Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is

defined as a heterogeneous lung condition characterized by airway

limitation and respiratory symptoms resulting from airway

inflammation and emphysema (1).

Although >3 million individuals succumb to COPD annually

worldwide, global mortality rates might be underestimated, as

one-third of patients with COPD succumb to cardiovascular diseases

(2). The persistent prevalence of

COPD solidifies its status as a substantial public health concern

globally. In patients with COPD, pulmonary gas exchange anomalies

and airway limitations are important pathophysiological

characteristics. Damage to the pulmonary air-blood barrier is a

notable factor in abnormal gas exchange, directly contributing to

inefficiencies in gas exchange, exacerbating dyspnea and worsening

respiratory symptoms (3).

The pulmonary air-blood barrier is the key element

of the lungs, serving as the site for the exchange of oxygen and

carbon dioxide between the human body and the external environment

(4). It primarily consists of

alveolar epithelium cells and capillary endothelial cells, either

directly connected or separated by interstitial tissue (5). This barrier acts as a defense against

pathogen invasion and is important for maintaining normal lung

physiological function. Various pathogenic factors, including

cigarette smoke, pollution gases, bacteria and viruses, can induce

damage to the air-blood barrier. This damage increases

permeability, aggravates lung tissue edema and triggers an

inflammatory response (6).

Cigarette smoke is recognized as the most common

risk factor for the occurrence and progression of COPD (7,8).

Previous studies have shown that cigarette smoke inhalation can

lead to autophagy impairment in pulmonary vascular endothelial

cells, initiating aggresome formation, resulting in inflammatory

responses and senescence that contribute to the decline of

pulmonary function in patients with severe COPD (9,10).

Additionally, the injury and death of alveolar epithelium cells

induced by cigarette smoke worsens emphysema and airway remodeling

in COPD, promoting the development of the disease (11).

Bacterial infections also play a notable role in

damaging the pulmonary air-blood barrier in patients with COPD. The

total number of pathogenic bacteria associates with decreased lung

function in patients with COPD (12). For instance, Klebsiella

pneumoniae induces apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells

through activation of the cytokine and IFN-γ-mediated signaling

pathways (13). Similarly,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection suppresses alveolar

epithelial cell autophagy, promotes inflammatory responses via

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2 suppression and

activates NF-κB (14).

Furthermore, bacterial infections induce rapid cell damage and

death of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells by activating

pro-inflammatory caspase-1 (15).

It is therefore important to elucidate the relationship between

cigarette smoke, bacterial infection and the pulmonary air-blood

barrier.

The MAPK signaling pathway plays a central role in

the occurrence and progression of COPD. Its abnormal activation

drives disease progression by regulating pathological processes

such as the inflammatory response, oxidative stress and mucus

hypersecretion (16).

Specifically, p38 MAPK upregulates the expression of TNF-α and IL-6

through phosphorylating the transcription factors cyclic

AMP-dependent transcription factor ATF-2 and ETS domain-containing

protein Elk-1, thereby recruiting neutrophils and monocytes for

infiltration into lung tissues (17). The JNK pathway promotes the

differentiation of T helper 17 cells, which in turn leads to the

release of IL-17 to activate p38 MAPK, forming a positive

inflammatory feedback loop (18).

In addition, p38 MAPK upregulates the expression of matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs) to degrade elastic fibers and collagen,

while simultaneously inhibiting the activity of TIMP, thus

facilitating the development of emphysema (19). In terms of mucus secretion,

cigarette smoke induces the transcription of the mucoprotein

(MUC)5AC gene by activating EGFR, which subsequently phosphorylates

ERK1/2 (20).

In the present study, a stable COPD rat model was

established through cigarette smoke inhalation and repetitive

bacterial infection to elucidate the effects of cigarette smoke and

bacterial infection on the pulmonary air-blood barrier and their

mechanisms of action. The present study evaluated pulmonary

function, pulmonary pathology, the ultrastructure of the air-blood

barrier and barrier integrity to assess injury in COPD rats.

Subsequently, inflammation, oxidative stress and the balance of

protease and antiprotease were compared between normal rats and

COPD model rats to clarify the potential mechanism of pulmonary

air-blood barrier damage caused by cigarette smoke inhalation and

repetitive bacterial infection.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

A total of 16 male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats aged 6–7

weeks (220±20 g; cat no. 110011211105823815) were purchased from

Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. All mice

were raised at a controlled temperature (25°C) and humidity (50%)

under a 12 h light/dark cycle and provided free access to food and

water. The experimental protocols were approved by the Experimental

Animal Care and Ethics Committees of the First Affiliated Hospital

at Henan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Zhengzhou,

China (approval no. YFYDW2019031). Klebsiella pneumoniae

(cat. no. 46117-5a1) was obtained from the National Center for

Medical Culture Collections (https://www.cmccb.org.cn/htmls/index.html). The

cigarettes (Hongqi Canal® Filter tip) were purchased

from Henan Tobacco Industry (https://www.hatic.com/zhongyanAdmin/html/sy/).

Establishment of a COPD rat model

The COPD rat model was established through cigarette

smoke inhalation and repetitive bacterial infection (21). A total of 16 SD rats were randomly

divided into the control group and the model group. From weeks 1–8,

rats in the model group were exposed to cigarette smoke (3,000±500

ppm) for 40 min twice daily, and were given intranasal instillation

of Klebsiella pneumoniae suspension (6×108

Cfu/ml; 0.1 ml) once every five days (22,23).

In the experiment, cigarettes were placed in a sealed cigarette

box. The concentration of smoke was controlled by adjusting the

number of lit cigarettes and a smoke sensor was used to monitor the

concentration, ensuring that the smoke concentration was maintained

at 3,000±500 ppm. Rats in the control group were exposed to normal

saline (0.1 ml) once every 5 days. At the end of week 8, rats were

anesthetized after intraperitoneal injection of 2% pentobarbital

sodium at 40 mg/kg. Subsequently, under deep anesthesia, rats were

euthanized by abdominal aortic blood collection to induce rapid

blood loss and immediate death, aiming to minimize animal

suffering. Irreversible death was confirmed through the combined

evaluation of three important parameters: i) The cessation of

spontaneous thoracic wall movements, indicating respiratory arrest;

ii) the absence of cardiac pulsation upon palpation of the

precordial region, confirming cardiac arrest; and iii) the presence

of mydriasis.

Pulmonary function measurement

Pulmonary function was measured for both groups of

rats every four weeks from weeks 0–8, assessing tidal volume (TV),

peak expiratory flow (PEF) and 50% TV expiratory flow (EF50) using

unrestrained pulmonary function testing plethysmographs (B&E

Teksystems Ltd; http://www.bandetek.com/wzsy).

Pulmonary tissue histopathology

The lung tissues were immersed in a 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 12 h.

Subsequently, the tissues were cut, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned. The 4 µm lung tissue sections were stained with

hematoxylin at room temperature for 2 min and eosin at room

temperature for 15 sec, and observed using a light microscope

(Olympus Corporation). Mean alveolar numbers (MAN) and mean linear

intercept (MLI) were determined to assess the degree of alveolar

damage. Under a light microscope (magnification, ×200), six visual

fields were captured in each slice, and the MAN and MLI in a fixed

area of the visual field were measured. A cross was marked under

the visual field and the number of alveolar septa on the cross was

counted. MLI (µm)=L/Ns, where Ns is the number of alveolar septa

and L is the total length of the cross. MAN (/mm2)=Na/A,

where Na is the number of pulmonary alveoli in each visual field

and A is the area of the visual field.

Ultrastructure of lung tissue

The lung tissue was sectioned into small pieces

measuring 1×1×1 mm, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 24 h

and further fixed with 1% osmic acid at 4°C for 2 h. The tissue was

then cut, embedded in Epon218 (SPI-Pon 812R Epoxy Resin Monomer;

cat. no. 25068-38-6; SPI Supplies) and sectioned at a thickness of

70 nm. The ultrastructure of the air-blood barrier, capillary

endothelium, type I alveolar epithelial cells (AT I) and type II

alveolar epithelial cells (AT II) was observed using a JEM-1400

transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd.). A total of three

fields of view were observed for each sample.

Immunohistochemical analysis

The lung tissues were immersed in a 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 12 h.

Subsequently, the tissues were cut, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned. Lung tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm, and

were dewaxed twice in xylene (20 min each), rehydrated through a

descending ethanol series (100, 95, 85 and 75%, 10 min each), and

rinsed in PBS three times for 5 min each. For antigen retrieval,

slides were immersed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated in a

microwave oven at high power for 5–8 min, followed by 5 min on low

power. The slides were then allowed to cool at room temperature for

40 min and rinsed again with PBS (three times, 5 min each).

Immunohistochemistry was conducted using a commercial

immunohistochemical kit (SA1022; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd.). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by

incubating the sections with a peroxidase blocking solution for 15

min, followed by three washes with PBS (3 min each). Non-specific

binding was blocked by incubating the slides in 5% BSA (cat. no.

A8020; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C

for 1 h. After blocking, the sections were incubated overnight at

4°C with the following primary antibodies: MUC5AC (1:500; cat. no.

85868-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), MUC5B (1:500; cat. no.

28118-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), zonula occludens (ZO)-1

(1:200; cat. no. AF5145; Affinity Biosciences) and claudin-5

(1:200; cat. no. AF5216; Affinity Biosciences). The following day,

the sections were washed three times in PBS (3 min each), then

incubated at 37°C for 1 h with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

secondary antibody provided in commercial immunohistochemical kit

(cat. no. SA1022; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.). Signal

development was performed using the metal-enhanced DAB substrate

kit (cat. no. AR1027; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) for

10 min at room temperature, followed by rinsing in distilled water.

Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 2 min with room

temperature and washed under running tap water for 10 min.

Differentiation was carried out in 1% hydrochloric acid ethanol for

3 sec, followed by an additional rinse under running water for 3

min. The stained slides were then dehydrated in ascending

concentrations of ethanol (75, 85, 95 and 100%, 5 min each),

cleared in xylene twice (5 min each) and mounted with neutral

resin. All stained sections were examined using a light microscope

(Olympus Corporation) for morphological analysis was performed

using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Immunofluorescence of lung tissue

The lung tissues were immersed in a 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 12 h.

Subsequently, the tissues were cut, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned. Lung tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm, and

were dewaxed twice in xylene (20 min each), rehydrated through a

descending ethanol series (100, 95, 85 and 75%, 10 min each), and

rinsed in PBS three times for 5 min each. For antigen retrieval,

slides were immersed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated in a

microwave oven at high power for 5–8 min, followed by 5 min on low

power. The slides were then allowed to cool at room temperature for

40 min and rinsed again with PBS (three times, 5 min each). The

slices were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, followed by

blocking in 3% BSA for 1 h. The slices were incubated with

target-specific primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: aquaporin

(AQP)-5 (1:1,000; cat. no. 20334-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

surfactant protein-D (SP-D; 1:1,000; cat. no. DF13601; Affinity

Biosciences), CD31 (1:1,000; cat. no. AF6191; Affinity

Biosciences). After thorough PBS washing, the specimens were

exposed to fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000;

Cy3-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H+L); cat. no. SA00009-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.; 1:1,000; Fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG(H+L); cat. no. SA00003-1; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) in a dark place for 1 h at room temperature. Following three

additional PBS washes (3 times, 5 min each), the coverslips were

mounted onto glass slides with Fluoroshield medium containing DAPI.

Finally, a laser confocal microscope (LSM700; Carl Zeiss AG) was

used for detection.

Alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff

(AB-PAS) staining

The lung tissues were immersed in a 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 12 h.

Subsequently, the tissues were cut, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned. The 4 µm lung tissue slices were stained with Alcian

Blue at room temperature for 15 min and with Schiff at room

temperature for 15 min. The lung tissue slices were observed using

a light microscope (Olympus Corporation). Positive staining was

considered indicative of goblet cells.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

Lung tissue was homogenized in a phosphate-buffered

saline solution and centrifuged at 12,880 × g and 4°C for 10 min to

collect the supernatant. The secretion of IL-6 (Rat IL-6 ELISA Kit;

cat. no. E-EL-R0015; Elabscience Bionovation Inc.), IL-10 (Rat

IL-10 ELISA Kit; cat. no. E-EL-R0016; Elabscience Bionovation

Inc.), malondialdehyde (MDA) (MDA assay kit; cat. no. A003-1-2;

Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), total superoxide

dismutase (T-SOD) (SOD assay kit; cat. no. A001-3-2; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), MMP-9 (Rat MMP-9 ELISA Kit;

cat. no. E-EL-R3021; Elabscience Bionovation Inc.) and tissue

Inhibitors of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1 ELISA Kit; cat. no.

E-EL-R0540; Elabscience Bionovation Inc.) in the lung tissue

homogenate was measured using ELISA kits, following the

manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

The protein levels of GAPDH (1:5,000, GAPDH

Polyclonal antibody, 10494-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), ZO-1

(1:1,000; cat. no. AF5145; Affinity Biosciences), SP-D (1:1,000;

cat. no. DF13601; Affinity Biosciences), claudin-5 (1:1,000; cat.

no. AF5216; Affinity Biosciences), angiopoietin (Ang)-2 (1:1,000;

cat. no. DF6137; Affinity Biosciences), p-p38 (1:1,000; cat. no.

AF4001; Affinity Biosciences), p38 (1:1,000, p38 MAPK Antibody,

AF6456; Affinity Biosciences), p-ERK (1:1,000; cat. no. AF1015;

Affinity Biosciences), ERK (1:1,000; cat. no. AF0155; Affinity

Biosciences), p-JNK (1:1,000; cat. no. AF3318; Affinity

Biosciences), JNK (1:1,000; cat. no. AF6318; Affinity Biosciences),

p-p65 (1:1,000; cat. no. AF2006; Affinity Biosciences), p65

(1:1,000; cat. no. AF5006; Affinity Biosciences), p-IκBα (1:1,000;

cat. no. AF2002; Affinity Biosciences) and IκBα (1:1,000; cat. no.

AF5002; Affinity Biosciences) in lung tissue were determined by

western blotting. Rat lung tissue (10 mg) was homogenized in 150 µl

of 1X RIPA Buffer (cat. no. R0020; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), followed by centrifugation at 12,880 × g and

4°C for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The protein

concentration of the lung tissue homogenate was determined via the

BCA assay (BCA Protein Assay Kit; cat. no. PC0020; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The 30–40 µg lung tissue

protein samples were divided by 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and

metastasized to PVDF membranes. Then 5% skimmed milk was used to

block the PVDF at room temperature for 1 h. Next, membranes were

incubated with their primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, and

secondary antibodies (1:5,000, HRP-conjugated Rabbit Anti-Goat

IgG(H+L); cat. no. SA00001-4; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at room

temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed with 1X TBST with

0.1% Tween. The membranes were visualized using the Bio-Rad Imaging

System (ChemiDoc MP; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using SPSS v21.0

(IBM Corp.). Comparisons among groups were performed by unpaired

t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. If the data followed a normal

distribution, a Student's t-test was performed. If the data did not

follow a normal distribution, Mann-Whitney U test was used. All

experiments were independently repeated ≥3 times to ensure

reproducibility. The mean ± standard error of the mean was used for

data presentation. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

Decline of pulmonary function and

damage of pulmonary pathology are induced by cigarette smoke

combined with Klebsiella pneumoniae infection

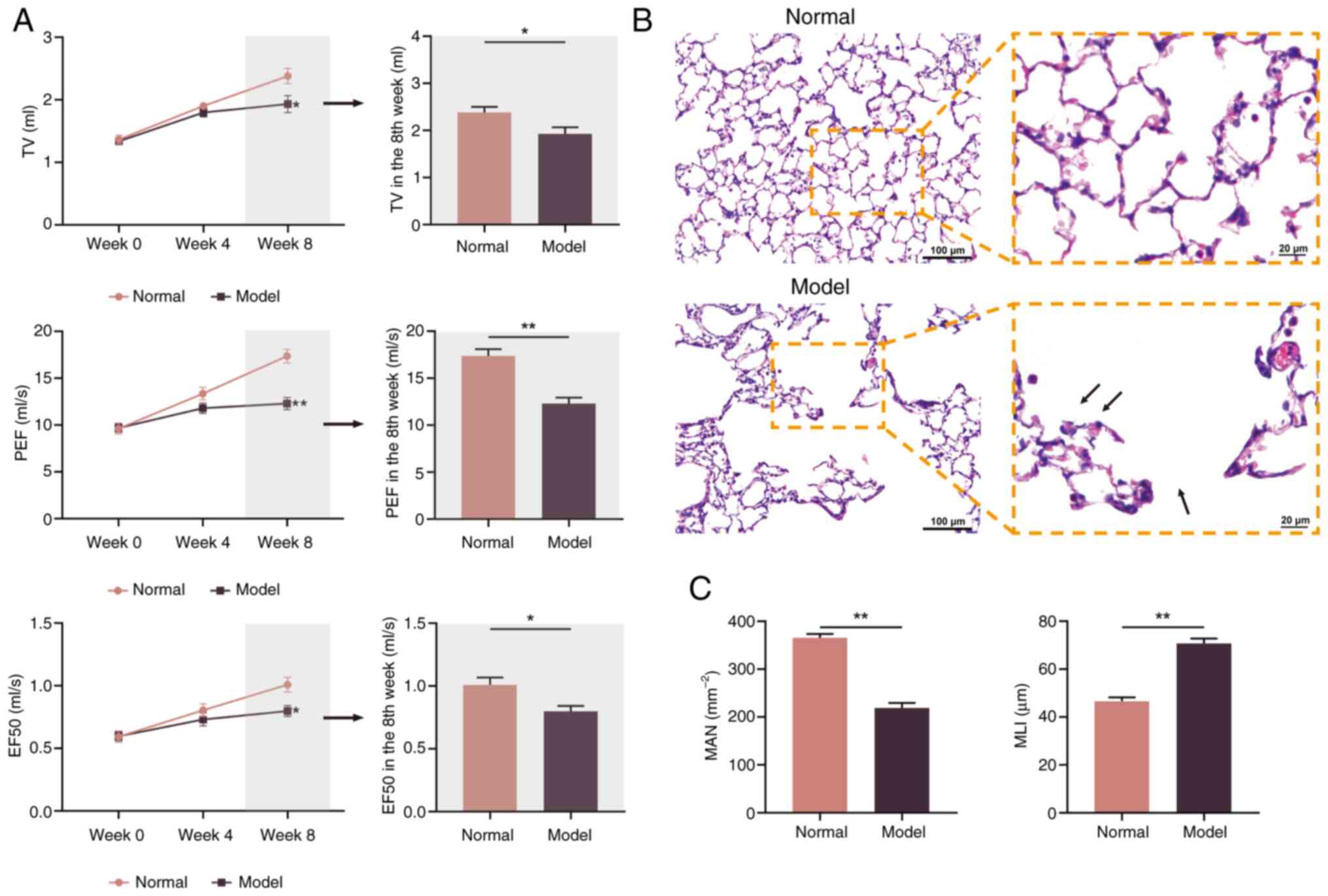

TV, PEF and EF50 are important indicators reflecting

the degree of dyspnea (24). TV,

PEF and EF50 significantly decreased with prolonged exposure to

cigarette smoke and bacterial infection (Fig. 1A). By week 8, these parameters

significantly decreased in COPD rats compared with normal rats

(P<0.05 and P<0.01).

MAN and MLI were used to assess the degree of

alveolar damage. By week 8, there was a notable increase in

alveolar rupture, fusion and thickening of the alveolar wall in

COPD rats compared with normal rats (Fig. 1B). The significant decrease in MAN

and increase in MLI observed in COPD rats compared with normal rats

indicated that pulmonary damage had occurred (both P<0.01;

Fig. 1C).

Cigarette smoke combined with

Klebsiella pneumoniae infection induces structural and functional

impairment of the air-blood barrier

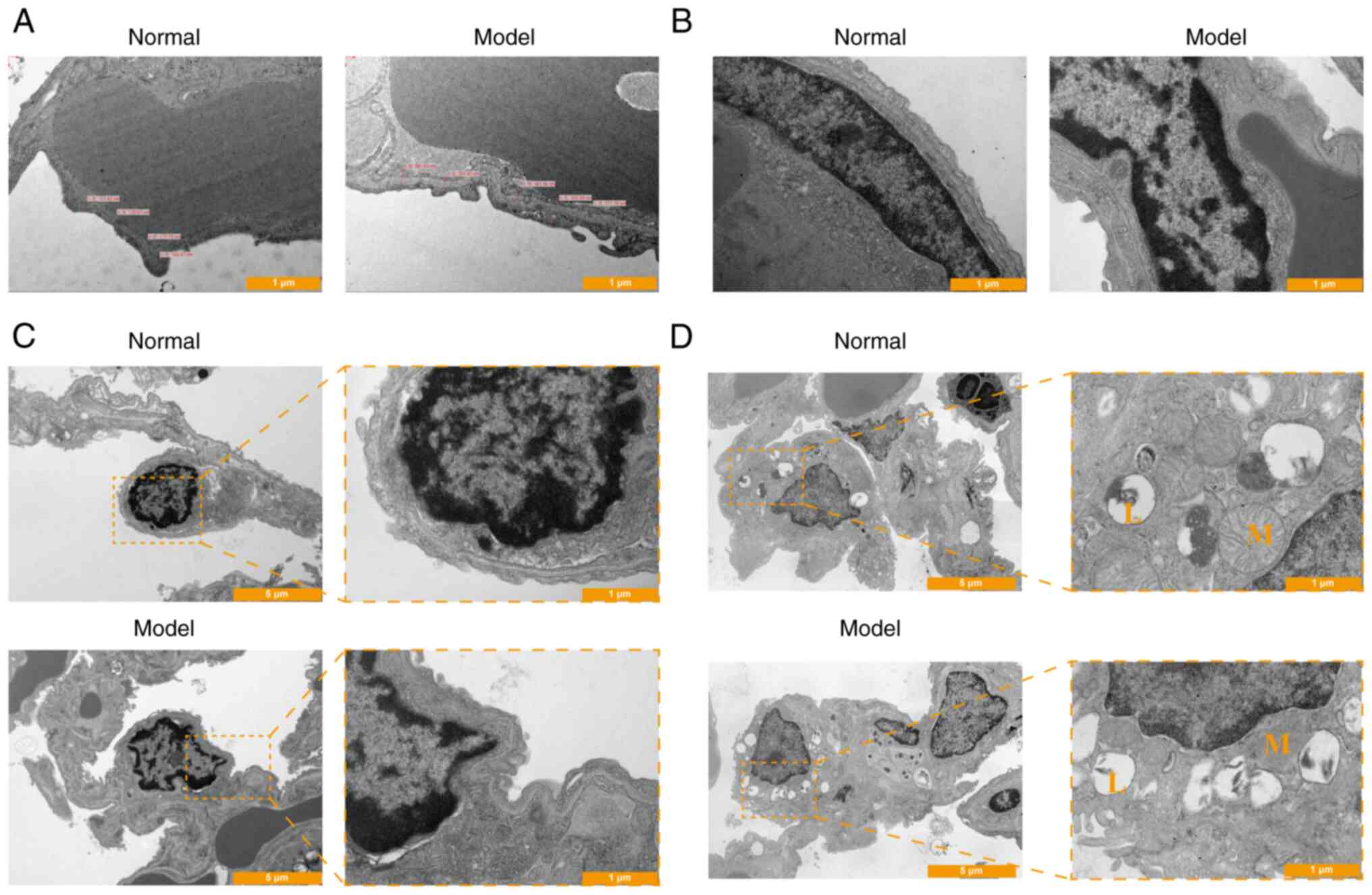

In week 8, the structural integrity of the

respiratory membrane in normal rats exhibited uniform thickness

with a clear structure (Fig. 2A).

The capillary endothelial cells appeared flat, with regular nuclear

shapes and uniform cell membrane thickness (Fig. 2B). Conversely, in the model group,

the present study observed unevenness in the structure of the

respiratory membrane, with blurred edges and noticeable thickening

(Fig. 2A). The capillary

endothelial space widened in the COPD model, displaying disordered

cell arrangement, irregular cell shapes, fuzzy membrane structures,

unclear edges and occasional cell debris (Fig. 2B).

The structure of AT I in normal rats was intact,

with a smooth surface, a thicker nucleus-containing part protruding

into the alveolar cavity and a thin non-nuclear cytoplasm

containing clear ribosomes and numerous pinocytic vesicles. In

model rats, the structure of AT I was blurred, with unclear edges,

a rough surface and a reduced number of vesicles for pinocytosis

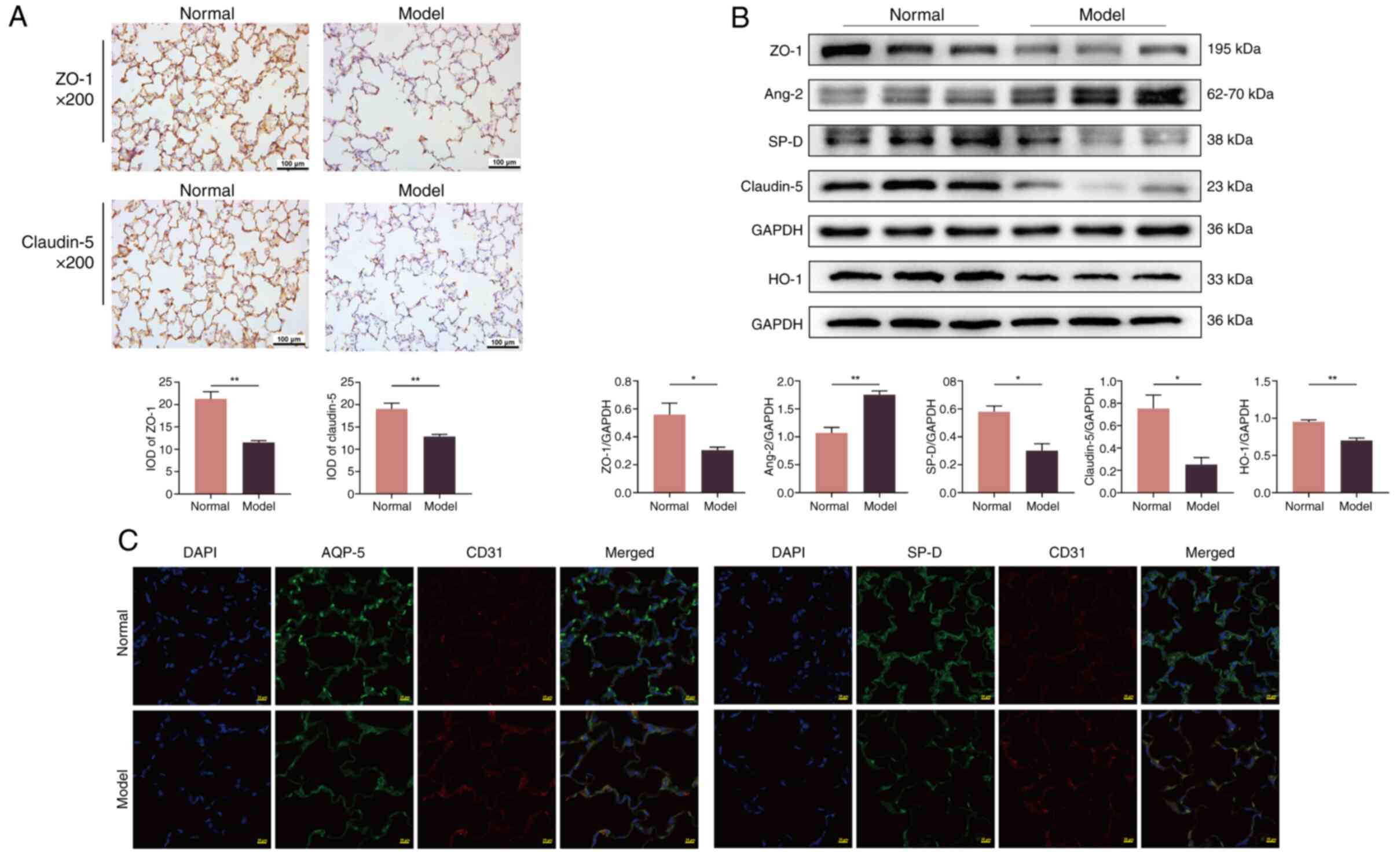

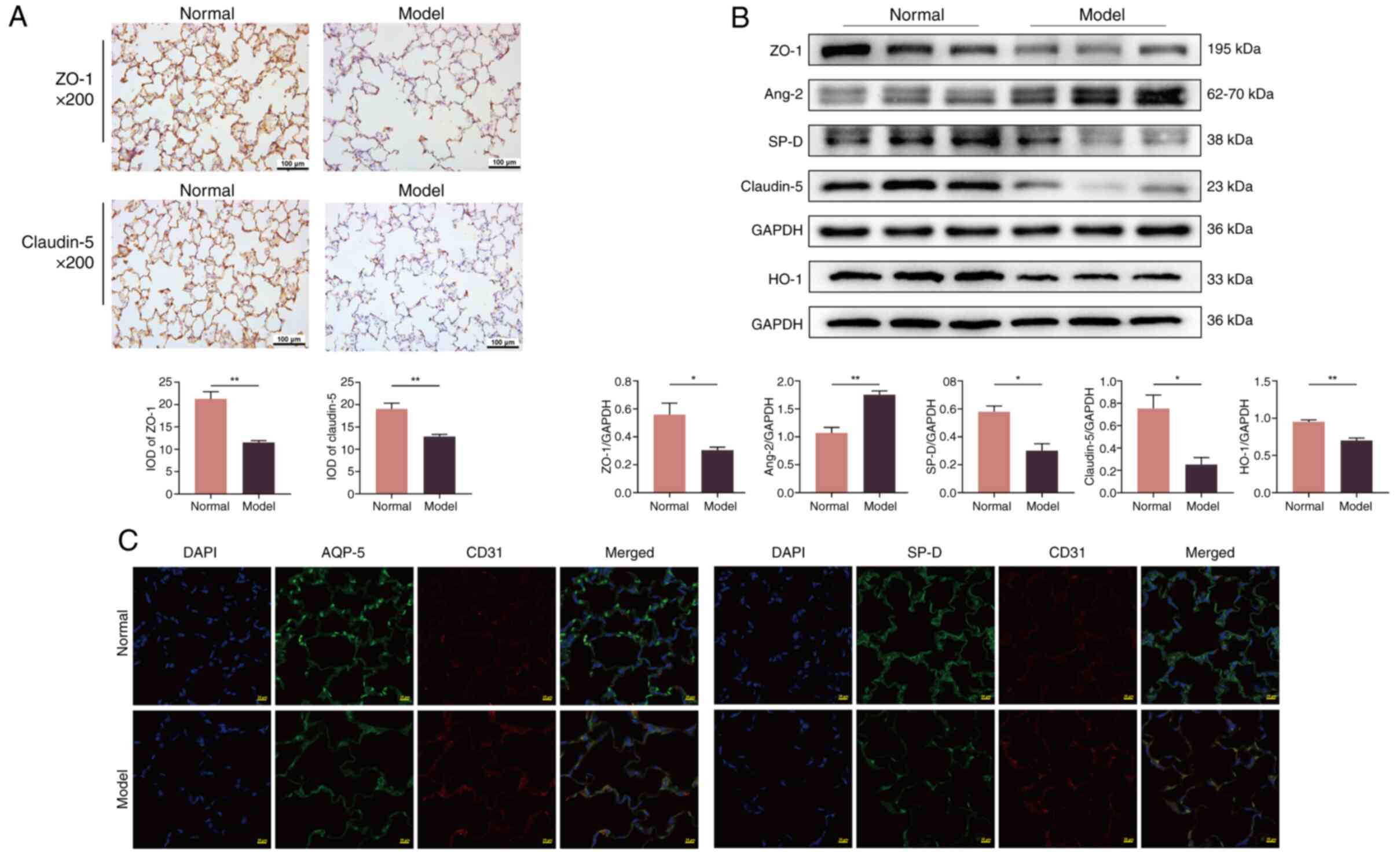

(Fig. 2C). Immunohistochemical

analysis revealed a significant decrease in the expression of ZO-1

and claudin-5 in COPD rats compared with normal rats (P<0.01;

Fig. 3A). This low expression was

further supported by western blot analysis (P<0.05; Fig. 3B), indicating that cigarette smoke

and bacterial infection can damage the tight connections within the

air-blood barrier. These results suggested a notable increase in

structural damage to the air-blood barrier in COPD rats compared

with normal rats.

| Figure 3.Injury of the air-blood barrier

induced in all groups. (A) The expression level of ZO-1 and

claudin-5 in the lung tissue of rats was tested using

immunohistochemistry (×200 magnification). The values are expressed

as mean ± SE; (n=8). **P<0.01 vs. normal group. (B) Protein

expression of ZO-1, claudin-5, SP-D, HO-1 and Ang-2 in the lung

tissue tested via western blotting. The values are expressed as

mean ± SE; (n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. normal group. (C)

The expression level of AQP-5, SP-D and CD31 in the lung tissue

tested using immunofluorescence (×200 magnification). ZO-1, zonula

occludens-1; SP-D, surfactant protein-D; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1;

Ang-2, angiopoietin 2; AQP-5, aquaporin-5; IOD, integrated optical

density. |

AT II had a clear structure in normal rats, with

neatly arranged villi, abundant lamellar bodies, numerous

mitochondria and well-defined mitochondrial ridges. Conversely, in

model rats, the structure of AT II was unclear, with lamellar

bodies detaching in the form of vacuoles and decreasing in number.

Additionally, mitochondria showed signs of pyknosis or swelling,

and the mitochondrial ridges appeared blurred (Fig. 2D).

The fluorescence intensity of AQP-5 and SP-D

markedly decreased in COPD rats compared with the normal group,

while that of CD31 increased notably (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the protein

expression of SP-D (P<0.05) and heme oxygenase-1 (P<0.01)

significantly decreased, and the expression of Ang-2 increased

significantly (P<0.01) in COPD rats compared with normal rats

(Fig. 3B). These findings

indicated a significant decrease in the function of the air-blood

barrier in COPD rats compared with normal rats.

Cigarette smoke combined with

Klebsiella pneumoniae infection induces mucus hypersecretion,

inflammation and oxidative stress

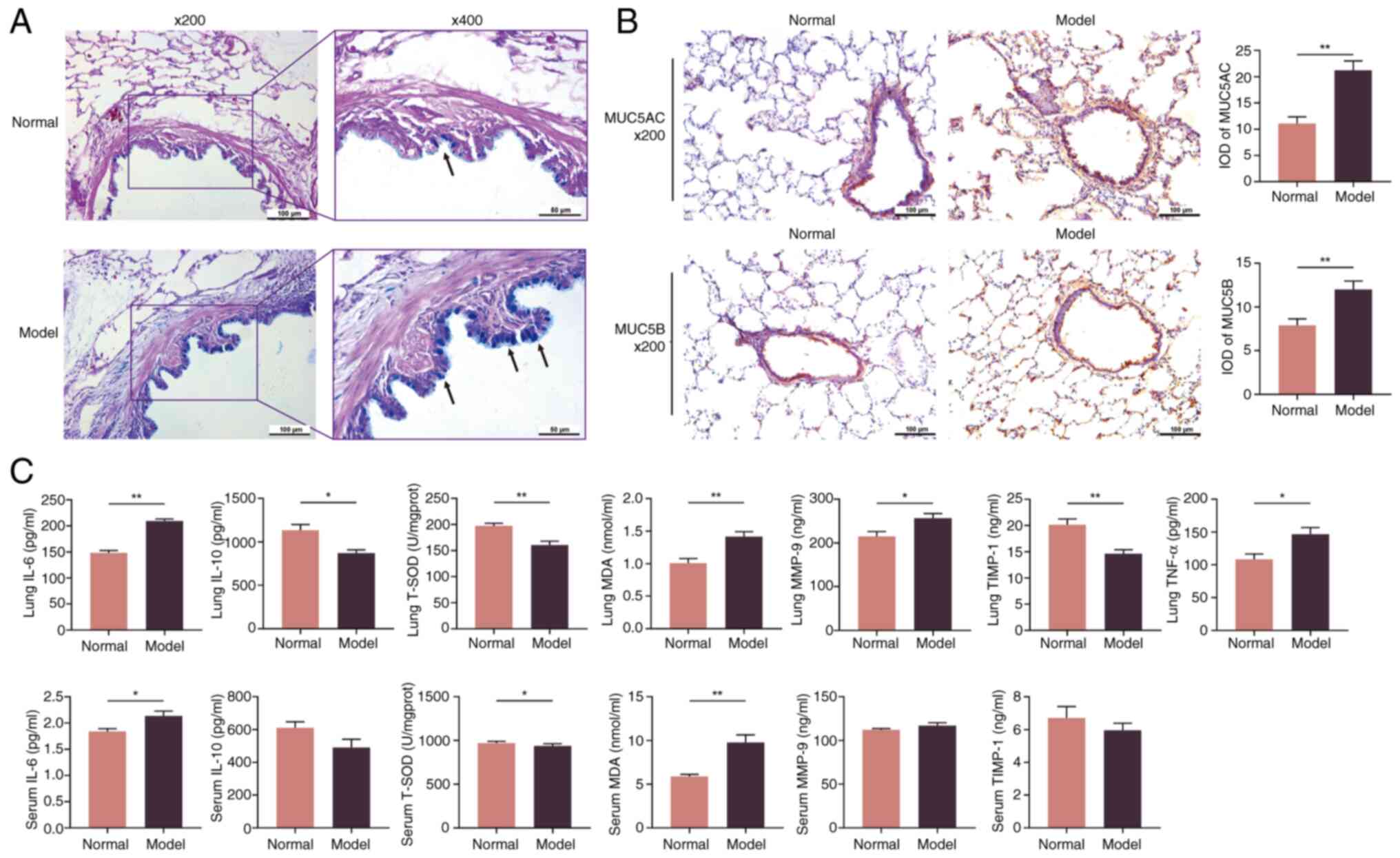

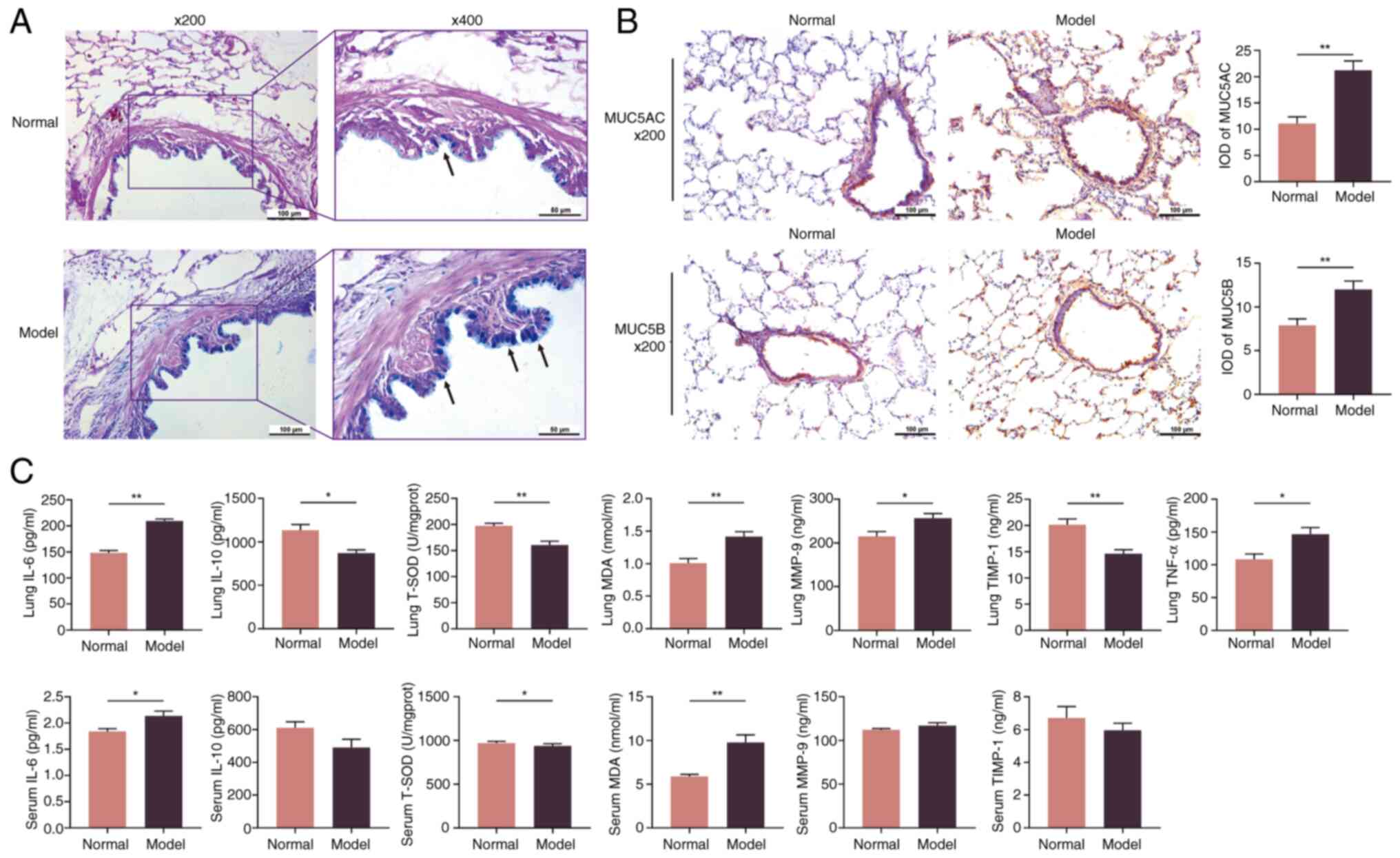

In COPD rats, positive AB-PAS staining markedly

increased in the airways compared with normal rats, indicating

goblet cell proliferation (Fig.

4A). The expression of MUC5AC and MUC5B was significantly

elevated in COPD rats compared with normal rats (Fig. 4B). COPD rats also exhibited an

inflammatory response induced by cigarette smoke and bacterial

infection. When compared with normal rats, the secretion of IL-6

and TNF-α significantly increased in the lung tissue and serum of

COPD rats (P<0.05 and P<0.01), while that of IL-10 decreased

significantly in the lung tissue of COPD rats (P<0.05).

Similarly, the expression of MMP-9 increased and TIMP-1 decreased

significantly in the lung tissue of COPD rats (P<0.05 and

P<0.01), indicating abnormal extracellular matrix deposition and

the disruption of organizational structure.

| Figure 4.Injury of mucus hypersecretion and

oxidative damage in all groups. (A) AB-PAS staining images of the

airway in all groups (AB-PAS; ×200 magnification and ×400

magnification). Arrows indicate goblet cells. (B) The expression

level of MUC5AC and MUC5B in the airway tested using

immunohistochemistry (×200 magnification). (C) The expression of

IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, T-SOD, MDA, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in lung tissue and

serum of rats in all groups. The values are expressed as mean ± SE;

(n=8). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. normal group. AB-PAS, Alcian

blue-periodic acid-schiff; MUC5AC, mucoprotein-5AC; MUC5B,

mucoprotein-5B; T-SOD, total superoxide dismutase; MDA,

malondialdehyde; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase 9; TIMP-1, tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinases 2; IOD, integrated optical

density. |

Furthermore, oxidative stress was enhanced by

cigarette smoke and bacterial infection in COPD rats. The enzymatic

activity of T-SOD significantly decreased in both the lungs and

serum, while the expression of MDA significantly increased in COPD

rats compared with normal rats (P<0.05 and P<0.01) (Fig. 4C).

Cigarette smoke combined with

Klebsiella pneumoniae infection induces impairment of the air-blood

barrier via the MAPK/NF-κB/IκBα pathway

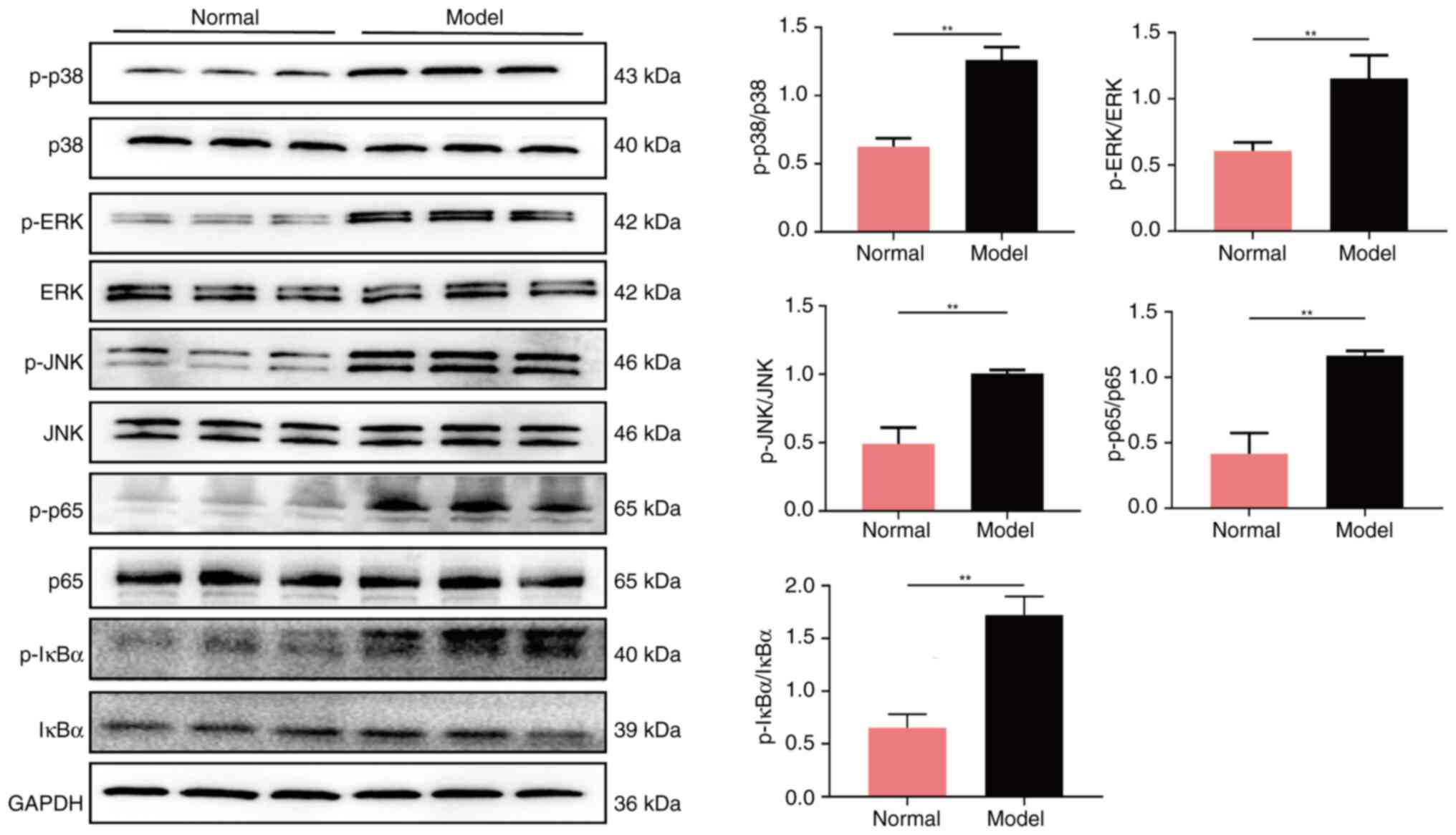

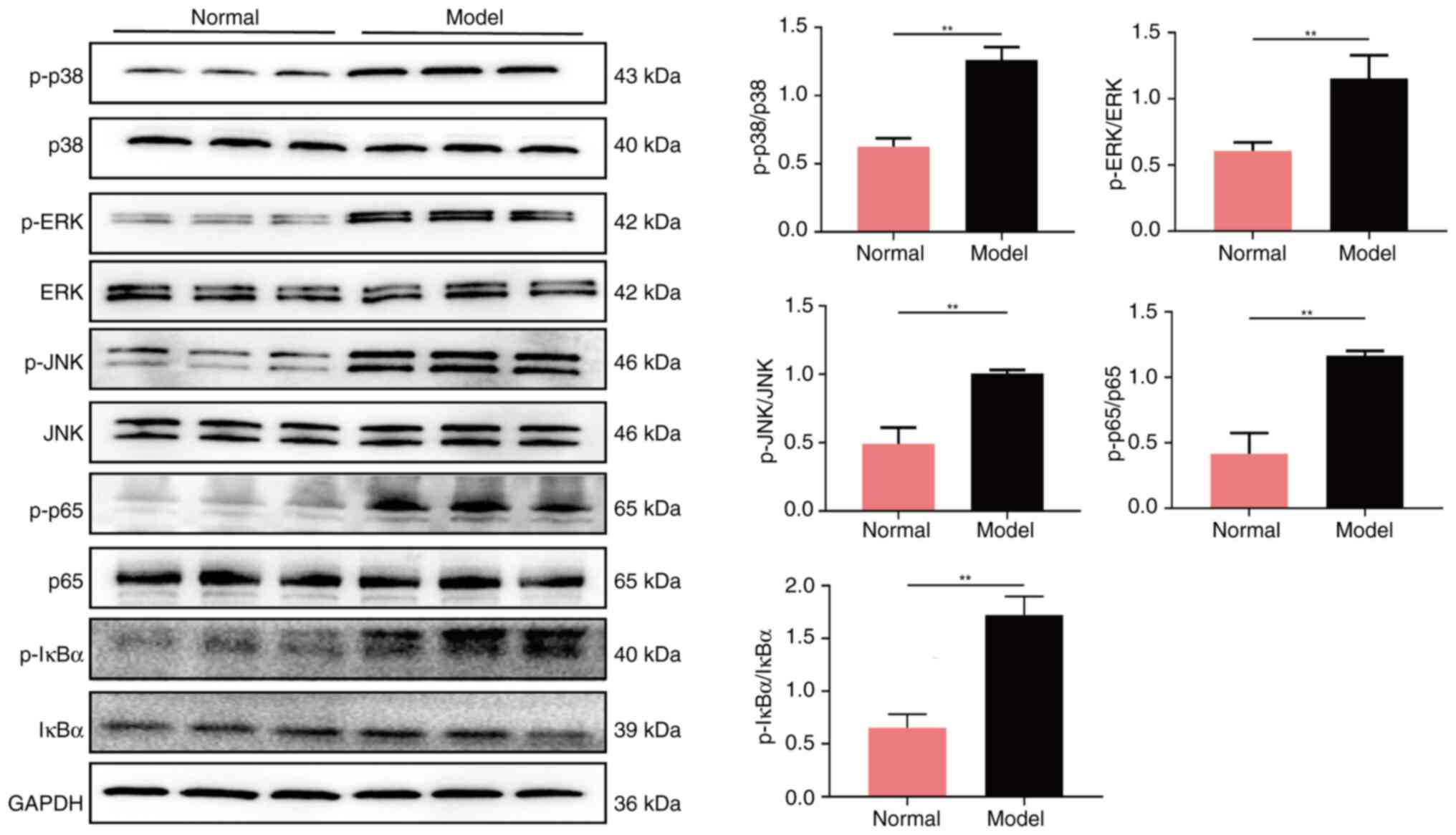

When compared with the normal group of rats, the

combination of cigarette smoke and Klebsiella pneumoniae

infection resulted in an elevation in the levels of p-p38, p-ERK,

p-JNK, p-p65 and p-IκBα proteins (all P<0.01), while having no

notable effect on the levels of total p38, ERK, JNK, p65 and IκBα

proteins (Fig. 5). This outcome

suggested that the combination of cigarette smoke and Klebsiella

pneumoniae infection may have led to damage to the air-blood

barrier by activating the MAPK/NF-κB/IκBα signaling pathway,

thereby promoting inflammatory responses and oxidative stress.

| Figure 5.Protein expression of p-p38, p38,

p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, p-p65, p65, p-IκBα and IκBα in the lung

tissue tested using western blot analysis. **P<0.01 vs. normal

group. JNK, Janus kinase; p-, phosphorylated. |

Discussion

The air-blood barrier, also known as the

alveolar-capillary barrier, is an important component of the lung,

facilitating the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the

human body and the environment (25,26).

In the present study, a COPD rat model was established through

cigarette smoke inhalation and repetitive bacterial infection.

The pulmonary air-blood barrier plays a notable role

in gas and substance exchange, and its destruction leads to

irreversible and notable damage to respiratory function (27). The findings of the present study

revealed that cigarette smoke and bacterial infection resulted in

declined pulmonary function in model rats via deterioration in the

diffusion function of the alveolar-capillary barrier. The

heightened permeability of the pulmonary air-blood barrier may

contribute to alveolar edema, initiating a detrimental cycle of

tissue injury and disrupted balance of substance transport and gas

exchange (27).

Furthermore, the present study observed pathological

damage in the lungs of COPD rats, including alveolar rupture and

the formation of air cavities, which were indicative of compromised

structural integrity of the alveolar-capillary barrier. The

alveolar epithelial barrier, primarily composed of AT I and AT II

arranged in a continuous monolayer and interconnected by tight

junctions (28), plays an

important role in gas exchange. Conversely, the pulmonary

endothelial barrier, comprising endothelial cells, regulates the

entry of fluid and inflammatory components into the interstitium

(29). These barriers constitute

the pulmonary air-blood barrier. The hyperinflammatory environment

of the alveoli, including inflammatory cells, pro-inflammatory

cytokines, chemokines and other inflammatory mediators, can damage

the pulmonary epithelium and endothelium, leading to cell apoptosis

and disruption of intercellular junctions (30).

Additionally, the present study observed incomplete

structures of AT I and AT II in COPD rats. Furthermore, the

respiratory membrane in COPD rats showed marked thickening compared

with normal rats. Therefore, these structural damages to AT I, AT

II and the respiratory membrane contributed to the inefficiency of

gas exchange resulting from cigarette smoke inhalation and

repetitive bacterial infection. Additionally, the present study

observed mitochondrial swelling in the ultrastructure of alveolar

epithelial cells from COPD rats, which suggested that mitochondrial

dysfunction may have played an important role in the impairment of

the pulmonary air-blood barrier. However, the present study did not

further detect or evaluate mitochondrial function, nor analyze its

relationship with the impairment of the pulmonary air-blood

barrier. This is one of the limitations of the present study. In

our subsequent study, we will further detect reactive oxygen

species, mitochondrial respiratory chain synthases and apoptosis in

alveolar epithelial cells, aiming to explore how mitochondrial

damage and apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells affect the

impairment of the pulmonary air-blood barrier and gas exchange in

COPD rats.

The functionality of the air-blood barrier relies on

the normal structure and properties of alveolar epithelial cells

and pulmonary capillary endothelial cells (PCECs) (31,32).

A previous study confirmed that injury to AT II cells induces

thickening of the air-blood barrier and damages intercellular

junctions, even in the presence of normal total intracellular

surfactant pools (33). Similarly,

endothelial function plays a notable role in maintaining normal

lung function by regulating osmotic pressure and barrier function

(34,35). In the present study, damage to

alveolar epithelial cells was also observed.

AQPs, a type of transmembrane channel protein

facilitating water transfer (36),

includes the protein AQP-5, a marker for AT I. AQP-5 contributes to

ion transport and the maintenance of lung fluid balance in AT I,

thereby preventing barrier disruption and edema (37). SP-D, synthesized and secreted by AT

II, is involved in the innate immune defense of the lung (38). SP-D aids in clearing infectious

pathogens and modulating the immune response by regulating multiple

inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the toll-like receptor

(TLR) 4 signaling pathway (39).

The present study aligns with these findings, as a decline in the

expression of AQP-5 and SP-D was observed, signifying the

hypofunctionality of AT I and AT II.

CD31, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of

cell adhesion molecules, serves as a molecular marker for PCECs. It

primarily inhibits normal cell apoptosis and participates in

platelet adhesion and aggregation in PCECs (40). Ang-2 is a ligand protein in the Ang

signaling pathway, belonging to a glycoprotein family that signals

through the transmembrane tyrosine-kinase-2 receptor (41). Ang-2 manifests notable antagonistic

effects to Ang-1 in pathological states, leading to vascular

homeostasis imbalance, seepage and the accelerated, abnormal

proliferation of PCECs (42). The

findings of the present study revealed reduced expression of CD31

and an increased expression of Ang-2 induced by cigarette smoke

inhalation and repetitive bacterial infection, indicating a

decrease in the functionality of PCECs.

Cellular connections are important indicators for

assessing the function and structure of the air-blood barrier.

ZO-1, a tight junction protein predominantly distributed between

epithelia and endothelia, regulates the paracellular permeability

of these cells (43).

ZO-1-deficient cells are capable of assembling functional barriers

under low-tension conditions, yet their tight junctions remain

impaired, characterized by a marked reduction and discontinuous

distribution in the recruitment of junctional components (44). Claudin-5, a member of the claudin

family, is the main structural determinant of the paracellular

endothelial barrier (45).

Claudin-5 promotes the sealing of tight junctions, reducing vessel

permeability and enhancing endothelial barrier function (46). In the present study, the

expressions of ZO-1 and claudin-5 were significantly decreased in

COPD rats compared with normal rats. Therefore, the present study

considered that not only the function but also the structure of the

lung air-blood barrier was compromised in COPD rats due to

cigarette smoke inhalation and repetitive bacterial infection.

Inflammation plays an important role in promoting

the pathological process of air-blood barrier injury, involving the

recruitment of numerous inflammatory cells and secretion of

inflammatory mediators, ultimately resulting in lung air-blood

barrier damage and notable inflammation in the lung (47,48).

Previous studies have demonstrated that regulating TLR4/NF-κB

signaling pathway activation can suppress the production of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus inhibiting the inflammatory

response and protecting the air-blood barrier (49,50).

Consistent with these findings, the results of the present study

revealed a strong inflammatory response, characterized by elevated

IL-6 and diminished IL-10 secretion, exacerbated by cigarette smoke

and bacterial infection, contributing to air-blood barrier injury.

Furthermore, the present study discovered mucus hypersecretion in

COPD rats, exemplified by MUC5AC and MUC5B, attributable to

cigarette smoke and bacterial infection. This may have exacerbated

the inflammatory response, further damaging the air-blood

barrier.

Another study verified that the inhibition of MMP

activity due to neutrophil depletion was associated with a

decreased insult to junction proteins and the alveolar-capillary

barrier (51). Furthermore, the

present study evaluated the expression of MMP-9 and TIMP-1,

demonstrating the high expression of MMP-9 and low expression of

TIMP-1 in lung tissue, although these changes in the serum were not

statistically significant. The abnormal expression of MMP-9 and

TIMP-1 in model rats suggested an imbalance of protease and

antiprotease, potentially induced by the inflammatory response in

the lung. Additionally, an imbalance of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 leads to

the rupture of alveoli and the occurrence of emphysema, resulting

in a decline in the diffusion function of the air-blood barrier

(52).

Oxidative stress is another important cause of lung

air-blood barrier damage. A study by Jia et al (25) reported particulate matter <2.5

µm (PM2.5)-induced air-blood barrier dysfunction. The study

observed that reducing oxidative stress via treatment with

N-acetyl-L-cysteine in a mouse model exposed to PM2.5 improved

air-blood barrier function and alleviated the effects of PM2.5. The

present study measured the enzymatic activity of T-SOD and the

protein level of MDA. The enzymatic activity of T-SOD significantly

decreased, and the protein level of MDA significantly increased in

rats after model establishment with cigarette smoke and bacterial

infection. These results indicate that oxidative stress, resulting

from cigarette smoke inhalation and repetitive bacterial infection,

was a notable cause of lung air-blood barrier damage. Therefore,

lung air-blood barrier damage caused by cigarette smoke and

bacterial infection predominantly resulted from an inflammatory

response, protease/antiprotease imbalance and oxidative stress.

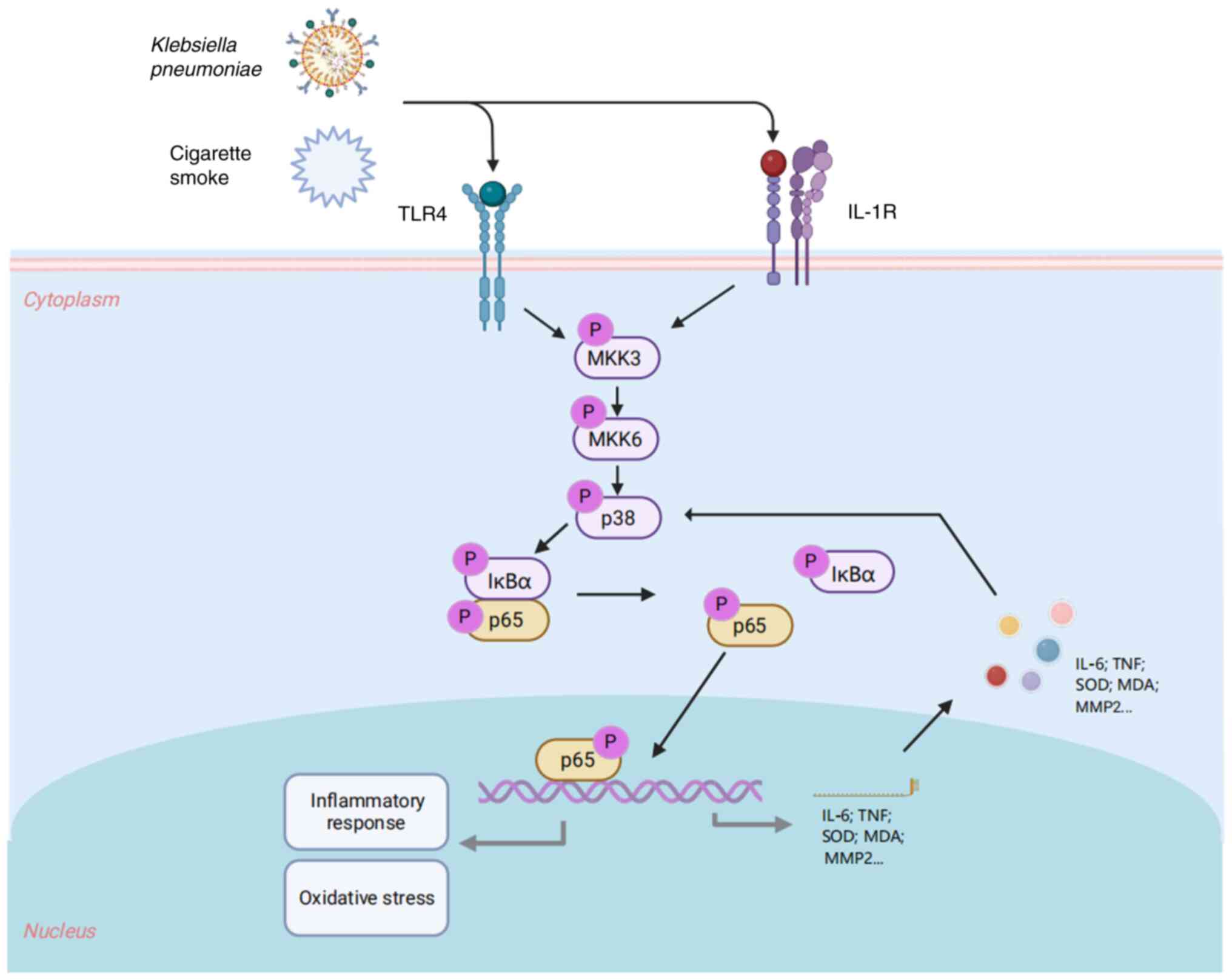

In COPD, stimuli such as cigarette smoke and

lipopolysaccharides can activate pathways such as the EGFR/MAPK and

NF-κB pathways in airway epithelial cells, which induce goblet cell

hyperplasia and ciliary epithelial cell dysfunction. These changes

lead to excessive synthesis and impaired clearance of mucins,

directly causing airway obstruction and impairing the gas exchange

function of the pulmonary air-blood barrier (53). Additionally, the viscous and

excessive mucus facilitates bacterial colonization and accumulation

of inflammatory factors, which exacerbate chronic inflammation and

directly impair the structural integrity of the pulmonary air-blood

barrier (54). In the present

study, hypersecretion of airway mucus was also observed, which led

to the impairment of the pulmonary air-blood barrier.

In the present study, a combined approach of 8 weeks

of continuous cigarette smoke inhalation and repeated Klebsiella

pneumoniae infection was adopted. This approach simulated the

pathological environment of long-term smoke exposure and repeated

bacterial infection in patients with COPD, successfully

establishing a stable COPD rat model and providing a more

clinically relevant experimental vehicle for subsequent research.

Furthermore, the present study focused on the pulmonary air-blood

barrier. The present study conducted comprehensive analysis

covering the ultrastructural features and structural and functional

proteins of the barrier, fully elucidating the entire process from

structural damage to functional decline of the pulmonary air-blood

barrier. Furthermore, the present study provided evidence that the

combined effect of cigarette smoke and Klebsiella pneumoniae

infection activated the MAPK/NF-κB/IκBα signaling pathway. This

activation further regulated inflammatory responses, oxidative

stress and protease-antiprotease imbalance, ultimately inducing

damage to the pulmonary air-blood barrier.

Although the present study provided notable insights

into understanding the roles of cigarette smoke and bacterial

infection in the progression of COPD, the conclusions of the

present study still require further evidence to support these

conclusions. Primarily, the present study did not employ cigarette

smoke of different concentrations, different types of bacteria or

varying exposure durations to verify their effects. Furthermore,

the damage to the pulmonary air-blood barrier may have involved

multiple mechanisms; the application of multi-omics techniques can

aid in comprehensively dissecting these underlying mechanisms,

which will also serve as one of the starting points for our future

research.

Summarily, in the present study, a COPD rat model

was established through cigarette smoke inhalation and repetitive

bacterial infection. The pulmonary function and histopathology of

pulmonary tissues deteriorated in COPD model rats. The

ultrastructure of the air-blood barrier was compromised and the

structure and function of ATs and PCECs were impaired. Furthermore,

the secretion of inflammatory factors and mucus increased in model

rats due to cigarette smoke and bacterial infection. Similarly, a

protease/antiprotease imbalance and oxidative stress were observed

in COPD rats, resulting in damage to the lung air-blood barrier. In

summary, the function and structure of the air-blood barrier were

impaired in COPD model rats due to cigarette smoke inhalation and

repetitive bacterial infection, with underlying mechanisms likely

related to inflammation and oxidative stress regulated by the

MAPK/NF-κB/IκBα signaling pathway (Fig. 6).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Key Research and

Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFC3502600) and the

National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant nos. 82074406

and 81973822).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YT, KX, and RL wrote the manuscript and conducted

the experiments. KL, XS and YL analyzed the results. YZ and ZQ

performed immunofluorescence and visualized all results. HD and XL

designed experiment and revised the manuscript. YT and XL confirmed

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the

Experimental Animal Care and Ethics Committees of the First

Affiliated Hospital at Henan University of Traditional Chinese

Medicine, Zhengzhou, China (approval no. YFYDW2019031).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive

Lung Disease, . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management,

prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2023.Available

from. http://www.goldcopd.org./

|

|

2

|

Rabe KF and Watz H: Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. Lancet. 389:1931–1940. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Neder JA, Kirby M, Santyr G, Pourafkari M,

Smyth R, Phillips DB, Crinion S, de-Torres JP and O'Donnell DE:

V̇/Q̇ Mismatch: A novel target for COPD treatment. Chest.

162:1030–1047. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Leiby KL, Raredon MSB and Niklason LE:

Bioengineering the Blood-gas Barrier. Compr Physiol. 10:415–452.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Weibel ER and Knight BW: A morphometric

study on the thickness of the pulmonary air-blood barrier. J Cell

Biol. 21:367–396. 1964. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Falcon-Rodriguez CI, Osornio-Vargas AR,

Sada-Ovalle I and Segura-Medina P: Aeroparticles, composition, and

lung diseases. Front Immunol. 7:32016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gao L, Zeng N, Yuan Z, Wang T, Chen L,

Yang D, Xu D, Wan C, Wen F and Shen Y: Knockout of Formyl peptide

Receptor-1 attenuates cigarette smoke-induced airway inflammation

in mice. Front Pharmacol. 12:6322252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lin H, Wang C, Yu H, Liu Y, Tan L, He S,

Li Z, Wang C, Wang F, Li P and Liu J: Protective effect of total

Saponins from American ginseng against cigarette smoke-induced COPD

in mice based on integrated metabolomics and network pharmacology.

Biomed Pharmacother. 149:1128232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vij N, Chandramani-Shivalingappa P, Van

Westphal C, Hole R and Bodas M: Cigarette smoke-induced autophagy

impairment accelerates lung aging, COPD-emphysema exacerbations and

pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 314:C73–C87. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zeng H, Kong X, Zhang H, Chen Y, Cai S,

Luo H and Chen P: Inhibiting DNA methylation alleviates cigarette

smoke extract-induced dysregulation of Bcl-2 and endothelial

apoptosis. Tob Induc Dis. 18:512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Van Eeckhoutte HP, Donovan C, Kim RY,

Conlon TM, Ansari M, Khan H, Jayaraman R, Hansbro NG, Dondelinger

Y, Delanghe T, et al: RIPK1 kinase-dependent inflammation and cell

death contribute to the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur Respir J.

61:22015062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

D'Anna SE, Maniscalco M, Cappello F,

Carone M, Motta A, Balbi B, Ricciardolo FLM, Caramori G and Stefano

AD: Bacterial and viral infections and related inflammatory

responses in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Med.

53:135–150. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Suresh A, Rao TC, Solanki S, Suresh MV,

Menon B and Raghavendran K: The holy basil administration

diminishes the NF-kB expression and protects alveolar epithelial

cells from pneumonia infection through interferon gamma. Phytother

Res. 36:1822–1835. 2022. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang B, Li H, Zhang J, Hang Y and Xu Y:

Activating transcription factor 3 protects alveolar epithelial type

II cells from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection-induced

inflammation. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 135:1022272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hardy KS, Tuckey AN, Renema P, Patel M,

Al-Mehdi AB, Spadafora D, Schlumpf CA, Barrington RA, Alexeyev MF,

Stevens T, et al: ExoU induces lung endothelial cell damage and

activates pro-inflammatory Caspase-1 during pseudomonas aeruginosa

infection. Toxins (Basel). 14:1522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lv R, Zhao Y, Wang X, He Y, Dong N, Min X,

Liu X, Yu Q, Yuan K, Yue H, et al: GLP-1 analogue liraglutide

attenuates CIH-induced cognitive deficits by inhibiting oxidative

stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis via the Nrf2/HO-1 and

MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 142:1132222024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cai SY, Liu A, Xie WX, Zhang XQ, Su B, Mao

Y, Weng DG and Chen ZY: Esketamine mitigates mechanical

ventilation-induced lung injury in chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease rats via inhibition of the MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway and

reduction of oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 139:1127252024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang XF, Xiang SY, Lu J, Li Y, Zhao SJ,

Jiang CW, Liu XG, Liu ZB and Zhang J: Electroacupuncture inhibits

IL-17/IL-17R and post-receptor MAPK signaling pathways in a rat

model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acupunct Med.

39:663–672. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Marumo S, Hoshino Y, Kiyokawa H, Tanabe N,

Sato A, Ogawa E, Muro S, Hirai T and Mishima M: p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase determines the susceptibility to

cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. BMC Pulm Med. 14:792014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jiang JJ, Chen SM, Li HY, Xie QM and Yang

YM: TLR3 inhibitor and tyrosine kinase inhibitor attenuate

cigarette smoke/poly I:C-induced airway inflammation and remodeling

by the EGFR/TLR3/MAPK signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol.

890:1736542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li Y, Li SY, Li JS, Deng L, Tian YG, Jiang

SL, Wang Y and Wang YY: A rat model for stable chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease induced by cigarette smoke inhalation and

repetitive bacterial infection. Biol Pharm Bull. 35:1752–1760.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu L, Qin Y, Cai Z, Tian Y, Liu X, Li J

and Zhao P: Effective-components combination improves airway

remodeling in COPD rats by suppressing M2 macrophage polarization

via the inhibition of mTORC2 activity. Phytomedicine.

92:1537592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jin F, Zhang L, Chen K, Miao Y, Liu Y,

Tian Y and Li J: Effective-component compatibility of Bufei Yishen

formula III combined with Electroacupuncture suppresses

inflammatory response in rats with chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease via regulating SIRT1/NF-κB signaling. Biomed Res Int.

2022:33607712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li MY, Qin YQ, Tian YG, Li KC, Oliver BG,

Liu XF, Zhao P and Li JS: Effective-component compatibility of

Bufei Yishen formula III ameliorated COPD by improving airway

epithelial cell senescence by promoting mitophagy via the

NRF2/PINK1 pathway. BMC Pulm Med. 22:4342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jia R, Wei M, Zhang X, Du R, Sun W, Wang L

and Song L: Pyroptosis participates in PM2.5-induced

air-blood barrier dysfunction. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int.

29:60987–60997. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yao XH, Luo T, Shi Y, He ZC, Tang R, Zhang

PP, Cai J, Zhou XD, Jiang DP, Fei XC, et al: A cohort autopsy study

defines COVID-19 systemic pathogenesis. Cell Res. 31:836–846. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Qiao Q, Liu X, Yang T, Cui K, Kong L, Yang

C and Zhang Z: Nanomedicine for acute respiratory distress

syndrome: The latest application, targeting strategy, and rational

design. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:3060–3091. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi

YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, Herridge M, Randolph AG and Calfee CS:

Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 5:182019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bhattacharya J and Matthay MA: Regulation

and repair of the alveolar-capillary barrier in acute lung injury.

Annu Rev Physiol. 75:593–615. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Thompson BT, Chambers RC and Liu KD: Acute

respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 377:562–572. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang T, Liu C, Pan LH, Liu Z, Li CL, Lin

JY, He Y, Xiao JY, Wu S, Qin Y, et al: Inhibition of p38 MAPK

mitigates lung ischemia reperfusion injury by reducing Blood-air

barrier Hyperpermeability. Front Pharmacol. 11:5692512020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Viola H, Washington K, Selva C, Grunwell

J, Tirouvanziam R and Takayama S: A High-throughput distal lung

air-blood barrier model enabled by density-driven underside

epithelium seeding. Adv Healthc Mater. 10:e21008792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mühlfeld C, Neves J, Brandenberger C,

Hegermann J, Wrede C, Altamura S and Muckenthaler MU: Air-blood

barrier thickening and alterations of alveolar epithelial type 2

cells in mouse lungs with disrupted hepcidin/ferroportin regulatory

system. Histochem Cell Biol. 151:217–228. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li W, Long L, Yang X, Tong Z, Southwood M,

King R, Caruso P, Upton PD, Yang P, Bocobo GA, et al: Circulating

BMP9 protects the pulmonary endothelium during inflammation-induced

lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 203:1419–1430.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang Y, Xue L, Wu Y, Zhang J, Dai Y, Li F,

Kou J and Zhang Y: Ruscogenin attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung

injury and pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction via

TLR4/Src/p120-catenin/VE-cadherin signalling pathway. J Pharm

Pharmacol. 73:893–900. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Guibourdenche J, Bonnet-Serrano F, Younes

Chaouch L, Sapin V, Tsatsaris V, Combarel D, Laguillier C and

Grange G: Amniotic Aaquaporins (AQP) in normal and pathological

pregnancies: Interest in Polyhydramnios. Reprod Sci. 28:2929–2938.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Weber J, Rajan S, Schremmer C, Chao YK,

Krasteva-Christ G, Kannler M, Yildirim AÖ, Brosien M, Schredelseker

J, Weissmann N, et al: TRPV4 channels are essential for alveolar

epithelial barrier function as protection from lung edema. JCI

Insight. 5:e1344642020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Arroyo R and Kingma PS: Surfactant protein

D and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: A new way to approach an old

problem. Respir Res. 22:1412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sorensen GL: Surfactant protein D in

respiratory and non-respiratory diseases. Front Med (Lausanne).

5:182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cheung KCP, Fanti S, Mauro C, Wang G, Nair

AS, Fu H, Angeletti S, Spoto S, Fogolari M, Romano F, et al:

Preservation of microvascular barrier function requires CD31

receptor-induced metabolic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 11:35952020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Akwii RG, Sajib MS, Zahra FT and Mikelis

CM: Role of angiopoietin-2 in vascular physiology and

pathophysiology. Cells. 8:4712019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Nicolini G, Forini F, Kusmic C, Iervasi G

and Balzan S: Angiopoietin 2 signal complexity in cardiovascular

disease and cancer. Life Sci. 239:1170802019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dai W, Nadadur RD, Brennan JA, Smith HL,

Shen KM, Gadek M, Laforest B, Wang M, Gemel J, Li Y, et al: ZO-1

regulates intercalated disc composition and atrioventricular node

conduction. Circ Res. 127:e28–e43. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Haas AJ, Zihni C, Krug SM, Maraspini R,

Otani T, Furuse M, Honigmann A, Balda MS and Matter K: ZO-1 guides

tight junction assembly and epithelial morphogenesis via

cytoskeletal tension-dependent and -independent functions. Cells.

11:37752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kakogiannos N, Ferrari L, Giampietro C,

Scalise AA, Maderna C, Ravà M, Taddei A, Lampugnani MG, Pisati F,

Malinverno M, et al: JAM-A Acts via C/EBP-α to promote claudin-5

expression and enhance endothelial barrier function. Circ Res.

127:1056–1073. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hashimoto Y, Campbell M, Tachibana K,

Okada Y and Kondoh M: Claudin-5: A pharmacological target to modify

the permeability of the blood-brain barrier. Biol Pharm Bull.

44:1380–1390. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Komiya K, Akaba T, Kozaki Y, Kadota JI and

Rubin BK: A systematic review of diagnostic methods to

differentiate acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome

from cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care. 21:2282017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Du L, Zhang J, Zhang X, Li C, Wang Q, Meng

G, Kan X, Zhang J and Jia Y: Oxypeucedanin relieves LPS-induced

acute lung injury by inhibiting the inflammation and maintaining

the integrity of the lung air-blood barrier. Aging (Albany NY).

14:6626–6641. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Peng LY, Yuan M, Shi HT, Li JH, Song K,

Huang JN, Yi PF, Fu BD and Shen HQ: Protective effect of

piceatannol against acute lung injury through protecting the

integrity of air-blood barrier and modulating the TLR4/NF-κB

signaling pathway activation. Front Pharmacol. 10:16132020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Peng LY, Shi HT, Yuan M, Li JH, Song K,

Huang JN, Yi PF, Shen HQ and Fu BD: Madecassoside protects against

LPS-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB activation

and blood-air barrier permeability. Front Pharmacol. 11:8072020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Sapoznikov A, Gal Y, Falach R, Sagi I,

Ehrlich S, Lerer E, Makovitzki A, Aloshin A, Kronman C and Sabo T:

Early disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier in a

ricin-induced ARDS mouse model: Neutrophil-dependent and

-independent impairment of junction proteins. Am J Physiol Lung

Cell Mol Physiol. 316:L255–L268. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Uysal P and Uzun H: Relationship between

circulating Serpina3g, Matrix Metalloproteinase-9, and tissue

inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 and −2 with chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease severity. Biomolecules. 9:622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Xu K, Ma J, Lu R, Shao X, Zhao Y, Cui L,

Qiu Z, Tian Y and Li J: Effective-compound combination of Bufei

Yishen formula III combined with ER suppress airway mucus

hypersecretion in COPD rats: Via EGFR/MAPK signaling. Biosci Rep.

43:BSR202226692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Rojas DA, Ponce CA, Bustos A, Cortés V,

Olivares D and Vargas SL: Pneumocystis exacerbates inflammation and

mucus hypersecretion in a murine, Elastase-induced-COPD model. J

Fungi (Basel). 9:4522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|