Introduction

Cervical cancer accounts for a considerable

proportion of gynecological malignancies. Cervical cancer ranked

fourth among female cancer-related morbidity and mortality, with

661,021 new cases and 348,189 deaths in 2022 (1). According to GLOBOCAN 2022, cases in

China accounted for 22.7% and 16.0% of global morbidity and

mortality rates, respectively, with 150,659 new cases and 55,694

deaths (2). In addition, due to the

low population coverage rate (21.4%) for cervical cytology and the

low human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rate, eliminating

cervical cancer is a challenging task (3). Currently, cervical cancer is treated

with a comprehensive conventional approach that includes surgery,

radiotherapy and chemotherapy (4).

However, this strategy is not effective in patients with advanced

cancer, and there is a high incidence of recurrence and metastasis.

The 5-year disease-free survival is approaches 100% for patients

with stage IA cervical cancer, 70–85% for those with stage IB1 and

smaller IIA lesions, 50–70% for those with stages IB2 and IIB,

30–50% for those with stage III, and 5–15% for those with stage IV

(5). Therefore, it is important to

elucidate the mechanisms of cervical cancer development and

identify specific tumor markers.

It has been established that the activation of

proto-oncogenes and the inactivation or mutation of tumor

suppressor genes are involved in the tumorigenesis of cancer

(6). Therefore, genes related to

cervical cancer were screened out using the Gene Expression

Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) database. CHMP4C, as a

subunit of endosomal sorting complex required for transport-III, is

essential for the Aurora B-mediated abscission checkpoint (NoCut)

and can delay the abscission time and reduce the accumulation of

DNA damage (7,8). A previous study also reported that

CHMP4C is undetectable in normal tissues but overexpressed in

ovarian cancer tissues (9).

Moreover, there are higher expression levels of CHMP4C in the

extracellular vesicles of prostate cancer with a high Gleason

score, which may promote the progression of prostate cancer

(10). However, the relationship

between CHMP4C and cervical cancer remains to be studied.

Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the role of CHMP4C in

the development of cervical cancer and evaluate the regulatory

pathways in which CHMP4C may be involved.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

GEPIA (gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) was used to

screen genes overexpressed in cervical squamous cell cancer,

developed survival curve, and automatically calculate Log-rank and

HR. Additionally, targetscan (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), mirDIP

(http://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/),

and miR-Gator (http://mirgator.kobic.re.kr/), to suggest miRNA with

binding sites to target genes.

Specimens

The present study obtained 19 normal cervical

tissues, 88 cervical squamous cell carcinoma tissues and 8 cervical

adenocarcinoma tissues from hospitalized patients in the Third

Affiliated Hospital Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou, China)

between 2014–2019. Patients diagnosed with metastatic cervical

cancer or other malignant tumors, or with a history of radiotherapy

and chemotherapy before surgery were excluded. The patients agreed

to use the tissue removed during surgery for general scientific

research and signed an informed consent form. The Ethics Committee

of the Third Affiliated Hospital Guangzhou Medical University

approved the present study (approval no. 2019-037). The tissues

were scored according to the degree of staining and the percentage

of positively stained cells, and the final scores were added.

Cell culture

The HPV16-positive cervical cancer SiHa cell line

(National Infrastructure of Cell Line Resource) was cultured in

RPMI1640 medium (HyClone; Cytiva), and the human cervical

epithelial immortalized H8 (Jennio Biotech Co., Ltd.),

HPV16-positive cervical cancer Caski (National Infrastructure of

Cell Line Resource) and HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa

(Pricella®; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (HyClone; Cytiva),

containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Shanghai Excell Biological

Technology Co., Ltd.). The cells were plated in petri dishes and

cultured in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2

atmosphere.

Small interfering (si)RNA

transfection

siRNAs (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) against target

genes were used to knockdown the expression of the target genes,

and Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used

as a cell transfection reagent. A total of 50 nM siRNA was

transfected into SiHa and HeLa cells at 37°C for 48 h immediately

before subsequent experiment. The target genes and corresponding

siRNA sequences were as follows: CHMP4C,

5′-CAGAUUGAUGGCACACUUUdTdT-3′ (forward) and

5′-AAAGUGUGCCAUCAAUCUGdTdT-3′ (reverse); HPV16 E6,

5′-GAGUAUAGACAUUAUUGUUdTdT-3′ (forward) and

5′-AACAAUAAUGUCUAUACUCdTdT-3′ (reverse); and HPV18 E6,

5′-CAGACUCUGUGUAUGGAGAdTdT-3′ (forward) and

5′-UCUCCAUACACAGAGUCUGdTdT-3′ (reverse). The scrambled siRNA

sequences used for the control were as follows:

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTTdTdT-3′ (forward) and

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATTdTdT-3′ (reverse).

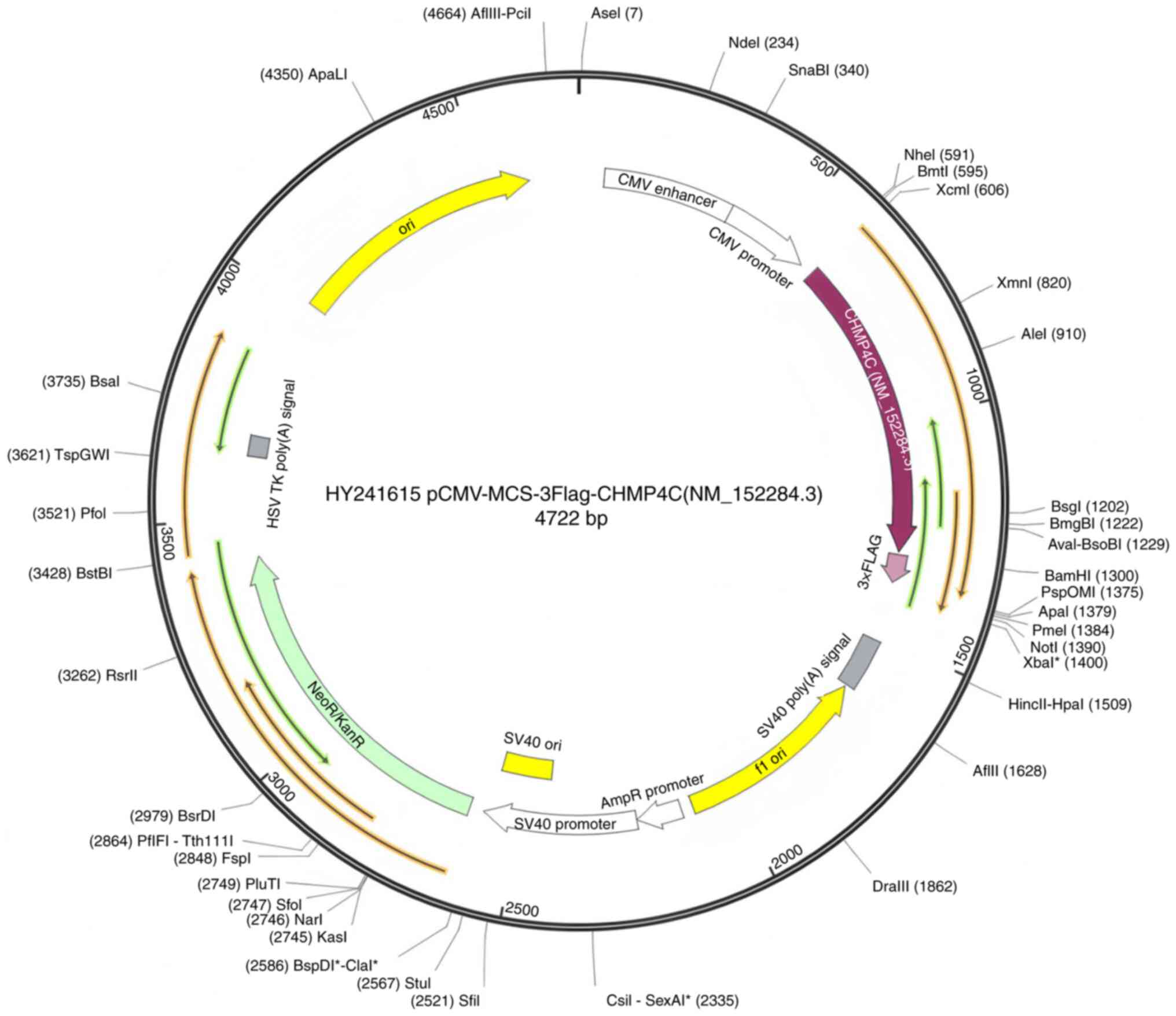

Plasmid and mimics transfection

Full-length cDNAs of human CHMP4C were synthesized

by Guangzhou Dahong Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and cloned into the

expression vector pCMV-MCS-3Flag (Guangzhou Dahong Biotechnology

Co., Ltd) (Fig. 1). When cell

confluence reached 80–90%, the plasmids were transfected using

Lipofectamine 3000 and p3000 reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), following the manufacturer's protocol. A total of 50 nM

microRNA (miRNA/miR) and negative control mimics (Guangzhou RiboBio

Co., Ltd.) were transfected into SiHa and HeLa cells using

Lipofectamine 3000 reagent. A total of 48 h after transfection at

37°C, the transfection efficiency was immediately assessed using

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The sequences of

the miR-543 mimic were 5′-AAACAUUCGCGGUGCACUUCUU-3′ (sense),

5′-UUUGUAAGCGCCACGUGAAGAA-3′ (antisense). The sequences of the

negative control mimic were 5′-UUUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′ (sense),

5′-AAACAUGAUGUGUUUUCAUGAC-3′ (antisense).

MTT assay

After the SiHa and HeLa cells were digested and

collected, 3×103 cells and 100 µl medium were added to

each well in a 96-well plate. After the cells had adhered, the

experimental group was transfected with CHMP4C siRNA, whereas the

negative control group was transfected with scramble siRNA. A total

of 20 µl MTT solution was then added to each well, followed by

incubation at 37°C for 4 h. The liquid was then aspirated from the

well, and 150 µl dimethyl sulfoxide was added. Finally, a

microplate reader (BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used to

measure the optical density value of each well at 490 nm.

Wound-healing assay

SiHa and HeLa cells were inoculated in a six-well

plate. When the cell density reached ~80%, a 200 µl pipette tip was

used to scratch the cells, and then serum-free medium was added.

Images of the scratches were captured under a microscope (Olympus

IX73; fluorescence microscope; Olympus Corporation and Leica DMi1;

light microscope; Leica Microsystems GmbH) and then processed using

cellSens Version 2.1 (Olympus Corporation) and Leica Application

Suite X Version 4.12 software (Leica Microsystems GmbH). The wound

area was measured using Image J software Version 1.52a (National

Institutes of Health). The following formula was used to assess the

level of wound-healing: Mobility=(starting area-final

area)/starting area ×100%.

Apoptosis assay

The transfected SiHa and HeLa cells were collected

using EDTA-free trypsin and washed once with PBS. The cells were

resuspended in 100 µl binding buffer (1X) and 5 µl Annexin

V-FITC/PI staining solution (BD Biosciences) and placed in the

dark. After the addition of 400 µl binding buffer (1X) to each

tube, apoptosis was detected using flow cytometry (BD FACScanto™ II

Clinical Flow Cytometry System; BD Biosciences, and Attune NxT Flow

Cytometer; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). FlowJo software

(version 10.8; BD Biosciences) and Attune NxT Flow Cytometry

Software (version 2.6; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used

for analysis.

Cell invasion assay

Matrigel (BD Bioscience) was diluted at a 1:15 ratio

with cold serum-free medium (RPMI-1640 or DMEM; HyClone; Cytiva)

refrigerated at 4°C and 30 µl was plated into the filters of the

Transwell chambers (Corning, Inc.). Then the chambers were placed

in a 24-well plate in a 37°C incubator for 4 h. Cells were

suspended at a density of 4×104 in 200 µl serum-free

medium (RPMI1640 or DMEM, HyClone; Cytiva) and plated in the upper

chamber, whilst 600 µl medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (Shanghai Excell Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Bio) was

added to the lower chamber. After incubation at 37°C for 48 h, the

chamber was fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min and stained with

1% crystal violet for 15 min both at room temperature. Photographs

were captured under a microscope (Olympus IX73, fluorescence

microscope, Olympus Corporation), and the invasive cells were

manually counted. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and

images of 3 fields of view were captured for each replicate.

Immunohistochemistry

The normal and cervical cancer tissues were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde (at room temperature for 24 h, embedded in

paraffin wax, and cut into 4 mm slices. The paraffin-embedded

tissue sections were heated in a 65°C incubator for 4 h and dewaxed

with xylene (Foshan Bodi Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd) for 20 min

twice at room temperature. Then they were immersed into 100%

alcohol (Foshan Bodi Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd) for 5 min, 95%

alcohol for 2 min, 85% alcohol for 2 min, 75% alcohol for 1 min,

and finally turned into distilled water for 3 min 3 times, so as to

fully hydrate. The sections were immersed in an EDTA antigen

retrieval solution and heated in a pressure cooker for 5 min with

the cover unlocked. Then the cooker was locked, removed from the

heat source 3 min after the pressure reaches the highest. After

then, the sections allowed to cool at room temperature. After

inactivation of endogenous catalase activity using 3% hydrogen

peroxide, the sections were blocked with 5% BSA (BEIJING SOLARBIO

Technology Co., Ltd.) in a 37°C incubator for 40 min. The sections

were then incubated with anti-CHMP4C antibodies (1:400; #GTX122876;

GeneTex, Inc.) overnight at 4°C. The following day, the sections

were re-warmed at room temperature for 30 min and washed three

times with PBS. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit

antibodies (1:800; cat. no. ab97051; Abcam) were then added and the

sections were incubated for 45 min in a 37°C incubator. After

diaminobenzidine coloration and hematoxylin staining at room

temperature for 10 min, the sections were dehydrated, sealed with a

neutral resin and imaged under a microscope (Leica Microsystems

GmbH).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

As the presence of a binding site between CHMP4C and

miR-543 was predicted (data not shown), a CHMP4C 3′-untranslated

region (3′-UTR) containing a miR-543-binding site sequence was

designed. 293T cells (Pricella®; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were seeded into 24-well plates and

transfected with 600 ng SV40-dual-luciferase vector (Shanghai

Genechem Co., Ltd.) expressing a wild type CHMP4C 3′-UTR using

Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), whilst the

mutant type acted as a control. At the same time, 50 nM miR-543 or

negative mimics (Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.) were co-transfected.

The sequence of the miR-543 mimics were

5′-AAACAUUCGCGGUGCACUUCUU-3′ (sense) and

5′-AAGAAGUGCACCGCGAAUGUUU-3′ (antisense). The sequences of the

negative control mimic were 5′-UUUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′ (sense),

5′-AAACAUGAUGUGUUUUCAUGAC-3′ (antisense). After 48 h, the

Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega

Corporation) was used to detect the level of luciferase activity.

The relative luciferase intensity was normalized to renilla

luciferase activity.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from SiHa and HeLa cervical

cancer cells using the TRIzol reagent (Takara Bio, Inc.). After

separation, precipitation, washing and dissolution, the

concentration of RNA was detected using a spectrophotometer [Unico

(Shanghai) Instrument Co., Ltd.]. For mRNA analysis, 2 µg total RNA

was reverse-transcribed to synthesize complementary (c)DNA using

random primers and avian myeloblastosis virus transcriptase

(PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time); Takara Bio,

Inc.). The reverse transcription program was set at 37°C for 15

min, 85°C for 5 min, and finally cooled to 4°C. qPCR amplification

of the cDNA was then performed using the SYBR® Premix Ex

Taq™ II kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) with 18S as an internal control. The

amplification conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and an 60°C

for 30 sec. The Hairpin-it™ miRNAs qPCR Quantitation Kit (Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd.) was used to detect miRNA expression according

to the manufacturer's protocols, and U6 was used as the internal

reference. The relative expression of CHMP4C or miR-543 was

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (11). The sequences of the primers used

were as follows: CHMP4C, 5′-GAGAAGCCCTGGAGAAC-3′ (forward) and

5′-CACCAAAGCCAACCC-3′ (reverse); 18S, 5′-CTTAGTTGGTGGAGCGATTTGTC-3′

(forward) and 5′-CGGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA-3′ (reverse); miR-543,

5′-GAGAAGTTGCCCGTGTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGCGAATGTTTCGTCA-3′

(reverse); and U6, 5′-CGCTTCGGCAGCACATATAC-3′ (forward) and

5′-AAATATGGAACGCTTCACGA-3′ (reverse).

Western blotting

SiHa and HeLa cell proteins were extracted using

RIPA lysis buffer (Shanghai Bestbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd,) after

transfection, and protein determination was performed by the BCA

method. Proteins of different molecular weights were separated

using 10% SDS-PAGE in which 40 µg protein was loaded to each lane,

and subsequently electrotransferred to Hybond membranes

(MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). Subsequently, 3% BSA (BEIJING

SOLARBIO TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD) was used to block non-specific sites

at room temperature for 2 h, and anti-CHMP4C (1:1,000; #16256-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-Bcl-XL (1:2,000; #10783-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-Bcl2 (1:500; #66799-1-Ig;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-Survivin (1:1,000; #10508-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-Caspase-7 (1:1,000; #27155-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and anti-HPV16/18 E6 (1:50; #sc-460; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) antibodies were added and incubated

overnight at 4°C. Anti-β-actin (1:10,000; #66009-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), GAPDH (1:1,000; #60004-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

or anti-α-tubulin (1:1,000; #80762-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.)

antibodies were used as controls. On the second day, the membrane

was incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; cat. no. #SA00001-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) or anti-mouse (1:10,000; #SA00001-1;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) antibodies at room temperature for 2 h.

The protein bands were visualized using the Enhanced

Chemiluminescence kit (SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS

Chemiluminescence substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Data analysis

SPSS 24.0 software (IBM Corp.) was used to perform

the statistical analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation. The immunohistochemistry results were analyzed

using Fisher's exact test. Comparisons between the experimental and

control groups were performed using an unpaired double-tailed

t-test, and multiple groups were compared using one-way ANOVA and

Dunnett's posttest. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of CHMP4C in the

tumorigenesis of cervical cancer

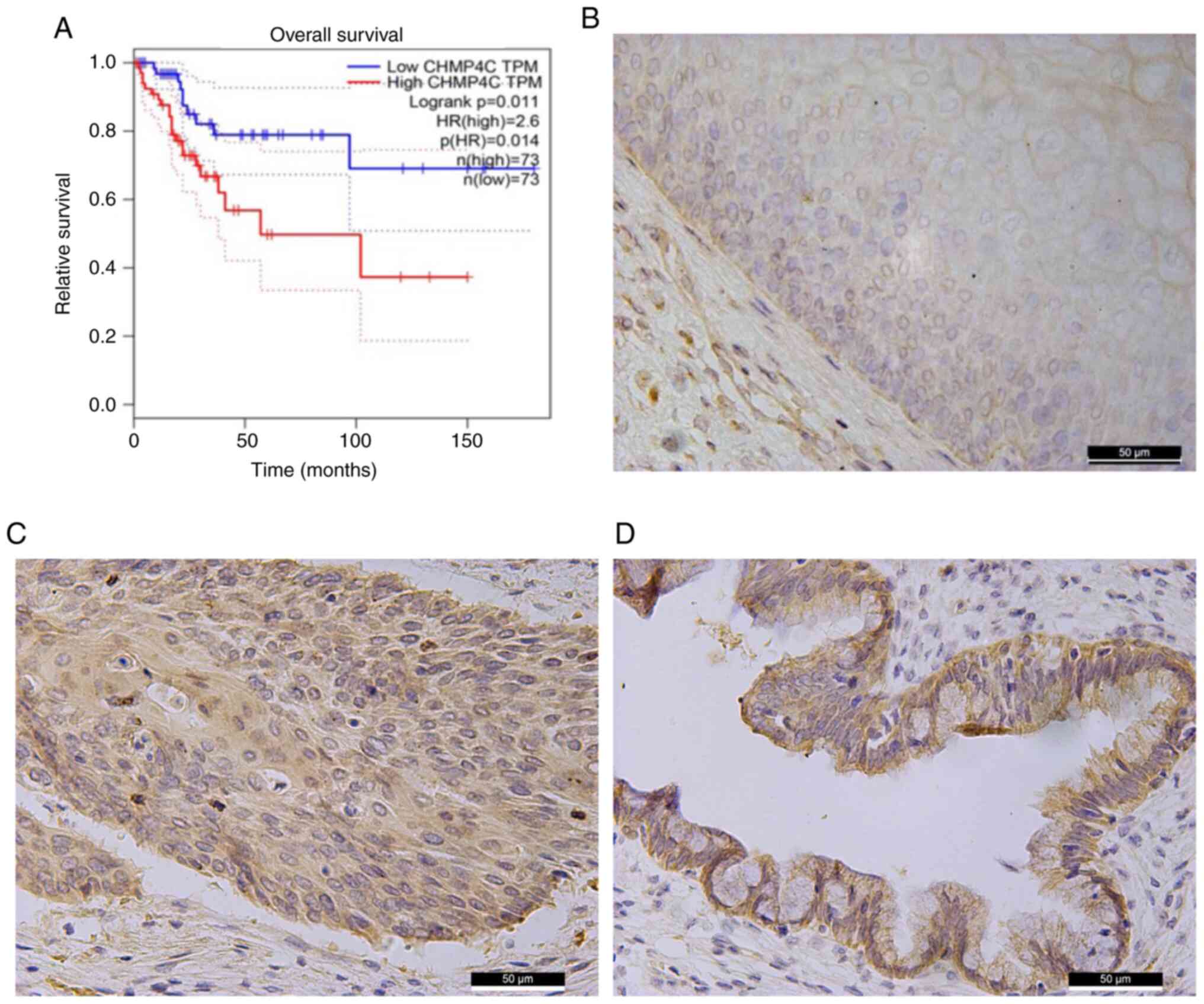

Bioinformatics analysis was used to assess the role

of CHMP4C in cervical cancer. The GEPIA database and log-rank tests

demonstrated that a higher CHMP4C expression may have a worse

clinical prognosis than those with a lower CHMP4C expression

(Fig. 2A). Following this,

immunohistochemistry was performed using normal cervical and

cervical cancer tissues to further assess the expression of CHMP4C

in cervical cancer. The results revealed that the expression level

of CHMP4C in malignant cervical tumor tissues was significantly

higher than that in normal tissues (Fig. 2B-D; Table SI; P<0.05). This finding

indicates that CHMP4C may participate in cervical cancer

tumorigenesis. Moreover, the level of CHMP4C was positively

associated with the age of the patients (Table SII; P<0.05).

Effect of CHMP4C expression on the

phenotype of cervical cancer cells

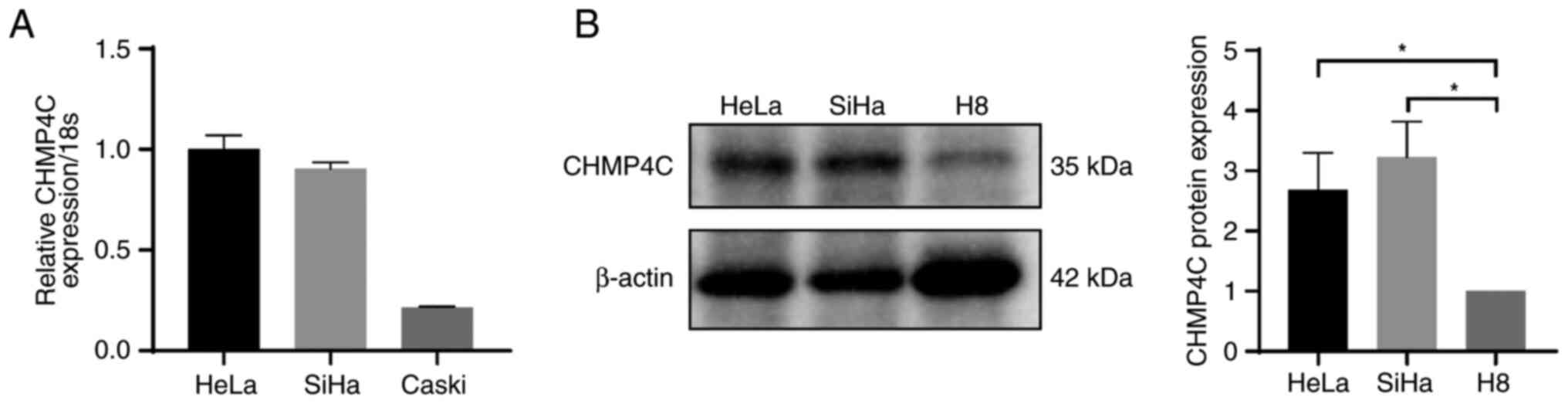

Firstly, expression of CHMP4C in each HPV-positive

cervical cancer cell line was detected using RT-qPCR, and SiHa and

HeLa cells were selected as the experimental objects as they had

the highest expression of CHMP4C out of the cervical cancer cell

lines assessed (Fig. 3A).

Furthermore, western blotting demonstrated that the expression

level of CHMP4C was significantly higher in cervical cancer SiHa

and HeLa cells compared with that in the normal cervical H8 cells

(Fig. 3B).

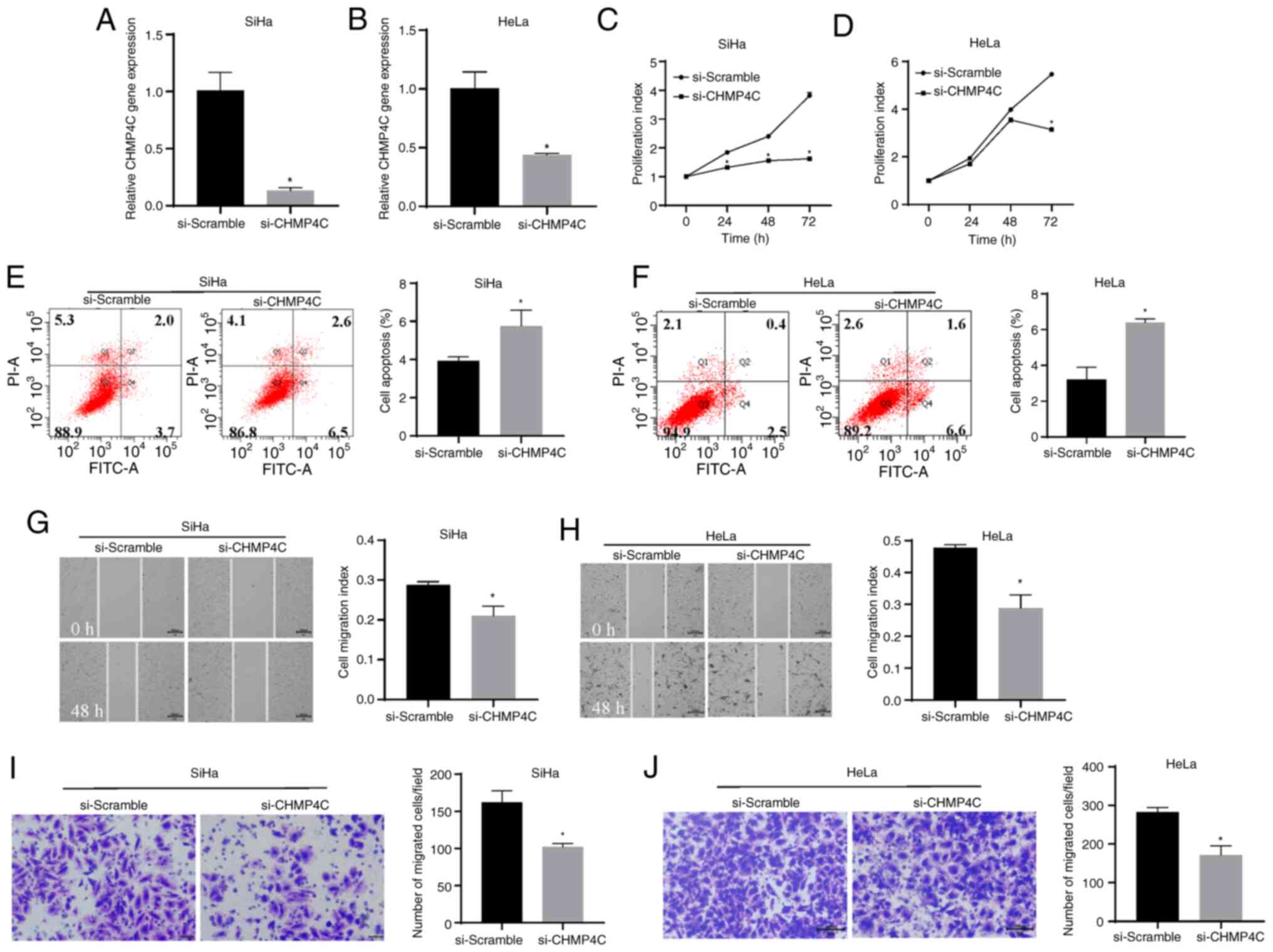

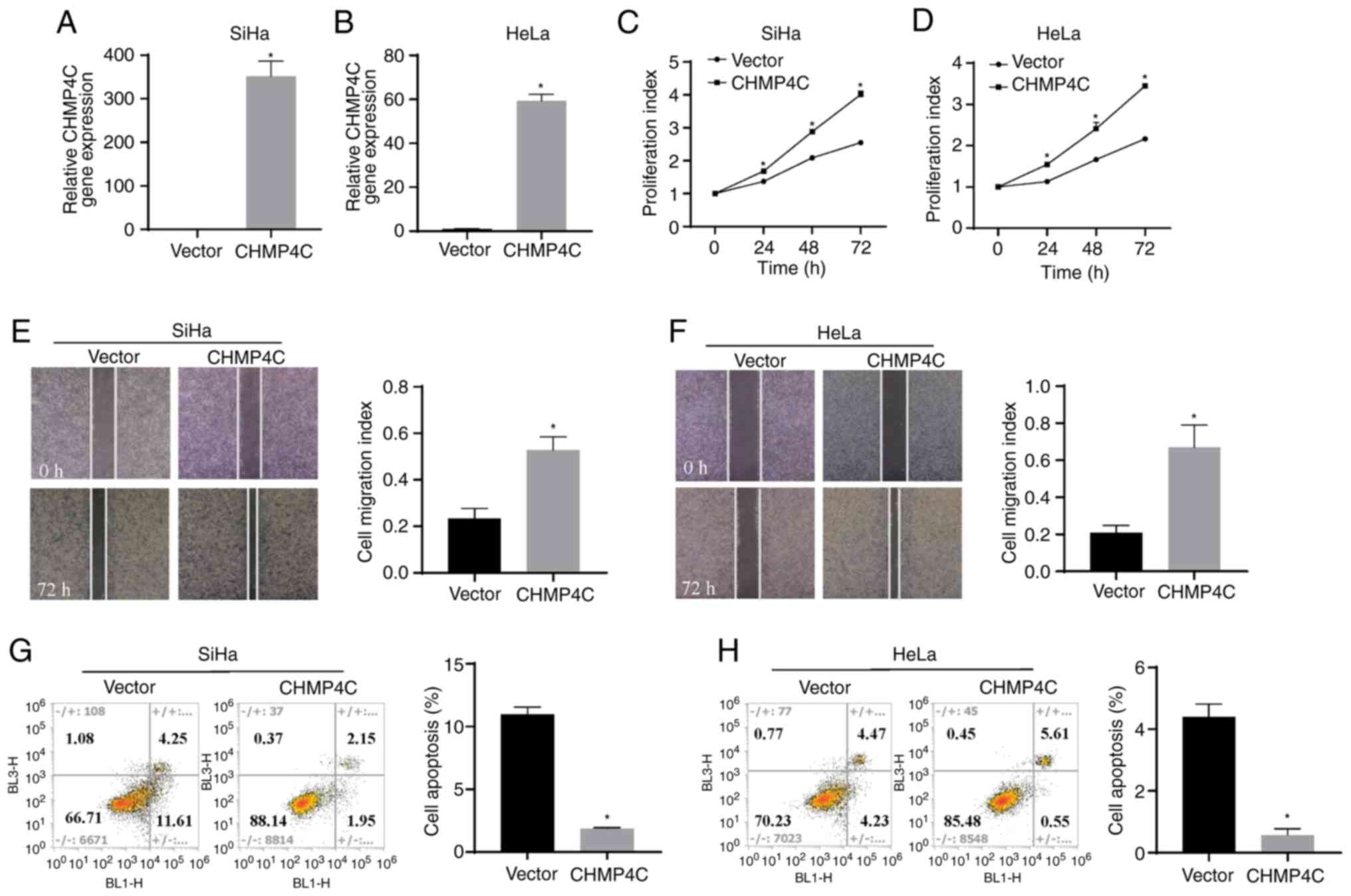

To evaluate the biological function of CHMP4C, SiHa

and HeLa cells were transfected with si-CHMP4C or si-Scramble, and

the transfection efficiency was determined using RT-qPCR. The

results demonstrated that the expression level of CHMP4C

significantly decreased following siRNA transfection, compared with

the control (Fig. 4A and B;

P<0.05). Silencing of CHMP4C expression was also associated with

a significant decrease in cell proliferation, compared with the

control (Fig. 4C and D; P<0.05).

This indicates that CHMP4C promotes cell proliferation. Moreover,

the cell apoptosis assay revealed that after 48 h of transfection,

the si-CHMP4C cells had a significantly higher apoptosis rate than

the control cells (Fig. 4E and F;

P<0.05). A significant reduction in cell migration (Fig. 4G and H; P<0.05) and invasion

(Fig. 4I and J; P<0.05) was also

demonstrated in cells with downregulated CHMP4C expression, in

comparison with the control cells. Conversely, the plasmid was

transfected in the SiHa and HeLa cells to overexpress CHMP4C and

assess the transfection efficiency of the plasmid using RT-qPCR

(Fig. 5A and B; P<0.05). The

results revealed that, in comparison with the vector control,

overexpression of CHMP4C resulted in a significant increase in cell

proliferation (Fig. 5C and D;

P<0.05) and migration (Fig. 5E and

F; P<0.05), and a significant reduction in the rate of cell

apoptosis (Fig. 5G and H;

P<0.05). The observed changes in phenotype indicate that CHMP4C

acts as a proto-oncogene in cervical cancer cells.

CHMP4C expression is regulated by

E6

The occurrence of cervical cancer is related to HPV

(namely, high-risk HPV16 and HPV18) infection. Viral DNA is

integrated into the host genome to encode oncogenic proteins, such

as E6, which interfere with the cell cycle and apoptosis via

regulation of Bcl2 and Bcl-XL (12–14).

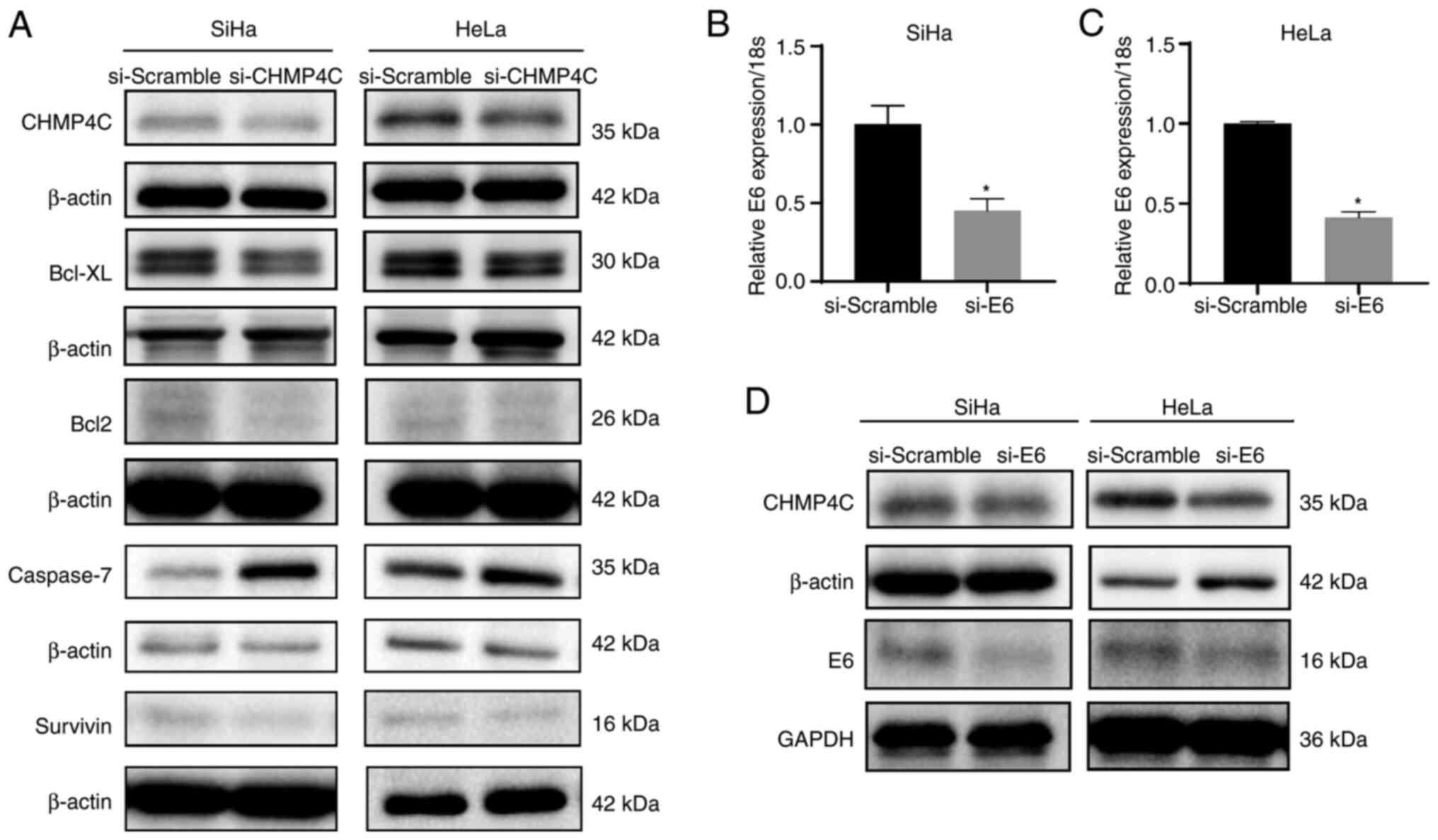

Western blotting showed that the expression of Bcl2, Bcl-xL, and

Survivin was decreased when CHMP4C expression was silenced, but

Caspase-7 expression was increased (Fig. 6A). Therefore, CHMP4C increased the

susceptibility of cervical cancer through the regulation of Bcl2,

Bcl-XL, Survivin and Caspase-7. Furthermore, to determine whether

CHMP4C expression was associated with cervical HPV infection, HPV16

E6 expression was silenced in SiHa cells, and HPV18 E6 expression

was silenced in HeLa cells through siRNA transfection. This

resulted in a significant decrease in the expression of CHMP4C,

compared with the controls (Fig.

6B-D; P<0.05), and demonstrated that HPV infection may lead

to increased expression of CHMP4C.

miR-543 directly targets CHMP4C

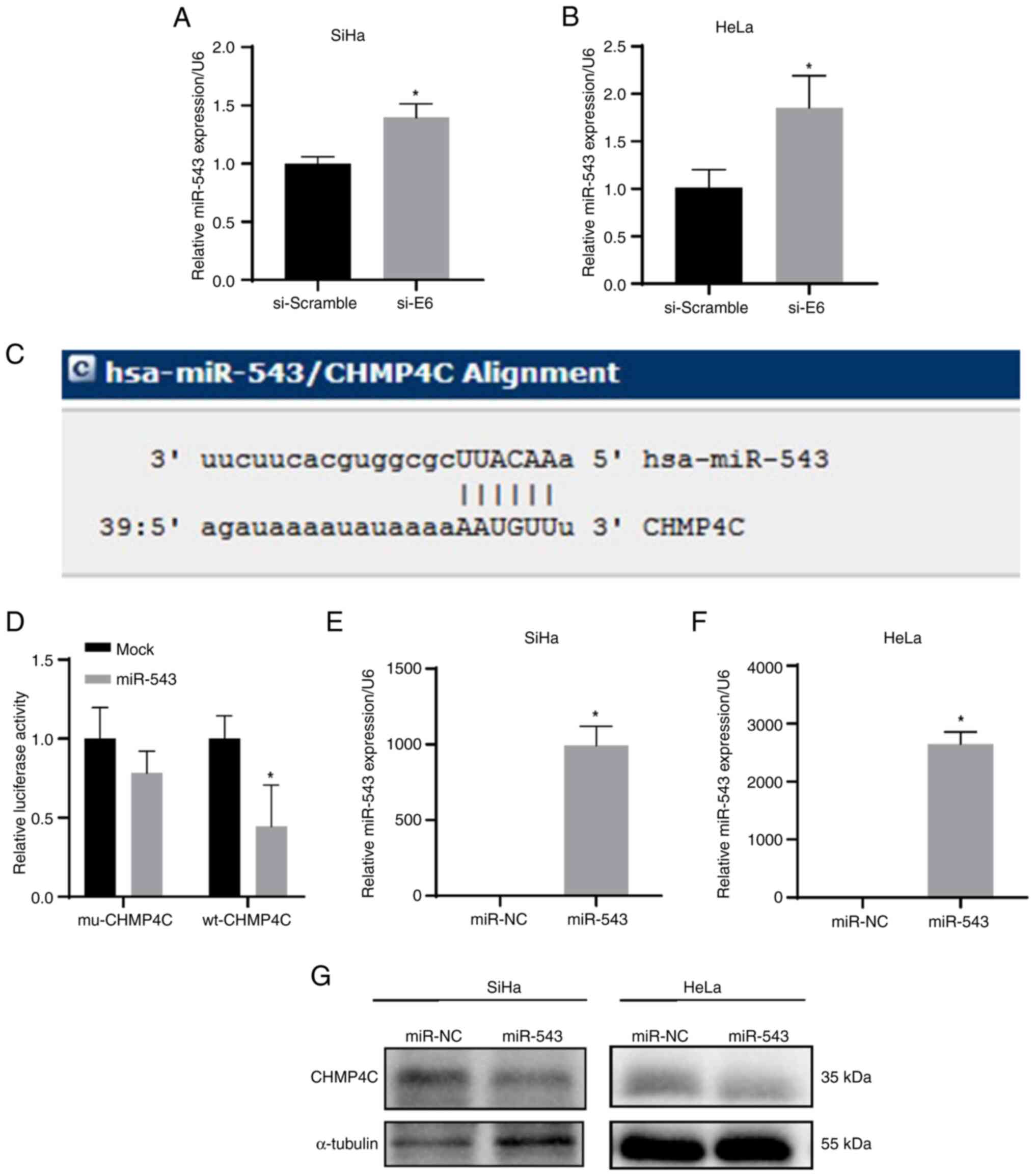

E6 induction of the expression of CHMP4C was

assessed. A previous study reported that E6 could inhibit miR-543

expression in human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) (15). Accordingly, the findings of the

present study demonstrated significant increases in miR-543

expression after E6 siRNA transfection in cervical cancer cells,

compared with that of the controls (Fig. 7A and B; P<0.05). Moreover, the

results of bioinformatics analysis revealed that miR-543 could bind

with the 3′-UTR of CHMP4C (Fig.

7C). In addition, the dual-luciferase reporter assay

demonstrated that the relative luciferase activity was

significantly reduced in the group co-transfected with wild-type

CHMP4C 3′-UTR and miR-543, compared with that of the control groups

(Fig. 7D; P<0.05). These results

imply that miR-543 directly targets the 3′-UTR of CHMP4C.

Furthermore, after overexpression of miR-543 by transfection of the

miR-543 mimics in SiHa and HeLa cells, western blotting indicated

that CHMP4C expression was significantly reduced compared with that

in control cells (Fig. 7E-G;

P<0.05).

Discussion

The abscission checkpoint can inhibit the abscission

of cells with spindle-midzone defects and the lagging chromosomes

promote CHMP4C phosphorylation by Aurora B. This affects its

activity, leading to the failure of cytokinesis (16,17).

It has been reported that radiation induces the expression of

Aurora B and CHMP4C in non-small cell lung cancer cells, thereby

maintaining cell cycle checkpoints and cell viability, and

resisting apoptosis. Inhibition of CHMP4C was reported to promote

the proliferation of cancer cells by inhibiting DNA repair by

reducing phosphorylated H2A histone family member X and p53-binding

protein 1 (53BP1) foci reacting to radiation stress (18). It has also been reported that the

absence of CHMP4C-dependent abscission checkpoints increases the

accumulation of 53BP1-associated DNA damage foci (6). The role of CHMP4C has received

increasing attention in the field of cancer research. Pharoah et

al (19) implicated CHMP4C as

the most likely susceptibility gene candidate in the 8q21 locus of

a new locus associated with the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Moreover, human CHMP4C polymorphisms also increase the risk of

prostate and skin cancer (8).

With regards to the relationship between CHMP4C and

cervical cancer, the immunohistochemistry results of the present

study demonstrated that the expression level of CHMP4C was higher

in cervical cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. Analysis

of the GEPIA database revealed that cervical cancer is associated

with a poor clinical prognosis due to the increased expression of

CHMP4C. Accordingly, in the present study, CHMP4C silencing in SiHa

and HeLa cells resulted in a reduction in the level of cell

proliferation, migration and invasion, and an increase in the rate

of apoptosis. Conversely, CHMP4C overexpression had the opposite

effect on cell proliferation, cell migration and apoptosis. In

addition, silencing of CHMP4C reduced the level of Bcl2, Bcl-XL and

Survivin expression, and increased the expression level of

Caspase-7. The process of apoptosis involves several genes,

including those of the Bcl-2 family, the caspase family and the

inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP) family (20). The Bcl2 protein family is the key to

the regulation and execution of mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic

apoptosis, among which Bcl2 and Bcl-XL belong to a group of

pro-survival proteins (21,22). Moreover, studies have revealed that

the expression of Bcl2 may be associated with the development of

cervical cancer and provide prognostic information (22,23).

Survivin is a member of the IAP family of proteins and inhibits

apoptosis by binding directly to Caspase-3 and Caspase-7 of the

caspase family to inhibit their activity (24). It is overexpressed in many cancers

and serves an important role in promoting tumor cell proliferation,

progression, angiogenesis, therapeutic resistance and poor

prognosis (25). A previous study

also reported that overexpression of CHMP4C in cervical cancer

cells accelerates cell migration and invasion by activating

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (26). The aforementioned results

demonstrate that CHMP4C increases the susceptibility of cervical

cancer and promotes tumorigenesis and progression of cervical

cancer.

Infection with HPV is the underlying cause of

invasive cervical cancer (27–29).

Viral DNA is integrated into the host genome to encode the

oncogenic E6 and E7 proteins. E6 and E7 can interfere with cell

cycle and apoptosis, which are critical factors in cellular

transformation and carcinogenesis (12,13).

Therefore, occurrence of cervical cancer is related to HPV

infection, and CHMP4C increases the susceptibility to cervical

cancer. To determine whether CHMP4C was related to cervical HPV

infection, the present study knocked down E6 expression in cervical

cancer cells and the results revealed that the expression of CHMP4C

was decreased in the E6-knockdown cells. Thus, the E6 protein

encoded by the HPV during cervical infection may regulate CHMP4C

expression.

According to a previous report, miR-543 expression

decreases after HPV16 E6 expression increased in HFKs (15). miRNAs are non-protein-encoding RNAs

with a length of ~21 nucleotides. They inhibit the expression of

their target genes primarily through interaction with the

corresponding 3′-UTR of the mRNA, thereby regulating biological

events, including cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis

(30,31). Moreover, miRNA dysregulation is

associated with the occurrence, development, metastasis and drug

resistance to cancer (32).

Bioinformatics analysis revealed a potential connection site

between the 3′-UTR of CHMP4C and miR-543, and this implies that E6

may regulate CHMP4C expression through miR-543. After E6 was

knocked down in SiHa and HeLa cells, the expression level of

miR-543 was elevated. Meanwhile, elevated miR-543 expression was

associated with reduced CHMP4C expression. Moreover, the

dual-luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that CHMP4C was the

target of miR-543. In addition, studies have reported that miR-543

expression is decreased in cervical cancer, and its expression

level is associated with tumor size, FIGO stage and lymph node

metastasis. In line with the results of the present study, miR-543

is known to inhibit tumor cell proliferation, invasion and

migration, and also promote apoptosis, thereby inhibiting the

development of cervical cancer (33). Based on these findings, we

hypothesize that CHMP4C promotes the progression of cervical cancer

through the HPV E6/miR-543 axis.

In conclusion, the present research indicates that

the HPV-encoded E6 oncoprotein may reduce the expression level of

miR-543 and relieve the inhibitory effect of miR-543 on CHMP4C. By

contrast, high expression level of CHMP4C may inhibit apoptosis by

regulating Bcl2, Bcl-XL, Survivin and Caspase-7 expression, thereby

promoting the tumorigenesis and progression of cervical cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research was supported by Guangdong Medical Science

and Technology Research (grant no. A2023337), the Guangzhou Science

and Technology Project (grant nos. 2024A03J0182 and 2023A03J0375)

and the Clinical High-tech and Major Technology Projects in

Guangzhou (grant no. 2024PL-ZD06).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RCL, YMJ, JH, YPD, YMZ and XJS conceived the study

and wrote the manuscript. RCL, YMJ, JH, YPD and YMZ performed the

experiments. RCL, YMJ and JH analyzed the data. RCL and XJS

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital Guangzhou Medical

University (approval no. 2019-037). Written informed consent was

obtained from all individual participants included in the

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CHMP4C

|

charged multivesicular body protein

4C

|

|

GEPIA

|

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis

|

|

HPV

|

human papillomavirus

|

|

miRNA/miR

|

microRNA

|

|

siRNA

|

small interfering RNA

|

|

3′-UTR

|

3′-untranslated region

|

|

IAP

|

inhibitor of apoptosis proteins

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

World Health Organization (WHO), .

International agency for research on cancer. Global Cancer

Observatory: Cancer Today. WHO; Geneva: 2022, https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/160-china-fact-sheet.pdfMarch

10–2025

|

|

3

|

Bao H, Zhang L and Wang L, Zhang M, Zhao

Z, Fang L, Cong S, Zhou M and Wang L: Significant variations in the

cervical cancer screening rate in China by individual-level and

geographical measures of socioeconomic status: A multilevel model

analysis of a nationally representative survey dataset. Cancer Med.

7:2089–2100. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Small W Jr, Bacon MA, Bajaj A, Chuang LT,

Fisher BJ, Harkenrider MM, Jhingran A, Kitchener HC, Mileshkin LR,

Viswanathan AN and Gaffney DK: Cervical cancer: A global health

crisis. Cancer. 123:2404–2412. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A and Denny

L: Cervical cancer. Lancet. 393:169–182. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jones PA and Baylin SB: The epigenomics of

cancer. Cell. 128:683–692. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Carlton JG, Caballe A, Agromayor M, Kloc M

and Martin-Serrano J: ESCRT-III governs the Aurora B-mediated

abscission checkpoint through CHMP4C. Science. 336:220–225. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sadler JBA, Wenzel DM, Williams LK,

Guindo-Martínez M, Alam SL, Mercader JM, Torrents D, Ullman KS,

Sundquist WI and Martin-Serrano J: A cancer-associated polymorphism

in ESCRT-III disrupts the abscission checkpoint and promotes genome

instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:E8900–E8908. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nikolova DN, Doganov N, Dimitrov R,

Angelov K, Low SK, Dimova I, Toncheva D, Nakamura Y and Zembutsu H:

Genome-wide gene expression profiles of ovarian carcinoma:

Identification of molecular targets for the treatment of ovarian

carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2:365–384. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fujita K, Kume H, Matsuzaki K, Kawashima

A, Ujike T, Nagahara A, Uemura M, Miyagawa Y, Tomonaga T and

Nonomura N: Proteomic analysis of urinary extracellular vesicles

from high Gleason score prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 7:429612017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tommasino M: The human papillomavirus

family and its role in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 26:13–21.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Narisawa-Saito M and Kiyono T: Basic

mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced

carcinogenesis: Roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci.

98:1505–1511. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M,

Wang HG, Lin HK, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B and Reed JC: Tumor

suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in

vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 9:1799–1805. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Harden ME, Prasad N, Griffiths A and

Munger K: Modulation of microRNA-mRNA target pairs by human

papillomavirus 16 oncoproteins. mBio. 8:e02170–16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Norden C, Mendoza M, Dobbelaere J,

Kotwaliwale CV, Biggins S and Barral Y: The NoCut pathway links

completion of cytokinesis to spindle midzone function to prevent

chromosome breakage. Cell. 125:85–98. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Capalbo L, Montembault E, Takeda T, Bassi

ZI, Glover DM and D'Avino PP: The chromosomal passenger complex

controls the function of endosomal sorting complex required for

transport-III Snf7 proteins during cytokinesis. Open Biol.

2:1200702012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li K, Liu J, Tian M, Gao G, Qi X, Pan Y,

Ruan J, Liu C and Su X: CHMP4C disruption sensitizes the human lung

cancer cells to irradiation. Int J Mol Sci. 17:182015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pharoah PD, Tsai YY, Ramus SJ, Phelan CM,

Goode EL, Lawrenson K, Buckley M, Fridley BL, Tyrer JP, Shen H, et

al: GWAS meta-analysis and replication identifies three new

susceptibility loci for ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 45:362–370.

370e1-22013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang Y and Yu X: Regulation of apoptosis:

The ubiquitous way. FASEB J. 17:790–799. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chipuk JE, Moldoveanu T, Llambi F, Parsons

MJ and Green DR: The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol Cell. 37:299–310.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ter Harmsel B, Smedts F, Kuijpers J,

Jeunink M, Trimbos B and Ramaekers F: BCL-2 immunoreactivity

increases with severity of CIN: A study of normal cervical

epithelia, CIN, and cervical carcinoma. J Pathol. 179:26–30. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dimitrakakis C, Kymionis G, Diakomanolis

E, Papaspyrou I, Rodolakis A, Arzimanoglou I, Leandros E and

Michalas S: The possible role of p53 and bcl-2 expression in

cervical carcinomas and their premalignant lesions. Gynecol Oncol.

77:129–136. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shin S, Sung BJ, Cho YS, Kim HJ, Ha NC,

Hwang JI, Chung CW, Jung YK and Oh BH: An anti-apoptotic protein

human survivin is a direct inhibitor of caspase-3 and −7.

Biochemistry. 40:1117–1123. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen X, Duan N, Zhang C and Zhang W:

Survivin and tumorigenesis: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic

strategies. J Cancer. 7:314–323. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lin SL, Wang M, Cao QQ and Li Q: Chromatin

modified protein 4C (CHMP4C) facilitates the malignant development

of cervical cancer cells. FEBS Open Bio. 10:1295–1303. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Crosbie EJ, Einstein MH, Franceschi S and

Kitchener HC: Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet.

382:889–899. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero

R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ and Meijer CJ;

International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical

Cancer Study Group, : Epidemiologic classification of human

papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med.

348:518–527. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, Keys J,

Franceschi S, Winer R and Clifford GM: Human papillomavirus type

distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical

lesions: A meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 121:621–632. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Krol J, Loedige I and Filipowicz W: The

widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay.

Nat Rev Genet. 11:597–610. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Davis BN and Hata A: Regulation of

MicroRNA biogenesis: A miRiad of mechanisms. Cell Commun Signal.

7:182009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Acunzo M, Romano G, Wernicke D and Croce

CM: MicroRNA and cancer-a brief overview. Adv Biol Regul. 57:1–9.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu X, Gan L and Zhang J: miR-543

inhibites cervical cancer growth and metastasis by targeting TRPM7.

Chem Biol Interact. 302:83–92. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|