Introduction

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is a

malignant tumor arising from the renal epithelium, accounting for

~85% of RCC cases (1). Compared

with other RCC subtypes, ccRCC is characterized by enhanced

invasion capacity and poorer prognosis (2). The latest grading system, developed

jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and International

Society of Urology, categorizes ccRCC into four grades (I–IV).

Grades I and II are considered low-grade tumors with a favorable

prognosis, while grades III and IV are characterized as high-grade

tumors associated with poor prognosis (3). Minimally invasive treatment

approaches, such as nephron sparing surgery, ablation, and even

active monitoring, are more suitable for the management of

low-grade ccRCC, while high-grade ccRCC can require radical surgery

(4). Currently, preoperative biopsy

remains the gold standard for the pathological grading of ccRCC.

However, biopsy is an invasive procedure that carries several

risks, such as dissemination and sampling errors (5). Therefore, non-invasive and accurate

grading of ccRCC using imaging techniques has emerged as a

prominent research direction in recent years.

It has been reported that magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) can reveal several tumor characteristics, including tumor

size, necrosis, bleeding, enhancement pattern, and venous

thrombosis (4,6). However, MRI still lacks sufficient

information to aid radiologists in distinguishing the pathological

grade of ccRCC (7).

Radiomics is a science field that involves the

extraction, analysis, and interpretation of quantitative imaging

parameters. It utilizes computer-based post-processing technology

to convert medical images into high-dimensional and quantitative

imaging features. Utilizing model-building algorithms, these

imaging features can be associated with tumor tissue pathology and

heterogeneity, thus offering valuable insights for tumor

classification and grading, gene localization, as well as early

prediction of treatment response (4). Deep learning (DL) algorithms, a form

of radiomics, automatically learn and extract intricate patterns

and features from data via multi-level neural network models, thus

enabling efficient data analysis, prediction, and decision-making

(8). Currently, the association

between diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and diffusion kurtosis

imaging (DKI) parameters and the pathological grade of ccRCC has

been extensively studied (2,9–14).

However, research on MRI-based DWI and DKI-based DL models for

predicting the pathological grade of ccRCC remains limited.

Therefore, the present study aimed to validate a DL

model based on MRI data for predicting the pathological grading of

ccRCC prior surgery.

Materials and methods

Patients

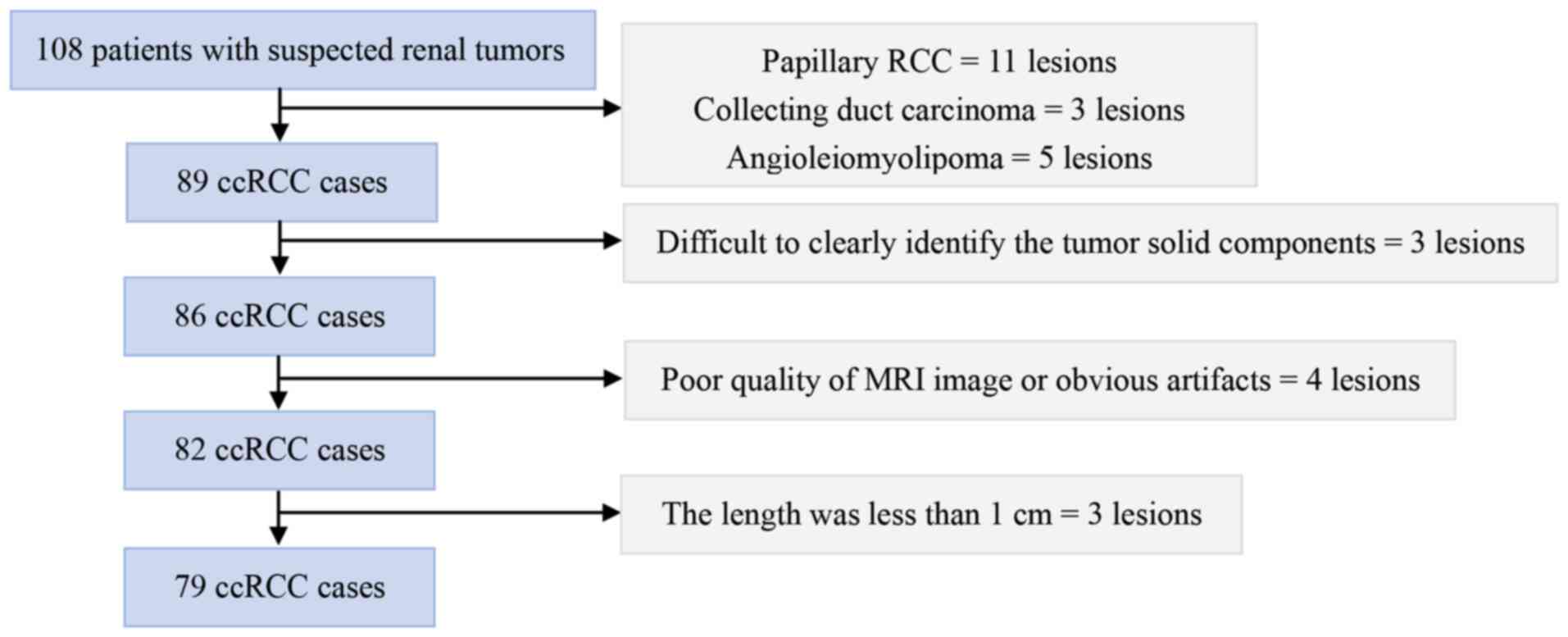

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of Zibo Central Hospital (approval no. 2017001), and all

patients provided signed written informed consent prior to

undergoing any examinations. The analysis included patients with

histologically confirmed ccRCC, who were treated at Zibo Central

Hospital between March 2017 and November 2021. A total of 108

patients with suspected renal tumors underwent MRI scan 1–2 weeks

prior to surgery. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Pathologically confirmed ccRCC via postoperative histologic

examination; ii) MRI protocol including both DWI and DKI; and iii)

no prior history of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or percutaneous

biopsy prior to renal MRI scanning. The exclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Pathologically confirmed non-ccRCC (such as papillary

RCC, collecting duct carcinoma, angioleiomyolipoma, etc.); ii)

Renal MRI protocol lacking DWI or DKI, with incomplete imaging

data; iii) A history of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or percutaneous

biopsy prior to renal MRI scanning; iv) Poor quality of MRI images

with obvious artifacts that interfere with the observation and

analysis of lesions; v) ccRCC lesions that are too small, in

special locations, or with other characteristics that make accurate

imaging classification or parameter measurement impossible.

Finally, a total of 79 patients with ccRCC were enrolled in the

current prospective study. In addition, a total of 19 patients were

excluded from the study due to non-ccRCC pathological types,

including papillary RCC (n=11), collecting duct carcinoma (n=3),

and angioleiomyolipoma (n=5). Among patients diagnosed with ccRCC,

three were excluded because the solid components of the lesions

were difficult to identify, four were excluded due to poor MRI

image quality or significant artifacts, and three were excluded

since the lesion size was <1 cm in length. The inclusion and

exclusion criteria are listed in Fig.

1.

MRI acquisition

All MRI examinations were carried using a 3-Tesla

(T) scanner (Signa™ HDx; GE Healthcare) and a commercial 16-channel

torso phased-array coil positioned at the renal level. All patients

underwent respiratory training prior to MRI examinations and were

scanned to the supine, feet-first position. Each patient was

subjected to two MRI sequence types, namely DWI and DKI. DWI was

carried out using a single-shot echo planar imaging sequence in the

axial plane, also incorporating imaging technology, and

respiratory-triggered acquisition, with b value of 0,800

s/mm2, a field of view (FOV) of 410 mm, and repetition

time (TR)/echo time (TE) of 5,400/64 ms. The layer thickness was

5.0 mm with 1.0-mm overlap, while a total of 19 slices were

acquired. Finally, 128×128 matrix images were produced, with a

total collection time of 1 min. For DKI, a single-shot echo planar

imaging sequence in the axial plane with respiratory-triggered

acquisition was performed. DKI images were captured with 30

diffusion gradient directions with three different b values for

each direction (0, 1,000, and 2,000 s/mm2). The

remaining MRI parameters were as follows: a FOV of 410 mm, TR/TE of

5,500/85 ms, and slice thickness of 5.0 mm with a 1.0-mm overlap.

The image matrix was 128×128 with a collection time of

approximately 3 min and 7 sec. The center level of the DKI was the

same as that of DWI. Finally, the raw data from the DWI and DKI

were transferred and processed using Functool software on the

Advantage Workstation (release 4.5). For DWI, apparent diffusion

coefficient (ADC) maps were generated, while for DKI, axial

kurtosis (Ka), fractional anisotropy (FA), radial kurtosis (Kr),

mean kurtosis (MK), and mean diffusivity (MD) maps were

calculated.

Image processing

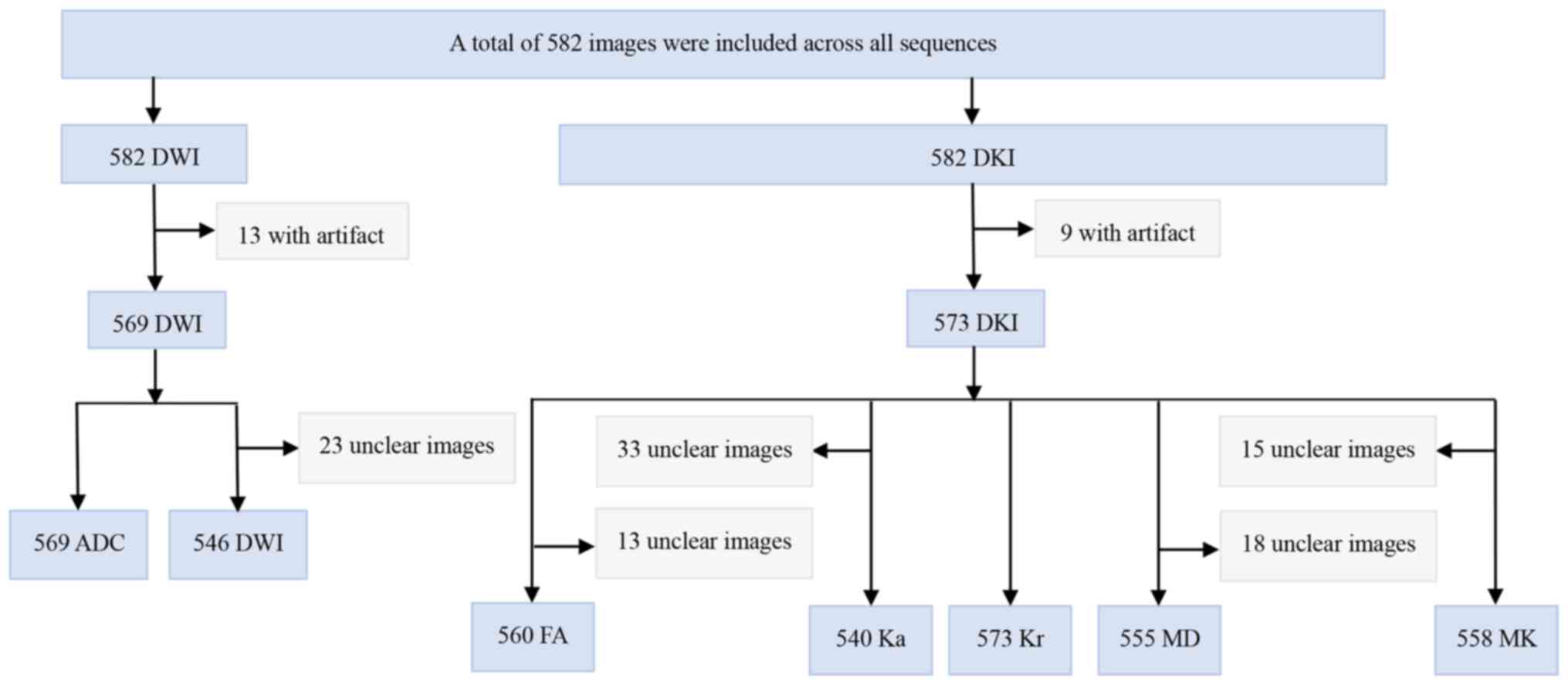

A total of 569 ADC images, including 385 in the

training set and 184 in the test set, were acquired. The program

effectively processed all 569 ADC images. For the DKI/FA scans, a

total of 560 images, 363 in the training set and 197 in the test

set, were captured, which were all successfully read by the

program. In addition, for the DKI/Ka scans, there were a total of

540 effectively read images, with 351 in the training set and 189

in the test set. The DKI/Kr scans totaled 573 images, comprising

365 and 208 in the training and test sets, respectively. All images

were also successfully read by the program. Similarly, the DKI/MD

scans consisted of 555 effectively read images (363 in the training

set and 192 in the test set). For the DKI/MK scans, 558 images, 361

in the training set and 197 in the test set, were included, which

were all also successfully accessed. Finally, the DWI scans

consisted of 546 images, with 377 in the training set and 169 in

the test set, all of which were effectively read. The potential

reasons for inconsistencies among the different parameter maps are

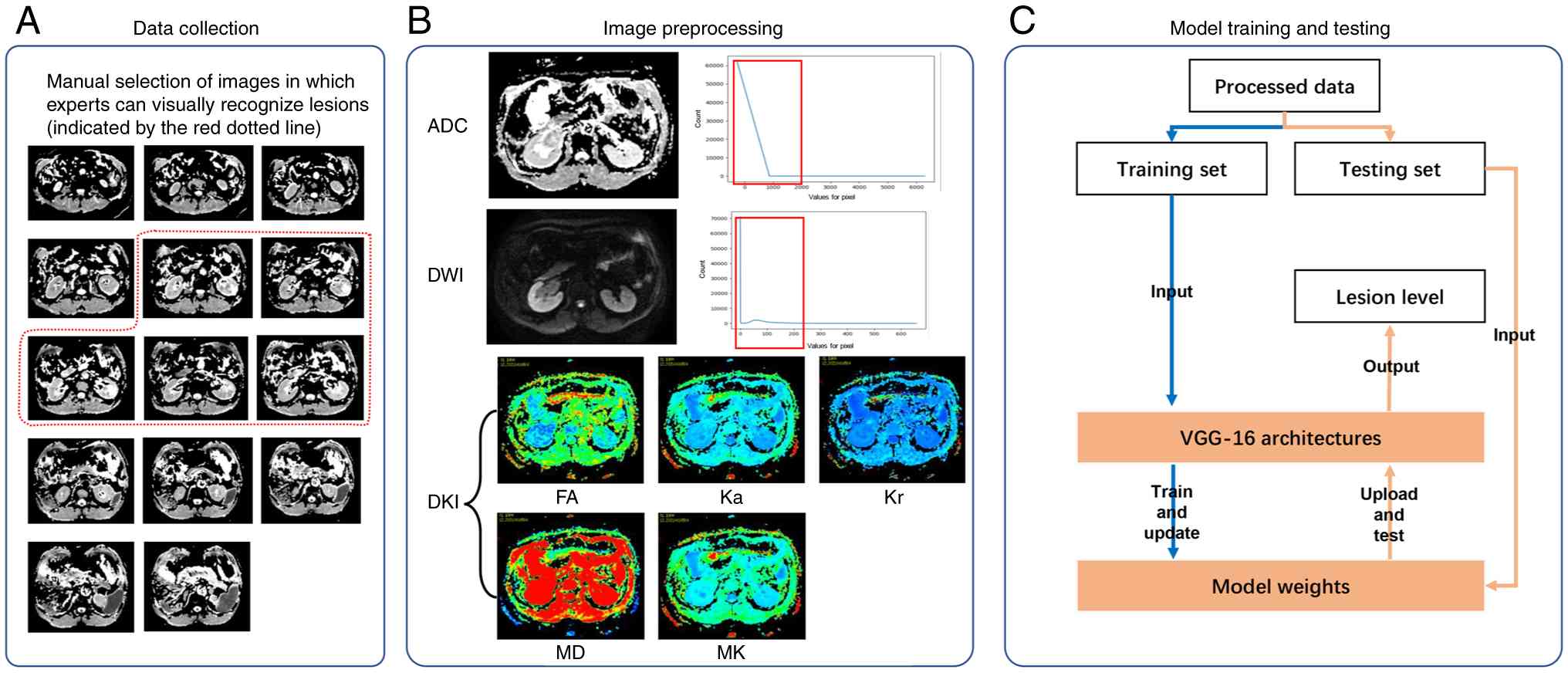

illustrated in Fig. 2.

Data processing

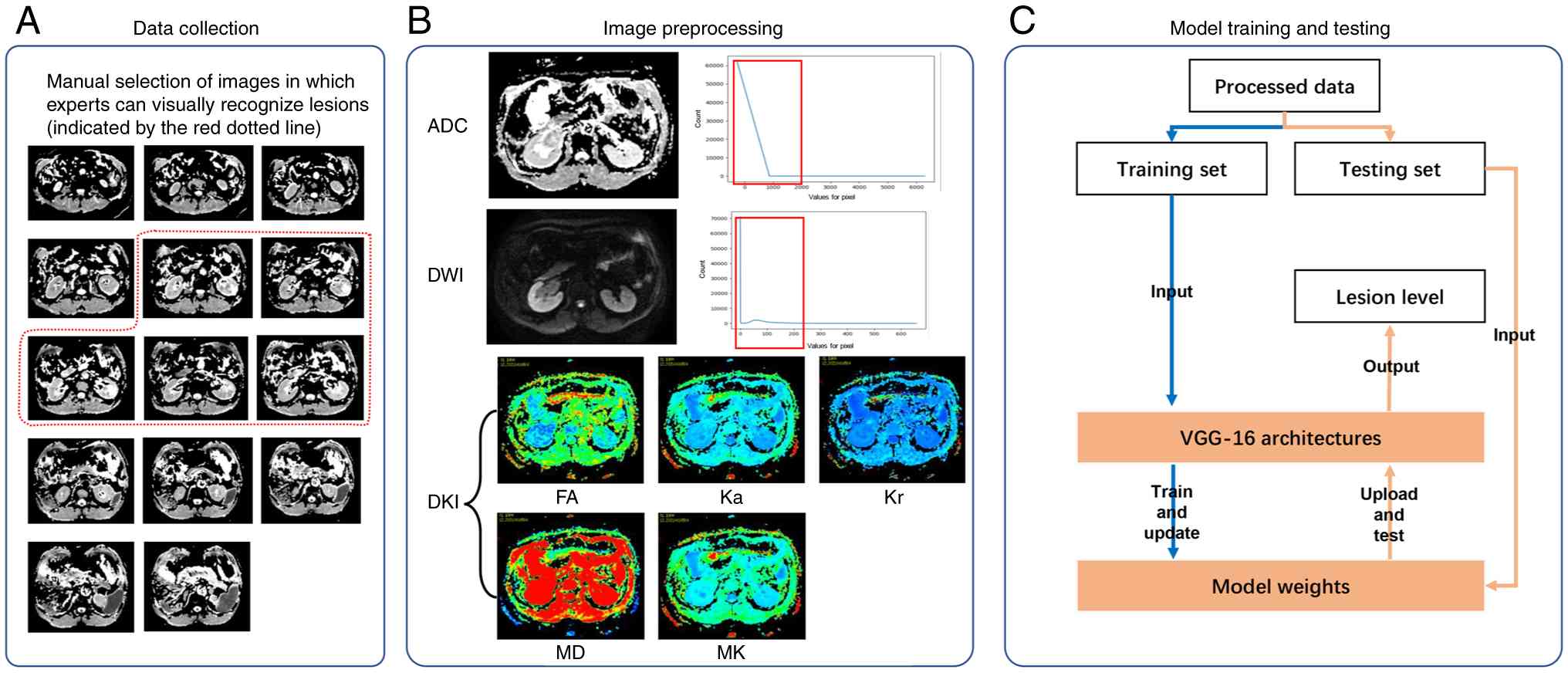

During the collection of DWI mono-exponential mode

images, it was noticed that ccRCC lesions were primarily observed

around the central slice (Fig. 3A),

while the remaining slices provided limited diagnostic value.

Therefore, the appropriate slices, from where experts could

visually identify lesions, were manually selected. The filtering

process was carried out by two professional radiologists. More

particularly, the one radiologist filtered all images, and the

second reviewed the filtering results. In case of possible

disagreement, the final decision was made through consultation. In

addition, frequency distribution maps of the ADC and DWI sequences

indicated that although the intensity of mono-exponential mode

images varied, the high-frequency intensities were mainly

concentrated within the low-value range (Fig. 3B). To normalize image intensity

among different exponential imaging modes, the high-frequency range

of the ADC and DWI sequences was scaled to [0, 255]. More

particularly, the effective intensity ranges of the ADC and DWI

sequences were [-256,500] and [0,120], respectively. The

DKI-derived sequences remained unchanged.

| Figure 3.Overview of data processing. (A) Data

collection, (B) image preprocessing, and (C) model training and

test. ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DKI, diffusion kurtosis

imaging; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; FA, fractional

anisotropy; Ka, axial kurtosis; Kr, radial kurtosis; MD, mean

diffusivity; MK, mean kurtosis. |

Model training and test

A supervised DL model was used to predict the

pathological grades of ccRCC based on the aforementioned data. As

shown in Fig. 3C, the training set

was used to optimize the model parameters and to update the model

weights. However, the optimal model weights were retained. During

the testing phase, model weights were accordingly loaded into the

model architecture to predict the lesion grades of the test

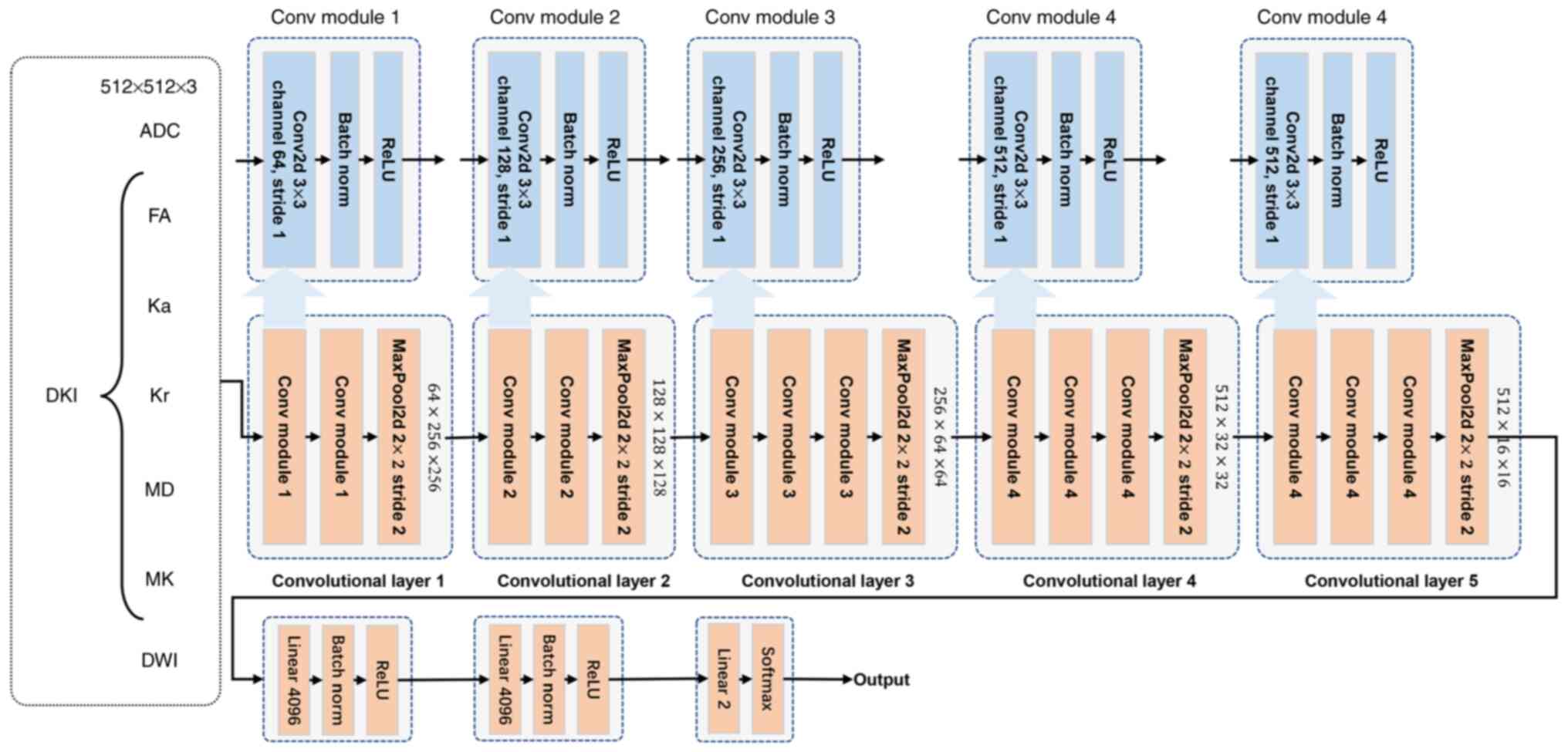

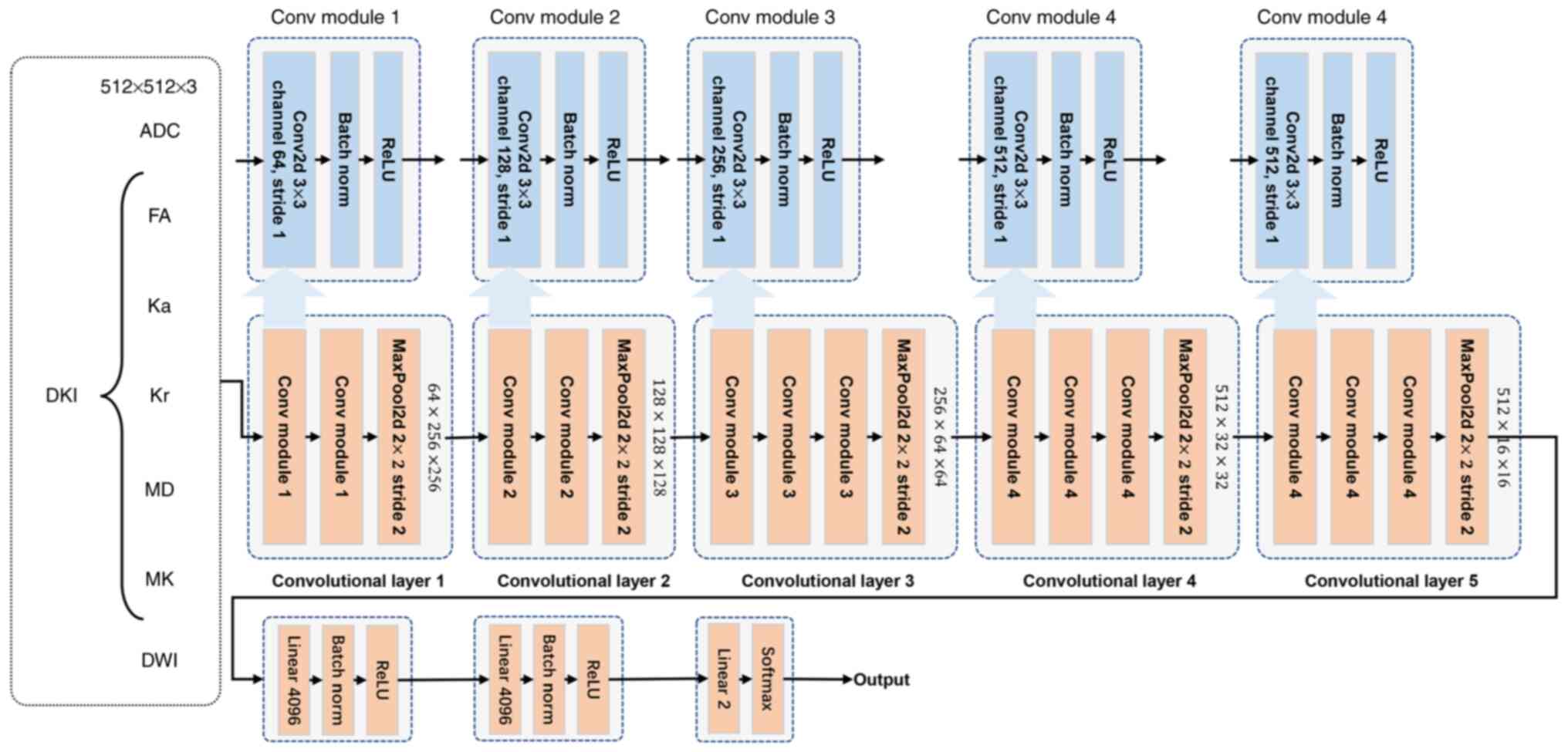

samples. The detailed model architecture is depicted in Fig. 4. Due to the limited data, the VGG-16

model was selected as the backbone architecture. The model

comprised of five convolutions and three linear classification

layers. The first two convolutional blocks consisted of two

convolutional modules, each including a convolution layer, a batch

normalization (BatchNorm) layer and a ReLU function module, and a

max-pooling layer. The remaining three convolutional layers

consisted of three convolutional modules and a max-pooling layer.

The number of convolutional channels were 64, 128, 256, 512, and

512 respectively. The classification layers primarily included a

linear-mapping layer, a BatchNorm module and a ReLU activation

module. In the present study, patients diagnosed with grade I and

II tumors were regarded as low-grade patients, marked as 0, while

those with grade III and IV tumors were classified as high-grade,

marked as 1. Therefore, the grading of ccRCC lesions was considered

as a binary classification problem. The final linear classification

channel was set to 2, followed by a softmax classification.

| Figure 4.Detailed model architecture. ADC,

apparent diffusion coefficient; DKI, diffusion kurtosis imaging;

DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; FA, fractional anisotropy; Ka,

axial kurtosis; Kr, radial kurtosis; MD, mean diffusivity; MK, mean

kurtosis; Conv, convolution; Conv2d, 2D convolution; MaxPool2d, 2D

max-pooling. |

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS

Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp.). The Shapiro-Wilk

test for normality and Levene's test for homogeneity of variances

were carried out on the age variable. Both tests verified that the

data met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance.

The differences in age between patients with low- and high-grade

ccRCC were compared utilizing an independent samples (unpaired)

t-test. The χ2 test was employed to compare the

differences in sex between low- and high-grade tumors. For tumor

side, Fisher's exact test was used instead, as the assumption of

expected counts for the χ2 test was not met. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

Based on the pathological results, a total of 79

patients with ccRCC were enrolled, including 40 cases of low-grade

disease (six cases of grade I and 34 cases of grade II) and 39

cases of high-grade disease (25 cases of grade III and 14 cases of

grade IV). The baseline clinical characteristics of the included

patients are listed in Table I.

Therefore, no statistical differences were obtained between

patients with low- and high-grade ccRCC.

| Table I.Baseline clinical characteristics of

the study cohort. |

Table I.

Baseline clinical characteristics of

the study cohort.

| Characteristics | Low-grade (grade I

and II; N=40) | High-grade (grade III

and IV; N=39) | T/χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Mean age ± SD, years

(range) | 57.25±13.04

(36–80) | 60.33±10.45

(27–79) | 1.158 | 0.250 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

| 1.764 | 0.241 |

| Male | 23 (57.5) | 28 (71.8) |

|

|

|

Female | 17 (42.5) | 11 (28.2) |

|

|

| Side, n (%) |

|

| 1.143 | 0.736 |

| Left | 19 (47.5) | 17 (43.6) |

|

|

|

Right | 20 (50.0) | 22 (56.4) |

|

|

| Both

sides | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

| Grade, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| I | 6 (15.0) | - |

|

|

| II | 34 (85.0) | - |

|

|

|

III | - | 25 (64.1) |

|

|

| IV | - | 14 (35.9) |

|

|

Model performance

The VGG-16 model was used for binary classification,

and the particular experimental results are presented in Table II. Among the investigated imaging

parameters, MK achieved the highest accuracy, followed by Kr and

Ka. The precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy values for MK

were 81.48, 76.04, 74.08, and 76.04%, respectively. In addition,

those for Kr were 75.51, 75.36, 75.42, and 75.36%, respectively.

Finally, for Ka the corresponding rates for precision, recall,

F1-score and accuracy were 81.39, 71.81, 68.31, and 71.81%,

respectively.

| Table II.Results of the binary classification

experiment for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. |

Table II.

Results of the binary classification

experiment for clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

| Imaging

parameter | Precision, % | Recall, % | F1-score, % | Accuracy, % |

|---|

| ADC | 69.96 | 69.32 | 65.99 | 69.32 |

| DKI/FA | 71.21 | 71.35 | 70.94 | 71.35 |

| DKI/Ka | 81.39 | 71.81 | 68.31 | 71.81 |

| DKI/Kr | 75.51 | 75.36 | 75.42 | 75.36 |

| DKI/MD | 78.13 | 71.74 | 65.36 | 71.74 |

| DKI/MK | 81.48 | 76.04 | 74.08 | 76.04 |

| DWI | 70.79 | 70.24 | 70.44 | 70.24 |

Discussion

The current study aimed to evaluate the

effectiveness of different MRI sequences for a binary DL model that

was established for the preoperative pathological grading of ccRCC.

Among the MRI-based approaches applied, DKI/MK displayed the

highest grading accuracy. The best-performing DL model showed

strong diagnostic performance, with accuracy and precision rates of

76.0 and 81.5% respectively. These results indicated that the DL

method was effective for ccRCC grading evaluation, thus offering an

non-invasive and valuable approach for ccRCC grading, and providing

a significant tool that could support clinicians in guiding

individualized treatment strategies. In recent decades, several

studies have investigated the association between DWI, DKI, and

radiomics, and the pathological grading of ccRCC, thus supporting

the increasing attention in this field.

DWI is a non-invasive method used to detect the

diffusion movement of water molecules within living tissues. The

net movement of water molecules can be quantified using the

apparent ADC value (15). It has

been reported that the ADC values of ccRCC tends to decrease as the

pathological grading increases (2,11). DKI

is an advanced functional MRI technology developed based on DWI,

incorporating a non-Gaussian model. This method is based on the

fact that water molecule diffusion in living tissues follows a

non-Gaussian distribution due to the effect of different factors,

such as cell membranes and intercellular organelles. DKI can

provide a more accurate assessment of microstructure changes via

calculating the deviation from the Gaussian distribution between

real and ideal diffusion states (2,16). The

kurtosis parameters of DKI include MK, Ka and Kr, while the

diffusion parameters include MD, FA, axial diffusivity, and radial

diffusivity (17).

MK represents the mean value of diffusion kurtosis

values measured in each direction. It serves as an average index of

the limitations experienced by water molecule diffusion within

tissues, thereby indirectly reflecting the complexity of the tissue

structure (12). Additionally, Kr

and Ka are used to elucidate tissue diffusion patterns in distinct

orientations, with Kr reflecting the mean kurtosis along the

principal axis of the diffusion tensor, and Ka perpendicular to the

principal axis. Both metrics are considered as indicative markers

of tissue complexity (18).

However, there are only a few reports on the

application of DKI in ccRCC classification. Wu et al

(14) explored the potential of DKI

in grading ccRCC among 91 patients. The results showed that MK

could more accurately grade ccRCC. These findings were consistent

with the results of the present study. In addition, Cao et

al (2) evaluated 89 patients

with confirmed ccRCC using DKI on a 3-T MRI scanner. Consistent

with the results of the current study, the above study reported

that MK exhibited the highest area under the curve (AUC).

In addition, Ye et al (13) utilized a 3.0-T MRI scanner to

examine 148 patients with ccRCC, using the DKI approach with three

b values (0, 1,000, and 2,000 s/mm2) and 30 diffusion

directions. The results demonstrated that the AUC value for MD was

the highest, thus suggesting that MD could be the most valuable

parameter for grading ccRCC using DKI. Similarly, Zou et al

(12) evaluated 108 patients with

confirmed ccRCC with DKI (b values, 0, 1,000, and 2,000

s/mm2) utilizing a 3.0-T MRI scanner. The results of

this study consistently showed that the MD values displayed the

highest diagnostic performance for ccRCC grading. Additionally, in

the study by Cheng et al (9), a total of 65 patients with

pathologically confirmed ccRCC were assessed using DKI sequences

with three b values (0, 500, 1,000 s/mm2), also using a

3.0-T MRI scanner. Therefore, this study also showed that MD values

exhibit a good diagnostic efficiency for ccRCC grading. However,

the results of the aforementioned studies were not consistent with

those observed in the current study. This could be due to the

following reasons: i) MK indirectly reflects the complexity of the

tissue structure, while MD characterizes the overall diffusion of

water molecules. In high-grade ccRCC, the presence of necrotic

areas can lead to increased restriction on water molecule

diffusion, potentially resulting in falsely enhanced MD values.

This could obscure the actual microstructural differences resulting

from cellular density and architectural disorders, thus

contributing to the superior performance of MK compared with MD;

ii) In the study by Cheng et al (9) a maximum b value of only 1,000

s/mm2 was employed, which could be suboptimal.

Rosenkrantz et al (10)

suggested that in order to ensure reliable results, the maximum b

value for kidney DKI should not be less than 1,500

s/mm2; and iii) In the aforementioned studies, including

the current one, the majority of patients with ccRCC undergone

radical or partial nephrectomy. Therefore, the number of cases with

high-grade and advanced ccRCC was relatively small, while the

sample size between the two groups was quite different, thus

introducing selection bias and affecting the comparisons between

groups.

Radiomics, a significant scientific field, is

associated with the extraction, analysis, and interpretation of

quantitative imaging parameters. It utilizes computer

post-processing technology to transform conventional imaging data

into high-dimensional and quantitative imaging data. Core

radiomic-related methods include texture analysis (TA), machine

learning (ML), and DL (4). TA is a

quantitative imaging technique that is used to extract additional

information from the grayscale distribution of pixels or voxels

within medical images, thus providing quantitative statistical

parameters (19). ML and DL,

subfields of artificial intelligence, primarily focus on developing

algorithms that can learn from and improve via data analysis

without requiring explicit programming in advance (20). ML models commonly use TA-derived

parameters as input features, thus enhancing the sensitivity of

medical imaging-mediated diagnosis (21). By contrast, DL models do not require

manual feature selection, as the algorithm itself can autonomously

determine which features are the most suitable for model

development (22). As a form of

radiomics, DL algorithm can automatically learn and extract complex

patterns and features from data via using multi-level neural

network models, thus enabling efficient data analysis, prediction

and decision making (8). Although

several studies have been conducted on the pathological grading of

ccRCC using MRI-based approaches (7,23,24),

to the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet employed the

DKI-based approach.

In a previous study, Pan et al (24) extracted MRI texture features from 89

patients with ccRCC. Therefore, conventional sequences, such as

T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), T2WI and contrast-enhanced T1WI

(CE-T1WI) were classified as conventional MRI (cMRI), while

Dixon-MRI, blood oxygen level-dependent MRI and SWI were classified

as functional MRI (fMRI). The accuracy rates of cMRI and fMRI were

49.56 and 70.80%, respectively. However, their approach primarily

relied on manually defined features, and therefore not all imaging

data could be captured. By contrast, DL can artificially outline

regions of interest (ROI), and automatically extract image

features, thus compensating for the lack of TA (23). Chen et al (7) combined T1WI, T2WI, CE-T1WI, and DWI

sequences to establish a ML model for the pathological grading of

ccRCC, including 99 patients. The training and validation

accuracies were 95.9 and 86.2%, respectively. However, ML depends

on manual mapping of ROIs, which can result in manual errors in the

boundary of the lesion. By contrast, DL can directly identify the

characteristics of the lesion from the model. In addition, Zhao

et al (23) used T1-enhanced

and T2WI sequences to establish DL models using data from 430

patients with ccRCC. The reported accuracy rates for T1 enhanced,

T2WI, and their combination were 71, 71, and 90%, respectively. In

the present study, the accuracy of the established DL model, using

the DKI/MK, DKI/Kr, DKI/Ka, DKI/FA, and DKI/MD parameters, was

higher compared with that reported for the individual sequence

model by Zhao et al (23).

Different pathological grades of ccRCC can be

associated with different surgical approaches and prognoses

(25,26). Currently, preoperative biopsy

remains the gold standard for determining the pathological grade of

ccRCC. However, biopsy is an invasive examination, which is

associated with particular risk factors, such as tumor seeding and

sampling error (5). By contrast, DL

models can predict the pathological grade of ccRCC under

non-invasive conditions, thus assisting clinicians in developing

personalized treatment strategies for patients with ccRCC.

However, this study has several limitations.

Firstly, the number of patients with ccRCC included in the study

was relatively small. Therefore, a multicenter study with a larger

patient cohort should be performed in the future. In addition, due

to the limited number of patients with grade I and IV ccRCC, binary

classification was employed. Future studies with more patients of

this grade and a four-classification approach should be considered

to improve the specificity of pathological grading.

Overall, the present study validated a DL-based

model using DWI and DKI imaging to accurately and non-invasively

distinguish between low- and high-grade ccRCC. Therefore, this

model could assist clinicians in guiding individualized clinical

treatment of patients with ccRCC under non-invasive conditions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JC and WZ conceived and designed the experiments.

XL, YaL, CX, ZD and WZ performed the experiments. KL, YuL, XS, DK

and PS analyzed the data. JC, CX and ZD contributed to the

provision of materials and analysis tools. YuL, XS and WZ confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was approved by the Medical

Ethics Committee of Zibo Central Hospital (approval no. 2017001;

Zibo, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients prior to enrollment.

Patient consent for publication

All patients or their next of kin consented to

publication of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Li Q, Zeng K, Chen Q, Han C, Wang X, Li B,

Miao J, Zheng B, Liu J, Yuan X and Liu B: Atractylenolide I

inhibits angiogenesis and reverses sunitinib resistance in clear

cell renal cell carcinoma through ATP6V0D2-mediated autophagic

degradation of EPAS1/HIF2α. Autophagy. 21:619–638. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cao J, Luo X, Zhou Z, Duan Y, Xiao L, Sun

X, Shang Q, Gong X, Hou Z, Kong D and He B: Comparison of

diffusion-weighted imaging mono-exponential mode with diffusion

kurtosis imaging for predicting pathological grades of clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Radiol. 130:1091952020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fan X, Fu F, Liang R, Xue E, Zhang H, Zhu

Y and Ye Q: Associations between contrast-enhanced ultrasound

features and WHO/ISUP grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A

retrospective study. Int Urol Nephrol. 56:1157–1164. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li Q, Liu YJ, Dong D, Bai X, Huang QB, Guo

AT, Ye HY, Tian J and Wang HY: Multiparametric MRI radiomic model

for preoperative predicting WHO/ISUP nuclear grade of clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 52:1557–1566. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Choi JW, Hu R, Zhao Y, Purkayastha S, Wu

J, McGirr AJ, Stavropoulos SW, Silva AC, Soulen MC, Palmer MB, et

al: Preoperative prediction of the stage, size, grade, and necrosis

score in clear cell renal cell carcinoma using MRI-based radiomics.

Abdom Radiol (NY). 46:2656–2664. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rizzo A, Racca M, Dall'Armellina S,

Rescigno P, Banna GL, Albano D, Dondi F, Bertagna F, Annunziata S

and Treglia G: The emerging role of PET/CT with PSMA-Targeting

radiopharmaceuticals in clear cell renal cancer: An updated

systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 15:3552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen XY, Zhang Y, Chen YX, Huang ZQ, Xia

XY, Yan YX, Xu MP, Chen W, Wang XL and Chen QL: MRI-based grading

of clear cell renal cell carcinoma using a machine learning

classifier. Front Oncol. 11:7086552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yasaka K, Kamagata K, Ogawa T, Hatano T,

Takeshige-Amano H, Ogaki K, Andica C, Akai H, Kunimatsu A, Uchida

W, et al: Parkinson's disease: Deep learning with a

parameter-weighted structural connectome matrix for diagnosis and

neural circuit disorder investigation. Neuroradiology.

63:1451–1462. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cheng Q, Ren A, Xu X, Meng Z, Feng X,

Pylypenko D, Dou W and Yu D: Application of DKI and IVIM imaging in

evaluating histologic grades and clinical stages of clear cell

renal cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 13:12039222023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rosenkrantz AB, Padhani AR, Chenevert TL,

Koh DM, De Keyzer F, Taouli B and Le Bihan D: Body diffusion

kurtosis imaging: Basic principles, applications, and

considerations for clinical practice. J Magn Reson Imaging.

42:1190–1202. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhu Q, Zhu W, Wu J, Chen W, Ye J and Ling

J: Comparative study of conventional diffusion-weighted imaging and

introvoxel incoherent motion in assessment of pathological grade of

clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Br J Radiol. 95:202104852022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zou J, Ye J, Zhu W, Wu J, Chen W, Chen R

and Zhu Q: Diffusion-weighted and diffusion kurtosis imaging

analysis of microstructural differences in clear cell renal cell

carcinoma: A comparative study. Br J Radiol. 96:202301462023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ye J, Xu Q, Wang SA, Zheng J and Dou WQ:

Quantitative evaluation of intravoxel incoherent motion and

diffusion kurtosis imaging in assessment of pathological grade of

clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Acad Radiol. 27:e176–e182. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu G, Zhao Z, Yao Q, Kong W, Xu J, Zhang

J, Liu G and Dai Y: The study of clear cell renal cell carcinoma

with MR diffusion kurtosis tensor imaging and its histopathologic

correlation. Acad Radiol. 25:430–438. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Meyer HJ, Martin M and Denecke T: DWI of

the Breast-possibilities and limitations. Rofo. 194:966–974. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li S, He K, Yuan G, Yong X, Meng X, Feng

C, Zhang Y, Kamel IR and Li Z: WHO/ISUP grade and pathological T

stage of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Value of ZOOMit diffusion

kurtosis imaging and chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging.

Eur Radiol. 33:4429–4439. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Duan Z, Tao J, Liu W, Liu Y, Fang S, Yang

Y, Liu X, Deng X, Song Y and Wang S: Correlation of IVIM/DKI

parameters with hypoxia biomarkers in fibrosarcoma murine models:

Direct control of MRI and pathological sections. Acad Radiol.

31:1014–1023. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Song Q, Dong W, Tian S, Xie L, Chen L, Wei

Q and Liu A: Diffusion kurtosis imaging with multiple quantitative

parameters for predicting microsatellite instability status of

endometrial carcinoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 48:3746–3756. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Litvin AA, Burkin DA, Kropinov AA and

Paramzin FN: Radiomics and digital image texture analysis in

oncology (review). Sovrem Tehnologii Med. 13:972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li D, Hu J, Zhang L, Li L, Yin Q, Shi J,

Guo H, Zhang Y and Zhuang P: Deep learning and machine

intelligence: New computational modeling techniques for discovery

of the combination rules and pharmacodynamic characteristics of

Traditional Chinese Medicine. Eur J Pharmacol. 933:1752602022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hügle T, Boedecker J, van Laar JM,

Boedecker J and Hügle T: Applied machine learning and artificial

intelligence in rheumatology. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 4:rkaa0052020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yousef R, Gupta G, Yousef N and Khari M: A

holistic overview of deep learning approach in medical imaging.

Multimed Syst. 28:881–914. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhao Y, Chang M, Wang R, Xi IL, Chang K,

Huang RY, Vallières M, Habibollahi P, Dagli MS, Palmer M, et al:

Deep learning based on MRI for differentiation of Low- and

High-Grade in Low-stage renal cell carcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging.

52:1542–1549. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Pan L, Chen M, Sun J, Jin P, Ding J, Cai

P, Chen J and Xing W: Prediction of Fuhrman grade of renal clear

cell carcinoma by multimodal MRI radiomics: A retrospective study.

Clin Radiol. 79:e273–e281. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li Y, Lih TM, Dhanasekaran SM, Mannan R,

Chen L, Cieslik M, Wu Y, Lu RJ, Clark DJ, Kołodziejczak I, et al:

Histopathologic and proteogenomic heterogeneity reveals features of

clear cell renal cell carcinoma aggressiveness. Cancer Cell.

41:139–163.e17. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Nezami BG and MacLennan GT: Clear cell

renal cell carcinoma: A comprehensive review of its histopathology,

genetics, and differential diagnosis. Int J Surg Pathol.

33:265–280. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|