Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative,

encapsulated, facultative anaerobic bacillus that has

conventionally been regarded as an opportunistic cause of

nosocomial infections, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections

and bacteremia (1). However, the

clinical image of this organism has entirely changed over the past

30 years (2). A new clinical

syndrome, community-acquired pyogenic liver abscess (PLA), mainly

due to hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp), was first noted

in Taiwan in the 1980s (3). As a

result, hvKp has spread worldwide and is now considered a

significant public health threat (4,5).

hvKp strains can cause severe, invasive disease in otherwise

healthy hosts, unlike classical K. pneumoniae (cKp), which

is typically isolated from immunocompromised patients in healthcare

settings (6). Monomicrobial liver

abscess, traditionally associated with capsular serotypes K1 and K2

[such as sequence type (ST) 23 and ST65], and metastatic

complications such as endophthalmitis, meningitis, septic pulmonary

emboli and necrotizing fasciitis, are clinical hallmarks (7). This shift reflects how a previously

opportunistic organism has evolved to cause invasive disease even

in healthy hosts (8).

K. pneumoniae expresses a wide range of

capsular (K) types, currently described as K1 through K80, encoded

by distinct cps loci (9). Although

>80 K types are recognized, certain serotypes are repeatedly

linked to invasive disease. K1 and K2 remain most strongly

associated with PLA and metastatic complications; additional

serotypes reported from severe or invasive infections include K5,

K20, K54 and K57 (10). These

serotypes frequently co-associate with key virulence loci such as

rmpA/rmpA2 and the aerobactin locus and characteristic sequence

types such as ST23 with K1 and ST65 with K2, explaining their

propensity for bloodstream invasion and metastatic spread (11). As this issue escalates, the spread

of multidrug resistance (MDR) in K. pneumoniae continues to

intensify, driven by extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)

production and, even more concerning, resistance to carbapenems

mediated by enzymes such as K. pneumoniae carbapenemase

(KPC) (12), New Delhi

metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) (13)

and OXA-48 carbapenemase (14).

Although hvKp strains are generally susceptible to most

antibiotics, worrisome cases have been reported of strains carrying

both hypervirulence plasmids and MDR determinants (15). The convergence of hypervirulence

and antimicrobial resistance represents an emerging global health

threat, leading to a critical therapeutic gap with few effective

treatment options available (16).

PLA due to K. pneumoniae differs from other abscesses, such

as polymicrobial or enteric abscesses (17).

Historically, the majority of liver abscesses were

secondary infections (such as to biliary obstruction or

intra-abdominal sepsis) and are typically polymicrobial (18). However, a recent study also

highlighted gastrointestinal colonization and translocation as

essential portals of entry, even in cryptogenic cases (19). Another example is the pathogenesis

of K. pneumoniae where a variety of specialized virulence

factors cooperate (20). A

hypermucoviscous polysaccharide capsule protects bacteria from

phagocytosis, iron-uptake siderophore systems sequestering iron

from the environmentally restrictive conditions of the mammalian

host [such as aerobactin, salmochelin, yersiniabactin (ybt) and

enterobactin], colonization factors (such as fimbriae and pili) and

lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which enables protection from

complement-mediated killing (21).

These mechanisms together result in K. pneumoniae invasion

and traversal across the gut barrier, subsequent colonization of

liver parenchyma, evasion of host immunity and dissemination to

remote organs (22).

The management of PLA typically involves a

combination of antimicrobial therapy and guided percutaneous

drainage of the abscess, based on clinical grounds (19). However, the emerging problem of

antimicrobial resistance, in conjunction with the invasive capacity

of hvKp, challenges treatment success and leads to higher morbidity

and mortality (4). In addition,

there is currently no licensed vaccine or approved anti-virulence

therapy available for treating this pathogen, emphasizing the need

for new approaches (23,24). In the present review a

comprehensive synthesis of the current knowledge of K.

pneumoniae-associated PLA is provided. The present review

begins with an overview of the epidemiology and clinical importance

of these emerging syndromes and summarizes virulence mechanisms and

host-pathogen interactions. Then, trends in antimicrobial

resistance are discussed, a narrative review of current therapeutic

approaches is provided and new concepts such as anti-virulence

therapies, immunotherapies and bacteriophage therapy are

introduced. Lastly, translational research opportunities and future

hurdles related to combating the combined threat of hypervirulence

and resistance are highlighted.

Epidemiology and emerging clinical

threats

Global burden of K. pneumoniae

infections

K. pneumoniae is one of the most frequently

isolated Gram-negative pathogens worldwide and the World Health

Organization has designated this bacterial species as a ‘critical

priority pathogen’ due to the dual MDR and hypervirulence threat it

poses (25). cKp has been a

long-standing pathogen of importance in the healthcare setting,

having been implicated in ventilator-associated pneumonia,

catheter-associated urinary tract infections, intra-abdominal

infections and bloodstream infections (26). K. pneumoniae has become the

focus of numerous challenging nosocomial epidemics as it possesses

the unique ability to rapidly capture resistance determinants,

ESBLs and carbapenemases (14). At

the same time, hvKp is a relatively recently recognized pathotype

and its emergence has significantly broadened the clinical spectrum

of K. pneumoniae infections (6).

hvKp was first identified in the 1980s in Taiwan and

it has become an international concern as a source of both

community-acquired and virulent invasive syndromes in both

immunocompromised and healthy hosts (4). Of these, PLA is the most typical and

clinically meaningful manifestation. Recent surveillance data

derived from multinational hospital-based surveillance networks and

national reporting systems from routine culture and genomic

analyses collected between 2020 and 2024 documented sporadic

autochthonous hvKp-PLA cases outside Asia, including South America

and Africa, suggesting that the global spread may be underestimated

due to underdiagnosis (4).

PLA as a distinct clinical entity

hvKp-associated PLA differs significantly from

classical polymicrobial liver abscesses (27). Traditionally, the majority of liver

abscesses develop as polymicrobial infections secondary to biliary

tract disease, appendicitis or intra-abdominal sepsis (18). By contrast, hvKp-PLA is generally

monomicrobial and more often cryptogenic, without an evident

underlying hepatobiliary abnormality or secondary cause (3). Capsular serotypes K1 and K2 account

for the majority of cases and sequence types ST23, ST65 and related

clones are predominant (9).

Patients classically present with acute fever, localized epigastric

or right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain, along with evidence of

systemic inflammation (28). A

hallmark of hvKp is its propensity for bacteremia with metastatic

spread, most commonly presenting as endogenous endophthalmitis,

central nervous system infections such as meningitis or brain

abscess, or pulmonary complications such as septic emboli or

pneumonia (29). Overall, hvKp-PLA

has lower mortality rates than polymicrobial abscesses if detected

and treated early; however, complications, including severe

morbidity, are common when either diagnosis or drainage is delayed

(19).

Risk factors and host

predispositions

Although hvKp can cause disease in healthy hosts,

several risk factors significantly predispose to disease (4). The most common and well-recognized

predisposing factor is diabetes mellitus; nearly all cohorts report

greater than half of PLA patients with underlying diabetes

(30). Experimental data indicate

that hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic

function, leading to impaired host defence (31). Chronic liver disease, cirrhosis,

malignancy and other immunosuppressive therapies are some other

factors that can contribute to vulnerability (32). However, hvKp is characterized by

its capacity to cause severe disease in hosts without obvious

comorbidities, contrasting with cKp infections, and challenging

long-held assumptions about host susceptibility (6). While hvKp can produce invasive

disease in healthy individuals, a number of comorbidities confer a

marked increase in risk, including diabetes mellitus (Table I).

| Table I.Host risk factors and the mechanistic

basis of susceptibility to K. pneumoniae-associated PLA. |

Table I.

Host risk factors and the mechanistic

basis of susceptibility to K. pneumoniae-associated PLA.

| First author,

year | Risk factor | Mechanistic

basis | Clinical

impact/prevalence | Remarks | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhang et al,

2025 | Diabetes

mellitus | Hyperglycemia

impairs neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis | Strongest and most

consistent risk factor (50–70% of hvKp PLA cases in Asian

cohorts) | Independent risk

for metastatic complications | (119) |

| Li et al,

2021 | Chronic liver

disease/cirrhosis | Impaired hepatic

innate immunity (Kupffer cell dysfunction) | Increased incidence

and poorer prognosis | Often coexists with

alcohol use or hepatitis | (70) |

| Kaur et al,

2018 | Malignancy | Disease and

chemotherapy cause immunosuppression | Higher

susceptibility and poorer outcomes | Common in elderly

patients | (62) |

| Pope et al,

2019 | Immunosuppressive

therapy | Reduced

innate/adaptive immunity | Risk of severe and

relapsing disease | Steroids, biologics

and post-transplant | (120) |

|

Thirugnanasambantham et al,

2025 | No comorbidity | hvKp can overcome

intact defences | Up to 30–40% of

hvKp PLA cases occur in otherwise healthy individuals | Key feature

distinguishing hvKp from cKp | (11) |

| Al Ismail et

al, 2025 | Microbiome

imbalance/colonization | hvKp intestinal

carriage increases the risk of translocation | 5–10% carriage

rates in Asia; lower but rising in Europe/N. America | Emerging risk

factor | (4) |

Although hvKp can infect otherwise healthy

individuals, epidemiological studies consistently identify certain

patient populations as being at higher risk of developing PLA and

other severe complications (4).

These include individuals with diabetes mellitus, both type 1 and

type 2, where impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytic

function contribute to increased susceptibility; patients with

chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, in whom hepatic immune

dysfunction and portal hypertension facilitate bacterial

dissemination; and immunocompromised individuals receiving systemic

corticosteroids, cytotoxic chemotherapy or biological immune

modulators (31). Increased risk

is also observed among patients with malignancies, those with

indwelling devices or a history of abdominal instrumentation that

disrupts mucosal barriers, as well as in the elderly and neonates,

where host defence mechanisms are often diminished (32). Notably, hvKp can occasionally cause

severe infections even in young, previously healthy individuals,

emphasizing that the absence of comorbidities does not preclude the

risk of invasive disease.

Geographical trends and strain

distribution

Epidemiology reveals a precise geographical

distribution associated with hvKp PLA (4). In East Asia, especially Taiwan,

China, South Korea and Singapore, hvKp has become the predominant

agent of community-acquired liver abscess (33). Initial cases described outside Asia

were predominantly associated with immigrants or travellers

(34). However, more recently,

autochthonous infections have been documented in Europe and North

America, indicating that hvKp is now establishing endemic

transmission in some non-Asian regions (35). As for South Asia, the Middle East

and Africa, fewer reports from these regions exist; however, this

is most likely due to a lack of recognition rather than an absence

(36). Surveillance from

developing nations, notably parts of South Asia, the Middle East

and selected African countries, indicates a complex image: A number

of reports show both classical MDR K. pneumoniae and hvKp

lineages, sometimes in mixed circulation (35). In South Asia, for example, hvKp

lineages (such as ST23) have been reported alongside ST11/ST15

clones carrying NDM or other carbapenemases, creating regional

hotspots for convergence events (36). Resource and capacity limitations

for routine molecular surveillance likely understate true incidence

in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Accordingly, terms such as ‘global trends’ should be

interpreted as geographically heterogeneous, with high burdens of

hvKp-PLA reported in East Asia, rising autochthonous cases in

high-income regions, and concerning reports of

resistance-associated hvKp from LMICs where surveillance is

improving (37). The lineage types

involved in PLA are also well-characterized using molecular

epidemiology, with ST23 (typically K1), ST65, ST86 and ST375 being

the most prominent lineages associated with PLA (10). The emergence of hvKp with its

virulence plasmids harbouring the rmpA gene and siderophore

biosynthesis clusters on different genetic backgrounds indicates

the genomic flexibility of hvKp for horizontal gene transfer and

genetic adaptation (11). Recent

genomic epidemiology studies also highlight convergence events

involving ST11 and ST15 lineages, which carry both carbapenem

resistance and virulence plasmids (36,37).

Notably, different geographical patterns have been documented, with

hvKp first described in East Asia but now found worldwide (Table II).

| Table II.Geographical distribution,

predominant strains and clinical features of K.

pneumoniae-associated PLA. |

Table II.

Geographical distribution,

predominant strains and clinical features of K.

pneumoniae-associated PLA.

| Region/country | Predominant

strains/serotypes | Major risk

factors | Distinctive

clinical features | Remarks/trends | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Taiwan, China,

South Korea and Singapore | K1 (ST23) and K2

(ST65 and ST86) | Diabetes, no

hepatobiliary disease | Monomicrobial PLA

and high metastatic rates (endophthalmitis and meningitis) | Endemic focus;

earliest recognition | (3,121) |

| North America and

Europe | K1, K2 and emerging

ST375 | Often in healthy

individuals and still common in diabetes | Increasing

autochthonous cases | Expanding

incidence; community-onset clusters | (118) |

| South Asia (India

and Pakistan) | Mixed strains;

including hvKp ST23 and ST11 (CR-hvKp) | Diabetes, cirrhosis

and malignancy | Resistant hvKp

reported | Rising

ESBL/NDM-positive hvKp | (36) |

| Middle East | Mixed strains (K1,

K2 and ST11) | Diabetes and

chronic liver disease | Increasing

carbapenemase producers (NDM and OXA-48) | Likely

underreported | (122) |

| Africa | Sparse data and

sporadic case reports | Unknown | Sporadic reports

only | Likely

underrecognized; limited data due to lack of diagnostic capacity

and surveillance infrastructure | (123) |

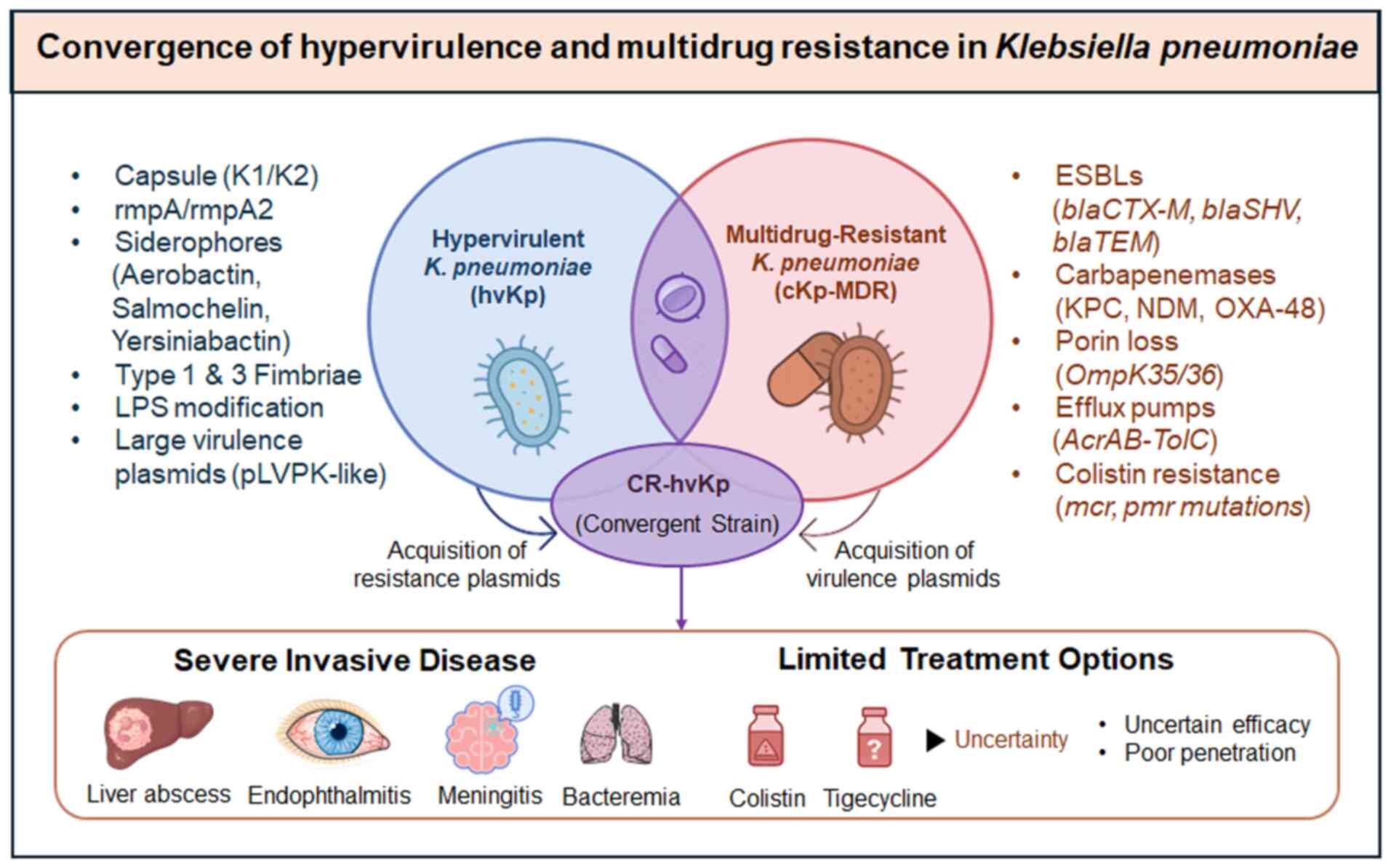

Convergence of hypervirulence and

antimicrobial resistance

Between the two critical epidemiological

developments, the global rise of hypervirulent hvKp strains and the

rapid spread of MDR among classical K. pneumoniae, the most

worrying is the convergence of hypervirulence and MDR. Despite

their invasive behaviour, hvKp strains were susceptible to most

antibiotics for a number of years, which allowed for high treatment

effectiveness (4). In comparison,

classical strains rapidly acquired resistance genes, such as ESBLs

and carbapenemases, including KPC, NDM and OXA-48 (38). However, researchers recently

reported hvKp isolates with those resistance genes in China, India,

Europe and North America (4,39).

These strains represent a worst-case scenario, as they combine

extensive drug resistance with high metastatic potential (40). Molecular studies have shown that

homologous mobile plasmids constitute a significant part of this

phenomenon, transferring resistance genes to hvKp lineages or

virulence genes to MDR classical strains (41,42).

However, the emergence of carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent K.

pneumoniae (CR-hvKp) has raised an urgent need for surveillance

and containment (42).

Clinical and public health

implications

The changing epidemiology of hvKp-associated PLA has

important implications for clinicians and public health. The

heterogeneous virulence of hvKp complicates diagnosis for

clinicians, as distinguishing hvKp from cKp is not straightforward

in routine clinical settings. While differential testing by the

hypermucoviscosity ‘string test’ is widely used, it is not

sensitive or specific and advanced molecular assays are still

limited in clinical routine (11).

Rapid molecular assays targeting aerobactin (iuc locus) or rmpA

genes have shown higher accuracy but remain largely confined to

research settings (43). The

emergence of hvKp with reduced susceptibility to the standard

antibiotic regimen (including image-guided drainage) is

progressively leading to therapeutic dilemmas (44). However, outside East Asia,

surveillance is often opportunistic, and the actual global burden

is likely underestimated due to underdiagnosis and limited

surveillance infrastructure outside Asia. Given its ability to

produce life-threatening, invasive disease in patients who were

previously healthy, coupled with its rapid acquisition of

antimicrobial resistance, hvKp has the potential to become a

pandemic organism. The global emergence of hvKp exemplifies how a

classical opportunistic pathogen has evolved from being community

and healthcare-associated to becoming a significant threat with

consequences far beyond liver abscess.

Pathogenesis and virulence mechanisms

The liver abscesses caused by hvKp result from

multiple virulence mechanisms (33). These virulence determinants, which

include polysaccharide capsule, siderophore systems, adhesins, LPS

modifications and plasmid-encoded factors, exhibit 2- to 1,000-fold

upregulated expression in vivo (45). This section will evaluate these

mechanisms in-depth.

Capsule and hypermucoviscosity

phenotype

The polysaccharide capsule may be the most unique

virulence factor of K. pneumoniae (46). Hypermucoviscous capsule production

(commonly evaluated with the ‘string test’) is one of the markers

that is highly associated with hvKp (47). Capsule regulators rmpA and rmpA2,

encoded on large virulence plasmids, primarily control this

phenotype (48). K1 and K2

serotypes typically form very mucoid capsules that are resistant to

phagocytosis and the complement system. The hypermucoviscous

phenotype is lost in rmpA/rmpA2 mutants and the virulence of these

mutants is impaired in animal models (49). Additionally, the capsule prevents

neutrophil phagocytosis and protects the organism from recognition

by antibodies (50). A recent

narrative review showed that sequencing studies have identified

structural differences in capsular operons between hvKp and cKp,

which may contribute to the enhanced virulence of hvKp (11).

Siderophore-mediated iron

acquisition

Although iron is a mineral that bacteria need to

grow, it is locked away by host proteins, including transferrin and

lactoferrin (51). The high

affinity siderophores produced by K. pneumoniae enable it to

bypass this nutritional immunity. Hypervirulent strains encode

multiple iron acquisition systems (such as enterobactin, ybt,

salmochelin and aerobactin), with aerobactin being nearly universal

and the most critical for hvKp virulence in PLA (52). Siderophores mediate bacterial

expansion in liver parenchyma and blood by rapidly scavenging iron

from the host environment (53).

Besides iron acquisition, certain siderophores serve as

immunomodulators, leading to oxidative stress and a diminished

responses from neutrophils (54).

The redundancy affords hvKp with a significant evolutionary

advantage in a host environment where nutrients are often limited.

Recent studies also suggest that aerobactin expression correlates

with increased metastatic potential and poorer clinical outcomes

(33,55).

Fimbrial adhesins and

colonization

Fimbriae play a crucial role in the initial

attachment to host tissues (22).

At present, type 1 and type 3 fimbriae in K. pneumoniae have

been best characterized. Type 1 fimbriae allow binding to

mannose-containing receptors on epithelial cells, whereas type 3

fimbriae promote biofilm formation individually or on biotic and

abiotic surfaces, including medical devices. Fimbrial adhesins have

been shown to promote gastrointestinal colonization of bacteria and

increase the likelihood of translocating microbes through the

intestinal mucosa into the portal circulation, potentially

facilitating the formation of liver abscesses (22). Once in the liver, fimbriae

facilitate adhesion to hepatic tissue, allowing for persistence and

the formation of abscesses. Together with capsule and siderophores,

these adhesive structures enable hvKp to establish a robust

infection niche. K. pneumoniae employs a wide array of

virulence factors, from capsule, siderophores, fimbrial adhesins

and LPSs (Table III).

| Table III.Major virulence determinants of K.

pneumoniae in PLA. |

Table III.

Major virulence determinants of K.

pneumoniae in PLA.

| First author,

year | Virulence

factor | Genetic basis | Role in

pathogenesis | Clinical

relevance | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhu et al,

2021 | Capsule (K1 and

K2;) hypermucoviscosity | cps locus;

rmpA/rmpA2 | Resistance to

phagocytosis, inhibition of complement activation leading to serum

resistance and enhanced bloodstream survival | Strongly associated

with invasive PLA and metastatic spread; vaccine/antibody

target | (59) |

| Monteiro et

al, 2024 | Siderophores

(aerobactin, salmochelin, yersiniabactin and enterobactin) | iuc, iro, ybt and

ent loci | Iron acquisition;

immune modulation; oxidative stress induction | Aerobactin nearly

universal in hvKp PLA strains; candidate for anti-virulence

therapy | (124) |

| Clegg and Murphy,

2017 | Fimbrial adhesins

(Type 1 and 3 fimbriae) | fim and mrk

operons | Colonization of

gut; adherence in liver; biofilm formation | Facilitate

gut-to-liver translocation | (20) |

| Miller et

al, 2024 |

Lipopolysaccharide | waa gene

cluster | Resistance to serum

killing; immune modulation | Contributes to

serum survival and sepsis severity | (105) |

| Liao et al,

2024 | Virulence

plasmids | pLVPK-like plasmids

(~200 kb) | Encode capsule

regulators (rmpA/rmpA2) and siderophores | Horizontal transfer

spreads hypervirulence traits | (125) |

| Lam et al,

2018 | Pathogenicity

islands | ICEKp elements (ybt

and clb) | Iron scavenging

(ybt) and genotoxicity (colibactin) | Colibactin linked

to DNA damage and possible cancer risk | (126) |

| Bossuet-Greif et

al, 2018 | Colibactin | clb genes on

ICEKp | Genotoxic effects

and DNA damage in host cells | Recently linked to

colorectal cancer; under study | (127) |

LPS and immune evasion

The LPS of K. pneumoniae also protects

bacteria from complement-mediated lysis, thereby contributing to

its pathogenesis (56). Various

O-antigen structures of LPS directly impact serum resistance and

binding by host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (57). HvKp strains are proposed to have

adapted LPS that confer serum resistance, with the capsule playing

a protective role simultaneously. Beyond structural defence, LPS is

a potent inducer of inflammation, driving hepatocellular injury and

systemic inflammatory responses that exacerbate PLA severity

(58).

Virulence plasmids and mobile genetic

elements

Most hvKp virulence factors are encoded on large

virulence plasmids (200–220 kb) (59). Such plasmids encode genes for

rmpA/rmpA2 and the aerobactin (iuc locus), salmochelin (iro locus)

and other accessory factors (60).

This is especially concerning since their horizontal mobility

enables transfer of hypervirulence traits to classical MDR strains,

producing the so-called convergence phenotype. In addition, hvKp

virulence is further expanded by chromosomal pathogenicity islands,

including those coding for ybt and colibactin (clb), which provide

unique mechanisms for iron acquisition and genotoxicity,

respectively (6). A study has

linked clb production to colorectal carcinogenesis, highlighting

potential long-term sequelae of hvKp colonization (61). The adaptability and clinical

success of hvKp stems from the complex interplay among plasmids,

pathogenicity islands and host genomic backgrounds.

Mechanistic basis of liver abscess

formation

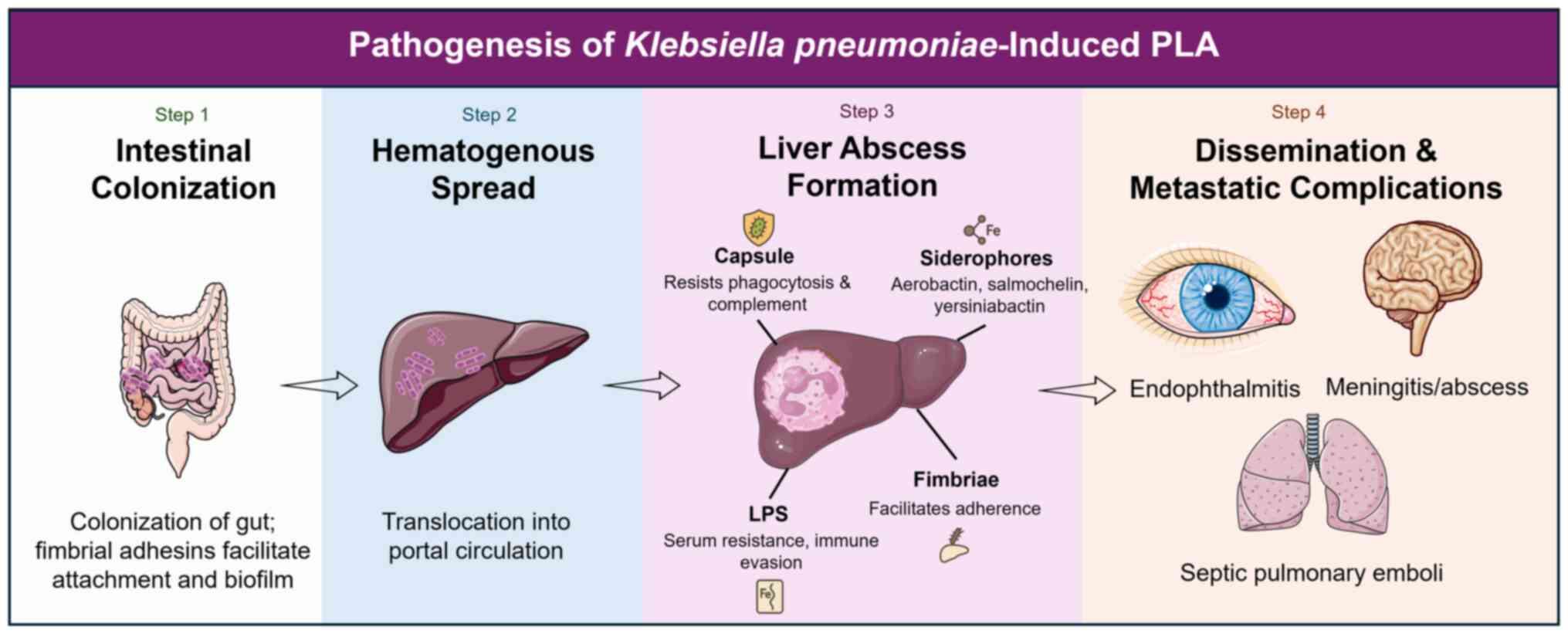

PLA is the result of a series of microbial-host

interactions that lead to disease pathogenesis (17). The initial reservoir is intestinal

colonization, followed by bacterial translocation into the portal

venous circulation (3). The hvKp

capsule and LPS facilitate the avoidance of phagocytic clearance

once the bacterium reaches the liver (50). The production of siderophores

ensures survival in the iron-limited hepatic microenvironment and

fimbrial adhesins facilitate tissue adherence (51). Neutrophil and macrophage

recruitment lead to regional inflammation, necrosis and the

formation of an abscess cavity (31). By contrast, hvKp liver abscesses

are almost always monomicrobial rather than polymicrobial, as is

the case for most abscesses caused by anaerobes and enteric flora,

emphasizing the intrinsic capacity of the pathogen to establish

infection independently (33). The

rapidity of metastasis in these patients is therefore closely

related to the ability of hvKp to penetrate the bloodstream and

disseminate systemically via its capsule and plasmid-borne

virulence arsenal. Virulence factors, including capsule,

siderophores, fimbrial adhesins and LPS, work together to

facilitate colonization of the liver, evade the immune response and

promote systemic spread (Fig.

1).

Host-pathogen interactions and disease

manifestation

Colonization of the host by K. pneumoniae and

subsequent progression to PLA are multifaceted processes involving

the interplay of virulence factors and immune responses of the host

(22). Such hypervirulent strains

appear to have developed mechanisms that enable them to both evade

immune clearance and exploit host physiological weaknesses, thereby

facilitating invasive disease with metastatic sequelae. This

section elaborates on the mechanisms of maintaining virulence while

evading both innate and adaptive immunity, ultimately culminating

in hepatic invasion, abscess formation and systemic

complications.

Hepatic invasion and abscess

formation

K. pneumoniae translocates from the

gastrointestinal tract and reaches the liver via portal circulation

(62). The gastrointestinal

mucosa, especially during dysbiosis or increased permeability,

serves as a significant reservoir. After entering the portal venous

system, hypervirulent strains are not phagocytosed or killed by

complement as they possess a thick polysaccharide capsule and a

hypermucoid phenotype (63). This

allows the bacterium to survive in the bloodstream and seed hepatic

tissues. In the liver parenchyma, bacteria attach to hepatocytes

and endothelial cells through fimbrial adhesins, and iron

acquisition through siderophores promotes bacterial replication in

the iron-limited hepatic microenvironment (64). With advancing infection, this leads

to local necrosis and tissue liquefaction, promoted by bacterial

toxins and host mediators of inflammation. The result is the

development of defined abscess cavities filled with pus material,

often multiloculated, which may increase in size or number.

Innate immune responses

Innate immune cells are abundant in the liver,

including Kupffer cells, neutrophils and natural killer cells,

which form the first line of defence against invading pathogens

(65). PRRs recognize bacterial

components, such as LPS and capsular polysaccharides, initiating an

inflammatory cascade that is associated with cytokine release and

the recruitment of neutrophils (66). Nevertheless, hypervirulent K.

pneumoniae strains evade neutrophil extracellular traps,

inhibit complement activation and resist phagocytosis, thereby

allowing them to persist in hepatic tissue. Neutrophils are a

hallmark of PLA pathophysiology; however, excessive neutrophil

accumulation contributes to collateral tissue injury, hepatocyte

necrosis and the progression of abscesses (67). Similarly, with the activation of

Kupffer cells, pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced, which

enhance local inflammation but typically do not clear the pathogen

from the liver (68). This

inappropriate immune reaction leads to an environment that favours

bacterial persistence and abscess maturation.

Adaptive immune responses

The adaptive immune system plays a crucial role in

containing and clearing liver abscesses (33). Antibody-mediated responses against

capsular polysaccharides and siderophores enhance

opsonophagocytosis, while T cell-mediated immunity contributes to

bacterial clearance. However, in individuals with diabetes, chronic

liver disease or immunosuppression, adaptive immune responses are

impaired, resulting in dysregulated bacterial growth and severe

disease (66). The diversity of

capsule and antigenic variability makes hypervirulent strains

unusually adept at evading antibody-mediated recognition.

Additionally, bacterial metabolites and endotoxins may suppress

adaptive immunity, thereby prolonging the infection and

facilitating its dissemination (66).

Metastatic infections and extrahepatic

complications

A hallmark of hvKp-mediated PLA is its ability to

induce metastatic infections at non-contiguous sites (66). Through bacteremia, it can spread to

the eyes, central nervous system, lungs and other organs.

Endophthalmitis (often leading to irreversible vision loss),

meningitis and brain abscesses are among the most devastating

complications, associated with high morbidity and mortality

(69). These processes are

critical mechanisms driving metastatic spread, including complement

resistance, neutrophil resistance and vascular invasion. The

metabolic flexibility enabled by siderophore systems supports

survival in these nutrient-limited niches, such as the vitreous

humour and cerebrospinal fluid. The ability to disseminate despite

host immune defences underscores the enhanced virulence potential

of hvKp compared with cKp.

Clinical outcomes and prognosis

K. pneumoniae PLA can present from simple

localized hepatic abscesses with fever and abdominal pain to

fulminant sepsis with multi-organ involvement (18). Therapy and prognosis are influenced

by three key factors: The immune status of the host, bacterial

virulence and the timing of intervention. Older patients, patients

with diabetes and patients with underlying liver disease are

predisposed towards severe disease and poor outcomes. Patients with

resistant infections, metastatic complications or delayed diagnosis

experience substantially higher mortality (70). The host-pathogen interactions

underlying hvKp-mediated PLA are ultimately defined by a

combination of the evasion of the pathogen from the innate and

adaptive immunity, the immunological background of the host and the

fine line between protective inflammation and harmful immune

pathologies (29). Understanding

these interactions is essential for designing targeted therapies

that bolster host defences while neutralizing bacterial

virulence.

Antimicrobial resistance in K. pneumoniae

PLA

K. pneumoniae PLA is becoming increasingly

challenging to treat due to the widespread emergence of

antimicrobial resistance (19).

The division between hypervirulent strains, which were initially

mostly susceptible to most antibiotics, and classical strains,

which were primarily associated with MDR in a nosocomial

background, is also no longer absolute. Hypervirulent and resistant

strains are increasingly appearing, posing a significant

therapeutic challenge (4). This

section summarizes current resistance patterns, mechanisms and

clinical consequences specific to PLA.

Global resistance trends

Antimicrobial resistance in K. pneumoniae has

been reported worldwide, with the highest prevalence observed in

regions where PLA is endemic (71). The increase in ESBL production of

K. pneumoniae is particularly high in East and Southeast

Asia, where multidrug class co-resistance is common (72). Carbapenem-resistant K.

pneumoniae (CRKP) has also emerged globally, driven by

carbapenemases such as KPC (prevalent in the Americas and Europe),

NDM (dominant in the Indian subcontinent) and OXA-48-like enzymes

(common in the Middle East and Europe) (73,74).

Resistance genes have begun to emerge in a significant proportion

of hvKp isolates associated with liver abscesses (27). The rate surpassed 20% in the

networks for ESBL-hvKp-PLA strains in both China and Taiwan between

2020 and 2024 (75). Although

fundamentally uncommon, carbapenem resistance is increasingly

reported in hvKp-PLA, particularly among healthcare-associated

cases or in endemic countries with CRKP (76). A surveillance study has indicated

that up to 10–15% of hvKp isolates in China and India now harbour

carbapenemase genes, reflecting a rising convergence of resistance

and hypervirulence (73).

Mechanisms of resistance

Resistant mechanisms in K. pneumoniae are

heterogeneous and often act cooperatively to produce strong MDR

profiles (77). The most common

mechanism is the production of β-lactamases, including ESBLs and

carbapenemases, which inactivate extended-spectrum cephalosporins

and carbapenems (78). Resistance

to β-lactam class antibiotics typically develops from ESBLs, such

as Cefotaximase-Munich (CTX-M) and sulfhydryl variable, and

carbapenemases, such as KPC, NDM, OXA-48 and Verona

integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase (79). These enzymes are often accompanied

by porin loss (OmpK35/36) and upregulation of efflux pumps, thereby

enhancing resistance. Plasmids containing blaCTX-M and

blaKPC are frequently associated with fluoroquinolone and

aminoglycoside resistance genes (80). A broader concern regarding salvage

therapy is the development of colistin and tigecycline resistance,

which can occur via mcr genes or chromosomal alterations in the

case of colistin, and through ramR mutations or efflux pumps in the

case of tigecycline, in K. pneumoniae in general (81). The development of mutations or loss

of outer membrane porins, particularly OmpK35 and OmpK36, results

in a decrease in drug permeability, thereby increasing the potency

of β-lactamase activity (82).

Efflux pumps, such as the AcrAB-TolC system, when upregulated,

render lower intracellular concentrations of numerous antibiotic

classes, which also include fluoroquinolones and tigecycline

(83). Aminoglycoside resistance

typically arises from enzymatic modification or ribosomal

methylation. By contrast, colistin resistance develops through

plasmid-borne mcr genes or chromosomal regulatory mutations

resulting from chromosomal alterations in the regulatory pathways

or the acquisition of plasmid-borne mcr genes (84). This can occur in a single isolate,

resulting in organisms that are resistant to nearly all clinically

available antibiotics. Resistance mechanisms, including β-lactamase

production, porin loss and efflux pumps, act synergistically

(Table IV).

| Table IV.Major antimicrobial resistance

mechanisms in K. pneumoniae and their clinical

implications. |

Table IV.

Major antimicrobial resistance

mechanisms in K. pneumoniae and their clinical

implications.

| Resistance

mechanism | Genetic basis | Antibiotic classes

affected | Clinical

relevance |

|---|

| Extended-spectrum

β-lactamases | blaCTX-M,

blaSHV and blaTEM | Third generation

cephalosporins | Undermines

cephalosporin therapy; common in Asia (30–50%) |

| Carbapenemases | KPC, NDM, OXA-48

and VIM | Carbapenems | Critical driver of

CR-hvKp; global spread |

| Porin loss

(OmpK35/36) | Chromosomal

mutations | β-lactams and

carbapenems | Enhances

β-lactamase resistance |

| Efflux pumps

(AcrAB-TolC) | Regulatory

mutations | Fluoroquinolones

and tigecycline | Contributes to MDR

profiles |

| Aminoglycoside

resistance | AMEs and armA

methyltransferase |

Aminoglycosides | Limits the use of

amikacin/gentamicin |

| Colistin

resistance | mcr plasmid genes

and pmrA/B mutations | Colistin (last

line) | Increasingly

reported, especially in Asia and the Middle East |

| Fosfomycin

resistance | fosA gene

(plasmid-borne) | Fosfomycin | Emerging, limits

use in urinary/liver infections |

Convergence of hypervirulence and

MDR

A growing and serious threat is the convergence of

hypervirulence with MDR (6,25).

Hypervirulent strains, known for causing severe disease with

metastatic complications, were long considered manageable due to

their susceptibility to antibiotics, providing clinicians with an

essential therapeutic window. However, this advantage is rapidly

diminishing as hypervirulent strains acquire plasmids carrying

ESBLs and carbapenemases (35).

This convergence is not an isolated event, but a global problem, as

evidenced by reports of outbreaks caused by carbapenem-resistant

hypervirulent strains. hvKp and MDR-cKp lineages have historically

circulated separately, but recent plasmid exchanges are blurring

this distinction (85).

Nonetheless, recent surveillance data have described hvKp strains,

often ST23 or ST11 clones, that have acquired ESBL or carbapenemase

genes on plasmids (86,87). The transfer of plasmids and the

integration of resistance loci into the chromosomal genome drive

this convergence. Some examples include hvKp isolates associated

with blaNDM or blaKPC, which have been reported from

China and India, with some found in the absence of PLA in Europe.

The recent rise of strains with simultaneous hypervirulent (K1/K2

capsule, aerobactin) and carbapenem-resistant traits has been

coined as ‘hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae

(hv-CRKP)’ with global alerts issued (10). Such convergence is illustrated in

Fig. 2, which contrasts the

historical separation of cKp and hvKp, as well as the recent

emergence of CR-hvKp due to the plasmid-mediated exchange of

resistance or virulence determinants (88). These hybrid strains exhibit the

worst aspects of both phenotypes and pose a significant clinical

and public health challenge.

Clinical implications of resistance in

liver abscess

Antimicrobial resistance notably affects the

clinical presentation and treatment of liver abscesses (33). Empirical therapy with

cephalosporins often fails in areas with high ESBL prevalence,

resulting in delayed bacterial clearance and adverse outcomes

(33). This leaves few options,

especially with carbapenem resistance, frequently restricting

clinicians to last-line drugs such as colistin and tigecycline.

However, both agents have limitations, such as poor penetration

into abscess spaces, toxicity and variable efficacy (33). Consequently, patients with

resistant infections may require more extended hospital stays,

combination regimens with complex and challenging combinations and

invasive procedures. Outcomes are particularly poor in hvKp strains

that are also multidrug resistant, as they are strongly associated

with bacteremia, septic shock, metastatic complications and high

mortality.

Limitations of current antibiotic

therapies

The treatment of K. pneumoniae PLA with

conventional antibiotic therapy has become less reliable in recent

years (33). The widespread

resistance against once highly effective third-generation

cephalosporins and carbapenems is undermining this progress

(89). Target-site mutations and

efflux contribute to fluoroquinolone resistance, and

aminoglycosides are destroyed by enzymatic modification. Colistin,

otherwise a last-line antibiotic, faces increasing resistance, as

well as nephrotoxicity and uncertain effects in liver abscesses

(45). In addition to emerging

resistance, several commonly used agents have clinically important

adverse effects and pharmacological limitations that influence

therapeutic decision-making in PLA. Colistin is nephrotoxic and its

pharmacodynamics in poorly vascularized abscess cavities are

uncertain; renal adverse effects often limit dose escalation

(90). Tigecycline has poor serum

concentrations, can cause significant gastrointestinal side effects

and has been associated with increased mortality signals in a

meta-analysis; its penetration into abscess cavities is variable

and often suboptimal (91).

Aminoglycosides have nephro- and ototoxicity risks

that restrict prolonged use, and β-lactams, including many

third-generation cephalosporins and even carbapenems, may

inadequately penetrate the necrotic centre of large, poorly

vascularized abscesses (92).

These adverse events and pharmacokinetic limitations, such as

reduced vascular delivery, high protein binding and sequestration

in necrotic material, help explain treatment failures and motivate

alternative local or adjunctive delivery strategies, such as

intra-cavitary instillation and drug-eluting devices (93). A number of antibiotics have

pharmacokinetics that limit their penetration into abscess

cavities, thereby complicating complete eradication (93). This bottleneck highlights the need

for alternative strategies that target both antimicrobial

resistance mechanisms and the pathogenic potential of hypervirulent

strains, beyond classical antibiotics.

Current therapeutic approaches

Management of K. pneumoniae PLA involves a

combination of empirical antimicrobial therapy and interventional

procedures that target abscess drainage. Although the early

initiation of antibiotics is crucial, the rising prevalence of

antimicrobial resistance complicates the choice of empirical

regimens. Source control, which is often required for definitive

cure, is also obtained with the aid of interventional radiology and

surgical procedures.

Antimicrobial therapy

Empirical antibiotic therapy for PLA is initiated as

soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, with adjustments made based on

culture and susceptibility results (94). Third-generation cephalosporins,

such as ceftriaxone or ceftazidime, have historically been the

preferred choice due to their effectiveness against susceptible

strains and adequate biliary penetration (95). However, in areas of high ESBL

prevalence, carbapenems have frequently been used as first-line

therapy. Carbapenem resistance has further complicated management,

leaving tigecycline, colistin and, in some instances,

aminoglycosides as the only alternative agents (73). Combination therapy is often

employed in severe or resistant infections, although supporting

evidence remains limited. Carbapenems may also be used in

combination with aminoglycosides or fluoroquinolones to facilitate

bacterial clearance, although the evidence for these combination

regimens is mixed.

For MDR or extensively drug-resistant strains,

salvage therapies such as colistin-tigecycline combinations are

occasionally used, although concerns are present regarding efficacy

and toxicity (95). The length of

antimicrobial treatment ranges from weeks to months, depending upon

clinical condition, radiological resolution of the abscess and

clearance of microbiological measures. The pharmacokinetics of

antimicrobials represent a crucial aspect of managing PLA (96). Therapeutic concentrations of

antibiotics are not only in the blood but also in hepatic tissue

and the abscess cavity. The encapsulated nature of liver abscesses

and necrotic material can limit the penetration of drugs requiring

long-course treatment, and in most cases, also drainage procedures

(97).

The efficacy of antibiotic therapy in PLA depends

not only on systemic susceptibility profiles but also on achieving

effective drug concentrations within the abscess cavity (19). Several pathophysiological factors

can markedly reduce intra-cavitary antibiotic exposure, including

poor vascularity and the presence of necrotic debris that impede

drug delivery, the high protein and lipid content of abscess

material can bind and inactivate antimicrobials and acidic or

hypoxic microenvironments that alter drug activity (96). Although β-lactams generally attain

favourable biliary and hepatic tissue concentrations, their

penetration into poorly perfused abscess cores may remain

suboptimal (97). Lipophilic

agents such as, tigecycline may distribute to hepatic tissue but

often display low serum concentrations; conversely, aminoglycosides

have limited penetration into abscess fluid (91,92).

Local pharmacokinetic studies are limited, but measured

abscess/plasma ratios have shown substantial variability across

agents and individual patients (92). These limitations provide a

rationale for local delivery approaches such as intra-cavitary

instillation, catheter-directed infusion or drug-eluting beads and

for tailoring systemic therapy guided by

pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic principles when possible.

Interventional management

Besides antibiotics, drainage of the abscess is an

essential form of source control (98). Ultrasonography or computed

tomography-guided percutaneous catheter drainage is the standard of

care for the majority of cases and has replaced open surgical

approaches in most cases (99).

Drainage reduces bacterial load and relieves pressure from

expanding cavities, thereby enhancing antibiotic penetration and

alleviating mass effect. The drainage will be based on the

size/number and location as well as the clinical condition of the

patient. However, small abscesses of <3 cm may be managed with

antibiotics alone and close follow-up (19). Percutaneous drainage is typically

needed for larger abscesses, multiloculated cavities or abscesses

that show a poor response to medical therapy. Surgical drainage is

reserved for complicated cases, including multiloculated abscesses,

failed percutaneous drainage, rupture or perforation with

peritonitis (100). Both

diagnosis and management are imaging centred. Ultrasonography is

frequently used for initial diagnosis and to guide drainage

procedures, while computed tomography has higher sensitivity for

diagnosing abscess formation, especially in cases of multiple or

small lesions. Imaging follow-up is also necessary to assess both

response to treatment and to identify recurrence.

Integrated management

considerations

Prompt intervention combined with appropriate

antibiotics is the optimal treatment for K. pneumoniae PLA,

which requires a multidisciplinary approach (101). Glycaemic control and supportive

care are crucial for managing diabetes and other comorbidities, as

they significantly impact outcomes in such scenarios (102). Management also focuses on

preventing complications such as sepsis, metastatic spread and

organ failure. The identification of resistant organisms and the

prompt modification of antimicrobial therapy play crucial roles,

with delays in effective treatment being closely linked to patient

outcomes. Despite advances in diagnostic imaging and interventional

radiology, morbidity and mortality remain high, especially in MDR

infections and hvKp strains with metastatic spread. These

limitations underscore the critical need for innovative treatment

modalities that move beyond standard antibiotics and drainage

steps, setting the stage for the forthcoming innovative strategies

addressed in the next section.

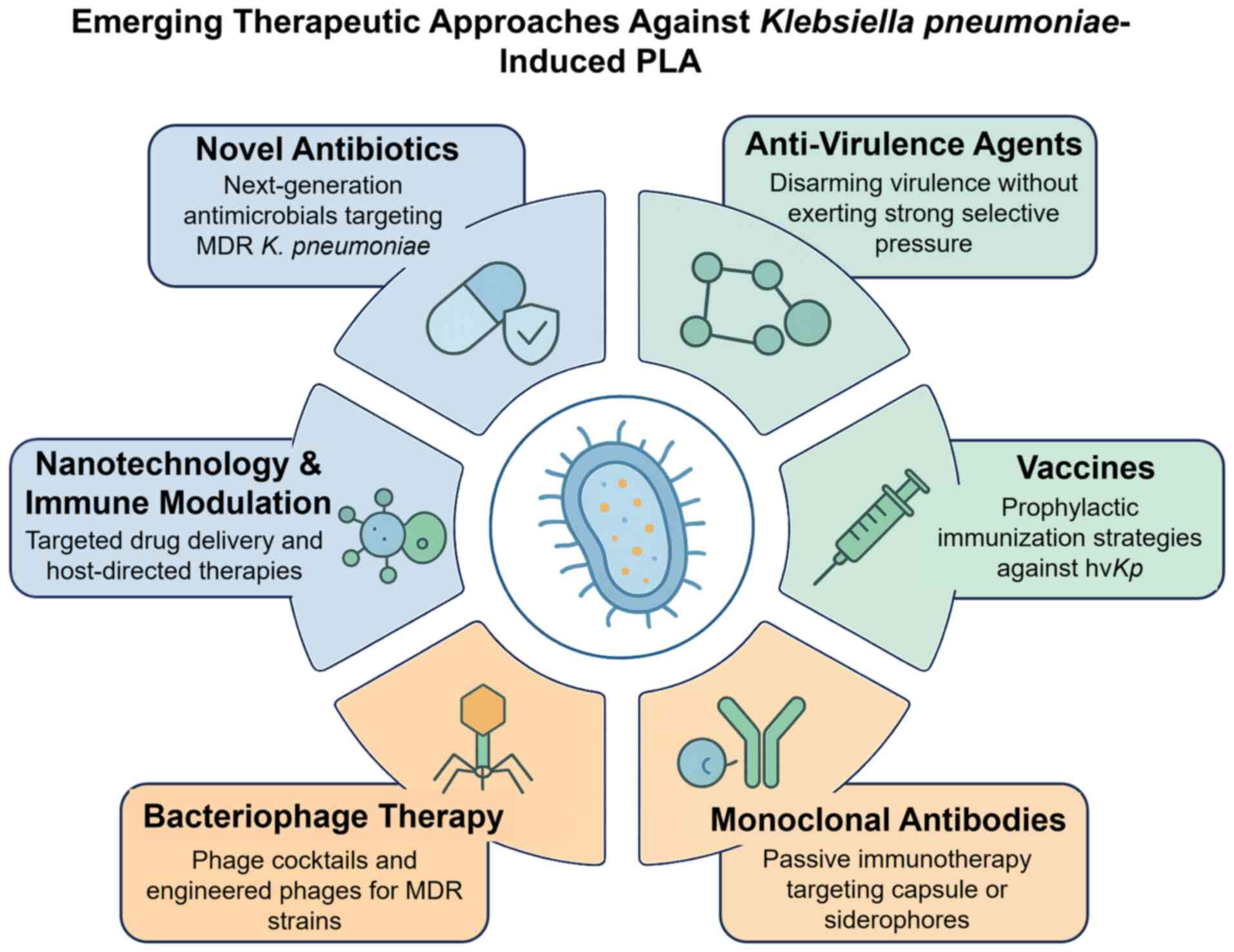

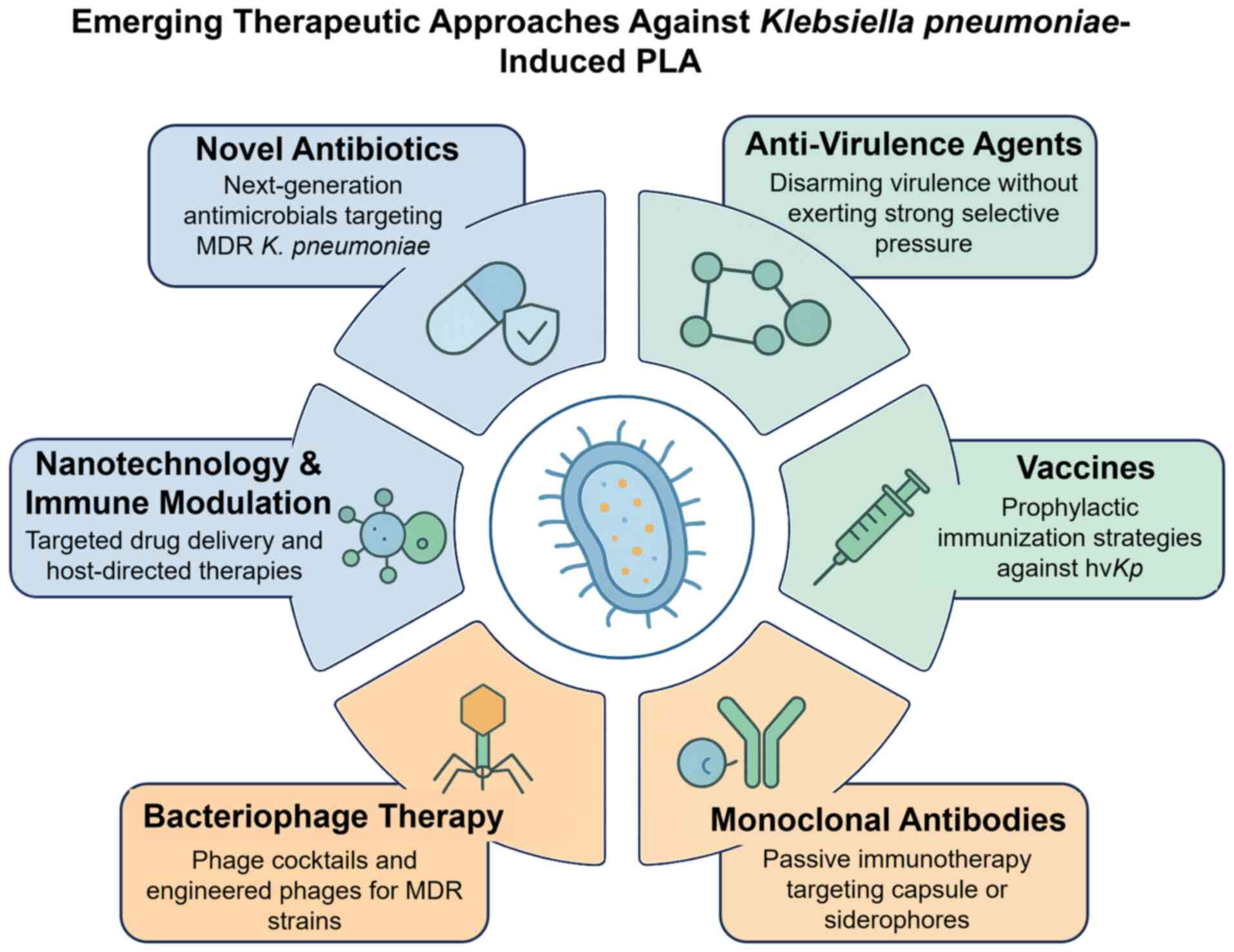

Emerging and experimental therapeutic

strategies

The limitations of traditional antibiotic

treatments, combined with the notable increase in the incidence of

MDR strains of K. pneumoniae, have sparked renewed interest

in novel and complementary therapeutic approaches (101). These emerging approaches aim not

only to circumvent resistance but also to neutralize virulence and

strengthen host defences (103).

Other antimicrobial approaches, such as exploring new

antimicrobials and anti-virulence agents, immunotherapies and

biological modalities, including bacteriophage and microbiome

interventions, remain under consideration for the treatment of PLA

due to K. pneumoniae (14).

Novel antibiotics and combination

therapies

Novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations

and non-β-lactam antibiotics have been developed in response to the

global spread of CRKP (104). For

KPC-producing strains, ceftazidime-avibactam and

meropenem-vaborbactam target KPC, and imipenem-relebactam extends

the coverage against some OXA-48 producers (38). Cefiderocol, a

siderophore-cephalosporin, demonstrates potent activity against

carbapenemase-producing bacteria via iron uptake pathways (103). Nonetheless, resistance is

reported to emerge to ceftazidime-avibactam in KPC-CRKP, warranting

stewardship. Other options include newer tetracycline derivatives

(such as eravacycline) and aminoglycoside formulations (such as

plazomicin), for which limited experience is available in PLA.

Anti-virulence approaches

Considering that hypervirulent strains do not

merely cause a more severe disease by being more resistant, but

have evolved a different set of pathogenic weapons, developing

therapies to neutralize these virulence factors provides an

appealing approach. Inhibition of capsule biosynthesis has been

explored to destabilize the protective layer that protects bacteria

from the host immune system (66).

Agents targeting siderophore systems prevent bacterial access to

iron, a key nutrient for survival and dissemination. Additionally,

the disruption of biofilm formation and quorum sensing, which

promote persistence and help avoid host responses, are also

promising targets. Although they may not eradicate bacteria

directly, anti-virulence therapies can render pathogens more

susceptible to immune clearance, thereby enhancing the efficacy of

companion antibiotics.

Immunotherapy and vaccine

development

Another promising direction involves immunological

strategies (50). An animal study

has demonstrated that monoclonal antibodies against capsular

polysaccharides, LPSs or siderophores enhance opsonophagocytosis

and provide passive protection (105). K1 and K2 serotypes, which are

most often implicated in hypervirulent liver abscess strains, are

primary targets of whole-cell and subunit vaccines being developed

as part of vaccination efforts (106). Preclinical and early clinical

studies suggest that immunization may provide long-lasting

protection in at-risk populations, such as individuals with

diabetes or chronic liver disease; however, no vaccine has yet been

licensed (23,106). Phase I/II trials of K1/K2

capsule-based vaccines and siderophore-conjugate vaccines are

ongoing, but clinical translation remains pending (107). Host-directed immunotherapies

target not only the pathogen but also aim to augment the innate

immune responses of the host and correct the disturbed immunity,

thereby tipping the host-pathogen balance in favour of bacterial

clearance.

Bacteriophage therapy and

phage-derived enzymes

Bacteriophage therapy has resurfaced as a potential

treatment for MDR K. pneumoniae infections, similar to the

scope of PLA (108). Natural

phages against hypervirulent strains have been effective in

preclinical studies, rapidly lysing bacteria resistant to

antibiotics (109,110). Phage cocktails are being explored

to mitigate resistance development, with early clinical trials now

underway (110). Moreover,

phage-derived lysins, enzymes that degrade bacterial cell walls,

also represent a promising strategy with broad lytic activity and

the ability to work synergistically with antibiotics. Although

phage-host specificity, regulatory considerations and in

vivo efficacy remain challenges, clinical case reports

demonstrate the potential of phage therapy to be lifesaving when

conventional treatment fails.

Microbiome-based and adjunctive

strategies

K. pneumoniae is a part of the gut

microbiota and its changes may initiate systemic invasion (22). This has sparked interest in

microbiome-targeted therapies, including probiotics and faecal

microbiota transplantation, to restore microbial balance and reduce

hvKp colonization. CRISPR, for example, is being explored not just

as a genomic editing tool that works at the gene-targeting level,

such as virulence determinants or resistance genes, but also as a

programmable antimicrobial system capable of selectively

eliminating resistant or hypervirulent bacteria while sparing

commensal flora (111). While

they are still experimental, these strategies represent new

approaches to reduce pathogen load and prevent reinfection.

CRISPR-based antimicrobials are also being investigated as

precision tools to target resistance or virulence genes in hvKp

selectively (103). The

management of K. pneumoniae PLA involves a combination of

antibiotics and drainage; however, new strategies are currently

under active investigation, including β-lactam/β-lactamase

inhibitors, cefiderocol, vaccines and phage therapy (Table V) (103). Fig.

3 highlights therapeutic strategies against K.

pneumoniae-induced PLA.

| Figure 3.Emerging therapeutic approaches

against Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced PLA. The central

illustration shows hypervirulent, drug-resistant K.

pneumoniae with capsule, pili and siderophores. Surrounding

panels highlight six strategies: Novel antibiotics, anti-virulence

agents, vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, bacteriophage therapy and

nanotechnology/immune modulation. Colour codes indicate

antibiotic-based (blue), immune/vaccine-based (green) and

innovative approaches (orange). PLA, pyogenic liver abscess; MDR,

multidrug resistance; hvKp, hypervirulent Klebsiella

pneumoniae. |

| Table V.Current and emerging therapeutic

strategies for K. pneumoniae PLA. |

Table V.

Current and emerging therapeutic

strategies for K. pneumoniae PLA.

| Strategy | Mechanism of

action | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical

status |

|---|

| Cephalosporins

(Third generation) | Inhibit cell wall

synthesis | Effective if

susceptible | ESBL undermines

efficacy | Routine use;

declining efficacy in ESBL-prevalent regions |

| Carbapenems | Broad-spectrum

β-lactams | Active vs. ESBL

strains | Resistance

spreading | Standard therapy;

limited |

| Tigecycline and

Colistin | Ribosomal

inhibition/membrane disruption | Salvage for

MDR | Poor penetration,

toxicity | Last-line

therapy |

| Fosfomycin | Cell wall

inhibition (MurA) | Active vs. some

MDR | fosA resistance is

common | Off-label use |

| Novel

β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors (such as ceftazidime-avibactam,

meropenem-vaborbactam and imipenem-relebactam) | Inhibit

β-lactamases | Effective vs.

KPC/OXA-48 | Limited vs.

NDM | Approved for

systemic infections; limited clinical data in PLA |

| Cefiderocol

(siderophore cephalosporin) | Exploits iron

uptake pathways | Potent vs.

MDR/CRKP | Resistance may

develop; limited liver data | Approved; clinical

use expanding |

| Eravacycline and

Plazomicin | Ribosomal

inhibition (tet)/next-generation aminoglycoside | Activity vs. MDR

strains | Limited

PLA-specific data | Approved, limited

use |

| Anti-virulence

agents | Block capsule or

siderophores | Low resistance

pressure | Preclinical

stage | Experimental |

| Vaccines (K1/K2 and

siderophore-based) | Prevent

capsule/siderophore infection | Prophylaxis

potential | Serotype

diversity | Preclinical/early

clinical |

| Monoclonal

antibodies | Neutralize capsule,

LPS and siderophores | Adjunctive

therapy | Expensive; narrow

targets |

Preclinical/early |

| Bacteriophage/phage

enzymes | Lytic activity vs.

MDR hvKp | Active vs.

CR-hvKp | Specificity,

regulatory hurdles | Case reports,

trials emerging |

| Microbiome

interventions (probiotics and FMT) | Restore gut

balance, reduce hvKp colonization | Prevent

recurrence | Experimental; early

preclinical data only | Preclinical |

Future perspectives and clinical

challenges

K. pneumoniae PLA remains a major clinical

challenge despite recent developments in diagnostic modalities and

treatment options (14). The

emerging epidemiology of this infection is characterised by the

convergence of hypervirulence and antimicrobial resistance, which

complicates both treatment and prevention measures. In the future,

breakthroughs in therapeutics, combined with enhanced clinical and

public health approaches, will be key to alleviating the disease

burden and improving outcomes (103).

Convergence of hypervirulence and

resistance

During recent years, some of the most concerning

findings have involved the emergence of hypervirulent phenotypes

that are also multidrug resistant (112). These strains challenge the

classic divide between more resistant but less virulent ‘classic’

isolates and more overtly virulent, although

antibiotic-susceptible, ‘hypervirulent’ strains. These strains can

be considered ‘superbug’ strains as they combine the invasiveness

of hvKp with the drug resistance of cKp, eliminating the

therapeutic advantage previously afforded by antibiotic

susceptibility. Future genomic surveillance and rapid diagnostics

will be necessary to ensure these strains are rapidly identified

and contained. The clinical manifestation of this convergence is

dire; infections due to these pathogens are associated with high

morbidity and mortality and are not amenable to treatment with

available antibiotics. Future research will focus on understanding

the genetic basis of this convergence and the ecological pressures

that drive it, as this may inform surveillance, containment and

drug development efforts.

Diagnostic and predictive

limitations

Diagnosis is one of the major limiting factors for

clinical management, which is crucial for timely and accurate

treatment (98). Culture-based

methods, which are standard for testing for antimicrobial

resistance, are slow, ultimately creating a vicious circle that

delays the start of targeted therapy (113). Molecular diagnostics and rapid

resistance detection platforms are not yet readily available in

numerous clinical settings. In addition, the severity of disease

and the risk of metastatic complications cannot be accurately

predicted since clinical features and routine laboratory parameters

lack specificity. Newer discoveries of biomarkers, genomic

profiling and machine learning-based prediction approaches should

enable the early identification of high-risk patients and

facilitate personalized therapeutic solutions. Recent advances in

metagenomic sequencing and rapid MALDI-TOF-based assays have the

potential to improve early pathogen identification; however, their

widespread implementation remains limited (114).

Recent diagnostic innovations hold considerable

promise for improving the management of hvKp-PLA (114). Metagenomic next-generation

sequencing of blood or pus can identify pathogens and resistance

determinants directly from clinical specimens without the need for

culture (115). However, its

routine use remains constrained by high cost, turnaround time and

bioinformatic complexity. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry enables

species-level identification within hours from cultured isolates

and, in some centres, can be adapted for direct specimen testing

through rapid extraction workflows (114). In parallel, rapid PCR-based and

isothermal point-of-care assays targeting species markers,

virulence loci such as iuc and rmpA as well as common carbapenemase

genes, including blaNDM and blaKPC, provide

actionable results within a few hours (116). Although each of these modalities

has inherent trade-offs in sensitivity, cost and accessibility, an

integrated diagnostic approach, combining rapid molecular detection

for early guidance with culture and susceptibility testing for

definitive management, offers the greatest potential to reduce time

to effective therapy in real-world clinical settings. Successful

implementation will ultimately depend on local laboratory

infrastructure, cost-benefit considerations and integration with

antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Gaps in therapeutic options

The management options for K. pneumoniae PLA

are limited by poor penetration of drugs into abscess cavities, the

rapid emergence of resistance and a lack of targeted regimens for

hvKp (33). Antibiotics may not

reach adequate levels in the centre of abscesses as they are poorly

vascularized (69). Novel delivery

methods, such as drug-eluting beads or local catheter infusions,

may enhance intra-abscess drug concentrations and warrant further

investigation (117).

Additionally, there have been no clinical trials specifically for

hvKp-PLA, leaving no consensus on optimal empirical therapy. More

extensive registries and prospective studies are necessary to

determine the optimal antibiotic regimens and durations for

different resistance phenotypes.

Global and regional disparities

The regional distribution of K. pneumoniae

PLA is not homogenous (118).

These hypervirulent strains are most prevalent in East and

Southeast Asia, where the majority of the literature and expertise

reside (98). By contrast, MDR

strains have a longer epidemiological history in North America and

Europe, and hvKp-PLA clusters have only recently been described on

these continents. This has implications for both research

priorities and clinical approaches. For example, in Asia,

priorities may centre on vaccines and anti-virulence strategies to

curb hvKp and CRKP, whereas in Western countries, emphasis may lie

on antibiotic stewardship and infection control. This step requires

sharing surveillance data and best practices between countries.

Toward integrated and preventive

approaches

Integrated methods that apply existing and

potential novel strategies may represent a promising future for PLA

management (14). This encompasses

high-risk population prophylaxis (such as diabetes control and

potential vaccine usage), rapid diagnostic testing to target

therapy, judicious antimicrobial stewardship to limit resistance

selection and the deployment of novel therapeutic modalities. If

implemented, preventive measures, especially vaccines for the most

common capsule types or siderophores, could substantially reduce

incidence. Improved global surveillance systems and stronger health

infrastructure are crucial for detecting outbreaks and implementing

infection control measures promptly (50). A successful response to K.

pneumoniae PLA will eventually be coordinated across all

sectors of clinical medicine, microbiology and public health.

Conclusions

K. pneumoniae PLA has emerged as a

significant clinical and public health concern, driven by the dual

threats of hypervirulence and escalating antimicrobial resistance.

While advances in imaging, interventional drainage and antibiotic

therapy have improved outcomes, the increasing prevalence of

strains combining MDR with invasive virulence presents an urgent

global challenge. Therapeutic options are limited by poor

pharmacokinetics, inconsistent efficacy and the absence of

standardized regimens for resistant or hypervirulent infections.

The future of management will depend on a multipronged strategy.

Continued surveillance is necessary to track the evolving

epidemiology and the genetic determinants of virulence and

resistance. Innovative therapeutics, including novel antibiotics,

anti-virulence agents, immunotherapies and bacteriophage-based

approaches, offer promise for more effective, targeted

interventions. At the same time, advances in diagnostics and

predictive modelling may enable earlier recognition of high-risk

patients and more personalized care. Preventive strategies,

especially vaccines, together with global antimicrobial stewardship

and strengthened health systems, will be central to reducing

disease burden. Ultimately, addressing K. pneumoniae liver

abscess requires an integrated vision that bridges clinical

medicine, microbiology and public health. Only coordinated global

action and sustained translational research can counter this

formidable pathogen and its increasingly complex clinical

manifestations.

Acknowledgements

GMH would like to thank the Prince Sattam Bin

Abdulaziz University (Grant No. PSAU/2025/RV/7).

Funding

This work is sponsored by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University

(grant no. PSAU/2025/RV/7).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contribution

GMH contributed to conceptualization, funding

acquisition, and preparation of the original draft. TM contributed

to data analysis, graphics preparation, data validation and

critical revision of the manuscript. SZ contributed, graphics

design, data validation and manuscript review. AS contributed to

analysis, graphics, data curation (systematically collecting,

organizing, and verifying the literature, clinical reports, and

epidemiological datasets relevant to Klebsiella

pneumoniae–associated pyogenic liver abscess - this included

screening articles, extracting key findings, maintaining reference

databases, and ensuring accuracy and consistency of the compiled

information used for analysis), critical revisions and supervision.

SSS contributed to graphics, data validation, manuscript review and

supervision. MIH guided the conceptual framework, supervised the

study, critical revisions and managed project administration. SZ

and MIH contributed to the investigation, this involved conducting

an in-depth scientific inquiry into the clinical features,

virulence mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies associated with

Klebsiella pneumoniae infections - this covered critical

literature analysis, interpretation of current evidence,

identifying research gaps, and synthesizing mechanistic insights

necessary for the development of the review article. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools (ChatGPT) were used to improve the readability

and language of the manuscript or to generate images, and

subsequently, the authors revised and edited the content produced

by the artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Priyanka A, Akshatha K, Deekshit VK,

Prarthana J and Akhila DS: Klebsiella pneumoniae infections

and antimicrobial drug resistance. Model organisms for microbial

pathogenesis, biofilm formation and antimicrobial drug discovery.

Springer. (Singapore). 195–225. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Giacobbe DR, Di Pilato V, Karaiskos I,

Giani T, Marchese A, Rossolini GM and Bassetti M: Treatment and

diagnosis of severe KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

infections: A perspective on what has changed over last decades.

Ann Med. 55:101–113. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang S, Zhang X, Wu Q, Zheng X, Dong G,

Fang R, Zhang Y, Cao J and Zhou T: Clinical, microbiological, and

molecular epidemiological characteristics of Klebsiella

pneumoniae-induced pyogenic liver abscess in southeastern

China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 8:1662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Al Ismail D, Campos-Madueno EI, Donà V and

Endimiani A: Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKp):

Overview, epidemiology, and laboratory detection. Pathog Immun.

10:80–119. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Marr CM and Russo TA: Hypervirulent

Klebsiella pneumoniae: A new public health threat. Expert

Rev Anti Infect Ther. 17:71–73. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Choby JE, Howard-Anderson J and Weiss DS:

Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae-clinical and molecular

perspectives. J Intern Med. 287:283–300. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sohrabi M, Alizade Naini M, Rasekhi A,

Oloomi M, Moradhaseli F, Ayoub A, Bazargani A, Hashemizadeh Z,

Shahcheraghi F and Badmasti F: Emergence of K1 ST23 and K2 ST65

hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae as true pathogens with

specific virulence genes in cryptogenic pyogenic liver abscesses

Shiraz Iran. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 12:9642902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Berman JJ: Changing how we think about

infectious diseases. Taxonomic guide to infectious diseases.

(second edition). Elsevier; pp. 321–365. 2019, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liao CH, Huang YT, Chang CY, Hsu HS and

Hsueh PR: Capsular serotypes and multilocus sequence types of

bacteremic Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates associated with

different types of infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.

33:365–369. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mendes G, Santos ML, Ramalho JF, Duarte A

and Caneiras C: Virulence factors in carbapenem-resistant

hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Microbiol.

14:13250772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Thirugnanasambantham MK, Thuthikkadu

Indhuprakash S and Thirumalai D: Phenotypic and genotypic

characteristics of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae

(hvKp): A narrative review. Curr Microbiol. 82:3412025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ding L, Shen S, Chen J, Tian Z, Shi Q, Han

R, Guo Y and Hu F: Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase

variants: The new threat to global public health. Clin Microbiol

Rev. 36:e00008232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Khan AU, Maryam L and Zarrilli R:

Structure, genetics and worldwide spread of New Delhi

metallo-β-lactamase (NDM): A threat to public health. BMC

Microbiol. 17:1012017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shah AA, Alwashmi AS, Abalkhail A and

Alkahtani AM: Emerging challenges in Klebsiella pneumoniae:

Antimicrobial resistance and novel approach. Microb. Pathog.

202:1073992025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hetta HF, Alanazi FE, Ali MAS, Alatawi AD,

Aljohani HM, Ahmed R, Alansari NA, Alkhathami FM, Albogmi A,

Alharbi BM, et al: Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae:

Insights into virulence, antibiotic resistance, and fight

strategies against a superbug. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 18:7242025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pan Y, Chen H, Ma R, Wu Y, Lun H, Wang A,

He K, Yu J and He P: A novel depolymerase specifically degrades the

K62-type capsular polysaccharide of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

One Health Adv. 2:52024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xu Q, Liu C, Wu Z, Zhang S, Chen Z, Shi Y

and Gu S: Demographics and prognosis of patients with pyogenic

liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumonia or other species.

Heliyon. 10:e294632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pandita A, Javaid W and Fazili T: Liver

Abscess. In: Introduction to Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Domachowske J: Springer; Cham: pp. 147–155. 2019

|

|

19

|

Lam JC and Stokes W: Management of

pyogenic liver abscesses: Contemporary strategies and challenges. J

Clin Gastroenterol. 57:774–781. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|