Introduction

The circadian clock is a fundamental biological

phenomenon observed across the natural world (1). As an endogenous regulatory system, it

is present in nearly all organisms and has evolved to enable

adaptation to time-dependent environmental changes (2,3).

This system comprises a network of oscillators in which a central

clock synchronizes multiple peripheral clocks in alignment with

light and dietary cycles, thereby coordinating internal rhythms,

regulating metabolism, and influencing the onset and progression of

various diseases (4).

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that

individuals with circadian rhythm disruptions in the central master

clock, such as those caused by shift work or jet lag, have an

elevated risk of developing tumors, digestive disorders,

neurological diseases, immune dysfunction, cardiovascular

conditions and endocrine disorders (5–9).

This suggests that disturbances of the master clock contribute to

the development of diverse pathologies. Similarly, disruptions in

the peripheral circadian clock have been associated with damaging

gene mutations, inflammation and fibrosis in organs such as the

heart, kidneys, lungs and pancreas (10–12).

These findings highlight that both master and peripheral clock

disruptions can drive disease. Importantly, the master and

peripheral clocks interact to regulate physiological and

pathological processes. Light signals are transmitted to the

suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) via the hypothalamic tract, resetting

the central clock, while the peripheral clock is synchronized with

the master clock through neural and hormonal pathways (13–15).

However, external environmental factors may disrupt this

synchronization; for example, in nocturnal animals under food

restriction, the peripheral clock is altered while the central

clock remains unaffected (6,16).

Disruptions in the circadian clock of the liver

contribute to the onset and progression of acute and chronic liver

disorders, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),

alcoholic liver disease (ALD), liver fibrosis (LF) and

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (17–20).

Therapeutic approaches, such as pharmacological interventions,

time-restricted feeding, chronotherapy, phototherapy and

time-dependent pharmacology, have shown potential in the treatment

of circadian rhythm-related disorders (21–24).

The present review summarizes recent advances in the exploration of

the mechanisms underlying the relationship between circadian

rhythms, liver homeostasis and disease. It also discusses

time-based treatment strategies with potential in the management of

liver diseases.

Basic structure and function of the

biological clock

Core molecular oscillation

mechanism

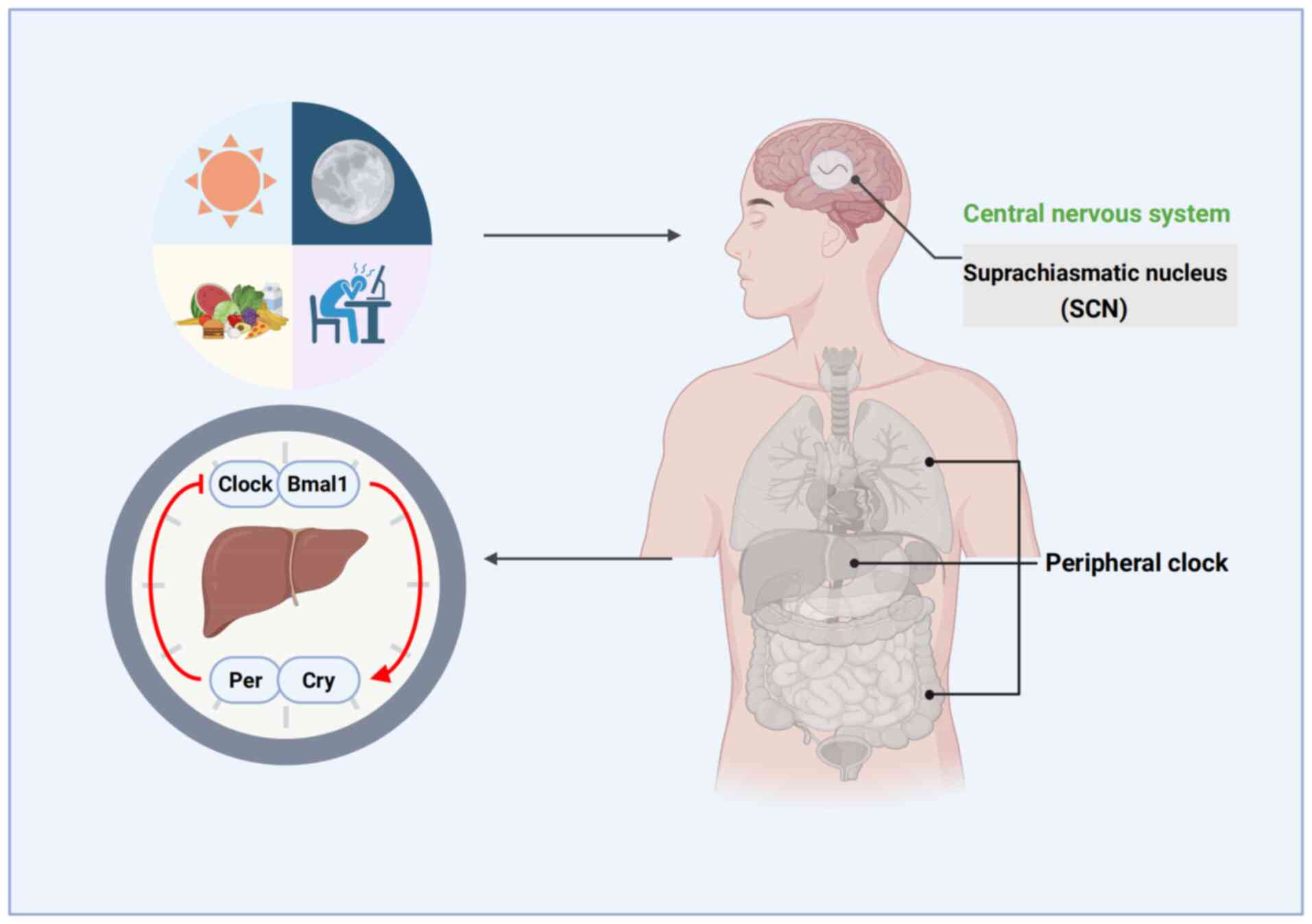

The mammalian circadian clock operates on an ~24-h

cycle, regulating various rhythmic behaviors such as sleep, feeding

and hormone secretion. The SCN, located in the hypothalamus, serves

as the central oscillator of the circadian system, coordinating

peripheral clocks by modulating the nervous system, glucocorticoid

signaling and feeding behavior (14). The circadian system is synchronized

daily by external cues, including light and food. Light is the most

critical factor, conveying information via the retina and the

retinohypothalamic tract to the SCN (15). Peripheral circadian clocks are

present in various tissues and organs, including the liver,

kidneys, adipose tissue, pancreas and heart (25–28)

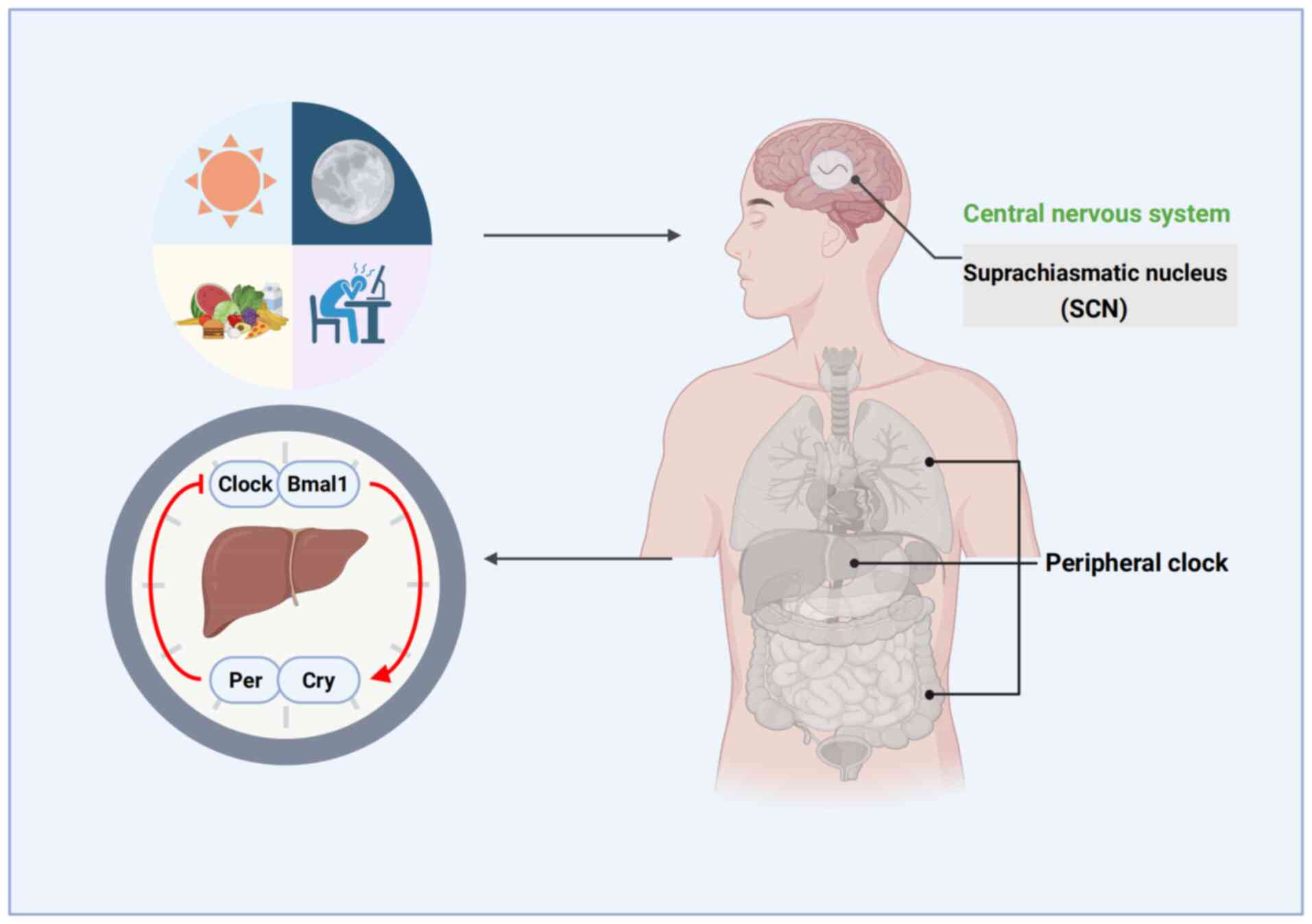

(Fig. 1). The SCN maintains the

synchronized oscillation of peripheral clocks through neuronal

connections and rhythmic humoral factors. At the molecular level,

several core proteins form basic feedback loops for the circadian

clock. These include circadian locomotor output cycles kaput

(Clock), period circadian regulator 1–3 (Per1-3), cryptochrome 1

and 2 (Cry1 and 2), brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1 (Bmal1),

retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor α (RORα) and nuclear

receptor subfamily 1, group D member 1, also known as reverse

erythroblastosis virus α (Rev-erbα) (29–34)

(Table I).

| Figure 1.Regulation process of the central and

peripheral biological clocks. The circadian system undergoes daily

regulation by natural light, food intake and other external cues.

Light serves as the principal zeitgeber, transmitting signals via

the retina and retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic

nucleus, thereby resetting the central pacemaker. While the master

clock resides within the hypothalamic center, peripheral

oscillators exist in the liver, kidneys, adipose tissue, pancreas

and heart, all synchronized by the master clock. Bmal1, brain and

muscle ARNT-like protein 1; Clock, circadian locomotor output

cycles kaput; Cry, cryptochrome; Per, period circadian

regulator. |

| Table I.Circadian clock proteins and their

functions. |

Table I.

Circadian clock proteins and their

functions.

| Circadian gene | Circadian

function |

|---|

| Bmal1 | bHLH-PAS

domain-containing transcription factor; positive regulator |

| Clock | bHLH-PAS

domain-containing transcription factor with histone

acetyltransferase activity; co-activator of Per-Cry

transcription; positive regulator |

| Cry1/2 | Negative

regulator/co-repressor of the Clock-Bmal1 complex |

| Per1/2 |

PAS-domain-containing protein;

co-repressor of the Clock-Bmal1 complex; negative regulator |

| PGC-1α | Transcriptional

coactivator |

| PPARg | Regulator of

metabolism and adipocyte differentiation |

|

Rev-erbα | Nuclear receptor;

repressor of Bmal1 transcription and regulator of

clock-controlled genes; negative regulator |

| RORα | Activator of

Bmal1 transcription; regulator of clock-controlled

genes |

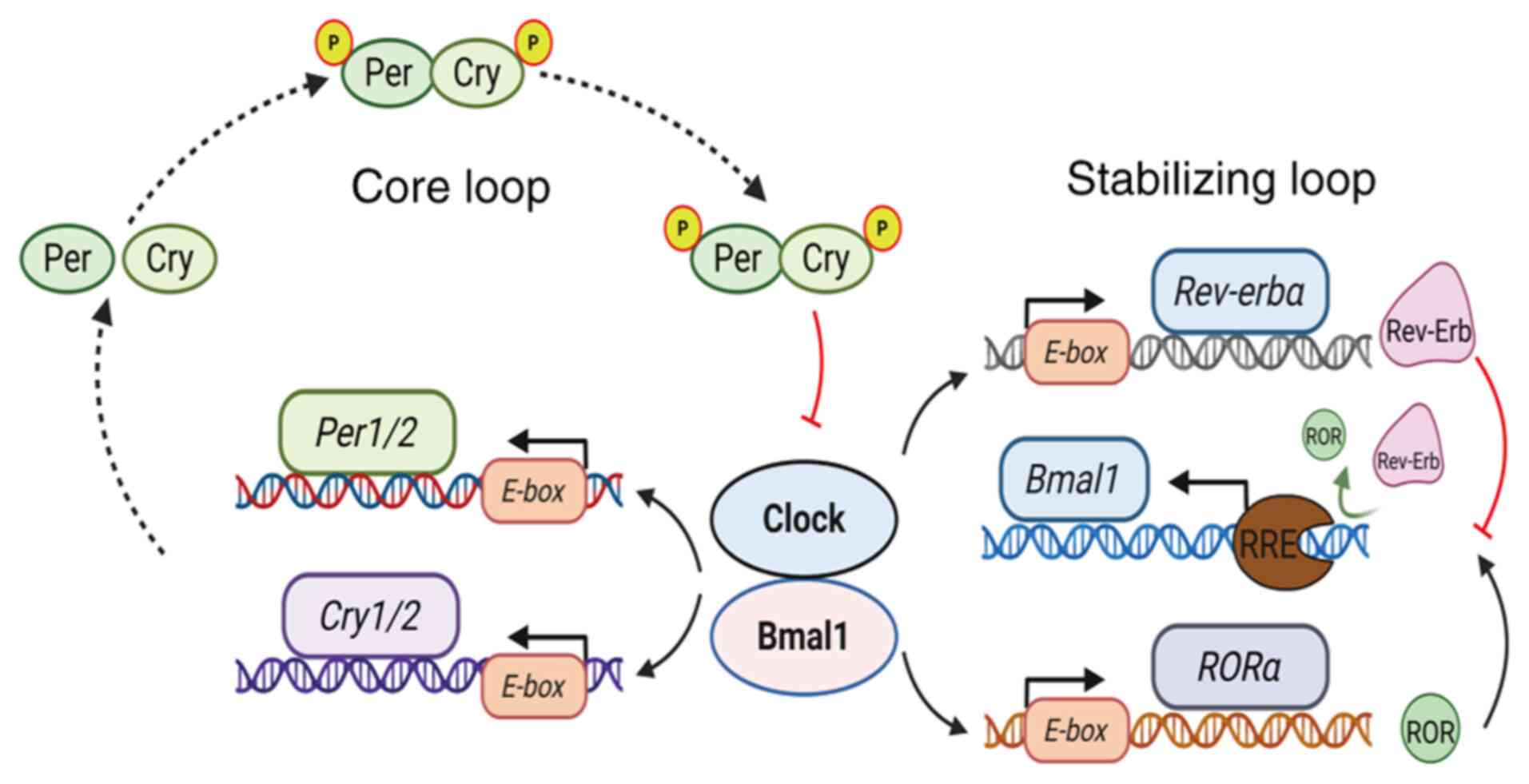

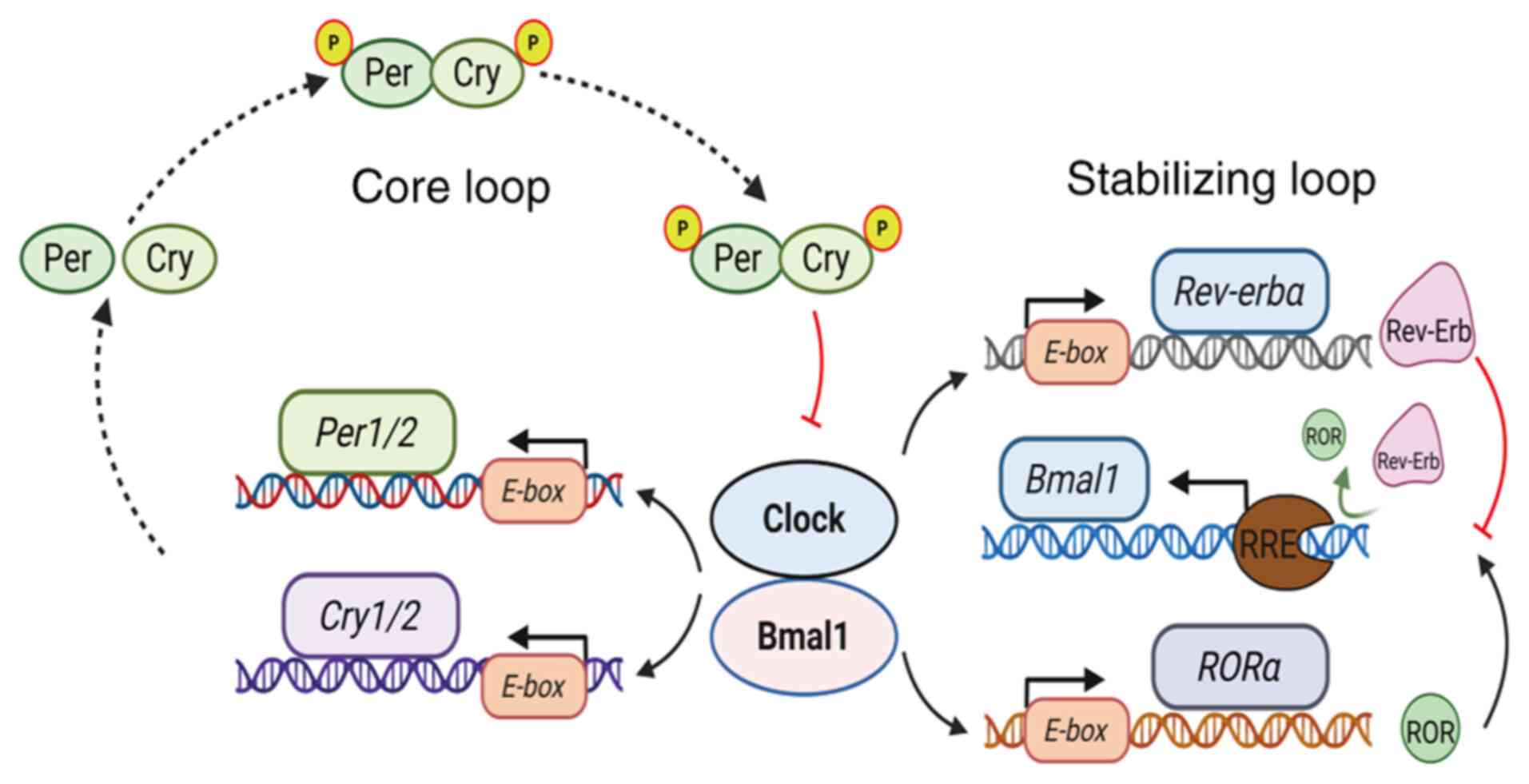

The core feedback loop of the circadian clock begins

with the heterodimerization of Bmal1 and Clock, which activates

Per and Cry genes, along with other circadian

regulators, by binding to E-box elements in their promoters

(13,32,33).

As Cry protein accumulates in the cytosol, it binds with Per

protein to form a stable complex that re-enters the nucleus. This

complex binds to the Bmal1-Clock dimer, inhibiting its

transcriptional activity and reducing the synthesis of Per and Cry

proteins. This negative feedback cycle generates the oscillatory

expression of circadian clock molecules (13,14,34).

A second stabilizing loop involves Bmal1 expression. The

Bmal1-Clock dimer binds to E-box elements in the promoters of the

Rev-erbα and RORα genes. The Rev-erbα and RORα

proteins compete for the RRE site on the Bmal1 promoter,

with RORα activating Bmal1 transcription and Rev-erbα

inhibiting it (14) (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Schematic diagram of the liver

circadian clock. The liver clock is composed of three parts: The

input pathway, central oscillator and output pathway. The central

oscillator comprises two regulatory loops: The core loop and the

stabilizing loop. In the core loop, Bmal1 and Clock form

heterodimers in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus, where

they bind to E-box sequences in the promoters of target

genes Per and Cry, initiating their transcription. As

Cry protein accumulates in the cytosol, it combines with Per

protein to form a stable complex that re-enters the nucleus and

binds to the Bmal1-Clock heterodimer, inhibiting its

transcriptional activity and reducing Per and Cry protein

synthesis. This cycle forms the oscillatory expression of circadian

clock molecules. The stabilizing loop regulates Bmal1 expression.

Bmal1-Clock dimers bind to E-box elements in the promoters

of the nuclear receptor genes Rev-erbα and RORα,

activating the transcription of Rev-erbα and RORα,

which compete for the RRE site of the Bmal1 promoter: RORα

activates Bmal1 expression, while Rev-erbα inhibits it, thereby

maintaining the stability of the circadian rhythm (32–34).

Bmal1, brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1; Clock, circadian

locomotor output cycles kaput; Cry, cryptochrome; P, phosphor; Per,

period circadian regulator; Rev-erbα, reverse erythroblastosis

virus α; RORα, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor

α. |

Physiological function of the

biological clock

Participating in metabolic balance

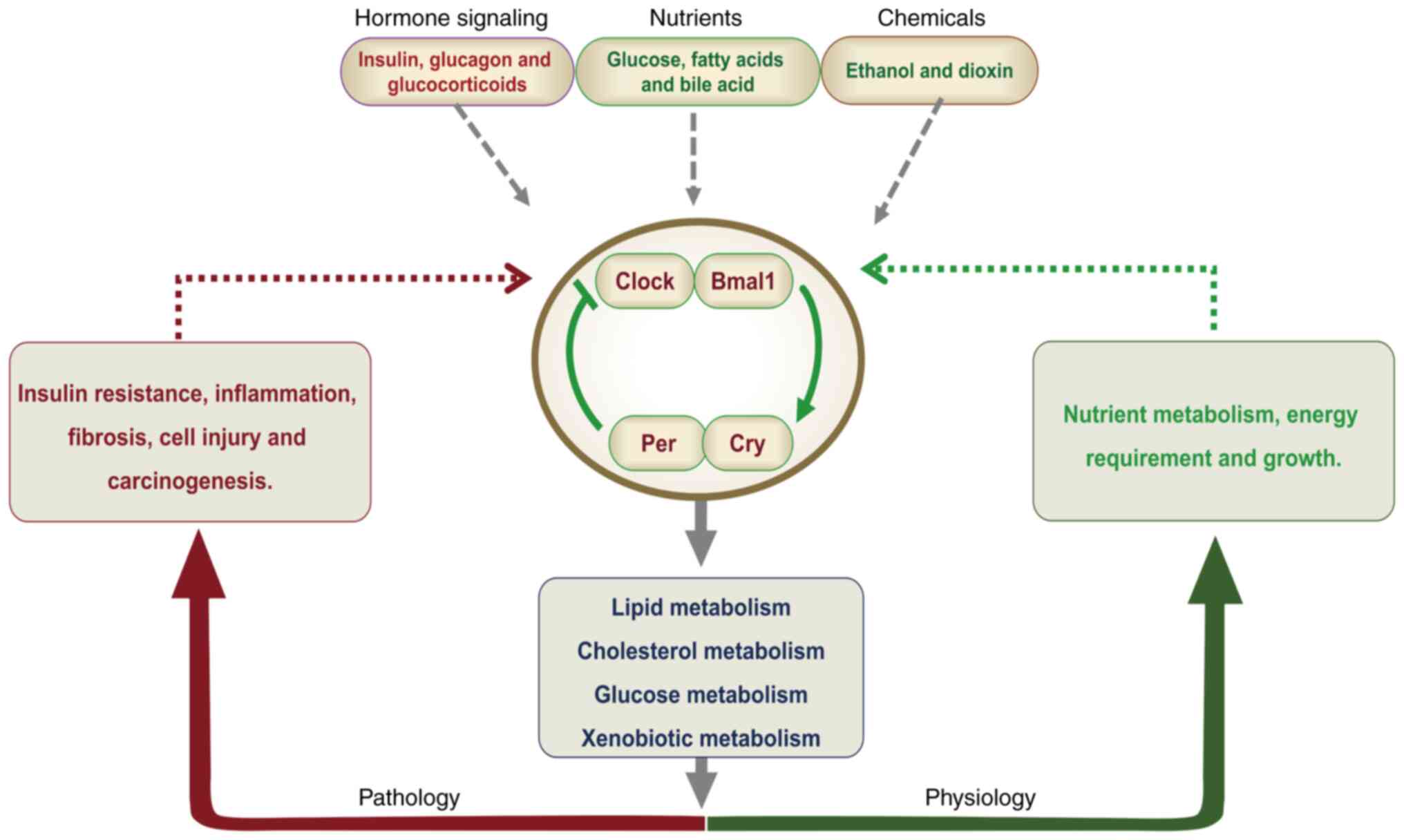

The biological clock regulates circadian rhythms as

well as various physiological and metabolic processes within the

body. Disruptions in core circadian clock genes can lead to

metabolic disturbances, affecting the metabolism of sugars, lipids

and bile acids (BAs) (Fig. 3)

(35–37). For example, mice with

liver-specific knockout (KO) of the Bmal1 gene exhibit

dysregulated expression of glucose-regulated genes, leading to

hypoglycemia and increased glucose uptake following fasting

(38). In addition, Bmal1

KO mice exhibit elevated levels of circulating triglycerides (TGs)

and free fatty acids (FFAs), along with increased hepatic fat

accumulation (39). Furthermore,

when these mice are fed a high-cholesterol diet, they exhibit

excessive cholesterol accumulation in the liver compared with that

in wild-type (WT) mice. This may occur due to the circadian

dysregulation of genes involved in cholesterol metabolism,

including 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, low-density

lipoprotein receptor and cytochrome P450 7A1 (CYP7A1), the

gene encoding cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (40). In addition, Clock regulates the

circadian rhythm of hepatic glycogen synthesis by transcriptionally

activating glycogen synthase 2 (41). In a diabetic mouse model, the

overexpression of Cry1 or Cry 2 protein interferes with cyclic

adenosine monophosphate-mediated gluconeogenesis, which reduces

fasting blood glucose levels in these mice (42). Furthermore, Rev-erbα KO mice

exhibit abnormal BA metabolism and altered expression of CYP7A1. In

mice, Rev-erbα regulates BA and CHOL biosynthesis by modulating the

expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c

(SREBP-1c) and CYP7A1. The activity of Rev-erbα is regulated by the

oxysterol-mediated activation of liver X receptor signaling

(43). These findings highlight

the critical role of clock genes and proteins in metabolic

regulation. In addition, clock genes interact with other signaling

pathways to maintain metabolic homeostasis, ensuring efficient

energy utilization and the timely synthesis of essential

biomolecules.

Regulating endocrine rhythm

The expression patterns of circadian clock genes not

only govern the sleep-wake cycle but also play a pivotal role in

the regulation of human metabolism, growth, development and

emotional well-being. For example, melatonin secretion promotes

sleep, modulates immune function and exerts antioxidant effects. It

indirectly protects against oxidative stress by upregulating the

expression of glutathione and antioxidant enzymes such as

superoxide dismutase and catalase (44). Melatonin, which is secreted by the

pineal gland and regulated by the hypothalamic SCN, follows a

distinct circadian rhythm, peaking at night and decreasing during

the day (45). In turn, melatonin

provides feedback that influences the SCN, thereby modulating the

oscillation of core clock genes (42).

Xiang et al (46) investigated the differential

expression of core circadian clock genes, including Clock,

Bmal1, Per2, as well as clock-controlled genes (CCGs) in

MCF-10A human mammary epithelial cells and MCF-7 breast cancer

cells, focusing on the regulatory role of melatonin. The study

revealed that circadian gene oscillations are impaired in breast

cancer cells, and melatonin partially restores rhythmicity by

activating melatonin receptor 1, thereby inhibiting RORα

transcriptional activity and leading to reduced Bmal1

promoter activity (46).

The morning surge in cortisol not only facilitates

wakefulness but also contributes to stress responses by enhancing

alertness and the adaptive capacity of the body (47–49).

Cortisol suppresses Bmal1 gene transcription by promoting

Cry expression, thereby regulating its own circadian peak (50). Glioblastoma cells can synchronize

their biological clock with the host circadian rhythm in response

to cortisol signaling via Bmal1 and Cry genes, and

the inhibition of cortisol signaling or Bmal1 function

significantly suppresses tumor growth (50).

Quagliarini et al (51) explored how the glucocorticoid

receptor (GR) regulates hepatic metabolism through circadian

chromatin binding. The study identified synergistic interactions

between the GR and core clock genes. Specifically, the GR

cooperates with Clock and Bmal1 to co-regulate genes involved in

carbohydrate, lipid and amino acid metabolism, including peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), CD36 and

4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase. In addition, GR directly

influences core clock components: GR binding sites are present in

the promoters or enhancers of all core clock genes, including

Per1, Per2 and Rev-erbα. The expression of Per1 and

Per2 is induced by GR and Clock/Bmal1, with GR binding preceding

the accumulation of Per1 and Per2. By contrast, GR suppresses

Rev-erbα transcription, while Cry1 and Cry2 inhibit the

GR-mediated activation of gluconeogenic genes, such as

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (Pck1), through direct

interaction (51). These findings

enhance our understanding of the roles of GR and circadian clock

genes in hepatic metabolic regulation and offer new insights and

strategies for the treatment of metabolic disorders.

The secretion of growth hormone (GH) during deep

sleep is essential for the growth and repair of bones, muscles and

visceral organs (52,53). A study performed by Schoeller et

al (54) demonstrated that

male Bmal1 KO mice exhibit feminized GH secretion patterns,

characterized by increased pulse frequency, reduced regularity and

shortened trough periods. In addition, liver-specific Bmal1

KO mice display intermediate GH pulsatility patterns, lying between

those of global Bmal1 KO and WT mice, suggesting that

Bmal1 regulates GH secretion in tissues other than the

liver. Notably, serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels

are significantly lower in Bmal1 KO mice compared with WT

controls, while hepatic IGF-1 mRNA levels are elevated,

indicating disruption of the IGF-1/GH feedback loop. By contrast,

liver-specific Bmal1 KO mice show no significant difference

in serum IGF-1 levels compared with WT controls, suggesting the

involvement of extrahepatic mechanisms in IGF-1 regulation

(54). This research highlights

the critical role of Bmal1 in the GH axis and hepatic metabolism,

offering new insights into the interaction between the circadian

clock and endocrine regulation.

The oscillatory secretion of sex hormones and

thyroid hormones plays a vital role in the regulation of

reproductive function and basal metabolic rate, thereby maintaining

reproductive health and energy balance (55,56).

Sex steroids such as estrogen and testosterone also exhibit

circadian rhythmicity. By binding to their respective receptors,

these hormones modulate the expression of core circadian clock

genes, influencing overall circadian rhythms (15,57).

Research has revealed sex-specific differences in the distribution

and effects of estrogen and testosterone within the SCN. Estrogen

primarily stabilizes the central circadian clock by modulating

astrocytes in the SCN shell subregion, while testosterone

influences the responsiveness of the clock to light signals by

affecting neuronal activity in the SCN core (58,59).

Circadian rhythms often undergo significant changes

with aging, and thyroid function is also subject to circadian

regulation (60). The expression

of core circadian regulators Bmal1 and Clock is downregulated in

aging thyroid follicular epithelial cells, suggesting a decline in

circadian regulatory capacity, contributing to age-related

circadian disruptions (60).

Furthermore, the downregulation of Bmal1 expression suppresses the

expression of NF-κB inhibitor a, leading to persistent activation

of the NF-κB signaling pathway. This chronic activation promotes

thyroid cell senescence (60).

These findings indicate that circadian rhythm disruption

accelerates thyroid functional decline by inducing thyroid cell

senescence, providing a theoretical framework for understanding

thyroid aging and potential strategies to maintain thyroid

function.

Regulating immunity and cell

repair

Circadian clock genes regulate immune system

functions through intricate molecular mechanisms (61). Liu et al (62) demonstrated that the administration

of concanavalin A to mice at the start of the light phase leads to

more severe liver injury and inflammation, evidenced by elevated

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

levels and increased necrotic areas, compared with those induced by

administration at the beginning of the rest phase. This effect is

mediated by rhythmic regulation of the Bmal1-jun B proto-oncogene

(Junb) axis in macrophages. Specifically, Bmal1 protein directly

binds to the Junb promoter, enhancing its transcription.

Junb then activates the AKT/ERK signaling pathway, promoting the

secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6,

in M1 macrophages (62). These

findings deepen our understanding of how circadian regulation

influences immune responses in liver diseases. In addition, Bmal1

modulates the transcriptional activity of nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2 (NRF2) in macrophages by binding to E-box

sequences within the NRF2 gene promoter. This regulation

influences antioxidant responses and IL-1β production (63). Bmal1 deficiency reduces NRF2

activity, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species

and excessive IL-1β secretion, thereby inducing a pro-inflammatory

phenotype (63). These findings

provide mechanistic insights into the circadian regulation of

immune responses in liver diseases and suggest that targeting the

Bmal1-NRF2-IL-1β axis may offer therapeutic benefits in

inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and

sepsis.

Circadian clock genes play a critical role in

cellular repair by ensuring that damaged cells are restored at

optimal times to maintain homeostasis (64). Peng et al (64) demonstrated that Bmal1 collaborates

with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α to bind the E'-box motif in the

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase X promoter, driving rhythmic

transcriptional activity and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)

metabolic flux, which is essential for supplying the nucleotide

precursors, such as ribose-5-phosphate, and NADPH required for DNA

replication and repair. Chronodisruption, due to Bmal1 KO or

mistimed feeding, impairs PPP function, leading to nucleotide

deficiency, oxidative stress and delayed hepatocyte S-phase

progression. This compromises post-hepatectomy regeneration,

exacerbates DNA damage-induced cellular senescence, and promotes

inflammation through the stimulator of interferon genes pathway.

These findings highlight how the circadian clock coordinates tissue

regeneration through metabolic reprogramming, emphasizing the

critical role of nucleotide availability in repair processes

(64). They also provide new

perspectives on circadian-immune interactions and suggest potential

therapeutic targets for disorders associated with immune

dysfunction and cellular damage.

Neurological and behavioral

regulation

Circadian clock genes precisely regulate behavioral

rhythms through a tripartite pathway involving molecular

oscillatory networks, SCN-based synchronization mediated by cilia

and glial cells, and coordination with peripheral organs (65). Genetic variations or aberrant

expression of these genes are associated with neurobehavioral

disorders, including sleep disorders, major depressive disorder and

anxiety. For example, Bmal1-KO rhesus monkeys exhibit

disrupted locomotor rhythms, fragmented sleep and psychiatric

abnormalities (66).

Mechanistically, SCN astrocytes rhythmically release γ-aminobutyric

acid (GABA) to synchronize neuronal oscillations. Inhibition of

GABA synthesis leads to circadian desynchronization, which has been

suggested to increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease (67). These findings underscore the

essential role of circadian clock genes in neural and behavioral

regulation.

Disruption of circadian rhythm

The biological clock uses environmental signals to

optimize energy use, enabling the body to adapt to cycles of rest

and activity, as well as eating and fasting within the circadian

rhythm (68,69). Factors such as sleep deprivation

(70), sleep quality (71,72),

exposure to nighttime light (73),

shift work (74) and altered

feeding patterns (75) can disrupt

circadian timing. Such disruptions may impair metabolic homeostasis

and contribute to the development of various diseases.

Shortened sleep duration leads to marked metabolic

disturbances (70,76). In animal models, restricted sleep

results in increased leptin secretion, heightened lipogenesis and

elevated appetite, all of which contribute to obesity (77). A meta-analysis of 11 longitudinal

studies confirmed that inadequate sleep increases the risk of

becoming overweight or obese (78). Furthermore, sleep deprivation can

interfere with the expression of core circadian clock genes,

including Per1 (77),

contributing to sleep-wake cycle disorders by altering the

rhythmicity of physiological processes such as body temperature and

hormone secretion.

Sleep quality is influenced by multiple factors,

including potential sleep disorders, eating times and environmental

factors such as alcohol and caffeine consumption (79,80).

In young, healthy adults without total sleep deprivation,

interruptions in light or slow-wave sleep for three consecutive

nights lead to reduced insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose

tolerance (81).

The industrialization of society has led to a

substantial increase in nighttime exposure to artificial light,

which alters the circadian rhythm and disrupts the biological clock

(82). Individuals engaged in

night shift work are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects

of excessive nighttime light exposure (83). A meta-analysis of 13 studies

revealed that such workers face a significantly higher risk of

developing metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, a dose-response

relationship between the duration of night shift work and the risk

of metabolic syndrome was identified, further supporting the

association between circadian disruption and metabolic disease

(73).

Eating time has been identified as an independent

time cue for the peripheral circadian oscillator (84). Shifts in eating patterns can lead

to elevated plasma glucose and insulin levels, as well as reduced

nighttime plasma peaks of melatonin and leptin, all of which are

associated with the onset of metabolic syndrome (75,85).

The interplay between eating time, peripheral circadian rhythms and

hormonal fluctuations may represent a fundamental mechanism linking

eating habits to metabolic diseases. Further human studies are

necessary to determine the optimal timing of food intake and its

association with circadian rhythms.

The regulatory mechanisms of the biological clock

are both complex and precise, allowing it to respond to

environmental cues and anticipate future changes. Disruption of

this system impairs homeostasis, thereby increasing the risk of

metabolic disorders.

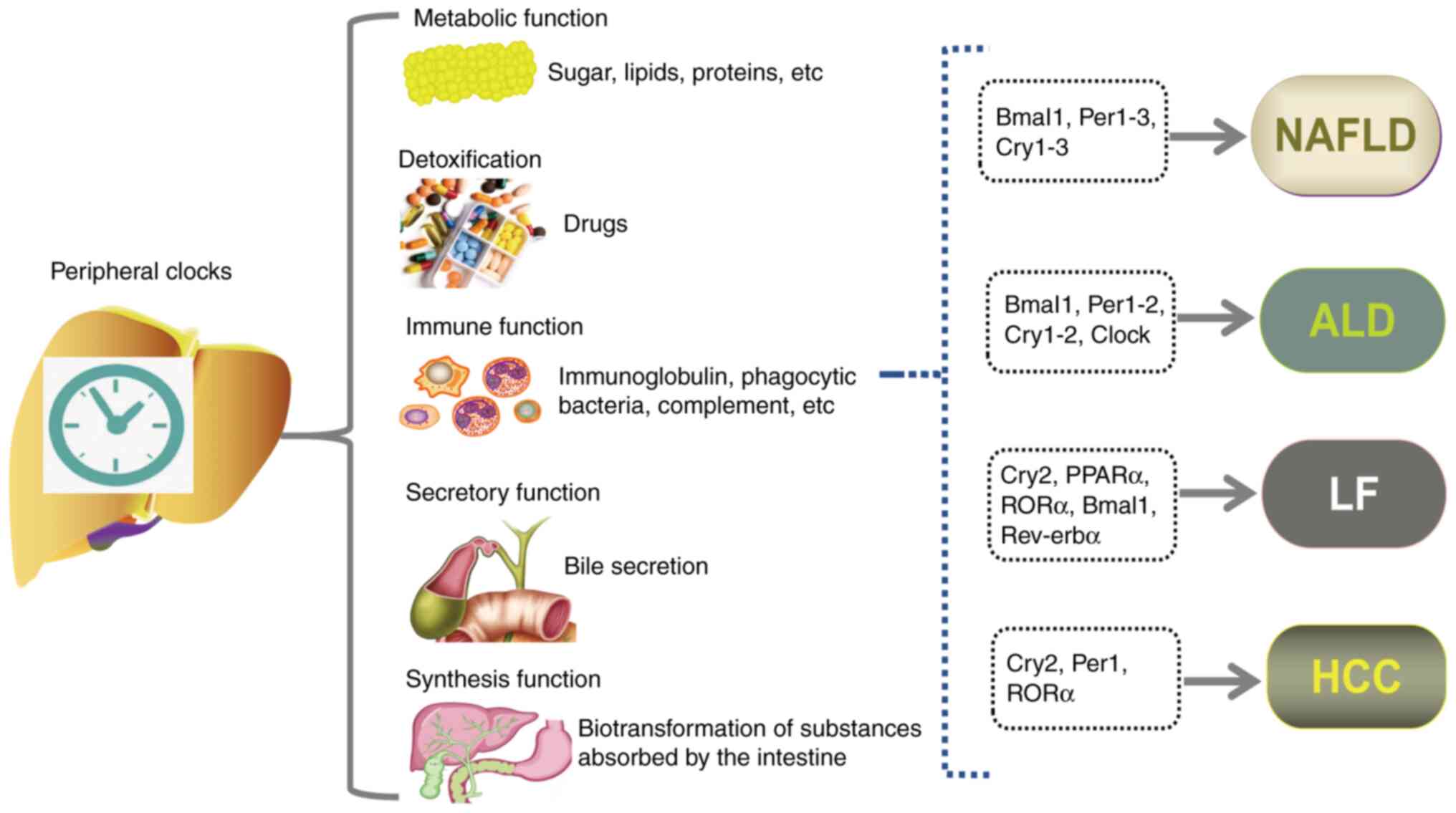

Circadian clock genes and liver

diseases

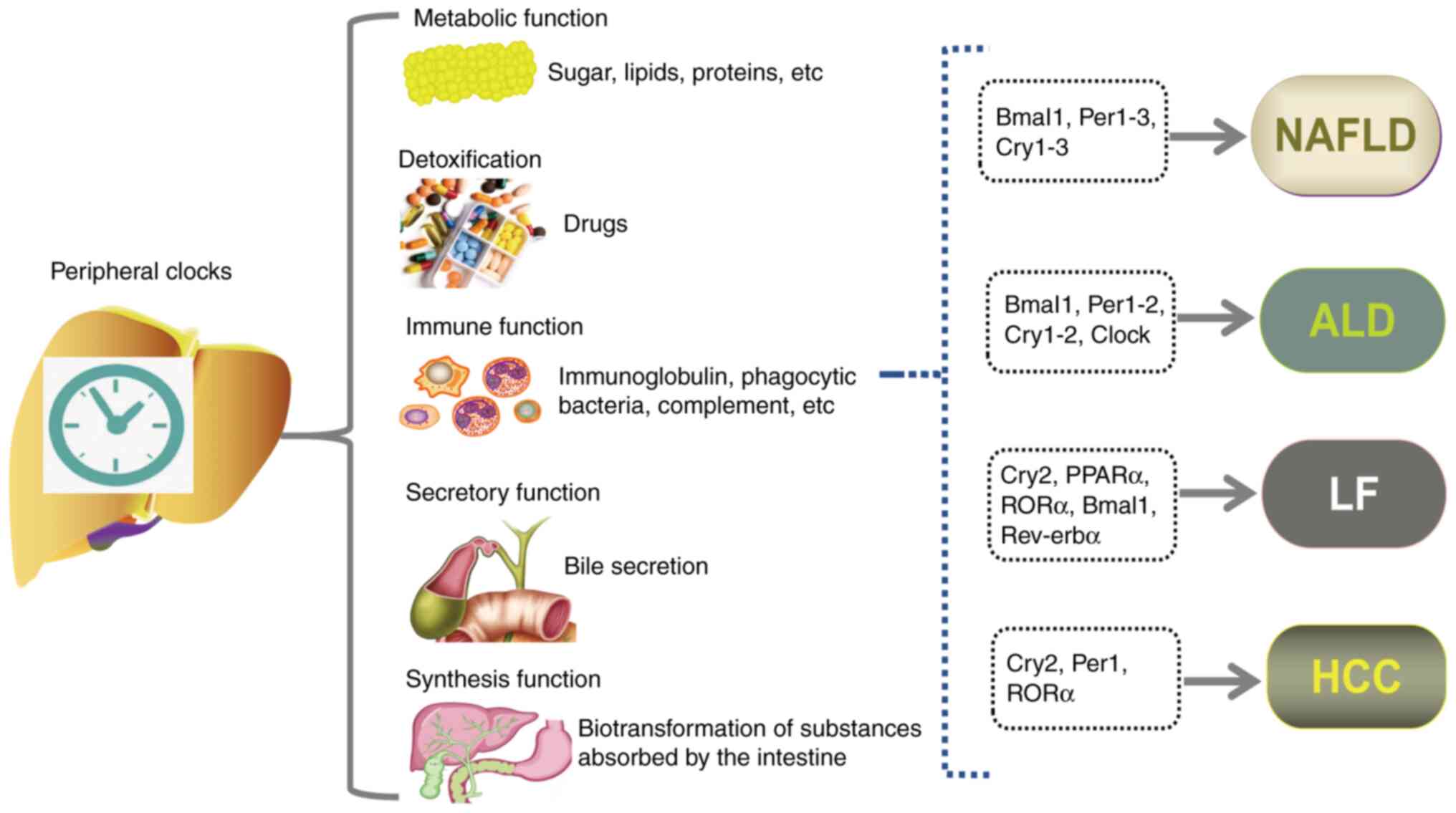

The liver plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of

metabolic homeostasis, performing vital functions such as

regulating blood glucose and ammonia levels, detoxifying drugs,

synthesizing bile, and storing and transforming nutrients (86,87).

Studies have demonstrated that cell-autonomous rhythm oscillators

exist in peripheral organs, including the liver, where they exert

significant effects on the metabolism of nutrients and exogenous

substances. Furthermore, key genes involved in hepatic metabolic

functions also exhibit circadian rhythms and reciprocally regulate

the hepatic circadian clock system (17,88,89).

Disruptions in the circadian clock of the liver can accelerate the

progression of liver diseases, including NAFLD, ALD, LF and HCC

(90–93) (Fig.

4 and Table II); conversely,

these diseases can also impair circadian clock function.

| Figure 4.Impact of circadian clock disturbance

on liver diseases. The liver performs multiple critical functions,

including metabolism, detoxification, immune defense, secretion and

synthesis. Disruption in the expression of circadian clock genes

within the liver can impair its normal physiological functions,

contributing to the pathogenesis of liver diseases, including

NAFLD, ALD, LF and HCC. ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; Bmal1,

brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1; Clock, circadian locomotor

output cycles kaput; Cry, cryptochrome; HCC, hepatocellular

carcinoma; LF, liver fibrosis; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease; Per, period circadian regulator; PPAR, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor; Rev-erbα, reverse erythroblastosis

virus α; RORa, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor

α. |

| Table II.Molecular mechanisms associated with

circadian clock dysfunction and liver disease. |

Table II.

Molecular mechanisms associated with

circadian clock dysfunction and liver disease.

| Disease | Mechanism | Impact | (Refs.) |

|---|

| NAFLD | Bmal1↓ → PPARγ↓ →

CD36↓ → fatty acid intake↓; Bmal1↓ → SIRT2↓ → inflammation↑; PPARα↓

→Bmal1↓ → steatosis↑ | Aggravation | (99,101,103) |

| ALD | Alcohol → NAD/NADH

ratio↓ → Clock/Bmal1↓ → bile acid synthesis↓, inflammation↑; Clock

mutation → serum LPS↑ → inflammation↑; SHP↓ → Rev-erbα↓ → CHOP↓ →

inflammation↑; | Aggravation | (112,114,115,116) |

|

| Bmal1↓ → AKT↓ →

ChREBP↓ → lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation↓ |

|

|

| LF | Per2↓ → CHOP↓ →

TRAIL-R2↓ → HSC apoptosis↓; Per2↓ → CYP7A1, NTCP↓ → accumulation of

bile acids↑; Per2↓ → α-SMA↑ → collagen deposition↑; Bmal1↓,

Rev-erbα↓ → TGF-β/Smad↓ → Col1α, α-SMA↑ → HSC activation↑ | Aggravation | (92,127,128,130) |

|

| Bmal1↑ → IDH1↑,

α-KG↑, HK2↓, PKM2↓ → glycolysis↓ → HSC activation↓ | Alleviation | (131) |

| HCC | Per1/2↓, Cry1/2↓,

Rev-erbα↓ → c-Myc↑, c-Fos↑, FAH↓, Nr1h4↓ → inflammation and

EMT↑ | Aggravation | (142) |

NAFLD

The pathogenesis of NAFLD remains incompletely

understood, and likely involves a multifactorial interplay of

genetic and environmental factors (94). Given the role of circadian rhythms

in metabolic homeostasis, disruptions to these rhythms may

contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome and NAFLD

(95,96). For example, Clock mutant

mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) exhibit significantly higher hepatic

TG levels than those observed in control mice. Similarly,

Bmal1 KO mice develop hepatic steatosis even when fed a

standard chow diet (97),

suggesting that circadian disruption is a key predisposing factor

for liver pathology. In addition, a study of WT mice fed an HFD for

11 months identified upregulated expression levels of genes

associated with gluconeogenesis, such as Pck1, and genes

associated with lipid metabolism, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase

kinase 4. The hepatic expression levels of the core clock genes

Bmal1, Per1-3, Cry1 and Cry2 were also significantly

elevated in these mice (98),

indicating that chronic HFD intake disrupts metabolic rhythms by

altering the expression of circadian genes, thereby exacerbating

obesity and metabolic syndrome. The interaction between circadian

clock genes and energy metabolism pathways, encompassing glucose

and lipid metabolism as well as fluid-electrolyte balance, may

underpin these disruptions.

A recent study found that Bmal1 KO mice fed

an HFD for 20 weeks exhibited significantly lower fasting blood

glucose, insulin levels and homeostatic model assessment of insulin

resistance values compared with those of HFD-fed WT controls.

Additionally, glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity were

markedly improved in the KO mice. Liver weight and hepatic TG

content in the KO group were reduced by ~50% compared with those in

the controls, accompanied by significantly fewer lipid vacuoles and

a reduction in lipid droplet deposition (99). Mechanistic analysis revealed that

Bmal1 deficiency mitigated HFD-induced obesity and NAFLD by

suppressing the PPARγ-CD36 pathway, thereby reducing hepatic fatty

acid uptake (99). This was the

first study to implicate Bmal1 in the regulation of hepatic lipid

uptake via the PPARγ-CD36 axis, suggesting a novel therapeutic

target for NAFLD. However, it did not establish a direct regulatory

relationship between PPARγ and Bmal1, highlighting that further

experimental validation is necessary.

Saturated fatty acids can disrupt circadian rhythms

(100). Palmitic acid, the most

abundant circulating saturated fatty acid, has been shown to induce

liver cell toxicity and inflammation. Using the PH5CH8

non-cancerous immortalized hepatocyte cell line and HepG2 liver

cancer cells, Aggarwal et al (101) revealed that palmitic acid induces

hepatocyte lipotoxicity and lipoinflammation by disrupting the

Bmal1-sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) axis. Specifically, it suppresses the

chromatin-binding capacity of Bmal1 and impairs its interaction

with E-box elements in the SIRT2 promoter, thereby

downregulating SIRT2 transcription. The study also found that in

the liver tissues of patients with NAFLD, Bmal1 expression levels

positively correlate with SIRT2 levels, and Bmal1 nuclear

localization is significantly decreased during cirrhosis (101). This study was the first to

identify Bmal1 as a direct transcriptional regulator of SIRT2 and

implicate palmitic acid-induced circadian disruption in hepatic

inflammation. Activation of the Bmal1-NAD+-SIRT2 axis is

thus suggested to be a novel therapeutic strategy for

NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), while SIRT2 and Bmal1

levels may serve as biomarkers for NAFLD progression. However,

given the small sample size, with only 10 healthy controls and 15

NAFLD cases, further clinical validation is necessary before these

findings can be translated into clinical practice.

PPARα is a target gene of the Clock/Bmal1

heterodimer and contributes to the upregulation of Bmal1 expression

in peripheral tissues. In PPARα KO mouse models,

Bmal1 mRNA levels remain stable in most peripheral tissues

but are significantly decreased in the liver compared with those in

WT mice, indicating the critical role of PPARα in the circadian

regulation of the liver (102).

One study demonstrated that hepatic PPARα mRNA exhibits

diurnal oscillations in WT mice, peaking during the light phase and

declining in the dark phase (103), suggesting rhythmic regulation of

PPARα expression. In addition, fatty acid synthase (FASN)

and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) mRNA levels markedly

increase during the dark (feeding) phase of WT mice, but not in

PPARα KO mice, which instead exhibit persistently low

expression levels (103). This

finding underscores the role of PPARα as a regulator of the

circadian rhythm of hepatic lipid metabolism genes. Following

prolonged fasting, both systemic PPARα−/− and

liver-specific PPARαhep-/− mice develop hepatic

steatosis. After 6 months of chronic HFD intervention, PPARα

KO mice exhibit exacerbated hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis

compared with WT controls. However, PPARα agonists prevent

steatohepatitis and fibrosis and even ameliorate existing fibrosis

in mice with steatohepatitis (103). These results highlight

circadian-regulated PPARα as a critical factor in the pathogenesis

of NAFLD.

Sleep deprivation can alter the circadian rhythm of

GH and testosterone secretion; however, following liver

transplantation, improvements in testosterone and GH levels,

together with reduced sleep disturbances associated with NAFLD,

suggest that the liver plays a pivotal role in the regulation of

both endocrine and circadian rhythms (78,104). In humans, sleep-wake disorders

disrupt the secretion of insulin, leptin and norepinephrine, while

circadian rhythm disturbances caused by insufficient sleep increase

insulin resistance (78,105).

Miyake et al (106) conducted a study of 2,429

participants, including 669 men and 1,760 women, without baseline

NAFLD to explore the association between sleep duration and the

onset of NAFLD. Sleep duration was self-reported and categorized as

≤4, 5–6 or 7–8 h, with a mean follow-up of 3.3 years. During the

follow-up period, 296 new cases of NAFLD were observed, affecting

145 men and 151 women. Among men, a sleep duration of ≤6 h was

significantly associated with a reduced risk of NAFLD [odds ratio

(OR), 0.551; 95% CI, 0.365–0.832; P=0.005], and NAFLD incidence

increased progressively with longer sleep (12.5% in the ≤4 h group

vs. 27.4% in the 7–8 h group; P=0.02) (106). However, no significant

association was observed between sleep duration and NAFLD incidence

in women. The authors suggested that prolonged waking hours in men

may increase basal energy expenditure, counteracting the negative

metabolic effects of sleep deprivation (106). This longitudinal cohort study was

the first to reveal sex-specific associations between sleep

duration and the development of NAFLD. The findings indicate that

short sleep duration may be a protective factor in men, suggesting

that differentiated intervention strategies may be appropriate for

this population. Another study, published the same year, explored

the same topic in a study of 2,172 Japanese individuals, including

731 men and 1,441 women. The study reported an overall NAFLD

prevalence of 29.6%, with rates of 38.0% in men and 25.3% in women

(107). In men, NAFLD prevalence

showed a non-significant decline with longer sleep duration, while

in women, a U-shaped relationship was observed, with prevalence

being highest in those having ≤6 or >8 h sleep and lowest in

those having 6–7 h sleep. Women with ≤6 h of sleep had a

significantly increased risk of NAFLD (age-adjusted OR, 1.44; 95%

CI, 1.06–1.96), which is potentially attributable to a higher body

fat percentage and unhealthy dietary habits such as skipping

breakfast (107). These two

studies emphasize sex-specific differences in sleep duration and

NAFLD within the Japanese population. The divergent findings may

reflect hormonal factors, body fat distribution or behavioral

factors such as dietary patterns. However, these studies have some

limitations, including a reliance on self-reported sleep duration

without objective monitoring of sleep quality or sleep apnea, and a

lack of adjustment for potential confounders such as psychological

health or occupational stress. Despite these limitations, the

evidence clearly implicates sleep deprivation in the development of

NAFLD.

Shift work can disrupt circadian rhythms, lead to

insufficient sleep and contribute to metabolic abnormalities.

Balakrishnan et al (108)

conducted a cross-sectional analysis of National Health and

Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 8,159 employed

participants aged 20–79 years, to examine the potential link

between shift work and NAFLD risk. The overall prevalence of NAFDL

was 15.7%. Although a higher prevalence of NAFLD was observed among

shift workers, multivariate analysis did not find a significant

association between shift work and increased NAFLD risk. Despite

shift work being associated with conditions such as obesity and

diabetes, no significant relationship with NAFLD was observed in

the study, possibly due to the limitations of its cross-sectional

design, which cannot account for long-term exposure (108). Longitudinal studies are necessary

to clarify the effects of shift work duration and sleep quality on

NAFLD development.

ALD

Alcohol can directly influence the expression of

peripheral clock genes (109,110). Huang et al (111) examined circadian clock gene

expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 22

male alcohol-dependent (AD) patients and 12 healthy controls. The

results revealed that the mRNA expression levels of Clock1,

Bmal1, Per1, Per2, Cry1 and Cry2 in the PBMCs of

patients with AD were significantly lower compared with those in

the healthy controls. After 1 week of abstinence, gene expression

showed a limited recovery, but remained significantly lower than

that in the control group. This study was the first to demonstrate

an association between chronic alcohol consumption and circadian

gene dysregulation in humans, suggesting that alcohol may

exacerbate addictive behaviors by interfering with circadian

regulation. However, the small sample size, reliance on a single

time-point measurement (9:00 am), and lack of assessment of

circadian fluctuations limit the ability of the study to fully

capture the dynamics of circadian gene expression. The underlying

mechanisms require further investigation. In another study, Zhou

et al (112) explored how

chronic alcohol consumption disrupts hepatic circadian clock

function and promotes alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis in mice.

The results revealed that that short-term alcohol feeding for 1

week did not significantly alter the expression of core clock

genes, including Per2, Per3 and neuronal PAS domain protein

2 (Npas2), or hepatic lipid accumulation. However, after

long-term alcohol feeding for 4 weeks, Per2 and Per3 expression

significantly increased, while Npas2 expression decreased. These

changes were accompanied by hepatic steatosis and phase shifts in

the circadian rhythms of lipid metabolism genes, including

Cyp7a1 and D-box binding PAR bZIP transcription factor

(Dbp) (112). The mice

with long-term alcohol feeding also exhibited elevated hepatic TG

and CHOL levels, with TG rhythms phase-advanced by 5 h, a 12-h

phase shift in BA synthesis, and a significant reduction in the

NAD/NADH ratio, along with an inverted circadian rhythm. The

authors proposed that chronic alcohol intake disrupts the NAD/NADH

balance and impairs the DNA-binding activity of Clock/Bmal1, which

disturbs circadian gene expression and alters lipid and BA

synthesis pathways, thereby exacerbating alcohol-induced hepatic

inflammation and injury (112).

Although these findings underscore the critical role of the

circadian clock in metabolic homeostasis, as the study was

conducted in a mouse model, further clinical validation is

necessary to establish the relevance of these findings in

humans.

Alcohol directly disrupts the intestinal barrier and

induces gut microbiota dysbiosis, creating a harmful ‘gut-liver

axis’ cycle that accelerates the development of ALD (113). Therefore, targeting intestinal

permeability may represent a novel therapeutic approach for ALD.

Summa et al (114)

demonstrated that ClockΔ19/Δ19 mutant mice

exhibited significantly increased colonic permeability, with

further exacerbation of intestinal leakage following alcohol

feeding. Mice subjected to weekly 12-h light cycle phase shifts

showed increases in colonic permeability comparable to those

observed in alcohol-fed mice. Alcohol-fed

ClockΔ19/Δ19 mutant mice also displayed

significantly elevated serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels and

aggravated hepatic steatosis. Mechanistic investigations revealed

that circadian disruption caused the translocation of occludin

protein from the cell membrane to the cytoplasm, impairing

intestinal barrier integrity and promoting endotoxin translocation.

The resultant endotoxemia activated inflammatory responses, further

aggravating alcoholic fatty liver and hepatocyte injury (114). These findings underscore the

critical role of circadian rhythms in the maintenance of intestinal

barrier function and metabolic health. Targeting the circadian

clock or components regulating the intestinal barrier, such as

occludin, may provide innovative therapeutic strategies for

alcohol-related liver disease.

In a clinical study, Swanson et al (115) explored the impact of circadian

disruption, such as night-work, on alcohol-induced increases in

intestinal permeability and its potential association with ALD. The

study enrolled 22 healthy adults, equally divided into day-shift

(07:00-19:00) and night-shift (19:00-07:00) workers, each with at

least 3 months of consistent work schedules. All participants

underwent a 7-day alcohol intervention, involving the intake of 0.5

g/kg/day red wine, with 24-h circadian assessments conducted before

and after the intervention. Following the intervention, night-shift

workers exhibited significantly increased colonic and whole-gut

permeability, as indicated by elevated 24-h urinary sucrose

excretion, whereas day-shift workers showed no significant changes.

In the night-shift group, melatonin secretion rhythms were delayed

by nearly 2 h and exhibited an inverse correlation with increased

colonic permeability. This group also had higher baseline levels of

the inflammatory markers LPS, LPS-binding protein and IL-6, which

lost circadian rhythmicity following alcohol exposure. Alcohol also

significantly altered the amplitude and phase of core clock genes,

including Clock, Bmal1 and Per1, in PBMCs; however,

differences between the groups were more pronounced in central

circadian markers than in peripheral gene expression (115). These findings provide the first

clinical evidence that circadian misalignment in shift workers

exacerbates alcohol-induced intestinal hyperpermeability, thereby

increasing susceptibility to ALD. They also highlight the vital

role of circadian rhythms in the maintenance of intestinal barrier

integrity and metabolic health, and suggest that targeting the

circadian clock or intestinal barrier components, such as occludin,

may help to mitigate alcohol-related hepatotoxicity. However, this

study is limited by a small sample size, reliance on indirect

inferences from PBMCs rather than intestinal epithelial tissue, and

the lack of circadian-targeted interventions, such as melatonin

supplementation or light therapy. Therefore, further investigation

is necessary to validate these observations.

Research has highlighted the critical roles of

circadian clock genes Rev-erbα and Bmal1 in the

pathogenesis of ALD (116,117).

Yang et al (116)

demonstrated that the nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner

(SHP) mitigates alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis by inhibiting the

Rev-erbα-mediated transcriptional activation of C/EBP homologous

protein (CHOP). In addition, dual deficiency of SHP and Rev-erbα

was found to prevent the development of ethanol-induced fatty

liver. The adenovirus-mediated knockdown of Rev-erbα in

SHP−/− mice alleviated ethanol-induced hepatic

steatosis, and reduced hepatic TG levels, serum ALT/AST levels and

the expression of lipogenic genes, including FASN and

ACC2. This establishes Rev-erbα as a key regulator in the

pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver (116). This study was the first to

provide evidence that SHP and Rev-erbα influence the development of

alcoholic steatosis by modulating diurnal oscillations of CHOP,

revealing novel chronotherapeutic targets for alcohol-related liver

disease.

In study by Zhang et al (117), liver-specific Bmal1 KO

mice developed aggravated steatosis, hepatic injury and

mitochondrial dysfunction following ethanol feeding. By contrast,

Bmal1 overexpression significantly alleviated ethanol-induced

hepatic lipid accumulation and injury. This protective effect

primarily resulted from enhanced carbohydrate response element

binding protein (ChREBP)-mediated de novo lipogenesis via

AKT signaling activation, along with increased PPARα-dependent

fatty acid β-oxidation (117).

Observations in patients with ALD also revealed significantly

reduced hepatic levels of Bmal1, AKT phosphorylation and ChREBP

protein. Animal experiments further demonstrated that treatment

with fenofibrate, a synthetic PPARα ligand, or the overexpression

of AKT or ChREBP partially reversed the metabolic defects and liver

injury in ethanol-fed mice with liver-specific Bmal1 KO

(117). These findings identify

Bmal1 in hepatocytes as a critical protective factor against ALD,

with the Bmal1-AKT-ChREBP axis representing a potential therapeutic

target (117). However, the exact

mechanism by which ethanol disrupts the Bmal1-Clock protein complex

remains unclear, warranting further investigation.

LF

LF is a precursor to cirrhosis, and patients with

cirrhosis often present with hepatic portal hypertension and

disturbances in circadian rhythms, including delayed sleep cycles,

altered melatonin and cortisol levels, and lethargy (118). However, the physiological

mechanisms underlying these phenomena remain unclear. Montagnese

et al (119) analyzed 87

patients with liver cirrhosis and found that 50–65% of them

experienced difficulty falling asleep or woke up during the night,

which was not directly associated with hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

The patients also exhibited a delayed sleep phase syndrome

(DSPS)-like pattern, characterized by staying up late and waking up

late, with a delay of 2–3 h in the peak secretion of melatonin.

Daytime melatonin levels were increased, nighttime clearance was

delayed, and the urinary excretion of 6-sulfamoxy melatonin was

reduced (120). Daytime

sleepiness correlated significantly with HE severity and blood

ammonia levels, with a negative predictive value of 92%. Abnormal

SCN function in the patients led to delayed synchronization of

melatonin and cortisol rhythms and a weakened response of melatonin

to light exposure, suggesting SCN dysfunction (120,121). The authors proposed that reduced

SCN photosensitivity involves disruption of the Clock/Bmal1 and

Per/Cry protein feedback loops, causing delayed melatonin rhythms

and a DSPS-like sleep phase. In addition, in a rat model of liver

cirrhosis with portal shunt, delayed activity rhythms, decreased

ammonia-induced deep sleep, and decreased liver SIRT1/PARP-1

activity were observed compared with those in controls (122–124). In the liver, an imbalance in

SIRT1 and PARP-1 activities leads to the asynchronous expression of

peripheral clock genes contributing to glucose and protein

metabolism disorders (124).

These findings indicate that both the peripheral and central

circadian clocks were disrupted, affecting the liver and SCN,

respectively. Notably, chronic light exposure accelerated liver

tumor growth in cirrhotic mice, indicating a self-reinforcing cycle

of circadian rhythm disruption and liver disease progression

(125). Subjecting cirrhotic mice

to chronic light exposure further accelerated liver tumor growth,

suggesting that circadian rhythm disruption may exacerbate disease

progression. These reports introduced a dual pathway model of

‘central-peripheral circadian clock disconnection’ and

‘metabolism-neurotransmitter imbalance’, supported by animal data

revealing a downstream molecular cascade effect. However, further

clinical translational research is required to validate these

findings.

Studies using animal models have demonstrated

disruptions in circadian clock gene regulation during LF (92,126). For example, in a carbon

tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced LF mouse model, a complete

loss of rhythmicity in the Cry2 gene was observed, along

with significantly reduced daytime expression. In addition, Clock

and Per1 expression exhibited an elevated mesor with reduced

amplitude, Bmal1 and Per1 expression levels were markedly weakened

in amplitude, and the peaks of Clock, Per1 and Cry1 expression were

delayed. Per2 rhythmicity remained largely unaffected, suggesting a

potential protective role against LF (126). Furthermore, the circadian

oscillations of CCGs involved in hepatic metabolism, such as

PPARα and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase, were abolished,

with a marked reduction in expression levels. These findings imply

that LF disrupts the transcriptional-translational feedback loop of

Clock/Bmal1 and Per/Cry proteins (126). The loss of Cry2 rhythmicity may

exacerbate lipid metabolic disorders via downstream targets such as

PPARα. This study provided the first evidence that LF directly

causes circadian clock dysregulation in peripheral tissues,

particularly the liver, offering a molecular explanation for the

circadian rhythm disturbances observed in patients with cirrhosis.

However, as the data were validated only at the mRNA level, further

studies examining protein expression are warranted (126).

In a separate study, Chen et al (92) demonstrated that in a

CCl4-induced LF model, Per2 KO mice exhibited

more severe collagen deposition and hepatic stellate cell (HSC)

activation than WT mice. In addition, transfection of Per2

cDNA into the HSC-T6 cell line significantly increased HSC

apoptosis, accompanied by upregulation of the expression of

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-receptor 2 (TRAIL-R2), also

known as death receptor 5. Further analyses revealed that Per2

induces HSC apoptosis by upregulating CHOP transcription factors,

thereby promoting TRAIL-R2 expression (92). This study was the first to

demonstrate that Per2 protects the liver from chronic damage

through a dual mechanism, involving the inhibition of HSC

activation and promotion of apoptosis, highlighting Per2 and

TRAIL-R2 pathways as potential anti-fibrotic targets.

In a bile duct ligation (BDL)-induced mouse model,

Per2 KO (Per2−/−) mice exhibited more

severe cholestatic liver injury than WT mice, including larger bile

infarcts and increased hepatocyte necrosis (127). Serum and liver BA levels were

significantly elevated, accompanied by loss of circadian rhythm in

the expression of BA synthesis enzymes, such as CYP7A1, and

transporter proteins, including sodium taurocholate co-transporting

polypeptide (NTCP) and bile salt export pump. Furthermore, compared

with WT mice, the Per2−/− mice exhibited

aggravated LF, with increased collagen deposition, increased

activation of HSCs as indicated by a-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA),

and elevated mRNA levels of the pro-fibrotic factors transforming

growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), TNF-α and collagen type I α1 (Col1α1) in

liver tissue (127).

Mechanistically, Per2 deficiency disrupts the circadian rhythm of

the rate-limiting BA synthesis enzyme CYP7A1, reducing its

efficiency and decreasing the expression of the BA uptake

transporter NTCP. This leads to hepatic BA accumulation, elevated

serum BA levels, and exacerbated BA toxicity. In parallel, Per2

deficiency promotes excessive HSC activation, further driving

collagen deposition and fibrosis (127). Similar findings were reported by

Chen et al (128),

confirming that Per2 plays a protective role in cholestatic liver

injury by maintaining the circadian rhythm of BA metabolism and HSC

function (92).

HSC activation plays a pivotal role in LF, with

evidence suggesting that circadian clock genes directly regulate

this process (92,128,129). Rev-erbα protein levels have been

observed to be significantly elevated in both BDL- and

CCl4-induced LF models, as well as in human cirrhotic

tissues, despite no significant changes in expression at the mRNA

level, indicating post-translational regulation (130). Notably, TGF-β induction increases

the cytoplasmic accumulation of Rev-erbα in HSCs, displaying a

distribution pattern similar to that of myosin, while the synthetic

Rev-erb ligand SR6452 reduces the cytoplasmic expression of

Rev-erbα. They developed a Rev-erbα truncation mutant in which the

N-terminus of the protein encompassing the DNA-binding domain

(which encodes a nuclear localization signal) was deleted.

Experiments using a Rev-erbα mutant demonstrated that

cytoplasmic Rev-erbα enhances cellular contractility in NIH3T3

mouse fibroblasts and promotes fibrotic progression (130). Notably, SR6452 potentiated the

ability of nuclear Rev-erbα to repress the transcription of its

target gene plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, thereby reducing

collagen deposition. Conversely, in the cytoplasm, SR6452

diminished Rev-erbα protein expression, thereby suppressing HSC

activation and collagen accumulation (130). These findings highlight a dual

role for Rev-erbα in HSCs, with both nuclear transcriptional

repression and cytoplasmic pro-fibrotic activity, modulated by

SR6452 (130). This study

provided the first evidence that Rev-erbα regulates HSC phenotypic

switching through differential nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution,

positioning Rev-erbα ligands such as SR6452 as potential targeted

therapies for LF and portal hypertension. A subsequent study

revealed that Bmal1 expression was significantly downregulated and

glycolytic activity increased in CCl4-induced mouse LF

models, and in primary HSCs and LX2 cells activated by TGF-β1

(131). The overexpression of

Bmal1 inhibited the glycolysis, proliferation and phenotypic

transformation of activated HSCs, including the downregulation of

α-SMA and COL1α1 expression. The underlying molecular mechanism was

shown to involve Bmal1-induced attenuation of HSC activation via

the promotion of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) expression and

α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) generation, and the subsequent inhibition of

key glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase 2 and pyruvate kinase

M2 (131). This study was the

first to demonstrate that Bmal1 regulates HSC glycolysis via the

IDH1/α-KG axis, and to propose a regulatory network linking the

biological clock, metabolism and fibrosis. These findings suggest

that Bmal1 or IDH1 agonists, such as α-KG supplementation, may be

promising therapeutic strategies for LF, although further research

is necessary to validate these findings.

In a recent study, Crouchet et al (20) found that in the livers of healthy

mice, the circadian rhythm plays a time-gating role by regulating

the expression of TGF-β target genes, including Smad3, Smad7

and TGF-βR1, and inhibiting persistent pro-fibrotic signals.

Analysis of a metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis

mouse model revealed that circadian clock disorders, characterized

by reduced expression of Rev-erbα, Per1, Per2 and Cry2, resulted in

a loss of control over TGF-β signaling, thereby promoting HSC

activation and collagen deposition. In addition, the treatment of

primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) with FFAs disrupted the expression

of circadian clock genes, such as Bmal1 and Rev-erbα,

and upregulated the expression of TGF-β target genes (20). Furthermore, reduced protein levels

of Rev-erbα, Per1 and Per2 were observed in the livers of patients

with cirrhosis, and these reductions were negatively correlated

with the degree of fibrosis (20).

These findings suggest that dysregulation of circadian clock genes

directly contributes to sustained activation of the TGF-β signaling

pathway and subsequent fibrosis. Subsequently, the roles of Bmal1

and Rev-erbα were examined using Bmal1 KO mice and

hepatocyte-specific Bmal1 KO (Bmal1hep-/−)

mice. In the livers of Bmal1 KO mice, the rhythmic

expression of TGF-β target genes was disrupted, confirming Bmal1 as

a key regulator of TGF-β signaling (20). In Bmal1hep-/−

mice, the circadian expression of TGF-β target genes was abolished,

and Bmal1/Clock complex binding to the promoter regions of TGF-β

target genes was significantly reduced. Rhythmic Bmal1/Clock

binding to the promoter regions of TGF-β target genes, such as

Smad7 and TGF-βR1, was detected in the livers of

healthy mice but not those of Bmal1hep-/− mice

(20). Furthermore, in normal

HSCs, Bmal1 and its downstream genes such as Per1/2 and

Rev-erbα, regulate the rhythmic expression of

fibrosis-related genes. However, in a choline-deficient amino

acid-defined high-fat diet (CDA-HFD) model of fibrosis in mice, the

rhythmic expression of Bmal1 in HSCs was lost, pro-fibrotic genes,

including actin a 2 (ACTA2) and TGF-βR1, were highly

expressed and the expression of anti-fibrotic genes, including

Smad7 and matrix metalloproteinase 9, was decreased.

Single-cell RNA sequencing confirmed that Bmal1 KO disrupts

the rhythmic dysregulation of fibrosis-related pathways, including

the TGF-β and extracellular matrix pathways in HSCs (20). These findings indicate that reduced

Bmal1 expression promotes HSC activation by modulating TGF-β

signaling.

The KO of Rev-erbα from LX2 HSCs upregulates the

expression of pro-fibrotic genes such as ACTA2 and

Col1α1 (20), while the

Rev-erbα agonist SR9009 reduces TGF-β-induced Smad2/3

phosphorylation and the expression of fibrosis marker proteins.

Furthermore, in PHHs, SR9009 reverses FFA-induced lipid

accumulation and the upregulation of TGF-β target genes (20). These findings suggest that Rev-erbα

maintains liver homeostasis by rhythmically inhibiting TGF-β

signaling, and its downregulation is a key driver of fibrosis

progression. The pharmacological targeting of Rev-erbα using SR9009

induced a significant reduction in collagen deposition,

hydroxyproline content and the expression of fibrosis-related genes

Col1α1 and TGF-β1 in the CDA-HFD mouse model. SR9009

also decreased α-SMA expression and collagen deposition in human

liver chimeric model mice, and significantly reduced the expression

of fibrosis markers in hepatic spheroids from fibrotic patients

(20). These results suggest that

targeting Rev-erbα can restore circadian clock function,

inhibit fibrosis, and provide a novel strategy for clinical

anti-fibrotic therapy.

HCC

The circadian mechanism strictly regulates the cell

cycle, cell proliferation, and the expression of tumor suppressor

genes and oncogenes (132,133).

The incidence of spontaneous tumors and radiation-induced HCC is

significantly increased in Per2−/−,

Bmal1±, Cry1−/− and

Cry2−/− mice (134,135). Diethylnitrosamine (DEN) disrupts

circadian rest-activity and body temperature rhythms (125,136,137), and reduces the oscillation

amplitude of Per1 in DEN-induced HCC mouse models (138). In such models, mice subjected to

conditions simulating chronic jet lag develop more tumors compared

with those under normal circadian conditions (125). DEN exposure upregulates the

expression of core clock genes, including Bmal1, Clock and

Npas2, while downregulating negative feedback genes,

including Per1-3 and Cry1, in mouse livers; melatonin

treatment reverses these effects (136). In vitro, a combination of

melatonin and SR9009 synergistically inhibits the proliferation of

Hep3B HCC cells, while Bmal1 knockdown attenuates the pro-apoptotic

and anti-proliferative effects of melatonin, indicating that Bmal1

is a key mediator of anticancer effects (136). These findings reveal a molecular

mechanism by which melatonin suppresses HCC progression through

circadian clock regulation. However, the study was limited to

DEN-induced mouse HCC models and Hep3B cells, without validation in

other models or clinical samples, and the downstream signaling

pathways remain to be clarified.

Disrupted circadian rhythms are associated with

hepatic metastasis (139).

Huisman et al (139)

compared the 24-h expression patterns of core clock genes in the

hepatic and renal tissues of mice with C26 colorectal cancer liver

metastases. In tumor tissues, the rhythmic expression of core clock

genes Bmal1, Rev-erbα and Per1/2, and CCGs including

Dbp, Wee1 and p21, was abolished, indicating severe

circadian dysfunction (139). In

peritumoral hepatic tissues, the core clock genes exhibited phase

advances relative to those in healthy controls, while renal tissues

displayed phase delays, suggesting that tumor-derived signals

disrupt clocks in distal organs (139). These findings highlight the phase

interference caused by colorectal cancer liver metastases at the

local and systemic levels, indicating that interactions occur

between the tumor microenvironment and host rhythms. However, the

molecular mechanisms mediating these shifts require further

exploration.

NAFLD can progress to NASH, which is linked to LF,

liver failure and HCC (140,141). Padilla et al (142) used humanized mouse models to

investigate the mechanisms by which disrupted circadian rhythms

contribute to NAFLD-associated HCC development. The study revealed

that core clock genes exhibit robust circadian rhythmicity in

healthy human and murine livers. However, during NAFLD and NASH

progression, this rhythmic regulation diminishes, with dampened

oscillation amplitudes and phase disturbances, and circadian gene

rhythmicity is nearly abolished in HCC. These changes coincide with

the upregulation of proto-oncogenes, including c-Myc and

c-Fos, and the suppression of tumor suppressor genes,

including fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase and nuclear receptor

subfamily 1 group H member 4 (142). In addition, a chronic jet lag

model in humanized mice accelerated the progression from NAFLD to

NASH to HCC (142).

Transcriptomic analysis showed that circadian disruption

dysregulated thousands of genes, leading to impaired BA and fatty

acid metabolism pathways, activation of NF-κB and TNF-α

inflammatory signaling, suppression of oxidative phosphorylation,

induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and impaired DNA

repair (142). These findings

delineate how circadian dysregulation drives NAFLD-associated

hepatocarcinogenesis by a metabolism-inflammation-cancer axis,

emphasizing the importance of circadian homeostasis in HCC

prevention. However, the molecular mechanisms require further

investigation.

Human studies have established a strong association

between disrupted circadian clock gene expression rhythms and the

development and progression of HCC (93,143). A comparative analysis of 46

paired HCC and adjacent non-tumorous tissues found significantly

reduced mRNA and protein expression levels of Per1, Per2, Per3,

Cry2 and Timeless (TIM) in HCC tissues (93). This circadian gene dysregulation

was associated with the aberrant expression of cell cycle-related

genes, suggesting uncontrolled tumor cell proliferation (93). However, the study was limited by

its small sample size, incomplete coverage of core clock genes, and

reliance on correlative observations that require further

mechanistic validation. In another study, involving 337 patients

with HCC undergoing transarterial chemoembolization, a significant

association was observed between the rs2640908 Per3

single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and overall survival; this

functional polymorphism correlated with reduced survival (143). A retrospective analysis using

data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and International Cancer Genome

Consortium demonstrated that high TIM expression or low Cry2, Per1

and RORα expression significantly predicted poor HCC prognosis

(144). Furthermore, Cry2, Per1,

and Rorα expression inversely correlated with B-cell and regulatory

T-cell infiltration, while TIM showed a positive correlation,

suggesting that these proteins contribute to the regulation of

tumor immune evasion (144). This

study highlights potential immune mechanisms that warrant

experimental validation. Overall, human clinical data on circadian

rhythms in HCC are limited, particularly regarding the practical

efficacy of chronotherapy in HCC management. However, these

findings support circadian clock genes as potential diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets for HCC.

Treatment of liver diseases based on the

biological clock

Drugs and active ingredients

A number of compounds have been shown to protect

against liver diseases by modulating circadian clock pathways. For

example, Melatonin treatment significantly ameliorates the

dysregulation of hepatic clock gene oscillations induced by

high-fat high-fructose diet and jet lag in mice, restoring the

rhythmic expression of Bmal1 and Clock while partially correcting

oscillations in the Nrf2-HO-1 pathway. This leads to reduced

hepatic lipid accumulation, decreased serum AST/ALT levels, and

improved expression of lipid metabolism-related genes (CPT-1, PPARα

and SREBP-1c) (145). In the LX-2

human HSC line, melatonin suppressed the expression of fibrosis

markers through the melatonin receptor 2-mediated upregulation of

Bmal1 and antioxidant enzymes (146), suggesting a molecular pathway for

the protective effects of melatonin against LF.

Ursolic acid (UA) has been shown to alleviate

hepatic steatosis, fibrosis and insulin resistance in HFD-induced

obese mice by regulating circadian gene expression (147,148). Treatment with UA reduced the

expression of Clock and Bmal1 in liver tissue, while

increasing that of Per1, Per2 and Per3 compared with

the respective levels in untreated HFD-fed mice. UA also promoted

the expression of genes involved in lipid and BA metabolism,

including nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, forkhead box O3

and insulin-induced gene 1 (148).

A vitamin D-deficient diet has been shown to

disrupt circadian synchronization in the liver, while quercetin

supplementation alleviates this disorder. Specifically, a study

revealed that Bmal1 expression was upregulated while Clock and Cry1

expression was downregulated in mice fed a vitamin D-deficient

diet. However, following quercetin supplementation, Clock protein

expression increased significantly, while Bmal1 mRNA

expression decreased (149).

Nobiletin, a polymethoxyflavone abundant in citrus

fruits, enhances circadian rhythms and ameliorates diet-induced

hepatic steatosis (150–152). In models of ALD, nobiletin

activated AKT, increased the expression of ChREBP, ACC1 and FASN,

and decreased SREBP-1 levels and ACC1 phosphorylation in a

Bmal1-dependent manner, thereby alleviating liver injury (153).

Similarly, when the effects of sulforaphane were

examined in HFD-fed mice with a disrupted circadian rhythm,

significant enhancements in the abundance of beneficial gut flora,

including Lachnospiraceae, Lactobacillus and

Alistipes were observed. This was accompanied by a reduction

in the expression of Rev-erbα, Per1 and Bmal1 proteins in the

liver, and increased Clock expression in the hypothalamus (154).

Time-restricted feeding

Time-restricted feeding, which limits nutrient

intake to a defined time window, significantly impacts biological,

physiological, biochemical and behavioral processes. This regimen

not only resets the liver clock but also dissociates it from the

central circadian oscillator (16,155,156). In mice, restricted feeding

prevented HFD-induced weight gain, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia

and insulin resistance. Long-term food restriction also reduced the

expression of inflammatory cytokines in the liver, small intestine

and white adipose tissue (156–158). By aligning the timing of nutrient

intake with circadian timing, time-restricted feeding improves

weight loss and metabolic homeostasis, supporting its integration

with standard treatment strategies for liver diseases.

Phototherapy

Morning light therapy effectively advances

circadian rhythms and sleep phases, with short blue-light pulses in

the morning improving sleep integrity and quality. Intermittent

light exposure appears to be more effective in altering circadian

rhythms than continuous light (43). Therefore, phototherapy may offer

potential benefits for liver diseases associated with circadian

rhythm disruptions, although further studies are necessary to

evaluate this.

Chronopharmacology

Temporal pharmacology highlights that numerous

pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters follow circadian

rhythms, meaning that the efficacy and safety of drugs fluctuate

with the time of administration. The circadian clock regulates

every stage of hepatic drug metabolism, including absorption,

distribution, transformation and elimination (159). During absorption, the liver takes

up lipophilic drugs more rapidly in the morning than at night. In

the distribution phase, the expression of several transporters,

including organic cationic transporter 1 and organic anion

transporting polypeptides 1 and 1A4, exhibits circadian variation.

In metabolism, xenobiotic metabolism is divided into three phases,

with the expression of relevant genes following a biological rhythm

in the mouse liver (160).

Furthermore, circadian-regulated transcription factors, including

RORα/γ, DBP, hepatic leukemic factor and thyrotroph embryonic

factor, control the expression of liver metabolic genes that encode

enzymes involved in drug metabolism and elimination (159). Notably, the timing of

administration is a crucial factor influencing drug efficacy. For

example, circadian disruption induced by HFD feeding can be

corrected with appropriately timed drug interventions (160). Due to strict timing requirements,

circadian-based drug administration is often impractical, reducing

patient compliance. As a result, most drugs are not administered

according to circadian rhythms. However, given accumulating

evidence linking circadian rhythm disorders with metabolic

diseases, the role of time-based therapy in disease prevention and

treatment merits more attention.

Conclusions and future prospects

Circadian clock research remains a prominent

frontier in the life sciences, highlighted by the 2017 Nobel Prize

in Physiology or Medicine being awarded for the discovery of its

molecular mechanisms. As a key peripheral clock, the liver clock

plays a pivotal role in the regulation of energy balance and

metabolic homeostasis, coordinating the daily rhythms of processes

such as glucose and lipid metabolism. Disruptions in circadian

clock genes have been observed in several chronic liver diseases,

and circadian rhythm disorders promote the onset and progression of

these conditions. For liver diseases associated with circadian

disturbances, promising therapeutic approaches include natural

drugs, time-restricted feeding, chronotherapy, phototherapy and the

development of clock-targeting drugs.

Despite progress, research on the relationship

between circadian rhythms and liver diseases remains limited.

Mechanistic understanding is insufficient, with most studies

relying on animal models, such as Bmal1 KO mice, and lacking

a comprehensive dissection of the spatiotemporal regulatory

networks governing human circadian genes, including the

Bmal1-PPARγ-CD36 axis. Critical molecular events, such as the

nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Rev-erbα, are largely described

without dynamic single-cell tracking. Multi-organ interactions,

particularly the cooperation between hepatic rhythms, gut

microbiota and the central clock, remain underexplored.

Methodological shortcomings also persist: Human studies such as the

NHANES, predominantly use a cross-sectional design, which cannot

establish causality, while animal models fail to replicate the

long-term effects of human societal behaviors, such as shift work.

Circadian monitoring technologies remain underdeveloped; static

sampling methods, such as PBMC analysis, cannot capture dynamic

oscillations of liver clock genes in real time. Clinical

translation faces major barriers, as current interventions,

including Rev-erbα targeting with SR9009 and time-restricted

feeding. Time-restricted feeding has only been validated in small

cohorts and lacks multi-center randomized controlled trial (RCT)

evidence (21). In addition,

inter-individual variations in circadian disruption have not been

adequately addressed.

To address current limitations, several strategies

are suggested. First, mechanistic investigations should be

deepened: Single-cell sequencing technologies could be used to map

circadian-specific regulatory networks within hepatocytes and HSCs.

In addition, humanized mouse models could be established to

simulate circadian disruption-related diseases in humans, with the

synchronized acquisition of cross-organ parameters being achieved

by the integration of functional magnetic resonance imaging for SCN

neural activity, nanopore real-time sequencing for the 16S rRNA

profiling of gut microbiota, and hepatic microdialysis for

single-cell metabolic flux analysis. Second, methodological

improvements are essential. Since cross-sectional studies, such as

the NHANES, cannot establish causality, humanized mouse models

mimicking human shift-work behaviors may be constructed. In

addition, technological innovation could focus on the development

of liver-specific biosensors paired with wearable devices for

continuous circadian parameter monitoring. These wearables can be

integrated with artificial intelligence predictive algorithms, such

as long short-term memory time-series models, to generate

personalized circadian profiles. Finally, clinical translation

should be accelerated: Multi-center RCTs are needed to validate the

efficacy of chronotherapeutic interventions, such as timed

melatonin administration, in patients with cirrhosis. In addition,

circadian gene variants, such as the Per3 SNP rs2640908,

along with broader expression signatures, should be developed as

early diagnostic biomarkers for liver diseases.

To enhance clinical translation, circadian

assessments may be incorporated into routine liver disease

screening protocols, including genotyping for Per3 variants

alongside salivary melatonin rhythm profiling. Existing evidence

should be integrated into liver disease management guidelines,