Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most commonly

diagnosed malignant disease worldwide (1). Despite surgery, chemotherapy, targeted

therapy and other options, it is estimated that colorectal cancer

ranks as the fourth and fifth most common cause of

cancer-associated death among women and men, respectively, in China

(1). The CRC mortality rate in China

increased annually between 1991 and 2011 (2). By 2012, tobacco smoking, alcohol

consumption, obesity, low levels of physical activity, low fruit

and vegetable intake and high intake of red and processed meat were

responsible for ~46% of CRC cases and associated deaths in China

(3). The development of CRC is a

multistep process that includes the progressive destruction of

epithelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and

survival mechanisms (4).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are single-stranded RNAs of ~20

nucleotides in length that can degrade and inhibit the translation

of target mRNA (5). Some miRNAs

function as CRC inducers or regulators and can be considered as

biomarkers and therapeutic targets (5). miRNAs are regulated at multiple levels,

including transcription, Drosha and Dicer processing, loading onto

Argonaute proteins and miRNA turnover (6). Each level is mediated by multiple

factors, including transcription factors, RNA-binding proteins,

protein-modifying enzymes, RNA-modifying enzymes, exoribonucleases

and endoribonucleases (6). Intronic

miR-32 is located within intron 14 of the transmembrane protein 245

(TMEM245) gene.

We previously found that miR-32 is upregulated in

CRC tissues and that high miR-32 levels are closely associated with

lymph-node and distant metastases (7). Overall, survival rates are low among

patients with CRC that express abundant miR-32 (7). miR-32-overexpression in CRC cells

results in enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion and reduced

apoptosis through the repression of phosphatase and tensin homolog

(PTEN) expression (8). The

mechanisms of miR-32 upregulation in CRC were explored in more

detail and luciferase reporter assays revealed that miR-32 binds to

the 3′-untranslated region of PTEN (8). The promoter region (~2 kb) of

TMEM245/miR-32 was cut into fragments of different

lengths, cloned into the 5′ end of a luciferase reporter vector and

then transfected into CRC cells. The results of the dual-luciferase

reporter assays suggested that the core promoter region is located

within −320 to −1 bp of the 5′-flanking region. Protein binding to

the core promoter was analyzed using DNA pull-down assays and mass

spectrometry. Transcription factor (TF) analyses identified

forkhead box K1 (FOXK1) as a potentially interactive TF (9).

Forkhead box K1 is involved in tumorigenesis and

cancer development. It promotes ovarian cancer cell proliferation

and metastasis (10), esophageal

cancer cell proliferation and migration, inhibits apoptosis and is

associated with poor differentiation and prognosis (11). Wu et al (12) found that FOXK1 induces the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and facilitates CRC cell invasion

in vitro and in vivo, and that enhanced FOXK1

expression indicates a poor prognosis in patients with CRC.

The present study aimed to provide novel insights

into the molecular mechanisms underlying CRC by defining FOXK1

expression in CRC tissues and investigating the relationship

between FOXK1 and miR-32 expression. In addition, the study aimed

to clarify the role of FOXK1 in miR-32 regulation and CRC cell

proliferation and apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

In total, 35 primary CRC and 31 non-cancerous

colonic tissue samples were obtained from 66 patients that had been

treated by surgical resection or colonoscopy at the Affiliated

Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Guangdong, China) between

July 2017 and September 2019. All the patients were Han Chinese.

The mean age of CRC patients was 59±13 years old (range, 28–84

years; 25 males, 10 females). Patients with newly diagnosed CRC and

>18 years old were included. The patients declined

participation, as well as had received either radiotherapy or

chemotherapy before surgery or colonoscopy were excluded. The study

protocol was approved by The Medical Ethics Committee at the

Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University and written

informed consent was obtained from all participants. The diagnoses

of the samples were verified by pathologists who were independent

from the present study. Data on clinicopathological

characteristics, including sex, age, tumor diameter,

differentiation, lymphatic and distant metastasis and staging were

collected. Median FOXK1 expression (0.00492) served as the

cut-off for separating the 35 patients with CRC into groups with

high (n=18) and low (n=17) FOXK1 expression. After

collection tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and

stored at −80°C until use.

Cell transfection

HCT-116 and HT-29 CRC cells were purchased from The

Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of

Sciences. The HT-29 cell line was authenticated by STR profiling.

The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C under a 5% CO2

atmosphere. No antibiotics were used for cell culture. To generate

the FOXK1 expression plasmid, the human FOXK1 coding sequence was

amplified using PCR, as later described. The PCR product was cloned

and inserted into a pcDNA3.1 vector (Promega Corp.). The inserted

fragment was confirmed by sequencing. The FOXK1-overexpressing

plasmid, pcDNA3.1-FOXK1, was synthesized at Guangzhou RiboBio Co.,

Ltd. The pcDNA3.1 empty vector was used as the negative control

(NC) of pcDNA3.1-FOXK1. For plasmid/siRNA/mimic/inhibitor

transfection, cells were seeded at a density of 3×105

cells per well in 6-well plates, or 1×105 cells per well

in 12-well plates, or 5×104 cells per well in 24-well

plates, or 6×103 cells per well in 96-well plates.

Twenty-four hours later, pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 (2.0 µg/ml), pcDNA3.1 (2.0

µg/ml), FOXK1 small interfering (si)RNA (siFOXK1) (150 nM),

siRNA-NC (150 nM), miR-32 mimic (200 nM), mimic-NC (200 nM), miR-32

inhibitor (200 nM) and inhibitor-NC (200 nM) (all RiboBio Co.,

Ltd.) were transfected as described by the manufacturer into

HCT-116 and HT-29 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in Opti-MEM™ I medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cells were harvested 48 h

after transfection for RNA and protein detection, dual-luciferase

reporter assay and apoptosis assay, and 24, 48, 72 and 96 h for

CCK-8 assays, respectively. The siRNA-NC (cat. no. siN0000001-1-5),

mimic-NC (cat. no. miR1N0000001-1-5), inhibitor-NC (cat. no.

miR2N0000001-1-5) were non-targeting and designed and synthesized

by RiboBio Co., Ltd. The following siRNA sequence was used:

siFOXK1, 5′-CCAGTTCACGTCGCTCTAT-3′. The sequences of miR-32 mimic

and inhibitor were as follows: miR-32 mimic, sense:

5′-UAUUGCACAUUACUAAGUUGCA-3′, and antisense:

5′-UGCAACUUAGUAAUGUGCAAUA-3′; mimic-NC, sense:

5′-UUUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′, and antisense:

5′-CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAAA-3′; miR-32, inhibitor:

5′-UGCAACUUAGUAAUGUGCAAUA-3′ and inhibitor-NC:

5′-CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAAA-3′.

Reverse-transcription quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Levels of FOXK1, TMEM245 and miR-32

expression in tissues and transfected cells were measured using

RT-qPCR. Total RNA was extracted from tissues and transfected cells

using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Inc.) that was then reverse

transcribed using PrimeScript™ RT Master mix (Perfect Real Time;

Takara Bio, Inc.) for FOXK1 and TMEM245 and Mir-X™

miRNA First-Strand Synthesis kits (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) for

miR-32 as described by the manufacturers. The endogenous controls

were β-actin mRNA for FOXK1 and TMEM245, and U6

small-nuclear RNA for miR-32. Quantitative PCR was performed using

TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus; Takara

Bio, Inc.) and a LightCycler® 480 II system (Roche

Diagnostics) under a cycling program comprising of 30 sec at 95°C

for 1 cycle, then 5 sec at 95°C and 20 sec at 60°C for a total of

40 cycles. Table I lists the qPCR

primers. The mRQ 3′-primer was included in the Mir-X™ miRNA

First-Strand Synthesis kit, but sequence information of this primer

was unavailable. Relative levels of miR-32 and FOXK1 and

TMEM245 mRNA were determined using the 2−∆∆Cq

method (13).

| Table I.Sequence information for the primers

used in the quantitative PCR assay. |

Table I.

Sequence information for the primers

used in the quantitative PCR assay.

| Gene | Forward primer,

5′-3′ | Reverse primer,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| miR-32 |

CGCGCTATTGCACATTACTAAGTTGC | mRQ 3′ primer |

| U6 |

CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | mRQ 3′ primer |

| FOXK1 |

TTCCAGGAGCCGCACTTCTA |

GGAAGGTACACTGCTTGGGC |

| TMEM245 |

GACATTCTGGACTGGCAGGA |

AGTGGTGAACAGCAGGCTCA |

| PTEN |

AAAGGGACGAACTGGTGTAATG |

TGGTCCTTACTTCCCCATAGAA |

| β-actin |

GGCGGCAACACCATGTACCCT |

AGGGGCCGGACTCGTCATACT |

Western blotting

Cells transfected with

pcDNA3.1-FOXK1/siFOXK1/pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 + miR-32

inhibitor/siFOXK1+miR-32 mimic were incubated at 37°C for 48 h and

then were digested and total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis

buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), and quantified using

BCA protein assay kits (Genstar Technologies Co., Inc.). In total,

30 µg protein was loaded per lane, electrophoresed and separated

using 12% SDS-PAGE and was then transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride membranes (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). Non-specific

protein binding was blocked by incubating the membranes with

skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h, then the membranes were

incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-PTEN (1:1,000; cat. no. 9559S;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-FOXK1 (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab18196; Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (1:1,000; cat. no. AG019; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) antibodies. The membranes were then

incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG

(1:1,000; cat. no. A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) or

horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; cat.

no. A0216; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) secondary antibody

for 1 h at room temperature, washed three times with TBST, then

signals were detected using MilliporeSigma™ Immobilon™ Western

Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). Images

were acquired using an Azure c600 system (Azure Biosystems, Inc.).

Protein bands were quantified using Quantity One software (version

4.6.2; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). All experiments were repeated

at least three times.

Chromatin

immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR)

JASPAR (http://jaspar.genereg.net/) and HOCOMOCO (https://hocomoco11.autosome.ru/) bioinformatics

analysis (performed by Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) was used to

identify the binding sites of FOXK1 to the TMEM245/miR-32

promoter. Two putative FOXK1-binding sites were located within −320

to −1 bp of the TMEM245/miR-32 promoter region at −90 to −77

bp (site one) and −166 to −153 (site two) bp. The ChIP assay was

carried out with the Pierce Agarose ChIP Kit (cat. no. 26156;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were cross-linked with 1% paraformaldehyde and

genomic DNA was digested to an average size of 100–1,000 bp. Total

sheared chromatin was incubated with FOXK1 antibody (5 µg; cat. no.

ab18196; Abcam) or normal rabbit IgG (2 µl; cat. no.2729S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) at 4°C overnight. The NC was

non-specific IgG. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed using qPCR on

a LightCycler® 480 II system. The FOXK1-binding sites

one and two in the TMEM245/miR-32 promoter region were

amplified using the respective primers: Site one,

5′-TTCCCCATTTCCCCTTC-3′ and 5′-CGAGATTGTGGGAGTTGTAG-3′; and site

two, 5′-CCTCCAGGAAGATATAGACCC-3′ and 5′-TCCCGAAGGGGAAATG-3′. The

primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. Target

enrichment was expressed as % input according to the formula: Fold

enrichment=2−∆∆Cq (ChIP/IgG) (14).

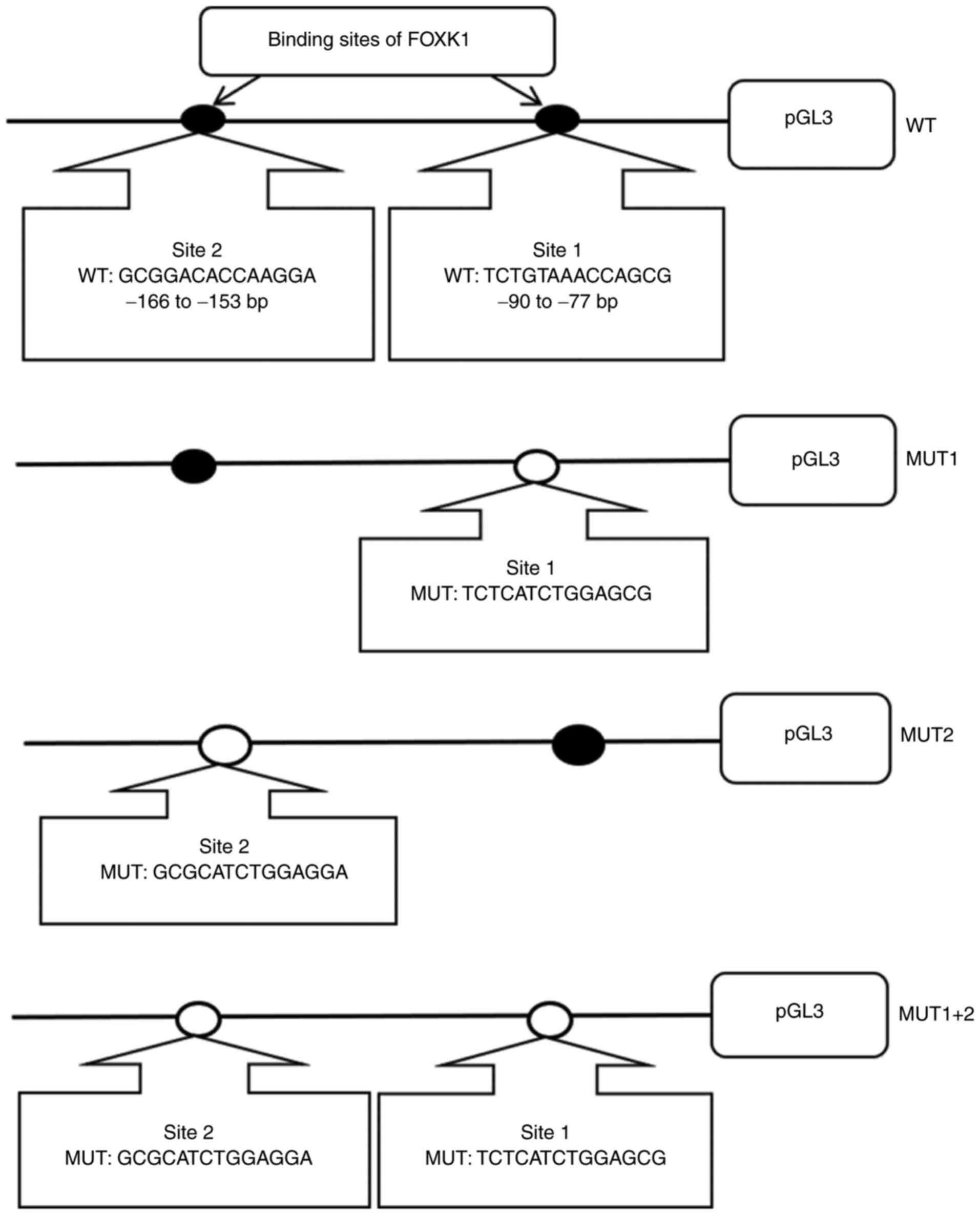

Dual-luciferase reporter assays

HCT-116 cells were cultured in 24-well plates

(5×104 cells per well), and were transfected with

pGL3-basic (Promega Corporation) luciferase reporter constructs

harboring wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) TMEM245/miR-32

promoter target sequences to evaluate the binding potential of

FOXK1 to this promoter. The DNA fragments containing binding sites

one and two were amplified and subcloned into vector pGL3-basic to

create the luciferase pGL3-promoter-WT and the mutated pGL3

reporters: MUT1, MUT2 And MUT1+2, which were mutated at binding

sites one, two or both, respectively (Fig. 1). All WT and MUT plasmids were

synthesized by RiboBio Co, Ltd. The pRL-TK (Promega Corporation)

plasmid was used as an internal control to standardize by Renilla

luciferase activity. Plasmid pGL3-promoter-WT, MUT1, MUT2 or MUT1+2

and pcDNA 3.1-FOXK1 or pcDNA 3.1 vector and pRL-TK were

co-transfected into HCT-116 cells in 24-well plates

(5×104 cells per well) at 37°C for 48 h.

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was used to transfect cells with the plasmids

following the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase activities

were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system

(Promega Corp.). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to that

of Renilla luciferase.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using CCK-8 assays

(Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.). HCT-116 or HT-29 cells

(6×103 cells per well) were seeded into 96-well plates

for 24 h, transfected, then incubated for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. The

cells were incubated with CCK-8 reagent for 1 h at 37°C, then

absorbance at 450 nm was determined by spectrophotometry.

Apoptosis assays

Apoptosis was assayed using Annexin V- FITC

Apoptosis Detection kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.). At

48 h after transfection, CRC cells were digested, resuspended in

Annexin V Binding Solution, mixed with Annexin V-fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide as described by the

manufacturer instructions, and then analyzed by flow cytometry

using a FACScan (BD Biosciences). The ratios (%) of Annexin

V-FITC-positive cells identified by flow cytometry using FACSDiva

software (version 6.1.3; BD Biosciences) represented the apoptotic

population.

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS

v19.0 software (IBM Corp.). Data are presented as means ± standard

deviation. Two groups were compared using unpaired Student's

t-tests. Associations between clinical and pathological features

with FOXK1 expression was analyzed with Fisher's exact test.

Correlations between TMEM245 and miR-32, FOXK1 and

miR-32 and FOXK1 and TMEM245 expression were

determined using Pearson's correlation coefficients. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Expression of FOXK1, TMEM245 and

miR-32 in CRC tissues

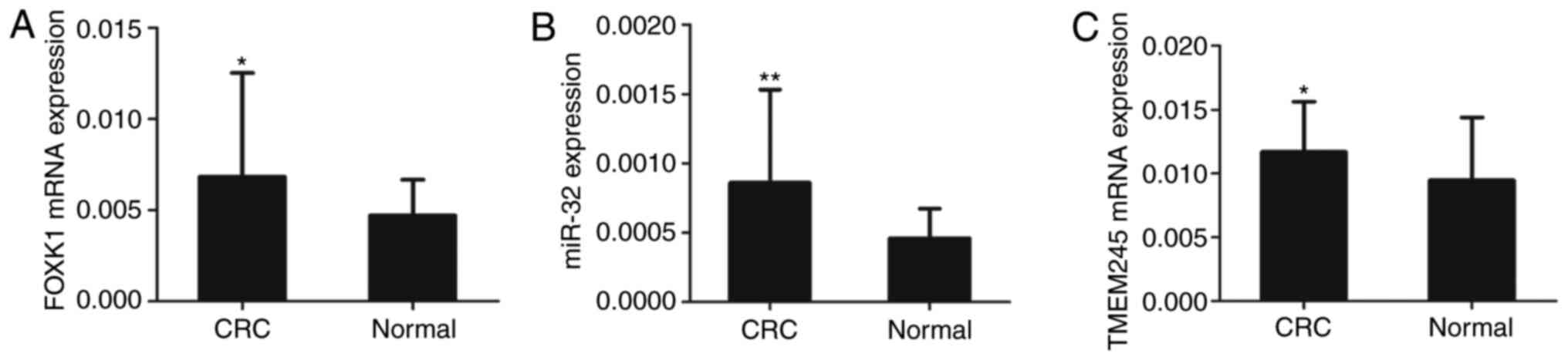

Levels of miR-32, FOXK1 and TMEM245

mRNA expression in CRC and normal colonic tissues were determined

using RT-qPCR. The results showed that the expressions of

FOXK1 (Fig. 2A), miR-32

(Fig. 2B) and TMEM245

(Fig. 2C) were upregulated in CRC

compared with normal tissues (all P<0.05 or P<0.01).

The relationship between increased FOXK1

expression and the clinicopathological features of patients with

CRC was explored. Median FOXK1 expression served as the

cut-off for separating the 35 patients with CRC into groups with

high (n=18) and low (n=17) FOXK1 expression. FOXK1

expression was significantly associated with lymphatic metastasis

and tumor stage (P=0.027 for both; Table II). These results implied a

potential role for FOXK1 in CRC progression.

| Table II.FOXK1 expression and

clinicopathological features of the patients with colorectal

cancer. |

Table II.

FOXK1 expression and

clinicopathological features of the patients with colorectal

cancer.

|

| FOXK1

expression |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathological

features | High, n=18 | Low, n=17 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.315 |

|

<60 | 8 | 11 |

|

|

≥60 | 10 | 6 |

|

| Sex |

|

| 0.471 |

|

Male | 14 | 11 |

|

|

Female | 4 | 6 |

|

| Diameter, cm |

|

| 0.738 |

|

<5 | 9 | 7 |

|

| ≥5 | 9 | 10 |

|

|

Differentiation |

|

| 0.691 |

|

High | 5 | 3 |

|

|

Middle/low | 13 | 14 |

|

| Lymphatic

metastasis |

|

| 0.027a |

|

Positive | 16 | 9 |

|

|

Negative | 2 | 8 |

|

| Distal

metastasis |

|

| >0.999 |

|

Positive | 2 | 2 |

|

|

Negative | 16 | 15 |

|

| Stage |

|

| 0.027a |

|

I–II | 2 | 8 |

|

|

III–IV | 16 | 9 |

|

Correlations between FOXK1, miR-32 and

TMEM245 expression in CRC tissues

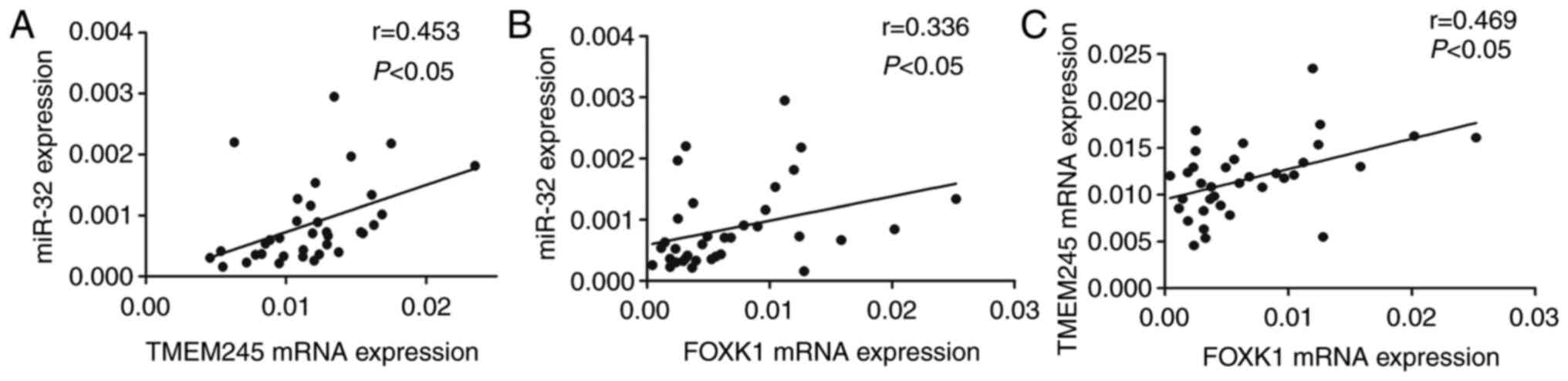

The expression of TMEM245 mRNA and miR-32 was

significantly and positively correlated (r=0.453; P<0.05;

Fig. 3A). Increased FOXK1

mRNA expression was positively correlated with upregulated miR-32

and TMEM245 mRNA (r=0.336 and 0.469, respectively;

P<0.05; Fig. 3B and C). These

results suggest that miR-32 and host gene TMEM245 may be regulated

by FOXK1.

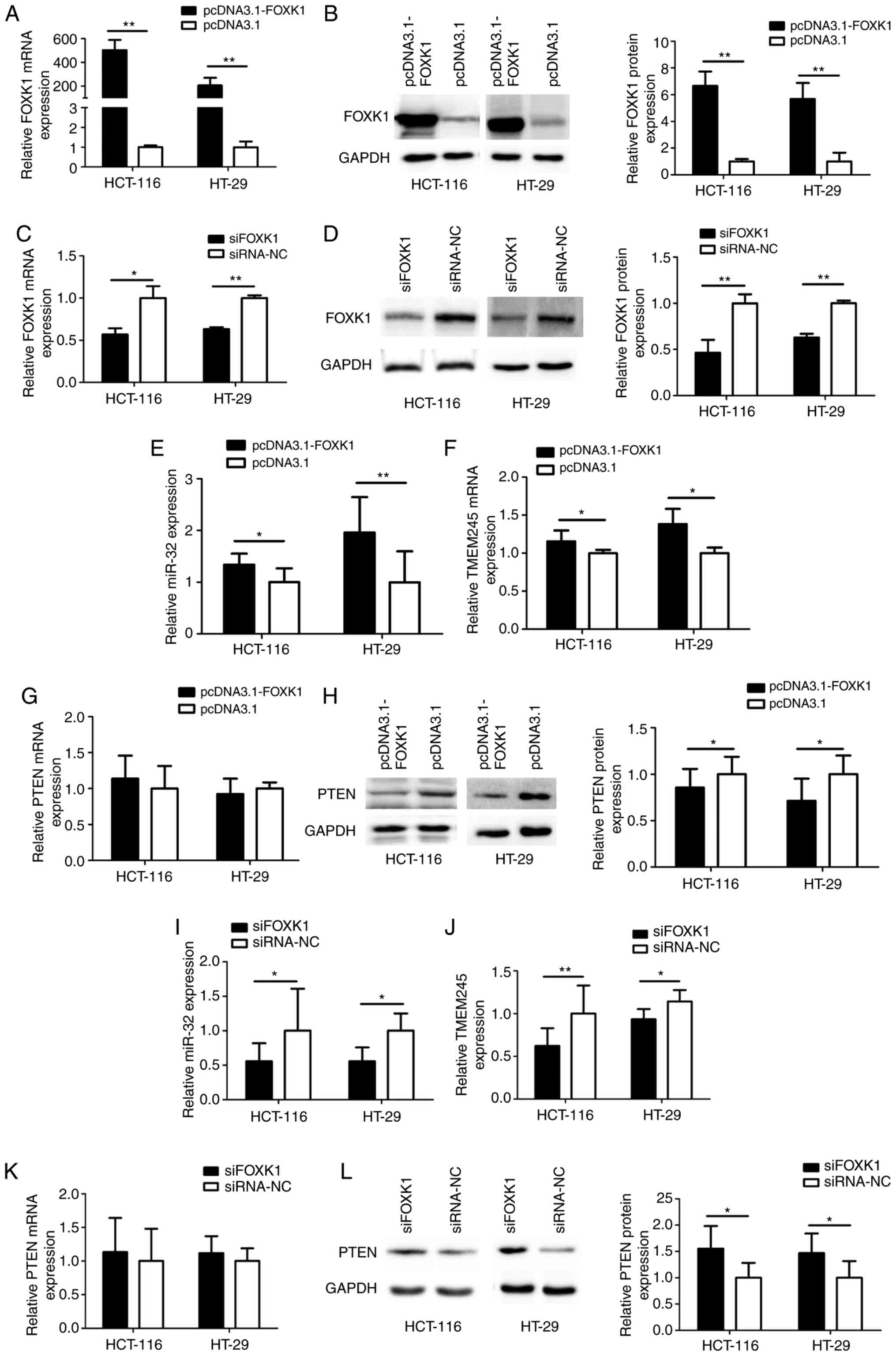

Expression of miR-32, TMEM245 and PTEN

is modulated by FOXK1 in CRC cells

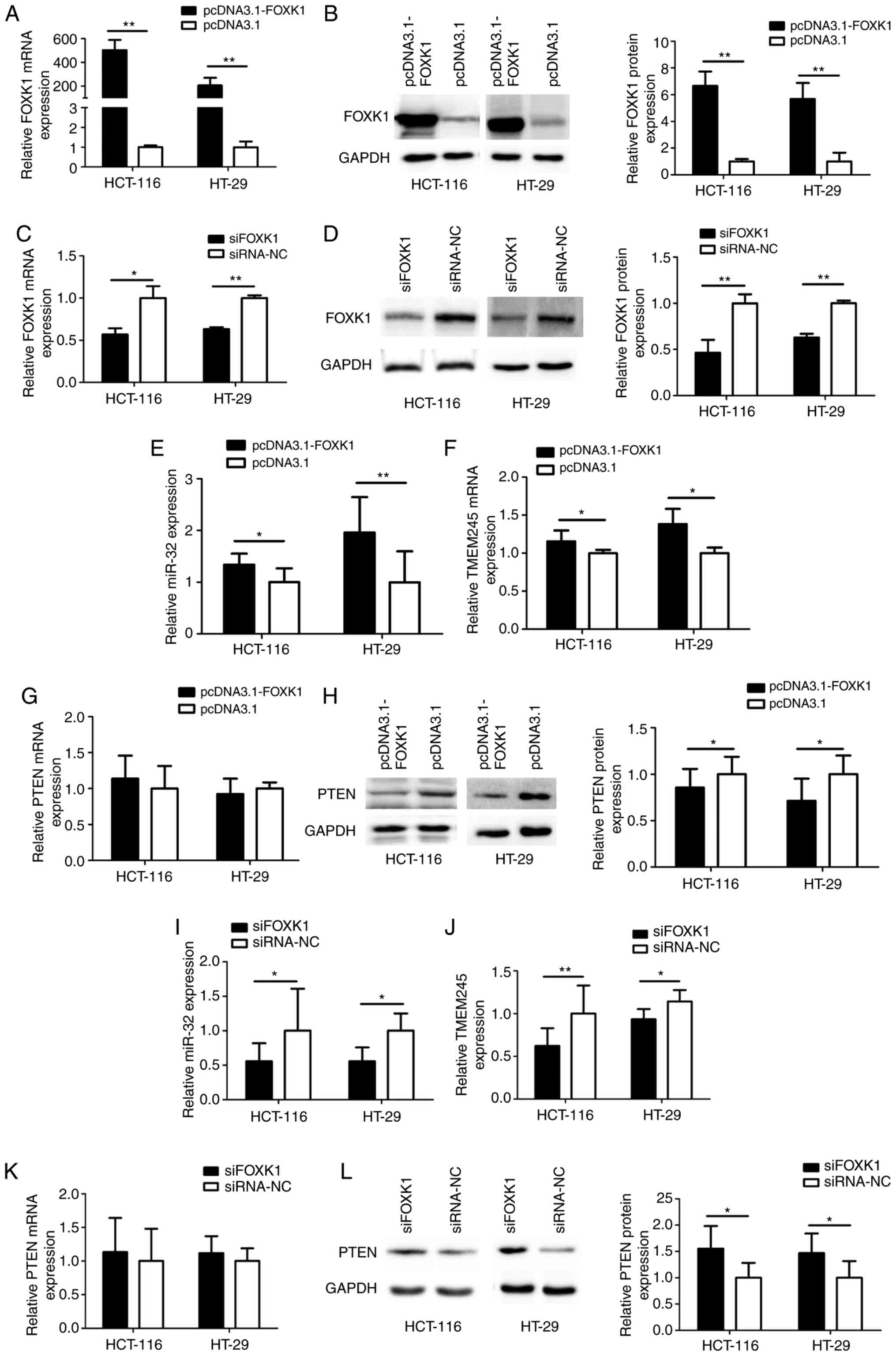

FOXK1 was overexpressed or knocked down in

CRC cells that were respectively transfected with either

pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 or siFOXK1, to determine whether FOXK1 regulated

miR-32, TMEM245 and PTEN expression using RT-qPCR and

western blotting. The level of FOXK1 was significantly increased in

HCT-116 and HT-29 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 compared

with control cells transfected with the empty vector pcDNA3.1

(P<0.01; Fig. 4A and B). The

level of FOXK1 was significantly decreased after FOXK1-knockdown

compared with control cells transfected with siRNA-NC (all

P<0.05 or P<0.01; Fig. 4C and

D). Fig. 4E-H shows that

FOXK1-overexpression significantly increased miR-32 and

TMEM245 mRNA expression and suppressed PTEN protein levels

compared with the control empty vector (all P<0.05 or

P<0.01). In contrast, FOXK1-knockdown resulted in

significantly decreased miR-32 and TMEM245 mRNA and

increased PTEN protein expression compared with siRNA-NC

transfected cells (all P<0.05 or P<0.01; Fig. 4I-L) without significant changes in

PTEN mRNA expression. Taken together, these results

suggested that FOXK1 could enhance miR-32 and TMEM245 expression,

and suppress PTEN protein expression.

| Figure 4.Expressions of miR-32, TMEM245

and PTEN are modulated by FOXK1 in CRC cells. mRNA and

protein expression was detected using reverse-transcription

quantitative PCR and western blotting, respectively. (A) Expression

of FOXK1 mRNA and (B) FOXK1 protein in CRC cells transfected

with pcDNA3.1. (C) Expression of FOXK1 mRNA and (D) FOXK1

protein in CRC cells transfected with siFOXK1. (E-H) Expression of

miR-32, TMEM245 and PTEN in CRC cells transfected with

pcDNA3.1-FOXK1. (I-L) Expression of miR-32, TMEM245 and PTEN

in CRC cells with FOXK1-knockdown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs

corresponding control groups. FOXK1, forkhead box K1; TMEM245,

transmembrane protein 245; miR, microRNA; CRC, colorectal cancer;

NC, negative control; si-, short interfering. |

FOXK1 promotes CRC cell

proliferation

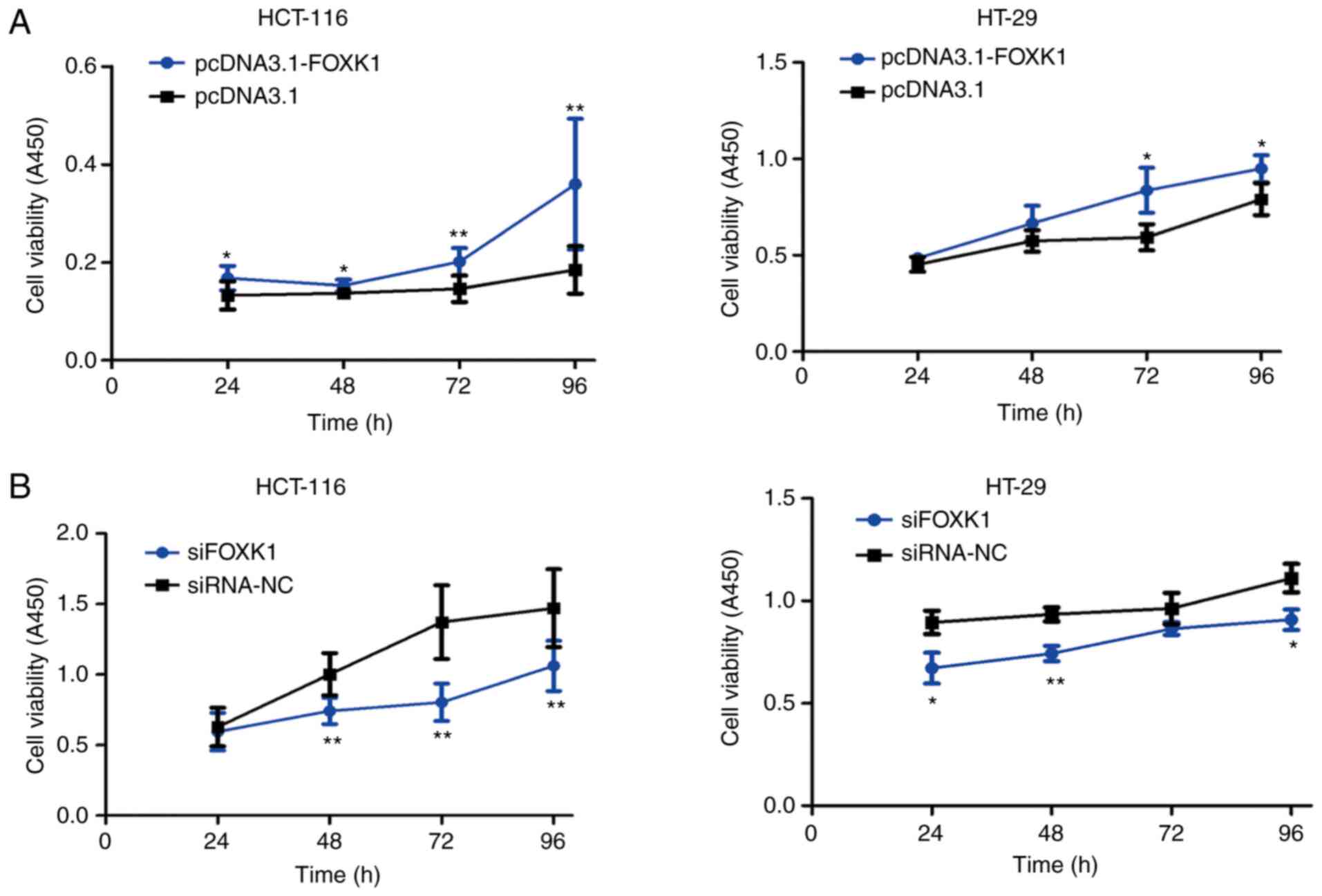

The potential function of FOXK1 in CRC cell

proliferation was investigated using CCK-8 assays. Overexpressed

FOXK1 significantly promoted the proliferation of HCT-116 cells at

24, 48, 72 and 96 h and of HT-29 cells at 72 and 96 h after

transfection (all P<0.05 or P<0.01; Fig. 5A). In contrast, FOXK1

inhibition restricted proliferation of HCT-116 cells at 48, 72 and

96 h and of HT-29 cells at 24, 48 and 96 h after transfection (all

P<0.05 or P<0.01; Fig.

5B).

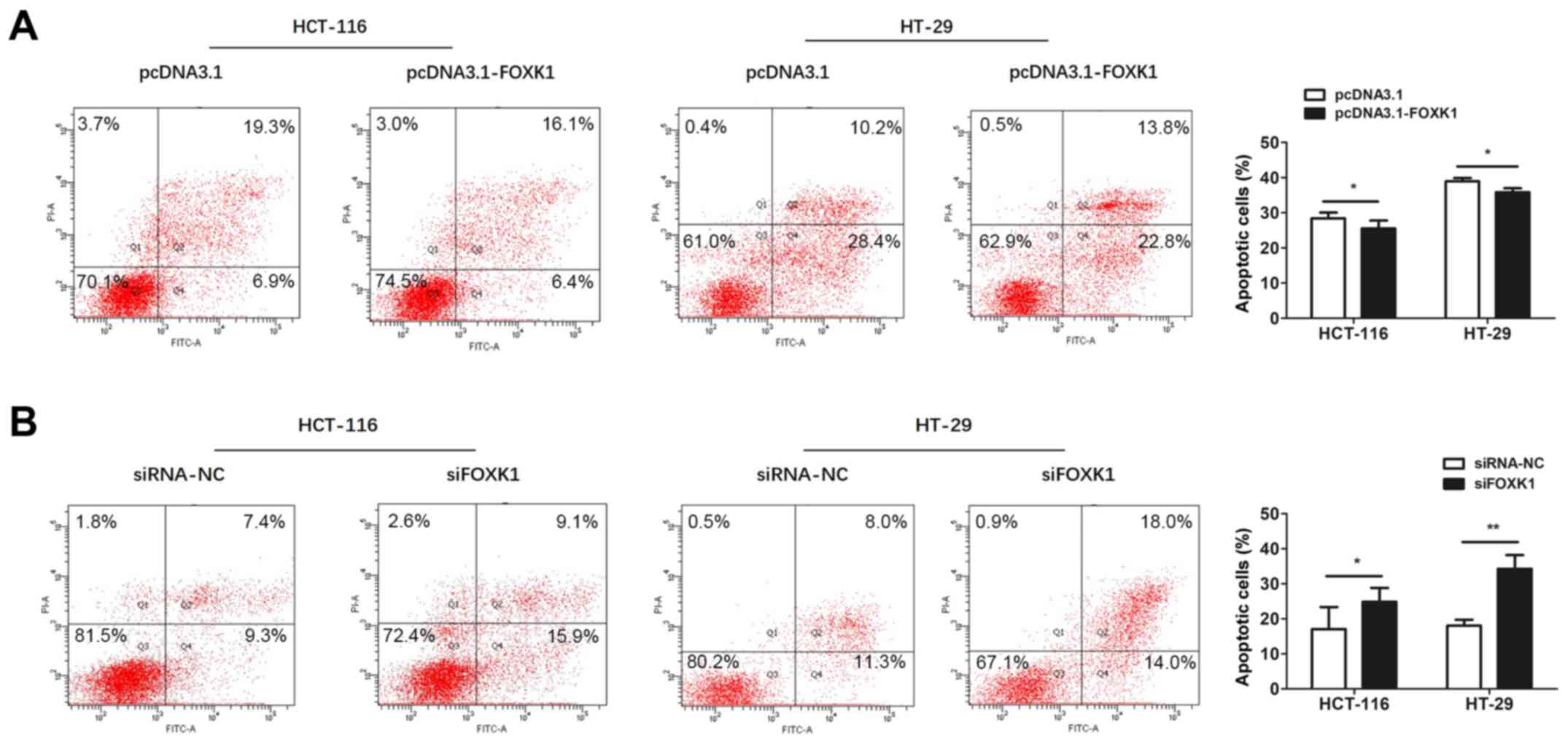

FOXK1 suppresses apoptosis in CRC

cells

Apoptosis was assessed using flow cytometry.

Apoptosis in CRC cells was significantly decreased and increased by

FOXK1-overexpression and knockdown, respectively, compared with

controls (all P<0.05 or P<0.01; Fig. 6). Collectively, these results

suggested that FOXK1 acts as an oncogene in CRC cells.

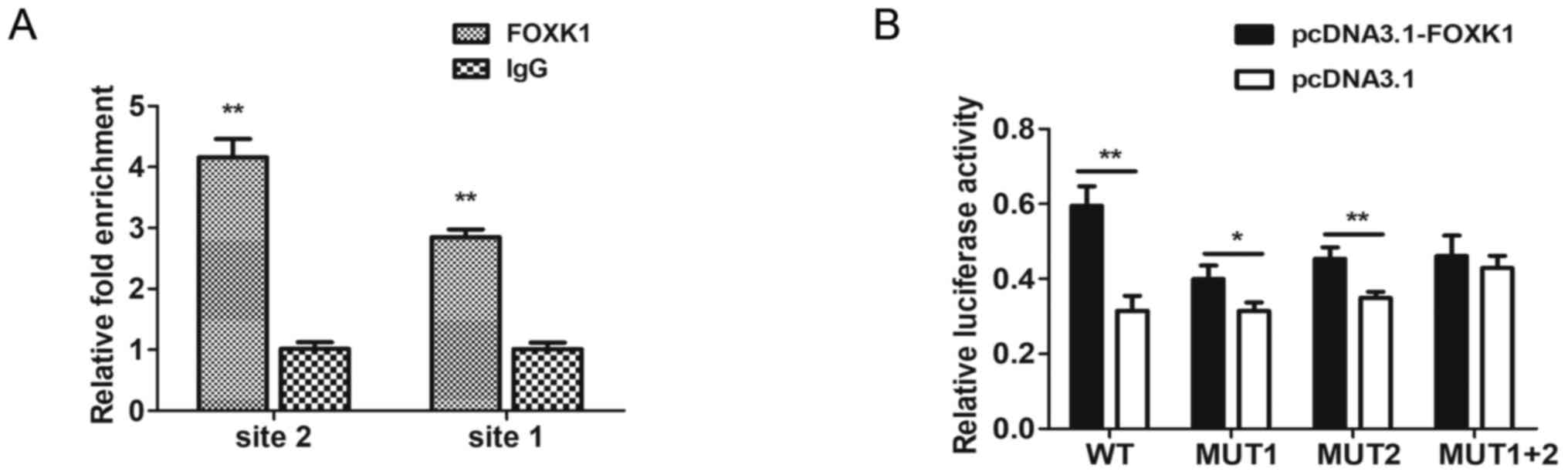

FOXK1 directly binds to the

TMEM245/miR-32 promoter

The findings of the bioinformatics analysis using

JASPAR and HOCOMOCO (RiboBio Co., Ltd.) predicted that FOXK1 could

bind to the core promoter of TMEM245/miR-32. Putative FOXK1-binding

sites one (−90 to −77 bp) and two (−166 to −153 bp) were identified

within the upstream region of the TMEM245/miR-32 gene by

bioinformatics analysis. ChIP-qPCR was used to determine whether

endogenous FOXK1 could directly bind to these sites in CRC cells.

The results revealed that FOXK1 was strongly bound to both sites of

the TMEM245/miR-32 promoter in HCT-116 cells compared with

the IgG control. Fig. 7A shows

substantial enrichment of endogenous FOXK1 at both sites in the

TMEM245/miR-32 promoter, indicating that this promoter was a

direct target of FOXK1.

The relative luciferase activity of

pGL3-promoter-WT, -MUT1 and MUT-2 was significantly increased when

co-transfected with pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 compared with pcDNA3.1 vector

(P<0.05; Fig. 7B). However, there

was no significant difference in relative luciferase activity

between pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 and pcDNA3.1 vector when cotransfected with

pGL3-promoter-MUT1+2 (P>0.05; Fig.

7B). These results indicated that FOXK1 enhanced the

transcriptional activities of the TMEM245/miR-32 promotor

and the involvement of the two binding sites. Collectively, these

data indicated that FOXK1 directly binds to the TMEM245/miR-32

promoter.

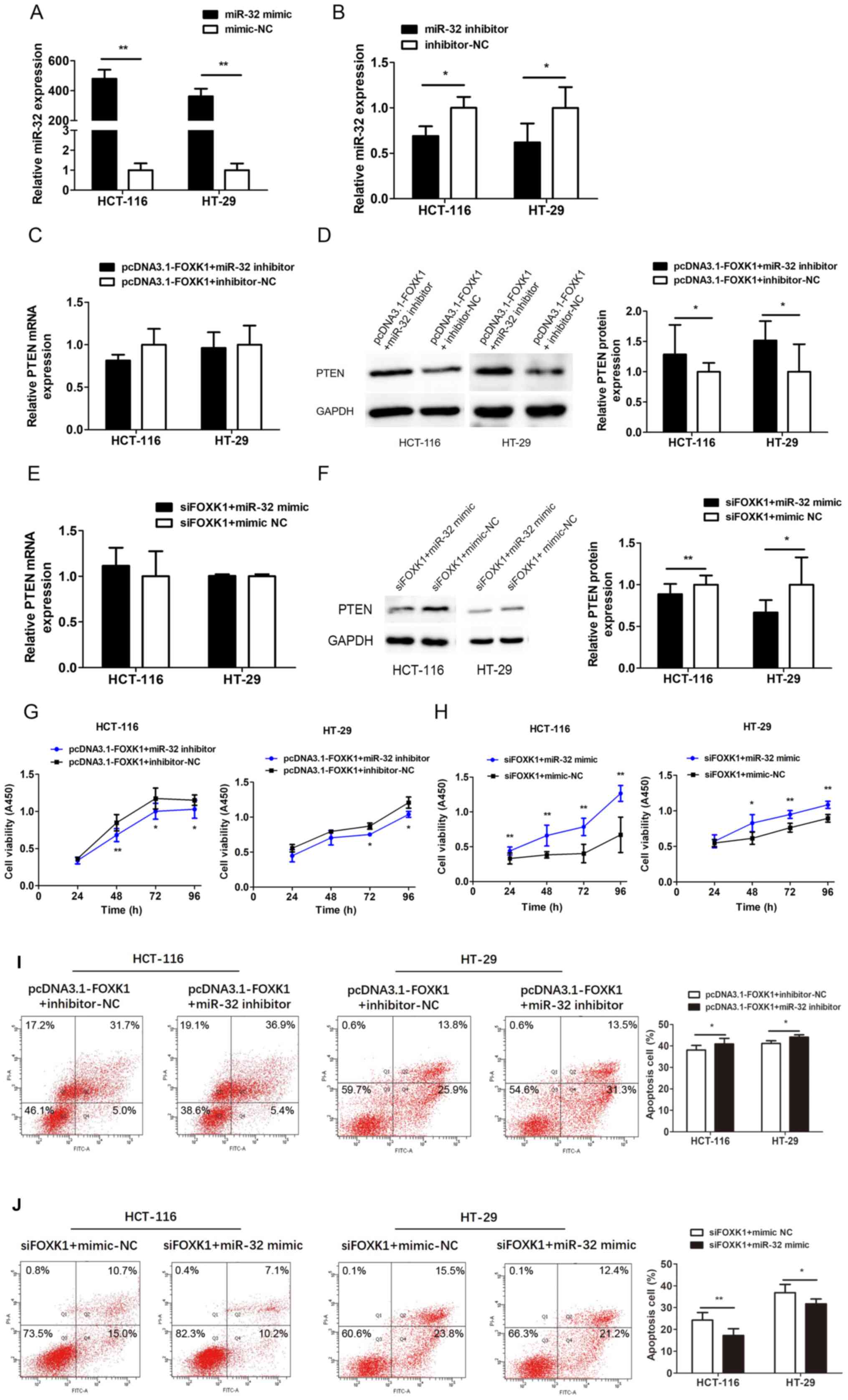

Downregulation of miR-32 reverses the

effects of FOXK1 on PTEN expression and cell proliferation and

apoptosis

miR-32 was explored as a functional target of FOXK1

by co-transfecting HCT-116 and HT-29 cells with pcDNA3.1-FOXK1 and

miR-32 inhibitor, or siFOXK1 and miR-32 mimic. Transfection with

the miR-32 mimic and inhibitor significantly increased and

decreased miR-32 expression, respectively (all P<0.05 or

P<0.01; Fig. 8A and B).

Co-transfection with miR-32 inhibitor partially reversed the

decrease in PTEN expression induced by FOXK1-overexpression

(P<0.05; Fig. 8D), whereas the

miR-32 mimic reversed the PTEN upregulation caused by

FOXK1-knockdown (P<0.05 or P<0.01; Fig. 8F). Levels of PTEN mRNA did not

significantly change (Fig. 8C and

E). Proliferation ability was decreased, whereas apoptosis was

increased after co-transfection with the FOXK1-overexpression

plasmid and miR-32 inhibitor compared with inhibitor-NC (Fig. 8G and I). Proliferation ability was

increased, whereas apoptosis was decreased after co-transfection

with siFOXK1 and miR-32 mimic compared with mimic-NC (Fig. 8H and J). These results indicate that

the promotive effects of FOXK1 on CRC cells are largely mediated by

miR-32 expression and can be reversed by downregulating miR-32.

Discussion

Numerous regulatory mechanisms are involved in the

differential processing of miRNA. Mechanisms that regulate miRNA

expression include transcriptional regulation, such as changes in

host gene expression and hypermethylation of host or miRNA gene

promoters, and post-transcriptional regulation, including changes

in miRNA processing and stability (15). The transcription of miRNA can be

regulated by using TFs that bind to specific promoters (16). For example, the TF p65/NFκB can bind

to the miR-224 promoter and acts as a direct transcriptional

regulator of miR-224 expression, and such binding increases in

cells incubated with lipopolysaccharides, tumor necrosis factor-α

or lymphotoxin-α (17). The myogenic

regulatory factor, MyoD, regulates miR-206 expression by directly

binding to its promoter (18). It

can also directly bind to the miR-182 promoter and upregulate

miR-182 expression (19). The basic

leucine zipper TF, C/EBPβ, binds to the let-7f miRNA promoter and

positively modulates let-7f expression (14). It was determined that FOXK1 was a

potentially interactive TF binding to TMEM245/miR-32

promoter in our previous study (9).

Therefore, the present study aimed to clarify the role of FOXK1 in

miR-32 regulation.

miRNAs are classified as intronic or intergenic

according to their genomic location. Some intronic miRNAs can be

transcribed with their host genes, whereas others are not

co-expressed. The co-transcription of intronic miRNA with host

genes might be regulated by the host gene promoter (20). Baskerville and Bartel (21) showed that intronic miRNAs are closely

associated with their host genes. The upstream regions of pre-miRNA

are considered the promoters for intergenic and intronic miRNA that

are independently transcribed (20).

Lerner et al (22) showed

that the putative tumor suppressor gene, deleted in lymphocytic

leukemia 2 (DLEU2), is the host gene of miR-15a/miR-16-1 and

that Myc binding to two alternative DLEU2 promoters reduces

levels of DLEU2 transcription and mature miR-15a/ −16-1. The

host gene of miR-196b-5p, homeobox protein A10 (HOXA10), is

overexpressed in human gastric cancer tissues, and is positively

correlated with miR-196b-5p expression levels. The expression of

HOXA10 and miR-196b-5p in gastric cancer cells increases

when the HOXA10 promoter is demethylated (23).

Intronic miR-32 is encoded by TMEM245. Levels

of TMEM245 and miR-32 transcripts positively correlate in

prostate tumors (24). The present

study found that TMEM245 mRNA expression was positively

correlated with miR-32 levels in CRC tissues. The evolutionarily

conserved FOX proteins comprise of a TF superfamily that is

characterized by a ‘forkhead’ or ‘winged-helix’ DNA-binding domain,

including FOXK1 and FOXK2 (25). The

vital TF FOXK1 protein regulates numerous biological activities,

including cell cycle progression in myogenic progenitor cells

(26), aerobic glycolysis (27), insulin-like growth factor-1

receptor-mediated signaling involved in cell proliferation and

metabolism (28) and diseases such

as cancer (25). This protein also

plays a crucial role in various cancer types by acting as an

oncogene. Li et al (29)

found that FOXK1 expression is significantly increased in human

hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and cell lines, and that

FOXK1-knockdown significantly suppresses hepatocellular

carcinoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion, in part by

inactivating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Moreover, FOXK1

expression is increased in various malignancies, including CRC,

gastric cancer, glioma and prostate cancer (30–33).

Huang et al (34) reported

that FOXK1 promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, tumor

invasion and metastasis by transactivating cysteine-rich angiogenic

inducer 61 expression in CRC cells.

The present study found that upregulated FOXK1

expression in CRC tissues was positively correlated with miR-32 or

TMEM245 expression. Furthermore, FOXK1 promoted CRC cell

proliferation and reduced apoptosis, thus acting as an oncogene.

However, the proliferation inhibition of siFOXK1 on HT-29 cells at

72 h was not significant, which may be due to the large differences

within the groups. Bioinformatics analysis predicted two binding

sites for FOXK1 in the TMEM245/miR-32 core promotor region.

Gain- and loss-of-function studies revealed that FOXK1 upregulated

the expression of miR-32 and TMEM245 and downregulated PTEN protein

levels. However, there was no significant change in PTEN mRNA

expression. This may be because the main mechanism of

miR-32-induced PTEN suppression is post-transcriptional, which is

consistent with the results in our previous research (8). The binding of FOXK1 to the

TMEM245/miR-32 promoter was identified using ChIP and

dual-luciferase reporter assays. Thus, the present findings

revealed that FOXK1 binds to the TMEM245/miR-32 promotor and

induces miR-32 expression, leading to increased CRC cell

proliferation. In order to determine the mechanism through which

FOXK1 regulates miR-32 functions in cell proliferation and

apoptosis, PTEN expression was assessed and CCK-8 and Annexin

V-FITC apoptosis assays were conducted after simultaneously

interfering with FOXK1 and miR-32 expression. Knockdown of miR-32

in cells overexpressing FOXK1 resulted in decreased cell

proliferation, increased apoptosis and the upregulation of PTEN

protein. Therefore, the promotive effects of FOXK1 on CRC cell

proliferation were mediated, at least in part, by upregulated

miR-32.

However, there were several limitations in the

present study. As a TF, FOXK1 regulates several other genes,

including p21, CCDC43 and Snail (10,35,36).

Moreover, miRNA can be regulated by multiple TFs as well as

non-coding RNAs, such as long non-coding and circular RNA (37,38).

Thus, FOXK1 or miR-32 might affect the onset and development of CRC

via pathways other than the FOXK1-miR-32-PTEN axis. Interactions

between FOXK1 or miR-32 with other genes remain to be clarified.

Animal experiments should be conducted to further evaluate the

mechanisms of FOXK1 in miR-32 regulation.

The findings of the present study suggested that

FOXK1 expression is increased in CRC tissues and positively

correlates with miR-32 levels. FOXK1 was shown to directly bind the

TMEM245/miR-32 promoter to activate miR-32 expression and

downregulate PTEN. Furthermore, miR-32-knockdown mitigated

FOXK1-promoted CRC cell proliferation and FOXK1-inhibited apoptosis

in vitro. Thus, the FOXK1-miR-32-PTEN signaling axis might

play a crucial role in the pathogenesis and development of CRC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by The Natural Science

Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2017A030313546).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Author's contributions

WW designed the study. WW, YC, SY, HY and JY carried

out the experiments. SY collected the samples. WW, YC and JQ

analyzed the data. WW and JQ drafted the manuscript. JQ revised the

manuscript. WW, YC, SY, HY, JY and JQ confirm the authenticity of

all raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Medical Ethics Committees at the Affiliated

Hospital of Guangdong Medical University (Guangdong, China)

approved this study and written informed consent was obtained from

all participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Geng F, Wang Z, Yin H, Yu J and Cao B:

Molecular targeted drugs and treatment of colorectal cancer: Recent

progress and future perspectives. Cancer Biother Radiopharm.

32:149–160. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fang JY, Dong HL, Sang XJ, Xie B, Wu KS,

Du PL, Xu ZX, Jia XY and Lin K: Colorectal cancer mortality

characteristics and predictions in China, 1991–2011. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 16:7991–7995. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gu MJ, Huang QC, Bao CZ, Li YJ, Li XQ, Ye

D, Ye ZH, Chen K and Wang JB: Attributable causes of colorectal

cancer in China. BMC Cancer. 18:382018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sun L, Xue H, Jiang C, Zhou H, Gu L, Liu

Y, Xu C and Xu Q: LncRNA DQ786243 contributes to proliferation and

metastasis of colorectal cancer both in vitro and in vivo. Biosci

Rep. 36:e003282016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Strubberg AM and Madison BB: MicroRNAs in

the etiology of colorectal cancer: Pathways and clinical

implications. Dis Model Mech. 10:197–214. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ha M and Kim VN: Regulation of microRNA

biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15:509–524. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wu W, Yang P, Feng X, Wang H, Qiu Y, Tian

T, He Y, Yu C, Yang J, Ye S and Zhou Y: The relationship between

and clinical signifcance of microRNA-32 and phosphatase and tensin

homologue expression in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes

Cancer. 52:1130–1140. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wu W, Yang J, Feng X, Wang H, Ye S, Yang

P, Tan W, Wei G and Zhou Y: MicroRNA-32 (miR-32) regulates

phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) expression and promotes

growth, migration, and invasion in colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol

Cancer. 12:302013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wu W, Tan W, Ye S, Zhou Y and Quan J:

Analysis of the promoter region of the human miR-32 gene in

colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 17:3743–3750. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li L, Gong M, Zhao Y, Zhao X and Li Q:

FOXK1 facilitates cell proliferation through regulating the

expression of p21, and promotes metastasis in ovarian cancer.

Oncotarget. 8:70441–70451. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen D, Wang K, Li X, Jiang M, Ni L, Xu B,

Chu Y, Wang W, Wang H, Kang H, et al: FOXK1 plays an oncogenic role

in the development of esophageal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 494:88–94. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wu Y, Peng Y, Wu M, Zhang W, Zhang M, Xie

R, Zhang P, Bai Y, Zhao J, Li A, et al: Oncogene FOXK1 enhances

invasion of colorectal carcinoma by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal

transition. Oncotarget. 7:51150–51162. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ayyar K and Reddy KVR: Transcription

factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β upregulates microRNA,

let-7f-1 in human endocervical cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 78:Epub

2017. Sep 16–2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gulyaeva LF and Kushlinskiy NE: Regulatory

mechanisms of microRNA expression. J Transl Med. 14:1432016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Treiber T, Treiber N, Plessmann U,

Harlander S, Daiß JL, Eichner N, Lehmann G, Schall K, Urlaub H and

Meister G: A compendium of RNA-binding proteins that regulate

microRNA biogenesis. Mol Cell. 66:270–284.e13. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Scisciani C, Vossio S, Guerrieri F,

Schinzari V, De Iaco R, D'Onorio de Meo P, Cervello M, Montalto G,

Pollicino T, Raimondo G, et al: Transcriptional regulation of

miR-224 upregulated in human HCCs by NFκB inflammatory pathways. J

Hepatol. 56:855–861. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Koutalianos D, Koutsoulidou A,

Mastroyiannopoulos NP, Furling D and Phylactou LA: MyoD

transcription factor induces myogenesis by inhibiting Twist-1

through miR-206. J Cell Sci. 128:3631–3645. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dodd RD, Sachdeva M, Mito JK, Eward WC,

Brigman BE, Ma Y, Dodd L, Kim Y, Lev D and Kirsch DG: Myogenic

transcription factors regulate pro-metastatic miR-182. Oncogene.

35:1868–1875. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang HM, Kuang S, Xiong X, Gao T, Liu C

and Guo AY: Transcription factor and microRNA co-regulatory loops:

Important regulatory motifs in biological processes and diseases.

Brief Bioinform. 16:45–58. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Baskerville S and Bartel DP: Microarray

profiling of microRNAs reveals frequent coexpression with

neighboring miRNAs and host genes. RNA. 11:241–247. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lerner M, Harada M, Lovén J, Castro J,

Davis Z, Oscier D, Henriksson M, Sangfelt O, Grandér D and Corcoran

MM: DLEU2, frequently deleted in malignancy, functions as a

critical host gene of the cell cycle inhibitory microRNAs miR-15a

and miR-16-1. Exp Cell Re. 315:2941–2952. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shao L, Chen Z, Peng D, Soutto M, Zhu S,

Bates A, Zhang S and El-Rifai W: Methylation of the HOXA10 promoter

directs miR-196b-5p-dependent cell proliferation and invasion of

gastric cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 16:696–706. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ambs S, Prueitt RL, Yi M, Hudson RS, Howe

TM, Petrocca F, Wallace TA, Liu CG, Volinia S, Calin GA, et al:

Genomic profiling of microRNA and messenger RNA reveals deregulated

microRNA expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 68:6162–6170.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu Y, Ding W, Ge H, Ponnusamy M, Wang Q,

Hao X, Wu W, Zhang Y, Yu W, Ao X and Wang J: FOXK transcription

factors: Regulation and critical role in cancer. Cancer Lett.

458:1–12. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shi X and Garry DJ: Sin3 interacts with

Foxk1 and regulates myogenic progenitors. Mol Cell Biochem.

366:251–258. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sukonina V, Ma H, Zhang W, Bartesaghi S,

Subhash S, Heglind M, Foyn H, Betz MJ, Nilsson D, Lidell ME, et al:

FOXK1 and FOXK2 regulate aerobic glycolysis. Nature. 566:279–283.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sakaguchi M, Cai W, Wang CH, Cederquist

CT, Damasio M, Homan EP, Batista T, Ramirez AK, Gupta MK, Steger M,

et al: FoxK1 and FoxK2 in insulin regulation of cellular and

mitochondrial metabolism. Nat Commun. 10:15822019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li P, Yu Z, He L, Zhou D, Xie S, Hou H and

Geng X: Knockdown of FOXK1 inhibited the proliferation, migration

and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biomed

Pharmacother. 92:270–276. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wu M, Wang J, Tang W, Zhan X, Li Y, Peng

Y, Huang X, Bai Y, Zhao J, Li A, et al: FOXK1 interaction with FHL2

promotes proliferation, invasion and metastasis in colorectal

cancer. Oncogenesis. 5:e2712016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang H, Wu X, Xiao Y, Wu L, Peng Y, Tang

W, Liu G, Sun Y, Wang J, Zhu H, et al: Coexpression of FOXK1 and

vimentin promotes EMT, migration, and invasion in gastric cancer

cells. J Mol Med (Berl). 97:163–176. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ji ZG, Jiang HT and Zhang PS: FOXK1

promotes cell growth through activating wnt/β-catenin pathway and

emerges as a novel target of miR-137 in glioma. Am J Transl Res.

10:1784–1792. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chen F, Xiong W, Dou K and Ran Q:

Knockdown of FOXK1 suppresses proliferation, migration, and

invasion in prostate cancer cells. Oncol Res. 25:1261–1267. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Huang X, Xiang L, Li Y, Zhao Y, Zhu H,

Xiao Y, Liu M, Wu X, Wang Z, Jiang P, et al: Snail/FOXK1/Cyr61

signaling axis regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 47:590–603.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang J, Liu G, Liu M, Xiang L, Xiao Y, Zhu

H, Wu X, Peng Y, Zhang W, Jiang P, et al: The FOXK1-CCDC43 axis

promotes the invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells.

Cell Physiol Biochem. 51:2547–2563. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Xu H, Huang S, Zhu X, Zhang W and Zhang X:

FOXK1 promotes glioblastoma proliferation and metastasis through

activation of Snail transcription. Exp Ther Med. 15:3108–3116.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang Z, Li M and Zhang Z: LncRNA MALAT1

modulates oxaliplatin resistance of gastric cancer via sponging

miR-22-3p. Onco Targets Ther. 13:1343–1354. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang L and Ding F: Hsa_circ_0008945

promoted breast cancer progression by targeting miR-338-3p. Onco

Targets Ther. 12:6577–6589. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|