Introduction

Currently, gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most

common cancer types and the leading cause of cancer-associated

mortality worldwide (1–6). According to the 2020 global cancer

statistics, GC) remained a significant global health burden in

2020, causing 10.89 million new cancer cases and 7.69 million

deaths worldwide. This positioned it as the fifth most common

malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality

(7). In the early stages,

GC-associated symptoms are unclear or absent. In the majority of

cases, it has progressed to a stage that is not amenable to radical

surgery at the time of diagnosis. In most cancer databases, GC is

labeled stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) because, in 95% of GC cases,

this is the predominant histological subtype of gastrointestinal

malignancy (8). To date,

therapeutic outcomes for STAD remain limited, with a 5-year overall

survival (OS) rate <10% in patients with advanced STAD (9). Recurrence is common even after

resection (10). Therefore, the

identification of new biomarkers is key for guiding systemic

treatment strategies. This highlights the urgency of developing an

accurate prognostic model and novel therapeutic targets for

patients with STAD.

Ferroptosis is a type of iron-dependent programmed

cell death that is distinct from apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy.

The primary mechanism is the catalysis of lipid peroxidation of

unsaturated fatty acids highly expressed on the cell membrane in

the presence of divalent iron or ester oxygenase, which induces

cell death. This results in a decrease in the regulation of the

antioxidant system (glutathione system) (11–17).

It is hypothesized that ferroptosis is associated with the

occurrence and development of tumors, such as liver and gastric

cancer (12,18–21).

The association between ferroptosis and GC has also been

increasingly recognized (22–36),

and ferroptosis is hypothesized to serve a vital role in GC

development and progression (37,38).

Thus, targeting ferroptosis may be a potential therapeutic strategy

for patients with GC.

Ferroptosis is a double-edged sword in

gastrointestinal disease, since the inhibition of ferroptosis

relieves the symptoms of intestinal injury, and the induction of

ferroptosis via pharmacological agonists or bioactive compounds

inhibits the proliferation of GC (32). Ferroptosis inducers affect different

steps in ferroptosis to regulate GC proliferation, invasion and

metastasis, although development of drug resistance in GC cells

poses a hurdle (23). However,

limitations exist in previous studies (23,31,39–41).

Firstly, the efficacy of the prognostic models for GC based on

ferroptosis-related genes is poor, as demonstrated by the fact that

the log-rank P-values in the prognostic models are often not low

enough (P>0.01), the hazard ratios of high- vs. low-risk are not

high enough and the optimal area under the curve (AUC) values of

the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves are often ~0.7

(39) . Secondly, considering the

dual nature of ferroptosis, its role in GC progression remains

controversial, and needs to be clarified with more evidence.

Thirdly, the roles of numerous important drivers and suppressors

[solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11)/Glutathione Peroxidase

4 (GPX4)] of ferroptosis in GC progression remain unclear. Finally,

novel therapeutic strategies based on targeting ferroptosis,

including potential small molecule drugs and microRNAs (miRNAs or

miRs) as molecular drugs to regulate gene expression, remain to be

explored.

The present study aimed to identify key

ferroptosis-related genes associated with the development of GC to

construct prognostic models and identify new molecular mechanisms

and potential treatment strategies. The present findings may serve

as a reference for future studies on the mechanism underlying

ferroptosis and treatment of GC.

Materials and methods

Key gene screening and survival

prediction via the Cox regression model

Ferroptosis-related genes were collected from FerrDb

(zhounan.org/ferrdb/current/), which is an open-source, open

access, manually curated and continuously updated database

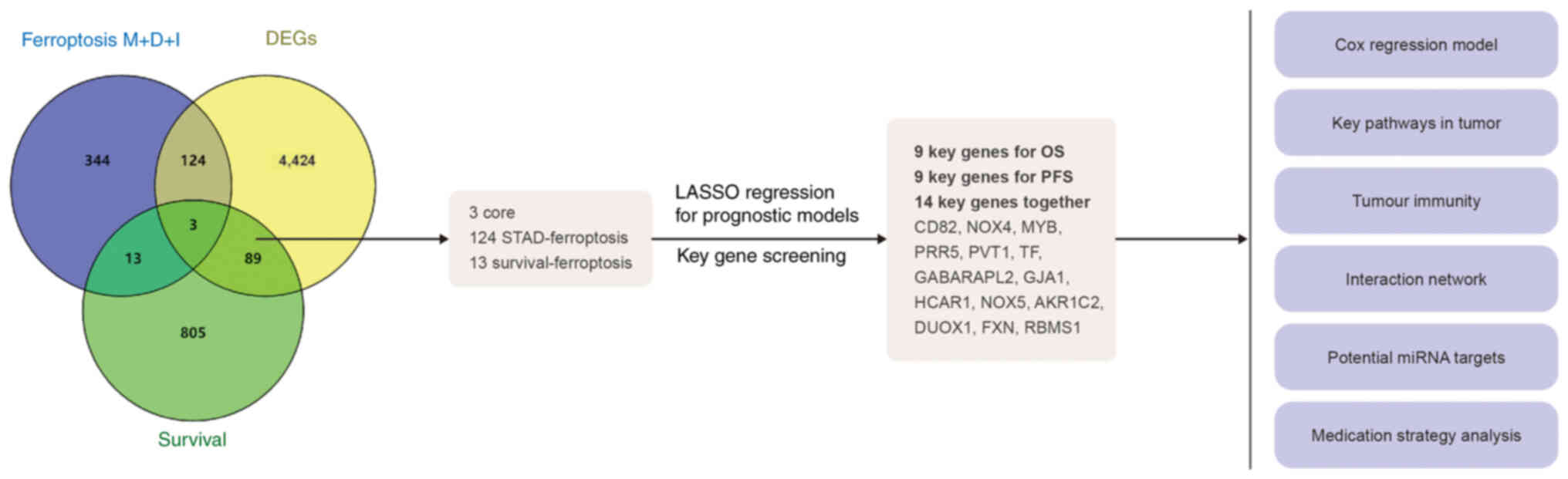

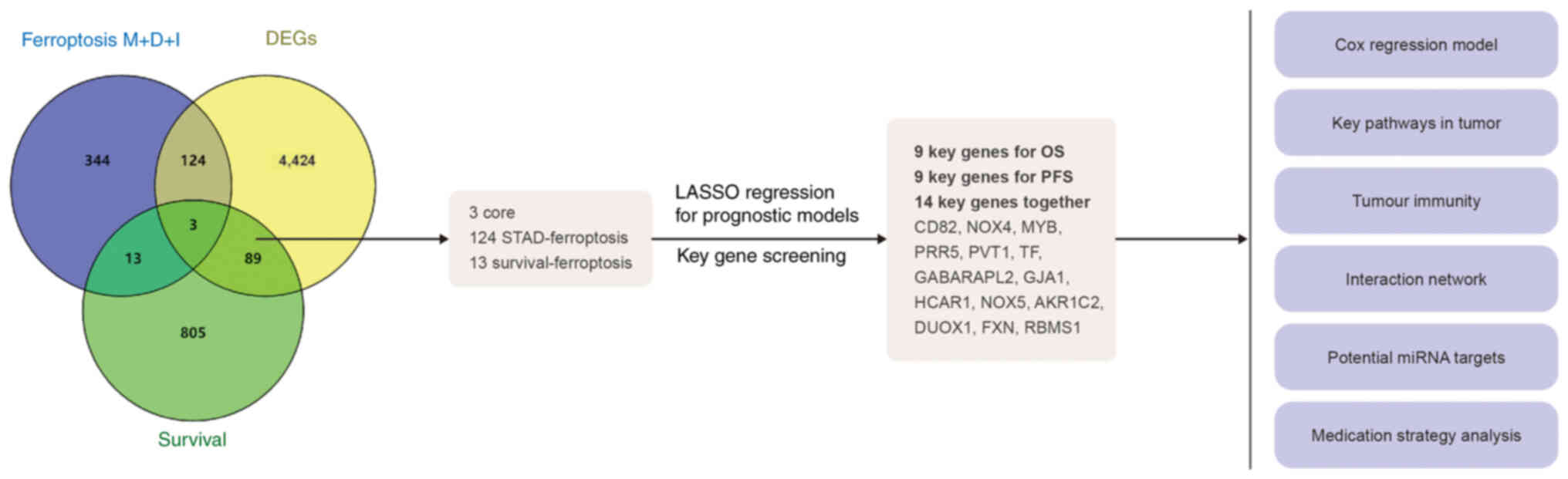

(Fig. 1). There were 12 ferroptosis

markers, 369 ferroptosis driver items and 348 ferroptosis

suppressor (or inhibitor) items. Following deduplication, 484

ferroptosis-related genes remained. Subsequently, using the Gene

Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2

database(gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), the 500 top OS- and

progression-free survival (PFS)-associated genes were identified,

and 910 survival-related genes were identified following

deduplication. In addition, there were 4,640 differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) between STAD and adjacent normal tissue. The

intersection of these three sets was analyzed, and three common

elements were found in addition to 124 STAD-ferroptosis genes and

13 survival-ferroptosis genes. These 140 genes were used to

establish the prognostic models.

| Figure 1.Flow chart of the present study. A

total of 140 key ferroptosis-related genes were obtained, and 14

key genes were screened by LASSO and prognostic models for the

following analyses: i) Optimized Cox regression model, ii) key

pathway analysis in tumors, iii) immunity analysis and iv)

identification of potential miRNAs and drug targeting key

carcinogenic ferroptosis genes in STAD. M, marker; D, driver; I,

inhibitor; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

regression; miRNA, microRNA; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; DEG,

differentially expressed gene; OS, overall survival; PFS,

progression-free survival; NOX, NADPH oxidase; MYB, MYB

proto-oncogene, transcription factor; PRR5, proline-rich protein 5;

PVT1, Pvt1 oncogene; TF, transferrin; GABARAPL2, GABA type A

receptor-associated protein-like 2; GJA1, gap junction protein α1;

HCAR1, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1; AKR1C2, aldo-keto

reductase family 1 member C2; DUOX1, dual oxidase 1; FXN, frataxin;

RBMS1, RNA binding motif single stranded interacting protein 1. |

For OS and PFS prediction, two multivariate Cox

regression models were established based on gastric cancer (STAD)

samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; Project ID: TCGA-STAD;

Data Portal: http://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), as described in the

original pan-cancer analysis by TCGA Research Network (42). Least absolute shrinkage and

selection operator (LASSO) regression algorithm was used for

feature selection using 10-fold cross-validation and nine features

were selected. The equations of the Cox regression models were

calculated as risk scores, and patients were divided into high- and

low-risk groups using the median value as the cutoff (1.85). The

log-rank test was used to compare differences in survival between

the high- and low-risk groups. For the Kaplan-Meier curves, the

P-values and hazard rations (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals

(CIs) were generated using log-rank tests. ROC curves with AUC

values were constructed to assess the efficacy of the Cox

regression models. The key features (genes) of the models were

collected, and aggregated into the key gene set. As the performance

of OS was still not satisfactory (as the aim was to reduce the

likelihood ratio test and the log-rank P-value to

<1×10−12), another Cox regression model was

constructed after the key genes were obtained using the Tumor

Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) database

(timer2.compbio.cn/timer1/). The model incorporated demographic and

clinical features(age, tumor stage), and removed certain

unimportant gene expression features(MYB, PRP5) to ensure that the

log-rank P-value was <1×10−12.

Roles of key genes in STAD

For each key ferroptosis gene in STAD, the

expression between tumor and adjacent normal tissue was compared.

The expression trends from stages I to IV were acquired via the

Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) online tool

(guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/). Using the same tool (based on the TCGA

datasets), the association between gene expression and different

types of survival [disease-specific survival (DSS), OS and PFS]

were presented in a bubble plot (where red indicates increased

risk). Additionally, the association between key gene expression

levels and the activation/inhibition of important pathways in

cancer development were using the GSCA tool.

Key-gene interaction networks

Using the GeneMANIA online tool (genemania.org/),

the interaction networks between 14 key genes were explored by

focusing on genetic and physical protein interactions and

co-expression.

Tumor immunity analysis based on key

ferroptosis genes in STAD

Using the TIMER database, the immune characteristics

of the cells were evaluated. Correlation between key ferroptosis

genes in STAD and tumor-infiltrating immune cells was determined

using Pearson's coefficient. The present study focused only on

immune cells with expression of key ferroptosis genes >0.3

(P<0.001).

Potential miRNAs that target key

carcinogenic ferroptosis genes in STAD

Among the 14 key ferroptosis genes, the carcinogenic

genes in STAD were selected according to the following criteria: i)

Coefficient in the prognostic equation should be >0.05 (for

either PFS or OS) and ii) expression tendency should be in

increasing order from stage I to IV or significant risk factors for

OS and PFS (univariate analysis). Overall, seven genes were

regarded as key carcinogenic ferroptosis genes in STAD. Using the

miRWalk database(mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/), the miRNAs

targeting these seven genes were downloaded. The miRNAs with the

most matching pairs (base-pairing sequences with the seven genes)

and the greatest number of target genes were considered to have a

potential therapeutic value.

Potential drugs based on key

ferroptosis genes in STAD

The GSCA tool was used to identify potential drugs

for treating STAD. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC)

and Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) databases

(cancerrxgene.org/; portals.broadinstitute.org/ctrp/) were used to

obtain the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)

values of the drugs. The drugs were ranked by the integrated level

of the correlation coefficient and false discovery rate values, and

the top 30 ranked drugs were shown in bubble plots. In addition,

theoretically, if IC50 is significantly negatively

correlated with a greater number of carcinogenic mRNAs, this

suggests a greater likelihood that the drug will exert an anti-STAD

effect.

Human tissue collection

The tumors and surrounding normal tissue (distance,

3–5 cm from the tumor tissue) of 20 patients (12 males and 8

females, aged 18–60 years) with GC who underwent surgical resection

in The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University

(Kunming, China) from April to July 2024 were collected. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients diagnosed with GC

by pathological examination; ii) aged ≥18 years and ≤60 years; iii)

received tumor resection surgery; iv)did not receive preoperative

chemotherapy, radiotherapy, biotherapy or traditional Chinese

medicine; and v) followed the normal follow-up requirements. In

addition, the exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients with

other primary types of cancer; ii) with needle or blood phobia; and

iii) pregnant women or lactating mothers. The present study was

approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical

University Ethics Committee (approval no. 2024 lunshen L no. 78).

All samples were obtained with written informed consent obtained

from patients, and the study adhered to the ethical principles of

the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell culture and transfection

The GC cell line AGS was purchased from American

Type Culture Collection and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Procell)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Procell) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin in 5% CO2 in a humidified

atmosphere at 37°C. Following 24 h culture, the Homo sapiens

(hsa)-miR-501-5p inhibitor (delivered as siRNA) and hsa-miR-484

mimic were transfected separately, along with their respective

negative controls, using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Thermo

Fisher Scientific), and incubated. The concentrations used were 50

nM for miR-484 mimic and 100 nM for miR-501-5p siRNA. Transfection

was carried out at 37°C for 6 h. Cells were harvested 48 h

post-transfection for subsequent assays. hsa-miR-484 mimic,

hsa-miR-501-5p inhibitor (siRNA format) and non-targeting scrambled

negative controls were designed and synthesized by Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd. The sequences were as follows: miR-484 mimic:

Forward, 5′-UCAGGCUCAGUCCCCUCCCGAU-3′ and

R:5′-CGGGAGGGGACUGAGCCUGAGC-3′ and mimic negative controls:

Forward, 5′-UUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAAGC-3′; miR-501-5p siRNA:

F:5′-UCUCACCCAGGGACAAAGGA-3′ and R:5′-UCCUUUGUCCCUGGGUGAGA-3′ and

siRNA negative controls: F:5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUUU-3′ and

R:5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAUU-3′.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

TRIzol® was used to isolate RNA from GC

cell lines and tissue. According to the manufacturer's

instructions, cDNA was synthesized from RNA using a PrimeScript™ RT

reagent kit (Takara). TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II FAST

qPCR kit (Takara) was used for qPCR. qPCR was performed using the

following thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C

for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30

sec. The amplification of DNA was performed with TB

Green® Premix Ex Taq (Takara). CFX96™ Real-Time System

was used to evaluate the amplification of each gene. The primer

sequences were as follows: hsa-miR-501-5p: forward:

5′-AUCCUUUGUCCCUGGGUGAGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′;

hsa-miR-484: Forward: 5′-UCAGGCUCAGUCCCCUCCCGAU-3′ and reverse:

5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3′ and U6 sense: Forward:

5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ and reverse: 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′.

The miRNA primers were provided by Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd. U6 was

used as an endogenous control. The results were determined using

the 2−ΔΔCq method (43).

All the experiments were repeated three times.

Cell viability assay

GC AGS cells were treated with DMSO,

(5Z)-7-oxozeanol (0, 1, 2, 4 µmol/l), selumetinib (0, 12.5, 25, 50

µmol/l), RDEA119 (0, 5, 50, 100 µmol/l), AZ628 (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5

µmol/l), dabrafenib(0, 0.25, 0.5, 1 µmol/l) or trametinib (0, 0.5,

5, 50 µmol/l) (all MedChemExpress) for 0, 24, 48 or 72 h, 37°C.

Following digestion with trypsin, the total number of cells was

counted on a cell counting plate. RPMI-1640 (Procell) containing

5,000 AGS cells was added to each well of a 96-well plate. Cell

Counting Kit-8 assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used

to observe the proliferative capacity (incubation for 2 h).

Absorbance values of the cells at 450 nm were determined. All the

experiments were repeated three times.

Western blotting

Cell Lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology)

containing PMSF (1 mM, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was

used to lyse AGS cells. The BCA method was used to determine the

protein concentration. After that, the protein samples (20 µg/lane)

were separated using 8–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide

gel electrophoresis gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride membranes (MilliporeSigma), which were incubated for 2 h

in 5% skimmed milk at 25°C. Subsequently, primary antibodies were

added overnight at 4°C. Following 2 h incubation with the secondary

antibody at 25°C, the membranes were washed three times with

TBS-Tween 20 (0.1%), and ECL (cat. no. WBULS0100; Millipore) was

added to the membrane, which was placed on a GelDoc imaging system.

ImageJ software (v1.54f, http://imagej.net/ij/) was used to analyze the optical

density. The antibodies were as follows: Anti-aldo-keto reductase

family 1 member C2 (AKR1C2; 1:200; cat. no. 13035; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), anti-transferrin (TF; 1:500; cat no. 17435-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-NADPH oxidase (NOX) 4 (1:500; cat.

no. 14347-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-RNA binding motif

single stranded interacting protein 1 (RBMS1; 1:400; cat. no.

ab150353; Abcam), anti-β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG

(1:1,000; cat. no. D110087; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.). β-actin was

used as a loading control for normalization. All the experiments

were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad; Dotmatics) or SPSS

26.0 (IBM Corp.) statistical software were used to analyze the

data. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess normal

distribution. Data conforming to a normal distribution are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Paired samples were

compared with paired Student's t-test. Comparisons of >2 groups

were made with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Each experiment was independently repeated three times.

Results

Key ferroptosis genes in STAD and

prognostic models

The intersection analysis of 484 ferroptosis- and

910 survival-related genes and 4,640 DEGs in STAD revealed that 140

genes were notable ferroptosis genes in STAD. Using the 140 key

genes, the LASSO regression algorithm was used for feature

selection, and two Cox regression models for OS and FPS were

generated.

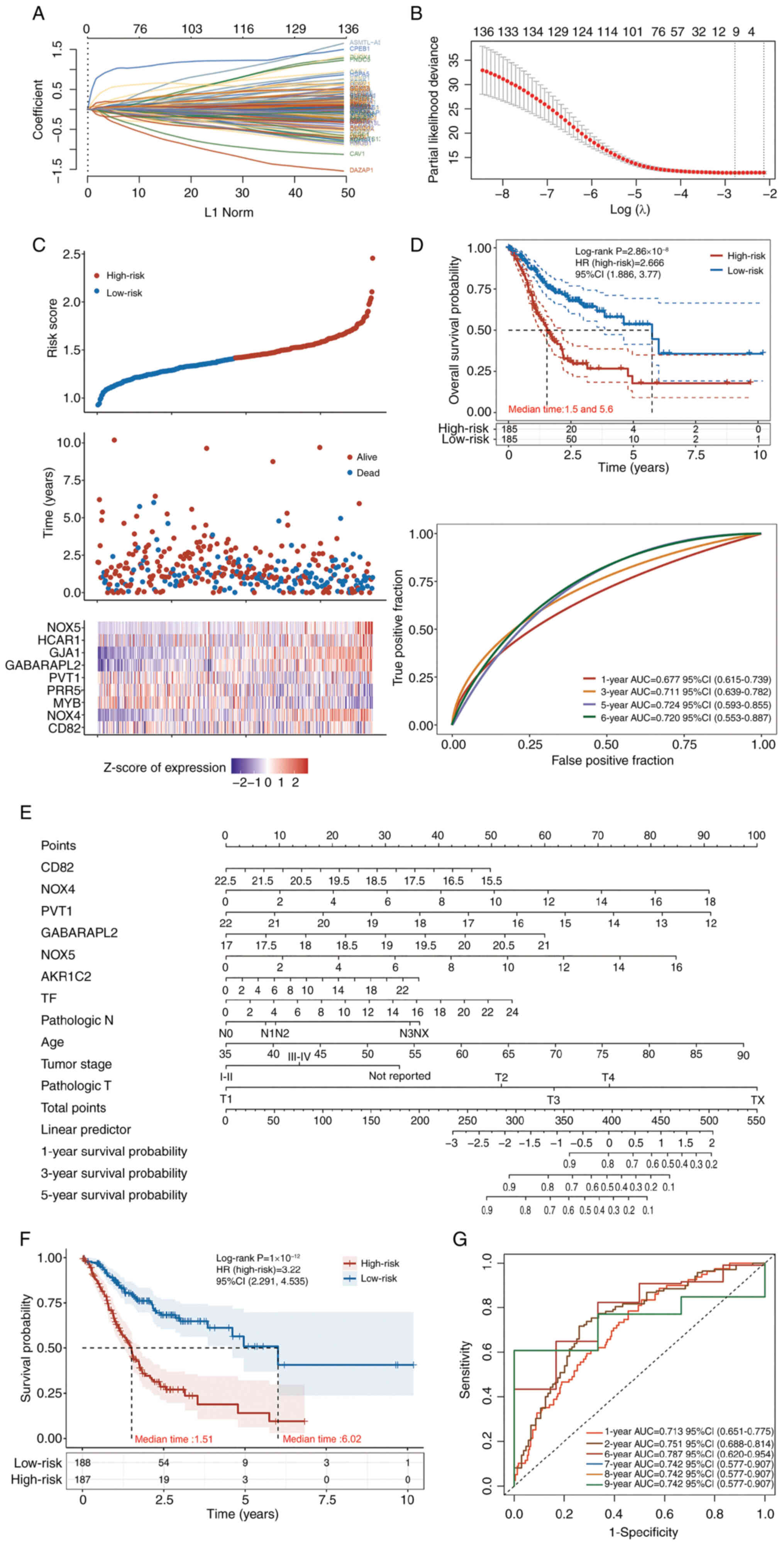

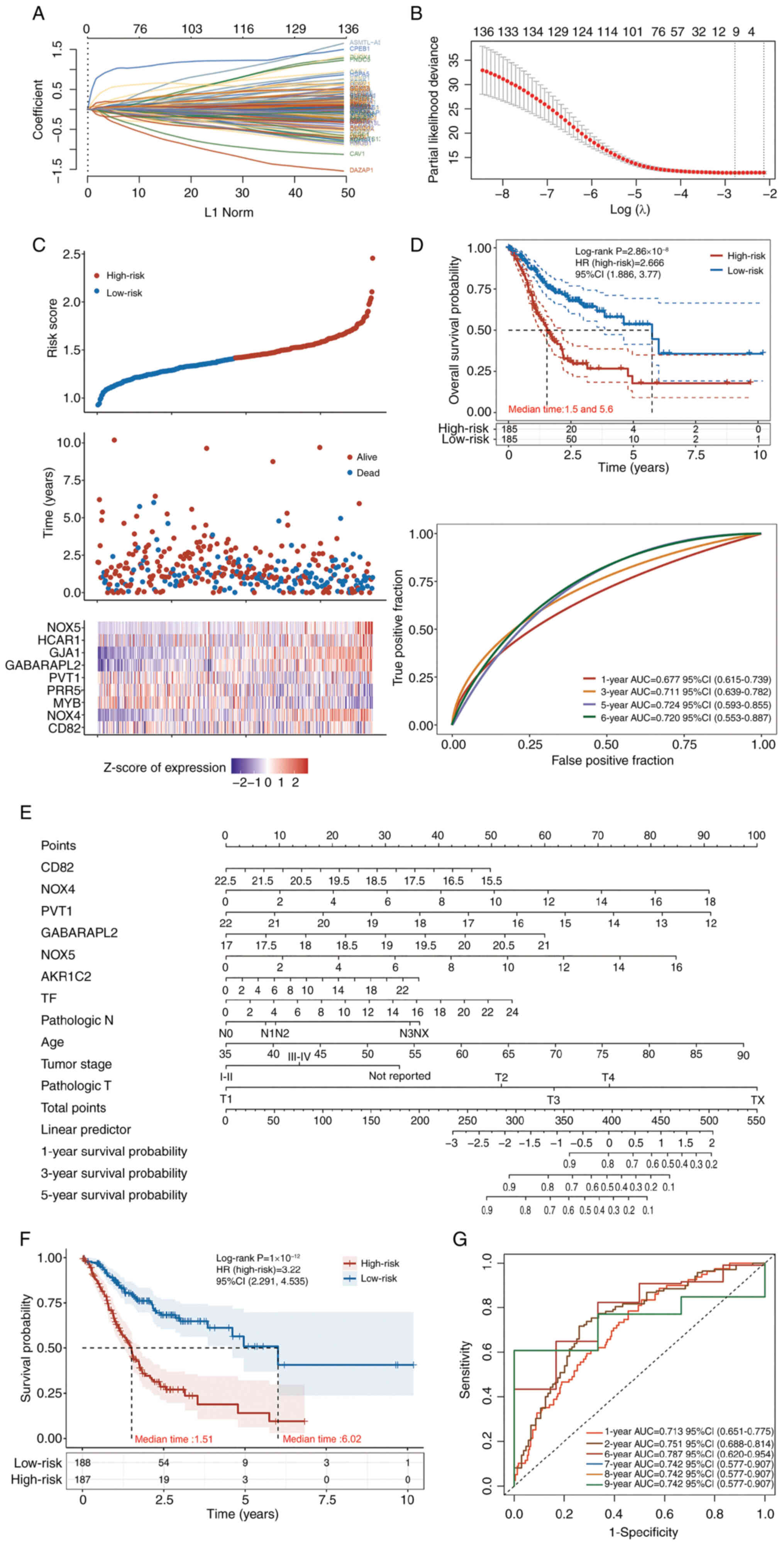

For OS prediction (Fig.

2), the regression model was as follows: Risk score=(−0.0065) ×

CD82 + (0.08) × NOX4 + (−0.0219) × MYB proto-oncogene,

transcription factor (MYB) + (−6×10−4) × proline rich

protein 5 (PRR5) + (−0.026) × Pvt1 oncogene (PVT1) + (0.1876) ×

GABA type A receptor associated protein like 2 (GABARAPL2) +

(0.0711) × gap junction protein α1 (GJA1) + (0.0086) ×

hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1 (HCAR1) + (0.5351) × NOX5. This

model contained nine features (Fig.

2A-C), among which, NOX4, NOX5, GABARAPL2 and GJA1 were the

most important risk factors. It had satisfactory efficacy in terms

of 5-6-year survival (AUC >0.72; Fig. 2D). The HR of the high-risk group was

2.66 (Fig. 2D). The additional OS

prediction model was constructed using seven genes(CD82, NOX4,

PVT1, GABARAPL2, TF, HCAR1and NOX5) along with several clinical

features (age, tumor stage; Fig.

2E), and validated its performance using standard Kaplan-Meier

curves and ROC curves (Fig. 2F-G).

Kaplan-Meier curves stratified patients into prognostically

distinct risk groups (log-rank P<0.0001), with the low-risk

group exhibiting a median survival time (6.02 years) four times

longer than that of the high-risk group (1.51 years). All high-risk

patients died within 5 years, whereas low-risk patients

demonstrated sustained survival with cases remaining alive at the

10-year mark (Fig. 2F). ROC

analysis confirmed the model's robust discriminative ability from 1

to 9 years (all AUC >0.70), with peak predictive performance at

6 years (AUC=0.787, 95% CI: 0.620–0.954). Strong predictive

validity was also maintained at 1 (AUC=0.713) and 2 years

(AUC=0.751), highlighting its utility for both short- and long-term

survival prediction (Fig. 2G).

| Figure 2.LASSO analysis and Cox regression

models for OS prediction. (A) Coefficients of the selected features

are shown by the λ parameter, where the horizontal coordinate

represents the value of the independent variable λ and the vertical

coordinate represents the coefficients of the independent

variables. (B) Partial likelihood deviance plotted against log(λ)

values calculated through the LASSO Cox regression model. (C)

Association between expression of nine key genes in patients with

gastric adenocarcinoma from The Cancer Genome Atlas database with

patient risk scores and survival times. (D) Median OS time of the

low- and high-risk groups, and receiver operating characteristic

curve of the Cox regression model for the prediction of OS. (E-G)

Cox regression models constructed with the key genes from TIMER

database. (E) Nomogram of the constructed COX regression model,

visually presenting the model; (F) KM curve of the model; (G) ROC

curve of the model. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection

operator; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; AUC, area under

the curve; CI, confidence interval; NOX, NADPH oxidase; MYB, MYB

proto-oncogene, transcription factor; PRR5, proline rich protein 5;

PVT1, Pvt1 oncogene; GABARAPL2, GABA type A receptor associated

protein like 2; GJA1, gap junction protein α1; HCAR1,

hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1. |

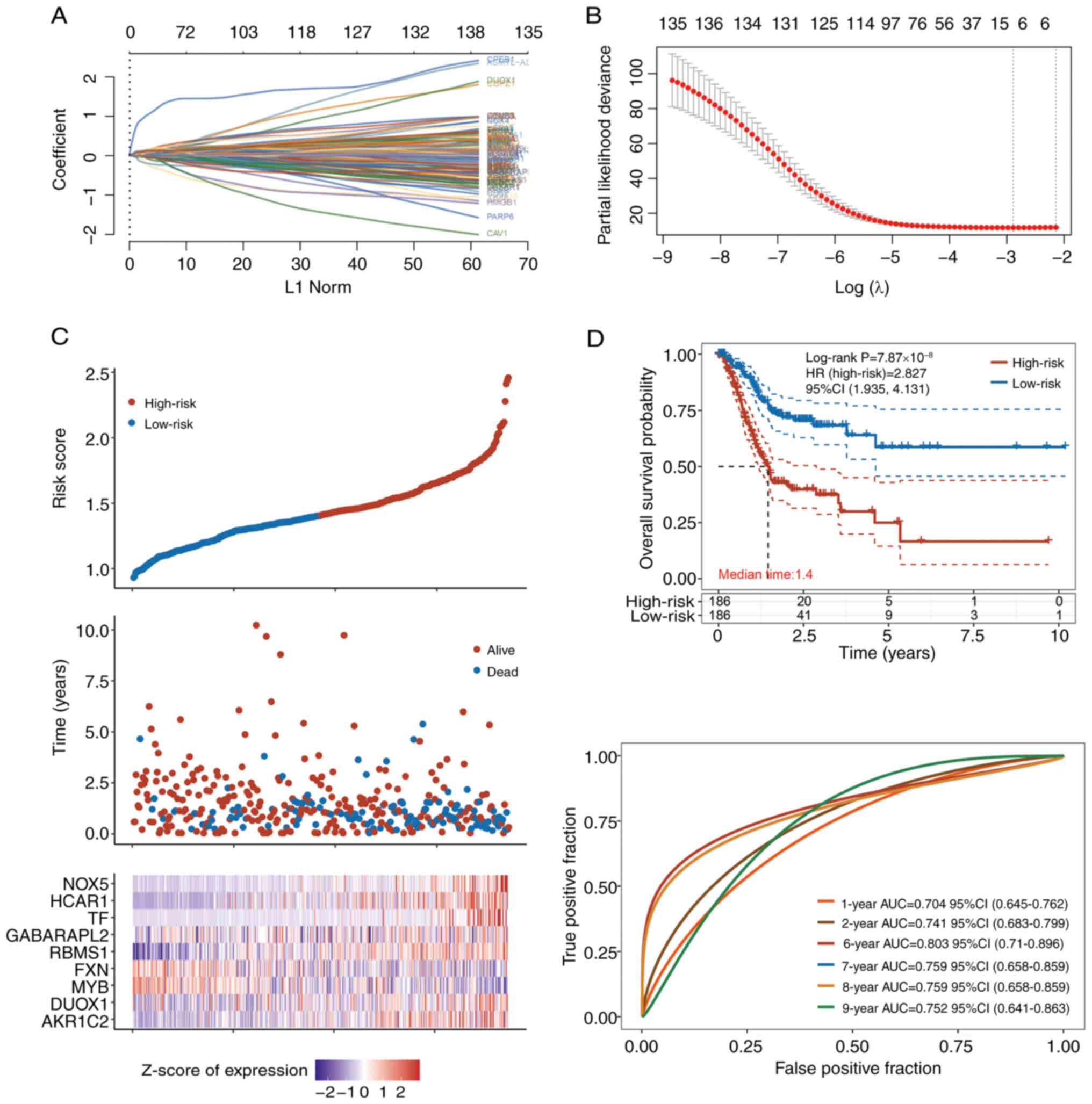

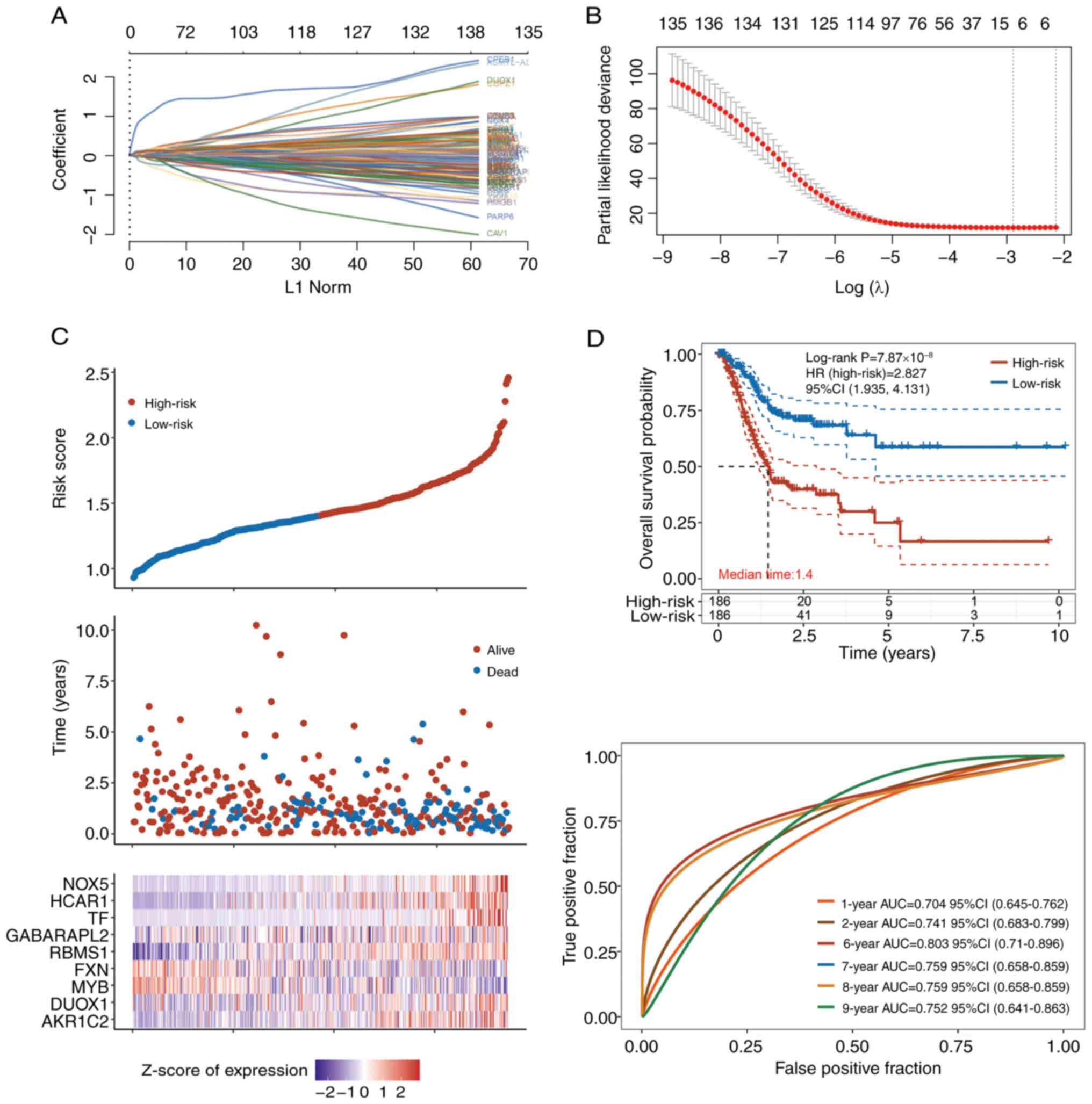

For PFS prediction (Fig.

3), the regression model was as follows: Risk score=(−0.0907) ×

AKR1C2 + (0.0074) × dual oxidase 1 + (−0.0384) × MYB + (−0.0483) ×

frataxin (FXN) + (0.118) × RBMS1 + (0.0132) × GABARAPL2 + (0.0883)

× TF + (0.066) × HCAR1 + (0.7408) × NOX5. This model also had nine

features (Fig. 3A-C), among which,

AKR1C2, RBMS1, NOX5, GABARAPL2, TF and HCAR1 were the most

important risk factors. It had good performance in the evaluation

of 6-9-year PFS; AUC of the 6-year PFS was >0.8 (Fig. 3D). The HR of the high-risk group was

2.827 (Fig. 2D).

| Figure 3.LASSO analysis and Cox regression

models for PFS prediction. (A) Coefficients of the selected

features are shown by the λ parameter, with the horizontal

coordinate representing the value of the independent variable λ and

the vertical coordinate representing the coefficients of the

independent variables. (B) Partial likelihood deviance plotted

against log(λ) values calculated via the LASSO Cox regression

model. (C) Associations between risk scores and survival times of

patients with expressing nine key genes in patients with stomach

adenocarcinoma from The Cancer Genome Atlas database. (D) Median

PFS of the low- and high-risk groups, and receiver operating

characteristic curve of the Cox regression model for the prediction

of PFS. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator;

PFS, progression-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; AUC, area under

the curve; CI, confidence interval; NOX, NADPH oxidase; MYB, MYB

proto-oncogene, transcription factor; GABARAPL2, GABA type A

receptor associated protein like 2; HCAR1, hydroxycarboxylic acid

receptor 1; TF, transferrin; AKR1C2, aldo-keto reductase family 1

member C2; DUOX1, dual oxidase 1; FXN, frataxin; RBMS1, RNA binding

motif single stranded interacting protein 1. |

Together, there were 14 unique key ferroptosis genes

identified in STAD (the combination of the nine features in the OS

model and the nine features in the PFS model), among which, NOX4,

NOX5, AKR1C2, RBMS1, GABARAPL2, GJA1, TF and HCAR1 may be the most

important carcinogenic genes (risk genes).

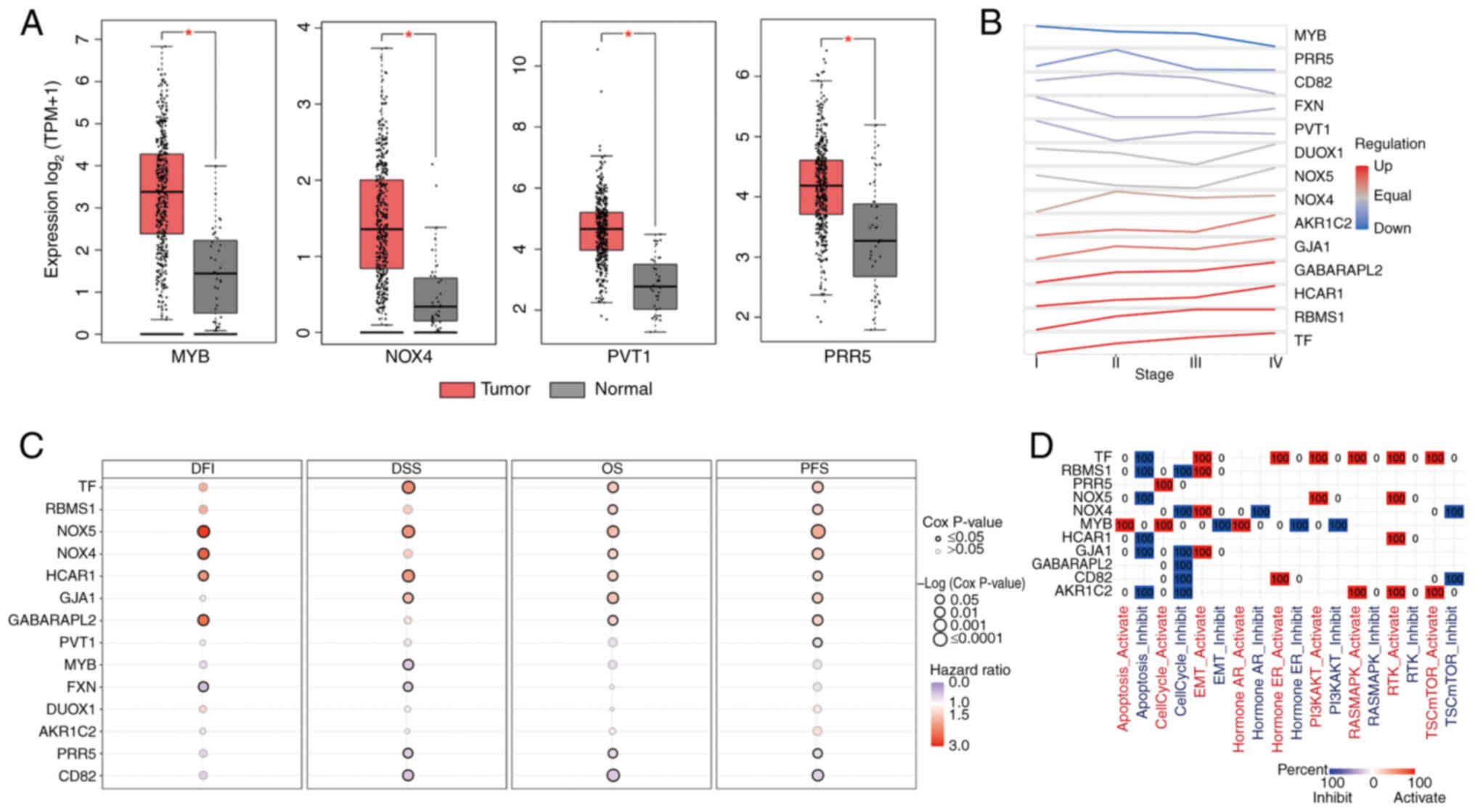

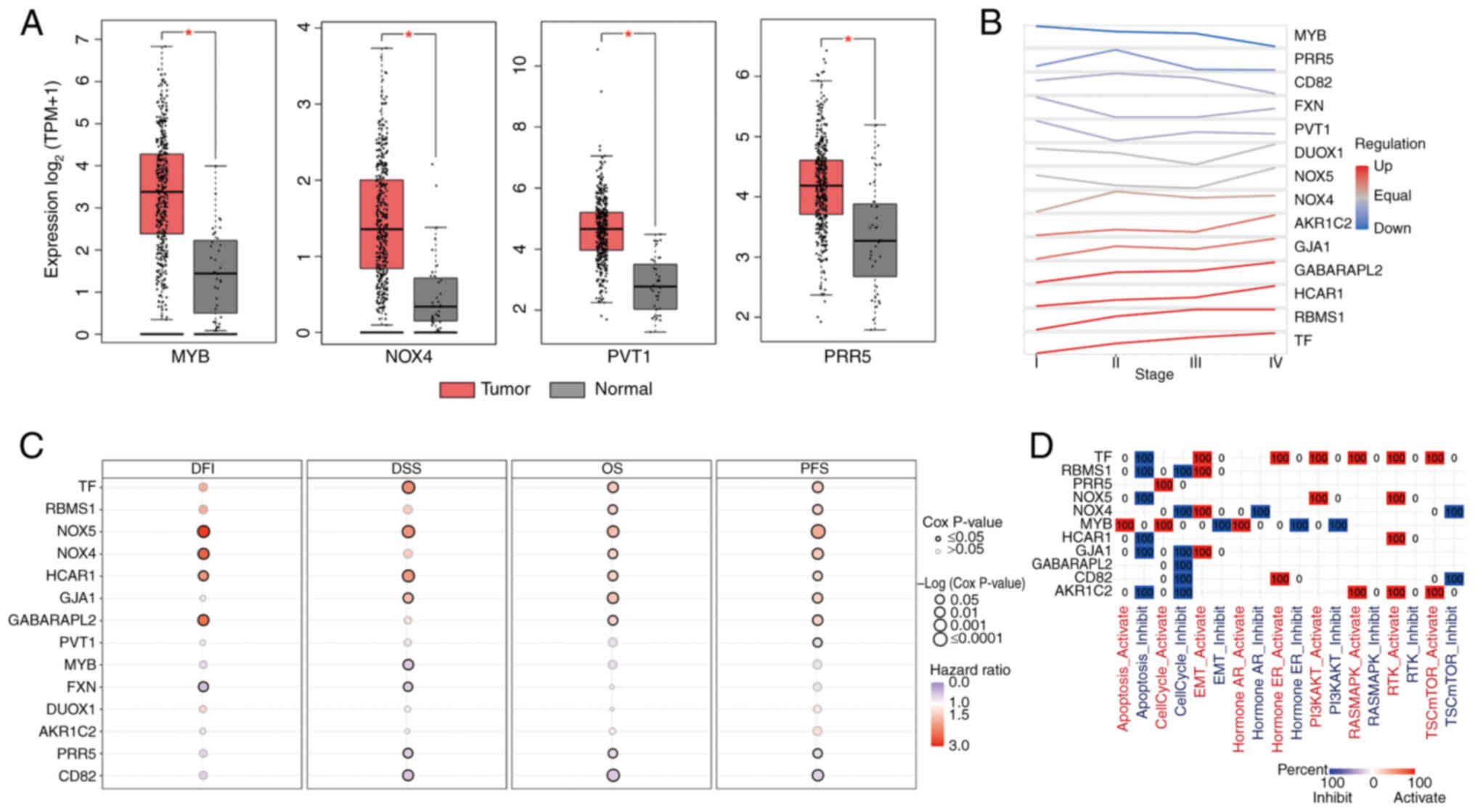

Roles of key genes in STAD

Among the 14 key genes in STAD, MYB, NOX4, PVT1 and

PRR5 exhibited increased expression in STAD tumors compared with

normal tissue (Fig. 4A). NOX4,

AKR1C2, GJA1, GABARAPL2, HCAR1, RBMS1 and TF expression tended to

increase from stages I to IV (Fig.

4B). TF, RBMS1, NOX5, NOX4, HCAR1, GJA1 and GABARAPL2 were

significant risk factors for OS and PFS (Fig. 4C). Moreover, NOX5 was a significant

risk factor not only for OS and PFS, but also for disease-free

interval and DSS. The associations between key genes and important

cancer pathways are shown in Fig.

4D. These genes suppress apoptosis and cell cycle progression

but promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and activate

protein kinase B and receptor tyrosine kinase (44–49).

| Figure 4.Roles of key ferroptosis genes in

STAD. (A) Among the 14 key genes in STAD, MYB, NOX4, PVT1 and PRR5

expression was increased in STAD tumors compared with normal

tissue. *P<0.05. (B) Expression trend of each key gene from

stages I to IV. (C) Risk genes for DFI, DSS, OS and PFS among the

14 key genes. (D) Association between key genes and cancer

pathways. STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; DFI, disease-free interval;

DSS, disease-specific survival; OS, overall survival; PFS,

progression-free survival; NOX, NADPH oxidase; MYB, MYB

proto-oncogene, transcription factor; PRR5, proline-rich protein 5;

PVT1, Pvt1 oncogene; TF, transferrin; GABARAPL2, GABA type A

receptor associated protein like 2; GJA1, gap junction protein α1;

HCAR1, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1; AKR1C2, aldo-keto

reductase family 1 member C2; DUOX1, dual oxidase 1; FXN, frataxin;

RBMS1, RNA binding motif single stranded interacting protein 1;

TPM, transcripts per million; A, activation; I, inhibition. |

Tumor immunity associated with key

ferroptosis genes in STAD

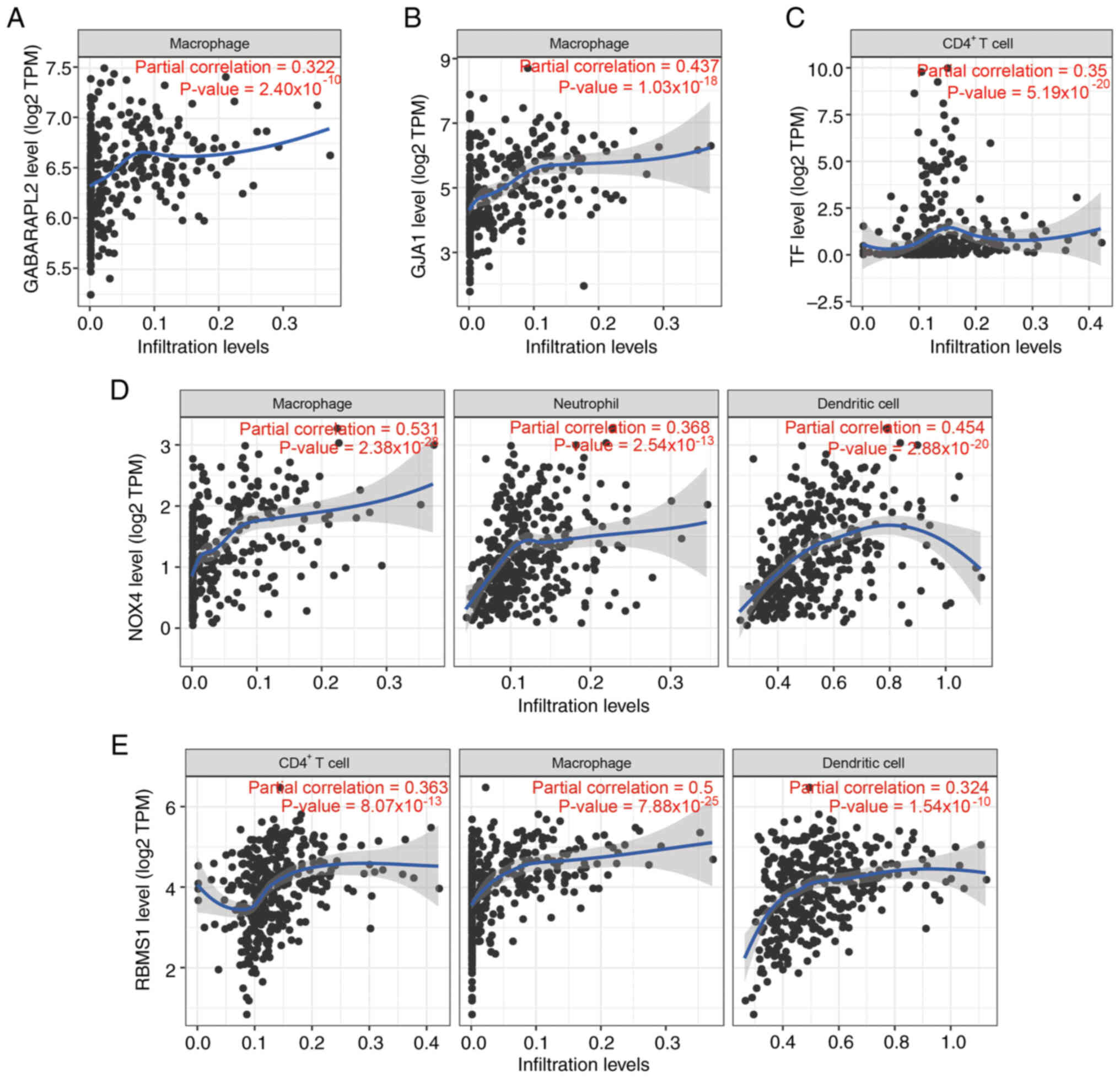

The present study focused on key ferroptosis genes

correlated (r>0.3; P<0.001) with immune cells in STAD tumors.

GABARAPL2 and GJA1 expression was positively associated with

macrophages (Fig. 5A and B). TF

expression was positively associated with CD4+ T cells

(Fig. 5C). The NOX4 expression

levels were positively correlated with the levels of macrophages,

neutrophils and dendritic cells (Fig.

5D). RBMS1 expression was positively correlated with

CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells (Fig. 5E). These results suggest these key

ferroptosis genes may impact the immune microenvironment.

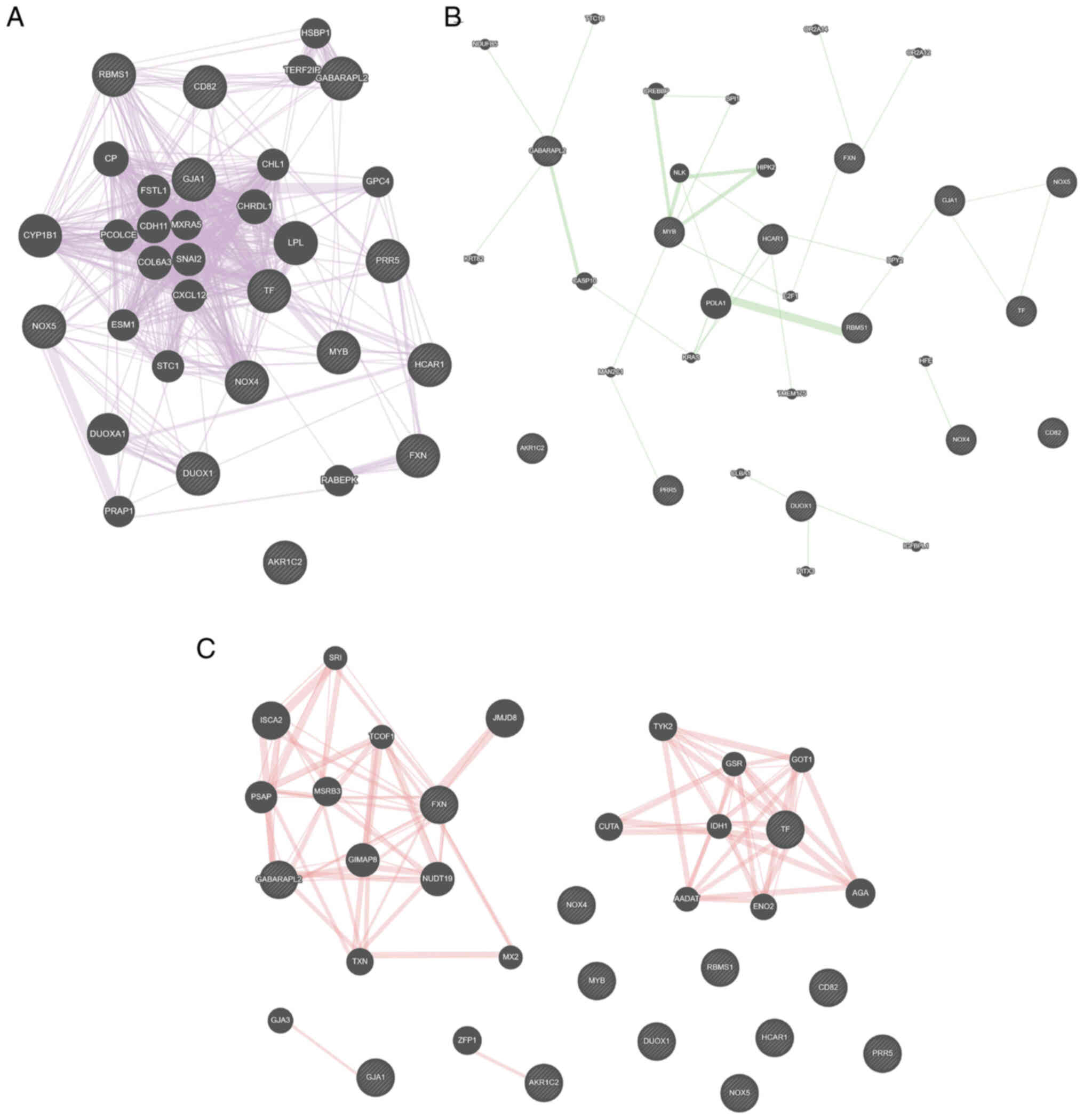

Key gene interaction networks

Using the GeneMANIA online tool, GJA1, NOX4, NOX5

and TF hub genes were identified in a co-expression network of 14

key genes (Fig. 6A). RBMS1, GJA1,

NOX5 and TF were key nodes in the genetic interaction network

(Fig. 6B), while FXN and GABARAPL2

were important nodes in the physical interaction network (Fig. 6C).

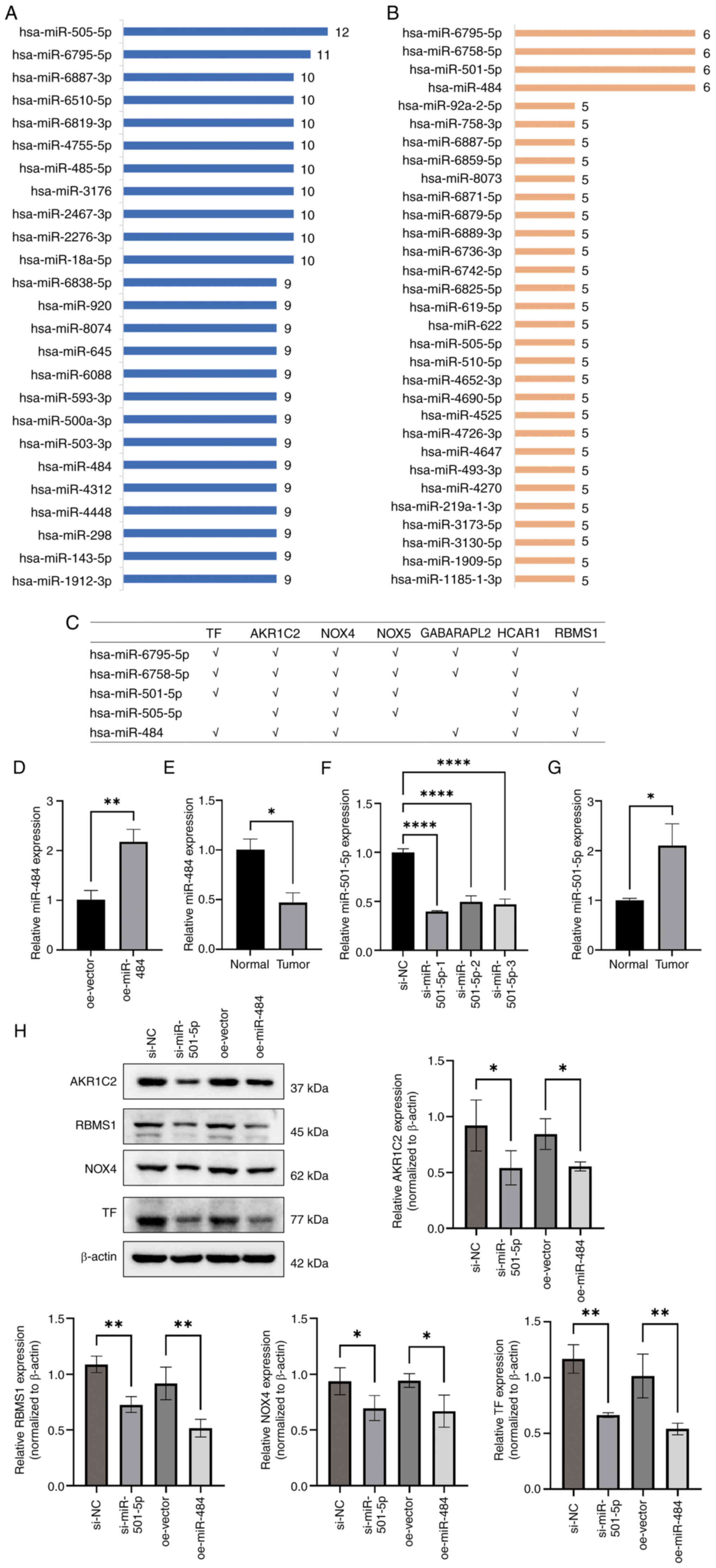

Potential miRNAs that target key

carcinogenic ferroptosis genes in STAD

Key genes were selected based on significant

prognostic weights in the Cox model (absolute value of coefficients

>0.05), positive correlation between gene expression and tumor

staging, or significant association with poor survival in

univariate analysis (P<0.05). As a result, seven genes were

regarded as key carcinogenic ferroptosis genes in STAD among the 14

key ferroptosis genes. Using the miRWalk database, the miRNAs

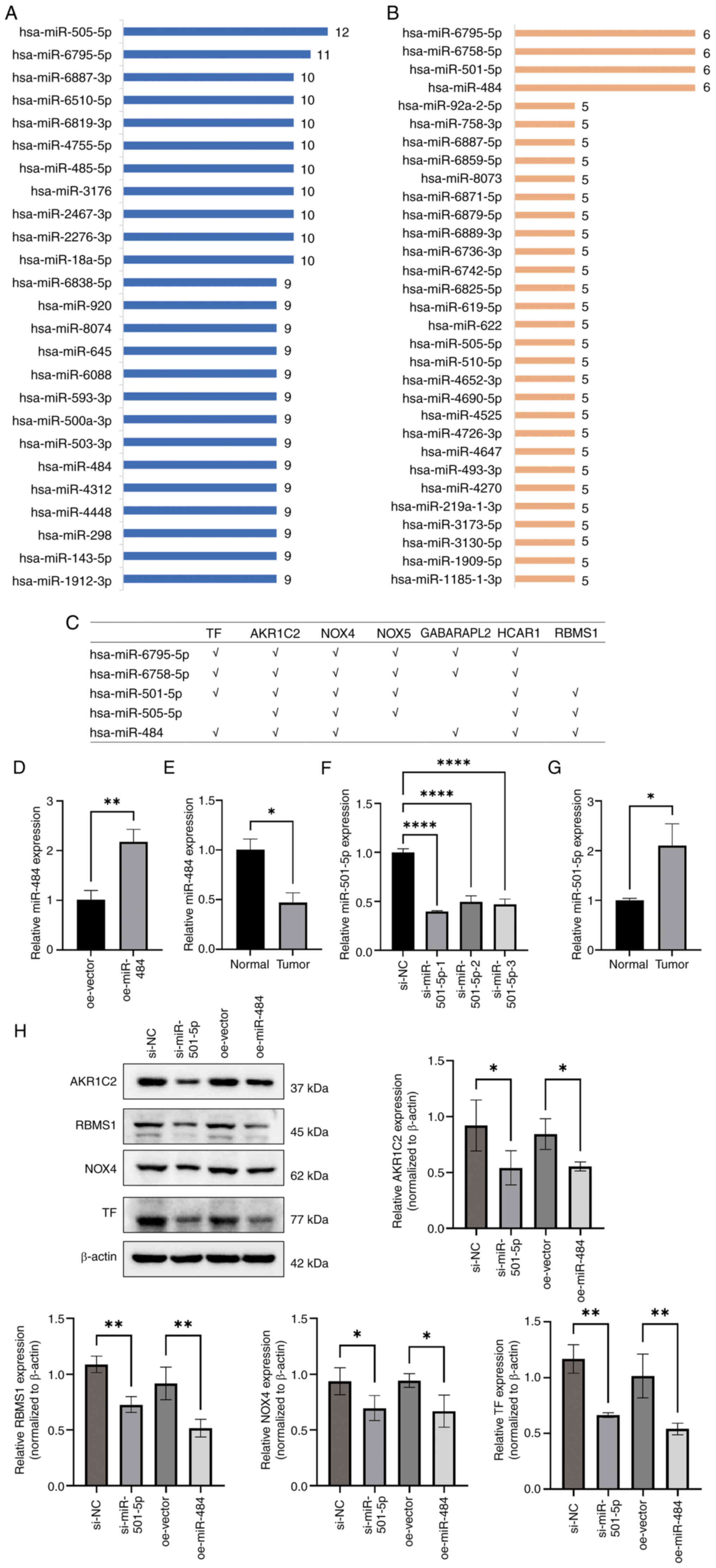

targeting these seven genes were downloaded. hsa-miR-505-5p and

hsa-miR-6795-5p presented the most targets (12 and 11 targets,

respectively; Fig. 7A). In

addition, the top miRNAs with paired key genes (six genes each)

were hsa-miR-6795-5p, hsa-miR-6758-5p, hsa-miR-501-5p and

hsa-miR-484 (Fig. 7B). Therefore,

these miRNAs (hsa-miR-6795-5p, hsa-miR-6758-5p, hsa-miR-501-5p,

hsa-miR-505-5p and hsa-miR-484) may have potential therapeutic

value for STAD; targets of these miRNAs are presented in Fig. 7C.

| Figure 7.Potential miRNAs that target key

carcinogenic ferroptosis genes in stomach adenocarcinoma. (A) Top

miRNAs with the most matching pairs to key genes. (B) Top miRNAs

with the most targeted genes. (C) A total of five miRNAs

(hsa-miR-6795-5p, hsa-miR-6758-5p, hsa-miR-501-5p, hsa-miR-505-5p

and hsa-miR-484) targeted the majority of genes (six targets each).

Relative mRNA expression of miR-484 in (D) GC cells with miR-484

overexpression and (E) tumor and surrounding normal tissue.

Relative mRNA expression of miR-501-5p in (F) GC cell line treated

with siRNAs and (G) tumor and surrounding normal tissue. (H) A

total of four risk genes for GC (AKR1C2, RBMS1, NADPH oxidase 4 and

TF) were detected via western blotting. *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

****P<0.001. miRNA/miR, microRNA; hsa, Homo sapiens; GC,

gastric cancer; siRNA, small interfering RNA; nc, negative control;

oe, overexpression; GABARAPL2, GABA type A receptor-associated

protein-like 2; TF, transferrin; AKR1C2, aldo-keto reductase family

1 member C2; NOX, NADPH oxidase; HCAR1, hydroxycarboxylic acid

receptor 1; RBMS1, RNA binding motif single stranded interacting

protein 1. |

Through target gene prediction and pathway

association analysis, target genes of miR-501-5P and miR-484

involved in core ferroptosis-related biological processes such as

lipid peroxidation, iron ion metabolism and oxidative stress were

identified (50–52). By contrast, the other candidates

lacked direct literature support or had unknown functional

relevance and require further investigation. miR-501-5p and miR-484

expression was evaluated in GC and surrounding normal tissue.

miR-484 expression was decreased, while miR-501-5P expression was

increased, in cancer tissues compared with normal tissue (Fig. 7E and G). miR-484 was overexpressed

and miR-501-5p was knocked down in AGS cells (Fig. 7D and F). Overexpression of miR-484

and the knockdown of miR-501-5p significantly decreased the

expression of the GC-associated high-risk genes AKR1C2, RBMS1, NOX4

and TF (Fig. 7H).

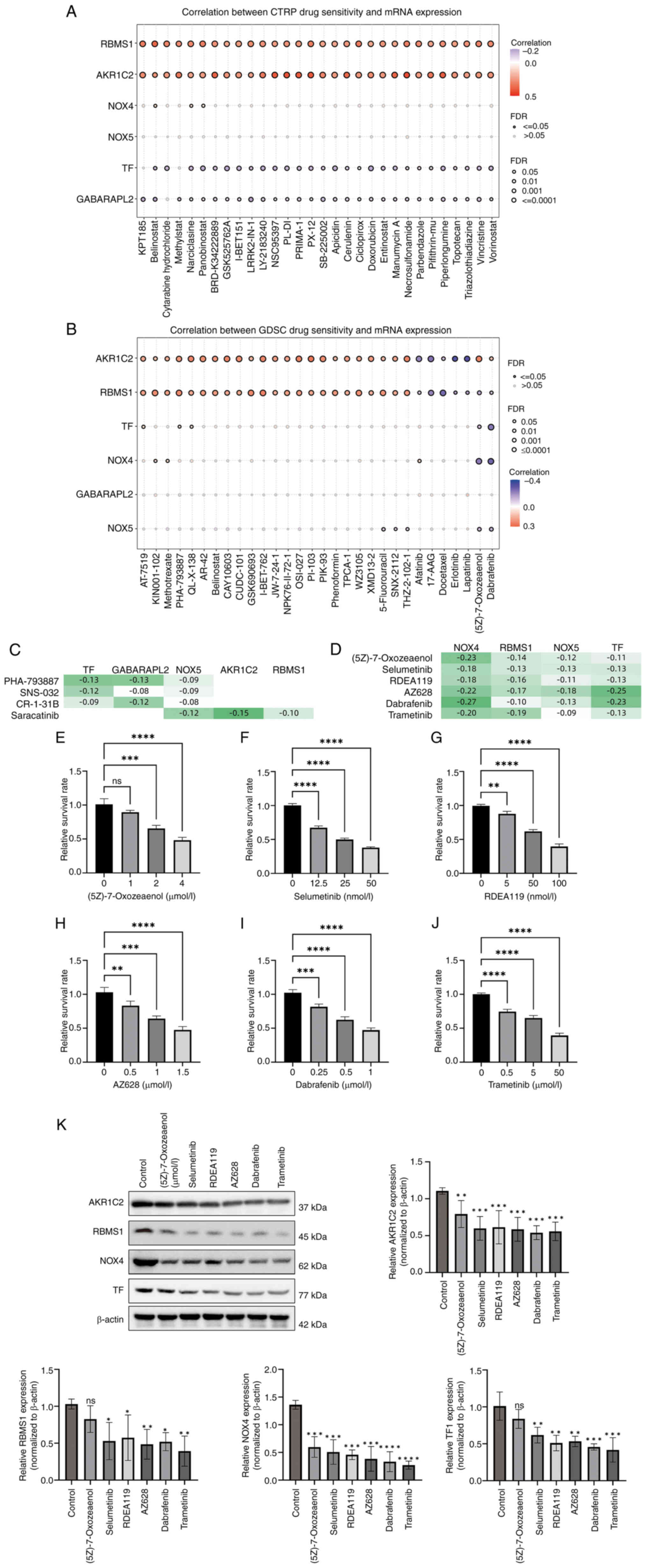

Potential drugs based on key

ferroptosis genes in STAD

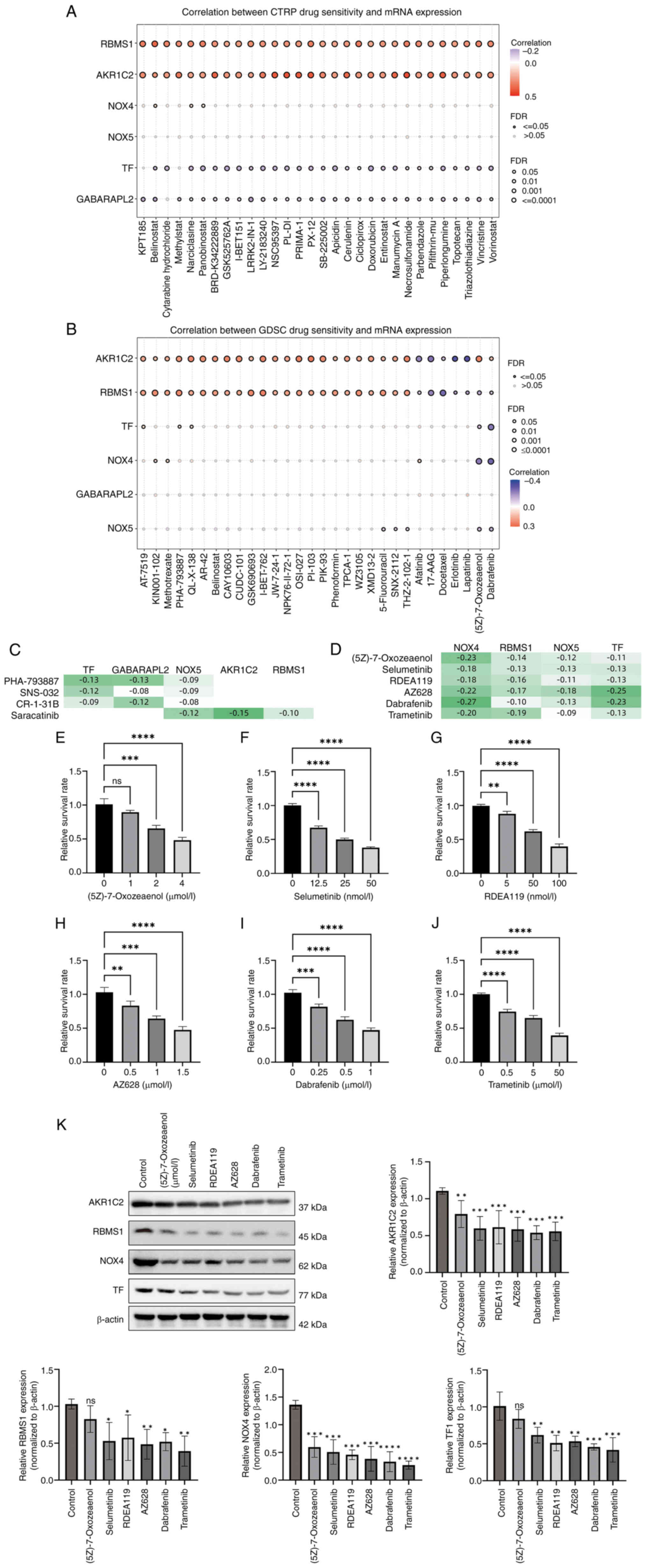

Using the GDSC and CTRP databases, potential drugs

were identified on the basis of the seven key ferroptosis-related

carcinogenic genes. The top 30 ranked drugs in the GDSC and CTRP

databases are shown in Fig. 8A and

B. The present study focused on drugs with multiple targets

(which may have greater therapeutic value). In the CTRP database,

four drugs had the most targets (targeting three genes):

PHA-793887, SNS-032, CR-1-31B and saracatinib (Fig. 8C). According to the GDSC database

(Fig. 8D), six drugs targeted four

genes simultaneously: (5Z)-7-Oxozeaenol, selumetinib, RDEA119,

AZ628, dabrafenib and trametinib. Together, these drugs may be

candidate ferroptosis-related medications for the treatment of

STAD. In AGS cells, all six drugs significantly induced GC cell

death to varying degrees (Fig.

8E-J), and significantly reduced the expression of the

high-risk genes (Fig. 8K).

| Figure 8.Potential drugs based on key

ferroptosis genes in stomach adenocarcinoma. Top 30 ranked drugs in

(A) GDSC and (B) CTRP database based on the seven key carcinogenic

genes. (C) In the CTRP database, the following four drugs had the

most targets (each targeting three genes): PHA-793887, SNS-032,

CR-1-31B and saracatinib. (D) In the GDSC database, six drugs

targeted four genes simultaneously, namely (5Z)-7-oxozeaenol,

selumetinib, RDEA119, AZ628, dabrafenib and trametinib. Drug

toxicity of (E) (5Z)-7-oxozeaenol, (F) selumetinib, (G) RDEA119,

(H) AZ628, (I) dabrafenib and (J) trametinib towards gastric cancer

cells. (K) Expression of four risk genes (AKR1C2, RBMS1, NOX4 and

TF) was downregulated in gastric cancer cells treated with the

aforementioned drugs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005;

****P<0.001. GDSC, Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer; CTRP,

Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal; AKR1C2, aldo-keto reductase

family 1 member C2; RBMS1, RNA-binding motif single stranded

interacting protein 1; NOX, NADPH oxidase; TF, transferrin; FDR,

false discovery rate; ns, not significant. |

Discussion

The present study investigated the key

ferroptosis-associated genes involved in STAD development. A total

of 14 key genes was identified, including seven carcinogenic genes

that promote STAD development and are risk factors for survival.

For OS and PFS prediction, two models were constructed; by

combining age and stage information, another powerful OS model was

generated. GABARAPL2, GJA1, NOX4 and RBMS1 may impact the immune

microenvironment. Moreover, five miRNAs (hsa-miR-6795-5p,

hsa-miR-6758-5p, hsa-miR-501-5p, hsa-miR-505-5p and hsa-miR-484)

with potential therapeutic value for STAD were identified via the

targeting of carcinogenic genes. Finally, it was hypothesized that

the following drugs may be effective in treating STAD:

(5Z)-7-Oxozeaenol, selumetinib, RDEA119, AZ628, dabrafenib and

trametinib.

Unlike previous studies focusing on individual

ferroptosis regulators (such as GPX4 or SLC7A11), the present work

identified a novel seven-gene risk signature that predicts GC

prognosis (53–55). This multi-gene approach provides a

more comprehensive framework for targeting ferroptosis in

heterogeneous tumors. The present results align with previous

report linking ferroptosis resistance to GC metastasis but

identified RBMS1 as a dual regulator of iron metabolism and EMT

(44,56).

In the current optimized Cox hazard model, the

log-rank P-value of OS was 2.55×10−14. To the best of

our knowledge, this value is the lowest among all currently

available models. Previous studies have established prognostic

models with log-rank P-values (high- vs. low-risk) ranging from

0.0001 to 0.0100 (1,57–61).

Moreover, the AUC of the ROC curve for the prediction of PFS was

>0.8, which is markedly improved compared with that reported in

the majority of previous studies (1,61,62). A

previous study explored novel immune ferroptosis-related genes

associated with clinical and prognostic features in patients with

GC (38). However, performance of

the model was not satisfactory (P=0.046 in the test cohort; the

best AUC value was ~0.7). In summary, the present prognostic model

constructed using ferroptosis genes is one of the best performing

models for GC prognosis.

On the basis of the coefficients of the prognostic

model, the interaction networks and association with tumor

immunity, it was found that NOX5, NOX4 and GABARAPL2 served more

prominent cancer-promoting roles compared with the other key genes.

NOX5 is a strong reactive oxygen species producer. It mediates the

crosstalk between tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts by

regulating the cytokine network (63). To the best of our knowledge, only

one study has investigated the genetic alteration and mRNA

expression of the NOX family in patients with GC (63), the aforementioned bioinformatics

study demonstrated decreased NOX5 expression in GC; to the best of

our knowledge, however, no study has elucidated the role of NOX5 in

GC. The present study highlights the prognostic and carcinogenic

role of NOX5 in GC and hence expands the range of GC targets. As

shown in a previous study (46),

NOX4 expression was also increased in GC compared with normal

tissues, which is in line with the present findings. Additionally,

the aforementioned study reported NOX4 is a potential prognostic

marker in GC and implicate that the use of NOX inhibitor targeting

NOX4 and DUOX1 may be an effective strategy for GC therapy

(46). NOX4 was a valid biomarker

for STAD (64). Similarly, a

previous study involving LASSO analysis used NOX4 for the

construction of a hypoxia-related gene prognostic model for GC

(65). However, none of the

aforementioned studies revealed the cancer-promoting mechanism of

NOX4. By contrast, the present study suggested that NOX4 and NOX5

(two important ferroptosis drivers) may drive GC progression by

promoting ferroptosis.

GABARAPL2 is a mitophagy-related gene (66–69)

and a ferroptosis driver. A previous study established and

validated a nomogram model based on GABARAPL2 and cell division

cycle 37, HSP90 cochaperone (CDC37) (49). GABARAPL2 and CDC37 display different

immune infiltration states and are prognostic biomarkers and

candidate therapeutic targets of GC (49). Another study revealed different

expression patterns of GABARAPL2 in GC and normal tissues, but it

was not a powerful independent prognostic factor (70). The present study revealed that

ferroptosis drivers, but not inhibitors, serve primarily

pro-carcinogenic roles, suggesting that the inhibition of

ferroptosis is a potential strategy to combat GC progression.

The present study identified miRNAs

(hsa-miR-6795-5p, hsa-miR-6758-5p, hsa-miR-501-5p, hsa-miR-505-5p

and hsa-miR-484) with potential therapeutic implications. A

previous study revealed that the upregulation of miR-501-5p

activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and enhances the stem

cell-like phenotype in GC (71),

and another study revealed that miRNA-501-5p promotes cell

proliferation and migration in GC by downregulating

lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (72). The aforementioned conclusions

contradict that of the present study; thus, whether hsa-miR-501-5p

exerts an anticancer effect remains to be determined. The

expression of miR-484 is downregulated in GC (73). In 2020, an in vitro study

revealed that miR-484 suppresses the proliferation, migration and

invasion, and induces the apoptosis of GC cells (74). Moreover, downregulation of miR-484

is associated with poor prognosis and GC progression (75). The aforementioned studies are

consistent with the present hypothesis that miR-484 may serve as a

potential molecular agent against GC progression. The present study

experimentally validated miR-484 and miR-501-5p due to their

established roles in ferroptosis-associated processes. miR-484 was

downregulated in GC tissues. Through its seed sequence 5′-UCAGG-3′,

miR-484 targets the 3′-UTRs of NOX4, TF, and RBMS1, inducing mRNA

degradation and reducing target protein expression by 60–70%.

Consequently, it blocks NADPH oxidase activity, iron ion uptake,

and reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition, synergistically

inhibiting ferroptosis, immune evasion, and metastasis (44,76).

Regarding miR-501-5p, experimental inhibition of this miRNA

unexpectedly reduced the expression of target genes AKR1C2 and

GABARAPL2. This paradoxical effect may stem from: (1) indirect regulatory networks (e.g.,

miR-501-5p suppresses tumor suppressors LPAR1; inhibiting

miR-501-5p elevates LPAR1 expression, indirectly reducing AKR1C2)

(72); (2) ceRNA competitive mechanisms (77); and (3) miRNA concentration-dependent effects.

These findings reveal its dual role in directly targeting oncogenes

while indirectly maintaining oncogenic networks. The other miRNAs

(miR-6795-5p, miR-6758-5p and hsa-miR-505-5p) represent novel

candidates with potential therapeutic value but require functional

characterization in future.

A panel of drugs (5Z-7-oxozeaenol, selumetinib,

RDEA119, AZ628, dabrafenib and trametinib) for the treatment of

STAD was investigated in the present study. 5Z-7-oxozeaenol is a

selective TGFβ-activated kinase 1 inhibitor (78). A previous study reported that

5Z-7-oxozeaenol increases the expression levels of cytosolic

cytochrome c and cleaved caspase 3 and apoptosis rate in GC

cells (79). Despite the different

mechanisms, the results are consistent with the conclusions of the

present study, and support the potential of 5Z-7-oxozeaenol as a

candidate anti-GC drug. The MEK inhibitor selumetinib is a potent,

orally active inhibitor of the MAPK/ERK pathway, and in

vitro experiments suggested that selumetinib should be

validated in prospective clinical trials (80). Moreover, the VIKTORY trial was

designed to classify patients with metastatic GC on the basis of

clinical sequencing and focused on eight biomarker groups, among

which, selumetinib was evaluated with or without chemotherapy

(81). However, the effectiveness

of selumetinib in the clinic is not yet clear. Similar to

selumetinib, RDEA119 is a MEK inhibitor that exhibits an anticancer

effect on multiple cancer cells, including GC cells (82). The potential for improving tumor

microenvironment of AZ628 has been proposed in another

bioinformatics study, but no validation was performed (83). Dabrafenib is a BRAF inhibitor and

its action on GC may increase susceptibility to immunotherapy

(84). Recently, the US Food and

Drug Administration accelerated the approval of darafenib in

combination with trametinib for the treatment of unresectable or

metastatic solid tumors (including GC) with the BRAFV600E mutation,

and this combination has been recommended in the latest National

Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for GC (85). Trametinib is a MEK inhibitor used to

inhibit the growth of GC (86–88).

In addition, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib may be

promising in the clinical treatment of GC.

The present study has limitations. Regarding

bioinformatics methods, LASSO regression performance is greatly

influenced by data quality. The present study uses three databases,

and the sample size was limited. In the future, it is necessary to

expand the database samples and optimize the data quality to obtain

more accurate results. LASSO regression selects the most important

variables, but the explanatory power of these variables may be low.

Therefore, it may be necessary to combine other analytical methods

to improve the explanatory power of LASSO regression in the future.

Although numerous key genes, miRNAs and inhibitors have been

screened, the interaction between them and the regulatory mechanism

of iron-mediated cell death remains unclear. The present results

should be verified through basic experiments and clinical research.

While weighted correlation network analysis and LASSO regression

robustly identify gene signatures, these approaches may overlook

non-linear gene interactions. Additionally, bulk RNA-sequencing

data cannot resolve cell type-specific ferroptosis mechanisms,

necessitating future single-cell analyses. Prioritized targets

(such as NOX4) should be validated using NOX4-knockout AGS cell

lines and patient-derived xenograft models treated with ferroptosis

inducers erastin/artesunate, alongside RNA interference-mediated

gene silencing.

In summary, 14 key ferroptosis-related genes,

including seven carcinogenic genes, that promoted STAD development

and are risk factors for survival were identified in the present

study. For OS and PFS prediction, two models were constructed, and

five miRNAs (hsa-miR-6795-5p, hsa-miR-6758-5p, hsa-miR-501-5p,

hsa-miR-505-5p and hsa-miR-484) with potential therapeutic value

for STAD were identified through the targeting of carcinogenic

genes. The present results revealed that (5Z)-7-oxozeaenol,

selumetinib, RDEA119, AZ628, dabrafenib and trametinib may be

effective in treating STAD.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Kunming Medical University

First Affiliated Hospital Science and Technology Talent Training

Program (Leading Talent; grant no. L-2019024), Sub-project of

Yunnan Clinical Medical Research Center (grant no. 202102AA100062),

Scientific Research Fund Project of Yunnan Education Department

(grant no. 2024Y223), Kunming Medical University graduate Student

Innovation Fund (grant no. 2024S045), Yunnan Fundamental Research

Projects (grant no. 202401AT070170) and First-Class Discipline Team

of Kunming Medical University (grant no. 2024XKTDYS02).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HW conceived and designed the study, analyzed data

and wrote the manuscript. HC conceived and designed the study,

interpreted data and edited the manuscript. JJL and DZ performed

experiments and analyzed data. DW analyzed data. MSH and MWL

interpreted data and constructed figures. SYH interpreted data. LQM

conceived and designed the study. HW and LQM confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics

committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical

University (approval no. 2024 lunshen L No.78). The procedures used

in the present study adhere to the principles of CFDA/GCP and the

Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided voluntary

written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chang J, Wu H, Wu J, Liu M, Zhang W, Hu Y,

Zhang X, Xu J, Li L, Yu P and Zhu J: Constructing a novel

mitochondrial-related gene signature for evaluating the tumor

immune microenvironment and predicting survival in stomach

adenocarcinoma. J Transl Med. 21:1912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jin W, Ou K, Li Y, Liu W and Zhao M:

Metabolism-related long noncoding RNA in the stomach cancer

associated with 11 AMMLs predictive nomograms for OS in STAD. Front

Genet. 14:11271322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang J, Liu D, Wang Q and Xie Y:

Identification of basement membrane-related signatures in gastric

cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 13:18442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wu B, Fu L, Guo X, Hu H, Li Y, Shi Y,

Zhang Y, Han S, Lv C and Tian Y: Multiomics profiling and digital

image analysis reveal the potential prognostic and

immunotherapeutic properties of CD93 in stomach adenocarcinoma.

Front Immunol. 14:9848162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhao W, Lin J, Cheng S, Li H, Shu Y and Xu

C: Comprehensive analysis of COMMD10 as a novel prognostic

biomarker for gastric cancer. PeerJ. 11:e146452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhao Z, Mak TK, Shi Y, Li K, Huo M and

Zhang C: Integrative analysis of cancer-associated fibroblast

signature in gastric cancer. Heliyon. 9:e192172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ajani JA, Lee J, Sano T, Janjigian YY, Fan

D and Song S: Gastric adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

3:170362017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Takahari D: Second-line chemotherapy for

patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 20:395–406.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Johnston FM and Beckman M: Updates on

management of gastric cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 21:672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hirschhorn T and Stockwell BR: The

development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med.

133:130–143. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gao W, Wang X, Zhou Y, Wang X and Yu Y:

Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor

immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liang D, Minikes AM and Jiang X:

Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular

signaling. Mol Cell. 82:2215–2227. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu J, Kang R and Tang D: Signaling

pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J.

289:7038–7050. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu P, Wang W, Li Z, Li Y, Yu X, Tu J and

Zhang Z: Ferroptosis: A new regulatory mechanism in osteoporosis.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:26344312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yang Y, Wang Y, Guo L, Gao W, Tang TL and

Yan M: Interaction between macrophages and ferroptosis. Cell Death

Dis. 13:3552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhao L, Zhou X, Xie F and Zhang L, Yan H,

Huang J, Zhang C, Zhou F, Chen J and Zhang L: Ferroptosis in cancer

and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun (Lond). 42:88–116. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gong C, Ji Q, Wu M, Tu Z, Lei K, Luo M,

Liu J, Lin L, Li K, Li J, et al: Ferroptosis in tumor immunity and

therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 26:5565–5579. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li J, Liu J, Xu Y, Wu R, Chen X, Song X,

Zeh H, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Wang X and Tang D: Tumor heterogeneity

in autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Autophagy. 17:3361–3374. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liao P, Wang W, Wang W, Kryczek I, Li X,

Bian Y, Sell A, Wei S, Grove S, Johnson JK, et al: CD8(+) T cells

and fatty acids orchestrate tumor ferroptosis and immunity via

ACSL4. Cancer Cell. 40:365–378.e6. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Luo T, Wang Y and Wang J: Ferroptosis

assassinates tumor. J Nanobiotechnology. 20:4672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fu D, Wang C, Yu L and Yu R: Induction of

ferroptosis by ATF3 elevation alleviates cisplatin resistance in

gastric cancer by restraining Nrf2/Keap1/xCT signaling. Cell Mol

Biol Lett. 26:262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gu R, Xia Y, Li P, Zou D, Lu K, Ren L,

Zhang H and Sun Z: Ferroptosis and its Role in Gastric Cancer.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8603442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Huang G, Xiang Z, Wu H, He Q, Dou R, Lin

Z, Yang C, Huang S, Song J, Di Z, et al: The lncRNA

BDNF-AS/WDR5/FBXW7 axis mediates ferroptosis in gastric cancer

peritoneal metastasis by regulating VDAC3 ubiquitination. Int J

Biol Sci. 18:1415–1433. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li D, Wang Y, Dong C, Chen T, Dong A, Ren

J, Li W, Shu G, Yang J, Shen W, et al: CST1 inhibits ferroptosis

and promotes gastric cancer metastasis by regulating GPX4 protein

stability via OTUB1. Oncogene. 42:83–98. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lin Z, Song J, Gao Y, Huang S, Dou R,

Zhong P, Huang G, Han L, Zheng J, Zhang X, et al: Hypoxia-induced

HIF-1α/lncRNA-PMAN inhibits ferroptosis by promoting the

cytoplasmic translocation of ELAVL1 in peritoneal dissemination

from gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 52:1023122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu Y, Song Z, Liu Y, Ma X, Wang W, Ke Y,

Xu Y, Yu D and Liu H: Identification of ferroptosis as a novel

mechanism for antitumor activity of natural product derivative a2

in gastric cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:1513–1525. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ma M, Kong P, Huang Y, Wang J, Liu X, Hu

Y, Chen X, Du C and Yang H: Activation of MAT2A-ACSL3 pathway

protects cells from ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Free Radic Biol

Med. 181:288–299. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ouyang S, Li H, Lou L, Huang Q, Zhang Z,

Mo J, Li M, Lu J, Zhu K, Chu Y, et al: Inhibition of

STAT3-ferroptosis negative regulatory axis suppresses tumor growth

and alleviates chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Redox Biol.

52:1023172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Song S, Wen F, Gu S, Gu P, Huang W, Ruan

S, Chen X, Zhou J, Li Y, Liu J and Shu P: Network pharmacology

study and experimental validation of Yiqi Huayu decoction inducing

ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 12:8200592022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang Y, Zheng L, Shang W, Yang Z, Li T,

Liu F, Shao W, Lv L, Chai L, Qu L, et al: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling confers ferroptosis resistance by targeting GPX4 in

gastric cancer. Cell Death Differ. 29:2190–2202. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xu C, Liu Z and Xiao J: Ferroptosis: A

double-edged sword in gastrointestinal disease. Int J Mol Sci.

22:124032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Xu X and Li Y, Wu Y, Wang M, Lu Y, Fang Z,

Wang H and Li Y: Increased ATF2 expression predicts poor prognosis

and inhibits sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Redox

Biol. 59:1025642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yang H, Hu Y, Weng M, Liu X, Wan P, Hu Y,

Ma M, Zhang Y, Xia H and Lv K: Hypoxia inducible lncRNA-CBSLR

modulates ferroptosis through m6A-YTHDF2-dependent modulation of

CBS in gastric cancer. J Adv Res. 37:91–106. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yang Z, Zou S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhang P,

Xiao L, Xie Y, Meng M, Feng J, Kang L, et al: ACTL6A protects

gastric cancer cells against ferroptosis through induction of

glutathione synthesis. Nat Commun. 14:41932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang H, Wang M, He Y, Deng T, Liu R, Wang

W, Zhu K, Bai M, Ning T, Yang H, et al: Chemotoxicity-induced

exosomal lncFERO regulates ferroptosis and stemness in gastric

cancer stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 12:11162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee JY, Nam M, Son HY, Hyun K, Jang SY,

Kim JW, Kim MW, Jung Y, Jang E, Yoon SJ, et al: Polyunsaturated

fatty acid biosynthesis pathway determines ferroptosis sensitivity

in gastric cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:32433–32442. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xiao C, Dong T, Yang L, Jin L, Lin W,

Zhang F, Han Y and Huang Z: Identification of novel immune

ferropotosis-related genes associated with clinical and prognostic

features in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 12:9043042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Deng H, Lin Y, Gan F, Li B, Mou Z, Qin X,

He X and Meng Y: Prognostic model and immune infiltration of

ferroptosis subcluster-related modular genes in gastric cancer. J

Oncol. 2022:58135222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cheng X, Dai E, Wu J, Flores NM, Chu Y,

Wang R, Dang M, Xu Z, Han G, Liu Y, et al: Atlas of metastatic

gastric cancer links ferroptosis to disease progression and

immunotherapy response. Gastroenterology. 167:1345–1357. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yue Z, Yuan Y, Zhou Q, Sheng J and Xin L:

Ferroptosis and its current progress in gastric cancer. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 12:12893352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA,

Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C and Stuart JM: The cancer genome

atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 45:1113–1120. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liu M, Li H, Zhang H, Zhou H, Jiao T, Feng

M, Na F, Sun M, Zhao M, Xue L and Xu L: RBMS1 promotes gastric

cancer metastasis through autocrine IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Cell

Death Dis. 13:2872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lodhi MS, Khan MT, Bukhari SMH, Sabir SH,

Samra ZQ, Butt H and Akram MS: Probing transferrin receptor

overexpression in gastric cancer mice models. ACS Omega.

6:29893–29904. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

You X, Ma M, Hou G, Hu Y and Shi X: Gene

expression and prognosis of NOX family members in gastric cancer.

Onco Targets Ther. 11:3065–3074. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang H, Zhan J, Zhou J, Liu L, He Y, Le

Y, Liu W, Zhou L, Liu Y and Xiang X: Identification of HCAR1 as a

ferroptosis-related biomarker of gastric cancer based on a novel

ferroptosis-related prognostic model and in vitro experiments.

Carcinogenesis. 7:bgaf0302025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Pourjamal N, Shirkoohi R, Rohani E and

Hashemi M: The expression analysis of MEST1 and GJA1 genes in

gastric cancer in association with clinicopathological

characteristics. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 18:83–91.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wang Z, Chen C, Ai J, Shu J, Ding Y, Wang

W, Gao Y, Jia Y and Qin Y: Identifying mitophagy-related genes as

prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets of gastric carcinoma

by integrated analysis of single-cell and bulk-RNA sequencing data.

Comput Biol Med. 163:1072272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Huang DH, Wang GY, Zhang JW, Li Y, Zeng XC

and Jiang N: MiR-501-5p regulates CYLD expression and promotes cell

proliferation in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol.

45:738–744. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gu Y, Wu S, Fan J, Meng Z, Gao G, Liu T,

Wang Q, Xia H, Wang X and Wu K: CYLD regulates cell ferroptosis

through Hippo/YAP signaling in prostate cancer progression. Cell

Death Dis. 15:792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Huang M, Cheng S, Li Z, Chen J, Wang C, Li

J and Zheng H: Preconditioning exercise inhibits neuron ferroptosis

and ameliorates brain ischemia damage by skeletal muscle-derived

exosomes via regulating miR-484/ACSL4 axis. Antioxid Redox Signal.

41:769–792. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhang J, Tian T, Li X, Yan Y, Zhao D, Ji

S, Ni J, Zhang J, Liu K, Qing H and Quan Z: p53 inhibits OTUD5

transcription to promote GPX4 degradation and induce ferroptosis in

gastric cancer. Clin Transl Med. 15:e702712025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lu D, Yuan L, Wang Z, Xu D, Meng F, Jia S,

Li Y, Li W and Nan Y: Dioscin induces ferroptosis to suppress the

metastasis of gastric cancer through the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis. Free

Radic Res. 59:426–441. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang H, Li C, Meng S and Kuang YT: The

LINC01094/miR-545-3p/SLC7A11 signaling axis promotes the

development of gastric cancer by regulating cell growth and

ferroptosis. Biochem Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-024-10959-3

|

|

56

|

Xu Y, Hao J, Chen Q, Qin Y, Qin H, Ren S,

Sun C, Zhu Y, Shao B, Zhang J and Wang H: Inhibition of the

RBMS1/PRNP axis improves ferroptosis resistance-mediated

oxaliplatin chemoresistance in colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog.

63:224–237. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yu R, Li Z, Zhang C, Song H, Deng M, Sun

L, Xu L, Che X, Hu X, Qu X, et al: Elevated limb-bud and heart

development (LBH) expression indicates poor prognosis and promotes

gastric cancer cell proliferation and invasion by upregulating

Integrin/FAK/Akt pathway. PeerJ. 7:e68852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Berthelet E, Pickles T, Lee KW, Liu M and

Truong PT; Prostate Cancer Outcomes Initiative, : Long-term

androgen deprivation therapy improves survival in prostate cancer

patients presenting with prostate-specific antigen levels >20

ng/ml. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 63:781–787. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Huang R, Lu TL and Zhou R: Identification

and immune landscape analysis of fatty acid metabolism genes

related subtypes of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 13:204432023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Yuan Q, Deng D, Pan C, Ren J, Wei T, Wu Z,

Zhang B, Li S, Yin P and Shang D: Integration of transcriptomics,

proteomics, and metabolomics data to reveal HER2-associated

metabolic heterogeneity in gastric cancer with response to

immunotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Front Immunol.

13:9511372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Wang X, Zhang W, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Bai X and

Xie Y: Identification of critical prognosis signature associated

with lymph node metastasis of stomach adenocarcinomas. World J Surg

Oncol. 21:612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Feng A, He L, Chen T and Xu M: A novel

cuproptosis-related lncRNA nomogram to improve the prognosis

prediction of gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 12:9579662022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chen J, Wang Y, Zhang W, Zhao D, Zhang L,

Zhang J, Fan J and Zhan Q: NOX5 mediates the crosstalk between

tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts by regulating

cytokine network. Clin Transl Med. 11:e4722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Xiao R, Wang S, Guo J, Liu S, Ding A, Wang

G, Li W, Zhang Y, Bian X, Zhao S and Qiu W: Ferroptosis-related

gene NOX4, CHAC1 and HIF1A are valid biomarkers for stomach

adenocarcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 26:1183–1193. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Guo J, Xing W, Liu W, Liu J, Zhang J and

Pang Z: Prognostic value and risk model construction of hypoxic

stress-related features in predicting gastric cancer. Am J Transl

Res. 14:8599–8610. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Chan JCY and Gorski SM: Unlocking the gate

to GABARAPL2. Biol Futur. 73:157–169. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Polletta L, Vernucci E, Carnevale I,

Arcangeli T, Rotili D, Palmerio S, Steegborn C, Nowak T,

Schutkowski M, Pellegrini L, et al: SIRT5 regulation of

ammonia-induced autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy. 11:253–270.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Scicluna K, Dewson G, Czabotar PE and

Birkinshaw RW: A new crystal form of GABARAPL2. Acta Crystallogr F

Struct Biol Commun. 77:140–147. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhang Z, Gu H, Li Q, Zheng J, Cao S, Weng

C and Jia H: GABARAPL2 is critical for growth restriction of

Toxoplasma gondii in HeLa cells treated with gamma

interferon. Infect Immun. 88:e00054–e00020. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang M, Jing J, Li H, Liu J, Yuan Y and

Sun L: The expression characteristics and prognostic roles of

autophagy-related genes in gastric cancer. PeerJ. 9:e108142021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Fan D, Ren B, Yang X, Liu J and Zhang Z:

Upregulation of miR-501-5p activates the wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway and enhances stem cell-like phenotype in gastric cancer. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 35:1772016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ma X, Feng J, Lu M, Tang W, Han J, Luo X,

Zhao Q and Yang L: microRNA-501-5p promotes cell proliferation and

migration in gastric cancer by downregulating LPAR1. J Cell

Biochem. 121:1911–1922. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zare A, Ahadi A, Larki P, Omrani MD, Zali

MR, Alamdari NM and Ghaedi H: The clinical significance of miR-335,

miR-124, miR-218 and miR-484 downregulation in gastric cancer. Mol

Biol Rep. 45:1587–1595. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Liu J and Li SM: MiR-484 suppressed

proliferation, migration, invasion and induced apoptosis of gastric

cancer by targeting CCL-18. Int J Exp Pathol. 101:203–214. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Li Y, Liu Y, Yao J, LI R and Fan X:

Downregulation of miR-484 is associated with poor prognosis and

tumor progression of gastric cancer. Diagn Pathol. 15:252020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang L and Gong W: NOX4 regulates gastric

cancer cell invasion and proliferation by increasing ferroptosis

sensitivity through regulating ROS. Int Immunopharmacol.

132:1120522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Qi X, Zhang DH, Wu N, Xiao JH, Wang X and

Ma W: ceRNA in cancer: Possible functions and clinical

implications. J Med Genet. 52:710–718. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Zhang D, Yan H, Li H, Hao S, Zhuang Z, Liu

M, Sun Q, Yang Y, Zhou M, Li K and Hang C: TGFβ-activated kinase 1

(TAK1) inhibition by 5Z-7-Oxozeaenol attenuates early brain injury

after experimental subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Biol Chem.

290:19900–19909. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Yang Y, Qiu Y, Tang M, Wu Z, Hu W and Chen

C: Expression and function of transforming growth

factor-β-activated protein kinase 1 in gastric cancer. Mol Med Rep.

16:3103–3110. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Ahn S, Brant R, Sharpe A, Dry JR, Hodgson

DR, Kilgour E, Kim K, Kim ST, Park SH, Kang WK, et al: Correlation

between MEK signature and Ras gene alteration in advanced gastric

cancer. Oncotarget. 8:107492–107499. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Lee J, Kim ST, Kim K, Lee H, Kozarewa I,

Mortimer PGS, Odegaard JI, Harrington EA, Lee J, Lee T, et al:

Tumor genomic profiling guides patients with metastatic gastric

cancer to targeted treatment: The VIKTORY umbrella trial. Cancer

Discov. 9:1388–1405. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Liu Z and Xing M: Induction of

sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) expression and radioiodine uptake in

nonthyroid cancer cells. PLoS One. 7:e317292012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Wu X, Zhou F, Cheng B, Tong G, Chen M, He

L, Li Z, Yu S, Wang S and Lin L: Immune activity score to assess

the prognosis, immunotherapy and chemotherapy response in gastric

cancer and experimental validation. PeerJ. 11:e163172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liu J, Zhang B, Zhang Y, Zhao H, Chen X,

Zhong L and Shang D: Oxidative stress and autophagy-mediated immune

patterns and tumor microenvironment infiltration characterization

in gastric cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 15:12513–12536. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Corvera

CU, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Gerdes H, Gibson MK, Grierson P,

et al: Gastric cancer, version 2.2025, NCCN clinical practice

guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 23:169–191. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Dai C, Shen L, Jin W, Lv B, Liu P, Wang X,

Yin Y, Fu Y, Liang L, Ma Z, et al: Physapubescin B enhances the

sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to trametinib by inhibiting the

STAT3 signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 408:1152732020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Liu H, Yao Y, Zhang J and Li J: MEK

inhibition overcomes everolimus resistance in gastric cancer.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 85:1079–1087. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Wang Z, Chen Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Zhao X,

Zhou H, Lu X, Zhao L, Yuan Q, Shi Y, et al: Tegaserod maleate

suppresses the growth of gastric cancer in vivo and in vitro by

targeting MEK1/2. Cancers (Basel). 14:35922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|