Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most

common mesenchymal tumors occurring in the gastrointestinal tract

(1), with an annual incidence is up

to 10 to 15 cases per million individuals (2–6). The

prognosis of GIST is associated with the tumor size and mitotic

index, and median overall survival ranged from 47 to 57 months

(2–6). Curative resection is advised for most

patients with GISTs but not for those with locally advanced GISTs

(LAGISTs), which are unsuitable for radical resection, those for

whom resection presents risks of substantial organ dysfunction or

those whose GISTs are borderline unresectable (2–6).

Mutations in the genes encoding the receptor

tyrosine-protein kinase KIT (KIT) and platelet-derived

growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα) may prompt considerations

of treatment with first-line imatinib therapy (2–7).

Imatinib inhibits GIST progression by targeting KIT and

PDGFRα. This preoperative treatment modality can be employed

in cases of LAGISTs that are unresectable or borderline

unresectable. First-line imatinib therapy can enable surgical

resection and minimize the risk of tumor spillage or bleeding

during surgery. However, whether imatinib can be used to treat

LAGIST with exon mutations of KIT and PDGFRα genes

(4,8) remains to be elucidated. KIT

gene mutations occur in ~80% of GISTs (8). Additionally, a higher occurrence of

primary imatinib resistance was observed in GISTs with KIT

exon 9 mutations, PDGFRα D842V mutations and wild-type

KIT and PDGFRα compared with other types of gene

mutation (9). Tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib have transformed therapeutic

approaches for advanced GISTs. Currently, four TKIs, imatinib,

sunitinib, regorafenib and ripretinib, are approved for use as

first-line, second-line, third-line and fourth-line therapies,

respectively (5,10). Ripretinib, a broad-spectrum

KIT and PDGFRα inhibitor, is approved for the

treatment of adult patients with LAGISTs who have received prior

treatment with three or more kinase inhibitors, including imatinib.

Furthermore, avapritinib, a type I kinase inhibitor, is approved

for the treatment of adults with unresectable or metastatic GISTs

harboring a PDGFRα exon 18 mutation, including PDGFRα

D842V mutation (11). The present

study specifically examined treatment outcomes for patients with

LAGISTs with several gene mutations following first-line therapy

with imatinib.

Materials and methods

Patient demographics

There are no clear criteria to define LAGIST at

present. In the present study, LAGIST that was initially diagnosed

was defined as being unsuitable for radical resection, risk of

substantial organ dysfunction or borderline unresectable according

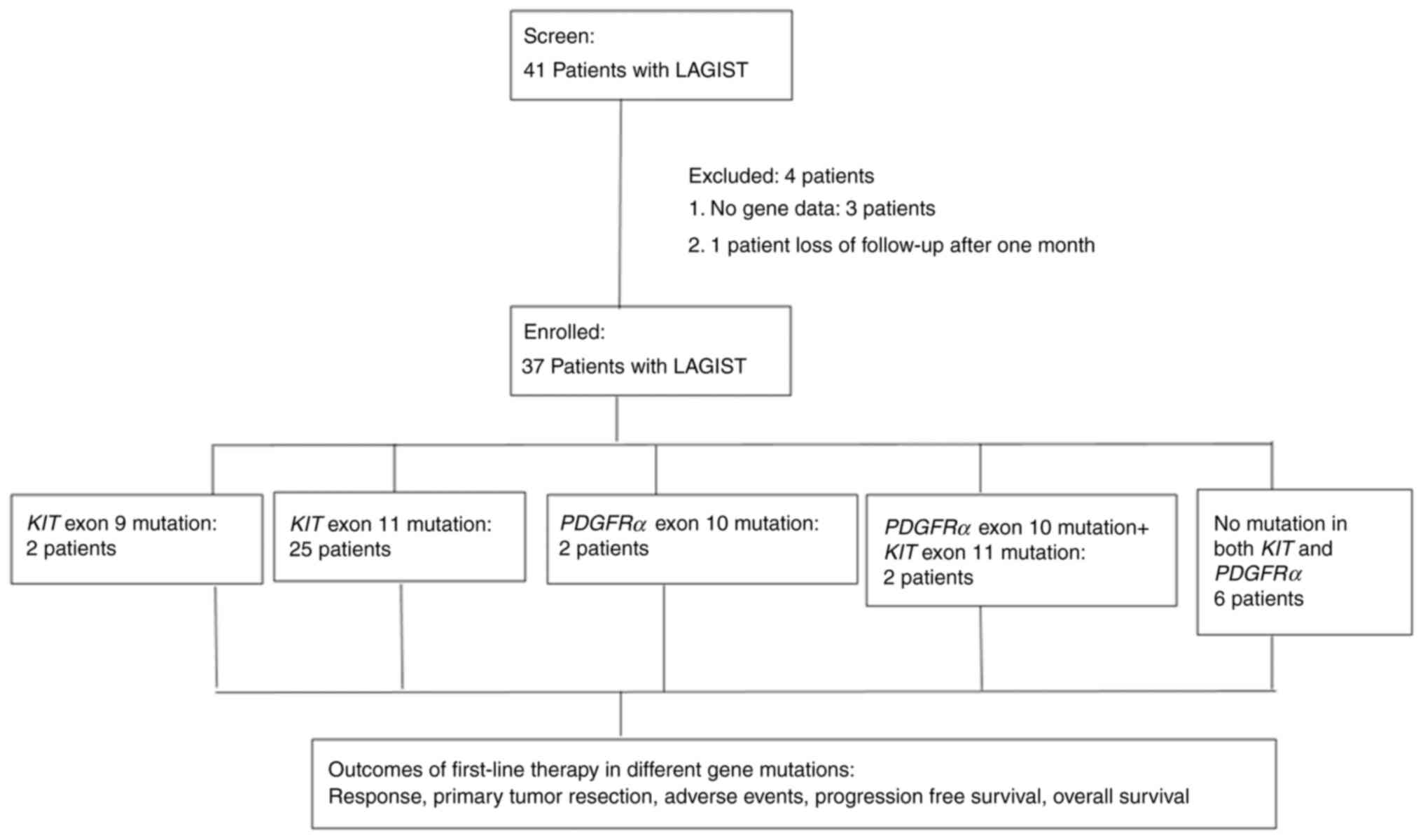

to a previous study by our group (3). Fig. 1

depicts a flowchart of the patient recruitment process. A total of

41 patients who had received a diagnosis of a LAGIST and who

underwent first-line treatment at a single institution (Kaohsiung

Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan) between December

2010 and July 2023 were included. A total of 3 of the 41 patients

were excluded for having no gene data and 1 patient was excluded

for being lost to follow-up after 1 month, leaving a total of 37

patients for final enrolment. Enrolled patients were closely

monitored until January 2024. The inclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Having an LAGIST that was initially diagnosed as

unsuitable for radical resection; and ii) being at risk of

substantial organ dysfunction or borderline unresectable (3,12–14).

Following the administration of first-line therapy with imatinib,

the included patients were followed for a median period of 41

months (range, 10 to 183 months). Tumor responses were assessed

through concurrent analysis of computed tomography (CT) images and

the genetic mutation profiles of KIT and PDGFRα

genes. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital [Kaohsiung, Taiwan;

approval no. KMUHIRB-E(I)-20240084] and the requirement for patient

consent was waived due to the respective nature of the study.

Treatment

Each patient received a prescription for imatinib at

a daily dose of 400 mg, with a treatment duration ranging from 3 to

56 months (median, 15 months). In cases where patients experienced

grade 3 or 4 toxicities, the imatinib dose was reduced to 300 mg

per day. Sunitinib was administered as a second-line therapy at a

daily dose of 37.5 mg when the first-line imatinib treatment failed

and disease progression was evident on CT scans performed every 3

months. Sunitinib was administered to improve the response after

consultation with a multidisciplinary team (MDT), which comprised

surgeons, radiologists, gastroenterologists and oncologists.

Regorafenib was employed as a third-line treatment at a daily dose

of 120 mg. After the radical resection, the adjuvant treatment was

continued for a total of 36 months under close supervision by the

MDT.

Evaluation of tumor response and

toxicities

Tumor dimensions and density were verified through

assessment of abdominal CT scans by two radiologists. Any

discrepancies were resolved through a joint re-examination of the

images by both radiologists. Tumor responses were assessed using CT

images in accordance with the response evaluation criteria in solid

tumors 1.1 (RECIST 1.1) (15).

Adverse events (AEs) were categorized based on the Common

Terminology Criteria for AEs, version 3.0 (16). In evaluating surgical resectability

in patients with LAGISTs, the timing followed the method of

combined CT-measured tumor density and RECIST 1.1 described in a

previous study by our group (3).

All enrolled patients were followed up by CT and laboratory data

every 3 months for efficacy evaluation until surgical intervention.

The decision to proceed with surgery was made using combined

CT-measured tumor density and RECIST for evaluating surgical

timing. With either a tumor size (tumor dimensions) reduction of

>30% or a reduction of >30% of tumor density, surgery was

considered (3). Surgical timing was

confirmed by the MDT, which comprised surgeons, radiologists,

gastroenterologists and oncologists. The clinical condition of the

patients (such as age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

performance status and willingness of the patient to undergo

surgery) was also considered.

KIT and PDGFRα gene mutations

CT-guided core biopsies were performed prior to the

initiation of the first-line imatinib therapy to collect tumor

tissue specimens. Biopsy specimens were carefully embedded in

paraffin, fixed using formalin and subsequently sectioned into

slices measuring 4 µm in thickness. DNA extraction was performed

using the Qiagen DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Inc.), following the

manufacturer's instructions. The concentration and quality of the

extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer. The optical density at either 260 or 280 nm for

DNA extracted from all patient specimens fell within the range of

1.8 to 2.0, indicating that the DNA samples were of suitable

quality for subsequent experiments. The DNA samples were subjected

to analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a PCR

instrument from Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Subsequently, the KIT or PDGFRα primers (at a

concentration of 100 µM) and the 2X PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) were introduced and mutations confirmed by Sanger

sequencing. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for

10 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C denaturation for 30 sec, 58°C

annealing for 45 sec and 72°C extension for 45 sec, followed by a

final step of 72°C for 7 min. The primers for the KIT gene

were as follows: Forward (exon 9), 5′-GATGCTCTGCTTCTGTACT-3′ and

reverse (exon 9), 5′-GCCTAAACATCCCCTTAAATTGG-3; forward (exon 11),

5′-CTCTCCAGAGTGCTCTAATGAC-3 and reverse (exon 11),

5′-AGCCCCTGTTTCATACTGACC-3′; forward (exon 13),

5′-CGGCCATGACTGTCGCTGTAA-3′ and reverse (exon 13),

5′-CTCCAATGGTGCAGGCTCCAA-3′; forward (exon 17),

5′-TCTCCTCCAACCTAATAGTG-3′ and reverse (exon 17),

5′-GGACTGTCAAGCAGAGAAT-3′; forward (exon 18),

5′-CATTTCAGCAACAGCAGCAT-3′ and reverse (exon 18),

5′-CAAGGAAGCAGGACACCAAT-3′. The primers for PDGFRα gene were

as follows: Forward (exon 10), 5′-GACTCTCAGGAATTGGCC-3′; reverse

(exon 10), 5′-CAGCTGATGAGTTGTCCTG-3′; forward (exon 12),

5′-GAACGTTGTTGGACTCTACTGTG-3′ and reverse (exon 12),

5′-GCAAGGGAAAAGGGAGTCT-3′; forward (exon 14),

5′-GTAGCTCAGCTGGACTGATA-3′ and reverse (exon 14):

5′-AATCCTCACTCCAGGTCAGT-3′; forward (exon 18),

5′-CTTGCAGGGGTGATGCTAT-3′ and reverse (exon 18),

5′-AGAAGCAACACCTGACTTTAGAGATTA-3′.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 21 (IBM Corp.). Progression-free survival (PFS) was

calculated from the treatment initiation date to the date of any

form of progression or the last recorded follow-up. Overall

survival (OS) was defined as the duration from the commencement of

treatment to either mortality from any cause or the last follow-up

date. PFS and OS were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and

the log-rank test was employed to compare time-to-event

distributions. Treatment response rates, resection rates and AE

rates were compared using Fisher's exact test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient series, tumor characteristics

and mutation status

The demographic and clinicopathological

characteristics of the enrolled patients are presented in Table I. The median age of the cohort was

65 years, with total ages ranging from 33 to 87 years. Among the

patients, 25 (67.6%) were men and 12 (32.4%) were women. The

LAGISTs were located in various sites: Stomach (21 patients;

56.8%), omentum (1 patient; 2.7%), pancreas (1 patient; 2.7%),

small intestine (5 patients; 13.5%), mesocolon (1 patient; 2.7%),

pelvic area (1 patient; 2.7%) and rectum (7 patients; 18.9%).

| Table I.Demographics of 37 patients with

locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor. |

Table I.

Demographics of 37 patients with

locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

| Characteristic | Patients, n

(%) |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 25 (67.6) |

|

Female | 12 (32.4) |

| Median age (years,

range) | 65 (33–87) |

| Tumor location |

|

|

Stomach | 21 (56.8) |

|

Omentum | 1 (2.7) |

|

Pancreas | 1 (2.7) |

| Small

intestine (including duodenum) | 5 (13.5) |

|

Mesocolon | 1 (2.7) |

| Pelvic

area | 1 (2.7) |

|

Rectum | 7 (18.9) |

| Type of gene

mutation |

|

|

KIT exon 9

insertion | 2 (5.4) |

|

KIT exon 11

insertion | 5 (13.5) |

|

KIT exon 11

deletion | 14 (37.8) |

|

KIT exon 11-point

mutation | 5 (13.5) |

|

KIT exon 11

duplication | 1 (2.7) |

|

PDGFRα exon 10-point

mutation | 2 (5.4) |

|

KIT exon 11 deletion;

PDGFRα exon | 2 (5.4) |

|

10-point mutation |

|

| No

mutation in both KIT and PDGFRα | 6 (16.2) |

| Mutation

numbers | 31 (83.8) |

|

KIT exon 9 | 2 (5.4) |

|

KIT exon 11 | 27 (73.0) |

|

PDGFRα exon 10 | 4 (10.8) |

Regarding genetic mutations, 29 patients (78.4%) had

KIT mutations and 4 (10.5%) had PDGFRα mutations. A

total of 2 patients (5.4%) had KIT exon 9 insertions, five

(13.5%) had KIT exon 11 insertions, 14 patients (37.8%) had

KIT exon 11 deletions, 5 (13.5%) had KIT exon 11

point mutations and 1 (2.7%) had KIT exon 11 duplications. A

total of 2 patients (5.4%) had PDGFRα exon 10 point

mutations and 2 patients (5.4%) had PDGFRα exon 10 point

mutations with a KIT exon 11 deletion. A total of 6 patients

(16.2%) had wild-type KIT and PDGFRα (Table I). Representative Sanger sequencing

images depicting each respective mutation are shown in Fig. S1, Fig.

S2, Fig. S3, Fig. S4, Fig.

S5, Fig. S6, Fig. S7.

Treatment outcomes

Analysis of tumor responses using the RECIST 1.1

revealed that 20 of the 37 patients (54.1%) achieved a partial

response (PR) and 15 (40.5%) exhibited stable disease (SD). After

therapy, 24 of the 37 patients (64.9%) with unresectable LAGISTs

underwent primary tumor R0 resection (Table II). The median duration of

first-line therapy was 16 months, with the total therapy duration

ranging from 3 to 56 months. A total of 21 of the 24 patients

eligible for resection were treated with imatinib; 3 patients

subsequently switched to second-line sunitinib to achieve an

improved response. However, the treatment response and surgical

resectability rates of the 37 patients with LAGISTs following

first-line therapy did not differ significantly in tumors with

varying mutations of the KIT and PDGFRα genes (both

P>0.05; Table II). As of the

final follow-up performed in January 2024, 21 of the patients were

still alive. Sunitinib was administered for 4–52 months (median, 9

months) and regorafenib was administered for 5 months (case no. 5)

and 24 months (case no. 21), up to the end of treatment or

follow-up (Table III). Of the 21

patients with stomach LAGIST, 10 (47.6%) patients achieved PR, 9

(42.9%) patients SD and 2 (9.5%) patients progressive disease. Of

the 5 patients with small intestine LAGIST, 3 (60%) patients

achieved PR and 2 (40%) patients achieved SD. Of the 7 patients

with rectal LAGIST, 6 (85.7%) patients achieved PR and 1 (14.3%)

patient achieved SD (Table III).

A total of 21 patients received adjuvant treatment with imatinib

after the operation and 3 patients had adjuvant treatment with

sunitinib (Table III). The

adjuvant regimen was the same as that previously used in the

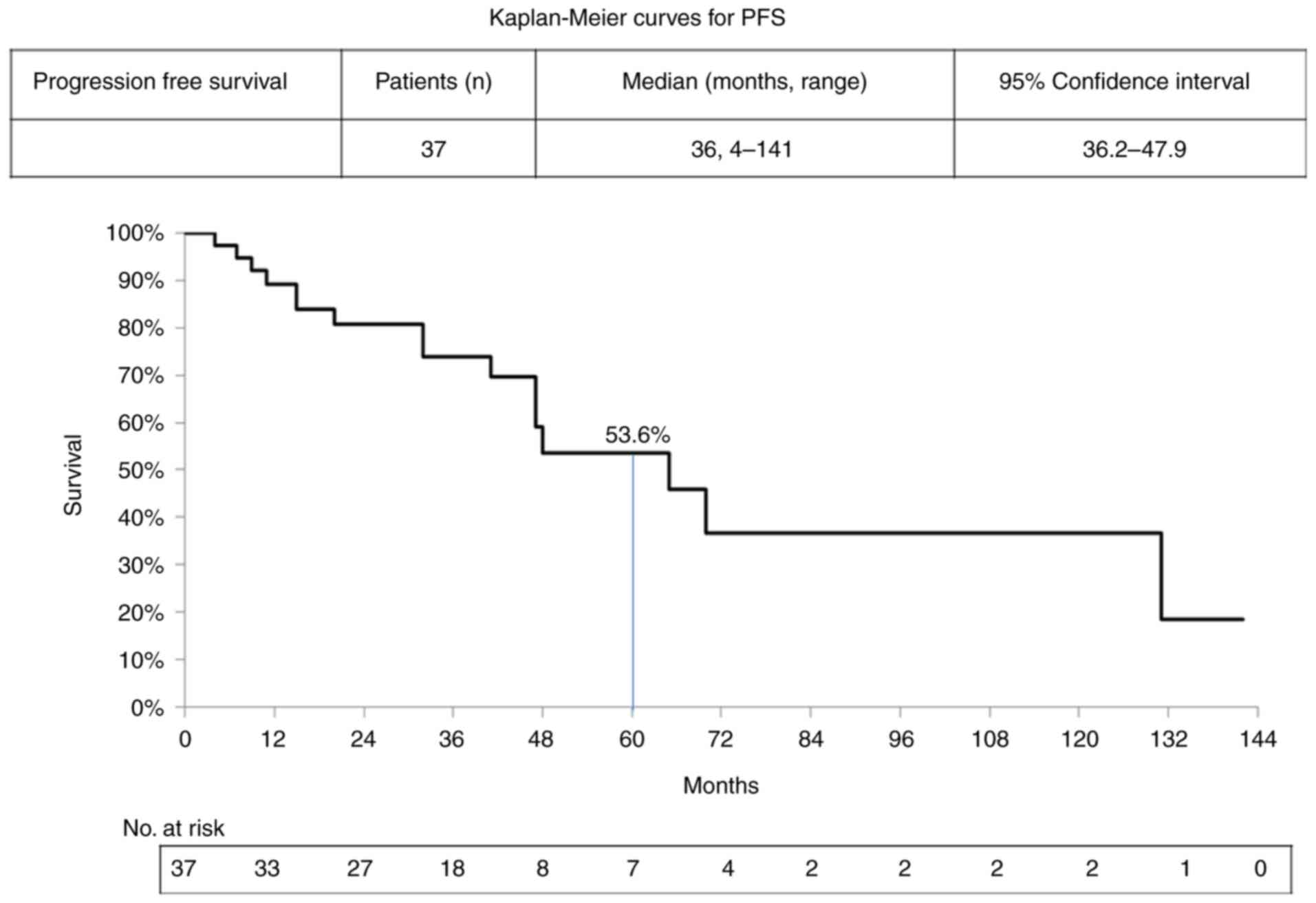

first-line setting or the second-line setting. The median PFS of

the 37 patients was 36 months, with the total PFS ranging from 4 to

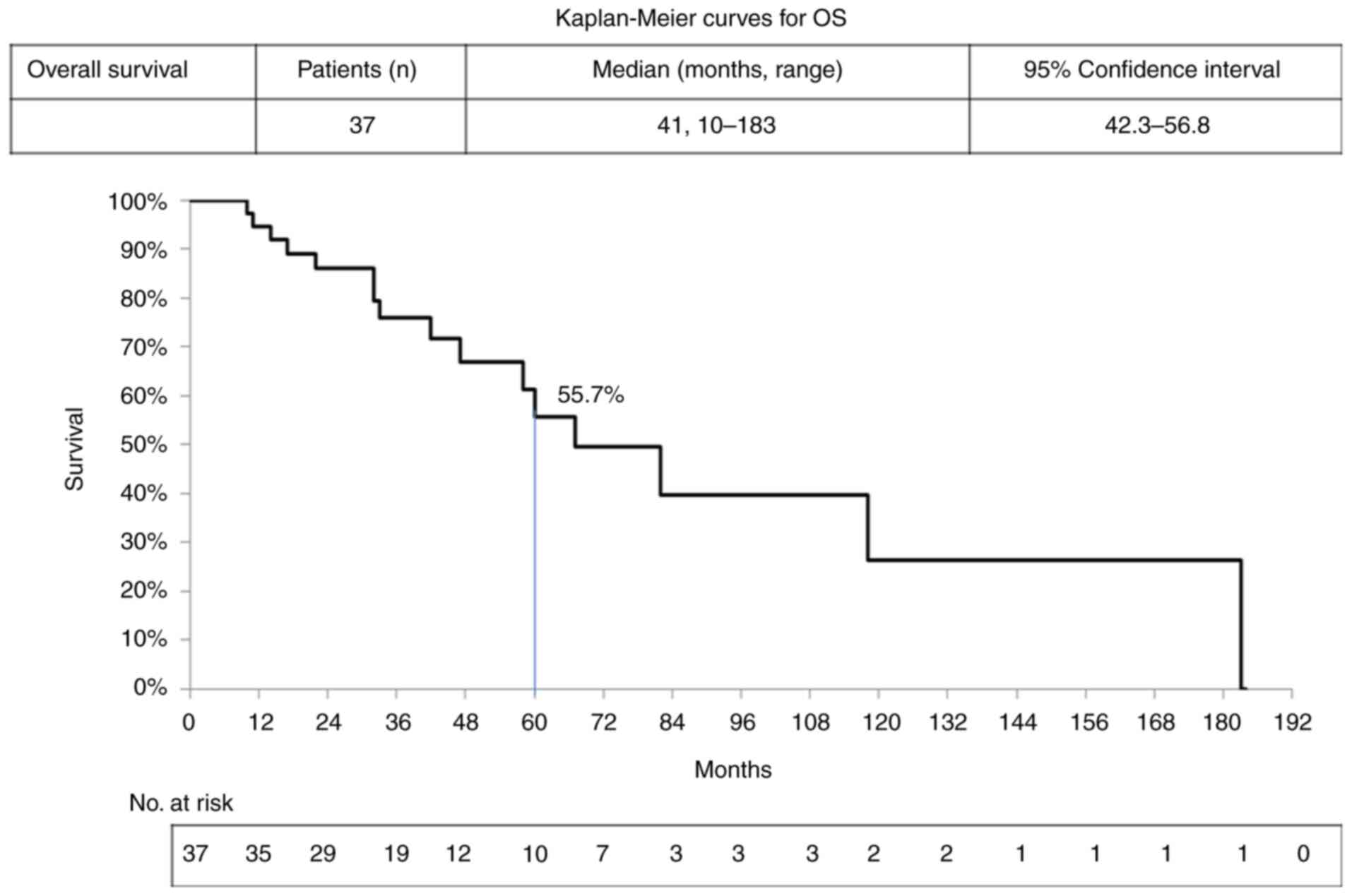

141 months and a 5-year (60 months) PFS rate of 53.6% (Fig. 2). The median OS of the patients was

41 months, with total OS ranging from 10 to 183 months and a 5-year

(60 months) OS rate of 55.7% (Fig.

3). AEs were reported by 78.4% of patients receiving first-line

imatinib therapy, with the most commonly reported AEs being eyelid

edema and nausea; these were experienced by 8 patients (21.6%).

Anemia was experienced by 5 patients (13.5%). In addition, 3

patients (8.1%) had grade 3 anemia (Table IV).

| Table II.Treatment outcome of first-line

therapy in different gene mutations of 37 patients with locally

advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor. |

Table II.

Treatment outcome of first-line

therapy in different gene mutations of 37 patients with locally

advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

| Mutation | Patients, n

(%) | Partial response, n

(%) | Stable disease, n

(%) | Progressive

disease, n (%) | Primary tumor

resection, n (%) | No primary tumor

resection, n (%) |

|---|

| KIT exon 9

insertion | 2 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) |

| KIT exon

11 | 25 (100.0) | 14 (56.0) | 10 (40.0) | 1 (4.0) | 17 (68.0) | 25 (100.0) |

|

Insertion | 5 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0 | 4 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) |

|

Deletion | 14 (56.0) | 9 (64.2) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (7.1) | 8 (57.1) | 14 (56.0) |

| Point

mutation | 5 (20.0) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 4 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) |

|

Duplication | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| PDGFRα exon

10 point mutation | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) |

| KIT exon 11

deletion; | 2 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) |

| PDGFRα exon

10 point mutation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No mutation in both

KIT and PDGFRα | 6 (100.0) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100.0) |

| Total | 37 (100.0) | 20 (54.1) | 15 (40.5) | 2 (5.4) | 24 (64.9) | 37 (100.0) |

| P-value |

|

| P=0.732 |

| P=0.977 |

| Table III.Pathologic and treatment evaluation

of 37 patients with locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal

tumor. |

Table III.

Pathologic and treatment evaluation

of 37 patients with locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal

tumor.

| A, Resvponders |

|---|

|

|---|

| Case no. | Sex | Age, years | Tumor location | Duration of

first-line imatinib therapy, months | PFS of first-line

imatinib therapy, months | Duration of

second-line therapy, months | PFS of second-line

therapy, months | Duration of

third-line therapy, months | PFS of third-line

therapy, months | OS, months | Gene analysis

result | Best overall

response/resection | Survival |

|---|

| 1 | M | 62 | Stomach | 8 | 32 | - | - | - | - | 32 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1648_1671del 24; p.K550_W557del) | PR/Yes | No |

| 2 | F | 83 | Stomach | 8 | 15 | - | - | - | - | 33 | Insertion in

KIT exon 11 (p.Y578_D579insPY) | PR/Yes | No |

| 3 | F | 74 | Stomach | 17 | 48 | - | - | - | - | 58 | Deletion in

KIT exon11 (c.1674_1676delGGT; p.K558_V559>N); point

mutation in exon 10 of PDGFRα (c.1432T>C) (p.S478P) | PR/No | Lost follow up |

| 4 | M | 74 | Stomach | 16 | 66 | - | - | - | - | 66 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1669_1674del; p.Trp557_Lys558del) | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 5 | M | 48 | Stomach | 41 | 41 | 14 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 70 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1669_1674del6; p.W557_K558del); point

mutation in PDGFRα exon 10 | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 6 | M | 67 | Stomach | 14 | 48 | - | - | - | - | 48 | Mutation was not

found in KIT exon 9,11,13,17,18; mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 7 | M | 54 | Stomach | 14 | 45 | - | - | - | - | 45 | Insertion in

KIT exon 11 (p.H580_581insYDH) | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 8 | M | 46 | Stomach | 11 | 25 | - | - | - | - | 25 | Mutation was not

found in KIT exon 9,11,13,17,18; mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 9 | F | 66 | Stomach | 21 | 22 | - | - | - | - | 22 | Point mutation in

KIT exon 11 (c.1676 T>A; p V559D) | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 10 | M | 78 | Stomach | 15 | 15 | - | - | - | - | 15 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1661_1675 del; p.E554_558del) | PR/No | Yes |

| 11 | M | 52 | Omentum | 15 | 141 | 4 | 126 | - | - | 141 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1671_1676del GAAGGT; p.W557_V559>C) | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 12 | M | 51 | Small

intestine | 16 | 59 | - | - | - | - | 73 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 13 | F | 57 | Duodenum | 11 | 41 | - | - | - | - | 41 | Deletion across

KIT intron 10 of exon 11 boundary | PR/Yes | Yes |

| 14 | M | 76 | Small

intestine | 29 | 31 | - | - | - | - | 31 | Insertion in

KIT gene exon 9 (p.S501_A502insAY) | PR/No | Yes |

| 15 | M | 50 | Rectum | 15 | 65 | - | - | - | - | 67 | Point mutation in

KIT exon 11 (c.1727T>C; p.L576P) | PR/Yes | No |

| 16 | M | 53 | Rectum | 20 | 20 | - | - | - | - | 22 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1669_1674del TGGAAG; p.W557_K558del) | PR/No | Lost follow up |

| 17 | M | 64 | Rectum | 15 | 15 | 22 | 22 | - | - | 60 | Mutation was not

found in KIT exon 9,11,13,17,18; mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | PR/Yes | Lost follow up |

| 18 | M | 81 | Rectum | 6 | 7 | - | - | - | - | 17 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1674_1676delGGT; p.K558_V559>N) | PR/No | No |

| 19 | M | 41 | Rectum | 18 | 27 | 9 | 9 | - | - | 27 | Point mutation in

KIT exon 11 (c.1674 G>T; p.K558N) and (c.1676T>C; V.

559) | PR/No | Yes |

| 20 | F | 73 | Rectum | 8 | 18 | - | - | - | - | 18 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1669_1674del; p.W557_K558del) | PR/Yes | Yes |

|

| B,

Non-responders |

|

| Case

no. | Sex | Age,

years | Tumor

location | Duration of

first-line imatinib therapy, months | PFS of

first-line imatinib therapy, months | Duration of

second-line therapy, months | PFS of

second-line therapy, months | Duration of

third-line therapy, months | PFS of

third-line therapy, months | OS,

months | Gene analysis

result | Best overall

response/resection |

Survival |

|

| 21 | F | 60 | Stomach | 13 | 47 | 5 | 6 | 24 | 26 | 118 | Point mutation in

KIT exon 11 (c.1669T>A; p.W557R) | SD/Yes | No |

| 22 | M | 70 | Stomach | 9 | 32 | - | - | - | - | 32 | Point mutation in

KIT exon 11 (c.1679_1680TT>AG; p.V560E) | SD/Yes | Lost follow up |

| 23 | M | 80 | Stomach | 36 | 47 | - | - | - | - | 47 | Duplication

mutation at 12bp in KIT exon11 | SD/Yes | Lost follow up |

| 24 | F | 38 | Stomach | 41 | 70 | 8 | 10 | - | - | 82 | Deletion in exon 11

of KIT gene (delK550_Q556insM) | SD/No | No |

| 25 | F | 72 | Stomach | 11 | 48 | - | - | - | - | 48 | Insertion in

KIT exon 11 (p.K558dup); mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | SD/Yes | Yes |

| 26 | M | 65 | Stomach | 19 | 36 | - | - | - | - | 36 | Mutation was not

found in KIT exon 9,11,13,17,18; mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | SD/Yes | Yes |

| 27 | F | 33 | Stomach | 16 | 43 | - | - | - | - | 43 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1674_1676 del; p.K558_V559 delinsN) | SD/Yes | Yes |

| 28 | M | 44 | Stomach | 10 | 19 | - | - | - | - | 19 | Point mutation in

PDGFRα exon 10 (c.1436G>A; p.R479Q) | SD/Yes | Yes |

| 29 | M | 87 | Stomach | 3 | 11 | - | - | - | - | 11 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1735_1737 del; p.D579del) | SD/Yes | Lost follow up |

| 30 | M | 72 | Stomach | 9 | 9 | 4 | 4 | - | - | 14 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11 (c.1671_1676del GAAGGT; p.W557_V559>C) | PD/No | Lost follow up |

| 31 | F | 35 | Stomach | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | - | - | 10 | Mutation was not

found in KIT exon 9,11,13,17,18; mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | PD/No | Lost follow up |

| 32 | F | 70 | Pancreas | 11 | 83 | - | - | - | - | 83 | Insertion in

KIT exon 11 of KIT gene (p.K558>NP) | SD/Yes | Yes |

| 33 | F | 41 | Duodenum | 29 | 29 | - | - | - | - | 29 | Mutation was not

found in KIT exon 9,11,13,17,18; mutation was not found in

PDGFRα exon 10,12,14,18 | SD/No | Yes |

| 34 | M | 67 | Duodenum | 36 | 36 | - | - | - | - | 36 | Insertion in

KIT exon 11 (p.P573_T574insDP) | SD/No | Yes |

| 35 | M | 74 | Mesocolon | 56 | 131 | 52 | 52 | - | - | 183 | Point mutation in

exon 10 of PDGFRα gene (c.1432T>C; p.S478P) | SD/No | No |

| 36 | M | 67 | Pelvic area | 21 | 41 | 12 | 12 | - | - | 42 | Deletion in

KIT exon 11(delK558_V559insN) | SD/No | Lost follow up |

| 37 | M | 58 | Rectum | 29 | 77 | 17 | 48 | - | - | 77 | Insertion in

KIT exon 9 (p.S501_A502insAT) | SD/Yes | Yes |

| Table IV.Adverse events of first-line therapy

in different gene mutations in 37 patients with locally advanced

gastrointestinal stromal tumor. |

Table IV.

Adverse events of first-line therapy

in different gene mutations in 37 patients with locally advanced

gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

| Adverse events | KIT exon 9

insertion (n=2), n (%) | KIT exon 11

insertion (n=5), n (%) | KIT exon 11

deletion (n=14), n (%) | KIT exon 11

point mutation (n=5), n (%) | KIT exon 11

duplication (n=1), n (%) | PDGFRα exon

10 point mutation (n=2), n (%) | KIT exon 11

deletion; PDGFRα exon 10 point mutation (n=2), n (%) | No mutation in both

KIT and PDGFRα (n=6), n (%) |

|---|

| All grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nausea | - | 2 (40.0) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (20.0) | - | - | - | 1 (16.7) |

|

Vomiting | - | - | 2 (14.3) | 1 (20.0) | - | - | - | 1 (16.7) |

|

Gastritis | - | - | 1 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | - | - | - | - |

|

Edema | 1 (50.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (40.0) | - | - | - | - |

| Eyelid

edema | 1 (50.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | - | 1 (50.0) | - | 2 (33.3) |

| General

malaise | - | 1 (20.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Skin

rash | - | 2 (40.0) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | - | - | - | - |

|

Diarrhea | - | - | - | 1 (20.0) | - | 1 (50.0) | - | - |

|

Fatigue | - | - | 1 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) | - | - | - | - |

| Renal

function impairment | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (16.7) |

| Liver

function impairment | - | - | 1 (7.1) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Hand-foot skin reaction | 1 (50.0) | - | 1 (7.1) | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Anemia | - | - | 3 (21.4) | - | - | 1 (50.0) | - | 1 (16.7) |

|

Leukopenia | - | - | 1 (7.1) | - | - | - | - | 1 (16.7) |

| P-value | P=0.967 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Grade ≥3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anemia | - | - | 2 (14.3) | - | - | - | - | 1 (16.7) |

Discussion

Curative resection is generally recommended for

patients with GISTs, but such resection is not considered for

patients with LAGISTs due to factors such as tumor location, size

and increased risk of tumor rupture or metastasis (2–5). The

present study reported on the experience of treating 37 patients

with LAGIST at a single institution and the outcomes of first-line

therapy in relation to various gene mutations. Although a higher

proportion of men (67.6%) participated in the present study

compared with other studies (55.0–66.7%), the median age (65 years)

of the participants was consistent with that of those in other

studies (57.4–63 years) (2,8,12).

The stomach was the most commonly affected region in

the present study, consistent with findings reported in at least

one other study (6). Most patients

exhibited favorable clinical responses to first-line imatinib

therapy; 20 (54.1%) experienced PR, 15 (40.5%) maintained SD and 2

(5.4%) exhibited disease progression. The data were consistent with

the findings of other studies that demonstrated a 45–92% response

rate (17–24), although studies have indicated a

marked increase in primary resistance to imatinib, particularly in

GISTs with PDGFRα mutations and those with mutations in exon

9 of the KIT gene (9,25).

However, the mutation status of the KIT and PDGFRα

genes was not helpful in predicting treatment response (P=0.602) or

surgical resectability (P=0.952). Due to the relatively small

patient number for each genetic mutation, it would not have been

suitable from the perspective of statistics to create Kaplan-Meier

plots or waterfall plots by grouping the patients by gene. The most

common AEs of all grades were nausea, vomiting, gastritis, edema,

eye lid edema, general malaise, skin rash, diarrhea, fatigue, renal

function impairment, liver function impairment, hand-foot skin

reaction, anemia and leukopenia and that of grade ≥3 was anemia

(Table IV). No significant

differences were observed in the AEs experienced during first-line

therapy by patients whose tumors exhibited any mutations;

comparisons were made among KIT exon 9 insertion, KIT

exon 11 insertion, KIT exon 11 deletion, KIT exon 11

point mutation, KIT exon 11 duplication, PDGFRα exon

10 point mutation, KIT exon 11 deletion, PDGFRα exon

10 point mutation and no mutation in both KIT and

PDGFRα (Table IV). The AEs

noted in the present study were generally mild, well-tolerated and

manageable with no marked hematologic toxicity at standard dosages

in patients treated with first-line imatinib therapy in another

multicenter cohort study (26). In

the present study, 24 (64.9%) patients with initially unresectable

LAGISTs underwent primary tumor resection. In addition, 21 patients

who received treatment with first-line imatinib and 3 who achieved

PR following treatment with first-line imatinib but then SD

switched to second-line sunitinib, which achieved a superior

response. Second-line sunitinib treatment was effective for these

patients with LAGISTs, increasing the likelihood of achieving

complete resection and minimizing the risk of tumor spillage. The

present study demonstrated that omental LAGIST had the best

response rate (100%) when compared with rectal LAGIST (85.7%),

small intestinal LAGIST (60%) and gastric LAGIST (47.6%),

indicating omental and rectal LAGIST show a better response to

imatinib compared with other organs. In addition, the responders

group had a higher resection rate (70%) compared with the

non-responders group (58.8%).

Overall, the median PFS was 36 months, longer than

the 18–20 months reported in a previous study (20). Additionally, at the conclusion of

follow-up, 21 patients (56.8%) were still alive. The different

response rate and survival outcomes may arise from the different

definitions of LAGIST, different gene mutation patterns, different

tumor sites, different ethnicity and different treatment doses. For

instance, a previous study enrolled 746 patients with a median PFS

of 18 months in the standard-dose arm and 20 months for those

receiving high-dose imatinib (20).

Although the ideal length of imatinib therapy

remains debatable, imatinib should be administered in clinical

settings until a maximal response is achieved. According to the

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, achieving a

maximal response may require treatment for >6 months (27). A previous study that evaluated

treatment responses discovered that a maximal response is typically

achieved after ~12 months of treatment (26). In the 24 patients in the present

study who subsequently underwent resection, the median time to

primary tumor resection was 16 months. Determining the ideal

duration of first-line treatment should involve regular response

assessments to determine the optimal timing for surgical

intervention (22,26–28).

Combined CT-measured tumor density and RECIST evaluations may aid

in determining an appropriate timing for LAGIST surgical resection

(3).

Clinical research suggests the benefits of imatinib

therapy in patients with GISTs. If it is technically resectable,

neoadjuvant therapy can preserve organ function, avoid tumor

rupture, reduce postoperative complications and increase the R0

resection rate to up to 91% compared with 85% (29). For unresectable GISTs, the response

rate of first-line imatinib therapy is 45–69% (30). A previous study revealed that 15.7%

of patients with initially unresectable GIST became resectable

under first-line imatinib therapy (31). In the present study, the patients

were all initially unresectable and imatinib was used as the

first-line therapy instead of neoadjuvant therapy.

A higher occurrence of primary imatinib resistance

was observed in GISTs with KIT exon 9 mutations, GISTs with

PDGFRα D842V mutations and GISTs with wild-type KIT

and PDGFRα. Hence, evaluation is needed of the potential

differences in treatment responses based on different mutation

types in a prospective, multicenter clinical trial. The present

study has certain limitations. First, a retrospective design was

employed with a non-randomized controlled trial and a relatively

small sample size from a single institution for the mutation

association analysis. Therefore, the findings require verification

in a prospective, multicenter clinical trial required to associate

gene mutations with other TKIs. Second, the present study lacked

comprehensive information on the GIST-associated gene mutation

status of the patients, which may influence the risk of recurrence

and survival outcomes for GISTs. Third, the relatively brief

follow-up duration may have resulted in an underestimation of the

effects of first-line imatinib therapy on PFS and OS. A total of 1

patient progressed fast (first-line failure, 4 months; second-line,

5 months) and was lost to follow-up after 10 months (case no. 31),

and at the time of the study's conclusion, 5 patients are still

under treatment, 21 patients are still alive and 9 patients have a

short follow-up time of <24 months. In spite of the limitations

of the present study, it is evident that first-line imatinib

therapy is effective and safe in reducing tumor size in patients

with LAGISTs, yielding comparable rates of complete resection.

In conclusion, the gene mutation status was

demonstrated to have limited value as an indicator for assessing

treatment response and surgical resectability. Additionally, no

significant variations were observed in complication rates.

Although most patients clinically benefited from first-line

imatinib therapy with manageable side effects, future studies with

long-term follow-ups are required to verify the results.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by grants from the National

Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (grant nos. MOST

111-2314-B-037-070-MY3, NSTC 112-2314-B-037-050-MY3, NSTC

113-2321-B-037-006 and NSTC 113-2314-B-037-057) and Taiwan's

Ministry of Health and Welfare (grant no.

MOHW113-TDU-B-222-134014). Additional funding was provided from

Taiwan's National Health and Welfare Surcharge on Tobacco Products,

by Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (grant nos. KMUH111-2M29,

KMUH112-2R37, KMUH112-2R38, KMUH112-2R39, KMUH112-2M27,

KMUH112-2M28, KMUH112-2M29, KMUH-S11303 and KMUH-SH11309) and by a

Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center Grant (grant no.

KMU-TC113A04). The present study was also supported by a grant from

the Taiwan Precision Medicine Initiative and by the Taiwan Biobank

of Academia Sinica.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WCS and JYW were involved in the conception and

design of this study. WCS wrote the manuscript. WCS, CWH, HLT, YCC

and TKC performed data acquisition. WCS, PJC, YSY and TCY

contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. JYW

reviewed and edited the manuscript and supervised the study. WCS

and JYW confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study fully complied with the

Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital [approval no.

KMUHIRB-E(I)-20240084]. According to regulations at our

institution, patient consent was waived for the present study due

to its retrospective nature.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hirota S: Differential diagnosis of

gastrointestinal stromal tumor by histopathology and

immunohistochemistry. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 3:272018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Coffey RJ, Washington MK, Corless CL and

Heinrich MC: Ménétrier disease and gastrointestinal stromal tumors:

Hyperproliferative disorders of the stomach. J Clin Invest.

117:70–80. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Su WC, Tsai HL, Yeh YS, Huang CW, Ma CJ,

Chen CY, Chang TK and Wang JY: Combined computed

tomography-measured tumor density and RECIST for evaluating

neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal

tumors. Transl Cancer Res. 7:634–644. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rodrigues J, Campanati RG, Nolasco F,

Bernardes AM, Sanches SRA and Savassi-Rocha PR: Pre-operative

gastric gist downsizing: The importance of neoadjuvant therapy. Arq

Bras Cir Dig. 32:e14272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

von Mehren M and Joensuu H:

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 36:136–143. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu Z, Zhang Z, Sun J, Li J, Zeng Z, Ma M,

Ye X, Feng F and Kang W: Comparison of prognosis between

neoadjuvant imatinib and upfront surgery for GIST: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 13:9664862022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Casali PG, Jost L, Reichardt P, Schlemmer

M and Blay JY: Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO clinical

recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

20 (Suppl):S64–S67. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang D, Zhang Q, Blanke CD, Demetri GD,

Heinrich MC, Watson JC, Hoffman JP, Okuno S, Kane JM, von Mehren M

and Eisenberg BL: Phase II trial of neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib

mesylate for advanced primary and metastatic/recurrent operable

gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Long-term follow-up results of

radiation therapy oncology group 0132. Ann Surg Oncol.

19:1074–1080. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Joensuu H: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

(GIST). Ann Oncol. 17 (Suppl 10):x280–x286. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Patel SR and Reichardt P: An updated

review of the treatment landscape for advanced gastrointestinal

stromal tumors. Cancer. 127:2187–2195. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bauer S, George S, von Mehren M and

Heinrich MC: Early and next-generation KIT/PDGFRA kinase inhibitors

and the future of treatment for advanced gastrointestinal stromal

tumor. Front Oncol. 11:6725002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ding P, Wu J, Wu H, Sun C, Guo H, Lowe S,

Yang P, Tian Y, Liu Y, Meng L and Zhao Q: Inflammation and

nutritional status indicators as prognostic indicators for patients

with locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with

neoadjuvant imatinib. BMC Gastroenterol. 23:232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang J, Yin Y, Shen C, Yin X, Cai Z, Pu L,

Fu W, Wang Y and Zhang B: Preoperative imatinib treatment in

patients with locally advanced and metastatic/recurrent

gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A single-center analysis. Medicine

(Baltimore). 99:e192752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Vassos N, Jakob J, Kähler G, Reichardt P,

Marx A, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Rathmann N, Wardelmann E and

Hohenberger P: Preservation of organ function in locally advanced

non-metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) of the

stomach by neoadjuvant imatinib therapy. Cancers (Basel).

13:5862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA,

Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van

Oosterom AT, Christian MC and Gwyther SG: New guidelines to

evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European

organization for research and treatment of cancer, national cancer

institute of the United States, national cancer institute of

Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:205–216. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tsai HL, Shi HY, Chen YC, Huang CW, Su WC,

Chang TK, Li CC, Chen PJ, Yeh YS, Yin TC and Wang JY: Clinical and

cost-effectiveness analysis of mFOLOFX6 with or without a targeted

drug among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Inverse

probability of treatment weighting. Am J Cancer Res. 13:4039–4056.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hsiao HH, Liu YC, Tsai HJ, Chen LT, Lee

CP, Chuan CH, Wang JY, Yang SF, Tseng YT and Lin SF: Imatinib

mesylate therapy in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors:

Experience from a single institute. Kaohsiung J Med Sci.

22:599–603. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

van Oosterom AT, Judson I, Verweij J,

Stroobants S, Donato di Paola E, Dimitrijevic S, Martens M, Webb A,

Sciot R, Van Glabbeke M, et al: Safety and efficacy of imatinib

(STI571) in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours: A phase I

study. Lancet. 358:1421–1423. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, Van

den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, Heinrich MC, Tuveson DA,

Singer S, Janicek M, et al: Efficacy and safety of imatinib

mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med.

347:472–480. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW,

von Mehren M, Benjamin RS, Raymond AK, Bramwell VH, Baker LH, Maki

RG, et al: Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing

imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable

or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit

receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 26:626–632. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Seshadri RA and Rajendranath R:

Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal

tumors. J Cancer Res Ther. 5:267–271. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

van der Burg SJC, van de Wal D, Roets E,

Steeghs N, van Sandick JW, Kerst M, van Coevorden F, Hartemink KJ,

Veenhof XAAFA, Koenen AM, et al: Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally

advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) is effective and

safe: Results from a prospective single-center study with 108

Patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 30:8660–8668. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lam TJR, Udonwa SA, Masuda Y, Yeo MHX,

Farid Bin Harunal Ras M and Goh BKP: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of neoadjuvant imatinib use in locally advanced and

metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Surg.

48:1681–1691. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Khosroyani HM, Klug LR and Heinrich MC:

TKI treatment sequencing in advanced gastrointestinal stromal

tumors. Drugs. 83:55–73. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW and Kim YS:

Correlation of imatinib resistance with the mutational status of

KIT and PDGFRA genes in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A

meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 22:413–418.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li W, Li X, Yu K, Xiao B, Peng J, Zhang R,

Zhang L, Wang K, Pan Z, Li C and Wu X: Efficacy and safety of

neoadjuvant imatinib therapy for patients with locally advanced

rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A multi-center cohort

study. Front Pharmacol. 13:9501012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS,

Boles S, Bui MM, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane

JM, et al: Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

16:536–563. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang SY, Wu CE, Lai CC, Chen JS, Tsai CY,

Cheng CT, Yeh TS and Yeh CN: Prospective evaluation of neoadjuvant

imatinib use in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors:

Emphasis on the optimal duration of neoadjuvant imatinib use,

safety, and oncological outcome. Cancers (Basel). 11:4242019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Iwatsuki M, Harada K, Iwagami S, Eto K,

Ishimoto T, Baba Y, Yoshida N, Ajani JA and Baba H: Neoadjuvant and

adjuvant therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann

Gastroenterol Surg. 3:43–49. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mohammadi M, NS IJ, Hollander DD, Bleckman

RF, Oosten AW, Desar IME, Reyners AKL, Steeghs N and Gelderblom H:

Improved efficacy of first-line imatinib in advanced

gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): The Dutch gist registry

data. Target Oncol. 18:415–423. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Medrano Guzman R, Lopez Lara X, Arias

Rivera AS, Garcia Rios LE and Brener Chaoul M: Neoadjuvant imatinib

in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): The first analysis of a

Mexican population. Cureus. 16:e650012024.PubMed/NCBI

|