Introduction

Women in whom high-grade cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia (CIN) has been identified and treated require long-term

follow-up compared to the general population (1), because of their increased risk for

disease recurrence (2). However,

evidence-based guidelines to optimize post-therapeutic screening

are still needed (3).

Because of the well-established role of high-risk

human papilloma virus (HPV) in the etiology of cervical cancer, HPV

testing is now accepted to be used to assess recurrence risk after

high-grade CIN treatment. Indispensible insights are gleaned

thereby (2,4,5).

Besides clinician-collected samples, women

themselves can collect vaginal and/or urine samples for HPV

testing. With concerted efforts to maximize self-sampling

reliability (6), using validated

polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays (7), accuracy is reportedly similar from

self-collected compared to clinician-collected samples (8). With these developments, HPV testing

from self-collected samples is becoming a viable, cost-effective

cervical-screening option (9).

In Ref. (10) we

recently examined the views on self-sampling for HPV among 479

women treated for high-grade CIN. The vast majority of these women

considered self-sampling to be easily implementable, and could

envision themselves performing self-sampling at home before their

next gynecologic examination. We concluded that insofar as HPV

self-sampling was as diagnostically accurate as clinician-collected

samples for this high-risk cohort, the former could become an

integral part of the post-therapeutic screening armamentarium.

This possibility becomes especially timely given the

present COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, these women at elevated

risk for cervical cancer could eventually perform at least a part

of the needed screening outside the clinic setting. In a broader

framework, given that long-term follow-up is essential for this

cohort, whether or not HPV self-sampling is a viable option for

these women becomes a critical issue to be examined.

The present study addresses this question, examining

how well positive HPV findings from self-sampled vaginal and urine

specimens, compared to clinician-collected cervical samples,

correctly identify women from this cohort with recurrent high-grade

CIN. We also compare how well HPV findings from self-collected

vaginal and urine samples versus clinician-collected cervical

samples identify women from this cohort with abnormal versus normal

cytology at follow-up. The latter outcome variable currently

impacts directly upon decision-making: Namely, whether the patient

will be triaged for further intensive follow-up or whether she will

be returned to the routine screening program.

Materials and methods

Study design, population and

setting

This study includes patients first-time treated by

conization for histologically-confirmed CIN2+ or

adenocarcinoma-in-situ (AIS) at Stockholm Hospitals: Karolinska

University, Danderyd or South General, from 10/2014-1/2017. The

Research Coordinator, Ellinor Östensson, contacted these patients

shortly after treatment, to arrange 1st follow-up at Karolinska

University Hospital. This 1st follow-up visit was targeted to be at

approximately six months post-treatment. With determined efforts to

schedule a convenient time, all 532 patients attended follow-up

#1.

Upon arrival for follow-up #1, each woman met with

the Research Coordinator (EÖ), who explained the study procedures:

Self-collection of samples for HPV testing; questionnaire [results,

including detailed demographic analysis (10,11)];

gynecologic examination with colposcopy and cervical sampling as

clinical follow-up. The stated study aim was cervical cancer

prevention. Assurance was given of confidentiality and freedom to

withdraw any time without adverse consequences. Informed consent

was signed with the options: Agreement or decline to participate.

All but one patient agreed. Karolinska Ethics Committee approved

the study protocol (2006/1273-31, 2014/2034-3). Thus, the total

number of patients in the present study is 531.

Self-collected samples at follow-up

#1

The participants gave urine samples and carried-out

vaginal self-sampling (VSS) in the care-site restroom. Verbal

instructions were given for collecting initial urine stream in a

plain cup and for VSS with a kit (Qvintip-Aprovix-AB), plus written

description for kit use. The patients were instructed to collect

urine before VSS. Both samples were given to EÖ for handling.

Aprovix AB, Uppsala, Sweden provided Qvintip devices for

self-collection of vaginal material. Abbott provided sample kits

for HPV analyses performed at Fürst Medical Laboratory, Oslo,

Norway. Aprovix and (Abbott had no influence on study design,

statistical analyses, or article writing).

Colposcopy, clinician-collected

cervical samples at follow-up #1

The patients met the gynecologist (Dr Andersson or

Dr Mints), who performed colposcopy and cervical sampling.

Colposcopy-directed punch biopsies were taken from visible lesions,

when present. Histologic grading of biopsies was performed at

Karolinska University Hospital, following standard procedures,

according to CIN classification (12). Samples were taken from the ectocervix

using plastic spatulas and from the endocervix with cervical

brushes, and transferred into PreservCyt liquid-based cytology

(LBC) vials according to European guidelines (13).

Routine follow-up tests, further

patient management

The LBC was performed at the Cytology Department,

Karolinska University Hospital, according to the Bethesda system

(14). The HPV DNA testing was

completed on-site with the hospital's standard: Cobas 4800 HPV

(Roche Diagnostics). Cobas HPV and LBC results from follow-up #1

informed subsequent management: Women with positive Cobas HPV

and/or cytological abnormalities were referred for follow-up #2,

which entailed the same standard protocol as follow-up #1,

according to national guidelines and was most often scheduled at

about one year after follow-up #1. Women with negative HPV Cobas

findings and cytology negative for intraepithelial lesions or

malignancy (NILM) returned to routine triennial screening, as per

national guidelines. When a recurrent lesion was found, the patient

was sent for follow-up treatment. Depending on the clinical

evaluation and other considerations, treatment entailed re-excision

or simple total hysterectomy.

Handling of triplet samples for

comparative HPV testing

Within 1 h of collection, urine samples were

vortexed for 15–20 sec prior to transferring a 2.5 ml aliquot to a

Cervi-Collect transport tube (Abbott-Molecular), containing

transport medium. The tubes were labeled with a unique identifier,

mixed with transport medium by vortexing for 15–20 sec prior to

storage at −10°C or colder up to 1 month before shipment. Urine

samples packed in plastic bags were put in polystyrene boxes with

dry ice for cold-chain maintenance (−78.5°C) during air-transport.

The VSS were air dried for ~3–5 min before the Qvintip device

brush-heads were placed into barcoded capped tubes. The VSS were

stored at room temperature for maximum 1 month before shipment. For

clinician-collected samples, LBC vials were vortexed for 15–20 sec

followed by immediate transfer of a 2 ml aliquot into a test tube

labeled with a unique identifier. The aliquots were stored at room

temperature for maximum 1 month before shipment. All matched

triplet samples (urine, VSS, clinician-collected) were

air-transported from Karolinska University Hospital to the testing

laboratory: Fürst Medical Laboratory, Oslo.

Comparative HPV testing

At Fürst Laboratory, the triplet samples were

analyzed for the presence of HPV-DNA with the RealTime High-Risk

HPV PCR assay (hereafter termed ‘Abbott’), as per manufacturer

instructions. These results were for comparative purposes only and

not considered for patient management.

Abbott is a clinically-validated, qualitative,

multiplex real-time PCR test which detects HPV16, HPV18, plus 12

other high-risk HPV (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66,

68) reported as a pooled signal. The assay detects a sequence of

endogenous human β-globin as sample validity control for

cell adequacy, sample extraction, and amplification efficiency in

each reaction. Signal strength for HPV types and for

β-globin gene was expressed as cycle numbers (CN): The

number of PCR cycles in which a positive signal is observed. High

viral load corresponds to low CN values and vice-verse; 32 was the

cut-off between positive results and noise (negative signal). CN

were reported by the assay software and recorded by the testing

lab. Tests with negative signal for HPV and β-globin were

excluded.

Statistical analysis

Univariate data analysis was performed, with

attention to HPV findings: Any HPV, HPV16, HPV18 or other HPV with

side-by-side comparisons of the methods by which these were

assessed. Pearson χ2 tests (or Fisher's if any expected

cell was <5) were used to assess the relation between biopsy or

cytology vis-à-vis HPV results from each of the four methods.

Biopsy results were dichotomized: (CIN2+ or AIS) vs. (normal

findings or CIN1). Cytology results were dichotomized as abnormal

versus NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy.

Biopsy and cytology results at each follow-up were assessed in

relation to the HPV test results taken at follow-up #1.

Additionally, biopsy and cytology results at follow-up #2 were

analyzed vis-à-vis HPV results from clinician-taken samples at

follow-up #2. Fisher's and Pearson χ2 tests were

employed, respectively, to evaluate the relation between biopsy and

cytology results at follow-up versus HPV16 and/or HPV18 positivity,

as assessed from Abbott clinician-collected samples, VSS and urine

samples. Sensitivity and specificity were computed with 95%

confidence intervals (CI). Negative predictive values (NPV) and

positive predictive values (PPV) were also computed. Using logistic

regression, odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI were computed for

dichotomized clinical outcomes. Each method for assessing HPV

results was the independent variable, with age as a covariate.

Concordance between methods for HPV sampling was assessed using

Cohen's kappa statistic with 95% CI.

Results

Univariate data and protocol by which

the patients were triaged

Altogether, 531 were patients included in the study.

Tables I–III summarize the univariate data. At the

time of treatment, the mean age was 34 years, with most patients

between age 21–50; four were 20 or younger and twenty-seven were

over age 50. The majority of the patients had completed university

education and over 70% were gainfully employed. More detailed

demographic information about the patients can be found in Ref.

(11).

| Table I.Univariate findings for

semi-continuous data. |

Table I.

Univariate findings for

semi-continuous data.

| Variable | No. | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | SD |

|---|

| Age at time of

treatment, years | 531 | 34 | 16 | 66 | 9 |

| Days from treatment

to 1st follow-up | 531 | 184 | 37 | 447 | 40 |

| Days from 1st to

2nd follow-up | 113 | 389 | 9 | 1,291 | 229 |

| Table III.HPV results. |

Table III.

HPV results.

| A, Follow-up 1 |

|---|

|

|---|

| HPV results | Clinician sampled:

Cobas-4800, n | Clinician sampled:

Abbott, n | Self-sampled:

Vaginal, n | Self-sampled:

Urine, na |

|---|

| Positive for any

high-risk type | 86 | 100 | 139 | 85 |

| Negative for any

high-risk type | 445 | 431 | 392 | 402 |

| HPV16 positive |

| 18 | 24 | 16 |

| HPV16 negative |

| 502 | 494 | 462 |

| CN ≥32 |

| 11 | 13 | 9 |

| HPV18 positive |

| 9 | 7 | 5 |

| HPV18 negative |

| 517 | 517 | 476 |

| CN ≥32 |

| 5 | 7 | 6 |

| HPV Other

positive |

| 77 | 117 | 71 |

| HPV Other

negative |

| 423 | 355 | 358 |

| CN ≥32 |

| 31 | 59 | 58 |

|

| B, Follow-up

2b |

|

| HPV

results | Clinician

sampled: Cobas-4800, n | Clinician

sampled: Abbott, n | Self-sampled:

Vaginal, n | Self-sampled:

Urine, na |

|

| Positive for any

high-risk type | 47 |

|

|

|

| Negative for any

high-risk type | 52 |

|

|

|

The histology in the excised cone was CIN2 in 133

patients (25%), CIN3 in 370 patients (69.7%), CIN3/AIS in fifteen

patients (2.8%) and AIS in thirteen patients (2.5%). Most patients

came to follow-up #1 within eight months.

Table IIA shows that

at follow-up #1, recurrent CIN2+ (CIN3 in all cases) was found in

four of thirteen patients who underwent biopsy (30.8%). Thus, at

1st follow-up the diagnosed recurrence rate among the 531 patients

was 0.8%. At follow-up #2, biopsy was performed in twenty patients,

including the four who had recurrent CIN2+ at follow-up

#1. Nine more patients were found to have recurrence on biopsy:

Seven with CIN2+ and two with AIS among those sixteen

patients (56.3%) who underwent biopsy at follow-up #2, excluding

the four patients with CIN3 who underwent repeat biopsy at

follow-up #2. The newly diagnosed recurrence rate among the

remaining 109 patients who came to 2nd follow-up was thus 8.3%.

| Table II.Univariate findings for biopsy and

cytology results. |

Table II.

Univariate findings for biopsy and

cytology results.

| A, Biopsy

results |

|---|

|

|---|

| Variable | Follow-up 1, n | Follow-up 1, % | Follow-up 2, n | Follow-up 2, % |

|---|

| Within normal

limits | 6 | 46 | 2 | 13 |

| CIN1 | 3 | 23 | 5 | 31 |

|

CIN2+ | 4 | 31 | 7a | 44 |

| AIS | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

|

| B, Cytology

results (via LBC) |

|

|

Variable | Follow-up 1,

n | Follow-up 1,

% | Follow-up 2,

nb | Follow-up 2,

% |

|

| NILM | 454 | 86 | 75 | 68 |

| ASC-US | 28 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| AGC | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| LSIL | 27 | 5 | 14 | 13 |

| ASC-H | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HSIL | 16 | 3 | 12 | 11 |

| AIS | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

On Table IIB, for

follow-up #1, seventy-seven patients had abnormal cytology,

eighty-six patients had HPV positive findings according to the

standard clinician-taken COBAS analysis and thirty-seven patients

had both positive HPV via COBAS and abnormal cytology. Thus,

altogether, 126 patients were referred to 2nd follow-up, 113 of

whom attended. Most patients had NILM on cytology at follow-up #2.

One patient had AIS and ~11% had high-grade squamous

intraepithelial lesions (HSIL).

Table III further

reveals that testing for any high-risk HPV at follow-up #1 yielded

all valid results for clinician-collected samples and VSS; 44 urine

samples were ‘invalid’ due to absent HPV and β-globin. For

HPV16 or HPV18, there were more omitted results due to CN ≥32 for

VSS than for clinician-collected samples. For HPV16 VSS showed the

highest positivity rate (4.6%), whereas for HPV18,

clinician-samples had the highest positivity rate (1.7%). Overall,

VSS yielded the largest number of positive results for HPV16 and

for other high-risk HPV.

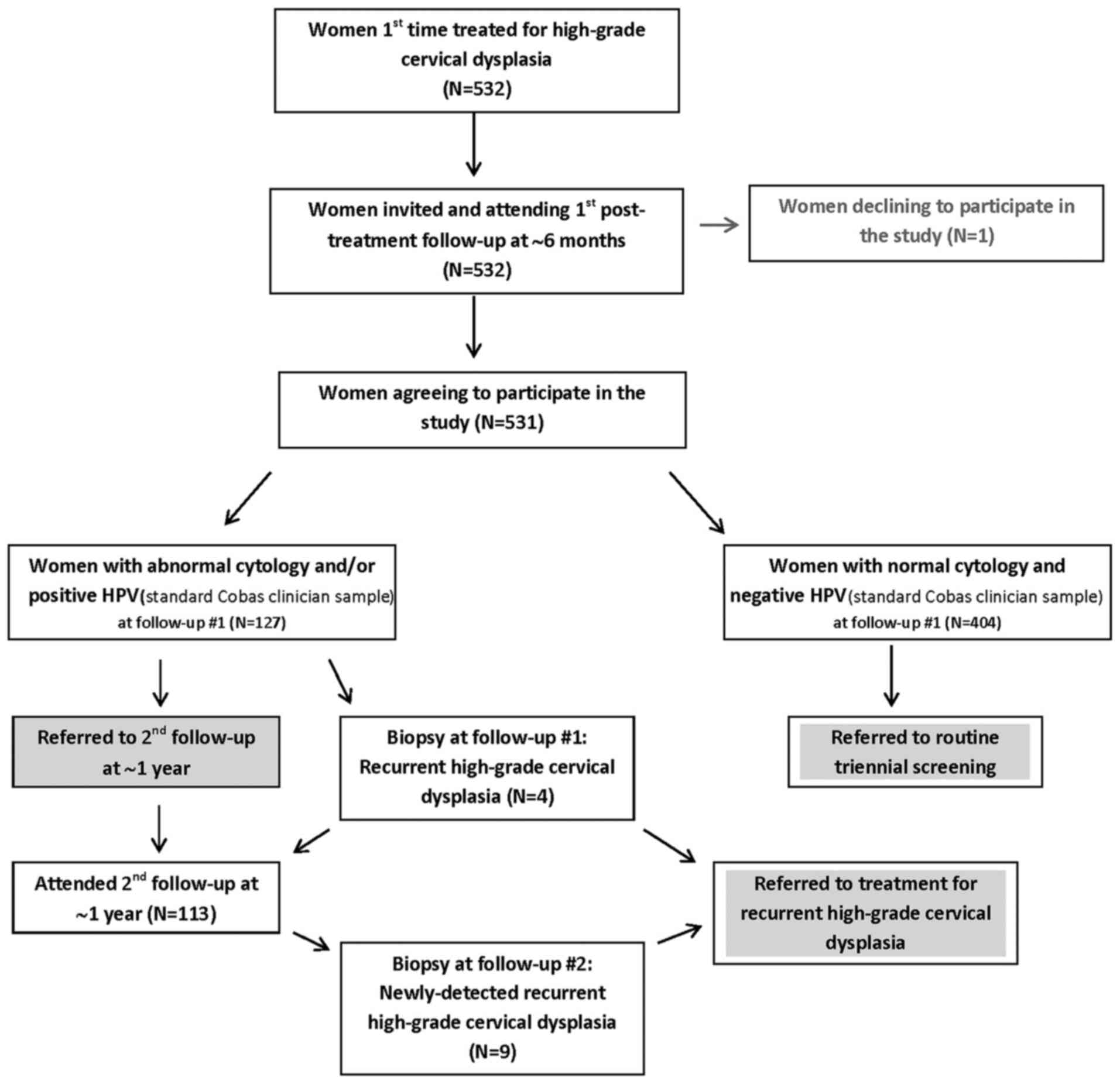

Fig. 1 summarizes the

protocol according to which the patients were triaged. Numerical

information is provided therein concerning the various

outcomes.

HPV findings in relation to the biopsy

results

Table IV presents

the predictive value of HPV findings vis-à-vis biopsy results. All

4 methods revealed positive HPV findings in the four patients with

recurrent CIN2+ at follow-up #1. Two patients showed

positive HPV16 and/or HPV18 results with clinician-sampling and

VSS. For all the patients who underwent biopsy, the HPV16 and 18

results were complete for clinician-sampling and VSS. However, for

the urine self-samples, at follow-up #1 the results for HPV16

and/or HPV18 were missing due to CN >32 for one patient with

recurrent CIN2+ and at follow-up #2 for two patients:

One with recurrent CIN2+ and one with AIS.

| Table IV.Predictive value of HPV findings

vis-à-vis biopsy results. |

Table IV.

Predictive value of HPV findings

vis-à-vis biopsy results.

| A, HPV vs. biopsy

results at follow-up #1 |

|---|

|

|---|

| HPV results | Normal, n | CIN1, n | P-value | CIN2+, n | AIS, n | Sensitivity, % (95%

CI) | Specificity, % (95%

CI) | NPV, % | PPV, % |

|---|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Cobas-4800 |

|

|

|

|

| 100 (40–100) | 67 (30–93) | 100 | 57 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 5 | 1 | ≤0.09 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Abbott |

|

|

|

|

| 100 (40–100) | 67 (30–93) | 100 | 57 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 5 | 1 | ≤0.09 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16 and/or

18 |

|

|

|

|

| 50 (7–93) | 67 (30–93) | 75 | 40 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and HPV18 negative | 5 | 1 | NS | 2 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-sampled:

Vaginal |

|

|

|

|

| 100 (40–100) | 67 (30–93) | 100 | 57 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 2 | 1 | ≤0.09 | 4 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 4 | 2 |

| 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16 and/or

18 |

|

|

|

|

| 50 (7–93) | 78 (40–97) | 78 | 50 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and HPV18 negative | 5 | 2 | NS | 2 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Urine |

|

|

|

|

| 100 (40–100) | 67 (30–93) | 100 | 57 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 4 | 2 | ≤0.09 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16 and/or

18a |

|

|

|

|

| 33 (1–91) | 78 (40–97) | 78 | 33 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and HPV18 negative | 5 | 2 | NS | 2 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| B, HPV results

at follow-up #1 vs. biopsy results at follow-up #2b |

|

| HPV

results | Normal,

n | CIN1, n | P-value | CIN2+,

n | AIS, n | Sensitivity, %

(95% CI) | Specificity, %

(95% CI) | NPV, % | PPV, % |

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Cobas-4800 |

|

|

|

|

| 89 (52–100) | 43 (10–82) | 75 | 67 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 0 | 4 |

| 7 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 2 | 1 | NS | 0 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Abbott |

|

|

|

|

| 100 (66–100) | 43 (10–82) | 100 | 69 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 0 | 4 | ≤0.09 | 7 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 2 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16 and/or

18 |

|

|

|

|

| 56 (21–86) | 100 (59–100) | 64 | 100 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 0 | 0 | <0.05 | 3 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16

and 18 negative | 2 | 5 |

| 4 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Vaginal |

|

|

|

|

| 78 (40–97) | 43 (10–82) | 60 | 64 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 0 | 4 | NS | 7 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 2 | 1 |

| 0 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16 and/or

18 |

|

|

|

|

| 44 (14–79) | 100 (59–100) | 58 | 100 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16

and 18 negative | 2 | 5 | ≤0.09 | 3 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Urine |

|

|

|

|

| 56 (21–86) | 71 (29–96) | 56 | 71 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 2 | 3 | NS | 2 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16 and/or

18c |

|

|

|

|

| 43 (10–82) | 100 (59–100) | 64 | 100 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16

and 18 negative | 2 | 5 | NS | 3 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| C, HPV results

at follow-up #2 vs. biopsy results at follow-up #2 |

|

| HPV

results | Normal,

n | CIN1, n | P-value | CIN2+,

n | AIS, n | Sensitivity, %

(95% CI) | Specificity, %

(95% CI) | NPV, % | PPV, % |

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Cobas-4800d |

|

|

|

|

| 100 (63–100) | 33 (4–78) | 100 | 67 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 0 | 4 |

| 6 | 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 1 | 1 | NS | 0 | 0 |

|

|

|

|

Both clinician-sampling methods and VSS, all taken

at follow-up #1, revealed HPV positive findings in the seven

patients with newly-detected CIN2+ at follow-up #2. From

urine self-samples, HPV positivity was seen in five of those

patients. Only Abbott clinician-taken samples were HPV positive for

both patients with AIS at follow-up #2; in both cases HPV18 was

also positive.

As noted at the end of Table IV, eight of the nine patients with

high-grade cervical dysplasia on biopsy at follow-up #2 showed HPV

positivity via the standard assessment with Cobas clinician

sampling taken at follow-up #2. The HPV data were missing for the

ninth patient with recurrent high-grade CIN detected on biopsy at

follow-up #2. With clinician sampling using the Abbott assay, all

nine cases with high-grade cervical dysplasia on biopsy showed HPV

positivity at follow-up #1. Thus, it appears that these

biopsy-diagnosed recurrent cases at follow-up #2 had persistent HPV

positivity.

HPV findings in relation to the

cytology results

Table V shows the HPV

findings in relation to abnormal cytology versus NILM. At follow-up

#1, overall HPV positivity from VSS was most sensitive in

predicting abnormal cytology. Further analysis revealed positive

HPV findings from VSS in twelve patients with HSIL, whereas eleven

patients with HSIL had positive HPV findings on clinician-taken and

urine samples. Positivity for HPV16 and/or HPV18 showed low

sensitivity for predicting abnormal cytology at follow-up#1, but

very high NPV and specificity with all three methods. At follow-up

#2, twenty-eight patients with abnormal cytology had HPV positive

findings with VSS and both clinician-samples from follow-up #1.

With missing data for urine samples, there were fewer cases of

positive HPV associated with abnormal cytology at both

follow-ups.

| Table V.Predictive value of HPV findings

vis-à-vis cytology results. |

Table V.

Predictive value of HPV findings

vis-à-vis cytology results.

| A, HPV vs. cytology

results (both at follow-up #1) |

|---|

|

|---|

| HPV results | NILM, n | P-value | Abnormal, n | Sensitivity, % (95%

CI) | Specificity, % (95%

CI) | NPV, % | PPV, % |

|---|

|

Clinician-Sampled:Cobas-4800 |

|

|

| 48 (37–60) | 89 (86–92) | 91 | 43 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 49 | <0.001 | 37 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 405 |

| 40 |

|

|

|

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Abbott |

|

|

| 49 (38–61) | 86 (83–89) | 91 | 38 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 62 | <0.001 | 38 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 392 |

| 39 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16 and/or

18a |

|

|

| 14 (7–24) | 96 (94–98) | 87 | 41 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 16 | <0.001 | 11 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and 18 negative | 423 |

| 66 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Vaginal |

|

|

| 51 (39–62) | 78 (74–82) | 90 | 28 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 100 |

| 39 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 354 | <0.001 | 38 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16 and/or

18b |

|

|

| 12 (6–21) | 95 (92–97) | 86 | 41 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 22 | <0.05 | 9 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and 18 negative | 413 |

| 67 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Urinec |

|

|

| 43 (31–55) | 87 (83–90) | 90 | 37 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 54 | <0.001 | 31 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 360 |

| 42 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16 and/or

18d |

|

|

| 13 (6–23) | 97 (95–99) | 87 | 43 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 12 | <0.001 | 9 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and 18 negative | 392 |

| 60 |

|

|

|

|

|

| B, HPV at

follow-up #1 vs. cytology results at follow-up #2 |

|

| HPV

results | NILM, n | P-value | Abnormal,

n | Sensitivity, %

(95% CI) | Specificity, %

(95% CI) | NPV, % | PPV, % |

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Cobas-4800 |

|

|

| 80 (63–92) | 36 (25–48) | 79 | 37 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 48 | NS | 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 27 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

| Clinician-Sampled:

Abbott |

|

|

| 80 (63–92) | 40 (29–52) | 81 | 38 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 45 | <0.05 | 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 30 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16 and/or

18e |

|

|

| 23 (10–40) | 85 (75–92) | 70 | 42 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 11 | NS | 8 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and 18 negative | 63 |

| 27 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Vaginal |

|

|

| 80 (63–92) | 36 (25–48) | 79 | 37 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 48 | NS | 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 27 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16 and/or

18e |

|

|

| 20 (8–37) | 85 (75–92) | 69 | 39 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 11 | NS | 7 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and 18 negative | 63 |

| 28 |

|

|

|

|

| Self-Sampled:

Urinef |

|

|

| 68 (50–83) | 58 (45–69) | 79 | 43 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 30 | <0.05 | 23 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 41 |

| 11 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV 16 and/or

18g |

|

|

| 16 (6–34) | 88 (78–95) | 69 | 39 |

| HPV16

and/or 18 positive | 8 | NS | 5 |

|

|

|

|

| HPV16

and 18 negative | 59 |

| 26 |

|

|

|

|

|

| C, HPV results

at follow-up #2 vs. cytology results at follow-up #2 |

|

| HPV

results | NILM, n | P-value | Abnormal,

n | Sensitivity, %

(95% CI) | Specificity, %

(95% CI) | NPV, % | PPV, % |

|

|

Clinician-sampled:Cobas-4800h |

|

|

| 84 (66–95) | 68 (55–79) | 90 | 57 |

|

Positive for any high-risk

type | 20 | <0.001 | 26 |

|

|

|

|

|

Negative for any high-risk

type | 43 |

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

Table VI presents

the significant logistic regression models predicting abnormal

cytology at follow-up #1. All four methods yielded significant

age-adjusted ORs. None of the methods generated significant

age-adjusted models for predicting cytology at follow-up #2. The

small number of biopsies precluded multivariate analysis.

| Table VI.Clinician-sampled and self-sampled

HPV for predicting abnormal cytology at follow-up#1 assessed via

multiple logistic regression models with adjustment for age. |

Table VI.

Clinician-sampled and self-sampled

HPV for predicting abnormal cytology at follow-up#1 assessed via

multiple logistic regression models with adjustment for age.

| Model

χ2 | Variable | OR | −95% CI | +95% CI |

|---|

| 54.6a (n=531) | Cobas

Clinician-sample HPV positive | 7.62a | 4.44 | 13.10 |

|

| Age | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

| 46.6a (n=531) | Abbott

Clinician-sample HPV positive | 6.13a | 3.63 | 10.40 |

|

| Age | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

| 27.7a (n=531) | Vaginal Self-sample

HPV positive | 3.71a | 2.24 | 6.13 |

|

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.00 |

| 32.0a (n=487)b | Urine Self-sample

HPV positive | 4.84a | 2.80 | 8.39 |

|

| Age | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

Concordance between the methods for

assessing HPV

The highest Cohen's kappa was for the two

clinician-sampling methods (Table

VII). Agreement was substantial between VSS and

clinician-sampling methods, and moderate for urine sampling versus

clinician-sampling or VSS. For valid HPV16 there was close

agreement for each pair. Agreement was substantial between

clinician and VSS for HPV18. Concordance between clinician and

urine sampling was fair for HPV18; VSS versus urine sampling

agreement was moderate. Concordance was substantial for the three

methods assessing other HPV.

| Table VII.Pairwise concordance between methods

for HPV assessment using Cohen's kappa. |

Table VII.

Pairwise concordance between methods

for HPV assessment using Cohen's kappa.

| Variable | Abbott

clinician | Vaginal

self-sample | Urine

self-sample |

|---|

| Overall HPV |

| Cobas

clinician | 0.83

(0.77–0.89) | 0.63

(0.55–0.71) | 0.53

(0.42–0.64)a |

| Abbott

clinician |

| 0.68

(0.60–0.76) | 0.58

(0.48–0.68)a |

| Vaginal

self-sample |

|

| 0.60

(0.51–0.69)a |

| HPV16 |

| Abbott

clinician |

| 0.89

(0.77–1.00)b | 0.85

(0.70–1.00)c |

| Vaginal

self-sample |

|

| 0.83

(0.69–0.97)c |

| HPV18 |

| Abbott

clinician |

| 0.71

(0.43–0.99)d | 0.36

(0.00–0.81)e |

| Vaginal

self-sample |

|

| 0.60

(0.15–1.00)f |

| Other HPV |

| Abbott

clinician |

| 0.79

(0.71–0.87)g | 0.73

(0.63–0.83)h |

| Vaginal

self-sample |

|

| 0.78

(0.70–0.86)i |

Discussion

The present results indicate that VSS is as

sensitive as clinician-collected samples for predicting recurrent

high-grade pathohistologic results on biopsy and cytologic

abnormalities among women treated for high-grade CIN, unless the

pathology is glandular. Urine self-sampling yielded slightly poorer

sensitivity compared to VSS.

Our results for VSS cohere with the literature

concerning the value of post-therapeutic HPV testing from

clinician-collected samples for predicting subsequent outcome among

patients treated for high-grade CIN (2,5,15–19).

Higher positivity rates of VSS compared to clinician-taken samples

for overall HPV and HPV16 found herein, were also reported in

Reference (20).

Positive HPV findings have been shown to powerfully

predict high-grade cervical lesions among patients with glandular

pathology (21,22). Positive HPV18 is strongly associated

with cervical adenocarcinoma risk, especially in its more

aggressive form (23,24). In our cohort, it was only HPV18 which

was less frequently detected with VSS compared to

clinician-collected samples.

To our knowledge, there is only one other study

evaluating self-sampling versus clinician-collected samples as

follow-up among patients treated for high-grade CIN (25). In Reference (25) fifty-two of 103 treated patients

(50.4%) participated in tri-monthly urine self-collection and

cervical scrapings. All three cases of CIN2+ detected

during one-year follow-up showed repeated positive HPV findings on

self-sampled urine and cervical scrapings. All pre-treatment and

recurrent findings were squamous in Reference (25).

A recent investigation (26) comparing histologic findings and

triple HPV results in women undergoing colposcopy revealed that

urine-based HPV testing was somewhat less sensitive in identifying

women with high-grade CIN, compared to VSS and provider-sampled HPV

results, similarly to our study. Our samples were from the initial

urine stream, thought to contain highest concentrations of

diagnostically relevant components (27) and to be more accurate for detecting

cervical HPV than mid-stream or end-stream samples (28). Timing of collection may also impact

the amount of viral DNA in the sample, since more HPV DNA could be

present with an increased interval between two urinations because

more excreted mucus and debris from the genital organs can

accumulate (4). Thus, there should

be sufficient time between urine collection and previous urination

(29). We specifically instructed

the participants to collect urine samples before VSS to avoid

interfering with the material from the cervicovaginal tract.

However, the urine samples were not collected first-void in the

morning, but randomly during the day. We paid careful attention to

storage conditions and preparation of urine samples, in light of

their importance for HPV DNA detection (30). Nevertheless, 44 of the 531 urine

samples were invalid due to absence of high-risk HPV and

β-globin, whereas all VSS and clinician-collected samples

were valid.

Assessment of HPV16 and/or HPV18 was nearly always

associated with higher specificity than overall HPV findings. This

is particularly notable for VSS for which there was the largest

number, 100, of overall HPV positive findings associated with

normal cytology at follow-up #1, whereas only twenty-two patients

with normal cytology showed positive HPV16 and/or HPV18 findings on

VSS. The importance of assessing HPV16 and 18 was underscored in

the review of patterns of HPV infection after treatment of

high-grade CIN (3).

The present findings indicate that VSS could be a

viable option for follow-up of women treated for high-grade CIN, if

the pathology is squamous. In considering the self-sampling option,

the advantages and disadvantages need to be presented to the

patient. Namely, the chances of false positive findings are a bit

higher with VSS than with clinician-sampling, such that repeated

self-sampling might be needed. This is reflected in a much higher

percentage of positive ‘other HPV’ with VSS, compared to

clinician-sampling. Notably, among women below age 30, positive

findings only for other HPV may not impact substantially upon risk

of future high-grade CIN (31).

Also, for HPV16, 18 and other HPV, but not for overall HPV results,

there was a somewhat larger chance of a missing result with VSS

(due to above-threshold CN values). Thus, women who would be

comfortable and willing to repeat home self-sampling could choose

the VSS option.

Based on these results, our recommendation would be

against self-sampling for patients with glandular pathology. This

recommendation is based on the two patients with recurrence in whom

VSS did not yield a positive result, both of whom had glandular

pathology. In both these patients, clinician-sampling revealed

HPV18 positivity, which, as noted, appears to be a particularly

important risk indicator (23,24). To

more completely address this cautious clinical recommendation,

further research is needed vis-à-vis self-sampling for follow-up

among treated patients with glandular pathology, with special

attention to HPV18. Longer follow-up and repeated HPV assessments

are also needed in future studies comparing self-sampling and

clinician-sampling among patients treated for high-grade CIN.

Practically complete data were available for this

cohort of patients followed-up post-conization treatment for

CIN2+ or AIS. To our knowledge, this is the largest,

most complete follow-up study in which HPV results were compared

for two different clinician-sampling methods and two different

self-sampling methods. Besides biopsy data, complete cytology data

were available for all 531 patients. Inclusion of this latter

outcome-variable provides further insight into the post-therapeutic

clinical status of these patients. However, follow-up thereafter is

limited; only 21% attended follow-up #2. Of 127 patients referred

to follow-up #2 for abnormal cytology and/or HPV positive findings

from standard COBAS clinician samples, 113 patients attended. The

404 patients with normal cytology and negative HPV findings from

standard-COBAS clinician-samples returned to routine screening,

without follow-up within this study. The latter includes fifty-nine

patients with positive HPV findings on VSS and/or Abbott

clinician-sampling. Another limitation of the study may have been

reliance upon colposcopically-visible lesions for biopsy. This

could have underestimated the actual number of recurrences, since

biopsies taken from colposcopically negative sites may also

identify patients with high-grade cervical dysplasia (32).

All participants performed self-sampling in the

clinic restroom. Questionnaire data were available from 479 of 531

patients concerning their readiness to perform self-sampling at

home and whether self-sampling was easy to carry-out. These

statements were endorsed, respectively, by 74 and 86% of the 479

women. In a study using the same questionnaire (33), forty-one long-term screening

non-attenders performed VSS at home with positive HPV results, for

which they subsequently underwent gynecologic examination. All

forty-one patients endorsed both statements regarding

self-sampling; 95% cited comfort as a reason for performing

self-sampling. In contrast, only 14% of the women in the present

study cited comfort as a reason for performing self-sampling.

Indeed, the home-setting is more comfortable for carrying-out VSS.

Home self-sampling is also practical and cost-effective for

repeated assessment. On the other hand, the quality of home

self-sampling might not be as high as self-sampling performed in

the clinic immediately after specific instructions are directly

given. This underscores the need to provide very clear written

instructions, and that health professionals are easily accessible

to answer any queries that arise when performing self-sampling at

home.

The home self-sampling option could be particularly

favorable as an alternative to clinic visits in face of the current

COVID19-pandemic, plus being convenient and cost-effective

(9). Self-collection of samples for

HPV testing is becoming an increasingly accepted, and even

preferred cervical screening option for many women (34–42).

The present findings concerning urine self-sampling

cohere substantially with the literature. In home-based settings

for collecting first-void urine (27), urine self-sampling may also hold

promise for follow-up after treatment for high-grade CIN.

These considerations reflect more personalized

approaches for women at elevated risk of recurrent high-grade CIN.

Embodied therein is empowerment, whereby women would be

well-informed about available options, actively participating in

decision-making regarding cervical screening. Such a strategy has

been successful in other cervical screening contexts (43,44) and

is likely to enhance fuller participation in the needed long-term

follow-up for these women at increased cervical cancer risk.

In conclusion, for patients with squamous cell

pathology, post-therapeutic follow-up based on HPV analysis from

self-collected vaginal samples appears to be as sensitive as HPV

analysis from clinician-collected cervical samples for predicting

outcome. Based on a very small number of patients with the far less

common glandular pathology, the present study suggests that vaginal

self-sampling is not adequately sensitive, such that HPV analysis

should be based on clinician-collected cervical samples when

assessing risk of recurrence. The vast majority of patients treated

for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia have squamous

pathology. For these patients, vaginal self-sampling for HPV

analysis may well be a viable option that can maximize

participation in the needed long-term follow-up for these women at

increased cervical cancer risk.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Swedish

Cancer Foundation (grant no. 110544, CAN2011/471), Karolinska

Institute (Cancer Strategic Grants; grant no. 5888/05-722), Swedish

Research Council (grant no. 521-2008-2899), Stockholm County

Council (grant nos. 20130097 and 20160155) and Gustaf V Jubilee

Fund (grant nos. 154022 and 151202).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

EÖ participated in the design and conception of the

study, was responsible for identifying and recruiting all the

participants, met with all the participants, gave the instructions

for self-sampling, prepared the self-samples for transport,

assessed the authenticity of the raw data, prepared the data set

for analysis, collected the related literature, participated in

drafting the manuscript and revised the manuscript. KB performed

the statistical analysis, collected the related literature, and

wrote and revised the manuscript. TR contributed to the

interpretation of the HPV data and revised the manuscript. MM

participated in the design and conception of the study, performed

colposcopy, cervical sampling and punch biopsies of visible

lesions, and revised the manuscript. SA conceived and designed the

study, performed colposcopy, cervical sampling and punch biopsies

of visible lesions, assessed the authenticity of the raw data,

reviewed the data, collected the related literature, and revised

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Karolinska Ethics Committee approved the study

protocol (2006/1273-31, 2014/2034-3). Informed consent by each

patient was signed with options: Agreement or decline to

participate.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AIS

|

adenocarcinoma-in-situ

|

|

CI

|

confidence interval

|

|

CIN

|

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

|

|

CN

|

cycle numbers

|

|

HPV

|

high-risk human papillomavirus

|

|

HSIL

|

high-grade

squamous-intraepithelial-lesions

|

|

LBC

|

liquid based cytology

|

|

NILM

|

negative for intraepithelial lesions

or malignancy

|

|

NPV

|

negative predictive value

|

|

PCR

|

polymerase chain reaction

|

|

PPV

|

positive predictive value

|

|

OR

|

odds ratio

|

|

VSS

|

vaginal self-sampling

|

References

|

1

|

Ebisch RMF, Rutten DWF, IntHout J,

Melchers WJG, Massuger LFAG, Bulten J, Bekkers RLM and Siebers AG:

Long-lasting increased risk of human papillomavirus-related

carcinomas and premalignancies after cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia grade 3: A population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol.

35:2542–2550. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kocken M, Helmerhorst TJ, Berkhof J,

Louwers JA, Nobbenhuis MA, Bais AG, Hogewoning CJ, Zaal A,

Verheijen RH, Snijders PJ and Meijer CJ: Risk of recurrent

high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after successful

treatment: A long-term multi-cohort study. Lancet Oncol.

12:441–450. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hoffman SR, Le T, Lockhart A, Sanusi A,

Dal Santo L, Davis M, McKinney DA, Brown M, Poole C, Willame C and

Smith JS: Patterns of persistent HPV infection after treatment for

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN): A systematic review. Int

J Cancer. 141:8–23. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, Meijer CJ,

Poljak M, Ogilvie G, Koliopoulos G, Naucler P, Sankaranarayanan R

and Peto J: Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in

secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine. 30 (Suppl

5):F88–F99. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bruhn LV, Andersen SJ and Hariri J:

HPV-testing versus HPV-cytology co-testing to predict the outcome

after conization. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 97:758–765. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, Verhoef

VM, Suonio E, Dillner L, Minozzi S, Bellisario C, Banzi R, Zhao F,

et al: Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected

versus clinician-collected samples: A meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol.

15:172–183. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Arbyn M, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Berkhof

J, Cuschieri K, Kocjan BJ and Poljak M: Which high-risk HPV assays

fulfill criteria for use in primary cervical cancer screening? Clin

Microbiol Infect. 21:817–826. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jentschke M, Chen K, Arbyn M, Hertel B,

Noskowicz M, Soergel P and Hillemans P: Direct comparison of two

vaginal self-sampling devices for the detection of human

papillomavirus infections. J Clin Virol. 82:46–50. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Östensson E, Hellström AC, Hellman K,

Gustavsson I, Gyllensten U, Wilander E, Zethraeus N and Andersson

S: Projected cost-effectiveness of repeat HPV testing using

self-collected vaginal samples in the Swedish cervical cancer

screening program. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 92:830–840. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Andersson S, Belkić K, Mints M and

Östensson E: Is self-sampling to test for high-risk papillomavirus

an acceptable option among women who have been treated for

high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia? PLoS One.

13:e01990382018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Andersson S, Belkić K, Safer Demirbüker

SS, Mints M and Östensson E: Perceived cervical cancer risk among

women treated for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia:

The importance of specific knowledge. PLoS One. 12:e1901562017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Richart RM: Cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia. Pathol Annu. 8:301–328. 1973.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jordan J, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M,

Schenck U, Baldauf JJ, Da Silva D, Anttila A, Nieminen P and

Prendiville W: European guidelines for clinical management of

abnormal cervical cytology, part-2. Cytopathology. 20:5–16. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A,

O'Connor D, Prey M, Raab S, Sherman M, Wilbur D, Wright T Jr, et

al: The 2001 Bethesda system: Terminology for reporting results of

cervical cytology. JAMA. 287:2114–2119. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Brismar S, Johansson B, Borjesson M, Arbyn

M and Andersson S: Follow-up after treatment of cervical

intraepithelial neoplasia by human papillomavirus genotyping. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 201:17.e1–8. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kocken M, Uijterwaal MH, de Vries AL,

Berkhof J, Ket JC, Helmerhorst TJ and Meijer CJ: High-risk human

papillomavirus testing versus cytology in predicting post-treatment

disease in women treated for high-grade cervical disease: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 125:500–507.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Persson M, Brismar Wendel S, Ljungblad L,

Johansson B, Weiderpass E and Andersson S: High-risk human

papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA and L1 DNA as markers of

residual/recurrent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Oncol Rep.

28:346–352. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Asciutto KC, Henic E, Darlin L, Forslund O

and Borgfeldt C: Follow up with HPV test and cytology as test of

cure, 6 months after conization, is reliable. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand. 95:1251–1257. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Garutti P, Borghi C, Bedoni C, Bonaccorsi

G, Greco P, Tognon M and Martini F: HPV-based strategy in follow-up

of patients treated for high-grade cervical intra-epithelial

neoplasia: 5-year results in a public health surveillance setting.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 210:236–241. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Saville M, Hawkes D, Keung M, Ip E,

Silvers J, Sultana F, Malloy MJ, Velentzis LS, Canfel LK, Wrede CD

and Brotherton J: Analytical performance of HPV assays on vaginal

self-collected vs. practitioner-collected cervical samples. J Clin

Virol. 127:1043752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Norman I, Hjerpe A and Dillner J: Risk of

high-grade lesions after atypical glandular cells in cervical

screening: A population-based cohort study. BMJ Open.

7:e0170702017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Patadji S, Li Z, Pradhan D and Zhao C:

Significance of high-risk HPV detection in women with atypical

glandular cells on pap testing: Analysis of 1857 cases from an

academic institution. Cancer Cytopathol. 125:205–211. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Andersson S, Larson B, Hjerpe A,

Silfverswärd C, Sällström J, Wilander E and Rylander E:

Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: The presence of human

papillomavirus and the method of detection. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand. 82:960–965. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dahlström LA, Ylitalo N, Sundström K,

Palmgren J, Ploner A, Eloranta S, Sanjeevi CB, Andersson S, Rohan

T, Dillner J, et al: Prospective study of human papillomavirus and

risk of cervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 127:1923–1930. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fambrini M, Penna C, Pieralli A, Bussani

C, Fallani MG, Andersson KL, Scarselli G and Marchionni M: PCR

detection rates of high risk human papillomavirus DNA in paired

self-collected urine and cervical scrapes after laser CO2

conization for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Gynecol Oncol. 109:59–64. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rohner E, Rahangdale L, Sanusi B, Knittel

AK, Vaughan L, Chesko K, Faherty B, Tulenko SE, Schmitt JW, Romocki

LS, et al: Test accuracy of human papillomavirus in urine for

detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Microbiol.

58:e01443–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Vorsters A, Van Damme P and Clifford G:

Urine testing for HPV: Rationale for using first void. BMJ.

349:g62522014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pathak N, Dodds J, Zamora J and Khan K:

Accuracy of urinary human papillomavirus testing for presence of

cervical HPV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ.

349:g52642014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pattyn J, Van Keer S, Biesmans S, Ieven M,

Vanderborght C, Beyers K, Vankerckhoven V, Bruyndonckx R, Van Damme

P and Vorsters A: Human papillomavirus detection in urine: Effect

of a first-void urine collection device and timing of collection. J

Virol Methods. 264:23–30. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Vorsters A, Micalessi I, Bilcke J, Ieven

M, Bogers J and Van Damme P: Detection of human papillomavirus DNA

in urine. A review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect

Dis. 31:627–640. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fröberg M, Östensson E, Belkić K, Oštrbenk

A, Poljak M, Mints M, Arbyn M and Andersson S: Impact of the human

papillomavirus status on development of high-grade cervical

intraepithelial neoplasia in women negative for intraepithelial

lesions or malignancy at baseline: A 9-year Swedish nested

case-control follow-up study. Cancer. 125:239–248. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Baasland I, Hagen B, Vogt C, Valla M and

Romundstad PR: Colposcopy and additive diagnostic value of biopsies

from colposcopy-negative areas to detect cervical dysplasia. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand. 95:1258–1263. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Andersson S, Belkić K, Mints M and

Östensson E: Acceptance of self-sampling among long-term cervical

screening non-attenders with HPV positive results: Promising

opportunity for specific cancer education. J Cancer Educ.

36:126–133. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Galbraith KV, Gilkey MB, Smith JS, Richman

AR, Barclay L and Brewer NT: Perceptions of mailed HPV self-testing

among women at higher risk for cervical cancer. J Community Health.

39:849–856. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Crofts V, Flahault E, Tebeu PM, Untiet S,

Fosso GK, Boulvain M, Vassilakos P and Petignat P: Education

efforts may contribute to wider acceptance of human papillomavirus

self-sampling. Int J Womens Health. 7:149–154. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Arrossi S, Ramos S, Straw C, Thouyaret L

and Orellana L: HPV testing: A mixed-method approach to understand

why women prefer self-collection in a middle-income country. BMC

Public Health. 16:8322016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ma'som M, Bhoo-Pathy N, Nasir NH,

Bellinson J, Subramaniam S, Ma Y, Yap SH, Goh PP, Gravitt P and Woo

YL: Attitudes and factors affecting acceptability of

self-administered cervicovaginal sampling for human papillomavirus

(HPV) genotyping as an alternative to Pap testing among multiethnic

Malaysian women. BMJ Open. 6:e0110222016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vahabi M and Lofters A: Muslim immigrant

women's views on cervical cancer screening and HPV self-sampling in

Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. 16:8682016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Racey CS and Gesink DC: Barriers and

facilitators to cervical cancer screening among women in rural

Ontario, Canada: The role of self-collected HPV testing. J Rural

Health. 32:136–145. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

de Melo Kuil L, Lorenzi AT, Stein MD,

Resende JCP, Antoniazzi M, Longatto-Filho A, Scapulatempo-Neto C

and Fregnani JHTG: The role of self-collection by vaginal lavage

for the detection of HPV and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

Acta Cytol. 61:425–433. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mao C, Kulasingam SL, Whitham HK, Hawes

SE, Lin J and Kiviat NB: Clinician and patient acceptability of

self-collected human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer

screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 26:609–615. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bergengren L, Kaliff M, Larsson GL,

Karlsson MG and Helenius G: Comparison between professional

sampling and self-sampling for HPV-based cervical cancer screening

among postmenopausal women. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 142:359–364.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kahn JA, Slap GB, Bernstein DI, Kollar LM,

Tissot AM, Hillard PA and Rosenthal SL: Psychological, behavioral,

and interpersonal impact of human papillomavirus and pap test

results. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 14:650–659. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Luszczynska A, Durawa AB, Scholz U and

Knoll N: Empowerment beliefs and intention to uptake cervical

cancer screening: Three psychosocial mediating mechanisms. Women

Health. 52:162–181. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|