Introduction

Small cell cervical carcinoma (SCCC) is a

neuroendocrine tumor with great aggravation. It accounts for only

0.5–3% (1) of cases of cervical

cancer and progresses rapidly with early lymphogenous and

hemotagenous metastases. The incidence of cervical cancer during

pregnancy is ~1/2,000 individuals. Patients with SCCC are more

likely to exhibit lymph node metastases and lymph vascular space

invasion. Although chemoradiation has been shown to improve

survival in non-small cell carcinoma of cervix, the optimal initial

therapeutic approach has not been identified in SCCC (2). Standard chemotherapy regimens, such as

cisplatin and etoposide, are administered according to the

management of small cell lung cancer. The five-year survival rate

for SCCC ranges between 0 and 30% (3). The present report describes a case of

SCCC in an 18-year-old female, which occurred during pregnancy, and

was treated with cisplatin and etoposide chemotherapy and then

radiotherapy. Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient.

Case report

An 18-year-old Chinese female presented to the

Comphrensive Cancer Center of Drum Tower Hospital (Nanjing, China)

with intermittent vaginal bleeding of ~50ml/day, for 47 days

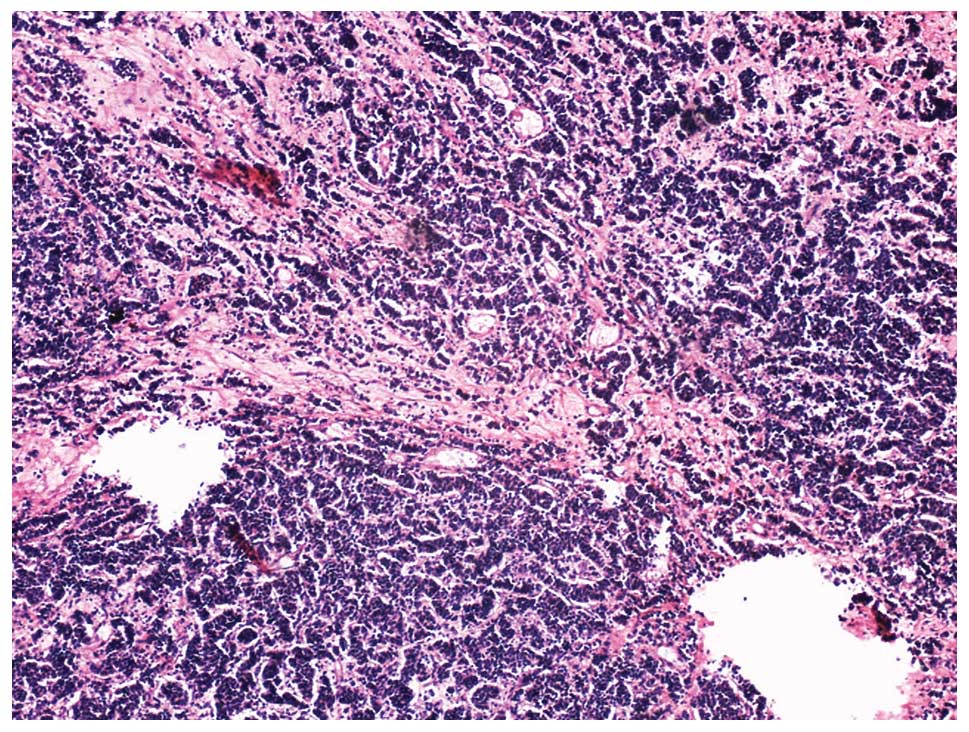

following delivery. On June 3, 2013, a 6.0×6.0-cm exophytic friable

mass was identified in the uterine cervix by colposcopic

examination. On histological examination, the mass was diagnosed as

SCCC (Fig 1). Immunohistochemistry

revealed positive staining for chromogranin A (CgA), cytokeratin,

cluster of differentiation (CD)56, synapsin (Syn), Ki67 (50%+) and

human papillomavirus (HPV). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

confirmed a 5.8×5.7-cm cervical carcinoma and swelling of the lymph

nodes in the pelvis (Fig. 2). Based

on the histological and radiographical observations (Fig. 1), the tumor was diagnosed as SCCC,

and classified as International Federation of Gynecology and

Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB2 (4).

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) was administered, which consisted

of four cycles of treatment with intravenous (i.v) cisplatin (70

mg/m2, days 1–3) and i.v etoposide (70 mg/m2,

days 1–5) for ~9 weeks. Atypical vaginal spotting disappeared

following the first cycle of therapy. After the fourth cycle of

NACT, MRI revealed a 90% decrease in tumor size when compared with

previous MRI scans of the cervical mass and an 80% decrease in size

of the lymph nodes (Fig. 2). Three

weeks after completing NACT, the patient received 3D

intensity-modulated radiation therapy with a total dose of 44 Gy

administered to the pelvis and 54 Gy to the pelvic lymph nodes.

Image-guided high-dose-rate intracavity brachytherapy at a dose of

25 Gy in combination with low dose Nedaplat (40 mg/m2)

was administered for eight weeks. MRI showed complete remission had

been achieved following radiotherapy. On February 20, 2014, the

patient was disease-free without signs of recurrence.

Discussion

The typical clinical manifestations of SCCC include

irregular vaginal bleeding, exudation discharge and severe pain at

advanced stages. The diagnosis of SCCC was aided by

immunohistochemical staining for common neuroendocrine markers,

including Syn, CgA, neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and CD56.

Typically, SCCC samples exhibit 100, 96.0, 68.0, 76.0, 40.0, 84.0,

68.0 and 8.0% positivity for NSE, Syn, CD56, CgA, thyroid

transcription factor-1, epithelial membrane antigen, cytokeratin

and S100 immunohistochemical biomarkers, respectively (5).

At the time of diagnosis, 60.0–82.0% of SCCCs

exhibit lymph-vascular space infiltration or pelvic lymph node

metastasis (1). SCCC may also

rapidly metastasize to the lungs, liver, brain, bones and pancreas.

In a previous study, the rate of lymph node metastases in FIGO

stage IB1 SCCC was 20%, and in stages more advanced than IB1, the

rate was >50% (6). In patients

who had relapsed following complete treatment, 67% exhibited

hematogenous metastases and 34% exhibited lymphogenous metastases,

which indicated a higher probability of hematogenous metastases

following first-line treatment. The overall five-year survival

rates of 58 patients with SCCC were determined to be ~55–85% for

stages IA2–IB1, 25–30% for stage IB2–II and 0–16% for stage III–IV

(6). Liao et al (1) and Cohen et al (7) have reported that the prognosis of SCCC

is associated with FIGO stage, tumor size, CgA levels, lymph node

metastasis, depth of infiltration and treatment. Patients with FIGO

stage I–IIA tumors, tumor size ≤4 cm, negative CgA status, no lymph

node metastasis and infiltrating depth of <1/3, exhibited a

better prognosis. No significant differences in patient prognosis

were observed with regard to NSE, Syn and lymphovascular space

invasion. Cohen et al (7)

found that in a multi-center study of 188 patients, the five-year

survival rate for stage I–IIA patients who received a radical

hysterectomy was 38.2%, when compared with those who did not

undergo surgery was 23.8% (P<0.05). The correlation between HPV

infection and the prognosis of SCCC is extremely controversial. One

study reported that ~76.2% (64/84) patients were HPV positive

(8). HPV infection was associated

with better disease-free survival, overall survival (OS) and local

control. Vosmik et al (9)

also demonstrated that patients with HPV positivity and high

epidermal growth factor receptor expression had a high probability

of achieving complete response (P=0.038 and P=0.044,

respectively).

Sood et al (10) compared 27 postpartum women, who were

diagnosed within six months of giving birth, with 56 women

diagnosed during pregnancy. A total of 48–49% of cervical cancers

associated with pregnancy were found to be diagnosed within six

months of delivery. Of the cervical cancers diagnosed during

pregnancy, 89.3% cancers were stage I SCCC, 8.9% were stage II,

1.7% were stage ≥III, whereas the rates were 70.4%, 26.0%, and 3.7%

in the women diagnosed after giving birth. Therefore, a higher

proportion of early-stage tumors were diagnosed in the pregnant

patients (11). Similar to the

population of women who are not pregnant, the majority of cases of

invasive cervical cancer were squamous cell carcinoma (>80%). Of

the remaining cases, the majority were adenocarcinomas, and SCCC

was relatively rare.

To date, five cases of pregnant females with SCCC

treated with NACT, followed by radical hysterectomy, have been

reported. Gestation accelerates the progression of cervical

carcinoma due to immunological suppression, high levels of estrogen

and an abundant cervical blood supply during pregnancy. In a study

by Abeler et al (12), 40%

patients were HPV-16-positive while 28% were HPV-18-positive

(12). All cases of SCCC in

pregnant females are shown in Table

I. Pregnancy may augment the development of infections, in

particular HPV infections. The five-year survival rate of cervical

cancer during pregnancy is worse than cervical cancer alone, with

rates of 70–78 and 87–92%, respectively.

| Table ICell carcinoma of the cervix during

pregnancy: literature review (19–29). |

Table I

Cell carcinoma of the cervix during

pregnancy: literature review (19–29).

| Author (Ref) | Age (years) | FIGO stage | GA at diagnosis

(weeks) | NACT. intervals | Treatment | Follow up

(months) | Outcome mother | Child |

|---|

| Chun KC et al

(15) | 27 | IB1 | 25 | 3*CDDP 175

mg/m2 paclitaxel 75 mg/m2 |

C/S+RH+PLND+PALND | 46 | DOD | Normal |

| Smyth EC et al

(16) | 26 | IIA | 23 | 3*ADM 60

mg/m2 CTX 600 mg/m2 |

C/S+4*etoposide+pelvic

radiation | | NED | Normal |

| Ohwada M et al

(17) | 27 | IB1 | 27 | None |

C/S+RH+PLND+4*etoposide | 13 | NED | Normal |

| Leung TW et al

(18) | 26 | IB2 | 31 | None | C/S+CCRT (cisplatin

100 mg/m2+EP) | 14 | NED | Normal |

| Balderston KD et

al (19) | 22 | IIA | 30 | 3*CDDP 80

mg/m2 etoposide 400 mg/m2 2*VCR

1.2 mg/m2 dactinomycin 300 mg/m2 CTX 150

mg/m2 | Pelvic

radiotherapy+4*EP | 66 | NED | Normal |

| Perrin L et al

(20) | 23 | IIA | 25 | None | C/S; RH,+PLND+adj.

chemotherapy (DDP, paclitaxel, etoposide) | | DOD | Normal |

| Chang et al

(21) | 27 | IB | 36 | None | C/S; RH+

PLND+radiotherapy | | DOD | Normal |

| Lojek et al

(22) | 28 | IIA | 25 | None | C/S; PLND;

radiotherapy, adj. chemotherapy | | | |

| Turner WA et

al (23) | 26 | IB | 26 | None | C/S; RH+PLND, adj.

chemotherapy | 9 | DOD | Normal |

| Jacobs et al

(24) | 25 | IB | 10 | DDP 50 mg/Kg | RH+PLND,

radiotherapy | 24 | DOD | Normal |

| Kodousek R et

al (25) | 29 | IB | 28 | None | C/S; RH+PLND, adj.

chemotherapy | 6 | DOD | Normal |

Small cell carcinoma is hypothesized to be sensitive

to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In the present study, first line

systemic chemotherapy to eradicate the potential micrometastases

was recommended due to the high probability of metastasis at early

stages and the poor prognosis compared with other pathological

types of cancer. Platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with

pelvic and para-aortic nodal irradiation was administered. A

multicenter, collaborative study reported that postoperative

chemotherapy improved OS and progression-free survival (PFS) when

compared with non-chemotherapy (6).

The four-year PFS rate was 65% in the group that received

postoperative chemotherapy and 14% without postoperative

chemotherapy, and the four-year OS rates were 65 and 29%,

respectively. Early stage patients who received post-chemotherapy

with the etoposide regimen (cisplatin + etoposide), with or without

radiation, exhibited an 83% three-year relapse-free survival,

compared with 0% for those who did not receive adjuvant

chemotherapy (13), indicating the

importance of chemotherapy. No standard treatment regimens have

been identified due to the low incidence of SCCC during pregnancy

(2). As a result, standard regimens

are selected according to the management of small cell lung cancer

(3). The method for the treatment

of SCCC includes radical surgery (RS) and/or radiotherapy, NACT

combined with RS and/or radiotherapy or CCRT (2). Surgery is the first choice at early

stages while system chemotherapy is critical at late stages.

Katsumata et al (14)

reported that NACT with BOMP (bleomycin, vincristine, mitomycin,

and cisplatin) prior to RS did not improve the OS of patients with

stage IB2, IIA and IIB cervical cancer. However, NACT reduced the

proportion of patients who received postoperative RT. In a previous

study, 10 patients were treated with a regimen of cisplatin,

doxorubicin and etoposide followed by radical hysterectomy, pelvic

lymphadenectomy and/or radical radiotherapy. The median duration of

survival was 28 months (26). In

another study, 14 patients with stage IA or IB SCCC received

radical hysterectomy alone or in combination with pelvic

radiotherapy. A total of 12/14 patients succumbed to the disease

within 31 months and the other two patients exhibited recurrence at

38 and 44 months (27). Although

the sample sizes were small in these studies, the results indicated

that chemotherapy followed by surgery may improve the outcome of

patients. However, chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy is

controversial (28–30), as a number of phase III clinical

trials have demonstrated that chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy

does not exhibit any significant survival benefit, however, a

different toxicity profile appeared: alopecia (87.9% vs. 4.1%;

P<0.001) and neurotoxicity (65.9% vs. 15.6%; P<0.001) were

significantly higher in the patients with paclitaxel plus

carboplatin followed by radiation. In the present study, the

patient was diagnosed with stage IB2 SCCC, with an extensive mass

in the cervix and lymph node metastasis in the pelvis. RS was not

suitable and the patient underwent four cycles of NACT with

cisplatin and etoposide. MRI of the pelvis showed complete

remission of the mass in the cervix and lymph nodes. The patient

subsequently received radical radiotherapy, due to being unsuitable

for RS. A total of four additional cycles of cisplatin and

etoposide were administered from February 2014, when the patient

exhibited no evidence of relapse.

SCCC in pregnancy must be diagnosed as early as

possible. Cytological screening, colposcopy and if required,

biopsy, and selective conization at 14–20 weeks gestation should be

considered in the patient evaluation (31). The stage of disease, gestational age

at diagnosis and patient’s preference must be considered for

individualized treatment.

In conclusion, the present study reported a case of

SCCC, which occurred during pregnancy. Treatment with NACT and

radiotherapy resulted in complete clinical remission. Future

clinical trials with a large cohorts are required to determine

whether aggressive initial combined therapy, in particular NACT

with radiotherapy, may improve the prognosis of advanced SCCC

patients.

References

|

1

|

Liao LM, Zhang X, Ren YF, et al:

Chromogranin A (CgA) as poor prognostic factor in patients with

small cell carcinoma of the cervix: results of a retrospective

study of 293 patients. PLoS One. 7:e336742012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Delaloge S, Pautier P, Kerbrat P, et al:

Neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: what

disease? What treatment? Report of ten cases and a review of the

literature. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 12:357–362. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zivanovic O, Leitao MM Jr, Park KJ, et al:

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Analysis of

outcome, recurrence pattern and the impact of platinum-based

combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 112:590–593. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.

FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and corpus uteri.

Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 125:97–98. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li JD, Zhuang Y, Li YF, et al: A

clinicopathological aspect of primary small-cell carcinoma of the

uterine cervix: a single-centre study of 25 cases. Clin Pathol.

64:1102–1107. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kuji S, Hirashima Y, Nakayama H, et al:

Diagnosis, clinicopathologic features, treatment, and prognosis of

small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: Kansai Clinical

Oncology Group/Intergroup study in Japan. Gynecol Oncol.

129:522–527. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cohen JG, Kapp DS, Shin JY, et al: Small

cell carcinoma of the cervix: treatment and survival outcomes of

188 patients. Obstet Am J Obstet Gynecol. 203:347.e1–e6. 2010.

|

|

8

|

Lindel K, Burri P, Studer HU, et al: Human

papillomavirus status in advanced cervical cancer: predictive and

prognostic significance for curative radiation treatment. Int J

Gynecol Cancer. 15:278–284. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vosmik M, Laco J, Sirak I, et al:

Prognostic Significance of human papillomavirus (HPV) status and

expression of selected markers (HER2/neu, EGFR, VEGF, CD34, p63,

p53 and Ki67/MIB-1) on outcome after (chemo-) radiotherapy in

patients with squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix. Pathol

Oncol Res. 20:131–137. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Mayr N, et al:

Cervical cancer diagnosed shortly after pregnancy: prognostic

variables and Lishner M: Cancer in pregnancy. Annals of Oncology.

14:31–36. 2003.

|

|

11

|

Lishner M: Cancer in pregnancy. Ann Oncol.

14(Suppl 3): iii31–iii36. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Abeler VM, Holm R, Nesland JM and Kjørstad

KE: Small cell carcinoma of the cervix. A clinicopathologic study

of 26 patients. Cancer. 73:672–677. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zivanovic O, Leitao MM Jr, Park KJ, et al:

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Analysis of

outcome, recurrence pattern and the impact of platinum-based

combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 112:590–593. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Katsumata N, Yoshikawa H, Kobayashi H, et

al: Phase III randomised controlled trial of neoadjuvant

chemotherapy plus radical surgery vs radical surgery alone for

stages IB2, IIA2, and IIB cervical cancer: a Japan Clinical

Oncology Group trial (JCOG 0102). Br J Cancer. 108:1957–1963. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chun KC, Kim DY, Kim JH, et al:

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum followed by

radical surgery in early cervical cancer during pregnancy: three

case reports. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 40:694–698. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Smyth EC, Korpanty G, McCaffrey JA, et al:

Small-cell carcinoma of the cervix at 23 weeks gestation. J Clin

Oncol. 28:e295–e297. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ohwada M, Suzuki M, Hironaka M, et al:

Neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix showing

polypoid growth and complicated by pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol.

81:117–119. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Leung TW, Lo SH, Wong SF, et al: Small

cell carcinoma of the cervix complicated by pregnancy. Clin Oncol

(R Coll Radiol). 11:123–125. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Balderston KD, Tewari K, Gregory WT, et

al: Neuroendocrine small cell uterine cervix cancer in pregnancy:

long-term survival following combined therapy. Gynecol Oncol.

71:128–132. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Perrin L, Bell J and Ward B: Small cell

carcinoma of the cervix of neuroendocrine rigin causing obstructed

labor. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 36:85–87. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chang DH-C, Hsueh S and Soong YK: Small

cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix with neurosecretory granules

associated with pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 39:537–540.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lojek MA, Fer MF, Kasselberg AG, et al:

Cushing’s syndrome with small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix.

Am J Med. 69:140–144. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Turner WA, Gallup DG, Talledo OE, et al:

Nueroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix complicated by

pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Obstet

Gynecol. 67(3 Suppl): 80S–83S. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jacobs AJ, Marchevsky A, Gordon RE, et al:

Oat cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix in a pregnant woman

treated with cisdiamminedichloroplatinum: case report. Gynecol

Oncol. 9:405–410. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kodousek R, Gazarek F, Dusek J and Dostál

S: Malignant apudoma (argyrophil cell cancer) of the uterine cervix

in a 24-year-old woman in pregnancy. Cesk Pathol. 12:37–44.

1976.(In Czech).

|

|

26

|

Morris M, Gershenson DM, Eifel P, et al:

Treatment of small cellcarcinoma of the cervix with cisplatin.

doxorubicin and etoposide. Gynecol Oncol. 47:62–65. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sheets EE, Berman ML, Hrountas CK, et al:

Surgically treated, early stage small cell cervical carcinoma.

Obstet Gynecol. 71:10–14. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sehouli J, Runnebaum IB, Fotopoulou C, et

al: A randomized phase III adjuvant study in high-risk cervical

cancer: simultaneous radiochemotherapy with cisplatin (S-RC) versus

systemic paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by percutaneous

radiation (PC-R): a NOGGO-AGO Intergroup Study. Ann Oncol.

23:2259–2264. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Herod J, Burton A, Buxton J, et al: A

randomised, prospective, phase III clinical trial of primary

bleomycin, ifosfamide and cisplatin (BIP) chemotherapy followed by

radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in inoperable cancer of the

cervix. Ann Oncol. 11:1175–1181. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Symonds RP, Habeshaw T, Reed NS, et al:

The Scottish and Manchester randomised trial of neo-adjuvant

chemotherapy for advanced cervical cancer. Eur J Cancer.

36:994–1001. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nguyen C, Montz FJ and Bristow RE:

Management of stage I cervical cancer in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol

Surv. 55:633–643. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|