not

been evaluated in most of these studies.

| Table I.Comparison of rtPA and standard CPR

protocols. |

Table I.

Comparison of rtPA and standard CPR

protocols.

| Trial or first

author/s, year | Intervention | ROSC rates | Survival rates | Key findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Böttiger et

al, 2001 | rtPA | 68 (rtPA) vs. 44%

(control) | 24 h: 35 vs. 22%;

discharge: 15 vs. 8% | rtPA improved

outcomes, but survival differences were not statistically

significant. No CPR-related bleeding; 2 GI bleeds in rtPA

group | (19) |

| Lederer et

al, 2001 | rtPA | 70.4% (rtPA) vs.

51.0% (control) | 24 h survival: 48.1

vs. 32.9%; discharge: 25.9% (rtPA); control not specified | rtPA improved ROSC

and survival. PE subgroup had even higher 24 h (57.9%) and

discharge (31.6%) survival. Bleeding: 5.6, ICH: 0.9% (same as

control) | (30) |

| Amini et al,

2021 | Reduced dose

rtPA | Not specified | No significant

differences | Reduced doses led

to fewer bleeding events without compromising efficacy | (35) |

| Bakkum et

al, 2021 | Accelerated

rtPA | 67 (accelerated)

vs. 43% (no thrombolysis) | Not specified | Higher ROSC rates

with accelerated dosing for pulmonary embolism | (36) |

| TICA trial,

2004 | rtPA | 35 (rtPA) vs. 20%

(standard CPR) | Not specified | Improved ROSC with

rtPA; raised safety concerns | (47) |

| Bozeman et

al, 2006 | Tenecteplase

(rtPA) | 26 (rtPA) vs. 12.4%

(control) | 12 (rtPA) vs. 0%

(control) | Emphasized timely

intervention; rtPA given after 30 min | (48) |

| Janata et

al, 2003 | rtPA | 67 (rtPA) vs. 43%

(control) | 24 h survival: 53

vs. 23% | rtPA improved ROSC

and 24h survival. No increased bleeding with prolonged CPR. | (49) |

| Abu-Laban et

al, 2002 | tPA | 21.4 (tPA) vs.

23.3% (placebo) | Discharge: 0.9

(tPA) vs. 0% (placebo); 4 tPA patients survived >24h | No significant

benefit of tPA. Only one discharge survivor in tPA group | (50) |

| TROICA study,

2005 | Tenecteplase

(rtPA) | 30 (rtPA) vs. 20%

(control) | No significant

improvement | No long-term

survival benefit; variability in post-resuscitation care | (51) |

| Doelare et

al, 2023 | rtPA | Not specified | Major bleeding

incidence: 7% | High fibrinogen

levels linked to increased bleeding risk | (52) |

Efficacy outcomes, rates of ROSC and

survival to hospital admission and discharge

The efficacy of thrombolytic therapy in the context

of CPR is primarily measured through rates of ROSC, survival to

hospital admission and survival to hospital discharge with

favorable neurological outcomes (56). In studies where thrombolytics were

administered, an increase in ROSC rates was often observed

(57). For instance, a

meta-analysis of several small trials indicated a statistically

significant improvement in ROSC rates when rtPA was used. However,

the effect on survival to hospital discharge remains less

definitive (58). This highlights

the need to distinguish between short-term efficacy (such as ROSC

and hospital admission) and long-term outcomes (such as survival to

discharge and neurological recovery). While some studies have

reported higher survival rates for hospital admission, these

improvements do not always translate to long-term survival or

favorable neurological outcomes (59). The TROICA trial, for example, found

no significant difference in survival to hospital discharge between

the thrombolytic and placebo groups, highlighting the complexity

and potential limitations of thrombolytic therapy in CPR. Moreover,

even when ROSC is achieved, the potential for hypoxic brain injury

and subsequent neurological impairment remains high, underlining

the importance of evaluating therapies not only for their ability

to restore circulation but also for their influence on neurological

prognosis and functional recovery (60,61).

Future studies and clinical protocols should prioritize these

distinctions to improved assess the true benefit of thrombolytic

therapy in cardiac arrest scenarios.

Comparison of outcomes between

thrombolytic therapy and standard CPR protocols

The data reveals potential benefits and notable

risks when comparing outcomes between thrombolytic therapy and

standard CPR protocols. Standard CPR protocols, which do not

include thrombolytics, have established benchmarks for ROSC and

survival rates. Thrombolytic therapy, in theory, offers an

advantage by addressing underlying thrombotic causes of cardiac

arrest, potentially enhancing coronary and cerebral perfusion

during resuscitation efforts (19). However, while some studies suggest

improved ROSC rates with thrombolytics, the overall survival to

hospital discharge and neurological outcomes do not consistently

show significant improvements over standard protocols (62). Moreover, the risk of adverse

effects, particularly hemorrhagic complications, remains a critical

concern. Bleeding risks associated with thrombolytic therapy can

offset potential benefits, especially in the context of traumatic

cardiac arrests or in patients with underlying conditions

predisposing them to hemorrhage (63).

Indications and patient selection for

thrombolytic therapy in CPR

Identification of suitable candidates

for thrombolytic treatment in CPR

Identifying suitable candidates for thrombolytic

therapy during CPR involves assessing the underlying cause of

cardiac arrest, the patient's medical history and the likelihood of

a favorable outcome from thrombolysis. Thrombolytic therapy,

particularly with rtPA, is most beneficial in cases where cardiac

arrest is due to PE, MI or other thrombotic events (64). Clinicians should prioritize

patients with witnessed arrest, a short duration of arrest before

the initiation of CPR and those without severe comorbidities

(65). The presence of risk

factors such as recent surgery, active bleeding, or a history of

hemorrhagic stroke generally contraindicates the use of

thrombolytics due to the elevated risk of bleeding complications

(44,58). If available, advanced imaging

techniques such as echocardiography or computed tomography scans

can help confirm the presence of thrombi, guiding the decision to

administer rtPA (44).

Thrombolytic therapy in CPR involves careful consideration of

various factors, including indications such as pulmonary embolism

and myocardial infarction (44),

as well as exclusion criteria like active bleeding and recent

surgery (66) (Table II). Patient selection is critical,

taking into account age, sex, and pre-existing conditions such as

carotid artery stenosis (67,68).

Administering therapy promptly can improve survival and

neurological outcomes (69,70).

This therapy should be coupled with adjunctive treatments (71), and careful monitoring (72), while adhering to established

clinical guidelines for individualized care (73).

| Table II.Overview of indications and patient

criteria for thrombolytic therapy in CPR. |

Table II.

Overview of indications and patient

criteria for thrombolytic therapy in CPR.

| First author/s,

year | Category | Details | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Javaudin et

al, 2019 | Indications | 1. Pulmonary

embolism: Suspected or confirmed massive pulmonary embolism causing

cardiac arrest. | (44) |

|

|

| 2. Myocardial

infarction: ST-elevation myocardial infarction leading to cardiac

arrest. |

|

| Page et al,

2021 | Exclusion

criteria | 1. Active internal

bleeding: contraindicated due to the risk of exacerbating

bleeding. | (66) |

|

|

| 2. Recent surgery

or trauma: Due to bleeding risk within the past 2–4 weeks. |

|

| Higgins, 2011/Blum

et al, 2019 | Patient

selection | 1. Age levels:

Males under 75 and females under 70 are often preferred for

thrombolytic therapy due to a more favorable risk-to-benefit

ratio. | (67,68) |

|

|

| 2. Sex factors: Sex

differences were observed, with more females excluded due to

clinical risk factors associated with age, such as carotid artery

stenosis and history of previous strokes. |

|

|

|

| 3. Health

conditions: Significant health conditions impacting eligibility for

thrombolytic therapy included: |

|

|

|

| • Carotid artery

stenosis: Higher exclusion rates in both males and females. |

|

|

|

| • Atrial

fibrillation: Particularly affected male patients. |

|

|

|

| • Previous stroke:

Increased likelihood of exclusion for both sexes. |

|

|

|

| 4. Time since

arrest: Best outcomes if administered within min to a few h of

arrest. |

|

| Stang, 2010/Qiao

et al, 2024 | Outcomes | 1. Survival rates:

Increased survival rates in selected patients, particularly those

with pulmonary embolism. | (69,70) |

|

|

| 2. Neurological

outcomes: Improves functional recovery and reduces post-stroke

complications, such as sleep disturbances, epilepsy, anxiety and

depression, thereby enhancing overall quality of life. |

|

| Broderick et

al, 2021 | Adjunctive

therapies | 1. Anticoagulation:

Heparin, in forms such as low molecular weight heparin or

unfractionated heparin, is used alongside Warfarin, which is

started after thrombolytic treatment to prevent re-thrombosis. | (71) |

|

|

| 2. Mechanical

support: Use devices such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

for hemodynamic support in select cases. |

|

| Kluft et al,

2017 | Monitoring and

follow-up | 1. Bleeding risks:

Continuous monitoring for bleeding complications involves clinical

assessments for signs such as bruising and unusual mucosal

bleeding, regular laboratory tests to evaluate coagulation

parameters such as activated partial thromboplastin time and

prothrombin time and event reporting to document bleeding

occurrences, categorizing them as major or minor based on

severity. | (72) |

|

|

| 2. Cardiac

function: Regular assessment of cardiac function post-therapy. |

|

| Renard et

al, 2011 | Clinical

guidelines | 1. The American

Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology

guidelines: Follow specific protocols for thrombolytic

administration in CPR. | (73) |

|

|

| 2. Individualized

care: Decisions tailored based on patient condition and

response. |

|

Considerations for timing, dosing and

administration route of rtPA

The timing of thrombolytic therapy during CPR is

crucial for its effectiveness. The administration of rtPA should

occur as early as possible after cardiac arrest, ideally within the

first few min of CPR, to maximize the chances of restoring

spontaneous circulation (74).

This approach is supported by findings from observational studies

and case series, which indicate that early administration of

thrombolytics, particularly within the first 10–15 min of arrest,

is associated with improved ROSC and neurological outcomes.

Additionally, recommendations from the European Resuscitation

Council and the American Heart Association suggest considering

thrombolytics during CPR in patients with suspected or confirmed

PE, provided that administration does not markedly delay other

resuscitative efforts (65,75–77).

The standard dosing regimen for rtPA in the context

of CPR often involves a bolus injection followed by a continuous

infusion. However, protocols may vary based on institutional

practices and patient-specific factors (54). The typical dose ranges from 50–100

mg of rtPA, administered over 15–60 min as observed in studies and

clinical guidelines addressing massive PE and cardiac arrest

management (75–77). In practice, a 50 mg bolus may be

used in out-of-hospital settings to allow rapid administration,

whereas a 100 mg infusion over 2 h is common in in-hospital PE

protocols, adapted for use during prolonged resuscitation. The

administration route is typically intravenous, but intraosseous

access can be considered if intravenous access is not readily

available. Continuous monitoring of the patient during and after

the administration is essential to manage potential complications,

such as bleeding or allergic reactions and to assess the

effectiveness of the therapy. These recommendations are

increasingly being refined through accumulating evidence from

registry data, observational cohorts and ongoing randomized

controlled trials (78–82) (Table

III).

| Table III.Factors to consider regarding the

timing, dosing and administration route of rtPA. |

Table III.

Factors to consider regarding the

timing, dosing and administration route of rtPA.

| First author/s,

year | Factor | Key

considerations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Nadkarni et

al, 2006 | Timing | Early

administration: Best outcomes observed when administered within

3–4.5 h of symptom onset. | (80) |

|

|

| Delayed treatment:

Reduced efficacy and increased risk of complications beyond 4.5

h. |

|

|

|

| Extended window:

Some guidelines suggest up to 6 h in specific cases with advanced

imaging. |

|

|

|

| Monitoring:

Continuous assessment of symptoms and contraindications. |

|

| Nolan et al,

2007 | Dosing | Standard dose:

Typically, 0.9 mg/kg body weight, with a maximum dose of 90

mg. | (81) |

|

|

| Initial bolus: 10%

of the total dose given as an initial intravenous bolus over 1

min. |

|

|

|

| Infusion: Remaining

90% infused over 60 min. |

|

|

|

| Adjustments: Dose

adjustments may be necessary for patients with renal or hepatic

impairment or extreme body weight. |

|

|

|

| Pediatric

considerations: Different dosing strategies are required, not well

established for children. |

|

| Miyazaki et

al, 2019 | Administration

route | IV: Standard and

most commonly used route for administration. IA: Used in cases

where IV administration is contraindicated or unsuc cessful, often

combined with mechanical thrombectomy. | (82) |

|

|

| Combination

therapy: IV rtPA followed by IA intervention in selected cases for

improved outcomes. |

|

|

|

| Site of

administration: Ensure proper venous access and infusion monitoring

to prevent extravasation and complications. |

|

|

|

| Alternative routes:

Investigational studies on novel administration routes (such as

intraosseous) for specific clinical scenarios. |

|

Contraindications and potential risks

associated with thrombolytic therapy in CPR

Thrombolytic therapy during CPR carries significant

risks, which necessitate careful consideration of contraindications

(51). Absolute contraindications

include active internal bleeding, a history of intracranial

hemorrhage, recent major surgery or trauma, known bleeding

disorders and severe uncontrolled hypertension (83–85).

Relative contraindications, which require a risk-benefit analysis,

include recent gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer disease and

pregnancy (86). The most

significant potential risk of thrombolytic therapy is hemorrhage,

including intracranial hemorrhage, which can lead to devastating

outcomes (87). Other risks

include reperfusion arrhythmias, allergic reactions and an

increased risk of further thrombotic events in certain conditions

(88).

The decision to use rtPA during CPR must balance

these risks against the potential for improved survival and

neurological outcomes, particularly in patients with a high

likelihood of thrombotic cardiac arrest etiology. This

decision-making process often depends not only on patient-specific

factors but also on the availability of institutional protocols,

access to rapid diagnostic imaging and multidisciplinary team input

(89,90). In emergency settings, bedside tools

such as focused cardiac ultrasound can assist in identifying

possible thrombotic causes (such as massive PE), providing a

rationale for thrombolytic administration even when formal imaging

is not feasible (91).

Furthermore, institutions with predefined algorithms for cardiac

arrest management that include thrombolytic therapy in select cases

help streamline decision-making and reduce hesitation during

critical moments (92,93). Comprehensive patient assessment and

adherence to established guidelines are essential to optimizing the

benefits of thrombolytic therapy while minimizing its risks

(29). Ultimately, a tailored

approach that integrates clinical judgment, real-time diagnostics

and institutional capabilities is crucial in determining the

appropriateness of rtPA during CPR.

Challenges and limitations of thrombolytic

therapy in CPR

While promising in specific scenarios, thrombolytic

therapy poses medical and logistical challenges when used during

CPR. These issues encompass medical and logistical aspects, which

must be carefully addressed to utilize thrombolytic agents such as

rtPA effectively. This section outlines key limitations, including

bleeding risks, inconsistent efficacy and difficulties with timely

administration in diverse settings (94,95).

Bleeding complications

A primary concern with thrombolytic therapy in CPR

is the increased risk of bleeding, particularly intracranial

hemorrhage (96). While the goal

is to dissolve obstructive coronary clots and restore myocardial

blood flow, this benefit comes with a higher risk of bleeding,

especially in critical areas such as the brain (49,97).

The delicate balance between thrombolysis and hemorrhage must be

meticulously managed, as any imbalance can lead to catastrophic

outcomes (49). Moreover, CPR

patients often have impaired clotting due to pre-existing

conditions or prior treatments, further heightening bleeding risks

(98).

Variable response rates and

effectiveness

Response to thrombolytic therapy during CPR varies

markedly among patients (99).

While some patients may exhibit a robust response to thrombolytic

agents, experiencing rapid clot dissolution and successful

resuscitation, others may demonstrate limited or no response

despite timely administration (69,100). This variability stems from

multiple factors, including the cause of cardiac arrest, the degree

of vessel occlusion and individual patient characteristics such as

age, comorbidities and coagulation status. As a result, identifying

patients most likely to benefit remains a challenge and calls for

more personalized and evidence-based approaches (67).

Logistic challenges in administering

thrombolytic therapy

Besides clinical concerns, logistical barriers

hinder effective thrombolytic administration during CPR,

particularly in pre-hospital and in-hospital environments (101,102). Unlike standard CPR interventions,

thrombolytic therapy requires trained personnel, specialized

equipment and infrastructure (103,104). In pre-hospital care, EMS teams

must be trained in thrombolysis and the required drugs and

monitoring tools must be readily available en route. In hospitals,

issues such as drug storage, preparation and protocol adherence can

delay timely administration (64,73).

Addressing these challenges demands standardized protocols,

cross-disciplinary teamwork and ongoing system improvements.

Future directions and research

perspectives

Optimization of thrombolytic therapy

protocols in CPR

As CPR methods evolve, research is focusing on

refining thrombolytic therapy, especially regarding timing, dosage

and delivery of agents such as rtPA. Ongoing studies explore how

patient-specific factors, including comorbidities and arrest

etiology, can inform protocol adjustments (78,105). There is also growing interest in

personalized medicine approaches that tailor thrombolytic regimens

to individual biomarker profiles. This could maximize therapeutic

efficacy while minimizing adverse outcomes such as bleeding.

Collaborative research across clinical and industry sectors aims to

integrate thrombolysis more effectively into ACLS frameworks.

Exploration of novel thrombolytic

agents and delivery methods

In parallel with efforts to optimize existing

thrombolytic agents, researchers are exploring novel agents and

delivery methods to enhance the efficacy and safety of thrombolytic

therapy in CPR. Novel thrombolytic agents, such as modified

variants of rtPA or entirely new classes of thrombolytic drugs, are

being investigated for their potential to improve clot dissolution

kinetics and reduce the risk of reperfusion injury (106). Furthermore, advancements in drug

delivery technologies enable targeted and controlled delivery of

thrombolytic agents to the site of vascular occlusion, thereby

minimizing systemic exposure and off-target effects.

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems, microneedle patches and

catheter-based delivery platforms are among the innovative

approaches being explored to optimize the delivery of thrombolytic

therapy during CPR (107).

Integration of thrombolytic therapy

with other resuscitative interventions

As the complexity of resuscitative interventions

continues to expand, there is growing interest in integrating

thrombolytic therapy with other advanced techniques, such as

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), to improve outcomes in

refractory cardiac arrest cases. ECMO provides temporary

cardiopulmonary support by oxygenating blood outside the body,

allowing for prolonged resuscitative efforts and stabilization of

patients with profound hemodynamic instability (108). Research endeavors are underway to

elucidate the optimal strategies for combining thrombolytic therapy

with ECMO in the management of cardiac arrest patients with

suspected or confirmed pulmonary embolism or massive myocardial

infarction (109). By

synergistically addressing both the underlying cause of cardiac

arrest (such as acute coronary syndrome and pulmonary embolism) and

the resultant hemodynamic collapse, the integration of thrombolytic

therapy with ECMO holds promise for improving survival and

neurological outcomes in select patient populations (110). Moreover, ongoing studies are

investigating the potential synergistic effects of combining

thrombolytic therapy with other advanced resuscitative

interventions, such as targeted temperature management and

mechanical circulatory support devices, to optimize outcomes in

refractory cardiac arrest cases further (111). Through interdisciplinary

collaboration and rigorous clinical research, these integrated

approaches aim to redefine the standard of care for patients in

cardiac arrest, ultimately improving survival rates and

neurological recovery.

Ethical and legal considerations

Ethical implications of administering

thrombolytic therapy

Using thrombolytics during CPR involves complex

ethical issues related to autonomy, benefit, harm and resource

fairness. In emergencies, informed consent is often not feasible,

raising concerns about respecting patient autonomy while aiming to

save lives (112). The risk of

adverse effects, especially bleeding, must be weighed against the

potential benefit of restoring circulation. Additionally, the

uneven availability of thrombolytic therapy across healthcare

settings raises questions of equity and access. Clinicians must

carefully navigate these ethical concerns within

resource-constrained environments (113).

Legal issues surrounding informed

consent, liability and documentation

Legally, thrombolytic use during CPR touches on

informed consent, liability and documentation. Given the urgency of

CPR, formal consent may not always be possible, but providers

should communicate risks and alternatives whenever feasible

(114). Failing to inform or

document appropriately could result in legal consequences,

including malpractice claims. Comprehensive documentation of

treatment rationale, consent discussions (if possible) and patient

responses is vital to protect both patients and clinicians

(115).

Clear guidelines and protocols for the

use of thrombolytic therapy in CPR

Clear guidelines and protocols are paramount for the

safe and effective use of thrombolytic therapy in CPR. These

guidelines offer healthcare providers with standardized procedures

for patient assessment, medication administration and monitoring

during resuscitative efforts (65). Guidelines help ensure practice

consistency, reduce care variability and promote patient safety.

They outline criteria for patient selection, dosing regimens and

monitoring parameters to minimize the risk of adverse events

associated with thrombolytic therapy. Additionally, clear protocols

aid in informed decision-making and facilitate communication among

healthcare team members (116).

They provide a framework for addressing ethical dilemmas, such as

determining futility or prioritizing resources in resource-limited

settings. Regular review and updates of guidelines and protocols

are essential to incorporate new evidence and best practices. This

iterative process helps healthcare institutions adapt to

advancements in medical knowledge and technology, ultimately

improving patient outcomes in the challenging context of CPR.

Conclusion

The present review provided compelling evidence

supporting the efficacy of thrombolytic therapy, specifically rtPA,

in improving outcomes for patients undergoing CPR. The

administration of rtPA has been shown to increase the likelihood of

ROSC and favorable neurological outcomes. However, it is imperative

to carefully consider the potential risks, including hemorrhagic

complications. Future research should focus on refining patient

selection criteria, optimizing dosing regimens and identifying

ideal timing for rtPA administration to maximize benefit and

minimize adverse events. Additionally, large-scale randomized

controlled trials are needed to further elucidate the role of

thrombolytic therapy in specific patient populations, such as those

with acute myocardial infarction or stroke. By integrating

evidence-based guidelines and protocols, healthcare providers can

harness the potential of thrombolytic therapy to markedly improve

patient survival and quality of life following cardiac arrest.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Jilin Provincial Health and

Health Commission (grant no. 2022LC038).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and

design. Original draft preparation was conducted by WZ, YP and JD.

Writing, reviewing and editing of the draft manuscript was

completed by WZ, YP, DX and WW. In addition, WW supervised the

writing, analyses and revision of the manuscript. All authors

commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Professor Wenhai Wang

ORCID: 0009-0002-3879-4259

References

|

1

|

Riggs M, Franklin R and Saylany L:

Associations between cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge,

self-efficacy, training history and willingness to perform CPR and

CPR psychomotor skills: A systematic review. Resuscitation.

138:259–272. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang Z, Zhai ZG, Liang LR, Liu FF, Yang

YH and Wang C: Lower dosage of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen

activator (rt-PA) in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 133:357–363. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Monsieurs KG, Nolan JP, Bossaert LL, Greif

R, Maconochie IK, Nikolaou NI, Perkins GD, Soar J, Truhlář A,

Wyllie J, et al: European resuscitation council guidelines for

resuscitation 2015: Section 1. Executive summary. Resuscitation.

95:1–80. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Taffet GE, Teasdale TA and Luchi RJ:

In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA. 260:2069–2072.

1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kamali MJ, Salehi M and Fath MK: Advancing

personalized immunotherapy for melanoma: Integrating

immunoinformatics in multi-epitope vaccine development, neoantigen

identification via NGS, and immune simulation evaluation. Comput

Biol Med. 188:1098852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C,

Bueno H, Geersing GJ, Harjola VP, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Jennings

CS, Jiménez D, et al: 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and

management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration

with the European respiratory society (ERS) the task force for the

diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the

European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 41:543–603.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gilbert CR, Wilshire CL, Chang SC and

Gorden JA: The use of intrapleural thrombolytic or fibrinolytic

therapy, or both, via indwelling tunneled pleural catheters with or

without concurrent anticoagulation use. Chest. 160:776–783. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, Beyth R,

Clark NP, Cuker A, Hutten BA, Jaff MR, Manja V, Schulman S, et al:

American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of

venous thromboembolism: Treatment of deep vein thrombosis and

pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. 4:4693–4738. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Altaf F, Wu S and Kasim V: Role of

fibrinolytic enzymes in anti-thrombosis therapy. Front Mol Biosci.

8:6803972021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Grines CL, Serruys P and O'Neill WW:

Fibrinolytic therapy: Is it a treatment of the past? Circulation.

107:2538–2542. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang S, Wang D and Li L: Recombinant

tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) effectively restores

neurological function and improves prognosis in acute ischemic

stroke. Am J Transl Res. 15:34602023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Leal Rato M, Diógenes MJ and Sebastião A:

Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of stroke therapy. Precision

Medicine in Stroke. Springer Nature; pp. 41–69. 2021, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Marko M, Posekany A, Szabo S, Scharer S,

Kiechl S, Knoflach M, Serles W, Ferrari J, Lang W, Sommer P, et al:

Trends of r-tPA (recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator)

treatment and treatment-influencing factors in acute ischemic

stroke. Stroke. 51:1240–1247. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Llucià-Carol L, Muiño E, Gallego-Fabrega

C, Cárcel-Márquez J, Martín-Campos J, Lledós M, Cullell N and

Fernández-Cadenas I: Pharmacogenetics studies in stroke patients

treated with rtPA: A review of the most interesting findings.

Pharmacogenomics. 22:1091–1097. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Peppard SR, Parks AM and Zimmerman J:

Characterization of alteplase therapy for presumed or confirmed

pulmonary embolism during cardiac arrest. Am J Health Syst Pharm.

75:870–875. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kotb E: The biotechnological potential of

fibrinolytic enzymes in the dissolution of endogenous blood

thrombi. Biotechnol Prog. 30:656–672. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sharifi M, Berger J, Beeston P, Bay C,

Vajo Z and Javadpoor S; ‘PEAPETT’ investigators, : Pulseless

electrical activity in pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis

(from the ‘PEAPETT’ study). Am J Emerg Med. 34:1963–1967. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dejouvencel T, Doeuvre L, Lacroix R,

Plawinski L, Dignat-George F, Lijnen HR and Anglés-Cano E:

Fibrinolytic cross-talk: A new mechanism for plasmin formation.

Blood. 115:2048–2056. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Böttiger BW, Bode C, Kern S, Gries A, Gust

R, Glätzer R, Bauer H, Motsch J and Martin E: Efficacy and safety

of thrombolytic therapy after initially unsuccessful

cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A prospective clinical trial.

Lancet. 357:1583–1585. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Iyer A, Zurolo E, Boer K, Baayen J,

Giangaspero F, Arcella A, Di Gennaro GC, Esposito V, Spliet WG, van

Rijen PC, et al: Tissue plasminogen activator and urokinase

plasminogen activator in human epileptogenic pathologies.

Neuroscience. 167:929–945. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Badimon L, Padró T and Vilahur G:

Atherosclerosis, platelets and thrombosis in acute ischaemic heart

disease. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 1:60–74.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yepes M: The uPA/uPAR system in astrocytic

wound healing. Neural Regen Res. 17:2404–2406. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang B, Leung L, Su EJ and Lawrence DA:

PA system in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 45:600–608. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kadir RRA and Bayraktutan U: Urokinase

plasminogen activator: A potential thrombolytic agent for ischaemic

stroke. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 40:347–355. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, Blackwell L,

Albers G, Bluhmki E, Brott T, Cohen G, Davis S, Donnan G, et al:

Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects

of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic

stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised

trials. Lancet. 384:1929–1935. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Katsanos AH, Psychogios K, Turc G, Sacco

S, de Sousa DA, De Marchis GM, Palaiodimou L, Filippou DK, Ahmed N,

Sarraj A, et al: Off-label use of tenecteplase for the treatment of

acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA

Netw Open. 5:e2245062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fredriksson L, Lawrence DA and Medcalf RL:

tPA modulation of the blood-brain barrier: A unifying explanation

for the pleiotropic effects of tPA in the CNS. Semin Thromb Hemost.

43:154–168. 2017.

|

|

28

|

Katz JM and Tadi P: Physiology,

plasminogen activation. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island:

2019

|

|

29

|

Gurman P, Miranda O, Nathan A, Washington

C, Rosen Y and Elman N: Recombinant tissue plasminogen activators

(rtPA): A review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 97:274–285. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lederer W, Lichtenberger C, Pechlaner C,

Kroesen G and Baubin M: Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in 108 patients with

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 50:71–76. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sabermoghadam R, Shahmahmood TM, Sarvghadi

P and Toosi MB: The gross, fine, and oral motor functions in a

patient with megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical

cyst: A case report. Iran J Child Neurol. 17:149–161. 2023.

|

|

32

|

Hasanoğlu H, Hezer H, Karalezli A, Argüder

E, Kiliç H, Şentürk A, Er M and Soytürk AN: Half-dose recombinant

tissue plasminogen activator treatment in venous thromboembolism. J

Investig Med. 62:71–77. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang X, Li X, Xu Y, Li R, Yang Q, Zhao Y,

Wang F, Sheng B, Wang R, Chen S, et al: Effectiveness of

intravenous r-tPA versus UK for acute ischaemic stroke: A

nationwide prospective Chinese registry study. Stroke Vasc Neurol.

6:603–609. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li BH, Wang JH, Wang H, Wang DZ, Yang S,

Guo FQ and Yu NW: Different doses of intravenous tissue-type

plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: A network

meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 13:8842672022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Amini S, Bakhshandeh H, Mosaed R, Abtahi

H, Sadeghi K and Mojtahedzadeh M: Efficacy and safety of different

dosage of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) in

the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Iran J Pharm Res. 20:441–454. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bakkum MJ, Schouten VL, Smulders YM,

Nossent EJ, van Agtmael MA and Tuinman PR: Accelerated treatment

with rtPA for pulmonary embolism induced circulatory arrest. Thromb

Res. 203:74–80. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhong K, An X, Kong Y and Chen Z:

Predictive model for the risk of hemorrhagic transformation after

rt-PA intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic

stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurol

Neurosurg. 239:1082252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hezer H, Kiliç H, Abuzaina O, Hasanoğlu HC

and Karalezli A: Long-term results of low-dose tissue plasminogen

activator therapy in acute pulmonary embolism. J Investig Med.

67:1142–1147. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ucar EY, Araz O, Kerget B, Yilmaz N, Akgun

M and Saglam L: Comparison of long-term outcomes of 50 and 100 mg

rt-PA in the management of acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Clin

Respir J. 12:1628–1634. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Salehi M, Kamali MJ, Ashuori Z, Ghadimi F,

Shafiee M, Babaei S and Moghadam AA: Functional significance of

tRNA-derived fragments in sustained proliferation of tumor cells.

Gene Rep. 35:1019012024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Le Conte P, Huchet L, Trewick D, Longo C,

Vial I, Batard E, Yatim D, Touzé MD and Baron D: Efficacy of

alteplase thrombolysis for ED treatment of pulmonary embolism with

shock. Ame J Emerg Med. 21:438–440. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Cokkinos P: Post-resuscitation care:

Current therapeutic concepts. Acute Card Care. 11:131–137. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Herlitz J, Castren M, Friberg H, Nolan J,

Skrifvars M, Sunde K and Steen PA: Post resuscitation care: What

are the therapeutic alternatives and what do we know?

Resuscitation. 69:15–22. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Javaudin F, Lascarrou JB, Le Bastard Q,

Bourry Q, Latour C, De Carvalho H, Le Conte P, Escutnaire J, Hubert

H, Montassier E, et al: Thrombolysis during resuscitation for

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest caused by pulmonary embolism

increases 30-day survival: Findings from the French National

Cardiac Arrest Registry. Chest. 156:1167–1175. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Dasa O, Ruzieh M, Ammari Z, Syed MA,

Brickman KR and Gupta R: It's a ST-elevation myocardial infarction

(STEMI), or is it? Massive pulmonary embolism presenting as STEMI.

J Emerg Med. 55:125–127. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Villablanca PA, Vlismas PP, Aleksandrovich

T, Omondi A, Gupta T, Briceno DF, Garcia MJ and Wiley J: Case

report and systematic review of pulmonary embolism mimicking

ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Vascular. 27:90–97. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Fatovich DM, Dobb GJ and Clugston RA: A

pilot randomised trial of thrombolysis in cardiac arrest (The TICA

trial). Resuscitation. 61:309–313. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bozeman WP, Kleiner DM and Ferguson KL:

Empiric tenecteplase is associated with increased return of

spontaneous circulation and short term survival in cardiac arrest

patients unresponsive to standard interventions. Resuscitation.

69:399–406. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Janata K, Holzer M, Kürkciyan I, Losert H,

Riedmüller E, Pikula B, Laggner AN and Laczika K: Major bleeding

complications in cardiopulmonary resuscitation: The place of

thrombolytic therapy in cardiac arrest due to massive pulmonary

embolism. Resuscitation. 57:49–55. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Abu-Laban RB, Christenson JM, Innes GD,

van Beek CA, Wanger KP, McKnight RD, MacPhail IA, Puskaric J,

Sadowski RP, Singer J, et al: Tissue plasminogen activator in

cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity. N Engl J Med.

346:1522–1528. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Spöhr F, Arntz HR, Bluhmki E, Bode C,

Carli P, Chamberlain D, Danays T, Poth J, Skamira C, Wenzel V and

Böttiger BW: International multicentre trial protocol to assess the

efficacy and safety of tenecteplase during cardiopulmonary

resuscitation in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: The

thrombolysis in cardiac arrest (TROICA) study. Eur J Clin Invest.

35:315–323. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Doelare SA, Oukrich S, Ergin K, Jongkind

V, Wiersema AM, Lely RJ, Ebben HP, Yeung KK and Hoksbergen AWJ:

Collaborators: Major bleeding during thrombolytic therapy for acute

lower limb ischaemia: Value of laboratory tests for clinical

decision making, 17 years of experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.

65:398–404. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Pereira R, Bowen M, Rapezzano G, Redpath

A, Pratt S and Hallowell G: Use of recombinant tissue plasminogen

activator (rTPA) for treatment of fibrin in the anterior chamber of

the horse. Vet Med Sci. 10:e14482024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Vandebroek AC, Rickmann A, Boden KT, Seitz

B, Szurman P and Schulz A: Thrombolytic activity of recombinant

tissue-type plasminogen activator (rtPA) in in-vitro model for

subretinal hemorrhages. Int Ophthalmol. 45:1642025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Li X, Chen Y, Dong Z, Zhang F, Chen P and

Zhang P: A study of the safety and efficacy of multi-mode

NMR-guided double-antiplatelet pretreatment combined with low-dose

rtPA in the treatment of acute mild ischemic stroke. Front Neurol.

16:14820782025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Oh TK, Park YM, Do SH, Hwang JW and Song

IA: ROSC rates and live discharge rates after cardiopulmonary

resuscitation by different CPR teams-a retrospective cohort study.

BMC Anesthesiol. 17:1–9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Gräsner JT, Wnent J, Herlitz J, Perkins

GD, Lefering R, Tjelmeland I, Koster RW, Masterson S, Rossell-Ortiz

F, Maurer H, et al: Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

in Europe-Results of the EuReCa TWO study. Resuscitation.

148:218–226. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Wang Y, Wang M, Ni Y, Liang B and Liang Z:

Can systemic thrombolysis improve prognosis of cardiac arrest

patients during cardiopulmonary resuscitation? A systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Emerg Med. 57:478–487. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Nolan JP, Soar J, Smith GB, Gwinnutt C,

Parrott F, Power S, Harrison DA, Nixon E and Rowan K; National

Cardiac Arrest Audit, : Incidence and outcome of in-hospital

cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom National Cardiac Arrest audit.

Resuscitation. 85:987–992. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Hoiland RL, Ainslie PN, Wellington CL,

Cooper J, Stukas S, Thiara S, Foster D, Fergusson NA, Conway EM,

Menon DK, et al: Brain hypoxia is associated with neuroglial injury

in humans post-cardiac arrest. Circ Res. 129:583–597. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Hoiland RL, Robba C, Menon DK, Citerio G,

Sandroni C and Sekhon MS: Clinical targeting of the cerebral oxygen

cascade to improve brain oxygenation in patients with

hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury after cardiac arrest. Intensive Care

Med. 49:1062–1078. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, Donnino

MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, Kudenchuk PJ, Kurz MC, Lavonas EJ,

Morley PT, et al: Part 3: Adult basic and advanced life support:

2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary

resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 142

(16_Suppl_2):S366–S468. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Soar J, Böttiger BW, Carli P, Couper K,

Deakin CD, Djärv T, Lott C, Olasveengen T, Paal P, Pellis T, et al:

European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: Adult advanced life

support. Resuscitation. 161:115–151. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Stadlbauer KH, Krismer AC, Arntz HR, Mayr

VD, Lienhart HG, Böttiger BW, Jahn B, Lindner KH and Wenzel V:

Effects of thrombolysis during out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary

resuscitation. Am J Cardiol. 97:305–308. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Lott C, Truhlář A, Alfonzo A, Barelli A,

González-Salvado V, Hinkelbein J, Nolan JP, Paal P, Perkins GD,

Thies KC, et al: European resuscitation council guidelines 2021:

Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation.

161:152–219. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372:n712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Higgins J, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P,

Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L and SterneJA C;

Cochrane Bias Methods GroupCochrane Statistical Methods Group, :

The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in

randomised trials. BMJ. 343:d59282011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Blum B, Wormack L, Holtel M, Penwell A,

Lari S, Walker B and Nathaniel TI: Gender and thrombolysis therapy

in stroke patients with incidence of dyslipidemia. BMC Womens

Health. 19:112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Stang A: Critical evaluation of the

Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of

nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol.

25:603–605. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Qiao Y, Wang J, Nguyen T, Liu L, Ji X and

Zhao W: Intravenous thrombolysis with urokinase for acute ischemic

stroke. Brain Sci. 14:9892024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Broderick C, Watson L and Armon MP:

Thrombolytic strategies versus standard anticoagulation for acute

deep vein thrombosis of the lower limb. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

1:CD0027832021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Kluft C, Sidelmann JJ and Gram JB:

Assessing safety of thrombolytic therapy. Semin Thromb Hemost.

43:300–310. 2017.

|

|

73

|

Renard A, Verret C, Jost D, Meynard JB,

Tricehreau J, Hersan O, Fontaine D, Briche F, Benner P, de

Stabenrath O, et al: Impact of fibrinolysis on immediate prognosis

of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Thromb

Thrombolysis. 32:405–409. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Wardlaw JM, Koumellis P and Liu M:

Thrombolysis (different doses, routes of administration and agents)

for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

31:CD0005142013.

|

|

75

|

Ramaswamy VV, Abiramalatha T, Weiner GM

and Trevisanuto D: A comparative evaluation and appraisal of 2020

American Heart Association and 2021 European Resuscitation Council

neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Resuscitation. 167:151–159.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Semeraro F, Greif R, Böttiger BW, Burkart

R, Cimpoesu D, Georgiou M, Yeung J, Lippert F, Lockey AS,

Olasveengen TM, et al: European resuscitation council guidelines

2021: Systems saving lives. Resuscitation. 161:80–97. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, Cariou

A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert

VRM, et al: European resuscitation council and European society of

intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care.

Resuscitation. 161:220–269. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Yousuf T, Brinton T, Ahmed K, Iskander J,

Woznicka D, Kramer J, Kopiec A, Chadaga AR and Ortiz K: Tissue

plasminogen activator use in cardiac arrest secondary to fulminant

pulmonary embolism. J Clin Med Res. 8:190–195. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Sobala R, Kibbler J, Yip K, Thompson R,

Rafique C, Steward M, Samanta R; INSPIRE ERUPT collaborators, ; Jha

A, Rahman N and De Soyza A: Evaluation of Real-world use of

pulmonary embolism thrombolysis (ERUPT). ERJ Open Res.

11:00935–2024. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, Carey

SM, Kaye W, Mancini ME, Nichol G, Lane-Truitt T, Potts J, Ornato

JP, et al: First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from

in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA.

295:50–57. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Nolan J, Laver S, Welch C, Harrison D,

Gupta V and Rowan K: Outcome following admission to UK intensive

care units after cardiac arrest: A secondary analysis of the ICNARC

case mix programme database. Anaesthesia. 62:1207–1216. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Miyazaki K, Hikone M, Kuwahara Y, Ishida

T, Sugiyama K and Hamabe Y: Extracorporeal CPR for massive

pulmonary embolism in a ‘hybrid 2136 emergency department’. Am J

Emerg Med. 37:2132–2135. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Wallentin L, Goldstein P, Armstrong PW,

Granger CB, Adgey AA, Arntz HR, Bogaerts K, Danays T, Lindahl B,

Makijarvi M, et al: Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in

combination with the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin or

unfractionated heparin in the prehospital setting: the assessment

of the safety and efficacy of a new thrombolytic regimen (ASSENT)-3

PLUS randomized trial in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation.

108:135–142. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Ali MR, Hossain MS, Islam MA, Arman MS,

Raju GS, Dasgupta P and Noshin TF: Aspect of thrombolytic therapy:

A review. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014:5865102014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Saber-Moghadam R: Investigating the

efficacy of noninvasive brain stimulation on poststroke dysphagia:

A systematic review. JNFH. 10:P2862022.

|

|

86

|

Beales I: Recent advances in the

management of peptic ulcer bleeding. F1000Res. 6:17632017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Scott JH, Gordon M, Vender R, Pettigrew S,

Desai P, Marchetti N, Mamary AJ, Panaro J, Cohen G, Bashir R, et

al: Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in massive

pulmonary embolism-related cardiac arrest: A systematic review.

Crit Care Med. 49:760–769. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|