Introduction

Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury

represents a life-threatening condition precipitated by a transient

interruption of blood flow to the intestines, followed by the

abrupt restoration of circulation (1). This sequence of events triggers a

cascade of detrimental effects, including oxidative stress,

inflammation and apoptosis, all of which culminate in substantial

tissue damage due to the sudden influx of oxygenated blood

(2). I/R injury is frequently

encountered in clinical scenarios such as organ transplantation or

intestinal obstruction, where the restoration of blood supply,

while intended to rescue tissue viability, often exacerbates

cellular injury (3). Extensive

investigations into the molecular mechanisms underlying I/R injury

have revealed the involvement of multiple genes and signaling

pathways in these pathological processes. Specifically,

ferroptosis-induced intestinal tissue damage during I/R can be

mitigated by inhibiting acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family

member 4 before reperfusion, highlighting the therapeutic potential

of targeting ferroptosis-related genes (4). Additionally, it has been demonstrated

that the activation of JUN and FOS transcription

factors during I/R injury orchestrates a dual role, promoting both

apoptosis and compensatory cell proliferation, thereby underscoring

the complexity of cellular responses to I/R stress (5). Furthermore, heme oxygenase-1 has

emerged as a critical regulator of the oxidative stress response

during I/R injury, with its induction serving as a protective

mechanism against oxidative damage (6). Despite these advances, the complex

interplay between signaling pathways implicated in I/R injury

remains incompletely understood. Oxidative stress, a cornerstone of

I/R-induced tissue damage, is orchestrated by a multitude of

molecular factors, the interactions and cross-talk of which dictate

the extent of cellular injury and recovery (7). Thus, further research is required to

determine the complex regulatory networks governing I/R injury,

with the aim of identifying novel therapeutic targets to mitigate

tissue damage and improve clinical outcomes.

The lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin B

(CTSB) serves a role in various digestive system disorders.

Studies have demonstrated that CTSB deficiency effectively

mitigates symptoms linked to hypoxia-ischemia, inflammation and

pain (8,9). For example, Xihuang pills have been

shown to alleviate colitis by modulating CTSB levels, which

in turn improve mucosal barrier integrity and suppress inflammation

(10). Furthermore, Dong et

al (11) revealed that

administering mannose to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

supports lysosomal stability and curtails CTSB release,

thereby safeguarding against mitochondrial dysfunction during

intestinal epithelial injury. Notably, CTSB serves as a

mediator in the activation of NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3

(NLRP3) inflammasomes; it binds to NLRP3, thereby amplifying the

activity of the NLRP3/caspase-1 inflammasome pathway (12). Research has indicated that colon

inflammation induced by deoxycholic acid can be substantially

diminished by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome through the use of

S1PR2 inhibitors and CTSB antagonists (13). Despite the progress made in

understanding the involvement of CTSB in intestinal

diseases, research regarding its function and underlying mechanisms

in I/R-induced intestinal damage remains relatively limited. Th

present study aimed to address this knowledge gap by exploring the

role of CTSB in oxidative stress and disruption of the

intestinal barrier during I/R injury.

In the setting of I/R injury, an overabundance of

oxidative stress and inflammation represents a driving force behind

epithelial barrier dysfunction, thereby intensifying cellular

damage (14). Prior research has

identified the pivotal role of CTSB in fostering

inflammation and cell death in pathological states (15). Nevertheless, its precise

contribution to I/R-triggered intestinal injury has been relatively

under-investigated. The present study aimed to assess the effects

of CTSB knockdown on alleviating oxidative stress,

mitigating intestinal barrier impairment and curbing NLRP3

inflammasome activation in Caco-2 cells subjected to oxygen-glucose

deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R). The results of this

investigation may provide novel insights into the therapeutic

promise of targeting CTSB for the management of I/R

injury.

Materials and methods

Screening of datasets and

identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

For in-depth analysis, the GSE37013 dataset was

accessed from the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) repository,

originally reported by Kip et al (16). This dataset comprises 28 samples,

including seven non-ischemic surgical control jejunal samples

collected intraoperatively and 21 I/R case samples. Differential

expression analysis on the GSE37013 dataset was conducted using the

limma package (version 3.48.3; http://bioconductor.org/packages/limma) implemented in

R (version 4.1.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing;

http://www.r-project.org/). Genes

exhibiting a fold change (FC) of >1.3 were categorized as

upregulated, whereas those with an FC of <0.77 were deemed

downregulated; P<0.05 was employed to denote a statistically

significant difference. To visualize the DEGs, the ggplot2 package

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot2) was

utilized in R.

Expression validation of overlapping

genes in protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks

To elucidate the interactions among DEGs, a PPI

network analysis was conducted using the Search Tool for the

Retrieval of Interacting Genes (https://string-db.org/). The top 15 genes were

identified using the Cytohubba plugin within Cytoscape (version

3.9.1; http://cytoscape.org), employing

algorithms such as the maximum neighborhood component (MNC),

maximal clique centrality (MCC) and degree. Subsequently, an

intersection analysis was performed on the top 15 genes derived

from these three network modules using the Bioinformatics and

Evolutionary Genomics online tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

The gene expression levels of the intersection genes in both the

control and case groups of the GSE37013 dataset were then analyzed

using the SangerBox platform (http://sangerbox.com/). P<0.05 was deemed

statistically significant for the scores obtained in this

analysis.

Cell culture

Caco-2 cells, from a human colorectal

adenocarcinoma, were sourced from National Collection of

Authenticated Cell Cultures. These cells were cultured in DMEM

(Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (Procell Life Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Cell culture was performed at

37°C within a humidified incubator maintained at 5%

CO2.

I/R and inflammation models

An OGD/R model was established to simulate I/R

injury. The cells were subjected to OGD/R by being incubated in

glucose-free DMEM at 37°C within a microaerobic environment

(comprising 1% O2, 94% N2, 5% CO2)

for varying durations of 0, 2, 4 and 6 h. Subsequently, the cells

underwent reoxygenation in complete DMEM under normoxia at 37°C

(21% O2, 5% CO2, 74% N2) for 24 h.

Control cells were maintained in complete DMEM (with glucose and

10% FBS) at 37°C under normoxia (21% O2, 5%

CO2, balance N2) and underwent the same

medium-change schedule as the OGD/R groups. Additionally, to induce

inflammation, Caco-2 cells (which had been treated with OGD for 4 h

followed by reoxygenation for 24 h) were exposed to 1 µg/ml

lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 6 h at 37°C. Finally, adenosine triphosphate (ATP;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was introduced at a

concentration of 5 mM and the cells were incubated for 30 min at

37°C.

Cell transfection

Transfection was performed after OGD/R. After

seeding at a density of 2×105 cells/well in 6-well

plates, Caco-2 cells were cultured until they reached 60–70%

confluence. To achieve knockdown of CTSB, the cells were

transfected with specific small interfering RNA (siRNA; final

concentration, 50 nM) designed to target CTSB, adhering

strictly to the manufacturer's protocol. The transfection was

carried out using 10 µl Lipofectamine™ 2000 reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 6 h. As a negative

control (NC), a non-targeting siRNA was employed. Following

transfection, the cells were incubated for an additional 48 h

before being harvested for use in further experiments. The siRNA

sequences utilized for transfection were as follows:

si-CTSB, sense 5′-CCUGUCGGAUGAGCUGGUCAACU-3′, antisense

5′-AUAGUUGACCAGCUCAUCGACAG-3′; si-NC, sense

5′-CCUAGCGAGUGGUCAACUGUAU-3′, antisense

5′-AUACAGAGUUGACCACUCGCCUAG-3′.

Assessment of Caco-2 cell

viability

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was utilized to evaluate cell

viability, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Initially,

96-well plates were seeded with 5×103 Caco-2 cells/well

in 100 µl complete growth medium. The plates were then incubated

overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator maintained at 5%

CO2, allowing the cells to adhere and achieve a stable

growth state. Following this incubation period, each well was

supplemented with 10 µl CCK-8 solution, and the plates were further

incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, cell viability was

assessed by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate

reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). To ensure the robustness and

reliability of the findings, data from a minimum of three

independent experiments were subjected to statistical analysis.

Detection of lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH) levels

Caco-2 cells were exposed to OGD for 2, 4 and 6 h,

followed by 24 h of reoxygenation to evaluate the resultant impact

on LDH levels. According to the manufacturer's guidelines, culture

supernatants were carefully collected, and LDH levels were measured

using an LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). To ensure the reliability of the data, the assay

was conducted in triplicate for each time point. LDH activity was

quantified by recording the absorbance at 490 nm using a microplate

reader. Data obtained from a minimum of three independent

experiments were subjected to rigorous statistical analysis to

discern the significance of the differences in LDH levels across

the various OGD/R treatment durations.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from Caco-2 cells using

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's detailed instructions, after

the aforementioned OGD/R and/or LPS/ATP treatments. Subsequently, 1

µg isolated total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA utilizing

the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Biotechnology, Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed on a

Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.), employing the SYBR Green kit (Takara Biotechnology, Ltd.).

The expression levels of the target genes, as well as the internal

control GAPDH, were quantified using gene-specific primers

(Table I). The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles

at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec; a melt-curve analysis was

then performed from 65–95°C with 0.5°C increments. The relative

expression of each candidate gene was determined using the

2−ΔΔCq method (17). To

ensure the robustness of the findings, data from a minimum of three

independent experiments were subjected to statistical analysis.

| Table I.Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Target | Sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| CTSB | F:

GTACACCTGCGAGTGTTCCA |

|

| R:

CAAGTGCACGCTCTGGTAGA |

| ZO-1 | F:

CTCAAGAGGAAGCTGTGGGT |

|

| R:

CCATTGCTGTGCTAGTGAGC |

| CLDN1 | F:

ATGACCCCAGTCAATGCCAG |

|

| R:

GCTGGAAGGTGCAGGTTTTG |

| TNF-α | F:

CACAGTGAAGTGCTGGCAAC |

|

| R:

AGGAAGGCCTAAGGTCCACT |

| IL-6 | F:

TTCGGTCCAGTTGCCTTCTC |

|

| R:

CTGAGATGCCGTCGAGGATG |

| IL-1β | F:

AGCCATGGCAGAAGTACCTG |

|

| R:

GAAGCCCTTGCTGTAGTGGT |

| GAPDH | F:

CATGTTGCAACCGGGAAGGA |

|

| R:

ATCACCCGGAGGAGAAATCG |

Western blot (WB) analysis

To lyse Caco-2 cells, RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was prepared with the addition of

protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The total protein content in

the lysates was then quantified using a BCA protein assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equal amounts of protein (20

µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and were

subsequently transferred onto PVDF membranes (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). To prevent non-specific binding, the membranes were

blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% skim milk dissolved in

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST). To detect the

target proteins, the antibodies for each target protein and the

internal control GAPDH antibody were mixed separately, and the PVDF

membranes were incubated with the primary antibody solutions at 4°C

overnight. The following primary antibodies were used: CTSB (cat.

no. 12216-1-AP; 1:1,000; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), active CTSB

(cat. no. 12216-1-AP; 1:1,000; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), ZO-1

(cat. no. ab276131; 1:1,000; Abcam), claudin-1 (cat. no. ab211737;

1:2,000; Abcam), NLRP3 (cat. no. 30109-1-AP; 1:2,000; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology), gasdermin D (GSDMD; cat. no. ab210070; 1:1,000;

Abcam), cleaved N-terminal GSDMD (GSDMD-N; cat. no. ab215203;

1:2,000; Abcam), ASC (cat. no. 10500-1-AP; 1:5,000; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology), cleaved caspase-1 (p20; cat no. AF4005; 1:2,000;

Affinity Biosciences), caspase-1 (cat. no. ab207802; 1:1,000;

Abcam), IL-1β (cat. no. ab283818; 1:1,000; Abcam), IL-18 (cat. no.

82696-15-RR; 1:2,000; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology) and GAPDH (cat.

no. 80570-1-RR; 1:2,500; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology). After

washing the membranes three times with TBST, they were incubated

for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

IgG (cat. no. A0208; 1:1,000; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Protein bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence

detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Band intensities

were semi-quantified using ImageJ software (version 2.0.0; National

Institutes of Health). To ensure accurate normalization, the bands

of both the proteins of interest and GAPDH were developed from the

same membrane, subjected to the same blocking, incubation and

washing steps, and visualized under identical conditions.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

To investigate the interaction between CTSB and

NLRP3, co-IP was employed. Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA

buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with a

protease-inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were clarified at 12,000 × g

for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentrations were determined by

BCA assay. The resulting cell lysates were then mixed with 30 µl

protein A/G agarose bead slurry (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.)

per 1 mg total protein for 1 h at 4°C on a rotator to remove

non-specific binding. Following centrifugation (2,500 × g, 3 min,

4°C), the agarose beads were discarded, and the supernatant,

containing the pre-cleared lysates, was collected. Primary

antibodies specific for either CTSB (cat. no. ab30443; Abcam) or

NLRP3 (cat. no. 30109-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), or an

equal amount of species-matched normal IgG (negative control), were

added at 2 µg per IP and mixtures were incubated for 6 h at 4°C on

a rotator to allow antigen-antibody binding. Subsequently, an

additional 30 µl protein A/G agarose beads was added, and the

suspensions were rotated overnight at 4°C to capture the

antigen-antibody complexes. Beads were collected by centrifugation

(2,500 × g, 3 min, 4°C) and washed four times with ice-cold RIPA

lysis buffer (1 ml/wash) to remove any unbound proteins. The

antigen-antibody complexes were eluted from the beads using 2X

Laemmli SDS sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min. The eluate was boiled

and denatured to prepare it for subsequent WB analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

ELISA was carried out to quantify CTSB, TNF-α, IL-6

and IL-1β using the following commercially available kits: Human

CTSB ELISA Kit (cat. no. ab119584; Abcam), Human TNF-αELISA Kit

(cat. no. BMS2034; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

Human IL-6 ELISA Kit (cat. no. EH2IL6; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), and Human IL-1β Instant ELISA Kit (cat. no.

BMS224INST; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. For each assay, 100 µl Caco-2

cell culture supernatant/well was carefully transferred to

pre-coated 96-well plates, and the plates were incubated according

to the manufacturer's guidelines. The enzymatic reaction was

developed using the tetramethylbenzidine substrate, and the

absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Protein concentrations were calculated based on standard curves

generated with kit-supplied standards. To ensure the robustness and

reliability of the results, each experiment was replicated at least

three times. Data from these independent experiments were subjected

to statistical analysis to evaluate the significance of differences

in protein levels between experimental groups.

Immunofluorescence analysis

After OGD for 4 h followed by 24 h reoxygenation,

cells were fixed for 15 min at room temperature in 4%

paraformaldehyde solution. Subsequently, the cells were

permeabilized for 10 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 to facilitate

antibody penetration and then blocked for 1 h with 5% bovine serum

albumin (BSA; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) dissolved in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to mitigate non-specific binding.

Primary antibodies targeting ZO-1 (cat. no. ab276131; 1:500) and

claudin-1 (cat. no. ab211737; 1:1,000) (both from Abcam) were

diluted in 1% BSA and incubated with the cells overnight at 4°C to

allow for specific antigen-antibody interactions. The following

day, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor®

488-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (cat. no.

A-11008; 1:1,000; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1

h at room temperature in the dark to preserve the fluorescence

signal. The nuclei were counterstained DAPI (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 5 min at room temperature after washing with

PBS. Fluorescence microscopy images were captured using a

fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-U; Nikon Corporation). To

ensure the reproducibility and reliability of our findings, the

entire immunofluorescence staining protocol was replicated at least

three times, with three technical replicates per condition in each

experiment.

Oxidative stress markers assay

After 4 h of OGD followed by 24 h of reoxygenation,

cells were lysed on ice using the kit-supplied sample lysis buffer

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The lysates were

subsequently analyzed using commercially available detection kits

for reactive oxygen species (ROS; cat. no. S0033S), malondialdehyde

(MDA; cat. no. S0131S), superoxide dismutase (SOD; cat. no. S101S)

and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px; cat. no. S0059S) (all from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). These assays were conducted

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance values

were recorded using a microplate reader at the following specific

wavelengths: 488 nm (excitation) and 525 nm (emission) for ROS, 412

nm for GSH-Px, 450 nm for SOD and 532 nm for MDA. To ensure the

reliability and reproducibility of the data, each test was

performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. To determine statistical significance, one-way analysis

of variance was utilized, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for

multiple comparisons between groups. For pairwise comparisons

between two specific groups, a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test

was employed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. All statistical analyses were conducted

using the R programming language. Additionally, graphs were

generated exclusively for visualization purposes using GraphPad

Prism software (version 8.0; Dotmatics) to facilitate

interpretation of the results.

Results

Differential expression and PPI

network analysis to obtain key intersection genes

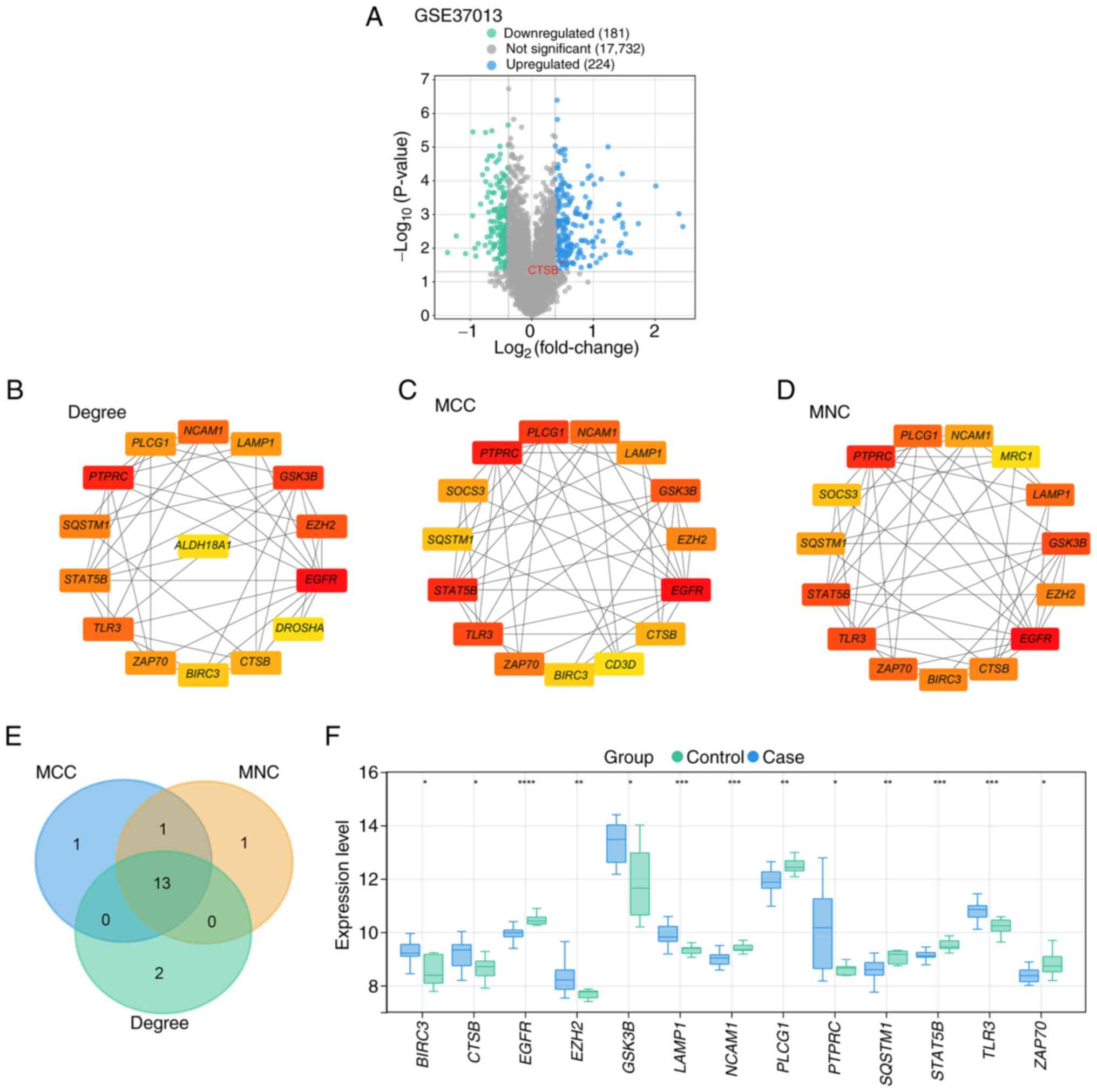

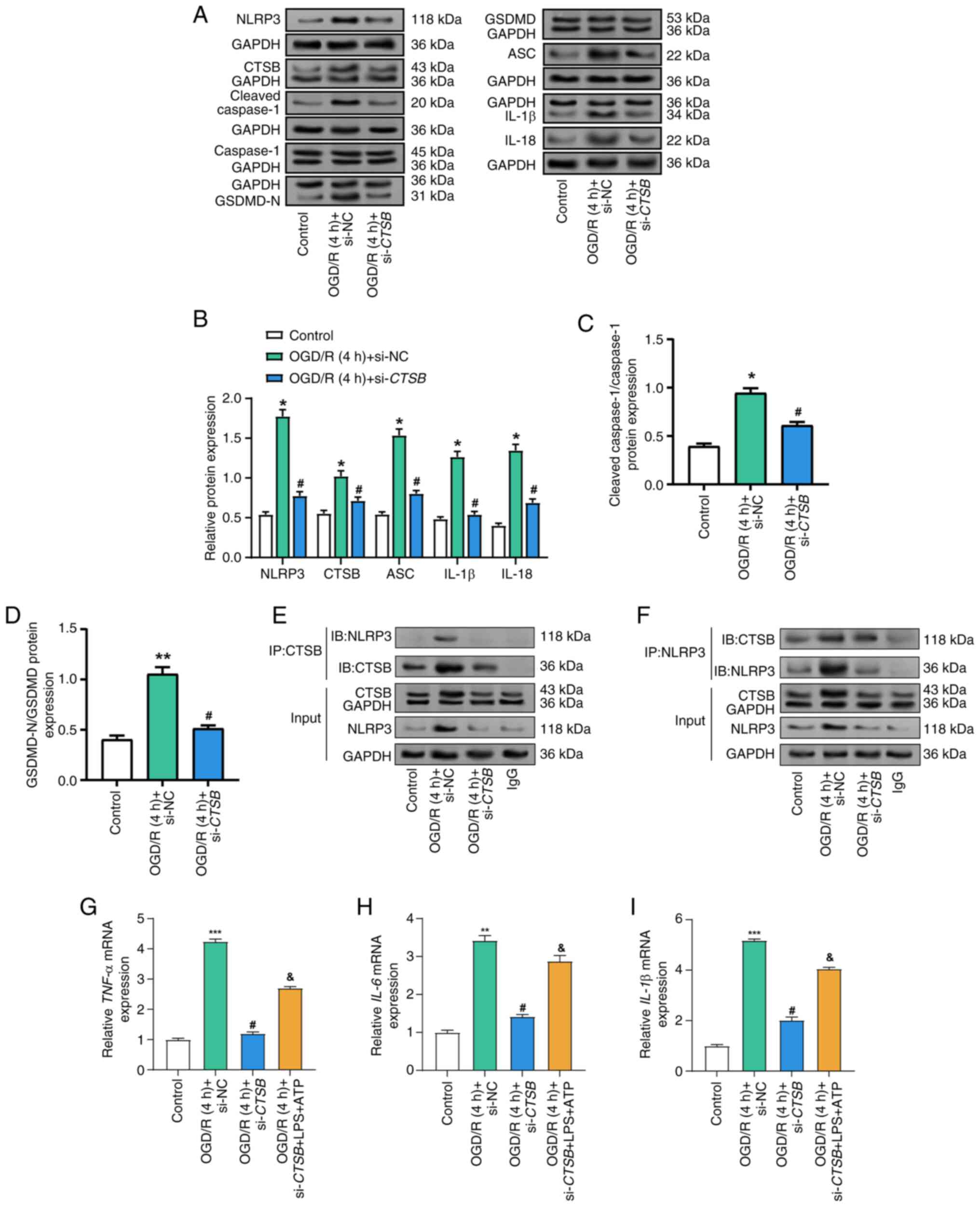

First, a differential expression analysis was

conducted using the GSE37013 dataset, comparing I/R jejunal samples

(n=21) with non-ischemic surgical controls (n=7), which yielded 181

downregulated and 224 upregulated DEGs (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, a PPI network

analysis was performed on the DEGs. This analysis revealed the top

15 genes as identified by three different algorithms: Degree (15

nodes and 44 edges; Fig. 1B), MCC

(15 nodes and 50 edges; Fig. 1C)

and MNC (15 nodes and 52 edges; Fig.

1D). Following this, a cross-analysis of the top 15 genes from

each of the three algorithms was conducted, resulting in the

identification of 13 key intersection genes (Fig. 1E). Expression analysis was then

performed to examine the expression levels of these genes in both

the control and case samples from the GSE37013 dataset (Fig. 1F). The results demonstrated that in

the case samples, BIRC3, CTSB, EZH2, GSK3B, LAMP1, PTPRC and

TLR3 were significantly upregulated, whereas EGFR, NCAM1,

PLCG1, SQSTM1, STAT5B and ZAP70 were significantly

downregulated.

| Figure 1.Screening of DEGs, PPI network

construction and intersection analysis based on the GSE37013

dataset to identify hub genes. (A) Volcano plot of DEGs in the

GSE37013 dataset. Green represents 181 downregulated DEGs and blue

represents 224 upregulated DEGs. PPI network analysis of

upregulated DEGs using (B) degree, (C) MCC and (D) MNC algorithms,

and visualization of the top 15 genes in each network. (E) Venn

diagram of the intersection analysis of the top 15 genes of the

degree, MCC and MNC algorithms, where the overlapping genes

represent the intersection genes. (F) Box plot of the expression

levels of 13 intersection genes in control and case samples from

the GSE37013 dataset. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. CTSB, cathepsin B; DEG, differentially

expressed gene; MCC, maximal clique centrality; MNC, maximum

neighborhood component; PPI, protein-protein interaction. |

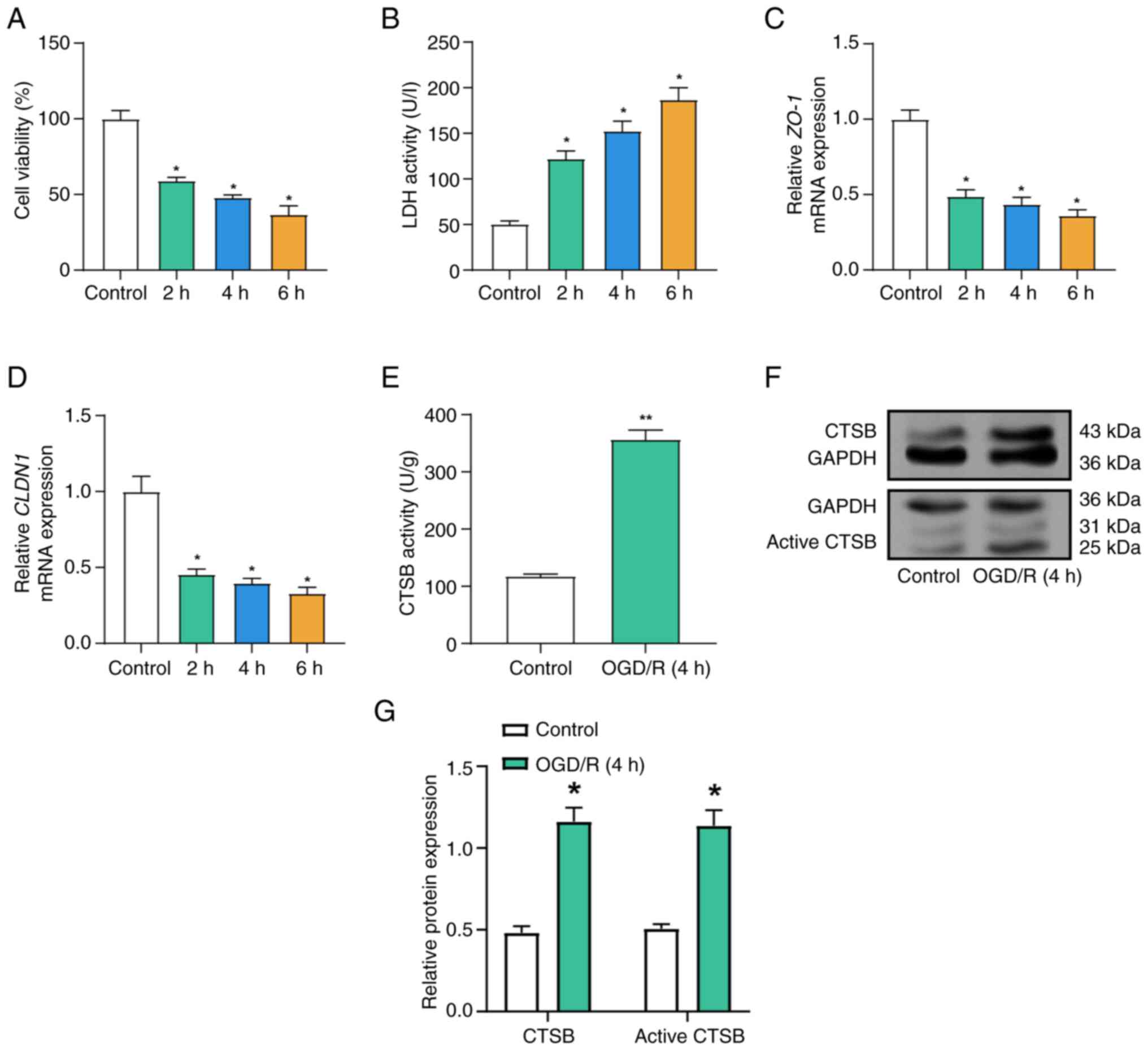

OGD/R decreases cell viability,

disrupts tight junction protein expression and increases CTSB

activity

The current study assessed the effects of OGD/R on

the expression of tight junction proteins and CTSB, LDH release and

cell survival in Caco-2 cells. Compared with in the control group,

as the duration of OGD/R treatment was extended, the results from

the CCK-8 assay revealed a progressive decline in cell viability

(Fig. 2A). Concurrently, a

significant increase in LDH levels was observed with prolonged

OGD/R exposure (Fig. 2B).

Furthermore, following OGD/R treatment, there was a gradual

decrease in the mRNA expression levels of ZO-1 and

CLDN1, with their levels declining progressively as the

duration of OGD/R exposure increased (Fig. 2C and D). Based on preliminary

experiments (Fig. 2A and B), which

demonstrated significant but sub-lethal injury at the 4-h OGD mark,

consistent with established in vitro I/R models (18), subsequent experiments used the same

4-h OGD treatment to further examine its effect on CTSB activity.

Subsequently, an ELISA was employed to examine CTSB activity in

Caco-2 cells. In the OGD/R model, CTSB activity was markedly

elevated compared with that in the control group (Fig. 2E). WB analysis further confirmed

that both total CTSB protein and active CTSB protein levels were

increased following OGD/R treatment (Fig. 2F and G).

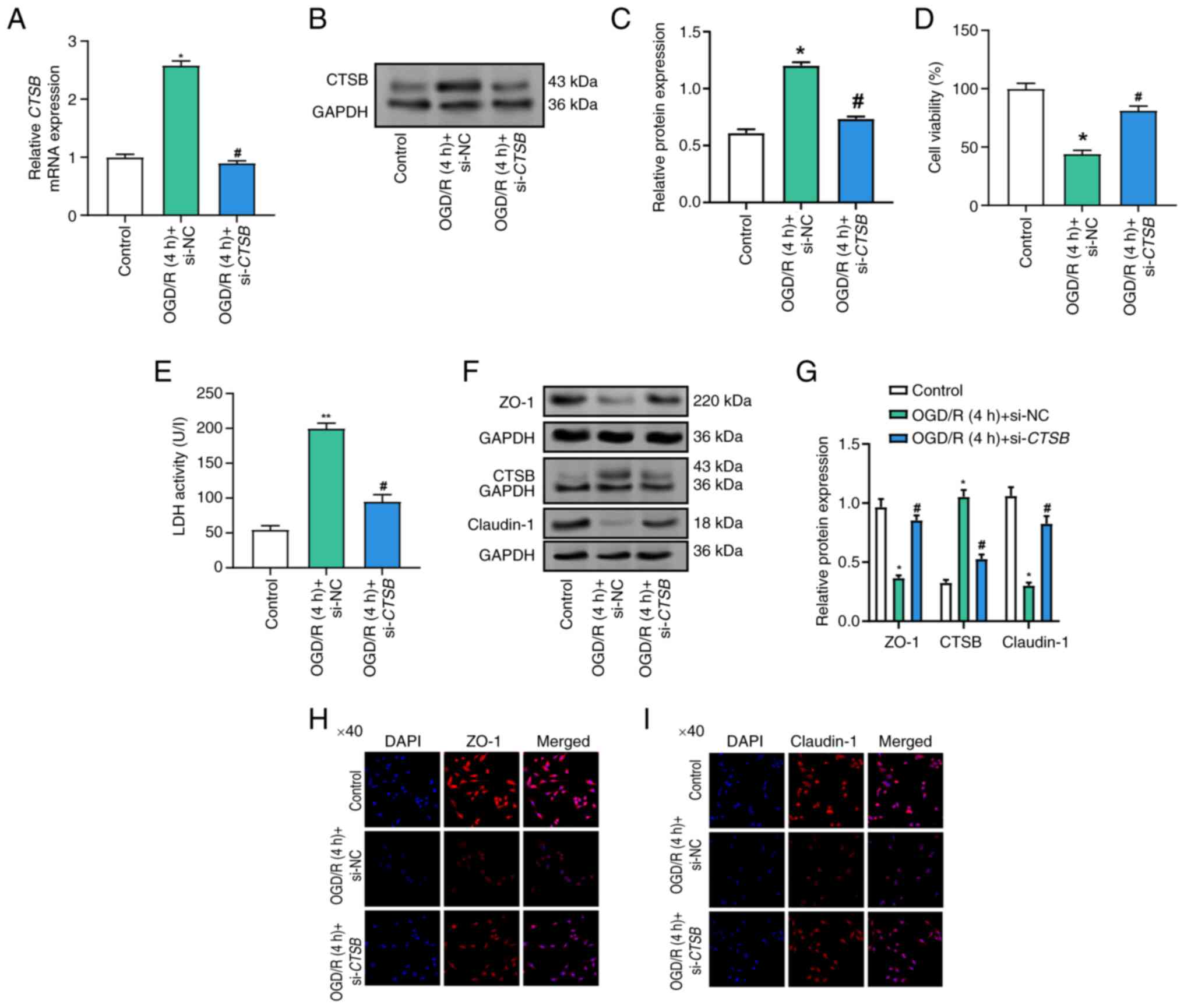

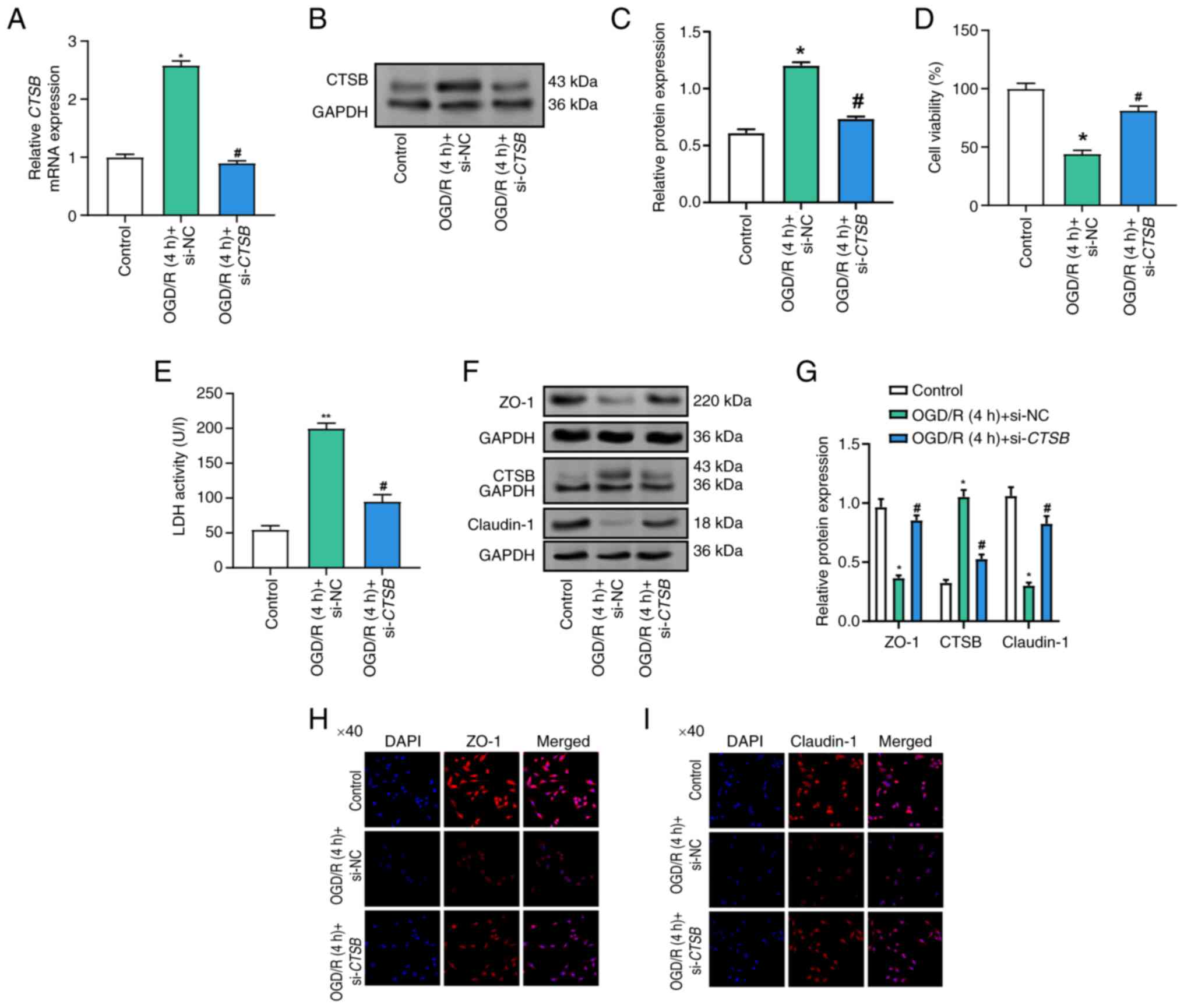

CTSB knockdown alleviates

OGD/R-induced Caco-2 cell injury

RT-qPCR and WB analysis confirmed the efficient

knockdown of CTSB, resulting in a significant reduction in

CTSB expression following transfection (Figs. S1 and 3A-C). To evaluate the impact of

CTSB knockdown on the viability of Caco-2 cells exposed to

OGD/R, the CCK-8 assay was employed. OGD/R resulted in a marked

reduction in cell viability compared with that in the control

group, whereas CTSB knockdown effectively reversed this

reduction, thereby preserving cell viability (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, LDH levels, which

serve as an indicator of cell damage, were markedly elevated in the

OGD/R-treated cells; however, CTSB knockdown notably reduced

LDH release, suggesting a decrease in cellular injury (Fig. 3E). WB analysis results further

revealed that the protein levels of ZO-1 and claudin-1, both of

which were reduced in the OGD/R model, were restored following

CTSB knockdown (Fig. 3F and

G). Immunofluorescence staining provided additional

confirmation, demonstrating the recovery of ZO-1 and claudin-1

expression after CTSB knockdown (Fig. 3H and I). Collectively, these

findings suggested that CTSB knockdown may mitigate

I/R-induced cellular injury and preserve epithelial barrier

integrity in Caco-2 cells.

| Figure 3.Effects of CTSB knockdown on

cell viability, LDH activity and tight junction protein expression

in OGD/R-treated Caco-2 cells. (A) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis of the relative expression

levels of CTSB mRNA in the control group, the OGD/R + si-NC

group and the OGD/R + si-CTSB group. (B) Representative

western blot of CTSB protein in the Control, OGD/R + si-NC and

OGD/R + si-CTSB groups. GAPDH was used as the loading

control. (C) Densitometric semi-quantification of CTSB protein

expression (normalized to GAPDH). (D) Cell Counting Kit-8 detected

the viability of Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC

and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB groups. (E) LDH activity of Caco-2

cells was detected in the control, OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC and OGD/R (4

h) + si-CTSB groups. (F) WB analysis of the protein

expression of CTSB, ZO-1 and claudin-1 in control, OGD/R (4 h) +

si-NC and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB Caco-2 cell groups, and (G)

semi-quantitative analysis. Immunofluorescence analysis of (H) ZO-1

and (I) claudin-1 in Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R (4 h) +

si-NC, and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB groups. Magnification, ×40.

All data were obtained from at least three independent biological

experiments (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control;

#P<0.05 vs. OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC. CTSB, cathepsin B;

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NC, negative control; OGD/R,

oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; si, small interfering;

WB, western blot. |

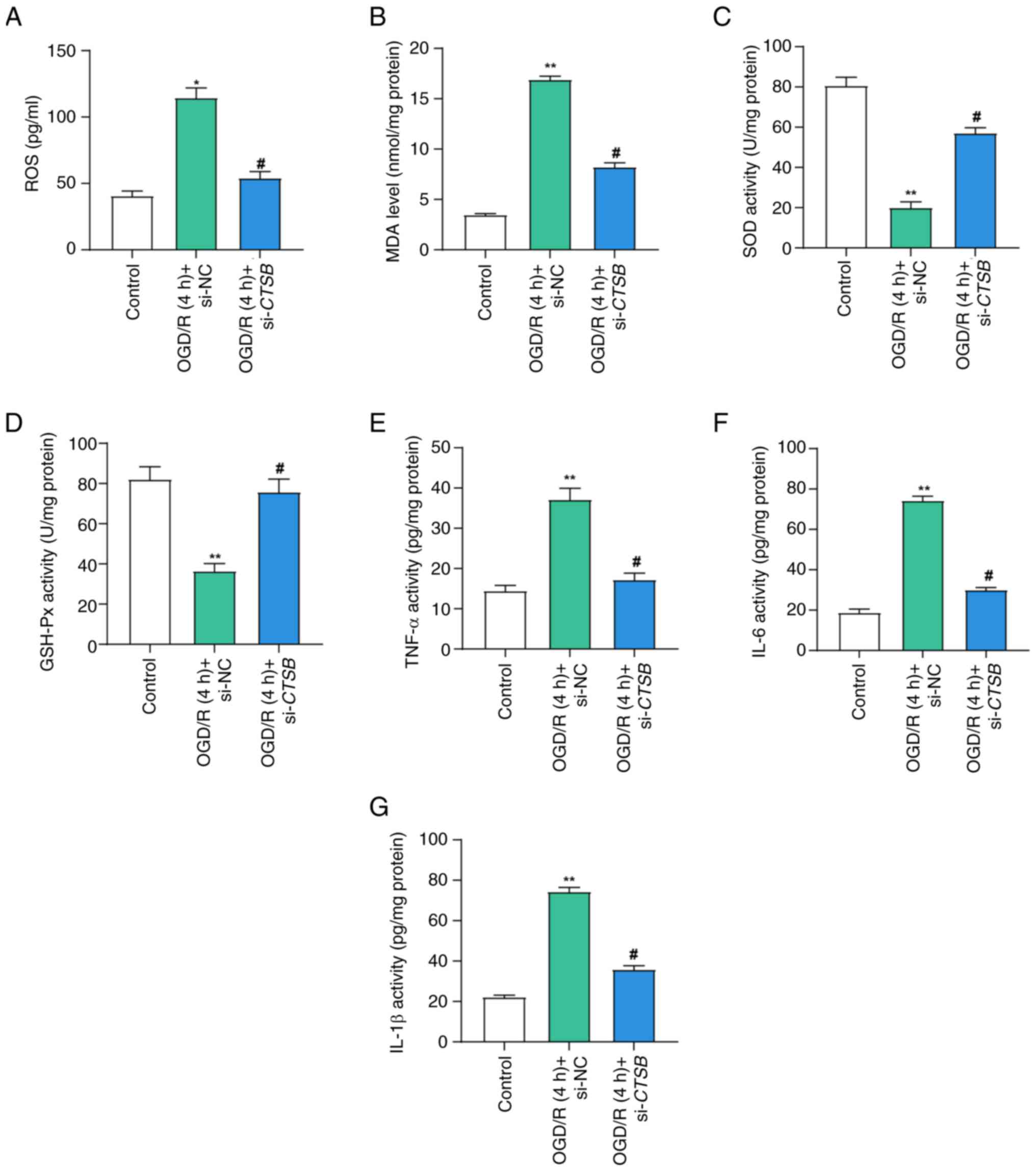

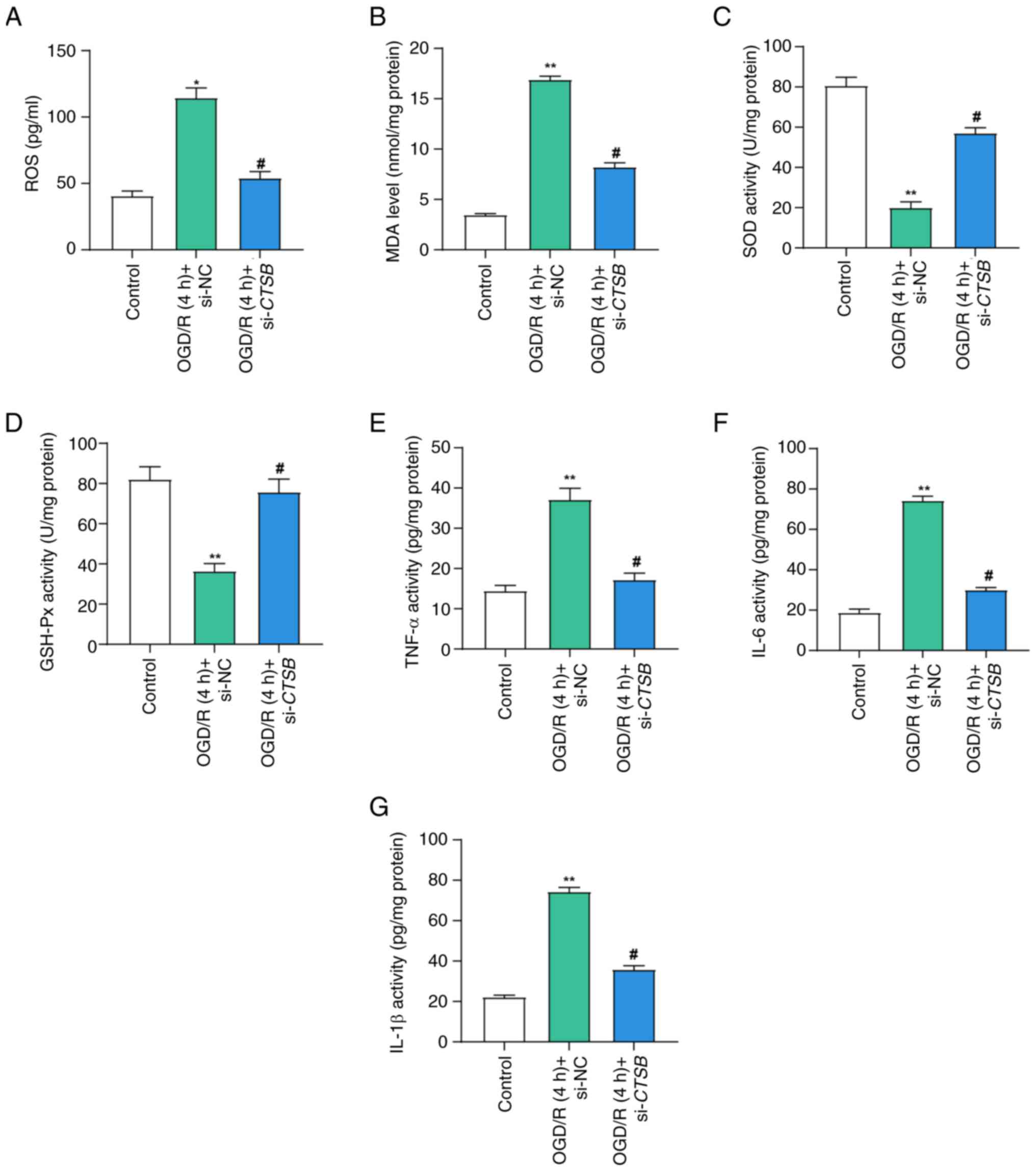

CTSB knockdown alleviates

OGD/R-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory response

To elucidate the role of CTSB in oxidative

stress and inflammatory responses within I/R-injured Caco-2 cells,

a series of experiments were conducted. The levels of ROS in the

OGD/R model, as assessed using an assay kit, were significantly

higher than those in the control group, indicating an increase in

oxidative stress (Fig. 4A).

Notably, CTSB knockdown attenuated this elevation in ROS

levels, suggesting that CTSB serves an important role in

regulating oxidative stress. Furthermore, MDA levels, evaluated

using an MDA detection kit, were markedly elevated in the OGD/R

model group compared with those in the control group, whereas

CTSB knockdown mitigated this increase (Fig. 4B), indicating a reduction in lipid

peroxidation. SOD activity, which was markedly decreased in the

OGD/R model group, was partially restored following CTSB

knockdown (Fig. 4C), suggesting an

enhancement in antioxidative capacity. Similarly, GSH-Px activity,

which was significantly decreased in the OGD/R model group, was

reversed by CTSB knockdown (Fig. 4D), further supporting its role in

oxidative stress regulation. The results of ELISA revealed that the

OGD/R model group exhibited higher levels of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α; by contrast,

CTSB knockdown significantly reduced the levels of these

inflammatory markers (Fig. 4E-G).

Collectively, these findings suggested that CTSB knockdown

may alleviate oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in Caco-2

cells following I/R injury, thereby highlighting the potential

therapeutic benefits of targeting CTSB in this context.

| Figure 4.CTSB knockdown mitigates

ischemia-reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and inflammation.

Detection of (A) ROS levels, (B) MDA levels, (C) SOD activity and

(D) GSH-Px activity in Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R (4 h) +

si-NC and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB groups. Enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay detected the activities of the cytokines (E)

TNF-α, (F) IL-6 and (G) IL-1β in Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R

(4 h) + si-NC and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB groups. All data

were obtained from at least three independent biological

experiments (n=3). **P<0.01 vs. control; #P<0.05

vs. OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC. CTSB, cathepsin B; GSH-Px,

glutathione peroxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde; NC, negative control;

OGD/R, oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; si, small interfering; SOD, superoxide

dismutase. |

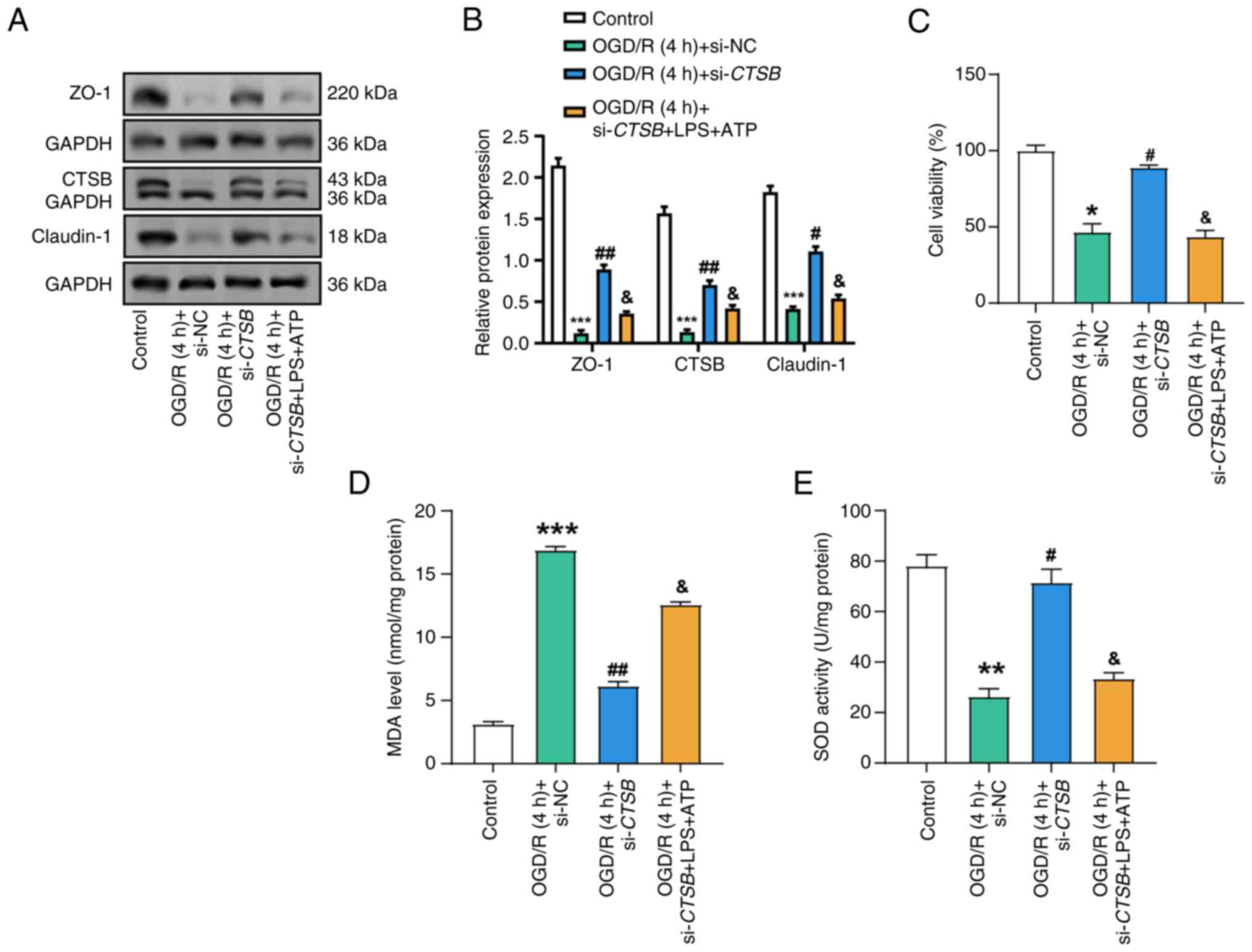

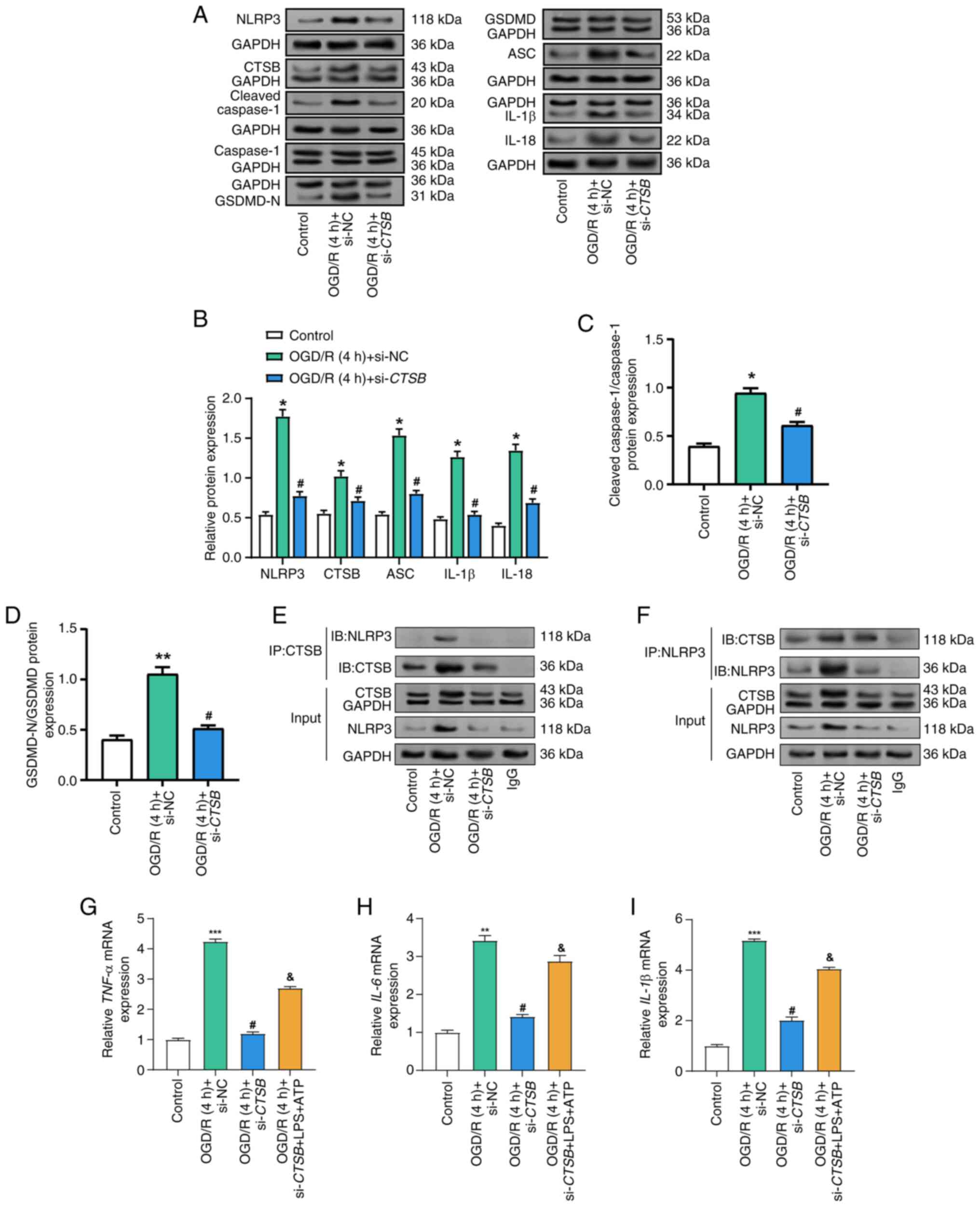

CTSB knockdown attenuates

OGD/R-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and proinflammatory

cytokine expression

To investigate the role of CTSB in the

inflammatory responses induced by OGD/R in Caco-2 cells, the

expression of key inflammasome components and pro-inflammatory

cytokines was examined. WB analysis revealed that OGD/R treatment

significantly elevated the protein expression levels of GSDMD-N,

NLRP3, ASC, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1β and IL-18 compared with those

in the control group (Fig. 5A-D).

However, CTSB knockdown effectively reduced the protein

levels of these inflammatory mediators. Given the pivotal role of

CTSB in the inflammatory process, the current study aimed to

explore whether CTSB directly interacts with NLRP3, a key component

of the inflammasome. Notably, a previous study has suggested an

interaction exists between CTSB and NLRP3 (11). To further investigate this, co-IP

experiments were conducted. The results confirmed that CTSB

interacts with NLRP3 in the intestinal I/R model (Fig. 5E and F). When CTSB was

immunoprecipitated (Fig. 5E),

NLRP3 was detected only in the OGD/R + si-NC group. This is

consistent with the strong induction of NLRP3 by OGD/R and its

marked reduction after CTSB silencing, rendering the

co-precipitated NLRP3 in the control and OGD/R + si-CTSB

groups below the detection limit. Conversely, when NLRP3 was

immunoprecipitated (Fig. 5F), CTSB

was recovered in all groups because CTSB is constitutively

expressed, with the signal highest in the OGD/R + si-NC groups and

decreased after CTSB knockdown. These reciprocal co-IP

findings support a specific CTSB-NLRP3 interaction in this model.

Furthermore, OGD/R treatment significantly elevated the mRNA

expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 5G-5I), whereas CTSB knockdown

markedly decreased the expression levels of these cytokines.

Notably, when cells were further treated with LPS and ATP following

CTSB knockdown, cytokine expression was partially restored,

suggesting a CTSB-independent pathway of inflammatory

activation.

| Figure 5.Knockdown of CTSB inhibits

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in Caco-2 cells injured by

OGD/R. (A) Representative WB analysis of inflammasome-related

proteins in Caco-2 cells under control conditions, OGD/R (4 h) +

si-NC and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB. Each GAPDH blot shown

corresponds to the target protein immediately above it.

Semi-quantitative analysis of protein expression levels: (B) NLRP3,

CTSB, ASC, IL-1β and IL-18; (C) cleaved caspase-1/caspase-1 ratio;

and (D) GSDMD-N/GSDMD ratio. (E) Co-IP of CTSB and NLRP3 (IP: CTSB;

IB: NLRP3 and CTSB). Inputs and IgG controls are shown. (F)

Reciprocal co-IP (IP: NLRP3; IB: CTSB and NLRP3) confirming the

interaction between CTSB and NLRP3 under OGD/R conditions. Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR detection of the relative mRNA

expression levels of the cytokines (G) TNF-α, (H)

IL-6 and (I) IL-1β in Caco-2 cells in the control,

OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC, OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB and OGD/R (4 h) +

si-CTSB + LPS + ATP groups. All data were obtained from at

least three independent biological experiments (n=3). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. control; #P<0.05 vs.

OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC; &P<0.05 vs. OGD/R (4 h) +

si-CTSB. ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CTSB, cathepsin B;

GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-N, cleaved N-terminal GSDMD; IB,

immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NC,

negative control; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3;

OGD/R, oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; si, small

interfering; WB, western blot. |

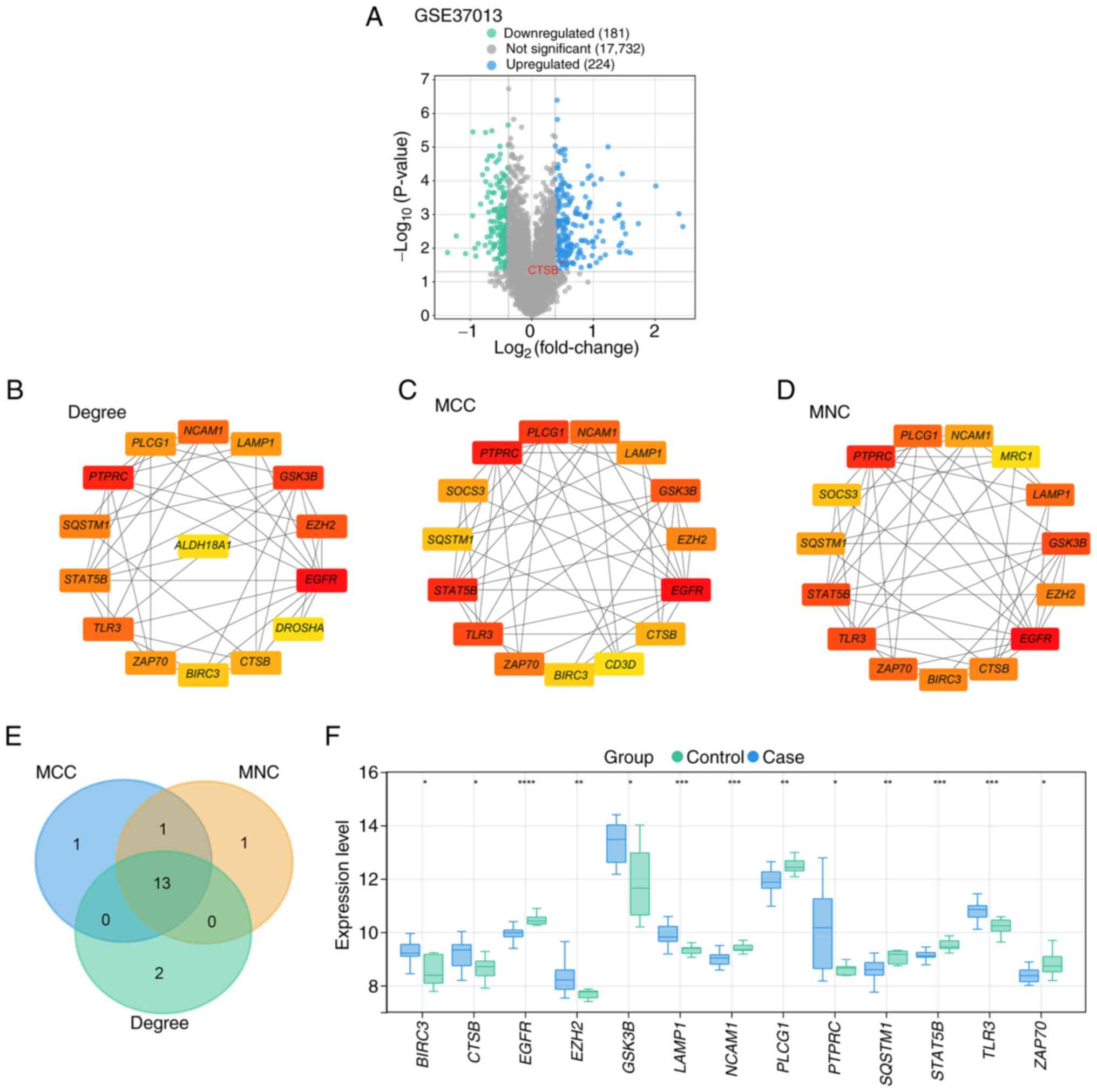

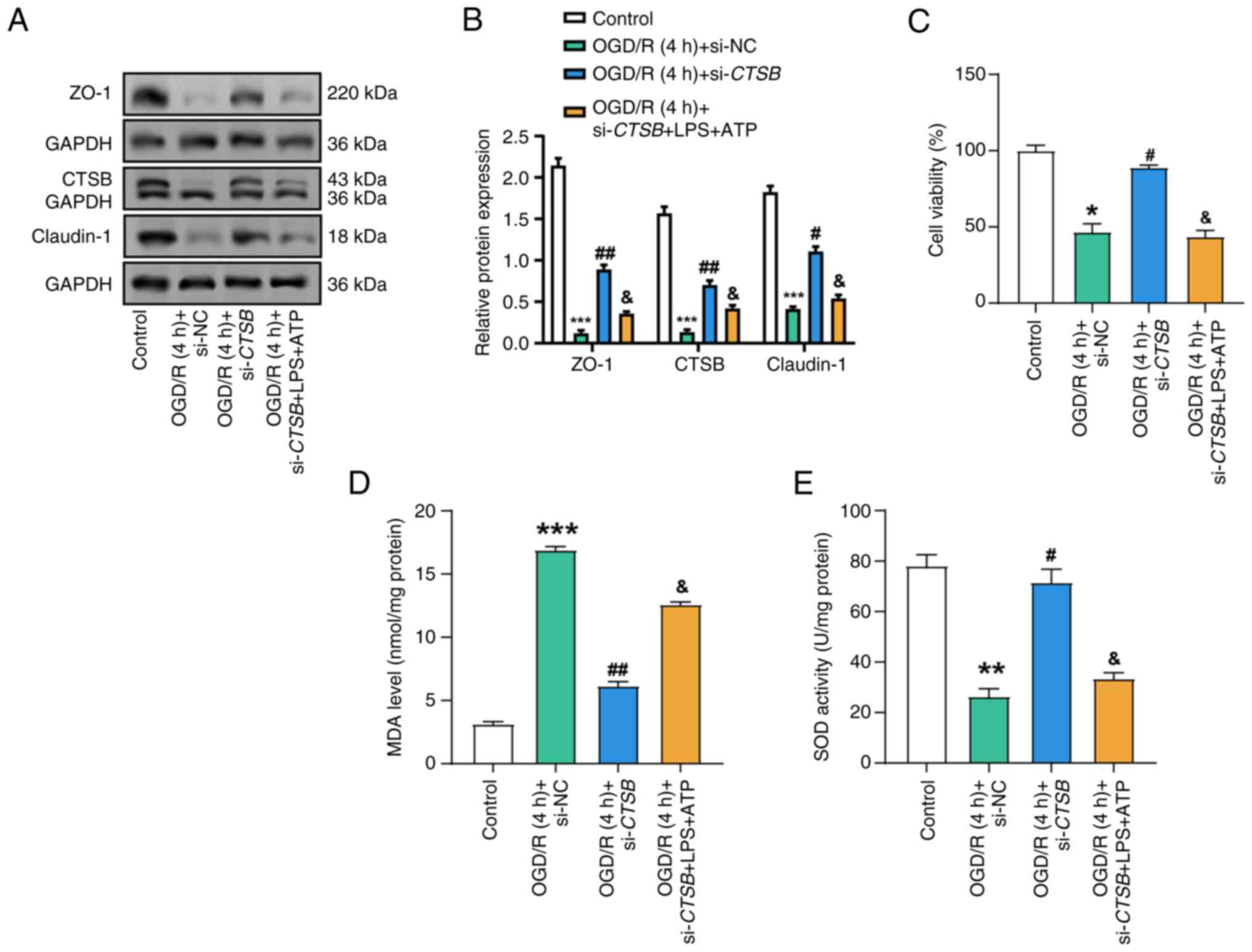

CTSB knockdown alleviates

OGD/R-induced oxidative stress and impaired intestinal barrier

function

Compared with those in the control group, WB

analysis demonstrated that OGD/R treatment significantly reduced

the expression levels of tight junction proteins, specifically ZO-1

and claudin-1 (Fig. 6A and B).

However, CTSB knockdown significantly restored these protein

levels. Notably, further treatment with LPS and ATP following

CTSB knockdown partially reversed this recovery, suggesting

a regulatory role of CTSB in maintaining tight junction integrity

under inflammatory conditions. This suggests that LPS and ATP may

counteract the benefits of CTSB knockdown. The results of

the cell viability experiment indicated a substantial decrease in

cell viability following OGD/R treatment compared with that in the

control group (Fig. 6C). By

contrast, CTSB knockdown significantly enhanced cell

viability under OGD/R conditions, indicating its protective effect;

however, the subsequent addition of LPS and ATP attenuated this

protective effect, suggesting that LPS and ATP may counteract the

benefits of CTSB knockdown. Subsequently, it was revealed

that MDA levels in OGD/R-treated cells were significantly elevated,

indicating an increase in oxidative stress (Fig. 6D). By contrast, CTSB

knockdown significantly reduced MDA levels, demonstrating its

antioxidant potential; however, treatment with LPS and ATP

partially reversed this decrease, suggesting that LPS and ATP may

exacerbate oxidative stress despite CTSB knockdown.

Furthermore, OGD/R-treated cells exhibited a substantial reduction

in SOD activity, which was restored by CTSB knockdown

(Fig. 6E). Notably, the protective

impact of CTSB knockdown on SOD activity was, however,

diminished by subsequent LPS and ATP treatment, further emphasizing

the complex interplay between CTSB, inflammation and

oxidative stress.

| Figure 6.Effects of CTSB knockdown and

LPS + ATP treatment on cell viability, oxidative stress and tight

junction protein expression in OGD/R-treated Caco-2 cells. (A)

Western blot analysis of the protein expression of CTSB, ZO-1 and

claudin-1 in Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC,

OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB and OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB + LPS

+ ATP groups, and (B) semi-quantitative analysis. (C) Cell Counting

Kit-8 detected the viability of Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R

(4 h) + si-NC, OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB and OGD/R (4 h) +

si-CTSB + LPS + ATP groups. Detection of (D) MDA levels and

(E) SOD activity in Caco-2 cells in the control, OGD/R (4 h) +

si-NC, OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB and OGD/R (4 h) +

si-CTSB + LPS + ATP groups. All data were obtained from at

least three independent biological experiments (n=3). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. Control. #P<0.05,

##P<0.01 vs. OGD/R (4 h) + si-NC.

&P<0.05 vs. OGD/R (4 h) + si-CTSB + LPS +

ATP. ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CTSB, cathepsin B; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; MDA, malondialdehyde; NC, negative control;

OGD/R, oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation; si, small

interfering; SOD, superoxide dismutase. |

Discussion

I/R injury represents a complex pathogenic process

that arises from the transient interruption of blood flow, followed

by the reintroduction of oxygen to tissues; this sequence of events

precipitates cellular damage and inflammation (19). Previous studies have identified the

critical molecular mediators in I/R injury, elucidating their roles

in amplifying tissue destruction and inflammatory responses. For

example, research has demonstrated the involvement of microRNAs

(miRs) in I/R. Specifically, the overexpression of miR-146a-5p has

been shown to target TXNIP, modulating the PRKAA/mTOR

pathway, which in turn inhibits autophagy and mitigates intestinal

barrier damage (20). Through

rigorous bioinformatics analysis, the present study identified

several genes that exhibit significant differential expression in

the context of I/R injury. Some of these genes have already been

validated in prior studies for their association with I/R. For

example, PTPRC has emerged as a potential focal point for

pharmacotherapy targeting I/R damage (21). Furthermore, in an I/R-induced mouse

model, TLR3 expression has been reported to be elevated in

the intestinal mucosa, and its knockdown was found to reduce

apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells and lower levels of

inflammatory cytokines post-I/R (22). Additionally, TLR4 has been

implicated in exacerbating I/R injury by augmenting the NF-κB

signaling pathway (23). Although

CTSB has been recognized as a pivotal contributor to I/R

injury in various organs, exacerbating renal I/R injury through

apoptosis, inflammation and dysregulation of autophagy (24), and amplifying myocardial I/R

inflammatory injury via the NLRP3 inflammasome (12), dedicated studies on its specific

role in I/R injury remain sparse (25,26).

Consequently, knowledge gaps persist regarding the regulatory

mechanisms of CTSB, the breadth of its impact across diverse

tissues and its potential as a therapeutic target. By conducting a

comprehensive bioinformatics analysis, CTSB has been

identified as a hub gene that is upregulated during I/R injury.

Given the lack of research on CTSB in the context of I/R

injury and its demonstrated capacity to mediate cellular responses

during this process, CTSB was chosen as the focus of the

current study. The objective of the study was to systematically and

precisely elucidate its regulatory mechanisms, and to assess its

influence on the pathophysiology of I/R injury, thereby addressing

a crucial void in current research.

The lysosomal enzyme CTSB serves a pivotal role in

regulating oxidative stress, inflammation and cell death (24). For example, in cells infected with

a high dosage of Legionella pneumophila, knockdown of

CTSB has been shown to effectively suppress cell death and

inflammation (27). Prior research

has also indicated that inhibiting CTSB can mitigate

intestinal epithelial cell death and safeguard barrier function

(10). Elevated CTSB levels

have been reported to be associated with heightened inflammation

and cellular damage in IBD (28).

The in vivo process of I/R injury is frequently simulated

using the OGD/R approach, which facilitates comprehension of the

complex mechanisms underlying I/R damage, including oxidative

stress, inflammation and apoptosis (29). The current study successfully

replicated I/R-induced inflammation and intestinal barrier

disruption in Caco-2 cells by employing the well-established OGD/R

in vitro model. Caco-2 cells subjected to OGD/R exhibited

decreased cell viability, disruption of tight junction proteins,

increased LDH release, and elevated CTSB protein levels and

activity. Research has shown that IL-28A can protect the expression

of occludin, ZO-1 and claudin-1, thereby enhancing the function of

the epithelial barrier and reducing damage caused by intestinal I/R

(30). A reduction in the

expression of tight junction proteins can exacerbate inflammatory

responses, augment vascular permeability and compromise tissue

barrier function (31). These

adverse effects were alleviated by CTSB knockdown, which

also enhanced cell survival, diminished LDH release and restored

tight junction protein levels. These findings suggest that

CTSB knockdown may shield Caco-2 cells from damage induced

by OGD/R. CTSB could thus serve as a key mediator of

I/R-induced damage by diminishing cell viability and disrupting

barrier proteins.

I/R injury is closely associated with oxidative

stress, a pathological state characterized by an imbalance between

the antioxidant defense mechanisms of the body and the generation

of ROS (32). Within the framework

of I/R, oxidative stress has been extensively studied, with

compelling evidence indicating its pivotal role in tissue damage.

For example, by promoting sirtuin 1-mediated suppression of

epithelial ROS generation and apoptosis, the knockdown of

miR-34a-5p has been shown to mitigate I/R-induced harm (33). Furthermore, oxidative stress

indicators, such as MDA, SOD and GSH-Px, are commonly utilized to

assess antioxidant capability and oxidative damage (34). Research has demonstrated that in

I/R-injured cells, dexmedetomidine can alleviate oxidative stress

by decreasing MDA levels and increasing SOD levels (35). Additionally, elevated GSH-Px

activity in I/R injury can reduce oxidative stress, as it is often

associated with enhanced antioxidant defense (36). Caco-2 cells originate from human

colorectal adenocarcinoma but differentiate into enterocyte-like

cells that form tight junctions and exhibit absorptive and barrier

properties similar to intestinal epithelial cells (37,38).

Therefore, in the current study, Caco-2 cells were selected as an

in vitro model to investigate intestinal I/R injury. The

present study explored how CTSB regulates oxidative stress

in Caco-2 cells subjected to I/R injury. The OGD/R model revealed a

significant elevation in cellular oxidative stress levels; however,

this increase was attenuated by CTSB knockdown. These

findings suggest the potential of CTSB as a therapeutic

target to mitigate oxidative damage, implying its contribution to

oxidative stress in I/R injury.

I/R injury exacerbates tissue damage and impedes the

healing process by triggering a robust inflammatory response

(1,39). The NLRP3 inflammasome, a

multiprotein complex that is instrumental in activating

inflammatory cytokines, serves as a crucial mediator of this

inflammatory cascade (40).

Numerous studies have identified the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome

in I/R injury, with its activation leading to heightened

inflammation and tissue damage (18,41).

For example, VX-765 has been shown to mitigate I/R-induced

harm and alleviate oxidative stress by diminishing NLRP3

inflammasome activation (42).

Additional research has highlighted the strong association between

CTSB and the NLRP3 inflammasome (43). The activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome, which is induced by CTSB, along with the

maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, can be

significantly inhibited by Ilex saponin I (ISI) (25). Concurrently, by disrupting the

CTSB/NLRP3 complex, ISI curtails the inflammatory response through

inactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. According to Li et

al (44), hollow cerium-oxide

(CeO2) nanospheres coated with non-stoichiometric copper

oxide (Cu5.4O) (abbreviated as

hCeO2@Cu5.4O nanoparticles) can

reduce inflammation by modifying the CTSB-NLRP3 signaling pathway.

The experimental findings of the current study demonstrated that

the OGD/R model exhibited elevated levels of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, and that CTSB knockdown markedly reduced these

levels while obstructing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. These

results underscore the pivotal role of CTSB in modulating

NLRP3 inflammasome activation, offering promising therapeutic

implications for alleviating I/R-induced intestinal inflammation.

Notably, a direct interaction exists between CTSB and NLRP3, and it

has been shown that CTSB can activate NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles

through direct engagement with NLRP3 (45). This interaction may involve direct

modification of NLRP3 by CTSB or may indirectly influence NLRP3

activity by altering the intracellular milieu. Additionally, the

release of CTSB may activate the NLRP3 inflammasome via lysosomal

rupture. In the current study, through co-IP experiments, the

presence of a direct interaction between CTSB and NLRP3 was

confirmed in an intestinal I/R model. This finding provides

molecular-level evidence that CTSB may regulate its activity by

directly interacting with NLRP3.

In the current study, it was observed that in

CTSB-knockdown Caco-2 cells, the levels of inflammatory

factors, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, were partially restored

following LPS and ATP treatment. This observation suggests that

while CTSB has a pivotal role in the inflammatory response

induced by I/R injury, other regulators or pathways may circumvent

the inhibitory effects of CTSB knockdown, thereby partially

reinstating the inflammatory response. CTSB is crucial in

I/R injury through its activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a

process essential for the maturation of inflammatory factors, and

CTSB can directly bind to NLRP3 and enhance its activity (11). In the present study, CTSB

knockdown significantly suppressed OGD/R-induced NLRP3 inflammasome

activation and inflammatory factor expression, further

corroborating the key regulatory role of CTSB in I/R injury.

LPS and ATP are well-established activators of the NLRP3

inflammasome, functioning through distinct signaling pathways. LPS

activates NF-κB via the TLR4 signaling pathway, promoting the

transcription of inflammatory factors (20). Conversely, ATP enters the cell

through the P2X7 receptor and pannexin-1 channel, thereby

activating the NLRP3 inflammasome (33). The partial recovery of inflammatory

factors following LPS + ATP treatment in CTSB-knockdown

cells may indicate that these alternative pathways can bypass the

inhibitory effects of CTSB knockdown and reactivate the

NLRP3 inflammasome. Although CTSB has a critical role in the

inflammatory response, the recovery of inflammatory factors after

LPS + ATP treatment suggests that CTSB may not be the sole

regulator. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome involves

multiple signaling pathways, including ROS generation,

mitochondrial damage and lysosomal rupture (33). In the context of CTSB

knockdown, other signaling pathways may be activated by LPS and

ATP, thereby partially restoring the levels of inflammatory

factors. For example, research has shown that ISI can inhibit the

inflammatory response by disrupting the CTSB/NLRP3 complex;

however, this inhibition is not absolute, implying the existence of

other compensatory mechanisms (40). This phenomenon does not undermine

the significance of CTSB as a potential therapeutic target.

Instead, it underscores the complexity of the inflammatory response

and suggests that co-targeting multiple key molecules may be

necessary to effectively inhibit the inflammatory response in

clinical settings. For example, combined inhibition of CTSB

and the TLR4 signaling pathway may prove more effective than

inhibiting CTSB alone.

The present study was confined to in vitro

experiments utilizing a Caco-2 cell model to simulate I/R injury.

While in vitro models can offer valuable insights into the

mechanism of action of CTSB in I/R injury, these findings

necessitate further validation in in vivo models. For

example, future investigations could employ mouse I/R models to

assess the effects of CTSB knockdown or inhibition on

intestinal injury, inflammatory response and oxidative stress. Such

in vivo validation would aid in determining the clinical

potential of CTSB as a therapeutic target. In the present

study, despite CTSB knockdown significantly reducing the

levels of inflammatory factors, these factors remained slightly

elevated following LPS + ATP stimulation. This suggests that, in

the absence of CTSB, other inflammasomes or alternative

pathways may be activated, thus promoting the inflammatory

response. Future studies are warranted to further explore these

potential mechanisms, such as conducting a detailed analysis of the

signaling pathways activated by LPS and ATP using specific

inflammasome inhibitors or by knocking out other inflammasome

components. Additionally, investigating the interaction between

CTSB and other lysosomal enzymes or proteases may provide clues to

understanding the compensatory mechanisms at play. It was

hypothesized that the interaction between CTSB and NLRP3 may occur

through multiple molecular mechanisms. CTSB may directly bind to

NLRP3 and enhance the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby

promoting the maturation and release of inflammatory factors.

Furthermore, CTSB may indirectly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome by

affecting the integrity and function of lysosomes. However, a

limitation of the current study is the lack of further verification

regarding the specific details of CTSB activating NLRP3 through

lysosomal rupture. Future studies may further verify this using

advanced tools such as co-IP, mass spectrometry and lysosomal

functional imaging techniques. Although the present study provides

evidence for the critical role of CTSB in I/R injury,

further research is needed to translate these findings into

clinical applications. Future work should include validating the

therapeutic effects of CTSB in in vivo models, and

developing small-molecule inhibitors or gene therapy strategies

targeting CTSB. Additionally, studying the role of

CTSB in different tissues and cell types may help to devise

more specific treatment options to reduce inflammation and tissue

damage in I/R-related diseases.

In conclusion, the present study identified

CTSB as a pivotal regulator of I/R-induced damage in Caco-2

cells, underscoring its critical role in intestinal barrier

dysfunction, inflammation and oxidative stress. Notably,

CTSB knockdown effectively mitigated cellular damage by

reducing oxidative stress, restoring tight junction proteins and

modulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Conversely, CTSB

expression was significantly upregulated under OGD/R conditions.

These findings elucidate how CTSB orchestrates inflammatory

signals and influences intestinal barrier function during I/R

injury.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the Key Specialty Construction Project

of the Pudong Health Commission of Shanghai (grant no.

PWZzk2022-09) and the Qihang Project of Shanghai Pudong New Area

People's Hospital (grant no. PRYQH202502).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SH, LW, ZW, HX and YW conceived and designed the

research. SH, LW and ZW acquired the data. SH, LW, ZW, SY, QZ, YX

and YJ analyzed and interpreted the data. SY, QZ, YX and YJ

performed statistical analysis. SH, LW and ZW drafted the

manuscript. HX and YW revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. SH and HX confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wang J, Zhang W and Wu G: Intestinal

ischemic reperfusion injury: Recommended rats model and

comprehensive review for protective strategies. Biomed

Pharmacother. 138:1114822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li G, Wang S and Fan Z: Oxidative stress

in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Front Med (Lausanne).

8:7507312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang J, Liu Z, Liu Y, Shi Y, Chen F and

Leng Y: Role of non-coding RNA in the pathogenesis of intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Curr Med Chem. 30:4130–4148. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li Y, Feng D, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Sun R, Tian

D, Liu D, Zhang F, Ning S, Yao J and Tian X: Ischemia-induced ACSL4

activation contributes to ferroptosis-mediated tissue injury in

intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Death Differ. 26:2284–2299.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Meng Q, Ye C and Lu Y: miR-181c regulates

ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced neuronal cell death by

regulating c-Fos signaling. Pharmazie. 75:90–93. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zu G, Zhou T, Che N and Zhang X:

Salvianolic acid A protects against oxidative stress and apoptosis

induced by intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury through

activation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Cell Physiol Biochem.

49:2320–2332. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wu L, Xiong X, Wu X, Ye Y, Jian Z, Zhi Z

and Gu L: Targeting oxidative stress and inflammation to prevent

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Mol Neurosci. 13:282020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hook G, Reinheckel T, Ni J, Wu Z, Kindy M,

Peters C and Hook V: Cathepsin B gene knockout improves behavioral

deficits and reduces pathology in models of neurologic disorders.

Pharmacol Rev. 74:600–629. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

De Pasquale V, Moles A and Pavone LM:

Cathepsins in the pathophysiology of mucopolysaccharidoses: New

perspectives for therapy. Cells. 9:9792020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hu ML, Liao QZ, Liu BT, Sun K, Pan CS,

Wang XY, Yan L, Huo XM, Zheng XQ, Wang Y, et al: Xihuang pill

ameliorates colitis in mice by improving mucosal barrier injury and

inhibiting inflammatory cell filtration through network regulation.

J Ethnopharmacol. 319:1170982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dong L, Xie J, Wang Y, Jiang H, Chen K, Li

D, Wang J, Liu Y, He J, Zhou J, et al: Mannose ameliorates

experimental colitis by protecting intestinal barrier integrity.

Nat Commun. 13:48042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu C, Yao Q, Hu T, Cai Z, Xie Q, Zhao J,

Yuan Y, Ni J and Wu QQ: Cathepsin B deteriorates diabetic

cardiomyopathy induced by streptozotocin via promoting

NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 30:198–207.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhao S, Gong Z, Zhou J, Tian C, Gao Y, Xu

C, Chen Y, Cai W and Wu J: Deoxycholic acid triggers NLRP3

inflammasome activation and aggravates DSS-induced colitis in mice.

Front Immunol. 7:5362016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu M, Wen H, Zuo L, Song X, Geng Z, Ge S,

Ge Y, Wu R, Chen S, Yu C and Gao Y: Bryostatin-1 attenuates

intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced intestinal barrier

dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress via activation of

Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. FASEB J. 37:e229482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao Y, Zhuang Y, Shi J, Fan H, Lv Q and

Guo X: Cathepsin B induces kidney diseases through different types

of programmed cell death. Front Immunol. 16:15353132025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kip AM, Grootjans J, Manca M, Hadfoune MH,

Boonen B, Derikx JPM, Biessen EAL, Olde Damink SWM, Dejong CHC,

Buurman WA and Lenaerts K: Temporal transcript profiling identifies

a role for unfolded protein stress in human gut

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

13:681–694. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang Z, Li Z, Feng D, Zu G, Li Y, Zhao Y,

Wang G, Ning S, Zhu J, Zhang F, et al: Autophagy induction

ameliorates inflammatory responses in intestinal

Ischemia-reperfusion through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome

activation. Shock. 52:387–395. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nadatani Y, Watanabe T, Shimada S, Otani

K, Tanigawa T and Fujiwara Y: Microbiome and intestinal

ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 63:26–32. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhenzhen L, Wenting L, Jianmin Z, Guangru

Z, Disheng L, Zhiyu Z, Feng C, Yajing S, Yingxiang H, Jipeng L, et

al: miR-146a-5p/TXNIP axis attenuates intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting autophagy via the

PRKAA/mTOR signaling pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 197:1148392022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cong R, Yang J, Zhou J, Shi J, Zhu Y, Zhu

J, Xiao J, Wang P, He Y and He B: The potential role of protein

tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type C (CD45) in the intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Comput Biol. 27:1303–1312. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang XY, Liang HS, Hu JJ, Wan YT, Zhao J,

Liang GT, Luo YH, Liang HX, Guo XQ, Li C, et al: Ribonuclease

attenuates acute intestinal injury induced by intestinal ischemia

reperfusion in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 83:1064302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang J, Wu Y, Xu Y, Jia J, Xi W, Deng H

and Tu W: Dexmedetomidine resists intestinal ischemia-reperfusion

injury by inhibiting TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling. J Surg Res.

260:350–358. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu C, Cai Z, Hu T, Yao Q and Zhang L:

Cathepsin B aggravated doxorubicin-induced myocardial injury via

NF-κB signalling. Mol Med Rep. 22:4848–4856. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu J, Chen S, Wu P, Wang Y, Qi X, Zhang R,

Liu Z, Wang D and Cheng Y: Cathepsin B/HSP70 complex induced by

Ilexsaponin I suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation in

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Phytomedicine.

105:1543582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sun C, Cao N, Wang Q, Liu N, Yang T, Li S,

Pan L, Yao J, Zhang L, Liu M, et al: Icaritin induces resolution of

inflammation by targeting cathepsin B to prevents mice from

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 116:1098502023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Morinaga Y, Yanagihara K, Nakamura S,

Hasegawa H, Seki M, Izumikawa K, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yamada Y,

Kohno S and Kamihira S: Legionella pneumophila induces cathepsin

B-dependent necrotic cell death with releasing high mobility group

box1 in macrophages. Respir Res. 11:1582010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Menzel K, Hausmann M, Obermeier F,

Schreiter K, Dunger N, Bataille F, Falk W, Scholmerich J, Herfarth

H and Rogler G: Cathepsins B, L, and D in inflammatory bowel

disease macrophages and potential therapeutic effects of cathepsin

inhibition in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 146:169–180. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu Y, Ji T, Jiang H, Chen M, Liu W, Zhang

Z and He X: Emodin alleviates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion

injury through antioxidant stress, anti-inflammatory responses, and

anti-apoptosis effects via Akt-mediated HO-1 upregulation. J

Inflamm (Lond). 21:252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li L, Zhou C, Li T, Xiao W, Yu M and Yang

H: Interleukin-28A maintains the intestinal epithelial barrier

function through regulation of claudin-1. Ann Transl Med.

9:3652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Brooks TA, Hawkins BT, Huber JD, Egleton

RD and Davis TP: Chronic inflammatory pain leads to increased

blood-brain barrier permeability and tight junction protein

alterations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 289:H738–H743. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Adwas AA, Elsayed A, Azab AE and Quwaydir

FA: Oxidative stress and antioxidant mechanisms in human body. J

Appl Biotechnol Bioeng. 6:43–47. 2019.

|

|

33

|

Wang G, Yao J, Li Z, Zu G, Feng D, Shan W,

Li Y, Hu Y, Zhao Y and Tian X: miR-34a-5p inhibition alleviates

intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced reactive oxygen species

accumulation and apoptosis via activation of SIRT1 signaling.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 24:961–973. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li F, Wang X, Deng Z, Zhang X, Gao P and

Liu H: Dexmedetomidine reduces oxidative stress and provides

neuroprotection in a model of traumatic brain injury via the PGC-1α

signaling pathway. Neuropeptides. 72:58–64. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hou M, Chen F, He Y, Tan Z, Han X, Shi Y,

Xu Y and Leng Y: Dexmedetomidine against intestinal

ischemia/reperfusion injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis

of preclinical studies. Eur J Pharmacol. 959:1760902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ustundag B, Kazez A, Demirbag M, Canatan

H, Halifeoglu I and Ozercan IH: Protective effect of melatonin on

antioxidative system in experimental ischemia-reperfusion of rat

small intestine. Cell Physiol Biochem. 10:229–236. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sambuy Y, De Angelis I, Ranaldi G, Scarino

M, Stammati A and Zucco F: The Caco-2 cell line as a model of the

intestinal barrier: Influence of cell and culture-related factors

on Caco-2 cell functional characteristics. Cell Biol Toxicol.

21:1–26. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Meunier V, Bourrie M, Berger Y and Fabre

G: The human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2;

pharmacological and pharmacokinetic applications. Cell Biol

Toxicol. 11:187–194. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Deng F, Lin ZB, Sun QS, Min Y, Zhang Y,

Chen Y, Chen WT, Hu JJ and Liu KX: The role of intestinal

microbiota and its metabolites in intestinal and extraintestinal

organ injury induced by intestinal ischemia reperfusion injury. Int

J Biol Sci. 18:39812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Moretti J and Blander JM: Increasing

complexity of NLRP3 inflammasome regulation. J Leukoc Biol.

109:561–571. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ito H, Kimura H, Karasawa T, Hisata S,

Sadatomo A, Inoue Y, Yamada N, Aizawa E, Hishida E, Kamata R, et

al: NLRP3 inflammasome activation in lung vascular endothelial

cells contributes to intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute

lung injury. J Immunol. 205:1393–1405. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lyu H, Ni H, Huang J, Yu G, Zhang Z and

Zhang Q: VX-765 prevents intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury by

inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. Tissue Cell. 75:1017182022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cai Z, Xu S and Liu C: Cathepsin B in

cardiovascular disease: Underlying mechanisms and therapeutic

strategies. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e700642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li Y, Xia X, Niu Z, Wang K, Liu J and Li

X: hCeO2@ Cu5.4O nanoparticle alleviates inflammatory responses by

regulating the CTSB-NLRP3 signaling pathway. Front Immunol.

15:13440982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Xu W, Huang Y and Zhou R: NLRP3

inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system

diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 22:341–355. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|