Introduction

As average life expectancy increases and the

population ages, the global disease spectrum shifts (1). Chronic disease multimorbidity has

become common (2), with

multimorbidity rates as high as 55–98% in the elderly population

(3). Notably, patients with

multimorbidities tend to be in poorer health, with higher rates of

mortality and disability, leading to an increased consumption of

healthcare resources (4).

Osteoarthritis (OA) and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are common

chronic degenerative diseases and their combination is a frequent

type of multimorbidity (5). The

two diseases are the leading causes of disability and death in

individuals aged >65 years, respectively (6–8) and

their progressively higher incidence and increasingly younger onset

cause a heavy burden of disease (9–11),

posing a notable threat to health.

Knee OA (KOA) is the most common type of OA and

>50% of patients with symptomatic KOA experience severe

disability with limited activities of daily living (12). Atherosclerosis (AS), as the most

important etiological and pathological basis of CVDs (13), contributes to ~45% of

CVD-associated mortalities and >20 million individuals worldwide

succumb to AS each year (14). A

large number of existing epidemiological studies have confirmed the

association between OA and CVDs (15). Individuals with OA have a higher

risk of developing and dying from CVDs (16–19)

and the severity of OA is associated with CVD mortality.

Furthermore, individuals at high risk of CVDs have a higher

probability of developing OA (20)

and high levels of AS markers are associated with a high prevalence

of imaging KOA (21,22). Previous studies have also shown

that popliteal artery wall thickness is positively associated with

tibial cartilage loss (23,24).

This evidence indicates that OA and CVDs may be caused by common

risk factors, or that other complex and as yet unappreciated

associations between them exist.

Using KOA and AS as an entry point, the present

study aimed to explore the link between KOA and AS to enrich the

research base of OA-CVD multimorbidities. For the two main disease

subtypes under consideration, KOA and AS share common risk factors,

such as age, obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and abnormal

lipid metabolism (25). A previous

study suggested that metabolic syndrome mediates the development of

KOA-AS multimorbidity (16), but

confirmatory studies are lacking. Multi-omics technology is a

research method that can be used to carry out a more comprehensive

exploration by integrating data from different histological levels,

thus fully revealing the characteristics of disease. In order to

determine whether metabolic abnormalities serve a key role in

KOA-AS multimorbidity and to identify which key biomolecules are

associated with KOA-AS multimorbidity, differences in

metabolism-related clinical indices among different diseased

populations were analyzed. In addition, possible evidence was

explored at the molecular level through multi-omics analysis, which

may improve the understanding of the relationship between KOA and

AS, further promote the prevention and treatment of KOA-AS and

improve future multimorbidity prevention and disease

management.

Materials and methods

Study population

After excluding individuals unable to undergo

radiological examination or those with severe underlying diseases,

172 subjects from Peking University Shougang Hospital (age, 20–60

years, mean age: 40 years, 71.5% male) undergoing physical

examinations volunteered for additional KOA and AS screening, were

recruited to the present study from July to August 2024. The

subjects were offered additional screening after signing an

informed consent form. Based on the examination results, the

subjects were divided into the following four groups: The healthy

control group (HC), the KOA group, the AS group and the KOA-AS

multimorbidity group (MM). The HC group consisted of healthy

individuals without KOA and AS; KOA group consisted of patients

with KOA without AS; the AS group consisted of patients with AS

without KOA; and the MM group consisted of patients with both KOA

and AS.

Disease screening methods

KOA was diagnosed using American College of

Rheumatology criteria (26). AS

was diagnosed using brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV),

with patients considered to have AS when baPWV was ≥2 times SD.

Patient information

The clinical data of the subjects were derived from

the laboratory information system and mainly included: i) Basic

information, such as sex and age; ii) general examination of

height, weight and body mass index (BMI); iii) laboratory

indicators, including lipids (triglycerides, total cholesterol),

fasting blood glucose and blood pressure (systolic, diastolic); and

iv) a history of previous diseases.

Metabolomics assays

The test samples were derived from residual serum

samples obtained from the aforementioned patient population. The

serum samples were extracted with 80% methanol in water, vortexed

and shaken and then maintained in an ice bath for 5 min. The

samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and a

certain amount of supernatant was diluted with mass spectrometry

(MS)-grade water until the methanol content was 53%. The samples

were again centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the

supernatant was collected and the samples underwent liquid

chromatography (LC)-MS for analysis.

Chromatographic separation was performed using a

Hypersil GOLD column (C18) and an ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide Column

(100×2.1 mm, 1.9 µm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Metabolites

eluted from the column were detected using a Q Exactive HF/Q

Exactive HF-X super-resolution liquid-mass spectrometer (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). MS often uses two scanning modes,

positive ion scanning and negative ion scanning, for data

acquisition during the detection process. In addition, to assess

the stability of the LC-MS throughout the acquisition process,

eight quality control samples were randomly distributed in a pool

of all samples.

Metabolomics analysis

The downstream data files were converted to mzXML

format using ProteoWizard software (version 3.0) (27) and then XCMS software (version 2006)

(28) was used for peak extraction

and peak quantification. Peak alignment was performed and peak area

correction was performed with the first quality control (QC)

sample. Metabolite identification was then performed based on

setting 10 ppm mass deviation and information such as addition ions

against a high-quality secondary spectral database (novogene.cn/).

Subsequently, the background ions were removed with blank sample

measurements and the raw quantitative results of each sample to be

tested were normalized. Finally, compounds with a coefficient of

variation (CV) of the relative peak area of >30% in the QC

samples were deleted (29) and the

number of metabolites identified and relative quantitative value

results were obtained. The data processing was partially performed

based on a Linux operating system (CentOS Version 6.6; linux.org/)

and R package (version 3.4.3, rstudio.com/) and Python software

(version 3.5.0, http://www.python.org/).

The metabolomics data processing software metaX

(version 2017) (30) was used to

transform the data and partial least squares discriminant analysis

(PLS-DA) was performed to obtain the variable importance in

projection (VIP) values of the metabolites. Univariate analysis was

based on paired t-test to calculate the P-value between the groups

for each metabolite and the multiplicity of difference [fold change

(FC) value] between groups for metabolites. The screening criteria

for differential metabolites were VIP>1, P<0.05 and FC≥2 or

FC≤0.5. Volcano plots were plotted using the R package ggplot2

(R-3.4.3) and clustered heat maps (P<0.05 being statistically

significant; t-test) and the Pearson correlation coefficients heat

maps (r-values≥0.6 indicating moderate strength correlation) were

generated using the pheatmap package (R-3.4.3). In addition,

correlation maps were plotted using the corrplot package

(R-3.4.3)in R.

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) was used to

analyze the function of metabolites and the associated pathways,

which were considered to be enriched when x/n>y/N; the pathways

were considered to be markedly enriched when the P-value of the

pathway was <0.05 and the bubble plots were visualized using the

R package ggplot2.

Transcriptomics data source

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database

(ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) is a gene expression database created by the

NCBI that contains microarray datasets and high-throughput

sequencing data. To understand the changes in gene expression that

may be caused by metabolism, transcriptomics datasets with ~60

years (average age) were searched for. The key words

‘Osteoarthritis’ and ‘Atherosclerosis’ were used to search and

screen the gene expression datasets at the mRNA level for analyzing

the hub genes of KOA-AS multimorbidity. The inclusion and exclusion

criteria for dataset selection were as follows: i) Test specimens

should be Homo sapiens with consistent specimen types; ii)

gene expression profiles should include both case and control

groups; iii) experimental data expression types (sequencing

platforms) should be consistent; iv) preference should be given to

datasets with large sample sizes; and v) patients receiving

clinical interventions should be excluded.

Transcriptomics analysis

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were

identified using the Limma package of the online analysis platform

GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). Based on the

Bayesian test, the criteria for determining the DEGs of the two

profiles were set as adjusted P-value <0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg

method) (31) and |logFC|>0.

The common DEGs were obtained from the Venn diagrams drawn by the

online mapping tool ImageGP (bic.ac.cn/BIC/#/).

The KEGG database was used to analyze the function

of the hub genes and the related biological processes. When

x/n>y/N, the process was considered enriched; when the P-value

of the biological process was <0.05, it was considered markedly

enriched and the bubble plots were visualized with the R package

ggplot2.

The DEGs common to OA and AS were imported into the

STRING (http://www.string-db.org/) database

and a composite score of ≥0.4 was selected for protein-protein

interaction (PPI) network construction, excluding proteins with no

interactions and retaining only proteins in the interaction network

and the results were exported in ‘tsv’ format. The results were

then imported into Cytoscape (32)

and the cytoHubba (https://cytoscape.org/) plug-in was used to assign a

value to each protein according to the topological network

algorithm and the hub genes corresponding to the key proteins were

sorted and screened (33).

Metabolite-gene network analysis

MetaboAnalystR 6.0 (34) was used to analyze the interactions

between core metabolites and hub genes. The ‘Network Analysis’

module was selected online and the ‘Official gene symbol’ of the

hub gene to be analyzed was imported into the database together

with the ‘Compound Name’ of the core metabolite. Subsequently, the

metabolite-gene interaction network was constructed by selecting

the species to identify possible interactions.

Mice and disease models

Disease modeling was performed using 6–8-week-old

male mice (weight, 20–22 g). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice and

APOE−/−mice were purchased from SPF (Beijing)

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. A total of six C57 mice were used as

healthy controls and 18 APOE−/−mice were used to

construct the disease model. Mice were individually housed under

standard lighting conditions (12-h dark/light cycle) and constant

temperature (22±2°C) with free access to standard food and water.

The animal experiments was approved by the Ethics Committee for

Experimental Animals of Beijing JinglaiHuake Biotechnology Co

(approval no. JLHK-20241110-02, approved date November 13, 2024).

During the surgery, experimental animals were anesthetized via

inhalation of isoflurane (5% induction and 2% maintenance) and the

mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation at the time of tissue

sampling. APOE−/− mice were randomly grouped to

construct AS, KOA and KOA-AS multimorbidity models. The AS disease

model was constructed using the high-fat chow-feeding method with

high-fat feeding for 12 weeks; the KOA disease model was surgically

constructed using the modified Hulth method (35); and the KOA-AS multimorbidity model

was constructed using the two techniques. C57 mice used as healthy

controls were fed normal feed without treatment.

X-ray examination

To assess the effects of KOA disease modeling,

radiography was used to assess joint degeneration. To validate the

construction of the KOA disease model, changes such as narrowing of

the joint space and the presence of osteophytes should be

observed.

Oil Red O staining

The aortic Oil Red O staining method was used to

determine the status of the AS disease model. The intact aortic

tissues were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. All

subsequent steps were performed at room temperature. The fixed

tissues were rinsed with PBS and then immersed in 60% isopropanol

for 30 sec. Next, the tissues were stained with Oil Red O working

solution for 30 min, followed by differentiation in 60% isopropanol

for 30 sec. Finally, the tissues were rinsed again with PBS and

imaged on a white background. If notable red atherosclerotic

plaques were detected after staining, the AS disease model was

considered successfully constructed.

ELISA

Concentrations of Egr1 and GSK3β in patient serum

were determined using the Human Egr1 (cat. no. EH0892; Wuhan Fine

Biotech Co., Ltd.) and the Human GSK3β ELISA Kit (cat. no. EH0630;

Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd.), respectively, according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

The concentrations of Egr1 and GSK3β in mouse serum

were determined using the Mouse Egr1 ELISA Kit (cat. no. EM0998;

Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd.) and the Mouse GSK3β ELISA Kit (cat.

no. RXW202270M6; Quanzhou Ruixin Biotechnology Co., Ltd.),

respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The standard curve was fitted and the relative

concentration of the target protein in the samples was obtained

using CurveExpert 1.4 (curveexpert.net/).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated from mouse cartilage tissue using

TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a RT kit (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 11141ES60) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed on a Molarray

MA-6000 real-time fluorescence qPCR instrument. qPCR was performed

using the Realtime PCR Fluorescence Quantitative kit (Shanghai

Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 11201ES08) on a Molarray

MA-6000 real-time fluorescence qPCR system. Thermocycling

conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min;

40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 60°C for

20 sec, and extension at 72°C for 20 sec, followed by a melt curve

stage under instrument default settings. Each sample was run in

three technical replicates. Relative mRNA levels were calculated

with GAPDH as an internal reference, using the

2−ΔΔCq equation (36).

Primer sequences are shown in Table

SI.

Western blotting

Mouse cartilage tissue was lysed with RIPA buffer

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and total protein was

collected. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA

assay kit. A total of 30 µg protein/lane was separated by SDS-PAGE

on 12% gels and were then electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane

(Merck KGaA). After blocking the membranes with protein blotting

closure buffer (Biosharp Life Sciences) for 2 h at room

temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies

targeting Egr1 (1:1,000; cat. no. AF0589; Affinity Biosciences),

GSK3β (1:5,000; cat. no. BF0695; Affinity Biosciences) and GAPDH

(1:50,000; cat. no. 10494-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at 4°C

overnight. After washing three times with TBS-Tween, the membranes

were incubated with HRP-labeled anti-mouse/rabbit IgG secondary

antibodies (1:10,000; cat. no. bs-0295M-HRP; BIOSS) at room

temperature for 1 h. The blots were then visualized using an

enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Beijing Fluorescence

Biotechnology Co. Ltd.). Protein band densitometry was analyzed

using ImageJ software (version 1.53e; National Institutes of

Health, USA).

Analysis of receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curves

To assess the sensitivity and specificity of

metabolites as potential diagnostic markers, a ROC curve analysis

was performed based on the relative quantitative values of

metabolites in the HC and MM groups of the metabolomics assay using

R programming software (version 3.4.3, rstudio.com/). The

confidence interval was set at 95% and metabolites with an area

under the ROC curve (AUC) of >0.7 were considered

significant.

Drug prediction

Small molecule targeted drugs were predicted using

the Drug-Gene Interaction Database (DGidb; http://dgidb.org/), a publicly accessible resource

that aggregates gene or gene product, drug and drug-drug-gene

interaction records, which allows for drug prediction through

genes. In turn, this drives clinical hypothesis generation and

discovery by physicians and researchers (37).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis for the omics portion of the research

methodology was mainly performed using dedicated histological

analysis tools/software or the R software package (version 4.2.2,

rstudio.com/). Data in the epidemiological analysis and validation

experiment were analyzed using SPSS version 25 statistical software

(IBM Corp.), with independent samples t-test used for continuous

variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. For

comparisons across more than two groups, one-way ANOVA followed by

Dunnett's post hoc test was applied. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical indicators analysis

To determine whether KOA-AS multimorbidity was

associated with metabolic abnormalities, healthy controls and three

patient groups were screened based on the diagnosis of KOA-AS

(Table SII). The between-group

differences regarding metabolic syndrome-related indices (BMI,

lipids, blood glucose and blood pressure), as well as medical

history, were comparatively analyzed (Table I).

| Table I.Clinical indicators and KOA-AS

multimorbidity. |

Table I.

Clinical indicators and KOA-AS

multimorbidity.

|

| Clusters |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinical

indicators | HC (n=43) | KOA (n=43) | AS (n=43) | MM (n=43) |

|---|

| BMI | 24.15±3.33 |

26.15±2.94a |

25.69±3.53b |

27.13±3.44c |

| Triglycerides | 1.4±0.98 | 1.42±0.8 |

2.24±1.58a | 2.36±3.21 |

| Total

cholesterol | 4.77±1.03 | 4.96±0.76 | 5.03±1 | 5.15±1.48 |

| Fasting

glucose | 5.16±0.41 |

5.48±0.7b |

5.63±1.12b |

6.73±2.09cde |

| Systolic blood

pressure | 113.86±13.25 | 118.51±12.41 |

131.86±13.97c |

135.42±11.29ce |

| Diastolic blood

pressure | 71.09±7.76 | 73.51±9.29 |

83.86±10.14c |

85.44±9.19ce |

| Past medical

history |

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension | 2/43 | 7/43 | 9/43b | 24/43cef |

|

Hyperlipidemia | 1/43 | 6/43b | 7/43b | 2/43 |

|

Diabetes mellitus | 1/43 | 4/43 | 1/43 | 13/43cfg |

|

Coronary heart disease | 0/43 | 0/43 | 0/43 | 3/43 |

|

Other | 3/43 | 1/43 | 0/43 | 4/43h |

|

Total | 7/43 | 14/43 | 16/43b | 33/43cef |

Among the results, BMI showed differences in the

KOA, AS and MM group compared with that in the HC group.

Triglycerides showed differences only in the comparison between the

AS and the HC group. In general, both triglycerides and total

cholesterol showed an increasing trend in those who had AS (AS and

MM groups) compared with those who did not have AS (HC and KOA

groups). Fasting blood glucose showed differences in all five group

comparisons, suggesting that abnormalities in glucose metabolism

may be associated with both KOA and AS and that this could have a

contributory effect on the development of KOA-AS multimorbidity.

Among all metabolic abnormalities, glucose metabolism was the most

strongly associated with KOA-AS multimorbidity. Systolic blood

pressure (mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) showed

differences in comparisons with the AS, the MM and the HC group and

in comparisons of the MM and the KOA group, indicating that

hypertension may be strongly associated with AS. Notably,

hypertension is a recognized risk factor for AS.

In the analysis of past medical history, a past

history of hypertension and a past history of diabetes mellitus

were associated with KOA-AS multimorbidity. In general, the more

history of past diseases an individual had (all diseases), the

greater the probability of developing KOA-AS multimorbidity,

suggesting that this multimorbidity may be associated with a

variety of adverse health conditions.

Overall, in the analysis of metabolism-related

clinical information, BMI, fasting glucose, a previous history of

hypertension and a previous history of diabetes mellitus were

associated with KOA-AS multimorbidity. By contrast, the laboratory

measures of blood pressure and dyslipidemia were only associated

with AS. Furthermore, at the same age, there was more evidence of

metabolic abnormalities in the AS group compared with in the KOA

group.

Qualitative and quantitative

metabolite analysis

To understand the association between metabolism and

KOA-AS multimorbidity, the study subjects were screened, retaining

redundant serum samples (residual blood from laboratory tests)

among those analyzed in the previous step, the number of sample

cases in the remaining subgroups was adjusted based on the

subgroups with the lowest number of samples according to the ratio

of 1:1 and the ratio of age and sex in each group was balanced as

much as possible (Table SIII).

Non-targeted serum metabolomics based on high-resolution MS was

performed and the molecular peaks were matched and identified using

a high-quality secondary spectral information database to reflect

the differences in the characteristics of serum total metabolites

in different diseased populations.

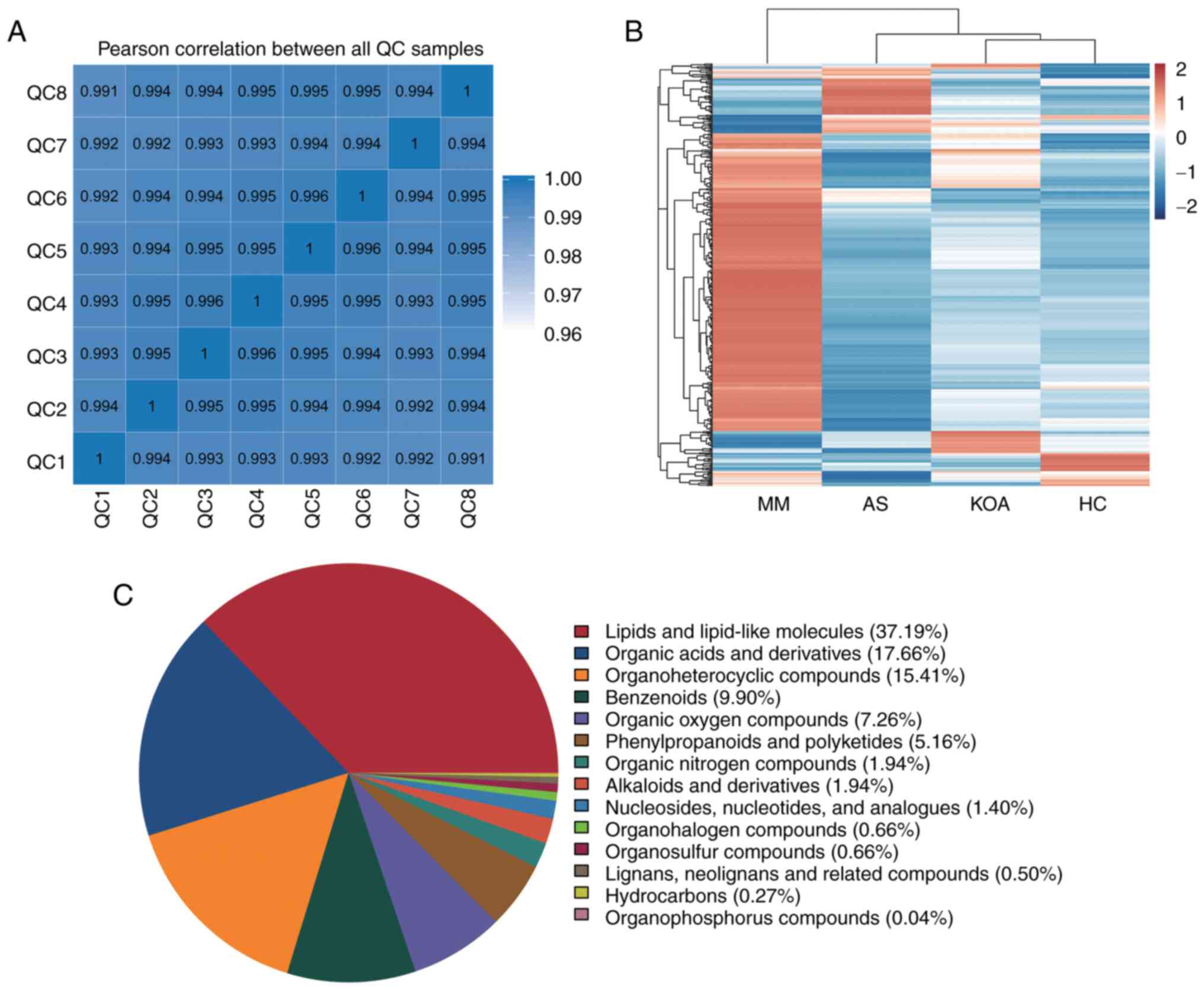

Pearson correlation coefficients were first

calculated between the QC samples based on the relative

quantitative values of the metabolites and it was observed that the

correlation coefficients (r-values) of the different QC samples

were all >0.99, which indicated that the instrument was well

stabilized throughout the entire sample testing period (Fig. 1A). The raw data from the downstream

machine were preprocessed using XCMS software and metabolites with

a CV of <30% in the QC samples were retained, resulting in a

total of 2,595 identified metabolites. The top five metabolite

classes were: Lipid and lipid-like molecules, organic acids and

their derivatives, organic heterocyclic compounds, benzenes and

organic oxygenated compounds (Fig.

1C).

Intergroup cluster analysis of all

differential metabolites

In order to visualize the overall changes in serum

metabolism, hierarchical clustering analysis (38) of all differential metabolites

between the groups was performed. The results showed that the

metabolic profiles of the KOA group were the most similar to those

of the HC group, followed by the AS group and lastly the MM group.

This is consistent with the results of the present analysis of

clinical indicators, the metabolic abnormalities were more

significant in the AS group compared with those in the KOA group

(Fig. 1B).

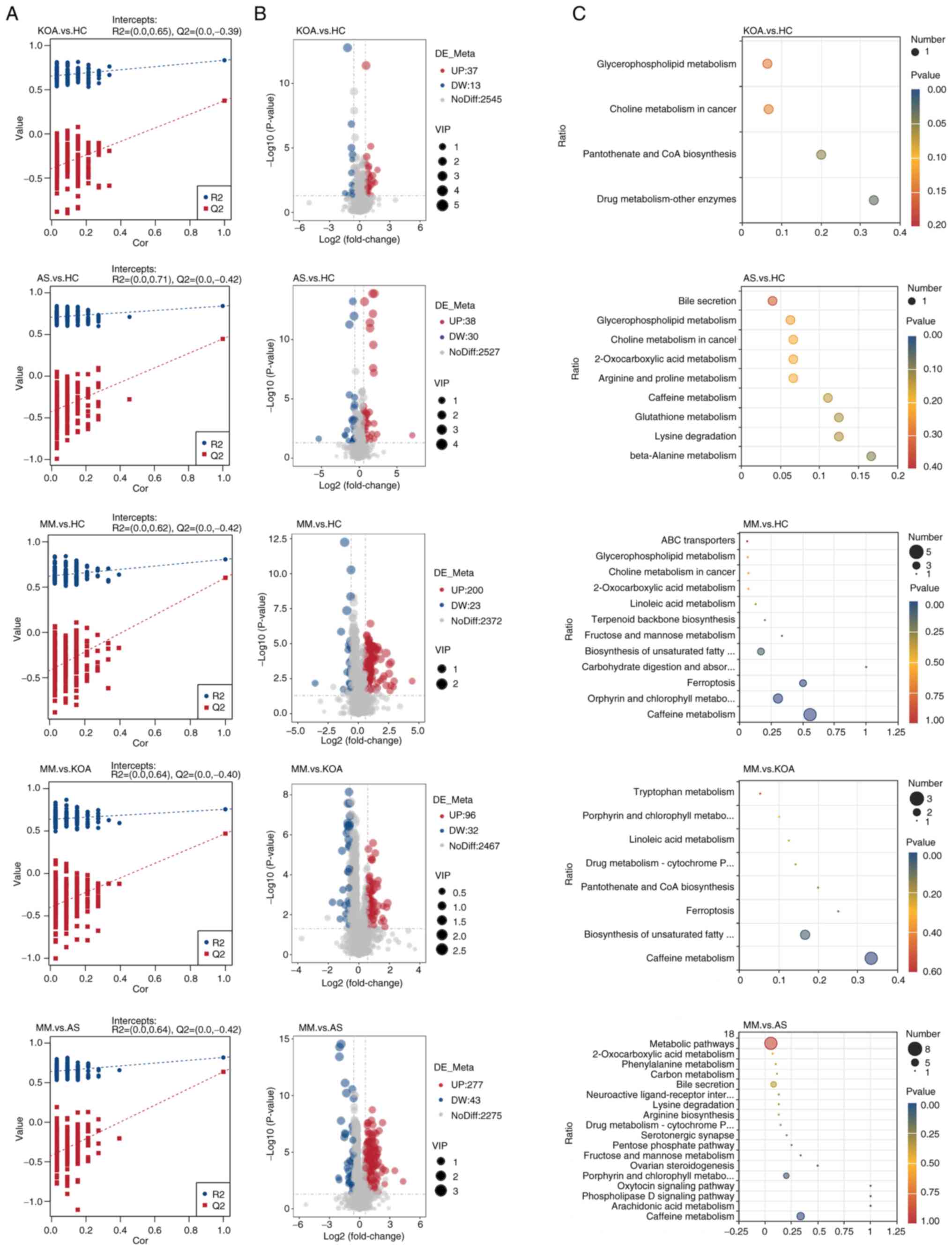

Differential metabolite analysis

The current study next performed differential

metabolite identification. To ensure the reliability of the

results, a supervised PLS-DA model was first developed for an

improved account for metabolite variation between each comparison

group. The PLS-DA model was validated using a permutation test with

200 random numbers. The results showed that all red predictability

(Q2) values on the left side were lower than the original points on

the right side, R2 and Q2 were close to 1, R2 data were larger than

Q2 data and the Q2 regression line had an intercept with the y-axis

of <0. This demonstrated that the PLS-DA model was valid and

stable (Fig. 2A). Next, volcano

plots were constructed for the identification of differential

metabolites among each of the five comparison groups and the

screening conditions for the identification of differential

metabolites were VIP>1, P<0.05 and FC≥2 or FC≤0.5 (Fig. 2B). After obtaining the

identification results of differential metabolites among the

comparison groups, to determine their functions, KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis was performed using the differential

metabolites identified in each of the five comparison groups

(Fig. 2C). The results showed that

the top five pathways in the AS group vs. the HC group comparison

were: β-alanine metabolism, lysine degradation, glutathione

metabolism, caffeine metabolism and arginine and proline

metabolism, all of which were non-significant. In the KOA group vs.

the HC group comparison, drug metabolism-other enzymes and

pantothenic acid and CoA biosynthesis pathways were markedly

enriched. A total of four pathways, caffeine metabolism, porphyrin

and chlorophyll metabolism, iron oxidation and carbohydrate

digestion and absorption were markedly enriched in the comparison

between the MM group and the HC group. The four pathways markedly

enriched in the comparison between the MM group and the AS group

were caffeine metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism,

phospholipase D signaling pathway and oxytocin signaling pathway.

The caffeine metabolism pathway was markedly enriched in the

comparison between the MM group and the KOA group.

From the results of the KEGG analysis, it was

observed that significant enrichment in caffeine metabolism

pathways was observed in the comparison of the MM group with the

other three groups (Fig. 2C),

suggesting that abnormal caffeine metabolism may influence or

promote the development of KOA-AS multimorbidity. The present study

further analyzed the caffeine metabolic pathway by comparing its

five related metabolites (caffeine, theophylline, 1-methyluric

acid, 1-methylxanthine and 1,7-dimethyluric acid) among the HC,

KOA, AS and MM groups, to observe the differences between the

groups and the overall trend.

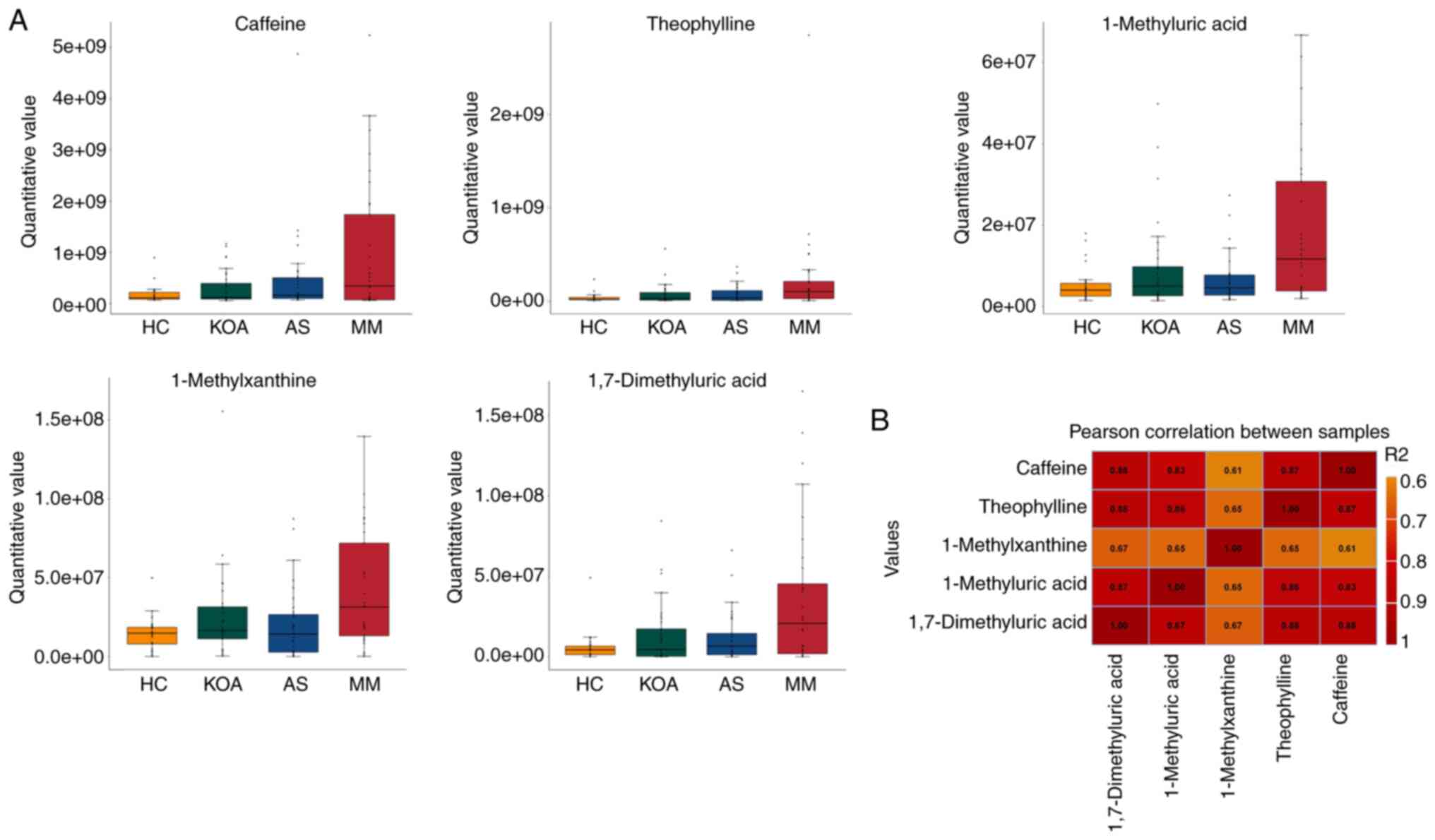

From the results presented in Table SIV and in the box plots (Fig. 3A), it was indicated that the

relative serum levels of the five caffeine metabolism-related

metabolites (caffeine, theophylline, 1-methyluric acid,

1-methylxanthine and 1,7-dimethyluric acid) increased progressively

with the number of individuals suffering from the disease (healthy

control < suffering from mono-disease < suffering from

co-disease). It may be suggested that the higher the relative serum

levels of caffeine and its secondary metabolites, the higher the

risk of developing KOA-AS multimorbidity.

To understand the association between the relative

serum levels of these five metabolites, the Pearson correlation

coefficients between the relative quantitative values of five

metabolites were calculated (Fig.

3B) and it was observed that the correlation coefficients of

all five metabolites (r-values) were all >0.6, suggesting that

the relative levels of these five metabolites were moderately or

highly positively associated with each other.

Transcriptomics analysis data

sources

To further investigate the possible effects of

metabolic abnormalities and caffeine on patients with KOA-AS

multimorbidity, common DEGs in patients with KOA and patients with

AS were assessed using publicly available transcriptomics data to

screen hub genes for KOA-AS multimorbidity.

According to the previously established criteria,

the GSE48556 dataset for OA (139 samples, 33 controls and 106

patients with OA; mean age, ~ 60 years; the case group suffered

from OA in at least two or more sites) and the GSE23746 dataset for

AS (95 samples, 19 controls and 76 patients with AS; the case group

comprised patients with carotid AS) were obtained. The experimental

platform for both datasets was gene expression microarray

technology, the specimen types were human peripheral blood

mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and the sample sizes were relatively

large, which were able to satisfy the analysis needs.

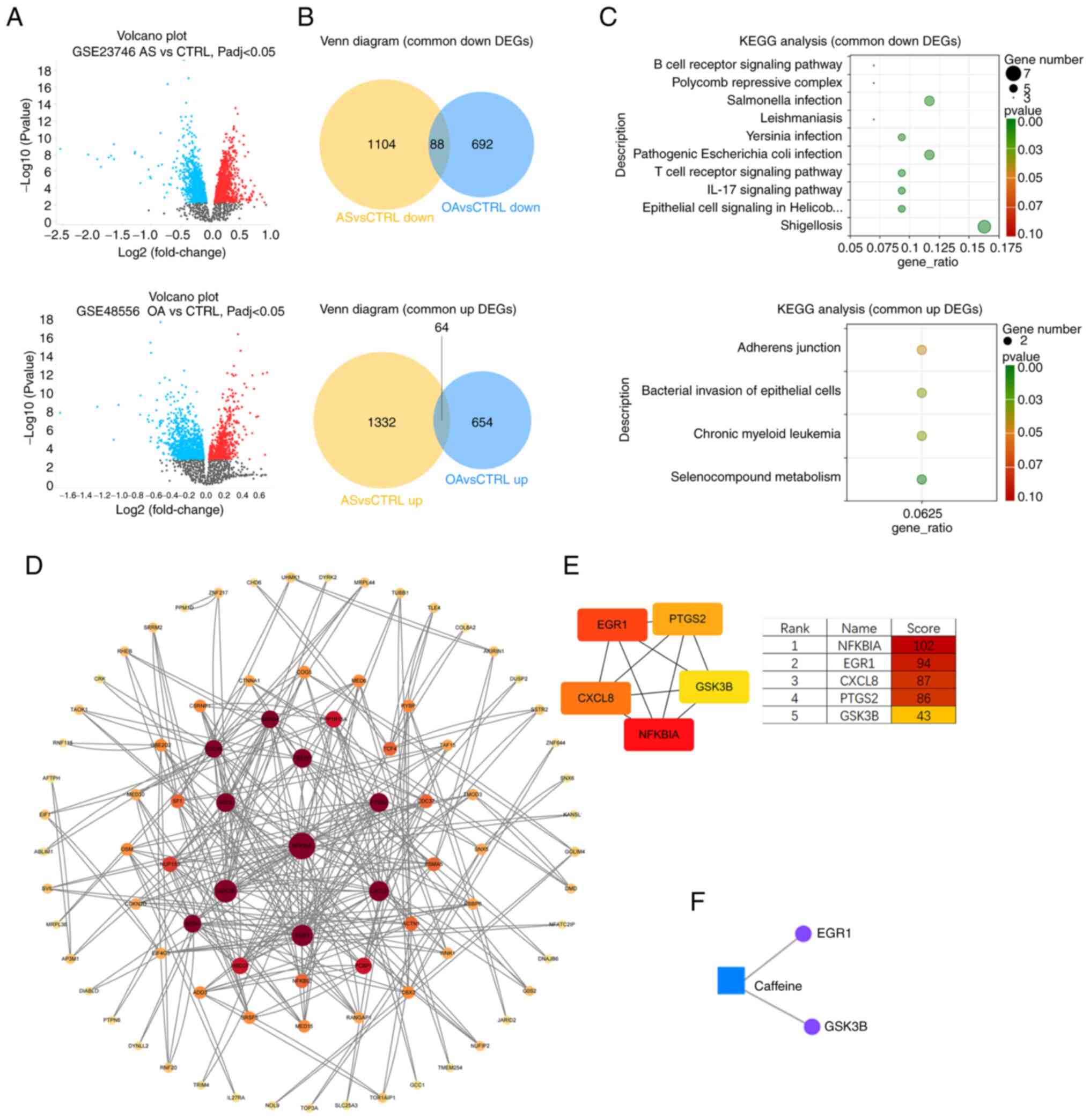

Screening of common DEGs

Using GEO2R, an online analysis platform for the GEO

database, 2,082 DEGs (including 814 upregulated genes and 1,268

downregulated genes) were obtained from the GSE48556 OA dataset

(Fig. 4A) and 2,932 DEGs

(including 1,590 upregulated genes and 1,342 downregulated genes)

were obtained from the GSE23746 AS dataset. The Venn diagram

intersections showed 64 shared upregulated DEGs and 88 shared

downregulated DEGs (Fig. 4B).

KEGG analysis of OA and AS common

DEGs

To understand the function of DEGs shared by OA and

AS, KEGG functional enrichment analysis was performed on the 64

upregulated DEGs and 88 downregulated DEGs (Fig. 4C). The results showed that

upregulated DEGs were enriched in the metabolism of selenium

compounds, chronic myeloid leukemia, bacterial invasion of

epithelial cells and adhesion junction processes. Downregulated

DEGs were mainly enriched in shigellosis, epithelial cell signaling

in Helicobacter pylori infection, IL-17 signaling pathway,

T-cell receptor signaling pathway and pathogenic E. coli

infection processes.

The enrichment results showed that the common

transcriptional features of PBMCs in patients with OA and patients

with AS were the disruption (activation or inhibition) of

infectious disease-related processes and the suppression of immune

system-related pathways.

PPI analysis for screening hub

genes

To understand the interrelationships between the

DEGs corresponding to the encoded proteins, all 152 DEGs (64 up-

and 88 downregulated) were uploaded to the STRING database to

construct the PPI network (Fig.

4D). The PPI network contains a total of 85 nodes and 145

edges. In order to screen the hub genes, the PPI network was

imported into Cytoscape software and the cytoHubba plug-in was used

to assign values to each protein according to the topological

network algorithm. The top five scored genes in the Maximal Clique

Centrality mode were analyzed, which were NFKBIA, EGR1, CXCL8,

PTGS2 and GSK3B (Fig.

4E).

Metabolite-gene network analysis

The ‘Network Analysis’ function in Metaboanalyst 6.0

(metaboanalyst.ca/), an online metabolomics analysis platform, was

applied to perform Gene-Metabolite Interaction Network Analysis on

five caffeine-related metabolites (caffeine, theophylline,

1-methyluric acid, 1-methylxanthine and 1,7-dimethyluric acid) and

the top five scoring hub genes (NFKBIA, EGR1, CXCL8, PTGS2

and GSK3B). Caffeine was found to interact with EGR1

and GSK3B (Fig. 4F).

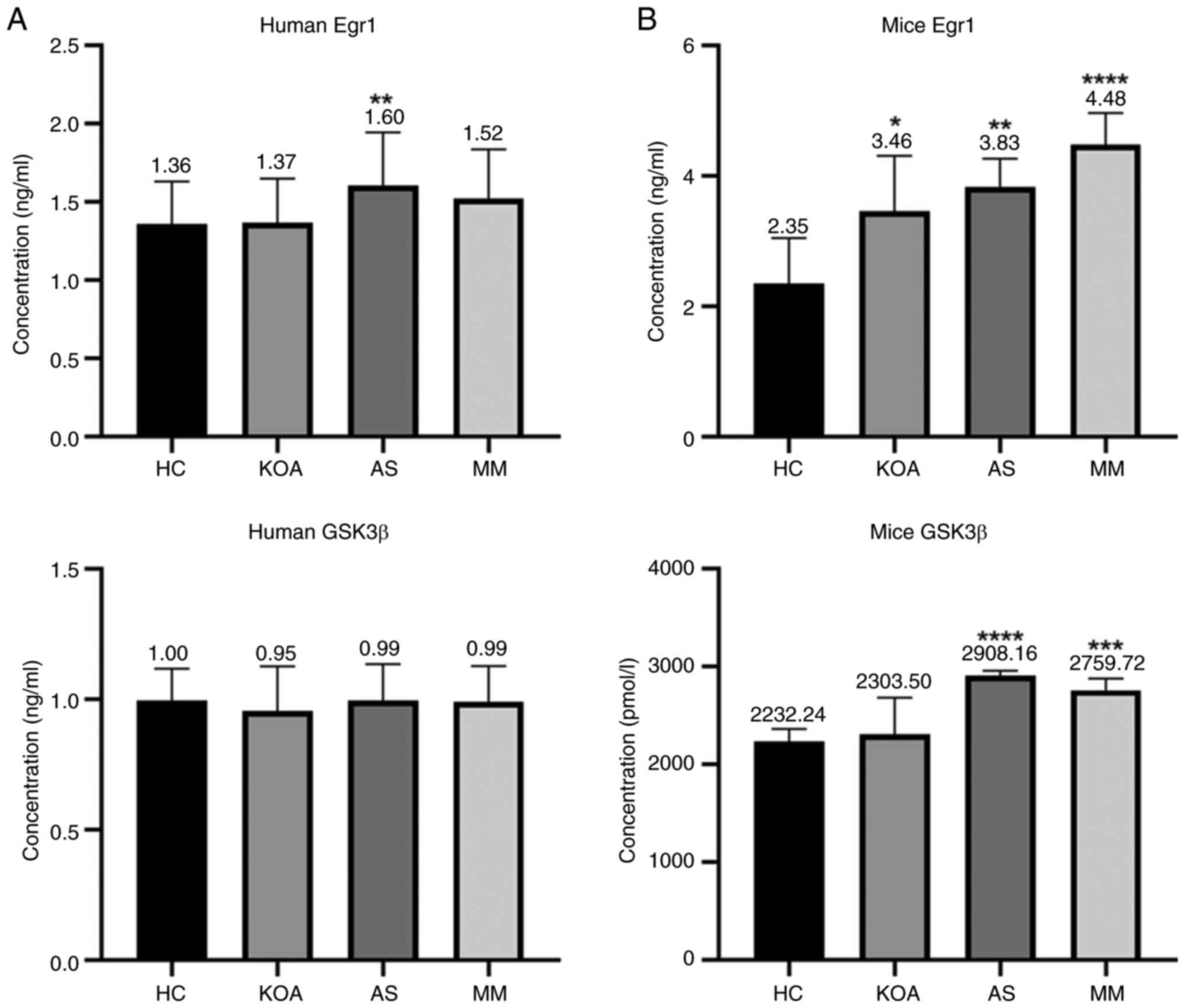

Validation of clinical samples

To verify the effect of caffeine on EGR1 and

GSK3B genes, the same batch of serum samples used for the

metabolomics assay were used and the ELISA method was applied to

measure the concentrations of Egr1 and GSK3β proteins in the serum

of the aforementioned groups. The standard curves were plotted

using CurveExpert 1.4 and the OD450 values were converted to

standard units of ng/ml. The correlation coefficients of the

standard curves of each batch were r>0.999 and the results were

reliable. The bar graph (Fig. 5A)

showed that the human serum GSK3β protein concentrations did not

differ between groups; whereas the human serum Egr1 protein

concentration exhibited an association with AS. Serum Egr1 protein

concentration was markedly higher in the AS compared with that in

the HC group.

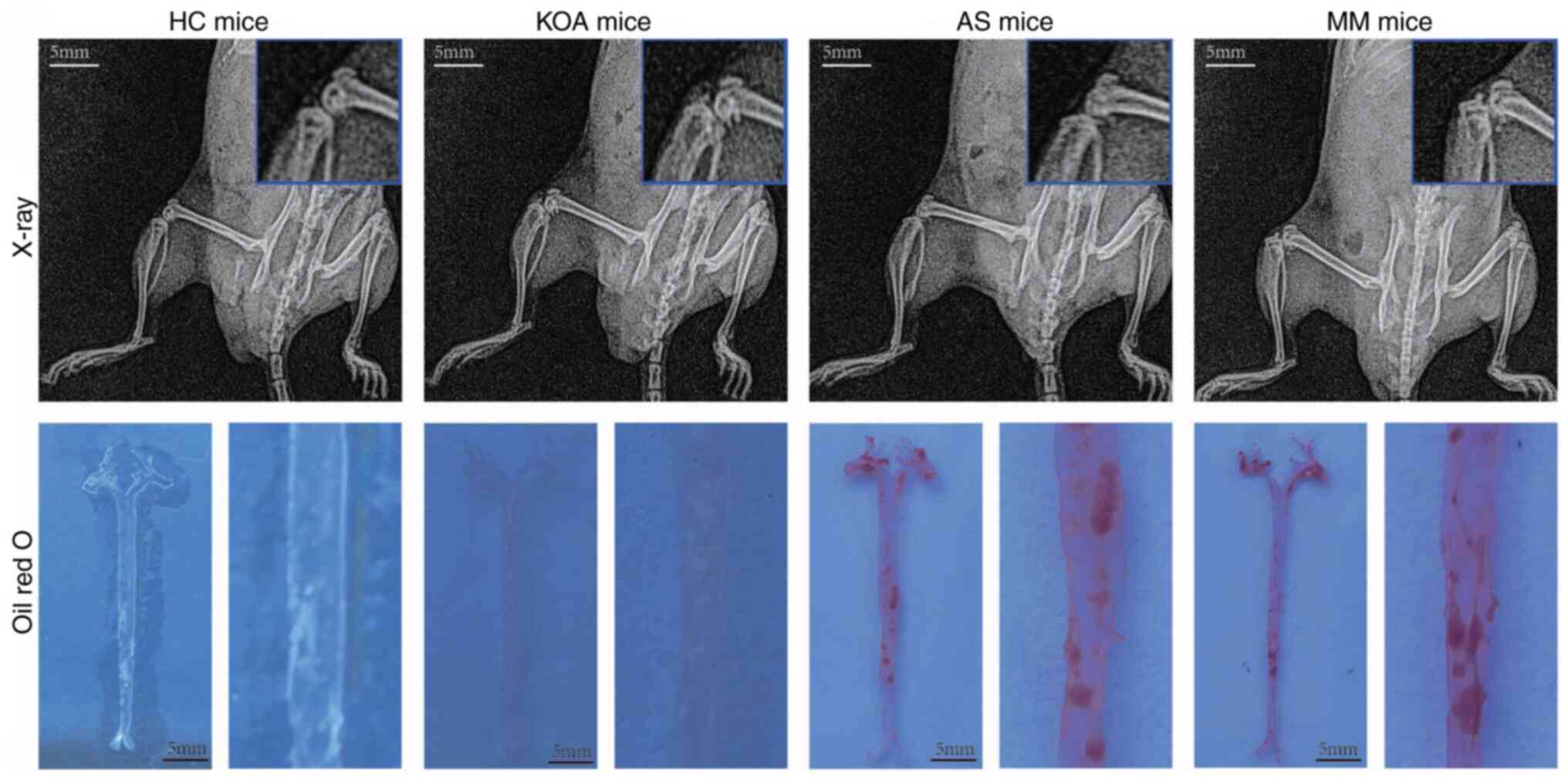

Validation of disease modeling

effects

To validate the hub genes for KOA-AS multimorbidity,

a disease model generated in mice corresponding to the clinical

study groups was used. After the experimental animals were randomly

grouped, they were pre-housed for 1 week and were fed normal chow

to acclimate them to the environment before modeling. A total of 1

week after the mice were acclimated to the environment, the mice in

the AS and MM groups were fed high-fat chow, whereas the KOA model

was surgically constructed by applying the modified Hulth method to

the mice in the KOA and MM groups from week 3.

The modeling effect of the mice in each group was

verified after 12 weeks of high-fat chow feeding and the materials

(Aorta, cartilage, blood) were taken at the same time (Fig. 6). X-ray examination showed that the

knee joints of mice in the KOA and MM groups had obvious

osteoclasts, whereas the knee joints of mice in the other two

groups were smooth and free of osteoclasts. The results of Oil Red

O staining showed that lipid plaques had formed in the aorta of

mice in the AS and MM groups, whereas no lipid plaques were

observed in the other two groups. Based on these results, it was

determined that the animal disease models were successfully

constructed.

Differential expression of the hub

genes in the serum of animal disease models

The concentrations of two proteins, Egr1 and GSK3β,

in the serum of each group of mice were determined by ELISA. The

standard curve was plotted using CurveExpert 1.4 and the OD450

values were converted to ng/ml or pmol/l. The standard curves for

each batch showed correlation coefficients r>0.999, confirming

reliability (Fig. 5B).

The serum Egr1 protein concentration of mice was

associated with both KOA and AS and there were significant

differences in the levels in the KOA, AS and MM group compared with

those in the HC group. In addition, there was a rising trend with

the increase in the number of diseased mice (healthy control <

suffering from a single disease < suffering from a co-morbid

disease). The results were in agreement with the metabolite-gene

network analysis, thus indicating that EGR1 may be the key

gene for KOA-AS multimorbidity.

Serum GSK3β protein concentration in mice was

associated with AS only, with significant differences in the AS and

the MM group compared with the HC group.

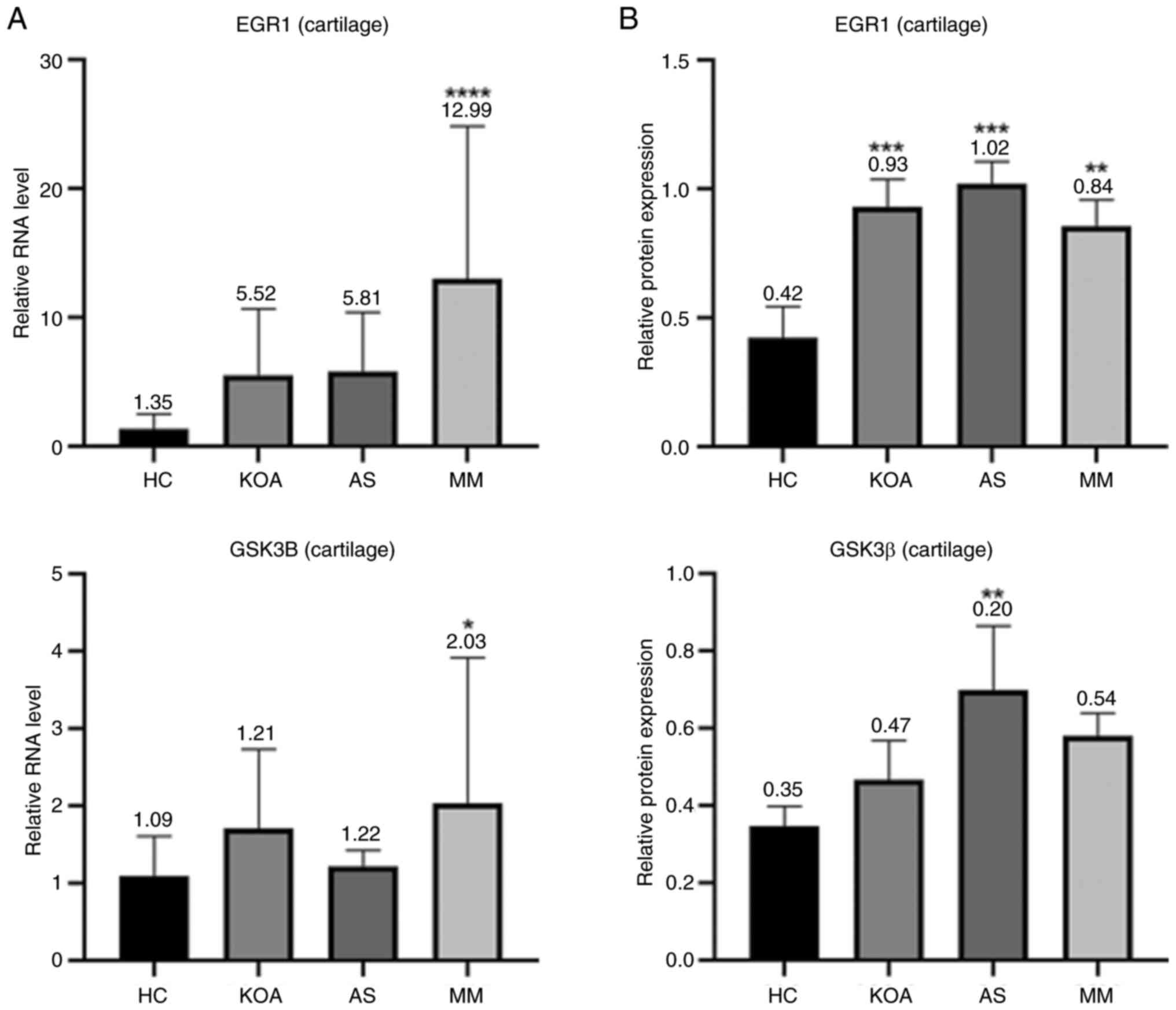

Differential expression of hub genes

in the cartilage tissues of animal disease models

The bar graphs (Fig.

7) showed that in mouse articular cartilage tissues, the RNA

transcript levels of EGR1 and the protein expression levels

of Egr1 were markedly higher in the KOA, AS and MM group than those

in the HC group, which was in line with the results shown in the

mouse serum samples. The results regarding GSK3β did not show a

uniform pattern and the expression levels of GSK3β in mouse

cartilage tissues only showed an association with AS, which was

consistent with the results in the mouse serum; however, the RNA

transcript levels of GSK3B in cartilage tissues were only

associated with KOA. In conclusion, Egr1 exhibited a high

association with KOA-AS multimorbidity in mouse serum, which was

further verified in the assessment of mouse cartilage tissues and

its corresponding gene EGR1 is expected to be a common

therapeutic target for KOA and AS.

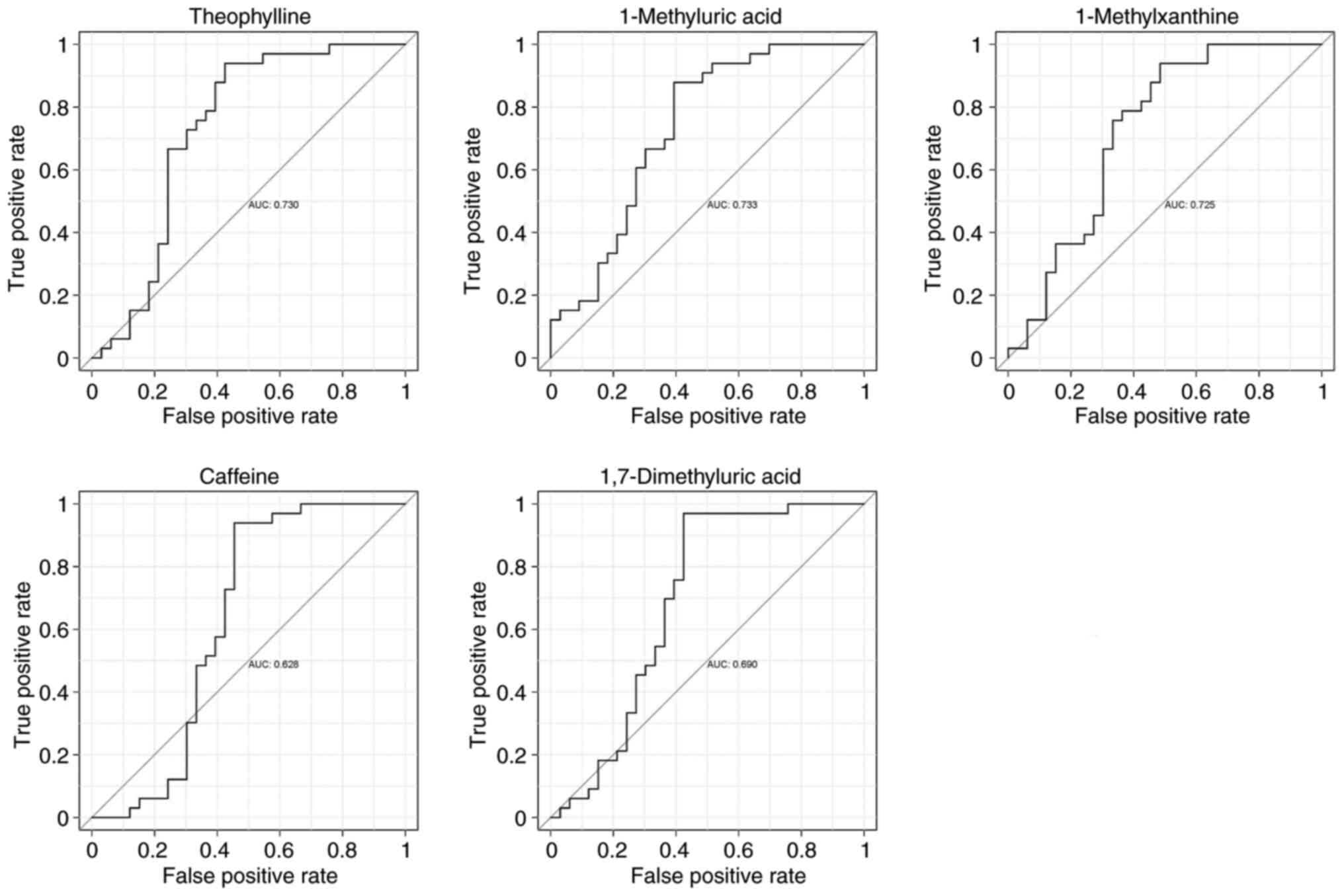

ROC curve analysis of metabolites

To assess the diagnostic value of caffeine and its

secondary metabolites (theophylline, 1-methyluric acid,

1-methylxanthine and 1,7-dimethyluric acid), a subject workup

characterization (ROC curve analysis) was performed using relative

quantitative values of metabolites from metabolomics analysis in

the HC and MM groups (Fig. 8),

which showed that theophylline, 1-methyluric acid and

1-methylxanthine had a better potential to become diagnostic

markers (AUC >0.7), whereas caffeine and 1,7-dimethyluric acid

had a relatively average performance (AUC >0.6).

Predicting KOA-AS multimorbidity

drugs

EGR1 was imported into the DGidb database for

drug prediction and a total of two small-molecule targeted drugs

(GENIPIN, BRIVOLIGIDE) were exported; the DGidb database online

scoring software was used to calculate the interaction scores of

the drugs with the genes (Table

II). The results revealed that the interaction scores of these

two drugs were high and both of them were not approved for the

market, thus indicating that EGR1 may be a potential future

drug target.

| Table II.DGidb Database output. |

Table II.

DGidb Database output.

| Gene | Drug | Regulatory

approval | Interaction

Score |

|---|

| EGR1 | GENIPIN | Not approved | 52.203799 |

| EGR1 | BRIVOLIGIDE | Not approved | 26.101899 |

Discussion

From the point of view of metabolic abnormalities,

in the present study population, obesity (BMI), blood glucose, a

previous history of hypertension and a previous history of diabetes

mellitus were associated with both KOA and AS, whereas systolic

blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and triglycerides were

mainly associated with AS. These findings suggested that metabolic

abnormalities may be more pronounced in those with AS than those

with KOA in a population with a mean age of 40 years. Consistent

results were also obtained in the intergroup clustering heat map

analysis of serum metabolomics, where the serum metabolic profile

of the KOA group was closer to that of the HC group among the two

mono-disease groups, whereas that of the AS group was closer to

that of the MM group, suggesting that metabolic abnormalities have

a greater effect on AS. In addition, the results of the analysis of

blood pressure (associated only with AS) and previous history of

hypertension (associated with both KOA and AS) were not consistent

in the same population, presumably influenced by the control of

antihypertensive medication.

The present results suggested that OA and AS are

interrelated through the metabolic syndrome, with various

components of the metabolic syndrome (obesity, diabetes mellitus,

dyslipidemia and hypertension) associated with OA (39) and it has been suggested that OA is

a phenotype of the metabolic syndrome (40). In addition, metabolic syndrome is a

risk factor for CVDs, which involves a variety of pathologies such

as dyslipidemia, elevated blood glucose and elevated blood

pressure, all of which increase the risk of AS (41).

The mean age of the present study population was

low, which may explain the lack of abnormalities in metabolic

pathways associated with metabolic syndrome in the results of

metabolomics analysis. On the other hand, however, conducting the

present study in a relatively young population may help to

understand the earliest onset state of the disease. Although not

markedly enriched for abnormalities in pathways associated with

metabolic syndrome, caffeine metabolism was observed to be markedly

enriched in all three comparison groups based on the results of

KEGG enrichment analysis, suggesting that abnormalities in caffeine

metabolism may be associated with KOA-AS multimorbidity. In the

single-indicator analysis for caffeine and its secondary

metabolites (theophylline, 1-methyluric acid, 1-methylxanthine and

1,7-dimethyluric acid), a consistent trend was observed in which

the levels of these metabolites were markedly increased with the

number of diseased individuals in the study population. The higher

the relative serum levels of caffeine and its secondary metabolites

in the current study population, the higher the risk of developing

KOA-AS multimorbidity and it could be hypothesized that caffeine

metabolism capacity varies between individuals and that caffeine

metabolism disorders may exist. It is hypothesized that caffeine

metabolism impairment results in progressive serum caffeine

accumulation. Consequently, elevated caffeine levels drive

inflammatory disease pathogenesis through EGR1 gene

dysregulation and the induction of a pro-inflammatory milieu.

Previous studies have reported that the CYP1A2 gene rs762551

polymorphism is associated with individual caffeine metabolism

capacity (42,43). Individuals with the AA genotype

have been identified as ‘slow metabolizers’ of caffeine, exhibiting

markedly lower caffeine clearance rates compared with AC/CC

genotype ‘fast metabolizers’ (42,43).

The inferred ‘caffeine metabolism disorder’ in our study may be

related to this SNP, indicating that differences in serum caffeine

levels are influenced by both lifestyle habits and genetic factors.

The current study did not include genotyping of this SNP locus nor

collected data on caffeine intake. This will be a key direction for

future research.

Previous studies on the relationship between

caffeine and health are controversial; a previous study suggesting

that caffeine intake is protective against CVDs and that long-term

caffeine intake develops tolerance (44), whereas others have demonstrated

that caffeine intake raises adrenaline levels and blood pressure in

the short term (45), which may

have an acute detrimental effect on aortic stiffness in patients

with hypertension (46). This

suggests that elevated blood pressure may be the earliest in the

spectrum of metabolic abnormalities associated with KOA-AS

multimorbidity.

Bioinformatics analysis using public transcriptomics

datasets showed that the common feature of OA and AS in the high

age group (mean age >60 years) was inflammation, which is

consistent with the expectation of the present study, as evidenced

by the disruption of infectious disease-related pathways and the

suppression of some immune system signaling pathways. The five key

genes screened in the current study (NFKBIA, EGR1, CXCL8,

PTGS2 and GSK3B) are also involved in inflammatory

responses to varying degrees. Combining the present findings with

those of previous studies, it may be extrapolated that the

inflammatory state in the late stage of the disease in patients

with KOA-AS multimorbidity is caused by numerous metabolic

abnormalities in the early stage.

In the metabolite-gene interaction network analysis,

it was revealed that EGR1 and GSK3B interacted with

caffeine and through further review of the literature, it was

demonstrated that caffeine may have inconsistent effects on

EGR1 and GSK3B under different circumstances.

Previous studies suggested that caffeine activates GSK3β by

inhibiting its phosphorylation (47,48);

as for EGR1, some studies have shown that EGR1

expression is downregulated in hepatocytes after treatment with a

certain concentration of caffeine (49); and that caffeine upregulates SIRT3

expression by inhibiting the EGR1 signaling pathway in

astrocytes of the central nervous system in mice (50). Others have shown that caffeine has

a promoting effect on EGR1 expression, such as in mice

treated with caffeine combined with cocaine, where the prefrontal

cortex EGR1 expression was shown to be upregulated (51). This suggests that caffeine has

varying effects on EGR1 in different tissues or

physiological states.

Based on the findings that EGR1/Egr1 was

markedly upregulated in both serum and cartilage tissues

(RNA/protein levels) in the KOA, AS and MM groups in advanced

disease models, whereas in the serum of clinically mildly ill

patients, Egr1 was elevated only in the AS group, its reliability

may be suggested as a KOA-AS multimorbid hub gene with

transformation into a generalized marker in advanced stages. By

contrast, the regulation of GSK3β showed complexity; its protein

levels (serum and cartilage) were elevated in the AS and MM groups,

whereas its RNA levels in cartilage were associated with KOA,

suggesting post-transcriptional regulation or functional

differentiation. Notably, disease stage markedly affected the

results, with widespread abnormalities of Egr1/GSK3β in late models

(compared with early clinical samples) supporting the inference

that late inflammation is triggered by early metabolic

abnormalities. In addition, diseased mice without caffeine intake

still exhibited elevated serum Egr1 and GSK3β, suggesting that

their levels are regulated by factors other than caffeine.

In previous studies, EGR1 has been reported

as a possible hub gene of KOA (52) and AS (53). To the best of the authors'

knowledge, the present study is the first to propose the key role

of EGR1 in KOA-AS multimorbidity and to construct an

innovative disease model of KOA-AS multimorbidity. Notably, the

results of the metabolite-gene network analysis were verified by

mice experiments. EGR1 has also been reported to be

associated with metabolic disorders such as metabolic dysfunctions,

insulin resistance and others (54,55),

which supports the association between metabolic abnormalities and

EGR1. As a transcriptional regulator, EGR1 plays a

key role in the regulation of macrophage inflammatory response and

it may be hypothesized that metabolic abnormalities could promote

inflammation by regulating the expression of EGR1.

In the clinical application analysis, the present

study identified three caffeine secondary metabolites

(theophylline, 1-methyluric acid and 1-methylxanthine) as having

potential to become diagnostic biomarkers and EGR1 was

considered a drug target with some value. Although GENIPIN (a drug

predicted by EGR1), has not been approved for marketing,

experimental studies have suggested that hydrogels linked by

GENIPIN can reduce joint wear and tear in patients with OA

(56) and GENIPIN can be used to

make scaffolds for cardiovascular use (57). In addition, it has been suggested

that GENIPIN may ameliorate the effects of hyperlipidemia and lipid

accumulation in the liver (58).

These findings also corroborate the reliability of the predicted

results.

In conclusion, the present study not only verified

previous studies on KOA-AS multimorbidity, but also explored the

association between KOA and AS and the possible formation

mechanisms of KOA-AS multimorbidity from numerous perspectives.

Abnormal caffeine metabolism was revealed to be an early risk

factor for KOA-AS multimorbidity and potential hub genes for KOA-AS

multimorbidity were identified. Preliminary predictions on the

clinical value of these key molecules for KOA-AS multimorbidity

were conducted, which are expected to provide new directions for

diagnostic and therapeutic studies of KOA-AS multimorbidity.

Finally, the present study has the following shortcomings: i) The

available information could not determine the reasons for the

differences in serum caffeine levels between the groups and

caffeine intake needs to be assessed to confirm this; ii) the

current findings do not clarify the specific effects of caffeine

and the location of its effects on KOA-AS multimorbidity and

interventional experiments need to be performed to further

demonstrate this; and iii) predictions about the value of clinical

applications need to be verified by further experiments.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Key Research and

Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFC3604900); National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82172410); Capital

Foundation of Medical Development and Research (grant nos.

2024-2G-6043 and 2024-4-6045).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QK, KZ and PY conceived the study and designed the

methodology. QK, PX and WX performed experiments. ZG, QK and LD

analyzed data. QK wrote the original draft. KZ, PY and ZG reviewed

and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript. QK and KZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the clinical part

of the study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of

Shougang Hospital of Peking University (approval no.

IRBK-2024-012-01, approval date March 27, 2024); the animal

experiments was approved by the Ethics Committee for Experimental

Animals of Beijing JinglaiHuake Biotechnology Co (approval no.

JLHK-20241110-02, approved date November 13, 2024). All clinical

cases recruited for this study have signed an informed consent

form; data collected from previous studies or samples from biobanks

used in this study have been exempted from informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Dr Zhang Keshi ORCID: 0000-0003-3547-1964. Dr

Zhenpeng Guan ORCID: 0000-0002-4487-7918.

References

|

1

|

Wang XQ and Chen PJ: Population ageing

challenges health care in China. Lancet. 383:8702014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G,

Wyke S and Guthrie B: Epidemiology of multimorbidity and

implications for health care, research and medical education: A

cross-sectional study. Lancet. 380:37–43. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R,

Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, Meinow B and Fratiglioni L: Aging

with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing

Res Rev. 10:430–439. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sav A, Kendall E, McMillan SS, Kelly F,

Whitty JA, King MA and Wheeler AJ: ‘You say treatment, I say hard

work’: Treatment burden among people with chronic illness and their

carers in Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 21:665–674.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Banjare P and Pradhan J: Socio-economic

inequalities in the prevalence of multi-morbidity among the rural

elderly in Bargarh District of Odisha (India). PLoS One.

9:e978322014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo

RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder

GG, et al: Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected

musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum.

41:778–799. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold

LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG,

et al: Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic

conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum.

58:26–35. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang SY, Olson-Kellogg B, Shamliyan TA,

Choi JY, Ramakrishnan R and Kane RL: Physical therapy interventions

for knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Ann

Intern Med. 157:632–644. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F and Lafeber FP:

Osteoarthritis: An update with relevance for clinical practice.

Lancet. 377:2115–2126. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

He Y, Jiang W and Wang W: Global burden of

osteoarthritis in adults aged 30 to 44 years, 1990 to 2019: Results

from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Musculoskelet

Disord. 25:3032024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wu H, Yao R, Wu J, Wen G and Wang Y: Does

kinesio taping plus exercise improve pain and function in patients

with knee osteoarthritis?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. Front Physiol. 13:9612642022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, Thevenot

O, Fransen M, Wells GA, Imoto AM, Toupin-April K, Westby M,

Gallardo ICÁ, et al: The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines

for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part one: Introduction

and mind-body exercise programs. Clin Rehabil. 31:582–595. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bauersachs R, Zeymer U, Brière JB, Marre

C, Bowrin K and Huelsebeck M: Burden of coronary artery disease and

peripheral artery disease: A literature review. Cardiovasc Ther.

2019:82950542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW,

Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling

FN, Deo R, et al: Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2018 Update:

A report from the american heart association. Circulation.

137:e67–e492. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Conaghan PG, Vanharanta H and Dieppe PA:

Is progressive osteoarthritis an atheromatous vascular disease? Ann

Rheum Dis. 64:1539–1541. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mathieu S, Couderc M, Tournadre A and

Soubrier M: Cardiovascular profile in osteoarthritis: A

meta-analysis of cardiovascular events and risk factors. Joint Bone

Spine. 86:679–684. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hall AJ, Stubbs B, Mamas MA, Myint PK and

Smith TO: Association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular

disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol.

23:938–946. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang H, Bai J, He B, Hu X and Liu D:

Osteoarthritis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: A

meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 6:396722016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Veronese N, Cereda E, Maggi S, Luchini C,

Solmi M, Smith T, Denkinger M, Hurley M, Thompson T, Manzato E, et

al: Osteoarthritis and mortality: A prospective cohort study and

systematic review with meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum.

46:160–167. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kadam UT, Holmberg A, Blagojevic M,

Nilsson PM and Akesson K: Risk factors for cardiovascular disease

and future osteoarthritis-related arthroplasty: A population-based

cohort study in men and women from Malmö, Sweden. Scand J

Rheumatol. 40:478–485. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hoeven TA, Kavousi M, Ikram MA, van Meurs

JB, Bindels PJ, Hofman A, Franco OH and Bierma-Zeinstra SM: Markers

of atherosclerosis in relation to presence and progression of knee

osteoarthritis: A Population-based cohort study. Rheumatology

(Oxford). 54:1692–1698. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hoeven TA, Kavousi M, Clockaerts S,

Kerkhof HJ, van Meurs JB, Franco O, Hofman A, Bindels P, Witteman J

and Bierma-Zeinstra S: Association of atherosclerosis with presence

and progression of osteoarthritis: The Rotterdam Study. Ann Rheum

Dis. 72:646–651. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang Y, Novera D, Wluka AE, Fairley J,

Giles GG, O'Sullivan R and Cicuttini FM: Association between

popliteal artery wall thickness and knee structure in adults

without clinical disease of the knee: A prospective cohort study.

Arthritis Rheumatol. 67:414–422. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jonsson H, Fisher DE, Eiriksdottir G,

Aspelund T, Klein R, Gudnason V and Cotch MF: Hand and knee

osteoarthritis are associated with reduced diameters in retinal

vessels: The AGES-Reykjavik study. Rheumatol Int. 39:669–677. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li W, Guo H, Wang C, Zhang Y and Wang J:

Autologous micro-fragmented adipose tissue in the treatment of

atherosclerosis patients with knee osteoarthritis in geriatric

population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One.

18:e02896102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G,

Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg

M, et al: Development of criteria for the classification and

reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of

the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the

American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 29:1039–1049.

1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chambers MC, Maclean B, Burke R, Amodei D,

Ruderman DL, Neumann S, Gatto L, Fischer B, Pratt B, Egertson J, et

al: A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics.

Nature Biotechnol. 30:918–920. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Smith CA, Want EJ, O'Maille G, Abagyan R

and Siuzdak G: XCMS: Processing mass spectrometry data for

metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching and

identification. Anal Chem. 78:779–787. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Dai W, Xie D, Lu M, Li P, Lv H, Yang C,

Peng Q, Zhu Y, Guo L, Zhang Y, et al: Characterization of white tea

metabolome: Comparison against green and black tea by a nontargeted

metabolomics approach. Food Res Int. 96:40–45. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wen B, Mei Z, Zeng C and Liu S: metaX: A

flexible and comprehensive software for processing metabolomics

data. BMC Bioinformatics. 18:1832017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ghosh D: Incorporating the empirical null

hypothesis into the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Stat Appl Genet

Mol Biol. 112012.doi: 10.1515/1544-6115.1735. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT and

Lin CY: cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from

complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 8 (Suppl 4):S112014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Pang Z, Lu Y, Zhou G, Hui F, Xu L, Viau C,

Spigelman AF, MacDonald PE, Wishart DS, Li S and Xia J:

MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data

processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res.

52:W398–W406. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ji X, Du W, Che W, Wang L and Zhao L:

Apigenin inhibits the progression of osteoarthritis by mediating

macrophage polarization. Molecules. 28:29152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cannon M, Stevenson J, Stahl K, Basu R,

Coffman A, Kiwala S, McMichael JF, Kuzma K, Morrissey D, Cotto K,

et al: DGIdb 5.0: Rebuilding the drug-gene interaction database for

precision medicine and drug discovery platforms. Nucleic Acids Res.

52:D1227–D1235. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen X, Xie C, Sun L, Ding J and Cai H:

Longitudinal metabolomics profiling of Parkinson's Disease-Related

α-Synuclein A53T transgenic mice. PLoS One. 10:e01366122015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sampath SJP, Venkatesan V, Ghosh S and

Kotikalapudi N: Obesity, metabolic syndrome and Osteoarthritis-an

updated review. Curr Obes Reps. 12:308–331. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Katz JD, Agrawal S and Velasquez M:

Getting to the heart of the matter: Osteoarthritis takes its place

as part of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 22:512–519.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Grundy SM: Metabolic syndrome update.

Trends Cardiovasc Med. 26:364–373. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Robertson TM, Clifford MN, Penson S,

Williams P and Robertson MD: Postprandial glycaemic and lipaemic

responses to chronic coffee consumption may be modulated by CYP1A2

polymorphisms. Br J Nutr. 119:792–800. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Popa LC, Abu-Awwad A, Farcas SS, Abu-Awwad

SA and Andreescu NI: Genotype-drug-diet interactions in metabolic

regulation: CYP1A2 rs762551 modulates the effect of caffeine on

lipid and glucose profiles in the context of pharmacotherapy.

Nutrients. 17:22882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Islam R, Ahmed M, Ullah W, Tahir YB, Gul

S, Hussain N, Islam H and Anjum MU: Effect of caffeine in

hypertension. Curr Probl Cardiol. 48:1018922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

van Dam RM, Hu FB and Willett WC: Coffee,

caffeine and health. N Engl J Med. 383:369–378. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Vlachopoulos C, Hirata K, Stefanadis C,

Toutouzas P and O'Rourke MF: Caffeine increases aortic stiffness in

hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 16:63–66. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Duda P, Akula SM, Abrams SL, Steelman LS,

Martelli AM, Cocco L, Ratti S, Candido S, Libra M, Montalto G, et

al: Targeting GSK3 and associated signaling pathways involved in

cancer. Cells. 9:1102020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Ku BM, Lee YK, Jeong JY, Ryu J, Choi J,

Kim JS, Cho YW, Roh GS, Kim HJ, Cho GJ, et al: Caffeine inhibits

cell proliferation and regulates PKA/GSK3β pathways in U87MG human

glioma cells. Mol Cells. 31:275–279. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ma Y, Wang X and Tang N: Downregulation of

mPGES-1 Expression via EGR1 plays an important role in inhibition

of caffeine on PGE2 synthesis of HBx(+) hepatocytes. Mediators

Inflamm. 2015:3727502015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gao L, Sun W, Zhang L, Liang C and Zhang

D: Caffeine upregulates SIRT3 expression to ameliorate

astrocytes-mediated HIV-1 Tat neurotoxicity via suppression of EGR1

signaling pathway. J Neurovirol. 30:286–302. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Muñiz JA, Prieto JP, González B, Sosa MH,

Cadet JL, Scorza C, Urbano FJ and Bisagno V: Cocaine and caffeine

effects on the conditioned place preference test: Concomitant

changes on early genes within the mouse prefrontal cortex and

nucleus accumbens. Front Behav Neurosci. 11:2002017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Qin Y, Li J, Zhou Y, Yin C, Li Y, Chen M,

Du Y, Li T and Yan J: Apolipoprotein D as a potential biomarker and

construction of a transcriptional regulatory-immune network

associated with osteoarthritis by weighted gene coexpression

network analysis. Cartilage. 13 (Suppl 1):1702S–1717S. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chhotaray S and Jal S: Identifying

biomarkers for atherosclerosis via gene expression and biological

networking. Curr Cardiol Rev. 21:e1573403X3401182025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wu X, Pan T, Fang Z, Hui T, Yu X and Liu

C, Guo Z and Liu C: Identification of EGR1 as a key diagnostic

biomarker in metabolic Dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease (MASLD) through machine learning and immune analysis. J

Inflamm Res. 18:1639–1656. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li Z, Yu P, Wu J, Tao F and Zhou J:

Transcriptional regulation of early growth response Gene-1 (EGR1)

is associated with progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

(NAFLD) in patients with insulin resistance. Med Sci Monit.

25:2293–3004. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zamini N, Mirzadeh H, Solouk A and

Shafipour R: Injectable in situ forming hydrogel based on

carboxymethyl chitosan for sustained release of hyaluronic acid: A

viscosupplement for biomedical applications. Carbohydr Polym.

352:1232272025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Putzu M, Causa F, Nele V, de Torre IG,

Rodriguez-Cabello JC and Netti PA: Elastin-like-recombinamers

multilayered nanofibrous scaffolds for cardiovascular applications.

Biofabrication. 8:0450092016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhong H, Chen K, Feng M, Shao W, Wu J,

Chen K, Liang T and Liu C: Genipin alleviates high-fat diet-induced

hyperlipidemia and hepatic lipid accumulation in mice via

miR-142a-5p/SREBP-1c axis. FEBS J. 285:501–517. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|