Introduction

Homocystinuria (HCU) is a rare genetic metabolic

disorder that results from the deficiency of the enzyme

cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), which is a key player in the

metabolism of the amino acid methionine. As it is an autosomal

recessive genetic disease, a child must inherit two defective

copies of the gene from the parents to be affected. Other enzymes

involved in homocysteine metabolism include

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and methionine synthase

(MS), especially in vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. This CBS

enzymatic deficiency leads to the accumulation of homocysteine and

methionine in the blood and urine of affected patients (1), eventually leading to a wide range of

notable and irreversible multi-organ complications.

HCU imposes a notable and multifaceted healthcare

burden, particularly when misdiagnosed in early childhood or when

inadequate metabolic control is achieved. HCU requires lifelong

management, strict dietary restrictions, multivitamin

supplementation and frequent biochemical monitoring, all of which

place financial and logistical burdens on patients, families and

healthcare systems. This burden is escalated by the required

management and hospitalization of patients due to disease-related

complications with often life-threatening consequences. Recent

population-based analysis further quantified this burden,

documenting substantial rates of thromboembolism, ophthalmic

morbidity and healthcare utilization in classical HCU (2).

Foundational syntheses, such as that reported by

Schneede et al (3), have

established the enzymatic basis of HCU, emphasized homocysteine as

a pathogenic vascular risk factor and summarized the then-standard

treatments: i) Dietary methionine restriction; ii) supplementation

with high-dose pyridoxine, folate or B12; and iii) betaine.

Current therapies for HCU such as dietary methionine

restriction and supplementation with vitamins B6, B12 and folate

often fail to prevent complications, especially in patients who are

non-responsive to treatment. With the understanding of disease

pathogenesis, patient-focused novel interventions that correct

fundamental metabolic imbalances, such as enzyme replacement, gene

therapy and RNA-based treatments, have become important (2). The present review revisits the

foundational enzymology of HCU in the context of modern

genotype-phenotype insights and incorporates novel epidemiological

data quantifying the healthcare burden of classical HCU. The

present review also integrates developments through early 2025,

including the discontinuation of the pegtarviliase program and the

rebranding of CDX-6512 as SYNT-202, with corresponding updates from

clinical trial data, regulatory announcements and pipeline

disclosures.

Epidemiology

Consanguinity and gene mutations are the predominant

risk factors for HCU, which explains the high incidence of HCU in

some populations, such as Irish and Middle Eastern populations

(4,5).

Although HCU is a rare genetic enzymatic disorder,

with global prevalence estimates of 1 in 300,000 individuals, its

prevalence rates vary considerably across different regions due to

factors such as genetic mutations and consanguinity (4). Qatar has the highest known incidence

at ~1 in 1,800 births, most likely due to the high rates of

consanguineous marriages (4),

while Kuwait and the eastern area of Saudi Arabia have reported

comparably lower rates of 1 in 43,000 (6,7).

In the United States, the estimated reported

incidence is 1 in 100,000 (8);

however, a previous analysis has suggested that the actual

prevalence may be ≥10 times this estimate, most likely because of

underdiagnosis (8). In Norway, a

study reported a prevalence of 1 in 6,400 (9), whereas surveys in Ireland and Germany

have reported incidences of ~1 in 65,000 and 1 in 17,800 births,

respectively (5,10).

Clinical presentation and complications

The clinical presentation of HCU spans ocular,

skeletal, neurologic and thromboembolic complications (11–15)

and often differs between pediatric and adult patients, influenced

by the severity of enzyme deficiency and responsiveness to therapy

(16,17).

Thromboembolism is a life-threatening complication

of homocysteine accumulation. Hyperhomocysteinemia damages the

vascular endothelium, causing oxidative stress, inflammation and

endothelial dysfunction, which leads to platelet activation and

coagulation cascade dysregulation, markedly increasing the risk of

arterial and venous thrombosis. Furthermore, homocysteine impairs

nitric oxide production, reducing vasodilation and contributing to

vascular stiffness, leaving patients at an increased risk of

developing deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE),

myocardial infarction and stroke, even at a young age (11,12).

An ocular complication of hyperhomocysteinemia is

ectopia lentis (eye lens dislocation). Elevated homocysteine levels

interfere with collagen cross-linking, thus disrupting the normal

connective tissue integrity of the zonular fibers, which are

fibrillin-rich structures that anchor the lens within the eye,

leading to ectopia lentis. The displaced lens impairs vision and

predisposes the patient to secondary complications, such as myopia,

glaucoma, retinal detachment and eventual permanent vision loss.

Ectopia lentis typically develops in early childhood and is often

bilateral (13).

In the same context, impaired collagen cross-linking

and connective tissue integrity lead to impaired bone matrix

formation that resembles the features of Marfanoid body habitus,

such as long limbs, scoliosis and pectus deformities, as well as

osteopenia or osteoporosis, and increases the risk of fractures.

These skeletal manifestations are typically more evident during

growth spurts in childhood and adolescence (14).

Neurological complications occur because HCU induces

oxidative stress, impairs methylation processes that are important

for neurotransmitter synthesis and damages the vascular

endothelium, thereby increasing the risk of cerebral microvascular

injury and stroke. This can result in developmental delays, mental

disability, seizures and motor dysfunction during childhood. In

adolescents and adults, untreated disease may manifest as

behavioral disorders, psychiatric symptoms such as depression,

anxiety and psychosis, or cognitive decline (15).

In pediatric patients, developmental delay, failure

to thrive and hypotonia are the earliest signs. Intellectual

disability is commonly detected in untreated children in

combination with behavioral disorders. Ectopia lentis appears

within the first 10 years of life and is usually associated with

severe myopia or glaucoma, while musculoskeletal anomalies can

emerge during growth. Children may also experience seizures or

exhibit a clumsy gait due to neurological disorders (16).

In adults, especially those with delayed treatment

during childhood, thromboembolic events such as DVT, PE and stroke

frequently predominate, even in the absence of known risk factors.

Psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety and psychosis can

also show delayed manifestations in adults with low treatment

responsiveness, who may have impaired intellectual or physical

signs (17).

Molecular background of HCU

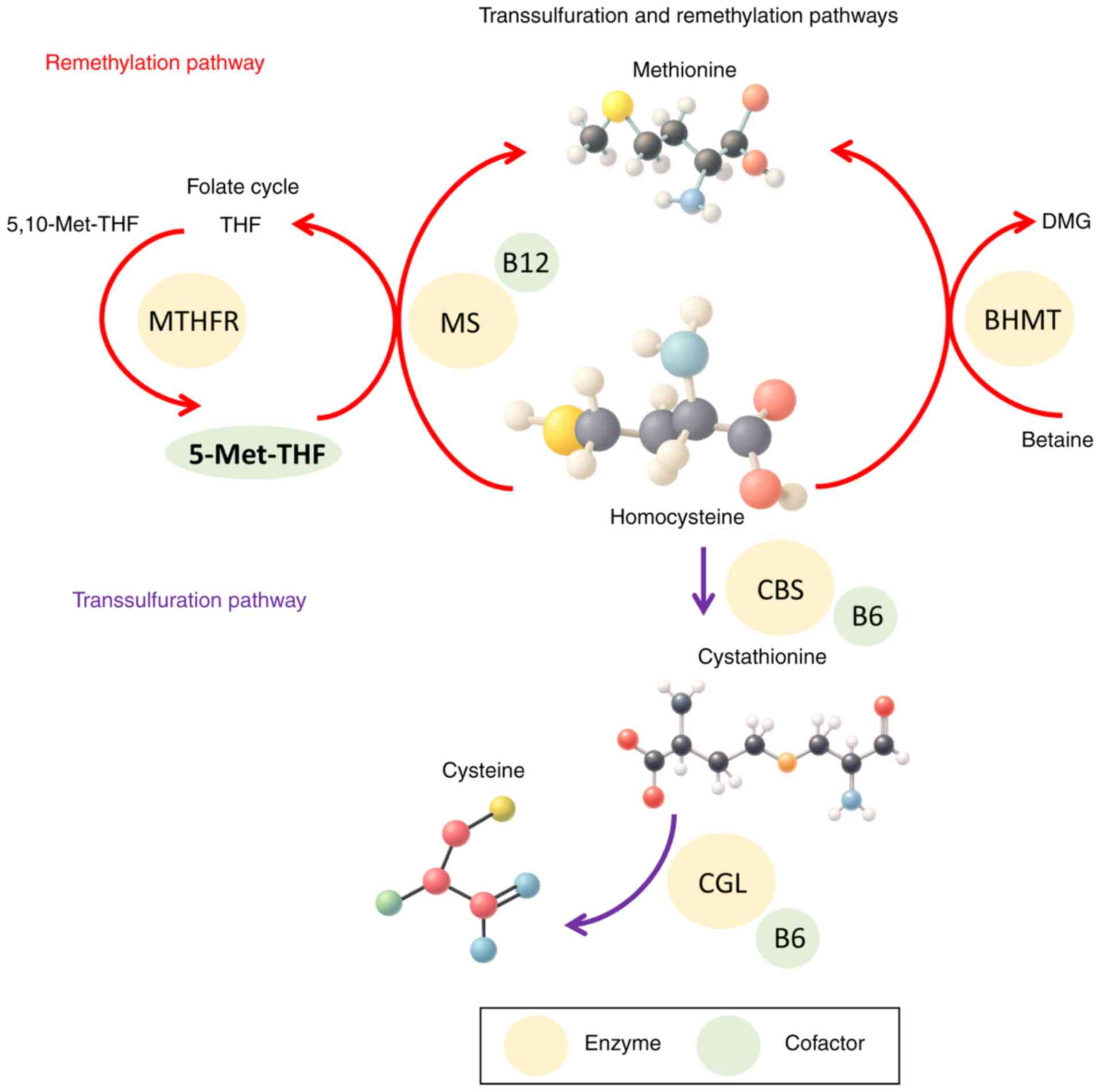

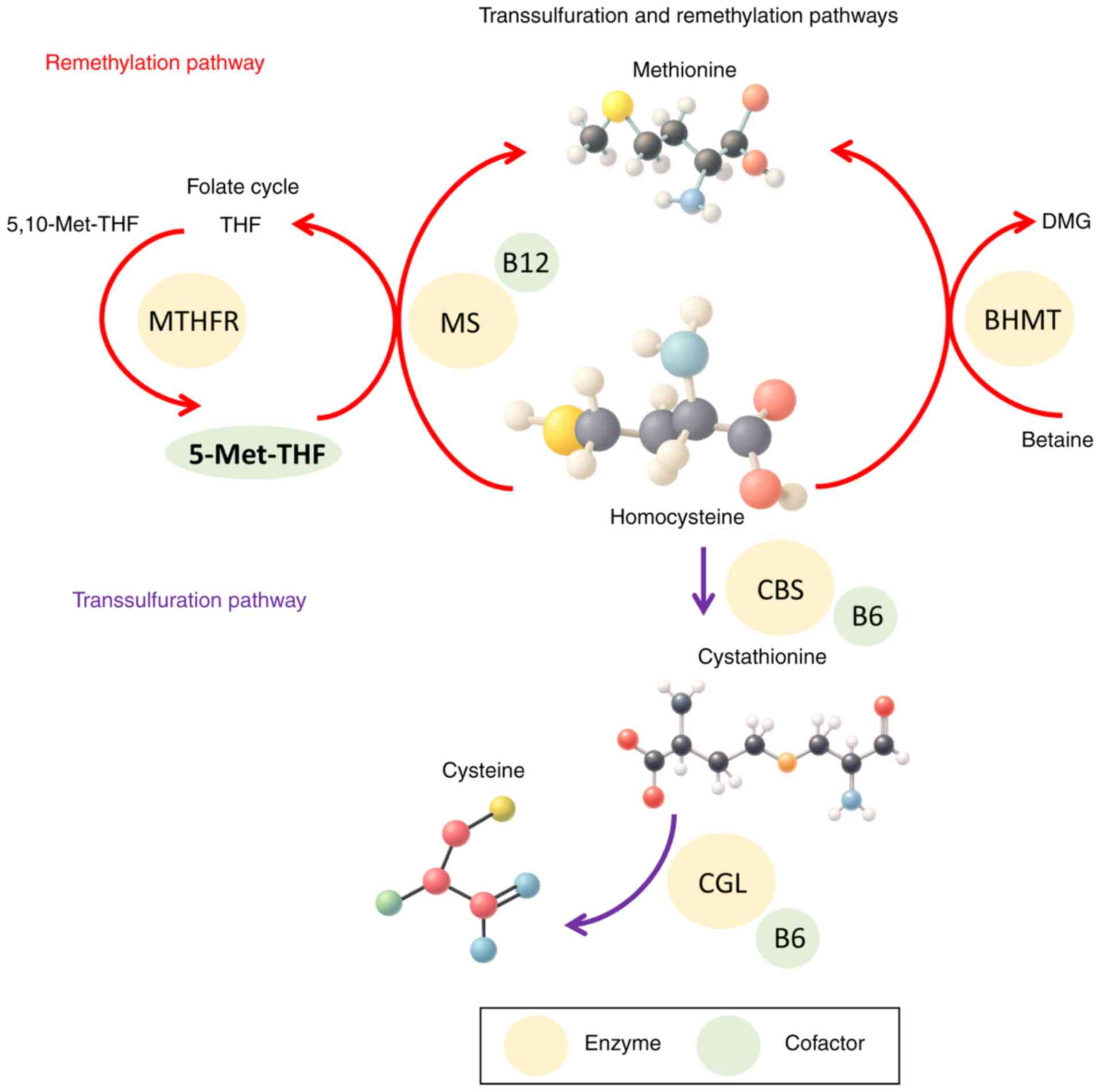

Transsulfuration pathway

The transsulfuration pathway is a hepatic pathway

that facilitates the conversion of homocysteine into cysteine to

detoxify excess homocysteine, and contributes to the synthesis of

glutathione, taurine and coenzyme A, which are important as

antioxidants, for bile acid metabolism and for energy production

(18). The transsulfuration

pathway starts with the CBS enzyme, which catalyzes the conversion

of homocysteine and serine into cystathionine, using pyridoxal

5′-phosphate (PLP), the active form of pyridoxine, as a cofactor.

Afterwards, cystathionine γ-lyase (CGL) breaks down cystathionine

into cysteine, α-ketobutyrate and ammonia. Absolute deficiency or

malfunction of CBS disrupts this pathway, leading to elevated blood

and urine levels of homocysteine and methionine, and reduced

cysteine levels (18).

CBS mutations show genotype-phenotype variability,

influencing the severity of the disease and the responsiveness to

pyridoxine therapy. High-dose B6 supplementation may be beneficial

in the case of partial CBS activity to enhance residual enzyme

function, while total enzyme deficiency requires a

methionine-restricted diet, cysteine-supplemented diets and

betaine, folate and B12 supplementation to promote alternate

remethylation pathways (19,20).

Remethylation pathway

The remethylation pathway works in parallel with the

transsulfuration pathway to normalize plasma homocysteine levels,

especially in the brain where the transsulfuration pathway is

inactive. In this reaction, homocysteine is remethylated to

methionine, which is necessary for protein synthesis, through

catalysis by MS, which requires B12 as a cofactor and employs

5-methyltetrahydrofolate produced by MTHFR as the methyl group

donor (21).

Another hepatic remethylation route involves the

enzyme betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT), which uses

betaine as a methyl donor to remethylate homocysteine into

methionine. The BHMT pathway provides an alternative route for

homocysteine metabolism in cases of folate or B12 deficiency or

genetic disorders that affect the primary route (22).

These interrelated transsulfuration and

remethylation pathways are summarized in Fig. 1, which illustrates the metabolic

conversion of homocysteine and the key cofactors involved.

| Figure 1.Molecular pathways of homocysteine

metabolism. The figure illustrates the normal transsulfuration and

remethylation pathways of homocysteine metabolism, as well as the

folate cycle. Key enzymes include CBS, MS, MTHFR and BHMT.

Important cofactors such as pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6),

folate (5-Met-THF) and methylcobalamin (vitamin B12) are indicated.

Substrates and intermediates shown include homocysteine,

methionine, cystathionine, cysteine, 5,10-Met-THF and DMG. THF,

tetrahydrofolate; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MS,

methionine synthase; DMG, dimethylglycine; BHMT,

betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase; CBS, cystathionine

β-synthase; CGL, cystathionine γ-lyase; 5-Met-THF,

5-methyltetrahydrofolate; 5,10-Met-THF,

5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate. |

Genetic variant associations

Genetic variants of HCU serve important roles in

determining case severity, response to treatment and clinical

outcomes (23,24). The CBS gene is located on

chromosome 21q22.3 (23). More

than 200 pathogenic mutations have been identified in CBS,

resulting in varying degrees of residual enzyme activity, which

markedly influence both phenotype and clinical expression (24).

The I278T mutation, which is widely prevalent

in Western and Far Eastern populations, has been extensively

studied. Patients homozygous for I278T often retain residual

enzyme activity and respond to B6 therapy, whereas the G307S

mutation, common in Irish and Australian populations, is associated

with a severe phenotype and non-responsiveness to B6 (24–26).

Individuals with partial enzymatic activity tend to

show delayed manifestations, milder laboratory abnormalities and

more favorable clinical outcomes. This genotype-phenotype

association is an important consideration in guiding initial

vitamin B6 therapy and in predicting disease prognosis (25).

Variants of other genes involved in homocysteine

metabolism, such as MTHFR,

5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase

(MTR), MTR reductase (MTRR) and metabolism of

cobalamin associated C, also contribute to homocysteine toxicity.

The MTHFR C677T polymorphism produces a thermolabile enzyme with

reduced activity, leading to mild-to-moderate hyperhomocysteinemia,

especially in the context of low folate levels (27–29).

While not typically causing classical HCU, these variants can

worsen biochemical imbalances in genetically predisposed

individuals (27–29).

Genetic workups, even in asymptomatic individuals,

are valuable for early diagnosis and for predicting vitamin B6

responsiveness (27–29).

Table I summarizes

the key genetic variants associated with classical HCU,

highlighting their impact on enzymatic activity, B6 responsiveness

and clinical severity.

| Table I.Summary of key genetic variants of

CBS and related genes, their geographic prevalence, enzyme

activity, vitamin B6 responsiveness and associated clinical

severity of HCU. |

Table I.

Summary of key genetic variants of

CBS and related genes, their geographic prevalence, enzyme

activity, vitamin B6 responsiveness and associated clinical

severity of HCU.

| Mutation | Geographic

prevalence | B6

responsiveness | Residual CBS

activity | Clinical severity

(phenotypic severity of homocystinuria) |

|---|

| I278T | Western (Europe and

North America) and Far Eastern (China) | Responsive | Partial | Mild to

moderate |

| G307S | Ireland and

Australia | Non-responsive | Minimal to

none | Severe, early

onset |

| Other CBS

variants | Global | Variable | Variable | Variable |

| (p.R125Q,

p.R266K, p.R336C and c.1224-2A>C) |

|

|

|

|

| MTHFR

C677T | Global (especially

Europe and Asia) | No (not classical

HCU) | Thermolabile

MTHFR | Mild to moderate

hyperhomocysteinemia |

Diagnosis of HCU

The diagnosis of HCU involves a combination of

clinical evaluation, biochemical testing and molecular genetic

analysis. Early and accurate diagnosis is important because prompt

treatment can improve the prognosis of HCU and prevent irreversible

complications (16,17).

Symptoms and phenotypic features

HCU usually presents with a wide range of clinical

symptoms that affect multiple organs. Ocular complications,

including ectopia lentis, myopia, astigmatism, glaucoma and

blindness, are the earliest and most common manifestations,

affecting 90% of poorly managed individuals (13–17).

In the early childhood growth phase, skeletal

deformities are common, including marfanoid body habitus, long

limbs, scoliosis, pectus deformities, genu valgum and severe

osteoporosis, which predispose patients to recurrent bone fractures

(14). Neurological deficits and

developmental delays commonly occur in the early years of life, are

noticed as intellectual disabilities and may progress to repeated

seizures (17).

Thromboembolic events, such as DVT, PE and stroke,

are the most serious complications that may affect both adolescents

and adults. The severity of clinical presentation is markedly

dependent on the degree of enzyme deficiency and therapeutic

responsiveness (11,12).

Biochemical diagnosis

Plasma homocysteine level

Plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) is a sensitive

diagnostic biomarker for the primary diagnosis and therapeutic

monitoring of HCU. Impaired metabolism of homocysteine to

cystathionine results in elevated tHcy blood levels of >100

µmol/l compared with <15 µmol/l in healthy individuals (30).

Plasma tHcy levels combined with elevated methionine

levels can distinguish CBS deficiency from other

homocysteine-related disorders, such as remethylation defects,

which usually present with high tHcy levels but low methionine

levels. Furthermore, tHcy levels also guide clinical decisions

during diagnostic B6 challenge tests, in which a notable drop in

homocysteine confirms B6-responsive HCU (30).

Plasma methionine levels

Decreased homocysteine metabolism leads to a buildup

of methionine, with levels ranging from 60 to 100 µmol/l. This

concurrent elevation of tHcy and methionine can distinguish

classical HCU from hyperhomocysteinemia caused by other

remethylation pathway disorders, such as MTHFR deficiency or

cobalamin metabolism malfunction, which lead to elevated tHcy

levels while maintaining normal methionine levels. In patients on

methionine-restricted diets, the normalization of plasma methionine

and tHcy levels indicates effective metabolic control. The B6 trial

also identifies B6-responsive individuals who show partial

improvement in methionine levels (17).

Urinary homocysteine

Measurement of urinary homocysteine levels provides

evidence for the diagnosis of classical HCU, particularly in

limited-resource settings where plasma tHcy testing is not

available. In CBS deficiency, elevated plasma homocysteine levels

exceed the renal reabsorption capacity, leading to increased renal

excretion of both free and tHcy. Although the urinary homocysteine

level is less precise than the plasma tHcy test, it is used as an

initial screening test, especially in symptomatic children.

However, elevated urinary homocysteine levels can also be detected

in other homocysteine metabolism disorders, and may vary with

hydration status and renal function (31).

Vitamin B12, folate and methylmalonic

acid (MMA)

Being cofactors in the remethylation pathway that

converts homocysteine to methionine, deficiencies in vitamin B12 or

folate can lead to elevated plasma tHcy levels but are not

indicative of CBS deficiency. Thus, measuring serum B12 and folate

levels rules out nutritional or acquired causes of

hyperhomocysteinemia (32,33).

Elevated MMA levels suggest functional B12

deficiency or disorders of cobalamin metabolism, which may be

associated with elevated tHcy levels. However, in classical HCU,

MMA levels are typically normal, which helps to exclude

remethylation disorders from the potential diagnosis and indicates

that the elevated homocysteine level is due to transsulfuration

pathway impairment rather than defective remethylation (34).

Molecular genetic testing

Genetic testing using next-generation sequencing

that utilizes the CBS gene, or whole-exome sequencing in

asymptomatic cases, is a decisive tool for confirming the diagnosis

of classical HCU, uncovering the underlying CBS gene

mutations responsible for CBS deficiency, as well as predicting B6

responsiveness and guiding treatment decisions (35,36).

Over 190 CBS gene mutations with clinically

significant genotype-phenotype associations have been isolated. The

common p.I278T mutation is often associated with partial or

full responsiveness to B6 therapy, whereas p.R125Q, p.G307S

and p.R266K mutations are associated with non-responsiveness

and severe symptoms (37).

Enzyme activity assays

CBS activity assays performed on cultured skin

fibroblasts or fresh liver biopsy samples evaluate the functional

capacity of CBS, which is typically absent or markedly reduced in

HCU. Enzymatic activity testing assists in distinguishing between

the B6-responsive and non-responsive forms of CBS, as residual

activity may be enhanced by the addition of PLP in vitro.

The use of enzyme assays has lost its applicability in clinical

practice as it requires an invasive tissue sampling technique, a

long turnaround time and challenging interpretation in cases with

residual activity (36,38).

Treatment

Conventional therapies

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation

High-dose B6 therapy is the first line of treatment

for patients with residual CBS enzyme activity. B6 is converted

into PLP, an important cofactor for the enzymatic activity of CBS.

Genotypes such as I278T typically retain fractional enzyme

functions and respond satisfactorily to B6 therapy (39,40).

Notably, a study involving European and sub-Saharan populations has

identified multiple haplotypes of the CBS gene, suggesting

that an ongoing mutational process may contribute to the diminished

long-term effectiveness of pyridoxine therapy in sustaining optimal

clinical outcomes (39). By

contrast, null mutations in G307S result in no functional

CBS enzymes and are usually pyridoxine-non-responsive; the CBS

c.1224-2A>C mutation is a null, splice-site variant

associated with vitamin B6 non-responsiveness (41). Other mutations such as

p.R336C alter the molecular properties of CBS, leading to a

severe HCU phenotype unresponsive to B6 therapy (42).

Comprehensive genotyping and in vitro enzyme

activity assays are not available in numerous clinical settings.

Therefore, clinicians rely on empirical pyridoxine trials without

accurately predicting the outcomes. A pyridoxine trial is performed

in all newly diagnosed cases, typically starting at 100–500 mg/day,

followed by therapeutic monitoring of plasma tHcy and methionine

levels. Patients able to achieve tHcy levels <50 µmol/l with B6

therapy alone are classified as responsive and usually exhibit

milder clinical presentations (17).

B6 therapy faces some challenges, as not all

pyridoxine-responsive patients demonstrate clinical improvement

with B6 supplementation. This may be due to additional confounders

such as epigenetics, coexisting polymorphisms and nutrient status.

Furthermore, some patients exhibit only a partial response and may

continue to develop further complications. These patients often

require combination therapy, and their classifications can be

ambiguous (17). Additionally,

long-term adherence to B6 therapy may be challenging because of

rising concerns regarding peripheral neuropathy caused by chronic

high-dose use (43).

Dietary methionine restriction

A lifelong methionine-restricted diet remains the

basic strategy for managing HCU due to CBS gene mutations.

The diet aims to reduce methionine accumulation while ensuring

adequate nutrition using methionine-free nutritional formulas. This

approach requires careful follow-up of plasma amino acid levels to

maintain metabolic control, prevent protein malnutrition and ensure

the fulfillment of demands for normal growth, especially in

pediatric patients (44).

Although a methionine-restricted diet is effective

in lowering plasma tHcy levels, it poses a long-term compliance

challenge because of the poor palatability of dietary formulas

(45). In addition, dietary

restrictions alone may not be sufficient to prevent disease

complications and may require adjunctive therapies (44,45).

Numerous preclinical trials in animal models have

attempted to overcome the challenges related to dietary

restrictions. Using a mouse model, CDX-6512, an engineered

orally-stable methionine γ-lyase (MGL), was administered following

a high-protein meal and led to a dose-dependent ability to locally

degrade methionine in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), suppressing

plasma methionine and homocysteine (46). Another experimental model by

Perreault et al (47) used

a bolus dose of an engineered probiotic E. coli Nissle

strain to degrade methionine in the GIT. The resulting SYNB1353

strain metabolized methionine in mice, non-human primates and

humans, resulting in lower plasma methionine levels.

Betaine supplementation

Betaine, also known as trimethylglycine, is a

commonly used adjunctive therapy for B6-unresponsive patients with

HCU that acts as a methyl donor in the hepatic BHMT remethylation

pathway (48). In a study

enrolling patients with B6-unresponsive HCU, betaine administration

resulted in individual mean reductions in plasma tHcy levels

ranging from 47.4 to 105.0 µmol/l (49). Another study involving healthy

subjects showed that betaine supplementation of 6 g/day for 3 weeks

significantly reduced homocysteine levels (P=0.030) (50). A study by Lu et al (51) reported a 10% reduction in the

plasma homocysteine concentration when using a combination of

betaine and low-dose B vitamins: 400 µg folic acid, 8 mg vitamin

B6, 6.4 µg vitamin B12 and 1 g betaine.

However, prolonged betaine therapy of >100

mg/kg/day in patients with inadequate dietary methionine

restriction led to notable hypermethioninemia-related adverse

events (52), while another study

reported marked elevations in total cholesterol levels with betaine

supplementation, necessitating close monitoring in patients at risk

of cardiovascular disease (53).

Folate and B12 supplementation

Folate and B12 are important drugs in HCU management

protocols, particularly in patients with MTHFR, MTR and

MTRR mutations. These vitamins serve important roles in the

remethylation of homocysteine to methionine (54). The active form of folate,

5-methyltetrahydrofolate, donates a methyl group to homocysteine,

converting it to methionine. This reaction is catalyzed by MS with

methylcobalamin, the active form of vitamin B12, as a cofactor.

Insufficient folate and B12 supplies impair this pathway, leading

to elevated tHcy levels (55). A

randomized clinical trial by Kok et al (56) demonstrated marked reductions in

tHcy levels in elderly participants consuming 400 g folic acid and

500 g vitamin B12 daily over 2 years.

Limitations and challenges of

conventional therapies

Despite being the basis of HCU management,

conventional therapies have non-negligible limitations, including

variability in patient responsiveness to B6. Adherence to

low-methionine diets is often difficult, affecting metabolic

control, even with strict diet control and vitamin supplements.

Numerous patients fail to meet the desired tHcy levels, leaving

them at risk of complications. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes

of current interventions are inconsistent and there is limited

capacity to reverse established complications (17,43–45).

Novel treatment approaches

Mechanistic and structural studies on CBS have

provided the basis for emerging therapeutic concepts (57–62).

Building on these and on prior reviews, such as that by Majtan

et al (63), this section

emphasizes treatment developments since 2023 and practical

translational considerations across enzyme replacement, gene- and

proteostasis-directed strategies.

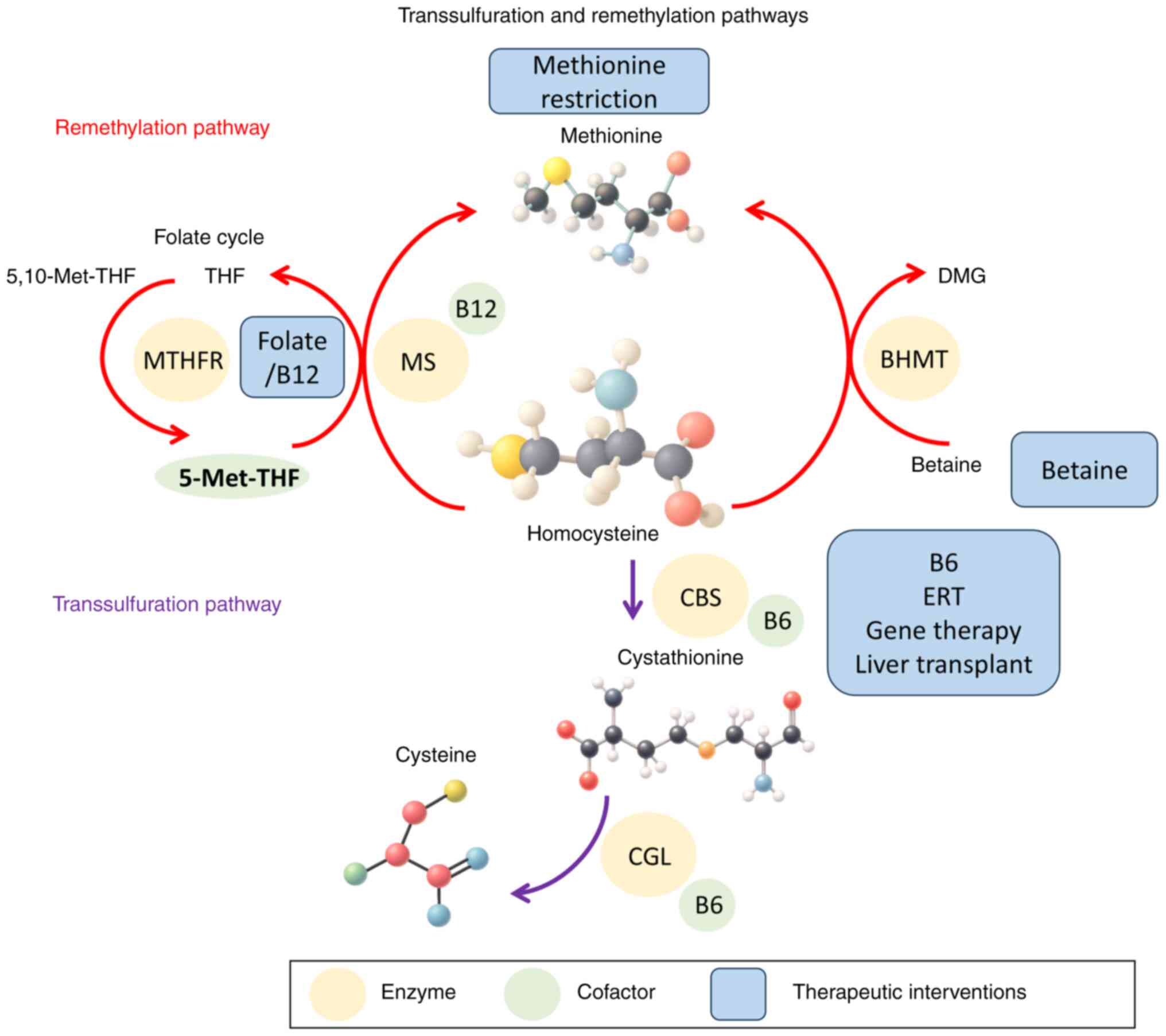

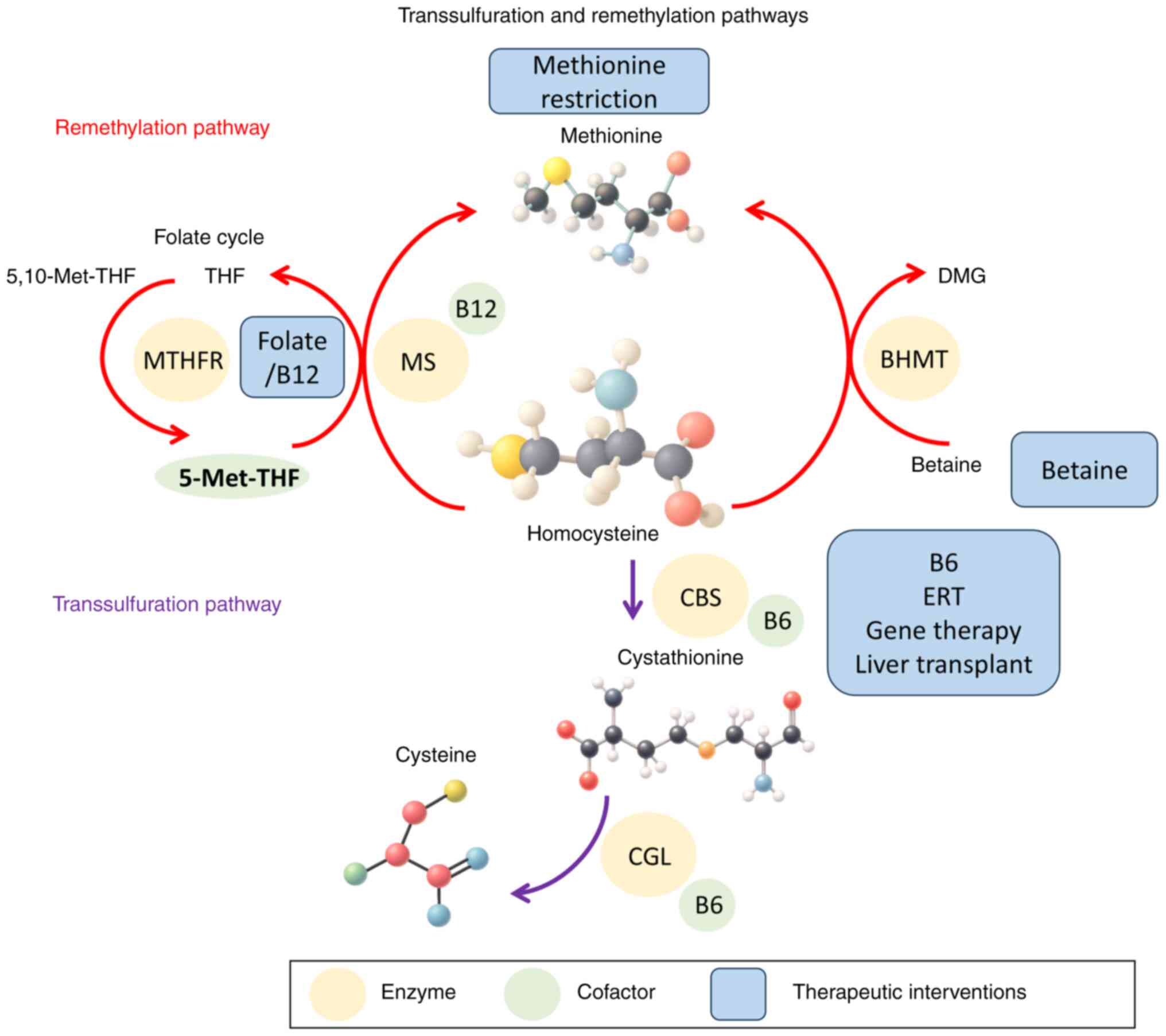

Fig. 2 provides an

integrated overview of these molecular pathways with annotated

therapeutic targets and intervention points.

| Figure 2.Therapeutic interventions and

intervention points in homocysteine metabolism. The figure presents

the molecular pathway of homocysteine metabolism with annotated

sites of action for conventional and novel therapies, including

dietary modification, vitamin supplementation, betaine therapy,

ERT, gene therapy and orthotopic liver transplantation. THF,

tetrahydrofolate; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MS,

methionine synthase; DMG, dimethylglycine; BHMT,

betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase; CBS, cystathionine

β-synthase; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; CGL, cystathionine

γ-lyase; 5-Met-THF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; 5,10-Met-THF,

5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate. |

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT)

Human CBS is a complex multidomain enzyme that

requires PLP for its activity and binds to a heme group that serves

a regulatory role in its enzyme activity. The CBS protein is

composed of four identical subunits comprising 551 amino acids.

Each subunit consists of three domains, with the N-terminal domain

containing the heme-binding site. In this region, the heme is

linked by cysteine at position 52 and histidine at position 65

(57).

ERT is being developed as a mutation-agnostic

approach for CBS deficiency that delivers functional enzymes

directly, bypassing reliance on residual endogenous activity. While

ERT can normalize biochemistry quickly, the need for chronic

administration and the typical costs and immunogenicity risks of

biologics remain practical challenges for widespread adoption

(58).

i) Pegtibatinase. Pegtibatinase, also known as OT-58

or TVT-058, is a recombinant human CBS catalytic core (amino acids

1–413) that has been modified with the addition of polyethylene

glycol (PEG) and lacks the CBS autoinhibitory regulatory domain,

yielding a constitutively active, predominantly dimeric enzyme.

This modification stimulates the catalytic activity of the enzyme,

rendering it predominantly in a dimeric state (58). To boost pegtibatinase stability and

minimize unwanted protein aggregation, a cysteine-to-serine

substitution at position 15 is introduced to prevent the formation

of interdimer disulfide bonds. The enzyme is also chemically

modified by PEGylation, in which five PEG chains of 20 kDa each are

attached to each CBS subunit. This extends the circulation

half-life by 10-fold, making the PEGylated form more suitable for

therapeutic use in HCU than the unmodified enzyme (59).

In the phase 1/2 COMPOSE study, pegtibatinase

demonstrated promising tolerability and a safety profile with only

two incidents of mild injection site urticaria that resolved upon

temporary dose interruption and subsequent dose titration. Using a

subcutaneous dose of 1.5 mg/kg twice weekly of pegtibatinase

achieved a 67.1% mean relative reduction in tHcy levels from

baseline (97 to 32 µM) at follow-up intervals of 6, 8, 10 and 12

weeks, maintaining tHcy levels below the clinically meaningful

threshold of ≥100 µM (60). A

preclinical study in CBS-deficient animal models has demonstrated

that pegtibatinase ameliorated related complications such as ocular

and skeletal manifestations, decreased facial alopecia, and

enhanced liver metabolism of glucose and lipids (61).

ii) Pegtarviliase. Pegtarviliase, also known as

AGLE-177, is an engineered CGL variant (CGL-ILMDRGVS) with markedly

increased affinity for homocysteine compared with wild-type CGL. It

contains eight missense mutations, referred to as the CGL-ILMDRGVS

construct, and exhibits a 60-fold increased affinity for

homocysteine compared with the wild-type human CGL enzyme (62). Furthermore, pegtarviliase shows an

enhanced capability for degrading multiple forms of homocysteine

compared with wild-type CGL, along with improved stability and

circulation time, potentially resulting in a more comprehensive

reduction in tHcy levels (62).

A preclinical study of pegtarviliase in mice using

subcutaneous doses of 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg twice weekly between

postnatal days 10 and 70 reported a marked improvement in 30-day

survival rates, at >75 vs. <20% in the treated and control

groups, respectively. The treated mice also showed resolution of

liver steatosis and alopecia. Furthermore, a dose of 10 mg/kg led

to an ~43% reduction in plasma tHcy levels and an 87% reduction in

brain tHcy levels (63).

In a phase 1/2 dose-escalation trial aiming to

assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and efficacy of

pegtarviliase in patients with classical HCU, three cohorts of

participants received weekly subcutaneous injections of

pegtarviliase at doses of 0.15, 0.45 and 1.35 mg/kg, respectively

over the course of 4 weeks. A 3-day post-treatment dose-dependent

reduction in tHcy levels of 26.3 and 33.0% was observed in cohorts

1 and 2, respectively. However, some participants in cohort 3

experienced injection site reactions and increased tHcy levels,

which can be explained by the development of anti-drug antibodies.

The study highlighted the promising tolerability and efficacy of

pegtarviliase at low doses, with a clear need for modified clinical

strategies to resolve the immunogenicity issues (64). As of 2023, Aeglea BioTherapeutics,

Inc., announced the exploration of strategic alternatives for the

pegtarviliase program following interim phase 1/2 results (65), which ultimately led to the

discontinuation of its clinical development in 2024.

iii) CDX-6512. CDX-6512 is an investigational

modified MGL enzyme that is specifically engineered to maintain

stability and activity in the GIT. In 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration granted CDX-6512 the ‘orphan drug designation’ for

the treatment of HCU. Using artificial intelligence and machine

learning, 12 iterative rounds of enzyme evolution were performed,

and >27,000 variants were screened for activity under simulated

gastric and intestinal conditions. The resulting enzyme exhibited

high resistance to deactivation by gastric pH and other enzymes

(46).

In a preclinical study using the Tg-I278T

CBS−/−mouse model of HCU, an oral dose of 148

mg/kg CDX-6512 administered after a high-protein meal led to an

almost 50% reduction in plasma tHcy levels after 4 h. Plasma

methionine levels also declined in a non-significant dose-dependent

manner, with up to a one-third decrease at the highest dose

(66).

A study in healthy non-human primates that received

a high-protein meal followed by an oral dose of 370 mg/kg CDX-6512

treatment led to a statistically significant, dose-dependent

reduction in plasma methionine levels, demonstrating the

effectiveness of the enzyme in breaking down dietary methionine in

a physiologically-similar model to humans (46). In the same preclinical program

using Tg-I278T CBS−/− mice, daily oral

administration of CDX-6512 with a high-protein meal over 2 weeks

effectively maintained baseline plasma tHcy levels. By contrast,

untreated controls showed a 39% increase in homocysteine levels,

suggesting that homocysteine levels can be sustained with long-term

CDX-6512 treatment (46). In 2024,

the program was acquired and rebranded as SYNT-202 by Syntis Bio,

with continued preclinical optimization focused on gut-restricted

methionine degradation; no human data under the new designation

have been disclosed at present (67).

Limitations and challenges of ERT

Although ERT offers mutation-independent metabolic

control, injectable agents such as pegtibatinase face lifetime

adherence and immunogenicity hurdles, and oral agents such as

SYNT-202 still require durable efficacy and safety data;

cost-of-goods and access considerations further suggest that ERT

will likely complement, rather than fully replace, diet and

vitamin-based care (58–61).

Gene therapy

Gene therapy offers a potential one-time treatment

for CBS deficiency by restoring intrinsic CBS function at the

genetic level. The strategy delivers a functional CBS gene to the

liver, via viral or non-viral vectors, to achieve sustained

metabolic correction.

Adeno-associated virus serotype rh.10

(AAVrh.10)-CBS-based gene therapy

AAVrh.10-CBS uses an AAVrh.10 vector to deliver a

functional human CBS gene under a cytomegalovirus early

enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter, targeting hepatocytes involved

in homocysteine metabolism. In the CBS-deficient mouse model I278T,

a single intravenous dose reduced plasma tHcy levels by ~97% within

1 week and sustained an ~81% reduction at 1 year from

administration, with observed reversal of alopecia, skeletal

defects and abnormal fat distribution (68). Pre-existing neutralizing antibodies

to AAVrh.10 appear to be less prevalent than those to AAV2 or AAV8,

supporting the suitability of AAVrh.10 for liver-directed

applications (69). Furthermore,

the durability of liver-directed AAV expression observed in a human

hemophilia B gene therapy trial (70) suggests the potential for long-term

transgene persistence in clinical applications.

Minicircle DNA-CBS gene therapy

Minicircular DNA vectors, which lack bacterial

backbone sequences, can more efficiently enhance transgene

expression and reduce innate immune activation compared with

plasmids. Foundational work on vector design and dosing has also

highlighted safety principles to minimize hepatic genotoxicity in

gene-delivery programs (71).

In CBS-deficient mice, a single liver-targeted

injection of the minicircle CBS construct MC.P3-hCBS reduced plasma

homocysteine levels by ~50% within 1 week, restored hepatic CBS

activity ~34-fold and sustained metabolic correction for >6

months (72).

Advantages, limitations and challenges

of gene therapy

Gene therapy directly addresses the genetic cause of

HCU, offering the possibility of durable metabolic correction.

However, immune responses to viral vectors, the dilution of

treatment effects with hepatic growth in children and complex

manufacturing remain key challenges (68–72).

Pharmacological chaperones

Pharmacological chaperones are small molecules that

bind to misfolded CBS proteins, stabilizing their structure and

enhancing catalytic activity. Examples include glycerol,

trimethylamine-N-oxide and dimethyl sulfoxide, which have been

shown to restore activity in certain CBS mutants in cell and animal

models (73,74). Yeast expression systems for human

CBS mutants have also demonstrated that chaperones can promote

proper assembly and tetramerization, supporting mutation-specific

therapeutic potential (75).

S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)

SAM, an allosteric activator of CBS, binds to the

regulatory domain of the enzyme to boost activity (76,77).

A study by Mendes et al (77) demonstrated that ~50% of tested

patients with HCU showed defective SAM activation, often linked to

specific CBS mutations.

Heme arginate

CBS is a heme-dependent enzyme; some CBS gene

mutations impair heme binding. Heme arginate can stabilize these

variants and restore heme-binding activity in cell models (78). A study by Melenovská et al

(78) showed that administration

of heme arginate restored heme binding, improved tetramer formation

and enhanced catalytic activity of the CBS enzyme in several

B6-resistant mutants.

Advantages and limitations of

pharmacological chaperones

Chaperones may complement diet and gene therapy, but

most remain unvalidated in clinical trials. Mutation-specific

responsiveness suggests that genotype-guided therapy may be

required (73–78).

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs)

Proteasome inhibition can stabilize partially active

but misfolded CBS proteins. Bortezomib, an oncology drug, increased

hepatic CBS activity >20-fold and reduced plasma tHcy levels by

97% in a p.R266K mouse model (79–81).

Carfilzomib has shown similar biochemical benefits in preclinical

HCU models, although its long-term safety remains yet to be fully

elucidated (82).

Advantages and limitations of PIs

Potential risks of PIs include systemic proteasome

suppression. Liver-targeted delivery strategies and dose

minimization are being explored to mitigate toxicity (80–82).

Probiotic treatment (SYNB1353)

SYNB1353 is an engineered E. coli Nissle

strain expressing methionine γ-lyase to degrade dietary methionine.

In preclinical models, it reduces plasma homocysteine and

methionine levels without adverse events (83). A phase 1 trial in healthy

volunteers showed promising tolerability and dose-dependent

methionine reduction (84). A

phase 2 study in classical HCU (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier,

NCT05651054) is ongoing, with efficacy data pending.

Orthotopic liver transplantation

(OLT)

OLT has emerged as the only definitive treatment for

severe pyridoxine-non-responsive HCU. Multiple case reports have

demonstrated complete metabolic normalization following OLT. A case

report by Lin et al (85)

described a 24-year-old patient with HCU with notable

complications, including cerebellar infarctions and hypertension,

who underwent a liver transplant, after which their metabolic

control normalized without dietary restrictions. Another case

report described a patient with HCU who demonstrated

post-transplant normalized homocysteine and methionine levels at

the age of 4 years and remained stable for 6 years, indicating the

resolution of HCU. The patient had no complications before the

transplantation, highlighting the potential of early liver

transplantation as a curative strategy for HCU (86).

A retrospective genetic analysis uncovered 18 CBS

variants in 13 patients diagnosed with classic HCU between 10 days

of age and 14 years of age, all of whom exhibited elevated

methionine and tHcy levels. Three B6 non-responders underwent liver

transplantation at the ages of 3, 8 and 8 years, and achieved

normalized methionine and homocysteine levels within a week

post-transplant (87).

Although liver transplantation offers a curative

approach for B6 non-respondents, it carries notable challenges,

including surgical risks, the need for prolonged immunosuppression

and limited donor availability. Additionally, OLT does not reverse

existing complications, and early diagnosis is important to

optimize outcomes (85–87).

Personalized medicine and biomarkers in HCU

management

The integration of genetic and metabolic profiling

allows physicians to tailor treatment according to the molecular

profile of a patient (25,40). Patients with p.I278T mutations may

exhibit variable responses to B6, whereas those with p.R125Q or

p.R266K mutation variants require different therapeutic approaches

(25,40,81).

Early identification of these mutations through genetic workups not

only supports accurate diagnosis but also allows for prompt and

tailored treatments, as summarized in Table II, which compares treatment

modalities, their mechanisms, genotype associations, effectiveness

and limitations (17,38).

| Table II.Comparison of treatment modalities in

homocystinuria. |

Table II.

Comparison of treatment modalities in

homocystinuria.

| Treatment

modality | Mechanism of

action | Genotype

association | Effectiveness |

Limitations/challenges |

|---|

| Pyridoxine (vitamin

B6) | Cofactor for CBS

enzyme; enhances residual CBS activity. | Effective primarily

in CBS mutations with residual enzymatic activity such as

p.Ile278Thr. | Highly effective in

pyridoxine-responsive genotypes; reduces homocysteine and improves

prognosis. | Not effective in

pyridoxine-non-responsive genotypes; responsiveness must be

tested. |

| Betaine | Remethylates

homocysteine to methionine via betaine-homocysteine

methyltransferase, bypassing the CBS pathway. | Effective in both

responsive and non-responsive CBS genotypes. | Reduces plasma

homocysteine levels in non-responsive patients. | Can increase

methionine to toxic levels; requires careful monitoring. |

|

Methionine-restricted diet | Limits precursor

amino acid (methionine) to reduce homocysteine production | Universally

applied, regardless of genotype. | Reduces total

homocysteine load; supportive in both responsive and non-responsive

cases. | Difficult

compliance, especially in older children and adults; risk of

nutritional deficiency. |

| Folic acid and

B12 | Cofactors in

remethylation of homocysteine to methionine. | Useful in

remethylation defects and cases with mild elevation in

homocysteine. | Beneficial in

methylenetetrahy-drofolate reductase and cobalamin defects; used

adjunctively in patients with CBS mutations. | Not curative for

CBS deficiency; requires a combined approach |

| Experimental enzyme

replacement therapy | Supplements

defective or absent CBS enzyme. | Under investigation

for CBS-deficient genotypes. | Potential for

correcting enzymatic deficiency directly. | Not yet clinically

available; challenges in enzyme delivery and immunogenicity. |

| Experimental gene

therapy | Introduces

functional CBS gene into host cells. | Targeted at

CBS-null or severe mutation genotypes. | Preclinical studies

show promise; long-term correction potential. | Experimental;

delivery vectors and sustained expression are hurdles. |

| Liver

transplantation | Provides normal CBS

activity from the liver of the donor. | Effective in

CBS-deficient patients with severe mutations. | Can normalize

homocysteine metabolism; curative in some cases. | Invasive; limited

to severe, refractory cases; lifelong immunosuppression

required. |

Metabolic biomarkers are important tools for

therapeutic monitoring and follow-up of disease progression

(17,30). The plasma tHcy level is the primary

biochemical marker for assessing metabolic control in HCU (17,30).

However, novel biomarkers such as cystathionine, methionine and SAM

are being investigated for their potential to provide a more

accurate view of disease status (30,55).

Stratifying patients according to their residual CBS activity or

proteostatic disparities may help guide the use of emerging

therapies (73,74,81,82).

Limitations of the present review

The present narrative review synthesizes

peer-reviewed literature, clinical trial data, and select pipeline

updates on metabolic and molecular therapies for HCU. As a

narrative rather than systematic review, study selection and

emphasis in the present review may reflect some degree of author

judgment. Furthermore, regional differences in prevalence, genotype

distribution and patterns of consanguinity, together with

heterogeneity in CBS mutations and pyridoxine responsiveness, may

limit the generalizability of certain therapeutic approaches or

outcome expectations across diverse patient populations. Several

discussed interventions are supported mainly by early-phase or

preclinical data, limiting conclusions on long-term safety and

efficacy. Additionally, some pipeline updates are based on press

releases or conference reports, which may change as further

evidence emerges. Despite these constraints, the present review

provides a timely, integrated synthesis of current and emerging

therapeutic strategies, contextualized with the latest clinical and

translational developments through early 2025.

Conclusion

HCU is an underrecognized metabolic disorder

associated with severe multi-organ complications. Timely diagnosis

and individualized therapy are important to prevent long-term

morbidity and improve patient outcomes. Advances in molecular

genetics have deepened the current understanding of disease

pathophysiology and provided the basis for innovative therapeutic

strategies.

By integrating updates from therapeutic pipelines

with clinical considerations and emphasizing how regional and

genetic variability shape the applicability of emerging treatments,

the present review offers a novel and clinically-oriented

synthesis. It underscores both the implications for current

practice and the priorities for future research aimed at

transforming care for individuals with HCU.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AAA was solely responsible for the conception,

design, literature review, writing and revision of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. The author has read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HCU

|

homocystinuria

|

|

CBS

|

cystathionine β-synthase

|

|

MTHFR

|

methylenetetrahydrofolate

reductase

|

|

DVT

|

deep vein thrombosis

|

|

PE

|

pulmonary embolism

|

|

PLP

|

pyridoxal 5′-phosphate

|

|

CGL

|

cystathionine γ-lyase

|

|

MS

|

methionine synthase

|

|

BHMT

|

betaine-homocysteine

methyltransferase

|

|

tHcy

|

total homocysteine

|

|

MMA

|

methylmalonic acid

|

|

MGL

|

methionine γ-lyase

|

|

ERT

|

enzyme replacement therapy

|

|

SAM

|

S-adenosylmethionine

|

|

AAVrh.10

|

adeno-associated virus serotype

Rh.10

|

|

PI

|

proteasome inhibitor

|

|

OLT

|

orthotopic liver transplantation

|

References

|

1

|

Carson NA, Dent C, Field CM and Gaull GE:

Homocystinuria: Clinical and pathological review of ten cases. J

Pediatr. 66:565–583. 1965. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jain M, Shah M, Thakker KM, Rava A,

Pelts-Block A, Ndiba-Markey C and Pinto L: High clinical burden of

classical homocystinuria in the United States: A retrospective

analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 20:372025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schneede J, Refsum H and Ueland PM:

Biological and environmental determinants of plasma homocysteine.

Semin Thromb Hemost. 26:263–279. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Al-Sadeq DW and Nasrallah GK: The spectrum

of mutations of homocystinuria in the MENA region. Genes (Basel).

11:3302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Naughten ER, Yap S and Mayne PD: Newborn

screening for homocystinuria: Irish and world experience. Eur J

Pediatr. 157:S84–S87. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Alsharhan H, Ahmed AA, Ali NM, Alahmad A,

Albash B, Elshafie RM, Alkanderi S, Elkazzaz UM, Cyril PX,

Abdelrahman RM, et al: Early diagnosis of classic homocystinuria in

Kuwait through newborn screening: A 6-year experience. Int J

Neonatal Screen. 7:562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Moammar H, Cheriyan G, Mathew R and

Al-Sannaa N: Incidence and patterns of inborn errors of metabolism

in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, 1983–2008. Ann Saudi Med.

30:271–277. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sellos-Moura M, Glavin F, Lapidus D, Evans

K, Lew CR and Irwin DE: Prevalencecharacteristics, costs of

diagnosed homocystinuria, elevated homocysteine, phenylketonuria in

the United States: A retrospective claims-based comparison. BMC

Health Serv Res. 20:1832020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Refsum H, Fredriksen Å, Meyer K, Ueland PM

and Kase BF: Birth prevalence of homocystinuria. J Pediatr.

144:830–832. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Schnabel E, Kölker S, Gleich F, Feyh P,

Hörster F, Haas D, Fang-Hoffmann J, Morath M, Gramer G, Röschinger

W, et al: Combined newborn screening allows comprehensive

identification also of attenuated phenotypes for methylmalonic

acidurias and homocystinuria. Nutrients. 15:33552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yap S, Naughten E, Wilcken B, Wilcken D

and Boers GH: Vascular complications of severe hyperhomocysteinemia

in patients with homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase

deficiency: Effects of homocysteine-lowering therapy. Semin Thromb

Hemost. 2000:335–340. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kalil MAB, Donis KC, de Oliveira Poswar F,

Dos Santos BB, Santos ÂBS and Schwartz IVD: Cardiovascular findings

in classic homocystinuria. Mol Genet Metab Rep.

25:1006932020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rahman M, Sharma M, Aggarwal P, Singla S

and Jain N: Homocystinuria and ocular complications-A review.

Indian J Ophthalmol. 70:2272–2278. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Weber DR, Coughlin C, Brodsky JL,

Lindstrom K, Ficicioglu C, Kaplan P, Freehauf CL and Levine MA: Low

bone mineral density is a common finding in patients with

homocystinuria. Mol Genet Metab. 117:351–354. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cordaro M, Siracusa R, Fusco R, Cuzzocrea

S, Di Paola R and Impellizzeri DJM: Involvements of

hyperhomocysteinemia in neurological disorders. Metabolites.

11:372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yap S and Naughten E: Homocystinuria due

to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency in Ireland: 25 years'

experience of a newborn screened and treated population with

reference to clinical outcome and biochemical control. J Inherit

Metab Dis. 21:738–747. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gerrard A and Dawson C: Homocystinuria

diagnosis, management: It is not all classical. J Clin Pathol.

75:744–750. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kožich V, Ditrói T, Sokolová J, Křížková

M, Krijt J, Ješina P and Nagy P: Metabolism of sulfur compounds in

homocystinurias. Br J Pharmacol. 176:594–606. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Horowitz JH, Rypins EB, Henderson JM,

Heymsfield SB, Moffitt SD, Bain RP, Chawla RK, Bleier JC and Rudman

D: Evidence for impairment of transsulfuration pathway in

cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 81:668–675. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sacharow SJ, Picker JD and Levy HL:

Homocystinuria caused by cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency.

2017.

|

|

21

|

Richard E, Desviat LR, Ugarte M and Pérez

B: Oxidative stress and apoptosis in homocystinuria patients with

genetic remethylation defects. J Cell Biochem. 114:183–191. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Obeid R: The metabolic burden of methyl

donor deficiency with focus on the betaine homocysteine

methyltransferase pathway. Nutrients. 5:3481–3495. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Münke M, Kraus JP, Ohura T and Francke U:

The gene for cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) maps to the

subtelomeric region on human chromosome 21q and to proximal mouse

chromosome 17. Am J Hum Genet. 42:5501988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu X, Liu X, Liu J, Guo J, Nie D and Wang

J: Identification and functional analysis of cystathionine

beta-synthase gene mutations in chinese families with classical

homocystinuria. Biomedicines. 13:9192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Poloni S, Sperb-Ludwig F, Borsatto T, Hoss

GW, Doriqui MJR, Embiruçu EK, Boa-Sorte N, Marques C, Kim CA, de

Souza CFM, et al: CBS mutations are good predictors for

B6-responsiveness: A study based on the analysis of 35 Brazilian

Classical Homocystinuria patients. Mol Genet Genomic Med.

6:160–170. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li DX, Li XY, Dong H, Liu YP, Ding Y, Song

JQ, Jin Y, Zhang Y, Wang Q and Yang YL: Eight novel mutations of

CBS gene in nine Chinese patients with classical homocystinuria.

World J Pediatr. 14:197–203. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sibani S, Christensen B, O'Ferrall E,

Saadi I, Hiou-Tim F, Rosenblatt DS and Rozen R: Characterization of

six novel mutations in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

(MTHFR) gene in patients with homocystinuria. Hum Mutat.

15:280–287. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li WX, Dai SX, Zheng JJ, Liu JQ and Huang

JFJN: Homocysteine metabolism gene polymorphisms (MTHFR C677T,

MTHFR A1298C, MTR A2756G and MTRR A66G) jointly elevate the risk of

folate deficiency. Nutrients. 7:6670–6687. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li WX, Cheng F, Zhang AJ, Dai SX, Li GH,

Lv WW, Zhou T, Zhang Q, Zhang H, Zhang T, et al: Folate deficiency

and gene polymorphisms of MTHFR, MTR and MTRR elevate the

hyperhomocysteinemia risk. Clin Lab. 63:523–533. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zaric BL, Obradovic M, Bajic V, Haidara

MA, Jovanovic M and Isenovic ER: Homocysteine and

hyperhomocysteinaemia. Curr Med Chem. 26:2948–2961. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sellos-Moura M, Glavin F, Lapidus D, Evans

KA, Palmer L and Irwin DE: Estimated prevalence of moderate to

severely elevated total homocysteine levels in the United States: A

missed opportunity for diagnosis of homocystinuria? Mol Genet

Metab. 130:36–40. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Levy HL, Mudd SH, Schulman JD, Dreyfus PM

and Abeles RH: A derangement in B12 metabolism associated with

homocystinemia, cystathioninemia, hypomethioninemia and

methylmalonic aciduria. Am J Med. 48:390–397. 1970. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Carey MC, Fennelly JJ and FitzGerald O:

Homocystinuria: II. Subnormal serum folate levels, increased folate

clearance and effects of folic acid therapy. Am J Med. 45:26–31.

1968. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bartholomew DW, Batshaw ML, Allen RH, Roe

CR, Rosenblatt D, Valle DL and Francomano CA: Therapeutic

approaches to cobalamin-C methylmalonic acidemia and

homocystinuria. J Pediatr. 112:32–39. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kraus JP: Molecular basis of phenotype

expression in homocystinuria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 17:383–390.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tsai MY, Garg U, Key NS, Hanson NQ, Suh A

and Schwichtenberg K: Molecular and biochemical approaches in the

identification of heterozygotes for homocystinuria.

Atherosclerosis. 122:69–77. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mohamed AS, AlAnzi T, Alhashem A, Alrukban

H, Al Harbi F and Mohamed S: Clinicalbiochemical molecular

characteristics of classic homocystinuria in Saudi Arabia, the

impact of newborn screening on prevention of the complications: A

tertiary center experience. JIMD Rep. 66:e124542025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Alcaide P, Krijt J, Ruiz-Sala P, Ješina P,

Ugarte M, Kožich V and Merinero B: Enzymatic diagnosis of

homocystinuria by determination of cystathionine-ß-synthase

activity in plasma using LC-MS/MS. Clin Chim Acta. 438:261–265.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Vyletal P, Sokolová J, Cooper DN, Kraus

JP, Krawczak M, Pepe G, Rickards O, Koch HG, Linnebank M,

Kluijtmans LA, et al: Diversity of cystathionine β-synthase

haplotypes bearing the most common homocystinuria mutation c.

833T> C: A possible role for gene conversion. Hum Mutat.

28:255–264. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kruger WD, Wang L, Jhee KH, Singh RH and

Elsas II LJ: Cystathionine β-synthase deficiency in Georgia (USA):

Correlation of clinical and biochemical phenotype with genotype.

Hum Mutat. 22:434–441. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Linnebank M, Janosik M, Kozich V, Pronicka

E, Kubalska J, Sokolova J, Linnebank A, Schmidt E, Leyendecker C,

Klockgether T, et al: The cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) mutation

c.1224-2A>C in Central Europe: Vitamin B6 nonresponsiveness and

a common ancestral haplotype. Hum Mutat. 24:352–353. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Al-Sadeq DW, Thanassoulas A, Islam Z,

Kolatkar P, Al-Dewik N, Safieh-Garabedian B, Nasrallah GK and

Nomikos M: Pyridoxine non-responsive p. R336C mutation alters the

molecular properties of cystathionine beta-synthase leading to

severe homocystinuria phenotype. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj.

1866:1301482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gdynia N, Gratzer A and Gdynia HJ:

Polyneuropathy due to vitamin B6 hypervitaminosis: A case series

and call for more education. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 16:99–103.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Liu Y, Guo J, Cheng H, Wang J, Tan Y,

Zhang J, Tao H, Liu H, Xiao J, Qu D, et al: Methionine restriction

diets: Unravelling biological mechanisms and enhancing brain

health. Trends Food Sci Technol. 149:1045322024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Pokrzywinski R, Bartke D, Clucas C,

Machuzak K and Pinto L: ‘My dream is to not have to be on a diet’:

A qualitative study on burdens of classical homocystinuria (HCU)

from the patient perspective. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 20:1–11. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Skvorak K, Mitchell V, Teadt L, Franklin

KA, Lee HO, Kruse N, Huitt-Roehl C, Hang J, Du F, Galanie S, et al:

An orally administered enzyme therapeutic for homocystinuria that

suppresses homocysteine by metabolizing methionine in the

gastrointestinal tract. Mol Genet Metab. 139:1076532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Perreault M, Means J, Gerson E, James M,

Cotton S, Bergeron CG, Simon M, Carlin DA, Schmidt N, Moore TC, et

al: The live biotherapeutic SYNB1353 decreases plasma methionine

via directed degradation in animal models and healthy volunteers.

Cell Host Microbe. 32:382–395. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Truitt C, Hoff WD and Deole R: Health

functionalities of betaine in patients with homocystinuria. Front

Nutr. 8:6903592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Singh RH, Kruger WD, Wang L, Pasquali M

and Elsas LJ II: Cystathionine β-synthase deficiency: Effects of

betaine supplementation after methionine restriction in

B6-nonresponsive homocystinuria. Genet Med. 6:90–95. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Schwab U, Törrönen A, Toppinen L, Alfthan

G, Saarinen M, Aro A and Uusitupa M: Betaine supplementation

decreases plasma homocysteine concentrations but does not affect

body weight, body composition, or resting energy expenditure in

human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 76:961–967. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lu XT, Wang YN, Mo QW, Huang BX, Wang YF,

Huang ZH, Luo Y, Maierhaba W, He TT, Li SY, et al: Effects of

low-dose B vitamins plus betaine supplementation on lowering

homocysteine concentrations among Chinese adults with

hyperhomocysteinemia: A randomized, double-blind, controlled

preliminary clinical trial. Eur J Nutr. 62:1599–1610. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Imbard A, Toumazi A, Magréault S,

Garcia-Segarra N, Schlemmer D, Kaguelidou F, Perronneau I, Haignere

J, de Baulny HO, Kuster A, et al: Efficacy pharmacokinetics of

betaine in CBS, cblC deficiencies: A cross-over randomized

controlled trial. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 17:4172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zawieja EE, Bogna Z and Chmurzynska A:

Betaine supplementation moderately increases total cholesterol

levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diet Suppl.

18:105–117. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Marroncini G, Martinelli S, Menchetti S,

Bombardiere F and Martelli FS: Hyperhomocysteinemia and disease-is

10 µmol/l a suitable new threshold limit? Int J Mol Sci.

25:122952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

McCaddon A and Miller JW: Homocysteine-a

retrospective and prospective appraisal. Front Nutr.

10:11798072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kok DEG, Dhonukshe-Rutten RAM, Lute C,

Heil SG, Uitterlinden AG, van der Velde N, van Meurs JB, van Schoor

NM, Hooiveld GJ, de Groot LC, et al: The effects of long-term daily

folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation on genome-wide DNA

methylation in elderly subjects. Clin Epigenetics. 7:1212015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Meier M, Janosik M, Kery V, Kraus JP and

Burkhard P: Structure of human cystathionine beta-synthase: A

unique pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent heme protein. EMBO J.

20:3910–3916. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Bublil EM and Majtan T: Classical

homocystinuria: From cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency to

novel enzyme therapies. Biochimie. 173:48–56. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Bublil EM, Majtan T, Park I, Carrillo RS,

Hůlková H, Krijt J, Kožich V and Kraus JP: Enzyme replacement with

PEGylated cystathionine β-synthase ameliorates homocystinuria in

murine model. J Clin Invest. 126:2372–2384. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ficicioglu C, Ganesh J, Smith W, Lah M,

Kudrow D, Güner J, McDermott S, Vaidya S, Wilkening L, Thomas J and

Levy H: P012: Pegtibatinase, an investigational enzyme replacement

therapy for the treatment of classical homocystinuria: Latest

findings from the COMPOSE phase 1/2 trial. Genetics in Medicine

Open. 2:1008892024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Majtan T, Jones W Jr, Krijt J, Park I,

Kruger WD, Kožich V, Bassnett S, Bublil EM and Kraus JP: Enzyme

replacement therapy ameliorates multiple symptoms of murine

homocystinuria. Mol Ther. 26:834–844. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Cramer SL, Saha A, Liu J, Tadi S, Tiziani

S, Yan W, Triplett K, Lamb C, Alters SE, Rowlinson S, et al:

Systemic depletion of L-cyst (e) ine with cyst (e) inase increases

reactive oxygen species and suppresses tumor growth. Nat Med.

23:120–127. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Majtan T, Kožich V and Kruger WD: Recent

therapeutic approaches to cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient

homocystinuria. Br J Pharmacol. 180:264–278. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

A Phase 1/2 Multiple Ascending-Dose Study

in Subjects With Homocystinuria Due to Cystathionine β-Synthase

(CBS) Deficiency to Investigate the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and

Pharmacodynamics of ACN00177. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05154890August

11–2025

|

|

65

|

Aeglea BioTherapeutics: Aeglea

BioTherapeutics Announces Interim Results from Ongoing Phase 1/2

Clinical Trial of Pegtarviliase for the Treatment of Classical

Homocystinuria and Begins Process to Explore Strategic

Alternatives. https://ir.aeglea.com/press-releases/news-details/2023/Aeglea-BioTherapeutics-Announces-Interim-Results-from-Ongoing-Phase-12-Clinical-Trial-of-Pegtarviliase-for-the-Treatment-of-Classical-Homocystinuria-and-Begins-Process-to-Explore-Strategic-Alternatives/default.aspxAugust

11–2025

|

|

66

|

Wang L, Chen X, Tang B, Hua X,

Klein-Szanto A and Kruger WD: Expression of mutant human

cystathionine β-synthase rescues neonatal lethality but not

homocystinuria in a mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 14:2201–2208. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Syntis Bio, . Syntis Bio Launches to

Revolutionize Oral Therapy for Obesity, Diabetes and Rare Diseases

by Unlocking the Full Therapeutic Potential of the Small Intestine.

https://syntis.bio/syntis-bio-launches-to-revolutionize-oral-therapy-for-obesity-diabetes-and-rare-diseases-by-unlocking-the-full-therapeutic-potential-of-the-small-intestine/August

11–2025

|

|

68

|

Lee HO, Salami CO, Sondhi D, Kaminsky SM,

Crystal RG and Kruger WD: Long-term functional correction of

cystathionine β-synthase deficiency in mice by adeno-associated

viral gene therapy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 44:1382–1392. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Gao G, Lin J

and Wilson JM: Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to

adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis. 199:381–390. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

George LA, Sullivan SK, Giermasz A, Rasko

JEJ, Samelson-Jones BJ, Ducore J, Cuker A, Sullivan LM, Majumdar S,

Teitel J, et al: Hemophilia B gene therapy with a

high-specific-activity factor IX variant. N Engl J Med.

377:2215–2227. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chandler RJ, LaFave MC, Varshney GK,

Trivedi NS, Carrillo-Carrasco N, Senac JS, Wu W, Hoffmann V,

Elkahloun AG, Burgess SM and Venditti CP: Vector design influences

hepatic genotoxicity after adeno-associated virus gene therapy. J

Clin Invest. 125:870–880. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Lee HO, Gallego-Villar L, Grisch-Chan HM,

Häberle J, Thöny B and Kruger WD: Treatment of cystathionine

β-synthase deficiency in mice using a minicircle-based naked DNA

vector. Hum Gene Ther. 30:1093–1100. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Collard R and Majtan T: Genetic and

pharmacological modulation of cellular proteostasis leads to

partial functional rescue of homocystinuria-causing

cystathionine-beta synthase variants. Mol Cell Biol. 43:664–674.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Majtan T, Pey AL, Gimenez-Mascarell P,

Martínez-Cruz LA, Szabo C, Kožich V and Kraus JP: Potential

pharmacological chaperones for cystathionine

beta-synthase-deficient homocystinuria. Handb Exp Pharmacol.

245:345–383. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Kopecká J, Krijt J, Raková K and Kožich V:

Restoring assembly and activity of cystathionine β-synthase mutants

by ligands and chemical chaperones. J Inherit Metab Dis. 34:39–48.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kluijtmans LA, Boers GH, Stevens EM,

Renier WO, Kraus JP, Trijbels FJ, van den Heuvel LP and Blom HJ:

Defective cystathionine beta-synthase regulation by

S-adenosylmethionine in a partially pyridoxine responsive

homocystinuria patient. J Clin Invest. 98:285–289. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Mendes MI, Colaço HG, Smith DE, Ramos RJ,

Pop A, van Dooren SJ, de Almeida IT, Kluijtmans LA, Janssen MC,

Rivera I, et al: Reduced response of Cystathionine Beta-Synthase

(CBS) to S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM): Identification and functional

analysis of CBS gene mutations in Homocystinuria patients. J

Inherit Metab Dis. 37:245–254. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Melenovská P, Kopecká J, Krijt J, Hnízda

A, Raková K, Janošík M, Wilcken B and Kožich V: Chaperone therapy

for homocystinuria: The rescue of CBS mutations by heme arginate. J

Inherit Metab Dis. 38:287–294. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Kim D and Li GC: Proteasome inhibitors

lactacystin and MG132 inhibit the dephosphorylation of HSF1 after

heat shock and suppress thermal induction of heat shock gene

expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 264:352–358. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Gupta S, Wang L, Anderl J, Slifker MJ,

Kirk C and Kruger WD: Correction of cystathionine β-synthase

deficiency in mice by treatment with proteasome inhibitors. Hum

Mutat. 34:1085–1093. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Gupta S, Wang L and Kruger WD: The c.797

G>A (p.R266K) cystathionine β-synthase mutation causes

homocystinuria by affecting protein stability. Hum Mutat.

38:863–869. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Gupta S, Lee HO, Wang L and Kruger WD:

Examination of two different proteasome inhibitors in reactivating

mutant human cystathionine β-synthase in mice. PLoS One.

18:e02865502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Isabella VM, Ha BN, Castillo MJ, Lubkowicz

DJ, Rowe SE, Millet YA, Anderson CL, Li N, Fisher AB, West KA, et

al: Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the

human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat Biotechnol.

36:857–864. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Puurunen MK, Vockley J, Searle SL,

Sacharow SJ, Phillips JA III, Denney WS, Goodlett BD, Wagner DA,

Blankstein L, Castillo MJ, et al: Safety pharmacodynamics of an

engineered E. coli Nissle for the treatment of phenylketonuria: A

first-in-human phase 1/2a study. Nat Metab. 3:1125–1132. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lin NC, Niu DM, Loong CC, Hsia CY, Tsai

HL, Yeh YC, Tsou MY and Liu CS: Liver transplantation for a patient

with homocystinuria. Pediatr Transplant. 16:E311–E314. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Kerkvliet SP, Rheault MN and Berry SA:

Liver transplant as a curative treatment in a pediatric patient

with classic homocystinuria: A case report. Am J Med Genet A.

185:1247–1250. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Li DX, Chen ZH, Jin Y, Song JQ, Li MQ, Liu

YP, Li XY, Chen YX, Zhang YN, Lyu GY, et al: Clinical