Introduction

Gynecological malignancies, encompassing numerous

types of cancer of the female reproductive system, represent a

notable global health burden. Among these malignancies, ovarian,

endometrial and cervical cancer are the most prevalent. According

to GLOBOCAN 2020 statistics, ovarian, endometrial and cervical

cancer accounted for 313,959, 417,367 and 604,127 new global cases,

respectively, and ranked 19, 17 and 9th, in terms of global cancer

incidence. In addition, regarding the mortality rates, ovarian

cancer, endometrial cancer and cervical cancer were responsible for

207,252, 97,370 and 341,831 deaths respectively, collectively

representing 6.5% of all female cancer-related deaths (1).

Despite advances in medical science, the diagnosis

and treatment of gynecological malignancies continue to pose

notable challenges. Early detection methods remain elusive for a

number of patients, and the current therapeutic approaches often

fall short in managing advanced or recurrent disease. However,

recent research into circular RNAs (circRNAs) has emerged as a

promising option for both diagnostic and therapeutic innovations in

gynecological oncology (2,3). circRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs

characterized by their covalently closed loop structure, which have

gained considerable attention in cancer research due to their

stability, tissue-specific expression and diverse regulatory

functions (4). In the context of

gynecological malignancies, circRNAs have been implicated in

various aspects of tumor biology, including cell proliferation,

metastasis and drug resistance (5).

For example, in ovarian cancer, circWHSC1 has been shown to promote

tumor progression by sponging microRNA (miRNA/miR)-145 and

miR-1182, ultimately upregulating mucin-1 (MUC1) and human

telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) (6). In endometrial cancer, homo

sapiens (hsa)_circRNA_079422 has been found to enhance tumor

growth and metastasis by modulating the miR-136-5p/high-mobility

group AT-hook 2 axis (7).

Similarly, in cervical cancer, circRNAs serve a key regulatory role

in cervical cancer progression, showing potential as therapeutic

agents and novel biomarkers; however, further clinical research is

needed to fully understand their therapeutic benefits (8). The unique properties of circRNAs,

including their abundance, stability in bodily fluids and

tissue-specific expression patterns, make them promising candidates

for biomarker development in gynecological cancer (9). Moreover, the diverse regulatory

functions of circRNAs offer potential targets for novel therapeutic

interventions (10).

The present review aimed to provide a comprehensive

overview of recent advances in circRNA research within the context

of gynecological malignancies. The biogenesis and functions of

circRNAs, their roles in the pathogenesis of ovarian, endometrial

and cervical cancer were explored, and as well as potential

applications in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. By summarizing

current knowledge and identifying future research directions, the

present review highlighted the potential of circRNAs as a novel

avenue for improving the management of gynecological malignancies

(Table I).

| Table I.Key circRNAs and their functions in

ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer. |

Table I.

Key circRNAs and their functions in

ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer.

| Type of cancer | circRNA | Function | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ovarian | circMUC16 | Promotes

proliferation and invasion by sponging miR-199a-5p to regulate

beclin-1 and RUNX1 expression | (74) |

| Ovarian | circCSPP1 | Promotes cancer

progression by counteracting the tumor-suppressive effects of

miR-1236-3p on ZEB1 | (75) |

| Ovarian | circFBXW7 | Encodes FBXW7-185aa

protein, which acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cancer cell

proliferation and migration | (61) |

| Ovarian | circRNA-encoded

peptide SHPRH-146aa | Inhibits tumor

growth by protecting full-length SHPRH from degradation | (63) |

| Endometrial | circTNFRSF21 | Serves a crucial

role in cancer cell growth and cell cycle progression by

competitively binding with miR-1227, activating the MAPK13/ATF2

signaling pathway | (104) |

| Endometrial | circWHSC1 | Promotes cell

proliferation, migration and invasion while inhibiting

apoptosis | (91) |

| Endometrial |

hsa_circ_0061140 | Promotes

progression and migration through a regulatory axis involving

miR-149-5p and STAT3 | (107) |

| Cervical | circE7 | Encodes E7

oncoprotein, contributing to transforming properties of HPV | (62) |

| Cervical |

hsa_circ_0023404 | Promotes cancer

development by sponging miR-136, leading to increased expression of

TFCP2 and subsequent activation of the YAP pathway | (126) |

| Cervical | circ_0005576 | Promotes cell

proliferation and metastasis by sponging miR-153-3p and promoting

kinesin family member 20A expression | (128) |

Introduction to circRNA

circRNAs represent a unique class of non-coding RNA

molecules characterized by their covalently closed loop structure,

which distinguishes them from linear RNAs by the absence of 5′-3′

polarity and polyadenylated tails (11). This distinctive structure, first

identified in viruses by Sanger et al (12) in 1976, confers properties of

enhanced stability, cooperativity and self-complementarity. The

presence of circRNAs in eukaryotic cells was subsequently

demonstrated by Hsu and Coca-Prados in 1979 (13), marking the beginning of a new era in

RNA biology.

Initially, the importance of circRNAs was

underappreciated due to limitations in RNA sequencing technologies

and bioinformatics tools. For a number of years, these molecules

were dismissed as non-functional by-products of aberrant splicing

events (14); however, advances in

high-throughput sequencing and computational analysis have led to a

paradigm shift in the understanding of circRNAs and their potential

roles in cellular processes (15).

A key breakthrough in circRNA research came with the discovery that

these molecules often harbor numerous miRNA binding sites, enabling

them to function as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or ‘miRNA

sponges’ (16). This mechanism

allows circRNAs to regulate gene expression by modulating the

availability of miRNAs, thereby influencing various cellular

processes and pathways (17). In

the context of gynecological malignancies, this regulatory function

has been implicated in key aspects of tumor biology, including cell

proliferation, metastasis and drug resistance (3). Beyond their role as miRNA sponges,

circRNAs have been shown to interact with RNA-binding proteins

(RBPs), potentially modulating protein function and localization

(18). In addition, some circRNAs

have been reported to encode functional peptides, such as

circZNF609 (19) and circFBXW7

(20), adding another layer of

complexity to their regulatory potential. These diverse functions

underscore the importance of circRNAs in both physiological and

pathological processes, including the development and progression

of gynecological cancer. As research in this field continues to

evolve, circRNAs are emerging as promising biomarkers and potential

therapeutic targets in gynecological oncology (21). The unique properties of circRNAs,

including tissue-specific expression patterns and stability in

bodily fluids, make them attractive candidates for non-invasive

diagnostic and prognostic applications (22). Moreover, the ability to manipulate

circRNA expression levels or function offers novel options for

therapeutic interventions in gynecological malignancies (23).

Classification

The diversity of circRNAs is reflected in their

classification, which is primarily based on their genomic origin

and structure. Understanding these classifications is essential for

elucidating their roles in gynecological malignancies. circRNAs can

be categorized into three main subclasses based on their genomic

origin and structure. Exonic circRNA (EcircRNA) is the most

prevalent form, accounting for >80% of known circRNAs (24); these are generated through the

process of ‘backsplicing’, where a downstream 5′ splice site

(donor) is joined to an upstream 3′ splice site (acceptor).

Circular intronic RNA (ciRNA) is derived from intron lariats that

evade the typical linear splicing debranching step, retaining a

2′-5′ linkage at the branch point (25). Exon-intron circRNA (EIciRNA)

contains both exonic and intronic sequences and has been shown to

enhance the expression of their parent genes in cis,

suggesting a potential regulatory role (26). Other types of circRNAs include

antisense circRNAs, which are derived from antisense transcripts,

and intergenic circRNAs, which originate from intergenic regions or

other unannotated genomic sequences (27). As research progresses, and new

biotechnologies and bioinformatics strategies emerge, the

understanding of circRNA classification and function could continue

to evolve (28). Future studies may

identify additional subtypes or refine the current classification

system, providing deeper insights into the diverse roles of these

unique RNA molecules in cellular processes and disease

mechanisms.

The classification of circRNAs is not merely an

academic exercise but has significant implications for

understanding their functions in gynecological cancer. For example,

EcircRNAs often act as miRNA sponges, modulating gene expression

and influencing tumor progression (29). By contrast, ciRNAs and EIciRNAs tend

to regulate gene expression through interactions with the

transcriptional machinery (30).

The ongoing exploration of circRNA classification in gynecological

cancer promises to uncover novel biomarkers for early detection and

prognosis, as well as potential therapeutic targets. For example,

the tissue-specific expression patterns of certain circRNA classes

may be exploited in the development of targeted therapies or

diagnostic tools specific to ovarian, endometrial or cervical

cancer (3).

Formation mechanisms of circRNA

The biogenesis of circRNAs in gynecological

malignancies remains an area of active investigation, with several

proposed models offering insights into their formation (4,27,31). A

prominent hypothesis posits that during the splicing of mRNA

precursors, a process critical in gene expression regulation,

non-contiguous exons may be brought into proximity through partial

folding of the transcript. This spatial rearrangement can lead to

exon skipping, resulting in the formation of a lariat intermediate

structure encompassing both exonic and intronic sequences.

Subsequently, this lariat undergoes a reverse splicing event,

culminating in the generation of a stable circRNA molecule. This

mechanism may be particularly relevant in the context of

gynecological tumors, where aberrant splicing events are frequently

observed and could contribute to the dysregulation of circRNA

formation, potentially influencing tumor progression and treatment

response (32).

In the context of gynecological malignancies, an

alternative model of circRNA biogenesis has gained traction,

emphasizing the role of intronic sequences in facilitating

circularization. This mechanism, known as intron pair-driven

circularization, involves the interaction of specific complementary

sequences within flanking introns. These sequences, often found at

the termini of exons, engage in reverse complementary base pairing,

effectively bridging distant genomic regions. This intronic

‘kissing’ interaction brings downstream splice donor sites into

close proximity with upstream splice acceptor sites, thereby

promoting the circularization of the intervening exonic sequences.

In gynecological tumors, where genomic instability and chromosomal

rearrangements are common, this mechanism may be particularly

relevant, potentially contributing to the aberrant expression of

circRNAs observed in these malignancies. Understanding this process

could provide insights into tumor-specific circRNA profiles, and

their potential diagnostic or therapeutic implications in

gynecological oncology (33).

Another emerging model of circRNA formation

highlights the pivotal role of RBPs in the landscape of

gynecological malignancies. These versatile proteins exhibit a

marked capacity to influence circRNA biogenesis through specific

interactions with both exonic and intronic sequences. RBPs can

selectively bind to motifs located at the termini of exons and

introns, subsequently forming dimeric complexes. These RBP dimers

serve as molecular bridges, effectively reducing the spatial

distance between distal intronic regions. This RBP-mediated

proximity facilitates the circular connection of exons, promoting

circRNA formation. In the context of gynecological tumors, where

the aberrant expression and function of RBPs is frequently

observed, this mechanism may contribute to the dysregulation of

circRNA profiles. Understanding the interplay between RBPs and

circRNA biogenesis in these malignancies may indicate novel

diagnostic biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets, thereby

advancing the understanding of tumor biology and treatment

strategies in gynecological oncology (34).

Functions of circRNA

circRNAs have emerged as key regulators of gene

expression and are implicated in the pathogenesis of various human

diseases, including gynecological malignancies. These versatile

molecules exhibit multiple functional modalities that contribute to

cellular processes and disease progression. Current research has

elucidated several key functions of circRNAs: i) They can modulate

transcriptional activity; ii) act as ceRNAs by sequestering miRNAs;

iii) serve as scaffolds for protein complexes; and iv) possess

protein-coding potential under specific cellular conditions

(35). These diverse functions

highlight the significance of circRNAs in the complex landscape of

gynecological tumor biology and present potential avenues for

diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Transcriptional regulation by circRNA

The intricate interplay between circRNA biogenesis

and transcriptional regulation has emerged as a notable area of

interest in gynecological oncology (36,37).

This complex relationship indicates novel mechanisms of gene

expression modulation that may be key in the development and

progression of gynecological cancer. In a pioneering study,

Ashwal-Fluss et al (38)

reported a competitive relationship between circRNA splicing and

pre-mRNA processing. This competition was shown to occur at the 5′

and 3′ splice sites, suggesting that circRNA formation may serve as

a regulatory checkpoint in the gene expression cascade. In the

context of gynecological tumors, where aberrant gene expression is

a hallmark feature, this circRNA-mediated regulation of linear

transcript levels could represent a novel layer of transcriptional

control. Further elucidating this concept, research has

demonstrated that optimized circRNA expression systems can markedly

enhance backsplicing efficiency (39). This process effectively sequesters

exons into circular structures, consequently attenuating the

production of linear mRNA transcripts. For example, in ovarian

cancer, the formation of circ-mucin 16 (MUC16) has been shown to

reduce the expression of its linear counterpart, CA125, a

well-known biomarker for ovarian cancer (40). This finding highlights the potential

impact of circRNA biogenesis on the expression of clinically

relevant genes in gynecological malignancies. In endometrial cancer

the circRNA, circ-rho GTPase activating protein 12 (ARHGAP12), has

been shown to regulate the expression of its parental gene

ARHGAP12, a tumor suppressor, by competing for splicing machinery

(41). This regulatory mechanism

can influence cell proliferation and invasion, underscoring the

functional significance of circRNA-mediated transcriptional control

in gynecological cancer.

Moreover, some circRNAs have been shown to interact

directly with RNA polymerase II or other components of the

transcriptional machinery. For example, the ciRNA ci-ankyrin repeat

domain 52 has been reported to accumulate at its sites of

transcription and modulate the elongation of its parent gene by

associating with RNA polymerase II (42). While this specific circRNA has not

been studied in gynecological cancer, similar mechanisms could

occur, potentially influencing the expression of key oncogenes or

tumor suppressors. The ability of circRNAs to influence linear mRNA

production through competitive splicing mechanisms may have notable

implications for tumor biology, potentially affecting key oncogenic

or tumor-suppressive pathways. These findings underscore the

potential of circRNAs as key modulators of gene expression in

gynecological malignancies. The complex interplay between circRNA

biogenesis and transcriptional regulation offers new perspectives

on the molecular mechanisms underlying these types of cancer.

Further investigation into this regulatory axis could identify new

targets for therapeutic intervention and contribute to the

understanding of the complex transcriptional landscape in

gynecological cancer. As research in this field progresses, it will

be necessary to elucidate the tissue-specific and cancer-specific

aspects of circRNA-mediated transcriptional regulation. This

knowledge may lead to the development of novel diagnostic tools and

therapeutic strategies tailored to specific gynecological

malignancies, potentially improving patient outcomes.

miRNA sponges

circRNAs have emerged as key regulators of gene

expression in gynecological malignancies, primarily through their

function as miRNA sponges. This mechanism is characterized by the

presence of multiple miRNA binding sites within circRNA molecules,

enabling them to competitively sequester miRNAs (43). By preventing miRNAs from binding to

their target mRNAs, circRNAs effectively reduce the inhibitory

effect of miRNAs on translation, leading to the increased

expression of target genes (44).

This competitive binding phenomenon, known as the ‘miRNA sponge’

effect, represents an important paradigm in post-transcriptional

gene regulation (45). An example

of this regulatory mechanism is circ-cerebellar

degeneration-related protein 1 antisense (CDR1as, also known as

ciRS-7), which has been extensively studied due to its marked

capacity to bind miR-7 (46). While

initially identified in neurological contexts, recent research has

begun to elucidate its potential roles in various types of cancer,

including gynecological tumors (47). For example, in ovarian cancer,

circ_CDR1 has been shown to sponge miR-1270, leading to the

upregulation of suppressor of cancer cell invasion and subsequent

inhibition of tumor progression (48). In the context of gynecological

oncology, the miRNA sponge function of circRNAs has been implicated

in various aspects of tumor biology. For example, in cervical

cancer, circRNA_0000745 may act as a sponge for miR-3178,

upregulating the expression levels of FOXO4 and inhibiting tumor

growth (49). Similarly, in

endometrial cancer, circ_0002577 has been demonstrated to sponge

miR-625-5p, thereby regulating the insulin-like growth factor 1

signaling pathway and influencing tumor progression (50). Understanding these

circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory axes in gynecological malignancies

offers new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor

development and progression. Moreover, it presents potential

opportunities for the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers

and therapeutic targets in gynecological oncology (51).

Protein scaffolds or sponges

In addition to their role as miRNA sponges, circRNAs

have emerged as important regulators of protein function in various

types of cancer, including gynecological malignancies. This

function is primarily achieved through their ability to act as

protein scaffolds or sponges, facilitating or inhibiting

protein-protein interactions and modulating protein activity

(36). A well-characterized example

of this mechanism is circFOXO3, which has been shown to form a

ternary complex with CDK2 and the CDK inhibitor 1, p21. This

interaction effectively inhibits CDK2 function, leading to cell

cycle arrest (52). While initially

studied in cardiac senescence, a research has begun to elucidate

the potential roles of circFOXO3 in gynecological cancer (53). For example, in ovarian cancer,

circFOXO3 has been shown to drive ovarian cancer progression by

orchestrating exosome-mediated intercellular communication

targeting the miR-422a/proteolipid protein 2 axis, potentially

serving as a valuable biomarker for early detection and treatment

monitoring in this aggressive malignancy (54).

Another notable example is circACC1, which forms a

ternary complex with the β and γ regulatory subunits of

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK); this interaction promotes AMPK

holoenzyme activity, enabling cancer cells to adapt to metabolic

stress and grow under nutrient-limited conditions (55). While the specific role of

circ-acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) in gynecological tumors

remains to be fully elucidated, its function in modulating cellular

metabolism suggests potential implications for tumor progression

and therapeutic resistance in these types of cancer (56). In addition, circPUM1 has been shown

to interact with the nuclear receptor binding protein and the

androgen receptor, forming a protein complex that promotes ovarian

cancer cell proliferation and invasion (57). This example highlights the diverse

mechanisms by which circRNAs can influence protein function and

cellular processes in gynecological malignancies. The ability of

circRNAs to act as protein scaffolds or sponges adds another layer

of complexity to their regulatory functions in cancer biology. By

modulating protein-protein interactions and enzyme activities,

circRNAs can influence various cellular processes, including cell

cycle progression, metabolism and signal transduction (58). Understanding these interactions in

the context of gynecological tumors may provide novel insights into

disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets (59).

Translation of peptides

Traditionally, circRNAs were considered to be

non-coding RNAs; however, a recent study demonstrated that, under

specific conditions, some circRNAs can be translated into

functional peptides, adding a new dimension to their role in

cellular processes and disease pathogenesis, including

gynecological malignancies (39).

In a seminal study from 2017, Yang et al (60) provided the first comprehensive

evidence that circRNAs could undergo protein translation following

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification. These findings demonstrated

that m6A-driven circRNA translation is a widespread phenomenon,

with hundreds of endogenous circRNAs possessing translation

potential. This discovery not only expanded the understanding of

the coding capacity of the human transcriptome but also opened

novel avenues for exploring circRNA functions in various diseases,

including gynecological cancer. In the context of gynecological

oncology, the potential for circRNAs to be translated into

functional peptides has significant implications. For example, in

breast cancer, circ-F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7 (FBXW7)

has been shown to encode a novel 21-kDa protein, FBXW7-185aa, which

acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting the proliferation and

migration of cancer cells (61).

Similarly, in cervical cancer, circE7 derived from high-risk human

papillomavirus (HPV) has been shown to encode the E7 oncoprotein,

contributing to the transforming properties of HPV (62). The ability of circRNAs to produce

functional peptides adds another layer of complexity to their

regulatory roles in gynecological malignancies. These peptides may

interact with other cellular components, modulate signaling

pathways or directly influence tumor progression. For example, in

ovarian cancer, the circRNA-encoded peptide SNF2 histone linker PHD

RING helicase (SHPRH)-146aa has been reported to suppress tumor

growth by protecting full-length SHPRH from degradation (63). As research in this field progresses,

elucidating the specific functions of circRNA-encoded peptides in

various types of gynecological cancer will be crucial.

Understanding these novel mechanisms may provide insights into

tumor-specific molecular signatures and identify new options to

develop innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in

gynecological oncology (64).

circRNA and ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is currently the most lethal type of

gynecological malignancy, with a markedly high mortality rate.

Globally, ovarian cancer is responsible for >200,000 deaths

annually (65). The standard

treatment protocol typically involves surgical resection followed

by platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with paclitaxel (PTX)

(66). Despite these interventions,

the prognosis for patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer

remains poor, with a 5-year survival rate of ~30% (67). This poor outcome is largely

attributed to late-stage diagnosis and the development of

chemoresistance (68). The

mechanisms underlying chemoresistance in ovarian cancer are

multifaceted, involving both tumor microenvironment factors and

intrinsic cellular resistance pathways (69). Given these challenges, there is an

urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies and enhance

treatment efficacy to improve patient outcomes. In recent years,

circRNAs have emerged as potential biomarkers and therapeutic

targets in various types of cancer, including ovarian cancer

(70). These unique non-coding RNAs

have been implicated in diverse biological processes, and have

shown promise in modulating chemoresistance and tumor progression

(71). Understanding the role of

circRNAs in ovarian cancer could potentially lead to innovative

diagnostic tools and targeted therapies, addressing the critical

need for improved management of this disease (72).

Mechanistic studies of circRNA in

ovarian cancer

Previous investigations have provided information on

the roles of circRNAs in ovarian cancer progression, unveiling

complex regulatory networks that contribute to tumor development

and metastasis. These studies have identified specific circRNAs and

their associated molecular pathways, providing valuable insights

into potential therapeutic targets (40,73). A

notable discovery by Gan et al (74) demonstrated that circMUC16 can

promote ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion through a

complex regulatory axis. circMUC16 may modulate the expression of

beclin1 and RUNX1 by sponging miR-199a-5p, thereby influencing key

oncogenic processes. This finding not only elucidates a novel

mechanism of ovarian cancer progression but also highlights the

potential of circMUC16 as a therapeutic target. In a separate

study, Li et al (75)

demonstrated the oncogenic role of circ-centrosome and spindle pole

associated protein 1 (CSPP1) in ovarian cancer. This previous study

demonstrated that circCSPP1 can enhance cancer progression by

counteracting the tumor-suppressive effects of miR-1236-3p on ZEB1,

a key transcription factor involved in epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT). In addition, circCSPP1 depletion was shown to

inhibit tumor growth, whereas its overexpression could upregulate

oncogenic proteins, further emphasizing its significance in ovarian

cancer pathogenesis. These mechanistic studies underscore the

complex interplay between circRNAs and their downstream targets in

ovarian cancer. However, the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer

involves multifaceted mechanisms, and circRNA research, while

promising, represents only one aspect of this intricate disease

landscape. Further comprehensive investigations are required to

fully elucidate the role of circRNAs in ovarian cancer and to

translate these findings into clinically relevant applications

(76). As research in this field

progresses, integrating circRNA studies with other aspects of

cancer biology, such as genomics, proteomics and metabolomics, may

provide a more holistic understanding of ovarian cancer

pathogenesis, and identify novel diagnostic and therapeutic

strategies (77).

Diagnostic value of circRNA in ovarian

cancer

circRNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers for

ovarian cancer diagnosis, offering unique advantages due to their

stability and tissue-specific expression patterns. A previous study

highlighted the potential of circRNAs in early detection, disease

staging and prognostic prediction for patients with ovarian cancer;

Ahmed et al (78) pioneered

the comprehensive analysis of circRNA expression profiles in

ovarian cancer. This study demonstrated a significantly higher

number of differentially expressed circRNAs in metastatic tissues

compared with that in primary lesions, in contrast to linear mRNA

patterns. Notably, circRNA expression showed negative correlation

with linear mRNA in key signaling pathways, such as NF-κB and

PI3K/AKT. These findings underscore the consistency and stability

of circRNA expression, suggesting the potential for circRNAs as

robust biomarkers for ovarian cancer detection and progression

monitoring. Further research by Pei et al (79) identified hsa_circ_0013958 as a

highly expressed circRNA in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines.

hsa_circ_0013958 demonstrated a strong association with disease

stage and lymph node metastasis, highlighting its potential as a

diagnostic and prognostic marker. Several survival analyses have

corroborated the clinical relevance of circRNA expression in

ovarian cancer (76,80). Abnormal expression levels of

specific circRNAs, including hsa_circ_0078607, circ-la

ribonucleoprotein 4 (LARP4) and circFAM53B, have been closely

linked to pathological stage and poor prognosis (81). These findings suggest that circRNA

expression profiles could serve as valuable prognostic indicators

for patients with ovarian cancer. The current lack of accurate

screening and early diagnostic methods for ovarian cancer

underscores the urgent need for novel biomarkers. In-depth research

on circRNAs offers a promising avenue for developing early

detection strategies for ovarian lesions. By enabling timely

diagnosis and treatment initiation, circRNA-based diagnostics could

potentially improve patient survival rates (82). As research in this field progresses,

integrating circRNA biomarkers with existing diagnostic tools may

enhance the accuracy and reliability of ovarian cancer detection.

Moreover, the tissue-specific nature of circRNA expression could

facilitate the development of personalized diagnostic and

prognostic approaches, tailored to the molecular profiles of

individual patients (83).

Therapeutic value of circRNA in

ovarian cancer

Recent advances in circRNA research have revealed

the promising therapeutic potential of circRNA in ovarian cancer

treatment. These unique non-coding RNAs have been demonstrated to

possess the ability to modulate various oncogenic pathways,

offering new avenues for targeted therapies (84,85).

Notably, Lu et al (86)

investigated the tumor-suppressive role of circLARP4 in ovarian

cancer and elucidated that circLARP4 can inhibit ovarian cancer

progression through the miR-513b-5p/LARP4 axis. This finding not

only sheds light on the complex regulatory networks in ovarian

cancer but also presents circLARP4 as a potential therapeutic

target. Further research has focused on circ-itchy E3 ubiquitin

protein ligase (ITCH), another circRNA with notable antitumor

properties in ovarian cancer. Overexpression of circITCH has been

shown to significantly suppress cell proliferation and to promote

apoptosis through direct interaction with miR-10a, by acting as a

ceRNA and regulating the circITCH/miR-145/RASA1 axis. These

mechanisms have been shown to effectively inhibit ovarian cancer

cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo

(87). The dual functionality of

circITCH underscores its potential as a versatile therapeutic

agent. The emerging understanding of these circRNA-mediated tumor

suppression mechanisms demonstrates novel possibilities for ovarian

cancer treatments. By targeting specific circRNAs or their

downstream pathways, it may be possible to develop more effective

and less toxic therapeutic strategies (88). Moreover, the tissue-specific

expression patterns of circRNAs offer the potential for highly

targeted therapies with reduced off-target effects. This

characteristic could be particularly beneficial in developing

personalized treatment approaches for patients with ovarian cancer

(2). As research in this field

progresses, it is essential to further investigate the safety and

efficacy of circRNA-based therapies. Future studies should focus on

optimizing delivery methods, understanding potential side effects

and exploring combination therapies with existing treatment

modalities (89). The therapeutic

value of circRNAs in ovarian cancer is increasingly evident. These

molecules offer promising targets for developing novel treatment

strategies that could potentially improve outcomes for patients

with this type of malignancy.

Potential of circRNA as a vaccine

candidate in ovarian cancer

circRNAs have emerged as promising candidates for

cancer vaccines, with potential applications extending to ovarian

cancer. Their unique stability and capacity for durable protein

expression make them particularly suitable for vaccine development,

offering potential options in the field of hard-to-treat

malignancies. Li et al (90)

demonstrated the efficacy of circRNA cancer vaccines in driving

immunity against challenging types of cancer. This previous study

established a novel circRNA vaccine platform by encapsulating

antigen-coding circRNA in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). This

innovative approach triggered robust innate and adaptive immune

activation, showing superior antitumor efficacy in multiple mouse

tumor models. Furthermore, the circRNA-LNP vaccine exhibited higher

stability and initiated more durable protein expression than its

linear counterpart in vitro; in vivo, the circRNA-LNP

vaccine elicited marked innate immune responses and potent

antigen-specific T-cell responses, comparable to modified mRNA-LNP

vaccines. While specific studies on circRNA vaccines for ovarian

cancer are currently limited, the potential is considerable.

Certain circRNAs, such as circ-Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1

(WHSC1), have been identified as being highly expressed in ovarian

cancer tissues, and serve crucial roles in cancer cell

proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion (91). These circRNAs could potentially

serve as targets for vaccine development. The ability of circRNAs

to regulate key cancer-related proteins, such as MUC1 and hTERT in

the case of circWHSC1, provides a molecular basis for their

potential as vaccine candidates. However, it is important to note

that the application of circRNA vaccines in ovarian cancer is still

in its early stages. Further research is needed to identify ovarian

cancer-specific circRNAs suitable for vaccine development and to

optimize circRNA-LNP formulations for maximum efficacy in ovarian

cancer models. In addition, the safety and immunogenicity of

circRNA vaccines should be evaluated in preclinical ovarian cancer

studies, and potential combinations with existing immunotherapies

or targeted treatments should be investigated. As research

progresses, the unique properties of circRNAs, such as their

resistance to exonuclease degradation and ability to be translated

into proteins without 5′ capping or polyadenylation, may prove

advantageous in developing effective and long-lasting vaccines

against ovarian cancer (20). While

specific applications in ovarian cancer require further

investigation, the initial results of circRNA vaccines in other

cancer models are promising and could potentially revolutionize

immunotherapy strategies for ovarian cancer in the future (92).

circRNA and endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is a significant health concern,

ranking as the second most prevalent gynecological malignancy in

China and the foremost in developed nations. In 2022, China

reported ~84,520 new cases of endometrial cancer (93). Various risk factors have been

associated with this type of cancer, including obesity, diabetes,

polycystic ovary syndrome, infertility, early menarche and late

menopause (94). Current screening

methods for endometrial cancer primarily rely on transvaginal

ultrasound, hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy (95). However, these techniques have the

following limitations: Transvaginal ultrasound results can be

subjective, whereas hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy are

invasive procedures, restricting their widespread use in clinical

screening (96). The standard

treatment approach for endometrial cancer typically involves

surgery followed by chemotherapy, often using a combination of

carboplatin and PTX (97). Despite

these interventions, challenges persist, including poor prognosis

and drug resistance in some cases (98). Given these challenges, there is a

pressing need to explore novel diagnostic and therapeutic

strategies to enhance survival rates for patients with endometrial

cancer. circRNAs have emerged as promising candidates in this

regard. These unique RNA molecules, characterized by their

covalently closed loop structure, have shown potential in both the

diagnosis and treatment of various types of cancer, including

endometrial cancer (99). A

previous study demonstrated that circRNAs serve key roles in

endometrial cancer pathogenesis, influencing cell proliferation,

invasion and metastasis (100).

Moreover, certain circRNAs have been identified as potential

biomarkers for early detection and prognostic prediction in

endometrial cancer (101). The

exploration of circRNA-based therapeutic approaches, such as

circRNA-mediated gene therapy or circRNA-targeted drug delivery

systems, represents a notable option in endometrial cancer research

(102).

Mechanistic studies of circRNA in

endometrial cancer

A previous study has provided valuable insights into

the biogenesis mechanisms of circRNAs, which can be categorized

into three main models: The intron pairing model, the exon skipping

model and the RBP model. The intron pairing model posits that

complementary sequences within introns form stable secondary

structures, such as hairpins, which facilitate back-splicing and

the formation of circRNAs (103).

In endometrial cancer, the intron pairing model may explain the

high expression levels of specific circRNAs, such as circTNFRSF21,

which is significantly upregulated and competes with miR-1227 to

activate the MAPK13/ATF2 signaling pathway, promoting cancer cell

proliferation and cell cycle progression (104). Similarly, overexpression of

circWHSC1, driven by intron pairing, enhances cell proliferation,

migration and invasion while inhibiting apoptosis (105). The exon skipping model suggests

that certain exons are skipped during the normal linear splicing

process, leading to the formation of circRNAs (106). In endometrial cancer,

hsa_circ_0061140 is formed through exon skipping and interacts with

miR-149-5p to upregulate STAT3, thereby promoting cancer

progression and migration (107).

The RBP model involves the direct modulation of back-splicing by

specific RBPs, such as Quaking and Muscleblind. In endometrial

cancer, the abnormal expression of these proteins may contribute to

the biogenesis of circRNAs like circWHSC1 and hsa_circ_0061140,

influencing cancer development (3).

Diagnostic value of circRNA in

endometrial cancer

Previous studies have highlighted the potential of

circRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in endometrial cancer. These

investigations have demonstrated distinctive circRNA expression

patterns in cancer tissues, offering novel potential for early

detection and prognostic prediction (102,108). In 2019, Ye et al (104) used sequencing techniques to

compare circRNA expression profiles in stage III endometrial cancer

tissues with adjacent non-cancerous endometrial tissues;

significant differential expression of circRNAs between these

tissue types was demonstrated. Through bioinformatics analysis, it

was identified that the

hsa_circ_0039659/hsa-miR-542-3p/hsa-let-7c-5p pathway may be a

critical predictor for stage III endometrial cancer. This discovery

not only enhances the understanding of the molecular mechanisms

underlying endometrial cancer progression but also presents a

potential diagnostic tool for advanced-stage disease. Further

supporting the diagnostic value of circRNAs, Chen et al

(109) noted that, while no

significant difference in the number of linear RNA transcripts was

detected between endometrial cancer tissues and healthy tissues, a

marked reduction in circRNA levels was observed within cancer

tissues. The comprehensive analysis identified ~120 differentially

expressed circRNAs, which may contribute to the susceptibility of

endometrial tissues to carcinogenesis. This distinct circRNA

signature in cancer tissues underscores the potential of these

molecules as specific and sensitive biomarkers for endometrial

cancer. These findings collectively suggest that circRNAs hold

considerable promise as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for

endometrial cancer. The unique expression patterns of circRNAs in

cancer tissues, coupled with their stability and tissue-specific

expression, make them attractive candidates for non-invasive

diagnostic tests. Moreover, the identification of specific

circRNA-miRNA-mRNA pathways, such as the

hsa_circ_0039659/hsa-miR-542-3p/hsa-let-7c-5p axis, provides

possibilities for targeted therapies and personalized medicine

approaches. Future research should focus on validating these

findings in larger, diverse patient cohorts and exploring the

potential of circRNA-based liquid biopsies for the early detection

of endometrial cancer. Additionally, investigating the functional

roles of these differentially expressed circRNAs may provide deeper

insights into the pathogenesis of endometrial cancer and identify

new therapeutic targets.

Therapeutic value of circRNA in

endometrial cancer

Advances in circRNA research have demonstrated

promising therapeutic potential in endometrial cancer. A notable

discovery in this field is the identification of hsa_circ_0001860,

a novel circRNA associated with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA)

resistance in patients with endometrial cancer. This circRNA has

been shown to be negatively correlated with histological grade and

lymph node metastasis, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for

disease progression and treatment response (110). Further investigation into the

molecular mechanisms of hsa_circ_0001860 has reported a role in

regulating SMAD7 expression levels and activating the SMAD7/EMT

signaling pathway. Notably, hsa_circ_0001860 has been shown to

enhance cancer cell sensitivity to MPA by targeting miR-520h.

Experimental studies have demonstrated that overexpression of

hsa_circ_0001860, coupled with miR-520h knockdown, can

significantly increase cellular sensitivity to MPA treatment. These

findings highlight the potential of hsa_circ_0001860 as a

therapeutic target for MPA-resistant endometrial cancer (110). By modulating hsa_circ_0001860, it

may be possible to overcome drug resistance and improve treatment

outcomes in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer.

This approach aligns with the growing interest in circRNAs as both

diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in various types of

cancer, including endometrial cancer (111). The discovery of hsa_circ_0001860

and its role in MPA resistance provides novel options for

personalized medicine in endometrial cancer treatment. Future

research should focus on developing strategies to manipulate this

circRNA in vivo and to assess its efficacy in clinical

settings. Additionally, exploring the interactions between

hsa_circ_0001860 and other molecular pathways involved in

endometrial cancer progression could provide a more comprehensive

understanding of its therapeutic potential. As knowledge regarding

circRNA biology is improved, it is likely that more circRNAs with

therapeutic value in endometrial cancer will be identified. This

emerging field offers possibilities for improving endometrial

cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment, potentially leading to

more effective and targeted therapies for patients with this

malignancy.

Potential as a vaccine candidate in

endometrial cancer

circRNAs have emerged as promising molecules in

cancer research, particularly for gynecological malignancies such

as endometrial cancer. Initially recognized for their potential as

biomarkers and therapeutic targets, recent advances have

highlighted circRNAs as novel vaccine candidates (112). The unique properties of circRNAs,

including high stability and resistance to exonuclease-mediated

degradation, make them attractive for vaccine development (113). The covalently closed structure

circRNAs enables efficient protein expression and potentially

allows for rolling circle translation. When engineered and

encapsulated in LNPs, circRNA vaccines have demonstrated the

ability to elicit robust innate and adaptive immune responses,

showing superior antitumor efficacy in preclinical models (114). Research has indicated that

circRNA-LNP complexes can induce potent antigen-specific T-cell

responses, which are crucial for combating solid tumors such as

endometrial cancer (115). The

circRNA vaccine platform offers an innovative approach for

developing cancer RNA vaccines that may be particularly applicable

to endometrial cancer, which is often considered challenging to

treat. The potential of circRNA vaccines extends beyond

monotherapy; a previous study suggested that circRNA-based

approaches may serve as both primary and adjuvant therapies,

potentially synergizing with existing immunotherapies to combat

obesity-related endometrial cancer (116). For example, a circRNA OVA-luc-LNP

vaccine has exhibited efficacy in suppressing immune-exclusive

tumor progression, inducing regression in immune-desert tumors and

preventing metastasis (90).

Compared with traditional mRNA vaccines, circRNA vaccines

demonstrate superior stability, prolonged protein expression and

the ability to initiate robust immune responses without nucleotide

modifications (117). These

characteristics position circRNA vaccines as a promising

alternative in cancer immunotherapy and have potential to improve

endometrial cancer treatment and outcomes in the future. The

ability of circRNA vaccines to collaborate with adoptive cell

transfer therapy and to suppress late-stage immune-exclusive tumor

progression by enhancing T-cell receptor T-cell therapy (TCR-T)

cell persistence demonstrates their potential as a cancer therapy

(90). Further investigation into

circRNA vaccines for endometrial cancer is warranted, as it could

lead to novel therapies. The unique properties of circRNAs,

combined with their potential for enhanced translation efficiency

through engineering, position them as a promising option in

effective cancer vaccine development.

circRNA and cervical cancer

Cervical cancer remains a notable health issue for

women worldwide, ranking as the second most common malignancy after

breast cancer. It is also associated with a high mortality rate,

being a leading cause of global cancer-related mortality.

Persistent infection with HPV is the primary driver of cervical

cancer progression. In China, cervical cancer mortality is slightly

higher in rural areas than in urban regions, with midwestern areas

exhibiting mortality rates about twice those in eastern regions

(118). Additionally, recent

trends have indicated a decreasing average age of onset for

cervical cancer, suggesting a rise in incidence among younger women

(119,120). Current treatments for cervical

cancer typically involve a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and

radiotherapy. However, poor prognosis and low survival rates due to

distant metastasis and lymphatic spread continue to challenge

patient outcomes (121). Thus,

there is an urgent need to identify new therapeutic approaches and

early diagnostic biomarkers to improve survival rates. circRNAs

have garnered significant attention in cancer research due to their

unique properties, including high stability and resistance to

exonuclease-mediated degradation (122). These characteristics make circRNAs

promising candidates for developing novel therapeutic strategies

and diagnostic tools for cervical cancer (123). Studies have suggested that

circRNAs can serve as effective biomarkers for early detection and

may offer new opportunities for targeted therapies (5,124).

For example, some circRNAs (including circ_0010235 and circCCDC66)

have been shown to interact with miRNAs and proteins involved in

cancer pathways, influencing tumor growth and metastasis (125). The potential application of

circRNA-based therapies could lead to more effective treatment

options for cervical cancer, addressing the current limitations of

conventional therapies. Research into the role of circRNAs in

cervical cancer is still in its early stages but holds promise.

Advances in circRNA studies may identify breakthrough therapies,

improving prognosis and survival rates for patients with cervical

cancer (Table II).

| Table II.Summary of potential circRNA

biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cervical cancer. |

Table II.

Summary of potential circRNA

biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cervical cancer.

| circRNA | Expression

change | Potential as

biomarker | Potential as a

therapeutic target | Related

mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

|

hsa_circ_0000745 | Upregulated | Diagnostic

marker | Inhibition of tumor

progression | Regulates

miR-3178/E2F3 signaling pathway | (49) |

| circMYBL2 | Upregulated | Early diagnostic

marker | Inhibition of tumor

growth | Regulates FUS/EGFR

signaling pathway | (132) |

|

hsa_circ_0023404 | Upregulated | High (negatively

correlated with overall survival) | High | Promotes cancer

development by sponging miR-136, leading to increased expression of

TFCP2 and subsequent activation of the YAP pathway | (126) |

| circ_0005576 | Upregulated | High | High | Promotes cell

proliferation and metastasis by sponging miR-153-3p and promoting

kinesin family member 20A expression | (128) |

| circFOXO3a | Downregulated in

serum | High (lower levels

associated with lymph node metastasis and deeper stromal

invasion) | Potential (complex

role) | Lower serum levels

associated with higher overall survival and recurrence-free

survival | (130) |

| circATP8A2 | Upregulated | High (associated

with advanced FIGO stage and myometrial invasion depth) | Potential | Upregulation

closely related to disease severity and progression | (131) |

Mechanistic studies of circRNA in

cervical cancer

Previous research has unveiled significant roles of

circRNAs in the pathogenesis and progression of cervical cancer,

offering novel insights into potential diagnostic and therapeutic

approaches (47). Notably, survival

analyses on hsa_circ_0023404 demonstrated an inverse correlation

between hsa_circ_0023404 expression and overall patient survival,

with higher expression levels associated with poorer outcomes.

Mechanistically, hsa_circ_0023404 functions as a miRNA sponge,

specifically targeting miR-136. This interaction led to increased

expression levels of the transcription factor CP2 and subsequent

activation of the YAP pathway, ultimately driving cancer

progression (126). Another

notable circRNA, circ_0005576, has been shown to be markedly

upregulated in cervical cancer tissues. Localized in the cytoplasm,

this circRNA serves a key role in cell proliferation and metastasis

(127). Functional studies have

demonstrated that knockdown of circ_0005576 can inhibit these

malignant behaviors, while its overexpression may enhance them. The

underlying mechanism involves circ_0005576 sponging miR-153-3p,

thereby promoting the expression of KIF20A, a key player in cancer

cell division and movement (128).

Given that HPV infection is the primary etiological factor in

cervical cancer, exploring the interplay between HPV and circRNAs

presents a promising avenue for future research. Understanding

these relationships could potentially identify novel therapeutic

targets and strategies for cervical cancer treatment (129). These mechanistic studies highlight

the complex regulatory networks involving circRNAs in cervical

cancer and underscore their potential as both biomarkers and

therapeutic targets. Further investigation into the functional

roles of circRNAs and their interactions with other molecular

players in cervical cancer pathogenesis is warranted to fully

harness their clinical potential.

Diagnostic value of circRNA in

cervical cancer

circRNAs have emerged as promising diagnostic and

prognostic biomarkers in cervical cancer due to their stability and

tissue-specific expression patterns. A previous study highlighted

the potential of specific circRNAs in predicting disease

progression and patient outcomes; Tang et al (130) demonstrated that lower serum levels

of circFoxO3a are associated with positive lymph node metastasis

and increased depth of stromal invasion in patients with cervical

cancer. Notably, patients with lower circFOXO3a serum levels

exhibited higher overall survival and relapse-free survival rates,

suggesting its complex role in cancer progression and its potential

as a prognostic marker. Further emphasizing the diagnostic

potential of circRNAs, Ding and Zhang (131) identified circ-ATPase phospholipid

transporting 8A2 (ATP8A2) as being significantly upregulated in

both cervical cancer tissues and cell lines. This finding indicated

that elevated levels of circATP8A2 may be strongly associated with

advanced International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

staging and the degree of myometrial invasion. This association

underscores the potential of circATP8A2 as a biomarker for disease

severity and progression. These studies collectively demonstrate

the promising role of circRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic

biomarkers in cervical cancer. The differential expression of

circRNAs such as circFOXO3a and circATP8A2 in relation to

clinicopathological features offers new avenues for non-invasive

diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies. However, further

large-scale clinical studies are required to validate these

findings and to establish standardized protocols for circRNA-based

diagnostics in cervical cancer management.

Therapeutic value of circRNA in

cervical cancer

Previous research has unveiled the potential of

circRNAs as therapeutic targets in cervical cancer, particularly in

addressing drug resistance. In a novel study from 2021, Dong et

al (132) provided information

on the role of circMYBL2 in PTX resistance, a common challenge in

cervical cancer treatment, demonstrating that circMYBL2 may serve a

key role in modulating the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to

PTX. Overexpression of circ-MYB proto-oncogene like 2 (MYBL2) was

found to significantly reduce the growth-inhibitory effects of PTX

on cancer cells; by contrast, the knockdown of circMYBL2 enhanced

the efficacy of PTX, demonstrating its potential as a therapeutic

target. The mechanism underlying this effect was shown to involve

the regulation of miR-665; the study showed that overexpression or

inhibition of miR-665 could reverse the effects of circMYBL2 on PTX

sensitivity. These findings suggest that circMYBL2 functions as a

positive regulator of drug resistance and malignant behavior in

cervical cancer cells through its interaction with miR-665. This

discovery provides novel options for developing targeted therapies

for patients with PTX-resistant cervical cancer. By manipulating

circMYBL2 levels or disrupting its interaction with miR-665, it may

be possible to re-sensitize resistant tumors to PTX treatment. The

identification of circMYBL2 as a key player in drug resistance

highlights the broader potential of circRNAs as therapeutic targets

in cervical cancer. This research not only provides insights into

the mechanisms of drug resistance but also offers a promising

strategy for overcoming this notable clinical challenge. Future

studies may focus on developing circRNA-based therapeutics or using

circMYBL2 as a biomarker for predicting PTX response in patients

with cervical cancer (133).

Several other circRNAs, such as circEIF4G2 (134) and circ_0006528 (135), have also been implicated in

cervical cancer progression and drug resistance, further

highlighting the therapeutic potential of circRNAs in this

malignancy.

Potential as a vaccine candidate in

cervical cancer

Advances in circRNA research have demonstrated

potential for their application as cancer vaccines, including for

cervical cancer. This approach leverages the unique properties of

circRNAs to stimulate robust immune responses against malignancies.

For example, Niu et al (136) demonstrated the ability of a

circRNA-based cancer vaccine to induce potent innate and adaptive

immune responses in preclinical models, showcasing its therapeutic

potential against types of difficult-to-treat cancer. For instance,

combining circRNA-LNP vaccines with adoptive T cell transfer (OT-I

cells) achieved complete tumor regression in all treated mice with

advanced B16-OVA melanoma, while monotherapy (circRNA vaccine

alone) resulted in 60% survival. This combination strategy extended

survival beyond 60 days in 100% of mice, compared with rapid

mortality in control groups. The potential mechanism is illustrated

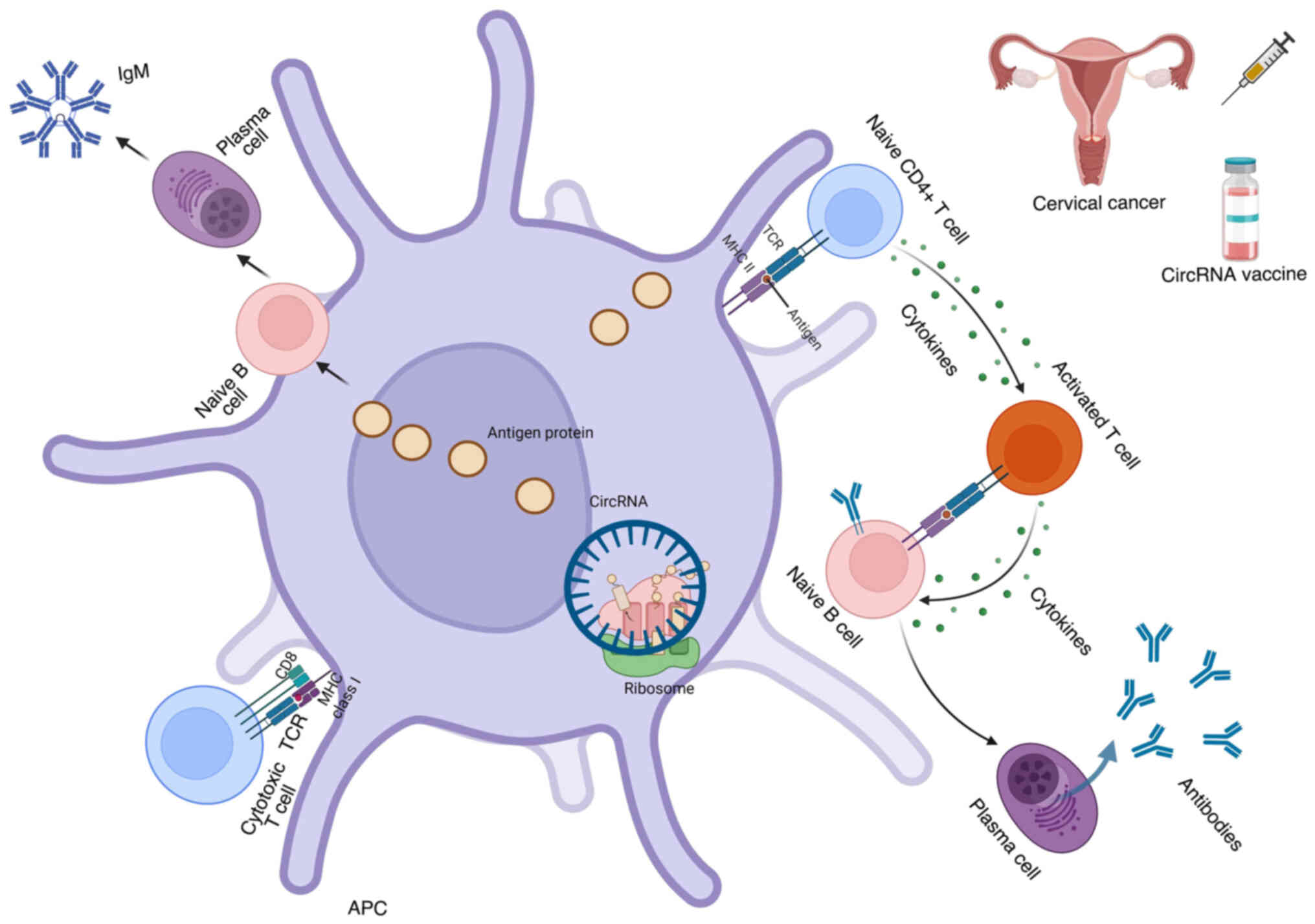

in Fig. 1.

While direct studies on circRNA-based vaccines for

cervical cancer are limited, research on the role of circRNAs in

cervical cancer progression provides valuable insights into their

potential as vaccine candidates. For example, Ou et al

(137) reported that circAMOTL1

can promote cervical cancer growth by acting as a sponge for

miR-485-5p, leading to increased AMOTL1 levels. This finding

highlights the possibility of targeting specific circRNAs involved

in cancer progression for vaccine development. Furthermore, Wang

et al (138) emphasized the

significance of genome-wide perturbations in A-to-I RNA editing in

dysregulating circRNAs and promoting cervical cancer development.

This previous study identified three RNA editing sites as potential

biomarkers or therapeutic targets, underscoring the therapeutic

potential of focusing on RNA editing dysregulation in cervical

cancer treatment. The unique stability and tissue-specific

expression patterns of circRNAs make them attractive candidates for

vaccine development. By designing circRNA vaccines that encode

specific tumor antigens or target circRNAs involved in cervical

cancer progression, researchers may be able to elicit more targeted

and effective immune responses against this disease. While these

findings are promising, it is important to note that the

development of circRNA-based vaccines for cervical cancer is still

in its early stages. Further research is needed to fully elucidate

the mechanisms by which circRNA vaccines stimulate antitumor

immunity, and to optimize their delivery and efficacy in clinical

settings. Nonetheless, the potential of circRNAs as vaccine

candidates offers a potential new option for cervical cancer

immunotherapy, which may lead to more effective and personalized

treatment strategies in the future.

Challenges and limitations of

circRNA-based therapies for gynecological cancer

CircRNAs hold potential as therapeutic tools;

however, efficiently and safely translating them into effective

treatments requires addressing several critical challenges. Despite

the significant potential of circRNAs, efficient and safe delivery

remains a major challenge. Current strategies for delivering

circRNAs include lipid nanoparticles, viral vectors and exosomes.

Each of these delivery systems has its limitations. For instance,

viral vectors, while highly efficient, can trigger immune responses

or insertional mutagenesis (139).

Lipid nanoparticles, on the other hand, require further

optimization for stability and tissue specificity (140). Additionally, ensuring that

circRNAs are delivered to tumor sites while minimizing their

accumulation in non-targeted tissues is a pressing issue (141).

The ability of circRNAs to regulate gene expression

by interacting with miRNAs and RBPs can also lead to non-specific

targeting effects, causing off-target effects. circRNAs may

simultaneously regulate multiple miRNAs, thereby affecting multiple

signaling pathways and leading to unintended biological

consequences (124). Therefore, in

developing circRNA therapies, extensive in vivo studies and

high-throughput screening are necessary to ensure the specificity

of their targeting effects while avoiding interference with normal

cellular functions (142).

The clinical translation of circRNA therapies also

depends on strict regulatory requirements. As an emerging

biotherapeutic tool, circRNAs must meet the standards of

international drug regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and

Drug Administration. Research on the long-term safety,

immunogenicity and metabolic pathways of circRNA drugs is still in

its early stages. Before circRNA therapies can be used clinically,

uniform quality control standards must be established, and rigorous

preclinical and clinical trials must be conducted to ensure their

safety and efficacy (143).

Conclusion

The emerging field of circRNA research offers

promising options for advancing the understanding and management of

gynecological malignancies. The present review has highlighted the

diverse roles of circRNAs in ovarian, endometrial and cervical

cancer, from their involvement in tumor progression to their

potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. The unique

properties of circRNAs, including their stability, tissue-specific

expression and diverse regulatory functions, position them as

valuable tools in gynecological oncology. The roles of circRNAs as

miRNA sponges, protein scaffolds and even potential peptide

encoders underscore their complex involvement in cancer

pathogenesis. While notable progress has been made in elucidating

the functions of circRNAs in gynecological cancer, much remains to

be explored. Future research should focus on validating

circRNA-based biomarkers, investigating tissue-specific and

cancer-specific circRNA-mediated transcriptional regulation,

exploring the therapeutic potential of targeting circRNAs and

elucidating the functional significance of circRNA-encoded peptides

in gynecological cancer. As the understanding of circRNAs in

gynecological malignancies improves, the development of novel

diagnostic tools, prognostic markers and targeted therapies is

anticipated. These advances hold the potential to markedly improve

patient outcomes and to reshape the landscape of gynecological

cancer management.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was provided financial support from the

following projects: the scholarship under the China Scholarship

Council (grant no. 202308210316), Liaoning Province Science and

Technology Program Joint Program Fund Project (grant no.

2023-MSLH-059), Postgraduate Education Teaching Research and Reform

Project of Jinzhou Medical University (grant no. YJ2023-018), Jie

Bang Gua Shuai Project of Science & Technology Department of

Liaoning Province (grant no. 2022JH1/10800070) and Basic Scientific

Research Project of Colleges and Universities of Education

Department of Liaoning Province (key project) (grant no.

1821240403).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author's contributions

YL was responsible for writing the manuscript and

investigation of the subject, such as conducting literature reviews

to understand the current state of research. HA edited,

conceptualized and supervised the present study. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Conn VM, Chinnaiyan AM and Conn SJ:

Circular RNA in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 24:597–613. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Qin M, Zhang C and Li Y: Circular RNAs in

gynecologic cancers: Mechanisms and implications for chemotherapy

resistance. Front Pharmacol. 14:11947192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kristensen LS, Andersen MS, Stagsted LVW,

Ebbesen KK, Hansen TB and Kjems J: The biogenesis, biology and

characterization of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 20:675–691. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang J, Luo Z, Zheng Y, Duan M, Qiu Z and

Huang C: CircRNA as an Achilles heel of cancer: Characterization,

biomarker and therapeutic modalities. J Transl Med. 22:7522024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zong ZH, Du YP, Guan X, Chen S and Zhao Y:

CircWHSC1 promotes ovarian cancer progression by regulating MUC1

and hTERT through sponging miR-145 and miR-1182. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 38:4372019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li Y, Yang Z, Zeng M, Wang Y, Chen X, Li

S, Zhao X and Sun Y: Circular RNA differential expression profiles

and bioinformatics analysis of hsa_circRNA_079422 in human

endometrial carcinoma. J Obstet Gynaecol. 43:22288942023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Heidari-Ezzati S, Moeinian P,

Ahmadian-Nejad B, Maghbbouli F, Abbasi S, Zahedi M, Afkhami H,

Shadab A and Sajedi N: The role of long non-coding RNAs and

circular RNAs in cervical cancer: Modulating miRNA function. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 12:13087302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lei B, Tian Z, Fan W and Ni B: Circular

RNA: A novel biomarker and therapeutic target for human cancers.

Int J Med Sci. 16:292–301. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

He AT, Liu J, Li F and Yang BB: Targeting

circular RNAs as a therapeutic approach: Current strategies and

challenges. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:1852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Misir S, Wu N and Yang BB: Specific

expression and functions of circular RNAs. Cell Death Differ.

29:481–491. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ

and Kleinschmidt AK: Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed

circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like

structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 73:3852–3856. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hsu MT and Coca-Prados M: Electron

microscopic evidence for the circular form of RNA in the cytoplasm

of eukaryotic cells. Nature. 280:339–340. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N and

Brown PO: Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from

hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS One.

7:e307332012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nisar S, Bhat AA, Singh M, Karedath T,

Rizwan A, Hashem S, Bagga P, Reddy R, Jamal F, Uddin S, et al:

Insights into the role of CircRNAs: Biogenesis, characterization,

functional, and clinical impact in human malignancies. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 9:6172812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Papadopoulos N and Trifylli EM: Role of

exosomal circular RNAs as microRNA sponges and potential targeting

for suppressing hepatocellular carcinoma growth and progression.

World J Gastroenterol. 30:994–998. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Panda AC: Circular RNAs Act as miRNA

sponges. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1087:67–79. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hentze MW and Preiss T: Circular RNAs:

Splicing's enigma variations. EMBO J. 32:923–925. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Legnini I, Di Timoteo G, Rossi F, Morlando

M, Briganti F, Sthandier O, Fatica A, Santini T, Andronache A, Wade

M, et al: Circ-ZNF609 Is a circular RNA that can be translated and

functions in myogenesis. Mol Cell. 66:22–37.e9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen YG, Chen R, Ahmad S, Verma R, Kasturi

SP, Amaya L, Broughton JP, Kim J, Cadena C, Pulendran B, et al:

N6-methyladenosine modification controls circular RNA immunity. Mol

Cell. 76:96–109.e9. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang Y, Mo Y, Gong Z, Yang X, Yang M,

Zhang S, Xiong F, Xiang B, Zhou M, Liao Q, et al: Circular RNAs in

human cancer. Mol Cancer. 16:252017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tashakori N, Mikhailova MV, Mohammedali

ZA, Mahdi MS, Ali Al-Nuaimi AM, Radi UK, Alfaraj AM and Kiasari BA:

Circular RNAs as a novel molecular mechanism in diagnosis,

prognosis, therapeutic target, and inhibiting chemoresistance in

breast cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 263:1555692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Holdt LM, Kohlmaier A and Teupser D:

Circular RNAs as therapeutic agents and targets. Front Physiol.

9:12622018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ragan C, Goodall GJ, Shirokikh NE and

Preiss T: Insights into the biogenesis and potential functions of

exonic circular RNA. Sci Rep. 9:20482019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang T, Zhang X and Zheng B:

Identification of intronic lariat-derived circular RNAs in

arabidopsis by RNA deep sequencing. Methods Mol Biol. 2362:93–100.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhong Y, Yang Y, Wang X, Ren B, Wang X,

Shan G and Chen L: Systematic identification and characterization

of exon-intron circRNAs. Genome Res. 34:376–393. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang XO, Dong R, Zhang Y, Zhang JL, Luo

Z, Zhang J, Chen LL and Yang L: Diverse alternative back-splicing

and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Res.

26:1277–1287. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Guo Z, Cao Q, Zhao Z and Song C:

Biogenesis, features, functions, and disease relationships of a

specific circular RNA: CDR1as. Aging Dis. 11:1009–1020. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhu J, Li Q, Wu Z, Xu W and Jiang R:

Circular RNA-mediated miRNA sponge & RNA binding protein in

biological modulation of breast cancer. Noncoding RNA Res.

9:262–276. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Conn SJ, Pillman KA, Toubia J, Conn VM,

Salmanidis M, Phillips CA, Roslan S, Schreiber AW, Gregory PA and

Goodall GJ: The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of

circRNAs. Cell. 160:1125–1134. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK,

Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF and Sharpless NE: Circular RNAs are

abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA.

19:141–157. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Pisignano G, Michael DC, Visal TH, Pirlog

R, Ladomery M and Calin GA: Going circular: History, present, and

future of circRNAs in cancer. Oncogene. 42:2783–2800. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhao X, Zhong Y, Wang X, Shen J and An W:

Advances in circular RNA and its applications. Int J Med Sci.

19:975–985. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li L, Wei C, Xie Y, Su Y, Liu C, Qiu G,

Liu W, Liang Y, Zhao X, Huang D and Wu D: Expanded insights into

the mechanisms of RNA-binding protein regulation of circRNA

generation and function in cancer biology and therapy. Gen Dis.