Introduction

Lung cancer is a prevalent cause of cancer-related

mortality and poses a notable health risk (1). Lung cancer comprises several

histological subtypes, including adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma

and large cell carcinoma, which are collectively known as non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (2). NSCLC accounts for 80–90% of all lung

cancer cases (3). Because of the

poor prognosis of NSCLC and limited treatment options due to issues

such as late-stage drug resistance, there is a need to identify

novel therapeutic targets and strategies (3,4). For

diseases such as lung cancer, optimization of treatment strategies

often requires multifaceted considerations.

The regulation of biological functions in lung

cancer cells involves multiple levels and molecules. A preclinical

study revealed the promise of microRNA (miRNA/miR) mimics and

modulators in lung cancer therapy, potentially enhancing

conventional treatments by reversing drug resistance and increasing

cancer cell sensitivity (1). miRNA

therapy has entered the clinical trial phase, demonstrating its

safety and potential for therapeutic applications. For instance,

the miRNA-16 mimic exhibited preliminary efficacy and tolerability

in phase I clinical trials for NSCLC and malignant mesothelioma

(5). The positive outcomes of the

aforementioned preliminary trial provide evidence for miRNA

replacement therapy. miR-199a exhibits tumor-suppressive effects in

NSCLC by inhibiting growth and metastasis in vivo (6). miR-199a can inhibit the development

of lung cancer, particularly by suppressing the proliferation,

migration and infiltration of lung cancer cells, as well as by

inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and promoting lung cancer cell

apoptosis, thereby influencing lung cancer cell drug resistance

(7). miR-199a comprises two mature

forms, miR-199a-3p and miR-199a-5p, both of which serve important

biological roles (7). A previous

study has revealed that miR-199a-3p/5p was downregulated in NSCLC

tissues, cell lines and patient samples, and its overexpression

inhibited the malignant behavior of cells (6). Overexpression of miR-199a-3p markedly

inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma (8).

Additionally, miR-199a-3p is substantially downregulated in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and cells, and it can inhibit the

migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by

downregulating stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 expression (9). However, the specific mechanism of

action of miR-199a-3p in NSCLC remains to be elucidated. Therefore,

the present study focused on miR-199a-3p and explored its potential

as a therapeutic target.

Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) was

the first identified RNA N6-methyladenosine

(m6A) demethylase in eukaryotic cells, and regulates

m6A levels in mRNAs and serves a key role in tumor

progression and drug resistance, including in lung cancer (10,11).

m6A is the most abundant internal mRNA modification that

regulates processes such as alternative splicing and translation

(11). Transcriptome-wide

m6A maps, known as the epitranscriptome, reveal the

distribution and patterns of m6A in cellular RNAs. These

maps reveal specific mRNAs regulated by m6A, providing

mechanistic links between m6A and cell differentiation,

cancer progression and other processes (12). FTO promotes adipogenesis by

regulating the adipogenic pathway (13). m6A and FTO levels are

dysregulated in multiple cancer types, including lung cancer

(11). A study by Xu et al

(14) reported that FTO expression

was lower in NSCLC samples compared with healthy tissues and was

negatively associated with poor prognosis. Functional assays have

revealed that FTO inhibits NSCLC tumor cell proliferation and

metastasis in vitro and in vivo (14). However, a previous study has

reported an oncogenic role of FTO in acute myeloid leukemia

(15). This discrepancy suggests

that FTO functions are tissue- or cell-context-dependent.

Myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF1), a SCAN-domain zinc

finger transcription factor associated with numerous types of

cancers, shows decreased expression in pancreatic cancer and NSCLC

tumors compared to normal tissues (16). High MZF1 expression is associated

with lower overall survival in patients with glioblastoma

multiforme (17). However, the

specific role of MZF1 in lung cancer remains to be fully

elucidated.

Claudin domain-containing 1 (CLDND1), also known as

claudin-25, has been identified as a novel member of the claudin

protein family (18). Claudins

serve important roles in intercellular adhesion. Elevated

expression of CLDND1 is associated with malignant progression in

estrogen receptor-negative, hormone therapy-resistant breast

cancer. Aberrant CLDND1 levels are also linked to vascular

pathologies (19). A study

investigating the regulation of CLDND1 expression identified a

strong enhancer region near its promoter that shares high homology

with the ETS domain-containing protein Elk-1 (ELK1) binding

sequence, suggesting that CLDND1 may be a potential target for

anticancer drug development (19).

However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated

the specific role of CLDND1 in the development of lung cancer.

The present study aimed to investigate a novel

signaling axis involving miR-199a-3p, FTO, MZF1, and CLDND1 in

NSCLC. Bioinformatics tools including miRwalk were employed to

predict potential downstream targets of miR-199a-3p. The SRAMP

online tool was utilized to assess the potential for m6A

modification in MZF1 mRNA, while the JASPAR database was used to

analyze the binding affinity of MZF1 to the CLDND1 promoter region.

It was hypothesized that FTO, as an m6A demethylase, may

regulate MZF1 expression via m6A modification, thereby

influencing CLDND1 transcription and contributing to NSCLC

progression. The study was designed to experimentally validate this

proposed miR-199a-3p/FTO/m6A/MZF1/CLDND1 axis, with the

goal of elucidating its functional role in NSCLC and exploring its

potential as a diagnostic or therapeutic target.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Yanbian University Affiliated Hospital (approval no.

2021094; Yanji, China), and written informed consent was obtained

from all patients. The study adhered to the principles outlined in

The Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical samples

Lung cancer tissue specimens were collected from 15

patients with NSCLC (adenocarcinoma) who underwent surgical

resection at Yanbian University Affiliated Hospital (Yanji, China)

between January 2022 and June 2023. For each patient, a paired

paracancerous tissue specimen (≥5 cm from the tumor margin and

pathologically confirmed to be free of tumor cell infiltration) was

simultaneously collected.

Inclusion criteria were: i) histopathological

confirmation of primary NSCLC (adenocarcinoma), ii) no prior

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy before

surgery, and iii) availability of complete clinicopathological

data. Exclusion criteria were: i) presence of other malignant

tumors or severe systemic diseases, ii) history of autoimmune or

infectious diseases, and iii) inadequate tissue quantity or RNA

quality. Immediately after resection, all tissue specimens were

snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further

analysis to preserve molecular integrity.

A priori power analysis was performed using G*Power

3.1 (Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Germany), setting α=0.05

and an effect size=0.8, which indicated that n=15 achieves a

statistical power >85%. Patients' ages ranged from 35 to 69

years (median=52 years). All diagnoses were confirmed by the

Department of Pathology. The clinical characteristics of patients

with NSCLC are shown in Table

SI.

Cell culture and grouping

CAL12T (cat. no. MZ-8194), HCC44 (cat. no. MZ-8190),

NCIH1993 (cat. no. MZ-8234) and A549 (cat. no. B163886) lung cancer

cells, and BEAS-2B human normal bronchial epithelial cells (cat.

no. MZ-0677), were obtained from Ningbo Mingzhou Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd. All cells were cultured in DMEM; cat. no. 11965092; Gibco,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; cat. no. 10099141C; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml penicillin, 100

µg/ml streptomycin; cat. no. 15140122; all Gibco) at 37°C in a

humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. Cells were

sub-cultured at 70–80% confluence using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA

(HyClone; Cytiva), and only cells in the logarithmic growth phase

were used for experiments. All cell lines were authenticated via

short tandem repeat analysis and regularly tested for the absence

of mycoplasma contamination (Table

SII).

The A549 cells were divided into the following

groups based on the experimental needs: i) miR-199a-3p mimic group

transfected with miR-199a-3p mimic; ii) negative control (NC) mimic

group transfected with miR-199a-3p mimic NC sequence; iii) NC mimic

+ overexpression (oe)-NC group transfected with miR-199a-3p mimic

NC sequence and FTO overexpression NC plasmid; iv) miR-199a-3p

mimic + oe-NC group transfected with miR-199a-3p mimic and FTO

overexpression NC plasmid; v) NC mimic + oe-FTO group transfected

with miR-199a-3p mimic NC sequence and FTO overexpression plasmid;

vi) miR-199a-3p mimic + oe-FTO group transfected with miR-199a-3p

mimic and FTO overexpression plasmid; vii) oe-NC group transfected

with overexpression NC plasmid; viii) oe-FTO group transfected with

FTO overexpression plasmid; ix) oe-MZF1 group transfected with MZF1

overexpression plasmid; x) oe-NC + short hairpin RNA (sh)-NC group

transfected with FTO overexpression and MZF1 silencing NC plasmid;

xi) oe-FTO + sh-NC group transfected with FTO overexpression

plasmid and MZF1 silencing NC plasmid; xii) oe-NC + sh-MZF1 group

transfected with FTO overexpression NC plasmid and MZF1 silencing

plasmid; xiii) oe-FTO + sh-MZF1 group transfected with FTO

overexpression plasmid and MZF1 silencing plasmid; xiv) oe-MZF1 +

sh-NC group transfected with MZF1 overexpression plasmid and CLDND1

silencing NC plasmid; xv) oe-NC + sh-CLDND1 group transfected with

MZF1 overexpression and CLDND1 silencing plasmid; and xvi) oe-MZF1

+ sh-CLDND1 group transfected with MZF1 overexpression plasmid and

CLDND1 silencing plasmid.

The FTO and MZF1 oe plasmids were constructed using

the pCMV6-AC-GFP vector (Hunan Fenghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. ZT877), and the MZF1 and CLDND1 silencing plasmids

(sh-MZF1, sh-CLDND1) along with their negative controls (sh-NC)

were generated using the pGPU6-GFP-Neo backbone (Hunan Fenghui

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. BR150). Synthetic miR-199a-3p

mimic and NC mimic were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd., and prepared at a working concentration of 50 nM. All nucleic

acids were transfected using Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat.

no. 11668019; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following

the manufacturer's protocol. For each well of a 6-well plate, 4 µg

plasmid DNA or 50 nM miRNA mimic was mixed with 10 µl Lipofectamine

2000 in 250 µl serum-free Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 6 h before the

medium was replaced with complete DMEM, and harvested 24–48 h

post-transfection for subsequent assays (Fig. S1) (20). Sequence information is shown in

Table SIII.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from A549 cells and human

NSCLC tumor and paired paracancerous tissue using TRIzol

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized with the

PrimeScript RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (cat. no. RR047A;

Takara Bio, Inc.) using the following program: genomic DNA removal

at 42°C for 2 min, reverse transcription at 37°C for 15 min, and

enzyme inactivation at 85°C for 5 sec. For miRNA analysis, cDNA was

generated using the miRNA First Strand cDNA Synthesis (Tailing

Reaction) kit (cat. no. B532451-0020; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.)

with a tailing/RT program of 37°C for 60 min followed by 85°C for 5

min. qPCR was performed on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using

SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The

thermal cycling conditions were: 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of

95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec; melt-curve analysis was

conducted from 60–95°C with a gradual ramp. The relative gene

expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (21), with U6 as the

internal reference for miRNA and GAPDH as the reference for mRNA.

All primers were purchased from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Table I) (22). The experiment was repeated three

times.

| Table I.Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence,

5′à3′ |

|---|

| miR-199a-3p |

|

| (human) |

|

|

Forward |

ACAGTAGTCTGCACATTGGTTA |

|

Reverse |

GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT |

| FTO (human) |

|

|

Forward |

GTTCACAACCTCGGTTTAGTTC |

|

Reverse |

CATCATCATTGTCCACATCGTC |

| MZF1 (human) |

|

|

Forward |

TTCCGGTGCTTCCGCTATG |

|

Reverse |

CTCCTTGGAGCGTACCTCT |

| CLDND1 (human) |

|

|

Forward |

TGGTATAGCCCACCAGAAAGGAC |

|

Reverse |

CAATCCCGCTATTGTGGTTTCCG |

| U6 (human) |

|

|

Forward |

CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

|

Reverse |

AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

| GAPDH (human) |

|

|

Forward |

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

|

Reverse |

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from human NSCLC tumor

and paired paracancerous tissue using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no.

P0013C; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) containing 1 mM

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Following centrifugation at 12,000 ×

g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected, and the protein

concentration was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat.

no. 23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of

protein (30 µg per lane) were loaded and separated by 10%

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by transfer

onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were

blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (BD Difco™; BD

Biosciences) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) at

room temperature for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies as follows: Rabbit anti-FTO (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab126605; Abcam), anti-MZF1 (1:800; cat. no. ab64866; Abcam) and

anti-CLDND1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 13255; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.). Anti-GAPDH (1:2,500; cat. no. ab9485; Abcam) was used as an

internal reference. After washing with TBST, membranes were

incubated with HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L

(1:2,000; cat. no. ab97051; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature.

Equal volumes of liquids A and B from an ECL fluorescence testing

kit [cat. no. abs920; Absin Bioscience Inc.] were mixed in a dark

room and added dropwise to the membrane. Protein signals were

captured using the Bio-Rad Image Analysis System (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) with an exposure time ranging between 10 and 30

sec, dynamically adjusted based on signal intensity to ensure

optimal image quality without saturation. Image grayscale values

were analyzed using Quantity One v4.6.2 software (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.), and relative protein content was expressed as

the grayscale value of the corresponding protein band divided by

the grayscale value of the GAPDH protein band. The relative protein

content was calculated based on the gray value ratio of the target

protein to GAPDH (23).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The miRwalk biological website (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/)

was utilized for analysis and predicted that the miR-199a-3p

sequence contained binding sites for FTO. To verify this

interaction, wild-type (Wt) and mutant (Mut) 3′-UTR fragments of

FTO were synthesized and cloned into the pGL3-Control vector (cat.

no. E1741; Promega Corporation) to generate pGL3-FTO-Wt and

pGL3-FTO-Mut constructs. The Mut plasmid was obtained by

site-directed mutagenesis within the miR-199a-3p seed region (for

example, A replaced with T). Synthetic miR-199a-3p mimic

(5′-ACAGUAGUCUGCACAUUGGUUA-3′) and negative control mimic (miR-NC)

(5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′) were purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. For luciferase reporter analysis, A549 cells

were co-transfected with 100 ng of PGLO-FTO-Wt or PGLO-FTO-Mut

vector and 50 nM miR-199a-3p mimic or miR-NC using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat. no. 11668019; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), the same reagent and protocol

described above (24).

The binding site of the transcription factor MZF1

was obtained from the JASPAR website (jaspar.genereg.net/). To

evaluate the regulatory effect of MZF1 on the CLDND1 promoter,

oe-NC and oe-MZF1 plasmids were co-transfected with reporter

constructs containing either the Wt or Mut CLDND1 promoter

sequences cloned upstream of the luciferase gene in the pGL3-Basic

vector (cat. no. E1751; Promega), which lacks a promoter and is

suitable for promoter-driven transcriptional analysis. A pRL-TK

Renilla luciferase plasmid (cat. no. E2241; Promega) was

co-transfected as an internal control. Cells were collected and

lysed 48 h post-transfection, and dual-luciferase activity was

quantified using the same assay kit.

Firefly luciferase activity was first determined by

adding 100 µl Luciferase Assay Reagent II to each lysate, followed

by Renilla luciferase measurement with 100 µl Stop &

Glo® Reagent using a GloMax® 20/20

Luminometer (Promega). The relative luciferase activity was

calculated as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luminescence,

expressed as relative light units (RLU). Each experiment was

independently repeated three times to ensure reproducibility

(25).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

(ChIP)

A ChIP kit (cat. no. KT101; Guangzhou Saicheng

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used to detect the enrichment of MZF1

in the promoter region of the CLDND1 gene. When A549 cells reached

70–80% confluence, they were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for

10 min at room temperature, and the reaction was quenched with 125

mM glycine for 5 min. Cells were collected by centrifugation at

12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, washed twice with cold PBS, and lysed

in SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1)

containing protease inhibitor cocktail. After incubation on ice for

10 min, the lysates were subjected to sonication at 20 kHz with

30/30 sec off cycles for a total of 10 min at 4°C to shear

chromatin and obtain DNA fragments of 200–500 bp. For each

immunoprecipitation, chromatin from ~1×106 cells (≈500

µl total volume) was diluted in ChIP dilution buffer and incubated

overnight at 4°C with either 2 µg rabbit anti-MZF1 antibody (cat.

no. ab64866, Abcam, UK) or 2 µg normal rabbit IgG (cat. no.

ab172730, Abcam) as a NC. The immune complexes were captured with

25 µl Protein G magnetic beads for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. Beads

were separated on a magnetic rack, and washed three times with

low-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM EDTA; 1%

Triton X-100; 0.1% SDS), high-salt buffer (same as above except 500

mM NaCl), LiCl buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1; 250 mM LiCl; 1%

NP-40; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 1 mM EDTA) and TE buffer (10 mM

Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA). Chromatin complexes were eluted twice

with 1% SDS/0.1 M NaHCO3 elution buffer at 65°C for 15

min, pooled, and reverse-crosslinked overnight at 65°C. Samples

were treated sequentially with RNase A (37°C, 30 min) and

Proteinase K (55°C, 1 h), and DNA was purified using

silica-membrane spin columns (Qiagen DNA Cleanup Kit). Purified DNA

was subjected to qPCR to detect MZF1 binding to the CLDND1 promoter

as aforementioned. This amplified fragment spans nucleotides −1017

to +192 relative to the transcription start site of the CLDND1

promoter (GenBank Accession No. NM_001040181) (26). The experiment was repeated three

times.

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation

(Me-RIP)

The SRAMP online tool (cuilab.cn/sramp; version

2023-10) was used to predict potential m6A modification

sites in MZF1 mRNA. Total RNA was isolated from A549 cells using

the TRIzol method as previously described (27), and mRNA was isolated and purified

using the PolyATtract mRNA Isolation System [cat. no. A-Z5300; Aide

Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd.]. An aliquot of 5 µg purified mRNA

was diluted in 500 µl MeRIP lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM

Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1× RNase inhibitor, and 1×

protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated with 30 µl Protein A/G

magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) pre-bound to antibodies

for immunoprecipitation. Anti-m6A antibody (2 µg;1:500;

cat. no. ab151230; Abcam) or anti-IgG antibody (2 µg;1:100; cat.

no. ab109489; Abcam) was incubated with Protein A/G beads in

binding buffer at 4°C for 1 h with gentle rotation to form

antibody-bead complexes. The prepared RNA-antibody-bead mixture was

incubated overnight at 4°C. The beads were magnetically separated

and washed three times with low-salt buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH

7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 0.1% NP-40; 0.5 mM EDTA) and once with high-salt

buffer (same composition but 500 mM NaCl) to remove non-specific

binding. Each wash was performed for 5 min at 4°C with rotation.

Beads were suspended in 100 µl elution buffer (6.7 mM

m6A-free N6-methyladenosine solution, 50 mM

Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA) and incubated at 55°C for 1 h to

release methylated RNA. The eluate was subjected to

phenol-chloroform extraction and RNA was precipitated with ethanol,

followed by resuspension in RNase-free water. RNA concentration and

purity were measured with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo

Fisher Scientific). RNA was eluted with elution buffer, purified by

phenol-chloroform extraction and analyzed by RT-qPCR for MZF1 as

aforementioned. Primer sequences targeting the conserved exonic

regions of MZF1 were designed using Primer-BLAST (National Center

for Biotechnology Information, database version 2024-03) and are

listed in Table I (28,29).

Photoactivatable

ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation

(PAR-CLIP)

A549 cells were incubated with 200 µM 4-thiouridine

for 16 h, then UV-irradiated at 365 nm (0.4 J/cm2) on

ice. Cells were lysed in PAR-CLIP buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5,

150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, RNase and

protease inhibitors) and cleared by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10

min, 4°C). Supernatant (500 µl) were incubated overnight at 4°C

with 2 µg anti-FTO antibody (ab126605, Abcam, UK) or 2 µg rabbit

IgG (cat. no. ab172730, Abcam) and 30 µl Protein A/G magnetic beads

(Thermo Fisher Scientific). Beads were magnetically separated,

washed three times with high-salt buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4,

500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40) and once with low-salt buffer

(150 mM NaCl). The precipitated RNA was labeled with (γ-32P)-ATP

using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) for 30 min at

37°C, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and

visualized by autoradiography. Crosslinked RNA was recovered after

Proteinase K digestion (0.5 mg/ml, 37°C, 30 min) and

phenol-chloroform extraction. Recovered RNA was reverse-transcribed

with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (RR047A; Takara

Bio, Japan) and analyzed by RT-qPCR as aforementioned (30). The experiment was repeated three

times.

Transwell assay

Cell migration and invasion were assessed using

Transwell 24-well cell culture inserts (6.5 mm diameter, 8.0 µm

pore; cat. no. 3422; Corning, Inc.). For the invasion assay,

Matrigel® gel (cat. no. 356234; Corning, Inc.) was added

at 37°C for 30–60 min. A549 cells in the logarithmic phase were

trypsinized, counted, and resuspended in serum-free DMEM. For each

insert, 200 µl of cell suspension containing 1×105 cells

was added to the upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled with

800 µl DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS to serve as a

chemoattractant. All plates were incubated at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. For the migration assay, the

procedure was identical except that the inserts were not pre-coated

with Matrigel. After incubation, non-migrated or non-invaded cells

on the upper surface were gently removed with a cotton swab. The

membranes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room

temperature, stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution (cat. no.

C0121; Beyotime Biotechnology) at room temperature for 20 min, and

washed twice with PBS. Cells that migrated or invaded the lower

surface of the membrane were visualized and counted under an

inverted light microscope (Eclipse TE2000; Nikon Corporation,

Tokyo, Japan). To ensure accuracy, cells from at least four

randomly selected microscopic areas were counted (31).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using CCK-8 (cat.

no. CA1210; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

A549 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded into 96-well

plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well in 100 µl

complete medium and cultured for 24 h to allow cell adherence and

recovery prior to transfection. Cells were then transfected

according to the experimental grouping, and proliferation was

assessed beginning 48 h after transfection. At 0, 24, 48, and 72 h

after the onset of proliferation monitoring (i.e., after

transfection), 10 µl CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, followed

by incubation at 37°C for 3 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was

measured using a microplate reader (Multiskan™ FC,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The absorbance was directly

proportional to the number of proliferating cells in the culture

medium, and a cell growth curve was plotted based on these values

(32). The experiment was repeated

three times.

Flow cytometry

After 48 h of transfection, the A549 cells were

digested with 0.25% trypsin (cat. no. 15050057; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific Inc.) and collected in a flow-through tube. Cell

suspensions were centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the

supernatant was discarded. An Annexin-V-FITC apoptosis detection

kit (cat. no. ab14085; Abcam) was used to formulate the Annexin

V-FITC/PI staining solution at a ratio of 1:2:50 by mixing

Annexin-V-FITC, PI and HEPES buffer solutions according to the

manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1×106 cells were

resuspended per 100 µl of the staining solution, and after 15 min

of incubation at room temperature, 1 ml HEPES buffer solution (cat.

no. PB180325; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was

added. Fluorescence was detected using a BD FACSCanto™

II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), with FITC and PI emissions

collected at 525 nm and 620 nm, respectively, after excitation at

488 nm. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1;

BD Biosciences). Results were expressed as the percentage of

apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+ and Annexin

V+/PI− fractions) to ensure quantitative

reproducibility (33). The

experiment was repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with at least three

independent replicates (n=3), and data are presented as the mean ±

SD. For comparisons between two independent (unpaired) groups, an

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used. For paired designs,

a paired two-tailed Student's t-test was applied. By contrast, for

three or more treatment groups, one-way ANOVA was employed,

supplemented with Tukey's post hoc multiple comparison test, for

comparisons involving multiple time points. For comparisons

involving both time and treatment factors, two-way ANOVA was used.

The Sidak methods were selected for post hoc multiple comparisons

at each time point. All statistical tests were two-sided, with

P<0.05 considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference, and actual P-values were retained to three decimal

places. Error bars in the graphs indicate the-SD. All statistical

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (Dotmatics).

Results

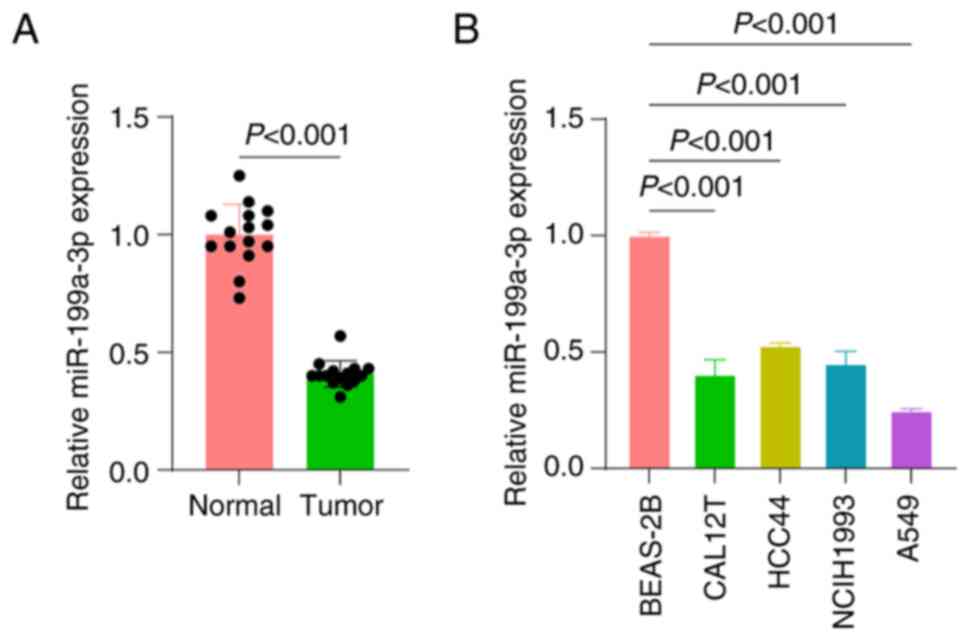

miR-199a-3p expression is

significantly downregulated in NSCLC tissues and cells

In the study of the molecular mechanisms of lung

cancer, the expression patterns of miRNAs have received notable

attention, and the aberrant expression of several miRNAs in lung

cancer has been reported to be closely related to cancer

progression (34). The RT-qPCR

results in the present study showed that the expression levels of

miR-199a-3p were significantly downregulated in NSCLC tissues

compared with normal tissues (Fig.

1A). Furthermore, miR-199a-3p expression was also assessed in

various lung cancer cell lines. The present results showed that in

the lung cancer cell lines, the expression levels of miR-199a-3p

were significantly downregulated, with the A549 cell line having

the lowest expression level (Fig.

1B). Therefore, the A549 cell line was selected for subsequent

in-depth study.

miR-199a-3p inhibits A549 cell

proliferation, migration and invasion by targeting FTO

inhibition

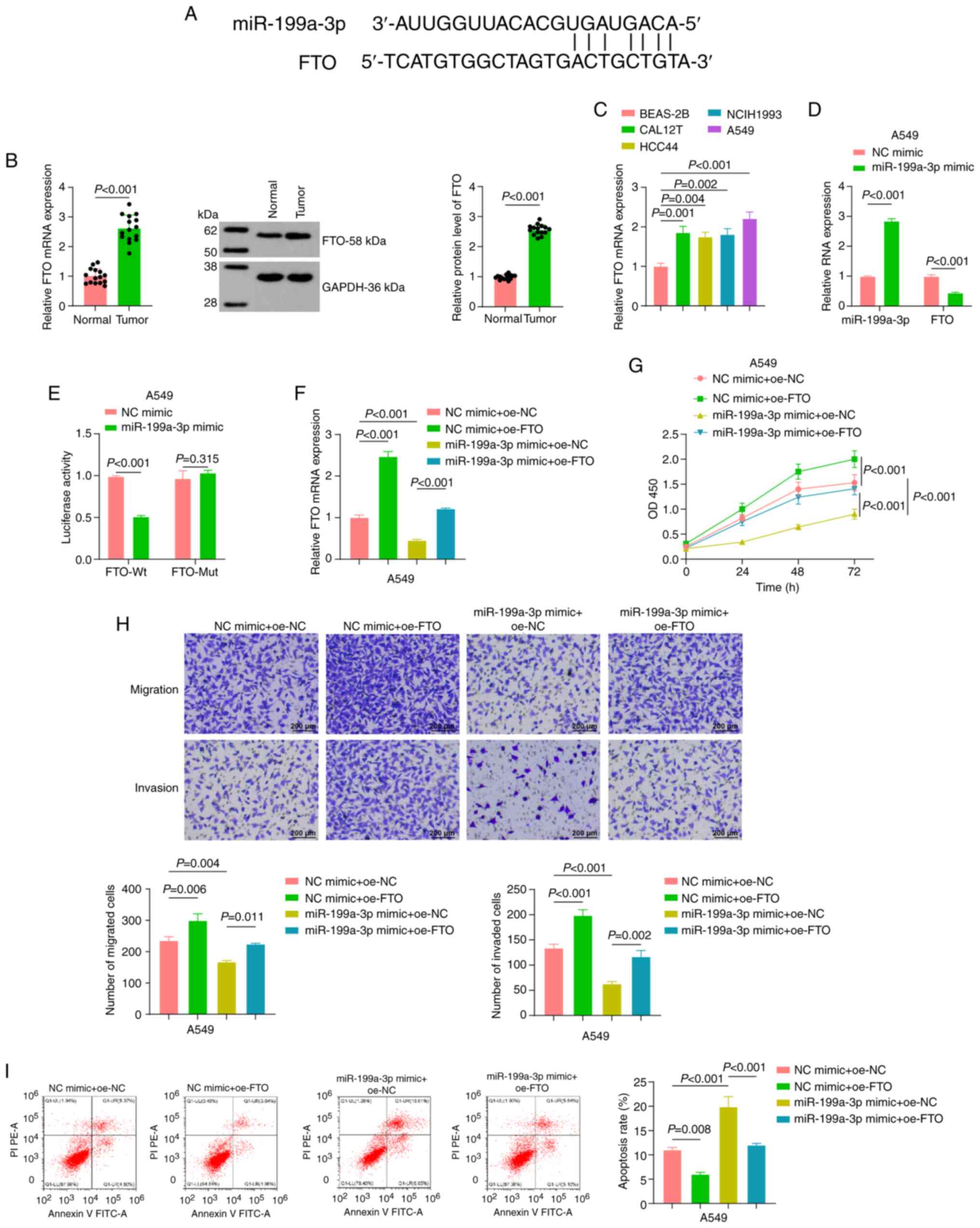

To elucidate the mechanism of action of miR-199a-3p

in A549 cells, bioinformatics tools were used to predict the

potential downstream target genes of miR-199a-3p, which led to the

identification of FTO as a potential direct target (Fig. 2A). A previous study reported an

oncogenic role of FTO in acute myeloid leukemia (15). To validate whether FTO exhibits

similar dysregulation in NSCLC, FTO mRNA and protein expression

levels were analyzed in paired NSCLC and adjacent normal tissue, as

well as in lung cell lines. The results of RT-qPCR and western

blotting revealed that both FTO mRNA and protein expression were

significantly upregulated in NSCLC tissues compared with the

adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 2B).

Consistently, FTO mRNA expression was markedly higher in NSCLC cell

lines (A549, CAL12T, HCC44, and NCI-H1993) than in the normal human

bronchial epithelial cell line BEAS-2B (Fig. 2C).

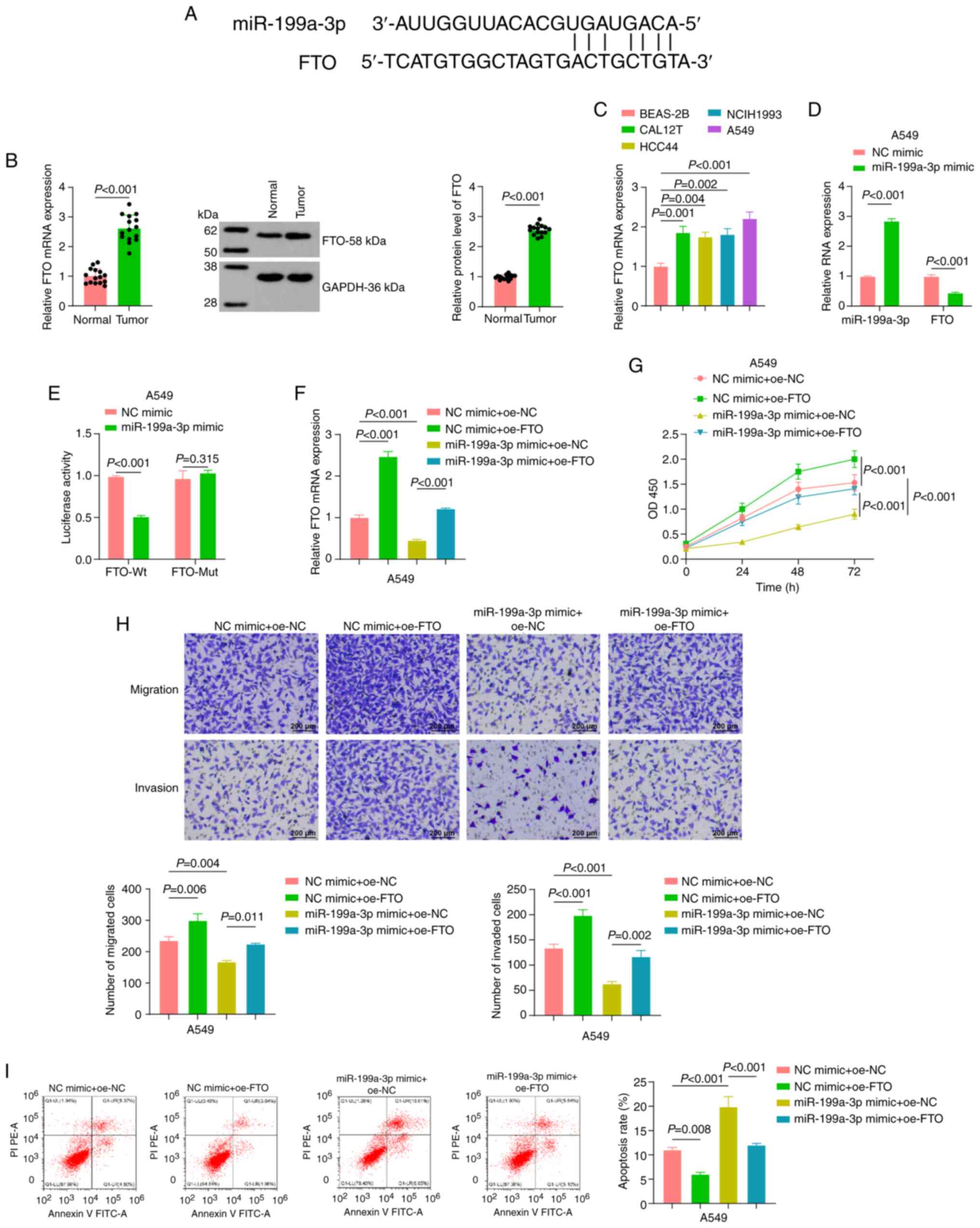

| Figure 2.Effect of miR-199a-3p on the

biological function of A549 cells by downregulating FTO. (A)

Bioinformatics tool ‘miRwalk’ predicted the possible downstream

target gene of miR-199a-3p: FTO. (B) RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis were performed to detect the expression levels of FTO in

non-small cell lung cancer tissues, with paracancerous tissues as

the control (n=15). (C) RT-qPCR was performed to detect the

expression levels of FTO in lung cancer cells. (D) After

miR-199a-3p mimic transfection, RT-qPCR was used to detect the

expression levels of miR-199a-3p and FTO. (E) A dual-luciferase

reporter assay verified the targeting relationship between

miR-199a-3p and FTO. (F) RT-qPCR was used to assess the expression

levels of FTO in A549 cells in each miR mimic + oe plasmid

combination group. (G) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay assessing the

proliferation of A549 cells in each miR mimic + oe plasmid

combination group. (H) Transwell assays indicated the migration and

invasion of A549 cells in each miR mimic + oe plasmid combination

group. Scale bar, 200 µm. (I) Flow cytometry was performed to

detect the apoptosis of A549 cells in each miR mimic + oe plasmid

combination group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, n=3

independent experiments. oe, overexpression; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; miR, microRNA; FTO, fat mass and

obesity-associated protein; NC, negative control; Wt, wild-type;

Mut, mutant; OD, optical density. |

In subsequent experiments, A549 cells were

transfected with miR-199a-3p mimic and NC mimic, and the expression

levels of miR-199a-3p and FTO in transfected cells were analyzed by

RT-qPCR. The results showed that the expression levels of

miR-199a-3p were significantly increased in the miR-199a-3p mimic

group compared with the NC mimic group. At the same time, FTO

expression was significantly decreased in the miR-199a-3p mimic

group compared with the NC mimic group, suggesting miR-199a-3p

negatively regulated FTO expression (Fig. 2D).

Dual-luciferase reporter assays were conducted to

verify the direct targeting relationship between miR-199a-3p and

FTO. The Wt and Mut sequences of the FTO 3′-UTR were co-transfected

with miR-199a-3p mimic into A549 cells. The results revealed that

in the cells co-transfected with the FTO-Wt 3′-UTR, the luciferase

activity was significantly lower in the miR-199a-3p mimic group

compared with the NC mimic group. However, in the cells

co-transfected with the FTO-Mut 3′-UTR, there was no significant

difference in luciferase activity between the two mimic groups,

indicating that miR-199a-3p specifically targeted the FTO 3′-UTR

(Fig. 2E).

RT-qPCR results revealed that, compared with those

in the NC mimic + oe-NC group, the expression levels of FTO were

significantly reduced in cells in the miR-199a-3p mimic + oe-NC

group. When FTO was overexpressed, its expression level in the

miR-199a-3p mimic + oe-FTO group was significantly higher than that

in the miR-199a-3p mimic + oe-NC group (Fig. 2F). Cell proliferation, migration,

and invasion were significantly reduced, whereas apoptosis was

markedly increased, in the miR-199a-3p mimic + oe-NC group compared

with the NC mimic + oe-NC group. By contrast, cells transfected

with NC mimic + oe-FTO exhibited increased proliferation,

migration, and invasion and decreased apoptosis relative to the

corresponding controls, indicating a tumor-promoting effect of FTO

overexpression. Furthermore, co-transfection of miR-199a-3p mimic

with oe-FTO partially restored the proliferative, migratory, and

invasive capacities that had been suppressed by miR-199a-3p alone

(Fig. 2G-I).

In summary, the present study demonstrated that

miR-199a-3p inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of

A549 cells by targeting FTO. This revealed the important role of

the miR-199a-3p/FTO axis in regulating the behavior of A549 cells

and provided potential novel targets for molecularly targeted

therapy of NSCLC.

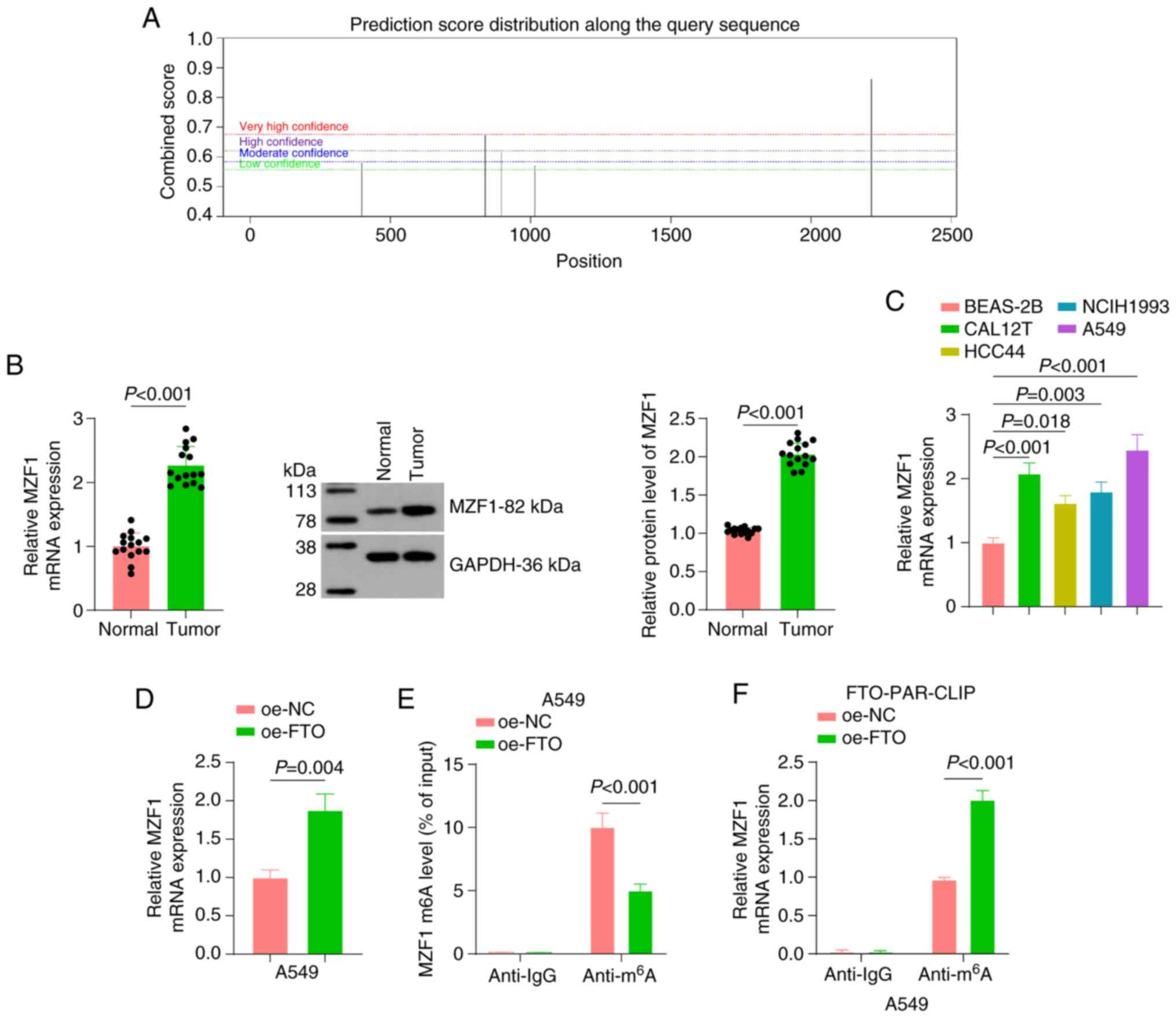

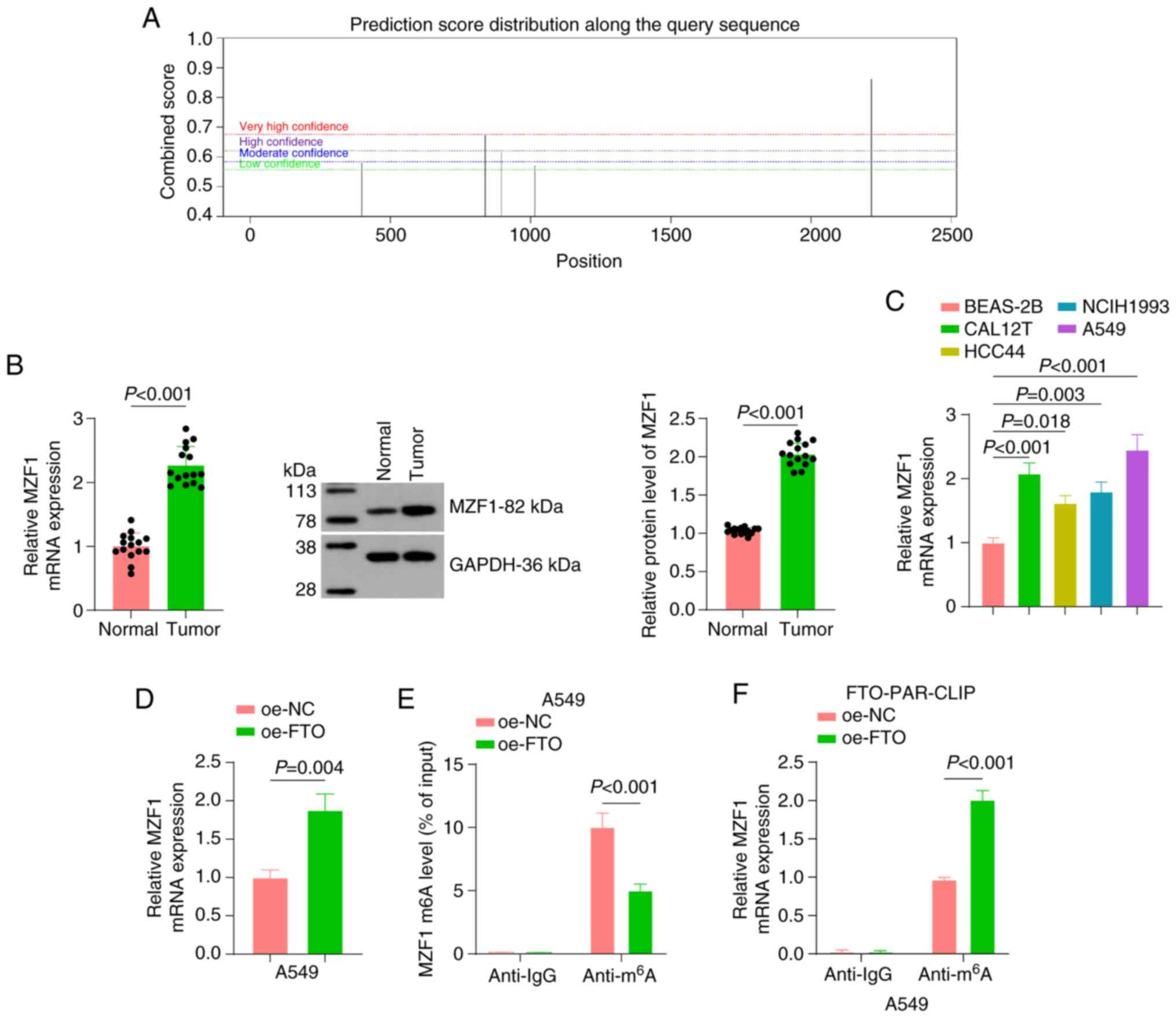

m6A demethylase FTO

promotes MZF1 expression by reducing the levels of m6A

modification of MZF1

A previous study reported that MZF1 promotes

tumorigenesis and metastasis (35), and an online website analysis

showed that MZF1 mRNA can undergo m6A modification

(Fig. 3A). Therefore, we

hypothesized that FTO, an m6A demethylase, affects tumor

progression by regulating the m6A modification of

MZF1.

| Figure 3.Mechanism of m6A

modification regulation of MZF1 by FTO. (A) The SRAMP online tool

(http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp) predicted

potential m6A modification sites on MZF1 mRNA. (B)

RT-qPCR and western blot analysis were conducted to assess the

expression levels of MZF1 in NSCLC tissues, with paracancerous

tissues as the control (n=15). (C) RT-qPCR analysis of MZF1 mRNA

expression in normal bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) and NSCLC cell

lines (CAL12T, HCC44, NCIH1993 and A549). (D) RT-qPCR was used to

determine MZF1 expression after overexpression of FTO. (E)

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation assay detecting the

m6A modification level of MZF1 after overexpression of

FTO. (F) PAR-CLIP assay detecting the direct interaction between

FTO and MZF1 mRNA. All cell experiments were repeated three times.

oe, overexpression; m6A, N6-methyladenosine;

MZF1, myeloid zinc finger 1; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated

protein; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NSCLC,

non-small cell lung cancer; NC, negative control; PAR-CLIP,

photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and

immunoprecipitation. |

Expression levels of MZF1 were examined in NSCLC

tissues and cell lines by RT-qPCR and western blot analyses. As

shown in Fig. 3B, both the mRNA

and protein levels of MZF1 were significantly higher in NSCLC tumor

tissues than in their paired adjacent normal tissues. Consistently,

MZF1 mRNA expression was markedly upregulated in NSCLC cell lines

(CAL12T, HCC44, A549, and NCI-H1993) compared with BEAS-2B, with

the highest expression observed in A549 cells (Fig. 3C). Subsequently, FTO was

overexpressed in the cells; overexpression of FTO significantly

increased the mRNA expression levels of MZF1 (Fig. 3D).

To determine how FTO regulated MZF1, the

m6A modification level of MZF1 after FTO overexpression

was examined using a Me-RIP assay. FTO overexpression significantly

reduced the m6A modification of MZF1 mRNA compared with

the oe-NC group (Fig. 3E).

Additionally, a PAR-CLIP assay was employed to investigate the

direct interaction between FTO and MZF1 mRNA. The

anti-m6A antibody pulled down significantly more MZF1

mRNA than the anti-IgG control, and the enrichment was markedly

higher in the oe-FTO group than in the oe-NC group (Fig. 3F).

Taken together, the present data demonstrated that

FTO could promote MZF1 expression by reducing the m6A

modification level of MZF1 mRNA.

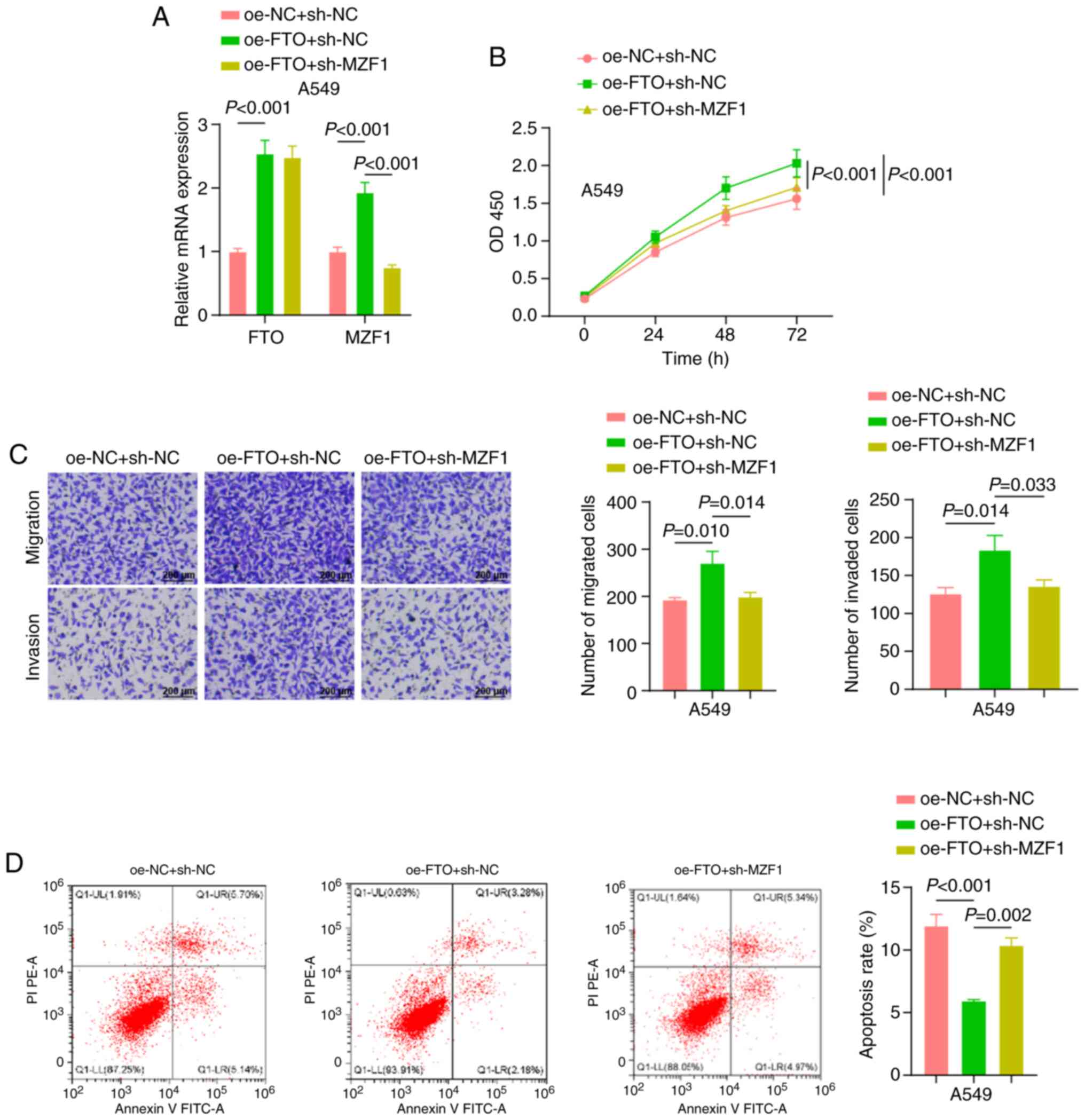

Silencing of MZF1 reverses the

promoting effect of FTO on A549 cell proliferation, migration and

invasion

To further ascertain the effect of the FTO/MZF1 axis

on the biological function of A549 cells, three groups were

established: oe-NC + sh-NC, oe-FTO + sh-NC, and oe-FTO + sh-MZF1.

RT-qPCR demonstrated that the expression levels of both FTO and

MZF1 were significantly elevated in the cells in the oe-FTO + sh-NC

group compared with the oe-NC + sh-NC group, and the expression

levels of MZF1 were significantly lower in the cells in the oe-FTO

+ sh-MZF1 group compared with the oe-FTO + sh-NC group (Fig. 4A).

The biological functions of A549 cells were

evaluated using CCK-8, Transwell and flow cytometry assay. The

results revealed that, compared with the oe-NC + sh-NC group, the

oe-FTO + sh-NC group exhibited significantly higher cell

proliferation, migration and invasion, as well as a significantly

lower apoptosis. When MZF1 was silenced, the effect of FTO was

partially reversed, as demonstrated by the significant decrease in

proliferation, migration and invasion in the oe-FTO + sh-MZF1 group

compared with the oe-FTO + sh-NC group, as well as a significant

increase in apoptosis (Fig.

4B-D).

Taken together, the present study demonstrated that

silencing of MZF1 reversed the promoting effect of FTO on A549 cell

proliferation, migration and invasion.

MZF1 promotes A549 cell proliferation,

migration and invasion by facilitating CLDND1 transcription

MZF1 is a transcription factor that can influence

tumor progression by promoting downstream gene expression (36). The binding site of the

transcription factor MZF1 was obtained from the JASPAR website

(https://jaspar.genereg.net/) (Fig. 5A), and MZF1 showed a high binding

affinity (GAAATCCCCTATT) for the CLDND1 promoter region. CLDND1

expression was significantly higher in NSCLC tumor tissues than in

adjacent normal tissue (Fig. 5B).

Consistently, CLDND1 mRNA levels were markedly elevated in A549 and

other NSCLC cell lines (NCI-H1993, CAL12T, HCC44) compared with

BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 5C).

![Mechanism of the transcriptional

regulation of CLDND1 by MZF1. (A) The JASPAR website (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) was used to retrieve the

binding site of the transcription factor MZF1. (B) RT-qPCR and

western blot analysis were performed to detect the expression

levels of CLDND1 in non-small cell lung cancer tissues, using

paracancerous tissues as the control (n=15). (C) RT-qPCR analysis

of CLDND1 mRNA expression in normal bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B)

and NSCLC cell lines (CAL12T, HCC44, NCIH1993 and A549). (D) After

overexpression of MZF1, RT-qPCR was performed to measure MZF1 and

CLDND1 expression. (E) Dual-luciferase reporter assay examining the

effect of MZF1 on CLDND1 promoter activity. (F) Chromatin

immunoprecipitation assays determining the enrichment of MZF1 in

the CLDND1 promoter region [Chr3:167, 450, 703–167, 450, 714

(hg38)]. All cell experiments were repeated three times. oe,

overexpression; CLDND1, claudin domain-containing 1; MZF1, myeloid

zinc finger 1; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NC,

negative control; Wt, wild-type; Mut, mutant.](/article_images/mmr/33/1/mmr-33-01-13736-g04.jpg) | Figure 5.Mechanism of the transcriptional

regulation of CLDND1 by MZF1. (A) The JASPAR website (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) was used to retrieve the

binding site of the transcription factor MZF1. (B) RT-qPCR and

western blot analysis were performed to detect the expression

levels of CLDND1 in non-small cell lung cancer tissues, using

paracancerous tissues as the control (n=15). (C) RT-qPCR analysis

of CLDND1 mRNA expression in normal bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B)

and NSCLC cell lines (CAL12T, HCC44, NCIH1993 and A549). (D) After

overexpression of MZF1, RT-qPCR was performed to measure MZF1 and

CLDND1 expression. (E) Dual-luciferase reporter assay examining the

effect of MZF1 on CLDND1 promoter activity. (F) Chromatin

immunoprecipitation assays determining the enrichment of MZF1 in

the CLDND1 promoter region [Chr3:167, 450, 703–167, 450, 714

(hg38)]. All cell experiments were repeated three times. oe,

overexpression; CLDND1, claudin domain-containing 1; MZF1, myeloid

zinc finger 1; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NC,

negative control; Wt, wild-type; Mut, mutant. |

To explore the regulatory effect of MZF1 on CLDND1,

MZF1 was overexpressed in A549 cells. RT-qPCR results revealed that

MZF1 overexpression significantly elevated the mRNA levels of

CLDND1 (Fig. 5D). In addition, a

dual-luciferase reporter assay revealed that overexpression of MZF1

significantly increased the luciferase activity of the wild-type

(CLDND1-Wt) promoter reporter compared with the oe-NC group,

whereas no significant change was observed in the mutant

(CLDND1-Mut) reporter lacking the predicted MZF1 binding motif

(Fig. 5E).

ChIP experiments indicated that MZF1 directly

regulated the CLDND1 promoter, showing a significant increase in

MZF1 enrichment in the CLDND1 promoter region (Fig. 5F).

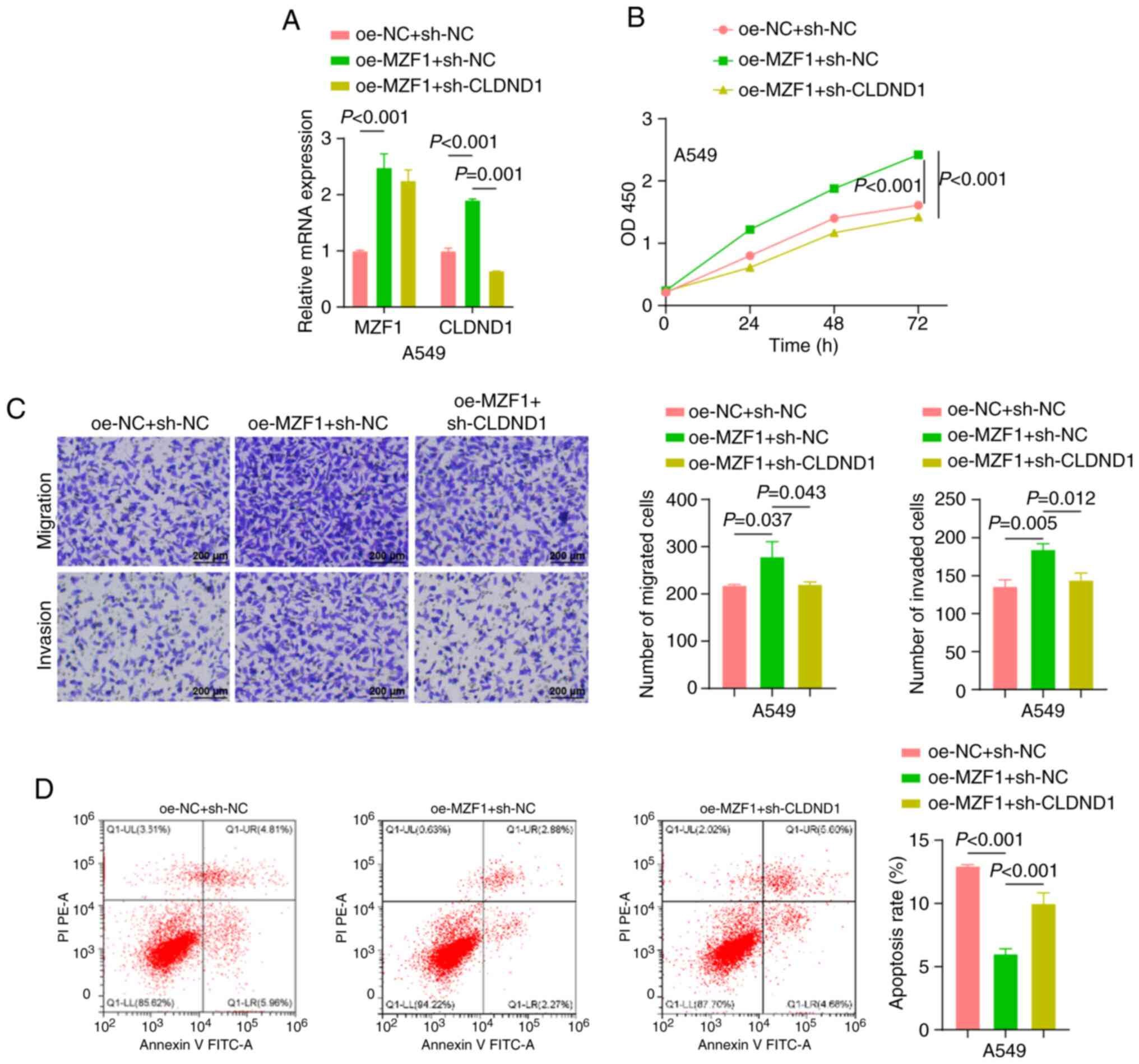

In the cell function experiments, the effects of

different transfection combinations on the proliferation, migration

and invasion of A549 cells were evaluated. RT-qPCR results revealed

that the expression levels of both MZF1 and CLDND1 were

significantly elevated in the cells of the oe-MZF1 + sh-NC group

compared with those in the oe-NC + sh-NC group. Furthermore, the

expression levels of CLDND1 were lower in the oe-MZF1 + sh-CLDND1

group than in the oe-MZF1 + sh-NC group (Fig. 6A). Functional experiments

demonstrated that cell proliferation, migration and invasion were

significantly increased, and apoptosis was significantly decreased

in the oe-MZF1 + sh-NC group compared with the oe-NC + sh-NC group.

When CLDND1 was silenced, the effect of MZF1 on A549 cell

proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis was partially

reversed (Fig. 6B-D).

In summary, these data indicated that MZF1 enhanced

the proliferation, migration and invasion of A549 cells by

promoting the transcription of CLDND1, and that the silencing of

CLDND1 effectively inhibited these effects.

Discussion

Despite advances in research and treatment, lung

cancer remains a notable threat to human health, with a low 5-year

survival rate (37). Therefore,

there is a need to develop reliable preclinical models and

effective treatments. The findings of the present study contributed

to the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying lung

cancer and may provide novel targets for the development of

molecularly targeted therapies (38).

Aberrant miR-199a-3p expression has been observed in

various cancer types and exhibits tumor suppressor effects. In one

study, miR-199a-3p was shown to inhibit tumor growth in vivo

and suppress the invasion and migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

cells by downregulating the expression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase

1, thus providing a potential target for the treatment of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (9).

Furthermore, miR-199a-3p is downregulated in various human

malignancies, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), leading to

poor prognosis in patients with HCC (39). In HCC, knockdown of zinc finger and

homeoboxes-1 (ZHX1) inhibits the upregulation of p53-upregulated

modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) following miR-199a-3p transfection.

Furthermore, silencing of either ZHX1 or PUMA reverses the effects

of miR-199a-3p (40). One study

has predicted that miR-199a-5p and miR-199a-3p can serve as early

diagnostic markers or therapeutic targets in NSCLC (6). However, the specific mechanism by

which miR-199a-3p acts in lung cancer remains to be fully

elucidated. Evidence supports the anticancer role of the

miR-199a/Rheb/mTOR axis in NSCLC. Rheb, a common target of

miR-199a-5p and miR-199a-3p, is involved in regulating the mTOR

signaling pathway. Knockdown of Rheb recapitulated the

tumor-suppressive effects of miR-199a overexpression, including

inhibited proliferation and migration. Furthermore, miR-199a-5p/3p

enhances the sensitivity of EGFR-T790M mutant NSCLC cells to

(6). Taken together, these

findings demonstrate that miR-199a-5p/3p can serve as an oncogene

that inhibits the mTOR signaling pathway by targeting Rheb, thus

inhibiting the regulatory process of NSCLC (6).

The present study explored a novel regulatory

mechanism: miR-199a-3p targeted FTO to regulate the m6A

modification of MZF1, thus inhibiting CLDND1 expression, which

provided a novel perspective to understand the function of

miR-199a-3p in NSCLC. Observations revealed that miR-199a-3p was

downregulated in NSCLC tissues and cells, and it had a direct

targeting relationship with FTO. By targeting and inhibiting FTO,

miR-199a-3p suppressed the migration, proliferation and invasion of

A549 cells. FTO promoted MZF1 expression by decreasing the level of

m6A modification of MZF1. In addition, silencing of MZF1

reversed the promoting effect of FTO on lung cancer cell migration,

proliferation and invasion. Furthermore, MZF1 promoted A549 cell

migration, proliferation and invasion by promoting CLDND1

transcription.

Mechanistically, estrogen receptor α (ESR1) serves

as the target for FTO, where heightened FTO expression decreases

the m6A levels in ESR1 mRNA (14). A study by Xu et al (14) reported two distinct m6A

modification sites, 5409A and 5247A, located in the 3′-UTR of ESR1,

with FTO capable of reducing their methylation. In addition, the

m6A readers insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding

protein (IGF2BP)3 and YTH domain-containing family protein 1

(YTHDF1) identify and bind to these m6A sites, thereby

enhancing ESR1 mRNA stability and promoting tumor growth. ESR1 was

also found to exhibit diagnostic potential for NSCLC. In summary,

the study by Xu et al (14)

elucidated an important mechanism by which the

FTO/YTHDF1/IGF2BP3/ESR1 axis regulates the epithelial transcriptome

and highlighted the potential of m6A-dependent NSCLC

therapeutic strategies.

The data in the present study revealed that FTO

stabilized MZF1 by removing its m6A modification,

thereby linking RNA methylation changes to the CLDND1-driven

processes of cell migration and invasion. Notably, the study by Xu

et al (14) proposed that

FTO exerted an oncogenic effect by stabilizing ESR1, while another

study has suggested that FTO has a tumor-suppressive effect in

adenocarcinoma models (41). These

discrepancies may stem from cell-type specificity, for example,

adenocarcinoma vs. squamous cell carcinoma or different

microenvironments, as well as variations in downstream targets. The

findings of the present study supported the oncogenic role of FTO

through the stabilization of MZF1 and underscored the need for

future validation of the translational potential of FTO in models

based on EGFR mutation types or immune therapy resistance

backgrounds. In summary, FTO may possess dual regulatory functions

in lung cancer, with specific modes of action potentially depending

on cancer subtype, target gene context and microenvironmental

differences, which are factors that should be further clarified in

future research.

Regulation of MZF1 signaling has been associated

with the progression of numerous human malignancies, such as

triple-negative breast and cervical cancer (42). Silencing of MZF1 inhibits cell

proliferation, whereas its aberrant expression contributes to

cancer development (43). Limited

research exists on the specific mechanisms underlying the

m6A modification of MZF1 in lung cancer, which supports

the novelty of the present study in exploring novel therapeutic

regulatory mechanisms in this context. Furthermore, CLDND1, as a

tight junction-associated protein, interacts with other tight

junction proteins, such as occludin and claudins, to collectively

construct and maintain the intact structure of intercellular tight

junctions, forming a selective barrier that strictly regulates the

transport of substances between cells and the conduction of

intercellular signals, which is important for maintaining the

stability of the tissue internal environment (18,44).

The role of CLDND1 during cancer progression has

also attracted attention. Changes in CLDND1 expression are closely

related to tumor development in certain cancer types, such as

breast cancer (19). The

inhibitory effect of gefitinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor,

on CLDND1 expression has been evaluated using a luciferase reporter

and ELK1 overexpression in ChIP assays. ELK1, identified as an

enhancer region activator, transiently elevated CLDND1 expression

at both the mRNA and protein levels. EGF-induced phosphorylation of

ELK1 further increased CLDND1 expression, which was inhibited by

gefitinib (19). Thus,

EGF-dependent activation of ELK1 leads to the induction of CLDND1

expression. These findings pave the way for the development of

novel anticancer drugs targeting CLDND1 (19). The present study revealed a

significant increase in the enrichment of MZF1 in the promoter

region of CLDND1 using ChIP experiments, supporting its direct

action on the CLDND1 promoter. The present study also identified a

novel role for CLDND1 in the malignant progression of tumors. A

previous study has focused on the effects of CLDND1 on endothelial

cell adhesion and cell junctions (45). However, the present study

demonstrated that once transcriptionally activated by MZF1, CLDND1

also promoted malignant tumor phenotypes.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, miR-199a-3p

was lowly expressed in NSCLC cells, which led to a weakening of its

inhibitory effect on FTO, which in turn increased the expression

levels of FTO. FTO, as an m6A demethylase, removed

m6A modifications on the MZF1 mRNA, improved the mRNA

stability and translational efficiency of MZF1 and increased the

protein levels of MZF1. Subsequently, MZF1, as a transcription

factor, upregulated the expression levels of CLDND1. The high

expression of CLDND1 promoted malignant biological behaviors such

as migration, proliferation and invasion of NSCLC cells. In

summary, miR-199a-3p regulated the m6A modification of

MZF1 by targeting FTO, resulting in the inhibition of CLDND1

expression, which ultimately affected the biological functions of

NSCLC cells.

Although the present study primarily focused on the

axis of miR-199a-3p/FTO-mediated m6A modification of

MZF1 and its transcriptional regulation of CLDND1, the present

study did not systematically exclude the involvement of other key

factors. The stability and translational efficiency of MZF1 may

have also been regulated by m6A reader proteins,

including the IGF2BP family and YTHDF1/2/3 (46). m6A methyltransferases

and demethylases such as methyltransferase-like protein 3/14 and

alkylated DNA repair protein alkB homolog 5 may have also

indirectly intervened by regulating the expression of MZF1

(47); and iii) in addition to

MZF1, there may have been other cis-acting elements and binding

proteins on the CLDND1 promoter (19,48).

As the present study did not conduct m6A site

prediction, enrichment analysis or RNA immunoprecipitation

validation of the reader proteins, the relevant regulatory

mechanisms require further exploration.

The present study also had certain limitations. The

small sample size in the present study may undermine the

universality of the molecular associations among miR-199a-3p, FTO,

MZF1, and CLDND1, potentially limiting the reliability of clinical

relevance analysis. Furthermore, the present study relied on in

vitro cell experiments and lacked data from in vivo

animal models, making it difficult to comprehensively evaluate the

role of this pathway in living tumors. Additionally, the signaling

pathways in NSCLC cells are complex, and the factors in the present

study may have participated in multiple pathways, necessitating

further research with expanded samples to explore their

interrelationships and mechanisms.

In conclusion, miR-199a-3p targeted and inhibited

FTO expression, thereby blocking the m6A demethylation

modification of MZF1 and suppressing MZF1 expression and the

transcriptional activation of downstream CLDND1 (Fig. S2). This ultimately inhibited the

migration, proliferation and invasion of NSCLC cells. The

aforementioned mechanism suggested that the

miR-199a-3p/FTO/MZF1/CLDN1 signaling pathway serves an important

role in the development and progression of NSCLC. Unlike the

findings of a study by Xu et al (14) indicating that FTO participates in

NSCLC progression by regulating ESR1, the present study is, to the

best of our knowledge, the first to propose that miR-199a-3p

targets and inhibits FTO, relieving its m6A

demethylation effect on MZF1 and indirectly inhibiting the

MZF1-mediated transcriptional activation of CLDND1. To the best of

our knowledge, this multi-level regulatory axis of miRNA-epigenetic

modification/transcription factor/target gene has not been reported

before. The present study explored a novel upstream regulator,

miR-199a-3p, and downstream oncogenic mechanism, the MZF1/CLDND1

axis, of FTO in NSCLC, providing novel insights for

m6A-targeted therapy.

Future studies could validate the clinical

significance of this signaling pathway in larger sample cohorts,

study the association between the expression levels of miR-199a-3p,

FTO, MZF1 and CLDND1, and clinical parameters such as TNM staging

to enhance its clinical applicability, establish lung cancer

xenograft models to simulate the human tumor microenvironment and

validate the biological functions and therapeutic potential of this

pathway, and test this signaling axis in models with EGFR mutations

or immune therapy resistance to explore its roles in different lung

cancer subtypes and treatment resistance scenarios, providing novel

targets and strategies for precision therapy. m6A reader

protein in RNA pull-down experiments will be supplemented in the

future to further refine the analysis of the regulatory pathway

network.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Application Foundation

Project of Yanbian University in 2024 (grant no. ydkj202458).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC conceived and designed the study. XL performed

the experiments. HZ, WY and EZ conducted the data analysis and

interpretation. WY and EZ edited the manuscript. YC and HZ confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Yanbian University Affiliated Hospital (approval no.

2021094; Yanji, China) and written informed consent was obtained

from the patients. The study followed The Declaration of

Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Yang H, Liu Y, Chen L, Zhao J, Guo M, Zhao

X, Wen Z, He Z, Chen C and Xu L: MiRNA-based therapies for lung

cancer: Opportunities and challenges? Biomolecules. 13:8772023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ruiz-Cordero R and Devine WP: Targeted

therapy and checkpoint immunotherapy in lung cancer. Surg Pathol

Clin. 13:17–33. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang K, Mei Z, Zheng M, Liu X, Li D and

Wang H: FTO-mediated autophagy inhibition promotes non-small cell

lung cancer progression by reducing the stability of SESN2 mRNA.

Heliyon. 10:e275712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zahmatyar M, Kharaz L, Abiri Jahromi N,

Jahanian A, Shokri P and Nejadghaderi SA: The safety and efficacy

of binimetinib for lung cancer: A systematic review. BMC Pulm Med.

24:3792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

van Zandwijk N, Pavlakis N, Kao SC, Linton

A, Boyer MJ, Clarke S, Huynh Y, Chrzanowska A, Fulham MJ, Bailey

DL, et al: Safety and activity of microRNA-loaded minicells in

patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma: a

first-in-man, phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet

Oncol. 18:1386–1396. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu X, Wang X, Chai B, Wu Z, Gu Z, Zou H,

Zhang H, Li Y, Sun Q, Fang W and Ma Z: miR-199a-3p/5p regulate

tumorgenesis via targeting Rheb in non-small cell lung cancer. Int

J Biol Sci. 18:4187–4202. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Meng W, Li Y, Chai B, Liu X and Ma Z:

miR-199a: A tumor suppressor with noncoding RNA network and

therapeutic candidate in lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 23:85182022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hou G, Wang Y, Zhang M, Hu Y, Zhao Y, Jia

A, Wang P, Zhao W, Zhao W and Lu Z: miR-199a-3p suppresses

progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through

inhibiting mTOR/p70S6K pathway. Anticancer Drugs. 32:157–167. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hu W, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Luo Q, Huang N,

Chen R, Tang X, Li X and Luo H: MicroRNA-199a-3p suppresses the

invasion and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through

SCD1/PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 110:1108332023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wei H, Li Z, Liu F, Wang Y, Ding S, Chen Y

and Liu J: The role of FTO in tumors and its research progress.

Curr Med Chem. 29:924–933. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Azzam SK, Alsafar H and Sajini AA: FTO m6A

demethylase in obesity and cancer: Implications and underlying

molecular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 23:38002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zaccara S, Ries RJ and Jaffrey SR:

Publisher correction: Reading, writing and erasing mRNA

methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:7702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang Z, Yu GL, Zhu X, Peng TH and Lv YC:

Critical roles of FTO-mediated mRNA m6A demethylation in regulating

adipogenesis and lipid metabolism: Implications in lipid metabolic

disorders. Genes Dis. 9:51–61. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xu X, Qiu S, Zeng B, Huang Y, Wang X, Li

F, Yang Y, Cao L, Zhang X, Wang J and Ma L:

N6-methyladenosine demethyltransferase FTO mediated

m6A modification of estrogen receptor alpha in non-small

cell lung cancer tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 43:1288–1302. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang ZW, Zhao XS, Guo H and Huang XJ: The

role of m6A demethylase FTO in chemotherapy resistance

mediating acute myeloid leukemia relapse. Cell Death Discov.

9:2252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu D, Tan H, Su W, Cheng D, Wang G, Wang

J, Ma DA, Dong GM and Sun P: MZF1 mediates oncogene-induced

senescence by promoting the transcription of p16(INK4A). Oncogene.

41:414–426. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang CH, Wu HC, Hsu CW, Chang YW, Ko CY,

Hsu TI, Chuang JY, Tseng TH and Wang SM: Inhibition of MZF1/c-MYC

Axis by cantharidin impairs cell proliferation in glioblastoma. Int

J Mol Sci. 23:147272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ohnishi M, Ochiai H, Matsuoka K, Akagi M,

Nakayama Y, Shima A, Uda A, Matsuoka H, Kamishikiryo J, Michihara A

and Inoue A: Claudin domain containing 1 contributing to

endothelial cell adhesion decreases in presence of cerebellar

hemorrhage. J Neurosci Res. 95:2051–2058. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Matsuoka H, Yamaoka A, Hamashima T, Shima

A, Kosako M, Tahara Y, Kamishikiryo J and Michihara A:

EGF-dependent activation of ELK1 contributes to the induction of

CLDND1 expression involved in tight junction formation.

Biomedicines. 10:17922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yin H, Chen L, Piao S, Wang Y, Li Z, Lin

Y, Tang X, Zhang H, Zhang H and Wang X: M6A RNA

methylation-mediated RMRP stability renders proliferation and

progression of non-small cell lung cancer through regulating

TGFBR1/SMAD2/SMAD3 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 30:605–617. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gong Y, Li X and Xie L: Circ_0001897

regulates high glucose-induced angiogenesis and inflammation in

retinal microvascular endothelial cells through

miR-29c-3p/transforming growth factor beta 2 axis. Bioengineered.

13:11694–11705. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Robinson R, Srinivasan M, Shanmugam A,

Ward A, Ganapathy V, Bloom J, Sharma A and Sharma S: Interleukin-6

trans-signaling inhibition prevents oxidative stress in a mouse

model of early diabetic retinopathy. Redox Biol. 34:1015742020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu P, Peng QH, Tong P and Li WJ:

Astragalus polysaccharides suppresses high glucose-induced

metabolic memory in retinal pigment epithelial cells through

inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction-induced apoptosis by

regulating miR-195. Mol Med. 25:212019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhao G, Liang J, Shan G, Gu J, Xu F, Lu C,

Ma T, Bi G, Zhan C and Ge D: KLF11 regulates lung adenocarcinoma

ferroptosis and chemosensitivity by suppressing GPX4. Commun Biol.

6:5702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang W, Ruan X, Li Y, Zhi J, Hu L, Hou X,

Shi X, Wang X, Wang J, Ma W, et al: KDM1A promotes thyroid cancer

progression and maintains stemness through the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway. Theranostics. 12:1500–1517. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S,

Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K,

Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, et al: Topology of the human

and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature.

485:201–206. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lin S, Xu H, Qin L, Pang M, Wang Z, Gu M,

Zhang L, Zhao C, Hao X, Zhang Z, et al: UHRF1/DNMT1-MZF1

axis-modulated intragenic site-specific CpGI methylation confers

divergent expression and opposing functions of PRSS3 isoforms in

lung cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 13:2086–2106. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang F, Hou W, Li X, Lu L, Huang T, Zhu M

and Miao C: SETD8 cooperates with MZF1 to participate in

hyperglycemia-induced endothelial inflammation via elevation of

WNT5A levels in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Mol Biol Lett.

27:302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xue X, Wang M, Zhang X, Ma L and Wang J:

PAR-CLIP assay in ferroptosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2712:29–43. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hou Y, Zhang Q, Pang W, Hou L, Liang Y,

Han X, Luo X, Wang P, Zhang X, Li L and Meng X: YTHDC1-mediated

augmentation of miR-30d in repressing pancreatic tumorigenesis via

attenuation of RUNX1-induced transcriptional activation of Warburg

effect. Cell Death Differ. 28:3105–3124. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu L and Xie D, Xie H, Huang W, Zhang J,

Jin W, Jiang W and Xie D: ARHGAP10 inhibits the proliferation and

metastasis of CRC cells via blocking the activity of RhoA/AKT

signaling pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 12:11507–11516. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang G, Wang L, Zhao L, Yang F, Lu C, Yan

J, Zhang S, Wang H and Li Y: Silibinin induces both apoptosis and

necroptosis with potential anti-tumor efficacy in lung cancer.

Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 24:1327–1338. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Iqbal MA, Arora S, Prakasam G, Calin GA

and Syed MA: MicroRNA in lung cancer: Role, mechanisms, pathways

and therapeutic relevance. Mol Aspects Med. 70:3–20. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kan A, Liu S, He M, Wen D, Deng H, Huang

L, Lai Z, Huang Y and Shi M: MZF1 promotes tumour progression and

resistance to anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment in hepatocellular

carcinoma. JHEP Rep. 6:1009392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Brix DM, Bundgaard Clemmensen KK and

Kallunki T: Zinc finger transcription factor MZF1-A specific

regulator of cancer invasion. Cells. 9:2232020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Meng FT, Jhuang JR, Peng YT, Chiang CJ,

Yang YW, Huang CY, Huang KP and Lee WC: Predicting lung cancer

survival to the future: Population-based cancer survival modeling

study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 10:e467372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li H, Chen Z, Chen N, Fan Y, Xu Y and Xu

X: Applications of lung cancer organoids in precision medicine:

From bench to bedside. Cell Commun Signal. 21:3502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen G, Zhang Z, Li Y, Wang L and Liu Y:

LncRNA PTPRG-AS1 promotes the metastasis of hepatocellular

carcinoma by enhancing YWHAG. J Oncol. 2021:36243062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Guan J, Liu Z, Xiao M, Hao F, Wang C, Chen

Y, Lu Y and Liang J: MicroRNA-199a-3p inhibits tumorigenesis of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting ZHX1/PUMA signal. Am J

Transl Res. 9:2457–2465. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wu G, Yan Y, Cai Y, Peng B, Li J, Huang J,

Xu Z and Zhou J: ALKBH1-8 and FTO: Potential therapeutic targets

and prognostic biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma pathogenesis.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6339272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yue CH, Liu JY, Chi CS, Hu CW, Tan KT,

Huang FM, Pan YR, Lin KI and Lee CJ: Myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF1)

maintains the mesenchymal phenotype by down-regulating IGF1R/p38

MAPK/ERα signaling pathway in high-level MZF1-expressing TNBC

cells. Anticancer Res. 39:4149–4164. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mudduluru G, Vajkoczy P and Allgayer H:

Myeloid zinc finger 1 induces migration, invasion, and in vivo

metastasis through Axl gene expression in solid cancer. Mol Cancer

Res. 8:159–169. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Matsuoka H, Shima A, Uda A, Ezaki H and

Michihara A: The retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor α

positively regulates tight junction protein claudin

domain-containing 1 mRNA expression in human brain endothelial

cells. J Biochem. 161:441–450. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Shima A, Matsuoka H, Yamaoka A and

Michihara A: Transcription of CLDND1 in human brain endothelial

cells is regulated by the myeloid zinc finger 1. Clin Exp Pharmacol

Physiol. 48:260–269. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu

H, Zhao BS, Mesquita A, Liu C, Yuan CL, et al: Recognition of RNA

N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA

stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol. 20:285–295. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu J, Ren D, Du Z, Wang H, Zhang H and

Jin Y: m6A demethylase FTO facilitates tumor progression

in lung squamous cell carcinoma by regulating MZF1 expression.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 502:456–464. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sun J, Liu P and Wang X: MiR-595 and

Cldnd1: Potential related factors for bone loss in postmenopausal

women with hip osteoporotic fracture. PLoS One. 19:e03131062024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Mechanism of the transcriptional

regulation of CLDND1 by MZF1. (A) The JASPAR website (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) was used to retrieve the

binding site of the transcription factor MZF1. (B) RT-qPCR and

western blot analysis were performed to detect the expression

levels of CLDND1 in non-small cell lung cancer tissues, using

paracancerous tissues as the control (n=15). (C) RT-qPCR analysis

of CLDND1 mRNA expression in normal bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B)

and NSCLC cell lines (CAL12T, HCC44, NCIH1993 and A549). (D) After

overexpression of MZF1, RT-qPCR was performed to measure MZF1 and

CLDND1 expression. (E) Dual-luciferase reporter assay examining the

effect of MZF1 on CLDND1 promoter activity. (F) Chromatin

immunoprecipitation assays determining the enrichment of MZF1 in

the CLDND1 promoter region [Chr3:167, 450, 703–167, 450, 714

(hg38)]. All cell experiments were repeated three times. oe,

overexpression; CLDND1, claudin domain-containing 1; MZF1, myeloid

zinc finger 1; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NC,

negative control; Wt, wild-type; Mut, mutant.](/article_images/mmr/33/1/mmr-33-01-13736-g04.jpg)