Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD), a heterogeneous

pulmonary parenchymal disease, is a major cause of pulmonary

fibrosis characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the lung

parenchyma (1). The etiology of

most ILDs remains unknown, with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

being the most common and characterized by progressive lung tissue

hardening, breathing difficulties, and eventual respiratory failure

(2). Known ILDs include connective

tissue disease (CTD)-ILD, which is more likely to develop into

progressive fibrosing ILD (PF-ILD), particularly in patients with

conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus

erythematosus, polymyositis and dermatomyositis, with PF-ILD

progression rates as high as 20% (3,4).

Fibrosis is primarily caused by the activation of fibroblasts,

which is triggered by chronic injury or inflammation, resulting in

cell destruction and abnormal tissue repair. Fibroblasts migrate to

injury sites, release growth factors and profibrotic mediators, and

transform into myofibroblasts that secrete excessive amounts of

extracellular matrix, causing tissue stiffness and progressive

interstitial pneumonia (5,6). All PF-ILDs are triggered by chronic

epithelial or vascular injury or granulomatous inflammation,

leading to abnormal repair processes and ultimately causing

fibrosis (5,6).

Human parvovirus B19 (B19V), a member of the

Erythrovirus genus within the Parvoviridae family, is a

small, non-enveloped virus with a linear, single-stranded DNA

genome (7). The capsid of B19V is

a stable icosahedral structure composed mainly of viral protein

(VP) 1 and VP2 proteins. VP1 and VP2 are identical except for a

unique 227-amino-acid region at the N-terminus of VP1 (VP1u)

(8). The unique VP1 region (VP1u)

of B19V plays roles in viral tropism, uptake, and nuclear entry. It

contains a nuclear localization signal, targets erythroid

progenitor cells, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies

(8). The nonstructural protein

(NS)-1 of B19V is essential for viral DNA replication and gene

regulation. B19V NS1 contains nuclear localization signals, a

DNA-binding/nuclease domain, an ATPase and NTP-binding motif, and a

transactivation domain (7,8). B19V NS1 can transactivate host genes,

induce apoptosis, cause cell cycle arrest, and elicit inflammatory

cytokines and DNA damage responses (7,8).

Although most individuals infected with B19V are

asymptomatic or present with mild, nonspecific symptoms resembling

those of the common cold (7–9),

accumulating evidence has linked B19V to the pathogenesis of ILDs

(10–12). B19V has been associated with

chronic vasculopathy syndromes, including Wegener's granulomatosis,

dermatomyositis, and scleroderma (13–15)

and has been implicated in the progression of IPF through the

induction of endothelial immunogenicity (16). Case reports and clinical studies

have identified B19V DNA in lung biopsies and BALF from ILD

patients (11,17) and morphological evidence of septal

capillary injury has been observed in ILD case series with chronic

B19V infection (18).

Despite this, the mechanisms underlying the role of

B19V in ILD remain unclear. Prior studies have shown that B19V NS1

can transactivate expression of the IL-6 gene (19,20),

a cytokine recognized as a key mediator and biomarker of lung

fibrosis (21,22). An in vitro study

demonstrated that B19V can also activate human dermal fibroblasts,

indicating its role in fibrosis and systemic sclerosis (23). Given the antifibrotic effects of

nintedanib in patients with CTD-ILD, the present study was

conducted to elucidate the effect of B19V NS1 on pulmonary fibrosis

using a bleomycin (BLM)-treated mouse model and to evaluate the

therapeutic effect of nintedanib, thereby clarifying the

mechanistic association between B19V infection and ILD in CTD

patients.

Materials and methods

Human samples of CTD patients

A total of 86 patients diagnosed with CTD (19 males

and 67 females, aged 34–84 years) with or without ILD according to

the clinical criteria (24) were

recruited between November 1, 2021 and October 31, 2024, at the

Rheumatology and Immunology Center of the China Medical University

Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan. The China Medical University Hospital's

Institutional Review Board approved the current study (IRB approval

no. CMUH110-REC2-178) and all participants provided written

informed consent following the Declaration of Helsinki's ethical

guidelines for medical research involving human subjects.

Peripheral blood samples (10 ml) were collected into glass tubes

containing no additive or anticoagulant. The clotted blood samples

were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the sera were

collected and stored at −80°C until use. Human parvovirus B19

infection was determined using parvovirus B19V IgM and IgG ELISA

kits (cat. nos. IB79807 and IB79806; IBL-America), and

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was determined using CMV IgM and

IgG test system (ZEUS Scientific, Inc.) from serum samples

according to the manufacturer's instructions. COVID-19 infection

was determined using the cobas SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test (Roche

Molecular Diagnostics) from nasopharyngeal swab samples. Herpes

zoster was determined to be caused by a varicella-zoster virus

infection, as indicated by the presence of the virus in blood or

urine samples.

Animals and treatments

A total of 25 male C57BL/6 mice (age, 6 weeks;

weight, 17–19 g) were obtained from the National Laboratory Animal

Center and housed at Chung Shan Medical University under controlled

lighting (12-h light/dark cycle), temperature (22–24°C) and

humidity (50–60%) conditions, with free access to water and

standard laboratory chow (Lab Diet 5001; PMI Nutrition

International Inc.). The experimental protocols were approved by

the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Chung Shan Medical

University, Taiwan (IACUC approval nos. 2803 and 112065). Based on

a previous publication, a BLM-induced lung fibrosis mouse model was

performed (25). Bleomycin,

commonly administered intratracheally in mice, is widely used for

pulmonary fibrosis models due to its ability to induce cellular

damage and fibrosis (2,26). The present study employed the

intratracheal administration route. At eight weeks of age, the mice

were randomly divided into five groups (n=5 per group): i) Control

(PBS) group; ii) Bleomycin (BLM) group; iii) BLM + nintedanib

group; iv) BLM + NS1 group; and v) BLM + NS1 + nintedanib group.

The Control and BLM groups received intratracheal PBS and

intratracheal BLM (3 mg/kg) on day 0, respectively. The BLM +

nintedanib group received intratracheal BLM on day 0 and nintedanib

(50 mg/kg) intraperitoneally every 2 days, starting from day 10,

for a total of 5 injections (27).

The BLM + NS1 group received intratracheal BLM (3 mg/kg) and

B19V-NS1 recombinant protein (0.8 mg/kg) on day 0. The BLM + NS1 +

nintedanib group received intratracheal BLM (3 mg/kg) and B19V-NS1

recombinant protein (0.8 mg/kg) on day 0. nintedanib (50 mg/kg) was

administered intraperitoneally every 2 days, starting from day 10,

for a total of 5 injections. On day 19, the mice were sacrificed

using a carbon dioxide (CO2) euthanasia chamber. The

CO2 flow rate was 50% of the chamber volume/min. After

visually confirming that the mice had stopped breathing, the

CO2 flow was maintained for an additional minute to

ensure mortality. Then, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and

lung tissues were collected.

Hydroxyproline analysis

Lung tissues were processed and hydrolyzed according

to the manufacturer's instructions using a Hydroxyproline Assay Kit

(ab222941, Abcam). After homogenization, hydrolysis, and

neutralization, samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at

4°C and dried. The hydroxyproline standard curve was generated, and

absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a SpectraMax M5 Microplate

Reader (Molecular Devices LLC).

BALF

The collection of BALF was performed as described

previously (28). Briefly, mice

were sacrificed and 1 ml of PBS was injected into the trachea and

aspirated three times. The collected lavage fluid was centrifuged

at 200 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was reserved for

ELISA analysis. Additionally, the cell pellet was re-suspended in

150 µl of PBS, and the cell populations were detected using a

cytospin to prepare the slides, which were then stained with Liu's

stain (Liu's A for 30 sec and Liu's B for 90 sec at room

temperature) for microscopic observation and enumeration of

macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.

ELISA

A total of 100 µl BALF samples was added to the

ELISA plate wells and incubated at 37°C for 90 min. After washing,

a biotinylated antibody (100 µl) was added and incubated for 60 min

at the same temperature. The wells were then washed, and 100 µl

enzyme conjugate was added for a 30-min incubation. Subsequently,

substrate (100 µl) was added and incubated in the dark at 37°C

after washing thoroughly. The quantification of essential ILD

biomarkers, including interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor

(TNF)-α, and Krebs von den Lungen (KL)-6 (29,30),

was performed by duplicating ELISA kits for mouse IL-6, TNF-α

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and KL-6

(MyBioSource, Inc.), following the manufacturer's protocol.

Absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Histological analysis

Histological evaluation of lung tissues was

performed with paraffin sections undergoing hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E) staining and Masson's trichrome staining. For H&E

staining, the tissues were immersed in 10% formalin at 25°C for 24

h and then embedded in paraffin. The tissue blocks were sliced into

5-µm sections, deparaffinized using xylene, and dehydrated by

passing through decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100, 90, 80

and 70%) and water. Subsequently, the slides were stained with

hematoxylin for 3 min at 25°C, rinsed with water and stained with

eosin for 5 min at 25°C. Each slide was subsequently immersed in 95

and 100% ethanol twice (1 min each immersion). Finally, the slides

were immersed in xylene twice for 2 min and then air-dried. For

Masson's trichrome staining, sections were deparaffinized,

rehydrated, and incubated in Bouin's fluid at 60°C for 60 min. They

were stained with Weigert's hematoxylin for 2 min at 25°C, Biebrich

scarlet/acid fuchsin for 10 min and aniline blue for 10 min at

25°C. Finally, sections were treated with 1% acetic acid,

dehydrated, cleared, and mounted, with collagen fibers staining

blue, muscle fibers red, cytoplasm pink and nuclei dark brown or

black. Photomicrographs were observed using TissueFAX Plus

(TissueGnostics GmbH) to analyze stained sections. A total of five

100-µm fields of view were examined in each section. The fibrosis

score was evaluated and graded using the modified Ashcroft score

(31). Grade 0 signified normal

lung tissue without fibrosis, and grades 1–8 represent varying

levels of fibrosis from minor to serious.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The aforementioned paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm)

were fixed in acetone for 5 min at 25°C, air-dried for 10 min, and

then immersed in 0.3% H2O2/PBS for 5 min at

25°C to block peroxidase activity and blocked with 3% BSA

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in PBS + 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween) for

1 h at 25°C. After washing twice with PBS-Tween, each for 10 min,

antibodies against transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (1:100; cat.

no. A16640; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), collagen I (1:100; cat.

no. A5786; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), IL-18 (1:200; cat. no.

A23076; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), IL-17A (1:200; cat. no.

A12454; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), citrullinated histone H3

(Cit-H3; (1:100; cat no. ab5103; Abcam) and myeloperoxidase (MPO;

1:500; cat. no. ab208670; Abcam) were applied and incubated for 1

h, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled

secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. sc-2004; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h. Sections were developed with DAB for

3 min, then washed with distilled water for an additional 5 min.

Subsequently, hematoxylin was used as a counterstain for 3 min at

25°C and the sections were washed with distilled water for 10 min.

The sections were then dehydrated using a graded ethanol series

(80, 95 and 100%; 5 min each), followed by immersion in xylene

twice for 5 min each and air-drying. A tissue quantification

analyzer (TissueFAX Plus; TissueGnostics GmbH) was used to analyze

stained sections, counting positive cells in randomly selected

fields and comparing the results with those of a negative control.

A total of five 100 µm fields of view were examined in each

section, across five fields of view counted and averaged.

Statistical analysis

Data were recorded and analyzed using Excel

(Microsoft Corporation) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics)

software. Experimental results are presented as mean ± SD, and

statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Fibrosis score results

were presented as medians and ranges and were analyzed using

one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's post hoc

test. BALF cell counts were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with

Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test, and the χ2

test was used to determine the significant differences in clinical

characteristics between the data sets. P<0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Prevalence of B19V infection in CTD

patients

As illustrated in Table

I, B19V infection (24/33 vs. 12/53; P<0.001) and

hypertension (14/33 vs. 11/53; P=0.03) were significantly more

prevalent in CTD patients with ILD than in those without ILD. By

contrast, no significant differences were detected in age at study

entry, sex distribution, smoking status, disease duration, CMV,

COVID-19, herpes zoster infection, or diabetes mellitus or

cardiovascular disease status between the two groups. In terms of

CTD type, among the 53 CTD patients without ILD, 50 had RA, one had

idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM), and two had systemic

sclerosis (SSc). Among the 33 CTD patients with ILD, 25 had RA,

five had IIM, and three had SSc. Additionally, the ILD subtypes

included 26 cases of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, five cases

of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), and two cases of organizing

pneumonia (OP).

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of 86 CTD

patients with or without ILD. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of 86 CTD

patients with or without ILD.

| Clinical

characteristic | CTH without ILD

(n=53) | CTH with ILD

(n=33) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years (mean ±

SD) [range] | 56.2±8.6

[34-75] | 61.8±9.9

[36-84] |

|

| Female (n=67) | 43 | 24 | 0.36 |

| Smoking (n=12) | 7 | 5 | 0.80 |

| B19V IgM or IgG (+)

(n=36) | 12 | 24 |

<0.001a |

| CMV IgM or IgG (+)

(n=67) | 41 | 26 | 0.84 |

| COVID-19 (+)

(n=33) | 19 | 14 | 0.54 |

| Herpes zoster

(n=19) | 15 | 4 | 0.08 |

| CTD duration,

years | 9.6±2.7 | 10.7±2.6 |

|

| CTD types |

|

|

|

| RA | 50 | 25 |

|

|

IIM | 1 | 5 |

|

| SSc | 2 | 3 |

|

| ILD patterns by

HRCT |

|

|

|

|

NSIP | NA | 26 | NA |

|

UIP | NA | 5 | NA |

| OP | NA | 2 | NA |

| Hypertension

(n=25) | 11 | 14 | 0.03a |

| DM (n=8) | 3 | 5 | 0.14 |

| CVD (n=9) | 4 | 5 | 0.26 |

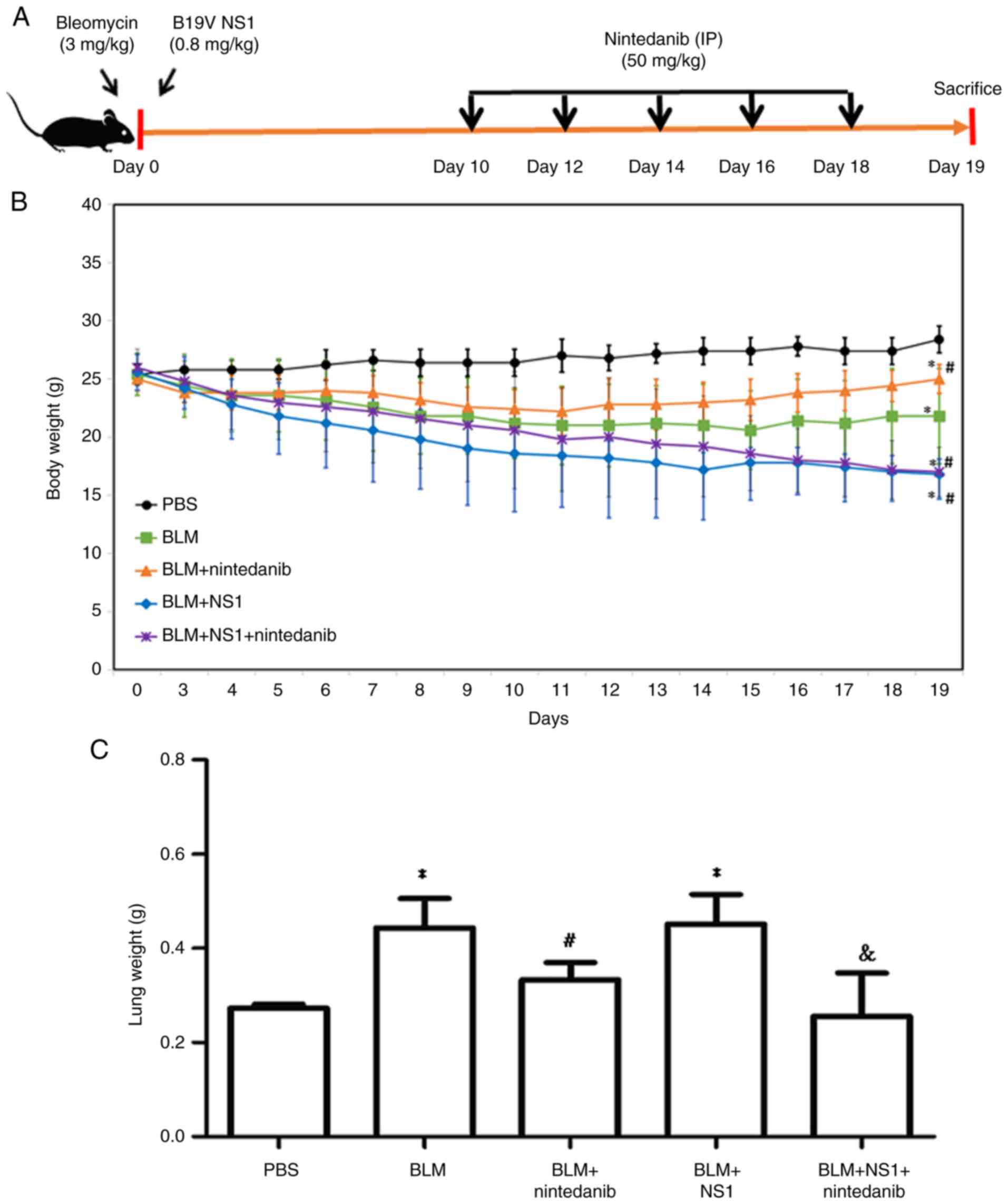

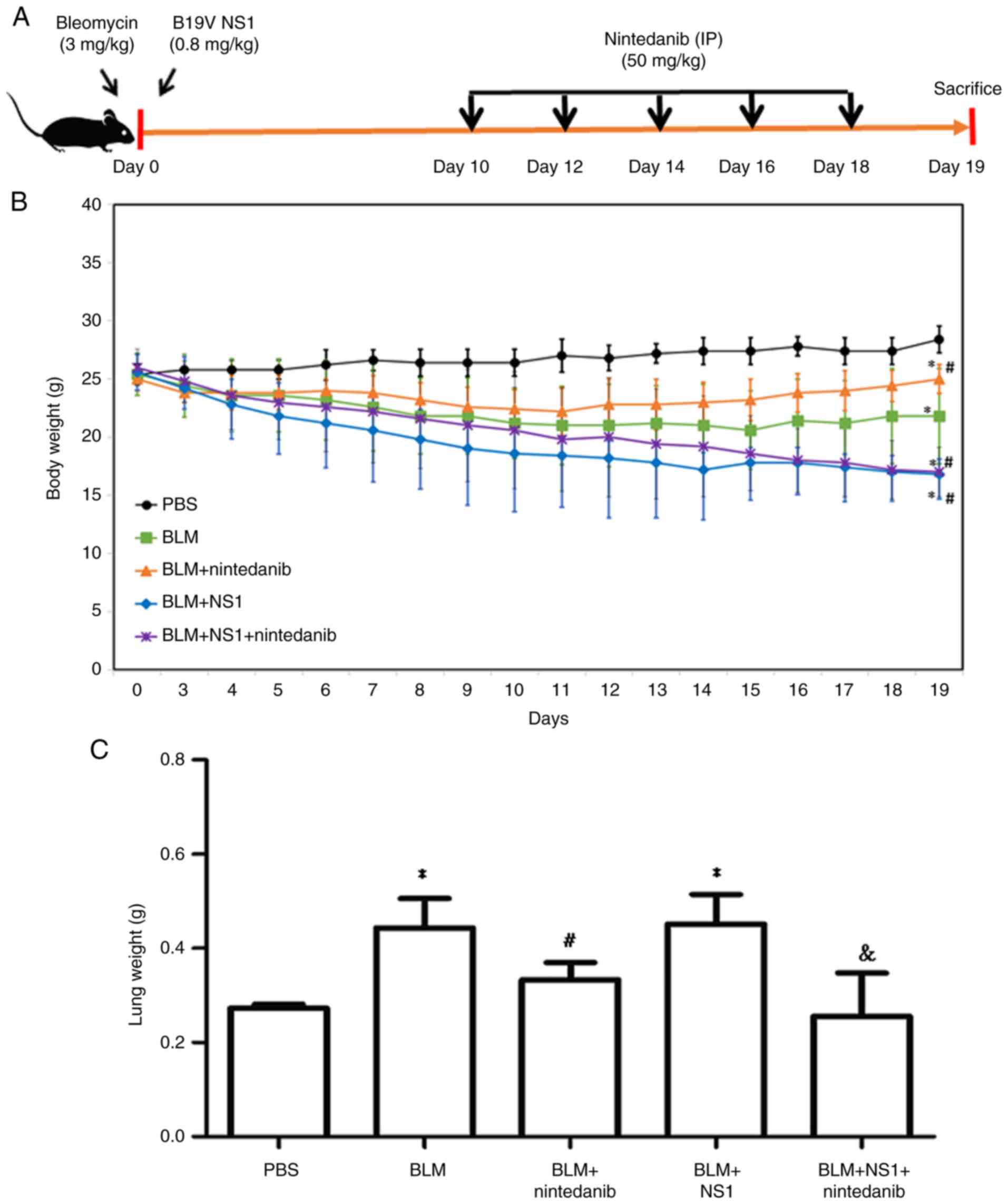

Influence of B19V NS1 on body weights,

lung weights, and survival rate in mice with BLM-induced pulmonary

fibrosis

To assess the effects of B19V NS1 on BLM-induced

pulmonary fibrosis, the body weights of the mice were recorded

daily until day 19. By contrast, lung weights were measured on day

19 (Fig. 1A). Compared with those

of the control group, the body weights of the mice in the BLM, BLM

+ nintedanib, BLM + NS1, and BLM + NS1 + nintedanib groups

significantly decreased (Fig. 1B;

P=0.008, 0.002, <0.001 and <0.001, respectively). Treatment

with nintedanib improved body weight loss in mice from both the BLM

and the BLM + NS1 groups but was not sufficient to restore normal

weight (Fig. 1B). Compared with

the mice in the PBS group, the mice in the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups

had significantly greater lung weights (P=0.025 and 0.037,

respectively), whereas normal lung weight was restored in the

nintedanib treatment groups (Fig.

1C; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.035; BLM + NS1 + nintedanib

vs. BLM + NS1, P=0.044).

| Figure 1.Effects of nintedanib and B19V NS1 on

bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. (A) Schematic diagram

of the experimental animal model. (B) Daily body weight

measurements across the PBS, BLM, BLM + nintedanib, BLM + NS1, and

BLM + NS1 + nintedanib groups (BLM vs. PBS, P=0.008; BLM +

nintedanib vs. PBS, P=0.002; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM +

nintedanib + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM, P=0.031;

BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM, P=0.048; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs.

BLM + nintedanib, P<0.001). (C) Lung weight of mice on day 19

(BLM vs. PBS, P=0.025; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P=0.037; BLM + nintedanib

vs BLM, P=0.035; BLM + NS1 + nintedanib vs BLM + NS1, P=0.044).

*P<0.05 vs. the PBS (Control) group, #P<0.05 vs.

the BLM group, and &P<0.05 vs. the BLM + NS1

group. B19V, human parvovirus B19; NS1, nonstructural protein 1;

BLM, bleomycin. |

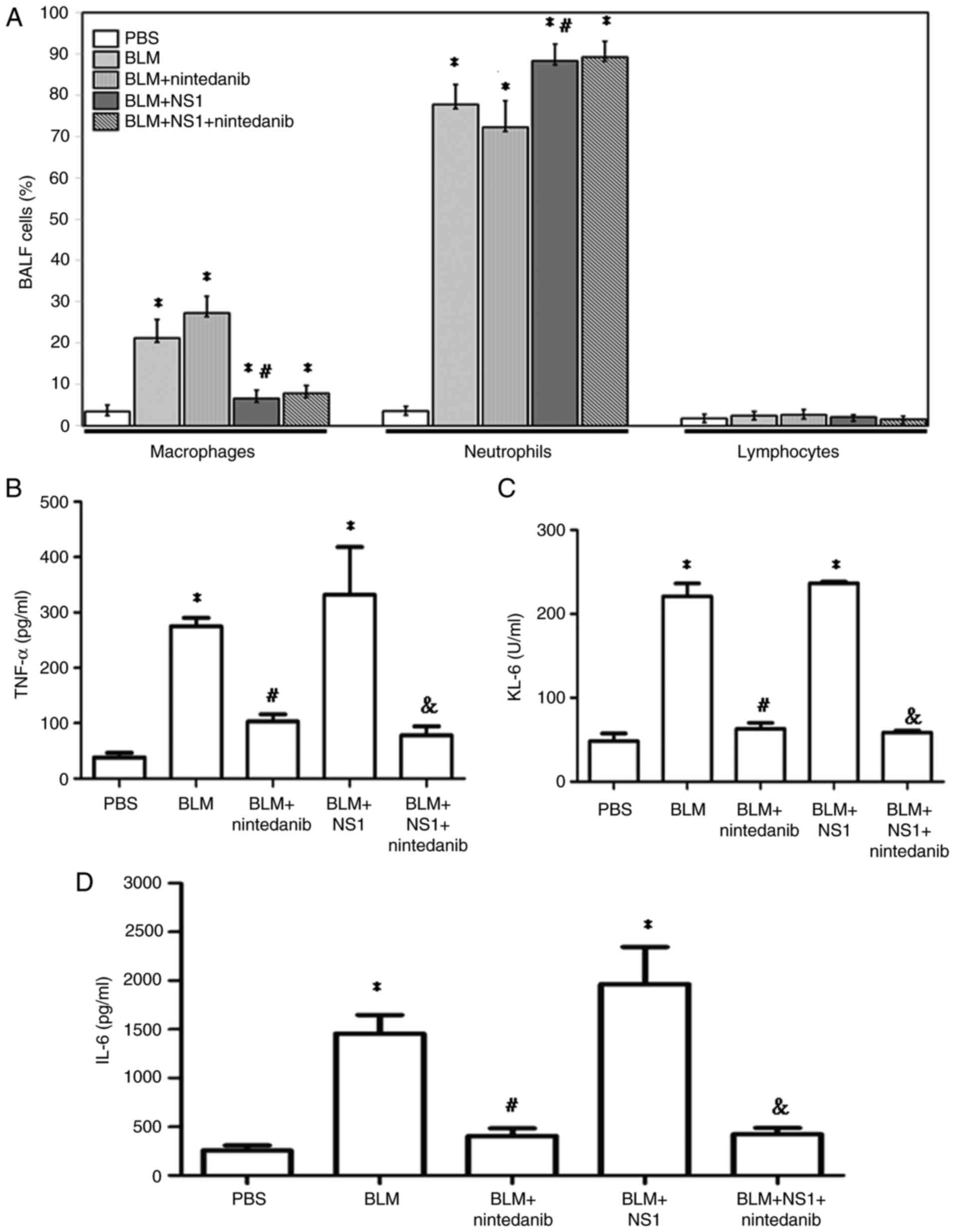

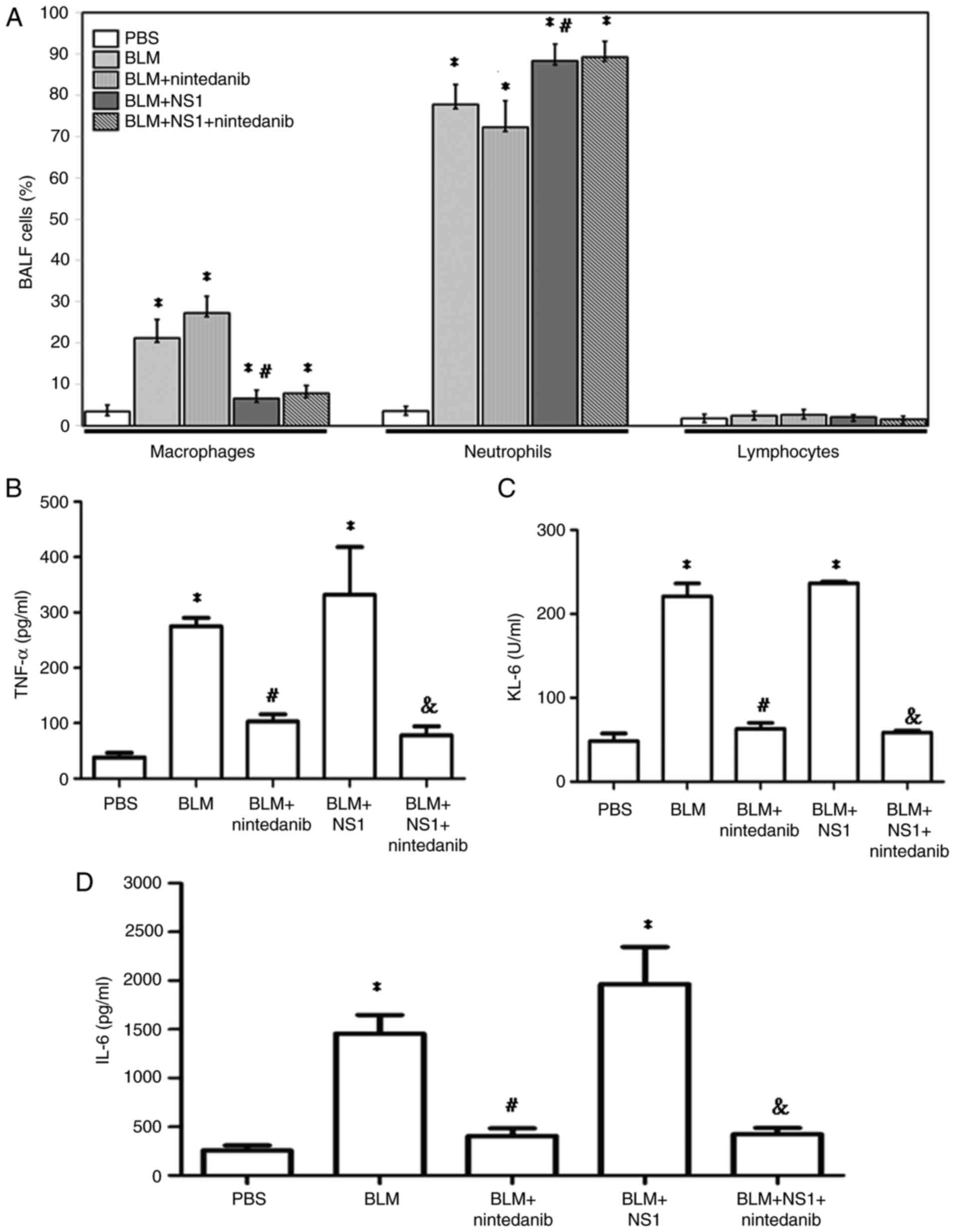

B19V NS1 administration changes immune

cell compositions and increases levels of fibrotic markers in the

BALF of mice with BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis

To evaluate the influence of B19V NS1 on immune cell

distribution in the BALF of mice treated with BLM, the proportions

of macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes were analyzed. No

significant difference in lymphocyte proportion was observed among

the groups (Fig. 2A). Treatment

with BLM resulted in a significant increase in the numbers of

macrophages and neutrophils. Treatment with nintedanib partially

reversed this trend by increasing the number of macrophages and

reducing the number of neutrophils. Notably, the proportions of

neutrophils remained elevated in the BLM + NS1 + nintedanib group,

indicating that the NS1-induced effects were not fully mitigated by

nintedanib (Fig. 2A; macrophages:

BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM

+ NS1 vs. PBS, P=0.02; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. PBS, P=0.005; BLM

+ NS1 vs. BLM, P<0.001; neutrophils: BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001;

BLM + nintedanib vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS,

P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; and BLM +

NS1 vs. BLM, P=0.006). Additionally, an ELISA was performed to

measure the levels of lung fibrosis-related markers, including

TNF-α, KL-6, and IL-6, in the BALF. Compared with those in the

control group (PBS), TNF-α (Fig.

2B; P=0.014 and 0.003, respectively), KL-6 (Fig. 2C; P<0.001 and P<0.001,

respectively) and IL-6 (Fig. 2D;

P=0.039 and 0.009, respectively) levels in the BALF of mice from

the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups were markedly elevated. nintedanib

treatment significantly reduced the expression of these markers in

the BALF of mice from both the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups (Fig. 2B-D; TNF-α, BLM + nintedanib vs.

BLM, P=0.039; BLM + NS1 + nintedanib vs. BLM + NS1, P=0.009; KL-6,

BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 + nintedanib vs.

BLM + NS1, P<0.001; IL-6, BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.013; BLM

+ NS1 + nintedanib vs. BLM + NS1, P=0.014).

| Figure 2.Proportions of immune cells in BALF

of mice. (A) Percentages of macrophage, neutrophil, and lymphocyte

in BALF of mice from different groups (Macrophages: BLM vs. PBS,

P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs.

PBS, P=0.02; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. PBS, P=0.005; BLM + NS1 vs.

BLM, P<0.001; Neutrophils: BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM +

nintedanib vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM

+ nintedanib + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM, P=0.01).

The concentrations of (B) TNF-α (BLM vs. PBS, P=0.014; BLM + NS1

vs. PBS, P=0.003; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.039; BLM +

nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1 P=0.009), (C) KL-6 (BLM vs. PBS,

P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs.

BLM, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1 P<0.001)

and (D) IL-6 (BLM vs. PBS, P= 0.039; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P=0.009;

BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.013; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM +

NS1, P=0.014) in BALF of mice from different groups. *P<0.05 vs.

the PBS (Control) group, #P<0.05 vs. the BLM group,

and &P<0.05 vs. the BLM + NS1 group. BALF,

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; BLM, bleomycin; NS1, nonstructural

protein 1; IL, interleukin. |

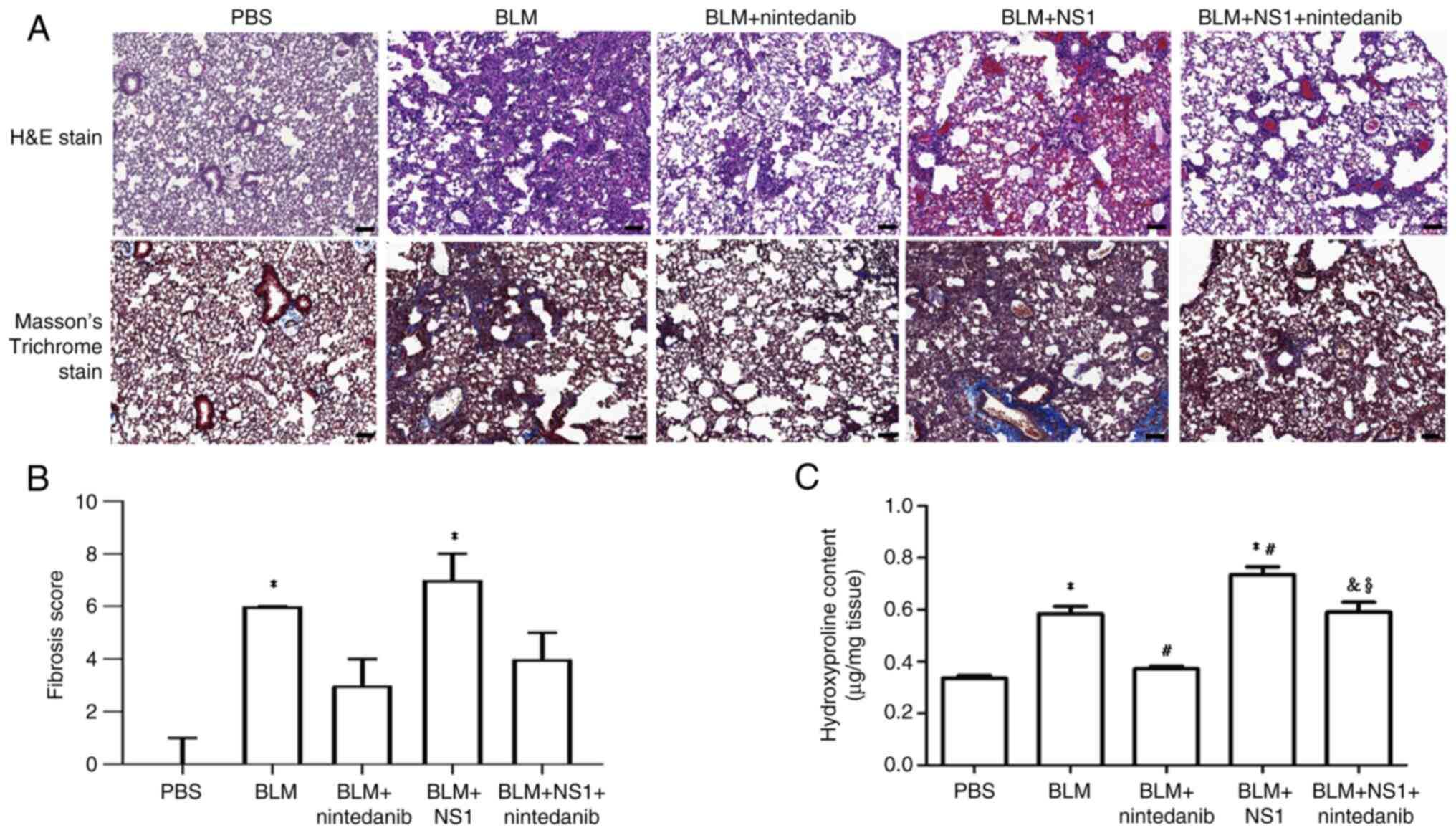

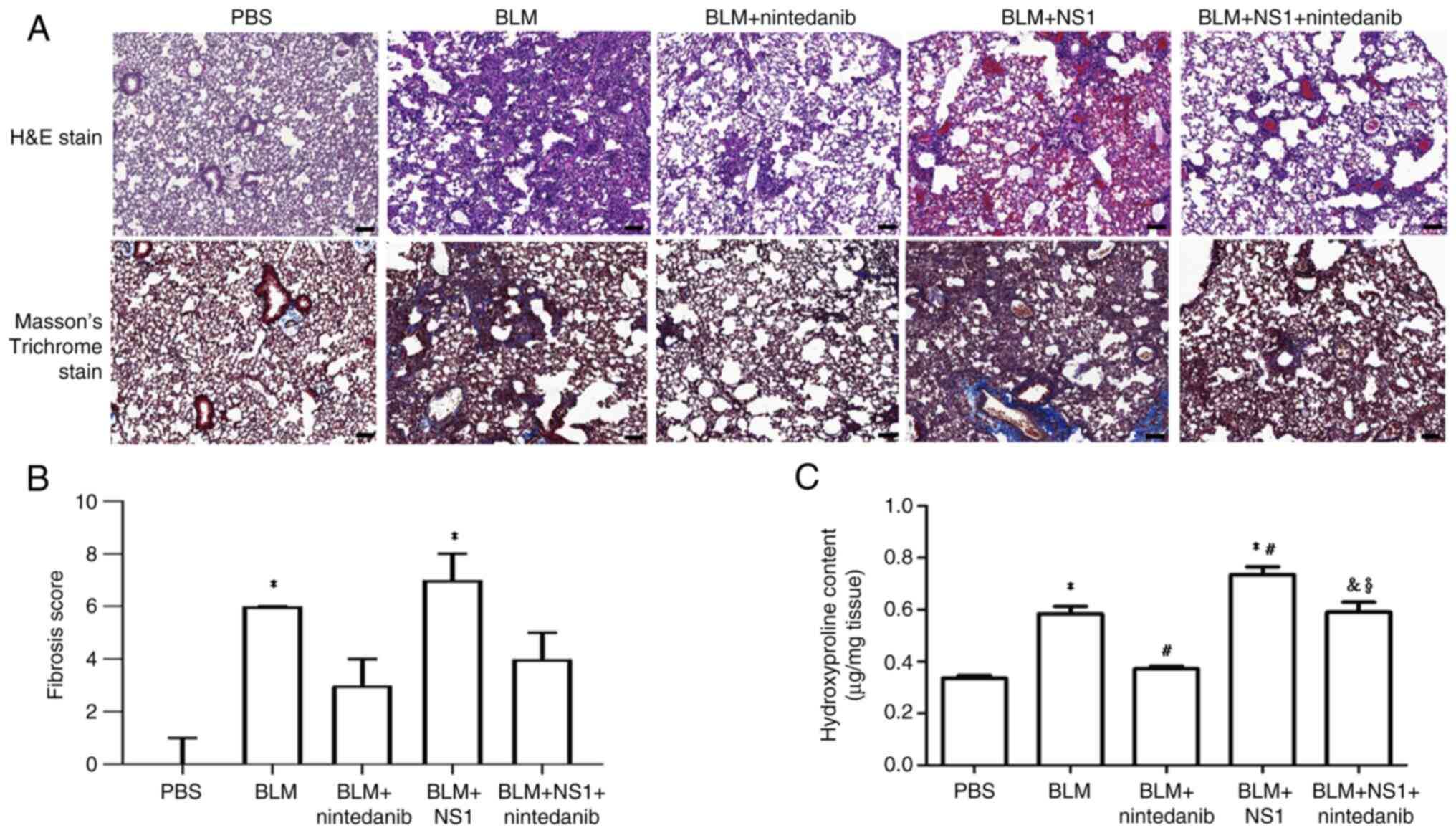

B19V NS1 administration increases the

lung fibrosis score and hydroxyproline content in mice with

BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis

Histological analyses were also performed to assess

the effect of B19V NS1 on BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice.

Significantly higher fibrosis scores were observed in the lungs of

mice from the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups than in those from the PBS

group (P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively). Nintedanib reduced

fibrosis levels in both the BLM + nintedanib group [3 (3–4)] and

the BLM + NS1 + nintedanib group [4 (4–5)]

(Fig. 3A-B). However, the lung

fibrosis score remained more severe in the mice from the BLM + NS1

group [7 (7–8)] than in those from the BLM group [6

(5–7)] (Fig.

3B). Similarly, lung hydroxyproline content, an indicator of

collagen deposition, was significantly greater in the lungs of mice

from the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups than in those from the PBS group

(P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). Hydroxyproline levels

remained higher in the mice in the BLM + NS1 group than in the mice

in the BLM group (P=0.016). Nintedanib treatment markedly reduced

hydroxyproline levels, although the reduction was more pronounced

in the BLM group and the BLM + NS1 group (P=0.004 and P=0.036,

respectively) (Fig. 3C). Notably,

significantly higher hydroxyproline levels were detected in the BLM

+ NS1 + nintedanib group than in the BLM + nintedanib group

(P=0.006) (Fig. 3C). Moreover,

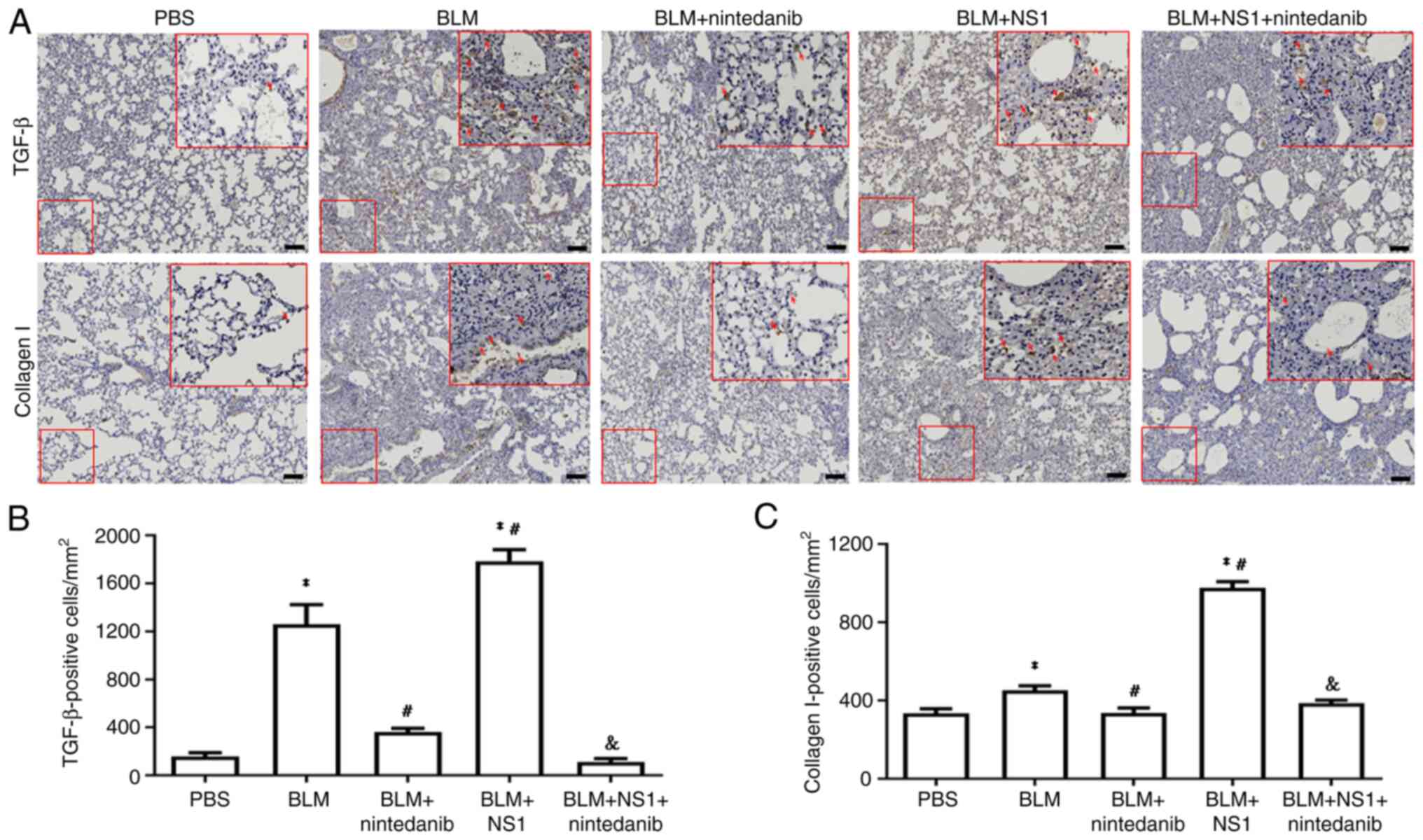

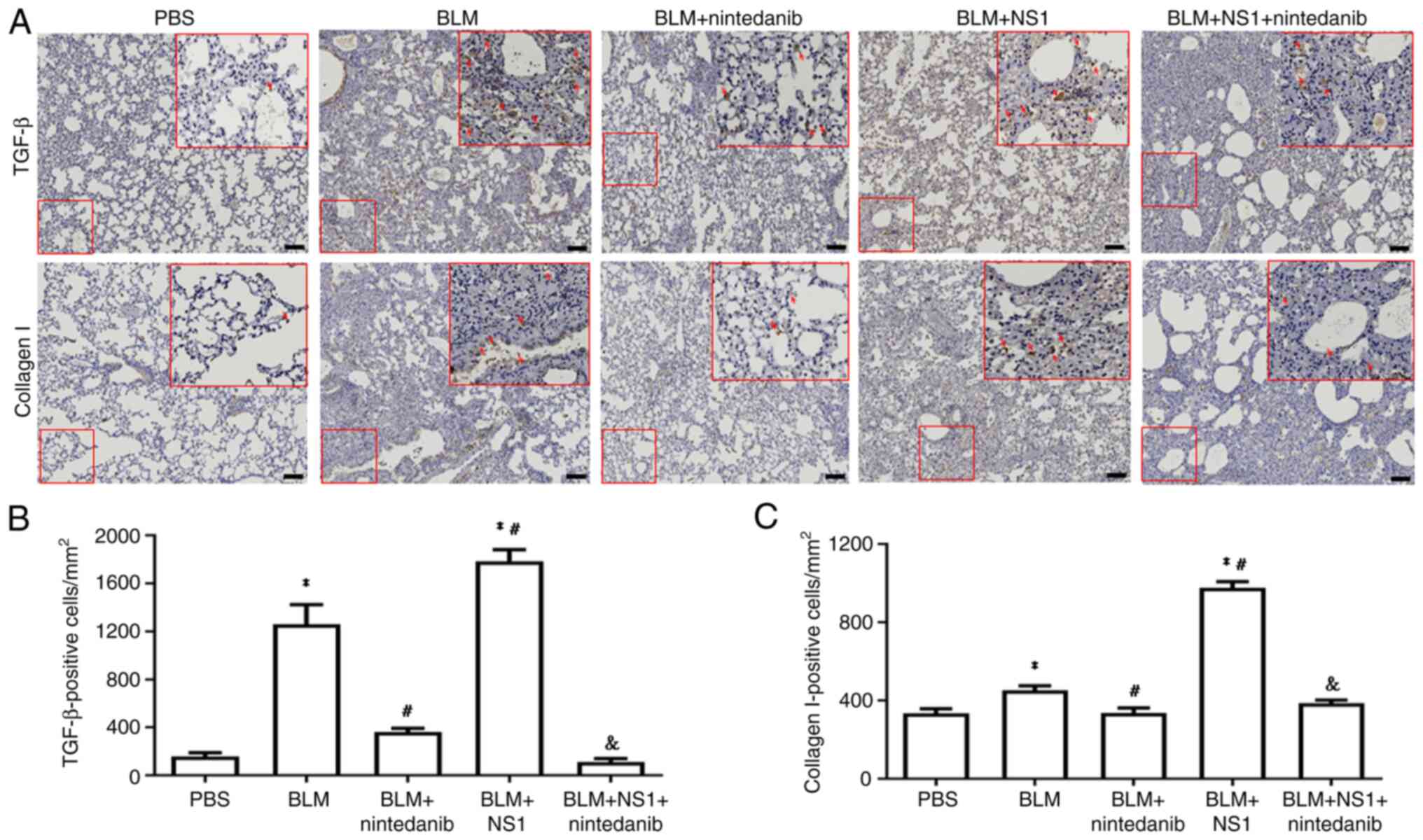

quantification of key fibrotic marker levels, including those of

TGF-β and collagen I, revealed that compared with BLM treatment

alone, B19V NS1 administration significantly exacerbated fibrosis

(P=0.015 and P<0.001, respectively). Conversely, the

administration of nintedanib reduced the levels of these markers in

mice from both the BLM and the BLM + NS1 groups (Fig. 4A-C; TGF-β: BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001;

BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.001;

BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001; collagen I: BLM

vs. PBS, P=0.019; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib

vs. BLM, P=0.024; and BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1,

P<0.001).

| Figure 3.Histological staining of the lung

tissues of mice. (A) Representative images of H&E and Masson's

trichrome-stained mouse lung sections. Scale bar, 100 µm.

Quantified result of (B) fibrosis score (BLM vs. PBS, P<0.05;

BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001) and (C) hydroxyproline content (BLM

vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM +

nintedanib vs. BLM, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM, P= P=0.016; BLM

+ nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P=0.036; BLM + NS1 + nintedanib

vs. BLM + nintedanib, P=0.006). *P<0.05 vs. the PBS (Control)

group, #P<0.05 vs. the BLM group,

&P<0.05 vs. the BLM + NS1 group, and

§P<0.05 vs. the BLM + nintedanib group. H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin; BLM, bleomycin; NS1, nonstructural protein

1. |

| Figure 4.IHC staining of lung tissue of mice.

(A) Representative images of lung sections of mice stained with

TGF-β and collagen I. Scale bar, 100 µm. Quantified results of (B)

TGF-β (BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM

+ nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM, P=0.015; BLM +

nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001) and (C) collagen I

positive cells (BLM vs. PBS, P=0.019; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS,

P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.024; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM,

P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001) in

lung sections of mice. *P<0.05 vs. the PBS (Control) group,

#P<0.05 vs. the BLM group, and

&P<0.05 vs. the BLM + NS1 group. IHC,

immunohistochemistry; TGF transforming growth factor; BLM,

bleomycin; NS1, nonstructural protein 1. |

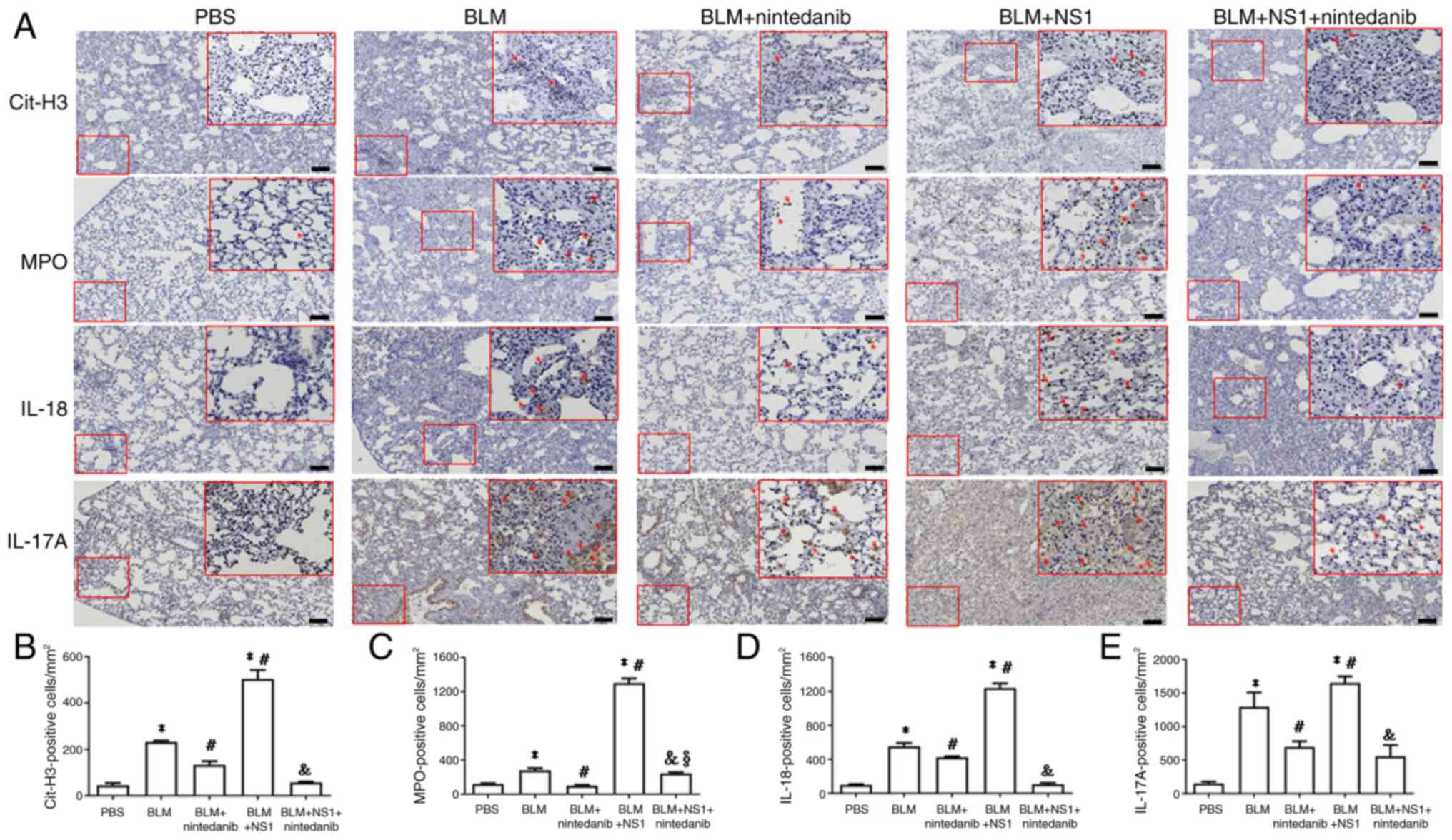

B19V NS1 administration increases

neutrophil and inflammasome involvement in the lungs of mice with

BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis

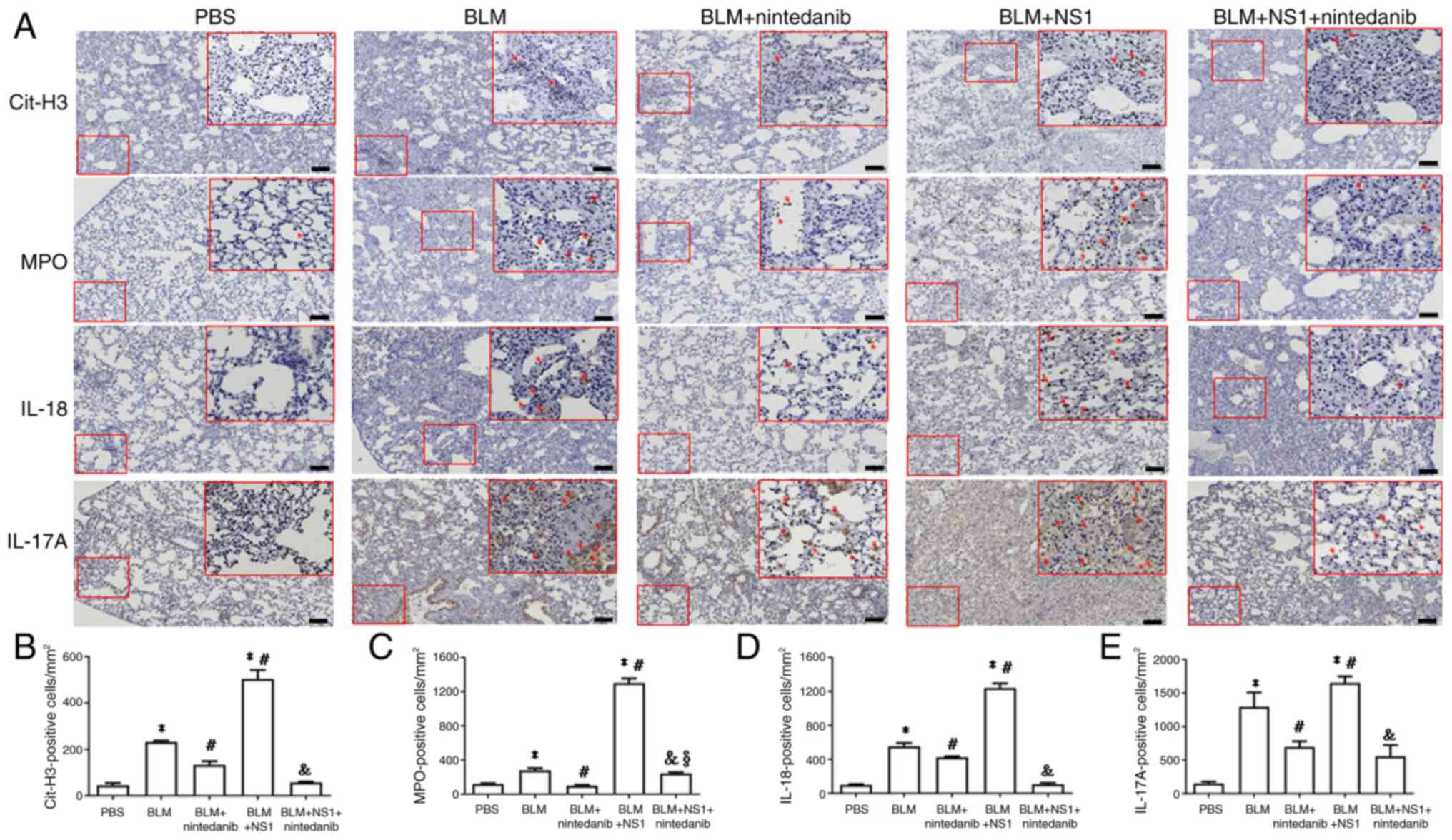

To confirm the involvement of neutrophils in the

lungs of mice with BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis treated with B19V

NS1, levels of key neutrophil-related markers, including Cit-H3 and

MPO, were determined. Significantly elevated Cit-H3 (P<0.001 and

P<0.001, respectively) and MPO (P=0.001 and P<0.001,

respectively) expression was detected in lung sections from mice in

the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups compared with those from the PBS group

(Fig. 5A-C), reflecting heightened

neutrophil responses. Conversely, nintedanib treatment

significantly reduced the levels of Cit-H3 (P=0.013 and P<0.001,

respectively) and MPO (P=0.001 and P<0.001, respectively)

compared with those in the BLM and BLM + NS1 groups. However,

significantly more MPO-positive signals were detected in the BLM +

NS1 + nintedanib group than in the BLM + nintedanib group (P=0.015;

Fig. 5C). Additionally, the

expression of inflammasome signaling factors, including IL-18 and

IL-17A, significantly increased in the lungs of mice in the BLM and

BLM + NS1 groups compared with those in the control group (IL-18:

P<0.001 and P<0.001; IL-17A: P<0.001 and P<0.001,

respectively; Fig. 5D and E).

Significantly reduced levels of IL-18 and IL-17A were observed in

the lung tissues of mice from both the BLM + nintedanib and the BLM

+ NS1 + nintedanib groups (Fig. 5D and

E; IL-18: BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.043; BLM + nintedanib +

NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001; IL-17A: BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM,

P<0.03; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1; P<0.001).

| Figure 5.Expressions of neutrophil-related and

inflammasome markers. (A) Representative immunohistochemistry

images of the lung section of mice stained with (A) Cit-H3, MPO,

IL-18 and IL-17. Scale bar, 100 µm. Quantification of (B) Cit-H3

(BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM +

nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.013; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM, P<0.001; BLM +

nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001), (C) MPO (BLM vs. PBS,

P=0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM,

P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs. BLM, P= P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib +

NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM +

nintedanib, P=0.015), (D) IL-18 (BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1

vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P=0.043; BLM + NS1

vs. BLM, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1,

P<0.001), and (E) IL-17 (BLM vs. PBS, P<0.001; BLM + NS1 vs.

PBS, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib vs. BLM, P<0.03; BLM + NS1 vs.

BLM, P<0.001; BLM + nintedanib + NS1 vs. BLM + NS1, P<0.001)

positive cells in lung sections of mice. *P<0.05 vs. the PBS

(Control) group, #P<0.05 vs. the BLM group,

&P<0.05 vs. the BLM + NS1 group, and

§P<0.05 vs. the BLM + nintedanib group. Cit-H3,

citrullinated histone H3; MPO, myeloperoxidase; IL, interleukin;

BLM, bleomycin; NS1, nonstructural protein 1. |

Discussion

The present study revealed for the first time that

B19V NS1 significantly exacerbates BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis

in mice by increasing inflammation and fibrosis, mainly through

inflammasome activation and neutrophil-driven responses.

Conversely, the administration of nintedanib reduced the expression

of key fibrotic markers, such as IL-18, IL-17A, Cit-H3, and MPO,

suggesting the therapeutic potential of nintedanib in exacerbating

lung fibrosis associated with B19V NS1. In addition, there were

significant differences in the proportions of B19V infection and

hypertension between CTD patients with and without ILD. These

findings revealed a mechanistic link between B19V infection and

ILD, indicating that B19V, through NS1, acts as a potent

exacerbator of ILD, further aggravating fibrosis in patients with

already compromised pulmonary conditions.

Bleomycin induces fibrosis primarily through

reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated oxidative stress, which

triggers epithelial apoptosis, activates fibroblasts and promotes

collagen deposition (32). ROS

also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, promoting fibrosis via the

IL-1β/IL-1R/MyD88/NF-κB pathway and caspase-1-mediated activation

of IL-1β and IL-18 (33–37). These findings are consistent with

previous reports showing that B19V NS1 induces IL-6 and TGF-β

expression and activates fibroblasts (21,23,38–40).

In the present study, compared with BLM alone, combined treatment

with BLM and B19V NS1 resulted in higher levels of

inflammasome-related cytokines and collagen deposition. These

findings provided a possible explanation for why B19V NS1

exacerbates BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis. However, further

studies are needed to clarify the precise role of B19V NS1 in ILD

aggravation.

In a mouse model of BLM-induced fibrosis, neutrophil

recruitment driven by chemokines such as CXCR2 contributes to

tissue damage and fibrosis through the release of NETs,

proinflammatory cytokines, and neutrophil elastase (41–43).

Although evidence for B19V NS1-induced NET formation is limited,

studies on dengue and Zika virus NS1 proteins have demonstrated

their ability to promote NET release through platelet activation

and neutrophil infiltration (44,45).

In the present study, B19V NS1 exacerbated lung fibrosis through

mechanisms that parallel those of BLM, including neutrophil-driven

responses. The elevated levels of neutrophil markers, such as

Cit-H3 and MPO, in the lung tissues of mice treated with both BLM

and B19V NS1 indicated a strong correlation with increased

neutrophil invasion, contributing to the chronic tissue damage

characteristic of BLM-induced fibrosis.

Progressive fibrosing ILD poses a significant

clinical challenge, as conventional treatments for pulmonary

fibrosis often yield poor outcomes and only manage symptoms

(12). nintedanib, a tyrosine

kinase inhibitor targeting platelet-derived growth factor receptor,

fibroblast growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth

factor receptor, exerts antifibrotic and antiangiogenic effects and

is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for

treating IPF and SSc-associated ILD (46–48).

In the current study, MPO and hydroxyproline levels remained

increased in the BLM + NS1 + nintedanib group. Although nintedanib

treatment mitigated several inflammatory and fibrotic responses

exacerbated by NS1 in the BLM model, it did not fully reverse all

pathological changes. These findings suggested that nintedanib only

partly alleviates NS1-exacerbated lung injury and that its efficacy

may be limited in the presence of NS1-mediated fibrosis. Further

studies are needed to explore combination strategies or alternative

treatments that more effectively counteract NS1-driven fibrotic

pathways.

Notably, the present study has several limitations

that should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively

small, particularly in the subgroup of CTD patients with ILD

(n=33), which may limit the statistical power and generalizability

of the findings. These factors may influence disease severity and

outcomes, and their absence could have introduced residual

confounding. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with

caution and further studies with larger, well-characterized cohorts

are needed to confirm these findings in the future. Second, a group

receiving NS1 treatment alone was not included in the present

study. While the primary objective was to investigate the effect of

NS1 in the context of BLM-induced lung injury, the lack of an

NS1-only control group made it difficult to fully determine whether

NS1 itself can independently induce fibrotic changes in the lungs.

Including such a group would help clarify whether the observed

effects are specific to the interaction between NS1 and BLM-induced

injury or partially attributable to NS1 alone. Therefore, future

studies should incorporate an NS1-only group to delineate the

individual more precisely and combined effects of NS1 and BLM on

the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Third, direct mechanistic

evidence to confirm the causal role of neutrophil activation and

inflammasome signaling in the NS1-induced exacerbation of fibrosis

was lacking. While the findings suggested that NS1 may promote

pulmonary fibrosis through enhanced neutrophil activity and

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, these conclusions are

based on correlative data. The absence of experiments employing

specific inhibitors, such as NLRP3 or NETosis inhibitors, limits

the ability of the present study to definitively establish

causality. Therefore, future studies incorporating targeted

inhibition or loss-of-function approaches are needed to validate

these mechanistic links and strengthen the causal interpretation of

our findings. Finally, a key limitation is that the experiments

were conducted in mouse models, which may not fully replicate the

complex pathophysiology of human disease. Consequently, the

findings and therapeutic effects observed here may not directly

translate to humans due to species-specific differences in immune

responses, disease progression, and drug metabolism (49). Therefore, further validation in

clinical settings or human-derived models is necessary to confirm

the relevance of these results to human patients.

Overall, the results of the current study provided a

clinical and mechanistic connection between B19V infection and the

progression of pulmonary fibrosis. The clinical data indicated a

higher incidence of B19V infection among CTD patients with ILD,

suggesting a potential association with the development of ILD.

Experimental findings further demonstrated that B19V, through its

NS1 protein, may exacerbate ILD and worsen fibrosis in patients

already affected by lung conditions, particularly by activating the

inflammasome and driving neutrophil responses. These findings build

on previous evidence of B19V in ILD patients, reinforcing the

possible role of B19V NS1 in exacerbating fibrogenesis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Science and Technology Council (grant no. NSTC 112-2314-B040-015)

and Chung Shan Medical University (grant no. CSMU-INT-113-04). The

funders had no role in the study design, data collection and

analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the

manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Author's contribution

TCH, CCT, DYC and BST were involved in the study

conception and design, drafting and revising of the manuscript and

data analysis. CWK and ZHW performed the experiments and analyzed

the data. TCH, DYC and BST confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The China Medical University Hospital's

Institutional Review Board approved the study (IRB approval number

CMUH110-REC2-178), and all participants provided written informed

consent following the Declaration of Helsinki's ethical guidelines

for medical research involving human subjects. The animal study

protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee of Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan (approval

numbers 2803 and 112065).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cottin V, Wollin L, Fischer A, Quaresma M,

Stowasser S and Harari S: Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases:

knowns and unknowns. Eur Respir Rev. 28:1801002019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Podolanczuk AJ, Thomson CC, Remy-Jardin M,

Richeldi L, Martinez FJ, Kolb M and Raghu G: Idiopathic pulmonary

fibrosis: State of the art for 2023. Eur Respir J. 61:22009572023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Matson SM and Demoruelle MK: Connective

tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheum Dis Clin

North Am. 50:423–438. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wan Q, Zhang X, Zhou D, Xie R, Cai Y,

Zhang K and Sun X: Inhaled nano-based therapeutics for pulmonary

fibrosis: Recent advances and future prospects. J

Nanobiotechnology. 21:2152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Andersson-Sjöland A, de Alba CG, Nihlberg

K, Becerril C, Ramírez R, Pardo A, Westergren-Thorsson G and Selman

M: Fibrocytes are a potential source of lung fibroblasts in

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

40:2129–2140. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Al Oweidat KS, Abdulelah AA, Toubasi AA,

Abdulelah M, Alatteili NZ and Abdulelah ZA: The clinical efficacy

and safety of nintedanib in the treatment of interstitial lung

disease among patients with systemic sclerosis: Systematic review.

Can Respir J. 2025:16825462025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Qiu J, Söderlund-Venermo M and Young NS:

Human parvoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 30:43–113. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Arvia R, Stincarelli MA, Manaresi E,

Gallinella G and Zakrzewska K: Parvovirus B19 in rheumatic

diseases. Microorganisms. 12:17082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tzang CC, Chi LY, Lee CY, Chang ZY, Luo

CA, Chen YH, Lin TA, Yu LC, Chen YR, Tzang BS and Hsu TC: Clinical

implications of human Parvovirus B19 infection on autoimmunity and

autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 147:1139602025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Janner D, Bork J, Baum M and Chinnock R:

Severe pneumonia after heart transplantation as a result of human

parvovirus B19. J Heart Lung Transplant. 13:336–338.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bousvaros A, Sundel R, Thorne GM, McIntosh

K, Cohen M, Erdman DD, Perez-Atayde A, Finkel TH and Colin AA:

Parvovirus B19-associated interstitial lung disease, hepatitis, and

myositis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 26:365–369. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Atzeni F, Alciati A, Gozza F, Masala IF,

Siragusano C and Pipitone N: Interstitial lung disease in rheumatic

diseases: an update of the 2018 review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol.

21:209–226. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nikkari S, Mertsola J, Korvenranta H,

Vainionpää R and Toivanen P: Wegener's granulomatosis and

parvovirus B19 infection. Arthritis Rheum. 37:1707–1710. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Magro CM, Crowson AN, Dawood M and Nuovo

GJ: Parvoviral infection of endothelial cells and its possible role

in vasculitis and autoimmune diseases. J Rheumatol. 29:1227–1235.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Magro CM, Nuovo G, Ferri C, Crowson AN,

Giuggioli D and Sebastiani M: Parvoviral infection of endothelial

cells and stromal fibroblasts: A possible pathogenetic role in

scleroderma. J Cutan Pathol. 31:43–50. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Magro CM, Allen J, Pope-Harman A, Waldman

WJ, Moh P, Rothrauff S and Ross P Jr: The role of microvascular

injury in the evolution of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Clin

Pathol. 119:556–567. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li X, Chen X and Zhang Y: Interstitial

pneumonia with pulmonary parvovirus B19 infection. Med Clin (Barc).

159:e17–e18. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Magro CM, Wusirika R, Frambach GE, Nuovo

GJ, Ferri C and Ross P Jr: Autoimmune-like pulmonary disease in

association with parvovirus B19: A clinical, morphologic, and

molecular study of 12 cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol.

14:208–216. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moffatt S, Tanaka N, Tada K, Nose M,

Nakamura M, Muraoka O, Hirano T and Sugamura K: A cytotoxic

nonstructural protein, NS1, of human parvovirus B19 induces

activation of interleukin-6 gene expression. J Virol. 70:8485–8491.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hsu TC, Tzang BS, Huang CN, Lee YJ, Liu

GY, Chen MC and Tsay GJ: Increased expression and secretion of

interleukin-6 in human parvovirus B19 non-structural protein (NS1)

transfected COS-7 epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 144:152–157.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Martinović Kaliterna D and Petrić M:

Biomarkers of skin and lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Expert

Rev Clin Immunol. 15:1215–1223. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dsouza NN, Alampady V, Baby K, Maity S,

Byregowda BH and Nayak Y: Thalidomide interaction with inflammation

in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Inflammopharmacology.

31:1167–1182. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Arvia R, Margheri F, Stincarelli MA,

Laurenzana A, Fibbi G, Gallinella G, Ferri C, Del Rosso M and

Zakrzewska K: Parvovirus B19 activates in vitro normal human dermal

fibroblasts: A possible implication in skin fibrosis and systemic

sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 59:3526–3532. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jeganathan N and Sathananthan M:

Connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease:

Prevalence, patterns, predictors, prognosis, and treatment. Lung.

198:735–759. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Smith RE, Strieter RM, Phan SH, Lukacs NW,

Huffnagle GB, Wilke CA, Burdick MD, Lincoln P, Evanoff H and Kunkel

SL: Production and function of murine macrophage inflammatory

protein-1 alpha in bleomycin-induced lung injury. J Immunol.

153:4704–4712. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Maher TM, Wells AU and Laurent GJ:

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Multiple causes and multiple

mechanisms? Eur Respir J. 30:835–839. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mor A, Segal Salto M, Katav A, Barashi N,

Edelshtein V, Manetti M, Levi Y, George J and Matucci-Cerinic M:

Blockade of CCL24 with a monoclonal antibody ameliorates

experimental dermal and pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis.

78:1260–1268. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chiang SR, Lin CY, Chen DY, Tsai HF, Lin

XC, Hsu TC and Tzang BS: The effects of human parvovirus VP1 unique

region in a mouse model of allergic asthma. PLoS One.

14:e02167992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ishikawa Y, Iwata S, Hanami K, Nawata A,

Zhang M, Yamagata K, Hirata S, Sakata K, Todoroki Y, Nakano K, et

al: Relevance of interferon-gamma in pathogenesis of

life-threatening rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in

patients with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther. 20:2402018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tzang CC, Lin WC, Huang ES, Kang YF, Cheng

YH, Tzang BS and Hsu TC: Interstitial lung disease biomarkers: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta.

577:1204732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hübner RH, Gitter W, El Mokhtari NE,

Mathiak M, Both M, Bolte H, Freitag-Wolf S and Bewig B:

Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological

samples. Biotechniques. 44:507–511. 514–517. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mohammed SM, Al-Saedi HFS, Mohammed AQ,

Amir AA, Radi UK, Sattar R, Ahmad I, Ramadan MF, Alshahrani MY,

Balasim HM and Alawadi A: Mechanisms of bleomycin-induced lung

fibrosis: A review of therapeutic targets and approaches. Cell

Biochem Biophys. 82:1845–1870. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Song C, He L, Zhang J, Ma H, Yuan X, Hu G,

Tao L, Zhang J and Meng J: Fluorofenidone attenuates pulmonary

inflammation and fibrosis via inhibiting the activation of NALP3

inflammasome and IL-1β/IL-1R1/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. J Cell Mol Med.

20:2064–2077. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Jegal Y, Kim DS, Shim TS, Lim CM, Do Lee

S, Koh Y, Kim WS, Kim WD, Lee JS, Travis WD, et al: Physiology is a

stronger predictor of survival than pathology in fibrotic

interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 171:639–644.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Artlett CM, Sassi-Gaha S, Hope JL,

Feghali-Bostwick CA and Katsikis PD: Mir-155 is overexpressed in

systemic sclerosis fibroblasts and is required for NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated collagen synthesis during fibrosis. Arthritis

Res Ther. 19:1442017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang WJ, Chen SJ, Zhou SC, Wu SZ and Wang

H: Inflammasomes and fibrosis. Front Immunol. 12:6431492021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Colunga Biancatelli RML, Solopov PA and

Catravas JD: The Inflammasome NLR family pyrin domain-containing

protein 3 (NLRP3) as a novel therapeutic target for idiopathic

pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 192:837–846. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hsu TC, Tsai CC, Chiu CC, Hsu JD and Tzang

BS: Exacerbating effects of human parvovirus B19 NS1 on liver

fibrosis in NZB/W F1 mice. PLoS One. 8:e683932013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Arvia R, Zakrzewska K, Giovannelli L,

Ristori S, Frediani E, Del Rosso M, Mocali A, Stincarelli MA,

Laurenzana A, Fibbi G and Margheri F: Parvovirus B19 induces

cellular senescence in human dermal fibroblasts: Putative role in

systemic sclerosis-associated fibrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford).

61:3864–3874. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Huang CL, Chen DY, Tzang CC, Lin JW, Tzang

BS and Hsu TC: Celastrol attenuates human parvovirus B19

NS1-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. Mol Med

Rep. 28:1932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Suzuki M, Ikari J, Anazawa R, Tanaka N,

Katsumata Y, Shimada A, Suzuki E and Tatsumi K: PAD4 deficiency

improves bleomycin-induced neutrophil extracellular traps and

fibrosis in mouse lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 63:806–818.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen WC, Chen NJ, Chen HP, Yu WK, Su VY,

Chen H, Wu HH and Yang KY: Nintedanib reduces neutrophil chemotaxis

via activating GRK2 in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Int J

Mol Sci. 21:47352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cheng IY, Liu CC, Lin JH, Hsu TW, Hsu JW,

Li AF, Ho WC, Hung SC and Hsu HS: Particulate matter increases the

severity of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis through

KC-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis. Int J Mol Sci. 21:2272019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Garishah FM, Rother N, Riswari SF,

Alisjahbana B, Overheul GJ, van Rij RP, van der Ven A, van der Vlag

J and de Mast Q: Neutrophil extracellular traps in dengue are

mainly generated NOX-independently. Front Immunol. 12:6291672021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

de Siqueira Santos R, Rochael NC, Mattos

TRF, Fallett E, Silva MF, Linhares-Lacerda L, de Oliveira LT, Cunha

MS, Mohana-Borges R, Gomes TA, et al: Peripheral nervous system is

injured by neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) elicited by

nonstructural (NS) protein-1 from Zika virus. FASEB J.

37:e231262023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ghazipura M, Mammen MJ, Herman DD, Hon SM,

Bissell BD, Macrea M, Kheir F, Khor YH, Knight SL, Raghu G, et al:

Nintedanib in progressive pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 19:1040–1049. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Singh P, Thampi G, Gupta K, Gangte N,

Pattnaik B, Agrawal A and Kukreti R: Clinical efficacy and safety

evaluation of drug therapies for the treatment of progressive

fibrotic-interstitial lung diseases (PF-ILDs): A network

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev Clin

Immunol. 21:1135–1170. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Srivali N, De Giacomi F, Moua T and Ryu

JH: Perioperative antifibrotic therapy for patients with idiopathic

pulmonary fibrosis undergoing lung cancer surgery: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 74:266–275. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tang Z, Yang H, Liang X, Chen J, He Q, Zhu

D and Liu Y: Animal models for connective tissue disease-associated

interstitial lung disease: Current status and future directions.

Autoimmun Rev. 24:1039192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|