Introduction

Estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis is a bone

metabolic disease characterized by changes in bone density and

microstructure, resulting in increased bone fragility and a higher

risk of fracture. After menopause, patients lose ~50% of trabecular

bone mass and 30% of cortical bone mass compared with those at

20–30 years of age (1).

Postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMOP) is directly related to an

increased risk of bone fracture. A European Union study showed that

a 50-year-old female patient has a 46% chance of developing an

osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime (2). Currently, the commonly used

therapeutic drugs in clinics for PMOP include hormone replacement

therapy, bisphosphonate, parathyroid hormone and selective estrogen

receptor modulators. Hormone replacement therapy is the most

effective treatment, but is associated with risks such as breast

cancer, uterine bleeding and cardiovascular disease (3).

YC is the dry aboveground part of Artemisia

scoparia Waldst. et Kit. or Artemisia capillaris Thunb.

YC extract alleviates bone loss through a dual mechanism: Enhancing

osteoblast-mediated mineralization and suppressing osteoclast

differentiation (4). Using mass

spectrometric analysis and activity screening, subsequent studies

have further identified specific bioactive constituents responsible

for inhibiting osteoclast formation and bone resorption, primarily

via attenuation of acidification processes. These findings indicate

the potential of YC as a natural candidate for the treatment of

osteoporosis (4,5). The main components of YC include

coumarin, flavonoids, organic acids, volatile oil and terpenoids,

which have anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antibacterial,

cytoprotective and anti-osteoporotic effects. Chlorogenic acid,

artemisinolide, hyperoside and scopoletin have been reported to be

the most active ingredients in the extract (6–11).

Chlorogenic acid can promote bone marrow stromal

cell (BMSC) proliferation and osteogenic differentiation through

the Shp2 pathway (12). In

addition, chlorogenic acid upregulates the neuronatin gene in

ovariectomized (OVX) mice, activates the MAPK signaling pathway and

promotes the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs (13). It can also activate the nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1)

pathway, inhibit the excessive production of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) and reduce oxidative stress levels (14). Chlorogenic acid has also been shown

to downregulate the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

(RANKL)-induced phosphorylation of p38 and ERK in bone marrow

macrophages, and to inhibit the expression of nuclear factor of

activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 1, thereby inhibiting osteoclast

differentiation and bone resorption (15,16).

Hyperoside can promote the proliferation and osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs and improve the bone microstructure of OVX

mice by enhancing microRNA-19a-5p and downregulating IL-17A

(16–18). Furthermore, YC can downregulate the

expression of NADPH oxidase 1 and inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclast

differentiation, thereby inhibiting bone loss (17). Scopoletin can inhibit osteoclast

differentiation by scavenging ROS (19).

Cell death consists of programmed cell death and

non-programmed cell death. In 2012, Dixon et al (20) proposed ferroptosis as a new mode of

cell death that is different from other methods of programmed cell

death. When cells are subjected to excess stimulation or the

antioxidant system is defective, lipid peroxides will gradually

accumulate and eventually trigger ferroptosis. Glutathione

peroxidase 4 (Gpx4) was the first core inhibitor of ferroptosis

identified, and other Gpx4-independent pathways or factors that

inhibit ferroptosis have since been found, including the system

xc−/Gpx4, ferroptosis suppressor protein

1/NAD(P)H/coenzyme Q10 and GTP cyclohydrolase

1/Tetrahydrobiopterin/dihydrofolate reductase axes (21–23).

System xc-is a cystine/glutamate antiporter composed of the solute

carrier family 7 member 11 (Slc7a11) and Slc3a2 subunits, which is

crucial for cellular glutathione synthesis and antioxidant defense.

Dysfunction of Slc7a11 can impair cystine uptake, leading to

glutathione depletion and heightened susceptibility to ferroptosis

(24). Lipid peroxidation is an

important factor for ROS-induced oxidative stress in bone tissue.

Gpx4-knockout mice show a notable reduction in bone mineral density

(BMD) and ovariectomy can aggravate osteoporosis in Gpx4-knockout

mice (25). Nrf2 is also important

for regulating ferroptosis in osteocytes. Knockdown of Nrf2 in

osteocytes can induce ferroptosis and activation of Nrf2 can

inhibit RANKL expression (26).

YC is a potential drug for preventing osteoporosis;

ferroptosis may be a potential target for the treatment of

osteoporosis; and the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 pathway is an important

pathway in regulating ferroptosis. However, the regulatory effects

of YC on ferroptosis in osteoporosis remain ambiguous. Therefore,

the present study aimed to investigate the regulatory effect of YC

on PMOP from the perspective of ferroptosis and to further explore

the effect of YC on the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 ferroptosis regulatory

pathway.

Materials and methods

Experimental drugs

YC (TongRenTang Chinese Medicine) was mixed with

distilled water in a magnetic stirrer for 2 h at room temperature

and then crushed using a juicer. The juice was then filtered and

concentrated in a rotary evaporator to obtain 1 and 0.5 g/ml of

solution, which was stored at −20°C for later use. Estradiol

valerate acid tablets (EV) (cat. no. J20130009; Bayer) were ground

into powder, dissolved in distilled water a suspension of estradiol

was obtained in an ultrasound-assisted manner with a concentration

of 0.013 mg/ml.

Experimental animals

The study was conducted in strict accordance with

the animal experiment ethics regulations of the Institute of Basic

Theory for Chinese Medicine, China Academy of Chinese Medical

Sciences and were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics

Committee (approval no. IBTCMCACMS21-2303-04; Beijing, China). A

total of 40 specific pathogen-free female C57BL/6 mice (age, 8

weeks; weight, 20±2 g) were obtained from SPF Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd. [license no. SCXK(Beijing)2021-0010]. The mice were housed

under conventional conditions (room temperature 22±1°C, humidity

50±5%, 12/12-h light/dark cycle) with free access to food and

water. They were randomly divided into five groups: i) Sham

operation (SHAM) group treated with 10 ml/kg distilled water via

oral gavage; ii) OVX model group treated with 10 ml/kg distilled

water via oral gavage; iii) EV group treated with 0.13 mg/kg EV for

12 weeks via oral gavage; iv) YC low dose (YCL), treated with 5

g/kg YC water extract via oral gavage for 12 weeks; and v) YC high

dose (YCH) group treated with 10 g/kg YC water extract via oral

gavage for 12 weeks. Bilateral ovariectomy was performed on mice in

the OVX and medication groups. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized

by intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg).

An incision was made on the dorsal side, cauliflower-like ovarian

tissue was ligated, the ovaries were removed and the wound was

sutured. In the Sham group, the operation was the same as for the

experimental groups but only a small amount of adipose tissue

surrounding the ovary was ligated and excised. Drugs were given

starting 1 week after surgery, continuing for 12 weeks, with all

treatments administered once daily at the same time each day.

After the last administration, the mice were

euthanized by an intraperitoneal overdose of pentobarbital sodium

(100 mg/kg) and death was confirmed by a cessation of heartbeat and

respiration. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture (0.8–1.2 ml

per mouse) and allowed to stand at room temperature for 2 h. The

uterus was dissected and weighed, and the uterine coefficient was

calculated as uterine wet weight (mg)/body weight (g). The liver

was removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation

solution at room temperature for 24 h, whereas the femur was fixed

in 4% PFA fixation solution at room temperature for 48 h after

removing the muscle from the bone. Subsequently, the fixation

solution was replaced with fresh 4% PFA for long-term storage at

room temperature. The tibia was preserved at −80°C. Humane

endpoints were defined as follows: Severe weight loss (>20%),

inability to access food or water, signs of severe pain or

distress, such as hunched posture, lethargy or vocalization, or any

other condition that would compromise animal welfare. No animals

reached these endpoints during the study.

Ultra-performance liquid

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)

The aforementioned prepared water solution of YC was

added to an equal amount of internal standard extract (70%

methanol), centrifuged at ~13,800 × g for 3 min at 4°C and the

supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-µm filter membrane to

obtain the sample for later use. Analysis was performed on Agilent

SB-C18 columns (.8 µm, 2.1 mm × 100.0 mm; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.) using an ExionLC AD UPLC system (Sciex). The liquid phase

conditions consisted of a mobile phase, in which phase A was

ultrapure water with 0.1% formic acid and phase B was acetonitrile

with 0.1% formic acid. The elution gradient was as follows: i) 0

min, the proportion of phase B was 5%; ii) 9 min, the proportion of

phase B linearly increased to 95% and was maintained for 1 min; and

iii) subsequently the proportion of phase B decreased to 5% and was

equilibrated at 5% for 14 min. The flow rate was 0.35 ml/min, the

column temperature was 40°C and the injection volume was 2 µl. MS

conditions were as follows: Electrospray ionization source

temperature, 550°C; ion spray voltage, 5,500 V (positive ion

mode)/-4,500 V (negative ion mode); ion source gas I, gas II and

curtain gas were set to 50, 60 and 25 psi, respectively; and the

collision-induced ionization parameter was set to high. Scans were

performed in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode with the

collision gas, nitrogen, set to medium. The de-clustering potential

and collision energy of each MRM ion pair were further optimized. A

specific set of MRM ion pairs was monitored at each period based on

the metabolites eluted within each period. A specific set of MRM

transitions was monitored for each period according to the

metabolites eluted within this period, based on the optimized

precursor ion (Q1) and product ion (Q3) m/z values. Finally,

components that have been proven to have anti-osteoporotic activity

in existing literature were selected from the 2,072 compounds for

further investigation in the present study (5,18,19).

Micro-CT

To evaluate the changes in bone morphology in mice,

micro-CT was performed on the femurs of mice using Skyscan1276

(Bruker) with the following scan parameters: 6.5 µm, 70 kV and 200

mA. The lowest point of the lateral growth plate of the femoral

knee joint was taken as the baseline and the area with a thickness

of 1 mm was set as the 3D reconstruction area of interest. The

NRecon software (version 1.7.1.0, Bruker) was used for 3D image

reconstruction and the CTAn software (version 1.17.7.2, Bruker) was

used to evaluate the BMD (mg/cm3), bone volume/total

volume (BV/TV, %), trabecular number (Tb.N, 1/mm), trabecular

separation (Tb.Sp, mm) and structure model index (SMI).

ELISA

Blood was collected following euthanasia by an

overdose of pentobarbital sodium (as aforementioned) via cardiac

puncture, with 0.8–1.2 ml collected per mouse. Serum was collected

by centrifugation at 1,900 × g for 15 min at 4°C after 2 h at room

temperature. in addition, mouse tibias were ground into a powdery

form under liquid nitrogen using a grinding mill. PBS was added to

the powdered tibia samples, and homogenized using a low-temperature

grinder. Subsequently, the homogenate was centrifuged at 1,900 × g

for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for analysis.

The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and

glutathione (GSH) in the mouse tibia and serum, as well as

estradiol (E2), tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), and

osteocalcin (OCN) in serum alone, were detected using commercial

ELISA kits strictly according to the manufacturers' protocols. The

specific kits employed were as follows: Mouse MDA ELISA Kit (cat.

no. F9264-A; Shanghai Kexing Trading Co., Ltd.), Mouse 4-HNE ELISA

Kit (cat. no. F9213-A; Shanghai Kexing Trading Co., Ltd.), Mouse

GSH ELISA Kit (cat. no. F2658-A; Shanghai Kexing Trading Co.,

Ltd.), and Mouse E2 ELISA Kit (cat. no. MB-3302A; Jiangsu Meibiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The absorbance was recorded at 450 nm. A

standard curve was generated from the absorbance values of the

standard wells, which allowed for the calculation of sample

concentration.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

H&E staining was performed on 5-µm

paraffin-embedded mouse femur sections to distinguish bone

trabeculae from bone marrow. The femurs were dehydrated through a

graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin

prior to sectioning. The sections were baked at 67°C for 2 h,

deparaffinized in xylene I and II (10 min each) and rehydrated

through a graded ethanol series (100, 95 and 75%; 3 min each).

Subsequently, the sections were stained with hematoxylin at room

temperature for 3 min, rinsed with tap water, differentiated, blued

and washed again. After dehydration in 75 and 95% ethanol (5 min

each), eosin staining was carried out at room temperature for 5

min, followed by rinsing with distilled water. Sections were

further dehydrated in absolute ethanol (three changes, 5 min each),

cleared in xylene and mounted with neutral resin. Finally, images

were acquired using a slide scanner.

Masson's trichrome

Masson's staining can stain collagen fibers blue,

reflecting the maturity of bone tissue. Femoral specimens of mice

were fixed and decalcified, before being embedded as

aforementioned. The slices were baked at 67°C for 2 h,

deparaffinized, and rehydrated. The slices were stained

sequentially at room temperature using Weigert's iron hematoxylin

for 5 min, ponceau magenta for 5 min and aniline blue for 1 min.

Following dehydration, the slices were sealed with neutral resin.

Finally, the images were acquired by scanning the slices using a

slide scanner.

Prussian blue dyeing

Under acidic conditions, potassium ferrocyanide can

react with iron trivalent to form a blue compound, Prussian blue,

to detect liver iron ion levels. The liver tissue was dehydrated

with a gradient alcohol series and permeabilized by xylene after

fixation but before embedding. The paraffin-embedded liver was then

cut into 5-µm sections and placed on a slide to dry. Following

dewaxing as aforementioned, the Prussian blue stain was prepared

according to the manufacturer's instructions (Solarbio, G1422) and

added at room temperature for 20 min, before sections were washed

with distilled water for 5 min. Sections were stained with nuclear

solid red at room temperature for 8 min and rinsed for 3 sec. After

dehydration, the sections were sealed with neutral resin and the

images were scanned by a slide scanner.

Immunohistochemistry staining

Mouse femur specimens were fixed, decalcified,

embedded and sectioned as aforementioned. Sections were

deparaffinized, antigen retrieval was performed using EDTA antigen

retrieval solution A and B (cat. no. SBT10013; Shunbai

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; both incubated at 37°C for 30 min), and

the sections blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature

for 10 min for 30 min. Triton X-100 (0.04%) was used to

permeabilize the sections for 20 min at room temperature and goat

serum (10%; cat. no. ZLI-9022; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used to block the sections for 60 min

at room temperature. Sections were incubated with the following

primary antibodies: Anti-osteoprotegerin (OPG; 1:50; cat. no.

ab73400; Abcam), anti-runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2;

1:50; cat. no. ab236639; Abcam), Nrf2 polyclonal antibody (1:200;

cat. no. 16396-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), Slc7a11 polyclonal

antibody (1:50; cat. no. 26864-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

Gpx4 monoclonal antibody (1:50; cat. no. 67763-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) at 37°C overnight. Sections were incubated with an

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:2000;

cat. no. GB23204; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C

for 120 min and biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:2,000; cat.

no. PV-9001; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for

120 min at room temperature. For the comparative analysis of marker

expression, additional sections were processed using optimized

antibody concentrations and incubation conditions: primary antibody

incubation at 37°C for 1 h, followed by secondary antibody

incubation at 37°C for 20 min. The sections were treated with color

developing solution (DAB Kit; cat. no. ZLI-9017; Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The staining results were

observed under a light microscope.

Dual immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed by binding

fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies to primary antibodies to

label corresponding proteins. Paraffin-embedded sections prepared

as aforementioned were deparaffinized and rehydrated in absolute,

95 and 75% ethanol, then antigen retrieval was performed using

antigen retrieval reagents A and B (both incubated at 37°C for 30

min), endogenous peroxidase blocker was added and the sections were

incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently,

the sections were blocked with 10% rabbit serum (cat. no. ZLI-9026;

Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 30 min, and incubated with Gpx4 monoclonal antibody

(1:50; cat. no. 67763-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and OCN

antibody (1:100; cat. no. ab93876; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. The

corresponding fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor

488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:200, cat. no. ab150113,

Abcam; Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200, cat.

no. ab150080, both Abcam) were added at room temperature for 50 min

in the dark, followed by tyramide signal amplification reaction at

room temperature for 10 min in the dark. Finally, DAPI staining was

performed, the slices were dehydrated and blocked with anti-fade

mounting medium and fluorescence was excited according to the

corresponding wavelength of the dye using a fluorescence

microscope.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The expression levels of genes related to

ferroptosis were detected by RT-qPCR. Tibia samples were ground

into powder in liquid nitrogen using a grinder, collected into

centrifuge tubes and placed on ice. RNA was extracted from the

tissue using the TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) method according to standard operating

procedures. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the

PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The primer sequences utilized for

quantifying the expression levels of nuclear receptor coactivator 4

(Ncoa4), ferritin heavy chain (Fth), Nrf2, Slc7a11 and Gpx4 genes

are provided in Table I.

Amplification was performed using Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix

(High Rox Plus; cat. no. 11203ES08; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) under the following conditions: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for

5 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for 20 sec. Gene expression

levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method (27), with Gapdh as the reference gene for

data normalization.

| Table I.Primer sequence. |

Table I.

Primer sequence.

| Gene | Forward, 5′-3′ | Reverse, 5′-3′ |

|---|

| Ncoa4 |

CCCTTCCAGAAATGAGCTAACA |

GCCACTCTGACAAGGAACTATT |

| Fth |

TGACCACGTGACCAACTTAC |

CGTCAGCTTAGCTCTCATCAC |

| Nrf2 |

GGCTCAGCACCTTGTATCTT |

CACATTGCCATCTCTGGTTTG |

| Slc7a11 |

CTGGTCAGCCAGCTTATGAA |

AGGAGGATGCTGCCAATAAC |

| Gpx4 |

TGTGCATCCCGCGATGATT |

CCCTGTACTTATCCAGGCAGA |

| Gapdh |

GAATGGGAAGCTGGTCATCAA |

CCAGTAGACTCCACGACATACT |

Statistical analysis

SPSS v.26.0 (IBM Corp.) was used for data analysis.

All of the obtained data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Main components of YC

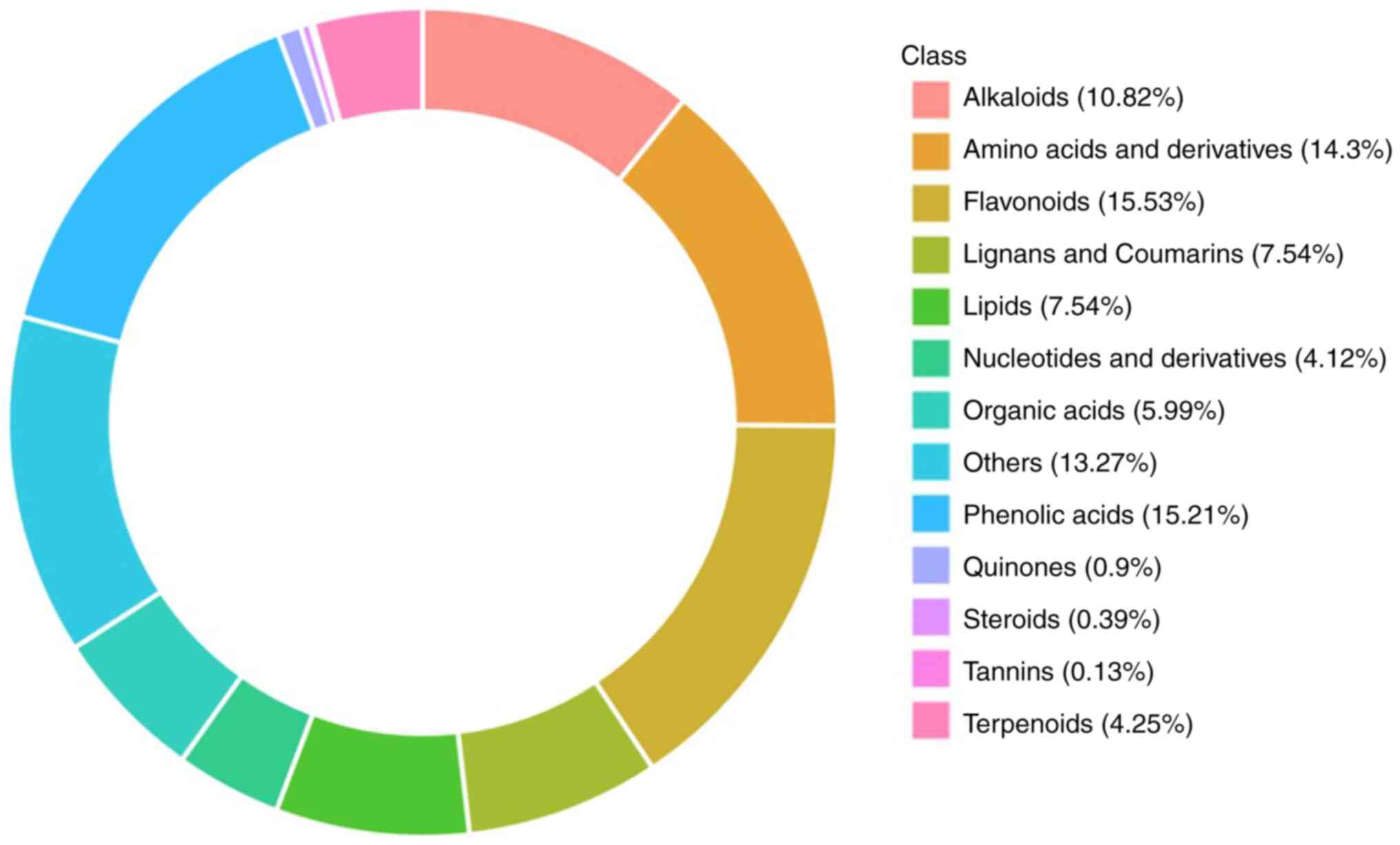

The main components of YC were determined using

UPLC-MS/MS and the results are shown in Fig. 1 according to the relative content

of various compounds. A total of 2,072 compounds were identified,

which were divided into 13 categories, including 333 phenolic

acids, 308 flavonoids, 259 amino acids and their derivatives, 233

alkaloids, 205 lipids, 134 lignans and coumarin, 127 organic acids,

113 terpenoids, 69 nucleotides and their derivatives, 23 quinones,

16 steroids, 5 tannins and 247 others. The main active ingredients

of YC included chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acid,

artemisininolide, artemisinin, scopoletin, quercetin, hyperoside,

isorhamnetin and isoquercitrin (data not shown). The 10 compounds

listed in Table II were selected

based on their documented anti-osteoporotic activities in previous

literature and their relative abundance in the extract (5,9,10,28).

| Table II.Relative content of the active

components of Yinchen. |

Table II.

Relative content of the active

components of Yinchen.

| Chemical

compound | Molecular

formula | Category | Retention time,

min | Relative

content |

|---|

| Caffeic acid |

C9H8O4 | Phenolic acids | 3.4 | 2136.26 |

| Ferulic acid |

C10H10O4 | Phenolic acids | 4 | 1277.59 |

| Chlorogenic

acid |

C16H18O9 | Phenolic acids | 2.7 | 737.32 |

| Scopoletin |

C10H8O4 | Lignans and

coumarin | 4.1 | 659.48 |

| Isoquercitrin |

C21H20O12 | Flavone | 4 | 247.29 |

| Artemisinin |

C11H10O4 | Lignans and

coumarin | 5 | 97.44 |

| Quercetin |

C15H10O7 | Flavone | 5.1 | 74.37 |

| Chromenone |

C16H12O7 | Lignans and

coumarin | 5.8 | 57.39 |

| Isorhamnetin |

C16H12O7 | Flavone | 5.8 | 9.02 |

| Hyperoside |

C21H20O12 | Flavone | 3.6 | 1.00 |

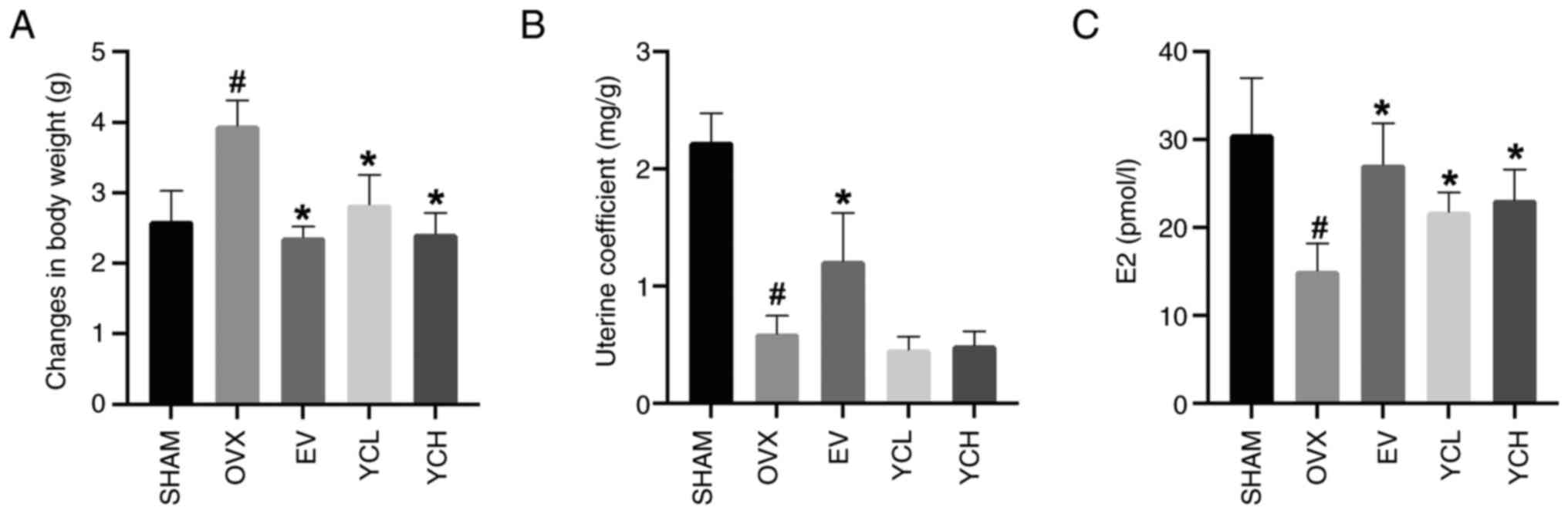

Effect of YC on weight change, uterine

coefficient and serum estradiol in OVX mice

In the present study, as shown in Fig. 2, OVX mice had significantly lower

serum estradiol levels compared with those in SHAM mice. OVX mice

also showed a significant increase in body weight and a

significantly lower uterine coefficient compared with those in the

SHAM group. Notably, the administration of YC significantly

reversed these changes in body weight and estradiol levels,

although no significant difference in uterine coefficient was

observed between the OVX and YC groups. EV treatment also

significantly increased the uterine coefficient compared with the

OVX group. However, there were no significant differences observed

between the YCL and YCH groups.

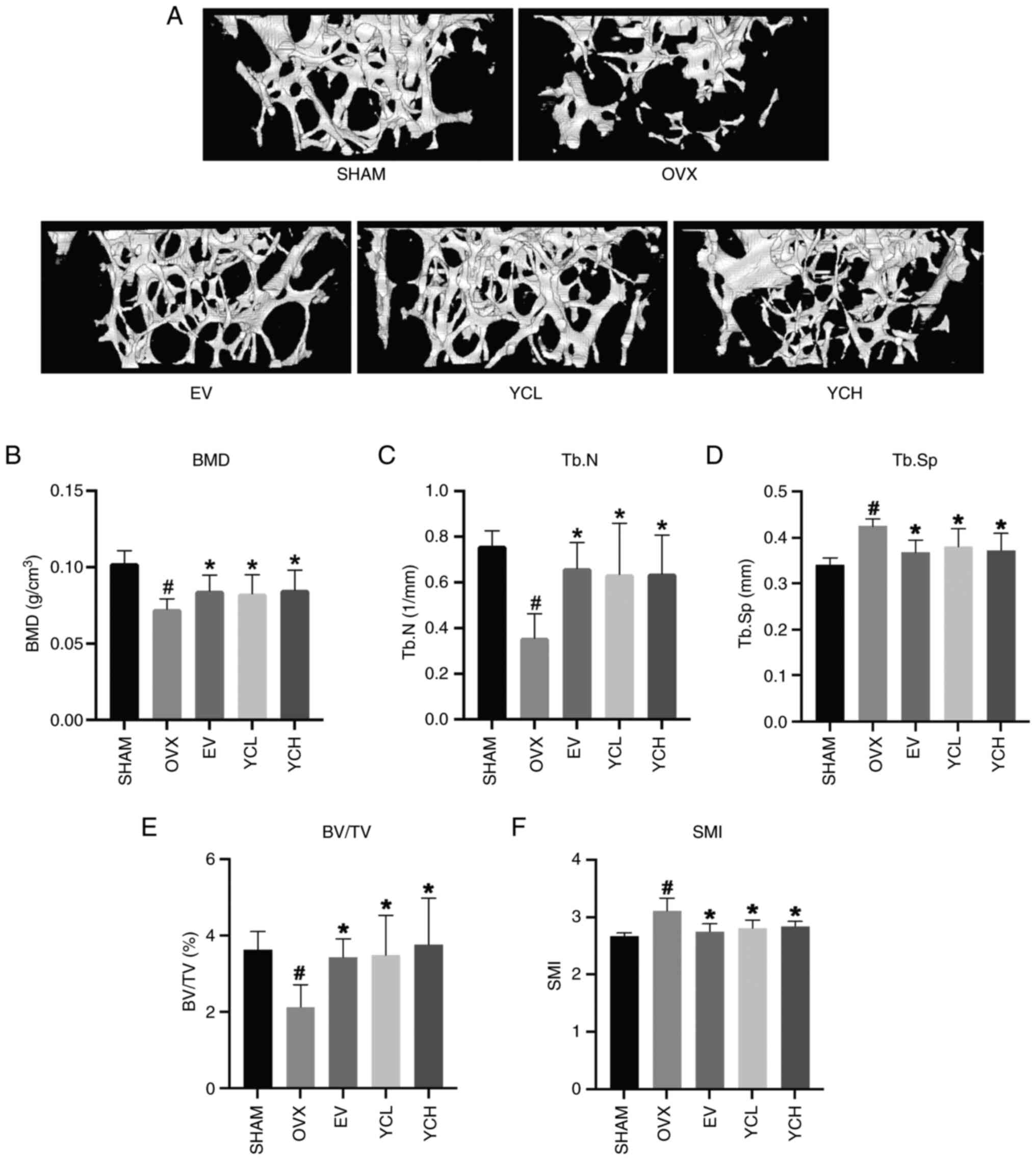

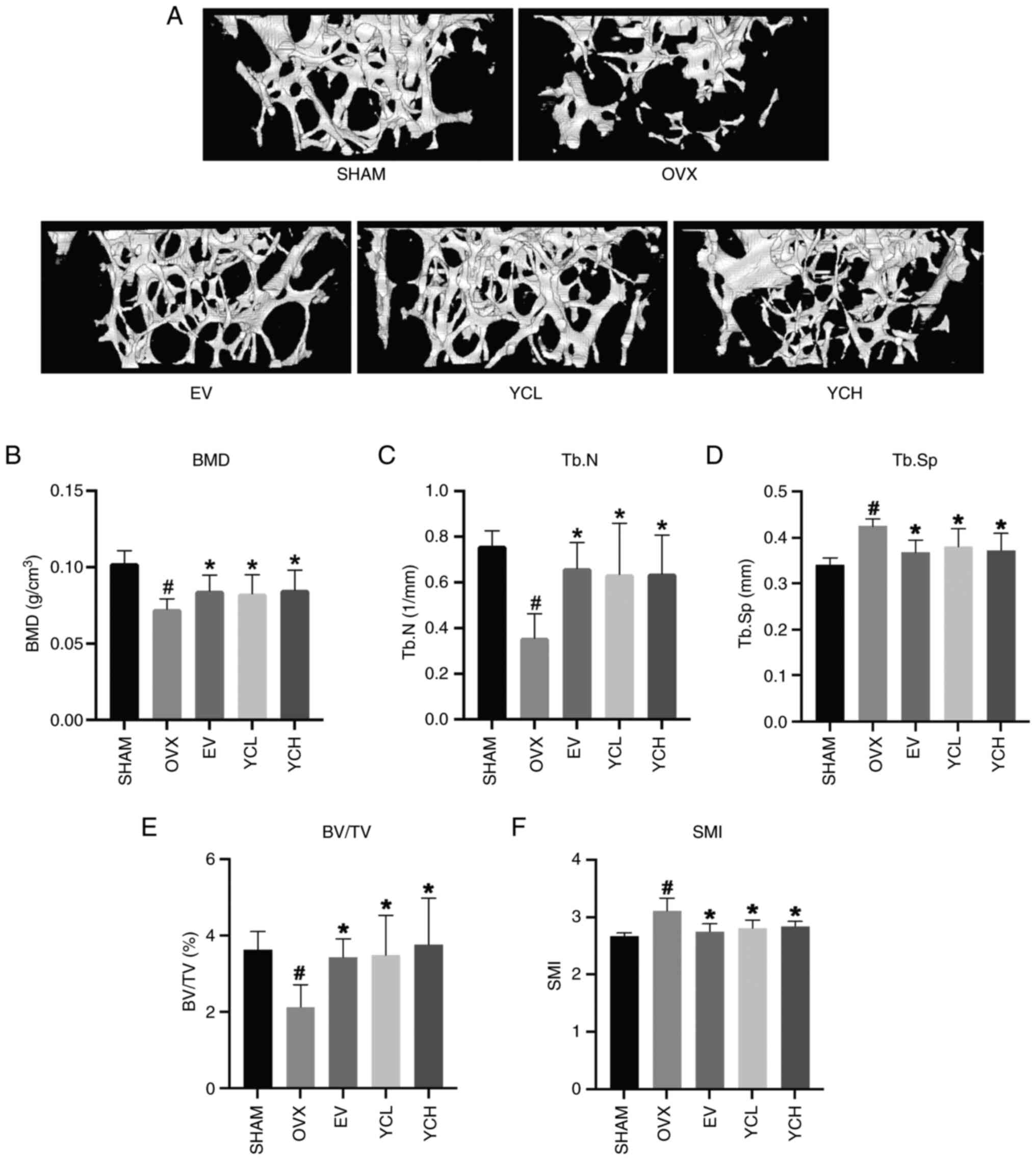

Effect of YC on femoral bone

microstructure in OVX mice

Micro-CT analysis was used to investigate the effect

of YC on bone microstructure in OVX mice. As shown in Fig. 3A, the femoral trabeculae of mice in

the SHAM group were thick, closely arranged and continuous, whereas

the number of femoral trabeculae of mice in the OVX group was

markedly reduced, the bone microstructure was broken, and the

number and sizes of gaps increased. Both EV and YC treatment

markedly improved the deteriorated trabecular structure observed in

OVX mice. As shown in Fig. 3B-F

morphometric parameters further supported the observed changes in

trabecular microstructure in the different groups. Consistent with

the scanned images, OVX mice had significantly reduced BMD, BV/TV

and Tb.N compared with those in the SHAM group, whereas SMI and

Tb.Sp were significantly increased. However, the independent

application of YC and estradiol significantly ameliorated these

changes.

| Figure 3.Effect of YC on femoral bone

microstructure in OVX mice. (A) Micro-CT scanning images of bone

microstructure. Changes in (B) BMD, (C) Tb.N, (D) Tb.Sp, (E) BV/TV

and (F) SMI. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n=8.

#P<0.05 vs. SHAM group; *P<0.05 vs. OVX group.

OVX, ovariectomized; EV, estradiol valerate; YC, Yinchen; YCL, YC

low dose; YCH, YC high dose; BMD, bone mineral density; Tb.N,

trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; BV/TV, bone

volume/total volume; SMI, structure model index. |

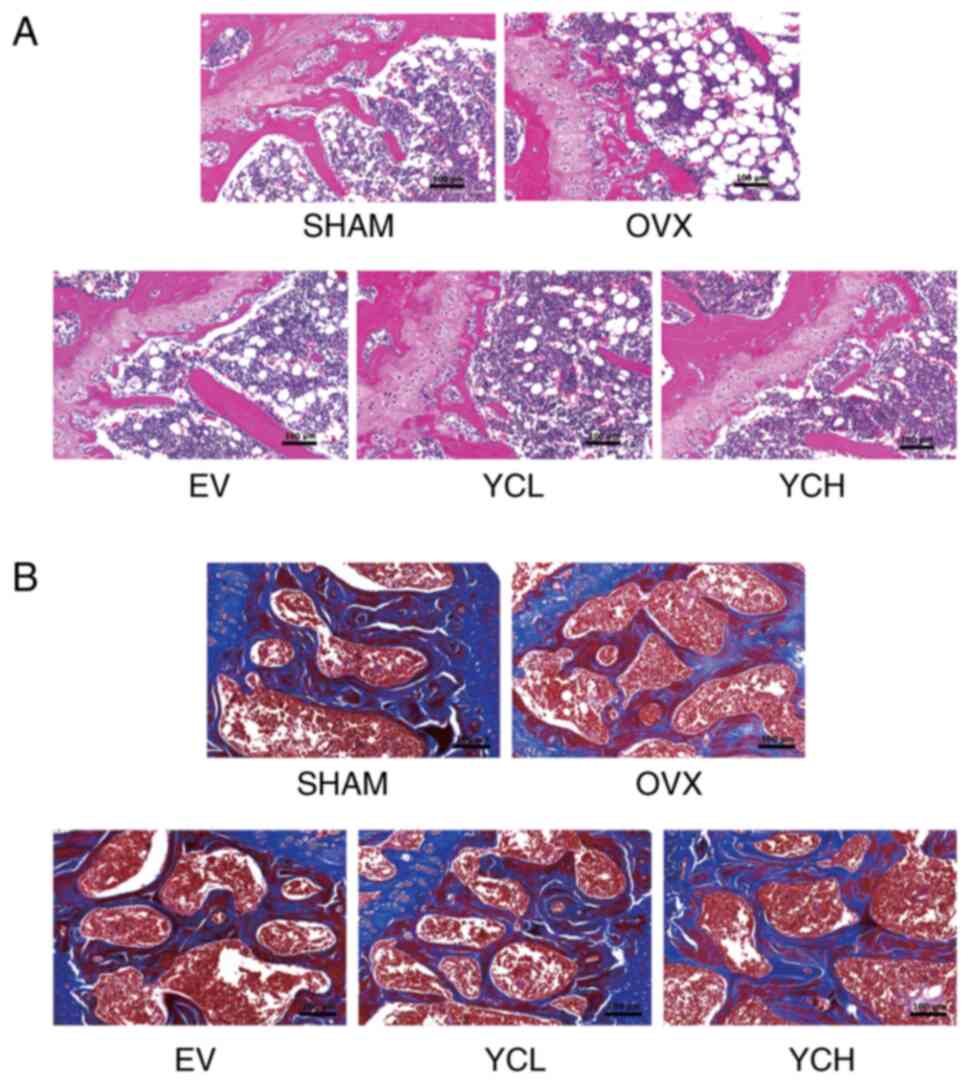

Effect of YC on the pathological

morphology of femurs in OVX mice

To further evaluate the effect of YC on trabecular

structure, H&E staining was performed on the femurs of mice. As

shown in Fig. 4A, a well-organized

trabecular meshwork and a small bone marrow cavity were observed in

the SHAM group. However, in the OVX group, it was found that the

bone marrow cavity was enlarged, the trabecular structure was

disordered and the lipid droplets in the bone marrow were markedly

increased. H&E staining also showed that EV and YC ameliorated

the histopathological changes in bone structure caused by

ovariectomy. Masson's staining in Fig.

4B showed that, compared with in the SHAM group, the femoral

bone trabeculae of the OVX group were thinner and more sparsely

arranged, with increased spacing and less collagen. These changes

were notably ameliorated in the EV and YC groups.

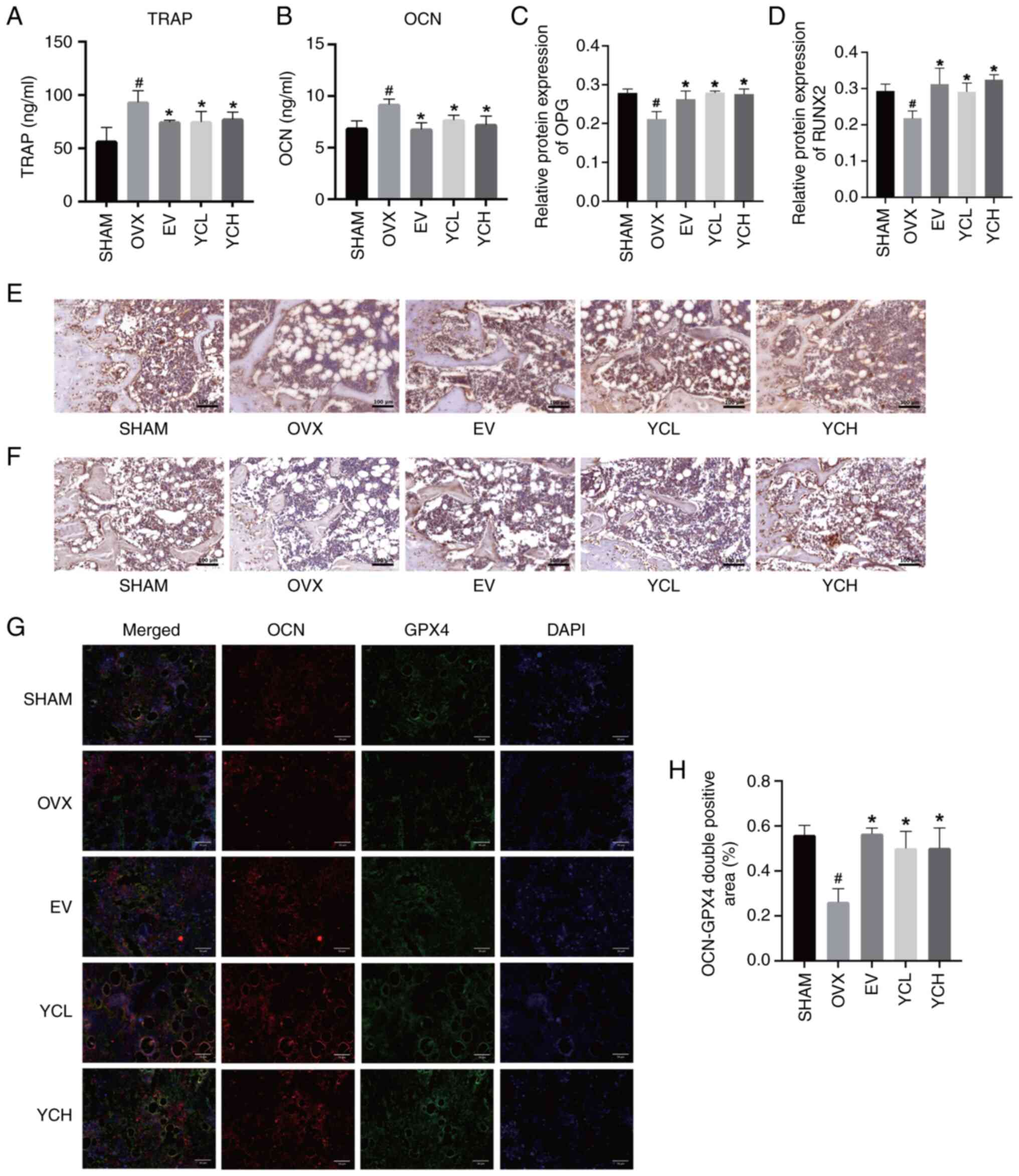

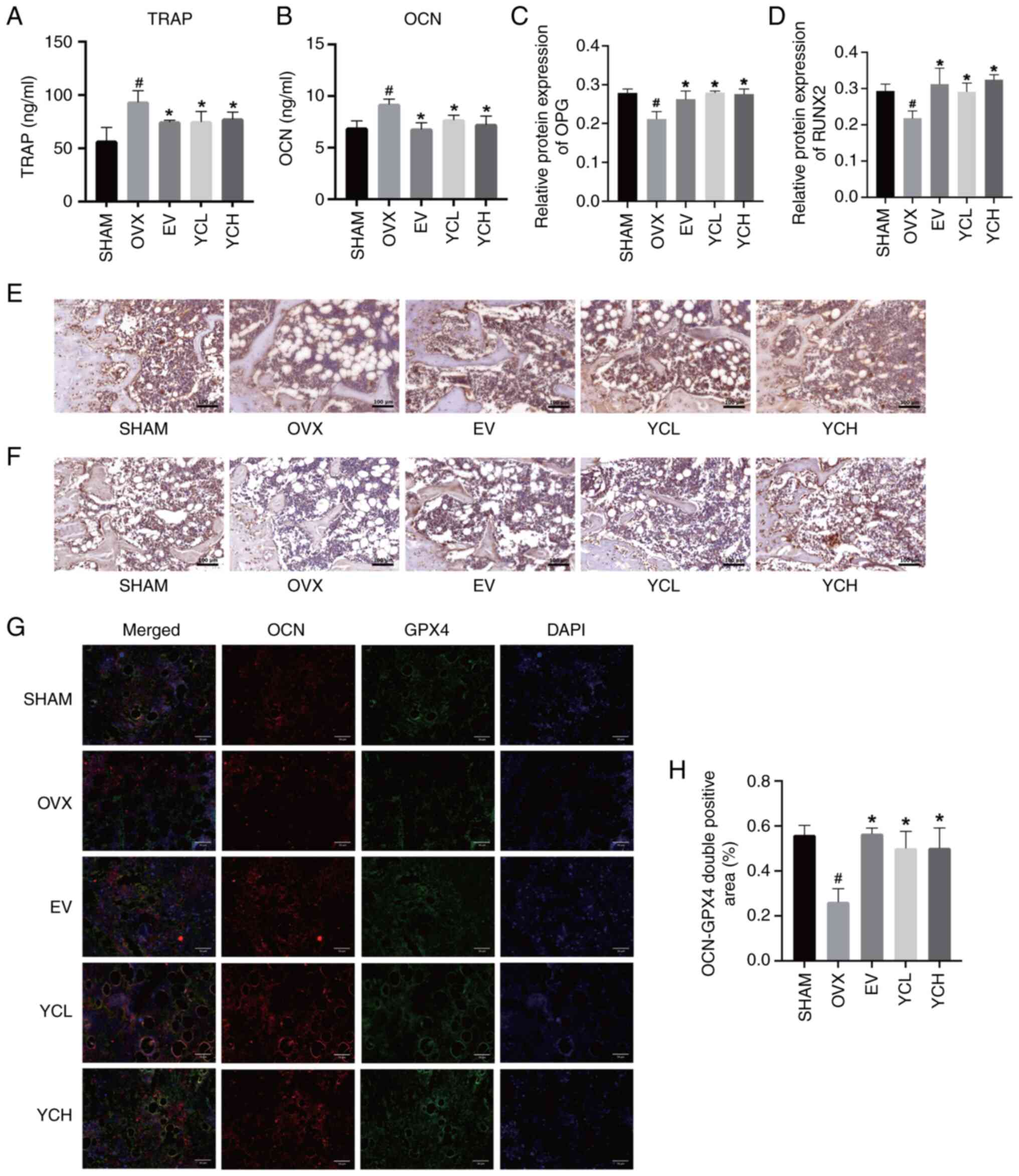

Effect of YC on bone metabolism in OVX

mice

The anti-osteoporotic effect of YC was monitored by

detecting the serum levels of TRAP and OCN through ELISA, the

results of which were shown in Fig. 5A

and B. Compared with those in the SHAM group, the serum levels

of TRAP and OCN in the OVX group were significantly increased (both

P<0.05). These results indicated that ovariectomy resulted in an

increased turnover rate of bone metabolism, whereas EV and YC

significantly reduced the concentrations of these serum markers

compared with those in the OVX group. However, there was no

significant difference observed between the YCL and YCH groups.

| Figure 5.Effect of YC on bone metabolism in

OVX mice. Results of (A) TRAP and (B) OCN ELISA. Relative protein

expression levels of (C) OPG and (D) RUNX2. Immunohistochemical

staining of (E) OPG and (F) RUNX2 protein expression (×200

magnification). (G) Double immunofluorescence staining images of

OCN and GPX4 (×400 magnification). (H) OCN-GPX4 double positive

area. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; n=8.

#P<0.05 vs. SHAM group; *P<0.05 vs. OVX group.

OVX, ovariectomized; EV, estradiol valerate; YC, Yinchen; YCL, YC

low dose; YCH, YC high dose; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid

phosphatase; OCN, osteocalcin; OPG, osteoprotegerin; RUNX2,

runt-related transcription factor 2; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase

4. |

Subsequently, femurs were subject to

immunohistochemical staining, with RUNX2 and OPG being the key

factors regulating the dynamic balance of bone tissue (29,30).

As shown in Fig. 5C-F, the

expression of OPG and RUNX2 in the OVX group was significantly

lower than that in the SHAM group. Ovariectomy reduced bone

formation in mice, whereas the EV and YC groups significantly

increased the expression of OPG and RUNX2. The expression of RUNX2

in the femur of the YCH group was higher than that of the YCL

group, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The osteoblast-specific marker OCN and ferroptosis

inhibitor Gpx4 were co-stained by immunofluorescence staining to

observe the expression of Gpx4 in femoral osteoblasts (Fig. 5G and H). Compared with in the SHAM

group, the expression of Gpx4 in the femoral osteoblasts of OVX

mice was significantly decreased, whereas EV and YC treatment

significantly increased Gpx4 expression levels.

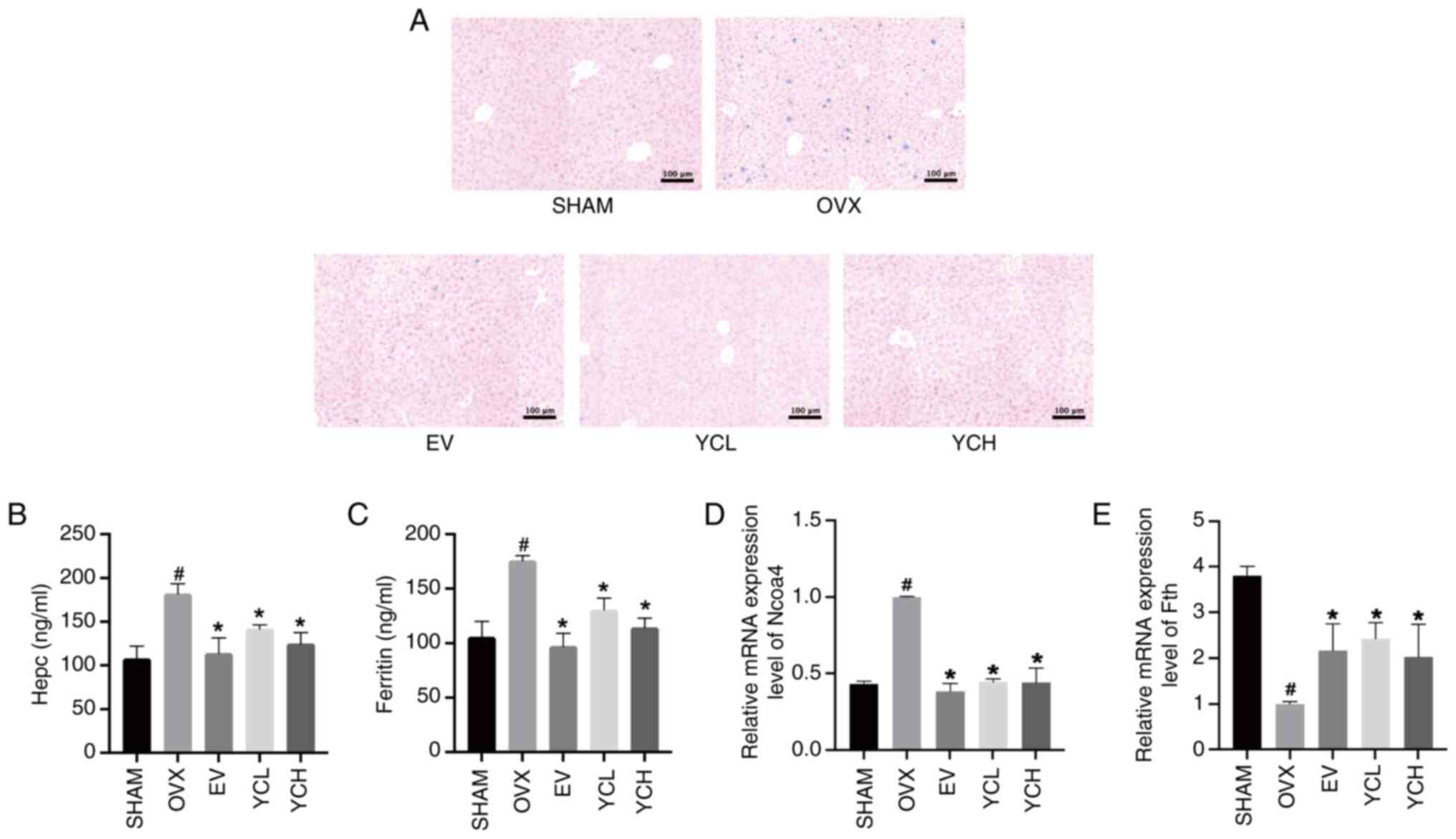

Effect of YC on iron metabolism in OVX

mice

The liver is the main iron storage organ and when

iron accumulates, the liver exhibits increased iron deposition

(31). The iron ion content of

liver sections was determined by Prussian blue staining (Fig. 6A). Compared with that in the Sham

group, OVX mice demonstrated more punctate staining and heavier

iron deposition in the liver, which was effectively reduced in the

EV and YC groups.

Ferritin and hepcidin levels were subsequently

measured by ELISA, whereas Ncoa4 and Fth mRNA expression levels

were measured by RT-qPCR; the results of these assays were shown in

Fig. 6B-E. Compared with those in

the SHAM group, the levels of ferritin, hepcidin and Ncoa4 were

significantly increased in OVX mice whereas the expression of Fth

was significantly decreased. However, EV and YC administration

significantly reversed these changes (all P<0.05).

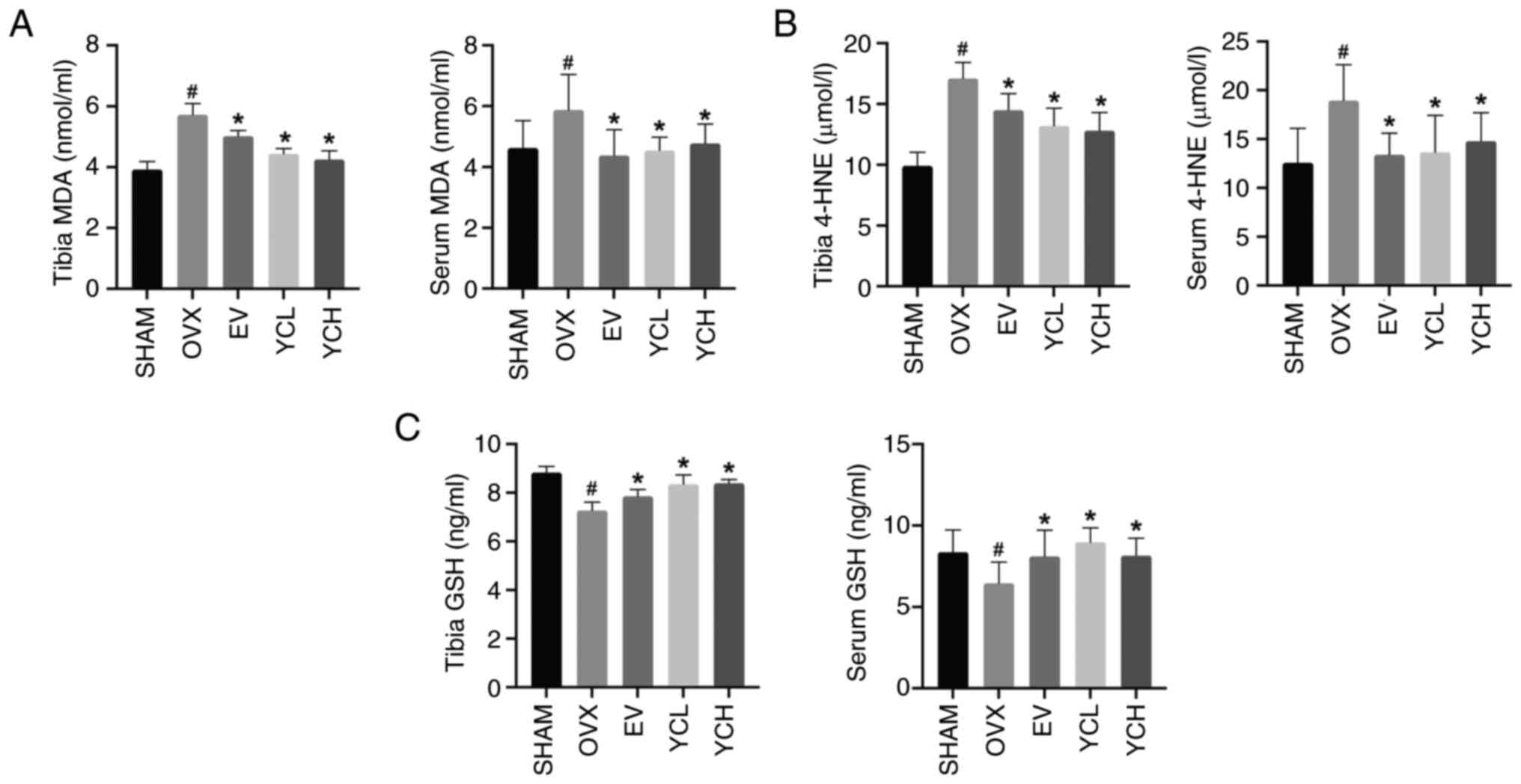

Effect of YC on lipid peroxidation in

OVX mice

Lipid peroxidation is an important link in

ferroptosis, and the accumulation of lipid peroxides in the local

membrane is the key reaction leading to cell death (32). MDA, 4-HNE and GSH contents in the

tibias and sera of mice were measured by ELISA (Fig. 7). Compared with those in the SHAM

mice, the levels of MDA and 4-HNE were significantly increased in

OVX mice, whereas the levels of GSH were significantly decreased.

EV and YC significantly reversed the changes in MDA, 4-HNE and GSH

in the serum and tibias after ovariectomy.

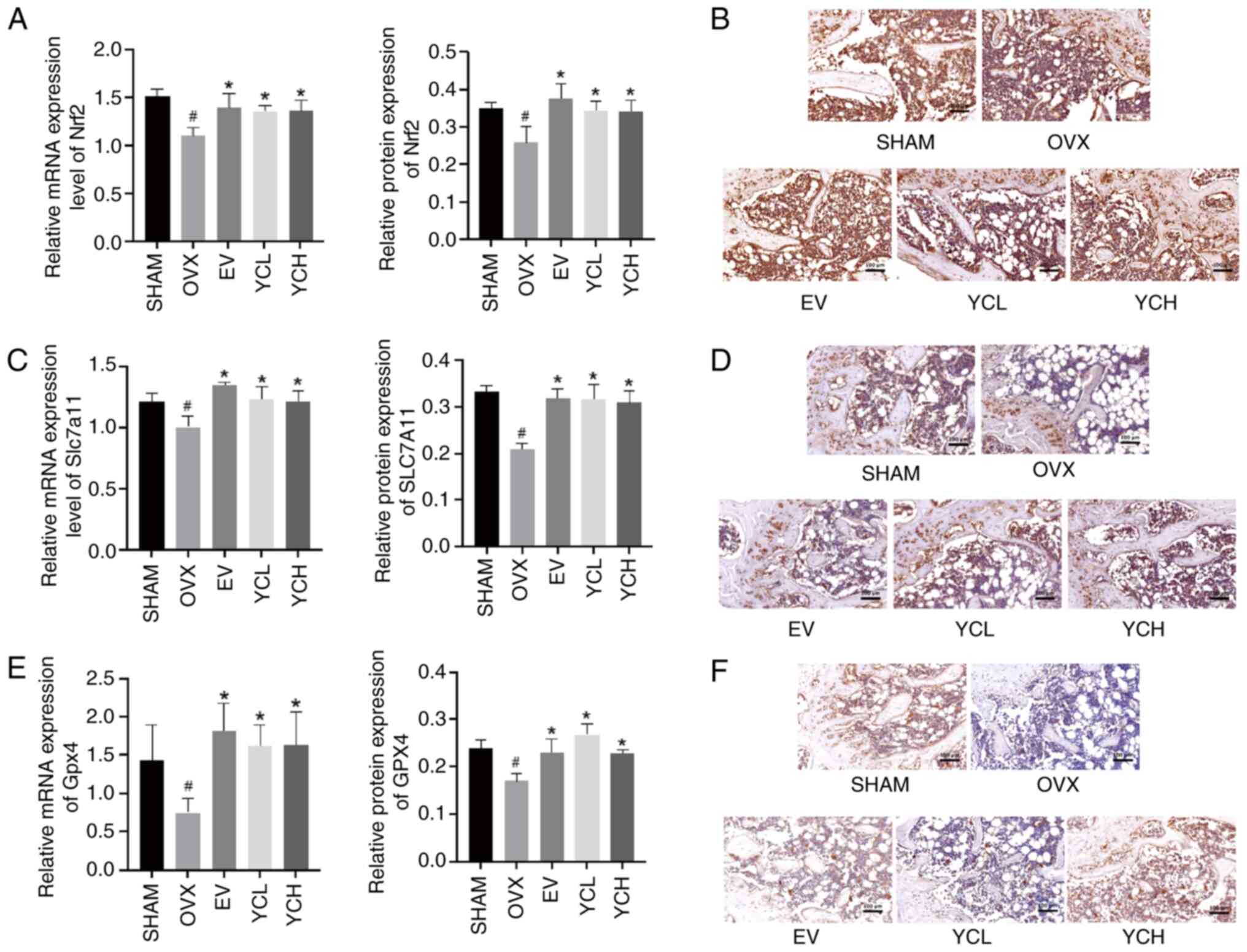

Effect of YC on the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4

pathway

The expression levels of Nrf2, Slc7a11 and Gpx4 in

the bone tissue of mice were detected by RT-qPCR and

immunohistochemistry (Fig. 8).

Compared with those in the SHAM group, the mRNA and protein

expression levels of Nrf2, Slc7a11 and Gpx4 in the bone tissue of

OVX mice were significantly decreased. By contrast, compared with

those in the OVX mice, EV and YC treatment significantly increased

their expression levels.

Discussion

In the present study, UPLC-MS/MS was used to detect

the active components of YC. The OVX osteoporotic mouse model was

used to simulate PMOP, and the effects and mechanism of YC in the

treatment of osteoporosis were explored. Reduced estrogen levels

lead to a gradual decrease in osteoblast number and activity,

resulting in a reduced rate of bone formation (26). When osteoporosis occurs, BMSCs are

more likely to transform into adipocytes than in healthy

individuals (33). In the present

study, estradiol levels in the serum of YC-treated mice were

increased and mouse body weight was decreased, indicating that YC

improved the reduction of estrogen levels and body weight gain

caused by ovariectomy, but could not restore the uterine atrophy

caused by ovariectomy, as indicated by the lack of significant

difference in uterine coefficient. In addition, in OVX mice, the

trabecular bone destruction was notable, the formation of lipid

droplets in the bone marrow cavity increased and bone formation

decreased.

TRAP and OCN are serum markers of bone turnover

(34). Increased levels of bone

turnover markers may precede changes in BMD. In OVX mice, the

present study detected elevated levels of TRAP and OCN in mouse

serum. RUNX2 is a key osteogenic transcription factor. In immature

osteoblasts, RUNX2 can regulate the expression of bone matrix

proteins, such as secreted phosphoprotein 1, collagen type I α1,

collagen type I α2 and OCN, and can induce the maturation of

osteoblasts (35,36). OPG is secreted by osteoblasts and

can competitively bind to RANKL. It also inhibits the binding of

RANKL to RANK. OPG-null mice exhibit reduced whole-body BMD,

whereas the use of RANKL inhibitors can enhance Wnt/β-catenin

signaling and induce bone formation in OPG null mice (37,38).

Immunohistochemistry showed that the expression levels of OPG and

RUNX2 were decreased in the femurs of OVX mice compared with those

in the Sham group, indicating that bone formation was inhibited in

the bone tissue of mice with ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis,

whereas the administration of YC was shown to promote the

expression of osteogenesis-related factors in bone tissue.

Ferroptosis is a novel mode of cell death

characterized by iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation.

Ferroptosis is involved in high-fat-induced bone loss, and

ferroptosis in high-fat-fed osteoporotic mice can be inhibited by

intraperitoneal injection of ferrostatin-1 (39). In a mouse model of diabetic

osteoporosis, the levels of lipid peroxides in the body are

increased and the levels of osteogenic markers are decreased

(40). Another study found that

type 2 diabetes can reduce the expression of mitochondrial ferritin

in bone tissue and cause ferroptosis (41). Serum levels of the ferroptosis

markers Gsh, Gpx4 and MDA can more effectively predict the

occurrence of PMOP compared to conventional bone turnover markers

such as OCN and C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen. Iron

overload occurs in postmenopausal women, and the increase in iron

levels after menopause may be related to the loss of the pathway of

menstrual blood loss to expel ferritin (42,43).

This implies that ferroptosis may be an important mechanism in the

pathogenesis of osteoporosis.

Hepcidin is the core factor regulating the balance

of iron metabolism, and the level of hepcidin is regulated by the

feedback of iron level in the body. Hepcidin-knockout mice display

increased serum iron and ferritin content, increased liver and bone

iron content and inhibited osteogenic differentiation (44,45).

Ferritin is the predominant iron storage protein in cells, which is

composed of Fth and ferritin light chain. Fth is the principal

iron-storing subunit of ferritin. In a state of iron deficiency,

Ncoa4 can recognize and bind to Fth, degrade Fth, release iron ions

into cells, promote lipid peroxidation and induce ferroptosis

(46). The etiology of

osteoporosis is notably associated with the overproduction of lipid

peroxides, which represents the terminal stage of ferroptosis

(47). In the present study, serum

ferritin levels were elevated in OVX mice, indicating that iron

accumulation has occurred. At the same time, the liver iron ion

level of OVX mice was notably increased.

Ncoa4 can promote the degradation of Fth and release

iron ions into the cells, which is a process involved in

ferroptosis (32). Therefore, the

present study examined the expression levels of Ncoa4 and Fth in

the tibia of OVX mice; RT-qPCR analysis revealed that Ncoa4 was

found to be significantly increased, whereas Fth levels were

decreased in OVX mice compared with the Sham group. On the other

hand, lipid peroxidation is an important feature of ferroptosis.

Excess intracellular iron participates in the production of

peroxide and then participates in the formation of lipid peroxide

with polyunsaturated fatty acids (48). The significant increase in MDA and

4-HNE levels, and decrease in GSH levels in the serum and bone

tissues of OVX mice compared with in the SHAM mice in the present

study indicated that lipid peroxidation was elevated in the OVX

mice. The results of immunofluorescence double staining of OCN and

Gpx4 showed that the co-staining area of OCN and Gpx4 in the femurs

of OVX mice was significantly reduced compared with that in the

SHAM mice, indicating that Gpx4 expression was decreased, and the

level of iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation in the OVX mice

was increased, which suggested that the bone tissue of OVX mice

exhibited ferroptosis.

Upon treatment with YC, mice displayed the following

changes compared with OVX mice: i) Serum ferritin and hepcidin

levels, and liver iron ion content were decreased; ii) Ncoa4

expression in bone tissue was decreased; iii) the expression levels

of Fth in bone tissue was increased; iv) MDA and 4-HNE levels in

serum and bone tissue were decreased; v) GSH levels were increased;

and Gpx4 expression was increased. These results suggested that YC

improved osteoporosis in OVX mice by inhibiting ferroptosis.

Nrf2 is a key regulator of cellular antioxidant

responses, which drive transcriptional responses that inhibit

ferroptosis (26,49). Under physiological conditions, Nrf2

is maintained at low levels in the cytoplasm by interacting with

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) to form a complex.

Under oxidative stress, Keap1 is degraded by autophagy and Nrf2 is

released into the cytoplasm. Subsequently, free Nrf2 is transported

to the nucleus where it binds to antioxidant response elements and

initiates downstream reactions (26). Nrf2 can regulate factors related to

GSH synthesis and metabolism, including the catalytic and

regulatory subunits of glutamate-cysteine ligase, GSH synthetase

and the system xc− subunits Slc7a11 and Gpx4 (24). Thus, Nrf2 is a key repressor of the

ferroptosis response. In pancreatic cancer cells, Nrf2 can activate

microsomal GSH S-transferase 1, inhibiting lipoxygenase 5 (Alox5)

and ferroptosis (50). Studies

have confirmed that increased Nrf2 expression can inhibit

ferroptosis and that downregulation of Nrf2 expression can increase

the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis (26,51).

The results of the present study showed that this pathway was

inhibited in OVX mice. By contrast, YC increased the expression of

Gpx4 and OCN in OVX mouse osteoblasts and activated the

Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 pathway. Previous studies have confirmed that

kakaferol can enhance cellular antioxidant capacity, inhibit the

accumulation of lipid peroxides in neurons and inhibit ferroptosis

by activating the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 pathway; pachynic acid has also

been shown to inhibit oxygen-glucose

deprivation/re-oxygenation-induced lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes by activating this pathway (26,52).

Taken together, it can be inferred that YC may inhibit osteoblast

ferroptosis by activating the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 pathway, thereby

promoting bone formation and improving osteoporosis in OVX mice.

While YC may exert its effects through multiple pathways, the

present study focused on the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 axis due to its

established role in ferroptosis and bone metabolism. Future studies

should investigate other potential pathways, such as HO-1 and

RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation, to provide an improved

comprehensive mechanistic understanding of the effects of YC on

osteoporosis.

In addition, Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that

regulates cellular antioxidant responses and iron metabolism. It

modulates susceptibility to ferroptosis by regulating the

expression of a series of downstream genes, including several

directly involved in ferroptosis. For example, Fth1 facilitates

iron storage, reducing the intracellular labile iron pool and

thereby attenuating ferroptotic cell death. Similarly, Gpx4 is a

notable enzyme that suppresses lipid peroxidation and Nrf2 can

upregulate Gpx4 expression to inhibit ferroptosis (53,54).

Based on the association between the Nrf2 pathway and ferroptosis,

the present study investigated the regulatory role of YC in this

pathway (55).

The present study had a number of limitations to be

acknowledged. Primarily, the causal relationship between YC

treatment and the activation of the Nrf2 pathway was not directly

validated through genetic or pharmacological interventions in the

present study, with the inference primarily relying on changes in

biomarker expression and existing literature. Furthermore, although

UPLC-MS/MS identified numerous compounds, the synergistic or

antagonistic interactions among the constituents within the YC

extract remain unexplored and the exact bioactive components

responsible for the observed effects require further isolation and

functional verification. Additionally, biomechanical assessments,

such as the three-point bending test, were not performed to

evaluate bone strength improvement. Finally, while the dosage used

in the present study (5–10 g/kg) is within the range of clinical

applications of YC in traditional Chinese medicine, which can reach

up to 100 g/day in human patients (56,57),

chronic toxicity and comprehensive safety profiles of YC at these

doses were not systematically investigated, which are important for

evaluating its clinical translational potential. Future studies

employing Nrf2-knockout models and ferroptosis inducers are

warranted to conclusively establish the causal role of the

Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 axis in mediating the anti-osteoclastogenic

effects of YC while the incorporation of functional biomechanical

tests and component-specific approaches will be important to fully

elucidate the therapeutic potential of YC for bone disorders.

In conclusion, the present study suggested the

effectiveness of YC in potentially mitigating ovariectomy-induced

osteoporosis in mice. YC promoted bone formation and improved bone

microstructure by potentially inhibiting ferroptosis via activation

of the Nrf2/Slc7a11/Gpx4 pathway in OVX mice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82074297) and the Fundamental

Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes

(grant nos. YZ-202244, YZX202335 and YZX202235).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The UPLC-MS/MS data

generated in the present study may be found in the MetaboLights

public database under accession number MTBLS13042 or at the

following URL: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/editor/MTBLS13042).

Authors' contributions

PL and ZZ conceived the study. PL, YC and ZZ

contributed to the methodology development. WL performed the

experiments. XW, YY and DC analyzed data. PL wrote the manuscript.

RZ made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data and

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content. ZZ and HL also participated in critical revision of the

manuscript. YW contributed to project administration, participated

in data interpretation and revised the manuscript. HL supervised

the overall research design, interpreted the key results and

acquired the funding. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. PL and XW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were performed in strict

accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Institute of Basic

Theory for Chinese Medicine, China Academy of Chinese Medical

Sciences, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics

Committee (approval no. IBTCMCACMS21-2303-04). Efforts were made to

minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals

used.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Duboeuf F and

Delmas PD: Markers of bone turnover predict postmenopausal forearm

bone loss over 4 years: The OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res.

14:1614–1621. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M,

Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jönsson B and Kanis

JA: Osteoporosis in the European union: Medical management,

epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in

collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF)

and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations

(EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos. 8:1362013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

An J, Yang H, Zhang Q, Liu C, Zhao J,

Zhang L and Chen B: Natural products for treatment of osteoporosis:

The effects and mechanisms on promoting Osteoblast-mediated bone

formation. Life Sci. 147:46–58. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lee CJ, Shim KS and Ma JY: Artemisia

capillaris alleviates bone loss by stimulating osteoblast

mineralization and suppressing osteoclast differentiation and bone

resorption. Am J Chin Med. 44:1675–1691. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee SH, Lee JY, Kwon YI and Jang HD:

Anti-Osteoclastic activity of Artemisia capillaris thunb.

Extract depends upon attenuation of osteoclast differentiation and

bone Resorption-associated acidification due to chlorogenic acid,

hyperoside, and scoparone. Int J Mol Sci. 18:3222017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu YP, Qiu XY, Liu Y and Ma G: Research

progress on the pharmacological effects of Artemisiae Scopariae

Herba. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 50:2235–2241.

2019.(In Chinese).

|

|

7

|

Witaicenis A, Seito LN, Da Silveira Chagas

A, de Almeida LD Jr, Luchini AC, Rodrigues-Orsi P, Cestari SH and

Di Stasi LC: Antioxidant and intestinal Anti-inflammatory effects

of Plant-derived coumarin derivatives. Phytomedicine. 21:240–246.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zeinali M, Rezaee SA and Hosseinzadeh H:

An overview on immunoregulatory and Anti-inflammatory properties of

chrysin and flavonoids Substances. Biomed Pharmacother.

92:998–1009. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gupta A, Atanasov AG, Li Y, Kumar N and

Bishayee A: Chlorogenic acid for cancer prevention and therapy:

Current status on efficacy and mechanisms of Action. Pharmacol Res.

186:1065052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ding J, Wang L, He C, Zhao J, Si L and

Huang H: Artemisia scoparia: Traditional uses, active

constituents and pharmacological effects. J Ethnopharmacol.

273:1139602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gan DL, Yao Y, Su HW, Huang YY, Shi JF,

Liu XB and Xiang MX: Volatile oil of Platycladus orientalis

(L.) Franco leaves exerts strong Anti-inflammatory effects via

inhibiting the IκB/NF-κB pathway. Curr Med Sci. 41:180–186. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou RP, Deng MT, Chen LY, Fang N, Du C,

Chen LP, Zou YQ, Dai JH, Zhu ML, Wang W, et al: Shp2 regulates

chlorogenic acid-induced proliferation and adipogenic

differentiation of bone Marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in

adipogenesis. Mol Med Rep. 11:4489–4495. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xu T, Wu X, Zhou Z, Ye Y, Yan C, Zhuge N

and Yu J: Hyperoside ameliorates periodontitis in rats by promoting

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via activation of the NF-κB

pathway. FEBS Open Bio. 10:1843–1855. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Han D, Chen W, Gu X, Shan R, Zou J, Liu G,

Shahid M, Gao J and Han B: Cytoprotective effect of chlorogenic

acid against hydrogen Peroxide-induced oxidative stress in MC3T3-E1

cells through PI3K/Akt-mediated Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

Oncotarget. 8:14680–14692. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Folwarczna J, Pytlik M, Zych M, Cegieła U,

Nowinska B, Kaczmarczyk-Sedlak I, Sliwinski L, Trzeciak H and

Trzeciak HI: Effects of caffeic and chlorogenic acids on the rat

skeletal system. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 19:682–693.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kwak SC, Lee C, Kim JY, Oh HM, So HS, Lee

MS, Rho MC and Oh J: Chlorogenic acid inhibits osteoclast

differentiation and bone resorption by down-regulation of receptor

activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand-induced nuclear factor

of activated T cells c1 expression. Biol Pharm Bull. 36:1779–1786.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lee SH and Jang HD: Scoparone attenuates

RANKL-induced osteoclastic differentiation through controlling

reactive oxygen species production and scavenging. Exp Cell Res.

331:267–277. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

An H, Chu C, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wei R, Wang

B, Xu K, Li L, Liu Y, Li G and Li X: Hyperoside alleviates

postmenopausal osteoporosis via regulating miR-19a-5p/IL-17A axis.

Am J Reprod Immunol. 90:e137092023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lee SH, Ding Y, Yan XT, Kim YH and Jang

HD: Scopoletin and scopolin isolated from Artemisia

iwayomogi suppress differentiation of osteoclastic macrophage

RAW 264.7 cells by scavenging reactive oxygen species. J Nat Prod.

76:615–620. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to Gpx4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP Cyclohydrolase

1/Tetrahydrobiopterin Counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R and Zhang DD:

NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and

Ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 23:1011072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang Z, Qi G, He X, Yu Y, Cao Y, Zhang C,

Zou W and Yuan H: Ferroptosis in osteocytes as a target for

protection against postmenopausal osteoporosis. Adv Sci (Weinh).

2024:e23073882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects

against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology.

63:173–184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kim TE, Jo YH and Kim CT: Improvement of

quality characteristics of mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruit

extract using high-pressure enzymatic treatment. Food Bioprocess

Technol. 17:4106–4114. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gnoumou E, Tran TA, Yang TT, Quach TT and

Wang CY: Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and anti-osteoclastogenic

effects of synthetic mineralized lysozyme nanoparticles for

treating infectious osteoporosis. Int J Biol Macromol.

320:1457692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li P, Dai J, Li Y, Alexander D, Čapek J,

Geis-Gerstorfer J, Wan G, Han J, Yu Z and Li A: Zinc based

biodegradable metals for bone repair and regeneration: Bioactivity

and molecular mechanisms. Mater Today Bio. 25:1009322024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pietrangelo A: Iron and the Liver. Liver

Int. 36 (Suppl 1):S116–S123. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wu Z, Zhu Y, Liu W, Balasubramanian B, Xu

X, Yao J and Lei X: Ferroptosis in liver disease: Natural active

compounds and therapeutic implications. Antioxidants (Basel).

13:3522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Karadeniz F, Oh JH, Lee JI, Seo Y and Kong

CS: 3,5-dicaffeoyl-epi-quinic acid from Atriplex gmelinii

enhances the osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow-derived

human mesenchymal stromal cells via WnT/BMP signaling and

suppresses adipocyte differentiation via AMPK activation.

Phytomedicine. 71:1532252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bauer NB, Khassawna TE, Goldmann F, Stirn

M, Ledieu D, Schlewitz G, Govindarajan P, Zahner D, Weisweiler D,

Schliefke N, et al: Characterization of bone turnover and energy

metabolism in a rat model of primary and secondary osteoporosis.

Exp Toxicol Pathol. 67:287–296. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Komori T: Whole aspect of Runx2 functions

in skeletal development. Int J Mol Sci. 23:57762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Fakhry M, Hamade E, Badran B, Buchet R and

Magne D: Molecular mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell

differentiation towards osteoblasts. World J Stem Cells. 5:136–148.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee B, Thirunavukkarasu K, Zhou L, Pastore

L, Baldini A, Hecht J, Geoffroy V, Ducy P and Karsenty G: Missense

mutations abolishing DNA binding of the osteoblast-specific

transcription factor OSF2/CBFA1 in cleidocranial dysplasia. Nat

Genet. 16:307–310. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ozaki Y, Koide M, Furuya Y, Ninomiya T,

Yasuda H, Nakamura M, Kobayashi Y, Takahashi N, Yoshinari N and

Udagawa N: Treatment of OPG-deficient mice with WP9QY, a

Rankl-binding peptide, recovers alveolar bone loss by suppressing

osteoclastogenesis and enhancing osteoblastogenesis. PLoS One.

12:e01849042017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhu R, Wang Z, Xu Y, Wan H, Zhang X, Song

M, Yang H, Chai Y and Yu B: High-fat diet increases bone loss by

inducing ferroptosis in osteoblasts. Stem Cells Int.

2022:93594292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang Y, Lin Y, Wang M, Yuan K, Wang Q, Mu

P, Du J, Yu Z, Yang S, Huang K, et al: Targeting ferroptosis

suppresses osteocyte glucolipotoxicity and alleviates diabetic

osteoporosis. Bone Res. 10:262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang X, Ma H, Sun J, Zheng T, Zhao P, Li H

and Yang M: Mitochondrial ferritin deficiency promotes osteoblastic

ferroptosis via mitophagy in type 2 diabetic osteoporosis. Biol

Trace Elem Res. 200:298–307. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zimmermann MB and Hurrell RF: Nutritional

iron deficiency. Lancet. 370:511–520. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Clark SF: Iron deficiency anemia. Nutr

Clin Pract. 23:128–141. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Shen GS, Yang Q, Jian JL, Zhao GY, Liu LL,

Wang X, Zhang W, Huang X and Xu YJ: Hepcidin1 knockout mice display

defects in bone microarchitecture and changes of bone formation

markers. Calcif Tissue Int. 94:632–639. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lu H, Lian L, Shi D, Zhao H and Dai Y:

Hepcidin promotes osteogenic differentiation through the bone

morphogenetic protein 2/small mothers against decapentaplegic and

mitogen-activated protein kinase/P38 signaling pathways in

mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Med Rep. 11:143–150. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Fang Y, Chen X, Tan Q, Zhou H, Xu J and Gu

Q: Inhibiting ferroptosis through disrupting the NCOA4-FTH1

interaction: A new mechanism of action. ACS Cent Sci. 7:980–989.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu P, Zhang Z, Cai Y, Li Z, Zhou Q and

Chen Q: Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and role in diabetes mellitus and

its complications. Ageing Res Rev. 94:1022012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Le Y, Liu Q, Yang Y, Stanford D, Freeman

WM and Ding XQ: The emerging role of nuclear receptor coactivator 4

in health and disease: A novel bridge between iron metabolism and

Immunity. Cell Death Discov. 10:3122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhang Z, Ji C, Wang YN, Liu S, Wang M, Xu

X and Zhang D: Maresin1 Suppresses High-Glucose-induced ferroptosis

in osteoblasts via NRF2 Activation in type 2 diabetic osteoporosis.

Cells. 11:25602022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kuang F, Liu J, Xie Y, Tang D and Kang R:

MGST1 is a redox-sensitive repressor of ferroptosis in pancreatic

cancer cells. Cell Chem Biol. 28:765–775.e5. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Fan Z, Wirth AK, Chen D, Wruck CJ, Rauh M,

Buchfelder M and Savaskan N: Nrf2-Keap1 pathway promotes cell

proliferation and diminishes ferroptosis. Oncogenesis. 6:e3712017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Rojo de la Vega M, Chapman E and Zhang DD:

NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell. 34:21–43. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chen Y, Jiang Z and Li X: New insights

into crosstalk between Nrf2 pathway and ferroptosis in lung

disease. Cell Death Dis. 15:8412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Živanović N, Lesjak M, Simin N and Srai

SKS: Beyond mortality: Exploring the influence of plant phenolics

on modulating Ferroptosis-A systematic review. Antioxidants

(Basel). 13:3342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhou HM, Liu Y, Shi F, Qiu HW, Li L, Shu

QP, Liu YY, Wang BQ, Gao M, Du RL, et al: CLK2 Regulates the

KEAP1/NRF2 and p53 pathways to suppress ferroptosis in colorectal

cancer. Cancer Res. 85:4734–4750. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Duan CH and Jiang LL: High-dose Yin Chen

combined with Western medicine for liver protection in treating

acute icteric hepatitis. Youjiang Med J. 3832001.

|

|

57

|

Chen GE and Huang XD: Large dose of Yin

Chen in the treatment of 84 cases of acute infectious icteric

hepatitis: A therapeutic effect observation. Jilin J Tradit Chin

Med. 191984.

|