Introduction

Oral cancer is a major public health concern in

India (1). According to the

GLOBOCAN 2020 data, oral and lip cancer accounts for ~177,757

related deaths and 377,713 new cases annually worldwide (2), and for 75,290 related deaths and

135,929 new cases yearly in India. Lip and oral cancer is the most

common malignant neoplasm among males in India (3). The age-standardised incidence of oral

cancer in Trivandrum (also known as Thiruvananthapuram; India)

constitutes 14.5/100,000 males and 5.6/100,000 females (4). At the Regional Cancer Centre in

Trivandrum, lip and oral cancer constitutes 21.7% of registered

male patients with cancer and 6.8% of female patients (5). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the

most common histological type, which develops from the stratified

squamous epithelium of the mucosa. Males are found to be more

commonly affected by SCC than females (6). Tobacco, alcohol consumption and the

habit of chewing betel nut leaves rolled with lime and tobacco

(termed pan), are the common aetiological causes for oral cancer in

India. Other factors include exposure to ultraviolet light, human

papillomavirus infection, orodental factors, dietary deficiencies,

syphilis and chronic candidiasis (6). HPV testing (P-16

immunohistochemistry) is not routinely recommended for oral and lip

tumours as the prevelance of HPV in these sites is said to be low,

unlike for oropharyngeal malignancies where the HPV incidence is

reported to be high.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging

Manual (AJCC) is commonly used to stage oral cancer (7). Early stage lip tumours (AJCC stages I

and II) are treated with single modality treatment, either using

radiotherapy [external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) or brachytherapy]

or surgery. The cure and local control rates are high, irrespective

of treatment with radiotherapy or surgery for early stage lip

carcinoma (8). Locally advanced

tumours (AJCC stages III and IVa) are treated with surgery followed

by adjuvant treatment (9). The

advantage of radiation is an improvement in organ preservation with

a positive cosmetic outcome; thus, radiotherapy is often used as

the single modality treatment. When using brachytherapy, it is

possible to deliver a high localised dose of radiation to the

tumour with rapid dose fall-off when compared to EBRT (10). To date, to the best of our

knowledge, no randomised studies comparing these different

treatment strategies have been reported. In the clinic, the type of

treatment modality is selected based on the size and location of

the tumour, the expected functional outcome and the accessibility

of the treatment type (11). The

aims of the present study were to retrospectively evaluate the

clinical profile and treatment outcomes of patients with SCC of the

lip treated with radical intent at the Regional Cancer Centre.

Patients and methods

Patients and data collection

The present study retrospectively analysed the data

of all patients with biopsy-confirmed carcinoma of the lip treated

with radical radiotherapy (brachytherapy or EBRT) or surgery with

or without adjuvant treatment at the Regional Cancer Centre. Only

patients who were treated with palliative intent were excluded from

the study. A total of 120 patients treated between January 2010 and

December 2016 were eligible for the analysis. The case records of

each of these patients were reviewed and data on patient

demographics, clinical treatment and follow-up details were

captured in a structured proforma. The 7th edition of the American

Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual was used to stage the

patients included in the study (12). The follow-up information was

collected until November 20, 2021, and if information was not

available, the patients were contacted over the telephone and their

status was updated accordingly.

Statistical analysis

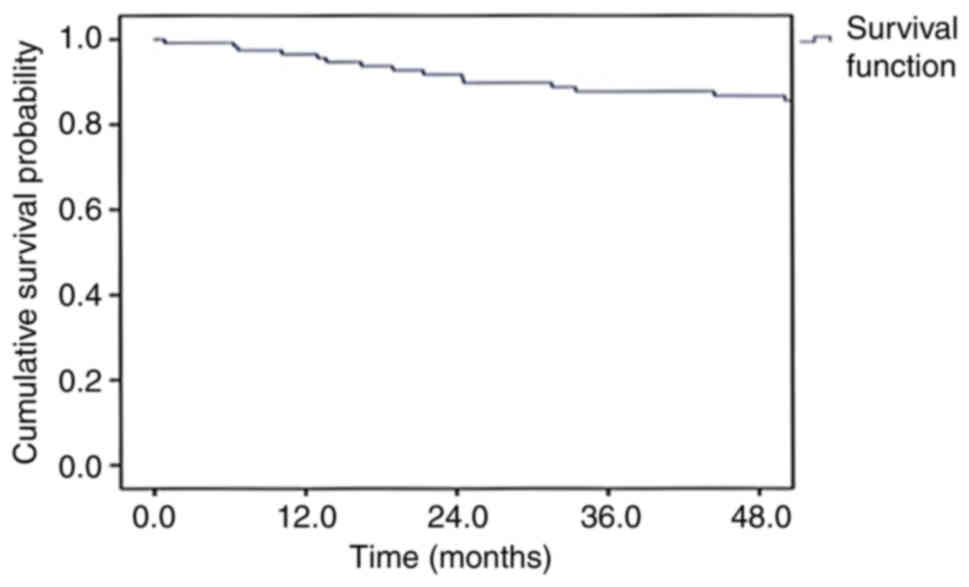

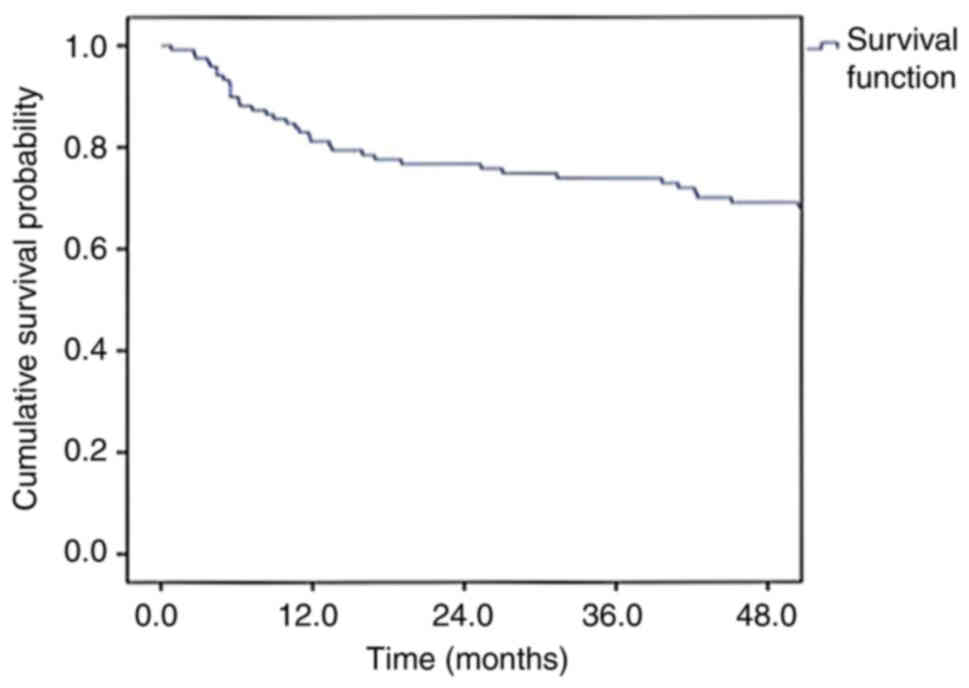

Survival estimates were generated using Kaplan-Meier

analysis using IBM SPSS for windows version 21.0 (13). Disease-free survival (DFS) was

defined as the period from the date of diagnosis to the date of

first documentation of any recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was

defined as the period from the date of diagnosis until death due to

any cause, or the date of the last follow-up. Data of all 120

patients were used for the final analysis. Univariate and

multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to determine

the impact of the patient- and tumour-related factors and treatment

modality on patient outcomes (DFS and OS). Age, sex, performance

status, smoking, alcohol consumption, pan chewing, primary tumour

stage, nodal stage and composite stage were tested for statistical

significance in the univariate and multivariate analyses using the

Cox-proportional hazards regression model. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

All 120 patients with SCC of the lip treated with

radical radiotherapy (brachytherapy or EBRT) or surgery with or

without adjuvant treatment between January 2010 and December 2016

were eligible for analysis. The mean age of the patients included

in the study was 62 years (range, 39–89 years). The majority of

patients (81.6%) were >50 years of age, and males comprised

52.5% of the study population. The stage-wise distribution of

patients was as follows: Stage I, 38 (31.7%); stage II, 26 (21.7%);

stage III, 26 (21.7%); and stage IVa, 30 (25.0%). The baseline

characteristics of these 120 patients are presented in Table I.

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the 120

patients included in the analysis. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the 120

patients included in the analysis.

| Baseline

characteristics | Patients, n (%) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

| ≤50 | 22 (18.3) |

|

>50 | 98 (81.7) |

| Sex |

|

| Male | 63 (52.5) |

|

Female | 57 (47.5) |

| Habits-Alcohol

use |

|

| Yes | 32 (26.7) |

| No | 88 (73.3) |

| Habits-Smoking |

|

| Yes | 28 (23.3) |

| No | 92 (76.7) |

| Habits-Pan

chewing |

|

| Yes | 93 (77.5) |

| No | 27 (22.5) |

| Tumour

stagea |

|

| 1 | 46 (38.3) |

| 2 | 45 (37.5) |

| 3 | 7 (5.8) |

| 4a | 22 (18.3) |

| Nodal

stagea |

|

| 0 | 68 (56.7) |

| 1 | 38 (31.7) |

| 2 | 14 (11.7) |

| Composite

stagea |

|

| I | 38 (31.7) |

| II | 26 (21.7) |

| III | 26 (21.7) |

| Iva | 30 (25.0) |

| Performance

statusb |

|

| 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| 1 | 104 (86.7) |

| 2 | 14 (11.7) |

| Treatment

modality |

|

|

Brachytherapy | 16 (13.3) |

| Surgery

with/without adjuvant treatment | 38 (31.7) |

| Radical

external beam radiotherapy | 66 (55.0) |

Of the 120 patients, 16 patients (13.3%) were

treated with brachytherapy, 38 (31.7%) with surgery with or without

adjuvant treatment and 66 (55.0%) with EBRT. Of the 16 patients

treated with brachytherapy, 15 patients (93.8%) were treated with a

dose schedule of 48 Gy in 12 fractions over a period of 6 days and

1patient (6.7%) was treated using a schedule of 44 Gy in 11

fractions over a period of 6 days. Of the 16 patients treated with

brachytherapy, 2 patients (12.5%) had residual disease at the first

follow-up and the remaining 14 patients (87.5%) went into clinical

remission after treatment. The most commonly used dose schedule for

patients treated with EBRT was 52.50 Gy in 15 fractions over 3

weeks in the majority of patients (75.8%) followed by 60 Gy in 26

fractions over 5 weeks (13.6%). At the Regional Cancer Centre,

accelerated radiotherapy treatment for oral cancer has been

practiced as per the Manchester schedule (52.50 Gy in 15 fractions

over 3 weeks) for several decades since 1980 (14). In total, 5 of the 66 patients

(7.6%) treated with EBRT received induction chemotherapy and 1

patient (1.5%) received concurrent chemotherapy (3 weekly cisplatin

administrations; two cycles) along with radical radiation. The

chemotherapy schedules used as induction therapy were single-agent

methotrexate (3 patients) and cisplatin + 5-flurouracil (2

patients). Of the 66 patients treated with EBRT, 11 patients

(16.7%) had residual disease at the first follow-up.

Of the 38 patients who were treated with surgery, 20

patients (52.6%) underwent wide local excision of the primary

tumour alone, 15 (39.5%) underwent wide excision of the primary

tumour with ipsilateral neck dissection and 3 (7.9%) underwent wide

excision of the primary tumour with bilateral neck dissection.

Bilateral neck dissection was performed in patients with bilateral

enlarged cervical nodes. Out of these 38 patients, 4 patients

(10.5%) with stage III and IVa disease received induction

chemotherapy to decrease the tumour bulk prior to surgery (2

patients received induction chemotherapy with cisplatin +

5-flurouracil and 2 patients received induction chemotherapy with

single-agent methotrexate). A total of 12 patients (31.6%) received

adjuvant radiation following primary surgery. Of these 12 patients,

4 patients (33.3%) had node-positive disease, 2 (16.7%) had T3 and

T4 disease and 2 (16.7%) exhibited perineural spread in the

pathological analysis following surgery. The remaining 4 patients

(33.3%) had received induction chemotherapy for stage III and IVa

disease prior to surgery. All 12 patients completed the planned

standard course of adjuvant radiation using 60 Gy in 30 fractions

over 6 weeks. Only 1 of the 12 patients (8.3%) received adjuvant

concurrent chemo-radiation with 3 weekly cisplatin (2 cycles), as

the patient had extracapsular spread in the nodes.

The median follow-up period was 67.6 months (range,

3.5-128.5 months). The follow-up information available to calculate

5-year survival figures was limited; therefore, 4-year survival

estimates were calculated. With 76% of the follow-up information

available at the time of the analysis, the OS and DFS rates at 4

years for the entire cohort were 86.7 and 69.1%, respectively

(Figs. 1 and 2). The 4-year OS rates of patients with

stage I, II, III and IVa disease were 88.9, 95.2, 86.8 and 75.3%,

respectively, and the DFS rates were 83.6, 69.5, 78.8 and 42.9%,

respectively (Table II).

| Table II.Overall survival and disease-free

survival rates based on the clinical staging and treatment modality

of 120 patients. |

Table II.

Overall survival and disease-free

survival rates based on the clinical staging and treatment modality

of 120 patients.

| Parameter | Patients, n | 4-year overall

survival, % | 4-year disease-free

survival, % |

|---|

| Clinical

stagea |

|

|

|

| I | 38 | 88.9 | 83.6 |

| II | 26 | 95.2 | 69.5 |

|

III | 26 | 86.8 | 78.8 |

|

Iva | 30 | 75.3 | 42.9 |

| Treatment

modality |

|

|

|

|

Brachytherapy | 16 | 92.9 | 68.2 |

| Surgery

with/without adjuvant treatment | 38 | 85.6 | 75.4 |

| Radical

external beam radiotherapy | 66 | 85.4 | 65.8 |

Out of the 120 patients treated, 36 patients (30.0%)

developed a relapse, and the most common site of failure was at the

primary tumour site [in 33 of the 36 (91.7%) patients]. The median

time until relapse was 15.9 months (range, 1–113 months). A total

of 2 patients (5.6%) developed an isolated nodal relapse and 1

patient (2.8%) developed distant metastasis to the bone.

The 4-year OS rates of patients treated with

surgery, EBRT and brachytherapy were 85.6, 85.4 and 92.9%,

respectively, and the 4-year DFS rates of patients treated with

surgery, EBRT and brachytherapy were 75.4, 65.8 and 68.2%,

respectively. Of the 16 patients treated with brachytherapy, 2

patients (12.5%) who had residual disease at the first follow-up

later developed progression of the residual disease and another 3

patients (18.8%) developed disease recurrence during follow-up. All

of these 5 patients had disease at the primary site. In total, 3 of

the 5 patients (60.0%) with disease were later treated with salvage

surgery. There were no nodal relapses reported among the patients

treated with brachytherapy.

Of the 66 patients treated with radical EBRT, 11

patients (16.7%) who had residual disease at the first follow-up

later developed progression of the residual disease and another 13

patients (19.7%) developed disease recurrence during their

follow-up period. All of the aforementioned 24 patients had disease

at the primary site. Out of the 24 patients with disease, only 6

patients (25.0%) underwent salvage surgery later. There were no

nodal relapses reported among the patients treated with radical

EBRT.

Of the 38 patients treated with surgery with or

without adjuvant therapy, 7 patients (18.4%) developed a relapse.

The most common site of relapse following surgery with or without

adjuvant therapy was at the primary site [in 4 of the 7 (57.1%)

patients]. In addition, 2 patients (5.3%) developed an isolated

nodal relapse and 1 patient (2.6%) developed distant metastasis to

the bone. All 3 patients who developed isolated nodal relapse and

bone metastasis had stage IVa disease at presentation.

A total of 22 (18.3%) patients developed a secondary

malignancy during their follow-up period. The most common site for

the development of a secondary malignancy was another subsite in

the oral cavity [in 17 of the 22 (77.3%) patients].

The treatment modality used and the patient- and

tumour-related factors with potential prognostic value with regard

to OS and DFS were recorded and analysed. Primary tumour (P=0.025),

nodal (P=0.005) and composite clinical (P=0.006) stage were found

to significantly affect DFS rates in the univariate analysis

(Tables SI and SII). In the multivariate analysis, only

nodal stage (P=0.005; Table SIII)

was found to be a significant factor affecting DFS rates. The

modality of treatment used was not found to be a determinant of DFS

or OS.

Discussion

Lip cancer is the most common malignancy arising in

the head and neck region, and the majority of cases present at an

early stage (8). Early stage lip

SCC is associated with high cure rates compared with other head and

neck tumours (15). Carcinomas of

the lip can be successfully treated by surgery, EBRT or

brachytherapy alone or in combination. Different combinations of

the aforementioned modalities are used, depending on the stage of

the disease and the histopathological findings. The selection of

treatment modality is based on various factors that include the

resectability of the tumour, disease control probability, the

expected functional and cosmetic outcomes, the patient's preference

and general condition, and the availability of resources and

expertise (9).

When using brachytherapy, it is possible to deliver

a high localised dose of radiation to the tumour with rapid dose

fall-off, without the need for additional planning margins to be

taken into account. This conformity cannot be achieved with any

EBRT technique. A study has reported that brachytherapy, when used

alone, is an appropriate treatment option for patients with early

stage lip tumours (stages T1 and T2-N0) with similar survival and

local control rates as surgery (16). The cosmetic and functional outcomes

reported are good with brachytherapy, with no severe complications

reported thus far (17).

EBRT and surgical treatment with wide local excision

of the primary lesion and negative margins appear to be equally

effective in the treatment of early stage lip cancer (8). The histopathological assessment of

the primary tumour that can predict the biological behaviour of the

tumour and, thereby influence prognosis, is possible following

surgical treatment (18). In

addition, a surgical procedure may cause a functional and/or

cosmetic deficit due to the need to obtain wide margins. By

contrast, radiotherapy has been considered to offer better cosmetic

and functional results compared with surgery (19). A final histological report is also

lacking in patients who receive radiotherapy. Retrospective series

[e.g., Ashley et al (20)]

have reported no differences in local failure and survival rates

between surgery and EBRT. To the best of our knowledge, no

randomised studies comparing these different treatment strategies

have been reported to date. The present study was performed to

analyse the clinical profile and treatment outcomes of patients

with SCC of the lip treated with radical radiotherapy

(brachytherapy or EBRT) or surgery with or without adjuvant

treatment at the Regional Cancer Centre.

With a median follow-up period of 67.6 months, the

DFS and OS rates at 4 years for the entire cohort of 120 patients

were 69.1 and 86.7%, respectively. These survival results are

similar to those of previous studies published in the literature

(21,22). The 4-year OS rates of patients with

stage I, II, III and IVa disease were 88.9, 95.2, 86.8 and 75.3%,

respectively, and the DFS rates were 83.6, 69.5, 78.8 and 42.9%,

respectively. These results suggest that the cure rate for lip

cancer is high, especially when treated at the early stages.

The 4-year OS rates of patients treated with

surgery, EBRT and brachytherapy were 85.6, 85.4 and 92.9%,

respectively, and the 4-year DFS rates of the patients treated with

surgery, EBRT and brachytherapy were 75.4, 65.8 and 68.2%,

respectively. These results suggest that the cure rates of patients

with early stages of carcinoma of the lip are favourable, whether

they were treated with EBRT, brachytherapy or surgery. The 5-year

survival rate of patients with lip cancer treated with high

dose-rate brachytherapy using moulds was 68.8% in the study by

Unetsubo et al (23). This

survival value is comparable to those of the present study.

In the present study, 30% of patients developed

recurrence following treatment and the majority had local

recurrence only. In the literature, the recurrence rates following

treatment range from 15 to 30% (21), and the most common sites of

recurrence reported are local recurrences (24), similar to those observed in the

present study. The number of patients undergoing salvage surgery

for recurrences following radiotherapy was low in the present

study.

The retrospective study published by Ben Arie et

al (25) reported the rates of

secondary malignancy to be ~17% in patients with head and neck

cancer, which is comparable to the findings of the present study.

Han et al (26) reported

that the primary tumour and nodal stages were considered as

determinants of survival for lip SCC, which is also similar to the

results observed in the present study. The composite clinical stage

is another important prognostic factor associated with survival

(15), as was also observed in the

present study.

There are only a few studies available to date that

have focussed on the treatment outcomes of patients with lip

cancer. The present retrospective study on the outcomes of patients

with SCC of the lip treated with radical intent highlights the fact

that high cure rates can be obtained for lip cancer when treatment

is administered at the early stages. The cure and local control

rates reported in the present study were high, irrespective of

whether patients were treated with radiotherapy or surgery for

early stage SCC of the lip, as was also reported in the study by

Gooris et al (27).

The main limitation of the present study was the

bias associated with a retrospective study design. Data on the

exact site of the tumour (whether it was a tumour of the upper or

lower lip) and late morbidity data could not be obtained in the

present study. In addition, a number of patients were lost to

follow-up, and the follow-up information of only 76% of patients

could be obtained for estimating the 4-year OS and DFS times, and

rates at the time of analysis.

In conclusion, in the present retrospective study on

120 patients with carcinoma of the lip treated with radical

radiotherapy (brachytherapy or EBRT) or surgery with or without

adjuvant treatment, the 4-year DFS and OS rates were 69.1 and

86.7%, respectively. The findings of the present study indicate

that the outcomes of patients with carcinoma of the lip are

favourable when treatment is administered at the early stages. The

salvage rates were poor following relapse after radiotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

GB performed the literature search, designed the

study, collected and analysed the data, wrote the manuscript,

prepared the tables and edited the manuscript. RR was involved in

the design of the study and assisted with data collection and

analysis. MR assisted with data collection, the preparation of the

tables and in the editing of the manuscript. LMN assisted with the

intepretation of the data, updating the patient follow-up

information, and in the drafting of the manuscript and preparing

tables. FN assisted with the analysis of the data and in the

writing of the discussion. ST assisted with the study design and in

the overall preparation of the manuscript. PSG assisted with the

statistical analysis, and in the preparation of the figures and

tables. CTK performed the literature search, designed the study and

assisted with the writing and editing of the manuscript. GB and CTK

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of the Regional Cancer Centre (Thiruvananthapuram, India) and

no separate ethics committee approval was obtained, as this is a

retrospective analysis and all data that were analysed were

collected as part of routine diagnosis and treatment. Patients were

diagnosed and treated according to standard treatment guidelines;

the study does not report the use of experimental or new

protocols.

Patient consent for publication

Patient consent for the standard treatment had been

taken prior to commencing treatment. No separate consent was taken

for publication, as this is a retrospective analysis and all data

that were analysed were collected as part of routine diagnosis and

treatment. Patients were diagnosed and treated according to

standard treatment guidelines.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Laprise C, Shahul HP, Madathil SA,

Thekkepurakkal AS, Castonguay G, Varghese I, Shiraz S, Allison P,

Schlecht NF, Rousseau MC, et al: Periodontal diseases and risk of

oral cancer in Southern India: Results from the HeNCe Life study.

Int J Cancer. 139:1512–1519. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC), . India: Source: Globocan 2020. IARC; Lyon: 2020,

https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/356-india-fact-sheets.pdfFebruary

17–2022

|

|

4

|

Mathew A, Sara George P, MC K, G P, KM JK

and Sebastian P: Cancer incidence and mortality: District cancer

registry, Trivandrum, South India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

18:1485–1491. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Regional Cancer Centre (RCC), . Over Three

Decades of Changing Lives. RCC; Thiruvananthapuram: 2022,

https://www.rcctvm.gov.in/pdf/annualreports/RCC%20AR%202018-19.pdfFebruary

17–2022

|

|

6

|

Ram H, Sarkar J, Kumar H, Konwar R, Bhatt

ML and Mohammad S: Oral cancer: Risk factors and molecular

pathogenesis. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 10:132–137. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC,

Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR and

Winchester DP: The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual:

Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more

‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin.

67:93–99. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

de Visscher JG, Botke G, Schakenraad JA

and van der Waal I: A comparison of results after radiotherapy and

surgery for stage I squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Head

Neck. 21:526–530. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huang SH and O´Sullivan B: Oral cancer:

Current role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Med Oral Patol Oral

Cir Bucal. 18:e233–e240. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chargari C, Deutsch E, Blanchard P, Gouy

S, Martelli H, Guérin F, Dumas I, Bossi A, Morice P, Viswanathan AN

and Haie-Meder C: Brachytherapy: An overview for clinicians. CA

Cancer J Clin. 69:386–401. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

El Ayachy R, Sun R, Ka K, Laville A,

Duhamel AS, Tailleur A, Dumas I, Bockel S, Espenel S, Blanchard P,

et al: Pulsed dose rate brachytherapy of lip carcinoma: Clinical

outcome and quality of life analysis. Cancers (Basel). 13:13872021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Edge SB and Compton CC: The American Joint

Committee on Cancer: The 7th Edition of the AJCC cancer staging

manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 17:1471–1474. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Goel MK, Khanna P and Kishore J:

Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J

Ayurveda Res. 1:274–278. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nair MK, Sankaranarayanan R, Padmanabhan

TK and Madhu CS: Oral verrucous carcinoma: Treatment with

radiotherapy. Cancer. 61:458–461. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Biasoli ÉR, Valente VB, Mantovan B,

Collado FU, Neto SC, Sundefeld ML, Miyahara GI and Bernabé DG: Lip

Cancer: A clinicopathological study and treatment outcomes in a

25-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 74:1360–1367. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ayerra AQ, Mena EP, Fabregas JP, Miguelez

CG and Guedea F: HDR and LDR Brachytherapy in the treatment of lip

cancer: The experience of the catalan institute of oncology. J

Contemp Brachytherapy. 2:9–13. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guibert M, David I, Vergez S, Rives M,

Filleron T, Bonnet J and Delannes M: Brachytherapy in lip

carcinoma: Long-term results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

81:e839–e843. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Stein AL and Tahan SR: Histologic

correlates of metastasis in primary invasive squamous cell

carcinoma of the lip. J Cutan Pathol. 21:16–21. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Stranc MF, Fogel M and Dische S:

Comparison of lip function: Surgery vs radiotherapy. Br J Plast

Surg. 40:598–604. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ashley FL, McConnell DV, Machida R,

Sterling HE, Galloway D and Grazer F: Carcinoma of the lip. A

comparison of five year results after irradiation and surgical

therapy. Am J Surg. 110:549–551. 1965. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zitsch RP III, Park CW, Renner GJ and Rea

JL: Outcome analysis for lip carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

113:589–596. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Listl S, Jansen L, Stenzinger A, Freier K,

Emrich K, Holleczek B, Katalinic A, Gondos A and Brenner H; GEKID

Cancer Survival Working Group, : Survival of patients with oral

cavity cancer in Germany. PLoS One. 8:e534152013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Unetsubo T, Matsuzaki H, Takemoto M,

Katsui K, Hara M, Katayama N, Waki T, Kanazawa S and Asaumi J:

High-dose-rate brachytherapy using molds for lip and oral cavity

tumors. Radiat Oncol. 10:812015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Heller KS and Shah JP: Carcinoma of the

lip. Am J Surg. 138:600–603. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ben Arie G, Shafat T, Belochitski O,

El-Saied S and Joshua BZ: Treatment modality and second primary

tumors of the head and neck. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec.

83:420–427. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Han AY, Kuan EC, Mallen-St Clair J, Alonso

JE, Arshi A and St John MA: Epidemiology of squamous cell carcinoma

of the lip in the United States: A population-based cohort

analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 142:1216–1223. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gooris PJ, Maat B, Vermey A, Roukema JA

and Roodenburg JL: Radiotherapy for cancer of the lip. A long-term

evaluation of 85 treated cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol Endod. 86:325–330. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

OncologyPRO, . Performance Scales:

Karnofsky & ECOG Scores. ESMO; Lugano: 2022, https://oncologypro.esmo.org/oncology-in-practice/practice-tools/performance-scalesOctober

31–2022

|