Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have

revolutionized the therapeutic approach to cancer treatment. These

agents, which include inhibitors targeting programmed cell death

protein 1 (PD-1), its ligand programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, have significantly

improved survival outcomes across various malignancies (1). The KEYNOTE-024 trial demonstrated that

pembrolizumab significantly improved progression-free survival and

overall survival (OS) times compared with chemotherapy in patients

with PD-L1-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

(2). In the CheckMate 067 clinical

trial, patients with advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab plus

ipilimumab demonstrated durable responses, with a median OS time of

72.1 months (3). However, ICIs can

induce severe immune-mediated toxicities, referred to as

immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which can affect the

functionality of various organ systems, including ICI-related

colitis, pneumonitis, myositis, dermatological toxicity and

endocrine toxicity, among others (4). Although endocrine irAEs occur less

frequently (10–18%) than dermatological (25–70%) or

gastrointestinal (50%) toxicities, they can be severe and, in some

cases, irreversible (5,6). Among these endocrine irAEs,

ICI-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus (ICI-T1DM) is a rare (<1%)

(7) but potentially

life-threatening complication characterized by sudden-onset

hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency, and frequently presenting

with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (8–10). The

present study reports the case of a female patient diagnosed with

lung invasive adenocarcinoma who developed ICI-T1DM during

durvalumab therapy. This case highlights the importance of the

early recognition and management of this rare yet critical adverse

event, while also providing insights into its clinical

presentation, diagnostic challenges and potential underlying

mechanisms.

Case report

Patient

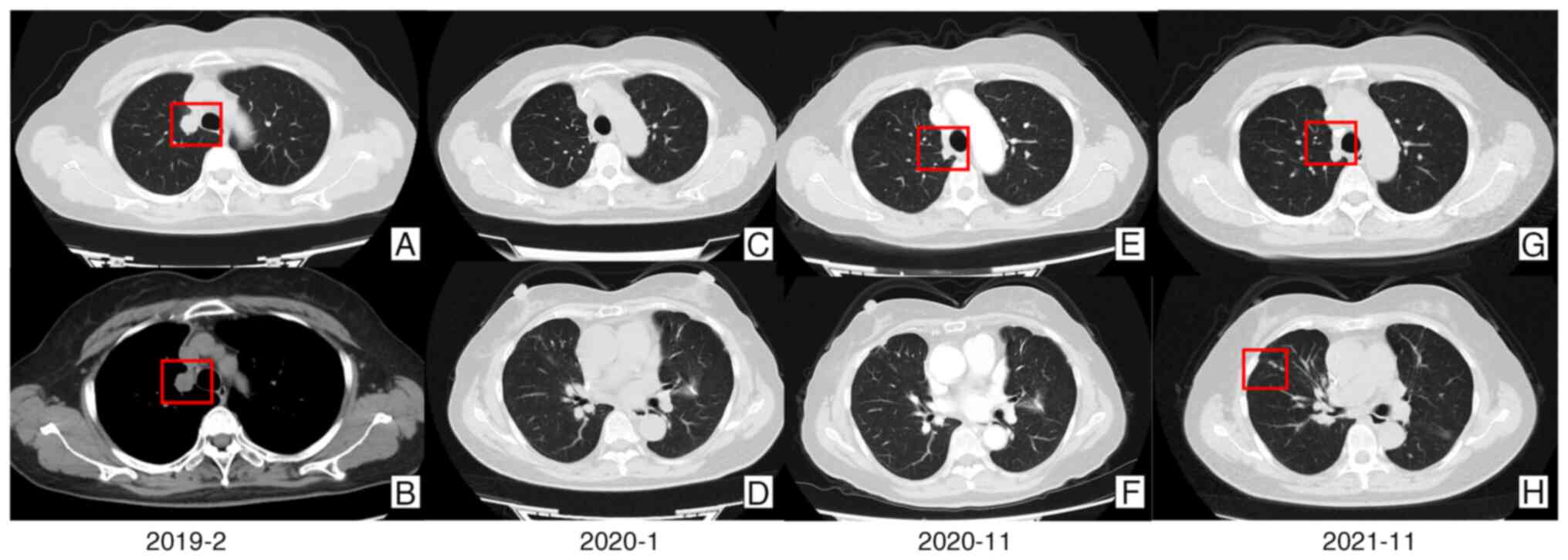

The patient, a 62-year-old woman with no prior

history of diabetes, was asymptomatic and diagnosed with lung mass

lesions by chest computed tomography during a routine health

examination (CT) (Fig. 1A and

1B) at China-Japan Friendship

Hospital (Beijing, China) in January 2019. In February 2019, the

patient underwent a right upper lobectomy and left upper lobe wedge

resection. Histopathological examinations confirmed invasive

adenocarcinoma in the upper lobe of the right lung, diagnosed as

stage pT2N0M0 IB according to the 8th edition of the International

Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Tumor-Node-Metastasis

classification (11), without

detectable gene mutations. Additionally, an invasive adenocarcinoma

in the left upper lobe was diagnosed as stage pT1N0M0 IA with an

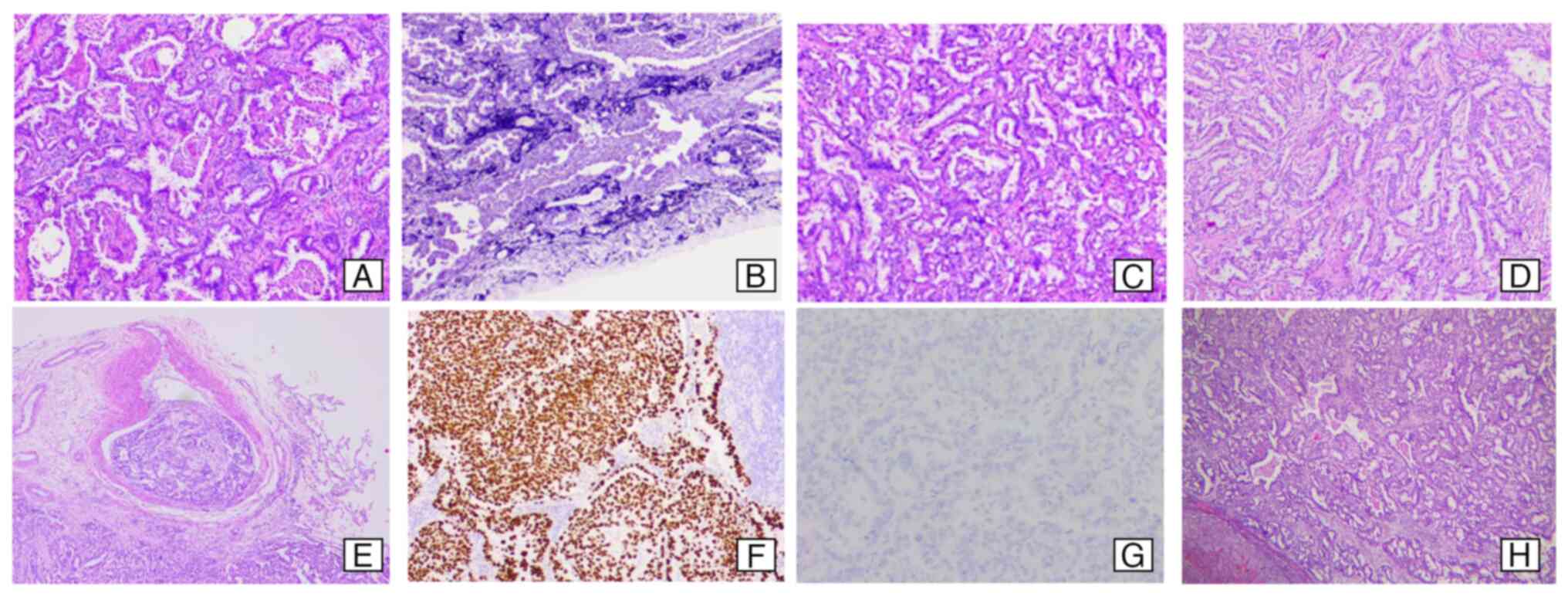

EGFR21 mutation. The histopathological and immunohistochemical

images of the patient tissues are shown in Fig. 2A-G. H&E-stained sections

revealed invasive adenocarcinoma with vascular tumor thrombi.

Elastic fiber staining indicated destruction of the pleural elastic

lamina. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression was positive,

while anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative. Targeted therapy

with gefitinib was initiated in early March 2019, with oral

administration of 250 mg once daily. In late September 2019, a left

adrenal tumor resection was performed, with histopathological

examinations (Fig. 2H) revealing

lung adenocarcinoma metastasis without detectable gene mutations.

Following the recurrence of the invasive adenocarcinoma, the

patient received three cycles (21-day cycles) of chemotherapy with

pemetrexed (800 mg on day 1), carboplatin (400 mg on day 2) and

bevacizumab (400 mg on day 1), between November 2019 and ~60 days

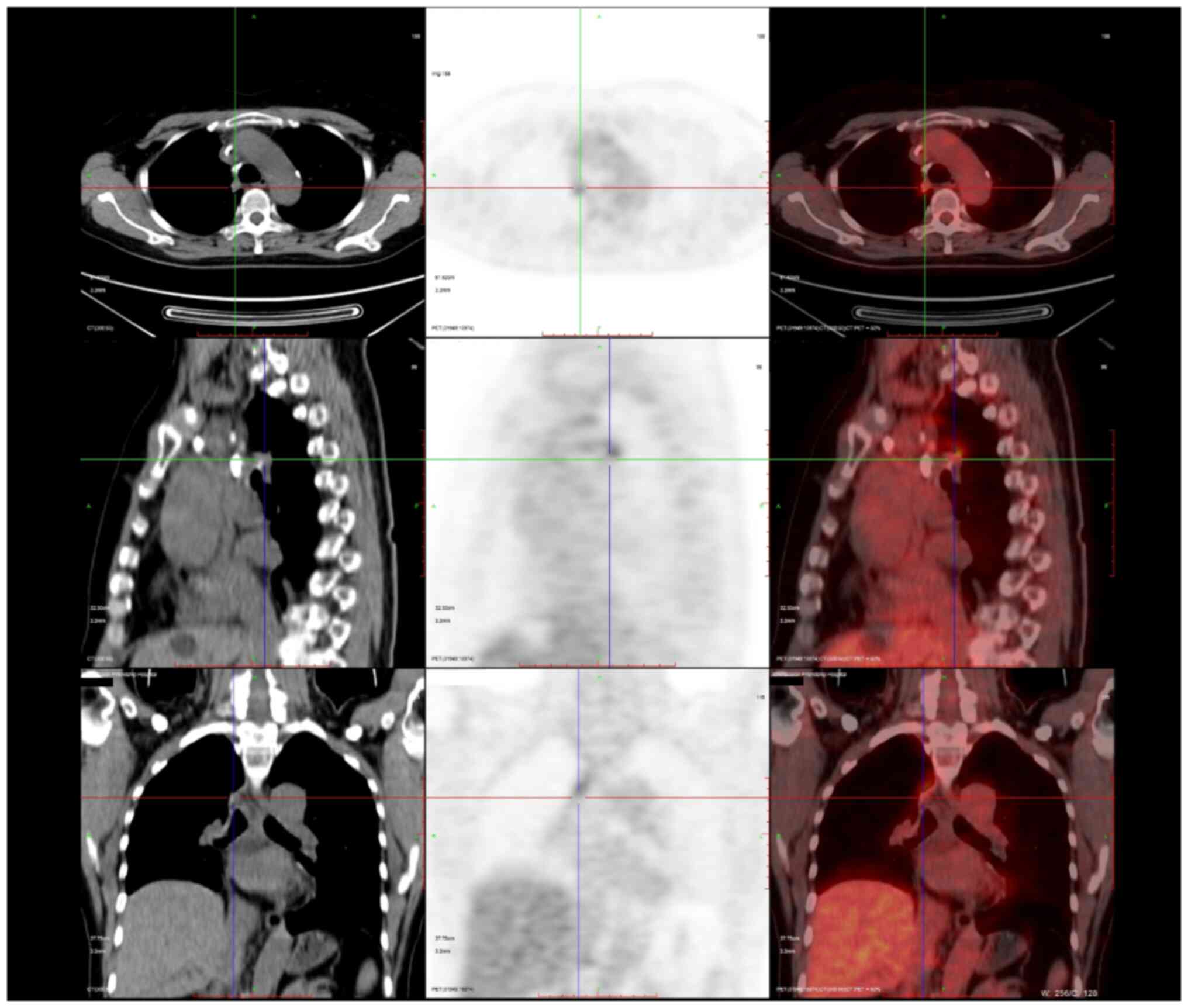

thereafter. In October 2020 and November 2020, positron emission

tomography-CT (Fig. 3) and enhanced

chest CT scans (Fig. 1E and F),

respectively, showed the recurrence of the malignancy in the right

upper hilum. Consequently, the patient was administered 4–6 cycles

(21-day cycles) of the following regimen between November 2020 and

~60 days thereafter: Nedaplatin (120 mg on day 1), pemetrexed (800

mg on day 2) and bevacizumab (400 mg on day 2). After December

2020, the patient opted for gefitinib maintenance therapy (250 mg

once daily). However, in November 2021, a CT scan showed that the

disease had progressed (Fig. 1G and

H). No pathogenic gene mutations were detected.

Subsequently, on November 2021 and 27 days later,

the patient received 1–2 cycles of second-line chemotherapy

combined with immunotherapy involving nedaplatin (120 mg on day 1),

albumin paclitaxel (200 mg on day 8), bevacizumab (400 mg on day 1)

and durvalumab (1,000 mg on day 1). Each cycle lasted 21 days.

After experiencing thirst, polydipsia and polyuria since the end of

December 2021, the patient sought timely medical attention in

January 2022. Given the symptoms and the potential diagnosis of

diabetes, a consultation with the Department of Endocrinology was

requested for further evaluation. The laboratory abnormalities are

shown in Table I. Laboratory tests

revealed significantly elevated fasting and postprandial blood

glucose levels as follows: Fasting plasma glucose, 17.70 mmol/l;

and 2-h postprandial blood glucose, 30.28 mmol/l. The glycated

hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 7.3%. Additionally, the patient's

C-peptide level was low and the glutamic acid decarboxylase

antibody (GADab) test was positive (35.02 IU/ml), indicating T1DM.

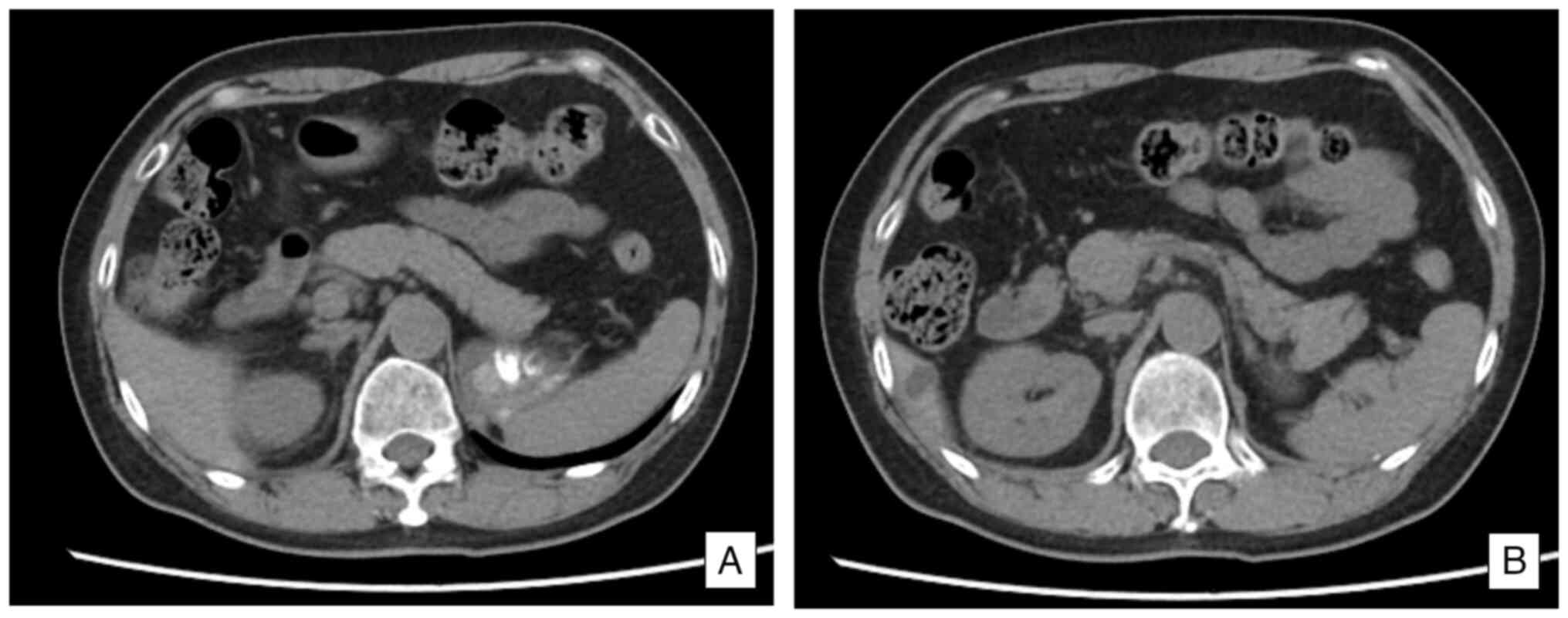

A CT scan (Fig. 4) showed that the

size and morphology of the pancreas were within normal limits, and

the surrounding adipose tissue appeared clear.

| Table I.Laboratory results. |

Table I.

Laboratory results.

| Laboratory

parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|

| Oral glucose

tolerance test |

|

|

| Fasting

blood-glucose, mmol/l | 17.70 | 3.61–6.11 |

| Glucose

(1 h), mmol/l | 24.56 | <11.10 |

| Glucose

(2 h), mmol/l | 30.28 | <7.84 |

| Insulin release

test |

|

|

| IRI (0

h), µIU/ml | 3.96 | 2.6–24.9 |

| CPS (0

h), ng/ml | 0.96 | 1.1–4.4 |

| IRI (1

h) µIU/ml | 4.14 | 2.6–24.9 |

| CPS (1

h) ng/ml | 0.96 | 1.1–4.4 |

| IRI (2

h) µIU/ml | 4.92 | 2.6–24.9 |

| CPS (2

h) ng/ml | 1.11 | 1.1–4.4 |

| Other blood

laboratory results |

|

|

|

Glycated hemoglobin, % | 7.3 | 4.0–6.0 |

|

Glutamic acid decarboxylase

antibody, IU/ml | 35.02 | <10 |

| Islet

antigen 2 antibody, IU/ml | <0.7 | <10 |

| ALT,

IU/l | 93 | 0-40 |

| AST,

IU/l | 58 | 0-42 |

|

α-amylase, IU/l | 108 | 28-100 |

| Lipase,

U/l | 34 | 0-67 |

| Urine laboratory

results |

|

|

| Urine

routine glucose | Negative |

|

| Ketone

bodies | Negative |

|

Based on the medical history of the patient and the

treatment regimen, the patient was diagnosed with ICI-T1DM

(12). Subsequently, immunotherapy

was discontinued, and the patient was put on insulin replacement

therapy, consisting of insulin degludec/aspart (15 IU

subcutaneously twice daily) as basal insulin and insulin aspart (15

IU subcutaneously as needed) for prandial coverage. Dosages were

titrated according to real-time blood glucose measurements obtained

through capillary blood glucose monitoring. After treatment, the

patient's fasting blood sugar was maintained within the 5.9–7.5

mmol/l range (normal range, 3.61–6.11 mmol/l). Postprandial levels

were as follows: After breakfast, 7.3–11 mmol/l; after lunch,

6.7–8.9 mmol/l; and after dinner, 8.4–10.7 mmol/l (normal range,

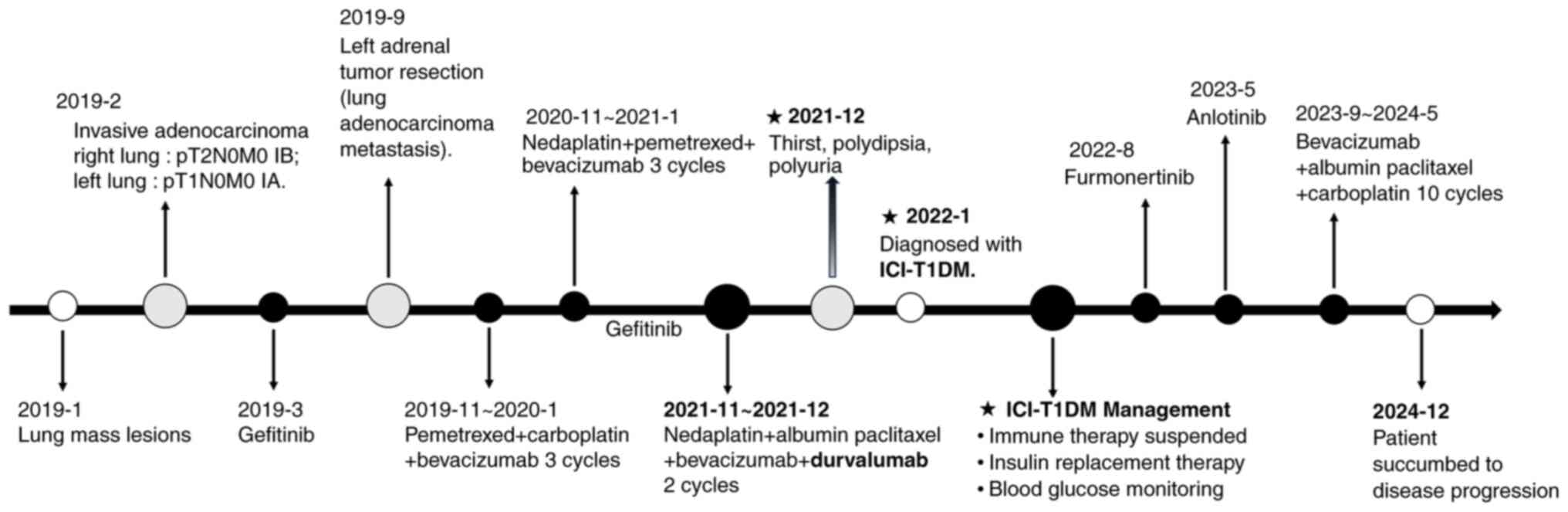

<11.1 mmol/l). A graphical timeline illustrating the patient's

treatment history, durvalumab exposure and the onset of diabetes is

shown in Fig. 5. The patient

resumed anticancer therapy in August 2022 with oral furmonertinib

(80 mg once daily). Monthly follow-ups were conducted at the

Department of Integrative Oncology in the China-Japan Friendship

Hospital. Due to disease progression, the treatment regimen was

subsequently modified to anlotinib (12 mg once daily on days 1–14,

every 21 days), followed by bevacizumab (300 mg on day 1) in

combination with albumin paclitaxel (200 mg on day 1 and 100 mg on

day 8) and carboplatin (300 mg on day 1), administered every 21

days. Ultimately, the patient succumbed to disease progression in

December 2024.

Methods

Tissue staining

Specimens were fixed for 24 to 48 h in 10%

neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature and embedded in

paraffin. The tissue blocks were sliced into 4- or 5-µm thick

sections. H&E staining was performed using hematoxylin for 10

min and eosin for 5 min at room temperature. The elastic fibers

were stained using the iron hematoxylin method, also at room

temperature. 5% Ethanol hematoxylin, 10% ferric chloride and

Verhoeff's iodine solution were mixed at a ratio of 20:8:8 drops,

and then dropped onto the tissue section. Counterstaining was

performed with eosin for 2 min.

Immunohistochemistry was performed by EnVision

system. Antigen retrieval was performed using high pressure at

120°C for 5 min, and endogenous enzyme activity was blocked with 3%

H2O2 for 10 min. The primary antibodies were

ALK (clone D5F3; catalogue number, K18082; Roche Diagnostics) and

TTF-1 (clone SPT24; catalogue number, 18092706; OriGene

Technologies, Inc.), both with a dilution ratio of 1:200, incubated

at room temperature for 1 h. The secondary antibody was horseradish

peroxidase labeled polymer (dilution ratio, 1:2,000; catalogue

number, M00855-M01010; Roche Diagnostics), incubated at 37°C for 30

min. Next, DAB was used for color development, and hematoxylin was

used for counterstaining for 10 min. All sections were observed

using a light microscope.

Literature review

To contextualize this case, a literature review was

conducted in the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The following search

strategy was used: [‘Lung Neoplasms’(Mesh) OR ‘Lung Cancer’ OR

‘NSCLC’ OR ‘SCLC’] AND (‘Nivolumab’ OR ‘Pembrolizumab’ OR

‘Atezolizumab’ OR ‘Durvalumab’) AND (‘Type 1 Diabetes’ OR ‘T1DM’)

AND [‘Case Reports’(Publication Type) OR ‘case report’ OR ‘case

series’]. The literature search was conducted on August 15, 2023,

covering all eligible articles from database inception to the

search date. Inclusion criteria were as follows: Case reports or

case series with a clear diagnostic basis confirming patients with

ICI-T1DM. Exclusion criteria included non-peer-reviewed literature

(e.g., preprints and conference abstracts), case reports with

incomplete data and articles for which the full text was

unavailable. This literature review aimed to collect case reports

of ICI-T1DM associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in patients

with lung cancer. After data retrieval, a total of 25 case reports

involving 27 patients were identified (13–37).

The author, year, patient's age and sex, medical history,

pathological type, ICIs administered, time of disease onset,

symptoms, blood glucose levels, HbA1c percentage, GADab status,

insulinoma-associated antigen 2 antibody (IA-2ab) status,

pancreatic enzyme levels, whether the condition presented with DKA

and treatment modalities, among other parameters. Key clinical

characteristics, including onset time, symptoms and treatment, are

summarized in Table II. The

corresponding information of the patient in this study is also

provided in Table II for

comparison purposes.

| Table II.ICI-T1DM caused by

anti-PD-1/anti-programmed death ligand 1 treatment in lung

cancer. |

Table II.

ICI-T1DM caused by

anti-PD-1/anti-programmed death ligand 1 treatment in lung

cancer.

| First author | Year | Age at

diagnosis | Sex | Type of tumor | History of

diabetes | ICIs | Onset time of

ICI-T1DM | Clinical symptoms

at onset | Blood glucose,

mmol/l | HbA1c% | DKA occurrence | GADab

positivity | IA-2ab

positivity | Pancreatic enzyme

levels | Treatment | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Alrifai, et

al | 2019 | 69 | Male | NSCLC | T2DM | Pembrolizumab | 4 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Nausea, vomiting,

polyuria, polydipsia, weakness | 50.4 | 9.20 | Yes | (+) | No data | No data | Insulin, insulin +

metformin | (13) |

| Capitao, et

al | 2018 | 74 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Nivolumab | 25 days | Polyuria,

polydipsia, weight loss, vomiting, confusion, asthenia | 58.9 | 8.70 | Yes | (+) | No data | Lipase and amylase

increased | Insulin | (14) |

| Chae, et

al | 2017 | 76 | Male | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Pembrolizumab | 2 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Asymptomatic | 34.2 | 6.30 | No | (+) | (+) | No data | Insulin | (15) |

| Chaudry, et

al | 2020 | 75 | Male | NSCLC | (−) | Pembrolizumab | 4 cycles (no cycle

length mentioned) | Fatigue, severe

nausea, weight loss | 35.7 | No data | Yes | (+) | No data | No data | Insulin | (16) |

| Cunha, et

al | 2022 | 59 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Pembrolizumab | 3 weeks | Polyuria,

polydipsia, weight loss | 30.8 | 5.60 | Yes | (+) | No data | (−) | Insulin | (17) |

| de Filette, et

al | 2019 | 61 | Male | NSCLC | (−) | Pembrolizumab | 8 weeks | Nausea, vomiting,

diarrhea, generalized weakness | 66.3 | No data | Yes | (+) | (−) | Lipase

increased | Insulin | (18) |

| Delasos, et

al | 2021 | 77 | Male | High-grade

neuroendocrine tumor | (−) | Nivolumab | 15 cycles (14 days

per cycle) | Fatigue, polyuria,

polydipsia | 44.5 | 8.30 | Yes | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (19) |

| Edahiro, et

al | 2019 | 61 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Pembrolizumab | 8 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Emesis, general

malaise, thirst | 31.8 | 8.40 | Yes | (−) | No data | No normal reference

range | Insulin | (20) |

| Godwin, et

al | 2017 | 34 | Female | NSCLC | (−) | Nivolumab | 2 cycles (no cycle

length mentioned) | Abdominal pain,

nausea, weakness | 41.1 | 7.10 | Yes | (+) | (+) | No data | Insulin | (21) |

| Hatakeyama, et

al | 2019 | 60 | Male | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Nivolumab | 36 cycles (14 days

per cycle) | Asymptomatic | 23.1 | 9.10 | No | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (22) |

| Huang, et

al | 2021 | 59 | Male | SCLC | (−) | Sintilimab | 6 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Polyuria,

polydipsia | 25.0 | 7.40 | Yes | No data | No data | No data | Insulin | (23) |

| Ishi, et

al | 2021 | 51 | Male | Large cell

carcinoma | T2DM | Nivolumab | 14 cycles (no cycle

length mentioned) | Not mentioned | 57.8 | 6.90 | Yes | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (24) |

|

|

| 62 | Male | SCC | (−) | Atezolizumab | 15 days | Thirst, vomiting,

high fever | 21.9 | 8.90 | No | No data | No data | No data | Insulin +

antibiotics |

|

| Kedzior, et

al | 2021 | 51 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | Not mentioned | Pembrolizumab | 2 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Abdominal pain,

diarrhea, vomiting, fatigue, dizziness | 62.4 | 8.30 | Yes | (+) | No data | No data | Insulin +

steroid | (25) |

| Lee, et

al | 2018 | 67 | Male | SCC | T2DM | Nivolumab | 2 weeks | Lethargy, polyuria,

polydipsia | 28.6 | 7.60 | Yes | (+) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (26) |

| Li, et

al | 2017 | 63 | Male | SCC | (−) | Nivolumab | 27 days | Palpitations,

fatigue | 32.9 | 7.20 | Yes | (+) | No data | No data | Insulin | (27) |

| Li, et

al | 2020 | 73 | Male | NSCLC | (−) | Anti PD-1 | 10 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Vomiting, dizzy

tachypnea | 51.0 | 7.60 | Yes | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (28) |

| Lupi, et

al | 2019 | 60 | Male | Lung

adenocarcinoma | Not mentioned | Atezolizumab | 4 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Not mentioned | 10 (during

L-thyroxine therapy) | No data | Yes | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin,

hydrocortisone, fludrocortisone | (29) |

| Nishioki, et

al | 2020 | 73 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Atezolizumab | >4 months | Dysarthria, gait

disorder, fatigue, vomiting | 53.4 | 7.30 | Yes | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (30) |

| Patel, et

al | 2019 | 49 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Durvalumab | 3 months | Lethargy, polyuria,

polydipsia, blurred vision | 21.9 | 7.80 | Yes | (+) | No data | No data | Insulin | (31) |

| Porntharukchareon,

et al | 2020 | 70 | Male | NSCLC | Not | Pembrolizumab +

mentioned | 14 weeks

ipilimumab | Fatigue, nausea,

vomiting | 44.1 | 6.50 | Yes | (−) | (−) | (−) | Insulin | (32) |

| Ren, et

al | 2022 | 71 | Female | SCLC | (−) | Durvalumab | 7 months | Asymptomatic | 13.9 | 9.80 | No | (−) | (−) | (−) | Insulin | (33) |

|

|

| 61 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | Not mentioned | Pembrolizumab | 6 weeks | Vomiting,

difficulty breathing, coma | 29.8 | No data | Yes | No data | No data | No data | Insulin |

|

| Seo, et

al | 2022 | 74 | Male | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Nivolumab | 8 months | Lower stomach

discomfort, dysarthria, gait disturbance, lethargy, vomiting | 41.0 | 10.60 | Yes | (−) | (+) | No data | Insulin | (34) |

| Sothornwit, et

al | 2019 | 52 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Atezolizumab | 24 weeks | Not mentioned | 18.4 | 7.90 | Yes | (+) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (35) |

| Tzoulis, et

al | 2018 | 56 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Nivolumab | 3 cycles (14 days

per cycle) | Polyuria,

polydipsia, disorientated, agitated, combative | 47.0 | 8.20 | Yes | (+) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (36) |

| Yang, et

al | 2022 | 78 | Female | SCLC | (−) | Sintilimab | 14 cycles (no cycle

length mentioned) | Polyuria,

polydipsia | 23.4 | 8.20 | No | (−) | (−) | No data | Insulin | (37) |

| Present study |

| 62 | Female | Lung

adenocarcinoma | (−) | Durvalumab | 2 cycles (21 days

per cycle) | Thirst, polydipsia,

polyuria | 17.70 | 7.30 | No | (+) | (−) | Amylase

increased | Insulin |

|

The PubMed database was systematically reviewed to

identify case reports of ICI-T1DM, selecting studies based on

predefined criteria, including confirmed diagnosis and documented

clinical course. The analysis indicated that early-onset cases are

more frequently associated with pancreatic autoantibody positivity

and that PD-1 inhibitors may be linked to a higher incidence of

ICI-T1DM compared with PD-L1 inhibitors. Nearly one-half of the

patients (48.15%) tested positive for GADab. Notably, two patients

with positive GADab and IA-2ab developed ICI-T1DM during the second

cycle. However, further studies are needed to validate these

trends. Collectively, most of the 27 patients were diagnosed with

non-small cell lung cancer. Additionally, 23 patients presented

with a median HbA1c level of 7.90% (mean, 7.95%; range,

5.60–10.60%). Vomiting and polydipsia were the most common,

followed by fatigue, polyuria and consciousness disorder (lethargy,

coma and confusion). Approximately 81.48% of the patients presented

with DKA at the first diagnosis. Statistical analysis was performed

using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp.). The normality of quantitative

data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed

data were compared between groups with independent samples t-tests,

while non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the

Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were examined with

χ2 or Fisher's exact tests. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. The results

revealed that there was no significant association between GADab

and blood glucose levels (P=0.462) or the occurrence of DKA

(P=0.560). However, GADab positivity was significantly associated

with the onset timing of new-onset ICI-T1DM (P=0.005). The

characteristics of the 27 patients are summarized in Table III.

| Table III.Data analysis of 27 patients from the

literature review. |

Table III.

Data analysis of 27 patients from the

literature review.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Median age,

years | 62 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

Male | 15 (55.56) |

|

Female | 12 (44.44) |

| Disease type, n

(%) |

|

|

SCLC | 3 (11.11) |

|

NSCLC | 24 (88.89) |

| History of

diabetes, n (%) |

|

|

T2DM | 3 (11.11) |

|

Negative | 20 (74.07) |

| Not

mentioned | 4 (14.81) |

| ICIs, n (%) |

|

|

Pembrolizumab | 8 (29.63) |

|

Nivolumab | 9 (33.33) |

|

Sintilimab | 2 (7.41) |

|

Atezolizumab | 4 (14.81) |

|

Durvalumab | 2 (7.41) |

| ≥2

types | 1 (3.70) |

| Not

clear | 1 (3.70) |

| Time of onset of

illness, n (%)a |

|

| ≤2

months | 10 (37.04) |

| >2

months | 17 (62.96) |

| Symptoms, n

(%) |

|

|

Vomiting | 11 (40.74) |

|

Polydipsia | 11 (40.74) |

|

Fatigue | 10 (37.04) |

|

Polyuria | 9 (33.33) |

|

Consciousness disorder | 6 (22.22) |

|

Nausea | 5 (18.52) |

| Weight

loss | 3 (11.11) |

|

Abdominal pain | 2 (7.41) |

|

Diarrhea | 2 (7.41) |

| DKA, n

(%)b |

|

|

Yes | 22 (81.48) |

| No | 5 (18.52) |

| Mean HbA1c, % | 7.95 |

| Mean blood glucose,

mmol/lb | 38.83 |

| Antibodies, n

(%) |

|

|

GADab+ | 13 (48.15) |

|

IA-2ab+ | 3 (11.11) |

Despite these novel observations, this literature

review has certain limitations. First, given that this study is

based on case reports, characterized by a small sample size and

lack of a control group, the generalizability of the findings is

limited. Second, variations in diagnostic criteria and follow-up

durations across the included reports introduce potential

heterogeneity, which poses significant challenges to the

interpretation of the results. Additionally, since case reports are

retrospective studies, certain clinical parameters may lack

standardized definitions across different studies. Consequently,

future research should focus on conducting larger-scale cohort

studies, establishing standardized diagnostic criteria and

extending follow-up durations to validate our findings and provide

more reliable clinical guidance.

Discussion

The patient in this study had no prior history of

diabetes or hyperglycemia during previous cancer treatments.

However, after immunotherapy, the patient showed an elevated blood

glucose level, islet dysfunction (with serum C-peptide below the

normal range) and absolute insulin deficiency, among other

complications. These observations exhibited a positive temporal

association with durvalumab. The likelihood of this event was

assessed using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale

(38), which yielded a score of 6,

which indicates a probable relationship. Additionally, according to

a previous report, the incidence of new-onset diabetes associated

with ICIs in patients exposed to PD-L1 inhibitors alone was 0.73%

(8). New-onset diabetes is a rare

adverse effect of durvalumab, occurring in only 0.2% of cases

(39). Among the 27 patients

included in this review, only 2 received durvalumab. All the

patients exhibited a history of ICI treatment. Vomiting and

polydipsia are the most common symptoms (13,14,18,24,30,33,34,40).

The initial symptoms experienced by this patient included thirst,

polydipsia and polyuria without vomiting. Additionally, compared

with the 81.48% of patients who developed DKA, as presented in

Table II, the current patient did

not present with DKA at the time of diagnosis, likely due to the

early recognition of symptoms and timely medical consultation.

Notably, ICI-T1DM is a distinct subtype of T1DM,

primarily triggered by pancreatic β-cell destruction due to ICI

therapy (41). Under normal

physiological conditions, the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway protects

pancreatic β-cells from immune cell toxicity by inducing T-cell

apoptosis. However, previous studies have shown that ICI therapy

disrupts the interaction between PD-L1 molecules on pancreatic

β-cells and PD-1 receptors on autoreactive T cells, thereby

inhibiting their binding (42).

Consequently, autoreactive T cells evade elimination and damage

β-cells. Therefore, PD-1 inhibition leads to T-cell activation and

subsequent destruction of pancreatic β-cells. During this process,

CD8+ T cells function as the primary effector cells.

Previous studies on the pancreatic pathology of patients with

ICI-T1DM have shown an increase in CD8+ T cells and a

reduction in the macrophage population (43–46).

Research indicates that activated autoreactive T cells respond to

PD-1 inhibition by releasing interferons (IFNs). These IFNs

activate monocyte-derived macrophages (44). When treated with anti-PD-L1,

cytotoxic IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells infiltrate the

islets and induce the dedifferentiation of pancreatic β-cells

(45). These T cells utilize nitric

oxide to kill pancreatic β-cells, leading to insulin deficiency and

the development of ICI-T1DM. This condition, ICI-T1DM, presents

with distinct clinical manifestations, disease features and

pathogenic factors compared to the traditional T1DM, therefore it

warrants differentiation clinically (47). The incidence of DKA in ICI-T1DM is

higher compared with that in traditional T1DM, and its presence is

frequently associated with other irAEs (44,48).

Additionally, in the case of ICI-T1DM, there is no spontaneous

remission period (49). Moreover,

there are inducements of pancreatic autoimmunity before the onset

of ICI-T1DM. Patients with ICI-T1DM may also exhibit elevated

trypsin levels (50,51).

GADab and IA-2ab are biomarkers of pancreatic

autoimmunity and potentially play significant roles in predicting

ICI-T1DM. GADab is an enzyme involved in the synthesis of the

neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid and is also a major pancreatic

islet autoantibody (52). GADab is

the most commonly used diagnostic marker for adult T1DM. In

ICI-T1DM, the interval between the initiation of anti-PD-1/PD-L1

antibody treatment and the onset of ICI-T1DM is associated with the

presence or absence of GADab (52).

The literature review indicated that the onset of ICI-T1DM in

patients with positive GADab results was earlier, ~2 months on

average, compared with the onset in patients with negative results

for the pancreatic islet antibody (52). These observations are consistent

with the present case report, in which the patient was

GADab-positive and the onset time was within 6 weeks. IA-2ab is

also an important marker of pancreatic autoimmunity. Studies have

shown that IA-2ab is present in ~60% of patients with newly

diagnosed T1DM (53). However, in

ICI-T1DM, the significance of IA-2ab is less pronounced compared

with that of GADab. A systematic review revealed that 18% of

patients with ICI-T1DM tested positive for IA-2ab, compared with

51% for GADab (18). In another

retrospective analysis involving 10 patients with ICI-T1DM, IA-2ab

levels were found to be within the normal range (54). This suggests that the predictive

role of IA-2ab in ICI-T1DM requires further investigation. A study

revealed that at least one pancreatic autoantibody was positive in

53% of patients with ICI-T1DM, and two or more autoantibodies were

detected in 15% of patients (18).

Therefore, pancreatic autoantibody serological testing may be

conducted before the initiation of ICI therapy to help predict the

onset of ICI-T1DM.

Given the absence of typical clinical symptoms and

reliable predictors for ICI-T1DM, as well as the life-threatening

risks associated with rapid onset and delayed treatment, clinicians

must remain vigilant. Regular blood glucose monitoring is

essential, and when elevated blood sugar levels are detected, a

timely and accurate differential diagnosis should be made in

conjunction with endocrinologists. Following an accurate diagnosis

of ICI-T1DM, immunosuppressant administration should be

discontinued and replaced with insulin replacement therapy.

Currently, it is believed that the occurrence of ICI-T1DM does not

contraindicate the continuation of ICI therapy, provided that blood

glucose levels can be effectively controlled through insulin

therapy. Therefore, the treatment and follow-up of diabetes should

be continued after the temporary cessation of ICI treatment.

Decisions regarding temporary interruption or permanent

discontinuation of ICI therapy must be guided by an individualized

risk-benefit assessment. Furthermore, the decision to restart ICI

therapy after achieving stable blood glucose control should be made

collaboratively by oncologists and endocrinology experts.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by National High-Level Hospital Clinical

Research Funding (grant no. 2022-NHLHCRF-LX-02-0111), Capital's

Funds for Health Improvement and Research (grant no. 2022-2-4065)

and Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and

Technology Major Project (grant no. 2023ZD0502503).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HD and SL participated in study design and wrote the

original manuscript draft. XZ, JZ, YP and XL obtained medical

images and analyzed patient data. CX, YZ and YY analyzed

pathological images and made the diagnosis. ZH contributed to the

follow-up and data analysis. YP participated in language revision

of the manuscript. HC was involved in drafting the manuscript,

revising it critically for important intellectual content, data

analysis and giving final approval of the version to be published.

HD and SL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript, and

subsequently, the authors revised and edited the content produced

by the AI tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript

References

|

1

|

Arafat Hossain M: A comprehensive review

of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment. Int

Immunopharmacol. 143:1133652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG,

Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe

S, et al: Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive

non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 375:1823–1833. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R,

Grob JJ, Rutkowski P, Lao CD, Cowey CL, Schadendorf D, Wagstaff J,

Dummer R, et al: Long-term outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab

or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab in patients with advanced

melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 40:127–137. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Darnell EP, Mooradian MJ, Baruch EN,

Yilmaz M and Reynolds KL: Immune-related adverse events (irAEs):

Diagnosis, management, and clinical pearls. Curr Oncol Rep.

22:392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kottschade LA: Incidence and management of

immune-related adverse events in patients undergoing treatment with

immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Oncol Rep. 20:242018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Elshafie O, Khalil AB, Salman B, Atabani A

and Al-Sayegh H: Immune checkpoint Inhibitors-induced

endocrinopathies: Assessment, management and monitoring in a

comprehensive cancer centre. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab.

7:e005052024. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wright JJ, Powers AC and Johnson DB:

Endocrine toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 17:389–399. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Liu J, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Fang W, Yang Y,

Huang Y and Zhang L: Reporting of immune checkpoint inhibitor

therapy-associated diabetes, 2015–2019. Diabetes Care. 43:e79–e80.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Marchand L, Thivolet A, Dalle S, Chikh K,

Reffet S, Vouillarmet J, Fabien N, Cugnet-Anceau C and Thivolet C:

Diabetes mellitus induced by PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: Description

of pancreatic endocrine and exocrine phenotype. Acta Diabetol.

56:441–448. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Błażowska O, Stróżna K, Dancewicz H,

Zygmunciak P, Zgliczyński W and Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska B: The

Double-edged sword of Immunotherapy-Durvalumab-induced

Polyendocrinopathy-case report. J Clin Med. 13:63222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J,

Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P,

Mitchell A, Bolejack V, et al: The IASLC lung cancer staging

project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the

forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung

cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 11:39–51. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J,

Andrews S, Armand P, Bhatia S, Budde LE, Costa L, Davies M,

Dunnington D, et al: NCCN guidelines insights: Management of

Immunotherapy-related toxicities, version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc

Netw. 18:230–241. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Alrifai T, Ali FS, Saleem S, Ruiz DCM,

Rifai D, Younas S and Qureshi F: Immune checkpoint inhibitor

induced diabetes mellitus treated with insulin and metformin:

Evolution of diabetes management in the era of immunotherapy. Case

Rep Oncol Med. 2019:87813472019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Capitao R, Bello C, Fonseca R and Saraiva

C: New onset diabetes after nivolumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep.

2018:20172209992018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chae YK, Chiec L, Mohindra N, Gentzler R,

Patel J and Giles F: A case of Pembrolizumab-induced type-1

diabetes mellitus and discussion of immune checkpoint

inhibitor-induced type 1 diabetes. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

66:25–32. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chaudry A, Chaudry M and Aslam J:

Pembrolizumab: An immunotherapeutic agent causing endocrinopathies.

Cureus. 12:e88362020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cunha C, Silva E, Vieira AC, Saraiva C and

Duarte S: New onset autoimmune diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism

secondary to pembrolizumab in a patient with metastatic lung

cancer. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2022:21–0123.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

de Filette JMK, Pen JJ, Decoster L,

Vissers T, Bravenboer B, Van der Auwera BJ, Gorus FK, Roep BO,

Aspeslagh S, Neyns B, et al: Immune checkpoint inhibitors and type

1 diabetes mellitus: A case report and systematic review. Eur J

Endocrinol. 181:363–374. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Delasos L, Bazewicz C, Sliwinska A, Lia NL

and Vredenburgh J: New onset diabetes with ketoacidosis following

nivolumab immunotherapy: A case report and review of literature. J

Oncol Pharm Pract. 27:716–721. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Edahiro R, Ishijima M, Kurebe H, Nishida

K, Uenami T, Kanazu M, Akazawa Y, Yano Y and Mori M: Continued

administration of pembrolizumab for adenocarcinoma of the lung

after the onset of fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus as an

Immune-related adverse effect: A case report. Thorac Cancer.

10:1276–1279. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Godwin JL, Jaggi S, Sirisena I, Sharda P,

Rao AD, Mehra R and Veloski C: Nivolumab-induced autoimmune

diabetes mellitus presenting as diabetic ketoacidosis in a patient

with metastatic lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 5:402017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hatakeyama Y, Ohnishi H, Suda K, Okamura

K, Shimada T and Yoshimura S: Nivolumab-induced Acute-onset type 1

diabetes mellitus as an immune-related adverse event: A case

report. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 25:2023–2026. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang X, Yang M, Wang L, Li L and Zhong X:

Sintilimab induced diabetic ketoacidosis in a patient with small

cell lung cancer: A case report and literature review. Medicine

(Baltimore). 100:e257952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ishi A, Tanaka I, Iwama S, Sakakibara T,

Mastui T, Kobayashi T, Hase T, Morise M, Sato M, Arima H and

Hashimoto N: Efficacies of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

blockade in non-small cell lung cancer patients with acquired

resistance to prior programmed cell death 1 inhibitor and

development of diabetic ketoacidosis caused by two different

etiologies: A retrospective case series. Endocr J. 68:613–620.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kedzior SK, Jacknin G, Hudler A, Mueller

SW and Kiser TH: A severe case of diabetic ketoacidosis and

New-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus associated with Anti-glutamic

acid decarboxylase antibodies following immunotherapy with

pembrolizumab. Am J Case Rep. 22:e9317022021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee S, Morgan A, Shah S and Ebeling PR:

Rapid-onset diabetic ketoacidosis secondary to nivolumab therapy.

Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2018:18–0021. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li L, Masood A, Bari S, Yavuz S and

Grosbach AB: Autoimmune diabetes and thyroiditis complicating

treatment with nivolumab. Case Rep Oncol. 10:230–234. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li W, Wang H, Chen B, Zhao S, Zhang X, Jia

K, Deng J, He Y and Zhou C: Anti PD-1 monoclonal antibody induced

autoimmune diabetes mellitus: A case report and brief review.

Transl Lung Cancer Res. 9:379–388. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lupi I, Brancatella A, Cosottini M, Viola

N, Lanzolla G, Sgrò D, Dalmazi GD, Latrofa F, Caturegli P and

Marcocci C: Clinical heterogeneity of hypophysitis secondary to

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: Insights from four cases. Endocrinol Diabetes

Metab Case Rep. 2019:19–0102. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nishioki T, Kato M, Kataoka S, Miura K,

Nagaoka T and Takahashi K: Atezolizumab-induced fulminant type 1

diabetes mellitus occurring four months after treatment cessation.

Respirol Case Rep. 8:e006852020. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Patel S, Chin V and Greenfield JR:

Durvalumab-induced diabetic ketoacidosis followed by

hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2019:19–0098.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Porntharukchareon T, Tontivuthikul B,

Sintawichai N and Srichomkwun P: Pembrolizumab- and

Ipilimumab-induced diabetic ketoacidosis and isolated

adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency: A case report. J Med Case

Rep. 14:1712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ren Y, Zhang L, Wang Y and Zhong D: Immune

checkpoint inhibitors related diabetes mellitus: A report of 2

cases and literature review. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 25:61–65.

2022.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Seo JH, Lim T, Ham A, Kim YA and Lee M:

New-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus as a delayed immune-related

event after discontinuation of nivolumab: A case report. Medicine

(Baltimore). 101:e304562022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sothornwit J, Phunmanee A and

Pongchaiyakul C: Atezolizumab-induced autoimmune diabetes in a

patient with metastatic lung cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

10:3522019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tzoulis P, Corbett RW, Ponnampalam S,

Baker E, Heaton D, Doulgeraki T and Stebbing J: Nivolumab-induced

fulminant diabetic ketoacidosis followed by thyroiditis. Endocrinol

Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2018:18–0111. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yang J, Wang Y and Tong XM:

Sintilimab-induced autoimmune diabetes: A case report and review of

the literature. World J Clin Cases. 10:1263–1277. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

García-Cortés M, Lucena MI, Pachkoria K,

Borraz Y, Hidalgo R and Andrade RJ: Evaluation of naranjo adverse

drug reactions probability scale in causality assessment of

drug-induced liver injury. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 27:780–789.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente

D, Murakami S, Hui R, Yokoi T, Chiappori A, Lee KH, de Wit M, et

al: Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III Non-Small-Cell

lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 377:1919–1929. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chang LS, Barroso-Sousa R, Tolaney SM,

Hodi FS, Kaiser UB and Min L: Endocrine toxicity of cancer

immunotherapy targeting immune checkpoints. Endocr Rev. 40:17–65.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gardner G and Fraker CA: Natural killer

cells as key mediators in type i diabetes immunopathology. Front

Immunol. 12:7229792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kani ER, Karaviti E, Karaviti D, Gerontiti

E, Paschou IA, Saltiki K, Stefanaki K, Psaltopoulou T and Paschou

SA: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of immune checkpoint

Inhibitor-induced diabetes mellitus. Endocrine. 87:875–890. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen J, Hou X, Yang Y, Wang C, Zhou J,

Miao J, Gong F, Ge F and Chen W: Immune checkpoint

inhibitors-induced diabetes mellitus (review). Endocrine.

86:451–458. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Cho YK and Jung CH: Immune-Checkpoint

Inhibitors-Induced Type 1 diabetes mellitus: From its molecular

mechanisms to clinical practice. Diabetes Metab J. 47:757–766.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Perdigoto AL, Deng S, Du KC, Kuchroo M,

Burkhardt DB, Tong A, Israel G, Robert ME, Weisberg SP,

Kirkiles-Smith N, et al: Immune cells and their inflammatory

mediators modify β cells and cause checkpoint Inhibitor-induced

diabetes. JCI Insight. 7:e1563302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yoneda S, Imagawa A, Hosokawa Y, Baden MY,

Kimura T, Uno S, Fukui K, Goto K, Uemura M, Eguchi H, et al:

T-Lymphocyte infiltration to islets in the pancreas of a patient

who developed type 1 diabetes after administration of immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Diabetes Care. 42:e116–e118. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wu L, Tsang VHM, Sasson SC, Menzies AM,

Carlino MS, Brown DA, Clifton-Bligh R and Gunton JE: Unravelling

checkpoint inhibitor associated autoimmune diabetes: From bench to

bedside. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12:7641382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kamitani F, Nishioka Y, Koizumi M,

Nakajima H, Kurematsu Y, Okada S, Kubo S, Myojin T, Noda T, Imamura

T and Takahashi Y: Immune checkpoint Inhibitor-related type 1

diabetes incidence, risk, and survival association. J Diabetes

Investig. 16:334–342. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kyriacou A, Melson E, Chen W and

Kempegowda P: Is immune checkpoint Inhibitor-associated diabetes

the same as fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus? Clin Med (Lond).

20:417–423. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang AL, Wang F, Chang LS, McDonnell ME

and Min L: Coexistence of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced

autoimmune diabetes and pancreatitis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12:6205222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liao D, Liu C, Chen S, Liu F, Li W,

Shangguan D and Shi Y: Recent advances in immune checkpoint

Inhibitor-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus. Int Immunopharmacol.

122:1104142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Usui Y, Udagawa H, Matsumoto S, Imai K,

Ohashi K, Ishibashi M, Kirita K, Umemura S, Yoh K, Niho S, et al:

Association of serum Anti-GAD antibody and HLA haplotypes with type

1 diabetes mellitus triggered by nivolumab in patients with

Non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 12:e41–e43. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Pardini VC, Mourao DM, Nascimento PD,

Vívolo MA, Ferreira SR and Pardini H: Frequency of islet cell

autoantibodies (IA-2 and GAD) in young Brazilian type 1 diabetes

patients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 32:1195–1198. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wei HH, Lai YC, Lin G, Lin CW, Chang YC,

Chang JW, Liou MJ and Chen IW: Distinct changes to pancreatic

volume rather than pancreatic autoantibody positivity: Insights

into immune checkpoint inhibitors induced diabetes mellitus.

Diabetol Metab Syndr. 16:262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|