Introduction

Preoperative neoadjuvant long-course

chemoradiotherapy (LC-CRT) is the current standard of therapy for

locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) with the lower edge of the

tumor <10-cm from the anal verge (1). Since neoadjuvant short-course

radiotherapy (SCRT) can achieve similar survival outcomes without

significantly increasing toxicities compared with LC-CRT it can be

used as an alternative option (2,3).

Numerous studies have confirmed the synergistic effects between

radiotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (4,5).

Radiotherapy can increase exposure to tumor antigens, alter the

tumor microenvironment and promote the recruitment of inflammatory

factors (6–8), and ICIs can simultaneously strengthen

the ablility of the immune response of the patient against tumors.

Based on these theories and studies, the present study conducted a

phase 2 clinical trial of preoperative SCR followed by chemotherapy

and camrelizumab as a treatment regimen for LARC, which showed a

measurable increase in the pathological complete response (pCR)

rate (48.1%; 13/27) (9). A phase 3

randomized controlled clinical trial is underway and the current

results are concordant with the phase 2 results, showing a

significant increase in pCR rate compared with preoperative

neoadjuvant LC-CRT.

In rectal cancer, a number of patients may opt for

watchful waiting treatment due to the presence of special situation

of complete clinical remission (CCR). However, the dilemma is that

there is no uniform definition of CCR. Moreover, there is

controversy on watchful waiting as a treatment method (10). A prospective study has demonstrated

that imaging is not a sensitive predictor of pCR in patients with

rectal cancer. The accuracy of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission

tomography and computed tomography (CT) in predicting pCR is only

54 and 19%, respectively (11).

This is also a hindrance when choosing treatment options (surgery

or observation) in clinical practice. Therefore, early and correct

identification of patients with pCR and avoiding them to have the

operation is one of the urgent clinical issues to be addressed.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that economical

and widely available hematological indicators are often used to

predict the prognosis of patients with cancer (12–14).

For example, in patients with rectal cancer treated with

neoadjuvant CRT, Huang et al (15) suggested that a higher neutrophil to

lymphocyte ratio (NLR) pretreatment is associated with poorer

prognosis, and that these patients not only have a higher risk of

recurrence, but also have worse overall survival (OS) and

disease-free survival (DFS). Even in patients with LARC treated

with SCRT, high levels of NLR are independently associated with

poor OS (16). Similarly, the

platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is negatively associated with

prognosis in patients with rectal cancer (17). In addition to these inflammatory

indicators, there are a number of peripheral blood indicators that

also reflect the prognosis of patients with cancer. For example,

elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at baseline serves as a poor

prognostic biomarker in advanced non-small cell lung cancer

(18). A meta-analysis of 76

studies indicated that LDH is a predictive biomarker of prognosis

in a variety of solid tumors (19).

In metastatic colorectal cancer, patients with high LDH also have a

poor prognosis (20). Notably, to

the best of our knowledge, studies of LDH in the neoadjuvant

treatment of LARC are rare.

The above findings suggest that baseline peripheral

blood indicators, including NLR, PLR and LDH, can be used as

predictors of prognosis in patients with cancer. Therefore, the aim

of the present study was to investigate whether these indicators

could predict the pathological response of patients with LARC

treated with SCR followed by chemotherapy and camrelizumab, while

also searching for hematological markers at baseline that may

potentially play a predictive role.

Patients and materials

Patients

Eligible patients at Cancer Center, Union Hospital,

Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and

Technology (Wuhan, China) were enrolled in the present

retrospective study between June, 2021 and October, 2022. The

percentages of females were 35.2, 31.0 and 31.4% and the mean age

were 56.91, 53.69 and 56.98 years in Arm A, Arm b and Arm C,

respectively. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics

Committee of the Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of

Science and Technology (approval no. 0271-21). The inclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Patients or their family members agree

to participate in the study and sign the informed consent form; ii)

aged 18–75 years, male or female; iii) histologically confirmed

T3-44 and/or N+ rectal adenocarcinoma (AJCC/UICC TNM staging (8th

Edition, 2017) (21); iv) inferior

margin ≤10 cm from the anal verge; v) it is expected to reach R0;

vi) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score is

0–1; vii) can swallow pills normally; viii) untreated with

antitumor therapy for rectal cancer, including radiotherapy,

chemotherapy, surgery and traditional Chinese medicine; ix)

surgical treatment is planned after neoadjuvant treatment; x) there

was no operative contraindication; xi) laboratory tests were

required to meet the following requirements: White blood cells

≥4×109/l; absolute neutrophil count

≥1.5×109/l; platelet count ≥100×109/l;

hemoglobin ≥90 g/l; serum total bilirubin ≤1.5× upper limit of

normal (ULN); serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate

aminotransferase ≤2.5× ULN; serum creatinine ≤1.5× ULN value or

creatinine clearance rate ≥50 ml/min; international normalized

ratio ≤1.5× ULN; activated partial thromboplastin time ≤1.5× ULN;

and xii) males or females with reproductive ability who are willing

to use contraception in the trial. The exclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Documented history of allergy to study drugs, including

any component of Camrelizumab, capecitabine, irinotecan,

oxaliplatin and other platinum drugs; ii) have received or are

receiving any of the following treatments: Any radiotherapy,

chemotherapy or other anti-tumor drugs for tumors; patients who

need to be treated with corticosteroid (dose equivalent to

prednisone of >10 mg/day) or other immunosuppressive agents

within 2 weeks prior to study drug administration; received live

attenuated vaccine within 4 weeks before the first use of the study

drug; underwent major surgery or severe trauma within 4 weeks

before the first use of the study drug; iii) any active autoimmune

disease or history of autoimmune disease; iv) have a history of

immunodeficiency, including HIV positive, or other acquired or

congenital immunodeficiency diseases, or have a history of organ

transplantation or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation; v) there

are clinical symptoms or diseases of heart that are not well

controlled; vi) severe infection (CTCAE >2) occurred within 4

weeks before the first use of the study drug; baseline chest

imaging revealed active pulmonary inflammation, signs and symptoms

of infection within 14 days prior to the first use of the study

drug or oral or patient is taking intravenous antibiotic therapy,

except for prophylactic use of antibiotics; vii) patients with

active pulmonary tuberculosis infection found by medical history or

CT examination, or with a history of active pulmonary tuberculosis

infection within one year before enrollment, or with a history of

active pulmonary tuberculosis infection >1 year ago but without

regular treatment; viii) the presence of active hepatitis B (HBV

DNA >2,000 IU/ml or 104 copies/ml) was positive for

hepatitis C (hepatitis C antibody) and HCV RNA was higher compared

with the lower limit of analytical method; ix) female subject who

is pregnant or breastfeeding; x) patients who are not suitable for

participation in clinical trials in the opinion of the

investigator. View inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria using

the following link: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04928807?term=NCT04928807&draw=2&rank=1.

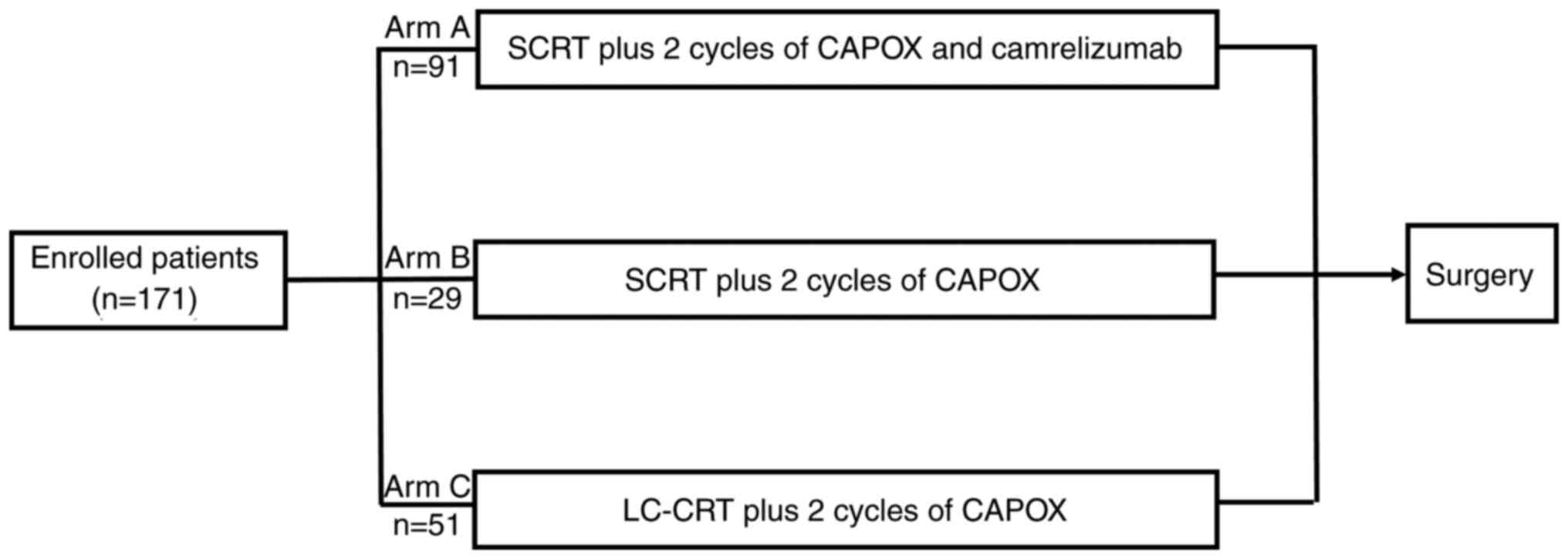

Eligible patients were divided into 3 cohorts

depending on the neoadjuvant treatment regimen: Arm A (SCRT plus 2

cycles of chemotherapy and camrelizumab); Arm B (SCRT plus 2 cycles

of chemotherapy); and Arm C (LC-CRT plus 2 cycles of chemotherapy).

The more detailed treatment regimen was presented in Fig. 1. Albumin, total cholesterol, LDH,

neutrophil, platelet and lymphocyte values in the peripheral blood

were collected before treatment. pCR was defined as postoperative

pathologic confirmation of no active cancer cells remaining in

either the primary site or the resected regional lymph nodes with a

ypT0N0M0 stage.

| Figure 1.Treatment regimen. CAPOX course,

oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 intravenously, day 1; capecitabine

1,000 mg/m2 oral twice daily, days 1–14. Camrelizumab,

200 mg intravenous drip, day 1. LC-CRT course, 28×1.8 Gy on 5 days

per week, oral capecitabine (825 mg/m2, bid, days 1–5)

during radiotherapy. Surgery was performed according to total

mesorectal excision principles. CAPOX, capecitabine plus

oxaliplatin; SCRT, short-course radiotherapy; LC-CRT, long-course

chemoradiotherapy; SCRT, 5×5 Gy over 5 days. |

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described by mean ±

standard deviation (SD) or median and range (determined by whether

the data are normally distributed according to Shapiro-wilk test),

and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and

percentages. The non-parametric test, χ2 and Fisher's

exact tests were performed to compare the three groups. The

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to determine

the optimal cut-off value to define the level of hematological

indicators and univariate and multivariate logistics regressions

were used to determine independent prognostic factors of pCR among

these indicators. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. All data analysis was

performed in IBM SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp.).

Results

Patient clinical features

The basic clinical characteristics of the three

cohorts of patients are presented in Table I. The mean ages of Arm A, Arm B and

Arm C were 56.91, 53.69 and 56.98 years old, respectively. The

percentages of males in Arm A, Arm B and Arm C were 64.8, 69.0 and

68.6%, respectively. The proportion of phase III in any cohort is

higher compared with the proportion of phase II (Arm A: 90.1% vs.

9.9%; Arm B: 75.9% vs. 24.1%; Arm C: 90.2% vs. 9.8%). Sex, age, T

stage, N stage, TNM stage and distance from primary tumor to anal

verge were generally well balanced among each group.

| Table I.Baseline patient and tumor

characteristics in three cohorts. |

Table I.

Baseline patient and tumor

characteristics in three cohorts.

| Characteristic | Arm A (n=91) | Arm B (n=29) | Arm C (n=51) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (%) |

|

|

| 0.863 |

|

Male | 59 (64.8) | 20 (69.0) | 35 (68.6) |

|

|

Female | 32 (35.2) | 9 (31.0) | 16 (31.4) |

|

| Age (mean ±

SD) | 56.91±0.962 | 53.69±11.720 | 56.98±8.620 | 0.243 |

| Clinical T stage

(%) |

|

|

| 0.440 |

|

2-3 | 69 (75.8) | 25 (76.2) | 38 (74.5) |

|

| 4 | 22 (24.1) | 4 (13.8) | 13 (25.5) |

|

| Clinical N stage

(%) |

|

|

| 0.161 |

|

0-1 | 48 (52.7) | 20 (69.0) | 24 (47.1) |

|

| 2 | 43 (47.3) | 9 (31.0) | 27 (52.9) |

|

| Tumor node

metastasis (%) |

|

|

| 0.102 |

| II | 9 (9.9) | 7 (24.1) | 5 (9.8) |

|

|

III | 82 (90.1) | 22 (75.9) | 46 (90.2) |

|

| MMR status (%) |

|

|

| 0.056 |

|

dMMR/unknown | 27 (29.7) | 10 (34.5) | 7 (13.7) |

|

|

pMMR | 64 (70.3) | 19 (65.5) | 44 (86.3) |

|

| Circumferential

resection margin (%) |

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Positive | 48 (52.7) | 7 (24.1) | 30 (58.8) |

|

|

Negative | 27 (29.7) | 6 (20.7) | 17 (33.3) |

|

|

Unknown | 16 (17.6) | 16 (55.2) | 4 (7.8) |

|

| Extramural vascular

invasion (%) |

|

|

| <0.001 |

|

Positive | 40 (43.9) | 5 (17.2) | 24 (47.1) |

|

|

Negative | 29 (31.9) | 4 (13.8) | 19 (37.3) |

|

|

Unknown | 22 (24.2) | 20 (69.0) | 8 (15.7) |

|

| Distance from

primary tumor to anal verge (median + range, cm) | 5.0 (0.5-10.0) | 5.0 (2.0-10.0) | 6.0 (1.5-9.8) | 0.830 |

Efficacy

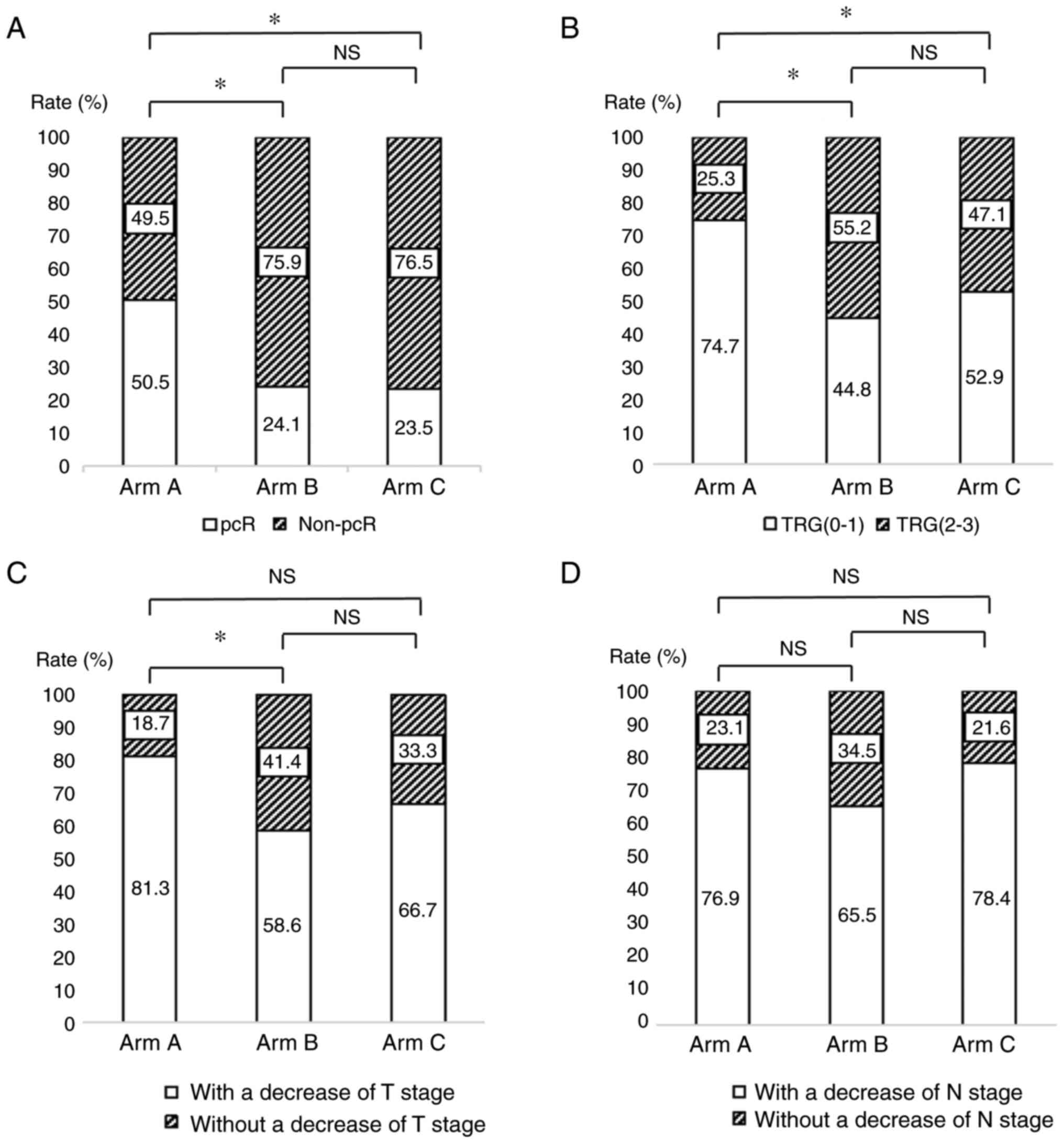

The pCR rates for Arm A, Arm B and Arm C were 50.5,

24.1 and 23.5%, respectively (Table

II). The pCR rate was different between Arm A and Arm B, and

between Arm A and Arm C, while there was no significant difference

between Arm B and Arm C (Fig. 2A).

The percentages of pT0 were 50.5 (Arm A), 24.1 (Arm B) and 23.5%

(Arm C) and pN0 were 80.2 (Arm A), 79.3 (Arm B) and 74.5% (Arm C)

in different groups, respectively (Table II). The percentage of TRG (the

criterion of TRG refers to the American Joint Committee on Cancer

8th edition) (21) of grade 0–1 was

higher in Arm A compared with that in the remaining two Arms (Arm

A: 76.9%, Arm B: 44.8%, Arm C:52.9%) (Table II and Fig. 2B). The proportions of Arm A, Arm B

and Arm C with a decrease of at least one level in T stage were

81.3, 58.6 and 66.7% and with a N downstaging at least one level

were 76.9, F65.5 and 78.4%, respectively (Table II). There was no difference in T

and N downstaging between either group, except that Arm A has a

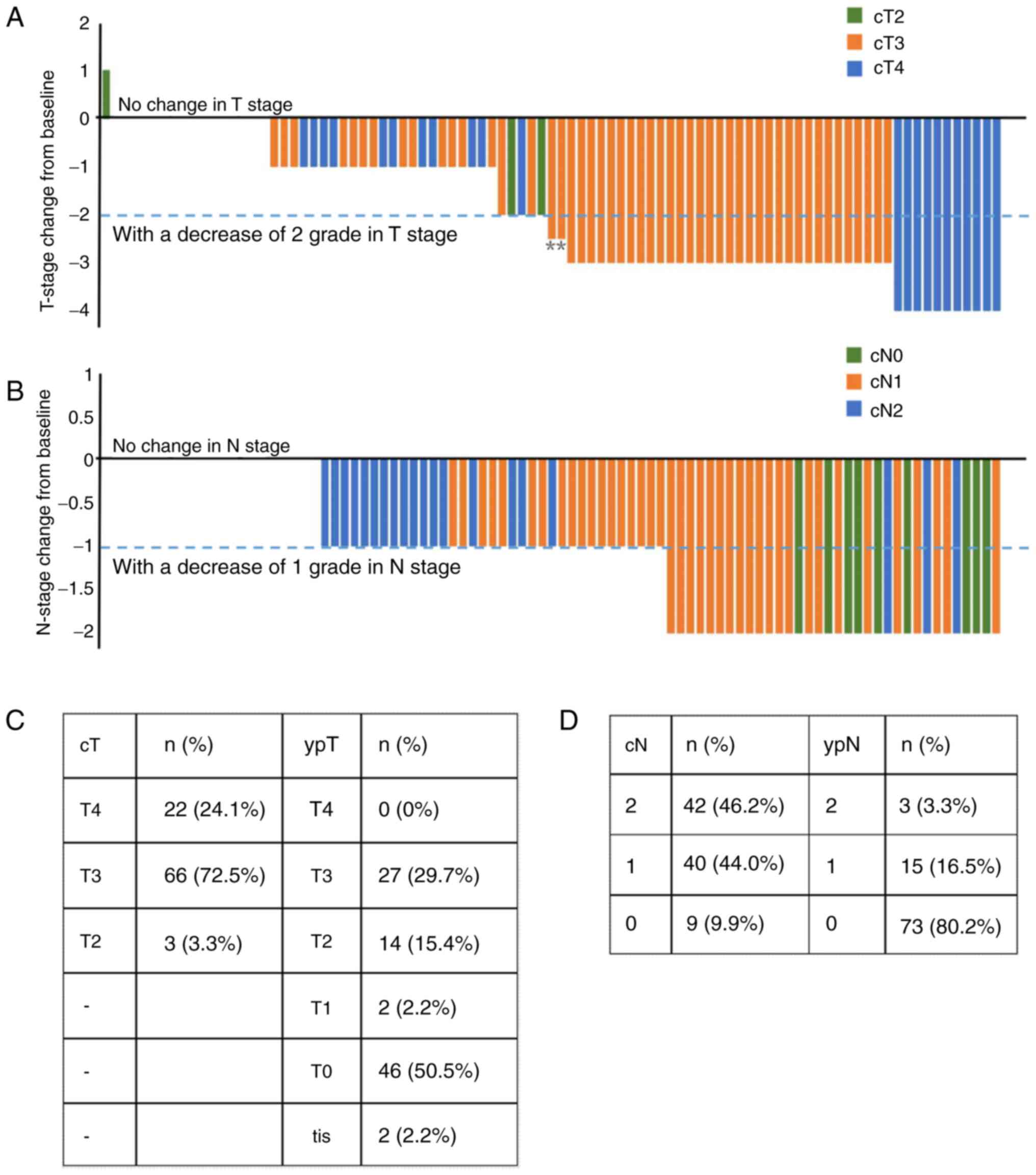

significant T-downstaging vs. Arm B (Fig. 2C and D). Fig. 3 presents the T stage and N stage of

Arm A patients at baseline and postoperative.

| Table II.Postoperative pathological results in

Arm A, Arm B and Arm C. |

Table II.

Postoperative pathological results in

Arm A, Arm B and Arm C.

| Pathological

results | Arm A (n=91)

(%) | Arm B (n=29)

(%) | Arm C (n=51)

(%) |

|---|

| ypT |

|

|

|

|

tis | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 0 | 46 (50.5) | 7 (24.1) | 12 (23.5) |

| 1 | 2 (2.2) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (3.9) |

| 2 | 14 (15.4) | 5 (17.2) | 13 (25.5) |

| 3 | 27 (29.7) | 15 (51.7) | 23 (45.1) |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) |

| ypN |

|

|

|

| 0 | 73 (80.2) | 23 (79.3) | 38 (74.5) |

| 1 | 15 (16.5) | 5 (17.2) | 9 (17.6) |

| 2 | 3 (3.3) | 1 (3.4) | 4 (7.8) |

| ypTNM |

|

|

|

|

pCR | 46 (50.5) | 7 (24.1) | 12 (23.5) |

| 0 | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I | 9 (9.9) | 6 (20.7) | 10 (19.6) |

| II | 16 (17.6) | 10 (34.5) | 16 (31.4) |

|

III | 18 (19.8) | 6 (20.7) | 13 (25.5) |

| TRG |

|

|

|

| 0 | 46 (50.5) | 7 (24.1) | 12 (23.5) |

| 1 | 22 (24.2) | 6 (20.7) | 15 (29.4) |

| 2 | 19 (20.9) | 14 (48.3) | 22 (43.1) |

| 3 | 4 (4.4) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (3.9) |

Prognostic factors associated with pCR

in Arm A

In the ROC analysis for the albumin, total

cholesterol, LDH, neutrophil, platelet, lymphocyte, NLR and PLR

cutoff values, the areas under the curve were 0.525 (P=0.688),

0.594 (P=0.156), 0.502 (P=0.982), 0.581 (P=0.179), 0.541 (P=0.505),

0.507 (P=0.916), 0.549 (P=0.425) and 0.549 (P=0.422) for pCR,

respectively (data not shown). Finally, albumin >37.9 g/l, total

cholesterol >4.45 mmol/l, LDH >141 U/l, neutrophil

>2.62×109/l, platelet >244×109/l,

lymphocyte >1.44×109/l, NLR >3 and PLR >128

were classified into the high-level group. Binary logistic

regression analysis was performed for the following 10 criteria: i)

Sex; ii) age; iii) albumin; iv) total cholesterol; v) LDH; vi)

neutrophil; vii) platelet; viii) lymphocyte; ix) NLR; x) PLR.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed showing that

baseline total cholesterol >4.45 mmol/l, neutrophil

≤2.62×109/l and PLR >128 were significant prognostic

factors of pCR, and multivariate regression analysis showed that

baseline total cholesterol >4.45 mmol/l, neutrophil

≤2.62×109/l were selected as the independent factors for

pCR (Table III).

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate logistics

regressions for predicting pCR. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate logistics

regressions for predicting pCR.

|

| Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) |

|---|

| Albumin (g/l) |

|

|

|

|

|

>37.9 | 0.208 | 1.857

(0.708-4.868) |

|

|

|

≤37.9 |

| 1 |

|

|

| Total cholesterol

(mmol/l) |

|

|

|

|

|

>4.45 | 0.026 | 2.856

(1.134-7.190) | 0.016 | 3.456

(1.255-9.517) |

|

≤4.45 |

| 1 |

| 1 |

| LDH (U/l) |

|

|

|

|

|

≤141 | 0.217 | 0.465

(0.138-1.568) |

|

|

|

>141 |

| 1 |

|

|

| Neutrophil

(×109/l) |

|

|

|

|

|

≤2.62 | 0.012 | 3.810

(1.337-10.861) | 0.020 | 4.370

(1.258-15.180) |

|

>2.62 |

| 1 |

| 1 |

| Platelet

(×109/l) |

|

|

|

|

|

>244 | 0.090 | 2.175

(0.886-5.340) |

|

|

|

≤244 |

| 1 |

|

|

| Lymphocyte

(×109/l) |

|

|

|

|

|

>1.44 | 0.347 | 1.500

(0.644-3.492) |

|

|

|

≤1.44 |

| 1 |

|

|

| NLR |

|

|

|

|

| ≤3 | 0.999 | - |

|

|

|

>3 |

| - |

|

|

| PLR |

|

|

|

|

|

>128 | 0.047 | 2.390

(1.013-5.635) | 0.075 | 2.481

(0.913-6.744) |

|

≤128 |

| 1 |

| 1 |

Discussion

The present study validated that the regimen of SCRT

plus 2 cycles of chemotherapy and camrelizumab could significantly

increase the pCR rate in patients with LARC by two-fold (Arm A vs.

Arm C, 50.5% vs. 23.5%). Unfortunately, the mechanism of such a

high pCR rate with this regimen is not clarified. At the same time,

studies using hematological indicators to predict pCR in this

specific cohort have not been conducted. Therefore, the present

study performed this study on 91 patients who were enrolled in the

Arm A.

As aforementioned, NLR, LDH and PLR can be used as

predictors of prognosis in rectal cancer and are negatively

correlated with OS and PFS (15,22,23).

However, the results of a study that included 1,237 patients showed

that NLR and PLR not only did not predict the prognosis of patients

with locally advanced rectal cancer, but also did not predict the

pCR rate after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (24). Instead, this is consistent with the

present findings, which showed that although PLR was associated

with pCR, it was not an independent predictor of pCR. These studies

with contradictory results indicates that the role of these

indicators in predicting prognosis needs to be explored in

depth.

However, notably, the present study revealed that

high total cholesterol and low neutrophils at baseline were

associated with higher pCR rates. As early as 1997, it has been

suggested that total serum cholesterol levels are positively

correlated with the development of colorectal cancer (25). Cholesterol can promote tumorigenesis

and progression by participating in the regulation of different

signaling pathways (26,27). Cholesterol plays an indispensable

role in maintaining the stability of cell membranes and in the

growth and differentiation of cells, which include but are not

specific to lymphocytes (28,29).

Therefore, we hypothesize that the explanation for the effective

and aggressive killing of tumor cells in the Arm A may also be that

cholesterol provided the material source needed for the lymphocytes

to function effectively. However, the specific mechanism needs to

be further explored before it can be clarified.

Neutrophils are often involved in the inflammatory

response in the body and can contribute to tumorigenesis,

progression and metastasis by secreting different factors (30,31).

Meng et al (32) have

demonstrated that high neutrophils indicate a worse DFS. Higher

neutrophil levels in tumor tissue are a risk factor for reduced

5-DFS in patients with colorectal cancer (33). Similarly, in squamous carcinoma of

the anal canal, the cohort of high neutrophils at baseline exhibit

poor local control rates (34).

Overall, high neutrophils are a detrimental presence for patients

with rectal cancer. The present results show that low neutrophils

at baseline are an independent influence in predicting high pCR,

corroborating that high neutrophil status may enhance tumor

resistance to therapy. To some extent, it can be considered that

the relationship between NLR and neutrophil levels is positively

correlated. Since immune checkpoint inhibitors eliminate tumor

cells by enhancing the cytotoxic effect of T cells, the number of

lymphocytes may not visually reflect the killing ability of

lymphocytes (35). It may explain

why lymphocytes and NLR are not associated with the pathological

response.

For patients with rectal cancer who receive

neoadjuvant therapy, if they achieve CCR, a treatment strategy of

observation can be adopted (10).

This can reduce the damage caused by the surgery itself including

psychological and physical damage to the patient (36,37).

However, the concordance between CCR rates and pCR rates varies and

is highly influenced by human consciousness. The result of a study

of 488 patients showed that only 25% of patients who achieved CCR

were pCR (38). This means that 75%

of these patients would be in a situation of delayed treatment if

they did not receive surgical treatment (38). By contrast, the rate of CCR (14.3%;

13/91) in the present study was lower compared with the pCR rate,

which would have led to patients receiving overtreatment. If pCR

can be accurately predicted through easy and cost-effective blood

indicators, then these indicators can provide some reference when

making treatment decisions for patients.

In conclusion, short-course radiotherapy followed by

chemotherapy and camrelizumab as a neoadjuvant treatment for

locally advanced rectal cancer could significantly improve the pCR

rate, and PLR, high cholesterol and low neutrophils at baseline

were favorable prognostic factors. Furthermore, high cholesterol

and low neutrophils at baseline were independently associated with

high pCR rates.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Shanghai Cancer Prevention and Anti-Cancer Development

Foundation 2020 Discovery research funding (grant no. 2020HX025).

CSCO Tongshu Oncology Research Fund (grant no.

Y-tongshu2021/qn-0205). CSCO Xinda Oncology Immunotherapy Research

Fund (grant no. Y-XD202002-0168).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

FZ, DY, TZ and ZL conceived and designed this study.

JY, MZ, LL participated in the data curation. FZ, DY, LZ and JW

analyzed the data. ZL provided the administrative support. FZ and

DY drafted the manuscript and all authors reviewed it. TZ and ZL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics

Committee of the Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of

Science and Technology (approval no. 0271-21).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Azad

N, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D,

Garrido-Laguna I, et al: Rectal cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN

clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

20:1139–1167. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B,

Marijnen CAM, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Roodvoets AGH, Nagtegaal ID,

Beets-Tan RGH, Blomqvist LK, et al: Short-course radiotherapy

followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME)

versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant

chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): A

randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 22:29–42.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer

A, Michalski W, Bebenek M and Kryj M: Long-term results of a

randomized trial comparing preoperative short-course radiotherapy

with preoperative conventionally fractionated chemoradiation for

rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 93:1215–1223. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nagasaka M, Zaki M, Kim H, Raza SN, Yoo G,

Lin HS and Sukari A: PD1/PD-L1 inhibition as a potential

radiosensitizer in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A case

report. J Immunother Cancer. 4:832016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Schoenhals JE, Seyedin SN, Tang C, Cortez

MA, Niknam S, Tsouko E, Chang JY, Hahn SM and Welsh JW: Preclinical

rationale and clinical considerations for radiotherapy plus

immunotherapy: Going beyond local control. Cancer J. 22:130–137.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Meng X, Feng R, Yang L, Xing L and Yu J:

The role of radiation oncology in immuno-oncology. Oncologist. 24

(Suppl 1):S42–S52. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang Y, Deng W, Li N, Neri S, Sharma A,

Jiang W and Lin SH: Combining immunotherapy and radiotherapy for

cancer treatment: Current challenges and future directions. Front

Pharmacol. 9:1852018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Vitale I, Harrington

KJ, Melero I and Galluzzi L: Immunological impact of cell death

signaling driven by radiation on the tumor microenvironment. Nat

Immunol. 21:120–134. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lin Z, Cai M, Zhang P, Li G, Liu T, Li X,

Cai K, Nie X, Wang J, Liu J, et al: Phase II, single-arm trial of

preoperative short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy and

camrelizumab in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Immunother

Cancer. 9:e0035542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

López-Campos F, Martín-Martín M,

Fornell-Pérez R, García-Pérez JC, Die-Trill J, Fuentes-Mateos R,

López-Durán S, Domínguez-Rullán J, Ferreiro R, Riquelme-Oliveira A,

et al: Watch and wait approach in rectal cancer: Current

controversies and future directions. World J Gastroenterol.

26:4218–4239. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Guillem JG, Ruby JA, Leibold T, Akhurst

TJ, Yeung HW, Gollub MJ, Ginsberg MS, Shia J, Suriawinata AA,

Riedel ER, et al: Neither FDG-PET Nor CT can distinguish between a

pathological complete response and an incomplete response after

neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: A

prospective study. Ann Surg. 258:289–295. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dayde D, Tanaka I, Jain R, Tai MC and

Taguchi A: Predictive and prognostic molecular biomarkers for

response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 18:5732017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yamamoto T, Kawada K, Hida K, Matsusue R,

Itatani Y, Mizuno R, Yamaguchi T, Ikai I and Sakai Y: Combination

of lymphocyte count and albumin concentration as a new prognostic

biomarker for rectal cancer. Sci Rep. 11:50272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cheong C, Shin JS and Suh KW: Prognostic

value of changes in serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels for

preoperative chemoradiotherapy response in locally advanced rectal

cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 26:7022–7035. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Huang CM, Huang MY, Tsai HL, Huang CW, Su

WC, Chang TK, Chen YC, Li CC and Wang JY: Pretreatment

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio associated with tumor recurrence and

survival in patients achieving a pathological complete response

following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 13:45892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Doi H, Yokoyama H, Beppu N, Fujiwara M,

Harui S, Kakuno A, Yanagi H, Hishikawa Y, Yamanaka N and Kamikonya

N: Neoadjuvant modified short-course radiotherapy followed by

delayed surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 13:41122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ergen ŞA, Barlas C, Yıldırım C and Öksüz

D: Prognostic role of peripheral neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)

and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in patients with rectal cancer

undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Gastrointest Cancer.

53:151–160. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tjokrowidjaja A, Lord SJ, John T, Lewis

CR, Kok PS, Marschner IC and Lee CK: Pre- and on-treatment lactate

dehydrogenase as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in advanced

non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 128:1574–1583. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Petrelli F, Cabiddu M, Coinu A, Borgonovo

K, Ghilardi M, Lonati V and Barni S: Prognostic role of lactate

dehydrogenase in solid tumors: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of 76 studies. Acta Oncol. 54:961–970. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Scartozzi M, Giampieri R, Maccaroni E, Del

Prete M, Faloppi L, Bianconi M, Galizia E, Loretelli C, Belvederesi

L, Bittoni A and Cascinu S: Pre-treatment lactate dehydrogenase

levels as predictor of efficacy of first-line bevacizumab-based

therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer.

106:799–804. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR,

Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR,

Sullivan DC, et al: AJCC cancer staging manual. (8th edition).

Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on

Cancer; 2017, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Basile D, Garattini SK, Corvaja C, Montico

M, Cortiula F, Pelizzari G, Gerratana L, Audisio M, Lisanti C,

Fanotto V, et al: The MIMIC study: Prognostic role and cutoff

definition of monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio and lactate

dehydrogenase levels in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist.

25:661–668. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Partl R, Paal K, Stranz B, Hassler E,

Magyar M, Brunner TB and Langsenlehner T: The pre-treatment

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor for

loco-regional control in locally advanced rectal cancer.

Diagnostics (Basel). 13:6792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dudani S, Marginean H, Tang PA, Monzon JG,

Raissouni S, Asmis TR, Goodwin RA, Gotfrit J, Cheung WY and Vickers

MM: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios as

predictive and prognostic markers in patients with locally advanced

rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation. BMC Cancer.

19:6642019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yamada K, Araki S, Tamura M, Sakai I,

Takahashi Y, Kashihara H and Kono S: Relation of serum total

cholesterol, serum triglycerides and fasting plasma glucose to

colorectal carcinoma in situ. Int J Epidemiol. 27:794–798. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Oneyama C, Iino T, Saito K, Suzuki K,

Ogawa A and Okada M: Transforming potential of Src family kinases

is limited by the cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomain. Mol

Cell Biol. 29:6462–6472. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sheng R, Kim H, Lee H, Xin Y, Chen Y, Tian

W, Cui Y, Choi JC, Doh J, Han JK and Cho W: Cholesterol selectively

activates canonical Wnt signalling over non-canonical Wnt

signalling. Nat Commun. 5:43932014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Blank N, Schiller M, Gabler C, Kalden JR

and Lorenz HM: Inhibition of sphingolipid synthesis impairs

cellular activation, cytokine production and proliferation in human

lymphocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 71:126–135. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yamaguchi T and Ishimatu T: Effects of

cholesterol on membrane stability of human erythrocytes. Biol Pharm

Bull. 43:1604–1608. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xiong S, Dong L and Cheng L: Neutrophils

in cancer carcinogenesis and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol.

14:1732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Khan U, Chowdhury S, Billah MM, Islam KMD,

Thorlacius H and Rahman M: Neutrophil extracellular traps in

colorectal cancer progression and metastasis. Int J Mol Sci.

22:72602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Meng X, Shi D, Zheng H, Xu Y, Li Q, Cai S

and Cai G: High preoperative peripheral blood neutrophil predicts

poor outcome in rectal cancer treated with neoadjunctive

chemoradiation therapy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 10:7718–7725.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Rottmann BG, Patel N, Ahmed M, Deng Y,

Ciarleglio M, Vyas M, Jain D and Zhang X: Clinicopathological

significance of neutrophil-rich colorectal carcinoma. J Clin

Pathol. 76:34–39. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Schernberg A, Huguet F, Moureau-Zabotto L,

Chargari C, Rivin Del Campo E, Schlienger M, Escande A, Touboul E

and Deutsch E: External validation of leukocytosis and neutrophilia

as a prognostic marker in anal carcinoma treated with definitive

chemoradiation. Radiother Oncol. 124:110–117. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, Tatiparti K,

Bhise K, Bhise K, Kashaw SK and Iyer AK: PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint

signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism,

combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 8:5612017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Paun BC, Cassie S, MacLean AR, Dixon E and

Buie WD: Postoperative complications following surgery for rectal

cancer. Ann Surg. 251:807–818. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mei F, Yang X, Na L and Yang L: Anal

preservation on the psychology and quality of life of low rectal

cancer. J Surg Oncol. 125:484–492. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hiotis SP, Weber SM, Cohen AM, Minsky BD,

Paty PB, Guillem JG, Wagman R, Saltz LB and Wong WD: Assessing the

predictive value of clinical complete response to neoadjuvant

therapy for rectal cancer: An analysis of 488 patients. J Am Coll

Surg. 194:131–136. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|