Introduction

The liver is the only human organ capable of

complete regeneration after partial resection (1). Even after resection of ≤70% of

hepatic mass, the remaining tissue can spontaneously restore liver

volume and function (2). This

notable regenerative capacity is important for favorable outcomes

in patients with severe liver injury, those undergoing living donor

liver transplantation, or patients undergoing surgical resection of

liver tumors and metastases (3).

Liver regeneration after hepatectomy can be broadly divided into

three phases: Initiation, growth and termination (4). Hepatocyte proliferation typically

peaks within the first 48 h post-surgery, after which the process

shifts towards functional restoration during the termination phase

(5). Failure to terminate

hepatocyte proliferation may impair subsequent differentiation,

hinder functional recovery of the liver, and may potentially lead

to poor outcomes or mortality (6).

Therefore, timely and effective termination of liver regeneration

is important for hepatocyte differentiation and restoration of

hepatic function.

At present, the initiation and growth phases of

liver regeneration have been extensively studied, but the molecular

mechanisms underlying the termination phase remain to be fully

elucidated (7,8). It has been reported that PP2Acα

regulates the termination of liver regeneration via the

AKT/GSK3β/cyclin D1 pathway (8).

Another study showed that hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α)

promotes hepatocyte cell cycle exit and the restoration of liver

function during the termination phase (6). In addition, hepatocyte

O-GlcNAcylation mediated by O-GlcNAc transferase represents an

important regulatory signal for termination of liver regeneration

(9).

Collagen, a major component of the extracellular

matrix (ECM), is important for functional remodeling during liver

regeneration (10). Furthermore,

it has been shown that endostatin, also known as collagen XVIII α1,

may regulate liver regeneration (11). A recent study has identified

characteristic clusters of collagen gene-expressing hepatic cells

following partial hepatectomy (PHx) (12). After PHx in rats, levels of

collagen I (col1) and collagen III (col3) have been reported to be

increased on postoperative days 3, 5 and 7, coinciding with the

timing of regeneration termination (13–15).

Previous studies have predominantly focused on total hepatic

collagen levels, with limited investigation into whether modulation

of collagen content affects liver regeneration (13–15).

However, collagen is highly expressed in areas surrounding

arterioles, venules and bile ducts, meaning that total hepatic

protein measurements may not accurately reflect the quantity of

collagen present in the hepatocyte-associated ECM (16). Therefore, the present study aimed

to explore how collagen in proximity to hepatocytes regulates the

termination of liver regeneration.

Materials and methods

Mouse PHx model

C57BL/6J mice (Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co.,

Ltd.; 69 female mice; age, 8 weeks; weight, 18–22 g) were housed in

the Animal Center of the Second Hospital Affiliated to Chongqing

Medical University (Chongqing, China). All animals were maintained

in temperature- and humidity-controlled facilities at 20–26°C and

60% humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with food and water

supplied ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by

the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing

Medical University (approval no. IACUC-SAHCQMU-2023-0027).

A 2/3 PHx model was established as previously

described (17). Briefly, under

isoflurane anesthesia (3% in the induction phase; 1.5–2% in the

maintenance phase), the left lateral and median lobes of the liver,

along with the gallbladder, were surgically removed. In the sham

group, mice underwent anesthesia and laparotomy for the same

average duration as the experimental groups but without hepatic

resection. Mice were subsequently sacrificed for tissue collection

at designated time points ranging from 0 h to 7 days

post-operation. Mice were euthanized by an overdose of 5%

isoflurane anesthesia, until complete cessation of the heartbeat

and respiration was observed. Subsequently, mouse liver tissues and

blood samples (from mouse fundus; ≥200 µl) were collected. Mouse

body weight was measured prior to euthanasia, and liver weight was

recorded after euthanasia. The serum liver function markers alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase, as well as

the renal function marker blood urea nitrogen, were measured by

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd. using an automated

biochemical analyzer. ALT levels were evaluated in two different

experiments: One including the PHx, PHx + Coln0.2 and PHx + Coln0.2

+ MSAB groups, and the other including the Coln0.2 and Control

groups. For groups subjected to PHx alone, three mice were included

per group, whereas for experimental groups receiving PHx combined

with pharmacological interventions, including the vehicle control

group, six mice were included per group.

Administration of EdU, collagenase and

methyl-sulfonyl AB (MSAB)

To assess cell proliferation, EdU (50 mg/kg; cat.

no. ST067; Beyotime Biotechnology) fully dissolved in PBS was

administered to all mice via intraperitoneal injection 2 h prior to

the designated sampling time. For the low-dose collagenase group

(Coln0.1 group, 5 mg/kg/day), collagenase III, also known as matrix

metalloproteinase-13 (cat. no. BS238; Biosharp Life Sciences), was

injected intraperitoneally on postoperative days 4, 5 and 6

following PHx. The high-dose group (Coln0.2 group, 10 mg/kg/day)

received collagenase III injections at the same time points as the

low-dose group. For the high-dose collagenase + MSAB group (Coln0.2

+ MSAB group), 5 mg/kg/day MSAB (cat. no. HY-120697;

MedChemExpress) was dissolved in an ultrasonic ice bath and

administered intraperitoneally 2 h prior to each collagenase

injection. To evaluate the biosafety of collagenase III,

intraperitoneal injections of 10 mg/kg/day collagenase III for 3

days or an appropriate volume of vehicle were administered to

C57BL/6J mice (n=3, these mice did not undergo PHx), followed by

tissue collection on day 4. These mice only received the

administration of collagenase III; specifically, they did not

receive EdU injection, MSAB injection, PHx or sham operation. The

drug was administered in 0.2 ml PBS per injection, while the

control group received an equivalent volume of PBS.

Histology and immunofluorescence (IF)

staining

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature overnight, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 µm.

Sections were deparaffinized in xylene for 30 min, followed by 100%

ethanol for 10 min and sequential rehydration in 95, 85 and 75%

ethanol for 5 min each, followed by ddH2O for 1 min.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed according to

the manufacturer's instructions (Hematoxylin-Eosin Stain Kit; cat.

no. G1120; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Sections were stained with hematoxylin for 3 min, differentiated in

1% hydrochloric acid for 5 sec, blued in 10% ammonium solution for

30 sec and stained with eosin for 1.5 min; all at room temperature.

Images were captured using a light microscope. IF staining was

performed to evaluate the expression of col1, desmin, α-smooth

muscle actin (α-SMA), col3 and Ki-67. Antibody information can be

found in Table I. For col1,

desmin, α-SMA, col3 and Ki-67 IF staining, sections were subjected

to citrate buffer (cat. no. C1032; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) at 90°C for 15 min. The sections were blocked

with 10% normal goat serum (cat. no. AR0009; Boster Biological

Technology) at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, sections

were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Sections

were subsequently incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary

antibodies at room temperature for 2 h, followed by DAPI staining

at room temperature for 20 min before mounting. For sections

requiring EdU double-labeling, EdU staining was performed using the

BeyoClick™ EdU-488 Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (cat.

no. C0071S; Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's

protocol prior to DAPI counterstaining. The fluorescence signals

were detected and visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Leica

Microsystems, Inc.). IF staining was independently scored and

reviewed by two blinded evaluators. For semi-quantification of col3

in the parenchymal area, regions lacking vessels and bile ducts

were preselected and the average fluorescence intensity was

measured. For EdU and Ki-67, the nuclear positivity rate was

calculated. Positive nuclei were identified and semi-quantified

using ImageJ version 2.1.0 (National Institutes of Health) by

applying the threshold, binary and analyze particles functions.

Each group contained three biological replicates (n=3).

| Table I.Information on antibodies. |

Table I.

Information on antibodies.

| Target | Manufacturer | Cat. no. | Application | Dilution ratio |

|---|

| Collagen I | Abcam | ab270993 | IF | 1:500 |

| Desmin | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 16520-1-AP | IF | 1:500 |

| α-SMA | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 14395-1-AP | IF | 1:1,000 |

| Collagen III | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 22734-1-AP | IF | 1:300 |

| Ki-67 | Proteintech Group,

Inc. | 28074-1-AP | IF | 1:500 |

| Cy3 conjugated

Goat | Wuhan

Servicebio | GB21303 | IF | 1:200 |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG

(H+L) | Technology Co.,

Ltd. |

|

|

|

| β-catenin | Abcam | ab305261 | WB | 1:1,000 |

| HNF4α | Santa Cruz | sc-101059 | WB | 1:100 |

|

| Biotechnology,

Inc. |

|

|

|

| Cyclin D1 | CST Biological | 2978S | WB | 1:1,000 |

|

| Reagents Co.,

Ltd. |

|

|

|

| GAPDH | HUABIO | HA721136 | WB | 1:5,000 |

| β-actin | HUABIO | HA722023 | WB | 1:20,000 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit

IgG-HRP | Absin Bioscience,

Inc. | abs20040 | WB | 1:5,000 |

| Goat anti-Mouse

IgG-HRP | Absin Bioscience,

Inc. | abs20039 | WB | 1:5,000 |

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from liver tissue using

RIPA buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Biotechnology) supplemented

with PMSF. The protein concentration was measured using the BCA

Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. P0010; Beyotime Biotechnology), and 20

µg of protein was loaded per lane. Proteins were separated by

SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and then transferred onto PVDF membranes. The

membranes were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in Protein

Free Rapid Blocking Buffer (cat. no. PS108P; Epizyme; Ipsen

Pharma). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at

4°C with primary antibodies against β-catenin, HNF4α, cyclin D1,

GAPDH and β-actin. GAPDH and β-actin served as loading controls.

The membranes were incubated with the secondary antibodies at room

temperature for 2 h. Antibody information can be found in Table I. Target protein expression was

detected using an ECL kit (cat. no. AR1191; Boster Biological

Technology). The intensity of each band was measured using ImageJ

version 2.1.0 (National Institutes of Health). Each group contained

three biological replicates (n=3).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was performed as previously described

(18). Total mRNA was isolated

from liver tissues using RNAiso Plus (cat. no. 9108; Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, 500 ng mRNA was

reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (cat. no.

HY-K0511A; MedChemExpress). The reverse transcription temperature

program was set according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR

was performed on the resulting cDNA using SYBR Green qPCR Master

Mix (cat. no. HY-K0501; MedChemExpress) on a CFX connect real-time

PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). qPCR was carried

out with an initial activation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min, and a final melting

curve at 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min and 95°C for 15 sec. GAPDH

served as the internal reference gene, and the relative expression

of the target gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (19). The primer sequences

used for RT-qPCR are provided in Table II. Each group contained three

biological replicates (n=3).

| Table II.Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR primers. |

Table II.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR primers.

| Primer | Sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| Col3a1 |

|

| Forward |

CTGTAACATGGAAACTGGGGAAA |

| Reverse |

CCATAGCTGAACTGAAAACCACC |

| Gapdh |

|

| Forward |

CAAGGAGTAAGAAACCCTGGAC |

| Reverse |

GGATGGAAATTGTGAGGGAGAT |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad

Prism version 9.0 (Dotmatics). Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation. An unpaired Student's t-test was used for

comparisons between two groups. One-way ANOVA was applied for

multiple group comparisons, and pairwise comparisons were performed

using Tukey's post hoc test. Two-tailed P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

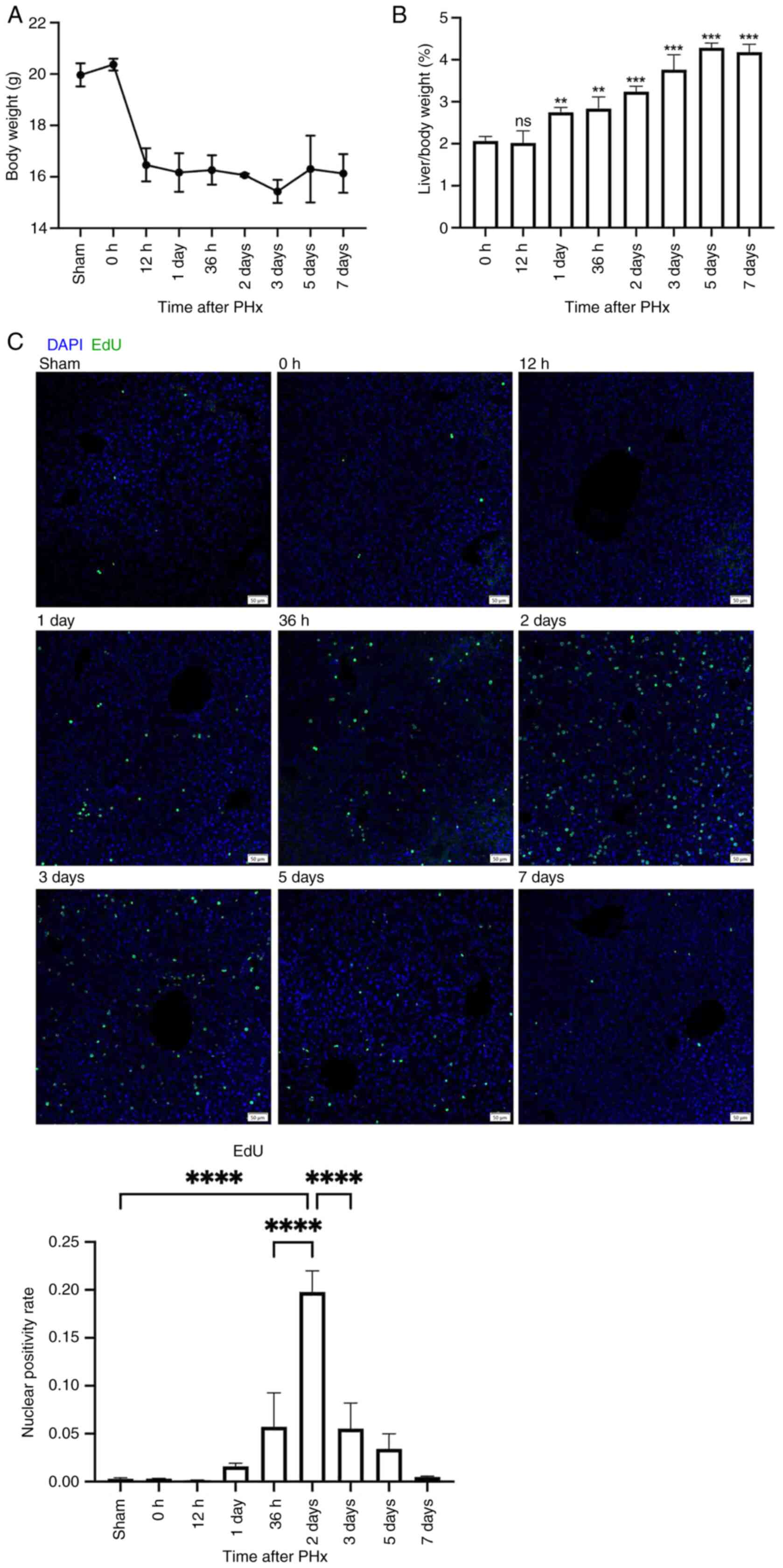

Spontaneous liver regeneration after

2/3 PHx in mice

The present study established a mouse model of 2/3

PHx and collected liver tissues at specific time points

post-surgery. EdU was intraperitoneally injected 2 h before tissue

harvest. The present study observed a partial reduction in body

weight after PHx (Fig. 1A), while

the liver-to-body weight ratio began to significantly recover from

day 1 post-PHx (Fig. 1B). The

nuclear positivity rate of EdU increased starting from day 1,

peaked significantly at day 2 and gradually decreased from days 2

to 7 (Fig. 1C). These findings

indicated that spontaneous liver regeneration occurred after 2/3

PHx in mice. The growth phase occurred between days 1 and 2, with

the highest hepatocyte proliferation rate observed on day 2,

followed by a termination phase of liver regeneration from days 2

to 7.

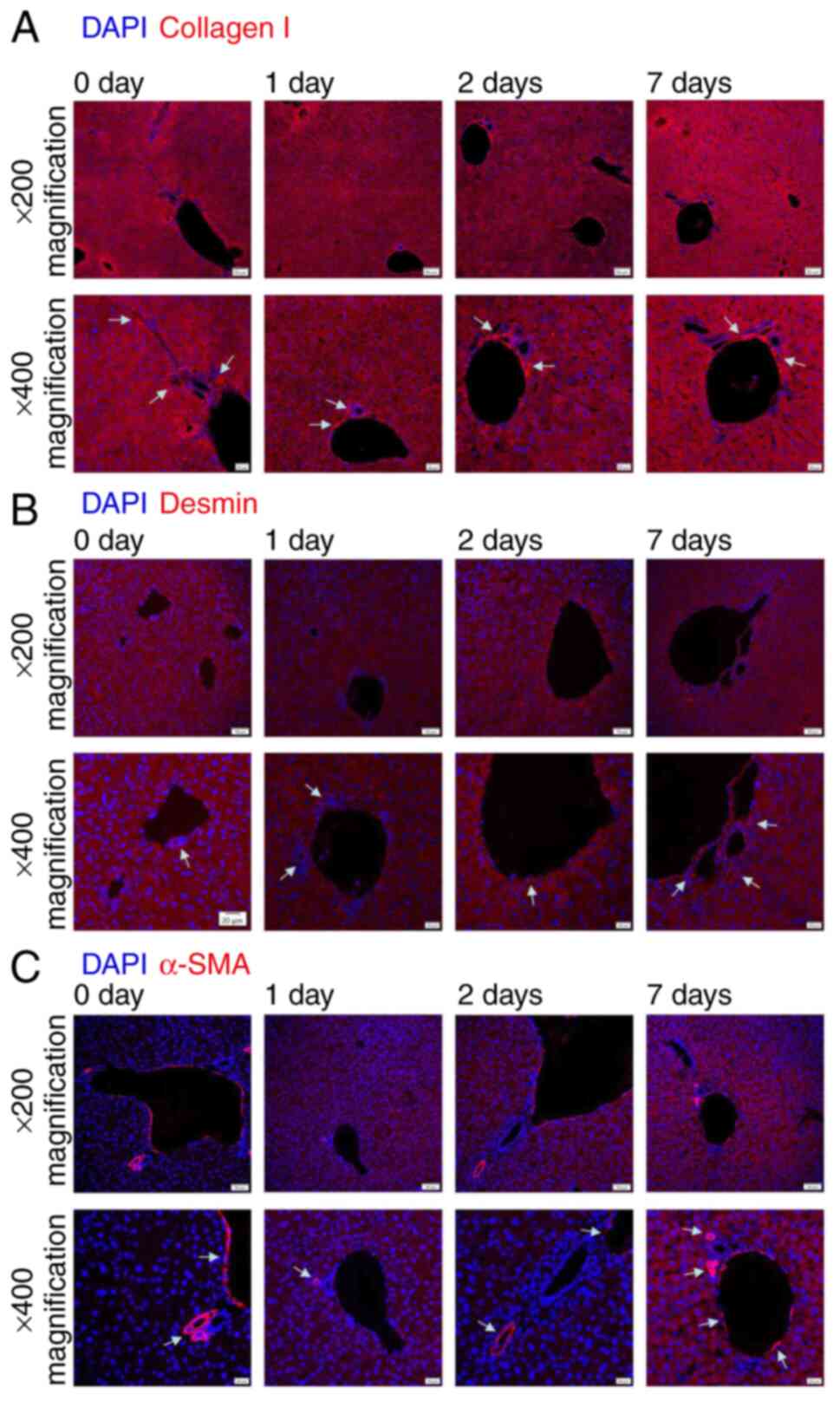

Expression of collagen after PHx

The present study hypothesized that specific

components within the hepatocyte-associated ECM may regulate liver

regeneration. These components were hypothesized to be distributed

in proximity to hepatocytes and exhibit dynamic changes across

different stages of regeneration. Therefore, the present study

evaluated the expression of major collagens or proteins related to

collagens during liver regeneration via IF staining, including

col1, col3, desmin and α-SMA. Col1, desmin and α-SMA were

predominantly expressed surrounding hepatic blood vessels and bile

ducts across all experimental time points, with comparatively low

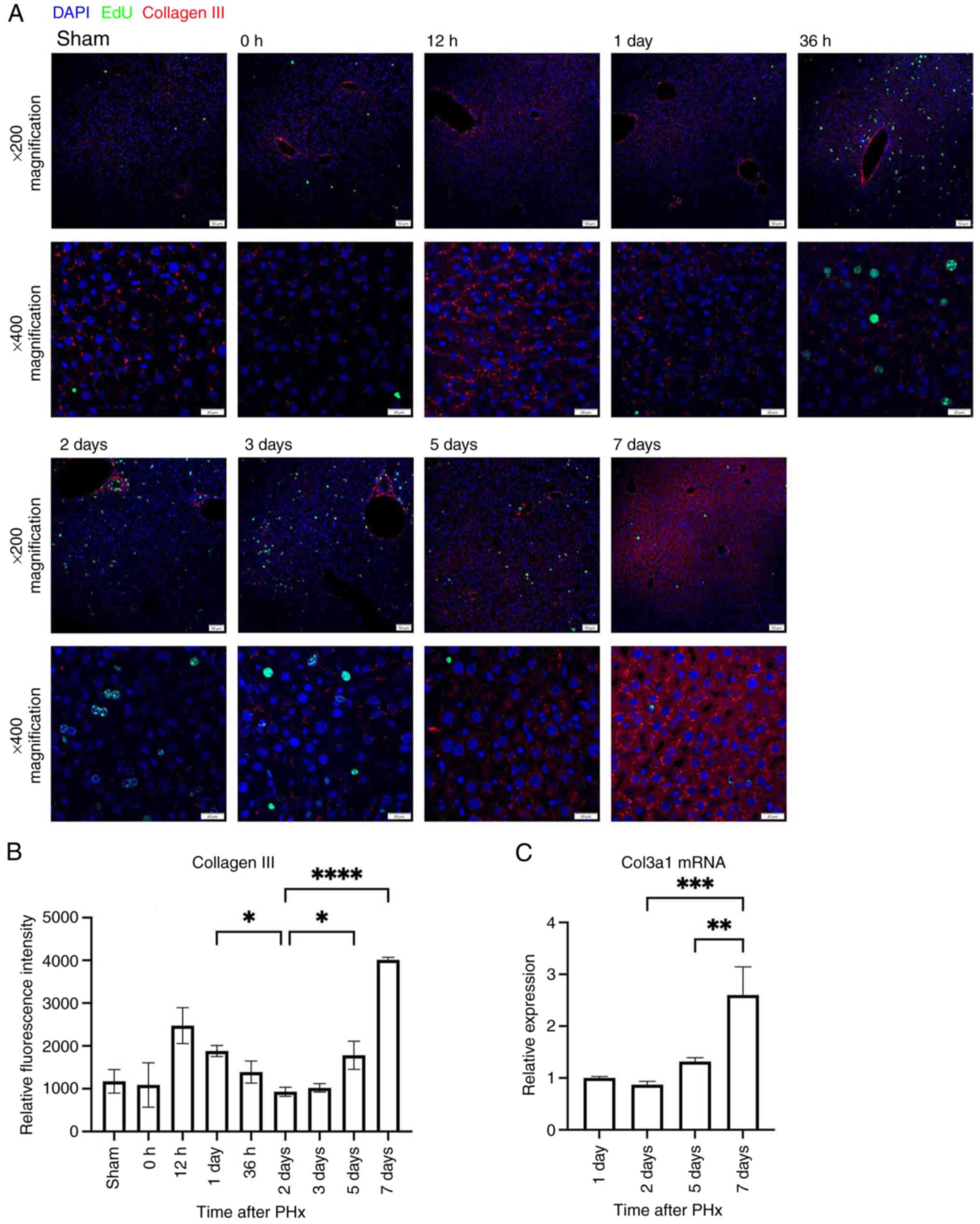

expression observed in parenchymal areas (Fig. 2). By contrast, col3 was abundantly

expressed not only in proximity to blood vessels and bile ducts but

also surrounding hepatocytes in parenchymal areas (Fig. 3A). Semi-quantitative analysis of

average fluorescence intensity in parenchymal areas showed that

col3 expression was significantly decreased during the

proliferative phase from days 1–2 and significantly increased again

during the termination phase across days 2–7 (Fig. 3B). RT-qPCR supported that Col3α1

mRNA expression increased significantly from days 2 to 7 (Fig. 3C). These findings suggested that

col3 levels in parenchymal areas may have been inversely associated

with hepatocyte proliferation and that col3 may have acted as a

negative regulator of regeneration.

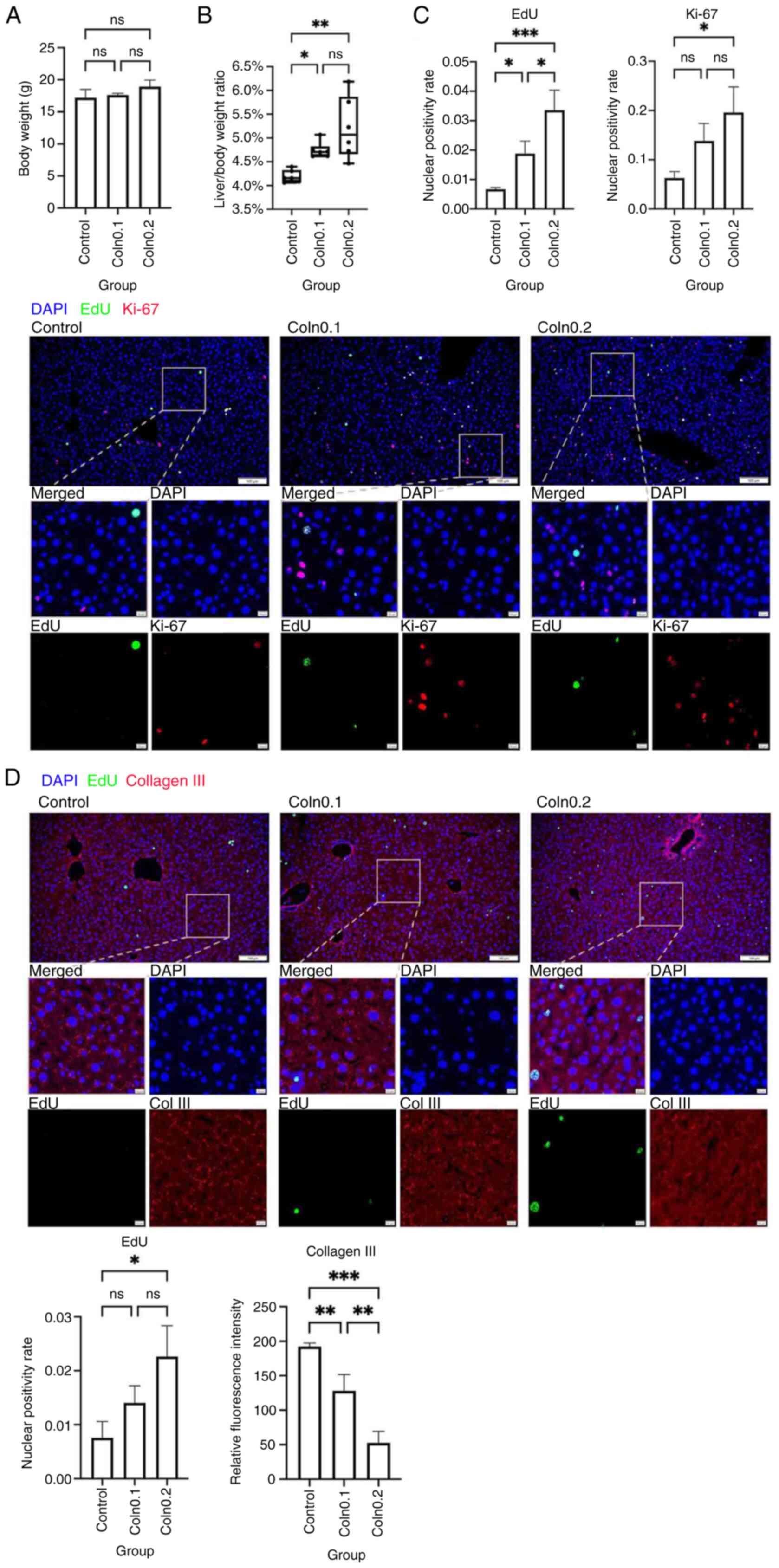

Degradation of col3 promotes

proliferation and delays regenerative termination

To assess whether col3 suppressed hepatocyte

proliferation, mice were administered either low or high doses of

collagenase III on days 4, 5 and 6 post-hepatectomy; samples of

liver tissue were subsequently collected on day 7. Compared with in

the control group, body weight was unchanged in collagenase-treated

mice, but the liver-to-body weight ratio was significantly higher

in both collagenase groups (Fig. 4A

and B). Dual IF staining for Ki-67 and EdU provided evidence of

a significantly higher proportion of proliferating cells in the

collagenase groups, with the highest proliferation rates observed

in the high-dose group (Fig. 4C).

Dual IF staining of col3 and EdU showed that, compared with that in

the control group, col3 expression in parenchymal areas was

significantly reduced in collagenase groups, while EdU nuclear

positivity increased significantly after high-dose collagenase

treatment (Fig. 4D). These results

indicated that collagenase III effectively degraded col3 in

parenchymal areas and promoted hepatocyte proliferation, delaying

the termination of regeneration in a dose-dependent manner.

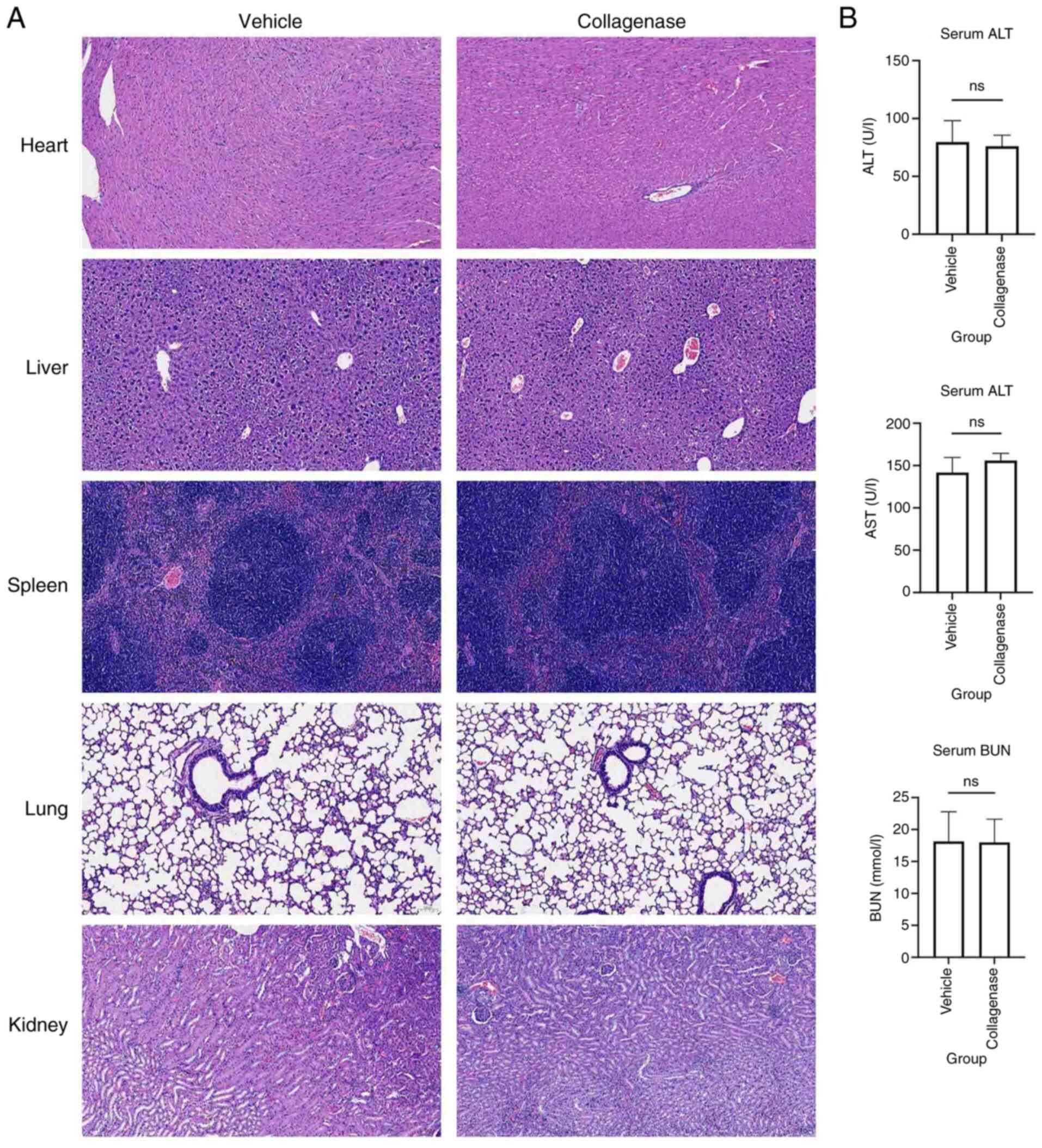

To evaluate the biosafety of collagenase III,

intraperitoneal injections of 10 mg/kg/day collagenase III for 3

days or an appropriate volume of vehicle were administered to

C57BL/6J mice, followed by tissue collection on day 4. H&E

staining showed no notable tissue damage or abnormalities in the

heart, liver, spleen, lungs or kidneys of collagenase III-treated

mice compared with vehicle-treated control mice (Fig. 5A). Additionally, levels of serum

markers of liver and renal function revealed no significant

differences between the two groups (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that

intraperitoneal injections of collagenase III at the dosage used in

the present study were well tolerated and exhibited sufficient

biosafety.

Col3 degradation triggers

β-catenin-mediated abnormal proliferation, which is rescued by

MSAB

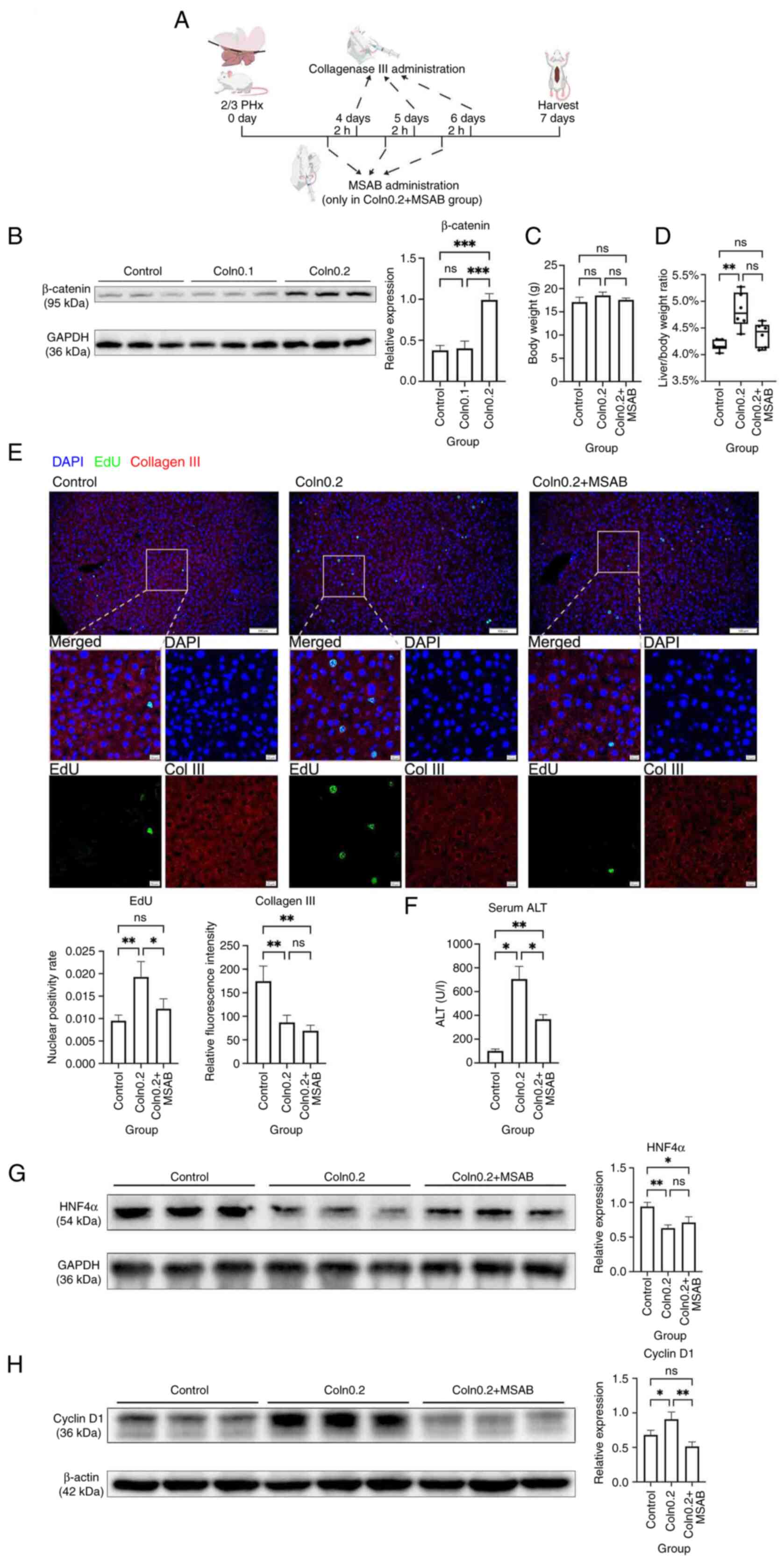

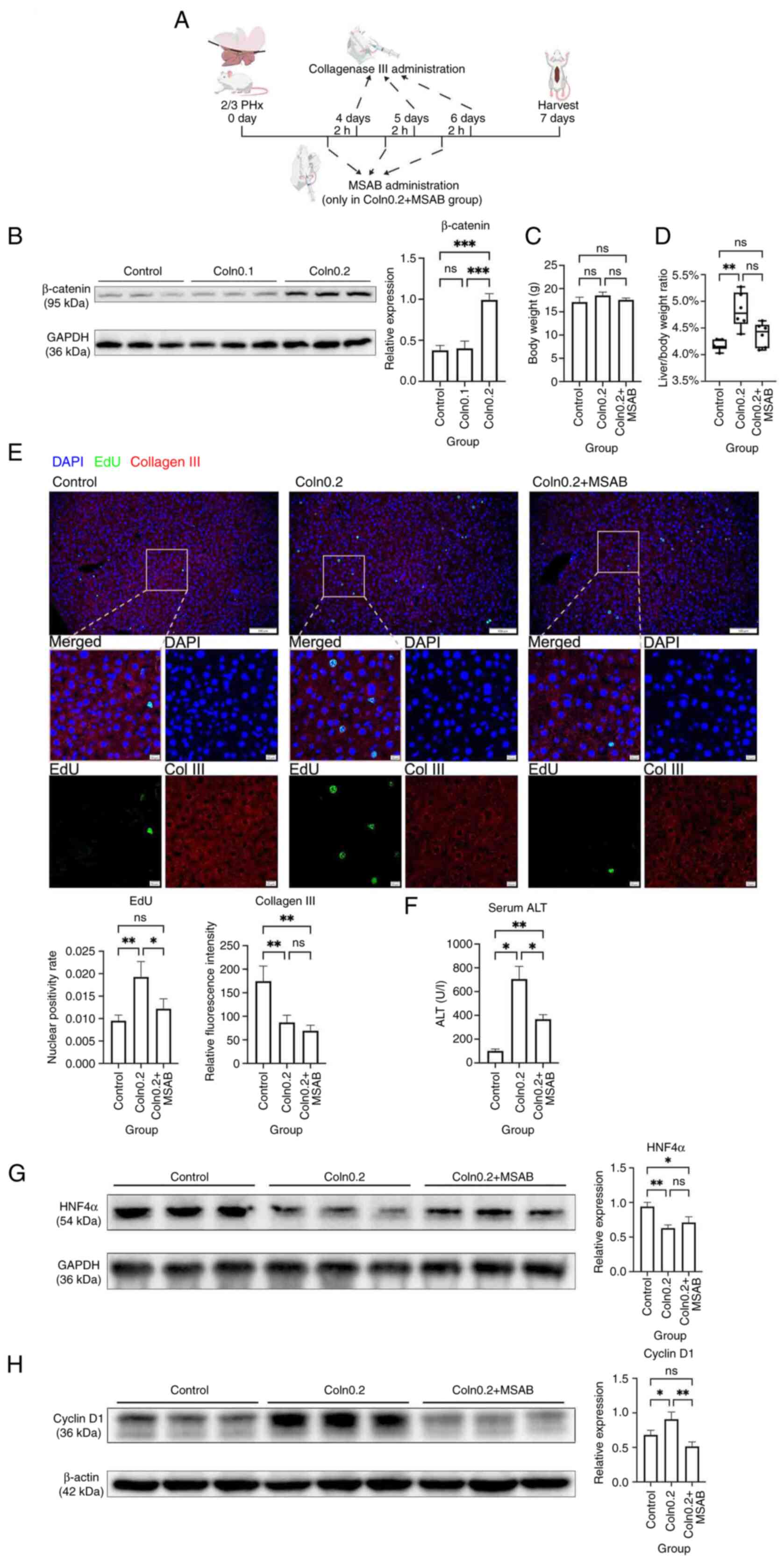

Given the well-established role of the β-catenin

pathway in liver regeneration (20), the present study subsequently

investigated whether the proliferative effect of col3 degradation

involved this pathway. Western blot analysis showed that

administration of high-dose collagenase significantly increased

β-catenin expression compared with both the control and low-dose

groups, indicating pathway activation (Fig. 6B).

| Figure 6.Inhibition of β-catenin partially

rescues impaired regeneration termination and liver dysfunction

induced by collagen III degradation. (A) Schematic diagram of the

animal experimental protocol; created with BioGDP.com (agreement

no. GDP2025X2AT2F) (35). (B) WB

analysis of β-catenin after collagen III degradation. (C) Body

weight and (D) liver-to-body weight ratio of mice following

collagen III degradation and β-catenin inhibition. (E) Dual

immunofluorescence staining of EdU and collagen III following

collagen III degradation and β-catenin inhibition. Scale bars, 100

and 10 µm. (F) Serum liver function marker levels following

collagen III degradation and β-catenin inhibition. (G) WB analysis

of HNF4α following collagen III degradation and β-catenin

inhibition. (H) WB analysis of cyclin D1 following collagen III

degradation and β-catenin inhibition. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. ns, not significant; WB, western blot; PHx, partial

hepatectomy; MSAB, methyl-sulfonyl AB; Coln0.1, low-dose

collagenase III; Coln0.2, high-dose collagenase III; Col III,

collagen III; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HNF4α, hepatocyte

nuclear factor 4α. |

To further assess causality, the β-catenin inhibitor

MSAB was administered to mice intraperitoneally 2 h before each

collagenase injection on days 4, 5 and 6 (Fig. 6A). MSAB did not significantly

affect body weight but partially reversed the collagenase-induced

increase in the liver-to-body weight ratio, returning it close to

control levels, although this difference was not statistically

significant (Fig. 6C and D). Dual

IF staining for col3 and EdU showed that administration of MSAB

alongside high-dose collagenase treatment did not alter col3

expression but significantly reduced EdU positivity (Fig. 6E), suggesting that β-catenin

inhibition partially reversed the proliferative effect induced by

col3 degradation.

To evaluate the effect of abnormal hepatocyte

proliferation on liver function, serum ALT levels were measured.

Mice treated with collagenase exhibited significantly elevated ALT

compared with control mice, which was indicative of liver injury,

while co-treatment with MSAB significantly reduced ALT levels

(Fig. 6F). Western blotting showed

that the hepatocyte differentiation marker HNF4α was significantly

decreased after collagenase treatment (Fig. 6G). Additionally, cyclin D1, a

downstream target of β-catenin, was significantly upregulated

following collagenase administration compared with in the control

group, and was subsequently significantly downregulated upon MSAB

co-treatment (Fig. 6H).

Taken together, these results demonstrated that col3

degradation during the termination phase activated the β-catenin

pathway, disrupted the termination of liver regeneration, promoted

abnormal hepatocyte proliferation and impaired liver function.

Inhibition of β-catenin by MSAB partially rescued these

effects.

Discussion

Liver regeneration is regulated by multiple

mechanisms and signaling pathways; however, the processes governing

its termination remain to be fully elucidated. The present study

investigated the role of col3 in the termination of liver

regeneration following 2/3 PHx. The findings of the present study

suggested that col3 may regulate the termination of liver

regeneration via the β-catenin pathway, while promoting functional

recovery of the liver.

ECM is a complex and well-organized

three-dimensional network that provides structural support to cells

and tissues (21). Beyond its

mechanical role, the ECM coordinates intercellular signaling, and

mediates communication between tissues and organs (22). Through the regulation of cell

proliferation, differentiation and adhesion, the ECM serves an

important role in guiding tissue morphogenesis, development and

homeostatic maintenance (23). ECM

remodeling under pathological conditions serves as a key driver of

disease progression (24,25). Collagen is a major structural

component of the ECM, accounting for >30% of total ECM protein,

with col1, col2 and col3 comprising 80–90% of all collagens in the

body (23). In the context of

liver disease, col1 and col3 are primarily known for forming the

structural scaffold of the liver and providing tensile strength to

the hepatic lobule (23). Their

excessive accumulation is a hallmark of liver fibrosis (23). Previous studies have examined the

temporal changes of hepatic col1 and col3 in a rat PHx model

(13–15). Consistent with the results of the

present study performed in mice, the expression of both col1 and

col3 gradually increased during the termination phase of liver

regeneration. However, the present study found that only col3 was

expressed surrounding hepatocytes in parenchymal areas, suggesting

that col3 may have represented the major collagen component acting

within the hepatocyte-associated ECM. Recent studies have reported

an elevated expression of col3 in poorly regenerating skin tissue,

and have indicated that this could suppress scar formation during

wound healing (26,27). The findings of these studies

suggest that col3 may serve as a negative regulator of

regeneration, possibly by limiting proliferation or tissue

remodeling. This raises the possibility that col3 may serve a

similar regulatory role in the termination of liver

regeneration.

The findings of the present study suggested that the

accumulation of col3 in close proximity to hepatocytes may create a

microenvironment which suppresses excessive hepatocyte

proliferation, while promoting hepatocyte differentiation,

maturation and functional recovery. In the present study, col3 was

associated with reduced expression of proliferative markers,

supporting the notion that col3 may function as a negative

regulator of proliferative cues. Furthermore, col3 appeared to

facilitate the transition from proliferation to functional

recovery. By upregulating HNF4α, col3 may promote hepatocyte

differentiation and maturation, which is important for restoring

hepatic function once regenerative growth subsides (6). Such dual actions, including the

restriction of excessive hepatocyte proliferation and the promotion

of functional reconstruction, highlight col3 as a key ECM component

that may ensure the sufficient termination of liver regeneration.

These mechanistic insights provide a foundation for future studies

aimed at manipulating ECM remodeling to improve postoperative liver

recovery.

β-catenin, a central component of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway, is activated during the early phase of liver

regeneration and promotes hepatocyte proliferation (20). In the present study, the

degradation of col3 during the termination phase of liver

regeneration was followed by the upregulation of β-catenin and

abnormal proliferation. Notably, col3 is generally considered a

downstream target of β-catenin during hepatic fibrosis, being

upregulated following β-catenin activation (28). The results of the present study

suggested that the degradation of col3 upregulated β-catenin

expression in return, indicating a potential bidirectional feedback

loop between col3 and β-catenin. However, the mechanisms underlying

this interaction require further investigation.

Following PHx, once liver mass and volume are

largely restored, proliferation is gradually terminated and

hepatocytes enter a redifferentiation process to recover normal

liver function (6). A previous

study has reported that HNF4α serves an important role during the

termination phase of liver regeneration by promoting hepatocyte

maturation and maintaining hepatic function (6). HNF4α is a key regulator of hepatocyte

differentiation and controls as much as 60% of all hepatic genes

(29,30). In the present study, degradation of

col3 during the termination phase led to the downregulation of

HNF4α, suggesting that hepatocytes failed to properly differentiate

and regain normal function. A previous study has shown that mice

with impaired termination of liver regeneration may develop small

nodules at 28 days after PHx, indicating that defects in

regeneration termination may further progress to tumorigenesis

(9). The results of the present

study also showed that the body weight of mice at 12 h after PHx

was lower than that of mice in the sham and PHx 0 h groups. This

may have been due to a number of factors. On the one hand,

postoperative pain may have led to reduced food and water intake.

On the other hand, abdominal surgery may have been accompanied by

fluid loss. Furthermore, transient liver injury could have caused

digestive dysfunction.

There are several limitations to the present study.

Primarily, the present study used collagenase III to degrade

collagen. Although collagenase III is known to preferentially

digest col3 located in proximity to cells, it can also cleave

various other ECM proteins (31).

Therefore, the present study cannot exclude the possibility that

other ECM proteins may have exerted similar or opposite effects on

hepatic regeneration to those observed. Furthermore, although IF

staining did not reveal positive col1 staining surrounding

hepatocytes in parenchymal areas, the present study cannot rule out

potential contributions of col1 or other collagens in the

hepatocyte-associated ECM to the observed results. Additionally,

considering that liver regeneration is regulated by multiple

signaling pathways (7), disruption

of one pathway may be compensated by the activation of others. The

present study only empirically evaluated the involvement of the

β-catenin pathway and did not explore the contribution of other

potential pathways. Nevertheless, inhibition of β-catenin partially

rescued the impaired termination of liver regeneration, providing

support for β-catenin serving at least a partial role in this

process. Finally, the present study focused exclusively on

hepatocytes, with limited investigation of other cell types. A

growing body of evidence has demonstrated that non-epithelial cells

have important roles in various liver diseases (32–34).

Although hepatocytes ultimately execute hepatic functions, they are

also regulated by other cell types. Further studies are warranted

to elucidate the complex interactions among different cell

populations in the liver.

In summary, the present study provided preliminary

evidence that col3 may regulate the termination of liver

regeneration by suppressing hepatocyte proliferation and promoting

functional recovery. Further studies are needed to elucidate the

underlying mechanisms in greater detail.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Nature Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82102337), the Natural Science

Foundation of Chongqing (grant no. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX0899) and the

Special Funding for Postdoctoral Research Project of Chongqing

(grant no. 2021XM3071).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AZ and JG were responsible for the conception and

design of the experiments. HP, ZC, QZ, YZ and PY contributed

towards the acquisition and analysis of data. HP, ZC and AZ

interpreted the data. HP, YZ and PY were responsible for drafting

the manuscript. JG and AZ reviewed and edited the manuscript. HP,

ZC, QZ, YZ, PY, JG and AZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical

University (approval no. IACUC-SAHCQMU-2023-0027).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

PHx

|

partial hepatectomy

|

|

col3

|

collagen III

|

|

col1

|

collagen I

|

|

ALT

|

alanine aminotransferase

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

References

|

1

|

Wu Y, Min J, Ge C, Shu J, Tian D, Yuan Y

and Zhou D: Interleukin 22 in liver injury, inflammation and

cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 16:2405–2413. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shao C, Jing Y, Zhao S, Yang X, Hu Y, Meng

Y, Huang Y, Ye F, Gao L, Liu W, et al: LPS/Bcl3/YAP1 signaling

promotes Sox9+HNF4α+ hepatocyte-mediated

liver regeneration after hepatectomy. Cell Death Dis. 13:2772022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Satilmis B, Akbulut S, Sahin TT, Dalda Y,

Tuncer A, Kucukakcali Z, Ogut Z and Yilmaz S: Assessment of liver

regeneration in patients who have undergone living donor

hepatectomy for living donor liver transplantation. Vaccines

(Basel). 11:2442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

de Haan LR, van Golen RF and Heger M:

Molecular pathways governing the termination of liver regeneration.

Pharmacol Rev. 76:500–558. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang L, Zhou Y, Huang Z, Li W, Lin J,

Huang W, Sang Y, Wang F, Sun X, Song J, et al: Electroacupuncture

promotes liver regeneration by activating DMV acetylcholinergic

neurons-vagus-macrophage axis in 70% partial hepatectomy of mice.

Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e24028562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Huck I, Gunewardena S, Espanol-Suner R,

Willenbring H and Apte U: Hepatocyte Nuclear factor 4 alpha

activation is essential for termination of liver regeneration in

mice. Hepatology. 70:666–681. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tsomaia K, Patarashvili L, Karumidze N,

Bebiashvili I, Azmaipharashvili E, Modebadze I, Dzidziguri D,

Sareli M, Gusev S and Kordzaia D: Liver structural transformation

after partial hepatectomy and repeated partial hepatectomy in rats:

A renewed view on liver regeneration. World J Gastroenterol.

26:3899–3916. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lai SS, Zhao DD, Cao P, Lu K, Luo OY, Chen

WB, Liu J, Jiang EZ, Yu ZH, Lee G, et al: PP2Acα positively

regulates the termination of liver regeneration in mice through the

AKT/GSK3β/cyclin D1 pathway. J Hepatol. 64:352–360. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Robarts DR, McGreal SR, Umbaugh DS, Parkes

WS, Kotulkar M, Abernathy S, Lee N, Jaeschke H, Gunewardena S,

Whelan SA, et al: Regulation of liver regeneration by hepatocyte

O-GlcNAcylation in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

13:1510–1529. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Akhtam R, Nuraliyevna SN, Kadham MJ,

Mirzakhamitovna KS, Tursunaliyevna RM, Shakhnoz K, Shakhzod T,

Otabek B, Baxtiyorovich MI, Shakhboskhanovna AF, et al: Biomarkers

in liver regeneration. Clin Chim Acta. 576:1204132025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yazici SE, Gedik ME, Leblebici CB,

Kosemehmetoglu K, Gunaydin G and Dogrul AB: Can endocan serve as a

molecular ‘hepatostat’ in liver regeneration? Mol Med. 29:292023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kimura Y, Koyama Y, Taura K, Kudoh A,

Echizen K, Nakamura D, Li X, Nam NH, Uemoto Y, Nishio T, et al:

Characterization and role of collagen gene expressing hepatic cells

following partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 77:443–455.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Klaas M, Kangur T, Viil J, Mäemets-Allas

K, Minajeva A, Vadi K, Antsov M, Lapidus N, Järvekülg M and Jaks V:

The alterations in the extracellular matrix composition guide the

repair of damaged liver tissue. Sci Rep. 6:273982016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rudolph KL, Trautwein C, Kubicka S,

Rakemann T, Bahr MJ, Sedlaczek N, Schuppan D and Manns MP:

Differential regulation of extracellular matrix synthesis during

liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in rats. Hepatology.

30:1159–1166. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yamamoto H, Murawaki Y and Kawasaki H:

Hepatic collagen synthesis and degradation during liver

regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Hepatology. 21:155–161.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rho H, Terry AR, Chronis C and Hay N:

Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is

required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis.

Cell Metab. 35:1406–1423.e8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wei S, Guan G, Luan X, Yu C, Miao L, Yuan

X, Chen P and Di G: NLRP3 inflammasome constrains liver

regeneration through impairing MerTK-mediated macrophage

efferocytosis. Sci Adv. 11:eadq57862025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Dong J and Liu C: HNRNPC

as a pan-cancer biomarker and therapeutic target involved in tumor

progression and immune regulation. Oncol Res. 33:83–102.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−∆∆C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hu S, Cao C, Poddar M, Delgado E, Singh S,

Singh-Varma A, Stolz DB, Bell A and Monga SP: Hepatocyte β-catenin

loss is compensated by insulin-mTORC1 activation to promote liver

regeneration. Hepatology. 77:1593–1611. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Saraswathibhatla A, Indana D and Chaudhuri

O: Cell-extracellular matrix mechanotransduction in 3D. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 24:495–516. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sack KD, Teran M and Nugent MA:

Extracellular matrix stiffness controls VEGF signaling and

processing in endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 231:2026–2039.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Karamanos NK, Theocharis AD, Piperigkou Z,

Manou D, Passi A, Skandalis SS, Vynios DH, Orian-Rousseau V,

Ricard-Blum S, Schmelzer CEH, et al: A guide to the composition and

functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 288:6850–6912. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mavrogonatou E, Pratsinis H, Papadopoulou

A, Karamanos NK and Kletsas D: Extracellular matrix alterations in

senescent cells and their significance in tissue homeostasis.

Matrix Biol. 75–76. 27–42. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Karamanos NK: Extracellular matrix: Key

structural and functional meshwork in health and disease. FEBS J.

286:2826–2829. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Stewart DC, Brisson BK, Yen WK, Liu Y,

Wang C, Ruthel G, Gullberg D, Mauck RL, Maden M, Han L and Volk SW:

Type III collagen regulates matrix architecture and mechanosensing

during wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 145:919–938.e14. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tan PC, Zhou SB, Ou MY, He JZ, Zhang PQ,

Zhang XJ, Xie Y, Gao YM, Zhang TY and Li QF: Mechanical stretching

can modify the papillary dermis pattern and papillary fibroblast

characteristics during skin regeneration. J Invest Dermatol.

142:2384–2394.e8. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yamaji K, Iwabuchi S, Tokunaga Y,

Hashimoto S, Yamane D, Toyama S, Kono R, Kitab B, Tsukiyama-Kohara

K, Osawa Y, et al: Molecular insights of a CBP/β-catenin-signaling

inhibitor on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-induced liver fibrosis

and disorder. Biomed Pharmacother. 166:1153792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kotulkar M, Robarts DR and Apte U: HNF4α

in hepatocyte health and disease. Semin Liver Dis. 43:234–244.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ko HL, Zhuo Z and Ren EC: HNF4α

combinatorial isoform heterodimers activate distinct gene targets

that differ from their corresponding homodimers. Cell Rep.

26:2549–2557.e3. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li S, Pritchard DM and Yu LG: Regulation

and function of matrix metalloproteinase-13 in cancer progression

and metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 14:32632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang Z, Mou T, Luo Y, Pu X, Pu J, Wan L,

Gong J, Yang H, Liu Y, Li Z, et al: Inhibition of miR-450b-5p

ameliorates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury via targeting

CRYAB. Cell Death Dis. 11:4552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li TT, Luo YH, Yang H, Chai H, Lei ZL,

Peng DD, Wu ZJ and Huang ZT: FBXW5 aggravates hepatic

ischemia/reperfusion injury via promoting phosphorylation of ASK1

in a TRAF6-dependent manner. Int Immunopharmacol. 99:1079282021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Huang Z, Zheng D, Pu J, Dai J, Zhang Y,

Zhang W and Wu Z: MicroRNA-125b protects liver from

ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting TRAF6 and NF-κB pathway.

Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 83:829–835. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jiang S, Li H, Zhang L, Mu W, Zhang Y,

Chen T, Wu J, Tang H, Zheng S, Liu Y, et al: Generic diagramming

platform (GDP): A comprehensive database of high-quality biomedical

graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 53(D1): D1670–D1676. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|