Introduction

R-loops are triple-stranded nucleic acid structures

comprising an RNA:DNA hybrid and displaced single-stranded DNA,

typically forming co-transcriptionally when nascent RNA reanneals

to its template DNA strand (1).

Once considered by-products of transcription, R-loops have been

recognized as important regulators of gene expression, DNA

replication and genome maintenance (1). Under physiological conditions,

controlled R-loop formation plays a role in normal transcriptional

termination, RNA processing, epigenetic regulation and

mitochondrial DNA replication (1,2).

However, unscheduled or persistent R-loops can become pathological

and pose a threat to genomic integrity (1). Excess R-loops can stall replication

forks, induce DNA breaks and promote mutagenesis, thereby

contributing to genomic instability, which is a well-known hallmark

of cancer (1–3). Indeed, aberrant accumulation of

R-loops has been observed in breast cancer, colorectal cancer and

leukemia and has been linked to dysregulated proliferation and

oncogene activation (2,4,5).

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common

primary liver cancer, is a disease characterized by pronounced

genomic instability (1,6). HCC typically arises in cases of

chronic liver injury, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HCV

infection, alcohol abuse or fatty liver disease, and is

characterized by ongoing DNA damage and chromosomal aberrations

(1,6). Such chronic stress may predispose the

liver cells to aberrant R-loop accumulation. Recent evidence

suggests that R-loops play a role in HCC pathophysiology; improper

regulation of R-loop homeostasis can drive DNA breakage and

replication stress, fueling the genomic instability that propels

hepatocarcinogenesis (1,6).

Furthermore, HCC cells may co-opt mechanisms to

tolerate or exploit R-loops. HCCs generally have defence mechanisms

to minimize R-loop-induced damage (6) and aggressive tumors often upregulate

R-loop-resolving factors to maintain survival despite high

transcriptional output (2). HCC

tumors frequently exhibit widespread transcriptional dysregulation

due to inflammation and oncogene activation, which can alter

signaling pathways, epigenetic marks and transcription factor

activity, leading to aberrant gene expression, replication stress

and increased R-loop formation. In addition, HBV infection, a major

etiological factor of HCC, is associated with changes in the

expression of R-loop regulatory genes (7). An integrative single-cell study found

that HCC cells from HBV-infected livers tend to have higher ‘R-loop

scores’ linking viral oncogenesis with R-loop dysregulation

(1).

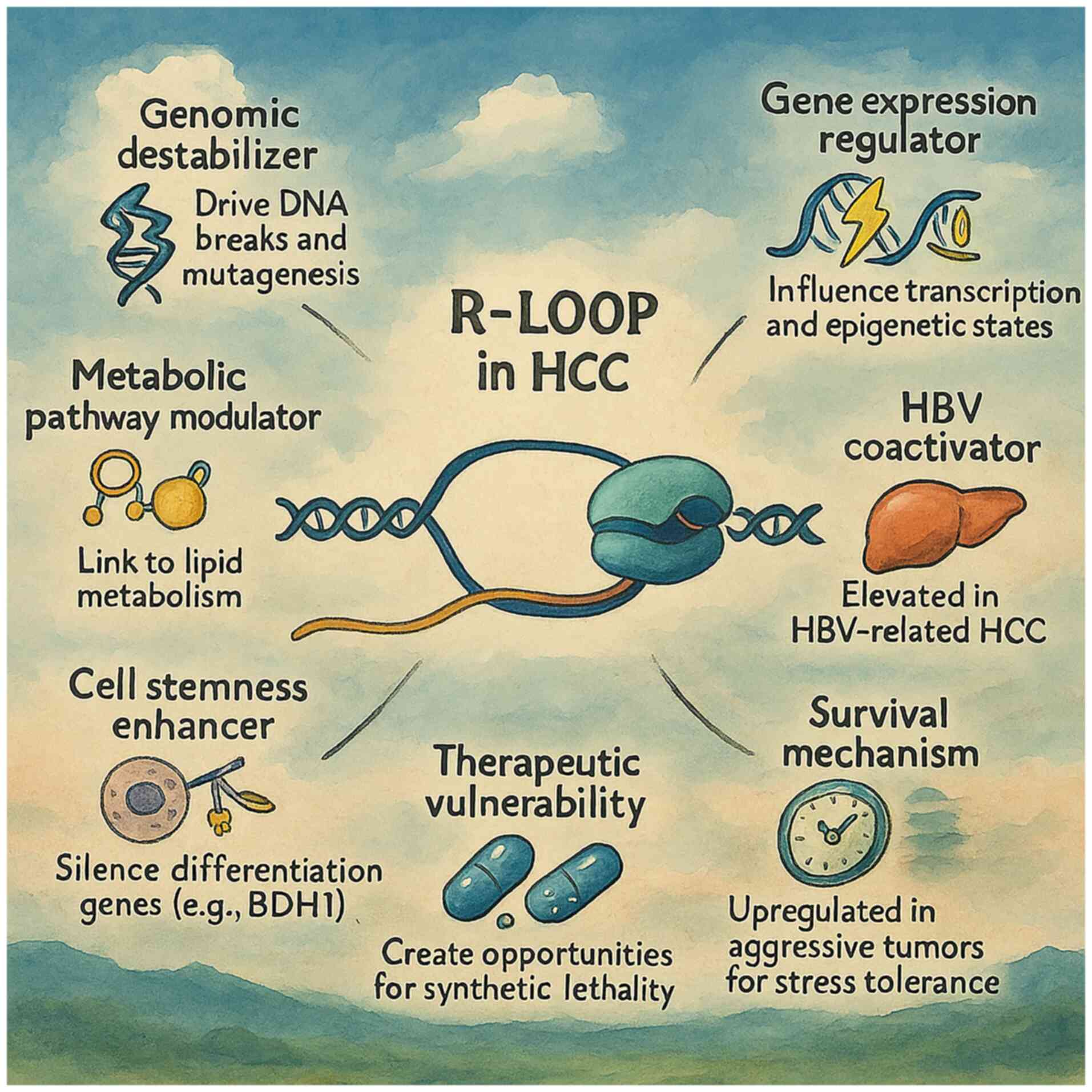

In summary, R-loops represent a notable interface

between transcriptional regulation and genomic stability in cancer

cells. In HCC, a cancer characterized by extensive genomic

instability and complex molecular drivers, understanding R-loop

biology is particularly relevant. The present review provided an

overview of R-loop formation and functions and delves into their

mechanistic impact on transcriptional regulation and genome

stability in HCC. The key findings on the role of the R-loop in HCC

are summarized in Table I

(1,2,6,8,9).

Selected R-loop-associated genes and their functions in HCC are

presented in Table II (1,2,10–12).

The R-loop-related signaling pathways in HCC are shown in Table III (1,8,9,13).

Therapeutic strategies targeting R-loops in HCC are presented in

Table IV (1,11,12,14).

The present review also discussed how HCC cells manage or mismanage

R-loops and how this knowledge has contributed to novel therapeutic

strategies.

| Table I.Key findings on the roles of R-loops

in HCC. |

Table I.

Key findings on the roles of R-loops

in HCC.

| Key finding | Description and

significance | (Refs.) |

|---|

| R-loops contribute

to genomic instability in HCC | Persistent R-loops

induce DNA breaks and replication stress, fueling HCC genomic

instability | (1,6) |

| HCC cells modulate

R-loop levels for survival | Cancer cells

upregulate defense mechanisms to limit R-loop-associated

damage | (2,6) |

| High R-loops linked

to HBV-related HCC | HBV-infected HCCs

show elevated R-loop regulator-gene expression and higher R-loop

scores | (1) |

| R-loops impact HCC

tumor microenvironment | R-loops activate

innate immune pathways, influencing tumor-immune interactions | (1) |

| R-loop

dysregulation alters metabolism in HCC | Aberrant R-loops

are linked to metabolic reprogramming affecting tumor

progression | (1) |

| R-loop-associated

factors affect chemosensitivity | THO complex 1

knockdown increases R-loops and DNA damage, sensitizing cells to

cisplatin | (8) |

| Oncogenic drivers

exploit R-loops |

Metastasis-associated protein 2 enhances

R-loop formation to silence differentiation genes such as

β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1 | (9) |

| Table II.Selected R-loop-associated genes and

proteins and their roles in HCC. |

Table II.

Selected R-loop-associated genes and

proteins and their roles in HCC.

| Gene/factor | Role in R-loop

regulation | Relevance in

HCC | (Refs.) |

|---|

| RNASEH1 | Degrades RNA in

hybrids | RNASEH1-antisense 1

long non-coding RNA is upregulated in advanced HCC | (2,10) |

| RNASEH2

(A/B/C) | Removes RNA from

hybrids | RNASEH2 deficiency

creates synthetic lethality when combined with ATR inhibition | (11) |

| Senataxin | Unwinds R-loops

during transcription | Important for

resolving R-loops at highly transcribed HCC genes | (12) |

| Fanconi anemia

group G protein (Fanconi anemia complex) | Binds and resolves

R-loops at forks | Part of the 8-gene

prognostic signature; affects HCC outcomes | (1,2) |

| Breast cancer

susceptibility gene 1/2 | Recruits factors to

suppress R-loops | Suppresses

telomeric R-loops that cause DNA damage | (1,2) |

| TOP1 | Prevents excessive

R-loop formation | TOP1 inhibitors

induce DNA damage partly via R-loop accumulation | (12) |

| ATR/checkpoint

kinase 1 pathway | Responds to

R-loop-stalled forks | High R-loop HCCs

show ATR dependency; this shows potential for ATR inhibition in

therapeutics | (2,12) |

|

Metastasis-associated protein 2/histone

deacetylase 2 (nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase) | Promotes R-loops at

target genes | Enhances stemness

via R-loop-mediated silencing of differentiation genes | (1) |

| Table III.R-loop-related signaling pathways in

HCC. |

Table III.

R-loop-related signaling pathways in

HCC.

| Pathway |

Trigger/context | Function in

HCC | (Refs.) |

|---|

| DNA damage response

(ATR/ATM-checkpoint kinase 1) |

Transcription-replication conflicts cause

R-loop accumulation, stalling replication forks and causing DNA

double-strand breaks. For example, the loss of the RNA export

factor THO complex 1 in HCC cells increases R-loops and activates

DNA damage signaling | Activates ATR/ATM

and p53 pathways, leading to genomic instability or growth arrest.

In HCC models, R-loop-induced DNA damage reduces tumor cell

proliferation and sensitizes cells to chemotherapy | (8) |

| Innate immune

(cGAS-STING) pathway | Unresolved nuclear

R-loops can be processed into cytosolic RNA:DNA hybrids, such as in

breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 or Senataxin-deficient

contexts. These hybrids and R-loop-derived DNA fragments are sensed

by cGAS and other pattern recognition receptors | Triggers

STING-interferon regulatory factor 3 signaling and inflammatory

cytokine production. In HCC, excessive R-loops aberrantly activate

innate immunity, which can induce tumor cell apoptosis and reshape

the tumor microenvironment | (13) |

| Metabolic

reprogramming (lipid metabolism) | Upregulation of

certain R-loop regulator genes, such as CLTC, in HCC promotes

persistent R-loop formation at metabolic gene loci, for example at

fatty acid synthase regulators | Enhances lipid

biosynthesis and storage to fuel tumor growth. High R-loop levels

in HCC cells are linked to increased fatty acid metabolism and a

more aggressive tumor phenotype. For instance, CLTC-driven R-loops

upregulate lipogenic pathways, supporting rapid proliferation | (1) |

| Epigenetic

regulation (histone modification) | R-loops can be

exploited by chromatin-modifying complexes to silence genes. In

HCC, the chromatin remodeler metastasis-associated protein 2,

acting with histone deacetylase 2/chromodomain-helicase-DNA-

binding protein 4, induces R-loop formation at the BDH1

locus, which is a metabolic gene | Transcriptional

repression of BDH1 leads to altered β-hydroxybutyrate levels

and increased histone β-hydroxybutyrylation, an epigenetic mark

that promotes cancer stem cell traits. This R-loop-dependent

epigenetic silencing enhances HCC stemness and tumor

propagation | (9) |

| Table IV.Therapeutic strategies impacting

R-loops in HCC. |

Table IV.

Therapeutic strategies impacting

R-loops in HCC.

| Therapeutic

agent/class | Mechanism (R-loop

context) | Potential

application in HCC | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Topoisomerase I

inhibitors | Increase R-loop

formation and associated DNA breaks | Target HCCs with

high transcriptional output; combine with DNA damage response

inhibitors | (12) |

| ATR inhibitors | Block responses to

R-loop-induced fork collapses | Target HCCs with

R-loop resolution defects or high stress | (11,14) |

| Poly(ADP-ribose)

polymerase inhibitors | Block repair of

R-loop-induced DNA breaks | Effective in HCCs

with homologous recombination deficiencies or R-loop-mediated

breast cancer susceptibility gene sequestration | (12) |

| Splicing

modulators | Induce R-loop

overload via unspliced transcripts | Create synthetic

lethality when combined with ATR inhibitors | (14) |

| Guanine-quadruplex

stabilizers | Prevent R-loop

resolution by locking Guanine-quadruplex structures | Target R-loop-prone

regions in HCC, such as recombinant DNA and telomeres | (12) |

| Histone deacetylase

inhibitors | Alter chromatin

states affecting R-loop dynamics | Reverses

metastasis-associated protein 2-induced R-loop silencing of

differentiation genes | (1,12) |

Mechanisms of R-loop formation and function

in HCC

R-loop formation and homeostasis

Formation

R-loops commonly form during transcription when

nascent RNA threads back and hybridizes with the template DNA

strand, displacing the non-template strand (1). Certain DNA sequences and contexts

promote R-loop formation; for example, GC-rich regions, especially

those capable of forming G-quadruplexes, and repetitive sequences

increase the stability of RNA:DNA hybrids. Negative supercoiling

behind a moving RNA polymerase can also facilitate re-annealing of

RNA strands to DNA (12). By

contrast, positive supercoiling before the polymerase can impede

hybrid formation. This topological balance is managed by

topoisomerases (TOPs) such as TOP1, TOP2 and TOP3B, which relax the

supercoils and prevent excessive R-loop formation (12).

Regulation and resolution

The cell maintains R-loop homeostasis through

dedicated enzymes that remove R-loops once formed. Most of these

are ribonuclease H (RNASEH)1 and 2, which specifically recognize

RNA:DNA hybrids and cleave RNA strands (2). RNASEH1 is active throughout the cell

cycle and serves as the first line of defence against R-loops,

degrading RNA components and dismantling the hybrid (15). RNASEH2 operates especially during

the S/G2 phases, not only to resolve R-loops but also to

excise ribonucleotides embedded in DNA (16).

Along with RNASEH, several DNA and RNA helicases

resolve R-loops by unwinding the RNA:DNA hybrid. Senataxin (SETX)

is a key helicase that resolves R-loops during transcription

termination, preventing persistent hybrids at gene 3′ ends

(17). The Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp box

(DEAD-box) RNA helicases DEAD-box helicase (DDX)19 and DDX21 are

also important; DDX21 unwinds R-loops at ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes

and collaborates with NAD-dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-7

to suppress R-loops during replication stress (18,19).

Other factors involved in R-loop suppression include

the transcription-export (THO) complex/3′ repair exonuclease

complex, which couples transcription to mRNA export and various

RNA-processing factors, such as splicing factors. Comprehensive

mRNA splicing and 3′ end processing are important to prevent

R-loops; if transcription outpaces processing or if splicing is

defective, the unprocessed nascent RNA is more prone to hybridize

with DNA. This increase in hybridization due to insufficient mRNA

processing explains why mutations in spliceosome genes, such as

splicing factor 3b subunit 1 and U2 small nuclear RNA

auxiliary factor 1, can induce R-loop accumulation and activate

DNA damage responses (DDRs) (12,14).

HCC context

Homeostatic mechanisms may be altered in HCC. Tumor

cells often have markedly elevated transcriptional activity, which

can favor R-loop formation beyond the capacity of normal regulatory

mechanisms. There is evidence that HCC cells upregulate certain

R-loop-resolving factors, presumably to cope with the increased

R-loop load (1,2). In HCC, dysregulated R-loops

contribute to genomic instability by inducing replication stress

and DNA double-stranded breaks, thereby activating the ataxia

telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR)-checkpoint kinase

(CHK)1 and ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-CHK2 DNA damage

response pathways (2,6). Oncogenic drivers such as

metastasis-associated protein 2 (MTA2) promote R-loop formation at

the promoters of differentiation genes such as β-hydroxybutyrate

dehydrogenase 1 (BDH1), leading to epigenetic silencing

and enhanced stemness in HCC cells (9). Furthermore, unresolved R-loops can

initiate inflammatory responses through cytosolic DNA-sensing

pathways, such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase and stimulator of

interferon genes (cGAS-STING), contributing to immune modulation

within the tumor microenvironment (TME) (1). For instance, RNASEH1 expression is

elevated in breast cancer, colorectal cancer, leukemia, and HCC and

associated with poor prognosis (2). One study noted that a long non-coding

RNA (lncRNA) antisense to RNASEH1 (RNASEH1-AS1) is frequently

upregulated in HCC and associated with worse survival prognosis

(10). Additionally, certain

oncogenic pathways in HCC actively induce R-loops to alter gene

expression, such as the chromatin modifier MTA2, which increases

R-loops at specific gene promoters (9). Thus, the balance between R-loop

formation and resolution is maintained in HCC cells.

R-loops in transcriptional regulation

and epigenetics

In addition to their impact on DNA stability,

R-loops can influence gene expression and the chromatin state.

Physiological R-loops often occur in the promoter or terminator

regions of genes and have regulatory functions (2). For example, R-loops formed over

5′-cytosine-phosphate-guanine-3′ island promoters maintain an open

chromatin configuration by displacing nucleosomes, thereby

facilitating transcription initiation of these genes (19). R-loops at the gene termini have

been implicated in pausing RNA polymerase II and promoting

transcription termination (20,21).

These co-transcriptional R-loops can recruit or

occlude specific factors. One study showed that promoter-proximal

R-loops can attract DNA demethylases, leading to local DNA

hypomethylation and robust gene expression (2). Conversely, stable R-loops on gene

bodies or regulatory elements may interfere with transcriptional

elongation, effectively repressing these loci. Furthermore, R-loops

interact with chromatin-modifying complexes and alter histone

marks, modulate chromatin accessibility and either promote or

repress gene transcription (5).

For example, R-loop structures are recognized by the polycomb

repressive complex and DNA methyltransferases, linking hybrid

formation to heritable epigenetic changes (2).

These R-loops may be co-opted or dysregulated in

cancer cells, including HCC cells. A notable HCC-related example is

the MTA2 pathway; MTA2, a component of the nucleosome remodeling

and deacetylase chromatin-remodeling complex, increases R-loop

formation at the promoter of BDH1, which is a gene that

influences both differentiation and metabolism (9,22).

The R-loop recruits histone deacetylase

(HDAC)2/chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 4 (CHD4)

specifically to the promoter region of BDH1, leading to the

epigenetic silencing of BDH1 and stemness in HCC cells

(9,23). Thus, an oncogenic factor exploits

R-loop formation as part of a transcriptional repression mechanism

that favors tumor cell dedifferentiation and self-renewal.

Another example involves the THO complex (THOC).

THOC1 knockdown impairs the THO complex's role in

co-transcriptional RNA processing and export, causing RNA-DNA

hybrids to accumulate, which increases R-loop formation and

consequent DNA damage, which paradoxically leads to reduced tumor

cell proliferation, indicating that THOC1 aids HCC cells by

preventing lethal levels of R-loop accumulation (8). This suggests that HCC cells require

proper mRNA processing to avoid transcription-associated damage.

Therefore, R-loops serve as both outputs and regulators of

transcription. With widespread transcriptional reprogramming, HCC

cells are likely to exhibit an altered landscape of R-loops across

the genome. The influence of R-loops on oncogenic gene expression

is bidirectional: Certain R-loops promote tumor progression by

activating oncogenes or enhancing stemness, while others suppress

tumor progression by inducing transcriptional repression or DNA

damage-mediated checkpoints (1,6). The

interplay between R-loops and epigenetic machinery is a frontier

area; for instance, how R-loop formation might interface with the

frequent epigenetic alterations seen in HCC.

R-loops and genome instability

One of the most important aspects of R-loops is

their ability to induce DNA damage, if not properly mitigated.

During the S phase, the coexistence of transcription and

replication machinery on the DNA template can lead to

transcription-replication conflicts. R-loops are a prominent source

of such conflicts. An R-loop can impede the replication fork,

especially when it collides with the transcription complex

(2). Conflicts are particularly

deleterious in a head-on orientation, when transcription and

replication move toward each other on opposite strands, as the

replication fork encounters the R-loop and stalled RNA polymerase

headlong (23). Head-on

transcription-replication conflicts markedly increase the

likelihood of fork stalling or collapse, resulting in DNA

double-strand breaks (DSBs) and chromosome rearrangements (2,24).

ATR and ATM activation

ATR kinase is a central responder to replication

stress caused by R-loops. Stalled replication forks with stretches

of single-stranded DNA coated with replication protein A activate

ATR, which, in turn, phosphorylates CHK1 and coordinates fork

stabilization (25). ATR signaling

is associated with head-on collisions. Notably, ATR not only halts

the cell cycle to provide time for repair, but also actively

promotes R-loop resolution (3), as

ATR signaling recruits SETX to transcription-replication clash

sites to help unwind R-loops (2).

Similar to ATR, the ATM kinase is activated when

R-loop-associated DSBs are formed. ATM can promote end resection

and homologous recombination (HR) or facilitate non-homologous end

joining, depending on the cell cycle stage and local chromatin

environment (2). ATM-CHK2 and

ATR-CHK1 are both engaged in response to R-loops; however, R-loops

that result in DSBs preferentially trigger ATM, whereas those that

cause stalled forks without immediate breakage primarily trigger

ATR (26).

Notably, the ATR and ATM signaling pathways suppress

R-loop-driven instability. R-loop accumulation is notably toxic to

cells lacking these kinases or their downstream factors. For

example, deficiencies in the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway lead to

hypersensitivity to R-loop-induced DNA damage (27). FA proteins such as FA group D2

protein bind R-loops and stalled forks, stabilizing them and

recruiting RNASEH2 to remove RNA:DNA hybrids. Breast cancer

susceptibility gene (BRCA)1, apart from its role in HR repair,

directly contributes to resolving R-loops by recruiting SETX to

stalled transcription sites (28).

Similarly, BRCA2 knockdown leads to abnormal R-loop accumulation,

DNA breaks and chromosomal aberrations (29).

Genomic instability in HCC

The relevance of these mechanisms in HCC is

supported by several observations. HCC tumors often harbor

mutations or dysregulation of DNA repair genes; for example,

tumor protein P53 is commonly mutated, whilst BRCA2

or ATM mutations are less frequent but occur in subsets.

Even without specific DDR mutations, chronic replication stress in

HCC likely indicates that HCC cells rely heavily on ATR-CHK1

signaling to survive (30,31).

If R-loops are prevalent in HCC cells, ATR would be

expected to remain continuously engaged in managing

replication-transcription conflicts. Recent research has shown that

HCC cells with high R-loop scores exhibit an activated defined set

of genes involved in the DDR pathway and are more reliant on stress

response pathways (1). When R-loop

levels become excessive, cells may enter senescence or apoptosis

because of irreparable DNA damage (1,6).

This could act as a barrier to tumor proliferation, which HCC cells

must overcome by enhancing R-loop tolerance. The aforementioned

THOC1 example illustrates that reducing the ability of HCC cells to

resolve R-loops leads to notable DNA damage and slow proliferation

in HCC cells (8).

Furthermore, etiological factors such as HBV can

exacerbate genomic instability in HCC via R-loops. HBV genome

integration and HBV X protein (HBx) expression interfere with host

DNA repair. Although not yet supported by evidence, it is

conceivable that HBV infection facilitates R-loop accumulation, for

instance, by causing replication stress or by HBx-mediated

downregulation of the RNASEH or ATR pathways (32).

In summary, R-loop-induced DNA damage is likely

associated with myriad sources of genomic instability in HCC. The

ability of HCC cells to survive and proliferate may depend on how

effectively they activate ATR/ATM and associated repair factors to

manage R-loop conflicts.

Signaling pathway and function of

R-loop in HCC

Aberrant R-loop accumulation can provoke DDRs,

contributing to genomic instability in liver cancer (6). THOC1 knockdown triggers R-loop

accumulation and DNA damage and curbs tumor proliferation (8). Excess R-loops can also initiate

innate immune signaling; cytosolic RNA:DNA hybrids excised from

nuclear R-loops activate the cGAS-STING pathway and related

receptors, leading to interferon regulatory factor 3-driven

inflammatory cascades and tumor cell apoptosis (13). Furthermore, the dynamics of R-loops

intersect with cancer metabolism. High R-loop levels are associated

with metabolic reprogramming, for instance, the HCC R-loop score

correlates with elevated lipid synthesis and an immunosuppressive

microenvironment (1). Elevated

lipid synthesis provides energy and membrane components to support

rapid HCC cell proliferation, while an immunosuppressive

microenvironment inhibits anti-tumor immune responses, together

promoting tumor growth and progression. Upregulation or increased

activity of specific R-loop regulators such as clathrin heavy chain

1 (CLTC) enhances fatty acid metabolism, providing energy and

biosynthetic substrates that support tumor growth and survival

(1). Finally, R-loops interact

with epigenetic mechanisms and result in both tumor promotion and

suppression; the chromatin modifier MTA2 creates R-loops to repress

BDH1. The increase in histone β-hydroxybutyrylation is a

direct consequence of BDH1 repression. BDH1 normally metabolizes

β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB); when BDH1 is repressed, BHB accumulates,

serving as a substrate for histone β-hydroxybutyrylation, which

promotes pro-tumorigenic gene expression and stemness (9).

Similarly, RNA-binding proteins such as G patch

domain-containing protein 4 (GPATCH4) guard ribosomal DNA loci by

unwinding nucleolar R-loops. This activity of GPATCH4 primarily

drives HCC progression. By unwinding nucleolar R-loops, it

maintains rRNA transcription and protein synthesis, supporting

rapid proliferation and tumor growth. However, GPATCH4 could also

represent a therapeutic vulnerability, as its inhibition may

increase R-loop accumulation, impair ribosome biogenesis, and

selectively stress HCC cells (33). Collectively, these findings

indicate that R-loops engage multiple signaling pathways, including

DNA damage repair, immune surveillance, metabolic adaptation and

epigenetic regulation, all of which can drive HCC progression or

present therapeutic vulnerabilities (34).

R-loop dysregulation and its dual role

in HCC

Dysregulation of R-loops in HCC is associated with

context-dependent pro- and antitumor effects (6). Abnormal R-loop accumulation causes

genomic instability and DNA breaks that, beyond repair thresholds,

trigger replicative senescence or cell death, thereby suppressing

cancer proliferation (6). For

example, unresolved R-loops arising from THOC1 depletion or GPATCH4

loss in HCC cells can lead to DNA damage, impaired proliferation

and heightened chemosensitivity (8). Thus, cancer cells often upregulate

R-loop-resolving factors such as THOC1, GPATCH4 and

tonicity-responsive enhancer-binding protein to avoid lethal R-loop

stress.

By contrast, dysregulation of R-loop formation can

drive HCC progression. R-loop formation can activate oncogenic

pathways or silence tumor suppressors (1,6). As

aforementioned, MTA2 induces R-loops at the BDH1 locus,

repressing differentiation-linked metabolism and sustaining cancer

stemness (9). Similarly, elevated

R-loop levels (via CLTC or other R-loop regulators) reprogram lipid

metabolism and correlate with an immunosuppressive

microenvironment, ultimately promoting HCC proliferation (1). Excessive R-loops activate cGAS-STING

signaling, inducing type I interferons and cytokines that recruit

cytotoxic immune cells, which directly kill tumor cells and enhance

immune surveillance, thereby constraining HCC growth and

progression (1).

R-loops and the TME

R-loop dysregulation contributes to the malignant

behavior of HCC cells and is closely associated with changes in the

TME. As aforementioned, MTA2 promote R-loop accumulation at the

BDH1 locus, silencing this metabolic gene via the

recruitment of HDAC2/CHD4 and enhancing cancer stemness and

invasiveness (9). Additionally,

elevated R-loop levels in HCC have been shown to upregulate lipid

metabolic pathways via regulators such as CLTC, promoting tumor

cell proliferation and tumor aggressiveness (1). These metabolic shifts reshape the TME

by increasing immunosuppressive signaling and nutrient competition

with paracancerous cells. Furthermore, unresolved R-loops generate

cytosolic DNA fragments that activate cGAS-STING signaling, drive

type I interferon responses and alter immune cell infiltration

(6,35). Hypoxic or inflammatory TMEs may

also exacerbate R-loop formation by impairing RNA processing or TOP

activity, further aggravating replication stress (3). Thus, R-loops and HCC TMEs exist in a

bidirectional relationship that fuels tumor progression.

Therapeutic strategies targeting R-loops in

HCC

Given their notable roles in genome stability and

gene regulation, R-loops and their regulatory machinery are

promising targets for any other cancer therapy methods (2). In HCC, where standard treatments

often achieve a relatively low rate of curing HCC in advanced

stages, exploiting R-loop vulnerabilities may offer novel

approaches. Therapeutic strategies can broadly aim to either reduce

pathological R-loops or increase the R-loop burden beyond a

tolerable threshold. The latter approach leverages the concept of

synthetic lethality, targeting the ‘Achilles heel’ of R-loop

processing in cancer cells.

Small-molecule approaches

TOP inhibitors

TOPs prevent excessive R-loop formation; therefore,

drugs that inhibit them can increase R-loop levels, leading to

cytotoxic effects (12). TOP1

inhibitors such as camptothecin and its derivatives trap TOP1 on

DNA, preventing it from relieving supercoils (36,37).

This increases negative supercoiling behind transcription complexes

and promotes R-loop formation (12). Trapped TOP1 also leads to transient

DNA breaks that are converted into lethal collisions in the

presence of R-loops (36). In HCC,

TOP inhibitors have shown some therapeutic efficacy in preclinical

experimental models, including cell lines and mouse xenograft

models, by inducing DNA damage; their ability to exacerbate R-loop

formation is a notable contributor to this damage (12).

ATR and CHK1 inhibitors

As described, ATR kinase is important for cancer

cells to survive R-loop-driven replication stress. Therefore,

inhibition of ATR can experimentally reveal the lethal consequences

of R-loops on tumor cells. Preclinical studies have shown strong

synergy between ATR inhibitors and R-loop accumulation (24,38).

For example, cancer cells with RNASEH2 dysfunction accumulate

R-loops and rely on ATR to mitigate the harmful effects of

accumulated R-loops; treating these cells with an ATR inhibitor

causes notable DNA breaks and apoptosis (1). The same study found that cells

harboring spliceosome mutations accumulate R-loops and show

selective sensitivity to ATR inhibitors (1). Translating this to HCC, ATR

inhibitors may be effective therapeutic agents in tumors with a

high R-loop load or impaired R-loop resolution. ATR inhibitors are

currently in clinical trials for solid tumors and hold potential

for use in combination with an agent that elevates R-loops for the

treatment of HCC (28).

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)

inhibitors

PARP1 inhibitors are the preferred treatment option

for tumors with HR deficiencies. There is an emerging connection

between R-loop incidence and sensitivity to PARP inhibition

(39). R-loops can cause

replication fork collapse and one-ended DSBs, which normally

require HR for repair (40,41).

If HR is compromised, cells become markedly reliant on

PARP-mediated repair of replication-associated breaks, making them

vulnerable to PARP inhibition; in cancer and HCC, PARP inhibitors

exacerbate DNA damage, promote R-loop-induced genomic instability

and trigger apoptosis, selectively suppressing tumor proliferation

(39). Furthermore, R-loops can

sequester BRCA1 and prevent it from localizing to DNA damage sites,

impairing homologous recombination repair (12). Although BRCA1 is wild-type, its

functional unavailability creates an HR defect, increasing genomic

instability (12). In Ewing

sarcoma cells, transcription of the EWS RNA binding protein

1-friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor fusion

oncogene leads to R-loops that sequester BRCA1, rendering the cells

sensitive to PARP inhibitors, similar to BRCA1 mutants (12). Similarly, conditions in HCC that

compromise HR repair can potentially be exploited using PARP

inhibitors.

Splicing/transcription modulators

Compounds that perturb RNA processing can induce

R-loops by leaving nascent transcripts unprocessed. For example,

spliceosome inhibitors such as sudemycin and H3B-8800 cause

widespread splicing disruption, leading to R-loop accumulation and

DNA damage in cancer cells (14).

These inhibitors are proposed for splice-mutant cancers because

such cells already have impaired RNA splicing, which increases

baseline R-loop formation. Inhibiting relevant pathways exacerbates

R-loop accumulation beyond a tolerable threshold, overwhelming DNA

repair and promoting cancer cell death (14). In HCC, direct spliceosome mutations

are rare; however, the use of a splicing modulator can artificially

create an R-loop overload.

Gene editing and molecular

strategies

In addition to conventional drugs, gene editing and

molecular biology techniques offer ways to directly manipulate

R-loops and their regulators in cancer cells. One innovative

approach involves the use of engineered RNASEH to eliminate R-loops

at specific genomic sites. Researchers have developed a

CRISPR/dCas9-RNASEH1 fusion protein, which can be guided by single

guide RNAs to genomic loci and locally resolve R-loops (42,43).

This tool has been used experimentally to target tumorigenic

R-loops; for instance, site-specific R-loop removal improved

cellular reprogramming efficiency in cultured cells (42,43).

In principle, a similar strategy could be used to

target a pathogenic R-loop in HCC; for example, if a particular

R-loop silences a tumor suppressor gene, a targeted RNASEH1 might

reactivate that gene. Conversely, gene editing can be used to

create synthetic vulnerabilities in tumor cells. The CRISPR

knockout of R-loop in HCC cells removes backup mechanisms that

normally compensate for each other, exacerbating DNA damage

(11). This heightened stress

increases sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, such as TOP

inhibitors, ATR inhibitors and PARP inhibitors, which exploit

defects in replication and repair pathways. Another gene-focused

strategy targets non-coding RNAs that modulate R-loops.

RNASEH1-AS1, an antisense lncRNA upregulated in HCC, may attenuate

RNASEH1 function. Using antisense oligonucleotides to knockdown

RNASEH1-AS1 could free RNASEH1 to better resolve R-loops,

potentially reducing genomic instability in tumor cells.

Synthetic lethality and combination

strategies

The concept of synthetic lethality, in which two

non-lethal perturbations kill the cell when combined, is notably

relevant to R-loops (11). The

inherent DNA damage in cancer cells, arising from defects in HR

repair or RNASEH function, activates compensatory pathways like ATR

signaling. ATR responds to replication stress and R-loop-induced

DNA breaks, stabilizing replication forks and coordinating repair

to maintain cell survival. The present review has already discussed

some synthetic lethal pairs, such as RNASEH2 loss and ATR

inhibition (11) or splicing

mutation and ATR inhibition (14).

One combined strategy for therapeutic application to

HCC could be coupling ATR inhibitors with agents that increase

R-loop formation, as aforementioned. Another notable possibility is

the combination of R-loop targeting and immunotherapy. HCC

treatment has included immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in

recent years (44–46). There is evidence that tumors with

increased DNA damage can be more immunogenic due to the activation

of cGAS-STING and type I interferon responses (35). Excess R-loops can activate the

cGAS-STING pathway, as displaced single-stranded DNA or

R-loop-driven DNA breaks generate ligands for this pathway

(1).

A transient burst of R-loop-induced damage may

acutely increase the immunostimulatory signals via the activated

cGAS-STING and type I interferon pathways. Therefore, a short

course of R-loop-inducing therapy can enhance tumor immunogenicity

by increasing DNA damage and immune signaling, making individual

tumors, including HCC, more susceptible to immune checkpoint

inhibitor-mediated targeting (13,47).

Another scenario using synthetic lethality could

involve targeting metabolic pathways that become lethal when the

number of R-loops is high. Single-cell analysis by Chen et

al (1) highlighted a link

between R-loops and lipid metabolism in HCC. The study identified

an 8-gene signature of fatty acid metabolism-related R-loop

regulator genes; inhibiting CLTC reduces fatty acid metabolism,

decreasing lipid synthesis and accumulation in HCC cells. This

metabolic disruption impairs tumor cell proliferation and overall

tumor growth (1).

Challenges in targeting R-loops

Although targeting R-loop biology holds promise for

HCC therapy, notable challenges must be addressed for such

strategies to be effective and safe.

Detection and measurement of

R-loops

The accurate detection of R-loops in cells and

tissues is important. The primary method, DNA-RNA

immunoprecipitation (DRIP) using the S9.6 monoclonal antibody, has

known limitations in terms of specificity (48). Thus, a key challenge is the

identification of patients with HCC who have high R-loop levels or

dysfunctional R-loop regulation. Without reliable diagnostic

assays, patient stratification for R-loop-targeted therapy is

difficult.

Specificity and off-target

effects

Targeting R-loops can affect normal cells because

they are not unique to cancer cells. All rapidly dividing cells

generate R-loops (49). Therapies

such as ATR inhibitors or TOP poisons also affect healthy

proliferating tissues, causing side effects, such as bone marrow

suppression (anemia, neutropenia), gastrointestinal toxicity

(nausea, diarrhea) and hair loss (12). However, cancer selectivity remains

a major challenge. Cancer selectivity is observed in cells with

~2–3 times higher R-loop levels than normal tissues, providing a

therapeutic window for targeting R-loop-dependent

vulnerabilities.

Resistance mechanisms

As with any cancer therapy, tumors may develop

resistance to R-loop-targeting strategies. There are several

plausible resistance routes: i) A tumor under ATR inhibitor

pressure may upregulate compensatory pathways such as ATM or

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (50); ii) a HCC cell may slow its

proliferation or transcription rate to manage R-loop stress

(51); iii) if a small molecule

such as an ATR inhibitor is used, classical drug-specific

resistance mechanisms can occur (52,53);

and iv) the liver TME might shield HCC cells from treatments.

Therapeutic index and safety

A number of R-loop-targeting approaches run the risk

of causing global DNA damage if not controlled. It is important to

avoid therapies that could induce notable genomic instability in

healthy tissues, resulting in secondary malignancies or organ

failure.

Limitations in current knowledge

The mechanisms of R-loops in HCC remain yet to be

fully elucidated. Most mechanistic insights have been obtained from

cell-line studies or other cancer types such as breast cancer,

colorectal cancer and leukemia. Care must be taken when suggesting

that HCC has unique aspects that could influence R-loop dynamics in

ways that have not yet been fully understood.

Future directions

The intersection of R-loop biology and cancer

research is a rapidly advancing field (2,3).

Several promising avenues of investigation are emerging:

Integrative multi-omics profiling of

R-loops in HCC

A more comprehensive understanding of R-loop

dynamics in HCC may be achieved by integrating multiple layers of

data: Genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics and proteomics. At

single-cell resolution, it is possible to profile transcription and

chromatin states, while R-loop mapping remains largely bulk;

emerging methods like scDRIP-seq combined with single-cell ATAC-seq

or RNA-seq enable integrated analyses. These investigative methods

are capable of refining the current understanding of where R-loops

form in HCC genomes, as well as their causes and consequences.

Identifying new therapeutic targets in

the R-loop pathway

The present study has focused on known molecules

that interact with R-loops, such as ATR and RNASEH; however, future

studies may unveil HCC-specific interactions. The list of R-loop

regulatory genes used in recent HCC studies (1) provides a starting point for

identifying novel HCC-specific interactions that includes

unexpected genes that are not previously linked to canonical R-loop

regulation or cancer progression pathways.

R-loop biomarkers for patient

stratification

As therapies that exploit R-loops are introduced to

clinical settings, the parallel development of biomarkers is

needed. Potential biomarkers could be the expression of an R-loop

resolver, mutations in an R-loop-related gene or the direct

measurement of RNA:DNA hybrids in tumor samples, if feasible.

Overcoming challenges: Improved

delivery and combination regimens

Future research should aim to overcome the

challenges outlined in the present review. Nanoparticle- or

virus-based delivery of gene therapies may be refined for drug

delivery. With small-molecule approaches, prodrugs that are

activated in the TME can localize the R-loop-targeting effect

(52,53). This refers to a subset of drugs,

specifically those designed to target R-loops or exploit

R-loop-associated vulnerabilities.

Exploring the R-loop-immune

interface

The relationship between R-loops and the immune

system is an area of study with direct implications for HCC

(1,13). Future studies could clarify this by

manipulating R-loops in vivo and observing immune

responses.

Clinical translation and trials

Finally, the culmination of these future directions

of study will be clinical trials that test R-loop-targeted

therapies in patients with HCC. For instance, a trial of an ATR

inhibitor in combination with an approved HCC therapy could be

designed for patients whose tumors exhibit a predefined R-loop

signature.

Study limitations

The present review had several limitations that

warrant consideration. First, most mechanistic insights into

R-loops in HCC have been derived from in vitro studies or

non-HCC cancer models (6).

Although previous data from single-cell and bulk transcriptomic

analyses have suggested altered R-loop dynamics in HCC, these

findings require validation using in vivo models and human

tissue samples. Second, current methods for R-loop detection, such

as DRIP-seq using the S9.6 antibody, suffer from limited

specificity and potential cross-reactivity with double-stranded

RNA, which may lead to the misinterpretation of hybrid prevalence

and localization. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of HCC, driven by

diverse etiologies such as HBV infection, metabolic syndrome and

alcohol-related liver disease, poses challenges in generalizing

R-loop-associated mechanisms across all patient subsets. Finally,

although the concept of targeting R-loops therapeutically, such as

via ATR or PARP inhibition, is compelling, clinical evidence in HCC

remains lacking of evidence of the efficacy of these inhibitors

in vivo in HCC, and potential off-target effects or

resistance mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. Future studies

should focus on refining detection techniques, validating key

pathways in patient-derived models and integrating R-loop profiling

into prospective therapeutic trials.

Conclusion

R-loops represent a notable interface between

transcriptional regulation and genomic stability in cancer.

Understanding R-loop biology is particularly relevant in HCC, a

cancer characterized by genomic instability and complex molecular

drivers. The present review provided an overview of R-loop

formation and function (Fig. 1)

and discussed the mechanistic impact of R-loops on transcriptional

regulation and genome stability in HCC. The present review has

discussed how HCC cells manage or mismanage R-loops and how this

knowledge may provide the foundation for novel therapeutic

strategies.

By integrating advanced genomic tools, identifying

novel targets and biomarkers and addressing current challenges,

therapies can be developed that either exploit the toxic potential

of R-loops to destroy cancer cells or correct the underlying

dysregulation of R-loops that contributes to HCC development.

Ultimately, these efforts aim to improve the outcomes of patients

with HCC by composing novel strategies of cancer therapy that

target the fundamental intersection of transcription and genome

stability.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research was funded by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital

(grant nos. CMRPG8Q0181 and CORPG8N0241).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

CHH was responsible for writing the original draft,

conceptualization and funding acquisition. YWL revised the

manuscript. PCC was responsible for editing the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ATM

|

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

|

|

ATR

|

ataxia telangiectasia and

Rad3-related protein

|

|

BDH1

|

β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1

|

|

BRCA

|

breast cancer susceptibility gene

|

|

CHK1

|

checkpoint kinase 1

|

|

DDR

|

DNA damage response

|

|

DRIP

|

DNA-RNA immunoprecipitation

|

|

DSB

|

double-strand break

|

|

FA

|

Fanconi anemia

|

|

HBV

|

hepatitis B virus

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

HDAC

|

histone deacetylase

|

|

HR

|

homologous recombination

|

|

lncRNA

|

long non-coding RNA

|

|

MTA2

|

metastasis-associated protein 2

|

|

PARP

|

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

|

|

RNASEH

|

ribonuclease H

|

|

SETX

|

Senataxin

|

|

THOC

|

THO complex

|

|

TOP1

|

topoisomerase I

|

References

|

1

|

Chen L, Yang H, Wei X, Liu J, Han X, Zhang

C, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Li Y, et al: Integrated single-cell and

bulk transcriptome analysis of R-loop score-based signature with

regard to immune microenvironment, lipid metabolism and prognosis

in HCC. Front Immunol. 15:14873722025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Li F, Zafar A, Luo L, Denning AM, Gu J,

Bennett A, Yuan F and Zhang Y: R-Loops in genome instability and

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 15:49862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rinaldi C, Pizzul P, Longhese MP and

Bonetti D: Sensing R-Loop-Associated DNA damage to safeguard genome

stability. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:6181572021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Li D, Shao F, Li X, Yu Q, Wu R, Wang J,

Wang Z, Wusiman D, Ye L, Guo Y, et al: Advancements and challenges

of R-loops in cancers: Biological insights and future directions.

Cancer Lett. 610:2173592025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Qiu Y, Man C, Zhu L, Zhang S, Wang X, Gong

D and Fan Y: R-loops' m6A modification and its roles in cancers.

Mol Cancer. 23:2322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Baek H, Park SU and Kim J: Emerging role

for R-loop formation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Genomics.

45:543–551. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Peng TW, Ma QF, Li J, Wang X, Zhang CH, Ma

J, Li JY, Wang W, Zhu CL and Liu XH: HBV promotes its replication

by up-regulating RAD51C gene expression. Sci Rep. 14:26072024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cai S, Bai Y, Wang H, Zhao Z, Ding X,

Zhang H, Zhang X, Liu Y, Jia Y, Li Y, et al: Knockdown of THOC1

reduces the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma and increases

the sensitivity to cisplatin. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:1352020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang H, Chang Z, Qin LN, Liang B, Han JX,

Qiao KL, Yang C, Liu YR, Zhou HG and Sun T: MTA2 triggered R-loop

trans-regulates BDH1-mediated β-hydroxybutyrylation and potentiates

propagation of hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 6:1352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sun J, Li Y, Tian H, Chen H, Li J and Li

Z: Comprehensive analysis identifies long non-coding RNA

RNASEH1-AS1 as a potential prognostic biomarker and oncogenic

target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 14:996–1014.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang C, Wang G, Feng X, Shepherd P, Zhang

J, Tang M, Chen Z, Srivastava M, McLaughlin ME, Navone NM, et al:

Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal synthetic lethality of RNASEH2

deficiency and ATR inhibition. Oncogene. 38:2451–2463. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Saha S and Pommier Y: R-loops, type I

topoisomerases and cancer. NAR Cancer. 5:zcad0132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Crossley MP, Song C, Bocek MJ, Choi JH,

Kousouros JN, Sathirachinda A, Lin C, Brickner JR, Bai G, Lans H,

et al: R-loop-derived cytoplasmic RNA-DNA hybrids activate an

immune response. Nature. 613:187–194. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Flach J, Jann JC, Knaflic A, Riabov V,

Streuer A, Altrock E, Xu Q, Schmitt N, Obländer J, Nowak V, et al:

Replication stress signaling is a therapeutic target in

myelodysplastic syndromes with splicing factor mutations.

Haematologica. 106:2906–2917. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Yang S, Winstone L, Mondal S and Wu Y:

Helicases in R-loop formation and resolution. J Biol Chem.

299:1053072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kellner V and Luke B: Molecular and

physiological consequences of faulty eukaryotic ribonucleotide

excision repair. EMBO J. 39:e1023092020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hasanova Z, Klapstova V, Porrua O, Stefl R

and Sebesta M: Human senataxin is a bona fide R-loop resolving

enzyme and transcription termination factor. Nucleic Acids Res.

51:2818–2837. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Song C, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Voit R and

Grummt I: SIRT7 and the DEAD-box helicase DDX21 cooperate to

resolve genomic R loops and safeguard genome stability. Genes Dev.

31:1370–1381. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hodroj D, Serhal K and Maiorano D: Ddx19

links mRNA nuclear export with progression of transcription and

replication and suppresses genomic instability upon DNA damage in

proliferating cells. Nucleus. 8:489–495. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mérida-Cerro JA, Maraver-Cárdenas P,

Rondón AG and Aguilera A: Rat1 promotes premature transcription

termination at R-loops. Nucleic Acids Res. 52:3623–3635. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Xu C, Li C, Chen J, Xiong Y, Qiao Z, Fan

P, Li C, Ma S, Liu J, Song A, et al: R-loop-dependent

promoter-proximal termination ensures genome stability. Nature.

621:610–619. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang Y, Qiu R, Zhao S, Shen L, Tang B,

Weng Q, Xu Z, Zheng L, Chen W, Shu G, et al: SMYD3 associates with

the NuRD (MTA1/2) complex to regulate transcription and promote

proliferation and invasiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

BMC Biol. 20:2942022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhou T, Cheng X, He Y, Xie Y, Xu F, Xu Y

and Huang W: Function and mechanism of histone

β-hydroxybutyrylation in health and disease. Front Immunol.

13:9812852022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Liu J, Li F, Cao Y, Lv Y, Lei K, Tu Z,

Gong C, Wang H, Liu F and Huang K: Mechanisms underlining R-loop

biology and implications for human disease. Front Cell Dev Biol.

13:15377312025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Matos DA, Zhang JM, Ouyang J, Nguyen HD,

Genois MM and Zou L: ATR protects the genome against R Loops

through a MUS81-triggered feedback loop. Mol Cell. 77:514–527.e4.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

González-Marín B, Calderón-Segura ME and

Sekelsky J: ATM/Chk2 and ATR/Chk1 pathways respond to DNA damage

induced by Movento® 240SC and Envidor® 240SC

Keto-enol insecticides in the germarium of drosophila melanogaster.

Toxics. 11:7542023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Okamoto Y, Hejna J and Takata M:

Regulation of R-loops and genome instability in Fanconi anemia. J

Biochem. 165:465–470. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sharma AB, Ramlee MK, Kosmin J, Higgs MR,

Wolstenholme A, Ronson GE, Jones D, Ebner D, Shamkhi N, Sims D, et

al: C16orf72/HAPSTR1/TAPR1 functions with BRCA1/Senataxin to

modulate replication-associated R-loops and confer resistance to

PARP disruption. Nat Commun. 14:50032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang Y, Ma B, Liu X, Gao G, Che Z, Fan M,

Meng S, Zhao X, Sugimura R, Cao H, et al: ZFP281-BRCA2 prevents

R-loop accumulation during DNA replication. Nat Commun.

13:34932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Smith MA, Van Alsten SC, Walens A,

Damrauer JS, Maduekwe UN, Broaddus RR, Love MI, Troester MA and

Hoadley KA: DNA damage repair classifier defines distinct groups in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 14:42822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu X, Xu S, Wang P, Wang ZQ, Chen H, Xu X

and Peng B: ASPM promotes ATR-CHK1 activation and stabilizes

stalled replication forks in response to replication stress. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 119:e22037831192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li D, Hamadalnil Y and Tu T: Hepatitis B

viral protein HBx: Roles in viral replication and

hepatocarcinogenesis. Viruses. 16:13612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhao YM, Jiang Y, Wang JZ, Cao S, Zhu H,

Wang WK, Yu J, Liu J and Hui J: GPATCH4 functions as a regulator of

nucleolar R-loops in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Nucleic Acids

Res. 53:gkaf4382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tan SLW, Chadha S, Liu Y, Gabasova E,

Perera D, Ahmed K, Constantinou S, Renaudin X, Lee M, Aebersold R

and Venkitaraman AR: A class of environmental and endogenous toxins

induces BRCA2 haploinsufficiency and genome instability. Cell.

169:1105–1118.e15. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Du H, Xu T and Cui M: cGAS-STING signaling

in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother.

133:1109722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Promonet A, Padioleau I, Liu Y, Sanz L,

Biernacka A, Schmitz AL, Skrzypczak M, Sarrazin A, Mettling C,

Rowicka M, et al: Topoisomerase 1 prevents replication stress at

R-loop-enriched transcription termination sites. Nat Commun.

11:39402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Duardo RC, Marinello J, Russo M, Morelli

S, Pepe S, Guerra F, Gómez-González B, Aguilera A and Capranico G:

Human DNA topoisomerase I poisoning causes R loop-mediated genome

instability attenuated by transcription factor IIS. Sci Adv.

10:eadm81962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Huang TT, Chiang CY, Nair JR, Wilson KM,

Cheng K and Lee JM: AKT1 interacts with DHX9 to Mitigate R

Loop-Induced Replication Stress in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res.

84:887–904. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Petropoulos M, Karamichali A, Rossetti GG,

Freudenmann A, Iacovino LG, Dionellis VS, Sotiriou SK and

Halazonetis TD: Transcription-replication conflicts underlie

sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Nature. 628:433–441. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pavani R, Tripathi V, Vrtis KB, Zong D,

Chari R, Callen E, Pankajam AV, Zhen G, Matos-Rodrigues G, Yang J,

et al: Structure and repair of replication-coupled DNA breaks.

Science. 385:eado38672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Nickoloff JA, Sharma N, Taylor L, Allen SJ

and Hromas R: The safe path at the fork: Ensuring

replication-associated DNA double-strand breaks are repaired by

homologous recombination. Front Genet. 12:7480332021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Khosraviani N, Abraham K, Chan J and

Mekhail K: Locus-associated R-loop repression in cis. bioRxiv.

2021.DOI: 10.1101/2021.05.25.445644. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Li Y, Song Y, Xu W, Li Q, Wang X, Li K,

Wang J, Liu Z, Velychko S, Ye R, et al: R-loops coordinate with

SOX2 in regulating reprogramming to pluripotency. Sci Adv.

6:eaba07772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Boilève J, Guimas V, David A, Bailly C and

Touchefeu Y: Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with

loco-regional treatments in hepatocellular carcinoma: Ready for

prime time? Curr Oncol. 31:3199–3211. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Childs A, Aidoo-Micah G, Maini MK and

Meyer T: Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep.

6:1011302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hao L, Li S, Ye F, Wang H, Zhong Y, Zhang

X, Hu X and Huang X: The current status and future of

targeted-immune combination for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front

Immunol. 15:14189652024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Maxwell MB, Hom-Tedla MS, Yi J, Li S,

Rivera SA, Yu J, Burns MJ, McRae HM, Stevenson BT, Coakley KE, et

al: ARID1A suppresses R-loop-mediated STING-type I interferon

pathway activation of anti-tumor immunity. Cell. 187:3390–3408.e19.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Bou-Nader C, Bothra A, Garboczi DN, Leppla

SH and Zhang J: Structural basis of R-loop recognition by the S9.6

monoclonal antibody. Nat Commun. 13:16412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jazinaki MS, Bahari H, Rashidmayvan M,

Arabi SM, Rahnama I and Malekahmadi M: The effects of raspberry

consumption on lipid profile and blood pressure in adults: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Sci Nutr. 12:2259–2278.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Turchick A, Zimmermann A, Chiu LY, Dahmen

H, Elenbaas B, Zenke FT, Blaukat A and Vassilev LT: Selective

inhibition of ATM-dependent double-strand break repair and

checkpoint control synergistically enhances the efficacy of ATR

inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 22:859–872. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lam FC, Kong YW, Huang Q, Vu Han TL, Maffa

AD, Kasper EM and Yaffe MB: BRD4 prevents the accumulation of

R-loops and protects against transcription-replication collision

events and DNA damage. Nat Commun. 11:40832020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Baxter JS, Zatreanu D, Pettitt SJ and Lord

CJ: Resistance to DNA repair inhibitors in cancer. Mol Oncol.

16:3811–3827. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

O'Leary PC, Chen H, Doruk YU, Williamson

T, Polacco B, McNeal AS, Shenoy T, Kale N, Carnevale J, Stevenson

E, et al: Resistance to ATR inhibitors is mediated by loss of the

nonsense-mediated decay factor UPF2. Cancer Res. 82:3950–3961.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|