Introduction

Primary lung cancer is the most common malignancy in

China, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) being the most

prevalent histological type, accounting for 80–85% of all cases

(1). The all-stage combined 5-year

relative survival for lung cancer in China is ~15% (2). The clinical treatment of NSCLC

primarily involves a combination of chemotherapy (platinum-based

doublets such as cisplatin-pemetrexed for non-squamous histology,

cisplatin-gemcitabine or carboplatin-paclitaxel for squamous

disease) and radiotherapy. In recent years, notable advances have

been made in the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC, driven by

research into the molecular mechanisms (3,4).

Targeted therapy has led to more successful outcomes in the

treatment of NSCLC; however, despite the success of targeted

therapies in disease control, for example, EGFR-mutant disease is

treated with osimertinib, ALK-rearranged disease with

alectinib/lorlatinib, ROS1-positive disease with entrectinib, and

RET fusions with selpercatinib, the majority of patients with NSCLC

develop resistance and experience disease progression, highlighting

the persistent challenges in the treatment of NSCLC (5,6). To

more effectively address these issues, ongoing efforts to screen

for anticancer drugs and investigate novel therapeutic approaches

are important in identifying more effective treatment

strategies.

Ferroptosis is a recently discovered form of

iron-dependent non-apoptotic cell death characterized by the

accumulation of iron-dependent lipid peroxides and the loss of

glutathione (GSH) peroxidase 4 activity (7). The Hippo/yes-associated protein

(YAP)/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ)

signaling pathway is a highly conserved protein kinase signaling

pathway that regulates the phosphorylation status and nuclear

localization of the downstream transcriptional coactivators YAP and

TAZ (8,9). The Hippo/YAP/TAZ pathway controls

various cellular processes, including proliferation, apoptosis and

organ morphology. As a key regulator linking ferroptosis and the

tumor microenvironment (TME), the Hippo/YAP/TAZ signaling pathway

influences the biological behavior and susceptibility of tumor

cells to ferroptosis under the regulation of various non-genetic

factors (8,9). Reports have suggested that the human

gut absorbs 1–2 mg iron daily from dietary sources. Iron within

cells is either stored in ferritin or exported into the plasma by

iron transporters. In the presence of hepcidin, divalent iron is

oxidized to ferric iron and binds to transferrin (Tf), which then

associates with Tf receptors (TfRs) on the surface of target cell

membranes, facilitating intracellular iron release and initiating

iron cycling (9–11). When the iron concentration in

tissues increases excessively and exceeds the binding capacity of

Tf, non-Tf-bound iron (NTBI) is formed (9–11).

NTBI, along with some unstable ferrous ions, can easily promote

lipid peroxidation and H2O2 cleavage through

Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions, accelerating the formation of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inducing ferroptosis.

Furthermore, acyl-CoA synthase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4)

connects free polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with acyl-CoA to

form PUFA-CoA, which is then incorporated into phospholipids (PLs)

by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 to generate PUFA-PL

(10,11). The H2O2 and

free iron in the cytoplasm undergo a Fenton reaction, producing

ROS, which, in turn, oxidizes PUFA-PL on the cell membrane, leading

to membrane rupture and ferroptosis (12,13).

Studies have confirmed that ACSL4 is an important regulatory site

in the Hippo/YAP/TAZ signaling pathway that mediates ferroptosis

(12,13). Hence, the Hippo/YAP/TAZ signaling

pathway serves an important role in regulating ferroptosis, and

targeting this pathway may be an important therapeutic strategy for

treating NSCLC.

Schisantherin A (Sch A) is a bioactive lignan

isolated from the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) Schisandra

chinensis that has demonstrated notable pharmacological

effects, such as anti-inflammatory, antitumor, neuroprotective and

liver fibrosis-improving effects (14,15).

Despite its known bioactivity, to the best of our knowledge, the

specific role of Sch A in NSCLC has not yet been reported, making

it an unexplored area with potential for revealing new therapeutic

strategies. Given its diverse pharmacological effects,

investigating Sch A in the context of NSCLC may provide valuable

insights and offer a new option for targeted therapy in lung

cancer, which remains a major clinical challenge.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.

provided the EGFR-mutant HCC827 cell line (human lung

adenocarcinoma origin, harboring the classic EGFR Exon19del

E746-A750 deletion mutation; cat. no. CL-0094) and the EGFR

wild-type A549 cell line (cat. no. CL-0016). These cell lines were

grown in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. HCC827 cells

were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented

with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) and 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone; Cytiva).

A549 cells were grown in Ham's F-12K medium (Procell) supplemented

with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

A total of 3,000 A549 and HCC827 cells/well were

plated into 96-well plates. After overnight incubation, various

concentrations of Sch A (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 and 256

µg/ml; MilliporeSigma) were added to each well, with three

replicates for each concentration. Drug-free medium served as a

blank control for 48 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 10 µl CCK-8 reagent

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was added for

2-h incubation. Next, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm and the

IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 10.0

(Dotmatics).

Inhibitor treatments

The following inhibitors were co-incubated with Sch

A: Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor; HY-16658B; final

concentration: 20 µM); 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) (autophagy inhibitor,

HY-19312; final concentration: 5 mM); Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1)

(necroptosis inhibitor; MCE; HY-15760, 10 µM); Ferrostatin-1

(Fer-1) (ferroptosis inhibitor; MCE; HY-100579, 1 µM); Deferoxamine

(DFO) (iron chelator/ferroptosis inhibitor; HY-B1625; all MCE;

final concentration: 100 µM). Vehicle controls received matching

volumes of DMSO (≤0.1% v/v). Cells (A549 and HCC827) were

pretreated with inhibitors at 37°C for 2 h, and then co-incubated

with 6 µg/ml Sch A in A549 cells and 16 µg/ml Sch A in HCC827 cells

together with the same inhibitors for an additional 24 h at

37°C.

Detection of cell death by flow

cytometry

In 6-well plates, A549 and HCC827 cells were plated

at a density of 5×105 cells/well and were incubated

overnight. The cells were divided into Sch A-treated and control

groups, with A549 cells treated with 6 µg/ml Sch A and HCC827 cells

treated with 16 µg/ml Sch A for 48 h at 37°C. The cells were

collected using EDTA-free trypsin and then washed with 100 µl 1X

binding buffer (Annexin V-PE/7-AAD Apoptosis Kit; E-CK-A216, Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd). A total of 5 µl each of

Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD were used to stain the cells. Following 15

min of staining at room temperature in the dark, the cells in

quadrant 3 were analyzed using a CytoFLEX S flow cytometer (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.) and FlowJo v10 software (BD Biosciences).

Gene-set retrieval and intersection

analysis

Ferroptosis- and NSCLC-associated genes were

retrieved from GeneCards (genecards.org;). Venn diagram were

generated using Venny 2.1 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/), yielding

the overlapping gene set for downstream analyses.

PPI network construction and key node

identification

The overlapping genes were imported into the STRING

database (v11.x; string-db.org) to build the PPI) network. Network

topology (node degree) was used to prioritize key regulators; YAP1

emerged as a highly connected transcription factor within the

network.

Cell cycle detection by flow

cytometry

In 6-well plates, A549 and HCC827 cells were plated

at a density of 5×105 cells/well and incubated overnight

at 37°C. The cells were divided into Sch A-treated and control

groups, with A549 cells treated with 6 µg/ml Sch A and HCC827 cells

treated with 16 µg/ml Sch A for 48 h at 37°C. For 12 h, A549 and

HCC827 cells were harvested and washed once with PBS, adjusted to

1×106 cells/ml, and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol at

4°C for 12 h. Fixed cells were washed with PBS, then incubated with

100 µl RNase A solution (DNA Content Quantitation Assay; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C for 30 min. A

total of 400 µl PI staining solution was added and samples were

incubated for 30 min at 4°C before acquisition (Ex 488 nm). Next,

flow cytometry (CytoFLEX S) was used to assess cell cycle

progression, and FlowJo software was used to analyze the data.

Western blot analysis

A549 and HCC827 cells were seeded in 6-well plates

at a density of 1×106 cells/well, and the cells were

grown for 24 h. After A549 and HCC827 cells were treated with 5,

10, 20, 40 µg/ml Sch A for 48 h at 37°C, they were lysed in RIPA

lysis buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.),

and the supernatant was centrifuged at 11,000 g for 15 min at 4°C

to extract all the cellular protein. With a BCA kit, protein

quantification was carried out (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). After being separated by SDS-PAGE on 12%

gels, 20 µg proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After three washes with 0.1% PBS-Tween

(PBST), the membranes were blocked with 8% skimmed milk for 2 h at

room temperature, after which the primary antibodies were added at

4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were against YAP (cat.

no. 14074; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), ACSL4 (cat.

no. T510198, 1:1,000; Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.),

TfR (T56618; 1:1,000; Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.)

and GAPDH (2118, 1:5,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The

membranes were then incubated with an ActivAb Goat Anti-Rabbit

IgG/HRP (1:4,000 dilution, Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 h following three

PBST washes (5 min each). The blots were subsequently visualized

with ECL western blotting substrate (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for detection. GAPDH served as the internal

reference and ImageJ2 (National Institutes of Health) was used to

evaluate the density of the protein bands.

Detection of intracellular

malondialdehyde (MDA), Fe2+ and GSH levels

After A549 and HCC827 cells were centrifuged at

10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected.

According to the manufacturer's instructions, the total

intracellular levels of MDA, Fe2+ and GSH in 50 µl

supernatant were determined via the MDA Content Assay Kit (cat. no.

BC0025), Ferrous Ion Content Assay Kit (cat. no. BC5415) and

Reduced GSH Content Assay Kit (BC1175; all Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), respectively. The source of all the

assay kits was Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.

Transfection of small interfering RNA

(siRNA)

Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. constructed both

negative control (NC) siRNA (forward: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′;

reverse: 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′) and YAP-targeting siRNA

(si-YAP; forward: 5′-AUGUGAUUUAAGAAGUAUCUC-3′; reverse:

5′-GAGAUACUUCUUAAAUCACAU-3′). In 6-well plates, A549 and HCC827

cells were plated at a density of 1×105 cells/well and

cultured overnight. Transfections were performed with the

siRNA-mate plus transfection kit (GenePharma; cat. no. G04026)

following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 15 pmol siRNA

was mixed with Buffer (8.5 µl) to prepare the siRNA premix (final

~1.5 µM), combined with 3 µl siRNA-mate plus to form complexes, and

added directly to each 24-well (30 nM siRNA in 0.5 ml complete

medium). Cells were incubated with the transfection complexes at

37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 48 h

without changing the medium. Subsequent experiments were performed

immediately.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Using the Total RNA Extraction Kit (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), total RNA was extracted from

each set of cells. A NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure the

concentration and purity of the RNA. For each sample, RT 1 µg total

RNA into cDNA was performed with the HiScript II One Step RT-PCR

Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The mRNA expression levels of

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (ptgs2) and GSH-specific

γ-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (Chac1) were measured via AceQ qPCR

SYBR Green Master Mix (without ROX) (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.),

with GAPDH serving as the internal reference gene. Thermocycling

conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min;

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec and

annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. The 2−ΔΔCq

method was used to determine the relative expression levels of

target genes (16). The primers

are listed in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Primer | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| GAPDH-F |

GGGGAGCCAAAAGGGTCATC |

| GAPDH-R |

TGGTTCACACCCATGACGAA |

| YAP1-F |

ACATTGCAAAAGTGGGTGGC |

| YAP1-R |

TGCGAGGATAAAATCCACCTGA |

| FOXO1-F |

AACCCCAGCCCCAACTTAAA |

| FOXO1-R |

ACCTCAAGGAGAGGCCAACT |

| FOXP1-F |

GGCTTCCCTCTGTGTGTTG |

| FOXP1-R |

ATGGGGAAGGGTTAGGCTGA |

| FOXA2-F |

CAAACAGAGGGCCACACAGA |

| FOXA2-R |

CGAGACCTGGATTTCACCGT |

| FOXN4-F |

GTTCCGCAGATAGCTGGGTT |

| FOXN4-R |

AGCTTTGCTGGGAGAGCATT |

| HIF1A-F |

GTCACTTTGCCAGCTCAAAAGA |

| HIF1A-R |

ACCAACAGGGTAGGCAGAAC |

| RELA-F |

GGCATTGTCCCTGTGCCTAA |

| RELA-R |

GAAGTCCCAGACCAAACCCC |

| STAT3-F |

CAAAACCACCTTGCCTCAGC |

| STAT3-R |

GGCTCAGCTCCTCTCAGAAC |

| CEBPA-F |

GGACCCTCAGCCTTGTTTGT |

| CEBPA-R |

AGACGCGCACATTCACATTG |

| MYC-F |

TGGCTGCTTGTGAGTACAGG |

| MYC-R |

TGAACTGGCTTCTTCCCAGG |

| SP1-F |

ATTGTGGACAAGGGCAGGTC |

| SP1-R |

CAACAGTGGTGTGGACTGGT |

| JUN-F |

TCCTGCCCAGTGTTGTTTGT |

| JUN-R |

GACTTCTCAGTGGGCTGTCC |

| TP53-F |

GGAAATCTCACCCCATCCCA |

| TP53-R |

GCAGATGTGCTTGCAGAATGT |

| NFE2L2-F |

TCCCTGCAGCAAACAAGAGA |

| NFE2L2-R |

AACTAGCCCAAATGGTGTCCT |

| AP-1-F |

TCCTGCCCAGTGTTGTTTGT |

| AP-1-R |

GACTTCTCAGTGGGCTGTCC |

| PPARA-F |

TGACAGAAACACACGCGAGA |

| PPARA-R |

CGCTCTTCTCTGCACATCCT |

| NRF1-F |

TCTCCACGTCTTGCTCAACC |

| NRF1-R |

ATCCATGCTCTGCTACTGGG |

| GATA3 |

TTGCCGTTGAGGGTTTCAGA |

| GATA3 |

GCACGCTGGTAGCTCATACA |

| KLF2-F |

GTCTGGAAACCCACCTGGAG |

| KLF2-R |

TTGGTGGTCATGGTTACCCG |

| RUNX3-F |

CTGTAAGGCCCAAAGTGGGT |

| RUNX3-R |

CAGTTTCCACCCAGCTCCAT |

| BACH1-F |

ACAGGTTGCATGTGGACACT |

| BACH1-R |

TCACCTGAGAATTCACCGTAACA |

| ZEB1-F |

CAACAAGCCTGAACTGCTGTC |

| ZEB1-R |

GCAGGATGACAATGTACCCCA |

FerroOrange staining

After A549 and HCC827 cells were washed with

serum-free medium, 500 µl 1 µM FerroOrange working solution

(MedChemExpress) was added. The cells were then incubated at 37°C

in a 5% CO2 incubator for 30 min. A fluorescence

microscope (Olympus Corporation) was used to measure the

fluorescence intensity.

JC-1 staining

After A549 and HCC827 cells were treated with 6

µg/ml Sch A and HCC827 cells treated with 16 µg/ml Sch A for 48 h

at 37°C, 100 µl JC-1 fluorescence staining solution [mitochondrial

membrane potential (MMP) assay kit with JC-1; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.] was added to each well at 37°C

for 20 min, and the A549 and HCC827 cells were incubated in the

dark for 20 min. Subsequently, the cells were inspected under a

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). Green fluorescence

(excitation, 485 nm; emission, 535 nm; mono JC-1) was used to

identify apoptotic or necrotic cells, whereas red fluorescence

(excitation, 550 nm; emission, 600 nm; poly JC-1) was used to

identify healthy cells.

Xenograft nude mouse tumor model

Following centrifugation and trypsin digestion,

5×1010/l serum-free DMEM (HyClone; Cytiva) was used to

resuspend A549 cells at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C. All BALB/c nude

mice were maintained at 22±2°C, 50±10% relative humidity, under a

12:12-h light/dark cycle, with free access to autoclaved chow and

water. Mice were acclimated for at least 7 days prior to

inoculation. The right axilla of male BALB/c nude mice (n=10; age,

6-weeks; weight, 16–18 g; Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal

Technology Co., Ltd.; Charles River Laboratories, Inc.) was then

aseptically injected with a 0.1-ml aliquot of the cell mixture

(each mouse received an injection of 5×106 A549 cells).

According to relevant studies on lung cancer models (17,18),

sex has a minimal impact on experimental results; therefore, sex

was not considered a variable in the present study. After ~14 days,

the tumor model was considered successfully established once the

maximum tumor diameter was >5 mm or the tumor volume was >50

mm3.

Humane endpoints included maximum tumor diameter ≥15

mm, tumor volume ≥1,500 mm3,

ulceration/necrosis/infection, ≥20% body weight loss, or failure to

eat/drink. No mice reached humane endpoints before planned

termination. The mice with successfully established tumors were

randomly assigned to two groups: A control group and a Sch A

treatment group. During the 14-day treatment period, the Sch A

group of mice were given Sch A orally at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day,

whereas the control group was given an equivalent volume of saline.

Following treatment, the long and short diameters of the xenograft

tumors were measured, and their volumes were computed using the

following formula: Tumor volume=(long diameter × short

diameter2)/2. In the present study, the maximum tumor

diameter observed was 8.2 mm, and the maximum tumor volume was 107

mm3. Isoflurane anesthesia was administered at a

concentration of 4% for induction and 1.5% for maintenance, with an

oxygen flow rate of 1.5 l/min, during subcutaneous tumor cell

injection and tumor measurement procedures. For oral gavage,

anesthesia was not employed, as this procedure is generally

considered minimally invasive and does not typically require

anesthesia. The mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane 1 h after

the final administration and euthanized by decapitation. The tumors

were then removed and weighed for analysis.

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments

guidelines and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

(US National Research Council) (19). All animal experiments were approved

by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Guangzhou

University of Chinese Medicine (Shenzhen, China; approval no.

2024055R).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp.) was used to analyze the

experimental data, and the results are presented as the mean ± SD

of ≥3 independent experimental repeats. Pairwise comparisons were

performed using the unpaired Student's t-test, and group

comparisons were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post hoc analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Concentration- and time-dependent

inhibition of A549 and HCC827 cell viability by Sch A

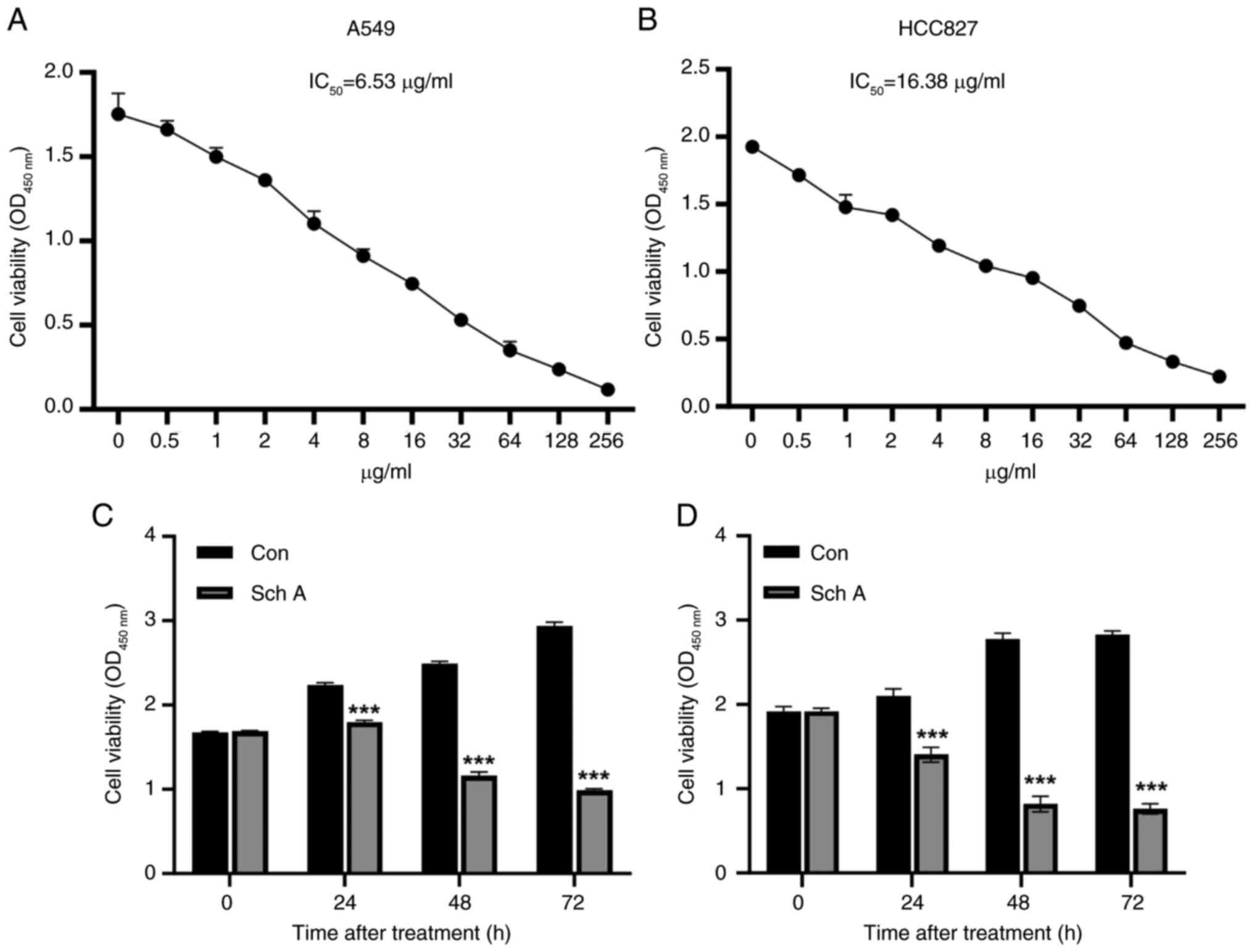

The viability of A549 and HCC827 cells was evaluated

following exposure to a range of Sch A concentrations. The CCK-8

assay revealed a concentration-dependent decrease in viability in

both cell lines (Fig. 1A and B).

The IC50 values of Sch A were determined to be 6.53

µg/ml for A549 cells and 16.38 µg/ml for HCC827 cells. Based on

these results, concentrations of 6 and 16 µg/ml were selected for

subsequent experiments in A549 and HCC827 cells, respectively.

Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of Sch A on the viability of

both cell lines increased significantly with prolonged treatment

(Fig. 1C and D).

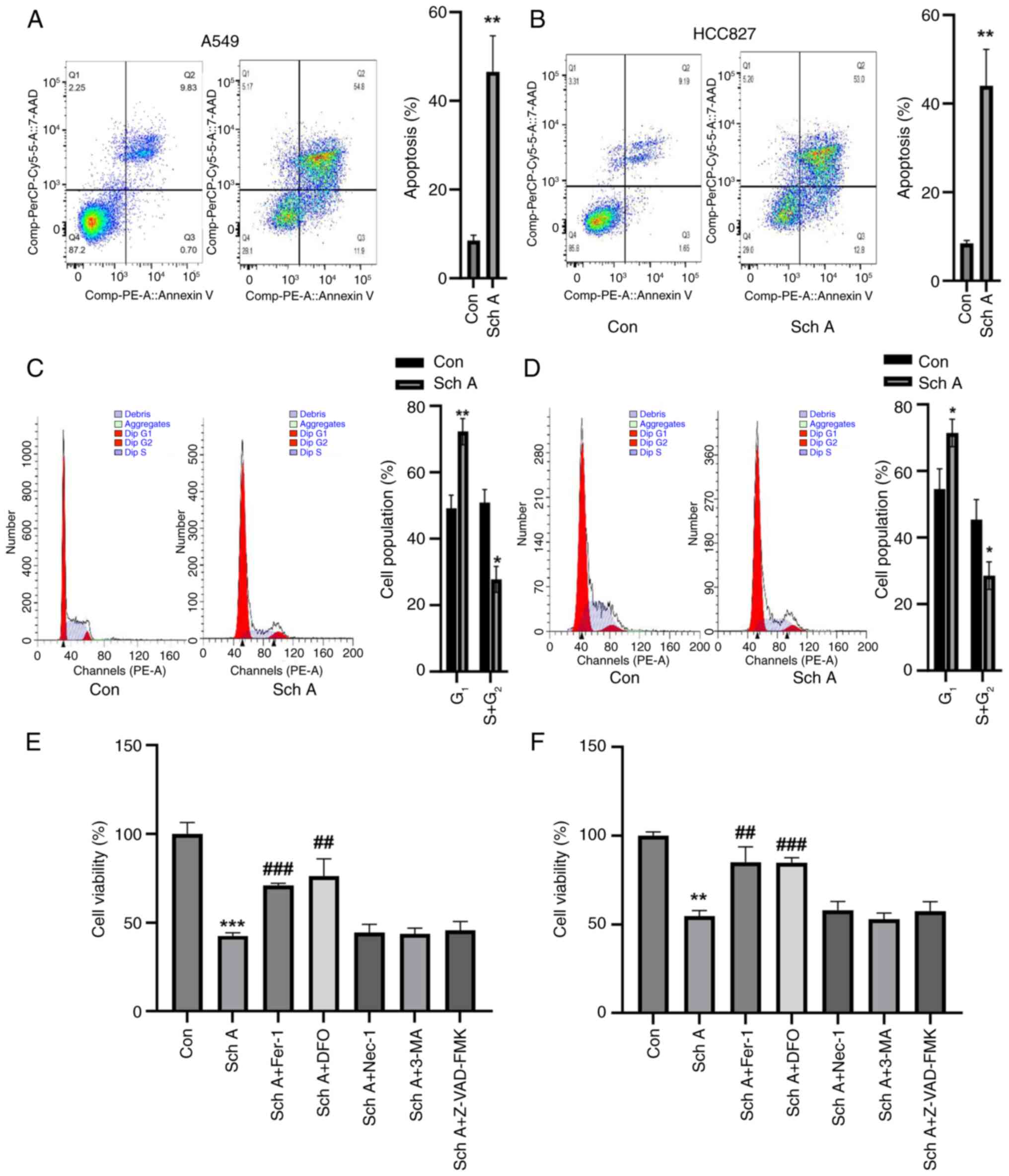

Fer-1 and deferoxamine (DFO) abolish

Sch A-induced lung cancer cell death

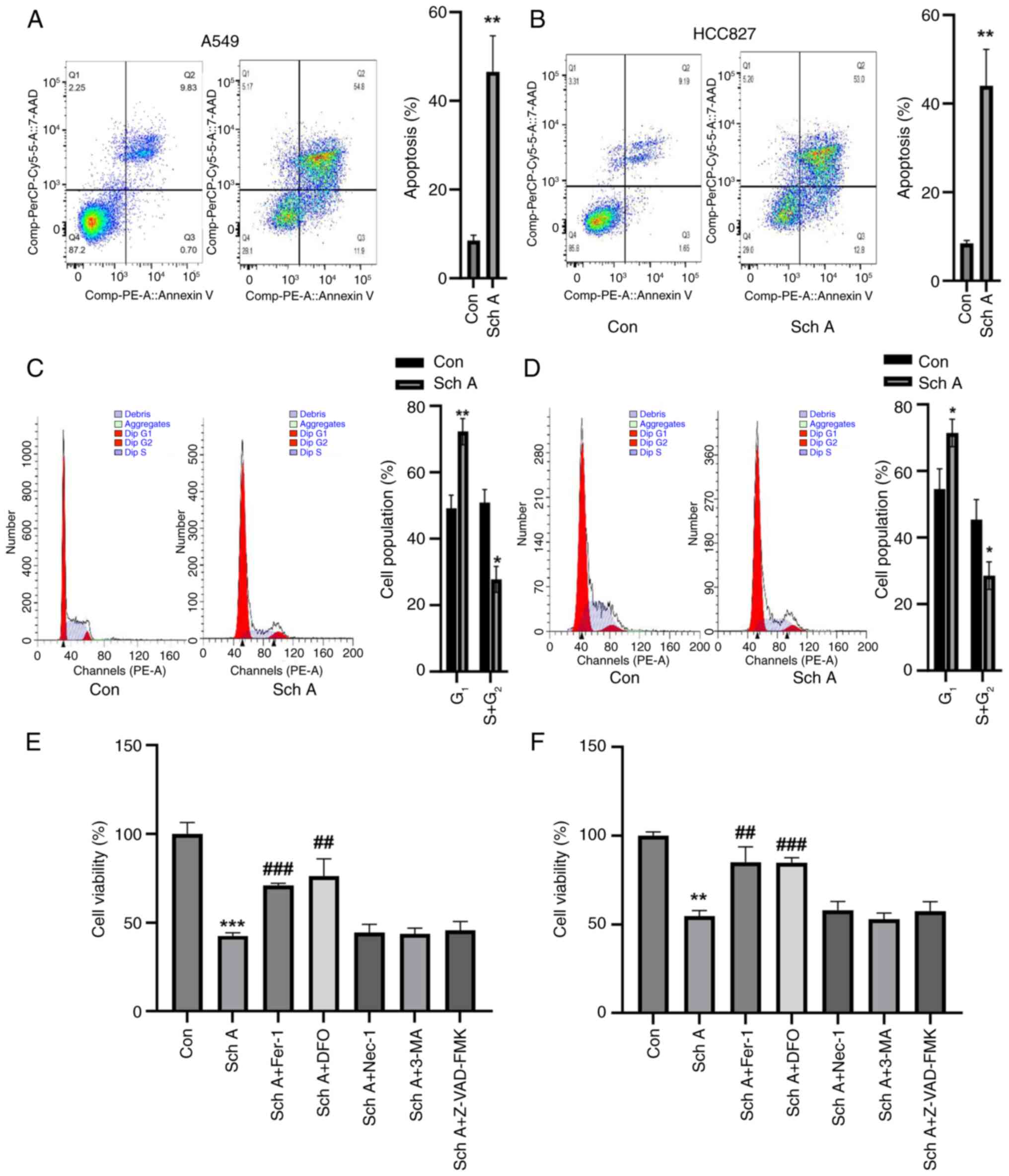

Compared with the control, treatment with Sch A

significantly increased late apoptosis in both A549 and HCC827

cells (Fig. 2A and B).

Additionally, cell cycle analysis revealed a substantial

accumulation of A549 and HCC827 cells in the G1 phase,

accompanied by a notable reduction in the percentage of cells in

the S and G2 phases (Fig.

2C and D). Upon preincubation for 1 h with a range of

inhibitors, including the apoptosis inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, the

autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine, the necrosis inhibitor

necrostatin-1 and the ferroptosis inhibitors Fer-1 and DFO, only

the latter two inhibitors partially reversed the Sch A-induced

reduction in cell viability. By contrast, apoptosis, autophagy and

necrosis inhibitors had no significant effect on Sch A-induced cell

death, highlighting the specific involvement of ferroptosis in this

process (Fig. 2E and F).

| Figure 2.Sch A induces cell death and cell

cycle arrest in A549 and HCC827 cells. Sch A considerably increased

the death of (A) A549 and (B) HCC827 cells in comparison with the

control group, according to flow cytometric analysis. Compared with

Con, (C) A549 and (D) HCC827 cells presented a significant decrease

in the number of G2 + S-phase cells and a significant

increase in the number of G1-phase cells. Fer-1 and DFO

were able to significantly reverse the Sch A-induced decrease in

(E) A549 and (F) HCC827 cell viability, according to the results of

the Cell Counting Kit-8 analysis. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. Con; ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. Sch A. DFO, deferoxamine; Con,

control; Sch A, Schisantherin A; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1; Nec-1,

necrostatin-1; 3-MA, 3-methyladenine. |

Sch A induces ferroptosis in A549 and

HCC827 cells by modulating MMP and lipid peroxidation

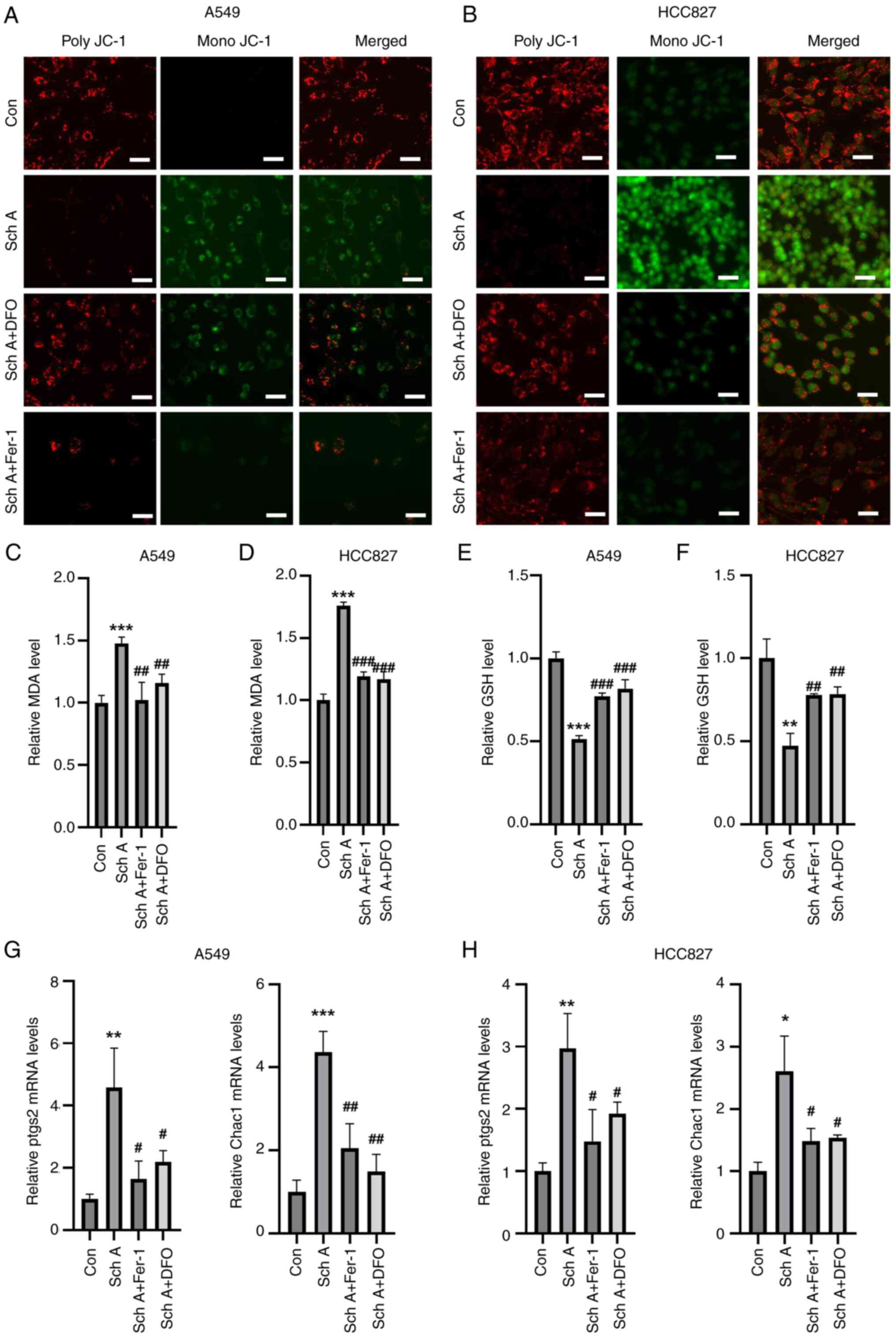

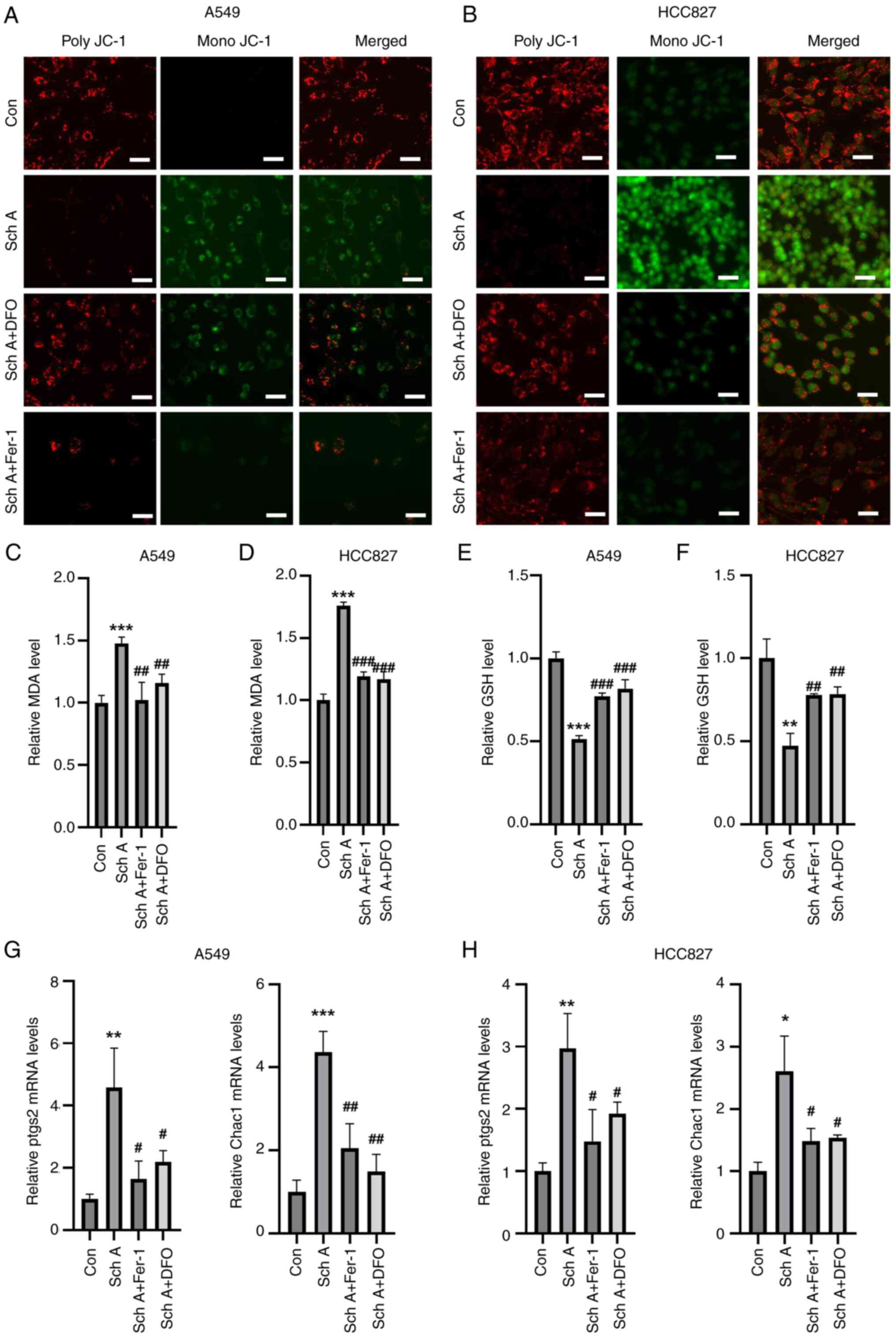

Changes were also observed in the MMP, where Sch A

treatment led to a decrease in JC-1 aggregation and an increase in

monomeric JC-1 levels, indicating a reduction in the MMP compared

with that in the control group (Fig.

3A and B). Preincubation with the ferroptosis inhibitors Fer-1

and DFO resulted in a reduction in monomeric JC-1 levels and an

increase in polymeric JC-1 levels, suggesting the restoration of

the MMP. Furthermore, Sch A treatment led to elevated MDA levels in

both A549 and HCC827 cells, an effect that was reversed by

pre-treatment with Fer-1 and DFO (Fig.

3C and D). Sch A also caused a decrease in GSH levels in both

cell lines, which was reversed by pre-treatment with Fer-1 and DFO

(Fig. 3E and F). Additionally, an

increase in the expression of the ferroptosis markers Chac1 and

ptgs2 was observed following Sch A treatment, with Fer-1 and DFO

effectively reversing the Sch A-induced upregulation of these

markers (Fig. 3G and H).

| Figure 3.In A549 and HCC827 cells, ferroptosis

inhibitors prevent Sch A-induced apoptosis. Fer-1 and DFO were

shown by JC-1 staining to reverse the Sch A-induced MMP reduction

in (A) A549 and (B) HCC827 cells (scale bar, 30 µm). Fer-1 and DFO

inhibited the Sch A-induced increase in MDA in (C) A549 and (D)

HCC827 cells. Fer-1 and DFO counteracted the Sch A-induced

reduction in GSH in (E) A549 and (F) HCC827 cells. Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis revealed that Fer-1 and DFO

reversed the Sch A-induced increase in Chac1 and ptgs2 levels in

(G) A549 and (H) HCC827 cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. Con; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. Sch A. Con,

control; Chac1, glutathione-specific γ-glutamylcyclotransferase 1;

ptgs2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1;

DFO, deferoxamine; Sch A, Schisantherin A; MDA, malondialdehyde;

GSH, glutathione. |

Sch A upregulates YAP1 and modulates

ferroptosis in NSCLC through transcriptional activation of

ferroptosis-related proteins

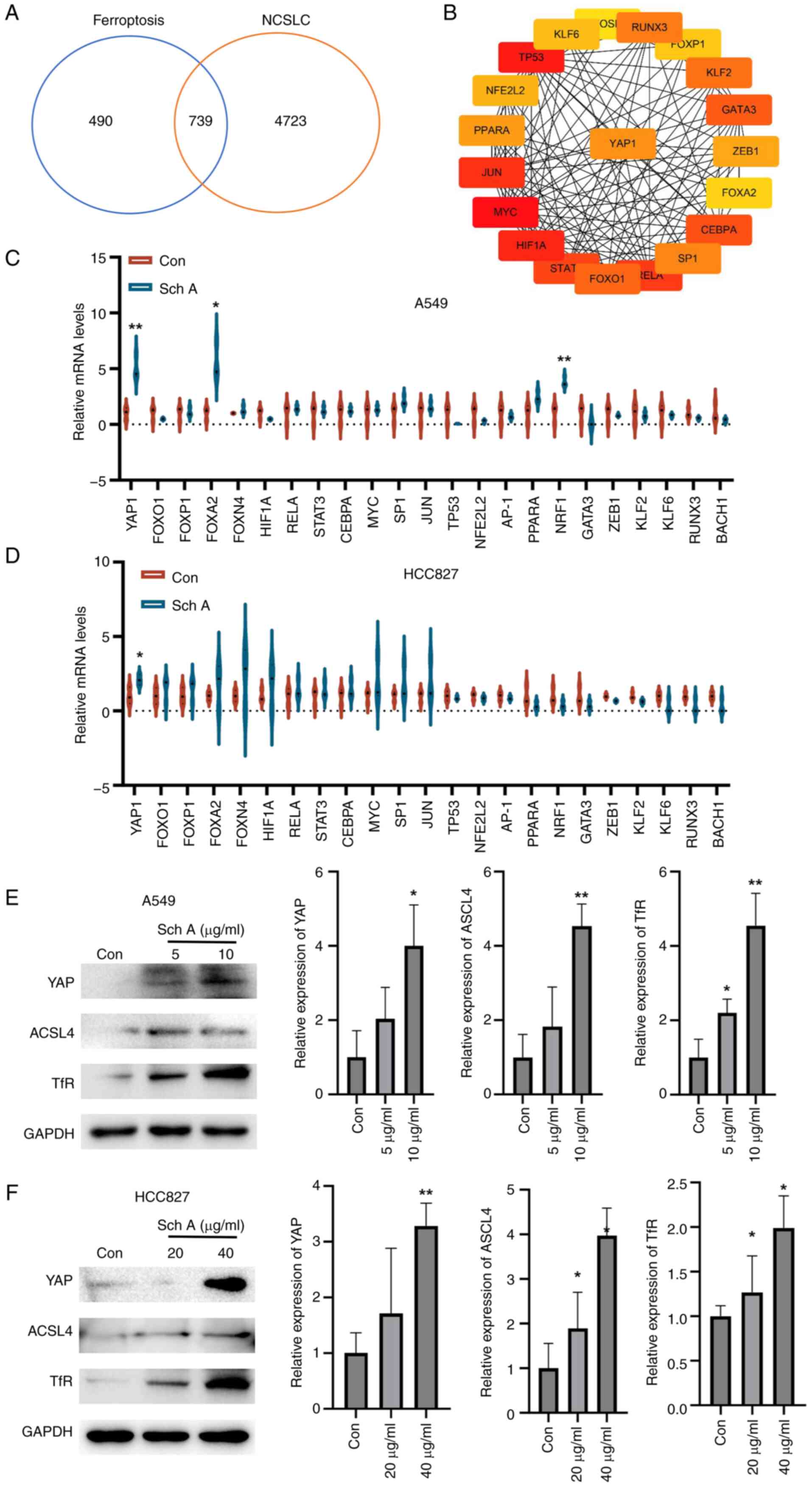

Using GeneCards, an intersection analysis of

ferroptosis-related and NSCLC-associated target genes revealed 739

overlapping genes, suggesting that these genes may serve an

important role in regulating ferroptosis within NSCLC (Fig. 4A). Among these 739 overlapping

genes, transcription factors were further analyzed to identify key

node genes, with YAP emerging as a critical regulator within this

intersecting gene network, highlighting its potential role in

modulating ferroptosis in NSCLC (Fig.

4B). RT-qPCR analysis revealed that Sch A treatment of A549 and

HCC827 cells led to a significant increase in YAP1 mRNA expression,

indicating that Sch A can upregulate YAP1 in NSCLC cell lines

(Fig. 4C and D). Given the

multifaceted role of the Hippo pathway in regulating tumor cell

behavior, the phosphorylation status of YAP, a key downstream

effector of this pathway, was further examined. Although no changes

in YAP phosphorylation levels were observed (data not shown), a

marked increase in YAP protein levels was detected (Fig. 4E and F), suggesting that YAP may

participate in ferroptosis through mechanisms independent of

phosphorylation. To further investigate this finding, it was

hypothesized that YAP might regulate ferroptosis by

transcriptionally activating ferroptosis-related proteins,

specifically TfR and ACSL4. Western blot analysis confirmed the

involvement of YAP in regulating ferroptosis, as Sch A treatment

increased the expression of the ferroptosis-related proteins TfR

and ACSL4.

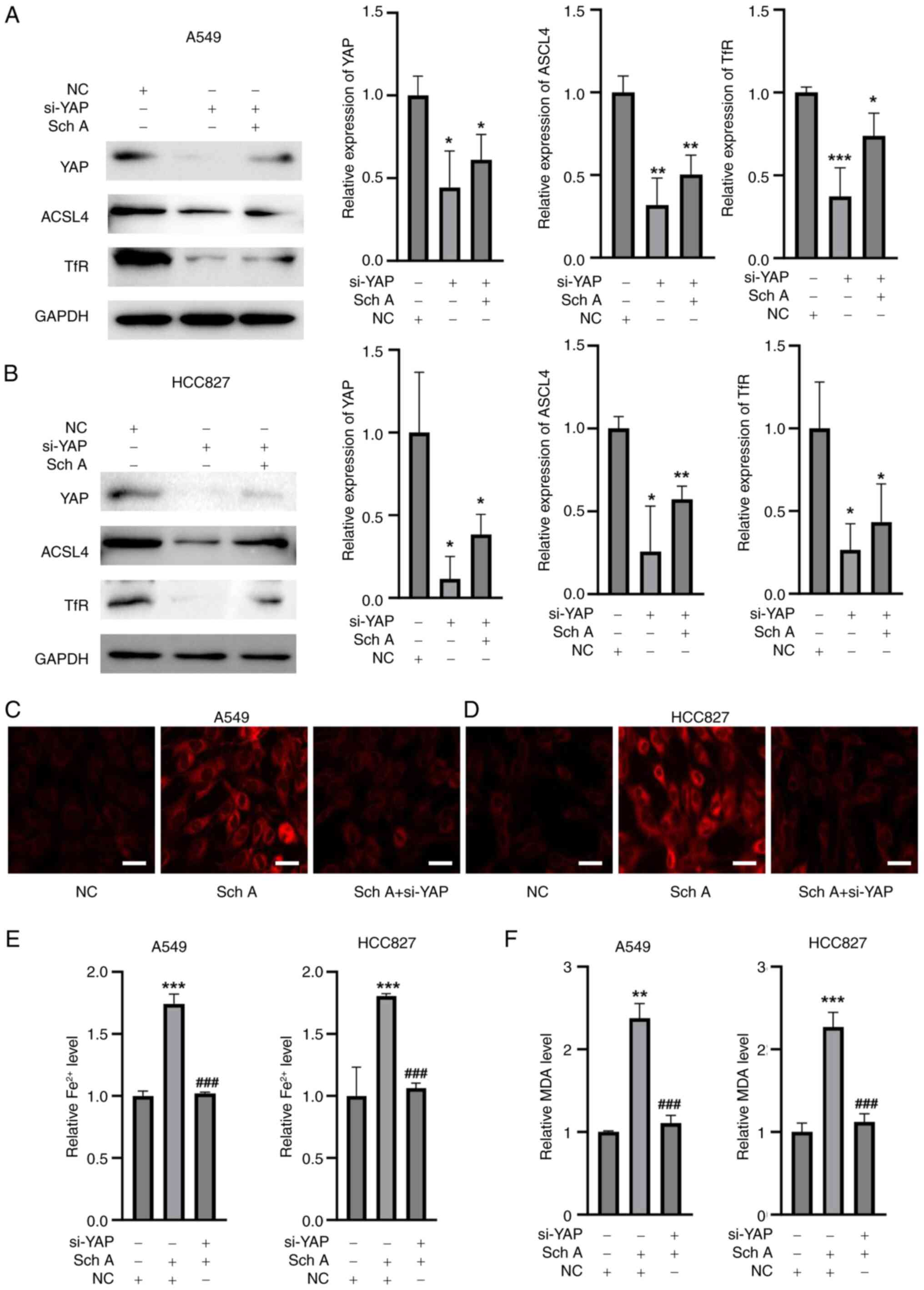

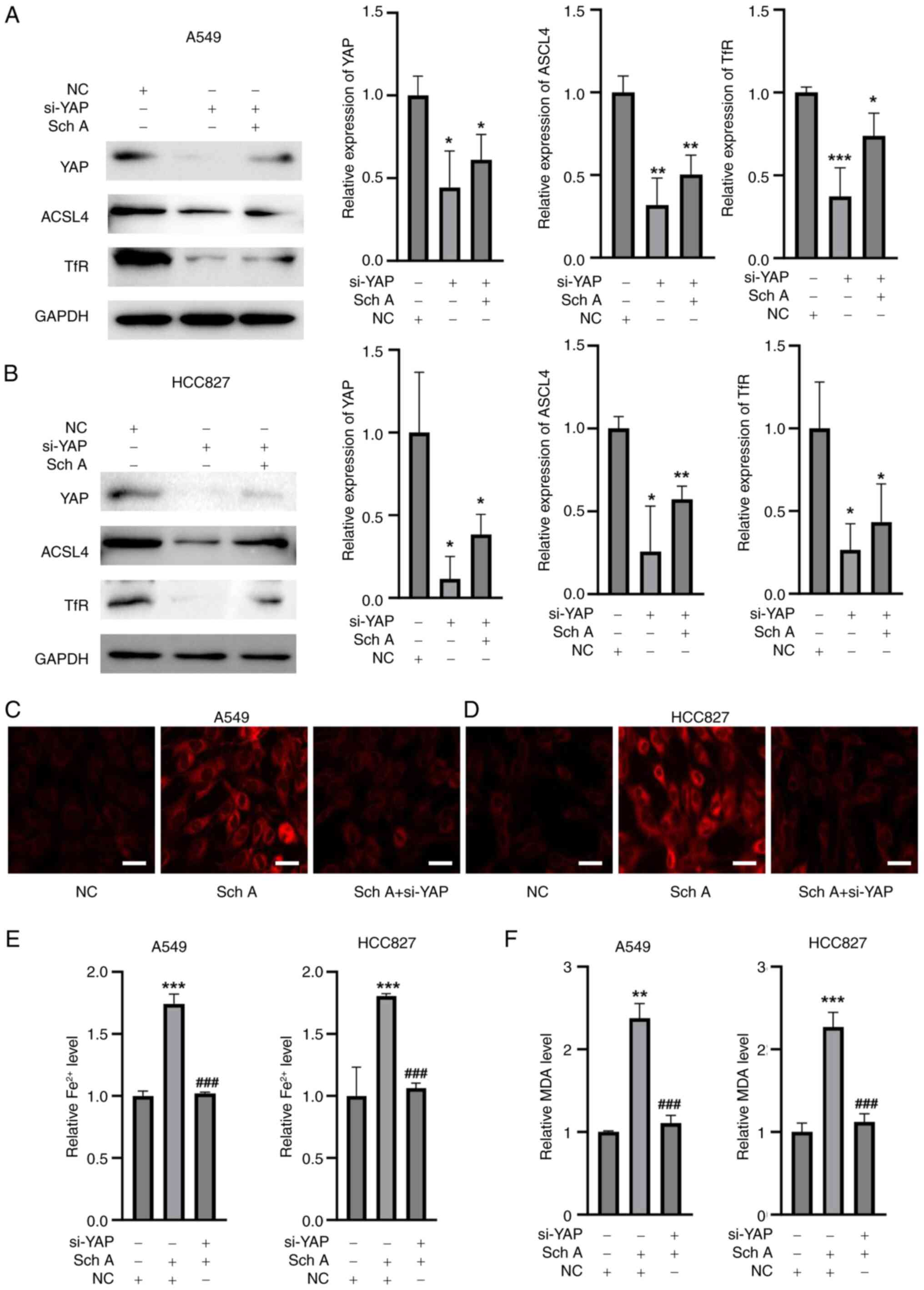

YAP knockdown abolishes Sch A-induced

ferroptosis in lung cancer cells

To determine whether YAP activation has a role in

Sch A-induced ferroptosis, the present study employed siRNAs

targeting YAP. Western blot analysis demonstrated that transfection

with si-YAP resulted in a marked reduction in the protein levels of

YAP in both A549 and HCC827 cell lines when compared with cells

transfected with the NC siRNA (Fig. 5A

and B). The results, presented in Fig. 5A and B, demonstrated a significant

reduction in YAP expression in both A549 and HCC827 cells following

siRNA transfection, indicating efficient knockdown of YAP. Along

with the knockdown of YAP, the downstream targets ACSL4 and TfR

were also significantly suppressed by si-YAP. Following Sch A

treatment conditions, si-YAP was still able to efficiently knock

down YAP expression as well as the downstream targets ACSL4 and TfR

in both cell lines. FerroOrange staining revealed that Sch A

treatment led to notable Fe2+ accumulation in both A549

and HCC827 cells. However, upon YAP silencing, this increase in

Fe2+ was effectively reversed, further indicating that

YAP serves an important role in regulating iron metabolism during

Sch A-induced ferroptosis (Fig. 5C and

D). Additionally, quantification of Fe2+ and MDA

levels in A549 and HCC827 cells revealed that Sch A treatment

significantly elevated both Fe2+ and MDA levels compared

with those in the control group, whereas YAP silencing effectively

alleviated these Sch A-induced increases (Fig. 5E and F).

| Figure 5.Silencing of YAP reverses Sch

A-induced ferroptosis. Western blot analysis showed that the

expression of YAP was decreased in (A) A549 and (B) HCC827 cells.

In (C) A549 and (D) HCC827 cells, si-YAP decreased the expression

of YAP and downstream signaling molecules. Fe2+

accumulation was induced by Sch A in (E) A549 and (F) HCC827 cells,

and the increase in Fe2+ was reversed by YAP silencing,

as demonstrated by FerroOrange staining (scale bar, 10 µm). After

silencing YAP, the Sch A-induced increase in Fe2+ and

MDA in (G) A549 and (H) HCC827 cells was reduced. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. NC; ###P<0.001 vs.

Sch A. NC, negative control; YAP, yes-associated protein; Sch A,

Schisantherin A; si, small interfering RNA; MDA, malondialdehyde;

ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthase long-chain family member 4; TfR,

transferrin receptor. |

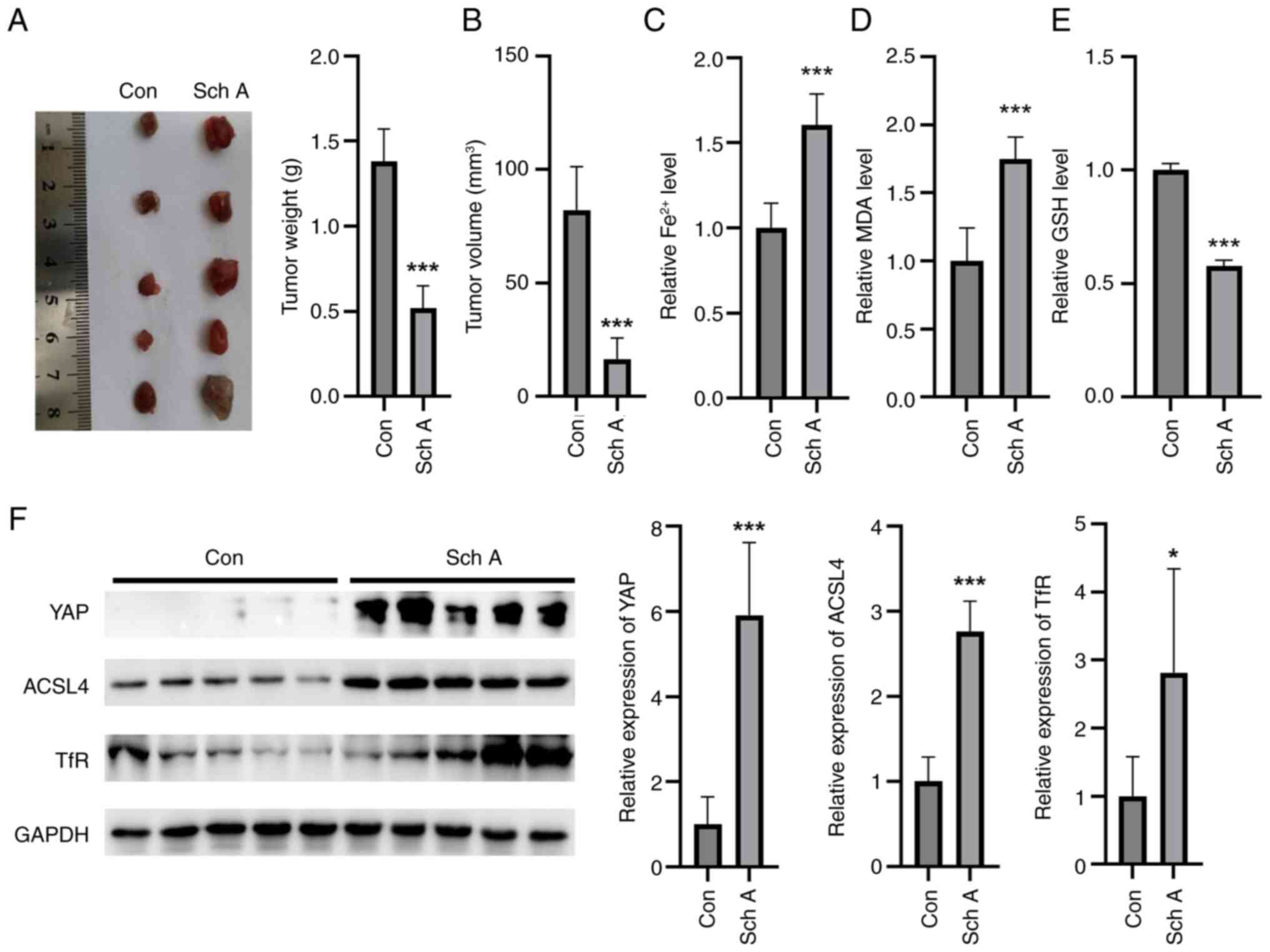

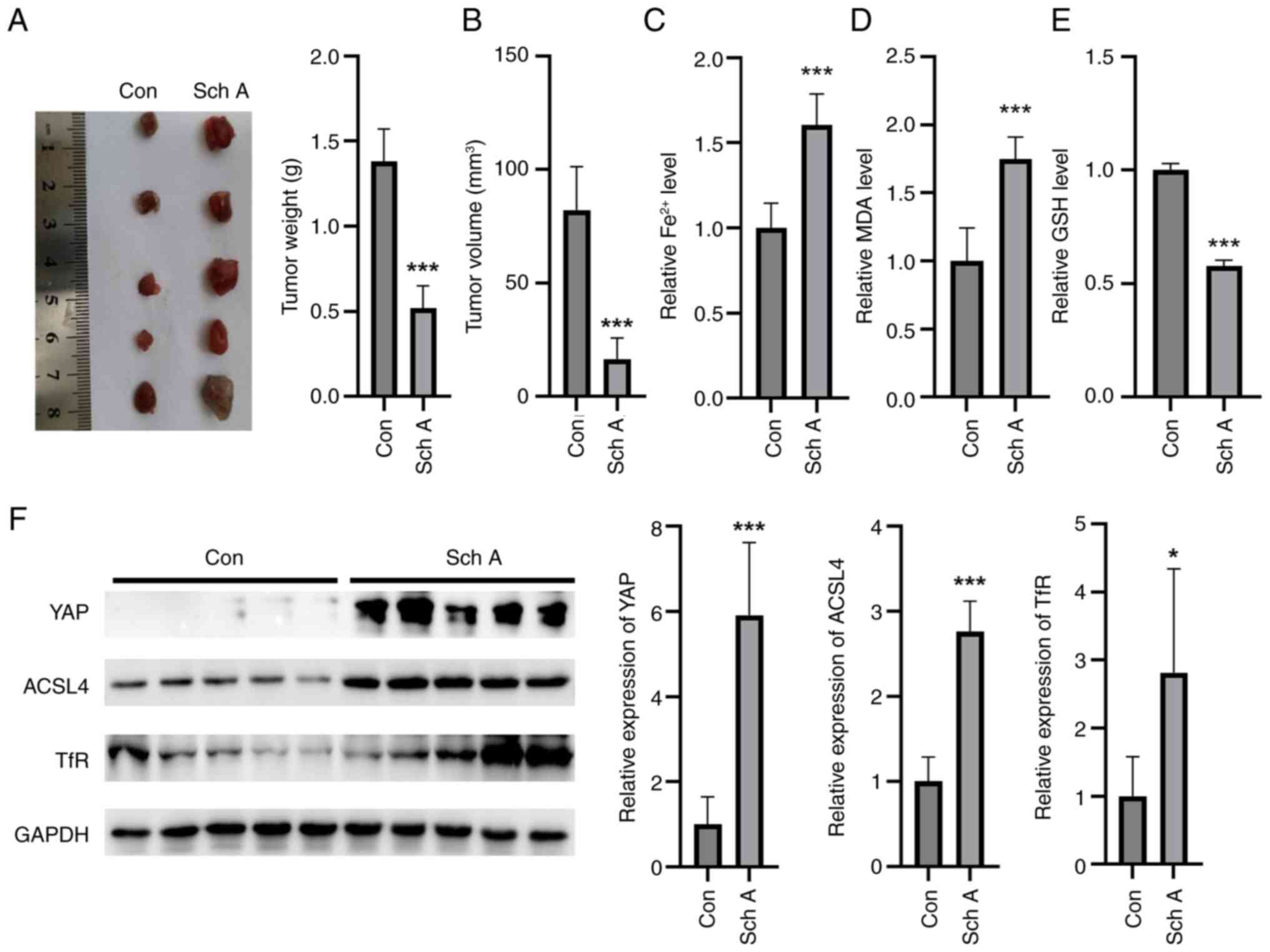

Sch A inhibits tumor growth in nude

mice

To assess the effect of Sch A on tumor growth in

vivo, a nude mouse xenograft model was used. Compared with the

control treatment, Sch A treatment resulted in a significant

reduction in both tumor mass and volume, demonstrating its potent

inhibitory effect on tumor growth in this animal model (Fig. 6A and B). Furthermore, Sch A

treatment led to a marked increase in MDA levels and

Fe2+ accumulation within the tumors, indicating the

promotion of ferroptosis-related oxidative stress and iron overload

in the TME (Fig. 6C and D). This

increase was accompanied by a significant decrease in GSH levels,

suggesting a depletion of antioxidant defenses in the tumor tissues

(Fig. 6E). Additionally, Sch A

treatment upregulated the protein expression levels of YAP, ACSL4

and TfR in tumor tissues, which was consistent with the in

vitro findings, further supporting the involvement of these

proteins in Sch A-induced ferroptosis and tumor suppression

(Fig. 6F).

| Figure 6.In vivo, Sch A prevents the

formation of tumors in nude mice. Compared with Con, Sch A

inhibited (A) tumor mass and (B) volume in vivo in nude

mice. Sch A increased the (C) Fe2+ and (D) MDA contents

in nude mouse tumors. (E) Sch A diminished the GSH levels in the

tumors compared with those in the Con group. (F) Compared with

those in the Con group, Sch A induced the expression levels of YAP,

ACSL4 and TfR in the tumors of nude mice. *P<0.05 and

***P<0.001 vs. Con. Con, control; Sch A, Schisantherin A; MDA,

malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; YAP, yes-associated protein;

ACLS4, acyl-CoA synthase long-chain family member 4; TfR,

transferrin receptor. |

Discussion

Lung cancer poses a notable threat to global human

health and life, with >50% of patients being diagnosed at

advanced stages, leading to a low chance of curative surgery

(20). Currently, chemotherapy and

radiotherapy are the primary treatment methods for lung cancer, but

owing to their pronounced toxic side effects and the tendency for

drug resistance to develop, patients often find it difficult to

adhere to treatment, resulting in low cure rates and high

recurrence rates (20,21). In recent years, TCM has attracted

notable attention from researchers due to its potent therapeutic

effects, low toxicity and multitargeted approach for tumor

treatment (14). Sch A, a major

bioactive lignan isolated from the TCM plant Schisandra

chinensis, has been shown to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma

cell proliferation by suppressing glucose metabolism, thereby

exerting anti-liver cancer effects (22). Additionally, Sch A induces ROS

generation, activates the JNK signaling pathway and inhibits

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, effectively

suppressing gastric cancer cell proliferation and migration, and

promoting apoptosis (23).

However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have

reported the potential anticancer effects of Sch A on NSCLC and its

underlying mechanisms.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study

explored the molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects

of Sch A in NSCLC for the first time. The present results

demonstrated that Sch A effectively inhibited the viability of

NSCLC cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Treatment with

Sch A significantly led to an increase in NSCLC cell apoptosis and

induced cell cycle arrest, highlighting its notable anticancer

activity. Further mechanistic investigations revealed that Sch A

triggered ferroptosis in NSCLC cells, as supported by the reversal

of the Sch A-induced reduction in cell viability and MMP loss upon

treatment with the ferroptosis inhibitors Fer-1 and DFO.

Additionally, Sch A treatment resulted in elevated intracellular

levels of Fe2+ and MDA, alongside a significant decrease

in the content of GSH, a key indicator of ferroptosis activation

(24). Collectively, these

findings provide evidence that Sch A induces ferroptosis in lung

cancer cells, suggesting its potential as a novel therapeutic

strategy for NSCLC.

Xian et al (25) and Zhu et al (26) reported that Sch A can induce

apoptosis in NSCLC by inhibiting EGFR phosphorylation or

synergizing with gefitinib. However, the present study was, to the

best of our knowledge, the first to demonstrate that Sch A

triggered ferroptosis through activation of the YAP/ACSL4/TfR axis,

a cell death mechanism unexplored in prior research. While previous

work, such as the study by Zhu et al (26), focused on apoptosis or, in the case

of the study by Xian et al (25), apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, the

systematic inhibitor screening experiments performed in the present

study established ferroptosis as the predominant cell death

modality under Sch A monotherapy, with the apoptosis inhibitor

Z-VAD-FMK showing no significant effect on Sch A-induced

cytotoxicity. To ensure translational relevance across NSCLC

subtypes, two genetically distinct cell lines were employed, A549

(EGFR-wild type) and HCC827 (EGFR Exon19del E746-A750 mutant),

which are tyrosine kinase inhibitor-sensitive lines frequently used

in targeted-therapy studies (27,28).

The results of the present study demonstrated that Sch A induced

ferroptotic features in both cell lines, suggesting that its

mechanism was not dependent on the EGFR mutation status and may

therefore offer therapeutic potential across a range of NSCLC

genetic backgrounds. Notably, comparable increases in

Fe2+ accumulation, and ACSL4 and TfR expression were

observed in both A549 and HCC827 cells following Sch A treatment,

indicating genotype-independent vulnerability to ferroptosis. The

apparent discrepancy with the apoptotic phenotype described in the

study by Zhu et al (26)

may arise from key methodological differences: i) The

aforementioned study used 50 µM Sch A for 24 h to induce apoptosis,

whereas the present study employed lower concentrations that may

activate distinct cell death pathways; and ii) the study by Zhu

et al (26) quantified

total apoptosis (quadrants 2 + 3) via a FITC-PE kit, whereas the

present study specifically analyzed late apoptosis (quadrant 3) via

an Annexin V-7-AAD kit alongside ferroptosis markers, such as

Fe2+ accumulation. The Annexin V-FITC-PE approach cannot

exclude interference from necrotic or ferroptotic cells in

PI+ populations, which represent membrane-disrupted

cells. By contrast, the Annexin V-7-AAD kit precisely distinguishes

early apoptosis (quadrant 3, Annexin

V+/7-AAD−), late apoptosis (quadrant 2,

Annexin V+/7-AAD+) and primary necrosis

(quadrant 1, Annexin V−/7-AAD+). The present

study observed a significant Sch A-induced increase in

7-AAD+ cells in quadrant 2 (late apoptosis/secondary

necrosis), which co-occurred with ferroptosis biomarkers. Combined

with specific rescue by the ferroptosis inhibitors Fer-1 and DFO,

the present study concluded that ferroptosis, not classical

apoptosis, was the primary death mechanism. The present study

explored the anticancer mechanism of Sch A in NSCLC, which shifted

the paradigm from apoptosis to YAP-dependent ferroptosis. Hence,

the present study investigated a novel signaling axis with broad

therapeutic implications, advancing the potential of Sch A as a

precision oncology agent.

Furthermore, emerging evidence links EGFR signaling

to ferroptosis regulation (29,30).

In colorectal cancer, glucose deprivation inhibits Hippo signaling

and activates EGFR, which enhances cell anti-ferroptotic defenses

through PPAR-ACSL1/4 lipid-metabolic remodeling, thereby limiting

lipid peroxidation (29). In

triple-negative breast cancer, EGFR inhibition promotes ferroptosis

via YAP/mTOR-mediated autophagy (30). In the NSCLC models of the present

study, Sch A-induced YAP activation led to the upregulation of

ACSL4 and TfR, which are hallmark mediators of ferroptosis, in both

EGFR-mutant (HCC827) and -wild-type (A549) cells, indicating

YAP-driven ferroptosis across distinct EGFR backgrounds. This

cascade may have been modulated by the tissue context and EGFR

mutational status but ultimately converged on a shared ferroptotic

axis. In summary, the present study provided new mechanistic

insight into the anti-NSCLC potential of Sch A. By demonstrating

consistent ferroptosis induction across both EGFR-wild-type and

mutant backgrounds, the present study highlighted the promise of

Sch A as a mutation-agnostic therapeutic.

While traditional molecular research has revealed

that Sch A induced ferroptosis in NSCLC cells via the YAP/ACSL4/TfR

axis, this perspective alone may not have fully accounted for

complex clinical phenomena such as drug resistance and tumor

recurrence. By adopting the cancer ecology paradigm (31), the role of Sch A within the TME was

interpreted as part of a dynamic ecological system. In this

context, YAP may function not only as a molecular signaling node

but also as an ecological sensor that enables cancer cells to

perceive and adapt to microenvironmental stresses. For example,

under glucose-deprived conditions, which are common in advanced

NSCLC, YAP activation typically confers survival advantages to

cancer cells by promoting metabolic reprogramming (32). However, the present findings

suggested that Sch A disrupted this adaptive mechanism by

potentially activating YAP, leading to the upregulation of ACSL4

and TfR expression. This shift triggered mitochondrial lipid

peroxidation and induced ferroptosis, effectively converting the

adaptive evolution of cancer cells into a self-destructive process.

This mechanism was analogous to embedding a self-destructive

program within an invasive species, in this case cancer cells,

thereby undermining their population stability. The present study,

therefore, transitioned from a purely molecular focus to a novel

paradigm of cancer ecological regulation. Sch A exploited the

evolutionary adaptability of cancer cells, specifically YAP

activation, and transformed them into ecologically vulnerable cells

through the induction of ferroptosis. This ecological perspective

underscores the potential of Sch A to modulate the dynamic

interactions between cancer cells and the TME in NSCLC, offering

novel avenues for predicting cancer progression and developing more

effective therapeutic strategies.

Furthermore, cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a

small subpopulation within tumors characterized by self-renewal,

differentiation and tumor-initiating capacity (33). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that lung CSCs are closely associated with recurrence, metastasis

and therapeutic resistance in NSCLC, making them both major

challenges and important targets in current anticancer strategies

(33,34). Although the present study focused

primarily on A549 and HCC827 cells, Sch A significantly activated

the YAP/ACSL4/TfR signaling axis, leading to intracellular

Fe2+ accumulation and lipid peroxidation, which are

hallmarks of ferroptosis. Notably, previous studies have reported a

close relationship between the malignant proliferation of lung CSCs

and ferroptosis (35,36). Therefore, the upregulation of TfR

induced by Sch A may further sensitize lung CSCs to ferroptotic

stress, suggesting that CSCs may serve as potential cellular

targets of Sch A. In future studies, it should be investigated

whether Sch A can effectively suppress the survival and

functionality of lung CSCs through ferroptosis induction, thereby

providing a novel approach to overcoming therapeutic resistance in

NSCLC.

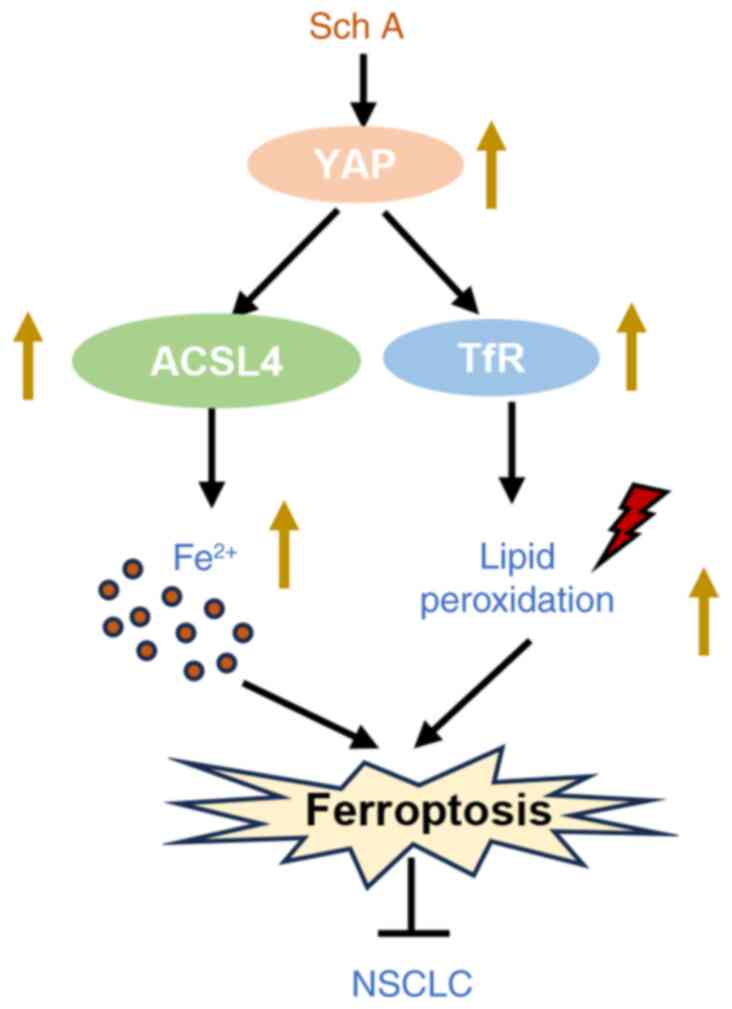

In conclusion, the results obtained in the present

study demonstrated that Sch A induced ferroptosis in lung cancer

cells through the YAP/ACSL4/TfR signaling pathway, leading to the

disruption of iron homeostasis and the generation of oxidative

stress (Fig. 7). This novel

mechanism highlights the potential of Sch A as a therapeutic agent

that promotes ferroptotic cell death, particularly in the treatment

of NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was funded by the Science and Technology

Planning Project of Shenzen Municipality (grant no.

JSGG20220226090203006).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WZ, YC and ZZ designed the research. WZ, YC and XW

performed the cell line experiments. XF analyzed the data. YH, YM,

QZ and MT performed the animal experiments. WZ, YC, XW and ZZ wrote

the manuscript and were responsible for making revisions. ZZ

secured funding. All authors confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments

guidelines and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

(US National Research Council). All animal experiments were

approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of

Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (approval no.

2024055R).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cao M and Chen W: Epidemiology of lung

cancer in China. Thorac Cancer. 10:3–7. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li C, Lei S, Ding L, Xu Y, Wu X, Wang H,

Zhang Z, Gao T, Zhang Y and Li L: Global burden and trends of lung

cancer incidence and mortality. Chin Med J (Engl). 136:1583–1590.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Li D, Shi J, Liang D, Ren M and He Y: Lung

cancer risk and exposure to air pollution: A multicenter North

China case-control study involving 14604 subjects. BMC Pulm Med.

23:1822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fang Y, Li Z, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, Man

J, Yang X and Lu M: Burden of lung cancer along with attributable

risk factors in China from 1990 to 2019, and projections until

2030. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:3209–3218. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Imyanitov EN, Iyevleva AG and Levchenko

EV: Molecular testing and targeted therapy for non-small cell lung

cancer: Current status and perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

157:1031942021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xiang Y, Liu X, Wang Y, Zheng D, Meng Q,

Jiang L, Yang S, Zhang S, Zhang X, Liu Y and Wang B: Mechanisms of

resistance to targeted therapy and immunotherapy in non-small cell

lung cancer: Promising strategies to overcoming challenges. Front

Immunol. 15:13662602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lei G and Zhuang Gan B: Targeting

ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

22:381–396. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fang K, Du S, Shen D, Xiong Z, Jiang K,

Liang D, Wang J, Xu H, Hu L, Zhai X, et al: SUFU suppresses

ferroptosis sensitivity in breast cancer cells via Hippo/YAP

pathway. iScience. 25:1046182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Niu X, Han P, Liu J, Chen Z and Ma X,

Zhang T, Li B and Ma X: Regulation of Hippo/YAP signaling pathway

ameliorates cochlear hair cell injury by regulating ferroptosis.

Tissue Cell. 82:1020512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cui J, Wang Y, Tian X, Miao Y, Ma L, Zhang

C, Xu X, Wang J, Fang W and Zhang X: LPCAT3 is transcriptionally

regulated by YAP/ZEB/EP300 and collaborates with ACSL4 and YAP to

determine ferroptosis sensitivity. Antioxid Redox Signal.

39:491–511. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li L, Ye Z, Xia Y, Li B, Chen L, Yan X,

Yuan T, Song B, Yu W, Rao T, et al: YAP/ACSL4 pathway-mediated

ferroptosis promotes renal fibrosis in the presence of kidney

stones. Biomedicines. 11:26922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wu Z, Sun J, Liao Z, Sun T, Huang L, Qiao

J, Ling C, Chen C, Zhang B and Wang H: Activation of PAR1

contributes to ferroptosis of Schwann cells and inhibits

regeneration of myelin sheath after sciatic nerve crush injury in

rats via Hippo-YAP/ACSL4 pathway. Exp Neurol. 384:1150532025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gu Y, Wu S, Fan J, Meng Z, Gao G, Liu T,

Wang Q, Xia H, Wang X and Wu K: CYLD regulates cell ferroptosis

through Hippo/YAP signaling in prostate cancer progression. Cell

Death Dis. 15:792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xiao Z, Xiao W and Li G: Research progress

on the pharmacological action of Schisantherin A. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2022:64208652022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mi X, Zhang Z, Cheng J, Xu Z, Zhu K and

Ren Y: Cardioprotective effects of Schisantherin A against

isoproterenol-induced acute myocardial infarction through

amelioration of oxidative stress and inflammation via modulation of

PI3K-AKT/Nrf2/ARE and TLR4/MAPK/NF-κB pathways in rats. BMC

Complement Med Ther. 23:2772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shen Y, Yang Y, Zhao Y, Nuerlan S, Zhan Y

and Liu C: YY1/circCTNNB1/miR-186-5p/YY1 positive loop aggravates

lung cancer progression through the Wnt pathway. Epigenetics.

19:23690062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xie C, Zhou X, Wu J, Chen W, Ren D, Zhong

C, Meng Z, Shi Y and Zhu J: ZNF652 exerts a tumor suppressor role

in lung cancer by transcriptionally downregulating cyclin D3. Cell

Death Dis. 15:7922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lussier G, Evans AJ, Houston I, Wilsnack

A, Russo CM, Vietor R and Bedocs P: Compact arterial monitoring

device use in resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the

aorta (REBOA): A simple validation study in swine. Cureus.

16:e707892024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jonna S and Subramaniam DS: Molecular

diagnostics and targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC): An update. Discov Med. 27:167–170. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang M, Herbst RS and Boshoff C: Toward

personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer.

Nat Med. 27:1345–1356. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Feng F, Pan L, Wu J, Liu M, He L, Yang L

and Zhou W: Schisantherin A inhibits cell proliferation by

regulating glucose metabolism pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Front Pharmacol. 13:10194862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang Z, Yu K, Hu Y, Su F, Gao Z, Hu T,

Yang Y, Cao X and Qian F: Schisantherin A induces cell apoptosis

through ROS/JNK signaling pathway in human gastric cancer cells.

Biochem Pharmacol. 173:1136732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Xian H, Feng W and Zhang J: Schizandrin A

enhances the efficacy of gefitinib by suppressing IKKβ/NF-κB

signaling in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Pharmacol.

855:10–19. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhu L, Wang Y, Huang X, Liu X, Ye B, He Y,

Yu H, Lv W, Wang L and Hu J: Schizandrin A induces non-small cell

lung cancer apoptosis by suppressing the epidermal growth factor

receptor activation. Cancer Med. 13:e69422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nilsson MB, Yang Y, Heeke S, Patel SA,

Poteete A, Udagawa H, Elamin YY, Moran CA, Kashima Y, Arumugam T,

et al: CD70 is a therapeutic target upregulated in EMT-associated

EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance. Cancer Cell. 41:340–355.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shyam Sunder S, Sharma UC and Pokharel S:

Adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy:

Pathophysiology, mechanisms and clinical management. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 8:2622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Qian LH, Wen KL, Guo Y, Liao YN, Li MY, Li

ZQ, Li SX and Nie HZ: Nutrient deficiency-induced downregulation of

SNX1 inhibits ferroptosis through PPARs-ACSL1/4 axis in colorectal

cancer. Apoptosis. 30:1391–1409. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wu X, Sheng H, Zhao L, Jiang M, Lou H,

Miao Y, Cheng N, Zhang W, Ding D and Li W: Co-loaded lapatinib/PAB

by ferritin nanoparticles eliminated ECM-detached cluster cells via

modulating EGFR in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis.

13:5572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Luo W: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology

theory: Cancer as multidimensional spatiotemporal ‘unity of ecology

and evolution’ pathological ecosystem. Theranostics. 13:1607–1631.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hsu PC, Yang CT, Jablons DM and You L: The

crosstalk between Src and Hippo/YAP signaling pathways in non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cancers (Basel). 12:13612020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu M, Wu H and Xu C: Targeting cancer

stem cell pathways for lung cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol.

35:78–85. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zakaria N, Satar NA, Abu Halim NH, Ngalim

SH, Yusoff NM, Lin J and Yahaya BH: Targeting lung cancer stem

cells: Research and clinical impacts. Front Oncol. 7:802017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zheng Y, Yang W, Wu W, Jin F, Lu D, Gao J

and Wang S: Diagnostic and predictive significance of the

ferroptosis-related gene TXNIP in lung adenocarcinoma stem cells

based on multi-omics. Transl Oncol. 45:1019262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhou J, Zhang L, Yan J, Hou A, Sui W and

Sun M: Curcumin induces ferroptosis in A549 CD133+ cells

through the GSH-GPX4 and FSP1-CoQ10-NAPH Pathways. Discov Med.

35:251–263. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|