Introduction

According to recent data from GLOBOCAN, colorectal

cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer (after lung cancer and

female breast cancer) and the second leading cause of

cancer-related death (after lung cancer). Furthermore, there were

1,926,118 newly diagnosed CRC cases and 903,859 CRC-related deaths

in 2022 worldwide (1). Moreover,

owing to the greater proportion of older individuals and changes in

lifestyle, the incidence of CRC continues to rise (2). Screening and early diagnosis are

highly challenging, and improvements could help reduce the

morbidity and mortality associated with CRC (3,4). Owing

to the large population and limited health care resources in China,

colonoscopy is only used as a screening method for high-risk

individuals (5–7). In three studies utilizing patient

questionnaires, age, family history of cancer, history of smoking,

diabetes and frequency of intake of certain foods (such as

vegetables, fried food, pickled food and white meat) were noted as

being associated with the development of CRC (8–10).

Laxatives are widely used to treat constipation and

can be abused in eating disorders (particularly bulimia nervosa and

binge-eating disorder), and include stimulant agents, saline and

osmotic products (11). However, it

has been reported that the prevalence of laxative abuse ranges from

10 to 60% (12), which might lead

to disorders of electrolytes and acid-base; these disorders involve

the renal and cardiovascular systems and can become

life-threatening (13,14). Therefore, more precautions are

required to prevent the harm caused by laxative use.

Some laxatives including phenolphthalein laxatives

and magnesium laxatives have been reported to significantly

increase the incidence of CRC (15–17).

However, macrogol and fiber laxatives have been reported to have

the opposite effects (18,19). Moreover, other studies have

demonstrated that laxative use is not associated with CRC (20–26).

Therefore, there is still controversy regarding the influence of

laxative use on the incidence of CRC.

Materials and methods

Reporting guidelines

The present study was based on prior established

studies (15–26). The findings were reported following

the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses statement (27).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies and patients were

as follows: i) Patients who had completed any questionnaire

including self-reported laxative use; ii) at least one type of

laxative was reported; and iii) the incidence of CRC was reported.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) The type of study was

case reports, reviews, meta-analysis, letters to the editor,

comments or conference abstracts/proceedings (due to typically

limited peer review and incomplete datasets); ii) only had

pediatric populations; and iii) data were insufficient including

missing core variables, incomplete metrics or non-extractable

data.

Search strategy and study

selection

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to

identify relevant studies, which included terms such as ‘laxative’

and ‘CRC’. For laxative, the additional search terms were

‘cathartics’ OR ‘laxative’. For CRC, the additional search terms

were ‘colorectal cancer’ OR ‘colon cancer’ OR ‘rectal cancer’ OR

‘colorectal neoplasm’ OR ‘colon neoplasm’ OR ‘rectal neoplasm’ OR

‘colorectal tumor’ OR ‘colon tumor’ OR ‘rectal tumor’. The search

scope was limited to the title, abstract or key words, and only

studies published in English were included. The search strategy was

implemented by two independent authors across three databases

including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Embase (https://www.embase.com/) and the Cochrane Central

Register of Controlled Trials (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central). After

removing duplicated studies, the titles and abstracts were screened

to identify potentially relevant studies. Then, full texts were

reviewed to determine eligible studies based on the inclusion and

exclusion criteria. Additionally, the reference lists of included

studies were examined to identify additional relevant articles. In

cases of disagreement between the two authors, a group discussion

with a third individual was consulted to reach a consensus.

Data collection

Data extraction was performed independently by two

authors at the same time. The study characteristic data extracted

were as follows: The first author, publication year, country where

the study was conducted, study period, sample size, study type,

laxative subtype, and conclusion. Patients who used laxatives were

categorized into the laxative use group, and those who had no

history of laxative use were categorized into the non-laxative use

group. The incidence of CRC in each group was recorded. To ensure

accuracy and completeness, the extracted data were cross-checked by

both authors, and any discrepancies were resolved through

discussion.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed

using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) score (28). Then, two independent authors

assigned ratings based on the following criteria: 9 points

indicated high quality, 7–8 points indicated median quality and

<7 points indicated low quality. Any discrepancies in scoring

were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third

individual.

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)

were calculated to compare the incidence of CRC between the

laxative use and the non-laxative use groups. Heterogeneity was

assessed using the I2 statistic and the χ2

test (29,30). According to the Cochrane handbook,

an I2<30% was considered non-important, an

I2 range of 30–60% was considered moderate and an

I2>60% was considered substantial (30). The random-effect model was applied

as the default model, and P<0.05 indicated a statistically

significant difference. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel

plot. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata V18.0

(StataCorp LP).

Results

Study selection

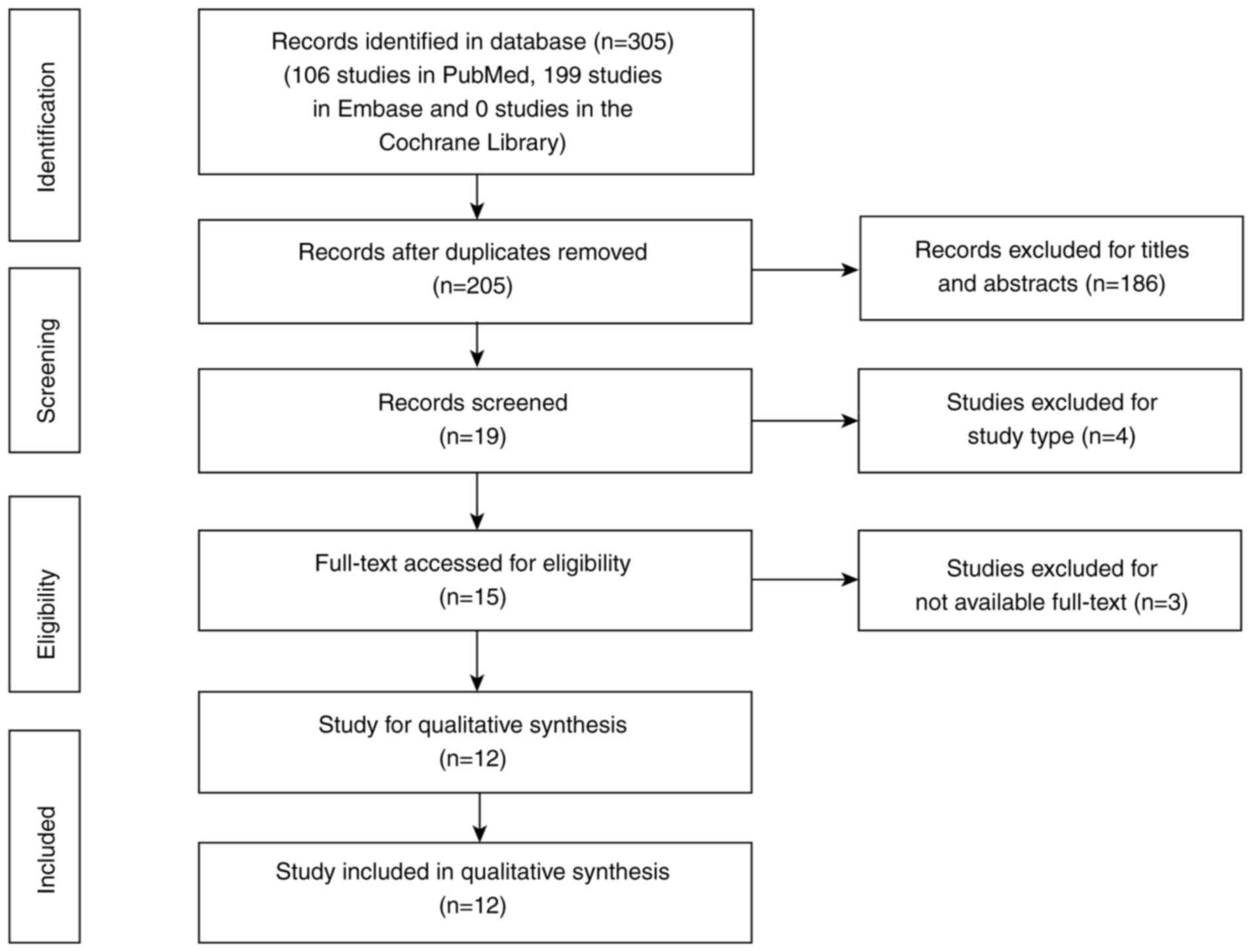

Following the initial search, 305 studies were

identified (106 studies in PubMed, 199 studies in Embase and 0

studies in the Cochrane Library). After removing duplicates, 205

studies remained. Screening of the titles and abstracts identified

19 studies with potentially relevant content. Finally, 12

observational studies with sufficient data were included in the

pooled analysis after full-text review (Fig. 1). Additionally, the reference lists

of these studies were screened, but no further eligible studies

were identified.

Baseline characteristics

The 12 included studies were published between 1988

and 2019, spanning a period of 30 years. These studies were

conducted in seven countries, with 5 studies originating from the

United States. Among the included studies, 7 were case-control

studies and the remaining 5 were cohort studies. The primary

laxative types investigated included anthraquinone, fiber,

phenolphthalein and magnesium laxatives. Detailed information on

the laxative types and the conclusions of each study are shown in

Table I.

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the

included studies. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the

included studies.

| First author/s,

year | Country | Study date | No. of

patients | Study type | Laxative type | Conclusion | NOS | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kune et al,

1988 | Australia | 1980-1981 | 1,442 | Case-control | NR | Laxative use was

unlikely to be an etiological factor in the development of

CRC. | 8 | (20) |

| Jacobs and White,

1998 | United States | 1985-1989 | 838 | Case-control | Phenolphthalein,

fiber, magnesium and other commercial laxatives | All types of

commercial laxatives, except for fiber laxatives, seemed to be

associated with increased risk of CRC. | 7 | (15) |

| Dukas et al,

2000 | United States | 1984-1996 | 84,577 | Cohort | Softeners, bulk

agents and suppositories | The findings did

not support an association between laxative use and the risk of

CRC. | 7 | (21) |

| Nusko et al,

2000 | Germany | 1993-1996 | 554 | Case-control | Anthranoid

laxative | Anthranoid laxative

use was not associated with any significant risk of developing

colorectal adenoma or carcinoma. | 7 | (22) |

| Nascimbeni et

al, 2002 | Italy | 1997-1999 | 192 | Case-control |

Anthranoid-containing laxatives were

defined as herbal drugs containing senna, cascara, frangula, aloe

and rheum, or as laxative drugs containing danthrone and purified

sennosides. | The findings did

not support the hypothesis of a cause-effect relationship of CRC

with laxative use. | 6 | (23) |

| Roberts et

al, 2003 | United States | 1996-2000 | 1,691 | Case-control | Phenolphthalein,

fiber, magnesium, other commercial and non-commercial or unknown

laxatives. | There was no

association between laxative use and colon cancer. | 7 | (24) |

| Watanabe et

al, 2004 | Japan | 1990-1997 | 41,670 | Cohort | NR | Laxative use

increased the risk of colon cancer. | 9 | (16) |

| Park et al,

2009 | United Kingdom | 1993-1997 | 889 | Cohort | NR | Laxative use was

not associated with CRC risk. | 8 | (25) |

| Charlton et

al, 2013 | United Kingdom | 2000-2009 | 33,138 | Case-control | All stimulant,

osmotic and. bulk laxatives, fecal softeners and bowel cleansing

preparations | A reduced CRC risk

associated with macrogol use was observed after accounting for the

lead time for CRC. | 7 | (18) |

| Zhang et al,

2013 | United States | 1982-2010 | 88,173 | Cohort | Softeners, bulking

agents and suppositories. | Laxative use seemed

to not be associated with CRC risk. | 9 | (26) |

| Citronberg et

al, 2014 | New Zealand | 2000-2010 | 144,455 | Cohort | Fiber-based

(Metamucil, Citrucel, FiberCon or Fiberall) and non-fiber (Ex-lax,

Correctol or milk of magnesia) laxatives | The risk of CRC

increased with non-fiber laxative use and decreased with fiber

laxative use. | 9 | (19) |

| Citronberg et

al, 2018 | United States | 1997-2008 | 17,694 | Case-control | Fiber (Metamucil,

Citrucel, Fibercon, Serutan and psyllium) and non-fiber (Ex-Lax,

Correctol, Dulcolax, Senokot, Colace, castor oil, cod liver oil,

mineral oil, milk of magnesia, lactulose and Epsom salts)

laxatives. | Individuals who

reported using non-fiber-based laxatives regularly were at a

significantly increased risk for CRC compared with those who

reported no laxative use. No statistically significant associations

were observed between fiber-based laxative use and CRC. | 9 | (17) |

History of laxative use and the risk

of CRC

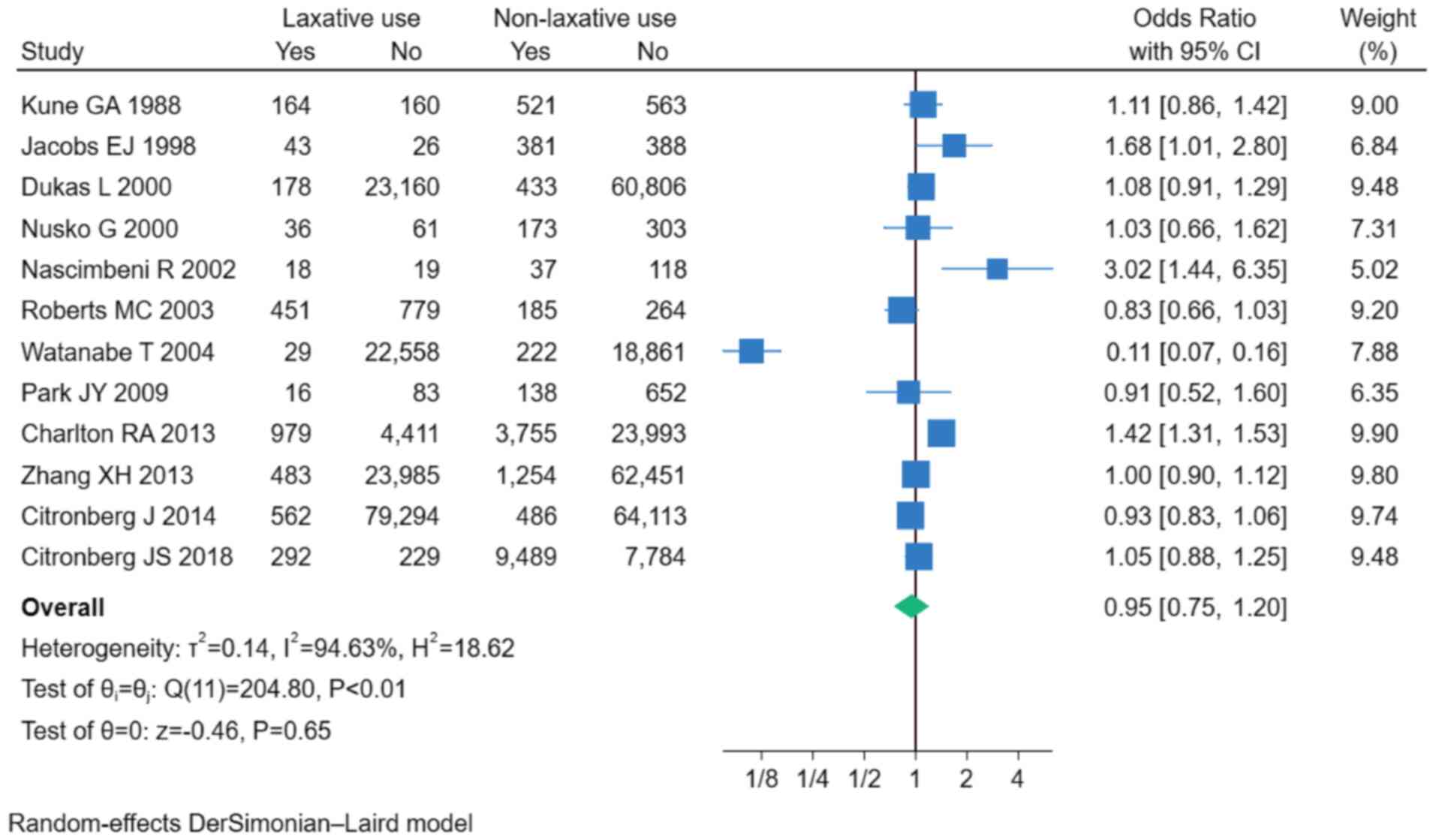

The results from the 12 included studies indicated

that a history of laxative use was not significantly associated

with the incidence of CRC (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.75–1.20; P=0.65;

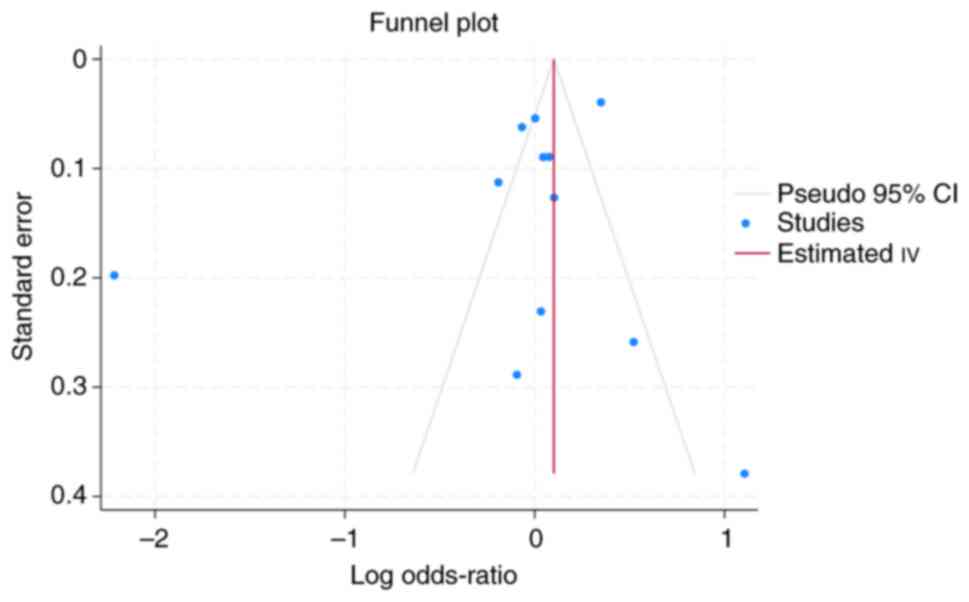

I2=94.63%; Fig. 2) To

assess potential publication bias, a funnel plot was generated

(Fig. 3). Visual inspection of the

funnel plot revealed asymmetry, suggesting the possibility of

publication bias.

History of different laxative type use

and the risk of CRC

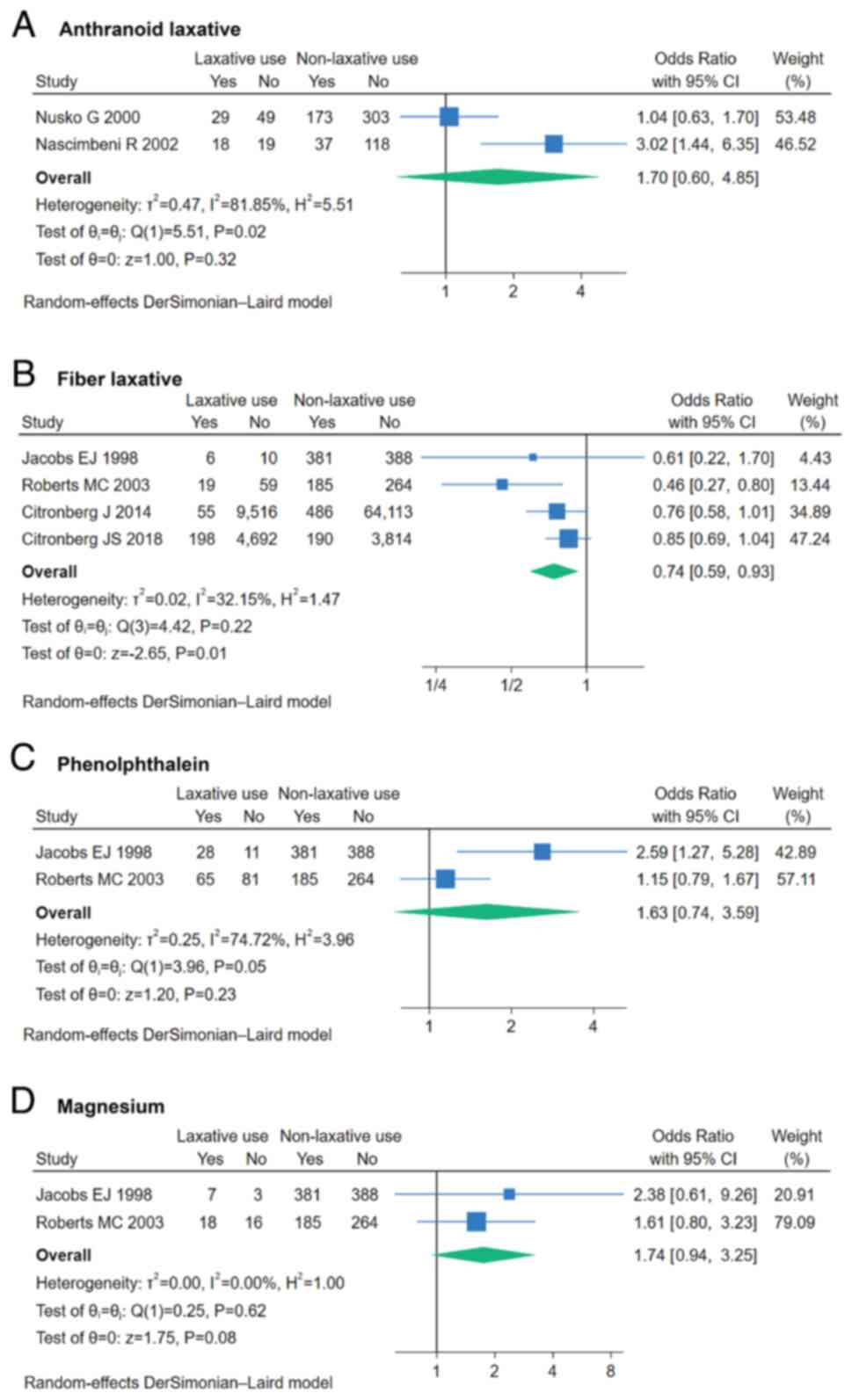

In total, 4 studies reported data on fiber

laxatives. Pooled analysis revealed that fiber laxative use was

associated with a reduced risk of CRC (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.59–0.93;

P=0.01; I2=32.15%; Fig.

4B). Additionally, 3 other types of laxatives were each

reported in 2 studies. However, anthranoid, phenolphthalein and

magnesium laxatives showed no significant association with CRC risk

(Fig. 4A, C and D).

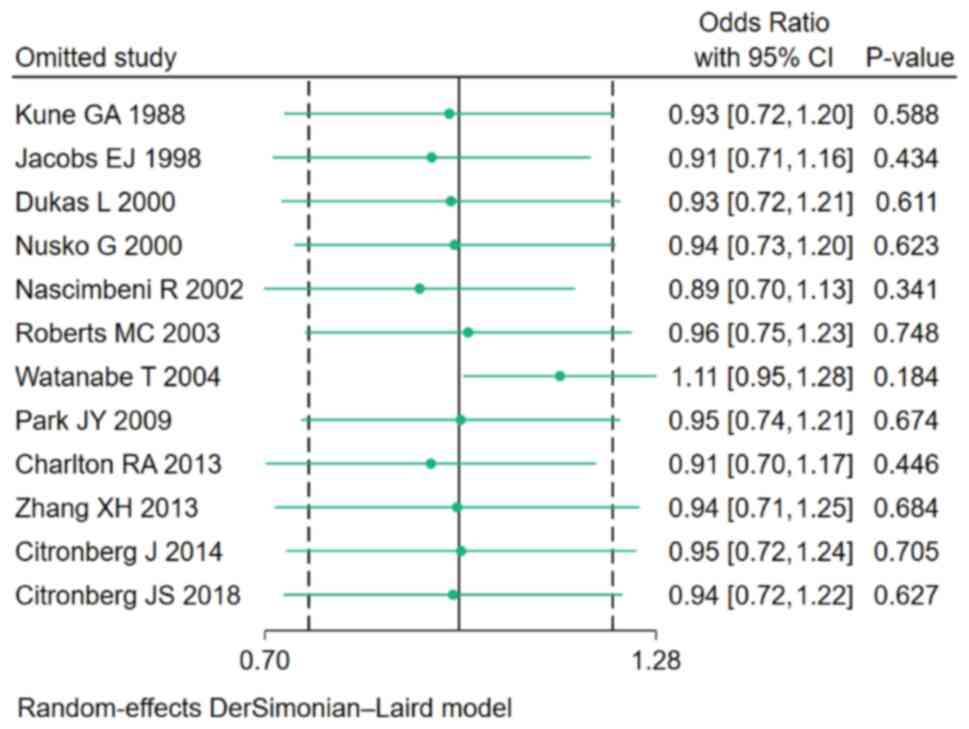

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the study findings, a

sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially excluding each

study and re-running the pooled analysis. The results remained

consistent across all iterations, indicating that the findings were

not significantly altered by any single study (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In the present study, 12 eligible observational

studies involving 415,313 patients were identified for analysis.

After pooling the data, no association between laxative use and the

risk of CRC was found. Subgroup analyses of different laxative

types revealed that the fiber laxative group had fewer patients

with CRC than the non-fiber laxative group. Other types of

laxatives, including anthranoid, phenolphthalein and magnesium

laxatives, had no identified effect on the incidence of CRC.

To diagnose patients with CRC earlier, both

CRC-related symptoms and strong risk factors for CRC should be

considered. Staging at detection dramatically impacts survival

outcomes, with 5-year survival rates of 91% for localized disease

(Stage I) versus merely 14% for metastatic cases (Stage IV)

(31). Then, late diagnosis

increases surgical morbidity risks and permanent ostomy rates,

severely compromising quality of life (32). In addition to commonly examined

characteristics, including age, family history of cancer, history

of smoking, diabetes and the frequency of food intake (8–10),

drug use, including macrolide and lincosamide use, has also been

reported to be a risk factor for CRC (33). Drugs might change the gut microbiota

composition and destroy immune responses, which could lead to

chronic inflammation and tumor progression (34–36).

Additionally, quinolones (a type of antibiotic) can damage DNA,

which increases the risk of cancer (37).

Laxatives are also widely used and might influence

CRC. Certain studies have reported that non-fiber laxatives are

associated with an increased risk of CRC (15,17,19). A

previous study examining 41,670 cases demonstrated that laxative

use increased the risk of colon cancer (16). Conversely, other studies revealed

that the risk of CRC decreased with fiber laxative use (15,19),

and Charlton et al (18)

reported that macrogol reduces the risk of CRC. Additionally, other

studies did not find an overall association between laxative use

and CRC (20–26), and a previous systematic review and

meta-analysis indicated that there was no association between

anthraquinone laxative use and the development of CRC (38). Therefore, there is notable

controversy regarding whether laxatives have harmful effects,

protective effects or no effect on the incidence of CRC.

Long-term medication or drug abuse might damage the

intestinal environment. Some biological evidence has shown that

ecological imbalance, especially in some bacterial strains, might

promote cancer by altering cell growth, differentiation and

apoptosis (39,40). Some non-fiber laxatives including

anthranoid laxatives and phenolphthalein were found to have

mutagenic and genotoxic effects, which might be the mechanisms

underlying the development of CRC risk (19,41,42).

The potential mechanism underlying the protective effect of fiber

laxatives might be that high dietary fiber intake could dilute

carcinogens and bind carcinogenic bile acids. Additionally, fiber

helps produce short-chain fatty acids, which can normalize cell

proliferation and differentiation as well as promote

anticarcinogenic action (43–45).

However, the association between laxative use and CRC risk is

complex, and the present study, as a synthesis of observational

data, could not clarify the mechanisms underlying various laxative

types.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study

represented the largest and most comprehensive pooled analysis to

date on the association between laxative use and CRC risk. The

findings of the present study resolved existing controversies, that

have notable implications for clinical practice and may pave the

way for future investigations into the mechanisms underlying

laxative effects on CRC risk. However, the present study has

several limitations. First, the results might have a bias

accounting for the frequency of laxative intake. However, there

were not enough data for a dose-response meta-analysis. Second, 3

of the 12 included studies only analyzed colon cancer cases,

although both colon cancer and rectal cancer originate from

epithelial cells (46), which may

have led to the high heterogeneity of the studies. Third, some of

the included studies were old, which might limit the universality

of the study findings. Fourth, while funnel plot asymmetry

suggested potential publication bias, statistical confirmation was

limited by the small number of included studies (n=7). This pattern

may reflect the selective reporting of positive outcomes.

Therefore, additional long-term randomized controlled trials that

investigate the relationship between the dosage of laxatives

administered and the incidence of CRC are needed to determine the

potential mechanisms and effects of different types of

laxatives.

In conclusion, the standardized use of laxatives for

treatment is safe. Moreover, fiber laxatives may decrease the risk

of CRC. However, more studies are needed to determine whether

laxative abuse increases the risk of CRC.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to Dr Tianwu Chen

(Department of Radiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of

Chongqing Medical University) for his expert arbitration in

resolving methodological disagreements during data extraction and

eligibility assessment.

Funding

Funding: Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Author's contributions

LXR conceived the study. LXR and ZXM designed the

search strategy, performed the literature search and data

extraction and assessed the risk of bias. LXR and ZXM confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. ZXM performed the data analysis

and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LXR and ZXM revised

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Edwards BK, Ward E and Kohler BA: Annual

report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring

colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors,

screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer.

116:544–573. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI

and Blasi PR: Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence

Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task

Force. JAMA. 325:1978–1998. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Knudsen AB, Rutter CM, Peterse EFP, Lietz

AP, Seguin CL, Meester RGS, Perdue LA, Lin JS, Siegel RL,

Doria-Rose VP, et al: Colorectal cancer screening: An updated

modeling study for the US preventive services task force. JAMA.

325:1998–2011. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen H, Li N, Ren J, Feng X, Lyu Z, Wei L,

Li X, Guo L, Zheng Z, Zou S, et al: Participation and yield of a

population-based colorectal cancer screening programme in China.

Gut. 68:1450–1457. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cao M, Li H, Sun D, He S, Yu Y, Li J, Chen

H, Shi J, Ren J, Li N and Chen W: Cancer screening in China: The

current status, challenges, and suggestions. Cancer Lett.

506:120–127. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen H, Lu B and Dai M: Colorectal cancer

screening in China: Status, challenges, and prospects-China, 2022.

China CDC Wkly. 4:322–328. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cai QC, Yu ED, Xiao Y, Bai WY, Chen X, He

LP, Yang YX, Zhou PH, Jiang XL, Xu HM, et al: Derivation and

validation of a prediction rule for estimating advanced colorectal

neoplasm risk in average-risk Chinese. Am J Epidemiol. 175:584–593.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wong MC, Lam TY, Tsoi KK, Hirai HW, Chan

VC, Ching JY, Chan FK and Sung JJ: A validated tool to predict

colorectal neoplasia and inform screening choice for asymptomatic

subjects. Gut. 63:1130–1136. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sung JJY, Wong MCS, Lam TYT, Tsoi KKF,

Chan VCW, Cheung W and Ching JYL: A modified colorectal screening

score for prediction of advanced neoplasia: A prospective study of

5744 subjects. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 33:187–194. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Streatfeild J, Hickson J, Austin SB,

Hutcheson R, Kandel JS, Lampert JG, Myers EM, Richmond TK,

Samnaliev M, Velasquez K, et al: Social and economic cost of eating

disorders in the United States: Evidence to inform policy action.

Int J Eat Disord. 54:851–868. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Roerig JL, Steffen KJ, Mitchell JE and

Zunker C: Laxative abuse: Epidemiology, diagnosis and management.

Drugs. 70:1487–1503. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Linardon J: Rates of abstinence following

psychological or behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder:

Meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 51:785–797. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hazzard VM, Simone M, Austin SB, Larson N

and Neumark-Sztainer D: Diet pill and laxative use for weight

control predicts first-time receipt of an eating disorder diagnosis

within the next 5 years among female adolescents and young adults.

Int J Eat Disord. 54:1289–1294. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jacobs EJ and White E: Constipation,

laxative use, and colon cancer among middle-aged adults.

Epidemiology. 9:385–3891. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Watanabe T, Nakaya N, Kurashima K,

Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y and Tsuji I: Constipation, laxative use and

risk of colorectal cancer: The Miyagi Cohort Study. Eur J Cancer.

40:2109–2115. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Citronberg JS, Hardikar S, Phipps A,

Figueiredo JC and Newcomb P: Laxative type in relation to

colorectal cancer risk. Ann Epidemiol. 28:739–741. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Charlton RA, Snowball JM, Bloomfield K and

de Vries CS: Colorectal cancer risk reduction following macrogol

exposure: A cohort and nested case control study in the UK. PLoS

One. 8:e832032013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Citronberg J, Kantor ED, Potter JD and

White E: A prospective study of the effect of bowel movement

frequency, constipation, and laxative use on colorectal cancer

risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 109:1640–1649. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kune GA, Kune S, Field B and Watson LF:

The role of chronic constipation, diarrhea, and laxative use in the

etiology of large-bowel cancer. Data from the Melbourne Colorectal

Cancer Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 31:507–512. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Dukas L, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS,

Rosner B and Giovannucci EL: Prospective study of bowel movement,

laxative use, and risk of colorectal cancer among women. Am J

Epidemiol. 151:958–964. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nusko G, Schneider B, Schneider I,

Wittekind C and Hahn EG: Anthranoid laxative use is not a risk

factor for colorectal neoplasia: Results of a prospective case

control study. Gut. 46:651–655. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nascimbeni R, Donato F, Ghirardi M,

Mariani P, Villanacci V and Salerni B: Constipation, anthranoid

laxatives, melanosis coli, and colon cancer: A risk assessment

using aberrant crypt foci. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.

11:753–757. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Roberts MC, Millikan RC, Galanko JA,

Martin C and Sandler RS: Constipation, laxative use, and colon

cancer in a North Carolina population. Am J Gastroenterol.

98:857–864. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Park JY, Mitrou PN, Luben R, Khaw KT and

Bingham SA: Is bowel habit linked to colorectal cancer?-Results

from the EPIC-Norfolk study. Eur J Cancer. 45:139–145. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang X, Wu K, Cho E, Ma J, Chan AT, Gao

X, Willett WC, Fuchs CS and Giovannucci EL: Prospective cohort

studies of bowel movement frequency and laxative use and colorectal

cancer incidence in US women and men. Cancer Causes Control.

24:1015–1024. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J and Altman

DG; PRISMA Group, : Preferred reporting items for systematic

reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med.

6:e10000972009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Stang A: Critical evaluation of the

Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of

nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol.

25:603–605. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ioannidis JP: Interpretation of tests of

heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract.

14:951–957. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ and

Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ.

327:557–560. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Brenner H, Bouvier AM, Foschi R, Hackl M,

Larsen IK, Lemmens V, Mangone L and Francisci S; EUROCARE Working

Group, : Progress in colorectal cancer survival in Europe from the

late 1980s to the early 21st century: the EUROCARE study. Int J

Cancer. 131:1649–1658. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Simin J, Fornes R and Liu Q: Antibiotic

use and risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and

dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 123:1825–1832. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sobhani I, Tap J, Roudot-Thoraval F,

Roperch JP, Letulle S, Langella P, Corthier G, Tran Van Nhieu J and

Furet JP: Microbial dysbiosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients.

PLoS One. 6:e163932011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wong SH and Yu J: Gut microbiota in

colorectal cancer: Mechanisms of action and clinical applications.

Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:690–704. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Francescone R, Hou V and Grivennikov SI:

Microbiome, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer J. 20:181–189. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bush NG, Diez-Santos I, Abbott LR and

Maxwell A: Quinolones: Mechanism, lethality and their contributions

to antibiotic resistance. Molecules. 25:56620202

|

|

38

|

Lombardi N, Crescioli G, Maggini V,

Bellezza R, Landi I, Bettiol A, Menniti-Ippolito F, Ippoliti I,

Mazzanti G, Vitalone A, et al: Anthraquinone laxatives use and

colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

observational studies. Phytother Res. 36:1093–1102. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hibberd AA, Lyra A, Ouwehand AC, Rolny P,

Lindegren H, Cedgård L and Wettergren Y: Intestinal microbiota is

altered in patients with colon cancer and modified by probiotic

intervention. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 4:e0001452017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gagnière J, Raisch J, Veziant J, Barnich

N, Bonnet R, Buc E, Bringer MA, Pezet D and Bonnet M: Gut

microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

22:501–518. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

van Gorkom BA, de Vries EG, Karrenbeld A

and Kleibeuker JH: Review article: Anthranoid laxatives and their

potential carcinogenic effects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 13:443–452.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Dunnick JK and Hailey JR: Phenolphthalein

exposure causes multiple carcinogenic effects in experimental model

systems. Cancer Res. 56:4922–4926. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Park Y, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Bergkvist

L, Berrino F, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Colditz GA, Freudenheim

JL, Fuchs CS, et al: Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal

cancer: A pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. JAMA.

294:2849–2857. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Alabaster O, Tang Z and Shivapurkar N:

Dietary fiber and the chemopreventive modelation of colon

carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 350:185–197. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lipkin M, Reddy B, Newmark H and Lamprecht

SA: Dietary factors in human colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Nutr.

19:545–586. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de

Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR,

Sansom OJ and Clevers H: Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of

intestinal cancer. Nature. 457:608–611. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|