Lactate, once regarded as a metabolic waste product

of glycolysis, is now considered a multifunctional molecule that

promotes cancer progression. Notably, the Warburg effect is a

hallmark of cancer metabolism; even under oxygen-rich conditions,

tumor cells still preferentially metabolize glucose through

glycolysis and tend to ‘ferment’ glucose into lactic acid, leading

to an accumulation of lactic acid within the tumor microenvironment

(TME) (1). In addition to serving

a role in central carbon metabolism, lactate regulates tumor

immunity, antiviral responses and endoplasmic reticulum

(ER)-mitochondrial magnesium ion dynamics (2), and contributes to pathological

processes such as cancer progression (3). Lactate, as a signaling molecule,

regulates immune evasion, angiogenesis and therapeutic resistance

(4,5).

The discovery of lactylation, a lactate-derived

post-translational modification (PTM) of lysine residues, has

revealed a direct mechanistic link between glycolytic flux and

cellular regulation. Lactate, as the substrate for this

modification, catalyzes the addition of lactate groups to both

histone and non-histone proteins (6). This process links metabolic disorders

to epigenetic reprogramming, alterations in chromatin structure,

transcriptional programs and protein-protein interactions, thereby

promoting tumorigenesis (7). For

example, M1-polarized macrophages rely on aerobic glycolysis to

drive histone lactylation (8),

whereas B-cell adapter for PI3K facilitates their transition to a

reparative macrophage phenotype via lactylation (9). Lactate enhances the activity of

pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) by lactylating its K62 residues,

inhibiting the Warburg effect and promoting the transformation of

inflammatory macrophages (iNOS+ CD68+ cells)

into reparative macrophages (ARG1+ CD68+

positive cells) (10). In

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), hypoxia-induced long noncoding

RNA-AC020978 amplifies glycolysis by promoting PKM2 nuclear

translocation and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) activation

(11). Furthermore, lactate

directly inhibits CD8+ T cells, natural killer T (NKT)

cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, while enhancing regulatory

T (Treg) cell stability and function, promoting immunosuppression

(12).

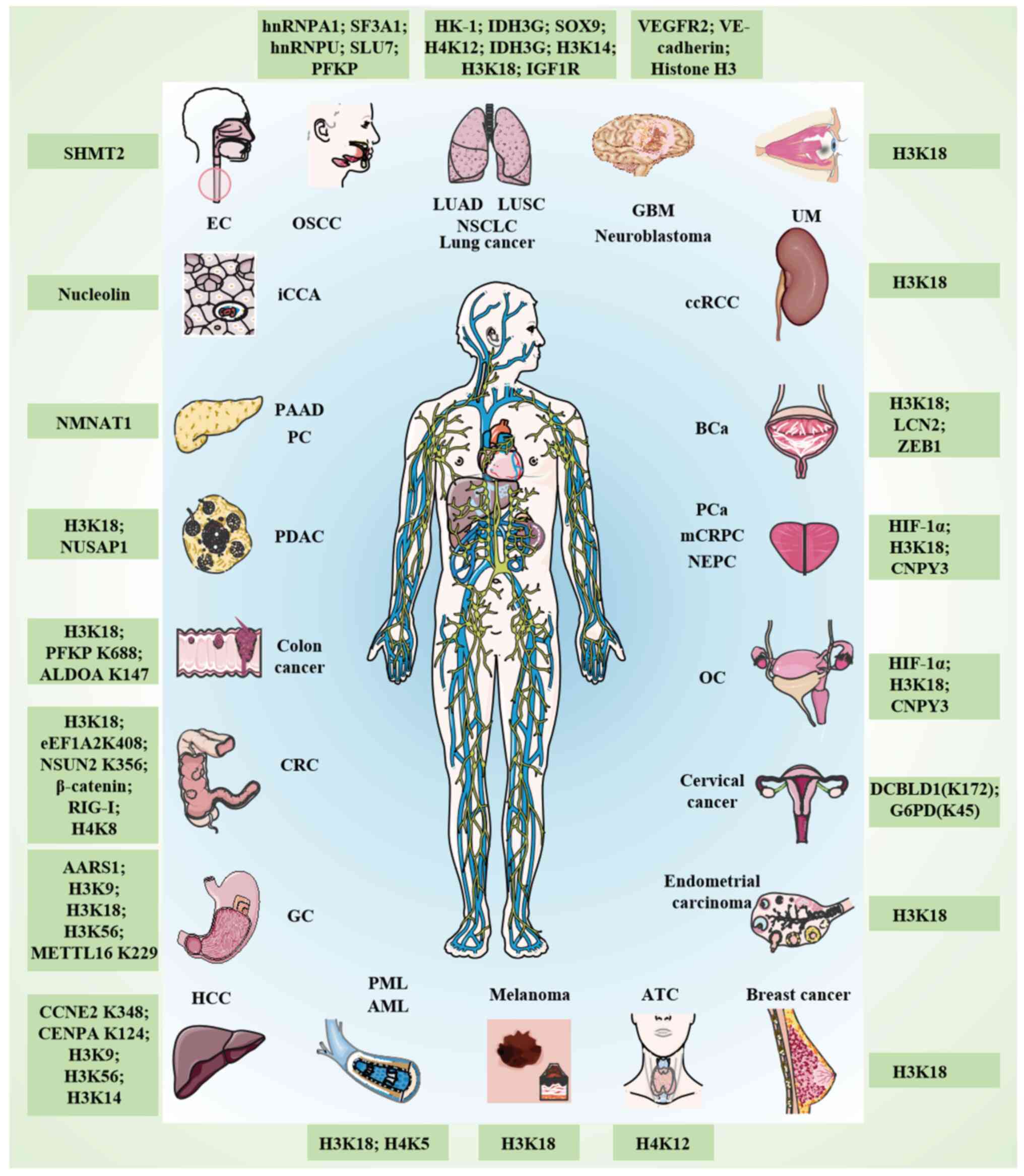

Researchers have also demonstrated the notable role

of lactylation in various types of cancer via numerous mechanisms

(Table I; Fig. 1). For example, pan-cancer analyses

have revealed upregulated lactylation-related genes (such as CREBBP

and EP300) and their association with kidney renal papillary cell

carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (13). Furthermore,

hypoxia-glycolysis-lactylation-related genes predict gastric cancer

(GC) progression (14), whereas

lactate-driven lactylation in colorectal cancer (CRC) is associated

with proliferation, metastasis and immune evasion (15). Lactylation serves a role in

tumorigenesis, including in tumor cell proliferation, invasion,

metastasis, DNA damage repair and immune cell killing, and also

promotes therapeutic resistance through autophagy activation, drug

efflux pumps and DNA damage repair (16).

The present review discusses the latest progress in

lactic acid biology, highlighting its dual role as a driving factor

in the pathogenesis of cancer and in therapeutic sensitivity. The

review also explores the impact of lactylation on metabolic

reprogramming, immune evasion and therapeutic resistance, and

discusses new strategies for precision oncology using this

pathway.

Lactylation critically regulates glycolytic flux in

cancer. Digestive system cancers account for >25% of global

cancer cases (17), with

lactylation emerging as a key regulator of immunosuppression and

metabolic reprogramming in the TME. Yang et al (18) identified 9,256 non-histone lysine

lactylation (Kla) sites in hepatitis B virus-associated HCC,

including adenylate kinase 2 lactylation at K28, which may drive

metastasis by disrupting metabolic regulation.

Abundant immune cell infiltration, particularly

macrophages, and increased genetic instability are traits

associated with high lactylation scores. Lactylation score can be

used to predict the malignant progression of GC and immune escape

(19). Hypoxia-induced

mitochondrial alanyl-tRNA synthetase AARS2 drives lactylation of

pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex components (PDHA1-K336 and

CPT2-K457/8), suppressing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) by

limiting pyruvate and acetyl-CoA influx (20). AARS1, upregulated in GC, catalyzes

lactate-AMP formation, promoting lactylation of p53 at lysine

120/139. This disrupts the DNA binding and transcriptional activity

of p53, coupling metabolic rewiring to proteomic changes that fuel

tumorigenesis (21). AARS1 also

activates the YAP-TEAD complex via nuclear lactylation, forming a

Hippo pathway feedback loop that accelerates GC progression and is

associated with poor prognosis (22). In addition, G-protein-coupled

receptor 37 (GPR37) activates the Hippo pathway, upregulating

lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) to enhance glycolysis and H3K18

lactylation (H3K18la). This promotes CXCL1/CXCL5 secretion,

remodeling the TME to favor metastasis. By contrast, GPR37

depletion suppresses the progression of liver metastasis in CRC

(23). Lactate also stabilizes

β-catenin via hypoxia-induced lactylation, activating Wnt signaling

and CRC proliferation (24).

Nucleolin lactylation promotes MAPK-activated death

domain protein translation and ERK activation, which is associated

with poor intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) prognosis

(25). Non-histone lactylation

sites in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells, such as

hnRNPA1, SF3A1, hnRNPU and SLU7, are linked to glycolytic

dysregulation and tumorigenesis, highlighting the role of Kla in

pathogenesis (26). In lung

adenocarcinoma (LUAD), basic leucine zipper and W2 domains 2 (BZW2)

enhances glycolysis and isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (IDH3G)

lactylation. Combined inhibition of BZW2 and glycolysis [such as

2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG)] suppresses tumor growth (27).

CircXRN2 is downregulated in bladder cancer (BCa)

tissues and suppresses tumor growth by binding to the speckle-type

POZ protein (SPOP) degron. This interaction blocks SPOP-mediated

degradation of large tumor suppressor kinase 1, activating the

Hippo signaling pathway to suppress tumor progression driven by

H3K18la (28). Upregulation of

zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) in BCa is counteracted

by phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), and PFK-1 inhibits glycolysis

through the lactylation of ZEB1 and suppresses its malignant

effects, including cell proliferation, migration and invasion

(29). During neuroendocrine

prostate cancer (NEPC) development, ZEB1 transcriptionally

regulates the expression of several key glycolytic enzymes, thereby

predisposing tumor cells to utilize glycolysis for energy

metabolism. Lactate accumulation enhances histone lactylation,

increasing chromatin accessibility and cellular plasticity

(including neural gene expression), thereby promoting NEPC

progression (30).

In BCa, the enhanced aerobic glycolysis rate

supports c-Myc expression through histone lactylation at the

promoter level. c-Myc further upregulates serine/arginine splicing

factor 10 (SRSF10) through transcription to drive the selective

splicing of MDM4 and Bcl-x in BCa cells. Restricting the activity

of key glycolytic enzymes may affect the c-Myc/SRSF10 axis to

reduce the proliferation of BCa cells (31). Potassium channel subfamily K member

1, which is upregulated in BCa, activates LDHA to enhance

glycolysis and H3K18la. LDHA upregulation creates a feed-forward

loop, reducing tumor cell adhesion and promoting

invasion/metastasis (32).

Deficiency in the Numb/Parkin pathway in prostate cancer (PCa) or

LUAD induces metabolic reprogramming, resulting in a significant

increase in the production of lactate acid, which subsequently

leads to the upregulation of histone lactylation and transcription

of neuroendocrine-associated genes (33). Aerobic glycolysis in anaplastic

thyroid cancer (ATC) increases overall protein lactylation by

increasing cellular lactate availability, and H4K12la activates the

expression of multiple genes necessary for ATC proliferation.

Furthermore, the oncogene BRAFV600E enhances glycolysis to

reprogram the cellular lactylation landscape, resulting in

H4K12la-driven gene transcription and cell cycle dysregulation.

Notably, treatment with a BRAFV600E inhibitor, combined with

blocking cell emulsification, can inhibit ATC progression in an

8505c xenograft tumor mouse model (34).

Autophagy and glycolysis are highly conserved

biological processes involving physiological and pathological

cellular activities. A number of core autophagy proteins undergo

lactylation during cancer (35).

Under nutrient deprivation, lactate-mediated lactylation of

autophagy proteins (such as VPS34, ULK1) enhances autophagic flux,

promoting tumor cell survival (36). In lung cancer and GC, lactate

mediates the lactylation of PIK3C3/VPS34 at lysine 356 and lysine

781 through acyltransferase KAT5/TIP60. The lactylation of

PIK3C3/VPS34 enhances the binding of PIK3C3/VPS34 to beclin 1,

ATG14 and UVRAG, increases the lipid kinase activity of

PIK3C3/VPS34, promotes macroautophagy/autophagy and advances the

endolysome degradation pathway (37).

In the TME, tumor cells export lactate via

monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4), while oxidative tumor cells

import it through MCT1 to fuel OXPHOS (38). Although glycolysis dominates in

most types of cancer, OXPHOS remains active in malignancies such as

leukemia and lymphoma, enabling metabolic flexibility (39). Glucose fuels glycolysis, which

feeds into the TCA cycle and OXPHOS in oxidative cells, or sustains

lactate fermentation in hypoxic regions (40). In SW480 colon cancer cells,

lactylation targets glycolytic enzymes (such as PFKP-K688 and

ALDOA-K147), potentially establishing negative feedback loops to

modulate glycolysis (41). In

pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells, under glucose deprivation, lactate

enhances glutaminase 1-mediated glutamine metabolism and NMNAT1

lactylation, suppressing p38 MAPK and promoting survival (42). Solute carrier family 16 member 1

lactylation is critical for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

progression, and targeting this axis may inhibit tumor growth

(43). In NSCLC, metabolic

dysregulation drives lactate accumulation, which replenishes the

TCA cycle while suppressing glucose uptake and glycolysis. Lactate

downregulates glycolytic enzymes [such as hexokinase (HK)-1 and

PKM] and upregulates TCA enzymes (including SDHA and IDH3G) via

histone lactylation at their promoters, enhancing NSCLC

proliferation and migration (44).

The hypoxic microenvironment resulting from reduced

local blood flow in pancreatic cancer (PC) triggers a shift in

glycolytic-dependent energy metabolism by stabilizing HIF-1α

(51). Elevated H3K18la in PDAC

activates TTK and BUB1B transcription, upregulating P300 to enhance

glycolysis. TTK phosphorylates LDHA at Y239, amplifying lactate and

H3K18la levels (52). Nuclear and

spindle-associated protein 1 (NUSAP1) binds c-Myc and HIF-1α to

upregulate LDHA. Lactate stabilizes NUSAP1 via Kla, forming a

feed-forward loop (NUSAP1-LDHA-lactate-NUSAP1) that drives

metastasis (53). In esophageal

cancer (EC), hypoxia not only enhances the expression of serine

hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2) protein but also initiates the

lactylation of SHMT2 protein and enhances its stability, thus

accelerating the malignant progression of EC (54).

Angiogenic mimicry provides tumor cells with a blood

supply independent of endothelial cells (55). MAPK 6 pseudogene 4 stabilizes

Krüppel-like factor 15, which transcriptionally activates LDHA.

LDHA-mediated lactylation of vascular endothelial growth factor

receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and VE-cadherin enhances their expression,

fostering GBM cell proliferation, migration and angiogenic mimicry.

However, the specific lactylation sites in VEGFR2 and VE-cadherin

involved in GBM still require further exploration (56). FK506-binding protein 10 (FKBP10)

binds LDHA, enhancing LDHA-Y10 phosphorylation to amplify the

Warburg effect and histone lactylation. By contrast, HIF-2α, a

driver of angiogenesis and redox balance, suppresses FKBP10

transcription. Combining HIF-2α inhibitors (such as PT2385) with

FKBP10 targeting enhances antitumor efficacy, particularly in

low-FKBP10 ccRCC (57). Lactate

import via MCT1 stabilizes HIF-1α under normoxia through HIF-1α

lactylation, perpetuating KIAA1199 expression. By contrast,

silencing KIAA1199 restores 3A semaphoring (sema)3A and inhibits

angiogenesis (58). Lactate also

stabilizes HIF-1α, promoting discoidin, CUB, and LCCL

domain-containing protein 1 (DCBLD1) transcription. DCBLD1-K172

lactylation inhibits ubiquitination, blocking autophagy-mediated

degradation of G6PD to fuel the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP).

This activates the PPP, fueling cervical cancer cell migration,

invasion and growth (59).

G6PD K45 is lactylated during G6PD-mediated

antioxidant stress. In primary human keratinocytes and HPV-negative

cervical cancer C33A cell lines ectopically expressing HPV16 E6,

G6PD K45A is not lactylated, and the transduction of G6PD K45A has

been shown to increase the levels of glutathione and NADPH, and can

accordingly decrease the levels of reactive oxygen species. In

vivo, 6-aminonicotinamide inhibits the activity of the G6PD

enzyme or the re-expression of G6PD K45T, thereby suppressing tumor

proliferation (60). The

non-metabolizable glucose analog 2-DG and oxamate treatment have

been reported to decrease the levels of lactylation to inhibit

proliferation and migration, induce apoptosis and arrest the cell

cycle of EC cells. In addition, a study on EC xenograft tumor model

mice and EC cells confirmed that H3K18la may upregulate the

deubiquitinase ubiquitin-specific protease (USP)39, stabilizing

phosphoglycerate kinase 1 to activate the PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α axis and

to enhance glycolysis (61).

Lactylation orchestrates the progression of cancer

through extensive epigenetic reprogramming, modulating both histone

and non-histone targets to alter gene expression, RNA processing

and cellular phenotypes.

Histone lactylation directly modulates chromatin

dynamics. In GC, H3K18la activates vascular cell adhesion molecule

1, promoting GC cell proliferation and migration via AKT/mTOR

signaling, and recruits immunosuppressive mesenchymal stem cells

through CXCL1 upregulation, thereby promoting immune suppression

and tumor metastasis (62). In

CRC, tumor-derived lactate inhibits retinoic acid receptor γ in

macrophages, elevating H3K18la and IL-6/STAT3 signaling to polarize

macrophages toward a pro-tumorigenic state (63). Histone lactylation (such as H4K8la,

H4K16la) is suppressed by liver kinase B1, which induces senescence

by inhibiting telomerase reverse transcriptase (64). Furthermore, lactate in the TME of

LUAD reduces the transcription of solute carrier family 25, member

29 (SLC25A29) in endothelial cells. Specifically, the increase of

H3K14la and H3K18la in the SLC25A29 promoter region reduces the

transcription of SLC25A29, which affects the proliferation,

migration and apoptosis of endothelial cells (65). The NF-κB pathway promotes the

Warburg effect, thereby inducing the lactylation of H3 histone and

increasing the expression of LINC01127. The enhanced expression of

LINC01127 promotes the self-renewal of GBM cells and directly

guides POLR2A to the MAP4K4 promoter region to regulate the

expression of MAP4K4, thereby activating the JNK pathway and

ultimately regulating the self-renewal of GBM cells (66). Inactivation of the von

Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor triggers histone lactylation,

activating platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ)

transcription; PDGFRβ signaling reciprocally enhances histone

lactylation, creating an oncogenic feedback loop (67).

The lactylation and delactylation of non-histone

proteins are closely related to the pathogenesis of HCC. Sirtuin

(SIRT)3 deficiency in HCC permits the accumulation of cyclin

(CCN)E2 lactylation, whereas honokiol-mediated SIRT3 reactivation

delactylates CCNE2-K348 to suppress HCC cell proliferation

(68). Furthermore, CENPA-K124

lactylation enhances the interaction between CENPA and the

transcription factor YY1, driving CCND1 and neuropilin 2 expression

to promote HCC progression (69).

In CRC, KAT8-catalyzed lactylation of eEF1A2K408 has been shown to

result in boosted translation elongation and enhanced protein

synthesis, which contribute to tumorigenesis (70). Furthermore, H3K18la has been

reported to increase METTL3 expression in tumor-infiltrating

myeloid cells. Notably, METTL3 mediates m6A modification on Jak1

mRNA in tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells, and the m6A-YTHDF1 axis

enhances JAK1 protein translation efficiency, subsequent

phosphorylation of STAT3 and immunosuppression (71). In ocular melanoma, histone

lactylation promotes tumorigenesis by increasing the expression of

YTHDF2. YTHDF2 recognizes m6A-modified PER1 and TP53 mRNA, promotes

their degradation and accelerates the occurrence of ocular melanoma

(72). Histone lactylation

enhances the expression of AlkB homolog 3 (ALKBH3) by removing the

m1A methylation of SP100A. ALKBH3 lactylation facilitates

promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear condensate formation,

bridging m1A modification to metabolic reprogramming (73). Elevated NOP2/Sun RNA

methyltransferase family member 2 (NSUN2), an m5C

methyltransferase, and Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1), an m5C

methylation recognition enzyme, drive m5C modification of ENO1 mRNA

in CRC, promoting lactate production. This lactate then induces

NSUN2 expression via histone H3K18 lactylation and enhances RNA

binding of NSUN2 through its own lactylation (K356), creating a

feed-forward loop linking metabolism and epigenetics (74). Furthermore, the chemotherapeutic

agent gemcitabine (GEM) increases histone acetylation but reduces

histone lactylation, suggesting cross-talk between PTMs in the

mechanism of GEM (75). These

mechanisms collectively establish lactylation as a master regulator

of cancer epigenetics, influencing angiogenesis, therapy resistance

and metabolic adaptation.

Lactylation orchestrates immunosuppression within

the TME by reprogramming immune cell function and recruitment. In

HCC, dysregulation of histone acetyltransferase EP300 and histone

deacetylase (HDAC)1-3 alters immune cell infiltration (including B

cells) and predicts poor prognosis when HDAC1/2 are upregulated

(76). Glucose transporter 3

(GLUT3) levels are significantly increased in GC tissues. By

contrast, after knocking down GLUT3, the levels of LDHA,

L-lactylation, H3K9, H3K18 and H3K56 are markedly reduced. Notably,

in GLUT3-knockdown cell lines, upregulation of LDHA reverses the

lactylation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition functional

phenotypes, while Kla is enriched in GC tissues and predicts poor

survival, underscoring its role as a prognostic biomarker (77,78).

Claudin-9 promotes glycolytic metabolism in GC cells by activating

the PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α signaling pathway, resulting in increased

lactate production. Lactate, as a glycolytic metabolite, can

enhance the lactylation of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and

improve its stability. This modified PD-L1 will inhibit the

antitumor immune response of CD8+ T cells, thereby

enhancing GC cell immune evasion and promoting the progression of

GC (79). STAT5-induced lactate

accumulation promotes nuclear translocation of E3 binding protein,

increases lactylation of the PD-L1 promoter, and subsequently

induces PD-L1 transcription, driving immunosuppression in acute

myeloid leukemia (80).

The gut microbiome further amplifies

immunosuppression through lactylation. In CRC, RIG-I lactylation

induced by Escherichia coli inhibits the recruitment of

NF-κB to the NLRP3 promoter, suppresses inflammasome activity,

impairs CD8+ T-cell function and simultaneously enhances

Treg cell-mediated tolerance (81). Similarly, gram-negative bacterial

lipopolysaccharide upregulates the expression of LINC00152 and

promotes the invasion of CRC cells by introducing histone

lactylation on its promoter, reducing the binding efficiency of

inhibitory factor YY1 to it (82).

In lung squamous cell carcinoma, solute carrier

family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1) upregulation is associated with elevated

protein lactylation and SPP1+ macrophage abundance,

driving therapy resistance (83).

In advanced GBM, monocyte-derived macrophages dominate the TME and

secrete IL-10 via PERK-driven histone lactylation, inhibiting

T-cell activity. PERK deletion abolishes lactylation, restores

T-cell function and delays tumor growth (84). Furthermore, single-cell RNA

sequencing has confirmed lactylation-related gene expression across

glioma-infiltrating immune cells (monocytes, macrophages,

CD8+ T cells), and lactylation scores have been reported

to be associated with lipogenesis, DNA repair and mTORC1 signaling

(85). HK-3 indirectly affects

neuroblastoma progression by recruiting and polarizing M2-like

macrophages through the PI3K/AKT/CXCL14 axis. After knocking down

the expression of HK3, the levels of histone lysine lactylation in

neuroblastoma cell lines SK-N-SH and SK-N-BE (2) are significantly reduced, and the

lactate concentration in the supernatant of SK-N-SH/SK-N-BE

(2) cell cultures is significantly

reduced. These findings indicate that in neuroblastoma HK3 affects

lactate secretion in the microenvironment and regulates histone

lactylation (86). In the TME of

malignant pleural effusion (MPE), the antitumor activity of

CD8+ T cells and NKT-like cells is inhibited, and the

function of Treg cells is enhanced. The glycolytic pathway and

pyruvate metabolism are highly activated in a distinct

subpopulation of NKT-like cells expressing FOXP3 in MPE. Notably, a

small molecule inhibitor of MCT1, 7ACC2, has been shown to reduce

FOXP3 expression and histone lactylation levels in NKT-like cells

(87).

In addition to regulating metabolic reprogramming,

and epigenetic and immune pathways, lactylation drives

multi-faceted treatment resistance in cancer. Previous proteomic

profiling identified 1,438 lactylation sites across 772 proteins in

HCC tissues, implicating lactylation in amino acid metabolism,

ribosomal function and fatty acid metabolism (88). Lactylation of USP14 and ATP-binding

cassette (ABC) subfamily F member 1 is associated with drug

sensitivity. Notably, patients with high-risk HCC respond better to

sorafenib, whereas low-risk patients exhibit elevated Tumor Immune

Dysfunction and Exclusion scores and benefit from immunotherapy

(89). Lactylation also activates

oncogenic pathways (Wnt, MAPK, mTOR, NOTCH) via nuclear receptor

6A1, oxysterol-binding protein 2 and UNC119B, linking Kla to immune

evasion and therapy resistance (90). Apicidin treatment reduces

lactylation, suppressing HCC migration and proliferation, although

clinical validation and mechanistic crosstalk with other PTMs

require further study (91).

In GC, copper stress lactylates METTL16 at K229,

enhancing copper ionophore (elesclomol) efficacy. Combining

elesclomol with the SIRT2 inhibitor AGK2 amplifies copper toxicity,

suggesting a therapeutic strategy to overcome chemoresistance

(92,93). In CRC, H3K18la upregulation in

bevacizumab-resistant tumors, which upregulates autophagy protein

RUBCNL/Pacer through BECN1 interaction, enhances autophagosome

maturation and survival (94). In

diapause-like CRC, SMC4 and phosphoglycerate mutase 1 loss disrupts

F-actin assembly and upregulates ABC transporters via histone

lactylation, reducing chemotherapy sensitivity (95). Aldolase B-activated PDH kinase 1

drives lactylation of circulating carcinoembryonic antigen,

activating CEACAM6 to promote proliferation and chemoresistance in

CRC (96).

Hypoxia in the TME amplifies lactate production,

global lactylation and immunosuppression (97,98).

Hypoxia upregulates SOX9 lactylation, enhancing stemness and

invasion in NSCLC (99). AKR1B10

promotes LDHA-driven lactate accumulation, stimulating H4K12la to

activate CCNB1 and accelerate DNA replication, conferring

pemetrexed resistance in lung cancer brain metastasis (100). This aligns with findings that

tumor resistance stems from heterogeneity and immunosuppressive TME

interactions (101).

In BCa, H3K18la drives the key transcription factors

YBX1 and YY1 associated with cisplatin resistance, thereby

promoting cisplatin resistance (102). Sema3A suppresses VEGFA-induced

colony formation, proliferation and PD-L1 expression in PCa.

Sema3A, along with sema3B/C/E, predicts biochemical recurrence in

low- to intermediate-risk PCa post-prostatectomy (103). Prognostic models combining the

lactylation-related genes ALDOA, DDX39A, H2AX, KIF2C and RACGAP1

has been shown to predict disease-free survival and treatment

response in PCa. These genes are highly expressed in

castration-resistant tumors, underscoring the clinical relevance of

lactylation (104). In

PTEN-deficient metastatic castration-resistant PCa, a PI3K

inhibitor (PI3Ki) has been reported to reduce histone lactylation

within tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), resulting in their

anticancer phagocytic activation, which is augmented by ADT/aPD-1

treatment and abrogated by feedback activation of the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway. Furthermore, co-targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling with

LGK-974 in combination with PI3Ki, has previously demonstrated

durable tumor control in 100% of mice via H3K18lac suppression and

complete TAM activation (105,106). Gambogic acid disrupts this cycle

by recruiting SIRT1 to delactylate chaperone protein CNPY3,

inducing lysosomal rupture and pyroptotic cell death (107). Lactylation-related genes

influence BCa growth, immune microenvironment remodeling and

therapy resistance by modulating lactate transport within the TME

(108). In addition, H4K12la

contributes to chemoresistance and adverse immune responses in

breast cancer (109).

Lactylation modulation represents an emerging

frontier for targeted cancer therapy, with implications for

treatment response prediction and combination strategies. Yu et

al (110) identified 14

lactylation-related genes in ovarian cancer (OC) using The Cancer

Genome Atlas database, stratifying patients into low- and high-risk

groups. The low-risk profile was associated with metabolic

processes (thermogenesis and OXPHOS) and immune responses

(neutrophil extracellular traps and IL-17 signaling). High-risk

features were associated with cell adhesion (proteoglycans and

adhesive plaques) and carcinogenic signaling (Wnt and extracellular

matrix-receptor interactions). Notably, lactylation-related genes

were shown to be closely related to tumor classification and

immunity, and OC based on lactylation-related characteristics was

indicated to have a good prognostic performance.

Similarly, in skin cutaneous melanoma (CM),

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that the lactylation

low/TME high group had the highest overall survival (OS) rate,

whereas the lactylation high/TME low group had the lowest OS rate.

In addition, CM immunotherapy was revealed to be more suitable for

patients in the lactylation low/TME high group (111). Notably, calmodulin-like protein 5

is a core lactylation-associated gene in CM, which is associated

with patient survival and immune infiltration (112).

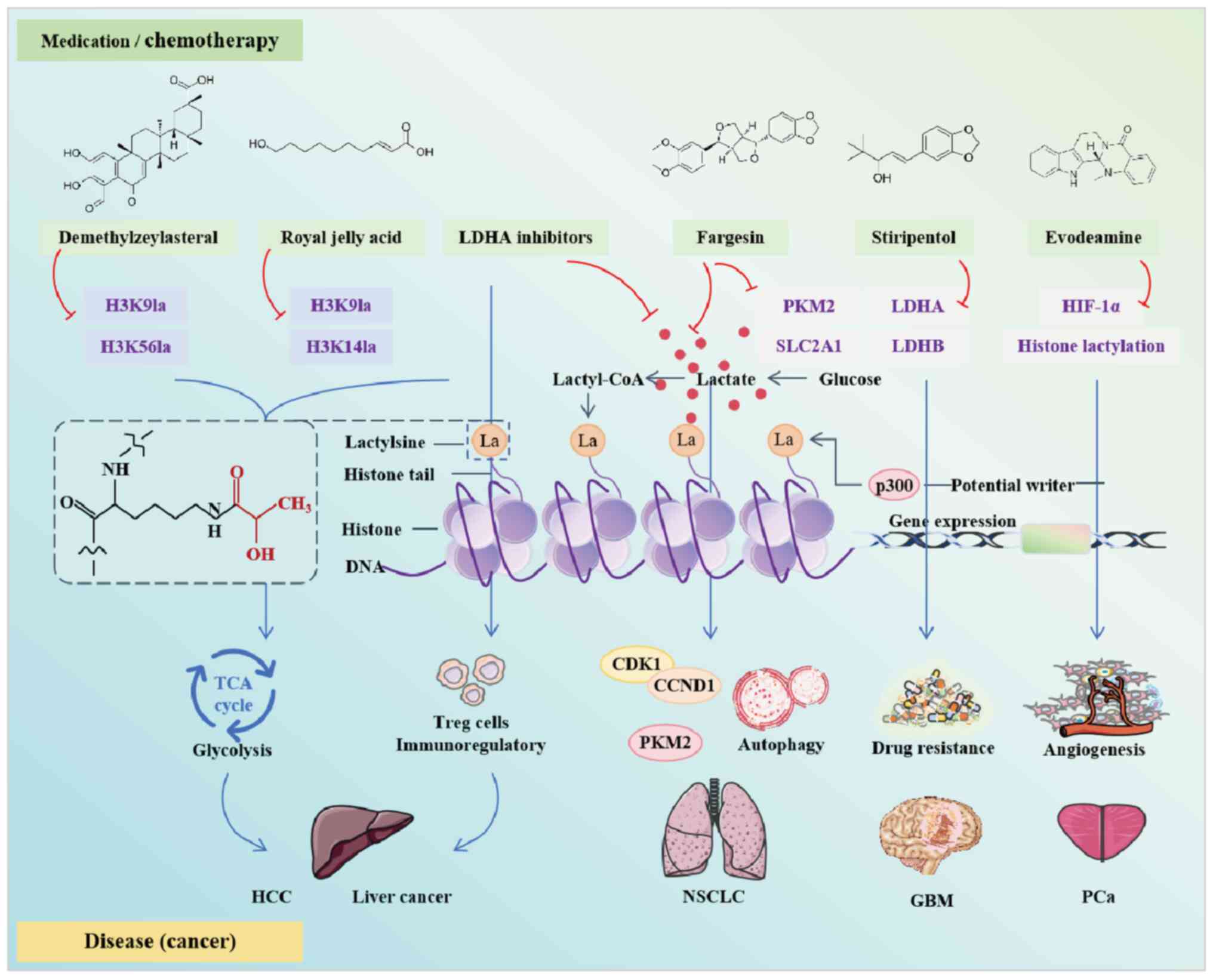

Lactate accumulation in the TME promotes immune

evasion and tumor survival, but lactylation also offers therapeutic

opportunities. Preclinical studies have highlighted strategies such

as inhibiting lactate production (for example, via LDHA inhibitors)

or disrupting histone lactylation [such as with demethylzeylasteral

(DML), royal jelly acid (RJA) or fargesin] to reduce tumor energy

supply or enhance immunotherapy efficacy (Fig. 2). However, these findings are

limited by preclinical risks, as results from homogeneous mouse

models may overestimate efficacy in humans, where TME heterogeneity

remains unresolved.

In a mouse liver cancer cell model (Hepa1-6), LDHA

inhibitors have been shown to suppress the immunoregulatory effects

of Treg cells in the TME by reducing lactate concentration.

Notably, combined treatment with anti-PD-1 and LDHA inhibitors has

a stronger antitumor effect than anti-PD-1 alone (118). The anti-epileptic drug,

stiripentol enhances the sensitivity of cancer cells to

temozolomide by inhibiting lactylation. Lactylation is upregulated

in relapsed GBM tissues and temozolomide-resistant cells, mainly

since H3K9la confers temozolomide resistance in GBM through

Luc7L2-mediated intron-7 retention of MLH1. Stiripentol enhances

temozolomide sensitivity in GBM by inhibiting LDH activity and

H3K9la-mediated resistance (119). Oxamate promotes immune activation

of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells infiltrating tumors. In

a GBM mouse model, oxamate has been shown to promote the immune

activation of tumor-infiltrating CAR-T cells through altering the

phenotypes of immune molecules and increasing Treg-cell

infiltration (120). However,

murine models cannot fully recapitulate human metabolic plasticity.

PD-1/PD-L1 is a major inhibitory checkpoint pathway that regulates

immune escape in patients with cancer, and its participation and

inhibition notably reshape the pattern of tumor clearance. Immune

checkpoint inhibition targeting PD-1/PD-L1 is a reliable tumor

therapy (121). Notably, lactate

treatment in PCa cells can increase the expression of HIF-1α and

PD-L1, while restricting the expression of sema3A, whereas

silencing the expression of MCT4 reverses this process. Evodiamine

blocks lactate-induced angiogenesis by restricting the histone

lactylation and expression of HIF-1α in PCa, further enhances

Sema3A transcription, inhibits PD-L1 transcription, and induces

ferroptosis by decreasing the expression of low GSH peroxidase 4

(122).

Proteomics analysis has shown that H4K12la is

elevated in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) tissues, and

H4K12la has been shown to be positively associated with the

proliferative marker Ki-67 and negatively associated with OS rate

(123). However, it is still

necessary to validate H4K12la as a biomarker for TNBC

resistance.

While lactylation is a promising therapeutic target,

integrating preclinical findings with clinical practice requires:

i) Interdisciplinary collaboration; for example, integrating

metabolomics, epigenetics and immunology to address the complexity

of the underlying mechanism. ii) Robust clinical validation, with

staged trials to evaluate safety, efficacy and related biomarkers.

iii) A patient-centered approach to develop guidelines for targeted

lactylation therapy based on tumor subtypes, TME background and

metabolic vulnerability. By addressing these challenges, lactate

regulation could become a cornerstone of precision oncology.

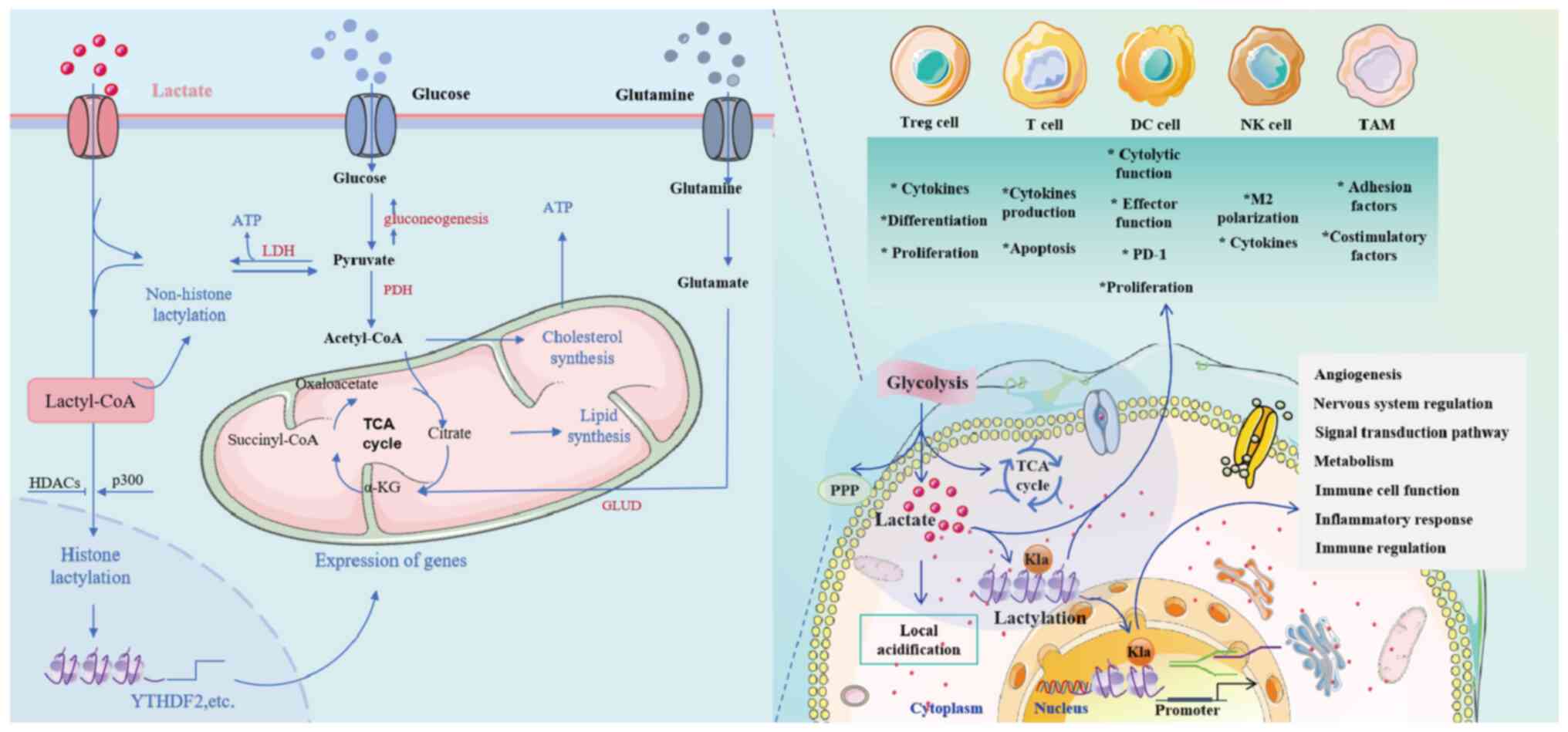

Tumor cells produce lactate through glycolysis,

resulting in local acidification and altering the pH value of the

TME. The acidified environment affects the cellular components of

the TME, and affects tumor growth and spread. Lactate acts as a

signaling molecule to regulate tumor growth, invasion, metastasis

and therapeutic response. Furthermore, lactylation is involved in

critical biological processes such as glycolytic cell function,

macrophage polarization, angiogenesis, mitochondrial activity and

nervous system regulation. Lactylation also modulates tumor

behavior by influencing signal transduction pathways. The interplay

between lactylation and the immune cycle is complex, involving

metabolism, immune cell function, inflammatory responses and immune

regulation (Fig. 3). Therefore,

intervening in lactylation may be a new target for tumor

therapy.

The structural complexity and functional diversity

of histones necessitate further exploration of their lactylation in

cancer to elucidate its role and mechanism in tumor development.

H3K18la is associated with shifts in cellular states, with

quantitative lactylation changes at promoters and enhancers

potentially driving these transitions (124). H3K9la levels are upregulated in

endothelial cells in response to VEGF stimulation, and

hyperlactylation of H3K9 inhibits expression of the lactylation

eraser HDAC2, whereas upregulation of HDAC2 decreases H3K9la and

suppresses angiogenesis (125,126). Elevated H3K9la levels in LCSCs,

HCC and GBM are associated with tumorigenicity, drug resistance and

immunosuppression (127). Histone

lactylation thus influences gene expression, tumor progression and

immune evasion, underscoring the need to determine its underlying

mechanisms for developing novel therapies.

In GC, lactate-driven lactylation of NBS1 promotes

homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA repair, fostering

chemoresistance, while inhibition of lactate production has emerged

as a promising strategy (128).

Similarly, MRE11 lactylation at K673, mediated by cyclic-AMP

response binding protein-binding protein (CBP), enhances HR repair,

whereas targeting CBP or LDH sensitizes tumors to chemotherapy in

preclinical models (129).

KRAS-driven lactylation activates circATXN7, which sequesters NF-κB

p65 in the cytoplasm, promoting immune evasion (130). However, the potential for

resistance to lactylation-targeted therapies remains a concern, as

tumors may exploit alternative DNA repair pathways or upregulate

compensatory PTMs, highlighting the need for combination

therapies.

While preclinical studies have demonstrated the

potential of lactylation inhibition (such as by targeting LDH or

CBP) to enhance chemosensitivity and reduce immune evasion,

clinical translation faces notable hurdles (131,132). Small molecule inhibitors and

antibodies targeting lactylation-related proteins have shown

promising prospects in preclinical models, and targeted lactylation

is expected to improve the immunosuppressive TME. For example, it

has been shown that activating the SIRT3 lactase function can

restore the anti-leukemia activity of NK cells (133). In addition, irinotecan has been

found to possess new functions of inhibiting lactylation. Their

safety is known and they can enter clinical trials more quickly

(134). A number of

small-molecule inhibitors also exhibit synergistic effects when

used in combination with existing chemotherapy drugs or

immunotherapies. Furthermore, lactylation levels vary among

different tumor types and individuals Therefore, specific

lactylation sites may be considered new and effective targets for

tumor diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, developing highly

specific inhibitors that can precisely target specific lactylated

proteins or sites is currently a challenge, and it is necessary to

avoid interfering with other similar post-translational

modifications (such as acetylation). How to efficiently deliver

drugs to tumor tissues and penetrate into the interior of tumor

cells is a common problem faced by clinical application. New

delivery systems such as nano-strategies may be the solution. In

addition, the lactylation regulatory network is complex, and tumor

cells may develop drug resistance through other compensatory

pathways; thus, it is necessary to continuously explore the

mechanism and develop combined strategies (135,136).

Lactylation detection remains technically

challenging. While high-performance LC-MS/MS, LC/MS and anti-Kla

immunoblotting are widely used, improved precision is needed to

distinguish lactylation from other PTMs, particularly given the

overlapping molecular weights of histones H1, H3 and H4 (114). Advanced proteomics analysis and

site-specific antibodies could address these limitations.

Clinically, interventions must account for tissue-specific oxygen

gradients and lactylation heterogeneity. Although lactylation

biomarkers could monitor therapeutic response, validation in human

cohorts is lacking. Early-phase trials of lactylation inhibitors

are needed to assess safety, efficacy and optimal dosing.

As understanding of the role of lactylation in tumor

biology deepens, targeting this pathway is expected to address

treatment resistance and immunosuppression in some of the most

aggressive malignant tumors, especially those driven by glycolytic

metabolism and immune rejection. Future success will depend on a

careful balance of efficacy and toxicity, the intelligent design of

combination regimens, and the development of diagnostic tools to

identify patients most likely to benefit from lactylation-directed

therapy.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Research Funds of Center for Xin'an

Medicine and Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine of

institute of Health and Medicine, Hefei Comprehensive National

Science Center (grant no. 2023CXMMTCM025), the Anhui Education

Department (grant no. gxgwfx2022019), the Anhui University of

Chinese Medicine (grant no. 2022BHTNXA05, DT2400001288) and the

Anhui Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no.

2022CCYB10).

Not applicable.

XW, JC and BW collected and reviewed the literature,

and wrote the review. YL, XZ and YS collected and reviewed the

literature. CM made substantial contributions to the conception and

design of the work. YH is responsible for the design of this work,

the final approval of the version to be published, and for all

aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved. Data authentication is not applicable.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Zhu W, Fan C, Hou Y and Zhang Y:

Lactylation in tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy resistance:

New mechanisms and challenges. Cancer Lett. 627:2178352025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Brooks GA, Curl CC, Leija RG, Osmond AD,

Duong JJ and Arevalo JA: Tracing the lactate shuttle to the

mitochondrial reticulum. Exp Mol Med. 54:1332–1347. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fan H, Yang F, Xiao Z, Luo H, Chen H, Chen

Z, Liu Q and Xiao Y: Lactylation: Novel epigenetic regulatory and

therapeutic opportunities. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

324:E330–E338. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lv X, Lv Y and Dai X: Lactate, histone

lactylation and cancer hallmarks. Expert Rev Mol Med. 25:e72023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen L, Huang L, Gu Y, Cang W, Sun P and

Xiang Y: Lactate-lactylation hands between metabolic reprogramming

and immunosuppression. Int J Mol Sci. 23:119432022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Li S, Dong L and Wang K: Current and

future perspectives of lysine lactylation in cancer. Trends Cell

Biol. 35:190–193. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yu X, Yang J, Xu J, Pan H, Wang W, Yu X

and Shi S: Histone lactylation: From tumor lactate metabolism to

epigenetic regulation. Int J Biol Sci. 20:1833–1854. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Irizarry-Caro RA, McDaniel MM, Overcast

GR, Jain VG, Troutman TD and Pasare C: TLR signaling adapter BCAP

regulates inflammatory to reparatory macrophage transition by

promoting histone lactylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

117:30628–30638. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang J, Yang P, Yu T, Gao M, Liu D, Zhang

J, Lu C, Chen X, Zhang X and Liu Y: Lactylation of PKM2 suppresses

inflammatory metabolic adaptation in pro-inflammatory macrophages.

Int J Biol Sci. 18:6210–6225. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hua Q, Mi B, Xu F, Wen J, Zhao L, Liu J

and Huang G: Hypoxia-induced lncRNA-AC020978 promotes proliferation

and glycolytic metabolism of non-small cell lung cancer by

regulating PKM2/HIF-1α axis. Theranostics. 10:4762–4778. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Apostolova P and Pearce EL: Lactic acid

and lactate: Revisiting the physiological roles in the tumor

microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 43:969–977. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wu Z, Wu H, Dai Y, Wang Z, Han H, Shen Y,

Zhang R and Wang X: A pan-cancer multi-omics analysis of

lactylation genes associated with tumor microenvironment and cancer

development. Heliyon. 10:e274652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang X, Li Y and Chen Y: Development of a

comprehensive gene signature linking hypoxia, glycolysis,

lactylation, and metabolomic insights in gastric cancer through the

integration of bulk and single-cell RNA-Seq data. Biomedicines.

11:29482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Huang H, Chen K, Zhu Y, Hu Z, Wang Y, Chen

J, Li Y, Li D and Wei P: A multi-dimensional approach to unravel

the intricacies of lactylation related signature for prognostic and

therapeutic insight in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 22:2112024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sun Y, Wang H, Cui Z, Yu T, Song Y, Gao H,

Tang R, Wang X, Li B, Li W and Wang Z: Lactylation in cancer

progression and drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 81:1012482025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zeng Y, Yu T, Lou Z, Chen L, Pan L and

Ruan B: Emerging function of main RNA methylation modifications in

the immune microenvironment of digestive system tumors. Pathol Res

Pract. 256:1552682024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Yang Z, Yan C, Ma J, Peng P, Ren X, Cai S,

Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang S, Wang X, et al: Lactylome analysis suggests

lactylation-dependent mechanisms of metabolic adaptation in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Metab. 5:61–79. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yang H, Zou X, Yang S, Zhang A, Li N and

Ma Z: Identification of lactylation related model to predict

prognostic, tumor infiltrating immunocytes and response of

immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 14:11499892023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mao Y, Zhang J, Zhou Q, He X, Zheng Z, Wei

Y, Zhou K, Lin Y, Yu H, Zhang H, et al: Hypoxia induces

mitochondrial protein lactylation to limit oxidative

phosphorylation. Cell Res. 34:13–30. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zong Z, Xie F, Wang S, Wu X, Zhang Z, Yang

B and Zhou F: Alanyl-tRNA synthetase, AARS1, is a lactate sensor

and lactyltransferase that lactylates p53 and contributes to

tumorigenesis. Cell. 187:2375–2392.e33. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ju J, Zhang H, Lin M, Yan Z, An L, Cao Z,

Geng D, Yue J, Tang Y, Tian L, et al: The alanyl-tRNA synthetase

AARS1 moonlights as a lactyltransferase to promote YAP signaling in

gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 134:e1745872024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhou J, Xu W, Wu Y, Wang M, Zhang N, Wang

L, Feng Y, Zhang T, Wang L and Mao A: GPR37 promotes colorectal

cancer liver metastases by enhancing the glycolysis and histone

lactylation via Hippo pathway. Oncogene. 42:3319–3330. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Miao Z, Zhao X and Liu X: Hypoxia induced

β-catenin lactylation promotes the cell proliferation and stemness

of colorectal cancer through the wnt signaling pathway. Exp Cell

Res. 422:1134392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang L, Niu K, Wang J, Shen W, Jiang R,

Liu L, Song W, Wang X, Zhang X, Zhang R, et al: Nucleolin

lactylation contributes to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

pathogenesis via RNA splicing regulation of MADD. J Hepatol.

81:651–666. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Song F, Hou C, Huang Y, Liang J, Cai H,

Tian G, Jiang Y, Wang Z and Hou J: Lactylome analyses suggest

systematic lysine-lactylated substrates in oral squamous cell

carcinoma under normoxia and hypoxia. Cell Signal. 120:1112282024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wang M, He T, Meng D, Lv W, Ye J, Cheng L

and Hu J: BZW2 modulates lung adenocarcinoma progression through

glycolysis-mediated IDH3G lactylation modification. J Proteome Res.

22:3854–3865. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xie B, Lin J, Chen X, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Fan

M, Xiang J, He N, Hu Z and Wang F: CircXRN2 suppresses tumor

progression driven by histone lactylation through activating the

Hippo pathway in human bladder cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:1512023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang R, Xu F, Yang Z, Cao J, Hu L and She

Y: The mechanism of PFK-1 in the occurrence and development of

bladder cancer by regulating ZEB1 lactylation. BMC Urol. 24:592024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang D, Du G, Chen X, Wang J, Liu K, Zhao

H, Cheng C, He Y, Jing N, Xu P, et al: Zeb1-controlled metabolic

plasticity enables remodeling of chromatin accessibility in the

development of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cell Death Differ.

31:779–791. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pandkar MR, Sinha S, Samaiya A and Shukla

S: Oncometabolite lactate enhances breast cancer progression by

orchestrating histone lactylation-dependent c-Myc expression.

Transl Oncol. 37:1017582023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hou X, Ouyang J, Tang L, Wu P, Deng X, Yan

Q, Shi L, Fan S, Fan C, Guo C, et al: KCNK1 promotes proliferation

and metastasis of breast cancer cells by activating lactate

dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and up-regulating H3K18 lactylation. PLoS

Biol. 22:e30026662024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

He Y, Ji Z, Gong Y, Fan L, Xu P, Chen X,

Miao J, Zhang K, Zhang W, Ma P, et al: Numb/Parkin-directed

mitochondrial fitness governs cancer cell fate via metabolic

regulation of histone lactylation. Cell Rep. 42:1120332023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang X, Ying T, Yuan J, Wang Y, Su X, Chen

S, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Sheng J, Teng L, et al: BRAFV600E restructures

cellular lactylation to promote anaplastic thyroid cancer

proliferation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 30:e2203442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Marcucci F and Rumio C: Tumor cell

glycolysis-at the crossroad of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

and autophagy. Cells. 11:10412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jia M, Yue X, Sun W, Zhou Q, Chang C, Gong

W, Feng J, Li X, Zhan R, Mo K, et al: ULK1-mediated metabolic

reprogramming regulates Vps34 lipid kinase activity by its

lactylation. Sci Adv. 9:eadg49932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sun W, Jia M, Feng Y and Cheng X: Lactate

is a bridge linking glycolysis and autophagy through lactylation.

Autophagy. 19:3240–3241. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ashton TM, McKenna WG, Kunz-Schughart LA

and Higgins GS: Oxidative phosphorylation as an emerging target in

cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 24:2482–2490. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sancho P, Barneda D and Heeschen C:

Hallmarks of cancer stem cell metabolism. Br J Cancer.

114:1305–1312. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Payen VL, Mina E, Van Hée VF, Porporato PE

and Sonveaux P: Monocarboxylate transporters in cancer. Mol Metab.

33:48–66. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cheng Z, Huang H, Li M and Chen Y:

Proteomic analysis identifies PFKP lactylation in SW480 colon

cancer cells. iScience. 27:1086452023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Huang H, Wang S, Xia H, Zhao X, Chen K,

Jin G, Zhou S, Lu Z, Chen T, Yu H, et al: Lactate enhances NMNAT1

lactylation to sustain nuclear NAD+ salvage pathway and

promote survival of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells under

glucose-deprived conditions. Cancer Lett. 588:2168062024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Peng T, Sun F, Yang JC, Cai MH, Huai MX,

Pan JX, Zhang FY and Xu LM: Novel lactylation-related signature to

predict prognosis for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J

Gastroenterol. 30:2575–2602. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Jiang J, Huang D, Jiang Y, Hou J, Tian M,

Li J, Sun L, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Li Z, et al: Lactate modulates

cellular metabolism through histone lactylation-mediated gene

expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol.

11:6475592021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Daw CC, Ramachandran K, Enslow BT, Maity

S, Bursic B, Novello MJ, Rubannelsonkumar CS, Mashal AH,

Ravichandran J, Bakewell TM, et al: Lactate elicits

ER-mitochondrial Mg2+ dynamics to integrate cellular

metabolism. Cell. 183:474–489.e17. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhang R, Li L and Yu J: Lactate-induced

IGF1R protein lactylation promotes proliferation and metabolic

reprogramming of lung cancer cells. Open Life Sci. 19:202208742024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Seo SH, Hwang SY, Hwang S, Han S, Park H,

Lee YS, Rho SB and Kwon Y: Hypoxia-induced ELF3 promotes tumor

angiogenesis through IGF1/IGF1R. EMBO Rep. 23:e529772022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Longhitano L, Vicario N, Tibullo D,

Giallongo C, Broggi G, Caltabiano R, Barbagallo GMV, Altieri R,

Baghini M, Di Rosa M, et al: Lactate induces the expressions of

MCT1 and HCAR1 to promote tumor growth and progression in

glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 12:8717982022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Longhitano L, Giallongo S, Orlando L,

Broggi G, Longo A, Russo A, Caltabiano R, Giallongo C, Barbagallo

I, Di Rosa M, et al: Lactate rewrites the metabolic reprogramming

of uveal melanoma cells and induces quiescence phenotype. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:242022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Yang L, Wang X, Liu J, Liu X, Li S, Zheng

F, Dong Q, Xu S, Xiong J and Fu B: Prognostic and tumor

microenvironmental feature of clear cell renal cell carcinoma

revealed by m6A and lactylation modification-related genes. Front

Immunol. 14:12250232023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Qu J, Li P and Sun Z: Histone lactylation

regulates cancer progression by reshaping the tumor

microenvironment. Front Immunol. 14:12843442023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Li F, Si W, Xia L, Yin D, Wei T, Tao M,

Cui X, Yang J, Hong T and Wei R: Positive feedback regulation

between glycolysis and histone lactylation drives oncogenesis in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 23:902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chen M, Cen K, Song Y, Zhang X, Liou YC,

Liu P, Huang J, Ruan J, He J, Ye W, et al:

NUSAP1-LDHA-glycolysis-lactate feedforward loop promotes Warburg

effect and metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer

Lett. 567:2162852023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Qiao Z, Li Y, Li S, Liu S and Cheng Y:

Hypoxia-induced SHMT2 protein lactylation facilitates glycolysis

and stemness of esophageal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem.

479:3063–3076. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wei X, Chen Y, Jiang X, Peng M, Liu Y, Mo

Y, Ren D, Hua Y, Yu B, Zhou Y, et al: Mechanisms of vasculogenic

mimicry in hypoxic tumor microenvironments. Mol Cancer. 20:72021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang M, Zhao Y, Liu X, Ruan X, Wang P,

Liu L, Wang D, Dong W, Yang C and Xue Y: Pseudogene MAPK6P4-encoded

functional peptide promotes glioblastoma vasculogenic mimicry

development. Commun Biol. 6:10592023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Liu R, Zou Z, Chen L, Feng Y, Ye J, Deng

Y, Zhu X, Zhang Y, Lin J, Cai S, et al: FKBP10 promotes clear cell

renal cell carcinoma progression and regulates sensitivity to the

HIF2α blockade by facilitating LDHA phosphorylation. Cell Death

Dis. 15:642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Luo Y, Yang Z, Yu Y and Zhang P: HIF1α

lactylation enhances KIAA1199 transcription to promote angiogenesis

and vasculogenic mimicry in prostate cancer. Int J Biol Macromol.

222:2225–2243. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Meng Q, Sun H, Zhang Y, Yang X, Hao S, Liu

B, Zhou H, Xu ZX and Wang Y: Lactylation stabilizes DCBLD1

activating the pentose phosphate pathway to promote cervical cancer

progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Meng Q, Zhang Y, Sun H, Yang X, Hao S, Liu

B, Zhou H, Wang Y and Xu ZX: Human papillomavirus-16 E6 activates

the pentose phosphate pathway to promote cervical cancer cell

proliferation by inhibiting G6PD lactylation. Redox Biol.

71:1031082024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Wei S, Zhang J, Zhao R, Shi R, An L, Yu Z,

Zhang Q, Zhang J, Yao Y, Li H and Wang H: Histone lactylation

promotes malignant progression by facilitating USP39 expression to

target PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α signal pathway in endometrial carcinoma.

Cell Death Discov. 10:1212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhao Y, Jiang J, Zhou P, Deng K, Liu Z,

Yang M, Yang X, Li J, Li R and Xia J: H3K18 lactylation-mediated

VCAM1 expression promotes gastric cancer progression and metastasis

via AKT-mTOR-CXCL1 axis. Biochem Pharmacol. 222:1161202024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Li XM, Yang Y, Jiang FQ, Hu G, Wan S, Yan

WY, He XS, Xiao F, Yang XM, Guo X, et al: Histone lactylation

inhibits RARγ expression in macrophages to promote colorectal

tumorigenesis through activation of TRAF6-IL-6-STAT3 signaling.

Cell Rep. 43:1136882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Liu M, Gu L, Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhang L, Xin

Y, Wang Y and Xu ZX: LKB1 inhibits telomerase activity resulting in

cellular senescence through histone lactylation in lung

adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 595:2170252024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Zheng P, Mao Z, Luo M, Zhou L, Wang L, Liu

H, Liu W and Wei S: Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of the

solute carrier family and preliminary exploration of SLC25A29 in

lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 23:2222023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Li L, Li Z, Meng X, Wang X, Song D, Liu Y,

Xu T, Qin J, Sun N, Tian K, et al: Histone lactylation-derived

LINC01127 promotes the self-renewal of glioblastoma stem cells via

the cis-regulating the MAP4K4 to activate JNK pathway. Cancer Lett.

579:2164672023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Yang J, Luo L, Zhao C, Li X, Wang Z, Zeng

Z, Yang X, Zheng X, Jie H, Kang L, et al: A positive feedback loop

between inactive VHL-triggered histone lactylation and PDGFRβ

signaling drives clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression. Int J

Biol Sci. 18:3470–3483. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Jin J, Bai L, Wang D, Ding W, Cao Z, Yan

P, Li Y, Xi L, Wang Y, Zheng X, et al: SIRT3-dependent

delactylation of cyclin E2 prevents hepatocellular carcinoma

growth. EMBO Rep. 24:e560522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Liao J, Chen Z, Chang R, Yuan T, Li G, Zhu

C, Wen J, Wei Y, Huang Z, Ding Z, et al: CENPA functions as a

transcriptional regulator to promote hepatocellular carcinoma

progression via cooperating with YY1. Int J Biol Sci. 19:5218–5232.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Xie B, Zhang M, Li J, Cui J, Zhang P, Liu

F, Wu Y, Deng W, Ma J, Li X, et al: KAT8-catalyzed lactylation

promotes eEF1A2-mediated protein synthesis and colorectal

carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 121:e23141281212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Xiong J, He J, Zhu J, Pan J, Liao W, Ye H,

Wang H, Song Y, Du Y, Cui B, et al: Lactylation-driven

METTL3-mediated RNA m6A modification promotes

immunosuppression of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. Mol Cell.

82:1660–1677.e10. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Yu J, Chai P, Xie M, Ge S, Ruan J, Fan X

and Jia R: Histone lactylation drives oncogenesis by facilitating

m6A reader protein YTHDF2 expression in ocular melanoma.

Genome Biol. 22:852021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Gu X, Zhuang A, Yu J, Yang L, Ge S, Ruan

J, Jia R, Fan X and Chai P: Histone lactylation-boosted ALKBH3

potentiates tumor progression and diminished promyelocytic leukemia

protein nuclear condensates by m1A demethylation of SP100A. Nucleic

Acids Res. 52:2273–2289. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Chen B, Deng Y, Hong Y, Fan L, Zhai X, Hu

H, Yin S, Chen Q, Xie X, Ren X, et al: Metabolic recoding of

NSUN2-mediated m5c modification promotes the progression

of colorectal cancer via the NSUN2/YBX1/m5C-ENO1

positive feedback loop. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23098402024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Takata T, Nakamura A, Yasuda H, Miyake H,

Sogame Y, Sawai Y, Hayakawa M, Mochizuki K, Nakao R, Ogata T, et

al: Pathophysiological implications of protein lactylation in

pancreatic epithelial tumors. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 57:57–66.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Cai D, Yuan X, Cai DQ, Li A, Yang S, Yang

W, Duan J, Zhuo W, Min J, Peng L and Wei J: Integrative analysis of

lactylation-related genes and establishment of a novel prognostic

signature for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

149:11517–11530. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Yang H, Yang S, He J, Li W, Zhang A, Li N,

Zhou G and Sun B: Glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) promotes

lactylation modifications by regulating lactate dehydrogenase A

(LDHA) in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 23:3032023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Yang D, Yin J, Shan L, Yi X, Zhang W and

Ding Y: Identification of lysine-lactylated substrates in gastric

cancer cells. iScience. 25:1046302022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Hu X, Ouyang W, Chen H, Liu Z, Lai Z and

Yao H: Claudin-9 (CLDN9) promotes gastric cancer progression by

enhancing the glycolysis pathway and facilitating PD-L1 lactylation

to suppress CD8+ T cell anti-tumor immunity. Cancer

Pathog Ther. 3:253–266. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Huang ZW, Zhang XN, Zhang L, Liu LL, Zhang

JW, Sun YX, Xu JQ, Liu Q and Long ZJ: STAT5 promotes PD-L1

expression by facilitating histone lactylation to drive

immunosuppression in acute myeloid leukemia. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 8:3912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Gu J, Xu X, Li X, Yue L, Zhu X, Chen Q,

Gao J, Takashi M, Zhao W, Zhao B, et al: Tumor-resident microbiota

contributes to colorectal cancer liver metastasis by lactylation

and immune modulation. Oncogene. 43:2389–2404. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wang J, Liu Z, Xu Y, Wang Y, Wang F, Zhang

Q, Ni C, Zhen Y, Xu R, Liu Q, et al: Enterobacterial LPS-inducible

LINC00152 is regulated by histone lactylation and promotes cancer

cells invasion and migration. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

12:9138152022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Hao B, Dong H, Xiong R, Song C, Xu C, Li N

and Geng Q: Identification of SLC2A1 as a predictive biomarker for

survival and response to immunotherapy in lung squamous cell

carcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 171:1081832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

De Leo A, Ugolini A, Yu X, Scirocchi F,

Scocozza D, Peixoto B, Pace A, D'Angelo L, Liu JKC, Etame AB, et

al: Glucose-driven histone lactylation promotes the

immunosuppressive activity of monocyte-derived macrophages in

glioblastoma. Immunity. 57:1105–1123.e8. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lu X, Zhou Z, Qiu P and Xin T: Integrated

single-cell and bulk RNA-sequencing data reveal molecular subtypes

based on lactylation-related genes and prognosis and therapeutic

response in glioma. Heliyon. 10:e307262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wu X, Mi T, Jin L, Ren C, Wang J, Zhang Z,

Liu J, Wang Z, Guo P and He D: Dual roles of HK3 in regulating the

network between tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages in

neuroblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 73:1222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Wang ZH, Zhang P, Peng WB, Ye LL, Xiang X,

Wei XS, Niu YR, Zhang SY, Xue QQ, Wang HL and Zhou Q: Altered

phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of

FOXP3+CD3+CD56+ natural killer T

(NKT)-like cells in human malignant pleural effusion.

Oncoimmunology. 12:21605582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Hong H, Chen X, Wang H, Gu X, Yuan Y and

Zhang Z: Global profiling of protein lysine lactylation and

potential target modified protein analysis in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Proteomics. 23:e22004322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Cheng Z, Huang H, Li M, Liang X, Tan Y and

Chen Y: Lactylation-related gene signature effectively predicts

prognosis and treatment responsiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 16:6442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Wu Q, Li X, Long M, Xie X and Liu Q:

Integrated analysis of histone lysine lactylation (Kla)-specific

genes suggests that NR6A1, OSBP2 and UNC119B are novel therapeutic

targets for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 13:186422023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Moser CD, Cazanave SC,

Oseini AM, Shire AM, Shridhar V, Sanderson SO and Roberts LR:

Additive effect of apicidin and doxorubicin in sulfatase 1

expressing hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. J

Hepatol. 50:1112–1121. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Wang Y, Pei P, Yang K, Guo L and Li Y:

Copper in colorectal cancer: From copper-related mechanisms to

clinical cancer therapies. Clin Transl Med. 14:e17242024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Sun L, Zhang Y, Yang B, Sun S, Zhang P,

Luo Z, Feng T, Cui Z, Zhu T, Li Y, et al: Lactylation of METTL16

promotes cuproptosis via m6A-modification on FDX1 mRNA

in gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 14:65232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Li W, Zhou C, Yu L, Hou Z, Liu H, Kong L,

Xu Y, He J, Lan J, Ou Q, et al: Tumor-derived lactate promotes

resistance to bevacizumab treatment by facilitating autophagy

enhancer protein RUBCNL expression through histone H3 lysine 18

lactylation (H3K18la) in colorectal cancer. Autophagy. 20:114–130.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Sun X, He L, Liu H, Thorne RF, Zeng T, Liu

L, Zhang B, He M, Huang Y, Li M, et al: The diapause-like

colorectal cancer cells induced by SMC4 attenuation are

characterized by low proliferation and chemotherapy insensitivity.

Cell Metab. 35:1563–1579.e8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Chu YD, Cheng LC, Lim SN, Lai MW, Yeh CT

and Lin WR: Aldolase B-driven lactagenesis and CEACAM6 activation

promote cell renewal and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer

through the Warburg effect. Cell Death Dis. 14:6602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Brown TP and Ganapathy V: Lactate/GPR81

signaling and proton motive force in cancer: Role in angiogenesis,

immune escape, nutrition, and Warburg phenomenon. Pharmacol Ther.

206:1074512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Xia L, Oyang L, Lin J, Tan S, Han Y, Wu N,

Yi P, Tang L, Pan Q, Rao S, et al: The cancer metabolic

reprogramming and immune response. Mol Cancer. 20:282021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Yan F, Teng Y, Li X, Zhong Y, Li C, Yan F

and He X: Hypoxia promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell

stemness, migration, and invasion via promoting glycolysis by

lactylation of SOX9. Cancer Biol Ther. 25:23041612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Duan W, Liu W, Xia S, Zhou Y, Tang M, Xu

M, Lin M, Li X and Wang Q: Warburg effect enhanced by AKR1B10

promotes acquired resistance to pemetrexed in lung cancer-derived

brain metastasis. J Transl Med. 21:5472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Zheng H, Peng X, Yang S, Li X, Huang M,

Wei S, Zhang S, He G, Liu J, Fan Q, et al: Targeting

tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma: Biology,

strategy, and immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 9:652023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Li F, Zhang H, Huang Y, Li D, Zheng Z, Xie

K, Cao C, Wang Q, Zhao X, Huang Z, et al: Single-cell transcriptome

analysis reveals the association between histone lactylation and

cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Drug Resist Updat.

73:1010592024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Li K, Chen MK, Li LY, Lu MH, Shao ChK, Su

ZL, He D, Pang J and Gao X: The predictive value of semaphorins 3

expression in biopsies for biochemical recurrence of patients with

low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Neoplasma. 60:683–689.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Pan J, Zhang J, Lin J, Cai Y and Zhao Z:

Constructing lactylation-related genes prognostic model to

effectively predict the disease-free survival and treatment

responsiveness in prostate cancer based on machine learning. Front

Genet. 15:13431402024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Chaudagar K, Hieromnimon HM, Khurana R,

Labadie B, Hirz T, Mei S, Hasan R, Shafran J, Kelley A, Apostolov

E, et al: Reversal of lactate and PD-1-mediated macrophage

immunosuppression controls growth of PTEN/p53-deficient prostate

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 29:1952–1968. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Chaudagar K, Hieromnimon HM, Kelley A,

Labadie B, Shafran J, Rameshbabu S, Drovetsky C, Bynoe K, Solanki

A, Markiewicz E, et al: Suppression of tumor cell

lactate-generating signaling pathways eradicates murine

PTEN/p53-deficient aggressive-variant prostate cancer via

macrophage phagocytosis. Clin Cancer Res. 29:4930–4940. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Zhang XW, Li L, Liao M, Liu D, Rehman A,

Liu Y, Liu ZP, Tu PF and Zeng KW: Thermal proteome profiling

strategy identifies CNPY3 as a cellular target of gambogic acid for

inducing prostate cancer pyroptosis. J Med Chem. 67:10005–10011.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Jiao Y, Ji F, Hou L, Lv Y and Zhang J:

Lactylation-related gene signature for prognostic prediction and

immune infiltration analysis in breast cancer. Heliyon.

10:e247772024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Deng J and Liao X: Lysine lactylation

(Kla) might be a novel therapeutic target for breast cancer. BMC

Med Genomics. 16:2832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Yu L, Jing C, Zhuang S, Ji L and Jiang L:

A novel lactylation-related gene signature for effectively

distinguishing and predicting the prognosis of ovarian cancer.

Transl Cancer Res. 13:2497–2508. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Zhu Y and Song B, Yang Z, Peng Y, Cui Z,

Chen L and Song B: Integrative lactylation and tumor

microenvironment signature as prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers

in skin cutaneous melanoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

149:17897–17919. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Feng H, Chen W and Zhang C: Identification

of lactylation gene CALML5 and its correlated lncRNAs in cutaneous

melanoma by machine learning. Medicine (Baltimore). 102:e359992023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Pan L, Feng F, Wu J, Fan S, Han J, Wang S,

Yang L, Liu W, Wang C and Xu K: Demethylzeylasteral targets lactate

by inhibiting histone lactylation to suppress the tumorigenicity of

liver cancer stem cells. Pharmacol Res. 181:1062702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Gong H, Xu HM, Ma YH and Zhang DK:

Demethylzeylasteral targets lactate to suppress the tumorigenicity

of liver cancer stem cells: It is attributed to histone

lactylation? Pharmacol Res. 194:1068692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Wang C, Feng F, Pan L and Xu K: Reply to

the letter titled: Demethylzeylasteral targets lactate to suppress

the tumorigenicity of liver cancer stem cells: Is it attributed to

histone lactylation? Pharmacol Res. 194:1068682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Xu H, Li L, Wang S, Wang Z, Qu L, Wang C

and Xu K: Royal jelly acid suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma

tumorigenicity by inhibiting H3 histone lactylation at H3K9la and

H3K14la sites. Phytomedicine. 118:1549402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Guo Z, Tang Y, Wang S, Huang Y, Chi Q, Xu

K and Xue L: Natural product fargesin interferes with H3 histone

lactylation via targeting PKM2 to inhibit non-small cell lung

cancer tumorigenesis. Biofactors. 50:592–607. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Gu J, Zhou J, Chen Q, Xu X, Gao J, Li X,

Shao Q, Zhou B, Zhou H, Wei S, et al: Tumor metabolite lactate

promotes tumorigenesis by modulating MOESIN lactylation and

enhancing TGF-β signaling in regulatory T cells. Cell Rep.

39:1109862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Yue Q, Wang Z, Shen Y, Lan Y, Zhong X, Luo

X, Yang T, Zhang M, Zuo B, Zeng T, et al: Histone H3K9 lactylation

confers temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma via LUC7L2-Mediated

MLH1 intron retention. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23092902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Sun T, Liu B, Li Y, Wu J, Cao Y, Yang S,

Tan H, Cai L, Zhang S, Qi X, et al: Oxamate enhances the efficacy

of CAR-T therapy against glioblastoma via suppressing

ectonucleotidases and CCR8 lactylation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

42:2532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Hu X, Wang J, Chu M, Liu Y, Wang ZW and

Zhu X: Emerging role of ubiquitination in the regulation of

PD-1/PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Ther. 29:908–919. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Yu Y, Huang X, Liang C and Zhang P:

Evodiamine impairs HIF1A histone lactylation to inhibit

Sema3A-mediated angiogenesis and PD-L1 by inducing ferroptosis in

prostate cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 957:1760072023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Cui Z, Li Y, Lin Y, Zheng C, Luo L, Hu D,