Introduction

Chordoma is a rare primary malignant bone tumor that

originates from the embryonic remnants of the notochord. Chordoma

typically arises in the skull base or sacrum, with an annual

incidence rate of ~0.8 cases per million individuals, accounting

for ~1% of all bone tumors (1).

Chordomas can manifest at any age, but the majority of patients are

diagnosed between the ages of 40 and 50 years. Clinical

manifestations primarily depend on the location and extent of the

lesions, with intracranial chordomas often causing headaches or

facial numbness due to their proximity to cranial nerves, while

sacrococcygeal chordomas may lead to lumbosacral pain or bowel

dysfunction due to compression of the sacral nerve roots (1).

Chordoid meningioma, on the other hand, is a rare

subtype of meningioma, accounting for 0.5–1% of all meningiomas

(2). This tumor is more commonly

found in young female patients and is typically located in the

supratentorial region or at the skull base (3). Chordoid meningiomas can invade

surrounding tissues, leading to symptoms such as headaches,

vomiting and visual disturbances (2,3).

Given the overlapping clinical and pathological

features of chordoma and chordoid meningioma, accurate

differentiation between these two entities is crucial for

appropriate treatment and prognosis. Misdiagnosis can lead to

inappropriate therapeutic strategies, potentially affecting patient

outcomes (4). The present case

report aims to highlight the challenges in differentiating between

chordoma and chordoid meningioma, emphasizing the importance of

immunohistochemical markers and imaging studies in achieving an

accurate diagnosis.

Case report

In March 2022, a 59-year-old male patient presented

to the Qingdao Municipal Hospital (Qingdao, China) with a 2-month

headache, dizziness and numbness in the right hand. The symptoms

intensified when the patient lowered their head and rolled their

neck. Notably, the severity of these symptoms had increased over

the past month. The physical examination revealed normal limb

movements, gait and consciousness, as well as clear speech. The

bilateral pupils were equal in size and shape, and exhibited a

light reaction, and the patient displayed symmetrical forehead

lines and nasolabial grooves on both sides. Tongue extension was

centered. Muscle strength in the limbs was rated at level 5, muscle

tone was normal (5) and blood

pressure readings were within the normal range. The patient had no

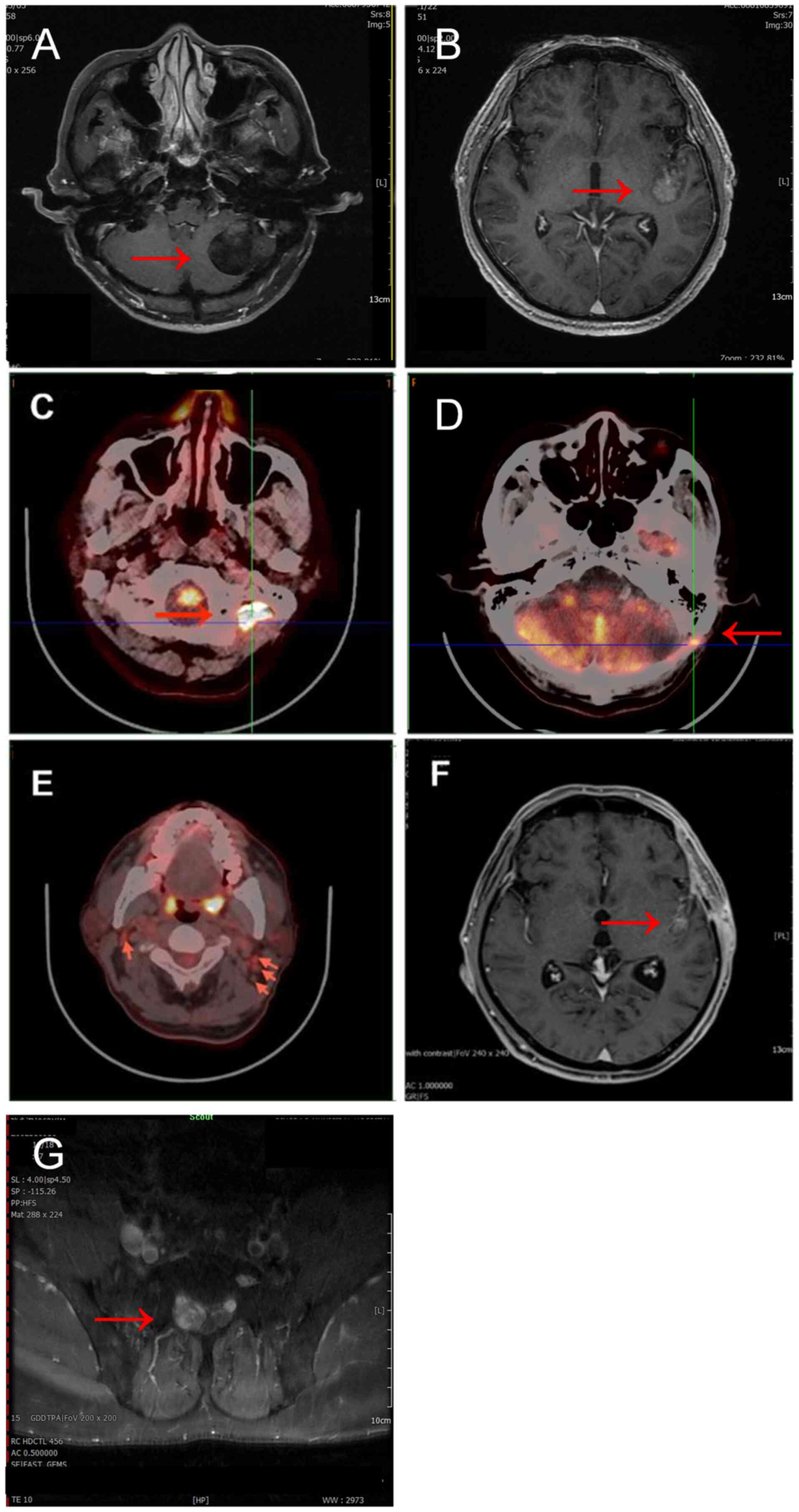

abnormal results in routine laboratory tests. Magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) revealed a round lesion in the left cerebellar

hemisphere, characterized by long T1 and long T2 signals, with

T2-weighted-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery exhibiting high

signal intensity and unevenness. The lesion measured ~39 mm in

diameter, had clear boundaries and was located adjacent to the

lateral margin of the cerebellum, with diffusion-weighted imaging

(DWI) showing an iso-low signal. MRI enhancement demonstrated

moderate, uneven enhancement of the left cerebellar hemisphere

lesion, featuring a central non-enhanced area and mild enhancement

of the surrounding wall. The MRI findings were indicative of a

‘space-occupying lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere’

(Fig. 1A). There was no prior

history of tumors. The patient underwent an intracranial tumor

resection in March 2022. Following the procedure, the vital signs

and overall condition of the patient were stable. Subsequently, the

planning target volume (PTV) for radiotherapy following the first

operation was 5,040 cGy/180 cGy/28 fractions, and mannitol

injection (20%) in a volume of 150 ml once was provided to reduce

intracranial pressure.

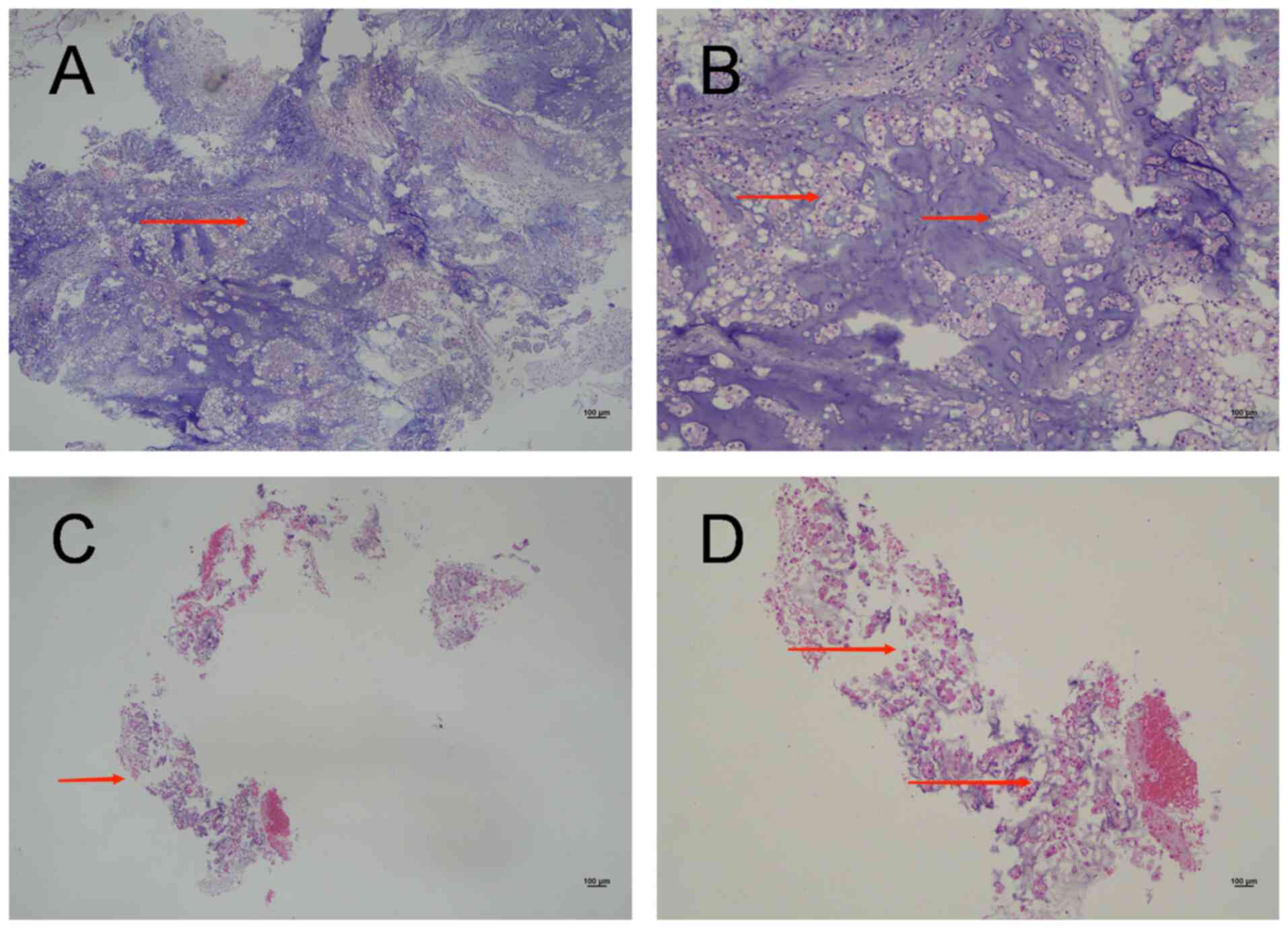

The gross resected specimen was formed of

grey-white-brown broken tissue, with a total size of 2.5×2×2 cm,

and the local tissue section was soft and spongy. Postoperative

pathology (Data S1) revealed that

the tumor was composed of cords of epithelioid cells with

vacuolated cytoplasm and collagen fibers within a basophilic stroma

(Fig. 2A and B).

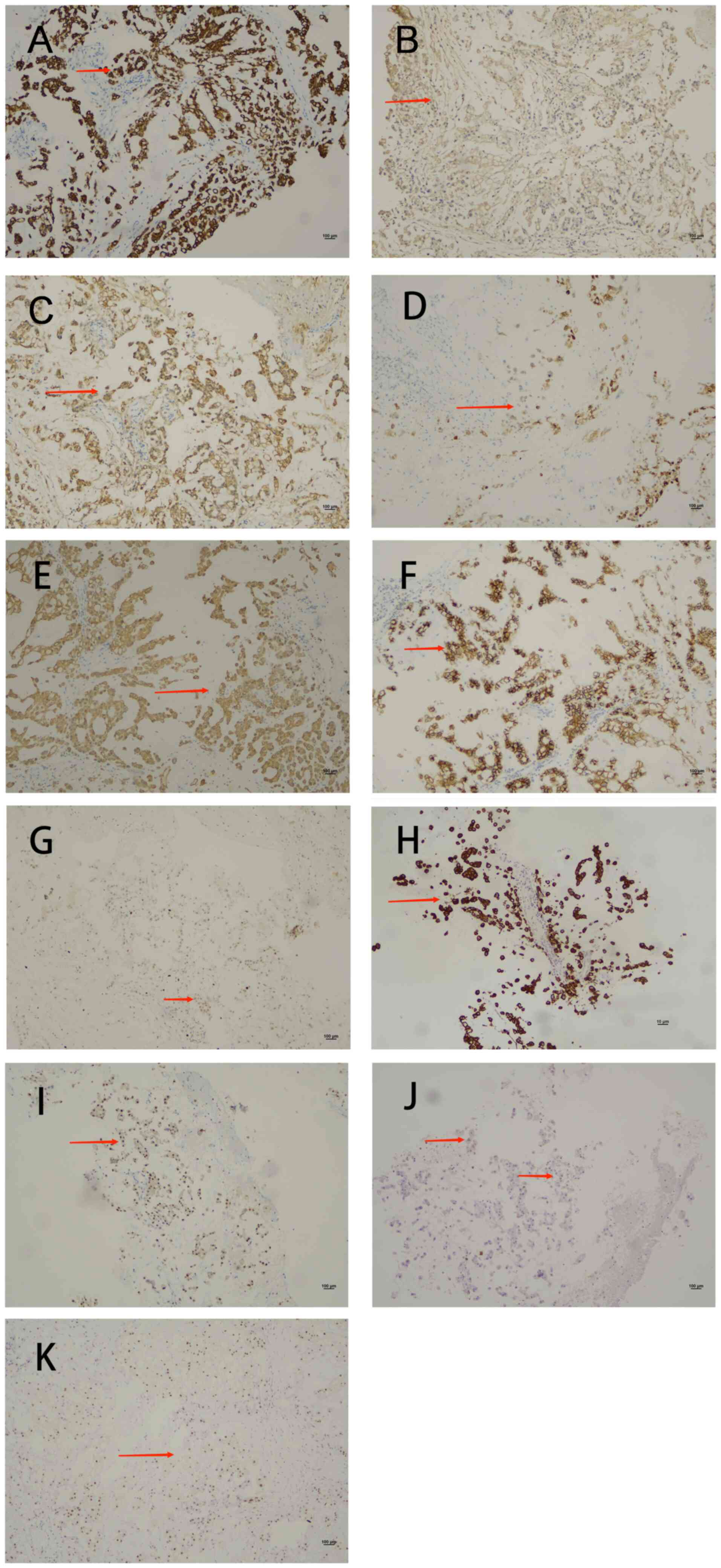

Immunohistochemical analysis (Data

S1) revealed positivity for cytokeratin (CK), cytokeratin 8/18

(CK8/18), vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA),

synaptophysin and E-cadherin, with a Ki-67 proliferation index of

3% (Fig. 3A-G). The tumor was

negative for S100, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP),

progesterone receptor (PR), D2-40 and SOX-10 (data not shown).

Based on the pathological and immunohistochemical findings, a

diagnosis of chordoma-like meningioma [World Health Organization

(WHO) Grade 2] (6) was made.

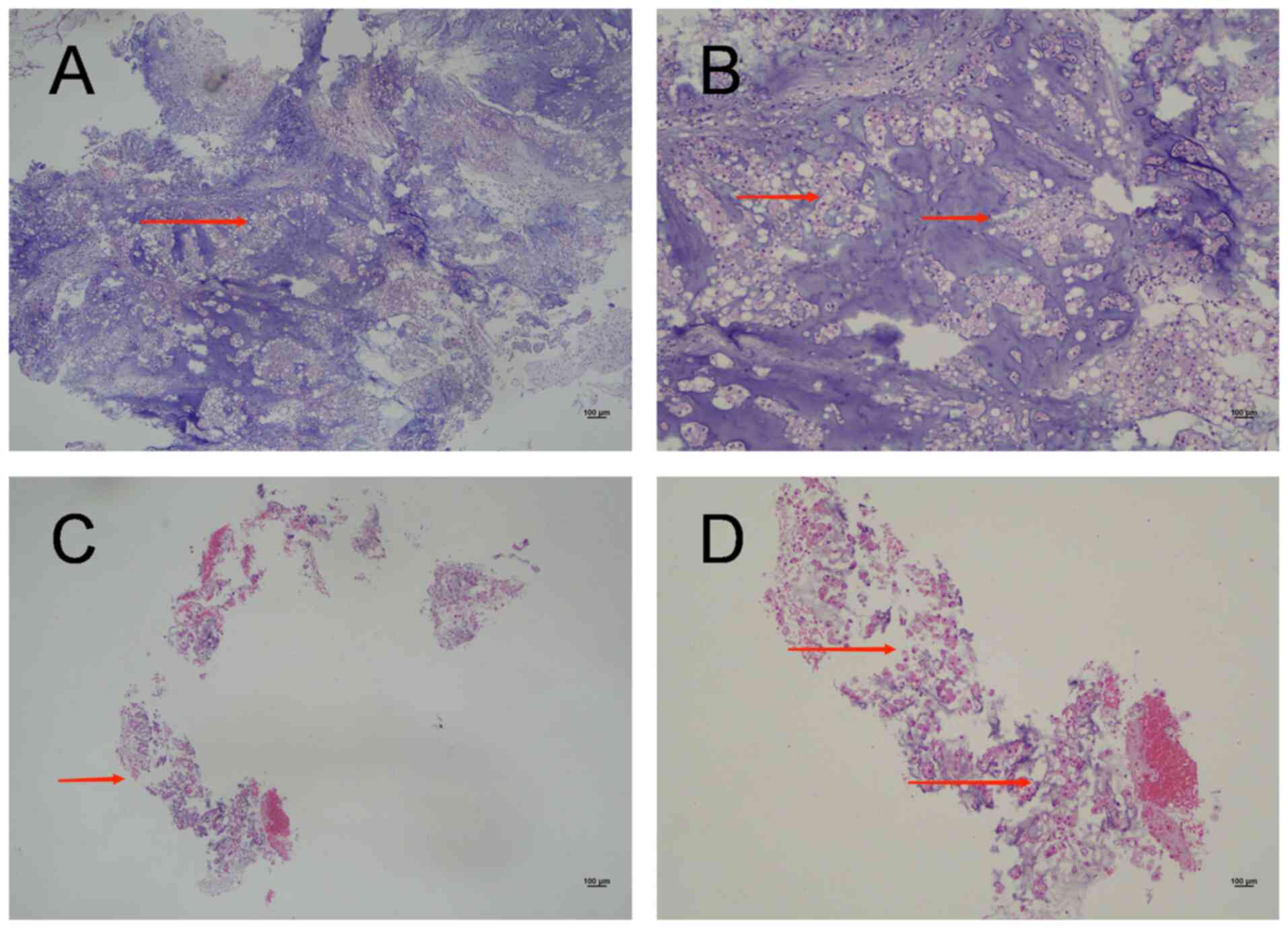

| Figure 2.H&E images of two tumors. (A) An

H&E image from 2022. Magnification, ×4. Under low

magnification, the tissue appears fragmented, with the tumor

exhibiting a pattern of cords and nests within the blue myxoid

matrix (arrow). (B) An H&E image from 2022. Magnification, ×10.

Under medium magnification, the tumor is composed of cords of

epithelioid cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and collagen fibers

within a basophilic stroma (arrows). (C) An H&E image from

2023. Magnification, ×4. Under low magnification, the tissue

appears fragmented and is accompanied by a small amount of

blue-stained mucus (arrow). (D) A 2023 H&E image.

Magnification, ×10. Under medium magnification, the tumor is

composed of cords and isolated epithelioid cells, which exhibit

intracytoplasmic vacuoles within a myxoid matrix (arrows). H&E,

haematoxylin and eosin. |

In November 2023, the patient experienced numbness

on the right side of the face, without accompanying symptoms of

headaches or dizziness. Neurological examination revealed no

abnormalities. An MRI revealed irregular mass enhancement in the

left Sylvian fissure cistern, with a cross-sectional area of ~22×18

mm, suggestive of an intracranial occupying lesion (Fig. 1B). In November 2023, the patient

underwent another intracranial tumor resection. Postoperatively,

the condition of the patient remained stable. The patient received

radiotherapy for intracranial lesions and the lumbosacral area in

December 2023. The PTV for radiotherapy after the second operation

was 4,000 cGy/200 cGy/20 fractions for the intracranial lesion and

7,000 cGy/200 cGy/35 fractions for the lumbosacral lesion. At 1

month after the completion of radiotherapy, the efficacy evaluation

indicated a partial response.

The gross specimen of the second surgery consisted

of grey and broken tissue, with a diameter of 0.3 cm. The pathology

results revealed that the tumor was composed of cords and isolated

epithelioid cells, which exhibited intracytoplasmic vacuoles within

a myxoid matrix (Fig. 2C and D).

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive CK (Fig. 3H), Brachyury (Fig. 3I) and weakly-positive S100 (Fig. 3J) expression. These

immunohistochemical findings suggested a diagnosis of chordoma.

A review of the hematoxylin and eosin slices from

the first surgery in 2022 indicated that the epithelioid cells were

arranged in a cord-like distribution within an eosinophilic

mucinous matrix. Some cells exhibited eosinophilic cytoplasm, while

others appeared vacuolated. Classic meningioma structures were

absent, and there was no evidence of lymphocyte or plasma cell

infiltration at the tumor periphery in a layered pattern. Repeat

immunohistochemistry confirmed that the original slices were

Brachyury-positive (Fig. 3K),

further supporting the diagnosis of chordoma.

Postoperative follow-up in March 2024 revealed a

patchy, low-density area in the left cerebellar surgical site,

measuring ~24.7×19.4 mm. Additionally, soft-tissue nodules on the

periphery and below, with a cross-section of ~25.6×15.0 mm,

fluorodeoxyglucose hypermetabolic lesions in the peripheral and

inferior regions of the left cerebellar surgical site and multiple

hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the bilateral neck were noted on

positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) (Fig. 1C-E). Given the possibility of tumor

recurrence and metastasis, palliative radiotherapy at 6,000 cGy/200

cGy/30 fractions was administered to the affected area. The

efficacy evaluation indicated progressive disease 1 month after the

completion of radiotherapy. In September 2024, the patient came to

the hospital for re-examination due to dizziness and constipation.

MR enhanced scanning examination showed the formation of softening

lesions in the left cerebellar hemisphere and abnormal enhancement

in the left insular-Sylvian cistern area (Fig. 1F). Follow-ups were organized and the

patient was advised to return if symptoms worsened.

In November 2024, the patient presented to the

hospital with paroxysmal headaches and dizziness. An enhanced MRI

of the lumbosacral spine revealed nodular abnormal signal foci in

the sacral canal at the S1-2 level, indicating a chordoma (Fig. 1G). Due to the progression of the

disease in the brain, cranial radiotherapy was deemed

inappropriate. Although the patient was advised to undergo

comprehensive genetic testing, followed by targeted therapy and

immunotherapy, the patient declined all these recommendations. The

patient received a low dose of imatinib mesylate tablets (0.4 g,

once daily) as targeted therapy, which resulted in slight

alleviation of the dizziness (Table

I). The patient sought treatment in Beijing following this

visit and did not return to the hospital for a follow-up until

February 2025, with the primary complaint still being dizziness.

The clinician prescribed imatinib mesylate tablets (0.4 g, once

daily) as a treatment.

| Table I.Summary table of patient

presentation. |

Table I.

Summary table of patient

presentation.

| Date | Patient

presentation |

|---|

| March, 2022 | The patient

presented to the hospital with complaints of headaches and

dizziness. MRI revealed a space-occupying lesion in the left

cerebellar hemisphere. A resection of the skull base lesion was

subsequently performed. The pathological diagnosis was chordoid

meningioma. Postoperative radiotherapy was then administered. |

| November, 2023 | The patient

presented to the hospital with facial numbness on the right side.

MRI revealed an intracranial space-occupying lesion. The patient

subsequently underwent resection of the skull base lesion, and the

pathological diagnosis was chordoma. |

| December, 2023 | The patient

underwent local radiotherapy for intracranial lesions and the

sacral vertebra following surgery, with the treatment's efficacy

assessed as a partial response. |

| March, 2024 | Positron emission

tomography-computed tomography scans revealed a space-occupying

lesion in the left cerebellar surgical site. Given the potential

for tumor recurrence, palliative radiotherapy was administered to

the area of recurrence, and the efficacy of this treatment was

evaluated as progressive disease. |

| November, 2024 | The patient

experienced episodes of paroxysmal dizziness, and MRI enhancement

revealed nodular abnormal signal foci within the sacral canal. The

possibility of chordoma recurrence was considered, and targeted

therapy with imatinib was administered. |

Discussion

Chordoma is a rare primary malignant bone tumor that

originates from the embryonic remnants of the notochord. During

embryonic development, the upper end of the notochord is situated

in the sphenoid and occipital bones at the base of the skull, while

the lower end is located in the sacrum. Consequently, chordomas

typically arise in the skull base or sacrum. The annual incidence

rate of chordoma is ~0.8 per million individuals, accounting for

~1% of all bone tumors. Chordoma can manifest at any age; however,

the majority of patients are diagnosed between the ages of 40 and

50 years, with <5% of cases occurring in individuals <20

years (1,7).

Clinical manifestations primarily depend on the

location and extent of the lesions. Intracranial chordomas

typically result in headaches or facial numbness due to the

proximity of the tumor to cranial nerves, whereas sacrococcygeal

chordomas lead to lumbosacral pain or bowel dysfunction as a

consequence of compression of the sacral nerve roots (7).

Meningioma is a type of tumor that arises from the

meninges, the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal

cord. Chordoid meningiomas account for 0.5–1% of all meningiomas

and are more commonly found in young female patients (8). These tumors are typically located in

the supratentorial region or at the skull base, where they invade

surrounding tissues, leading to associated symptoms such as

headaches, vomiting and visual disturbances (3).

The clinical symptoms of chordoma and chordoid

meningioma can often present similarly. The current patient

presented at the hospital with complaints of dizziness, headaches

and numbness in the right hand. There were no distinguishing

symptoms to differentiate between the two tumors. While chordoma is

known for its propensity to recur, meningioma typically does not

exhibit this tendency. The recurrence of the tumor within <2

years aligns with the biological behavior of chordoma, prompting

re-evaluation and revision of the initial pathology report.

Chordoma commonly originates from the

sphenoid-occipital symphysis region and primarily grows in the

midline area, typically involving the midline structures in the

slope region. There is marked bone destruction at the skull base,

particularly in areas such as the saddle dorsal and slope, and the

tumor can extend into the adjacent basal cistern. Chordoma

typically presents as a destructive lobulated mass on CT, which

invades adjacent tissues and is associated with lytic bone

destruction and soft-tissue expansion (9). MRI, with its high soft-tissue

resolution, accurately depicts the location of the tumor, tissue

structure and surrounding structures that it invades. T1-weighted

imaging (T1WI) indicates low signal lesions, while T2-weighted

imaging (T2WI) shows high signal lesions accompanied by low signal

septations, resulting in a honeycomb-like pattern of uneven

enhancement (9–11).

Chordoid meningioma in general is located in the

supratentorial region and typically exhibits aggressive behavior on

imaging, often invading surrounding bone while maintaining an

intact capsule. Involvement of the brain parenchyma is rare

(3). A CT scan typically reveals

isodensity, while MRI often shows low signal using T1WI and high

signal using T2WI. Some lesions may exhibit mixed signals with long

T1 and long T2 characteristics, along with marked enhancement

following contrast administration (11). Caudal meningeal signs may be

present, and restricted diffusion on DWI is not limited (12).

The lesion in the present case was located adjacent

to the skull base area of the posterior cranial fossa; however,

there was no evident bone destruction in the adjacent skull, nor

were there any signs of bleeding, necrosis, irregular calcification

or other abnormalities within the lesion itself. The DWI signal of

the lesion was not elevated, indicating that it was not prominently

visible on imaging. There was no clear evidence of restricted

diffusion, which suggests that the imaging findings did not align

with typical clinical presentations of chordomas. The lesion in the

present case presented as a hemicystic, low-density round mass on

the plain CT scan. MRI signal characteristics revealed that T1WI

predominantly exhibited low signal intensity, while T2WI

demonstrated slightly elevated and uneven signal intensity, with

additional patches of slightly low signal observed internally. The

T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery image displayed

heterogeneous high signal intensity. Notably, most lesions on the

enhanced scan did not exhibit enhancement, although an eccentric

marginal area of pronounced heterogeneous enhancement was evident.

These imaging characteristics are not consistent with typical

clinical presentations of meningiomas. Therefore, this discrepancy

contributed to the misdiagnosis.

The initial diagnosed lesion in the present case was

situated in the left cerebellar hemisphere. The location of its

onset is not a typical site for meningiomas in adults. Furthermore,

the lesion did not exhibit the general characteristics associated

with intracranial and extracerebral tumors on imaging. These

characteristics include, but are not limited to, the white matter

collapse sign, the meningeal tail sign, adjacent subarachnoid space

widening and cerebrospinal fluid clefts (12). Additionally, the remaining lesions

did not show a close relationship with the dura mater or the

skull.

According to the 5th edition of the WHO

classification of bone and soft-tissue tumors, chordoma is

categorized into three types: Classic type, dedifferentiated type

and poorly differentiated type (7).

The pathology of classic chordoma is characterized by a fine

fibrovascular connective tissue stroma, which contains trabecular

and nest-like epithelioid cells within the lobules. The cell sizes

vary, and the cells include multinucleated, stellate and vacuolated

cells with abundant and intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm. The

background features an abundant extracellular myxoid matrix, and

necrosis is often observed, while mitotic figures are uncommon.

Classic chordoma may exhibit both chordoma and chondroid features,

previously referred to as chondroid chordoma; the 5th edition of

the WHO classification of bone and soft tissue tumors includes

chondroid chordoma under classic chordoma (4).

Dedifferentiated chordoma is a biphasic tumor

characterized by the presence of two distinct components: A classic

chordoma component and a high-grade sarcoma component. The

high-grade sarcoma component usually manifests as either high-grade

undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma or high-grade osteosarcoma.

Tumor cells may display binucleation or multinucleation, and

mitotic figures are often observable (4). The 5th edition of the WHO

classification of bone and soft-tissue tumors categorizes poorly

differentiated chordoma as a new subtype. This subtype has a low

incidence rate, primarily occurring in children and young adults,

and is commonly located at the skull base. Pathological features

include a solid growth pattern and notable cellular atypia, which

is characterized by the loss of integrase interactor 1 (INI1)

expression (4).

The pathology of chordoid meningioma is

characterized by tumor cells arranged in nests or trabecular

patterns, featuring eosinophilic cytoplasm and intracellular

vacuoles. The stroma has a myxoid appearance, and mitotic figures

are rare. Classic areas of meningioma are frequently observed in

the surrounding tissue, displaying a swirling, bundle-like pattern,

while pure chord meningioma is uncommon (13).

When the chordoid areas predominate or when tumors

exhibit chondroid metaplasia, accurate morphological diagnosis can

be problematic as the differential diagnosis broadens to include

chordoid glioma, skeletal/extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas,

chondrosarcomas and enchondromas. The immunohistochemical

evaluation is particularly effective for differentiating these

tumors (13) (Table II).

| Table II.Pathological distinctions of tumors

of the central nervous system with marked histological overlap. |

Table II.

Pathological distinctions of tumors

of the central nervous system with marked histological overlap.

| Tumor | Site | Tumor

structure | Tumor cells | Tumor stroma | Positive

immunohistochemistry results | Genetics | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Chordoma | Skull base or

sacrum | Lobulated

structure | The cell sizes

vary, and the cells include multinucleated, stellate and vacuolated

cells with abundant and intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm | Extracellular

myxoid matrix | CK8, CK18, CK19,

EMA, S100, Brachyury | Mutations in

Brachyury, CDKN2A, PTEN, SMARCB1 | (16,36) |

| Chordoid

meningiomas | Supratentorial

region or at the skull base | Tumor cells

arranged in cords or nests | The tumor cells

arranged in nests or trabecular patterns, featuring eosinophilic

cytoplasm and intracellular vacuoles | Myxoid matrix | Vimentin, EMA,

PR | Deletion of 1p,

2q/NF2 and CDKN2A/B | (2,8) |

| Chordoid

glioma | Third

ventricle | Lobulated

structure, with tumor cells arranged in clusters and cords | The tumor cell

displays characteristics of epithelial cells, including abundant,

deeply stained cytoplasm and oval or round nuclei | Myxoid or

vacuolated matrix | GFAP, TTF-1 | p.D463H mutation in

the PRKCA gene | (37,38) |

|

Skeletal/extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcomas | Deep soft tissues

of the proximal limbs, particularly in the lower limbs | Lobulated

structure, with tumor cells arranged in cords, small clusters or

grids | The nuclei of the

tumor cells are small and exhibit deep staining, while the

cytoplasm is eosinophilic and partially vacuolated | Myxoid or

myxochondral matrix | Vimentin, S100,

EMA, CD99, SOX9 | >75% of cases

contain the t(9;22)(q22-31;q11-12) chromosome translocation. The

NR4A3 fusion gene can be detected in >90% of cases | (39,40) |

|

Chondrosarcomas | Pelvis and proximal

femur | Lobulated

structure | Tumor cells are

dense at the edges of the lobules and sparse in the center. Tumor

cells are observed to be round, triangular or star-shaped and are

located within cartilage cavity | Cartilage

matrix | S100, SOX-10 | ~50% of the tumors

presented heterozygous missense mutations in IDH1 R132 and IDH2

R172 | (41,42) |

| Enchondroma | Metaphyseal region

of the long bones | Lobulated hyaline

cartilage nodules | The nuclei of tumor

cells are small, round and darkly stained, while the cytoplasm is

abundant in vacuoles | Cartilage

matrix | Lacks specific

immunohistochemical features | Mutations in the

IDH1/2 genes | (42) |

Chordomas and chordoid meningiomas exhibit marked

histological similarities. In the present study, the pathology

report from the first surgery revealed cord-like epithelioid cells,

myxoid stroma and meningioma-like regions in certain adjacent

areas. However, due to the limited number of gross specimens

available, there were insufficient regions for accurate

identification, leading to a misdiagnosis.

Chordoma expresses CK8, CK18 and CK19, but does not

express CK7 and CK20. Both EMA and S100 protein are positive in

chordomas (14,15). Brachyury, a transcription factor

encoded by the T gene located on chromosome 6q27, serves a crucial

role in embryonic notochord development and is considered a key

driver of chordoma (16). When

utilized for the diagnosis of chordoma, Brachyury demonstrates high

specificity and sensitivity, with a positive rate reaching as high

as 99%. In poorly differentiated chordoma, tumor cells are positive

for broad-spectrum CK and Brachyury, whereas in dedifferentiated

chordoma, expression of all markers may be negative (17,18).

Chordoid meningioma typically exhibits positivity for vimentin, EMA

and PR, while S100, CK and GFAP are generally negative. Sangoi

et al (13) reported a

higher positive rate of D2-40 in chordoid meningioma, highlighting

its diagnostic importance.

Chordoma and chordoid meningioma share numerous

immunohistochemical similarities. Brachyury, an antibody that has

received focus in recent years, is infrequently utilized for

diagnoses other than chordoma. Therefore, numerous pathologists may

not fully recognize its importance. This lack of awareness is also

the reason why Brachyury was not included in the initial pathology

assessment for the present patient.

In addition to Brachyury, mutations in genes such as

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), PTEN and INI1 have

also been identified in chordoma (19–21).

INI1 is a tumor suppressor protein that serves as a component of

the SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex, which

regulates gene expression through the remodeling of chromatin

structure. Deletion or mutation of the INI1 gene results in

decreased protein expression, thereby impairing the normal function

of the SWI/SNF complex. This impairment may subsequently lead to

abnormal cell proliferation and tumor formation (22). A recent study demonstrated that the

immunohistochemical loss of INI1 protein in poorly differentiated

chordoma primarily results from a homozygous deletion of the 22q11

locus (4). The loss of INI1 protein

may provide a rationale for assessing the efficacy of novel

targeted therapies, such as enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2)

inhibitors. EZH2 serves as the catalytic subunit of the histone

methyltransferase polycomb repressive complex 2, and its

upregulation has been linked to the promotion of carcinogenesis.

EZH2 inhibitors have demonstrated the ability to induce tumor

regression and enhance radiosensitivity in SWI/SNF-related BAF

chromatin remodeling complex subunit B1/INI1-deficient tumor models

(23). INI1 immunohistochemistry

was performed on the two surgical specimens of the patient, both of

which demonstrated weak positivity in a few scattered cells (data

not shown). Horbinski et al (24) reported that deletions of 1p36 and 9p

in chordoma were linked to decreased overall survival (OS).

Furthermore, Wei et al (25)

demonstrated that reduced H3K27me3 epigenetic modification in

chordoma was associated with a poor prognosis. H3K27me3 is a main

epigenetic modification, primarily mediated by EZH2, the catalytic

subunit of the histone methyltransferase PRC2 complex. H3K27me3 is

essential for the regulation of gene expression and is frequently

associated with gene silencing (26).

A previous study identified microRNA (miR)-1, miR-31

and miR-148a as promising prognostic and therapeutic markers for

chordoma (27). Additionally,

Brachyury vaccines and molecular targeted therapies have been

explored as potential treatment options for this condition

(28). The preferred treatment

method for chordoma is surgical intervention; however, the

proximity of vascular and nerve structures to the tumor often

hinders complete resection, resulting in a high risk of recurrence.

Chordomas exhibit a poor response to conventional radiotherapy and

chemotherapy, which renders these modalities ineffective as

standard treatment options (29). A

study involving 357 patients with chordoma performed in the United

States revealed OS rates of 80.5, 68.4 and 39.2% at 3, 5 and 10

years, respectively. Additionally, the disease-specific survival

rates at these intervals were 89.0, 80.9 and 60.1%, respectively.

It was observed that when patients were >60 years old or

received non-surgical treatment due to metastasis, the OS rate

declined (30).

Daoud et al (31) identified that common copy number

variations in chordoid meningioma included a deletion of 1p,

whereas deletions of 22q/NF2, moesin-ezrin-radixin-like tumor

suppressor and CDKN2A/B were molecular alterations associated with

tumor recurrence and progression. In the present study, the patient

refused to undergo molecular testing, and the small size of the

tumor tissue rendered pathological testing unfeasible. It is

essential for physicians to collect additional specimens during

surgery for molecular testing, thereby offering patients a broader

range of treatment options.

The preferred treatment for chordoid meningioma is

surgical intervention, and the grade of meningioma resection, as

categorized by the Simpson grading system, serves as a prognostic

factor. For patients in whom a Simpson grade II resection cannot be

achieved, postoperative radiotherapy is necessary (32). Ren et al (33) indicated that the progression-free

survival (PFS) of patients with chordoid meningioma was improved

compared with that of patients with non-chordoid WHO Grade 2

meningioma, yet worse than that of patients with WHO Grade 1

meningioma. Additionally, the OS of chordoid meningioma was

superior to that of non-chordoid WHO Grade 2 meningioma.

Furthermore, recurrence status and adjuvant radiotherapy were

identified as independent prognostic factors for both PFS and OS

(33).

Although the misdiagnosis did not affect the

surgical method in the present study, it influenced the treatment

approach and prognosis. If the initial diagnosis had been accurate

and radiotherapy for chordoma had been administered promptly, the

prognosis of the patient would likely have been more favorable than

it currently is. The lesion was situated in the cerebellum, and the

primary approach was resection of the skull base lesion. The

planning target volume (PTV) for radiotherapy following the first

operation was 5,040 cGy/180 cGy/28 fractions, while the PTV for

radiotherapy after the second operation was 4,000 cGy/200 cGy/20

fractions for intracranial lesion, 7,000 cGy/200 cGy/35 fractions

for lumbosacral. If chordoma was confirmed during the first

operation, an appropriate radiotherapy could have been utilized to

decrease the recurrence rate.

Pathology was the primary reason for the

misdiagnosis and subsequent mistreatment of the present patient.

Initially, the workflow of the pathology was flawed; the report was

issued by a single pathologist without review by a specialist or

general discussion. Due to a lack of experience in diagnosing

chordoma in the brain, the pathologist mistakenly classified the

chord-like cells as chordoid meningiomas, overlooking the potential

diagnosis of chordoma. Consequently, immunohistochemical staining

for vimentin, EMA, GFAP and S100, along with a negative result for

CD34, supported the erroneous conclusion of chordoid meningioma.

Unaware of the distinctions between chordoma and chordoid

meningioma, the pathologist did not perform the Brachyury test.

Furthermore, no imaging studies were performed to assess the

positional relationship between the tumor and the meninges.

Following recurrence, the original pathologist reviewed the initial

pathology and, upon consultation with a specialist, raised the

possibility of chordoma and recommended the Brachyury test for

confirmation. The positive result validated the diagnosis of

chordoma and highlighted the initial misdiagnosis. Rekhi and

Karmarkar (34) demonstrated that

immunohistochemistry is crucial for differentiating between these

two entities, recommending the use of CK, GFAP, vimentin, EMA,

S100, PR, D2-40 and Brachyury. Therefore, caution is advised when

certain immunohistochemical markers are absent, and it is prudent

to seek consultation from a more experienced pathologist if

necessary.

From a clinical perspective, the current patient

presented with a lack of specific clinical symptoms, and the site

of onset was not typical for a chordoma. Consequently, after

receiving a pathological diagnosis of meningioma, the clinician did

not engage in further communication with the pathologist.

In terms of imaging, the two preoperative MR

diagnoses indicated only intracranial space occupation without

specifying the tumor type or the potential for benign or malignant

characteristics. Following the second recurrence of the tumor and

subsequent pathological diagnosis, PET-CT revealed multiple

metastases throughout the body and suggested a diagnosis of

chordoma. The misdiagnosis prompted the development of a novel

pathology process: All reports must now be diagnosed by two

pathologists. Additionally, in challenging cases, it is essential

to communicate with imaging specialists and clinicians, and to

conduct a multidisciplinary team meeting when necessary. Brachyury

has been incorporated into the meningioma immunohistochemistry

panel to aid in the differentiation between meningiomas and

chordomas.

There are limitations to the present case report.

Molecular/genetic testing was not performed in the current case

report and limited tissue was available for diagnosis. While double

staining for S100 and Brachyury could assist in identifying similar

cases, both antibodies used in Qingdao Municipal Hospital stain the

nucleus. Currently, technology does not allow for the double

staining of antibodies that both target the nucleus. Consequently,

this method was not employed to further verify the diagnosis.

To the best of our knowledge, the current case

represents the first reported instance of such a misdiagnosis.

Previous discussions have predominantly concentrated on the

pathological differentiation between chordoma and chordoid glioma,

with only one reported case of a chordoid meningioma being

misdiagnosed as a chordoma (35).

Therefore, the present case serves to enhance the understanding of

chordoma and chordoid meningioma, ultimately improving diagnostic

accuracy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DL analyzed and interpreted the patient data, and

contributed to writing the manuscript. CJ and MMZ performed the

pathological examination. DL, MMZ and CJ confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. TW made substantial contributions to the

acquisition and interpretation of all imaging data (MRI, PET-CT),

critical analysis of radiological-pathological data and revision of

the manuscript for important intellectual content regarding imaging

findings. PZ provided analysis of clinical data. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed patient consent was obtained. The

present study was conducted with the approval of the Independent

Ethics Committee of the Qingdao Municipal Hospital.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of the present case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

MRI

|

magnetic resonance imaging

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

References

|

1

|

Karpathiou G, Dumollard JM, Dridi M, Dal

Col P, Barral FG, Boutonnat J and Peoc'h M: Chordomas: A review

with emphasis on their pathophysiology, pathology, molecular

biology, and genetics. Pathol Res Pract. 216:1530892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Couce ME, Aker FV and Scheithauer BW:

Chordoid meningioma: A clinicopathologic study of 42 cases. Am J

Surg Pathol. 24:899–905. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nambiar A, Pillai A, Parmar C and Panikar

D: Intraventricular chordoid meningioma in a child: Fever of

unknown origin, clinical course, and response to treatment. J

Neurosurg Pediatr. 10:478–481. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Oakley GJ, Fuhrer K and Seethala RR:

Brachyury, SOX-9, and podoplanin, new markers in the skull base

chordoma vs chondrosarcoma differential: A tissue microarray-based

comparative analysis. Mod Pathol. 21:1461–1469. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Medical Research Council: Nerve Injuries

Committee, . M.R.C. War Memorandum: Aids to the investigation of

peripheral nerve injuries. Physical Therapy. 23:1401943. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Choi JH and Ro JY: The 2020 WHO

classification of tumors of soft tissue: Selected changes and new

entities. Adv Anat Pathol. 28:44–58. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lin JW, Ho JT, Lin YJ and Wu YT: Chordoid

meningioma: A clinicopathologic study of 11 cases at a single

institution. J Neurooncol. 100:465–473. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Santegoeds RGC, Temel Y,

Beckervordersandforth JC, Van Overbeeke JJ and Hoeberigs CM:

State-of-the-art imaging in human chordoma of the skull base. Curr

Radiol Rep. 6:162018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Golden L, Pendharkar A and Fischbein NJc:

Chapter 7 - Imaging Cranial Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma.

Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas of the Skull Base and Spine. 2nd

Edition. Elsevier Inc.; pp. 67–78. 2018, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Farsad K, Kattapuram SV, Sacknoff R, Ono J

and Nielsen GP: Sacral chordoma. Radiographics. 29:1525–1530. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Loken EK and Huang RY: Advanced meningioma

imaging. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 34:335–345. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sangoi AR, Dulai MS, Beck AH, Brat DJ and

Vogel H: Distinguishing chordoid meningiomas from their histologic

mimics: An immunohistochemical evaluation. Am J Surg Pathol.

33:669–681. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lehtonen E, Stefanovic V and Saraga-Babic

M: Changes in the expression of intermediate filaments and

desmoplakins during development of human notochord.

Differentiation. 59:43–49. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Folpe AL, Agoff SN, Willis J and Weiss SW:

Parachordoma is immunohistochemically and cytogenetically distinct

from axial chordoma and extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Am J

Surg Pathol. 23:1059–1067. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Vujovic S, Henderson S, Presneau N, Odell

E, Jacques TS, Tirabosco R, Boshoff C and Flanagan AM: Brachyury, a

crucial regulator of notochordal development, is a novel biomarker

for chordomas. J Pathol. 209:157–165. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dridi M, Boutonnat J, Dumollard JM, Peoc'h

M and Karpathiou G: Patterns of brachyury expression in chordomas.

Ann Diagn Pathol. 53:1517602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Miettinen M, Wang Z, Lasota J, Heery C,

Schlom J and Palena C: Nuclear brachyury expression is consistent

in chordoma, common in germ cell tumors and small cell carcinomas,

and rare in other carcinomas and sarcomas: An immunohistochemical

study of 5229 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 39:1305–1312. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Scheil S, Brüderlein S, Liehr T, Starke H,

Herms J, Schulte M and Möller P: Genome-wide analysis of sixteen

chordomas by comparative genomic hybridization and cytogenetics of

the first human chordoma cell line, U-CH1. Genes Chromosomes

Cancer. 32:203–211. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hallor KH, Staaf J, Jönsson G, Heidenblad

M, Vult von Steyern F, Bauer HC, Ijszenga M, Hogendoorn PC, Mandahl

N, Szuhai K and Mertens F: Frequent deletion of the CDKN2A locus in

chordoma: Analysis of chromosomal imbalances using array

comparative genomic hybridisation. Br J Cancer. 98:434–442. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kuźniacka A, Mertens F, Strömbeck B,

Wiegant J and Mandahl N: Combined binary ratio labeling

fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of chordoma. Cancer

Genet Cytogenet. 151:178–181. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Roberts CW and Biegel JA: The role of

SMARCB1/INI1 in development of rhabdoid tumor. Cancer Biol Ther.

8:412–416. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim KH and Roberts CWM: Targeting EZH2 in

cancer. Nat Med. 22:128–134. 2016. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Horbinski C, Oakley GJ, Cieply K, Mantha

GS, Nikiforova MN, Dacic S and Seethala RR: The prognostic value of

Ki-67, p53, epidermal growth factor receptor, 1p36, 9p21, 10q23,

and 17p13 in skull base chordomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

134:1170–1176. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wei J, Wu J, Yin Z, Li X, Liu Y, Wang Y,

Wang Z, Xu C and Fan L: Low expression of H3K27me3 is associated

with poor prognosis in conventional chordoma. Front Oncol.

12:10484822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Margueron R and Reinberg D: The polycomb

complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 469:343–349. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Karele EN and Paze AN: Chordoma: To know

means to recognize. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1877:1887962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Heery CR, Palena C, McMahon S, Donahue RN,

Lepone LM, Grenga I, Dirmeier U, Cordes L, Marté J, Dahut W, et al:

Phase I study of a poxviral TRICOM-based vaccine directed against

the transcription factor brachyury. Clin Cancer Res. 23:6833–6845.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yurter A, Sciubba D, Gokaslan Z and

Kaloostian PJJN: Spinal Chordomas: Current Medical and Surgical

Management: JSM Neurosurgery and Spine. 2014.

|

|

30

|

Pan Y, Lu L, Chen J, Zhong Y and Dai Z:

Analysis of prognostic factors for survival in patients with

primary spinal chordoma using the SEER Registry from 1973 to 2014.

J Orthop Surg Res. 13:762018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Daoud EV, Zhu K, Mickey B, Mohamed H, Wen

M, Delorenzo M, Tran I, Serrano J, Hatanpaa KJ, Raisanen JM, et al:

Epigenetic and genomic profiling of chordoid meningioma:

Implications for clinical management. Acta Neuropathol Commun.

10:562022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tahta A, Genc B, Cakir A and Sekerci Z:

Chordoid meningioma: Report of 5 cases and review of the

literature. Br J Neurosurg. 37:41–44. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ren L, Hua L, Deng J, Cheng H, Wang D,

Chen J, Xie Q, Wakimoto H and Gong Y: Favorable long-term outcomes

of chordoid meningioma compared with the other WHO grade 2

meningioma subtypes. Neurosurgery. 92:745–755. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Rekhi B and Karmarkar S:

Clinicocytopathological spectrum, including uncommon forms, of nine

cases of chordomas with immunohistochemical results, including

brachyury immunostaining: A single institutional experience.

Cytopathology. 30:229–235. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Murali R and Ng T: Chordoid meningioma

masquerading as chordoma. Pathology. 36:198–201. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Presneau N, Shalaby A, Ye H, Pillay N,

Halai D, Idowu B, Tirabosco R, Whitwell D, Jacques TS, Kindblom LG,

et al: Role of the transcription factor T (brachyury) in the

pathogenesis of sporadic chordoma: A genetic and functional-based

study. J Pathol. 223:327–335. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Goode B, Mondal G, Hyun M, et al: A

recurrent kinase domain mutation in PRKCA defines chordoid glioma

of the third ventricle. Nat Commuml. 9:8102018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Reifenberger G, Weber T, Weber RG, Wolter

M, Brandis A, Kuchelmeister K, Pilz P, Reusche E, Lichter P and

Wiestler OD: Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle:

Immunohistochemical and molecular genetic characterization of a

novel tumor entity. Brain Pathol. 9:617–626. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ogura K, Fujiwara T, Beppu Y, Chuman H,

Yoshida A, Kawano H and Kawai A: Extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma: A review of 23 patients treated at a single

referral center with long-term follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.

132:1379–1386. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Flucke U, Tops BBJ, Verdijk MAJ, van Cleef

PJH, van Zwam PH, Slootweg PJ, Bovée JVMG, Riedl RG, Creytens DH,

Suurmeijer AJH and Mentzel T: NR4A3 rearrangement reliably

distinguishes between the clinicopathologically overlapping

entities myoepithelial carcinoma of soft tissue and cellular

extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Virchows Archiv. 460:621–628.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S,

Halai D, Berisha F, Pollock R, O'Donnell P, Grigoriadis A, Diss T,

et al: IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central

chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in

other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 224:334–343. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Pansuriya TC, van Eijk R, d'Adamo P, van

Ruler MAJH, Kuijjer ML, Oosting J, Cleton-Jansen AM, van Oosterwijk

JG, Verbeke SLJ, Meijer D, et al: Somatic mosaic IDH1 and IDH2

mutations are associated with enchondroma and spindle cell

hemangioma in Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome. Nat Genet.

43:1256–1261. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|