Introduction

Lactylation, a novel post-translational modification

(PTM) characterized by the covalent attachment of lactate to lysine

residues, has emerged as a critical regulatory mechanism in cancer

biology (1). Initially identified

as a metabolic byproduct of anaerobic glycolysis, lactate is now

recognized as a dynamic signaling molecule that orchestrates

cellular adaptation through lactylation. This modification, first

reported on histones in 2019, bridges metabolic reprogramming and

epigenetic regulation, influencing key oncogenic processes such as

proliferation, metastasis, immune evasion and resistance to therapy

(2). Within the tumor

microenvironment (TME), lactate accumulation drives lactylation of

histones and non-histone proteins, modulating interactions among

cancer cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs),

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and immune cells (3). Notably, lactylation reshapes chromatin

structure, alters enzymatic activities in glycolysis and the

tricarboxylic acid cycle, and sustains immunosuppressive niches by

polarizing TAMs towards an M2 phenotype and impairing cytotoxic

T-cell function (4). Furthermore,

lactylation contributes to genomic instability, angiogenesis and

phenotypic plasticity through mechanisms involving DNA repair

modulation and metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk. Emerging therapeutic

strategies targeting lactylation-associated enzymes [such as

lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and monocarboxylate transporter

(MCT1/4)] or disrupting lactate-driven feedback loops hold promise

for overcoming chemoresistance and enhancing the efficacy of

immunotherapy (5). The present

review summarizes the current insights into the role of lactylation

across the hallmarks of cancer, highlighting its potential as a

diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in precision

oncology.

Lactate and lactylation

Initially regarded as a metabolic byproduct of

anaerobic glycolysis, lactate is now recognized as more than its

historical perception as mere waste. Emerging evidence highlights

its critical roles in energy metabolism (6), signaling regulation (7,8) and

cellular homeostasis (9).

Lactylation, a PTM involving covalent attachment of lactate to

lysine residues, mirrors acetylation in mechanism and importance.

First identified on histones by Zhang et al (2) in 2019, lactylation has since been

detected on non-histone proteins, establishing a

metabolic-epigenetic link. This modification, driven by glycolytic

end-product lactate, is mechanistically associated with cancer

progression, inflammatory responses and stem cell regulation

(1). Previous studies underscore

the profound impact of lactylation on the hallmarks of cancer,

including proliferation, metastasis and drug resistance, through

modulation of metabolic enzyme activity (10).

Lactylation-related proteins

Histone lactylation and non-histone

lactylation

PTMs involve the covalent addition of chemical

groups to amino acid residues, altering protein function. Common

PTMs, including phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination

regulate chromatin dynamics and gene expression (11). Histones, comprising core (H2A, H2B,

H3 and H4) and linker (H1 and H5) subtypes, undergo PTM, and these

PTMs are involved in epigenetic regulation (12). Lactylation modification modulates

chromatin structure, DNA-histone interactions and transcriptional

activity. Hypoxia-induced pyruvate accumulation drives lactylation,

particularly at histone 3 lysine 18 (H3K18), H4K5 and H4K18

residues, while H4K5 lactylation (H4K5la) is associated with a poor

prognosis in neuroblastoma (13,14).

In neuroblastoma studies, elevated lactylation levels of the 5th

lysine residue of histone H4 (H4K5la) were found to be notably

associated with a poor clinical prognosis in patients (15).

Non-histone lactylation occurs across organelles

(nucleus, mitochondria and lysosomes) and regulates several

processes, including glycolysis, inflammation and oxidative stress

(16–18). By altering protein conformation,

charge and stability, lactylation impacts enzyme activity and

molecular interactions. For example, in hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC), adenylate kinase 2 lactylation at K28 suppresses

mitochondrial function, driving metastasis (19). In lung squamous cell carcinoma,

glucose transporter 1-driven lactate accumulation induces

lactylation of non-histone proteins [such as

N6-adenosine-methyltransferase 70 kDa subunit (METTL3)], thereby

enhancing the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, reducing

the response to immunotherapy and promoting tumor progression

(20). Similarly, in pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), lactylation of the ENSA protein

inhibits the phosphatase PP2A, activating the STAT3/CCL2 axis. This

axis recruits tumor-associated TAMs and impairs cytotoxic T cell

activity (21).

Non-histone protein lysine lactylation (Kla), an

emerging PTM, has gained notable attention in oncology research.

However, elucidating its mechanisms and achieving clinical

translation present substantial challenges. Although enzymes such

as p300, alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS1) and lysine

acetyltransferase 8 (KAT8) have been reported as potential

lactyltransferases, most possess acyltransferase activity for

acetylation and crotonylation (Kcr). For example, KAT8 catalyzes

eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1a2 K408 lactylation to

promote protein synthesis in colorectal cancer (CRC). However, its

affinity for lactoyl-CoA (Km ≈28 µM) is markedly lower compared

with for acetyl-CoA (Km ≈12 µM), raising questions about its

preferential catalysis of lactylation under high-lactate conditions

(22). Non-enzymatic lactylation

mediated by lactoylglutathione has been reported in liver and

breast cancer; this type of modification is not enzyme-regulated,

making it difficult to target via catalytic enzyme inhibition, and

its physiological importance remains unclear. Functional outcomes

of lactylation also exhibit tissue-specific discrepancies. For

example, p53 K120 lactylation suppresses its tumor-suppressive

function in gastric cancer (23)

yet stabilizes the protein and enhances DNA repair in glioma

(24). Such context-dependent

effects underscore that lactylation functions are highly dependent

on the microenvironment, suggesting that single mechanistic models

can oversimplify the actual complexity.

Regulatory machinery of protein

lactylation

Lactylation, a dynamic PTM, is regulated by three

classes of proteins: Writers (lactyltransferases), erasers

(delactylases) and readers (lactylation-recognition factors).

Collectively, these components orchestrate lactate modification on

histones and non-histone proteins by mediating its addition,

removal and functional interpretation, thereby modulating gene

expression and cellular physiology (Fig. 1). Writers catalyze the addition of a

lactate group to lysine residues: p300, a histone acetyltransferase

(HAT) with dual roles in acetylation and lactylation, was first

identified as a lactyltransferase by Zhang et al (2), linking it to pathologies including

pulmonary fibrosis (25), several

types of cancer (26) and

Parkinson's disease (27). Lysine

acetyltransferase 7 (HBO1), a MYST-family acyltransferase, mediates

several histone modifications such as acetylation, Kcr and

lactylation (28). HBO1

preferentially targets H3K9la, and elevated H3K9la levels in

cervical cancer are strongly associated with HBO1 overexpression

(5), driven by its high affinity

for lactyl-CoA to regulate oncogenic genes. Erasers remove lactate

modifications to reset histone states: Histone deacetylase (HDAC)

1–3 and sirtuin (SIRT) 1–3 function as zinc- and

NAD+-dependent deacetylases with broad delactylase

activity, cleaving both ε-N-L-lactylated and D-lactylated residues

(29). SIRT2 specifically removes

H3K18la/H4K8la to suppress neuroblastoma proliferation and

migration (30), while SIRT3

inhibits HCC by regulating cyclin E2 lactylation levels (31). Readers transduce lactylation

signals: SWI/SNF related BAF chromatin remodeling complex subunit

ATPase 4 (Brg1), a chromatin remodeler, recognizes H3K18la at

promoters of pluripotency genes to facilitate transcriptional

reprogramming (32).

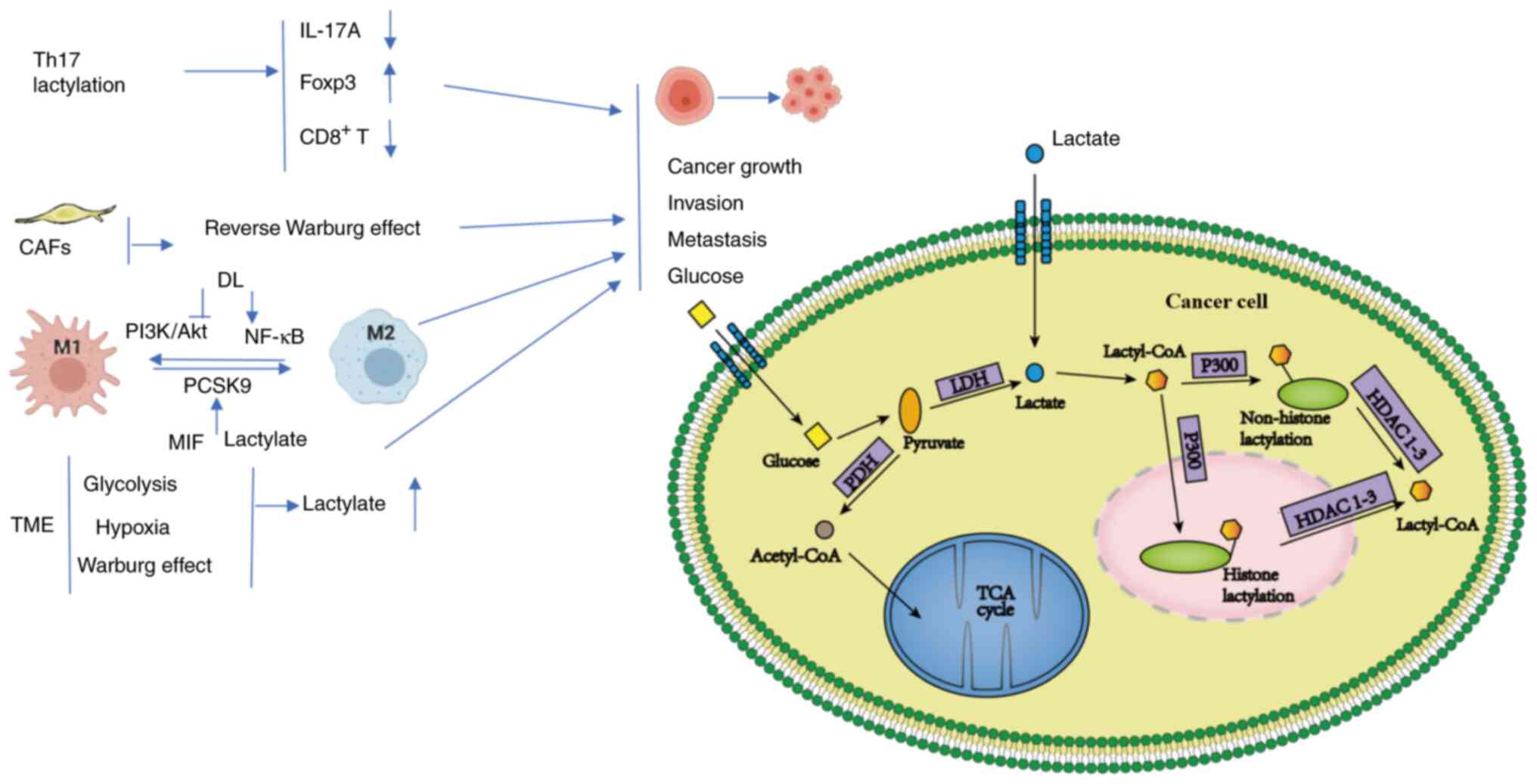

| Figure 1.In the TME, lactate polarizes TAMs to

the M2 phenotype through histone lactylation. Lactate-treated Th17

cells markedly reduce IL-17A and upregulate Foxp3. The high-energy

metabolites (such as lactate and pyruvate) produced by CAFs via

aerobic glycolysis are translocated into adjacent epithelial cancer

cells. DL can promote the transformation of M2 to M1 macrophages by

regulating the lactylation of macrophages, specifically through the

inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway and the activation of the NF-κB

pathway. PCSK9 affect the polarization of TAMs in colon cancer by

regulating MIF and lactate levels. Higher glycolysis, hypoxia and

the Warburg effect elevate lactate levels and promote tumor growth,

evasion and metastasis. In cancer cells, lactate produced from

glucose and exogenous lactate is further metabolized to produce

lactyl-CoA, which can enter and exit the nucleus. p300, as a writer

of lactylations, can add lactyl groups to lysine residues of

histones or non-histone proteins to form lactylations, while

erasers HDAC1-3 remove lactate modification motifs from histones or

non-histone proteins and restore them to their original state. MIF,

macrophage migration inhibitory factor; DL, D-lactic acid; TCA

cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; TME, tumor microenvironment; PDH,

pyruvate dehydrogenase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PCSK9,

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; CAFs,

cancer-associated fibroblasts; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages;

HDAC, histone deacetylase. |

Interaction of lactylation with other

PTMs

Lysine lactylation, as a novel metabolism-dependent

PTM, engages in a complex and dynamic interplay with other PTMs.

This network orchestrates tumor progression through mechanisms

including competitive occupancy of modification sites, shared

catalytic enzymes, cascading signaling and epigenetic

reprogramming. Kla exhibits substrate competition with lysine

acetylation (Kac) and Kcr, a relationship governed by fluctuating

metabolite concentrations and shared enzymatic machinery. HATs

p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP) and HBO1 possess dual

lactyltransferase/acetyltransferase activity and can catalyze

multiple acylation types. For example, HBO1 preferentially

catalyzes either lactylation (H3K9la) or acetylation (H3K9ac) at

histone H3K9, with the type of modification dictated by the

intracellular lactate-to-acetyl-CoA ratio (33,34).

Similarly, de-modifying enzymes HDAC1-3 and SIRT1-3 exhibit both

deacetylase and delactylase activities; SIRT2, for example, removes

H3K18la and H4K8la modifications (33). Lactate and acetyl-CoA compete for

the same lysine residues. In the acidic TME, lactate accumulation

drives H3K18la to replace H3K18ac, activating immunosuppressive

genes such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). Conversely, under

glucose-replete conditions, acetylation predominates, promoting

oncogene transcription (35,36).

Kcr, another prominent Kac, serves key roles in

diseases such as liver cancer (37)

and glioblastoma (GBM) stem cells (38) by modulating histone structure and

function. A previous study suggested potential synergistic roles

for Kla and Kcr in processes such as neural differentiation and

cell proliferation (39). However,

due to its greater hydrophobicity, Kcr can antagonize Kla

modifications in open chromatin regions; for example, H3K56la

suppresses Kcr-mediated activation of inflammatory genes (40). Kla and phosphorylation mutually

amplify oncogenic signals through positive feedback loops. Histone

lactylation (such as H3K18la) activates genes encoding cell cycle

kinases (for example TTK protein kinase and BUB1 mitotic checkpoint

serine/threonine kinase B). Their protein products phosphorylate

LDHA at Tyr239, enhancing LDHA activity and lactate production,

promoting further lactylation (14). Similarly, AMPK phosphorylation of

p300 at Ser89 enhances its lactyltransferase activity, establishing

a metabolic stress-p300 lactylation amplification loop (34). Furthermore, transcription factor EB

(TFEB) lactylation at K91 impedes binding via the action of the E3

ubiquitin ligase WW domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase

2, reducing TFEB ubiquitination and degradation. This stabilization

enhances autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis, supporting tumor

survival (41).

Kla is intricately integrated within the intricate

dynamic PTM network and is particularly interconnected with other

types of lysine acylation (such as Kac and Kcr) via shared core

enzymatic machinery (such as p300/CBP and HBO1 with dual

lactyl/acyl transferase activity; HDACs/SIRTs with dual

deacetylase/delactylase activity). This interdependence underpins

the ‘metabolite-concentration-dependent substrate competition’

hypothesis: Fluctuations in metabolite abundance (such as lactate

and acetyl-CoA) competitively regulate the balance between

different types of acylation, with cascading effects, and pyruvate

dehydrogenase complex component X acetylation inhibits lactate

production, subsequently downregulating H3K56 lactylation (29,39).

However, the downstream mechanistic effects of these interactions

remain largely unknown. Critical unresolved questions include: Do

Kla and Kac/Kcr directly compete for occupancy at identical lysine

residues? How do the distinct chemical properties of the modifying

groups (lactyl, acetyl and the more hydrophobic crotonyl) lead to

the recruitment of specific reader proteins and functional

divergence (such as the Brg1-specific recognition of H3K18la)? How

are these interactions tissue- or tumor-type dependent?

For the emerging Kcr, evidence for functional

synergy or antagonism with Kla in cancer is limited, and the

differential impact of their chemical properties on chromatin

remodeling and signal transduction is poorly understood. The

hijacking of shared regulatory factors by drug-induced

modifications (such as lysine isonicotinylation) highlights the

sensitivity and complexity of the PTM network, yet the pathological

importance of endogenous analogues remains unknown.

Current research often remains descriptive or

focused on isolated pathways. Notable limitations include

insufficient investigation of spatiotemporal dynamics, lack of

rigorous causal validation and inadequate critical assessment of

model systems and technological constraints. These gaps hinder a

comprehensive understanding of the precise role of this

sophisticated metabolic-epigenetic coupling network in

tumorigenesis. Future research should employ tools such as

site-specific mutagenesis, time-resolved omics and metabolic

gradient models to evaluate the kinetics of inter-modification

competition, identify specific effector molecules and assess the

consequences of network perturbation. Overcoming the current

fragmented understanding is essential to providing a solid

theoretical foundation for the development of precision anticancer

strategies targeting key nodes within the PTM network.

Lactylation and the TME

Under aerobic conditions, cancer cells often

metabolize glucose to lactate rather than producing carbon dioxide

and water via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).

This phenomenon, known as the Warburg effect (42,43),

leads to increased intracellular and extracellular lactate

concentrations. As a hallmark of cancer metabolism, the Warburg

effect enables cancer cells to meet their high ATP demands by

upregulating glycolysis even when oxygen is sufficient. In the TME,

lactate regulates interactions between cells, CAFs, TAMs and

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), thereby establishing a

microenvironment favorable for tumor cell growth and immune evasion

(3).

TAMs, a key immune cell component in the TME, serve

a crucial role in carcinogenesis and progression. Based on their

functions, TAMs are classified into the pro-inflammatory,

anticancer M1 type and the anti-inflammatory, pro-cancer M2 type.

Lactate can promote the polarization of TAMs towards an

immunosuppressive M2 phenotype through histone lactylation when

lactate levels are increased (2). T

cells serve a central role in antitumor immunity while also being

key components of the TME. Lactylation of moesin at K72 enhances

the suppressive function of regulatory T cells (Tregs).

Concurrently, extracellular lactate upregulates programmed cell

death protein 1 (PD-1) expression via G protein-coupled receptor 81

(GPR81) signaling, inducing exhaustion in CD8+ T cells

(44). Furthermore, lactate

promotes the expansion of PD-L1+ neutrophils through the

MCT1/NF-κB axis, ultimately compromising antitumor immunity

(45).

The formation of the TME is primarily based on

glycolysis, hypoxia and the Warburg effect, which collectively

influence tumor cell growth, invasion and metastasis. In the TME,

CAFs, rather than cancer cells themselves, utilize aerobic

glycolysis, a phenomenon known as the reverse Warburg effect

(46). The high-energy metabolites

(such as lactate and pyruvate) produced by CAFs through aerobic

glycolysis are transported into adjacent epithelial cancer cells,

where they undergo aerobic mitochondrial metabolism. This metabolic

pattern increases ATP production in cancer cells, thereby promoting

cancer growth and metastasis (47).

In summary, the metabolic characteristics of TME,

notably the Warburg effect and reverse Warburg effect, drive

substantial lactate accumulation. Lactylation serves as a pivotal

metabolic-epigenetic coupling mechanism that extensively regulates

the functional states and interactions of a range of cell types in

the TME, including cancer cells, CAFs, immune cells and other

stromal components. Collectively, these lactate-driven

modifications foster an immunosuppressive and pro-tumorigenic

microenvironment that supports tumor growth, invasion, metastasis

and immune evasion. This understanding provides a crucial

foundation for deciphering tumor progression and developing novel

therapeutic strategies targeting the TME.

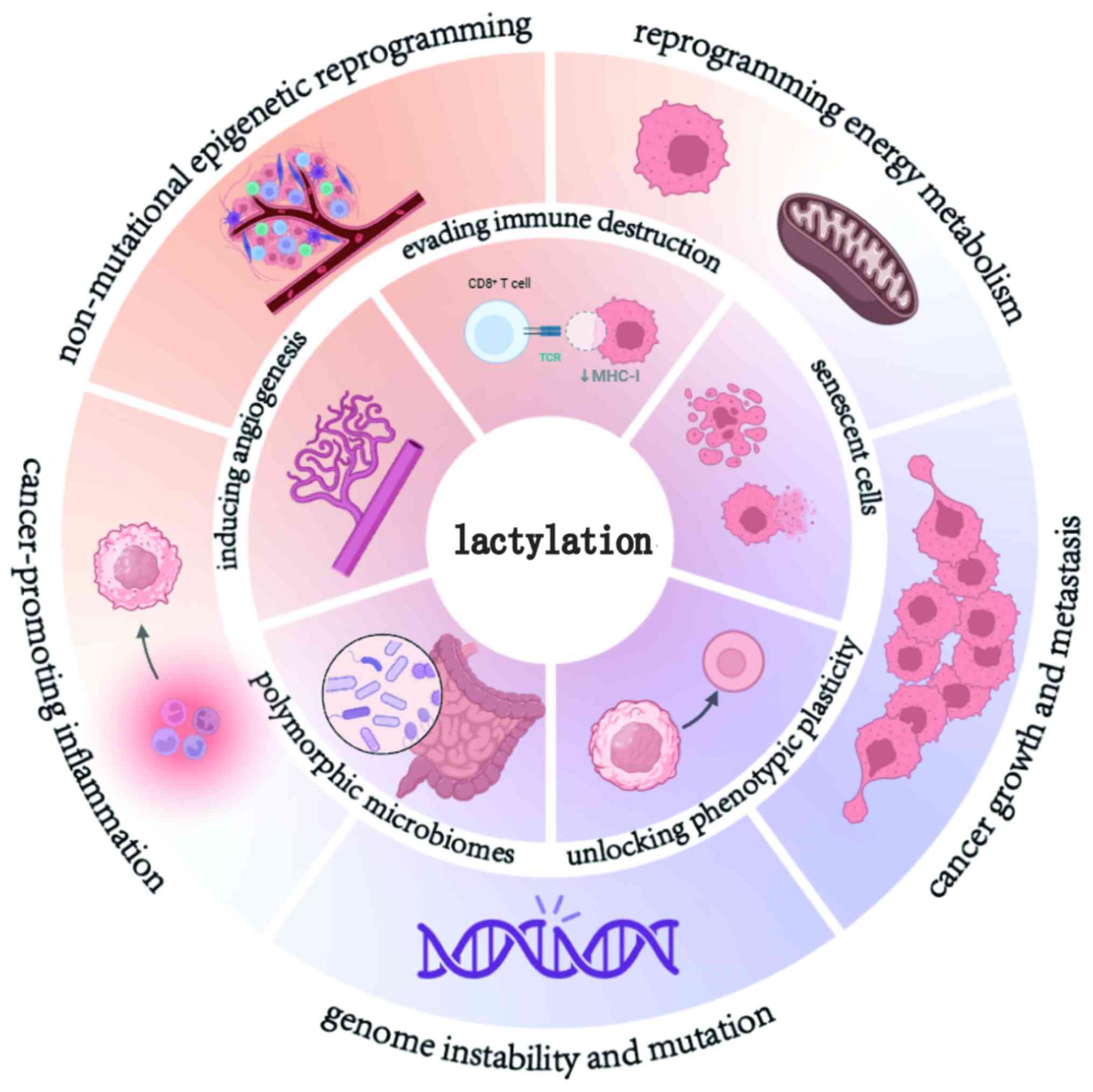

Lactylation and the hallmarks of cancer

The hallmarks of cancer are pivotal characteristics

employed in cancer research to distinguish tumor cells from normal

cells. Since their conception, the hallmarks have expanded from the

initial six to 14 (48,49), including sustaining proliferative

signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death,

enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, activating

invasion and metastasis, genome instability and mutation, promoting

inflammation, reprogramming energy metabolism, evading immune

destruction, unlocking phenotypic plasticity, non-mutational

epigenetic reprogramming, polymorphic microbiomes and senescent

cells. Enabling replicative immortality and activating invasion and

metastasis are closely associated with cancer growth and

metastasis. These 14 hallmarks are collectively summarized in

Fig. 2. The hallmarks of cancer

provide a systematic framework for understanding tumor biology.

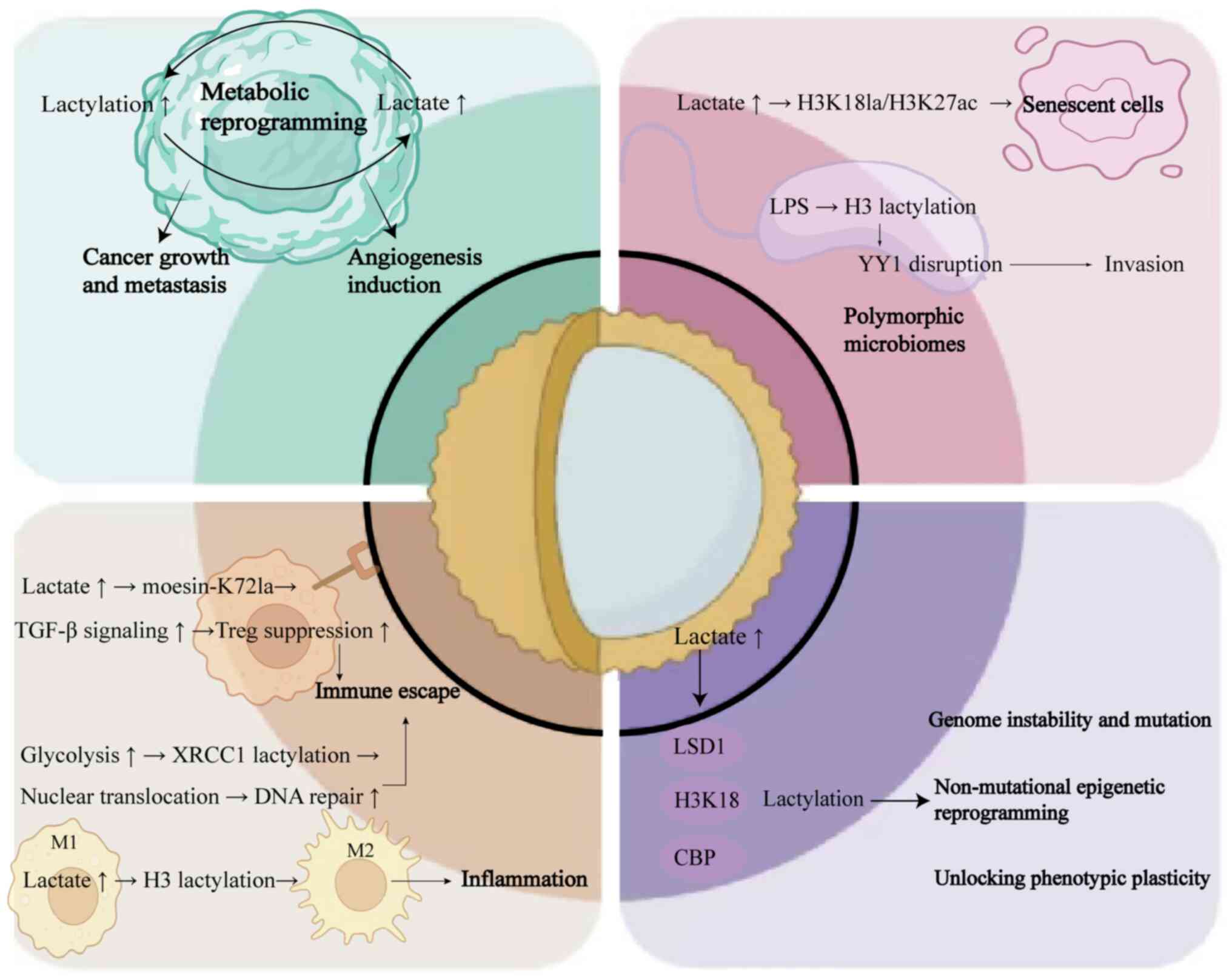

Lactylation serves as a central node (Fig. 3), exerting a pivotal role across the

10 established cancer hallmarks via a metabolic-epigenetic

bidirectional regulatory axis.

Metabolic reprogramming-driven

malignant proliferation and metastasis

Lactylation serves as both a core effector and

driver of metabolic reprogramming. By establishing self-reinforcing

positive feedback loops, it not only directly couples glycolysis

with epigenetic reprogramming but also maintains cancer stem cell

properties and promotes angiogenesis. This multifaceted mechanism

drives tumor growth, invasion and metastasis across multiple

dimensions.

Lactylation and metabolic

reprogramming

Lactylation directly couples glycolysis with

epigenetic reprogramming, forming self-reinforcing pro-tumorigenic

circuits. Histone lactylation serves as a critical link between

metabolic reprogramming and transcriptomic dysregulation in cancer

cells (4). In malignant cells,

metabolic alterations induce fluctuations in lactate levels, which

manifest as changes in histone lactylation. Conversely, shifts in

the histone lactylation landscape reshape the transcriptomic

profile to accommodate the metabolic reprogramming demands within

the TME. This establishes a metabolic reprogramming-lactylation

positive feedback loop that accelerates tumor progression. For

example, in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), lactylation

levels are markedly elevated compared with normal kidney tissue

(50). This increase is

particularly pronounced upon loss of the key tumor suppressor von

Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein. VHL deficiency leads to

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) accumulation, which directly

promotes lactate production via glycolysis. Furthermore,

lactylation enhances the transcriptional activity of

platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ). Activation of

the PDGFRβ signaling pathway subsequently elevates lactylation

levels, establishing a self-reinforcing circuit that drives ccRCC

progression (50). Similarly, in

pancreatic cancer, lactate from TAMs induces lactylation of

nucleolar and spindle-associated protein 1 (NUSAP1), upregulating

its expression. NUSAP1 forms a transcriptional complex with c-Myc

and HIF-1α. These transcription factors bind to the LDHA promoter,

enhancing LDHA expression, thereby promoting glycolysis and

increasing lactate production. This creates another positive

feedback loop (51). Collectively,

these metabolic reprogramming-lactylation positive feedback

circuits serve a pivotal role in driving tumor growth and

metastasis.

Lactylation in tumor growth and

metastasis

Tumor growth and metastasis are governed by multiple

factors, including cancer stemness and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer

stemness refers to the capacity of tumor cells for self-renewal and

differentiation into a range of cell types, which is essential for

tumor progression and dissemination. Activation of the NF-κB

signaling pathway induces histone H3 lactylation, increasing

expression of the long non-coding RNA LINC01127. LINC01127 sustains

GBM stemness through the MAP4K4/JNK/NF-κB axis (52). Furthermore, Feng et al

(53) demonstrated that liver

cancer stem cells (LCSCs) exhibit elevated glycolytic flux, lactate

accumulation and lactylation levels compared with HCC cells.

Notably, histone H3K56la is closely associated with the

tumorigenicity and stemness maintenance of LCSCs. High glycolytic

flux provides the lactate substrate driving H3K9la/H3K56la

modifications, while lactylation, in-turn, upregulates glycolytic

enzyme expression. This establishes an LCSC-specific

metabolic-epigenetic memory that perpetuates a self-sustaining

loop.

Lactylation and inducing

angiogenesis

As the circulatory system is a major route of

metastasis, tumor angiogenesis is critically important for both

tumor metastasis and growth. Lactate, functions as a potent

pro-angiogenic factor and promotes angiogenesis through multiple

mechanisms (54–56). Lactate activates the GPR81 receptor

on endothelial cells, stimulating angiogenesis and subsequently

promoting tumor cell proliferation and survival (55). Through HIF-dependent pathways,

lactate, transported via MCT1, inhibits prolyl hydroxylases,

thereby stabilizing HIF-1α. This stabilization enhances VEGF

expression and angiogenesis. In HIF-independent pathways, lactate

promotes angiogenesis via ROS generation and NF-κB/IL-8 signaling

(54,55). Mounting evidence has established

lactylation as a critical regulator of tumor angiogenesis. For

example, Luo et al (57)

demonstrated that lactylation of HIF1α at K672 promotes

angiogenesis in prostate cancer by enhancing transcription of the

cell migration-inducing and hyaluronan-binding protein gene.

Furthermore, as previously discussed, NUSAP1 forms a

transcriptional complex with c-Myc and HIF-1α that binds to the

LDHA promoter, augmenting LDHA expression to drive angiogenesis and

metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (51).

Microbiota, senescence and the

lactylation epigenetic regulatory axis

Lactylation and polymorphic microbiomes

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that gut

microbiota exerts autonomous regulatory effects on oncogenesis and

tumor evolution (49). Notably,

intestinal microbial diversity and compositional dynamics markedly

modulate cancer initiation, malignant transformation and

therapeutic responsiveness (58,59).

Mechanistically, microbial-epigenetic crosstalk may involve

lactylation-mediated pathways.

In pathogen-induced epigenetic remodeling,

enteropathogens (such as Salmonella) induce marked

alterations in long non-coding RNA networks within colonic

epithelia. Wang et al (60)

revealed that lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated histone lactylation

at the LINC00152 promoter disrupts YY1 transcription factor

binding, facilitating CRC invasion and metastatic dissemination. In

bacterial metabolic adaptation, quantitative lactylome profiling of

Escherichia coli identified 1,047 modification sites, with

NAD-dependent lysine deacetylase-mediated delactylation of pyruvate

kinase I K382 serving as a critical regulator of bacterial

glycolysis. This post-translational control enhances pyruvate

kinase activity, potentiating bacterial glycolytic flux and

proliferation (61).

Lactylation and senescent cells

Cellular senescence is characterized by irreversible

cell cycle exit accompanied by distinct morphological and metabolic

alterations, including activation of the senescence-associated

secretory phenotype (SASP). The SASP entails secretion of bioactive

mediators (chemokines, cytokines and proteases) that exert

paracrine oncogenic effects within TME, driving neoplastic

proliferation, apoptotic resistance, angiogenesis, metastatic

dissemination and immune suppression (49). Pioneering work by Maekawa and

Yamanaka (62) identified GLIS

family zinc finger 1 (GLIS1) as a pluripotency-associated

transcription factor capable of reprogramming both normal and

senescent cells. During early reprogramming, GLIS1 directly binds

glycolytic gene loci to activate their transcription while

repressing somatic gene chromatin, inducing metabolic rewiring from

OXPHOS to dominance of glycolysis with concomitant lipogenesis.

This glycolytic surge increases intracellular acetyl-CoA and

lactate pools, fueling secondary epigenetic modifications including

H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and H3K18 lactylation (H3K18la) at loci

associated with pluripotency. These chromatin accessibility changes

facilitate transcriptional reprogramming through structural

relaxation (63). Notably, Rong

et al (64) revealed that

GLIS1 overexpression in exhausted HCC-infiltrating CD8+

T cells promotes T cell dysfunction via a serum/glucocorticoid

regulated kinase 1-STAT3-PD-1 axis activation, mechanistically

linking metabolic control to immune evasion.

Immune microenvironment remodeling and

immune evasion

Within the TME, lactate modulates interactions among

a range of cell types, including tumor cells, CAFs, TAMs and TILs,

to shape an immunosuppressive milieu conducive to tumor growth and

immune evasion. This process is fundamentally associated with key

hallmarks of cancer: Tumor-promoting inflammation, inducing

angiogenesis and evading immune destruction.

Lactylation and tumor-promoting

inflammation

Lactate-mediated polarization of TAMs toward the M2

phenotype constitutes a central mechanism in its promotion of

tumor-associated inflammation. Beyond histone lactylation, multiple

specific pathways have been elucidated. Wang et al (65) demonstrated that PCSK9 inhibition

reduced M2 polarization by modulating MIF and lactate levels. Han

et al (66) reported that

D-lactate promotes M2-to-M1 transition through PI3K/AKT pathway

suppression and NF-κB pathway activation. Liu et al

(67) established that lactate

stabilizes HIF-2α via mTORC1-dependent inhibition of the

TFEB/ATP6V0d2 axis, enhancing expression of M2-associated genes

(such as VEGF). Zhang et al (8) identified lactate binding to

mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein as an inhibitor of

retinoic acid-inducible gene I signaling, indirectly facilitating

M2 polarization. Lactate-induced histone lactylation functions as a

‘lactate clock’, enabling macrophages to acquire LPS tolerance and

sustain M2-related gene expression (2,68).

Collectively, these mechanisms program TAMs to exert

immunosuppressive, pro-angiogenic and tumor-promoting

functions.

Lactylation and evading immune

destruction

Evading immune destruction, a defining hallmark of

cancer (10), is garnering

increasing attention. Lactate within the TME serves a pivotal role

in tumor immune evasion. It not only drives the polarization of T

cells and macrophages toward immunosuppressive phenotypes, such as

promoting Treg differentiation and M2-type TAM formation, but also

enhances the functionality of these immunosuppressive cells through

multiple mechanisms, thereby facilitating tumor cell escape from

immune surveillance (69).

Lactate amplifies immunosuppression by expanding the

population and augmenting the activity of myeloid-derived

suppressor cells (MDSCs), resulting in impaired cytotoxic T cell

and natural killer cell function (70). Furthermore, lactylation modulates

DNA repair capacity, indirectly promoting immune evasion. Li et

al (71) demonstrated that

glycolytic reprogramming enhanced X-ray repair cross-complementing

protein 1 (XRCC1) lactylation at K247, promoting its nuclear

translocation and DNA repair function, ultimately conferring

resistance to radiotherapy. Similarly, Chen et al (72) found that nibrin (NBS1) lactylation

markedly enhanced DNA repair efficiency. This enhanced genomic

maintenance capability indirectly supports immune escape.

In summary, lactylation orchestrates immune evasion

by constructing a multi-tiered immunosuppressive network through

reprogramming TAM functionality, suppressing effector T cell

activity, activating inhibitory immune cells (Tregs, MDSCs and

PD-L1+ neutrophils), and bolstering tumor cell intrinsic

resistance (via enhanced DNA repair). This highlights lactylation

as a central metabolic-epigenetic mechanism underpinning tumor

immune evasion, providing a compelling rationale for therapeutic

strategies targeting lactylation to enhance immunotherapy

efficacy.

Tumor phenotypic plasticity

Lactylation serves as a central metabolic-epigenetic

coupling hub that simultaneously drives genomic instability,

non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming and phenotypic plasticity.

This dynamic adaptive capacity enables tumor cells to overcome

differentiation barriers and acquire hallmark malignant progression

capabilities under microenvironmental stress.

Lactylation in genome instability and

mutation

Genomic mutations fundamentally involve alterations

in DNA sequences, including nucleotide

additions/substitutions/deletions, single/double-strand breaks and

structural rearrangements such as translocations, duplications or

deletions.

Chen et al (73) demonstrated that MRE11 homolog,

double strand break repair nuclease (MRE11), a core nuclease in DNA

repair, undergoes robust lactylation catalyzed by the

acetyltransferase CBP. Lactylation at MRE11-K673 enhances MRE11-DNA

binding, thereby promoting DNA end resection and homologous

recombination repair. Epigenetic alterations notably impact genomic

stability through two primary mechanisms. DNA methylation

dysregulation is where aberrant hyper/hypomethylation at regulatory

regions can mimic mutational effects to drive carcinogenesis.

Additionally, histone modification-mediated chromatin remodeling is

where an altered chromatin architecture may induce chromosomal

rearrangements and instability, disrupting cell cycle progression

and checkpoint control. For example, p53 (the guardian of the

genome) maintains genomic integrity. Zong et al (74) identified AARS1 as a lactate sensor

and lactyltransferase that mediates global lysine lactylation in

tumor cells, targeting key proteins including p53. Beyond proteins,

lactylation may potentially occur on DNA/RNA sequences, analogous

to documented mRNA acetylation (75).

Lactylation and non-mutational

epigenetic reprogramming

Epigenetic reprogramming, alterations in gene

expression without changes in DNA sequence, serves fundamental

roles in development, differentiation and tissue homeostasis

(49). Within the TME, aberrant

conditions such as hypoxia and nutrient deprivation drive extensive

epigenetic modifications that enable cancer cells to acquire

hallmark malignant capabilities. Hypoxia-induced lactate

accumulation suppresses ten-eleven translocation demethylase

activity by reducing α-ketoglutarate levels (76). This leads to CpG island

hypermethylation and subsequent silencing of tumor suppressor gene

promoters (such as CDK inhibitor 2A), a mutation-independent

mechanism enriched in gliomas and CRC (63,77).

In IDH-mutant gliomas, lactylation-mediated metabolic dysregulation

further induces aberrant methylation of CCCTC-binding factor

insulators, reducing oncogene expression (such as PDGFRA) to drive

tumorigenesis. Stromal cells within the TME, including CAFs, innate

immune cells and endothelial cells, undergo non-genetic epigenetic

reprogramming upon recruitment to solid tumors, enhancing their

pro-tumorigenic functions. Lactate additionally facilitates cancer

cell migration by modulating integrin binding to extracellular

matrix components (78).

Furthermore, CAFs alter cancer cell NAD+/NADH ratios via

lactate shuttling, activating SIRT1-dependent PPARG coactivator 1a

to increase mitochondrial biogenesis and activity, thereby

remodeling cancer cell metabolism (79).

Lactylation and unlocking phenotypic

plasticity

The relationship between lactylation and tumor

phenotypic plasticity, an emerging cancer hallmark enabling

malignant progression through evasion of terminal differentiation,

remains incompletely elucidated (49). Phenotypic plasticity subverts normal

developmental processes wherein terminally differentiated cells

exit the cell cycle irreversibly, instead promoting

dedifferentiation (progenitor-like reversion), differentiation

blockade (progenitor-stage arrest) or trans-differentiation

(heterologous trait acquisition). Mechanistic evidence reveals

context-dependent functions. In BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma,

lactate accumulation induces lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A

(LSD1)-K503 lactylation, impeding tripartite motif-containing

protein 21-mediated degradation to stabilize LSD1-FosL1 complexes,

which suppress transferrin receptor transcription and confer

ferroptosis resistance, and this is reversed by LSD1 inhibitors

(80). GBM utilizes GTP

cyclohydrolase I-synthesized lactoyl-CoA to cooperate with p300,

driving H3K18la-mediated growth/differentiation factor 15

upregulation, and this sustains cancer stemness and radioresistance

(81).

Age-related macular degeneration models further

demonstrate that histone lactylation and alkB homolog 3,

a-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase-driven glycolysis form a

feedforward loop accelerating mesenchymal transition and fibrosis

(82). Beyond oncology, lactylation

remodels chromatin accessibility during embryonic stem cell

differentiation toward extraembryonic endoderm and coordinates

mesenchymal-epithelial transition in somatic reprogramming.

Notably, tissue-specific functional paradoxes exist; loss of

α-major histocompatibility complex-K1897 lactylation exacerbates

heart failure in cardiomyocytes (83), while neuronal arrestin b1-K195

lactylation induces S100A9-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis

(84).

These opposing outcomes underscore the

microenvironmental context, including lactate gradients and

substrate specificity, as determinants of the functional

directionality of lactylation. The spatiotemporal dynamics of

lactylation constitute a master regulator of phenotypic plasticity.

Future research should integrate high-resolution spatiotemporal

mapping (single-cell lactylome profiling across TME niches),

multi-omics dynamic modeling (lactylation-metabolism-oscillation

coupling) and context-specific delivery tools (precision

interventions) to elucidate the global roles of lactylation in TME

heterogeneity, cell fate decisions and therapeutic resistance,

providing novel paradigms to overcome plasticity-driven treatment

failure and metastasis.

Table I

systematically summarizes the lactylation sites, regulatory

mechanisms and clinical implications across key cancer hallmarks,

providing a comprehensive overview of its multifaceted roles.

| Table I.Lactylation hallmarks in cancer. |

Table I.

Lactylation hallmarks in cancer.

| Cancer

hallmark | Lactylation

site | Tumor type | Key

enzymes/regulators |

Pathway/mechanism | Clinical

function/impact | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 1. Metabolic

reprogramming | H3K18la | ccRCC | HIF, PDGFRβ | VHL loss → HIF

accumulation → lactate production → PDGFRβ activation → lactylation

↑ | Drives tumor

progression; poor prognosis | (50) |

|

| NUSAP1 K34 | PDAC | c-Myc, HIF-1α,

LDHA | TAM lactate →

NUSAP1 lactylation → LDHA transcription → glycolysis ↑ | Promotes

metastasis; therapy resistance | (51) |

| 2. Tumor growth and

metastasis | H3K56la | Liver cancer stem

cells | LDHA, p300 | Glycolysis ↑ →

lactate ↑ → H3K56la → stemness maintenance | Enhances

tumorigenicity; stemness | (53) |

|

| H3 lactylation | GBM | NF-κB | NF-κB → H3

lactylation → LINC01127 lncRNA → MAP4K4/JNK axis | Sustains cancer

stemness | (52) |

| 3. Angiogenesis

induction | HIF1α-K672la | Prostate

cancer | MCT1, HIF1α,

KIAA1199 | HIF1α lactylation →

KIAA1199 transcription → angiogenesis | Promotes vascular

mimicry; metastasis | (57) |

|

| NUSAP1 K34

(indirect) | PDAC | c-Myc, HIF-1α,

LDHA | NUSAP1 complex →

LDHA activation → lactate ↑ → angiogenesis | Drives

metastasis | (51) |

| 4. Polymorphic

microbiomes | H4K8la | CRC | YY1 | LPS → H3

lactylation at LINC00152 promoter → YY1 disruption → invasion | Promotes metastatic

dissemination | (60) |

| 5. Senescent

cells | H3K18la,

H3K27ac | HCC | GLIS1 | Glycolysis ↑ →

lactate ↑ → H3K18la/H3K27ac → chromatin relaxation | Facilitates

cellular reprogramming; immune evasion | (63,64) |

| 6. Tumor-Promoting

Inflammation | H3 lactylation |

Macrophages/TAMs | p300, SIRTs | Lactate → H3

lactylation → M2 polarization → VEGF/IL-10 secretion | Immunosuppression;

angiogenesis | (2,67) |

| 7. Evading immune

destruction | Moesin-K72la | Tregs | MCT1, LDHA,

LDHB | Lactylation →

moesin activation → TGF-β signaling ↑ → Treg suppression ↑ | Immune escape;

immunotherapy resistance | (44,100) |

|

| XRCC1-K247la | GBM | ALDH1A3, LDHA | Glycolysis ↑ →

XRCC1 lactylation → nuclear translocation → DNA repair ↑ |

Radio/chemoresistance | (71) |

|

| NBS1

lactylation | Pan-cancer | AARS1, LDHA

CBP | Lactylation →

enhanced DNA repair efficiency | Chemotherapy

resistance | (72) |

| 8. Genomic

instability | MRE11-K673la | Breast cancer |

| CBP-mediated

lactylation → MRE11-DNA binding ↑ → homologous recombination repair

↑ | Chemoresistance;

genomic instability | (73) |

| 9. Non-mutational

epigenetic reprogramming | Histone

methylation | Glioma, CRC | TET inhibition | Lactate ↑ → α-KG ↓

→ TET suppression → CpG hypermethylation (such as CDKN2A) | Silencing of

tumorsuppressors; therapy resistance | (76,77) |

| 10. Phenotypic

plasticity | LSD1-K503la | Melanoma | p300, GTPCS | Lactate → LSD1

lactylation → stabilization → TFRC suppression → ferroptosis

resistance | Targeted therapy

resistance | (80) |

|

| H3K18la | GBM | p300 | GTPCS → lactoyl-CoA

→ H3K18la → GDF15 ↑ → stemness/radioresistance | Radiation

resistance; recurrence | (81) |

Lactylation and cancer development

As research into lactylation progresses, evidence is

mounting that this modification, affecting both histones and

non-histone proteins, serves an oncogenic role across various

malignancies (85,86). Pan et al (87) demonstrated that LCSCs exhibited

higher lactylation levels compared with HCC cells. Lactate, as a

metabolic substrate, promotes histone lactylation, particularly at

H3K9la and H3K56la sites, driving LCSC proliferation and

tumorigenicity. Demethylzeylasteral, a triterpenoid from

Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F, curbs histone H3 lactylation

by inhibiting lactate production, thus restraining LCSC

proliferation, migration and inducing apoptosis.

In CRC, Li et al (88) revealed lactylation, especially

H3K18la, enhanced Rubicon like autophagy enhancer (RUBCNL) gene

transcription, associated with a worse CRC prognosis. Such

modifications boost RUBCNL/Pacer protein expression, crucial for

autophagosome maturation. This process aids cancer cell survival in

harsh conditions such as hypoxia. In renal cancer, Yang et

al (50) found a positive

association between lactylation and disease progression,

particularly in ccRCC. Inactive VHL triggers PDGFRβ transcription

via histone lactylation, driving ccRCC progression. PDGFRβ

signaling activation further stimulated histone lactylation,

creating a vicious cycle promoting ccRCC progression.

In bladder cancer, Xie et al (89) reported that the circular RNA,

circXRN2, suppressed cancer progression by activating the Hippo

signaling pathway, countering histone lactylation-driven cancer.

circXRN2 is downregulated in bladder cancer tissues and cell lines.

Its overexpression inhibited cancer cell proliferation and

migration, acting as a negative regulator of glycolysis and lactate

production. In thyroid cancer, Wang et al (90) noted enhanced glycolysis in BRAFV600E

mutation-positive thyroid cancers raised intracellular lactate

levels, promoting histone lactylation, especially at H4K12la. This

lactylation activated cell cycle regulation-related genes,

fostering thyroid cancer proliferation. In ocular melanoma, Yu

et al (91) found higher

lactylation levels in ocular melanoma tissues compared with in

normal melanocyte tissues, associated with early recurrence and

increased cancer invasiveness. Lactylation promoted cancer

formation by increasing N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 2

(YTHDF2) protein expression. YTHDF2 was shown to recognize

m6A-modified RNAs and accelerate the degradation of PER1 and TP53

mRNA, two cancer suppressor genes, expediting ocular melanoma

formation. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Jiang et

al (92) demonstrated that

lactate not only accumulates in lung cancer but was also associated

with cancer progression. Lactate adjusts the expression of specific

metabolic enzyme genes [such as hexokinase 1 and isocitrate

dehydrogenase [NAD(+)] (IDH) 3 non-catalytic subunit γ] by

increasing histone lactylation in their promoter regions, thereby

influencing NSCLC cell proliferation and migration.

Lactylation can both drive and suppress cancer. For

example, METTL16 lactylation in gastric cancer cells promoted m6A

modification on ferritin oxidoreductase protein 1 mRNA, inducing

copper death and curbing gastric cancer progression (93). In cervical cancer cells,

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) lactylation at K45 may

lower its binding affinity with NADP+, dampening G6PD

enzyme activity and inhibiting cancer cell proliferation (94). Lactate, as a metabolic byproduct,

can markedly suppress uveal melanoma (UM) cell proliferation and

migration, and alter cellular metabolism by increasing oxidative

phosphorylation. Lactate-treated UM cells exhibited higher

heterochromatin content and a quiescent state compared to untreated

controls, which correlated with reduced proliferation and

metastatic capacity (95).

As lactylation research deepens, its clinical

importance becomes more evident. Lactylation levels can predict

patient survival, prognosis and aid in disease diagnosis. In

pancreatic cancer, Peng et al (96) identified a set of

lactylation-related genes associated with pancreatic cancer

prognosis by combining RNA-sequencing data and clinical

information. A prognostic model based on lactylation was developed

using intersection analysis of differentially expressed genes and

lactate-associated genes, along with univariate and multivariate

Cox regression models. In breast cancer, lactate levels were

notably associated with the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI).

Grade III breast cancer tissues showed markedly higher lactate

levels compared with grade II tissues, and were positively

associated with the NPI but negatively with LDHA levels (97). In liver cancer, specific lactylation

sites on ubiquitin specific peptidase 14 (USP14) and ATP binding

cassette subfamily F member 1 proteins can serve as diagnostic

markers for liver cancer and its metastasis (98).

The current understanding of lactylation-driven

tumorigenesis remains fragmented, primarily due to unresolved

tissue-specific differences and insufficient clinical research.

While lactylation promotes tumorigenesis in most malignancies (such

as H3K9la/H3K56la-mediated stemness maintenance in LCSCs), it

suppresses metastasis in UM by inducing metabolic quiescence and

heterochromatinization.

This bidirectional regulation implies the existence

of a ‘lactylation threshold’, which is likely determined by the

microenvironmental lactate concentration, substrate specificity

(such as differential effects of H3K56la vs. mitochondrial targets)

and spatiotemporal dynamics, factors inadequately integrated into

current mechanistic models. Reported causal relationships lack

molecular verification: The antitumor effect of circXRN2 in bladder

cancer is attributed to activation of the Hippo pathway, yet its

association with the lactylation machinery (for example,

YAP/TAZ-mediated suppression of p300 lactyltransferase activity)

remains undetermined. RUBCNL-driven autophagy in CRC is described

as lactylation-dependent, but quantitative evidence linking lactate

flux to H3K18la levels at the RUBCNL promoter is lacking.

Furthermore, findings, such as USP14 lactylation as a liver cancer

biomarker, lack actionable diagnostic frameworks. The present

review proposes mapping lactylation modification thresholds by

integrating lactate biosensors (such as Laconic) with single-cell

lactylomics. To functionally assess specific lactylation sites

identified through this approach, CRISPR-dCas9-mediated

site-specific delactylation will be implemented, exemplified by

targeting H4K12la in thyroid cancer models. The diagnostic

potential of key lactylation marks will subsequently be evaluated

using tissue microarrays and receiver operating characteristic

curve analysis; for instance, comparing the diagnostic efficacy of

USP14-Kla vs. α-fetoprotein for detecting liver cancer

metastasis.

Lactylation and cancer therapy

Due to the growing evidence that lactylation is

positively associated with carcinogenesis, lactate producers or

lactate transporters, such as LDHA and MCT1/4, have been proposed

as novel targets for tumor therapy, either alone or in combination

with other anticancer strategies. In the present review, the role

of lactate in targeted therapy, traditional therapy and

immunotherapy is discussed.

Lactylation and targeted

therapies

Targeting lactylation has emerged as a promising

anticancer strategy, offering novel therapeutic avenues for drug

development. Current approaches focus on key nodes in lactate

metabolism, transport and modification. Peng et al (96) demonstrated that inhibiting solute

carrier family 16 member 1, a lactate transporter that is

upregulated in pancreatic cancer and associated with lactylation

levels, reduced intracellular lactate levels, suppressed

lactylation and inhibited tumor proliferation and migration.

Similarly, BRAFV600E inhibitors decreased glycolysis and

lactylation, inducing cell cycle arrest in thyroid cancer,

suggesting potential synergy with existing targeted therapies

through modulation of a glycolysis-lactylation axis (94).

LDHA, the key enzyme converting pyruvate to lactate,

represents another critical target. Its upregulation is associated

with a poor prognosis across several types of cancer. The

competitive inhibitor oxamate reduced cancer proliferation by

blocking glycolysis (99), while

gossypin directly inhibited LDHA activity, decreasing lactate

accumulation and promoting apoptosis (100). However, LDHA inhibitors face

notable limitations: Off-target effects and unpredictable side

effects from non-selective inhibition necessitate strategies to

improve drug specificity and a deeper mechanistic understanding.

Emerging agents aim to address these challenges through more

precise modulation. Simeprevir and oxamate inhibit LDHA to reduce

NBS1-K388 lactylation, whereas L-alanine competes with lactate for

AARS1 binding. These targeted approaches show notable potential for

advancing lactylation-based cancer therapies.

Lactylation and conventional

therapy

Tumor resistance remains a major barrier to

effective cancer therapy, with emerging evidence implicating

lactylation as a key mediator. Chen et al (73) demonstrated that MRE11 lactylation

enhances DNA-binding capacity, promoting homologous recombination

repair and chemoresistance in a lactate-abundant TME. Similarly,

NBS1 lactylation markedly increases DNA repair efficiency, while

XRCC1-K247 lactylation facilitated nuclear translocation to confer

chemo/radioresistance in GBM (71,72).

These findings establish lactylation as a promising therapeutic

target to overcome treatment resistance.

Proof-of-concept studies validate this approach; a

cell-penetrating peptide blocking MRE11-K673 lactylation sensitized

tumors to cisplatin and PARP inhibitors by inhibiting DNA repair

(73). Additionally, the small

molecule D34-919 disrupted an aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family,

member A3-pyruvate kinase M1/2 interaction, reducing lactate

production and XRCC1 lactylation, thus restoring radiosensitivity

in GBM (71). These targeted

strategies demonstrate that inhibiting specific lactylation events

can reverse treatment resistance mechanisms, providing a rational

foundation for combining lactylation-directed therapies with

conventional cancer treatments. Further investigations should focus

on optimizing lactylation-targeted agents for clinical

translation.

Lactylation and immunotherapy

Emerging evidence has established lactylation as a

pivotal epigenetic regulator of resistance to cancer immunotherapy.

Tumor-derived lactate drives immunosuppression within the TME

through lactylation-dependent mechanisms, including moesin-K72

lactylation, which enhances Treg immunosuppressive activity

(101). Critically, reducing TME

lactate levels improves anti-PD-1 efficacy, positioning lactate

modulation as a promising immunotherapeutic adjuvant (101). In HCC, lactate activates the

MCT1/NF-κB/cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) axis to generate

PD-L1+ neutrophils that mediate immune evasion, a

phenotype reversed by COX-2 inhibition with celecoxib, synergizing

with Lenvatinib (45). Similarly,

STAT5-driven glycolytic flux in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

elevates histone lactylation, upregulating PD-L1 and impairing

CD8+ T cell function. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade restores T

cell activity in STAT5-high AML models, supporting biomarker-guided

immunotherapy for glycolytic subtypes (102).

Pharmacological inhibition of lactate transport via

AZD3965 (an MCT1 inhibitor) disrupts immunosuppression and

attenuates tumor growth (103),

while genetic lactylation inhibition overcomes VEGF resistance in

CRC (88). These findings highlight

the therapeutic promise of dual-targeting lactylation pathways and

immune checkpoints. Current strategies targeting lactate synthesis

(LDHA inhibitors), transport (MCT blockers) and lactylation

modifiers require improved precision. Future efforts should

prioritize developing site-specific lactylation inhibitors and

combinatorial regimens leveraging metabolic-immune crosstalk.

Despite promising preclinical validation of the chemosensitizing

role of lactylation, translational challenges, including

tissue-specific dynamics and off-target effects, necessitate deeper

mechanistic exploration to improve clinical translation.

Current therapeutic strategies targeting lactylation

focused on three pillars: Disrupting lactate metabolism (LDHA/MCT

inhibition), reversing treatment resistance (blocking lactylation

of DNA repair proteins) and overcoming immunosuppression

(reprogramming Tregs/myeloid cells). However, notable challenges

remain in utilizing these approaches clinically. Firstly, the

mechanistic understanding in vitro and in animal models

often fails to translate effectively, as exemplified by LDHA

inhibitors paradoxically inducing protective autophagy, which

enhances drug resistance. Secondly, targeting specificity conflicts

with physiological complexity, as demonstrated by MCT1 inhibitor

AZD3965 simultaneously impairing T cell antitumor functions.

Thirdly, static interventions ignore the spatiotemporal

heterogeneity of lactylation dynamics, particularly regarding

optimal dosing windows. Notably, lactate metabolism targeting (such

as oxamate inhibiting LDHA) frequently overlooks compensatory

metabolic pathways. Resistance-reversal strategies (such as

targeting MRE11-K673la) lack tissue selectivity, risking collateral

damage to normal DNA repair mechanisms. Immunotherapy combinations

often disregard the dual regulatory roles of lactylation in the

TME, where suppressing Treg lactylation may destabilize immune

homeostasis.

Future research must advance toward dynamic

precision modulation: Developing spatiotemporally responsive

delivery systems (such as pH-sensitive nanocarriers with SIRT2

activators) to inhibit oncogenic lactylation (for example

MRE11-K673la) while sparing normal tissues; integrating multi-omic

biomarkers (such as plasma exosomal H3K18la or PET-based p300

activity tracing) for patient stratification and triple-targeting

(production-transportation-‘reader’) combination therapies; and

pioneering innovative tools such as CRISPR-dCas9-mediated

site-specific delactylation and microbiome-engineered bacteria

modulating gut lactylation. Collectively, these advances will

transition lactylation-targeted therapy from single-node inhibition

toward artificial intelligence-guided reprogramming of

epigenetic-metabolic networks, ultimately establishing curative

paradigms for cancer treatment.

Conclusions

Despite revealing the critical roles of lactylation

in tumor metabolic reprogramming, immune microenvironment

remodeling and resistance to therapy, three fundamental challenges

persist: i) An incomplete mechanistic understanding, exemplified by

tissue-specific functional contradictions (pro-tumorigenic vs.

suppressive effects); ii) technical limitations in capturing

dynamic modifications and discriminating D/L-lactylation isomers;

and iii) inadequate spatiotemporally precise intervention

strategies. Future breakthroughs require reconstructing research

paradigms through the following integrated approaches: i) Deepening

mechanistic insights by decoding lactylation context-dependent

regulatory logic (such as concentration-dependent modification

thresholds and substrate specificity) and quantifying

microenvironment-modification dynamics using metabolic gradient

organoid models; ii) advancing technical innovation through

single-cell spatiotemporal lactylomics and development of

isomer-specific probes for D/L-lactylation; and iii) developing

precision targeting via microenvironment-responsive delivery

systems (such as pH-responsive nanocarriers loaded with SIRT2

activators) to modulate specific effectors such as DNA repair

proteins (MRE11-K673la) or epigenetic regulators (H4K12la),

combined with metabolic-immune dual-targeting strategies (such as

MCT4 inhibitors + anti-PD-1) to overcome resistance. Only by

contextualizing lactylation within dynamic modification networks

can this biological concept transform clinical oncology

practice.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The funding was received from Lishui City Technology Application

Research Project (grant no. 2023GYX61) and Zhejiang Public Welfare

Technology Research Program (grant no. LGF21H160001).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YF drafted the manuscript and ZC revised the

manuscript. LD collected the literature and revised the manuscript.

JL designed the whole review and provided funding support. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wan N, Wang N, Yu S, Zhang H, Tang S, Wang

D, Lu W, Li H, Delafield DG, Kong Y, et al: Cyclic immonium ion of

lactyllysine reveals widespread lactylation in the human proteome.

Nat Methods. 19:854–864. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Qu J, Li P and Sun Z: Histone lactylation

regulates cancer progression by reshaping the tumor

microenvironment. Front Immunol. 14:12843442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Izzo LT and Wellen KE: Histone lactylation

links metabolism and gene regulation. Nature. 574:492–493. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Niu Z, Chen C, Wang S, Lu C, Wu Z, Wang A,

Mo J, Zhang J, Han Y, Yuan Y, et al: HBO1 catalyzes lysine

lactylation and mediates histone H3K9la to regulate gene

transcription. Nat Commun. 15:35612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rabinowitz JD and Enerbäck S: Lactate: The

ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metab. 2:566–571. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Brooks GA: The science and translation of

lactate shuttle theory. Cell Metab. 27:757–785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang W, Wang G, Xu ZG, Tu H, Hu F, Dai J,

Chang Y, Chen Y, Lu Y, Zeng H, et al: Lactate is a natural

suppressor of RLR signaling by targeting MAVS. Cell. 178:176–189.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jain M, Aggarwal S, Nagar P, Tiwari R and

Mustafiz A: A D-lactate dehydrogenase from rice is involved in

conferring tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses by maintaining

cellular homeostasis. Sci Rep. 10:128352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang H, Yang L, Liu M and Luo J: Protein

post-translational modifications in the regulation of cancer

hallmarks. Cancer Gene Ther. 30:529–547. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Millán-Zambrano G, Burton A, Bannister AJ

and Schneider R: Histone post-translational modifications-cause and

consequence of genome function. Nat Rev Genet. 23:563–580. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang Q, Cao L and Xu K: Role and

mechanism of lactylation in cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi.

27:471–479. 2024.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li F, Si W, Xia L, Yin D, Wei T, Tao M,

Cui X, Yang J, Hong T and Wei R: Positive feedback regulation

between glycolysis and histone lactylation drives oncogenesis in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 23:902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang Y, Wen J, Lou S, Han Y, Pan Y, Zhong

Y, He Q, Zhang Y, Mo X, Ma J and Shen N: DNAJC12 downregulation

induces neuroblastoma progression via increased histone H4K5

lactylation. J Mol Cell Biol. 16:mjae0562024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhang N, Jiang N, Yu L, Guan T, Sang X,

Feng Y, Chen R and Chen Q: Protein lactylation critically regulates

energy metabolism in the Protozoan Parasite Trypanosoma brucei.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7197202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mao Y, Zhang J, Zhou Q, He X, Zheng Z, Wei

Y, Zhou K, Lin Y, Yu H, Zhang H, et al: Hypoxia induces

mitochondrial protein lactylation to limit oxidative

phosphorylation. Cell Res. 34:13–30. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gao M, Zhang N and Liang W: Systematic

analysis of lysine lactylation in the plant fungal pathogen

botrytis cinerea. Front Microbiol. 11:5947432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yang Z, Yan C, Ma J, Peng P, Ren X, Cai S,

Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang S, Wang X, et al: Lactylome analysis suggests

lactylation-dependent mechanisms of metabolic adaptation in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Metab. 5:61–79. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hao B, Dong H, Xiong R, Song C, Xu C, Li N

and Geng Q: Identification of SLC2A1 as a predictive biomarker for

survival and response to immunotherapy in lung squamous cell

carcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 171:1081832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen Q, Yuan H, Bronze MS and Li M:

Targeting lactylation and the STAT3/CCL2 axis to overcome

immunotherapy resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J

Clin Invest. 135:e1914222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang J, Peng M, Oyang L, Shen M, Li S,

Jiang X, Ren Z, Peng Q, Xu X, Tan S, et al: Mechanism and

application of lactylation in cancers. Cell Biosci. 15:762025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Peng X and Du J: Histone and non-histone

lactylation: Molecular mechanisms, biological functions, diseases,

and therapeutic targets. Mol Biomed. 6:382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mi L, Cai Y, Qi J, Chen L, Li Y, Zhang S,

Ran H, Qi Q, Zhang C, Wu H, et al: Elevated nonhomologous

end-joining by AATF enables efficient DNA damage repair and

therapeutic resistance in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 16:49412025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Cui H, Xie N, Banerjee S, Ge J, Jiang D,

Dey T, Matthews QL, Liu RM and Liu G: Lung myofibroblasts promote

macrophage profibrotic activity through lactate-induced histone

lactylation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 64:115–125. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen Q, Yang B, Liu X, Zhang XD, Zhang L

and Liu T: Histone acetyltransferases CBP/p300 in tumorigenesis and

CBP/p300 inhibitors as promising novel anticancer agents.

Theranostics. 12:4935–4948. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Polich J: Updating P300: An integrative

theory of P3a and P3b. Clin Neurophysiol. 118:2128–2148. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xiao Y, Li W, Yang H, Pan L, Zhang L, Lu

L, Chen J, Wei W, Ye J, Li J, et al: HBO1 is a versatile histone

acyltransferase critical for promoter histone acylations. Nucleic

Acids Res. 49:8037–8059. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Moreno-Yruela C, Zhang D, Wei W, Bæk M,

Liu W, Gao J, Danková D, Nielsen AL, Bolding JE, Yang L, et al:

Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1-3) are histone lysine

delactylases. Sci Adv. 8:eabi66962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zu H, Li C, Dai C, Pan Y, Ding C, Sun H,

Zhang X, Yao X, Zang J and Mo X: SIRT2 functions as a histone

delactylase and inhibits the proliferation and migration of

neuroblastoma cells. Cell Discov. 8:542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jin J, Bai L, Wang D, Ding W, Cao Z, Yan

P, Li Y, Xi L, Wang Y, Zheng X, et al: SIRT3-dependent

delactylation of cyclin E2 prevents hepatocellular carcinoma

growth. EMBO Rep. 24:e560522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hu X, Huang X, Yang Y, Sun Y, Zhao Y,

Zhang Z, Qiu D, Wu Y, Wu G and Lei L: Dux activates

metabolism-lactylation-MET network during early iPSC reprogramming

with Brg1 as the histone lactylation reader. Nucleic Acids Res.

52:5529–5548. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang P, Lin K, Huang D, Jiang Z, Liao L

and Wang X: The regulatory role of protein lactylation in various

diseases: Special focus on the regulatory role of non-histone

lactylation. Gene. 963:1495952025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xu X, Wu X, Jin D, Ji J, Wu T, Huang M,

Zhao J, Shi Z, Zhou L, He X, et al: Lactylation: The regulatory

code of cellular life activity and a barometer of diseases. Cell

Oncol (Dordr). 16:10.1007/s13402–025-01083-4. 2025.

|

|

35

|

Sun Y, Wang H, Cui Z, Yu T, Song Y, Gao H,

Tang R, Wang X, Li B, Li W and Wang Z: Lactylation in cancer

progression and drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 81:1012482025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhu W, Fan C, Hou Y and Zhang Y:

Lactylation in tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy resistance:

New mechanisms and challenges. Cancer Lett. 627:2178352025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wan J, Liu H and Ming L: Lysine

crotonylation is involved in hepatocellular carcinoma progression.

Biomed Pharmacother. 111:976–982. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yuan H, Wu X, Wu Q, Chatoff A, Megill E,

Gao J, Huang T, Duan T, Yang K, Jin C, et al: Lysine catabolism

reprograms tumour immunity through histone crotonylation. Nature.

617:818–826. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dai SK, Liu PP, Li X, Jiao LF, Teng ZQ and

Liu CM: Dynamic profiling and functional interpretation of histone

lysine crotonylation and lactylation during neural development.

Development. 149:dev2000492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Feng J, Chen X, Li R, Xie Y, Zhang X, Guo

X, Zhao L, Xu Z, Song Y, Song J and Bi H: Lactylome analysis

reveals potential target modified proteins in the retina of

form-deprivation myopia. iScience. 27:1106062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Huang Y, Luo G, Peng K, Song Y, Wang Y,

Zhang H, Li J, Qiu X, Pu M, Liu X, et al: Lactylation stabilizes

TFEB to elevate autophagy and lysosomal activity. J Cell Biol.

223:e2023080992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Vaupel P and Multhoff G: The warburg

effect: Historical dogma versus current rationale. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1269:169–177. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K,

Tanegashima T, Lin YT, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Irie T, Okumura G, Kono

H, et al: Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T

cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell.

40:201–218. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Deng H, Kan A, Lyu N, He M, Huang X, Qiao

S, Li S, Lu W, Xie Q, Chen H, et al: Tumor-derived lactate inhibit

the efficacy of lenvatinib through regulating PD-L1 expression on

neutrophil in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer.

9:e0023052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Trimmer C,

Flomenberg N, Wang C, Pavlides S, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F

and Lisanti MP: Cancer cells metabolically ‘fertilize’ the tumor

microenvironment with hydrogen peroxide, driving the Warburg

effect: Implications for PET imaging of human tumors. Cell Cycle.

10:2504–2520. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liang L, Li W, Li X, Jin X, Liao Q, Li Y

and Zhou Y: ‘Reverse Warburg effect’ of cancer-associated

fibroblasts (Review). Int J Oncol. 60:672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: The hallmarks

of cancer. Cell. 100:57–70. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hanahan D: Hallmarks of cancer: New

dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12:31–46. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yang J, Luo L, Zhao C, Li X, Wang Z, Zeng

Z, Yang X, Zheng X, Jie H, Kang L, et al: A positive feedback loop

between inactive VHL-triggered histone lactylation and PDGFRβ

signaling drives clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression. Int J

Biol Sci. 18:3470–3483. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen M, Cen K, Song Y, Zhang X, Liou YC,

Liu P, Huang J, Ruan J, He J, Ye W, et al:

NUSAP1-LDHA-Glycolysis-Lactate feedforward loop promotes Warburg

effect and metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer

Lett. 567:2162852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Li L, Li Z, Meng X, Wang X, Song D, Liu Y,

Xu T, Qin J, Sun N, Tian K, et al: Histone lactylation-derived

LINC01127 promotes the self-renewal of glioblastoma stem cells via

the cis-regulating the MAP4K4 to activate JNK pathway. Cancer Lett.

579:2164672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Feng F, Wu J, Chi Q, Wang S, Liu W, Yang

L, Song G, Pan L, Xu K and Wang C: lactylome analysis unveils

lactylation-dependent mechanisms of stemness remodeling in the

liver cancer stem cells. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e24059752024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Sharma D, Singh M and Rani R: Role of LDH

in tumor glycolysis: Regulation of LDHA by small molecules for

cancer therapeutics. Semin Cancer Biol. 87:184–195. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Brown TP and Ganapathy V: Lactate/GPR81

signaling and proton motive force in cancer: Role in angiogenesis,

immune escape, nutrition, and Warburg phenomenon. Pharmacol Ther.

206:1074512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Haaga JR and Haaga R: Acidic lactate

sequentially induced lymphogenesis, phlebogenesis, and

arteriogenesis (ALPHA) hypothesis: Lactate-triggered glycolytic

vasculogenesis that occurs in normoxia or hypoxia and complements

the traditional concept of hypoxia-based vasculogenesis. Surgery.

154:632–637. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Luo Y, Yang Z, Yu Y and Zhang P: HIF1α

lactylation enhances KIAA1199 transcription to promote angiogenesis

and vasculogenic mimicry in prostate cancer. Int J Biol Macromol.

222:2225–2243. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Dzutsev A, Badger JH, Perez-Chanona E, Roy

S, Salcedo R, Smith CK and Trinchieri G: Microbes and cancer. Annu

Rev Immunol. 35:199–228. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Helmink BA, Khan MAW, Hermann A,

Gopalakrishnan V and Wargo JA: The microbiome, cancer, and cancer

therapy. Nat Med. 25:377–388. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wang J, Liu Z, Xu Y, Wang Y, Wang F, Zhang

Q, Ni C, Zhen Y, Xu R, Liu Q, et al: Enterobacterial LPS-inducible

LINC00152 is regulated by histone lactylation and promotes cancer

cells invasion and migration. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

12:9138152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Dong H, Zhang J, Zhang H, Han Y, Lu C,

Chen C, Tan X, Wang S, Bai X, Zhai G, et al: YiaC and CobB regulate