Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer morbidity

and mortality. According to the results of a study published in

2024 based on global cancer statistics, there were ~2.5 million new

cases of lung cancer and >1.8 million associated deaths in 2022,

accounting for ~1/8 (12.4%) of all cancer diagnoses and 1/5 (18.7%)

of all cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). The incidence and mortality rates of

lung cancer vary among different countries and regions, with higher

rates observed among men and in countries with a higher human

development index. With the growth in human development index, it

is expected that lung cancer incidence and mortality will markedly

increase in the coming decades (2).

Recurrence and metastasis are the leading causes of

poor prognosis and death in lung cancer. Although a number of

studies have explored cancer metastasis, the underlying mechanism

of action has not yet been fully elucidated (3). Homeobox (HOX) genes are a superfamily

of transcription factors containing homeodomains that control cell

proliferation, differentiation and morphological changes during the

early stages of embryonic development (4). The dysregulation of HOX genes

enhances cell survival and proliferation, and inhibits cell

differentiation. Previous studies have revealed that numerous HOX

genes are abnormally expressed in various types of human tumor,

such as bladder, breast, lung, liver, colorectal, prostate and

ovarian cancer (5–8).

As a recently identified HOX transcription factor,

the intestine-specific HOX (ISX) gene is specifically expressed in

the adult and fetal intestine (9).

ISX is a proto-oncogene that is upregulated in hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) through the induction of proinflammatory cellular

factors. Notably, it can bind directly to the cyclin D1 promoter in

the nucleus, thereby regulating the proliferation of tumor cells,

and it is also an important activator of proliferation and

tumorigenesis in vivo (10). In addition, ISX is highly expressed

in lung cancer cells and patient tissue; its upregulation can

accelerate the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells and

higher levels of ISX expression in lung cancer tissues indicate

more obvious lymph node metastasis (11). Previous studies have reported that

ISX expression can induce an epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) response, promoting tumor cell migration and invasiveness

(10,11); however, the underlying mechanisms

are not yet fully understood. Therefore, it is important to explore

the potential mechanism underlying the regulation of metastasis for

the prevention and treatment of lung cancer.

The present study aimed to establish a cell model

with enhanced migration and invasion properties by

lentivirus-mediated overexpression of the ISX oncogene, which was

assessed using cellular and molecular biology technologies. The

current study examined how ISX induces and participates in the

development of the tumor microenvironment, thereby promoting tumor

cell migration and invasion and progression. Transcriptomics

analysis was employed to further investigate potential ISX-promoted

lung cancer migration biomarkers and molecular mechanisms.

Furthermore, the therapeutic efficacy of currently available lung

cancer drugs was verified in a cell model with stable

overexpression of ISX. The study aimed to identify novel options to

treat lung cancer, and to provide a scientific basis for its

prevention and treatment, which may reduce the cost to patients,

their families and society.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

A549 human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells

(cat. no. ZQ003) were purchased from Shanghai Zhongqiao Xinzhou

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml) (all from Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The

medium was changed every 3 days. When the cells reached the

logarithmic growth phase, they were passaged and used for

subsequent experiments.

Lentiviral infection

GFP-labeled lentiviral vectors overexpressing ISX

[Lv-ISX (Ubc-NM_001303508.2-3FLAG-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin; Gene:

ISX Human, gene ID: 91464; transcribed transcript: NM_001303508.2)]

and a negative control lentiviral vector

(Ubc-MCS-3FLAG-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin) were obtained from

Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. A549 cells in the logarithmic growth

phase were harvested, trypsinized and counted. The cell density was

adjusted to 2×105 cells/well for inoculation into 6-well

plates, 2 ml complete medium was added, and the plates were

incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 overnight to allow the

cells to attach to the wall and reach 30–50% confluence. First, a

preliminary experiment involving viruses with different

multiplicity of infection (MOI) gradients was conducted to

determine the minimum effective infection dose (MOI, 10). Based on

the pre-experiment result, 1 ml medium containing the virus at an

MOI of 10 was added to each well. After 24 h of incubation, the

medium was removed and fresh medium was added. The transfection

efficiency was observed under a fluorescence microscope after 48 h.

If the proportion of GFP-labeled cells reaches >80%, the cells

were harvested for further validation by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and

western blotting. The validated cells were either screened in a

cell culture medium supplemented with 1 µg/ml puromycin for

continued culture or cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen for use in

subsequent experiments.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from the cells using

RIPA buffer (cat. no. G2002; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the protein

concentration was measured using a BCA assay. Protein samples were

subjected to SDS-PAGE on 12% gels at a loading volume of 10 µl/well

(total protein, 30 µg) and then transferred to PVDF membranes. The

membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 5%

non-fat milk/TBS-0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and were then washed five

times with TBST. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated

overnight at 4°C with anti-ISX (1:100; cat. No. sc-398934; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-β-actin (1:500; cat. No.

sc-58673; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) antibodies, followed by

incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody

(1:2,000; cat. No. 7076; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h

at room temperature. Finally, the membranes were incubated with ECL

solution (cat. no. G2014; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.),

and the images were exposed and developed. Protein expression was

analyzed semi-quantitatively using ImageJ2 (Fiji; National

Institutes of Health).

RT-qPCR analysis

RT-qPCR detection was performed using the RNA

extracted from A549 cells with or without ISX overexpression, as

well as from A549 cells overexpressing ISX treated with 25 µg/ml

gefitinib (Iressa®; cat. no. HY-50895; MedChemExpress)

for 48 h in a cell incubator at 37°C. Total RNA was extracted from

these cells using the EZ-10 DNA-free RNA Mini-Preps Kit (Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A

total of 1 µg RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using a

PrimeScript™ RT Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, total RNA, 5X

PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time) and RNase Free

dH2O were used to form a reaction system, which was

incubated at 42°C for 15 min, followed by incubation at 85°C for 5

sec. Subsequently, qPCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex

Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The reaction system included 2 µl cDNA, 1

µl primer, 12.5 µl 2X TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus)

and 8.5 µl ddH2O, and the thermocycling conditions used

were as follows: 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for

5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Melt curve analysis was performed at the

end of amplification by increasing the temperature from 65 to 95°C

in 0.5°C increments every 5 sec to confirm the specificity of the

amplification products. The primer sequences used were as follows:

GAPDH, forward (F) 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′, reverse (R)

5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′; ISX, F 5′-CCTGCTCTCTGCAGGGGT-3′, R

5′-CTGTCCATATCACTCCTCCTGGC-3′; TWIST, F 5′-GGAGTCCGCAGTCTTACGAG-3′,

R 5′-TCTGGAGGACCTGGTAGAGG-3′; Slug, F

5′-ACACATTACCTTGTGTTTGCAAGATCT-3′, R

5′-TGTCTGCAAATGCTCTGTTGCAGTG-3′; vimentin (VIM), F

5′-GAGAACTTTGCCGTTGAAGC-3′, R 5′-GCTTCCTGTAGGTGGCAATC-3′; zinc

finger E-box binding HOX 1 (ZEB1), F

5′-GAAAATGAGCAAAACCATGATCCTA-3′, R 5′-CAGGTGCCTCAGGAAAAATGA-3′; and

E-cadherin, F 5′-AGAACGCATTGCCACATACACTC-3′, R

5′-CATTCTGATCGGTTACCGTGATC-3′. The relative expression levels of

the genes were examined using the 2−ΔΔCq method with

GAPDH as the reference gene (12).

Transcriptome sequencing

Three replicates of A549 cells with lentivirus

infection-mediated ISX overexpression and three replicates of A549

cells infected with the negative control lentiviral vector were

used for transcriptome sequencing. These six samples were sent to

Beijing Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. for transcriptome sequencing

and data analysis. Briefly, RNA was extracted using the TRNzol

universal reagent; cat. no. 4992730; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.)

method, and the total amounts and integrity of extracted RNA were

assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit on the Bioanalyzer 2100

system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Upon successful detection,

library construction was performed using the NEB Next

Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, Inc.). After the

construction of the library, the library was quantified using the

Qubit2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), then diluted

to 1.5 ng/µl, and the insert size of the library was detected using

the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. RT-qPCR (Touch q-PCR system CFX96;

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was used to accurately quantify the

effective concentration of the library (the loading concentration

of the final library was >2 nM) to ensure the quality of the

library. RT-qPCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex

Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Inc.), and the thermocycling

conditions used were as follows: 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40

cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Subsequently, the

libraries were pooled according to the required effective

concentration and target downstream data volume for Illumina

sequencing [Illumina NovaSeq X plus; Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3

(cat. no. MS-102-3003); both from Illumina, Inc.], and 150 bp

paired-end reads were generated. The image data of the sequenced

fragments measured by the high-throughput sequencer were converted

into sequence data (reads) by CASAVA base recognition (version 1.6;

Illumina, Inc.). The raw data were then filtered by removing reads

containing adapters or ‘N’ (which indicates that base information

could not be determined), as well as low-quality reads (reads with

Qphred ≤20 bases accounting for >50% of the entire read length).

Subsequently, the Q20 (≥90%) and Q30 (≥85%) values, and the GC

content (45–55%) were calculated for the clean and filtered data,

and it was ensured that all subsequent analyses were of a high

quality and based on clean data. The HISAT2 software (v2.0.5;

http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/) was then used

to rapidly and accurately align the clean reads with the reference

genome to obtain the localization information of the reads on the

reference genome. Intergroup differences and intra-group sample

replication were further evaluated through Pearson's correlation

analysis and principal component analysis.

The Venn diagram was implemented using the

VennDiagram R package (version 1.7.3; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/VennDiagram)

and the gene expression heatmaps were generated using the ggplot2

(version 3.5.1; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html)

and pheatmap R packages (version 1.0.2; http://cran.r-project.org/package=pheatmap).

After quantifying the gene expression levels, differential

expression between the two comparison groups was analyzed using

DESeq2 software (version 1.20.0; http://packages.renjin.org/package/org.renjin.bioconductor/DESeq2).

The Benjamini-Hochberg method was then used to adjust the obtained

P-value (Padj) to control the false discovery rate. The threshold

for significant differential expression was set to Padj ≤0.05 and

|log2 (fold change)|≥1. The names of each differentially expressed

gene (DEG) and the word ‘cancer’ were used as key words when

searching Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/) to explore the

association between these genes and cancer. The retrieved

literature, including research articles and review papers, was

further screened based on titles and abstracts, and finally

confirmed through the content of the documents. The clusterProfiler

(version 3.8.1; http://github.com/YuLab-SMU/clusterProfiler) software

was then used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses on the DEGs. A Padj

value of <0.05 was considered significant. The STRING database

(v11.5; http://string-db.org/) was further used

to construct the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, and the

top five central genes were identified using the Degree algorithm

in the CytoHubba plugin of Cytoscape software (version 0.1;

http://apps.cytoscape.org/).

Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8) assay

The active ingredients of the following established

lung cancer drugs were purchased from MedChemExpress: Bevacizumab

(Avastin®), erlotinib (Tarceva®), cetuximab

(Erbitux®) and gefitinib. Initially, their effects on

the viability of uninfected A549 cells were assessed. Specifically,

A549 cells with or without ISX overexpression in the logarithmic

growth phase were inoculated into 96-well plates at a density of

3,000 cells/well and were cultured for 24 h. Cells not

overexpressing ISX were then treated with bevacizumab, erlotinib,

cetuximab and gefitinib (100 µl) at concentrations of 0, 5, 25, 30,

35, 40, 45 and 50 µg/ml, and were cultured in the incubator for 48

h. In addition, cells overexpressing ISX were treated with

gefitinib under the same conditions. After 48 h, 10 µl CCK8 reagent

(cat. no. CK04; Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) was added to each well.

Several wells with only the culture medium added and no cells were

used as blank controls. After incubation at 37°C for 2–4 h, the

optical density (OD) at 450 nm was measured using an ultraviolet

spectrophotometer. The cell viability was calculated using the

following formula: Cell viability (%)=[(experimental group OD-blank

group OD)/(control group OD-blank group OD)] ×100.

Wound healing assay

Cells overexpressing ISX in the logarithmic growth

phase were collected, digested with trypsin into a single-cell

suspension and inoculated at a density of 1×105

cells/well into a 6-well culture plate to ensure that the fusion

rate of the inoculated cells reached >90% overnight.

Subsequently, a sterile pipette tip was used to make a straight

scratch on the cell monolayer, followed by a wash with

phosphate-buffered saline to remove the exfoliated cells. An

initial image of the scratch was captured under a fluorescence

microscope and recorded as 0 h. Subsequently, the medium was

replaced with low-serum (1% FBS) medium with or without gefitinib.

After culturing for a further 48 h, images were captured from the

same position as at 0 h to record the closure of the scratches.

Images of the scratch area were analyzed using ImageJ software and

the scar healing analysis plug-in (MRI_Wound_Healing_Tool;

http://www.mri.cnrs.fr/en/data-analysis/software-and-tools/271-mri-tools/409-wound-healing-tool.html)

was used to measure cell migration. Migration rate (%)=(48 h

scratch area-0 h scratch area)/0 h scratch area ×100.

Cell invasion assay

A Transwell invasion assay was conducted using

Transwell cell chambers (24-well plates; pore size, 8 µm) that were

coated with Matrigel. Briefly, Matrigel was diluted in PBS at a 1:8

ratio under 4°C conditions (on ice). Subsequently, 50 µl was added

evenly to the upper chamber surface of the Transwell chamber and

incubated at 37°C for 4 h to allow the Matrigel to polymerize into

a gel film. A549 cells overexpressing ISX in the logarithmic growth

phase were assessed. Briefly, after digestion, cells were

resuspended in serum-free medium, and 250 µl cells

(8×104/well) were transferred to the upper chamber of

the Transwell. Different concentrations of gefitinib diluted in

medium containing 10% FBS (0, 25 and 50 µg/ml) were added to the

lower chamber. The cells were incubated for 48 h to allow the cells

to penetrate the Matrigel and to migrate into the lower chamber.

Subsequently, the non-invasive cells were removed from the upper

chamber with a cotton swab, and the lower chamber membrane was

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min followed by staining with

0.2% crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature. Observations

were made and images were captured under a light microscope.

Finally, the crystal violet was completely eluted by thoroughly

shaking the solution in 3% acetic acid at room temperature for 5

min. The eluate was then used to measure the OD value at 570 nm

using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n≥3) of

three independent experiments. The results were statistically

analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (Dotmatics). Statistical

differences between the two groups were analyzed using an unpaired

Student's t-test. Statistical differences among multiple groups

were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons

post hoc test to identify the groups with significant differences.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Overexpression of the carcinogenic

factor ISX promotes the expression of EMT-related genes

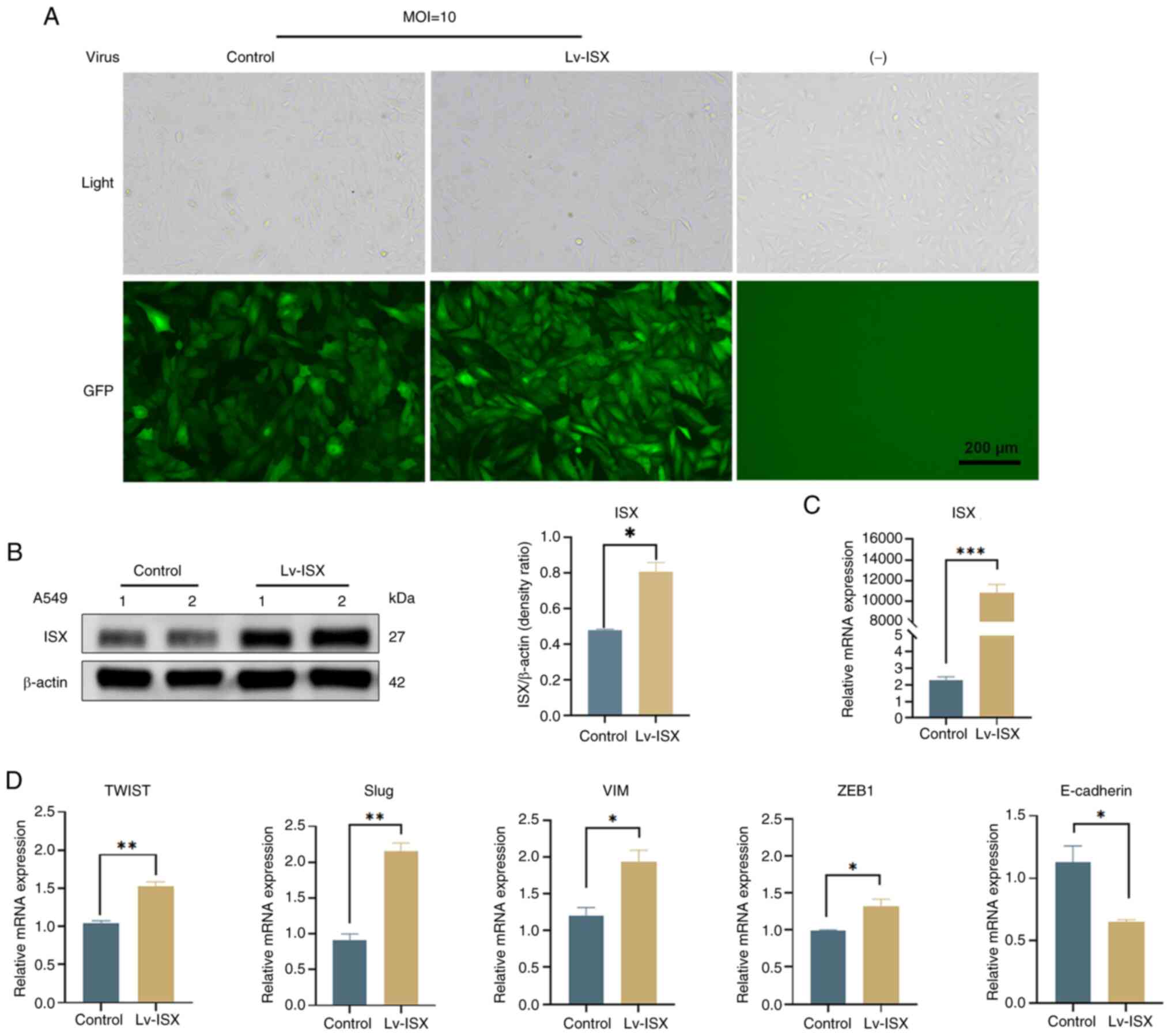

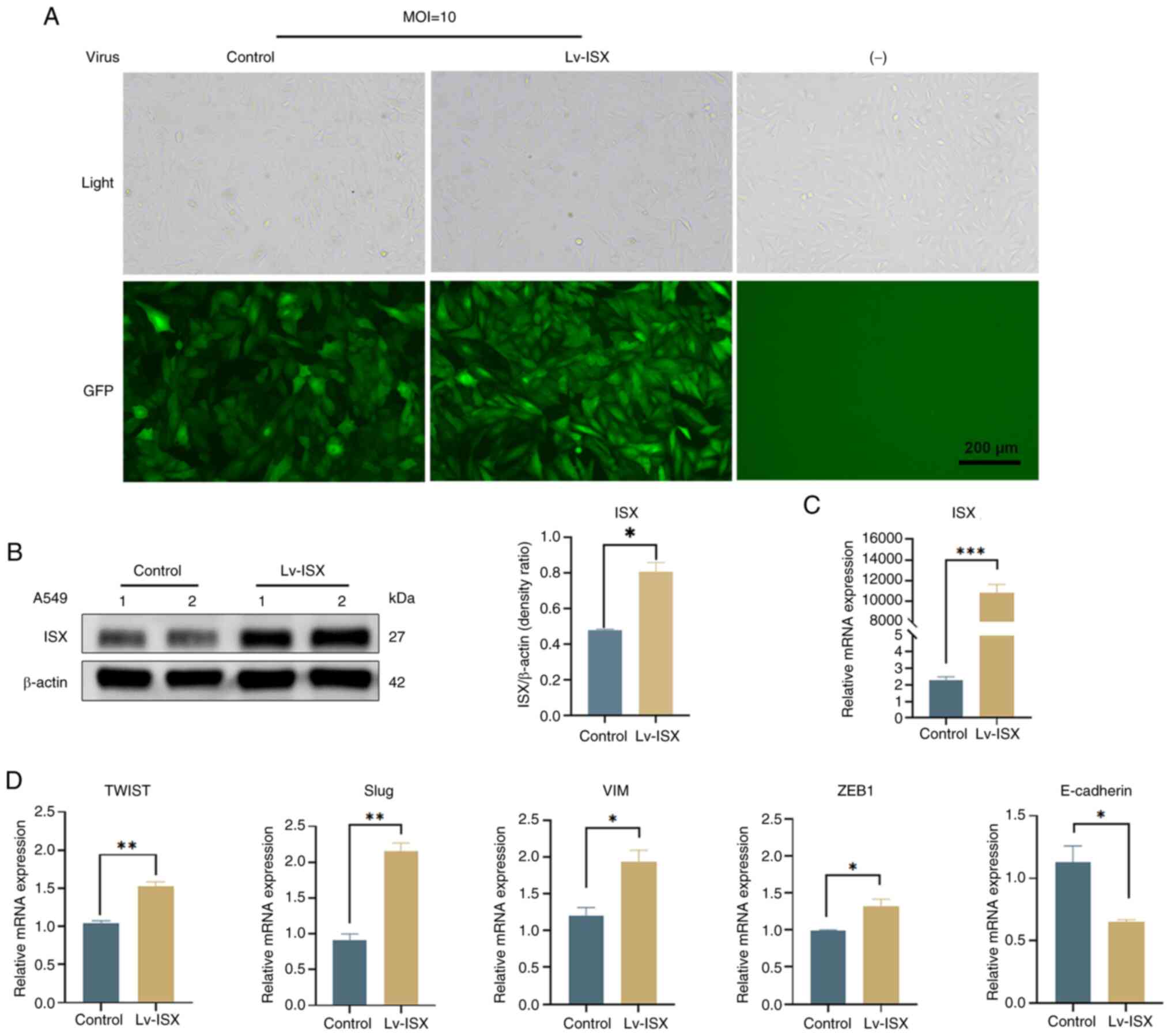

To explore the potential role of the oncogene ISX in

regulating downstream genes associated with EMT in lung cancer

metastasis and its molecular mechanisms, ISX overexpression was

induced in A549 lung cancer cells using lentiviral infection and

the expression of EMT markers was verified. The MOI and optimal

conditions for lentiviral infection of cells were first determined

through preliminary experimentation, the results of which are shown

in Fig. 1A. Using an MOI of 10

resulted in healthy cells with high fluorescence expression and an

infection efficiency of >80%. Subsequently, the mRNA and protein

expression levels of ISX were verified by RT-qPCR and western

blotting. The results showed that both the mRNA and protein

expression levels of ISX were significantly increased after

lentiviral infection (Fig. 1B and

C). Subsequent experiments were conducted using A549 cells

overexpressing ISX. The effects of ISX overexpression on the

expression of EMT markers were further validated (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the findings of

previous reports (10,11), ISX overexpression significantly

increased the expression levels of the EMT markers TWIST, Slug, VIM

and ZEB1, while downregulating the expression of the epithelial

cell marker E-cadherin.

| Figure 1.Overexpression of the oncogenic

factor ISX promotes the expression of EMT-related genes. (A) ISX

overexpression in A549 cells was mediated by Lv infection and

observed by GFP fluorescence intensity. Scale bar, 200 µm. (B) ISX

protein expression levels were verified by western blot analysis.

(C) ISX mRNA expression levels were verified by RT-qPCR detection.

(D) Genes related to EMT (TWIST, Slug, VIM and ZEB1) and epithelial

cells (E-cadherin) were detected by RT-qPCR. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition;

ISX, intestine-specific homeobox; Lv, lentivirus; MOI, multiplicity

of infection; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction; VIM, vimentin; ZEB1, zinc finger E-box

binding homeobox 1. |

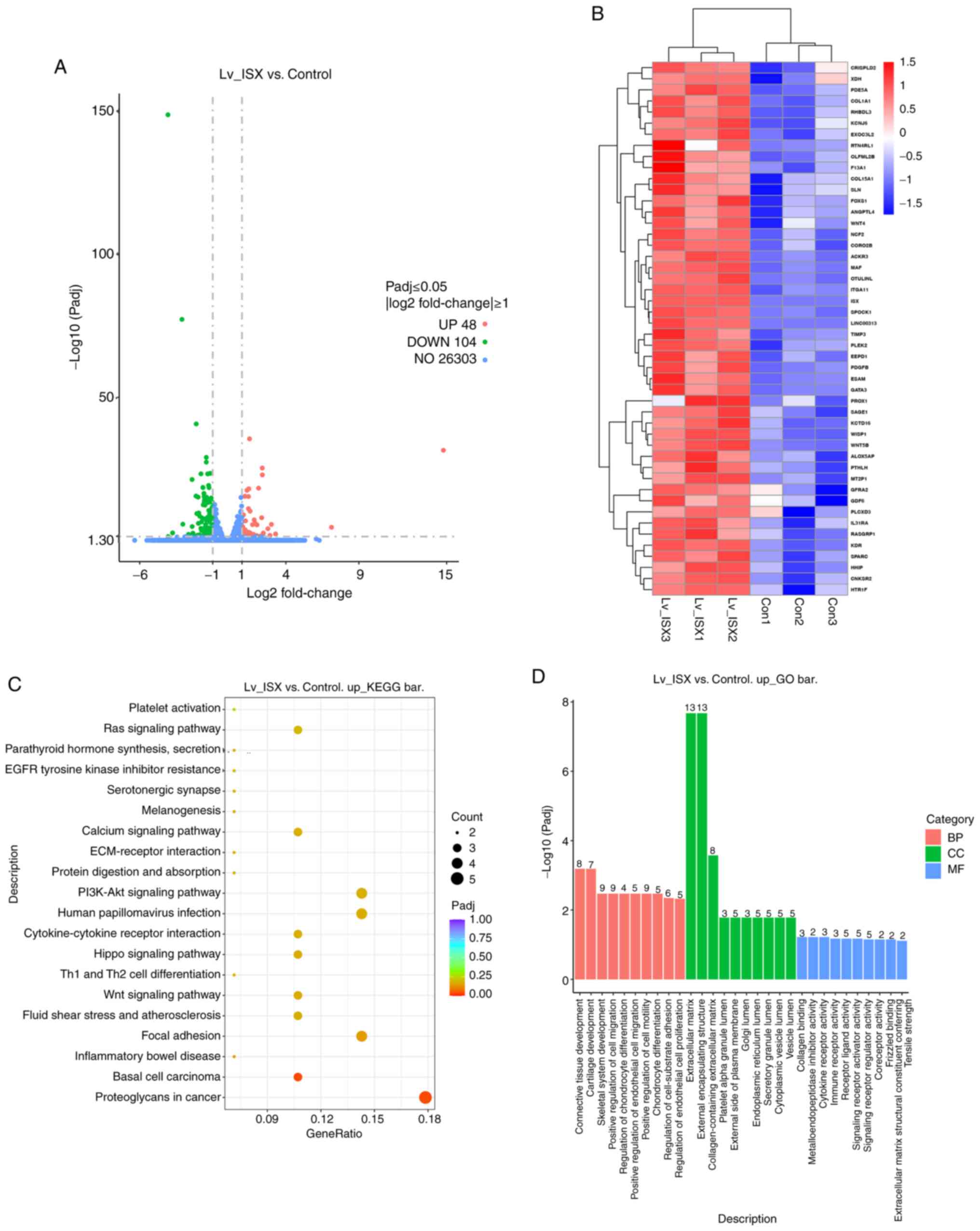

ISX overexpression significantly

alters the gene expression profile of human lung cancer cells

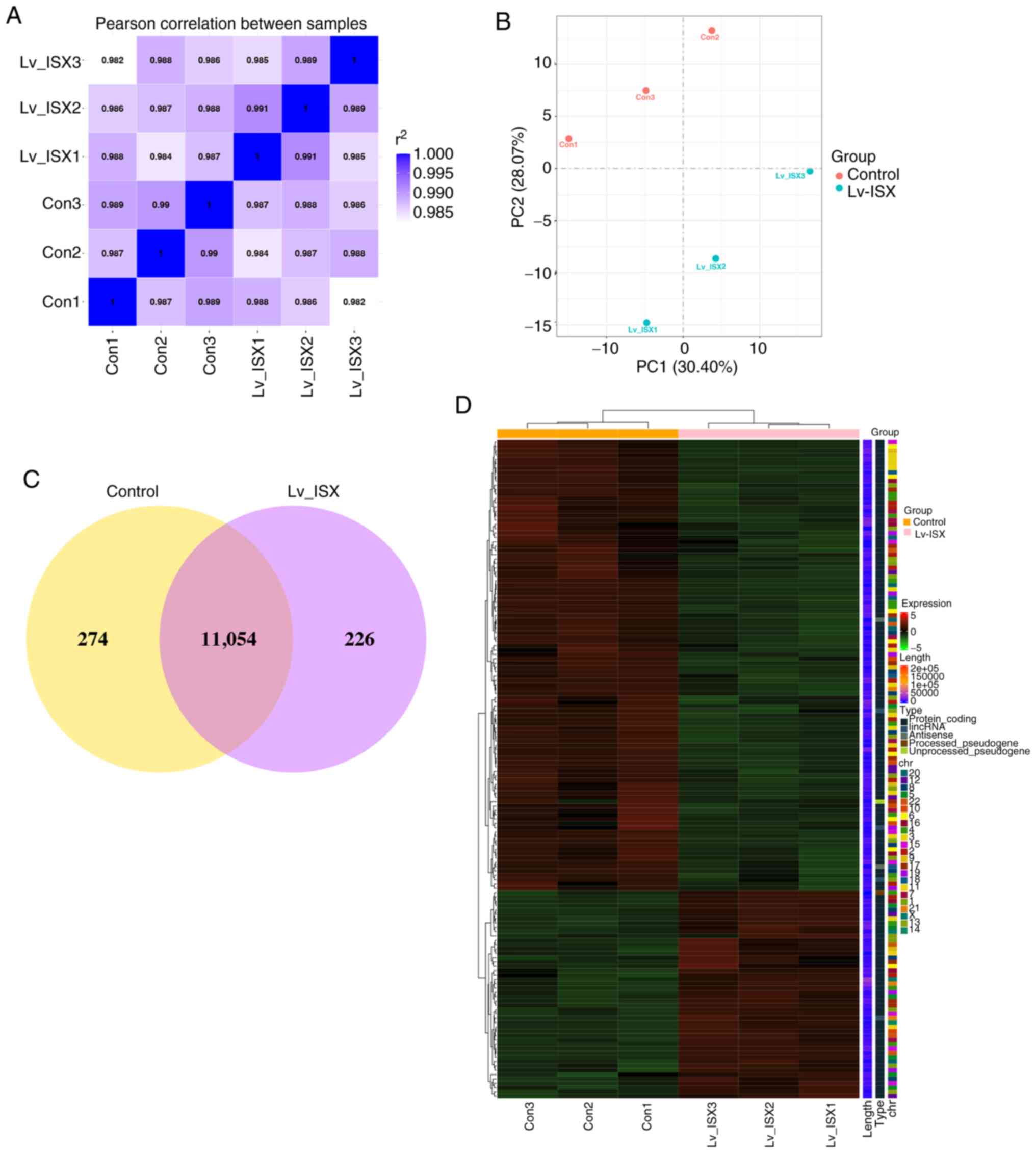

The present study aimed to investigate the

mechanisms related to the promotion of tumor cell metastasis and

progression by the oncogenic factor ISX, and to discover their

possible underlying mechanisms and biomarkers. Briefly,

transcriptome sequencing was performed on A549 cells overexpressing

ISX via lentiviral infection and on A549 cells infected with the

control lentivirus vector (n=3 samples/group). The sequencing data

were uploaded to the Sequence Read Archive of the National Center

for Biotechnology Information under the accession number

PRJNA1282884.

Table SI

summarizes the sequencing metrics and quality check results for the

raw RNA sequencing reads. After excluding reads containing

aptamers, one N base or low quality, 46,016,622, 39,526,880, and

44,502,284 clean reads were obtained in the control groups (Con1,

Con2, and Con3), whereas 45,903,940, 44,323,396, and 43,279,598

clean reads were obtained in the ISX overexpression groups

(Lv_ISX1, Lv_ISX2, and Lv_ISX3). The sequencing error rate for each

library was 0.01%, and >95% of the clean read data had

Phred-like quality scores at the Q30 level (error probability of

0.001), indicating high sequencing quality. The total mapping rate

of the reference genome ranged between 94.64 and 95.72%, while a

smaller percentage (<5%) of the reference genome's multiple loci

were mapped (Table SII, Multi

map), further verifying the reliability of the sequencing quality.

Pearson's correlation analysis and principal component analysis

were performed on the two groups of samples to investigate their

similarities and differences. The results showed that samples

within the same group were highly similar, whereas samples in

different groups were dissimilar (Fig.

2A and B). The Venn diagram (Fig.

2C) showed a total of 11,054 genes in both groups. The

clustering heatmap further confirmed the reproducibility of the

samples, and the global gene expression patterns were revealed to

be significantly different between the treatment and control groups

(Fig. 2D).

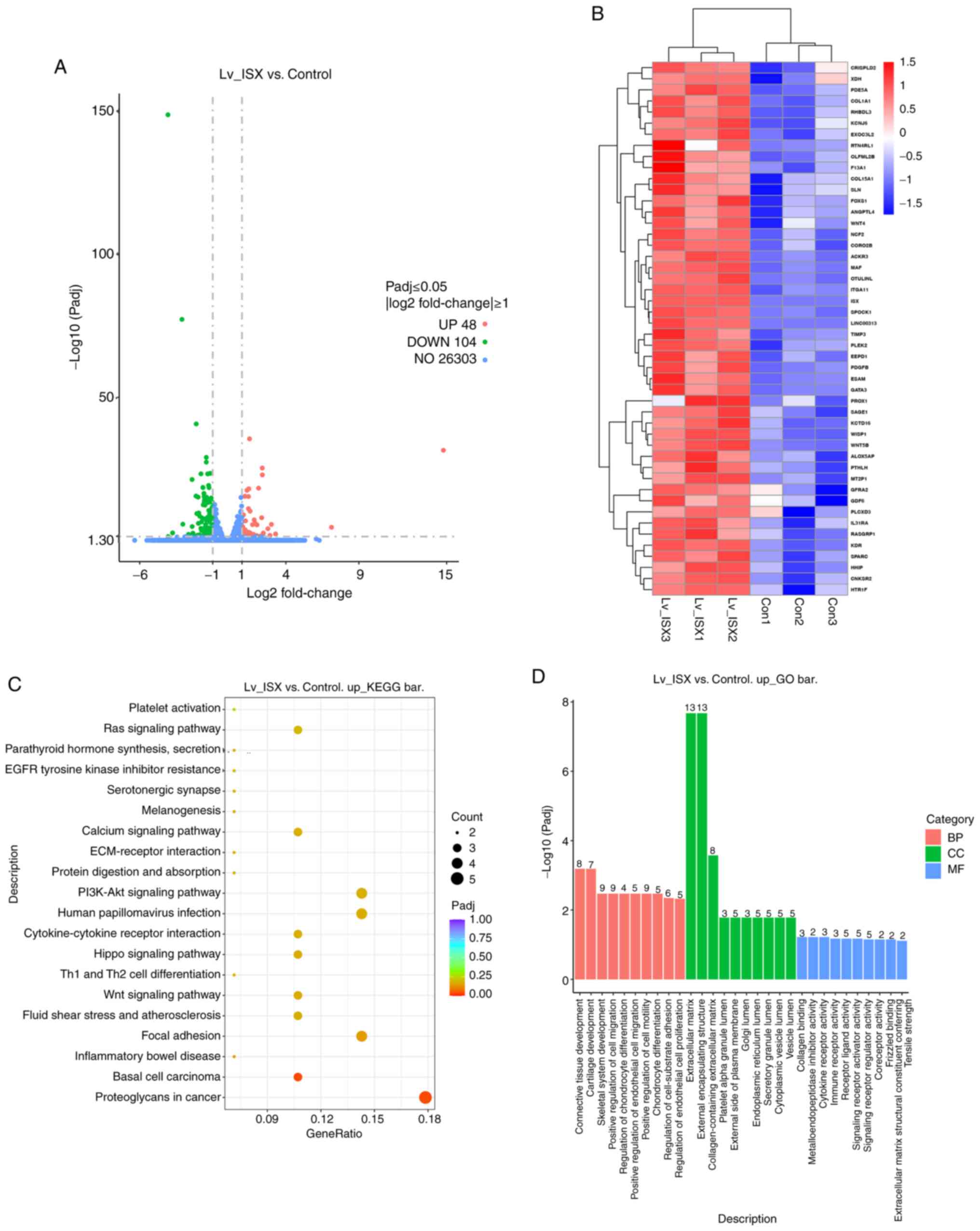

Gene expression analysis was performed on the

transcripts to further characterize the DEGs in the ISX

overexpression group compared with in the control group. A total of

152 DEGs were identified, 48 of which were upregulated and 104 of

which were downregulated (Fig.

3A). The heatmap in Fig. 3B

and Table SIII show the

upregulated DEGs in the ISX overexpression group. The results of

the literature review indicated that most of the DEGs were

associated with tumor metastasis. Subsequently, the biological

functions and signaling pathways of these genes were

comprehensively analyzed by GO functional annotation and KEGG

pathway analyses.

| Figure 3.Screening of DEGS in cells with ISX

overexpression, and enrichment analyses of biological functions and

signaling pathways. (A) Volcano plot showing the number of genes

with significant differences in expression levels between the ISX

overexpression group and the control group, as well as the specific

distribution of DEGs. (B) Heatmap showing the expression of DEGs

that were upregulated in the ISX overexpression groups. (C) KEGG

analysis showing the top 20 enriched pathways of the DEGs that were

upregulated in the ISX overexpression group compared with the

control group. Bubble size represents the number of genes, color

shade represents Padj, and the enrichment ratio on the y-axis

represents the number of genes/total number of genes. (D) GO term

enrichment analysis of the DEGs that were upregulated in the ISX

overexpression group compared with the control group. The numbers

on the columns indicate the number of enriched genes in that

category. BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; Con,

control; DEG, differentially expressed gene; GO, Gene Ontology;

ISX, intestine-specific homeobox; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes; Lv, lentivirus; MF, molecular function. |

KEGG pathway analysis revealed the primary pathways

enriched in the upregulated DEGs, including ‘proteoglycans in

cancer’, ‘basal cell carcinoma’, ‘focal adhesion’, ‘Wnt signaling

pathway’, ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’, ‘PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway’, ‘ECM-receptor interaction’, ‘calcium signaling

pathway’ and ‘Ras signaling pathway’ (Fig. 3C). Further functional enrichment

analyses revealed that these interacting genes were primarily

involved in the following biological processes: ‘Connective tissue

development’, ‘cartilage development’, ‘positive regulation of cell

migration’, ‘regulation of chondrocyte differentiation’, ‘positive

regulation of endothelial cell migration’ and ‘positive regulation

of cell motility’. Enriched cellular components included

‘extracellular matrix’, ‘endoplasmic reticulum lumen’ and

‘collagen-containing extracellular matrix’. At the molecular

function level, these genes were associated with ‘collagen

binding’, ‘metalloendopeptidase inhibitor activity’, ‘cytokine

receptor activity’, ‘immune receptor activity’, ‘receptor ligand

activity’ and ‘extracellular matrix structural constituent

conferring tensile strength’ (Fig.

3D). These results suggested that the overexpression of ISX may

contribute to the processes of invasion, migration and cartilage

formation in lung cancer cells.

ISX may promote lung cancer migration

and invasion by upregulating type I collagen α1 chain (COL1A1)

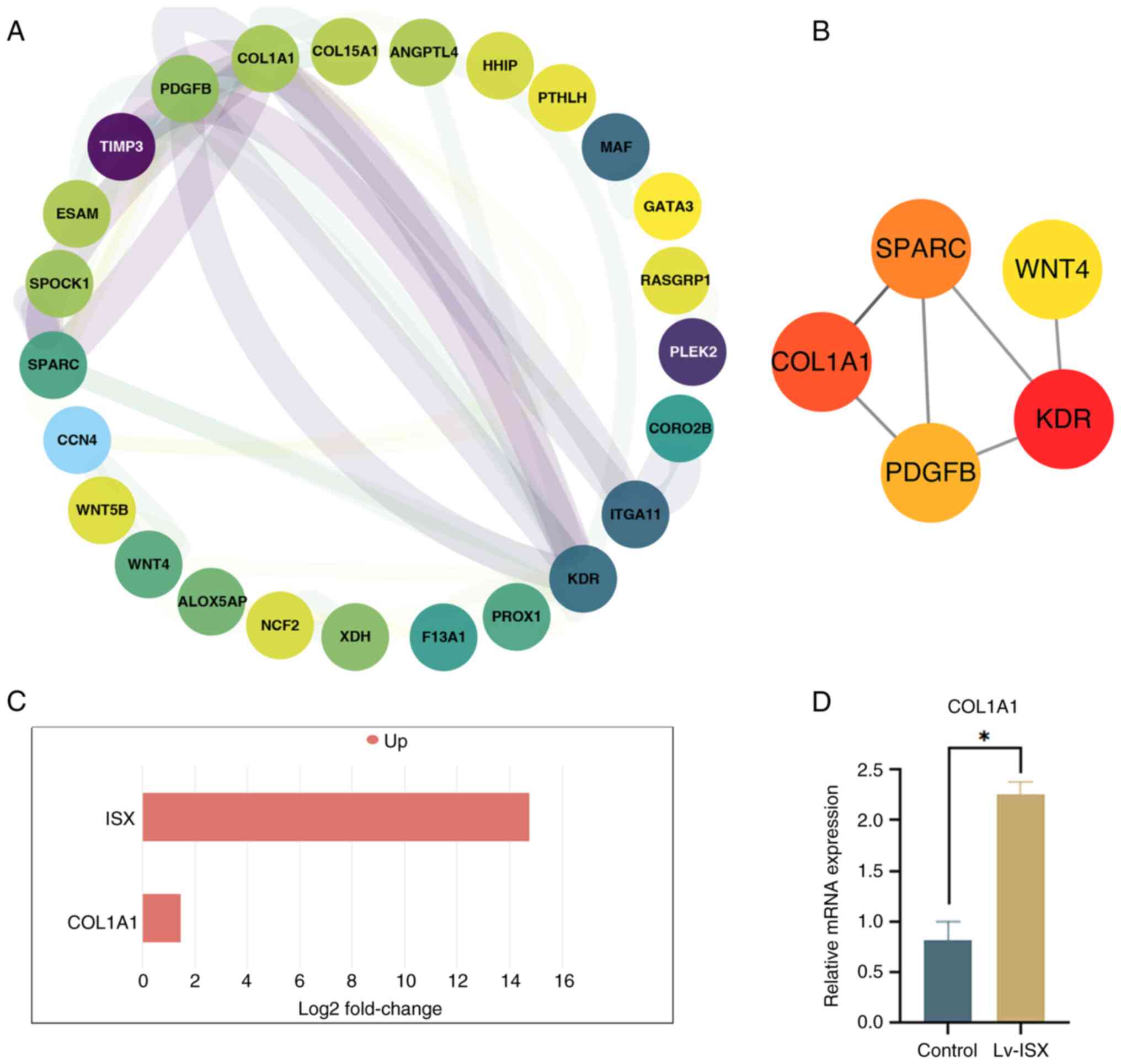

To further investigate the possible mechanism by

which ISX overexpression promotes tumor cell migration and

invasion, a PPI network was constructed for the upregulated DEGs by

using the software program Cytoscape (Fig. 4A). Based on the degree-based

topological algorithm, the top five core genes (KDR, COL1A1, SPARC,

PDGFB and WNT4), which showed the most significant interactions,

were identified using the Cytoscape CytoHubba application (Fig. 4B). Notably, COL1A1 was recognized

as one of the hub genes; COL1A1 is a key protein encoding fibrous

collagen, the main component of type I collagen, and it server a

crucial role in maintaining cell morphology, intercellular

connections, tissue structure stability and extracellular matrix

(ECM) homeostasis (13). Notably,

COL1A1 dysfunction has been shown to be associated with various

diseases, including fibrosis, osteogenesis imperfecta and

osteoporosis, which are bone diseases caused by COL1A1 deficiency

(14). In recent years, multiple

reports have shown that COL1A1 is upregulated in various tumor

tissues and cells, prompting researchers to pay increasing

attention to its role in cancer (15–18).

The transcriptome sequencing results showed that ISX

overexpression led to the upregulated expression of COL1A1

(Fig. 4C), which was further

verified by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4D).

Studies have shown that the abnormal upregulation of COL1A1 in

cancer is closely related to regulating tumor cell proliferation,

differentiation and migration (15). These findings provide important

insights into the specific mechanisms by which COL1A1 may be

involved in ISX-induced regulation of tumor migration and invasion.

Its potential mechanism awaits further systematic analysis in

future research.

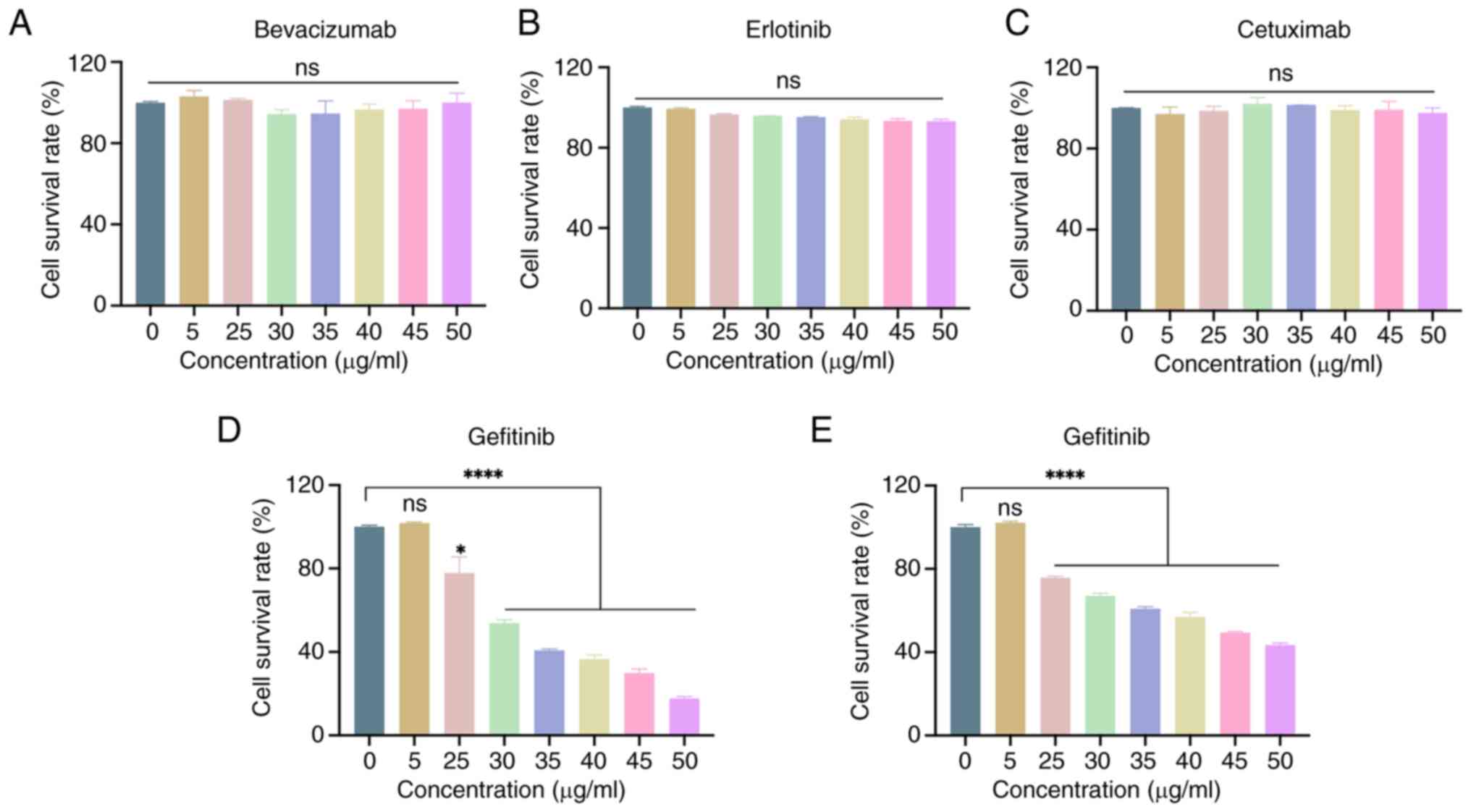

Screening of mature tumor-targeting

drugs that may be used to treat ISX-induced lung cancer

Metastasis of tumor cells is the primary cause of a

poor prognosis for tumors. Notably, the upregulation of ISX may

accelerate the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells;

therefore, four mature tumor-targeting drugs were used to treat the

ISX-induced lung cancer cell model, with the aim of identifying

better therapeutic drugs that can resist tumor metastasis. The

drugs used in the current study included Iressa (gefitinib),

Tarceva (erlotinib) and Avastin (bevacizumab), which are already

used to treat lung cancer. Although Erbitux (cetuximab) is approved

for treating colorectal cancer and head and neck cancer, as an

anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody, it has been extensively studied in

combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced NSCLC

(19,20). The current study first evaluated

the effects of these treatments on the viability of un-infected

A549 cells. As shown in Fig. 5A-D,

only gefitinib affected A549 cell viability within the tested

concentration range (0–50 µg/ml). The concentration range

significantly affected A549 cell viability in a dose-dependent

manner, starting at 25 µg/ml. Therefore, gefitinib was subsequently

used for the treatment of cells stably overexpressing ISX. The

results showed that gefitinib was also effective in reducing the

viability of A549 cells stably overexpressing ISX at concentrations

of ≥25 µg/ml (Fig. 5E), although

the reduction in cell viability was not as high as that in

non-infected A549 cells.

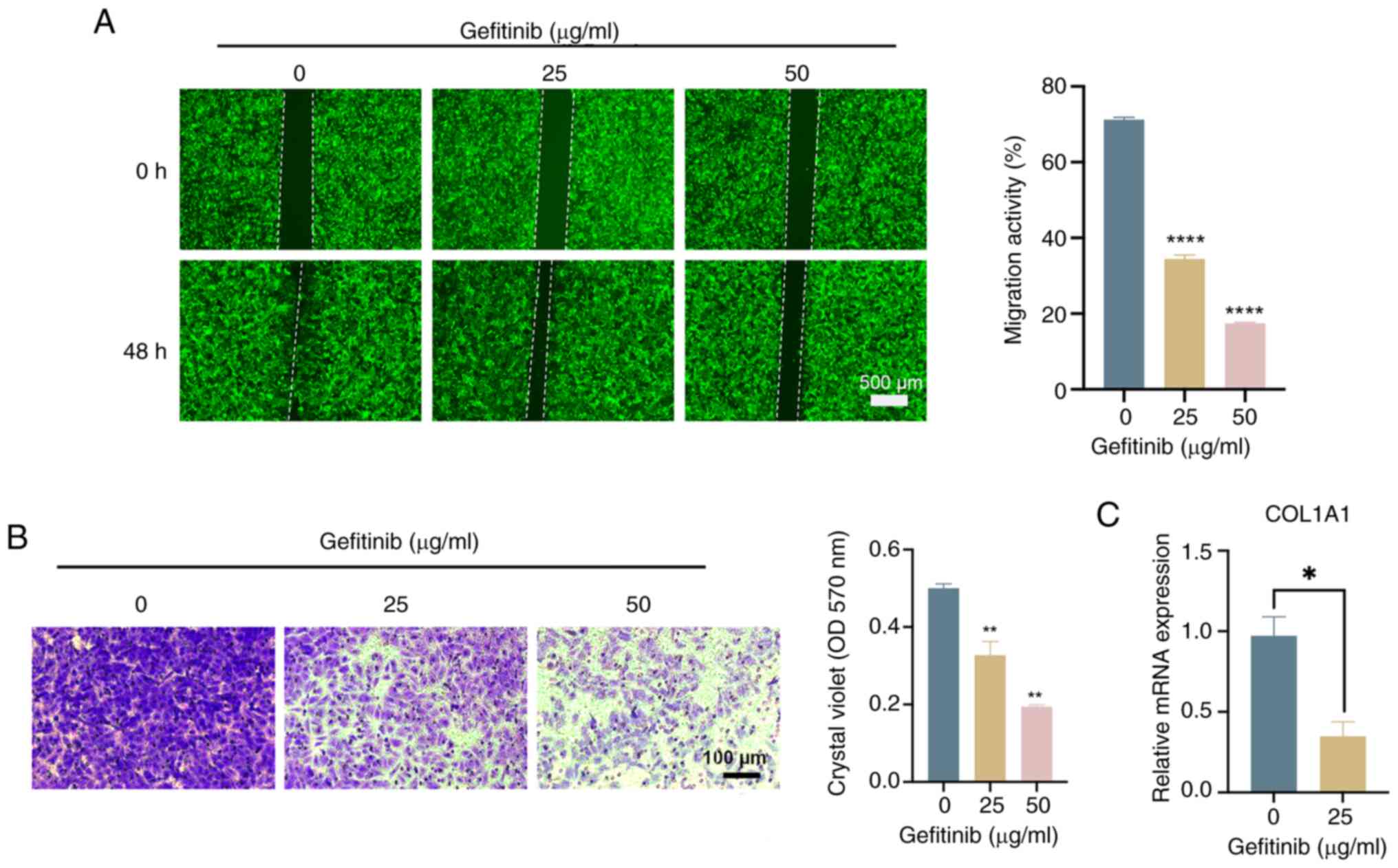

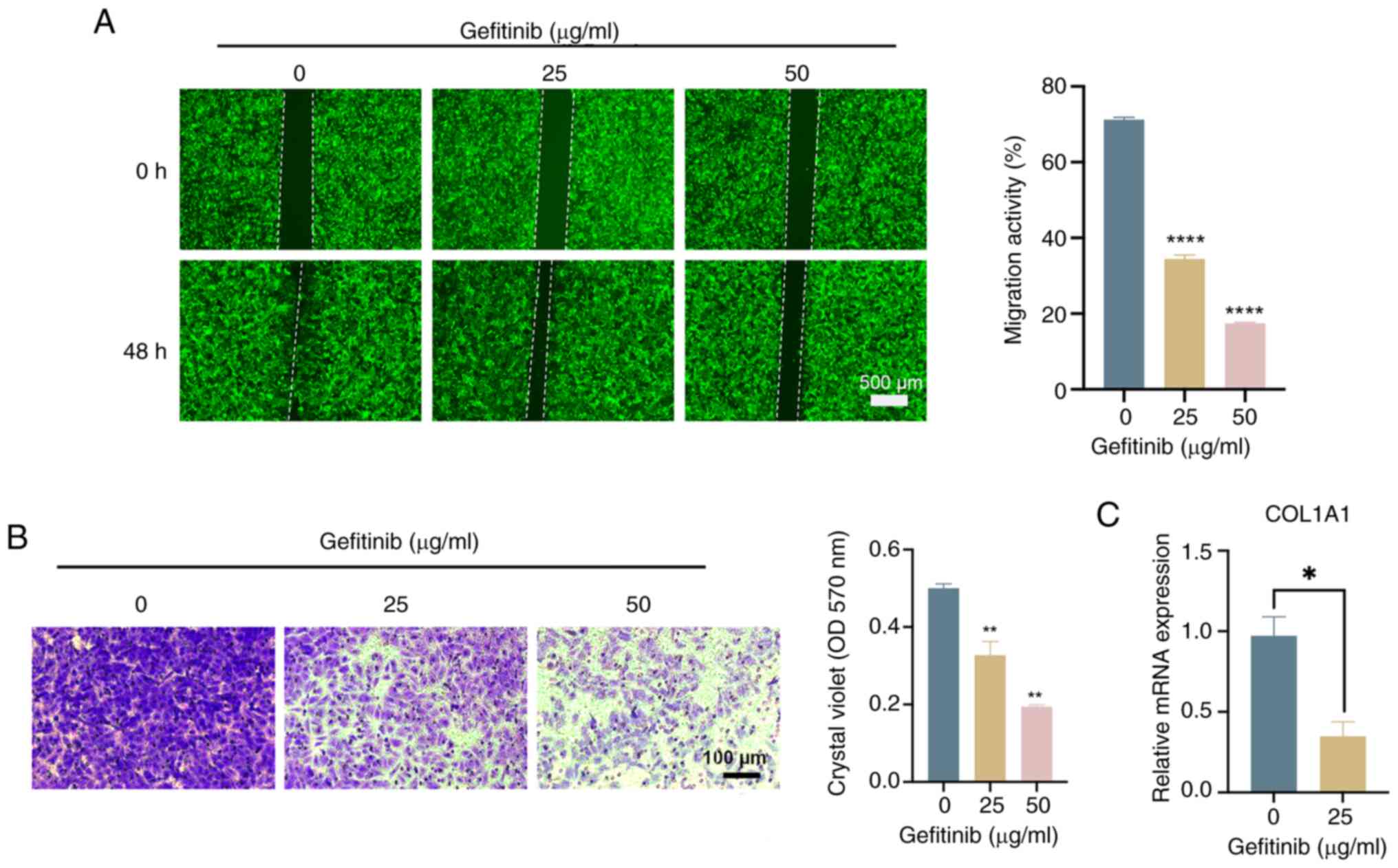

The effects of gefitinib (the active ingredient of

Iressa®) on the migration and invasion characteristics

of lung cancer cells with stable overexpression of ISX were then

evaluated through wound healing and Transwell assays. The results,

as shown in Fig. 6A and B,

indicated that gefitinib can significantly inhibit the migration

and invasion of ISX-overexpressing A549 lung cancer cells in a

concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, the effects of

gefitinib on the expression of ISX, COL1A1 and EMT-related genes

were detected by RT-qPCR to preliminarily explore the mechanism of

gefitinib in inhibiting the migration and invasion of lung cancer

cells stably overexpressing ISX. Although gefitinib had no

inhibitory effect on the expression of ISX and EMT-related genes

(data not shown), the results showed that it could significantly

reduce the upregulation of COL1A1 gene expression caused by ISX

(Fig. 6C). These data initially

suggested that the mature tumor-targeting drug Iressa®

may be a promising therapeutic drug that can resist tumor

metastasis, particularly in patients with tumor metastasis caused

by high ISX expression. Moreover, the downregulation of COL1A1 gene

expression may be considered an important molecular mechanism for

its effective resistance to tumor metastasis, which is worthy of

in-depth exploration in future studies.

| Figure 6.Mature tumor-targeting drug

Iressa® (gefitinib) may inhibit the migration and

invasion of ISX-overexpressing human lung cancer cells by

regulating COL1A1. A549 cells infected with a GFP-labeled ISX

overexpression vector were treated with different concentrations of

gefitinib (0, 25, 50 µg/ml) for 48 h, and (A) cell migration (wound

healing; scale bar, 500 µm, and (B) invasion (Transwell; scale bar,

100 µm) assays were performed. (C) Reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to

detect the effect of gefitinib (25 µg/ml, 48 h) on the mRNA

expression levels of COL1A1 in ISX-overexpressing A549 cells.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ****P<0.0001. COL1A1, type I collagen

α1 chain; ISX, intestine-specific homeobox; OD, optical

density. |

Discussion

As a gut-specific HOX transcription factor, ISX is a

proto-oncogene induced by the inflammatory factor IL-6, and

previous researchers have identified the effect of ISX on cancer

development. In HCC cells, the kynurenine (KYN) pathway promotes

oncogenic activity by binding to aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) in

an ISX-dependent positive feedback loop. In addition, it has been

shown that the ISX-KYN axis upregulates immunosuppressive activity

by targeting CD86 and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression,

thereby suppressing CD8+ T-cell proliferative responses.

Thus, ISX-KYN-AHR signaling acts together with CD86 and PD-L1 to

promote the carcinogenesis and immunosuppression of HCC cells

(10). In lung cancer, ISX is

highly expressed in lung cancer cells and patient tissues, and its

upregulation is positively associated with lung cancer cell

migration and invasion. A mechanistic study has shown that the

P300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF)-ISX-bromodomain-containing

protein 4 (BRD4) axis is an important regulator of lung cancer

metastasis and cell plasticity (11). PCAF-mediated acetylation of the

transcription factor ISX promotes ISX-BRD4 translocation to the

nucleus, which activates EMT genes and induces metastasis (11).

Cancer cell migration is a complex process in which

the EMT of cancer cells is the initial step. Although numerous

signaling molecules and pathways (such as PI3K, Snail,

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and Smad interacting protein 1) and

transcription factors (TWIST1/2, SNAIL1/2, ZEB1/2 and FOXC2) have

been proposed to regulate and induce EMT (21), the detailed regulatory mechanisms

remain largely unknown. In the present study, lung cancer cells

stably overexpressing ISX were constructed by lentivirus infection,

and EMT-related gene expression was detected by RT-qPCR. It was

verified that ISX expression induced EMT response, and promoted

tumor cell migration and invasion. To further investigate the

molecular regulatory mechanisms by which the oncogene ISX enhances

tumor cell invasion and migration, transcriptome sequencing and

analysis was performed using A549 cells overexpressing ISX. The

results revealed that COL1A1 was upregulated in ISX-overexpressing

lung cancer cells, which was verified by RT-qPCR. The Cytoscape

CytoHubba analysis further identified COL1A1 as a hub gene (one of

the top five core genes) in the PPI pathway, indicating that COL1A1

may be involved in the molecular mechanism of ISX-regulated tumor

metastasis.

COL1A1 is one of the main components of the ECM, and

the dynamic balance of ECM serves a central role in maintaining the

tumor microenvironment. Numerous studies have shown that COL1A1 is

upregulated in numerous types of cancers and that it can affect

various signaling pathways related to those types of cancer,

including gastric cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, ovarian cancer,

colorectal cancer, breast cancer and thyroid cancer (15,16,22–26).

In HCC, knocking down COL1A1 markedly inhibits cell invasion and

migration, and downregulates VIM, a protein that promotes the EMT

phenotype, thus suggesting that COL1A1 may promote tumor cell

migration and invasion by promoting EMT (27). A multi-omics analysis previously

identified COL1A1 as a key gene for lung adenocarcinoma development

and progression (28).

Subsequently, the clinical importance of COL1A1 expression in lung

cancer samples and its association with clinical prognosis were

determined by detecting the expression levels of COL1A1 in lung

cancer samples. The results demonstrated that the mRNA levels and

gene amplification of COL1A1 in lung cancer tissues are higher than

those in normal lung tissues. Furthermore, COL1A1 was shown to be

highly expressed in lung cancer tissues and serum, and high

expression of COL1A1 was revealed to be associated with poor

progression-free survival and chemotherapy resistance in patients

with lung cancer. Therefore, COL1A1 may be used as a novel

diagnostic, prognostic and chemoresistance biomarker for human lung

cancer (29). Taken together,

these findings suggested that ISX may induce EMT by upregulating

COL1A1 and could alter the tumor microenvironment, thereby

promoting tumor migration and more aggressive lung cancer behavior.

This represents a novel mechanism discovered through transcriptome

sequencing in the current study. However, only A549 cells were used

in subsequent experiments. Further validation through clinical

trials is required to determine the specific type of lung cancer

associated with this mechanism; this will be a key area assessed in

our future research.

Notably, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway was enriched

in the upregulated DEGs of the ISX-overexpressing lung cancer

cells. It has been shown that knockdown of COL1A1 can inhibit the

progression of gastric cancer by regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway (22). In addition, an

association between COL1A1 and the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway has

been detected in ovarian cancer. This suggests that COL1A1 may

regulate the proliferation, anti-apoptotic ability and migratory

potential of ovarian cancer cells via the PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway (16). Therefore, the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway may also be involved in the mechanism by

which ISX regulates COL1A1 expression in lung cancer. Although

studies have shown that the PI3K/AKT pathway serves an important

role in tumors (30), to the best

of our knowledge, the specific relationship between ISX and COL1A1

and this pathway in lung cancer has not yet been reported. Future

studies should further explore the molecular mechanism of ISX

regulating lung cancer progression through COL1A1 and PI3K/AKT

signaling pathways.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

the expression levels of COL1A1 were increased in lung cancer cells

overexpressing ISX, and indicated that the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway may be involved in ISX-regulated COL1A1 expression,

promoting tumor migration and invasion. In addition, four currently

established drugs for lung cancer treatment were screened. Among

them, Iressa (gefitinib) significantly inhibited the viability,

migration and invasion of lung cancer cells stably overexpressing

ISX. The expression of COL1A1 was also significantly downregulated

after gefitinib treatment, indicating that gefitinib may be a

promising cancer drug for the treatment of tumor metastasis by

inhibiting the upregulation of COL1A1 expression caused by ISX

overexpression. The present findings revealed a novel molecular

mechanism by which ISX may promote the progression and metastasis

of lung cancer. This discovery provides new theoretical insights

into the etiology and progression of cancer, offering novel

strategies for its prevention and treatment. The aim of these

approaches is to alleviate the suffering of patients with lung

cancer and to reduce the societal burden associated with the

disease.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation (grant nos. 82341060, 82204883 and

82073950), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong

Province (grant nos. 2023A1515012245 and 2022B1515120055), the

Science and Technology Program of Shenzhen (grant nos.

JCYJ20250604191406009, JCYJ20210324134209026,

JCYJ20220531102217038, JCYJ20210324112414038 and

JCYJ20220818102005011), the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (grant

no. A2403062), the Special Fund for Economic and Technological

Development of Longgang District, Shenzhen Medical Health

Technology Project (grant no. LGWJ2021-046), the Science and

Technology Planning Project of Nanshan District (grant no.

NS2024026) and the State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease

(grant no. SKLRD-Z-202216).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The sequencing data

generated in the present study may be found in the National Center

for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive database under

accession number PRJNA1282884 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1282884.

Authors' contributions

YM, XX, JL and QH conceived and designed the

experiments. YM, YC and YL performed the experiments. YH, MG and LT

analyzed and interpreted the data. YM and XX wrote the manuscript.

XX, and QH revised the manuscript. YM, YL and XX confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cao W, Qin K, Li F and Chen W:

Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality: An

analysis of GLOBOCAN 2022. Chin Med J (Engl). 137:1407–1413. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA

and Fares Y: Molecular principles of metastasis: A hallmark of

cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:282020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Steens J and Klein D: HOX genes in stem

cells: Maintaining cellular identity and regulation of

differentiation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:10029092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chin FW, Chan SC and Veerakumarasivam A:

Homeobox gene expression dysregulation as potential diagnostic and

prognostic biomarkers in bladder cancer. Diagnostics (Basel).

13:26412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Feng Y, Zhang T, Wang Y, Xie M, Ji X, Luo

X, Huang W and Xia L: Homeobox genes in cancers: From

carcinogenesis to recent therapeutic intervention. Front Oncol.

11:7704282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yadav C, Yadav R, Nanda S, Ranga S, Ahuja

P and Tanwar M: Role of HOX genes in cancer progression and their

therapeutical aspects. Gene. 919:1485012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jasim SA, Farhan SH, Ahmad I, Hjazi A,

Kumar A, Jawad MA, Pramanik A, Altalbawy FMA, Alsaadi SB and

Abosaoda MK: Role of homeobox genes in cancer: Immune system

interactions, long non-coding RNAs, and tumor progression. Mol Biol

Rep. 51:9642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gill HK, Yin S, Nerurkar NL, Lawlor JC,

Lee C, Huycke TR, Mahadevan L and Tabin CJ: Hox gene activity

directs physical forces to differentially shape chick small and

large intestinal epithelia. Dev Cell. 59:2834–2849.e9. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang LT, Chiou SS, Chai CY, His E,

Yokoyama KK, Wang SN, Huang SK and Hsu SH: Intestine-specific

homeobox gene ISX integrates IL6 signaling, tryptophan catabolism,

and immune suppression. Cancer Res. 77:4065–4077. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang LT, Liu KY, Jeng WY, Chiang CM, Chai

CY, Chiou SS, Huang MS, Yokoyama KK, Wang SN, Huang SK and Hsu SH:

PCAF-mediated acetylation of ISX recruits BRD4 to promote

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. EMBO Rep. 21:e487952020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Devos H, Zoidakis J, Roubelakis MG,

Latosinska A and Vlahou A: Reviewing the regulators of COL1A1. Int

J Mol Sci. 24:100042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Selvaraj V, Sekaran S, Dhanasekaran A and

Warrier S: Type 1 collagen: Synthesis, structure and key functions

in bone mineralization. Differentiation. 136:1007572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li X, Sun X, Kan C, Chen B, Qu N, Hou N,

Liu Y and Han F: COL1A1: A novel oncogenic gene and therapeutic

target in malignancies. Pathol Res Pract. 236:1540132022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xiao X, Long F, Yu S, Wu W, Nie D, Ren X,

Li W, Wang X, Yu L, Wang P and Wang G: Col1A1 as a new decoder of

clinical features and immune microenvironment in ovarian cancer.

Front Immunol. 15:14960902025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu Y, Xue J, Zhong M, Wang Z, Li J and

Zhu Y: Prognostic prediction, immune microenvironment, and drug

resistance value of collagen type I alpha 1 chain: From

gastrointestinal cancers to pan-cancer analysis. Front Mol Biosci.

8:6921202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang C, Liu S, Wang X and Liu H, Zhou X

and Liu H: COL1A1 Is a potential prognostic biomarker and

correlated with immune infiltration in mesothelioma. Biomed Res

Int. 2021:53209412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ribeiro Gomes J and Cruz MRS: Combination

of afatinib with cetuximab in patients with EGFR-mutant

non-small-cell lung cancer resistant to EGFR inhibitors. Onco

Targets Ther. 8:1137–1142. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Della Corte CM, Fasano M, Ciaramella V,

Cimmino F, Cardnell R, Gay CM, Ramkumar K, Diao L, Di Liello R,

Viscardi G, et al: Anti-tumor activity of cetuximab plus avelumab

in non-small cell lung cancer patients involves innate immunity

activation: Findings from the CAVE-Lung trial. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 41:1092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chanvorachote P, Petsri K and Thongsom S:

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in lung cancer: Potential

EMT-targeting natural product-derived compounds. Anticancer Res.

42:4237–4246. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ding Y, Zhang M, Hu S, Zhang C, Zhou Y,

Han M, Li J, Li F, Ni H, Fang S and Chen Q: MiRNA-766-3p inhibits

gastric cancer via targeting COL1A1 and regulating PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway. J Cancer. 15:990–998. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang Y, Mei X, Song W, Wang C and Qiu X:

LncRNA LINC00511 promotes COL1A1-mediated proliferation and

metastasis by sponging miR-126-5p/miR-218-5p in lung

adenocarcinoma. BMC Pulm Med. 22:2722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li Y, Sun R, Zhao X and Sun B: RUNX2

promotes malignant progression in gastric cancer by regulating

COL1A1. Cancer Biomark. 31:227–238. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhong J and Yang

R: COL1A1 promotes metastasis in colorectal cancer by regulating

the WNT/PCP pathway. Mol Med Rep. 17:5037–5042. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Huang C, Yang X, Han L, Fan Z, Liu B,

Zhang C and Lu T: The prognostic potential of alpha-1 type I

collagen expression in papillary thyroid cancer. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 515:125–132. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ma HP, Chang HL, Bamodu OA, Yadav VK,

Huang TY, Wu ATH, Yeh CT, Tsai SH and Lee WH: Collagen 1A1 (COL1A1)

is a reliable biomarker and putative therapeutic target for

hepatocellular carcinogenesis and metastasis. Cancers (Basel).

11:7862019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang Z, Liu B, Lin T, Zhang Y, Zhang L and

Wang M: Multiomics analysis on DNA methylation and the expression

of both messenger RNA and microRNA in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cell

Physiol. 234:7579–7586. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hou L, Lin T, Wang Y, Liu B and Wang M:

Collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain is a novel predictive biomarker of

poor progression-free survival and chemoresistance in metastatic

lung cancer. J Cancer. 12:5723–5731. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Noorolyai S, Shajari N, Baghbani E,

Sadreddini S and Baradaran B: The relation between PI3K/AKT

signalling pathway and cancer. Gene. 698:120–128. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|