Introduction

Granulocytic sarcoma (GS) is a rare, extramedullary

malignant neoplasm consisting of myeloid cells with different

levels of maturation and occurring in anatomic sites other than the

bone marrow or peripheral blood (1).

It represents a distinct entity of AML (2).

The high expression of myeloperoxidase (MPO) makes

these tumors green, hence their alternative name, ‘chloroma’ (from

the Greek word ‘chloros’, meaning green). However, ‘sarcoma’ is the

most commonly used term, as ~30% of these tumors do not contain

MPO, despite the fact that MPO together with cluster of

differentiation (CD)117 represents the marker for myeloid

differentiation (1).

GS may develop de novo (solitary, primary or

non-leukemic GS; 8–20%) (3),

simultaneously to AML (2.5–9.1%) (4),

or as a relapse of leukemia, particularly following allogeneic

hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHSCT) (4,5). The

reason for this association is still unknown, but may be attributed

to a pattern of graft-versus-leukemia surveillance or to the

biology of high-risk AML treated with transplantation (5).

GS may affect patients of all ages (median age, 56

years; range, 1 month to 89 years), with a male:female ratio 1.2:1

(6). Commonly involved sites include

subperiosteal bone, lymph nodes and skin. The prevalence of head

and neck region involvement is 12–43% of cases (5), and orbit, skull and epidural spaces are

the most frequently involved sites (7). Rare lesions have been described in the

maxilla, soft palate, paranasal sinus, salivary gland, scalp and

temporal bone, whereas only a few cases have been described with

rhinopharyngeal involvement (4).

GS risk factors include specific chromosomal

abnormalities [t(8;21) and inv(16)],

expression of cell-surface markers (CD56, CD2, CD4 and CD7), and

M2, M4 and M5 leukemia subtypes of the French-American-British

classification (4). Additional risk

factors include poor nutritional status, cellular immune

dysfunction, high presenting leukocyte count and decreased blast

Auer rods (4).

Sinonasal congestion and/or hearing loss are the

most common clinical manifestations of rhinopharyngeal GS (4).

The diagnosis of the rhinopharyngeal GS,

particularly when it is poorly differentiated or without

concomitant marrow involvement, is challenging (8), and it is not uncommon for GS to be

misdiagnosed as lymphoma (8,9). To improve the accuracy of diagnosis,

immunohistochemical patterns play a key role. For instance, myeloid

cells are reactive to antibodies against lysozyme, MPO and

chloroacetate esterase. Furthermore, GS myeloblasts typically

express myeloid-associated antigens, such as CD43, but are not

reactive to lymphoid antigens. In addition, flow cytometry and

cytogenetic analysis may aid in determining a definitive diagnosis

(8).

GS is sensitive to focal irradiation and to systemic

chemotherapy, similarly to AML (7,10,11). Systemic treatment should always be

considered due to the high rate of recurrence and progression to

AML (11). Surgery may be a

therapeutic option only for tumors, which cause organ dysfunction

(11). The role of radiotherapy and

AHSCT as a consolidation regimen remains to be clearly established

(10,11).

GS has an unfavorable prognosis. Its course is rapid

with a high mortality rate, particularly when associated with AML,

whereas patients without evidence of leukemia have a better

prognosis (9); cases initially

diagnosed as solitary GS without evidence of leukemia and treated

with systemic chemotherapy have a more favorable prognosis

(9).

The current study reports the case of a 53-year-old

woman who presented with a rhinopharyngeal mass. The mass was

diagnosed as an isolated extramedullary GS as a relapse of AML,

which had been treated 7 years earlier with chemotherapy and AHSCT

and was followed by complete remission. In addition, a review of

the literature is reported, along with the examination of

immunohistochemical features as a tool for the differential

diagnosis of GS compared to other rare tumors of the

rhinopharynx.

Case report

A 53-year-old female non-smoker presented to the

Ear, Nose and Throat Unit of ‘Federico II’ University of Naples

(Naples, Italy) complaining of left otalgy, hearing loss and nasal

obstruction for ~5 months. The patient had a history of AML, which

was in complete remission following high-dose chemotherapy and

AHSCT, administered 7 years earlier.

A nasal endoscopy revealed a left rhinopharyngeal

peritubaric mass obstructing the left Eustachian tube. The

audiological evaluation revealed left conductive hearing loss due

to an ipsilateral middle ear effusion. No lateral cervical palpable

lymph nodes were found. Magnetic resonance imaging and positron

emission tomography-computed tomography (CT) examinations revealed

a mass of the rhinopharynx (6×3.5 cm; standardized uptake value,

5.7) without bone erosion.

Laboratory studies, including a normal complete

blood count, unremarkable serum chemistry and normal liver enzyme

levels, did not reveal any alteration. No evidence of increased

blast cell count was observed in the bone marrow aspiration

sample.

The specimen was formalin fixed and paraffin

embedded. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the avidin

biotin complex as a visualization system and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine

as chromogen for the reaction, with pre-diluted antibodies

(dilution, 1:100) against B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2; 790–4604, clone

SP66; rabbit; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA), CD3

(790–4341; clone 2GV6; rabbit; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.), CD5

(790–4451; clone SP19; rabbit; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.), CD10

(790–4506; clone SP67; rabbit; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.), CD20

(760–2531; clone L26; mouse; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.), CD34

(790–2927; clone QBEnd/10; mouse; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.),

CD43 (760–2511; clone L60; mouse; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.),

CD56 (790–4465; clone 123C3; mouse; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.),

CD99 (790–4452; clone O13; mouse; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.),

CD117 (790–2951; clone 9.7; rabbit; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.),

Ki67 (M724029; clone MIB1; mouse; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and MPO

(760–2659; rabbit polyclonal; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). The

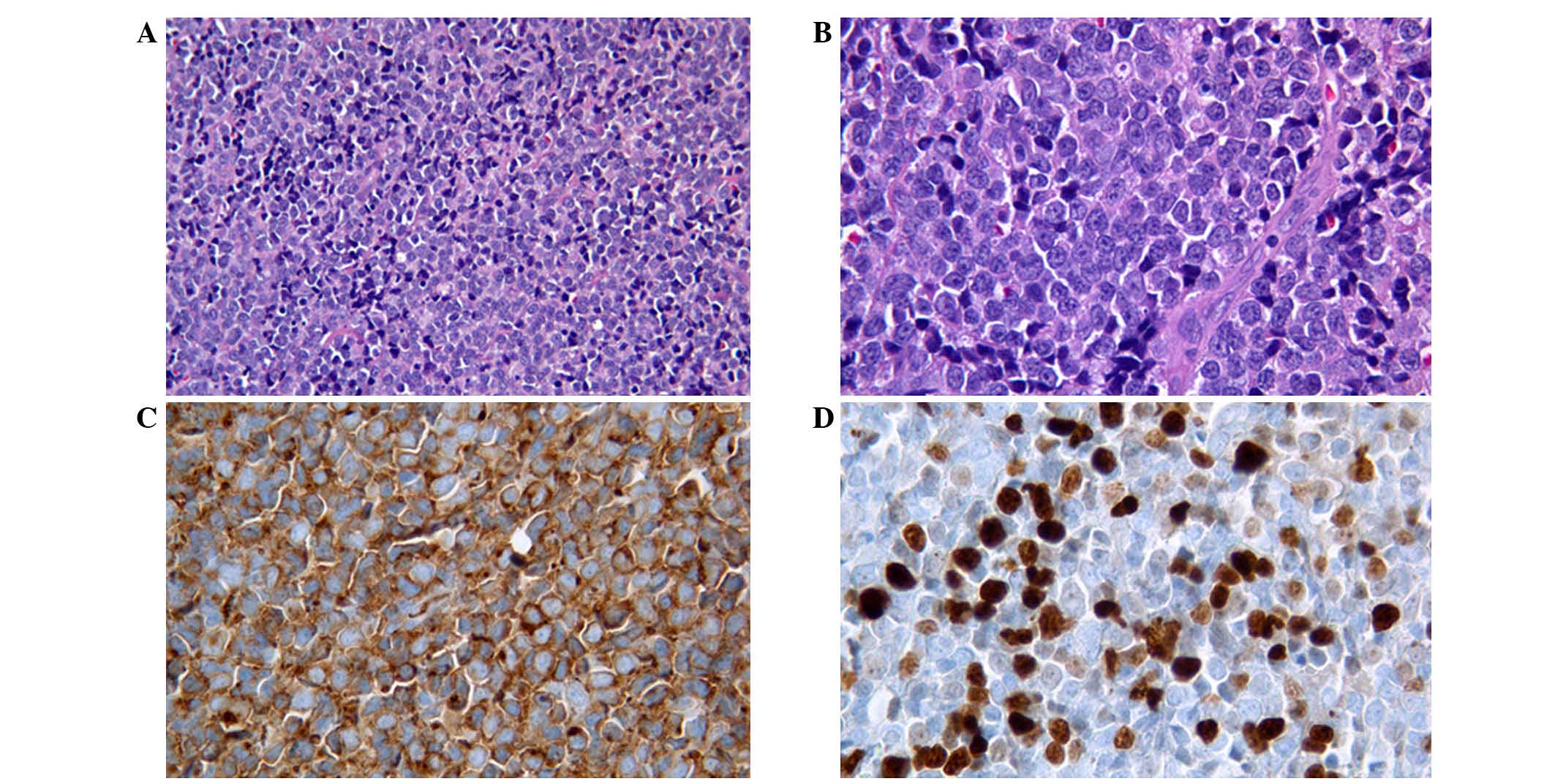

patient underwent biopsy of the rhinopharyngeal lesion, which

revealed neoplastic proliferation of medium- and small-sized cells.

These cells exhibited inconspicuous cytoplasm, nuclei with

irregular membranes, occasionally a small nucleolus, diffuse

karyorrhexis and high mitotic activity (Fig. 1).

The immunohistochemical evaluation revealed strong

reactivity for CD43, CD34 and CD99, whereas CD20, CD3, CD5, CD10,

Bcl-2, MPO, CD117 and CD56 were all negative. The Ki-67

proliferative index was ~40%. Fluorescence in situ

hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed on 4-µm-thick

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections, using the

Vysis LSI Dual Color probe (Abbott Molecular, Inc., Des Plaines,

IL, USA) specific for runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1)

labeled with Spectrum Green and for RUNX1T1 labeled with Spectrum

Orange. The slides were hybridized overnight according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Image analysis was then conducted. The

FISH analysis of FFPE tumor slides did not identify either the

t(8;21) translocation or MLL gene dissociation.

The patient's medical history and immunophenotype

suggested the presence of a poorly differentiated extramedullary GS

of the rhinopharynx as a relapse of AML, without bone marrow

disease.

The patient was treated with conventional induction

AML therapy: Combined idarubicin (12 mg/m2/day, days

1–2) and cytarabine (200 mg/m2/day, days 1–7), followed

by one course of consolidation therapy with idarubicin (12

mg/m2, day 1) and cytarabine (1 g/m2/12 h,

days 1–5), as well as radiation treatment (1,500 cGy in 5

fractions).

A CT scan performed at 1 month after

chemoradiotherapy revealed complete resolution of the

rhinopharyngeal mass. At the 3-year follow-up, the patient was

asymptomatic and without signs of recurrence. At present, the

patient is under a regular surveillance protocol; she is closely

monitored through a multidisciplinary ‘short time’ follow-up

protocol, consisting of nasal endoscopy and blood studies every 3

months.

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying

images.

Discussion

GS, also known as ‘chloroma’ or ‘extramedullary

myeloblastoma’, is a rare solid tumor consisting of primitive

precursors of the granulocytic series of white blood cells, which

include myeloblasts, promyelocytes, and myelocytes (1). Rhinopharyngeal localization of GS is

extremely rare; only a few cases have been previously reported in

the literature (4), and the present

study reports the 15th case (Table

I).

| Table I.Case reports of GS involving the

nasopharynx. |

Table I.

Case reports of GS involving the

nasopharynx.

| Author | Age,

years/gender | Site/symptoms | Associated

diagnosis | Cytogenetic

findings |

Treatment/outcome | Ref. |

|---|

| Vishnu et

al | 63/F | Conductive hearing

loss; nasopharyngeal mass | Developed AML 1 year

later | Normal | Radiation therapy

only for GS; chemotherapy for AML; CR at 18 months | (4) |

| Raphael et

al | 73/M | Left maxillary sinus,

posterior ethmoidal cells | Synchronous MDS | t(3;21) | Chemotherapy; AML

after 3 months; mortality during chemotherapy. | (10) |

| Bassichis et

al | 1/M | Masseter muscle | Synchronous AML | NR | Mortality during

chemotherapy | (16) |

| Au et al | 37/M | Conductive hearing

loss; nasopharyngeal mass | Solitary GS | Normal | IFRT+chemotherapy; CR

at 3 years | (17) |

| Nayak et

al | 24/F | Bilateral parotid and

nasopharyngeal mass | Solitary GS | NR | Mortality during

chemotherapy | (18) |

| Geisse et

al | 60/M | Waldeyer's ring

lymphadenopathy | Synchronous MDS | NR | Diagnosis made on

autopsy | (19) |

| Prades et

al | 20/F | Sinonasal

obstruction; right maxillary and sphenoid sinus mass | GS of the nasal

cavity and paranasal sinus | t(19;1) | Chemotherapy+AHSCT;

CR at 18 months | (20) |

| Ozcelik et

al | 37/M | Vocal cord paralysis;

involvement of 9th, 10th and 12th cranial nerves | AML 6 months earlier,

treated with chemotherapy to CR | NR | Mortality during

chemotherapy | (21) |

| Sugimoto et

al | 31/F | Nasopharyngeal

mass | AML 3 months earlier,

treated with chemotherapy to CR | t(8;21) | CR2 achieved with

IFRT, reinduction chemotherapy+AHSCT | (22) |

| Imamura et

al | 7/F | Waldeyer's ring

lymphadenopathy | Synchronous JMML | t(9;12) | Chemotherapy+AHSCT;

CR at 3 years | (23) |

| Ferri et

al | 72/F | Right facial swelling

and fever; maxillo-ethmoidal mass | AML 1 year earlier,

treated with hydroxyurea | NR | Best supportive care

only; mortality after 10 days of hospitalization | (24) |

| Teramoto et

al | 81/F | Nasopharyngeal

mass | Developed AML 1

year later | Complex genomic

defects on cDNA microarray | Radiation therapy

only for GS; chemotherapy for AML; mortality 6 months after

diagnosis of AML | (25) |

| Selvarajan et

al | 25/M | Dysphagia,

hoarseness, facial nerve palsy | AML 4 years

earlier, treated with chemotherapy to CR followed by AHSCT | t(8;21) | Chemotherapy;

systemic relapse 1 year later | (26) |

| Cho et

al | 18/M | Conductive hearing

loss; nasopharyngeal mass | Synchronous

AML | t(8;21) | Recurrence after 7

months of chemotherapy; CR2 achieved with reinduction

chemotherapy+AHSCT | (27) |

| Mei et

al | 56/F | Left maxillary

sinus | Solitary site of

GS | NR | Surgical resection

and chemotherapy; CR at 4 months | (28) |

| Current case | 53/F | Conductive hearing

loss; nasopharyngeal mass | AML 7 years

earlier, treated with chemotherapy to CR followed by AHSCT | Normal | Chemoradiaton

therapy; no sign of recurrence at 1 year |

GS has a high rate of misdiagnosis (46%) (12,13), and

its differential diagnosis may include non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

(lymphoblastic, Burkitt and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas),

lymphoblastic leukemia, melanoma, Ewing's sarcoma, primitive

neuroectodermal tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma,

medulloblastoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, blastic plasmacytoid

dendritic cell neoplasm, extramedullary hematopoiesis (13) and small undifferentiated round cell

tumors (6,14).

Previous studies have demonstrated that

immunophenotype is of utmost importance in determining the

diagnosis of GS (3–5). In particular, the literature has focused

on the CD13 and CD68 markers for granular monocytic and macrophagic

cells, MPO and CD117 markers for myeloid differentiation, lysozyme

marker for monocytic lineage, CD43 marker for myeloid cells as well

as T cells and B precursors, and CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase (TdT) markers for immature cells (10). Immunohistochemical detection of

intracellular MPO, a major constituent of primary granules of

neutrophilic myeloid cells, confirms a diagnosis of GS. However,

while MPO is expressed in the majority of GSs, some minimally

differentiated and monocytic GSs do not express it (8).

CD68-KP1 is the most commonly expressed marker,

followed by MPO, CD117, CD99, CD68/PG M1, lysozyme, CD34, TdT,

CD56, CD61/linker of activated T lymphocyte/factor VIII-related

antigen, CD30, glycophorin A and CD4 (3). Rarely, aberrant antigenic expression is

observed (such as cytokeratins, B- or T-cell markers) (3).

In the current case, immunohistochemical evaluation

revealed strong reactivity for CD43, CD34 and CD99, whereas MPO was

negative. In particular, the presence of CD99 made it difficult to

differentiate GS from other CD99-positive round cell tumors

(14), whereas the positivity for

CD34 (15) and the negativity for MPO

indicated the presence of a mass of immature cells. In the present

case, the clinical history of previous AML was the key to the

specific diagnosis of GS.

From a therapeutic perspective, data from the

literature suggest that GSs are extremely sensitive to focal

irradiation or chemotherapy; however, their role is not well

defined (13,16–28). The

optimal treatment for the GS-AML association remains uncertain.

However, high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation may

be the treatment of choice (6).

The risk of metachronous AML in non-leukemic

patients with GS is very high, with a median delay of 5 months; the

majority of patients may develop AML within 1 year. Therefore,

early intensive (induction/intensification) chemotherapy similar to

that used to treat AML must be administered, even in GS patients

without AML upon initial diagnosis (6).

Byrd et al stated that 97% of all primary GS

patients who did not receive systemic chemotherapy developed AML

(12). Furthermore, 66% of patients

who received chemotherapy for the primary GS did not develop AML,

suggesting that early systemic therapy is helpful in preventing

AML, which increases the overall survival time (6).

Literature data demonstrated that clinical behavior

and response to therapy are not influenced by any of the following

factors: Age, gender, anatomic site, de novo presentation,

histotype, phenotype or cytogenetic findings (6).

In the current case, given the previous history of

AML and according to data in the literature, the patient was

treated with conventional induction AML therapy, followed by

radiotherapy. This choice, so far, has proved to be a successful

strategy, since the patient has shown no signs of relapse after

3-year follow-up.

In conclusion, the current study highlights certain

interesting features of GS. Firstly, the negative reactivity for

MPO in the current case suggested the diagnosis of a poorly

differentiated GS with a poor prognosis. Thus, the patient was

assigned to a multidisciplinary protocol of close follow-up for the

high risk of relapse. Secondly, since the rhinopharynx is involved

in a variety of malignant neoplasms, immunohistochemistry is

required for the diagnosis of GS, particularly for the

undifferentiated forms, as in the present case. Indeed, it is not

uncommon for GS to be misdiagnosed as lymphoma. Finally, a

combination of detailed clinical, radiographic and serological

work-ups, in association with a thorough histological assessment,

is essential to establish the correct diagnosis (29).

References

|

1

|

Guermazi A, Feger C, Rousselot P, Merad M,

Benchaib N, Bourrie P, Mariette X, Frija J and de Kerviler E:

Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma): Imaging findings in adults and

children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 178:319–325. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning

RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, Harris NL, Le Beau MM,

Hellström-Lindberg E, Tefferi A and Bloomfield CD: The 2008

revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of

myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: Rationale and important

changes. Blood. 114:937–951. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Campidelli C, Agostinelli C, Stitson R and

Pileri SA: Myeloid sarcoma: Extramedullary manifestation of myeloid

disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 132:426–437. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Vishnu P, Chuda RR, Hwang DG and Aboulafia

DM: Isolated granulocytic sarcoma of the nasopharynx: A case report

and review of the literature. Int Med Case Rep J. 7:1–6. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Alrumaih R, Saleem M, Velagapudi S and

Dababo MA: Lateral pharyngeal wall myeloid sarcoma as a relapse of

acute biphenotypic leukemia: A case report and review of the

literature. J Med Case Rep. 7:2922013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Messager M, Amielh D, Chevallier C and

Mariette C: Isolated granulocytic sarcoma of the pancreas: A tricky

diagnostic for primary pancreatic extramedullary acute myeloid

leukemia. World J Surg Oncol. 10:132012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Noh BW, Park SW, Chun JE, Kim JH, Kim HJ

and Lim MK: Granulocytic sarcoma in the head and neck: CT and MR

imaging findings. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2:66–71. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Papamanthos MK, Kolokotronis AE, Skulakis

HE, Fericean AA, Zorba MT and Matiakis AT: Acute myeloid leukaemia

diagnosed by intra-oral myeloid sarcoma. A Case Report. Head Neck

Pathol. 4:132–135. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hwang JI and Kim TY: Primary granulocytic

sarcoma of the face. Ann Dermatol. 23(Suppl 2): S214–S217. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Raphael J, Valent A, Hanna C, Auger N,

Casiraghi O, Ribrag V, De Botton S and Saada V: Myeloid Sarcoma of

the nasopharynx mimicking an aggressive lymphoma. Head Neck Pathol.

8:234–238. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yilmaz AF, Saydam G, Sahin F and Baran Y:

Granulocytic sarcoma: A systematic review. Am J Blood Res.

3:265–270. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Byrd JC, Edenfield WJ, Shields DJ and

Dawson NA: Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors in acute

nonlymphocytic leukemia: A clinical review. J Clin Oncol.

13:1800–1816. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vachhani P and Bose P: Isolated gastric

myeloid sarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. Case

Rep Hematol. 2014:5418072014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Casiraghi O and Lefèvre M:

Undifferentiated malignant round cell tumors of the sinonasal tract

and nasopharynx. Ann Pathol. 29:296–312. 2009.(In French).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cheng Y, Jia M, Chen Y, Zhao H, Luo Z and

Tang Y: Re-evaluation of various molecular targets located on

CD34+CD38-Lin- leukemia stem cells and other cell subsets in

pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Lett. 11:891–897.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bassichis B, McClay J and Wiatrak B:

Chloroma of the masseteric muscle. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.

53:57–61. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Au WY, Kwong YL, Ho WK and Shek TW:

Primary granulocytic sarcoma of the nasopharynx. Am J Hematol.

67:273–274. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nayak DR, Balakrishnan R, Raj G, Pillai S,

Rao L and Manohar C: Granulocytic sarcoma of the head and neck: A

case report. Am J Otolaryngol. 22:80–83. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Geisse M, Mall G, Fritze D and

Gartenschläger M: Granulocytic sarcoma of the tonsils associated

with myelodysplastic syndrome. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 127:2673–2676.

2002.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Prades JM, Alaani A, Mosnier JF, Dumollard

JM and Martin C: Granulocytic sarcoma of the nasal cavity.

Rhinology. 40:159–161. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ozçelik T, Ali R, Ozkalemkaş F, Ozkocaman

V, Coşkun H, Erişen L and Filiz G: A case of granulocytic sarcoma

during complete remission of acute myeloid leukemia with multiple

masses involving the larynx and nasopharynx. Kulak Burun Bogaz

Ihtis Derg. 11:183–188. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sugimoto Y, Nishii K, Sakakura M, Araki H,

Usui E, Lorenzo VF, Hoshino N, Miyashita H, Ohishi K, Katayama N

and Shiku H: Acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21)(q22;q22)

manifesting as granulocytic sarcomas in the rhinopharynx and

external acoustic meatus at relapse after high-dose cytarabine:

Case report and review of the literature. Hematol J. 5:84–89. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Imamura T, Matsuo S, Yoshihara T,

Chiyonobu T, Mori K, Ishida H, Nishimura Y, Kasubuchi Y, Naya M,

Morimoto A, et al: Granulocytic sarcoma presenting with severe

adenopathy (cervical lymph nodes, tonsils, and adenoids) in a child

with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and successful treatment with

allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Int J Hematol. 80:186–189.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ferri E, Minotto C, Ianniello F, Cavaleri

S, Armato E and Capuzzo P: Maxillo-ethmoidal chloroma in acute

myeloid leukaemia: Case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital.

25:195–199. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Teramoto H, Miwa H, Patel V, Letwin N,

Castellone MD, Imai N, Shikami M, Imamura A, Gutkind JS, Nitta M

and Lee NH: Gene expression changes in a patient presenting

nonleukaemic nasal granulocytic sarcoma to acute myelogenous

leukaemia using 40 K cDNA microarray. Clin Lab Haematol.

28:262–266. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Selvarajan S, Subramanian S, Thulkar S and

Kumar L: Granulocytic sarcoma of nasopharynx with perineural spread

along the trigeminal nerve. Neurol India. 56:210–212. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cho SF, Liu YC, Tsai HJ and Lin SF:

Myeloid sarcoma mimicking nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol.

29:e706–e708. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mei KD, Lin YS and Chang SL: Myeloid

sarcoma of the cheek and the maxillary sinus regions. J Chin Med

Assoc. 76:235–238. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Cantone E, Marino A, Ferranti I and Iengo

M: Nonallergic rhinitis in the elderly: A reliable and safe

therapeutic approach. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 77:117–22.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|