Introduction

Sarcoma is frequently misdiagnosed in ~30% of cases

due to its challenging morphological features, which can cause

delays in receiving appropriate treatment (1). Liposarcoma (LPS) is one of the most

common types of soft-tissue sarcoma (STS), accounting for 15–20% of

all instances (2,3). LPS tumors are characterized by notable

clinical and pathological diversity, which complicate diagnosis and

treatment strategies.

The classification of LPS is based on

histopathological analysis, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and

molecular profiling, which categorizes them into four distinct

subtypes, namely, well-differentiated LPS (WDL), dedifferentiated

LPS (DDL), myxoid LPS (ML) and pleomorphic LPS (PL) (3). Each subtype has unique morphological

and molecular characteristics that affect disease progression and

treatment responsiveness.

Challenges in aligning morphological findings with

underlying molecular mechanisms persist despite advancements in

understanding LPS tumors. Key genetic changes, such as MDM2

proto-oncogene (MDM2) and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4)

amplifications, have been noted in the well-differentiated and

dedifferentiated subtypes (4).

However, the role of genetic changes in disease variability and

treatment resistance is unclear. Additionally, the interactions of

molecular pathways in more aggressive subtypes, namely, myxoid and

pleomorphic, raise key questions that could improve prognostic

accuracy and treatment efficacy (3–5).

Systemic therapies that target specific molecular

pathways (MDM2, CDK4) demonstrate potential in overcoming the

limitations of traditional treatments (surgical), especially for

advanced and high-grade LPS (3–5). The

histopathological images included in the present review were

obtained from Dr Sardjito General Hospital (Yogyakarta, Indonesia).

The selected representative slides, collected between 2021 and

2024, were chosen due to the rarity of the cases and their

relevance to the discussion. The histopathological images were used

solely for educational and illustrative purposes, without the

inclusion of any identifiable patient data. The present review aims

to provide a detailed overview of the morphological and molecular

features of LPS, emphasizing how these factors may contribute to

improved diagnostic precision, prognostic assessments, innovative

therapeutic strategies and novel approaches for molecular targeting

in the future.

WDL

WDL is the most common LPS subtype, accounting for

31–33% of all liposarcomas (1,5). WDL

is typically found in the deep soft tissues of the limbs,

especially the thigh and retroperitoneum, but can also appear in

the chest wall, head and neck (5).

WDL grows gradually but is often asymptomatic. However,

retroperitoneal tumors may cause symptoms such as abdominal pain

and bloating due to organ compression. Larger tumors may appear as

bulges or swelling. WDL develops slowly and has a low risk of

metastasis, but local recurrence is common, complicating complete

surgical resection (1,5). WDL primarily affects adults aged 50–60

years (5). Imaging studies (MRI or

CT) demonstrate WDL as a fatty mass with thickened septa or nodular

elements that could indicate malignancy. The diagnosis involves

imaging, biopsy and molecular testing for MDM2 or CDK4

amplification (3).

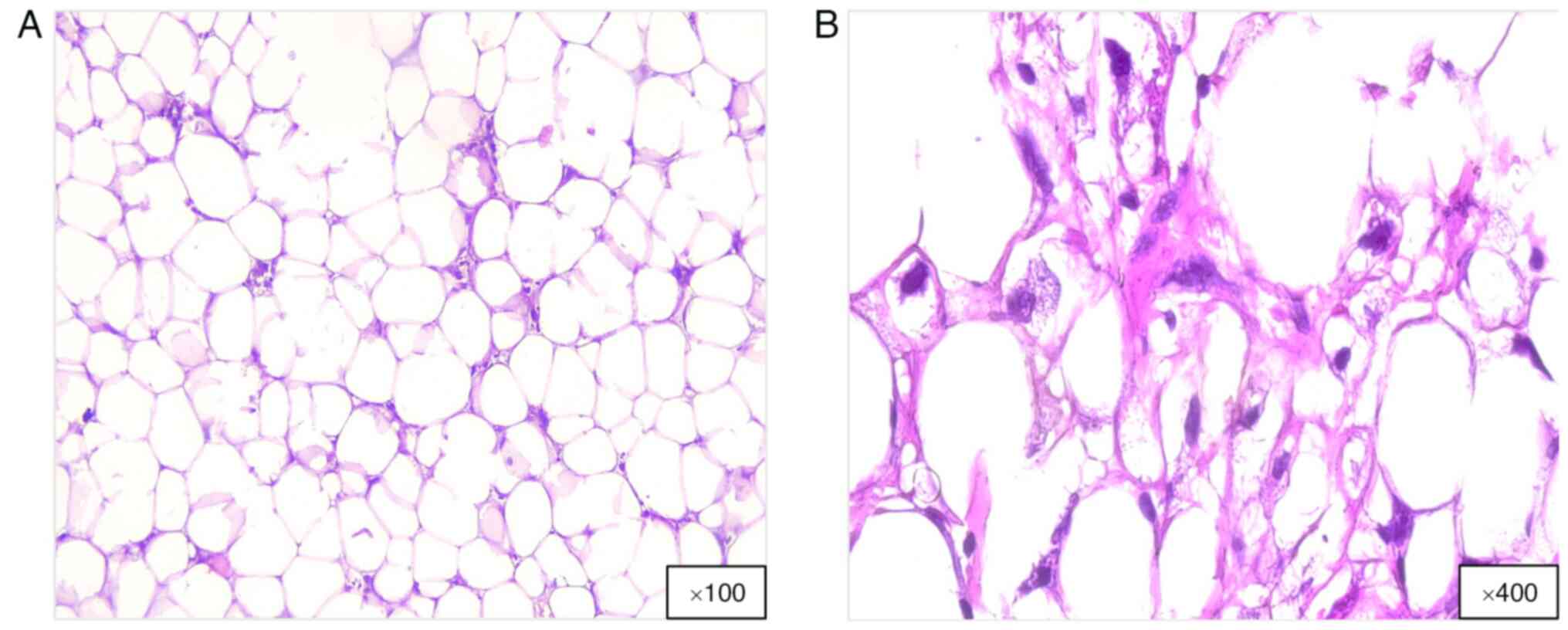

Histologically, WDL consists of mature adipocytes,

atypical stromal cells and a few lipoblasts (Fig. 1). Moreover, MDM2 and CDK4 oncogenes,

which facilitate the differentiation of WDL from benign lipomas

through IHC or molecular testing, are often upregulated (4,6). WDL

mainly arises from genetic alterations, especially amplification of

the 12q13-15 region. This abnormality causes supernumerary rings or

giant rod chromosomes, which are characteristic of WDL (4,6).

Amplified genes, such as MDM2 and CDK4, are key in WDL and DDL.

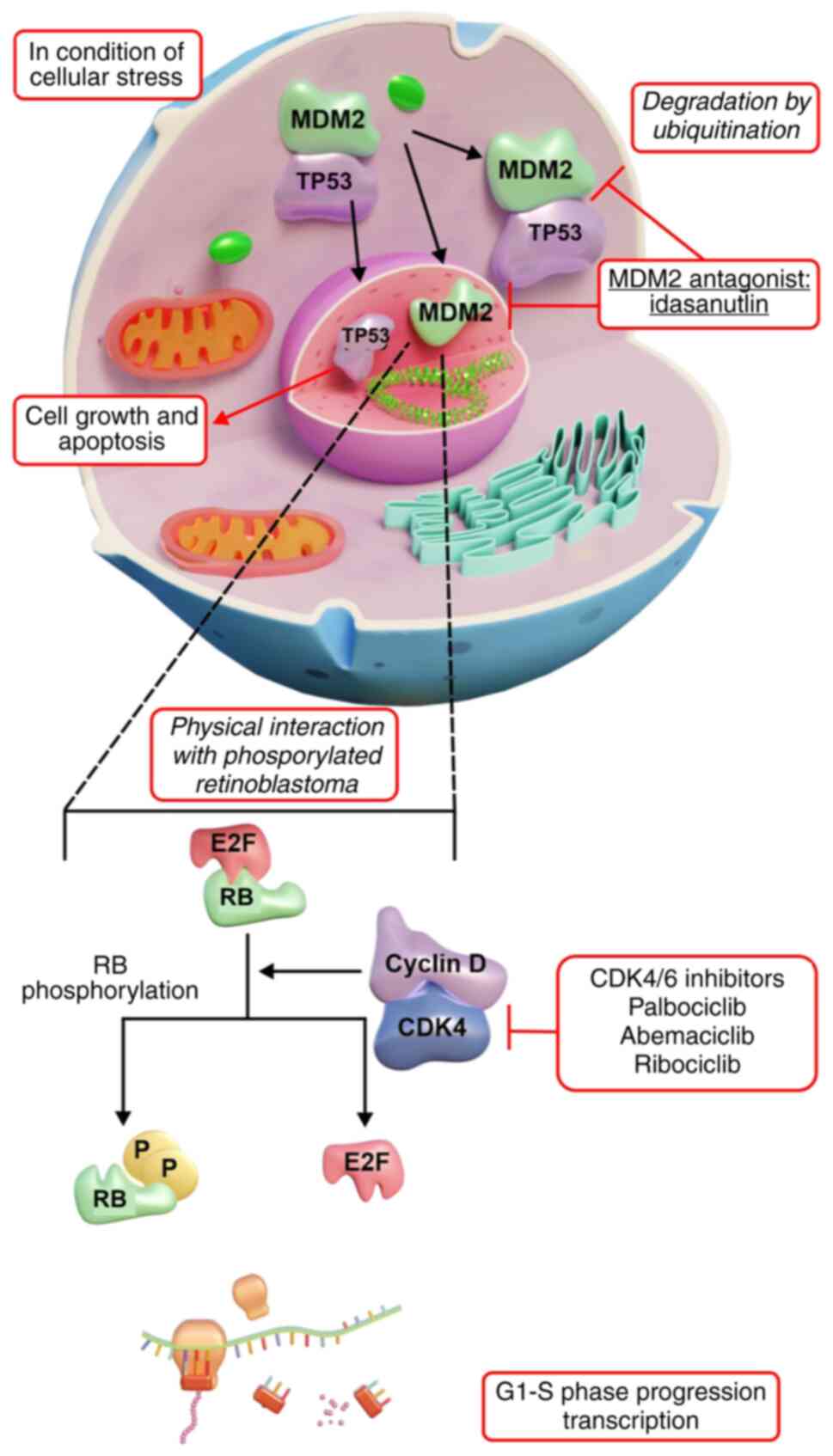

CDK4 activates D-type cyclins for hyperphosphorylation of

retinoblastoma protein (RB) (3,5,7).

Phosphorylated RB does not suppress E2F transcription factor 1,

which is a key transcription factor for the G1 to S

phase transition, resulting in unregulated cell proliferation. CDK4

is amplified in ≤90% of LPS cases, causing persistent RB

inactivation and tumor cells to bypass the G1/S

checkpoint, facilitating tumor growth (7).

In most WDL and DDL cases, the MDM2-p53 pathway is

altered due to MDM2 gene amplification (3,5,8). MDM2,

an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, inhibits p53, which is a key tumor

suppressor. MDM2 typically promotes p53 degradation, keeping its

levels low. However, stress phosphorylates p53, stabilizing it to

regulate genomic stability and apoptosis (3,5,8). In

WDL, increased MDM2 expression levels cause rapid p53 degradation,

neutralizing its tumor-suppressive effects and promoting

uncontrolled growth. This dysregulation emphasizes the malignant

potential of WDL and identifies CDK4 and MDM2 as vital therapeutic

targets (8).

The main treatment for WDL is surgery aimed at

complete excision with clear margins (9). Recurrence rates depend on the tumor

size and location, with retroperitoneal tumors having a higher

recurrence compares with the limbs, retroperitoneum, paratesticular

region, mediastinum and head and neck region (8,9).

Radiation and chemotherapy are usually ineffective for WDL

(9). The prognosis for extremity

WDL is generally favorable with 74% overall survival rates;

however, retroperitoneal WDL has a greater risk of progressing to

more aggressive DDL (9).

WDL often exhibits an increase in the MDM2 oncogene,

which inhibits p53, positioning MDM2 as a notable therapeutic

target. For instance, idasanutlin, a small-molecule MDM2

antagonist, has demonstrated potential in preclinical and early

clinical studies (3,8,9).

Furthermore, CDK4 expression, often elevated in WDL, is key in

cell-cycle regulation. Currently, palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor,

is under study for its efficacy in tumor management (3,8,9).

Therapeutic strategies that target and disrupt the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway have proven to be effective in LPS. Everolimus, an mTOR

inhibitor, has been explored for tumor growth inhibition (10). Anti-angiogenic agents have been

investigated in LPS due to a dependence on blood supply. Pazopanib,

a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blocks VEGFR and related

pathways. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) such as pembrolizumab

[anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)] were evaluated;

however, their efficacy in WDL remains to be elucidated (5). Previous studies have explored

epigenetic modulation with therapeutic agents such as histone

deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (8).

Vorinostat has demonstrated potential in the treatment of other

sarcoma subtypes, such as synovial sarcoma and chondrosarcoma, it

is undergoing clinical investigations for its efficacy in LPS

(3,5,9).

LPS presents treatment challenges due to the varying

immune microenvironments in each subtype, which affects prognosis

and therapy response. DDL exhibits higher tumor-infiltrating

lymphocyte (TIL) levels compared with WDL and ML, which is

associated with improved overall survival (OS) and progression-free

survival (PFS), emphasizing the potential of immunotherapy

(11,12). DDL is key to sarcoma immune classes

C, D and E, with sarcoma immune class E demonstrating the highest

immune reactivity characterized by tertiary lymphoid structures

(TLSs), which contain B and CD8+ T cells that enhance

antitumor immunity. Nonetheless, the tumor microenvironment of DDL

remains immunosuppressive due to M2-like macrophages that impede

antitumor responses. Conversely, ML contains fewer TILs compared

with DDL, which makes ML less suitable for immunotherapy (11). Immunotherapy notably improves LPS,

particularly in immune-active subtypes such as DDL. PD-1 and

programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression levels, which regulate

immune evasion, vary across LPS subtypes and influence responses to

ICIs. Previous studies have indicated that 100% of DDL cases have

PD-1-positive lymphocyte infiltration, whereas only 10% of ML cases

have PD-1-positive lymphocyte infiltration, demonstrating the

differing immune checkpoint activity in LPS (11,13).

Additionally, the presence of TLSs in retroperitoneal LPS is

associated with greater immune infiltration, indicating that tumors

rich in TLSs may demonstrate an improved response to ICIs. Current

clinical trials on ICIs, such as anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab

(NCT02301039) and anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab (NCT03474094),

have yielded mixed outcomes across STS subtypes, especially in WDL

(11). Further research is

warranted to enhance immunotherapies, identify biomarkers and

optimize patient selection for improved treatment outcomes in

patients with WDL (11).

WDL has a 5-year OS rate of 75–98%, depending on the

tumor location, with extremity tumors exhibiting the highest OS

(14). Treatment of WDL with more

aggressive methods, such as surgery and radiotherapy (RT), resulted

in lower local recurrence rates compared with surgery alone,

although it did not markedly alter disease-specific survival (DSS)

(15). The DSS for patients with

WDL post-surgery is ~98.3% (16).

In a previous study, treatment of WDL with radiation alone

demonstrated a higher mortality rate compared with WDL treated with

surgery alone, surgery combined with radiation or no treatment at

all (17).

DDL

DDL often presents as a growing, initially painless

mass (4). As it enlarges, it can

cause discomfort by pressing on nearby structures. DDL typically

originates from a well-differentiated subtype (4). Depending on the location of the tumor,

symptoms include abdominal pain, bloating, bowel obstruction and

urinary retention. DDL is typically diagnosed at a larger size

owing to deep anatomical positioning (4,18). In

the limbs, DDL may appear as a solid mass causing functional issues

or localized pain. In trunk soft tissues, DDL can present as a

palpable, non-tender mass (18).

DDL exhibits rapid growth and higher recurrence rate compared with

WDL, and can spread to the lungs or liver. Advanced stages may

cause pain, weight loss and functional impairments. Furthermore,

DDL commonly affects adults aged 50–70 years and is slightly more

prevalent in men (18). Several

cases of DDL have arisen from dedifferentiating previously

diagnosed or undiagnosed WDL (4,18). CT

or MRI indicate a heterogeneous mass with non-lipomatous areas, and

calcifications or necrotic zones may indicate dedifferentiation

(4,18).

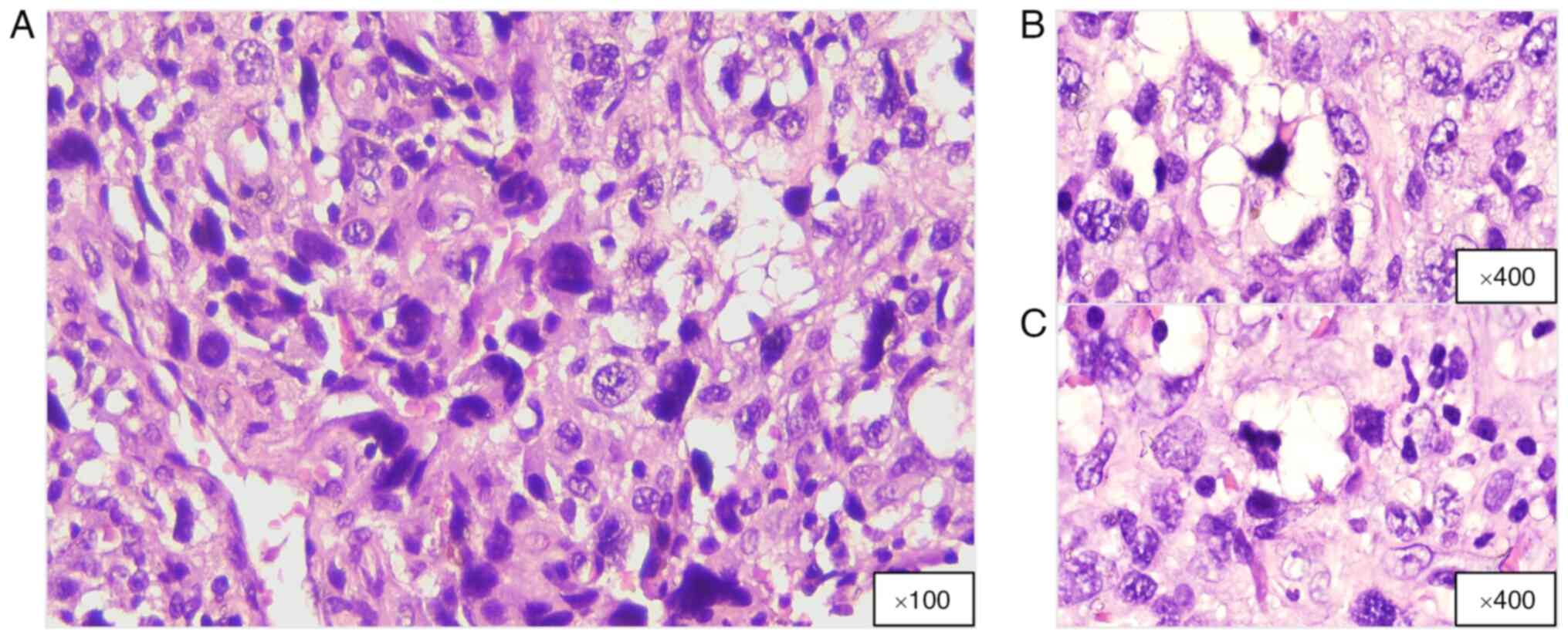

DDL has unique histopathological characteristics

that mark its evolution from a WDL; it includes differentiated

adipose tissue combined with fibrous elements, and dedifferentiated

areas may appear grayish-white and denser compared with fatty

regions. Larger tumors may exhibit necrosis or hemorrhage, whereas

tumors in the retroperitoneum often appear as large, multinodular

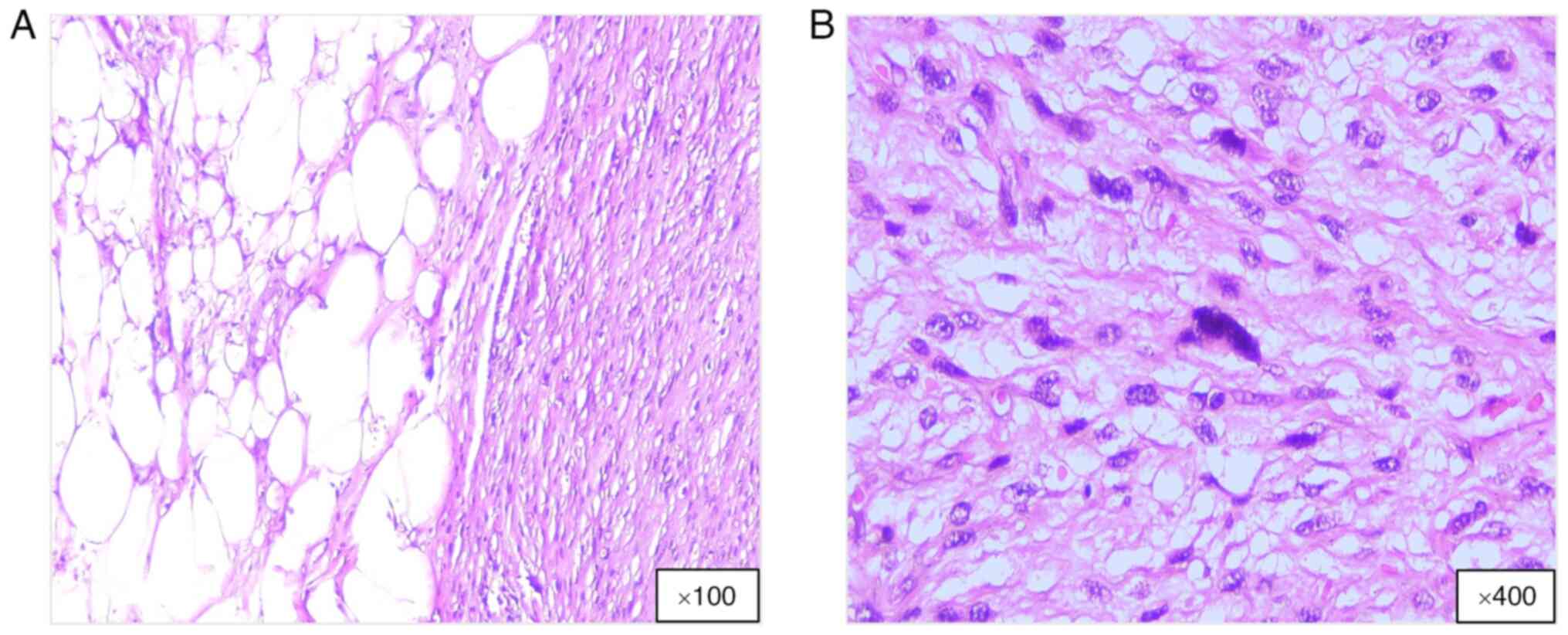

masses (3,4). Microscopic analysis demonstrates a

biphasic structure: A well-differentiated component with mature

adipocytes and atypical stromal cells with hyperchromatic nuclei,

and a dedifferentiated portion containing high-grade sarcomatous

segments with spindle cells, hyperchromasia, mitotic figures and

pleomorphism, resembling undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas or

other high-grade sarcomas, namely, fibrosarcoma or myxofibrosarcoma

(Fig. 2). In the dedifferentiated

area, atypical spindle cells are arranged in a fascicular pattern

with few lipoblasts. DDLs exhibit fibrous and myxoid traits and may

contain fibrous, myxoid or cartilaginous materials, with rare cases

demonstrating heterologous differentiation, including osseous or

rhabdomyoblastic changes (4,18).

IHC is key for the identification of diagnostic

markers. MDM2 amplification and upregulation can be detected by IHC

or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Moreover, CDK4

exhibits amplification and upregulation, which is beneficial in

distinguishing DDL from other sarcomas. Other markers, such as

protein S100, indicate adipocytic differentiation under certain

conditions (4). Previous genetic

studies have reported amplification in the 12q13-15 region,

particularly MDM2 and CDK4 oncogenes (3,5,8).

Prognostic features demonstrate that increased mitotic activity in

dedifferentiated areas is associated with aggressive behavior and

worse outcomes. Necrosis often manifests a higher tumor grade and

metastasis risk (4). Previous

molecular studies have indicated that ~90% of WDL/DDL cases have

MDM2 and CDK4 amplifications as primary oncogenic drivers (3,4).

However, DDL has a more aggressive molecular profile compared with

WDL, which is attributed to greater genomic complexity and

instability (19). Furthermore, WDL

is primarily defined by 12q13-15 region amplification, whereas DDL

displays additional chromosomal aberrations, gene fusions and

rearrangements, which contribute to the increased malignancy of DDL

(19). A key feature that

distinguishes DDL from WDL is its extensive genomic instability,

which includes 11q23 loss, 6q23 or 1q32 amplification and gene

fusions such as C15orf7::CBX3, CTDSP1::DNM3OS and CTDSP2::DNM3OS.

By contrast, MDM2-CDK4 amplification remains as the primary

oncogenic alteration of WDL (20).

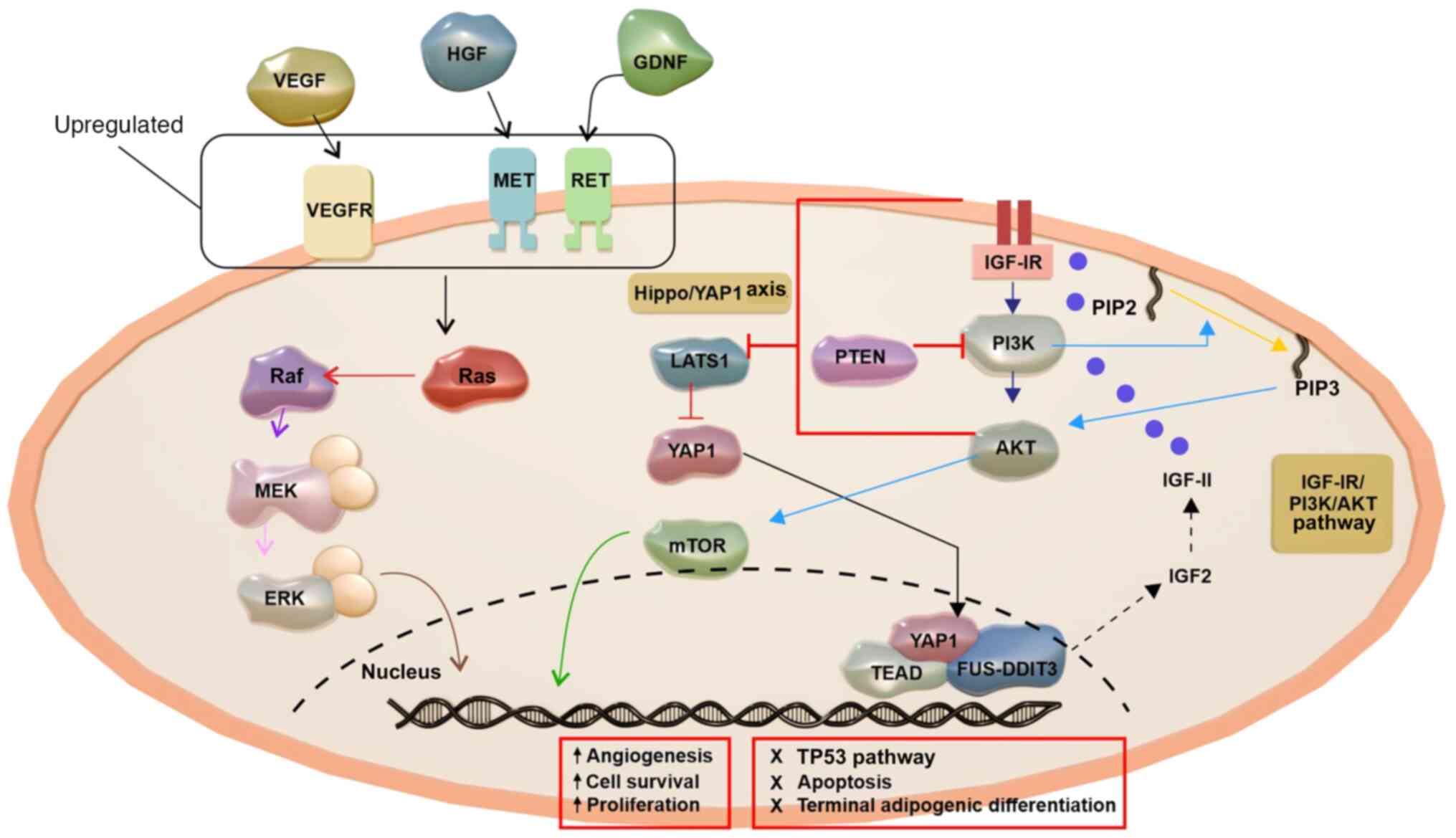

DDL is defined by upregulated pathways for cell

proliferation and survival, particularly PI3K/AKT/mTOR and DNA

damage response, which are more pronounced in DDL compared with

those in WDL (21). The

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in DDL promotes tumor growth and apoptosis

resistance. Conversely, WDL relies on MDM2 and CDK4 for cell cycle

dysregulation, which causes RB hyperphosphorylation and p53

suppression (Fig. 3). Additionally,

DDL demonstrates more disruptions in cell-cycle regulation,

especially at the G2/M checkpoint and E2F target genes,

which lead to faster tumor cell proliferation (21). Aurora A kinase is upregulated in

retroperitoneal DDL and markedly contributes to metastasis and

recurrence, which is less common in WDL (22). A notable difference is the higher

somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) in DDL. A previous study

has linked specific SCNA clusters, such as 12q15 amplification, to

a poor prognosis and reduced PFS (23). SCNAs can appear in WDL; however,

they lack the same prognostic significance as in DDL (23). Therefore, although both WDL and DDL

exhibit MDM2 and CDK4 amplification, DDL has greater genomic

complexity, additional activated oncogenic pathways and enhanced

proliferation, which marks DDL as a more aggressive LPS subtype.

Understanding these molecular distinctions is key in the

development of targeted therapies to potentially improve treatment

outcomes and the survival of patients in the future.

The treatment of DDL focuses on local tumor control,

the prevention of recurrence and the management of systemic

disease. The aggressive nature and high recurrence rate of DDL

presents notable treatment challenges. Surgical treatments involve

wide local excision for complete resection and negative margins

(5). However, the achievement of

clear margins in retroperitoneal DDL is difficult due to the

proximity of vital organs, which increases the recurrence risk.

Complex cases may require a multidisciplinary approach. Recurrence

often needs repeat surgeries, especially for retroperitoneal

tumors. Radiation therapy can serve as an adjuvant or neoadjuvant

treatment, which potentially reduces tumor size and improves

resectability (5,24). Although effective for local control,

radiation has a limited impact on distant metastases (5). Systemic therapies, including

chemotherapy, have limited effectiveness against DDL, with standard

drugs, such as doxorubicin and ifosfamide, typically used for

unresectable or metastatic cases. Novel agents, including

trabectedin and eribulin, demonstrate potential in the treatment of

advanced stages (5,24). Targeted therapies, for example, MDM2

inhibitors (idasanutlin), are being clinically evaluated (8). CDK4 inhibitors (for example,

palbociclib) may reduce tumor growth in MDM2/CDK4-amplified tumors.

Studies of alternative pathways continue for effective targeted

treatments (5,24). Palliative care aims to enhance

quality of life through pain management and support, whereas

radiation therapy alleviates symptoms from mass effect metastases

(5,9,24).

DDL exhibits a 48–51.5% 5-year OS rate, which has

been linked to tumor location and the quality of the treatment

facility. Local recurrence occurs in 62.4% of cases. Surgical

resection is the standard therapy, with complete resection

preferred over marginal resection. Radiation is advisable for

high-grade DDL in the extremity for improved local control, and

chemotherapy is an option for DDL with a high recurrence risk

(16,25–27).

ML

ML is a distinct subtype of LPS that represents

20–30% of all LPS cases and is characterized by its unique clinical

behavior, histopathological features and molecular profile. ML is a

slow-growing, painless mass that predominantly affects adults aged

30–60 years, with the most common site being the deep soft tissue

of the extremities (28,29). ML is classified into two types based

on the 5% cut-off of the round cell component, namely, low-grade ML

(also called pure ML) and high-grade ML (30,31).

Despite being radiosensitive and occasionally recurrent locally, ML

tends to metastasize to unusual sites, including the soft tissues

and bones (32,33). ML diagnosis and staging are

challenging owing to the broad spectrum of clinical presentations.

Staging of ML is usually performed by whole-body MRI and chest CT

(3).

Histologically, ML exhibits a distinctive feature

from WDL and DDL, and is marked by a unique gelatinous myxoid

stroma interspersed with lipoblasts and a prominent capillary

network (Fig. 4). High-grade ML

frequently exhibits necrosis, hemorrhage and elevated mitotic

activity, which are associated with a worse prognosis (3,34).

Additionally, IHC serves a key role in the diagnosis of ML. DNA

damage-inducible transcript 3 protein (DDIT3) is a sensitive marker

for ML and is highly specific when diffusely present among tumor

cells (35). In a previous study,

the histological grade of ML was assessed using IHC with

phospho-histone H3 and was determined to be associated with ML

prognosis (36).

In most ML cases (>90%), a specific chromosomal

translocation, t(12;16) (q13;p11), characterizes them and results

in the formation of the FUS::DDIT3 fusion protein (37). In some cases, translocation

t(12;22)(q13;q12) may occur, leading to the EWSR1::DDIT3 fusion

protein. These protein fusions can be identified by FISH (38,39).

Moreover, their presence may lead to the upregulation of oncogenic

genes such as MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase (MET),

ret proto-oncogene (RET) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

3-kinase catalytic subunit α (PIK3CA) (40). Upregulation and/or activation

through RTKs, including MET, RET and VEGFRs, contribute to the high

activity level of the PI3K pathway in ML (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the FUS-DDIT fusion

is associated with the IGF-IR/PI3K/AKT and mTOR signaling pathways

(41–43). In addition, a telomerase reverse

transcriptase promoter mutation is commonly observed in most ML

cases, serving a key role in tumorigenesis (44,45).

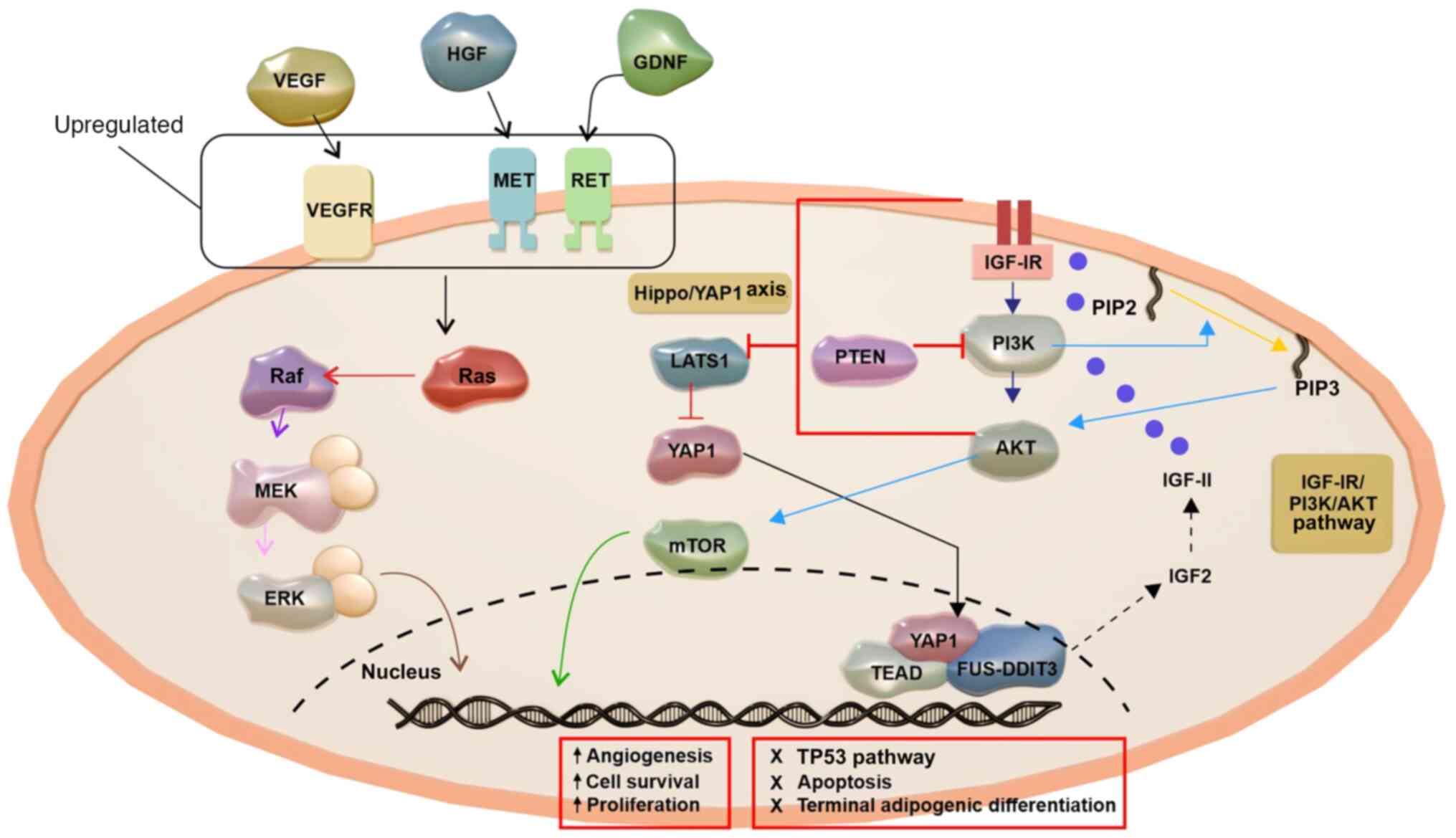

| Figure 5.The pathogenesis of ML. ML

pathogenesis involves the upregulation and activation of RTKs,

including MET, RET and VEGFRs, leading to enhanced PI3K pathway

activity. Growth factors that bind to RTKs, such as IGF-IR,

activate PI3K, transforming PIP2 into PIP3 and triggering AKT

signaling and phosphorylating downstream targets. PTEN inhibits

PI3K signaling by conversion of PIP3 back to PIP2. Moreover, RTKs

activate genes linked to angiogenesis, proliferation and survival

by Ras and the PI3K/AKT pathway. ML is associated with AKT

activation and PIK3CA and PTEN alterations. The oncogenic circuit

includes FUS-DDIT3, the IGF-IR/PI3K/AKT pathway and the Hippo/YAP1

axis. FUS-DDIT3 induces IGF-2 expression, forming an autocrine

IGF-II/IGF-IR signaling loop that activates the IGF-IR/PI3K/AKT

pathway. Signals from IGF-IR and PI3K inhibit Hippo kinase LATS1,

enabling nuclear accumulation of YAP1. FUS-DDIT3 interacts with

YAP1/TEAD in the nucleus, regulating oncogenic gene programs

involved in apoptosis, adipogenesis, the cell cycle and

proliferation. ML, myxoid liposarcoma; RTK, receptor tyrosine

kinase; MET, MET proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase; RET, ret

proto-oncogene; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PIP3,

phosphatidylinositol (3–5)-trisphosphate; PIK3CA,

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α;

IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IGF-IR, IGF-1 receptor; FUS-DDIT3,

fused in liposarcoma-DNA damage-inducible transcript 3; YAP1,

Yes-associated protein 1; LATS1, large tumor suppressor kinase 1;

TEAD, transcriptional enhanced associate domain; HGF, hepatocyte

growth factor; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic

factor. |

Current management approaches involve a combination

of surgical resection, adjuvant RT and chemotherapy. If the tumor

location is deep, preoperative RT should be considered before

surgical resection. Patients with metastatic ML should receive

neoadjuvant chemotherapy (46). ML

has a higher 5-year OS rate compared with DDL, ranging from 81 to

84% (15,47). ML is radiation-sensitive; thus,

surgical resection with radiation is the primary treatment

(48). Preoperative radiation is

recommended for deep or large tumors before surgical resection, and

chemotherapy is used for patients with a positive-margin resection

and metastatic ML (46). Treatment

with radiation alone is not recommended, as it has been associated

with a higher risk of mortality (17).

PL

PL is the rarest and most aggressive subtype of LPS,

accounting for <10% of cases and mainly affecting older adults

aged 50–70 years. Owing to its rarity in young adults, PL diagnosis

in this group should be differentiated from that of other LPSs

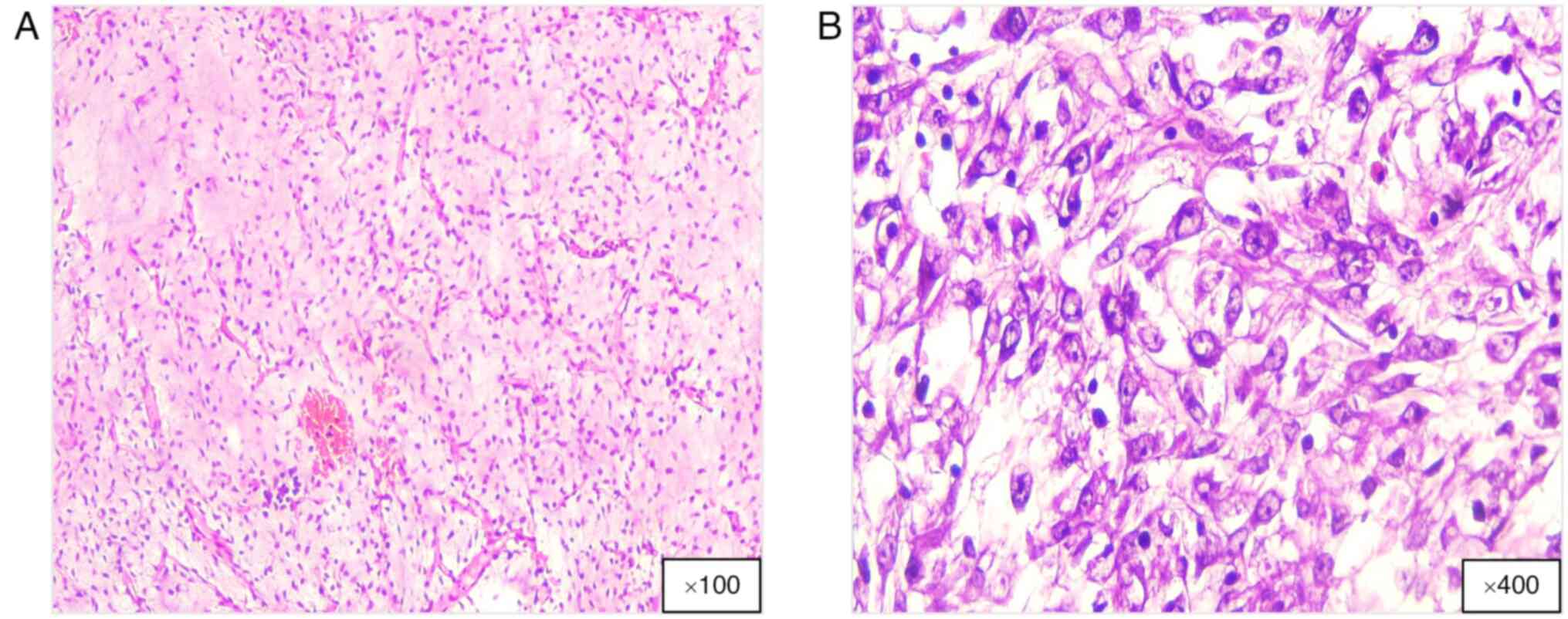

(49). PL is histologically

characterized by a pleomorphic cellular structure (Fig. 6), including bizarre, multinucleated

tumor cells and pleomorphic lipoblasts (50). Most patients with PL present with a

rapidly growing, painless mass, predominantly in the extremities

(28,51). Although PL frequently develops in

the deep soft tissues, it can also occur in the retroperitoneum and

in superficial tissues such as the subcutis or dermis (52,53).

PL pathogenesis involves complex genetic and molecular changes

notable for the lack of unifying molecular alterations, which is

frequently observed in STS with intricate karyotypes. Unlike other

LPS subtypes, such as WDL and DDL, PL does not exhibit MDM2 or CDK4

amplification. This genetic complexity indicates that distinct

dominant molecular abnormalities are unlikely to be the basis of PL

tumorigenesis and progression (54).

PL exhibits molecular profiles that align more

closely with other pleomorphic sarcomas than with atypical

lipomatous tumors, WDL, DDL or ML. Molecular investigations of PL

are hindered due to the rarity of PL. Genetic abnormalities in PL

include complex karyotypic alterations, with TP53 mutations

observed in 60% of cases and NF1 mutations in 5% of all PL cases

(55). Tumors typically exhibit

intricate patterns, demonstrating gains in regions 1p, 1q21-q32,

2q, 3p, 3q, 5p12-p15, 5q, 6p21, 7p and 7q22 (55). A previous study has reported losses

in the areas of 1q, 2q, 3p, 4q, 10q, 11q, 12p13, 13q14, 13q21-qter

and 13q23-24 (55). Other studies

have demonstrated that 60% of PL cases feature a deletion at

13q14.2-q14.3, which encompasses the tumor suppressor RB1 (55–57).

Amplified in PL, the mitotic arrest-deficient gene (MAD2) may serve

a notable role (57). A previous

study with a small sample size of PL cases reported a 13-fold

upregulation of MAD2 compared with normal fat samples (57). Additionally, deletions in PL,

specifically at 17p13 and 17q11.2, where the TP53 gene and

sarcoma-associated tumor suppressor neurofibromatosis type 1

reside, have been observed (56,57).

The diagnosis of PL requires a multidisciplinary

approach. MRI and CT are key for tumor staging. In PL, 60% of the

cases appear as well-defined masses with heterogeneous features,

which indicate necrosis and hemorrhage (51). Histopathological evaluation is the

gold standard, often enhanced by IHC to differentiate PL from other

high-grade sarcomas. The presence of spindle epitheloid pleomorphic

cells and pleomorphic lipoblasts are characteristic of PL. IHC has

limited value in diagnosing PL due to its non-specific

immunoprofile and variable positivity for SMA, desmin and CD34,

usually showing focal positivity. Other IHC markers, such as MDM2

and CDK4, are generally negative in PL, allowing differentiation

from other LPS subtypes (50,58–60).

Managing PL is challenging due to its aggressive

nature and high metastatic potential. Even with optimal surgical

management, local and distant recurrence risks remain elevated.

Preoperative RT may help reduce tumor size for improved surgical

margins. PL prognosis is poorer compared with that of other LPS

types, with stagnant survival rates of >20 years. Previously,

doxorubicin combined with ifosfamide demonstrated some efficacy and

neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapies were associated with improved

survival. Trabectedin and eribulin are therapeutic options for

advanced cases of PL. Ongoing efforts are key to developing new

treatments; however, the identification of targetable aberrations,

particularly the loss of p53 and RB pathway proteins, are difficult

to utilize therapeutically (61–65).

PL exhibits local recurrence and metastasis rates

that range from 30 to 50%. The overall 5-year survival rate is

~60%. Metastatic spread predominantly impacts the lungs and pleura.

Various factors, including central tumor location, increased depth,

larger size and a higher mitotic count, are associated with a less

favorable prognosis (51,66).

Table I summarizes

the genomic alterations in the LPS subtypes, detailing the

demographics, morphology, immunophenotype, growth rates,

recurrence, metastasis and therapy responses. WDL and DDL exhibit

MDM2 and CDK4 amplifications on chromosome 12q13-15 (3,5,8–10).

MDM2 inhibits p53, promoting unchecked cellular growth; thus,

inhibitors such as idasanutlin are undergoing investigations to

restore p53 function and induce apoptosis. CDK4 amplification

disrupts cell-cycle regulation, which makes CDK4/6 inhibitors, such

as palbociclib, a potential therapeutic agent for tumor control.

Resistance to chemotherapy and RT is one of the key challenges in

the treatment of WDL and DDL. Multitargeted tyrosine kinase

inhibitors, including pazopanib, demonstrate antitumor effects.

Current research on HDAC inhibitors, such as vorinostat, along with

ICIs, including pembrolizumab, has demonstrated potential in the

treatment of WDL (3,5,8–10). ML

features chromosomal translocations such as t(12;16) and t(12;22),

which result in FUS-DDIT 3 and EWSR1-DDIT 3 fusions (3,5,8). ML

responds well to chemotherapy, especially anthracycline regimens.

Novel immunotherapeutic strategies targeting cancer-testis antigens

(for example, New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1)

demonstrate potential with vaccine-based approaches. Checkpoint

inhibitors, such as atezolizumab, are evaluated with other

treatments against ML tumors (3,5,8). PL is

the most aggressive LPS subtype, lacking MDM2 and CDK 4

amplifications, and characterized by high pleomorphic histology

(3,5,58,61).

Treatment options are limited. However, doxorubicin and ifosfamide

are effective, and eribulin and trabectedin are alternatives for

advanced disease. Molecular studies point to VEGFR-2 as a target,

prompting investigations into tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as

apatinib (3,5,58,61).

| Table I.Summary of the genomic biomarkers of

LPS. |

Table I.

Summary of the genomic biomarkers of

LPS.

| LPS subtype | Age range,

years | Predilection | Morphological

features |

Immuno-phenotype | Molecular

markers/genomics alterations | Growth rate | Likelihood of

metastasis | Treatment | Recurrence | Therapy response

(radiotherapy and chemotherapy) | Targeted

therapy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| WDL | 50-60 | Extremities,

retroperitoneum | Mature adipocytes,

atypical stromal cells and a limited number of lipoblasts | MDM2(+), CDK(+),

DDIT3(−), S100(+), CD34(−). p16(+), p53 wild-type | MDM2 and CDK4,

12q13-15 amplification | Slow | Low | Surgical resection

with negative margins | Low | Poor | Idasanutlin, MDM2

antagonist; palbociclib, CDK4/6 inhibitor; everolimus, mTOR

inhibitor; pazopanib, multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor;

pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1, immune checkpoint inhibitors; vorinostat,

histone deacetylase inhibitors) | (3,5,8–10) |

| DDL | 50-70 | Extremities,

retroperitoneum | Biphasic structure

with i) WD component: Mature adipocytes intermingled with atypical

stromal cells and hyperchromatic nuclei; and ii) DD component:

Spindle cells, hyperchromasia, mitotic figures and

pleomorphism | MDM2(+), CDK4(+),

DDIT3(−), S100(+), CD34(−), p16(+), p53 wild-type or mutant | MDM2 and CDK4,

12q13-15 amplification and other chromosomal abnormalities | Rapid | High | Surgical resection,

radiotherapy and chemotherapy/targeted therapy | High | Poor | Idasanutlin, MDM2

antagonist; palbociclib, CDK4/6 inhibitor | (3,5,8,9) |

| ML | 30-60 | Thigh or other

proximal extremities | Unique gelatinous

myxoid stroma interspersed with lipoblasts and a prominent

capillary network; occasionally exhibits necrosis, hemorrhage and

elevated mitotic activity | MDM2(−), CDK4(−),

DDIT3(+), PHH3(+), S100(+), CD34(−), p16(−), p53 wild type | t(12;16) with

FUS-DDIT3 fusion t(12;22) with EWSR1-DDIT3 fusion | Slow | Low to medium,

depends on the degree of differentiation | Surgical resection,

radiotherapy and chemotherapy/targeted therapies | High | Commonly

sensitive | CMB305,

immuno-therapeutic for NY-ESO-1; atezolizumab, anti PD-L1 | (3,5,8) |

| PL | 50-70 | Lower and/or upper

limbs | Pleomorphic

cellular architecture, bizarre, multinucleated tumor cells and

pleomorphic lipoblasts | MDM2(−), CDK4(−),

DDIT3(−), S100(+), SMA(+), desmin(+), CD34(+), p16(+), p53 mutant

hyper-expression | No MDM2 or CDK4

amplification; complex karyotype and lack of specificity | Rapid | High | Surgical resection,

radiotherapy and chemotherapy | High | Poor | Apatinib, VEGFR-2

tyrosine kinase inhibitor | (3,5,58,61) |

Conclusion

Numerous studies have established the use of

molecular biomarkers in elucidating the characteristics of sarcoma

and predicting its prognosis. Specific genetic alterations, such as

MDM2 and CDK4, along with 12q13-15 amplification in WDL and DDL,

are associated with a poor therapeutic response. By contrast,

chromosomal translocations including t(12;16) with FUS-DDIT3 fusion

and t(12;22) with EWSR1-DDIT3 fusion in ML are linked to

sensitivity to therapy, although they confer higher recurrence

rates. Furthermore, the complex karyotype and lack of molecular

specificity in PL is associated with an unfavorable response to

treatment and increased recurrence. MDM2 and CDK4 amplification

serve a key role in diagnosis, prediction of tumor recurrence and

prognosis. A comprehensive diagnosis of sarcoma requires further

study into each molecular alteration and the current World Health

Organization classification (28).

Surgical intervention facilitates tumor removal and provides

samples for subsequent molecular analysis. Further research is

warranted to explore the integration of molecular biomarkers with

the WHO grading system to enhance treatment decision-making, which

may potentially lead to a more accurate diagnosis, prognosis and

therapeutic strategies for the treatment of sarcoma in the

future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Auliana Hayu

Kusumastuti and Dr Thea Saphira Mugiarto (Department of Anatomical

Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Gadjah

Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia) for their assistance in

managing the administrative tasks related to this study.

Funding

The present review was supported by the Academic Excellence

Grant (Program Peningkatan Academic Excellence 2024) provided by

the Universitas Gadjah Mada (grant no.

6243/UN1/FKKMK/PPKE/PT/2024).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ED conceptualized the article and wrote the first

draft of the manuscript. RM, YP, SA, RB and AS collected materials

(literature). RB and AS prepared the table and figures. IW

contributed with pathological expertise. ED, RM, YP, SA, RB, AS and

IW made significant contributions to the critical review, editing,

revision and final decision to submit the manuscript for

publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present review received ethical approval from

the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of

Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Gadjah Mada University

(Yogyakarta, Indonesia; approval no. KE/FK/1510/EC/2024).

Patient consent for publication

The requirement to obtain informed consent for the

publication of histopathological images was waived by the Ethics

Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing,

Gadjah Mada University (Yogyakarta, Indonesia) in accordance with

institutional guidelines for the use of anonymized, retrospective

data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jonczak E, Grossman J, Alessandrino F,

Seldon Taswell C, Velez-Torres JM and Trent J: Liposarcoma: A

journey into a rare tumor's epidemiology, diagnosis,

pathophysiology, and limitations of current therapies. Cancers

(Basel). 16:38582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ducimetière F, Lurkin A, Ranchère-Vince D,

Decouvelaere AV, Péoc'h M, Istier L, Chalabreysse P, Muller C,

Alberti L, Bringuier PP, et al: Incidence of sarcoma histotypes and

molecular subtypes in a prospective epidemiological study with

central pathology review and molecular testing. PLoS One.

6:e202942011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH and Jones RL:

Clinical and molecular spectrum of liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol.

36:151–159. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fletcher C, Unni K and Mertens F: World

Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and

genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 3rd edition. IARC

Press; 2002

|

|

5

|

Zhou XP, Xing JP, Sun LB, Tian SQ, Luo R,

Liu WH, Song XY and Gao SH: Molecular characteristics and systemic

treatment options of liposarcoma: A systematic review. Biomed

Pharmacother. 178:1172042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yee EJ, Stewart CL, Clay MR and McCarter

MM: Lipoma and its doppelganger: The atypical lipomatous

tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma. Surg Clin North Am.

102:637–656. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lu J, Wood D, Ingley E, Koks S and Wong D:

Update on genomic and molecular landscapes of well-differentiated

liposarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Mol Biol Rep.

48:3637–3647. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Somaiah N and Tap W: MDM2-p53 in

liposarcoma: The need for targeted therapies with novel mechanisms

of action. Cancer Treat Rev. 122:1026682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Thway K: Well-differentiated liposarcoma

and dedifferentiated liposarcoma: An updated review. Semin Diagn

Pathol. 36:112–121. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bouyahya A, El Allam A, Aboulaghras S,

Bakrim S, El Menyiy N, Alshahrani MM, Al Awadh AA, Benali T, Lee

LH, El Omari N, et al: Targeting mTOR as a cancer therapy: Recent

advances in natural bioactive compounds and immunotherapy. Cancers

(Basel). 14:55202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Song Z, Lu L, Gao Z, Zhou Q, Wang Z, Sun L

and Zhou Y: Immunotherapy for liposarcoma: Emerging opportunities

and challenges. Future Oncol. 18:3449–3461. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dancsok AR, Setsu N, Gao D, Blay JY,

Thomas D, Maki RG, Nielsen TO and Demicco EG: Expression of

lymphocyte immunoregulatory biomarkers in bone and soft-tissue

sarcomas. Mod Pathol. 32:1772–1785. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kim JR, Moon YJ, Kwon KS, Bae JS, Wagle S,

Kim KM, Park HS, Lee H, Moon WS, Chung MJ, et al: Tumor

infiltrating PD1-positive lymphocytes and the expression of PD-L1

predict poor prognosis of soft tissue sarcomas. PLoS One.

8:e828702013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Smith CA, Martinez SR, Tseng WH, Tamurian

RM, Bold RJ, Borys D and Canter RJ: Predicting survival for

well-differentiated liposarcoma: The importance of tumor location.

J Surg Res. 175:12–17. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Vos M, Koseła-Paterczyk H, Rutkowski P,

van Leenders GJLH, Normantowicz M, Lecyk A, Sleijfer S, Verhoef C

and Grünhagen DJ: Differences in recurrence and survival of

extremity liposarcoma subtypes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 44:1391–1397.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Vos M, Grünhagen DJ, Koseła-Paterczyk H,

Rutkowski P, Sleijfer S and Verhoef C: Natural history of

well-differentiated liposarcoma of the extremity compared to

patients treated with surgery. Surg Oncol. 29:84–89. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Amer KM, Congiusta DV, Thomson JE, Elsamna

S, Chaudhry I, Bozzo A, Amer R, Siracuse B, Ghert M and Beebe KS:

Epidemiology and survival of liposarcoma and its subtypes: A dual

database analysis. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 11 (Suppl 4):S479–S484.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nascimento AG: Dedifferentiated

liposarcoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 18:263–266. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Haddox CL and Riedel RF: Recent advances

in the understanding and management of liposarcoma. Fac Rev.

10:12021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mantilla JG, Ricciotti RW, Chen EY, Liu YJ

and Hoch BL: Amplification of DNA damage-inducible transcript 3

(DDIT3) is associated with myxoid liposarcoma-like morphology and

homologous lipoblastic differentiation in dedifferentiated

liposarcoma. Mod Pathol. 32:585–592. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu H, Wang X, Liu L, Yan B, Qiu F and

Zhou B: Targeting liposarcoma: Unveiling molecular pathways and

therapeutic opportunities. Front Oncol. 14:14840272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Casadei L, de Faria FCC, Lopez-Aguiar A,

Pollock RE and Grignol V: Targetable pathways in the treatment of

retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 14:13622022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hirata M, Asano N, Katayama K, Yoshida A,

Tsuda Y, Sekimizu M, Mitani S, Kobayashi E, Komiyama M, Fujimoto H,

et al: Integrated exome and RNA sequencing of dedifferentiated

liposarcoma. Nat Commun. 10:56832019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gahvari Z and Parkes A: Dedifferentiated

liposarcoma: Systemic therapy options. Curr Treat Options Oncol.

21:152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Haddox CL, Hornick JL, Roland CL, Baldini

EH, Keedy VL and Riedel RF: Diagnosis and management of

dedifferentiated liposarcoma: A multidisciplinary position

statement. Cancer Treat Rev. 131:1028462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhao J, Du W, Tao X, Li A, Li Y and Zhang

S: Survival and prognostic factors among different types of

liposarcomas based on SEER database. Sci Rep. 15:17902025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gootee JM, Curtin CE, Aurit SJ, Randhawa

SE, Kang BY and Silberstein PT: Treatment facility: An important

prognostic factor for dedifferentiated liposarcoma survival. Fed

Pract. 36 (Suppl 5):S34–S41. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fletcher C, Bridge J, Hogendoorn P and

Mertens F: WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone.

4th edition. IARC Press; 2013

|

|

29

|

Yang L, Chen S, Luo P, Yan W and Wang C:

Liposarcoma: Advances in cellular and molecular genetics

alterations and corresponding clinical treatment. J Cancer.

11:100–107. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Moreau LC, Turcotte R, Ferguson P, Wunder

J, Clarkson P, Masri B, Isler M, Dion N, Werier J, Ghert M, et al:

Myxoid\round cell liposarcoma (MRCLS) revisited: An analysis of 418

primarily managed cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 19:1081–1088. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Haniball J, Sumathi VP, Kindblom LG, Abudu

A, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Jeys L, Spooner D, Peake D and Grimer RJ:

Prognostic factors and metastatic patterns in primary

myxoid/round-cell liposarcoma. Sarcoma. 2011:5380852011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chung PWM, Deheshi BM, Ferguson PC, Wunder

JS, Griffin AM, Catton CN, Bell RS, White LM, Kandel RA and

O'Sullivan B: Radiosensitivity translates into excellent local

control in extremity myxoid liposarcoma: A comparison with other

soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 115:3254–3261. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ho TP: Myxoid liposarcoma: How to stage

and follow. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 24:292–299. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Fiore M, Grosso F, Lo Vullo S,

Pennacchioli E, Stacchiotti S, Ferrari A, Collini P, Lozza L,

Mariani L, Casali PG and Gronchi A: Myxoid/round cell and

pleomorphic liposarcomas: Prognostic factors and survival in a

series of patients treated at a single institution. Cancer.

109:2522–2531. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Scapa JV, Cloutier JM, Raghavan SS,

Peters-Schulze G, Varma S and Charville GW: DDIT3

immunohistochemistry is a useful tool for the diagnosis of myxoid

liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 45:230–239. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Takazawa A, Yoshimura Y, Okamoto M, Tanaka

A, Kito M, Aoki K, Uehara T, Takahashi J, Kato H and Nakayama J:

The usefulness of immunohistochemistry for phosphohistone H3 as a

prognostic factor in myxoid liposarcoma. Sci Rep. 13:47332023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Powers MP, Wang WL, Hernandez VS, Patel

KS, Lev DC, Lazar AJ and López-Terrada DH: Detection of myxoid

liposarcoma-associated FUS-DDIT3 rearrangement variants including a

newly identified breakpoint using an optimized RT-PCR assay. Mod

Pathol. 23:1307–1315. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Crozat A, Åman P, Mandahl N and Ron D:

Fusion of CHOP to a novel RNA-binding protein in human myxoid

liposarcoma. Nature. 363:640–644. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dal Cin P, Sciot R, Panagopoulos I, Aman

P, Samson I, Mandahl N, Mitelman F, Van den Berghe H and Fletcher

CD: Additional evidence of a variant translocation t(12;22) with

EWS/CHOP fusion in myxoid liposarcoma: Clinicopathological

features. J Pathol. 182:437–441. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Negri T, Virdis E, Brich S, Bozzi F,

Tamborini E, Tarantino E, Jocollè G, Cassinelli G, Grosso F,

Sanfilippo R, et al: Functional mapping of receptor tyrosine

kinases in myxoid liposarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 16:3581–3593. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Trautmann M, Cyra M, Isfort I, Jeiler B,

Krüger A, Grünewald I, Steinestel K, Altvater B, Rossig C, Hafner

S, et al: Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling is

functionally essential in myxoid liposarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther.

18:834–844. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Trautmann M, Menzel J, Bertling C, Cyra M,

Isfort I, Steinestel K, Elges S, Grünewald I, Altvater B, Rossig C,

et al: FUS-DDIT3 fusion protein-driven IGF-IR signaling is a

therapeutic target in myxoid liposarcoma. Clin Cancer Res.

23:6227–6238. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Demicco EG, Torres KE, Ghadimi MP, Colombo

C, Bolshakov S, Hoffman A, Peng T, Bovée JV, Wang WL, Lev D and

Lazar AJ: Involvement of the PI3K/Akt pathway in myxoid/round cell

liposarcoma. Mod Pathol. 25:212–221. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Koelsche C, Renner M, Hartmann W, Brandt

R, Lehner B, Waldburger N, Alldinger I, Schmitt T, Egerer G, Penzel

R, et al: TERT promoter hotspot mutations are recurrent in myxoid

liposarcomas but rare in other soft tissue sarcoma entities. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 33:332014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kunieda J, Yamashita K, Togashi Y, Baba S,

Sakata S, Inamura K, Ae K, Matsumoto S, Machinami R, Kitagawa M and

Takeuchi K: High prevalence of TERT aberrations in myxoid

liposarcoma: TERT reactivation may play a crucial role in

tumorigenesis. Cancer Sci. 113:1078–1089. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Tfayli Y, Baydoun A, Naja AS and Saghieh

S: Management of myxoid liposarcoma of the extremity. Oncol Lett.

22:5962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Dürr HR, Rauh J, Baur-Melnyk A, Knösel T,

Lindner L, Roeder F, Jansson V and Klein A: Myxoid liposarcoma:

Local relapse and metastatic pattern in 43 patients. BMC Cancer.

18:3042018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zheng K, Yu XC, Xu M and Yang Y: Surgical

outcomes and prognostic factors of myxoid liposarcoma in

extremities: A retrospective study. Orthop Surg. 11:1020–1028.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Alaggio R, Coffin CM, Weiss SW, Bridge JA,

Issakov J, Oliveira AM and Folpe AL: Liposarcomas in young

patients: A study of 82 cases occurring in patients younger than 22

years of age. Am J Surg Pathol. 33:645–658. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Downes KA, Goldblum JR, Montgomery EA and

Fisher C: Pleomorphic liposarcoma: A clinicopathologic analysis of

19 cases. Mod Pathol. 14:179–184. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hornick JL, Bosenberg MW, Mentzel T,

McMenamin ME, Oliveira AM and Fletcher CDM: Pleomorphic

liposarcoma: Clinicopathologic analysis of 57 cases. Am J Surg

Pathol. 28:1257–1267. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gardner JM, Dandekar M, Thomas D, Goldblum

JR, Weiss SW, Billings SD, Lucas DR, McHugh JB and Patel RM:

Cutaneous and subcutaneous pleomorphic liposarcoma: A

clinicopathologic study of 29 cases with evaluation of MDM2 gene

amplification in 26. Am J Surg Pathol. 36:1047–1051. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang L, Luo R, Xiong Z, Xu J and Fang D:

Pleomorphic liposarcoma: An analysis of 6 case reports and

literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 97:e99862018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ghadimi MP, Liu P, Peng T, Bolshakov S,

Young ED, Torres KE, Colombo C, Hoffman A, Broccoli D, Hornick JL,

et al: Pleomorphic liposarcoma: Clinical observations and molecular

variables. Cancer. 117:5359–5369. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Conyers R, Young S and Thomas DM:

Liposarcoma: Molecular genetics and therapeutics. Sarcoma.

2011:4831542011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Taylor BS, Barretina J, Socci ND,

Decarolis P, Ladanyi M, Meyerson M, Singer S and Sander C:

Functional copy-number alterations in cancer. PLoS One.

3:e31792008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Singer S, Socci ND, Ambrosini G, Sambol E,

Decarolis P, Wu Y, O'Connor R, Maki R, Viale A, Sander C, et al:

Gene expression profiling of liposarcoma identifies distinct

biological types/subtypes and potential therapeutic targets in

well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Cancer Res.

67:6626–6636. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wei S, Henderson-Jackson E, Qian X and Bui

MM: Soft tissue tumor immunohistochemistry update: Illustrative

examples of diagnostic pearls to avoid pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab

Med. 141:1072–1091. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Oliveira AM and Nascimento AG: Pleomorphic

liposarcoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 18:274–285. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Anderson WJ and Jo VY: Pleomorphic

liposarcoma: Updates and current differential diagnosis. Semin

Diagn Pathol. 36:122–128. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Assi T, Ngo C, Faron M, Verret B, Lévy A,

Honoré C, Hénon C, Le Péchoux C, Bahleda R and Le Cesne A: Systemic

therapy in advanced pleomorphic liposarcoma: A comprehensive

review. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 24:1598–1613. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wan L, Tu C, Qi L and Li Z: Survivorship

and prognostic factors for pleomorphic liposarcoma: A

population-based study. J Orthop Surg Res. 16:1752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Eilber FC, Eilber FR, Eckardt J, Rosen G,

Riedel E, Maki RG, Brennan MF and Singer S: The impact of

chemotherapy on the survival of patients with high-grade primary

extremity liposarcoma. Ann Surg. 240:686–697. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Crago AM and Dickson MA: Liposarcoma:

Multimodality management and future targeted therapies. Surg Oncol

Clin N Am. 25:761–773. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Ebey BN, Naouar S, Faidi B, Lahouar R, Ben

Khalifa B and El Kamel R: Pleomorphic spermatic cord liposarcoma: A

case report and review of management. Int J Surg Case Rep.

81:1057252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Gebhard S, Coindre JM, Michels JJ, Terrier

P, Bertrand G, Trassard M, Taylor S, Château MC, Marquès B, Picot V

and Guillou L: Pleomorphic liposarcoma: Clinicopathologic,

immunohistochemical, and follow-up analysis of 63 cases: A study

from the French federation of cancer centers sarcoma group. Am J

Surg Pathol. 26:601–616. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|