Respiratory tract diseases are a major health

problem, associated with high incidence and mortality rates

worldwide (1). Respiratory tract

infections are caused by the invasion and reproduction of

pathogenic microorganisms in the respiratory tract, and can be

broadly divided into upper and lower respiratory tract infections.

Upper respiratory tract infections mainly affect areas at and above

the throat, and include acute and chronic rhinitis, laryngitis and

pharyngitis, while lower respiratory tract infections affect areas

below the throat, and include acute and chronic bronchitis and

pneumonia. The World Health Organization estimates that respiratory

tract diseases were the fourth leading cause of death worldwide in

2016, accounting for nearly 3 million deaths, which corresponds to

~40 deaths per 100,000 population (2).

Children are particularly vulnerable to respiratory

tract diseases, with each child reported to experience up to 12

cases of respiratory tract infection per year (3). Due to their underdeveloped immune

systems, children are also prone to complications from respiratory

tract diseases, including bronchitis, pneumonia, sinusitis and

otitis media (4). Therefore,

respiratory tract infections in children pose a great threat to

health. Mild cases present with local symptoms such as sneezing,

nasal congestion and dry cough, while some children may also

experience symptoms such as a sore throat or discomfort in the

throat (5). However, severe

illness can occur, particularly in infants and young children, with

rapid onset, mild local symptoms and severe systemic symptoms,

manifesting as irritability, high fever, anorexia and fatigue, with

shock and death occurring in the most severe cases (6).

The human microbiota and its surrounding

microenvironment are closely linked to metabolism and health, and

dysbiosis of the microbiota is strongly associated with respiratory

tract diseases. As one of the organs with the most complex

microbiota, the intestines have a marked impact on human health.

The gut microbiota has various effects on human physiology, which

are mediated via a number of different axes, including the gut-lung

(7), gut-brain (8), gut-skeletal muscle (9), gut-organ (10) and gut-cardiac axes (11). Research into the gut microbiota has

explored its influence on a wide range of conditions, including

cancer (12), hypertension

(13), obesity (14) and respiratory diseases (15).

With the advancement of microbial research

techniques, the field of human microbial ecosystems has been

increasingly studied (16).

Although most studies on the microbiome have focused on diseases in

adults, researchers have now started to investigate the role of

microbial ecosystems in pediatric respiratory diseases. Studies of

adults suggest that the gut microbiota can indirectly regulate

pulmonary immune function (17).

The bacterial population in the gut is large and diverse compared

with that in other parts of the body, making it a particularly

valuable topic of research. The development of the gut microbiota

begins at birth, undergoes highly dynamic changes during in the

first years of life and typically stabilizes after 1–3 years

(18).

In the present review, the development of the gut

microbiota during early life and its roles in human health are

described. In addition, the associations of the gut microbiota with

pediatric respiratory tract diseases are reviewed, with a focus on

syncytial viral infections, childhood asthma and cystic fibrosis.

Finally, probiotic-related therapeutic approaches are discussed.

The review aims to provide new insights into the relationship

between gut flora and pediatric respiratory diseases.

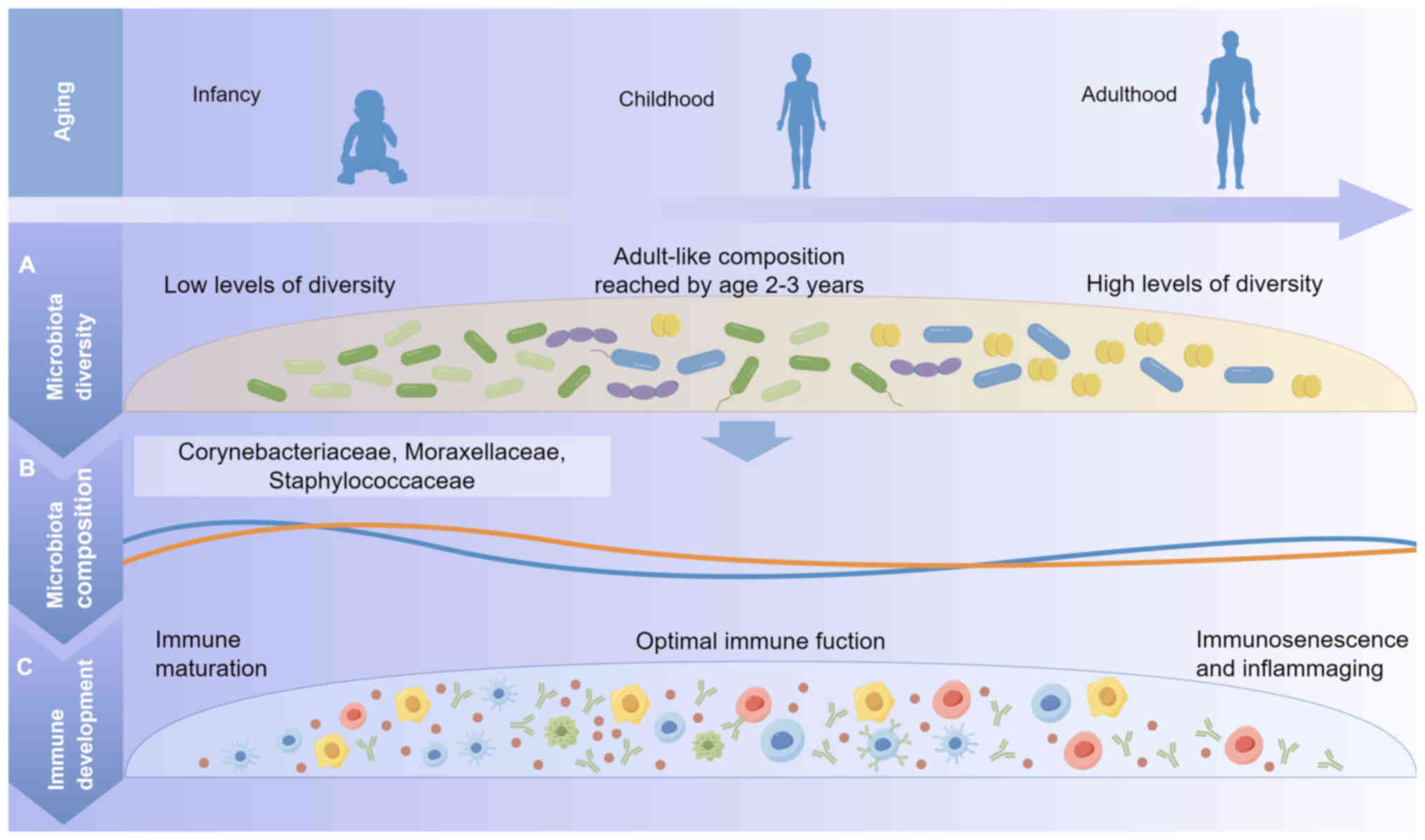

The innate and adaptive immune systems are known to

be influenced by the composition of the gut microbiota during the

first year of life (19). After

birth, the immune system is not yet mature, and the first few years

of life are a critical period for both microbiota establishment and

maturation of the immune system (20). The microbial community participates

in various processes within the body, including metabolism and

regulation of the immune system, thereby playing a vital role in

the overall health of infants (Fig.

1) (21).

The composition of the gut microbiota varies from

birth, and differs in infants born vaginally from those born by

cesarean section (22). Vaginally

delivered infants are exposed to maternal vaginal and fecal

microbiota, resulting in the presence of Lactobacillus,

Prevotella and/or Sneathia in the gut microbiota

(21,23). By contrast, infants delivered by

cesarean section acquire microbiota from maternal skin, hospital

staff or the hospital environment, including Staphylococcus,

Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium (24,25).

Infants born by cesarean section generally exhibit decreased

microbial diversity compared with that of vaginally delivered

infants (26). However, the gut

microbiology of infants delivered by emergency cesarean section

more closely resembles that of vaginal deliveries, likely due to

partial exposure to the birth canal during early labor (27,28).

Although the intrauterine environment was originally assumed to be

sterile, the presence of a unique microbial environment has been

identified in the placenta, comprising non-pathogenic commensal

microbiota. This indicates that even during embryonic development,

certain microorganisms may be in contact with and influence the

fetus (29).

The earliest microbiota colonizing the infant gut

are aerobic or parthenogenetic anaerobic bacteria, such as

Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus and Staphylococcus.

As anerobic bacteria increase and oxygen is consumed, the first

strict anaerobes begin to proliferate, including

Bifidobacterium, Clostridium and Lactobacillus. Among

these, Bifidobacterium is one of the most predominant

bacterial genera in the gut microbiota of human infants (30). In addition, preterm infants born at

less than 37 weeks' gestation typically exhibit a reduced gut

microbial diversity and lower levels of Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus acidophilus (L. acidophilus) (31). Their gut microbiota may be altered

due to factors such as exposure to medication or artificial feeding

(32). Preterm infants also

exhibit delayed gut colonization by commensal anerobic

microorganisms, such as Bifidobacterium or

Lactobacillus, and significantly elevated fecal levels of

pathogenic microorganisms, including Enterobacteriaceae and

Enterococcus (33,34).

Research has consistently demonstrated that

breastfeeding provides a wide range of health benefits for infants

(35). Breast milk contains

various bioactive components essential for infant growth and

development, including immunomodulatory factors, growth hormones,

antimicrobials and prebiotics (36). It has been hypothesized that the

inability of human milk oligosaccharides, which are abundant in

breast milk, to be digested by infants plays a crucial role in

shaping of the infant gut microbiota and protecting against

infection (37,38).

The gut microbiota of formula-fed infants consists

primarily of parthenogenetic anaerobes, such as

Lactobacillus and Clostridium. Differences between

the microbial communities of breastfed and formula-fed infants have

been associated with long-term health outcomes, including an

increased risk of developing allergic disease in formula-fed

infants, whereas breastfeeding is protective (40). To address this, prebiotics such as

short-chain galacto-oligosaccharides and long-chain

fructo-oligosaccharides are often added to formula milk. They

selectively promote the growth of Bifidobacterium and reduce

the abundance of Enterococcus and Escherichia coli,

thereby improving the composition of the gut microbiota (41). Although current infant formulas are

unable to fully replicate the beneficial effects of breast milk on

the gut microbiota, advances in prebiotic formulations have been

shown to have a positive effect on infants (such as establish the

gut microbiota and promote the colonization of bifidobacteria)

(42).

Antibiotic treatment and malnutrition are two major

factors that affect the gut microbiota, leading to gut dysbiosis

(43). Disturbances during early

life can impair the composition, maturation and function of the gut

microbiota, leading to adverse health consequences later in life.

While antibiotics are commonly used to treat bacterial infections,

they destroy commensal bacteria in addition to harmful bacteria,

thereby triggering intestinal dysbiosis (44). Early use of antibiotics has been

shown to reduce the number of bifidobacteria in the neonatal gut,

and broad-spectrum antibiotics can significantly alter the

composition and structure of the gut microbiota, reducing its

diversity by >25% (45,46). In addition, maternal antibiotic use

during pregnancy and breastfeeding has been linked with neonatal

microflora dysbiosis (47,48). Antibiotics reduce the diversity of

the breast milk microbiota, thereby decreasing the abundance of

Bifidobacterium in the neonatal gut (49). Malnourished children also exhibit

disturbed intestinal flora, characterized by a significant

reduction in Bifidobacterium and an altered ratio of aerobic

to anaerobic bacteria in fecal samples, resembling immature

intestinal flora (50).

Malnutrition may also promote inflammation, impair nutrient

absorption and exacerbate gut microflora dysbiosis (51,52).

Some of the factors influencing the gut microbiota in early life

are summarized in Table I

(23,53–58).

The close relationship between the gut and lungs can

be partly attributed to their shared embryonic origin and the fact

that both are exposed to the external environment via the oral

cavity and pharynx, which share physiological and structural

features (59,60). Although the mechanisms underlying

the gut-lung axis are not fully understood, the gut microbiota and

its metabolites play an important role in host defense. Metabolites

produced by the commensal gut microbiota activate and regulate

certain cellular responses required to maintain inflammatory tone,

thereby promoting microbiota-host homeostasis (61). The anaerobic fermentation of

dietary fiber by the gut microbiota produces short-chain fatty

acids with immunomodulatory functions, including the inhibition of

immune cell chemotaxis and adhesion, induction of anti-inflammatory

cytokine expression, and stimulation of apoptosis in immune cells

(62). These fatty acid

metabolites also increase the number and function of T regulatory

(Treg), T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 effector cells through the

inhibition of histone deacetylases, thereby reducing excessive

inflammation and immune responses in respiratory tract diseases

(63).

There are significant differences in the overall gut

microbiome composition between patients with chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD) and healthy individuals (64). The fecal microbiome of patients

with COPD shows increased abundances of Streptococcus, Rothia,

Romboutsia, Streptococcus spp., and Escherichia, with

Streptococcus considered to be a key factor differentiating

samples from patients with COPD from those from healthy individuals

(65). The gut microbiota is

particularly relevant to respiratory health. For example, exposure

to gut commensal bacteria immediately after birth has been shown to

promote the migration of group 3 innate lymphoid cells into the

lungs of neonatal mice to help defend against pneumonia, whereas

the same treatment in adult mice has limited effects on pneumonia

susceptibility (66). Another

study in mice demonstrated that colonization with gut microbes

during the neonatal period reduces the likelihood of allergic

asthma by preventing ovalbumin-induced aggregation of invariant

natural killer T cells to the lungs and by reducing

hypermethylation of the CC motif chemokine ligand 16 gene (67).

The administration of microbial metabolites,

microbial components or probiotics to mice improves their immune

response and survival when exposed to lung pathogens, with

detectable changes in the microbiota of the gut and lungs (68). A study by Luoto et al

(69) found that prebiotic

treatment with a mixture of galacto-oligosaccharides and

polydextrose, or probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus

rhamnosus GG (LGG), reduced the incidence of upper respiratory

tract infections in preterm neonates. Similarly, Maldonado et

al (70) observed a reduced

incidence of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections in

neonates following the administration of Lactobacillus

fermentum and galacto-oligosaccharides. In addition, a

meta-analysis of 23 trials and 6,269 children performed by Wang

et al (71) demonstrated

that probiotic supplementation reduced the incidence of upper

respiratory tract infections, with the evidence rated as moderate

quality.

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as loss of appetite,

nausea and vomiting occur in 20–60% of patients with coronavirus

disease 19 (COVID-19). These symptoms may appear earlier than

respiratory symptoms exhibit an association with severe disease

progression (72). Differences in

the composition of the gut microbiota between individuals infected

with COVID-19 and controls have been detected, with reductions of

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bifidobacterium bifidum

(B. bifidum) populations in COVID-19-infected patients, which

are inversely correlated with disease severity (73,74).

The remainder of this section examines the

relationship between the gut microbiota and respiratory tract

diseases, focusing on respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections,

childhood asthma and cystic fibrosis.

Early in life, RSV infection can bias immune

responses toward Th2 or Th17 pathways. This is due to the presence

of thymic stromal lymphopoietin released by airway epithelial

cells, which activates the Th2 response via CD4+ T cells

and type 2 innate lymphocytes (87). Another study found that the RSV

infection of dendritic cells alters histone methylation in the

promoter region of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby reducing

innate Th1-associated inflammatory responses and shifting immunity

towards Th2 inflammation (88).

Both clinical and animal studies indicate that this RSV-induced

immune profile persists even after recovery from infection

(89,90). Notably, the gut microbiota can

suppress inflammation and modulate the immune response. A

systematic review of the literature suggests that the gut

microbiome of RSV-infected individuals differs from that of healthy

controls (91), a finding

supported by a study of animals (92). Furthermore, a summary review

reports that the administration of bacterial lysates designed to

act on the gut microbiota modulates immunity and reduces the

frequency and severity of respiratory infections in children

(93).

The prevalence of asthma in children aged 5–14 years

is ~10%, making it the most common chronic disease worldwide.

Validated tools or methods to confirm the diagnosis of asthma in

children <5 years of age are lacking, despite asthma-like

symptoms appearing before the age of 2 years in some cases

(94,95). Asthma is a complex disease

characterized by clinical symptoms such as wheezing, cough, chest

tightness and dyspnoea, along with bronchial obstruction,

hyper-responsiveness to triggers such as infections, allergies,

pollution, climate or physical activity, and airway inflammation.

Symptoms vary with age, exposure to triggers or treatment (96). Asthma can also be classified into

subtypes, with the most common childhood form being allergy-related

and mediated by Th2 cells (97).

Th2 cell-mediated asthma is characterized by airway eosinophilic

inflammation, activated by innate epithelial mediators, including

IL-25 and IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin. These mediators

are secreted by airway epithelial cells in response to allergens,

smoke, pollutants, microbes and other irritants. Genetic and

epigenetic factors have been shown to influence the development of

asthma (98).

The gut microbiota has been demonstrated to play a

role in childhood asthma. In a cohort study, children born to

mothers with asthma had immature gut microbiota at 1 year of age,

which was associated with an increased risk of developing asthma by

age 5 years, whereas this association was not observed in children

without maternal asthma (99). The

study observed that the abundance of Veillonella in the

intestines of children born to asthmatic mothers at 1 year was

positively associated with asthma at 5 years, while the abundance

of Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis), Bifidobacterium,

Roseburia, Alistipes, Dialister, Lachnospiraceae incertae

sedis and Ruminococcus was negatively associated.

Another study found that newborns with a higher abundance of E.

faecalis, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Akkermansia

in the gut microbiota had a lower 4-year risk of developing asthma

(100). Factors such as mode of

delivery, feeding practices and antibiotic use have been shown to

influence the gut microbiota in infants, and these same factors are

epidemiologically associated with the development of asthma in

children. It has been suggested that the adverse effects of

antibiotic use on childhood asthma may be mediated by interference

with the gut microbiota in infancy, for example, by altering the

relative abundance of various microbes in the gut microbiota and

inducing dysbiosis (101). A

study on breastfeeding and childhood asthma confirmed that part of

the protective effect of breast milk on childhood asthma is

mediated by the composition of the early gut microbiota (102). In addition, a higher abundance of

beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium longum (B.

longum), in the gut microbiota early in life has been

associated with a reduced risk of asthma (103). A recent population-based and

prospective cohort study conducted in British Columbia, Canada

further suggested that the judicious use of antibiotics in infancy

and early childhood may protect the gut microbiota and help to

reduce the incidence of asthma in children (104). Collectively, these findings

support a link between childhood asthma and the gut microbiota.

Studies have shown that the neonatal microbiota in

children with allergic diseases, such as allergic asthma, is

associated with increased Th2 and decreased Treg cell numbers

(105). In addition, the colon,

skin and lungs of germ-free mice have been found to exhibit

increased Th2 and reduced Treg cell numbers, which can be altered

by exposure to commensal microbes early in life (106). Furthermore, an increased

abundance of commensal bacteria, including Lactobacillus,

Clostridium, Lactobacillus and Veillonella, is

associated with improved Treg cell function and may provide

protection against diseases such as childhood asthma (107).

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive disorder

affecting mucus- and sweat-producing cells that affects multiple

organs, primarily the lungs and digestive system. It leads to

impaired mucus clearance and bacterial infections of the airways

(108). This disease is

predominantly prevalent in Caucasian populations, with estimated

prevalence rates of 1/3,000 in Europe and 1/6,000 worldwide

(109). Cystic fibrosis lung

disease is characterized by thickened airway secretions, bacterial

infection and inflammation, which progressively cause airway

destruction, leading to bronchiectasis and ultimately respiratory

failure (110). This condition is

caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane

conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which leads to the defective

function or absence of CFTR protein, affects the cells that produce

mucus and sweat, causing the mucus to thicken and block the airways

in the lungs. This protein is a chloride channel in the epithelial

cell membrane that also regulates the activity of sodium channels

(111).

It is now widely accepted that the relationship

between the microbiota and cystic fibrosis is bidirectional. CFTR

dysfunction leads to aberrant colonization of the gut and

respiratory microbiota, which in turn alters the intestinal and

airway microenvironment (112). A

study showed that cystic fibrosis-induced changes in the

lungmicrobiota cause changes in the gut microbiota (113). Patients with cystic fibrosis have

been found to exhibit reduced abundances of Ruminococcaceae,

Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides and Roseburia in the

gut, which are normally considered to be healthy commensal gut

microbiota (114–116), and are associated with

anti-inflammatory activity, fermentation, and immune regulation

in vivo (117,118). Unlike the gut microbiota of

healthy children, an increased abundance of Enterococcus,

Enterobacter and Escherichia has been observed in the

intestines of patients with cystic fibrosis, however, there is no

evidence indicating that this variation is definitively associated

with pathogenicity (119–121). The functional characteristics of

the gut microbiota in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis

differ significantly from those without cystic fibrosis (122). Manor et al (123) found that the gut micribiota of

pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis have an increased

propensity to metabolize short-chain fatty acids, nutrients and

antioxidants, with enriched short-chain fatty acid metabolic

pathways and reduced fatty acid biosynthetic pathways, microbiota

dysbiosis and functional imbalance are highly evident, with

functional disparities linked to malabsorption and inflammation. In

addition, another study showed that, despite severe dysbiosis, the

gut microbiota in patients with cystic fibrosis retains the ability

to produce short-chain fatty acids by the fermentation of starch

(124).

The dynamic relationship between the gut microbiota

and respiratory tract diseases in children is increasingly being

recognized. Further in-depth research is required to provide

researchers and clinicians with a more comprehensive and innovative

perspective on the management of childhood respiratory

diseases.

Currently, traditional treatments for respiratory

diseases rely heavily on antibiotics and antiviral drugs, which

must be used with caution in infants and young children to avoid

short- or long-term adverse effects. Widespread use of antibiotics

can lead to serious issues, such as drug resistance, reduced

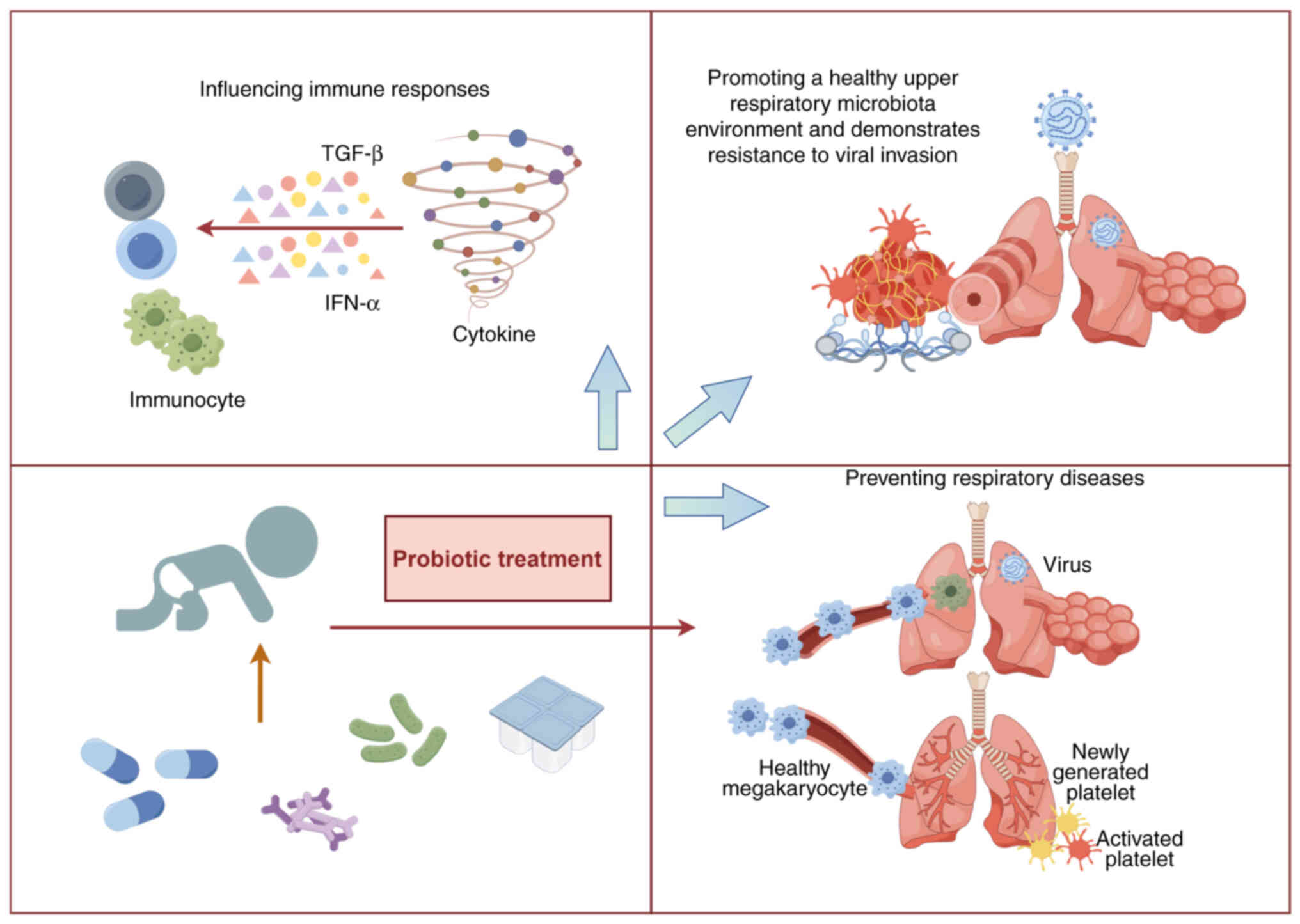

therapeutic efficacy and a substantial societal burden (125). Probiotics have emerged as

effective agents for the regulation of intestinal microecology and

have gained attention in clinical studies for the prevention and

treatment of respiratory diseases in children. Probiotics are

generally defined as live microorganisms that can positively

influence host health (126).

They have been widely used as medicines, food additives or

nutritional supplements for the prevention and treatment of

pediatric diseases due to their recognized beneficial effects

(127). Evidence-based medical

findings have shown that oral probiotics are effective in

preventing respiratory diseases and reducing recurrence rates in

healthy children without any adverse side effects (128). Probiotic intake can promote a

healthy upper respiratory microbiota and enhance resistance to

viral invasion (129,130). The gut microbiota influences

immune responses in multiple mucosal systems, playing a crucial

role in the maintenance of physiological homeostasis and human

health, while dysbiosis of the gut microbiota increases

susceptibility to respiratory diseases (131). Although the etiology of

respiratory diseases is multifaceted, the ability of probiotics to

modulate microecological balance and immune responses has attracted

considerable attention in treatment strategies for respiratory

diseases (Fig. 2) (132).

Probiotics protect the integrity of the epithelial

barrier by activating pattern recognition receptors on epithelial

cells through microbe-associated molecular patterns that regulate

tight and adhesion junctions (136). They also disrupt the

microenvironments of pathogens through competition for epithelial

cell adhesion sites, nutrient depletion and the secretions of

antimicrobial compounds (137).

In addition, probiotic metabolites play an important role in

respiratory diseases by modulating the differentiation of immune

cells and controlling the immune response via G protein-coupled

receptors and histone deacetylases (138).

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue is an important

component of the peripheral immune system, and probiotics have been

shown to enhance systemic immunity and indirectly strengthen

respiratory defense by the modulation of this tissue (139). They also mediate innate immune

responses through pattern recognition receptors, particularly

toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize and bind to

pathogen-associated molecular patterns on the surface of pathogenic

microorganisms and activate signaling pathways, such as the nuclear

factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, to

regulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (140). For example, Lactococcus

lactis (L. lactis) enhances Th1 cell differentiation and

upregulates the expression of cytokines IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α via

TLR2, TLR3 and TLR9 pathways (141).

LGG is currently one of the most widely used

probiotics due to its tolerance of stomach acid and bile. Studies

have shown that LGG can regulate the balance of microbiota in the

gut, reducing harmful bacteria such as Bacteroides and

Proteus, and increasing beneficial bacteria such as

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and butyric acid-producing

bacteria (142,143). In addition, LGG modulates the

host immune system, helping to prevent and treat infections by

triggering an inflammatory response and activating macrophages,

which protect intestinal epithelial cells (144). Several studies have demonstrated

that LGG has favorable preventive, therapeutic and curative effects

on respiratory diseases in children. In a randomized trial

involving 281 children, LGG significantly reduced the risk of upper

respiratory tract infections and shortened the duration of

respiratory symptoms (145),

while a meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials with

1,805 participants showed that LGG reduces the incidence of acute

otitis media while also reducing antibiotic use (146). Other studies have demonstrated

that LGG significantly reduces the overall risk of respiratory

infection and shortens the duration of respiratory symptoms in

children (147). However,

although LGG significantly improves respiratory symptoms, it does

not appear to inhibit viral activity in respiratory tract

infections in children (148).

Interestingly, in another randomized study involving 619

participants aged 2–6 years, LGG effectively relieved symptoms of

upper respiratory tract infection, but was not effective in

reducing the incidence of these infections (149). Despite the multifaceted health

benefits of LGG, the results of the studies show some

inconsistency, suggesting that the efficacy of probiotics may

differ among individuals.

Bifidobacteria are a group of probiotics commonly

found in the human gut, particularly in infants. Their numbers and

species diversity tend to decline with age (150). Studies have shown that

bifidobacteria play an important preventive role in the maintenance

of a healthy gut microbiota by regulating gut microbial metabolism,

promoting intestinal motility, adhering to and degrading harmful

substances, and enhancing host immune function (151). B. longum has been shown to

regulate the Th1/Th2 immune system balance. In a study in Malaysian

preschool children, B. longum BB536 significantly increased

the abundance of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory bacteria in

the feces, thereby preventing upper respiratory tract diseases via

modulation of the gut microbiota (152). Another study showed that the

early administration of Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies

Lactobacillus bifidus BB-12 to infants reduced the risk of

early infections and respiratory tract infections (153).

Probiotic complexes are preparations containing

multiple probiotic strains that regulate the composition and

diversity of the intestinal flora, protect intestinal barrier

function, and reduce inflammation and intestinal damage. Probiotic

complexes have demonstrated superior efficacy than single strains

in maintaining gut health, modulating immune function and single

strain resistance issues (154).

Probiotic complexes have shown the potential to play a positive

role in the prevention and treatment of recurrent respiratory

infections. For example, oral quadruple probiotic tablets

containing B. bifidum, L. acidophilus, E. faecalis and

Bacillus cereus not only increased the abundance of the

beneficial gut bacteria B. bifidum and L. lactis, but

also significantly reduced the mean annual frequency of acute

respiratory infections and antibiotic use (155). Also, another probiotic

preparation containing Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies

Lactobacillus bifidus BB-12 and E. faecalis L3

significantly increased salivary immunoglobulin levels and reduced

the risk of upper respiratory tract infections in healthy children

(156). In addition, a nasal

spray comprising Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB and

Streptococcus oralis 89a was found to be effective in

relieving the symptoms of recurrent respiratory infections in

children (157). Another clinical

study also supports the benefits of probiotic complexes, with a

marked reduction in the incidence of respiratory infections in

children treated with oral probiotics compared with placebo-treated

controls, in addition to a lack of adverse effects (158).

Although numerous probiotic products have been shown

to be safe, their use can also cause adverse reactions (159). Probiotics have been reported to

cause gastrointestinal side effects, including diarrhea and

bloating (160). In addition,

probiotics may facilitate the lateral transfer of antibiotic

resistance genes to other microorganisms (161,162). There have been some reports that

probiotics can act as opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised

individuals, potentially leading to life-threatening diseases such

as pneumonia, endocarditis and sepsis (163–165). Therefore, further research is

necessary to evaluate probiotic therapies for respiratory diseases,

particularly regarding individual differences and safety

issues.

Certain probiotics have demonstrated beneficial

effects. For example, a combination of Lactobacillus and

B. bifidum has exhibited an association with reduced

inflammation, and may have the ability to ameliorate inflammatory

conditions (166). In addition,

Lactobaccillus plantarum has been shown to regulate

oxidative stress, inflammation and gut microbiota dysbiosis in

vivo, while promoting intestinal motility and mucin production

(167). Some of the key effects

and underlying mechanisms of probiotic therapy are summarized in

Table II (168–172). However, the mechanisms by which

different probiotics exert their effects on the human body remain

unclear, highlighting the need for further comprehensive

research.

When considering any treatment, safety is a

priority for pediatric populations. The comprehensive reporting of

all adverse events, particularly long-term safety outcomes, is

critical to meaningfully advance the evidence base in this area

(173). A meta-analysis of COPD

performed by Su et al (174) suggested that probiotics can

improve lung function and structure, and reduce inflammation.

However, the experimental results were suggested to have some

limitations, particularly regarding the efficacy and safety of

long-term probiotic use. Li et al (175) conducted a 12-week randomized

controlled trial, which demonstrated that Bifidobacterium

infantis YLGB-1496 exhibited excellent safety and tolerability

in infants and effectively alleviated the gastrointestinal

discomfort associated with respiratory diseases.

Further research is necessary to validate the

long-term efficacy and safety of probiotics, even though a number

of studies have indicated that probiotic therapy is safe (176–178).

The present review first described the development

of gut microbiota in the early stages of life and their critical

role in human health. It then introduced the gut-lung axis as an

important bidirectional communication system, reviewed the

relationship between the gut microbiota and three pediatric

respiratory tract diseases, and concluded with a summary of

probiotic therapies.

The concept of the gut-lung axis is crucial for

understanding respiratory disease. The gut microbiota and human

health interact with each other, but the underlying mechanisms

remain unclear and require further study. The development of a

healthy gut microbiota is strongly associated with respiratory

health and the development of the immune system in children.

Therefore, in-depth investigation of the gut microbiota composition

and function during early childhood may help to predict future

health, prevent diseases and clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Probiotic therapy offers a novel approach for the

prevention and treatment of respiratory diseases. Increasing

evidence suggests that probiotics can be used to relieve symptoms,

reduce disease recurrence and reduce the use of antibiotics.

Reducing antibiotic exposure is important in children, as

antibiotics can lead to dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, leading to

lower host resistance and contributing to the global issue of

antibiotic resistance.

However, the limitations of probiotic treatments

must be acknowledged. Their exact mechanisms remain unclear, and

therapeutic effects may vary. In addition, the roles of probiotic

preparations in the microenvironments of different diseases require

further investigation. The development of more effective composite

probiotic preparations appears to be a promising area of research.

Although studies have shown that probiotic therapy is generally

safe, with no serious side effects or adverse symptoms reported,

safety assessments of probiotic treatments remain limited to

certain populations; therefore, more research on safety is

necessary. Finally, the lack of unified industry or clinical

guidelines for probiotic use remains a barrier. The standardization

of usage methods in daily life and clinical practice will be

essential to expand the prospects for probiotic treatments in

pediatric respiratory care.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

MZ and YH reviewed the literature and wrote the

manuscript. YJ and LC conceived and designed the study. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease

Collaborators, . Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence,

disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: A

systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015.

Lancet Respir Med. 5:691–706. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

World Health Organization (WHO), . Global

Health Estimates 2016: Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by

region, 2000–2016. WHO; Geneva: 2018

|

|

3

|

Ogal M, Johnston SL, Klein P and Schoop R:

Echinacea reduces antibiotic usage in children through respiratory

tract infection prevention: A randomized, blinded, controlled

clinical trial. Eur J Med Res. 26:332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Aitken M and Taylor JA: Prevalence of

clinical sinusitis in young children followed up by primary care

pediatricians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 152:244–248. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tian J, Wang XY, Zhang LL, Liu MJ, Ai JH,

Feng GS, Zeng YP, Wang R and Xie ZD: Clinical epidemiology and

disease burden of bronchiolitis in hospitalized children in China:

A national cross-sectional study. World J Pediatr. 19:851–863.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chatterjee A, Mavunda K and Krilov LR:

Current state of respiratory syncytial virus disease and

management. Infect Dis Ther. 10 (Suppl 1):S5–S16. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Keulers L, Dehghani A, Knippels L, Garssen

J, Papadopoulos N, Folkerts G, Braber S and van Bergenhenegouwen J:

Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics to prevent or combat air

pollution consequences: The gut-lung axis. Environ Pollut.

302:1190662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Asadi A, Shadab Mehr N, Mohamadi MH,

Shokri F, Heidary M, Sadeghifard N and Khoshnood S: Obesity and

gut-microbiota-brain axis: A narrative review. J Clin Lab Anal.

36:e244202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mancin L, Wu GD and Paoli A: Gut

microbiota-bile acid-skeletal muscle axis. Trends Microbiol.

31:254–269. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ahlawat S and Asha Sharma KK: Gut-organ

axis: A microbial outreach and networking. Lett Appl Microbiol.

72:636–668. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Akshay A, Gasim R, Ali TE, Kumar YS and

Hassan A: Unlocking the gut-cardiac axis: A paradigm shift in

cardiovascular health. Cureus. 15:e510392023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wong CC and Yu J: Gut microbiota in

colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

20:429–452. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang Z, Wang Q, Liu Y, Wang L, Ge Z, Li Z,

Feng S and Wu C: Gut microbiota and hypertension: Association,

mechanisms and treatment. Clin Exp Hypertens. 45:21951352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wilkins AT and Reimer RA: Obesity, early

life gut microbiota, and antibiotics. Microorganisms. 9:4132021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhu W, Wu Y, Liu H, Jiang C and Huo L:

Gut-lung axis: Microbial crosstalk in pediatric respiratory tract

infections. Front Immunol. 12:7412332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Walker AW and Hoyles L: Human microbiome

myths and misconceptions. Nat Microbiol. 8:1392–1396. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Eribo OA, du Plessis N and Chegou NN: The

intestinal commensal, bacteroides fragilis, modulates host

responses to viral infection and therapy: Lessons for exploration

during mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun.

90:e00321212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Alcazar CG, Paes VM, Shao Y, Oesser C,

Miltz A, Lawley TD, Brocklehurst P, Rodger A and Field N: The

association between early-life gut microbiota and childhood

respiratory diseases: A systematic review. Lancet Microbe.

3:e867–e880. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zheng D, Liwinski T and Elinav E:

Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease.

Cell Res. 30:492–506. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

van den Elsen LWJ, Garssen J, Burcelin R

and Verhasselt V: Shaping the gut microbiota by breastfeeding: The

gateway to allergy prevention? Front Pediatr. 7:472019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shao Y, Forster SC, Tsaliki E, Vervier K,

Strang A, Simpson N, Kumar N, Stares MD, Rodger A, Brocklehurst P,

et al: Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization

in caesarean-section birth. Nature. 574:117–121. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Munyaka PM, Khafipour E and Ghia JE:

External influence of early childhood establishment of gut

microbiota and subsequent health implications. Front Pediatr.

2:1092014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras

M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N and Knight R: Delivery mode shapes

the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across

multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:11971–11975. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T,

Henderson N, Jay M, Li H, D Lieber A, Wu F, Perez-Perez GI, Chen Y,

et al: Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome

maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 8:343ra3822016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Rodríguez JM, Murphy K, Stanton C, Ross

RP, Kober OI, Juge N, Avershina E, Rudi K, Narbad A, Jenmalm MC, et

al: The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an

emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Health Dis.

26:260502015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jakobsson HE, Abrahamsson TR, Jenmalm MC,

Harris K, Quince C, Jernberg C, Björkstén B, Engstrand L and

Andersson AF: Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed

Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants

delivered by caesarean section. Gut. 63:559–566. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chu DM, Ma J, Prince AL, Antony KM,

Seferovic MD and Aagaard KM: Maturation of the infant microbiome

community structure and function across multiple body sites and in

relation to mode of delivery. Nat Med. 23:314–326. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fouhy F, Watkins C, Hill CJ, O'Shea CA,

Nagle B, Dempsey EM, O'Toole PW, Ross RP, Ryan CA and Stanton C:

Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after

birth. Nat Commun. 10:15172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Stupak A and Kwaśniewski W: Evaluating

current molecular techniques and evidence in assessing microbiome

in placenta-related health and disorders in pregnancy.

Biomolecules. 13:9112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Le Huërou-Luron I, Blat S and Boudry G:

Breast- v. formula-feeding: Impacts on the digestive tract and

immediate and long-term health effects. Nutr Res Rev. 23:23–36.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Korpela K, Blakstad EW, Moltu SJ, Strømmen

K, Nakstad B, Rønnestad AE, Brække K, Iversen PO, Drevon CA and de

Vos W: Intestinal microbiota development and gestational age in

preterm neonates. Sci Rep. 8:24532018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E,

Turroni F, Mahony J, Belzer C, Delgado Palacio S, Arboleya Montes

S, Mancabelli L, et al: The first microbial colonizers of the human

gut: Composition, activities, and health implications of the infant

gut microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 81:e00036–17. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Arboleya S, Sánchez B, Milani C, Duranti

S, Solís G, Fernández N, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Ventura M,

Margolles A and Gueimonde M: Intestinal microbiota development in

preterm neonates and effect of perinatal antibiotics. J Pediatr.

166:538–544. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Cong X, Xu W, Janton S, Henderson WA,

Matson A, McGrath JM, Maas K and Graf J: Gut microbiome

developmental patterns in early life of preterm infants: Impacts of

feeding and gender. PLoS One. 11:e01527512016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Binns C, Lee M and Low WY: The long-term

public health benefits of breastfeeding. Asia Pac J Public Health.

28:7–14. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Perrella S, Gridneva Z, Lai CT, Stinson L,

George A, Bilston-John S and Geddes D: Human milk composition

promotes optimal infant growth, development and health. Semin

Perinatol. 45:1513802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Berger B, Porta N, Foata F, Grathwohl D,

Delley M, Moine D, Charpagne A, Siegwald L, Descombes P, Alliet P,

et al: Linking human milk oligosaccharides, infant fecal community

types, and later risk to require antibiotics. mBio. 11:e03196–19.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zuurveld M, van Witzenburg NP, Garssen J,

Folkerts G, Stahl B, Van't Land B and Willemsen LEM:

Immunomodulation by human milk oligosaccharides: The potential role

in prevention of allergic diseases. Front Immunol. 11:8012020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bogaert D, van Beveren GJ, de Koff EM,

Lusarreta Parga P, Balcazar Lopez CE, Koppensteiner L, Clerc M,

Hasrat R, Arp K, Chu MLJN, et al: Mother-to-infant microbiota

transmission and infant microbiota development across multiple body

sites. Cell Host Microbe. 31:447–460.e6. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yagi K, Asai N, Huffnagle GB, Lukacs NW

and Fonseca W: Early-life lung and gut microbiota development and

respiratory syncytial virus infection. Front Immunol.

13:8777712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Borewicz K, Suarez-Diez M, Hechler C,

Beijers R, de Weerth C, Arts I, Penders J, Thijs C, Nauta A,

Lindner C, et al: The effect of prebiotic fortified infant formulas

on microbiota composition and dynamics in early life. Sci Rep.

9:24342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhu B, Zheng S, Lin K, Xu X, Lv L, Zhao Z

and Shao J: Effects of infant formula supplemented with prebiotics

and OPO on infancy fecal microbiota: A pilot Randomized clinical

trial. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 11:6504072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ratsika A, Codagnone MC, O'Mahony S,

Stanton C and Cryan JF: Priming for Life: Early life nutrition and

the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Nutrients. 13:4232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ianiro G, Tilg H and Gasbarrini A:

Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: Between good and

evil. Gut. 65:1906–1915. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Dierikx TH, Visser DH, Benninga MA, van

Kaam AHLC, de Boer NKH, de Vries R, van Limbergen J and de Meij

TGJ: The influence of prenatal and intrapartum antibiotics on

intestinal microbiota colonisation in infants: A systematic review.

J Infect. 81:190–204. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Panda S, El khader I, Casellas F, López

Vivancos J, García Cors M, Santiago A, Cuenca S, Guarner F and

Manichanh C: Short-term effect of antibiotics on human gut

microbiota. PLoS One. 9:e954762014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Blaser MJ and Dominguez-Bello MG: The

human microbiome before birth. Cell Host Microbe. 20:558–560. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Azad MB, Konya T, Persaud RR, Guttman DS,

Chari RS, Field CJ, Sears MR, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Subbarao P,

et al: Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics, method of birth

and breastfeeding on gut microbiota during the first year of life:

A prospective cohort study. BJOG. 123:983–993. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hermansson H, Kumar H, Collado MC,

Salminen S, Isolauri E and Rautava S: Breast milk microbiota is

shaped by mode of delivery and intrapartum antibiotic exposure.

Front Nutr. 6:42019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, Haque

R, Mahfuz M, Alam MA, Benezra A, DeStefano J, Meier MF, Muegge BD,

et al: Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished

Bangladeshi children. Nature. 510:417–421. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Blanton LV, Barratt MJ, Charbonneau MR,

Ahmed T and Gordon JI: Childhood undernutrition, the gut

microbiota, and microbiota-directed therapeutics. Science.

352:15332016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kane AV, Dinh DM and Ward HD: Childhood

malnutrition and the intestinal microbiome. Pediatr Res.

77:256–262. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Moles L, Gómez M, Heilig H, Bustos G,

Fuentes S, de Vos W, Fernández L, Rodríguez JM and Jiménez E:

Bacterial diversity in meconium of preterm neonates and evolution

of their fecal microbiota during the first month of life. PLoS One.

8:e669862013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Fernández L, Langa S, Martín V, Maldonado

A, Jiménez E, Martín R and Rodríguez JM: The human milk microbiota:

Origin and potential roles in health and disease. Pharmacol Res.

69:1–10. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Mountzouris KC, McCartney AL and Gibson

GR: Intestinal microflora of human infants and current trends for

its nutritional modulation. Br J Nutr. 87:405–420. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Barrett E, Kerr C, Murphy K, O'Sullivan O,

Ryan CA, Dempsey EM, Murphy BP, O'Toole PW, Cotter PD, Fitzgerald

GF, et al: The individual-specific and diverse nature of the

preterm infant microbiota. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

98:F334–F340. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Fouhy F, Guinane CM, Hussey S, Wall R,

Ryan CA, Dempsey EM, Murphy B, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C

and Cotter PD: High-throughput sequencing reveals the incomplete,

short-term recovery of infant gut microbiota following parenteral

antibiotic treatment with ampicillin and gentamicin. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother. 56:5811–5820. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Fallani M, Young D, Scott J, Norin E,

Amarri S, Adam R, Aguilera M, Khanna S, Gil A, Edwards CA, et al:

Intestinal microbiota of 6-week-old infants across Europe:

Geographic influence beyond delivery mode, breast-feeding, and

antibiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 51:77–84. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DL, Cooper

MA, Morrison M, Hugenholtz P and Hansbro PM: Emerging pathogenic

links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol.

15:55–63. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Espírito Santo C, Caseiro C, Martins MJ,

Monteiro R and Brandão I: Gut microbiota, in the halfway between

nutrition and lung function. Nutrients. 13:17162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chistiakov DA, Bobryshev YV, Kozarov E,

Sobenin IA and Orekhov AN: Intestinal mucosal tolerance and impact

of gut microbiota to mucosal tolerance. Front Microbiol. 5:7812015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ratajczak W, Rył A, Mizerski A,

Walczakiewicz K, Sipak O and Laszczyńska M: Immunomodulatory

potential of gut microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acids

(SCFAs). Acta Biochim Pol. 66:1–12. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Li M, van Esch BCAM, Wagenaar GTM, Garssen

J, Folkerts G and Henricks PAJ: Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects

of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. Eur J

Pharmacol. 831:52–59. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Lee SH, Yun Y, Kim SJ, Lee EJ, Chang Y,

Ryu S, Shin H, Kim HL, Kim HN and Lee JH: Association between

cigarette smoking status and composition of gut microbiota:

Population-based cross-sectional study. J Clin Med. 7:2822018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Bowerman KL, Rehman SF, Vaughan A, Lachner

N, Budden KF, Kim RY, Wood DLA, Gellatly SL, Shukla SD, Wood LG, et

al: Disease-associated gut microbiome and metabolome changes in

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Commun.

11:58862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Gray J, Oehrle K, Worthen G, Alenghat T,

Whitsett J and Deshmukh H: Intestinal commensal bacteria mediate

lung mucosal immunity and promote resistance of newborn mice to

infection. Sci Transl Med. 9:eaaf94122017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP,

Richter J, Franke A, Glickman JN, Siebert R, Baron RM, Kasper DL

and Blumberg RS: Microbial exposure during early life has

persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science.

336:489–493. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Brown RL, Sequeira RP and Clarke TB: The

microbiota protects against respiratory infection via GM-CSF

signaling. Nat Commun. 8:15122017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Luoto R, Ruuskanen O, Waris M, Kalliomäki

M, Salminen S and Isolauri E: Prebiotic and probiotic

supplementation prevents rhinovirus infections in preterm infants:

a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

133:405–413. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Maldonado J, Cañabate F, Sempere L, Vela

F, Sánchez AR, Narbona E, López-Huertas E, Geerlings A, Valero AD,

Olivares M and Lara-Villoslada F: Human milk probiotic

Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 reduces the incidence of

gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infections in infants.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 54:55–61. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wang Y, Li X, Ge T, Xiao Y, Liao Y, Cui Y,

Zhang Y, Ho W, Yu G and Zhang T: Probiotics for prevention and

treatment of respiratory tract infections in children: A systematic

review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine

(Baltimore). 95:e45092016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Redd WD, Zhou JC, Hathorn KE, McCarty TR,

Bazarbashi AN, Thompson CC, Shen L and Chan WW: Prevalence and

characteristics of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in the

United States: A multicenter cohort study. Gastroenterology.

159:765–767.e2. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, Yeoh YK, Li AYL,

Zhan H, Wan Y, Chung ACK, Cheung CP, Chen N, et al: Alterations in

gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of

hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 159:944–955.e8. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Yeoh YK, Zuo T, Lui GC, Zhang F, Liu Q, Li

AY, Chung AC, Cheung CP, Tso EY, Fung KS, et al: Gut microbiota

composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune

responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 70:698–706. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Liu Y, Ni F, Huang J, Hu Y, Wang J, Wang

X, Du X and Jiang H: PPAR-α inhibits DHEA-induced ferroptosis in

granulosa cells through upregulation of FADS2. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 715:1500052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Mazur NI, Higgins D, Nunes MC, Melero JA,

Langedijk AC, Horsley N, Buchholz UJ, Openshaw PJ, McLellan JS,

Englund JA, et al: The respiratory syncytial virus vaccine

landscape: Lessons from the graveyard and promising candidates.

Lancet Infect Dis. 18:e295–e311. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Janet S, Broad J and Snape MD: Respiratory

syncytial virus seasonality and its implications on prevention

strategies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 14:234–244. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Russell CD, Unger SA, Walton M and

Schwarze J: The human immune response to respiratory syncytial

virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 30:481–502. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Bénet T, Sánchez Picot V, Messaoudi M,

Chou M, Eap T, Wang J, Shen K, Pape JW, Rouzier V, Awasthi S, et

al: Microorganisms associated with pneumonia in children <5

years of age in developing and emerging countries: The GABRIEL

pneumonia multicenter, prospective, case-control study. Clin Infect

Dis. 65:604–612. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child

Health (PERCH) Study Group, : Causes of severe pneumonia requiring

hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa

and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet.

394:757–779. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S,

Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et

al: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20

age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global

Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 380:2095–2128. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Harding JN, Siefker D, Vu L, You D,

DeVincenzo J, Pierre JF and Cormier SA: Altered gut microbiota in

infants is associated with respiratory syncytial virus disease

severity. BMC Microbiol. 20:1402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Jang MJ, Kim YJ, Hong S, Na J, Hwang JH,

Shin SM and Ahn YM: Positive association of breastfeeding on

respiratory syncytial virus infection in hospitalized infants: A

multicenter retrospective study. Clin Exp Pediatr. 63:135–140.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Hasegawa K, Linnemann RW, Mansbach JM,

Ajami NJ, Espinola JA, Petrosino JF, Piedra PA, Stevenson MD,

Sullivan AF, Thompson AD and Camargo CA Jr: The fecal microbiota

profile and bronchiolitis in infants. Pediatrics.

138:e201602182016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Nishimura T, Suzue J and Kaji H:

Breastfeeding reduces the severity of respiratory syncytial virus

infection among young infants: A multi-center prospective study.

Pediatr Int. 51:812–816. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Kristensen K, Fisker N, Haerskjold A, Ravn

H, Simões EA and Stensballe L: Caesarean section and

hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection: A

population-based study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 34:145–148. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Lee HC, Headley MB, Loo YM, Berlin A, Gale

M Jr, Debley JS, Lukacs NW and Ziegler SF: Thymic stromal

lymphopoietin is induced by respiratory syncytial virus-infected

airway epithelial cells and promotes a type 2 response to

infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 130:1187–1196.e1185. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Ptaschinski C, Mukherjee S, Moore ML,

Albert M, Helin K, Kunkel SL and Lukacs NW: RSV–Induced H3K4

demethylase KDM5B leads to regulation of dendritic cell-derived

innate cytokines and exacerbates pathogenesis in vivo. PLoS Pathog.

11:e10049782015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Lu S, Hartert TV, Everard ML, Giezek H,

Nelsen L, Mehta A, Patel H, Knorr B and Reiss TF: Predictors of

asthma following severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

bronchiolitis in early childhood. Pediatr Pulmonol. 51:1382–1392.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Malinczak CA, Fonseca W, Rasky AJ,

Ptaschinski C, Morris S, Ziegler SF and Lukacs NW: Sex-associated

TSLP-induced immune alterations following early-life RSV infection

leads to enhanced allergic disease. Mucosal Immunol. 12:969–979.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Yagi K, Lukacs NW, Huffnagle GB, Kato H

and Asai N: Respiratory and gut microbiome modification during

respiratory syncytial virus infection: A systematic review.

Viruses. 16:2202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Fonseca W, Malinczak CA, Fujimura K, Li D,

McCauley K, Li J, Best SKK, Zhu D, Rasky AJ, Johnson CC, et al:

Maternal gut microbiome regulates immunity to RSV infection in

offspring. J Exp Med. 218:e202102352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Ballarini S, Ardusso L, Ortega Martell JA,

Sacco O, Feleszko W and Rossi GA: Can bacterial lysates be useful

in prevention of viral respiratory infections in childhood? The

results of experimental OM-85 studies. Front Pediatr.

10:10510792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE), . Asthma: Diagnosis, monitoring and chronic

asthma management. NICE Guideline, No. 80. NICE; London: 2021

|

|

95

|

Asher MI, Rutter CE, Bissell K, Chiang CY,

El Sony A, Ellwood E, Ellwood P, García-Marcos L, Marks GB, Morales

E, et al: Worldwide trends in the burden of asthma symptoms in

school-aged children: Global asthma network phase I cross-sectional

study. Lancet. 398:1569–1580. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Fainardi V, Esposito S, Chetta A and Pisi

G: Asthma phenotypes and endotypes in childhood. Minerva Med.

113:94–105. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Martinez FD and Vercelli D: Asthma.

Lancet. 382:1360–1372. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Ntontsi P, Photiades A, Zervas E, Xanthou

G and Samitas K: Genetics and epigenetics in asthma. Int J Mol Sci.

22:24122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Stokholm J, Blaser MJ, Thorsen J,

Rasmussen MA, Waage J, Vinding RK, Schoos AM, Kunøe A, Fink NR,

Chawes BL, et al: Maturation of the gut microbiome and risk of

asthma in childhood. Nat Commun. 9:1412018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Fujimura KE, Sitarik AR, Havstad S, Lin

DL, Levan S, Fadrosh D, Panzer AR, LaMere B, Rackaityte E, Lukacs

NW, et al: Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood

multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat Med.

22:1187–1191. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Abreo A, Gebretsadik T, Stone CA and

Hartert TV: The impact of modifiable risk factor reduction on

childhood asthma development. Clin Transl Med. 7:152018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Rosas-Salazar C, Shilts MH, Tang ZZ, Hong

Q, Turi KN, Snyder BM, Wiggins DA, Lynch CE, Gebretsadik T, Peebles

RS Jr, et al: Exclusive breast-feeding, the early-life microbiome

and immune response, and common childhood respiratory illnesses. J

Allergy Clin Immunol. 150:612–621. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Saeed NK, Al-Beltagi M, Bediwy AS,

El-Sawaf Y and Toema O: Gut microbiota in various childhood

disorders: Implication and indications. World J Gastroenterol.

28:1875–1901. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Patrick DM, Sbihi H, Dai DLY, Al Mamun A,

Rasali D, Rose C, Marra F, Boutin RCT, Petersen C, Stiemsma LT, et

al: Decreasing antibiotic use, the gut microbiota, and asthma

incidence in children: Evidence from population-based and

prospective cohort studies. Lancet Respir Med. 8:1094–1105. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Kloepfer KM and Kennedy JL: Childhood

respiratory viral infections and the microbiome. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 152:827–834. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL and

Blumberg RS: How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes

the immune system. Science. 352:539–544. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Renz H and Skevaki C: Early life microbial

exposures and allergy risks: Opportunities for prevention. Nat Rev

Immunol. 21:177–191. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Fahy JV and Dickey BF: Airway mucus

function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 363:2233–2247. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Scotet V, L'Hostis C and Férec C: The

changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis: Incidence, Survival and

impact of the CFTR gene discovery. Genes (Basel). 11:5892020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Elborn JS: Cystic fibrosis. Lancet.

388:2519–2531. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Rafeeq MM and Murad HAS: Cystic fibrosis:

Current therapeutic targets and future approaches. J Transl Med.

15:842017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Bassis CM, Erb-Downward JR, Dickson RP,

Freeman CM, Schmidt TM, Young VB, Beck JM, Curtis JL and Huffnagle

GB: Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the

source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals.

mBio. 6:e000372015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Rogers GB, Carroll MP, Hoffman LR, Walker

AW, Fine DA and Bruce KD: Comparing the microbiota of the cystic

fibrosis lung and human gut. Gut Microbes. 1:85–93. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Dayama G, Priya S, Niccum DE, Khoruts A

and Blekhman R: Interactions between the gut microbiome and host

gene regulation in cystic fibrosis. Genome Med. 12:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Kristensen M, Prevaes SMPJ, Kalkman G,

Tramper-Stranders GA, Hasrat R, de Winter-de Groot KM, Janssens HM,

Tiddens HA, van Westreenen M, Sanders EAM, et al: Development of

the gut microbiota in early life: The impact of cystic fibrosis and

antibiotic treatment. J Cyst Fibros. 19:553–561. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Vernocchi P, Del Chierico F, Russo A, Majo

F, Rossitto M, Valerio M, Casadei L, La Storia A, De Filippis F,

Rizzo C, et al: Gut microbiota signatures in cystic fibrosis: Loss

of host CFTR function drives the microbiota enterophenotype. PLoS

One. 13:e02081712018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Burke DG, Fouhy F, Harrison MJ, Rea MC,

Cotter PD, O'Sullivan O, Stanton C, Hill C, Shanahan F, Plant BJ

and Ross RP: The altered gut microbiota in adults with cystic

fibrosis. BMC Microbiol. 17:582017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Miragoli F, Federici S, Ferrari S, Minuti

A, Rebecchi A, Bruzzese E, Buccigrossi V, Guarino A and Callegari

ML: Impact of cystic fibrosis disease on archaea and bacteria

composition of gut microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 93:fiw2302017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

de Freitas MB, Moreira EAM, Tomio C,

Moreno YMF, Daltoe FP, Barbosa E, Ludwig Neto N, Buccigrossi V and

Guarino A: Altered intestinal microbiota composition, antibiotic

therapy and intestinal inflammation in children and adolescents

with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 13:e01984572018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Matamouros S, Hayden HS, Hager KR,

Brittnacher MJ, Lachance K, Weiss EJ, Pope CE, Imhaus AF, McNally

CP, Borenstein E, et al: Adaptation of commensal proliferating

Escherichia coli to the intestinal tract of young children with

cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:1605–1610. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Nielsen S, Needham B, Leach ST, Day AS,

Jaffe A, Thomas T and Ooi CY: Disrupted progression of the

intestinal microbiota with age in children with cystic fibrosis.

Sci Rep. 6:248572016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Coffey MJ, Nielsen S, Wemheuer B, Kaakoush

NO, Garg M, Needham B, Pickford R, Jaffe A, Thomas T and Ooi CY:

Gut microbiota in children with cystic fibrosis: A taxonomic and

functional dysbiosis. Sci Rep. 9:185932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Manor O, Levy R, Pope CE, Hayden HS,

Brittnacher MJ, Carr R, Radey MC, Hager KR, Heltshe SL, Ramsey BW,

et al: Metagenomic evidence for taxonomic dysbiosis and functional

imbalance in the gastrointestinal tracts of children with cystic

fibrosis. Sci Rep. 6:224932016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Wang Y, Leong LEX, Keating RL, Kanno T,

Abell GCJ, Mobegi FM, Choo JM, Wesselingh SL, Mason AJ, Burr LD and

Rogers GB: Opportunistic bacteria confer the ability to ferment

prebiotic starch in the adult cystic fibrosis gut. Gut Microbes.

10:367–381. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Vaezi A, Healy T, Ebrahimi G, Rezvankhah

S, Hashemi Shahraki A and Mirsaeidi M: Phage therapy: breathing new

tactics into lower respiratory tract infection treatments. Eur

Respir Rev. 33:2400292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Hong Y and Luo T: The potential protective

effects of probiotics, prebiotics, or yogurt on chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease: Results from NHANES 2007–2012. Food Sci Nutr.

12:7233–7241. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Depoorter L and Vandenplas Y: Probiotics

in pediatrics. A review and practical guide. Nutrients.

13:21762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Zhang Y, Xu Y, Hu L and Wang X:

Advancements related to probiotics for preventing and treating

recurrent respiratory tract infections in children. Front Pediatr.

13:15086132025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

O'Donnell A, Murray A, Nguyen A, Salmon T,

Taylor S, Morton JP and Close GL: Nutrition and golf performance: A

systematic scoping review. Sports Med. 54:3081–3095. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Wang Q, Lin X, Xiang X, Liu W, Fang Y,

Chen H, Tang F, Guo H, Chen D, Hu X, et al: Oropharyngeal probiotic

ENT-K12 prevents respiratory tract infections among frontline

medical staff fighting against COVID-19: A pilot study. Front

Bioeng Biotechnol. 9:6461842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Samuelson DR, Charles TP, de la Rua NM,

Taylor CM, Blanchard EE, Luo M, Shellito JE and Welsh DA: Analysis

of the intestinal microbial community and inferred functional

capacities during the host response to Pneumocystis pneumonia. Exp

Lung Res. 42:425–439. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Dong Y, Li M and Yue X: Current research

on probiotics and fermented products. Foods. 13:14062024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Mazziotta C, Tognon M, Martini F,

Torreggiani E and Rotondo JC: Probiotics mechanism of action on

immune cells and beneficial effects on human health. Cells.

12:1842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Suissa R, Oved R, Jankelowitz G, Turjeman

S, Koren O and Kolodkin-Gal I: Molecular genetics for probiotic

engineering: Dissecting lactic acid bacteria. Trends Microbiol.

30:293–306. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Chiappini E, Santamaria F, Marseglia GL,

Marchisio P, Galli L, Cutrera R, de Martino M, Antonini S,

Becherucci P, Biasci P, et al: Prevention of recurrent respiratory