Introduction

Wilms tumor (WT), also known as nephroblastoma, is

one of the most common malignant renal tumors in children, with an

incidence rate of ~7.1 cases per 100,000 children in the US

(1). In Asian populations, the

incidence is slightly lower, with China reporting an incidence rate

of approximately 2.5 cases per million children (2), accounting for >90% of all pediatric

renal malignancies (3). It may

affect a single kidney or occur bilaterally (4). Based on histological classification,

WT is divided into favorable histology (FH) WT, which comprises

~90% of cases, and anaplastic WT. The typical age of onset is

between 2–3 years, although it can occur in infants and in children

aged >10 years old (5). With

advances in imaging technologies and the adoption of

multidisciplinary treatment strategies, the survival rate of WT has

markedly improved, with a 5-year survival rate of >90% (6). However, a subset of patients still

experiences recurrence or metastasis after radical surgery, leading

to a poor prognosis and compromised long-term survival and quality

of life (7–9). Therefore, identifying prognostic

factors and establishing effective prediction models is essential

to improving treatment outcomes and long-term prognosis in

pediatric WT.

Over the past decades, research on WT has focused

primarily on genetics, molecular biology and clinical management.

Studies have reported that WT is closely associated with aberrant

expression of genes such as WT1, catenin β1 and WNT signaling

components (10,11). In addition, clinical stage, tumor

size, histological subtype and preoperative chemotherapy have been

identified as important prognostic factors (12–15).

Although numerous studies have explored the impact of these

factors, the findings remain inconsistent due to differences in

study populations, sample sizes and methodologies (16,17).

Therefore, further research is needed to clarify the prognostic

significance of these variables across diverse populations and to

develop multifactorial prognostic models that can guide clinical

decision-making more accurately and comprehensively.

The present study retrospectively analyzed the

clinical data of 180 pediatric patients with WT who underwent

radical nephrectomy at the Department of Surgical Oncology, Baoding

Branch of Beijing Children's Hospital (Baoding, China). The study

aimed to identify prognostic factors and to construct a predictive

model based on these variables, with the ultimate goal of providing

clinicians with valuable evidence to support more precise treatment

strategies and improve survival outcomes and quality of life for

children with WT.

Materials and methods

Study population

Clinical data were retrospectively collected from

pediatric patients with WT who underwent radical nephrectomy at

Baoding Branch of Beijing Children's Hospital between January 2015

and January 2019. Data sources included electronic medical records

and handwritten treatment documentation. To ensure data integrity

and consistency, all handwritten treatment records were

independently reviewed and cross-checked against corresponding

entries in the electronic medical record system by two trained

clinical researchers. Discrepancies, if identified, were resolved

through consensus review and, when necessary, verification with the

original source documents or consultation with treating physicians.

For cases with missing or incomplete data, predefined exclusion

criteria were applied to maintain the accuracy and completeness of

the dataset; patients with notable missing data were excluded from

the final analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Age

of <18 years; ii) histopathology-confirmed diagnosis of WT; iii)

radical nephrectomy performed; and iv) complete clinical data

available. The exclusion criteria included the following: i) No

pathological diagnosis or unclear pathology; ii) presence of a

second primary malignancy or hematologic disease; iii) notable

comorbid injury to other organs; and iv) incomplete medical

records.

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Baoding Branch of Beijing Children's Hospital

(approval no. H-BDETKJ-SOP006-03-A/2; project no. 2341ZF378).

Informed consent was obtained from the guardians of all patients

prior to treatment.

Postoperative adjuvant therapy

Diagnosis, staging and treatment for all patients

were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Children's

Oncology Group (COG)-Renal Tumor Committee and national protocols

developed by the Chinese Children Cancer Group (CCCG), including

CCCG-WT-2003 (18), CCCG-WT-2009

(19) and CCCG-WT-2015 (20). Stages I–II were defined as early

stage and stages III–IV as advanced stage. All patients received

standard postoperative therapy. The early-stage group was treated

with the vincristine + actinomycin D (EE4A) regimen. Vincristine

was administered via intravenous bolus on day 1 only, at a dosage

of 0.025 mg/kg for patients aged <1 year, 0.05 mg/kg for those

aged 1–3 years, and 1.5 mg/m2 (maximum 2.0 mg) for those

aged >3 years. Actinomycin D was administered via intravenous

infusion on day 1 only, at a dosage of 0.023 mg/kg for patients

aged <1 year and 0.045 mg/kg (maximum 2.3 mg) for those aged

>1 year. The total treatment duration was 19 weeks. The

advanced-stage group received the vincristine + actinomycin D +

doxorubicin (DD4A) regimen for 25 weeks, combined with radiotherapy

(180 cGy/day; 5 days/week). Vincristine was administered via

intravenous bolus on day 1 only, at a dosage of 0.025 mg/kg for

patients aged <1 year, 0.05 mg/kg for those aged 1–3 years and

1.5 mg/m2 (maximum 2.0 mg) for those aged >3 years.

Actinomycin D was administered via intravenous infusion on day 1

only, at a dosage of 0.023 mg/kg for patients aged <1 year and

0.045 mg/kg (maximum 2.3 mg) for those aged >1 year. Doxorubicin

was administered via intravenous infusion on day 1 only, at a

dosage of 1 mg/kg for patients aged ≤1 year and 30 mg/m2

for those aged >1 year.

Follow-up and outcome evaluation

Patients who completed WT treatment were followed up

every 3 months during the first and second postoperative years,

every 4 months in the third year, every 6 months in the fourth

year, and once in the fifth year. Follow-up frequency was further

individualized based on clinical stage at diagnosis. Specifically,

patients with advanced-stage disease (stage III–IV) underwent more

intensive monitoring during the first 2 postoperative years,

including clinical evaluations and imaging every 2 months during

the first year, and every 3 months during the second year. This

stage-adapted surveillance strategy was intended to facilitate

early detection of recurrence or metastasis. Follow-up examinations

included abdominal ultrasonography of the kidney, liver, spleen and

gallbladder, and chest X-rays (anteroposterior and lateral views).

Follow-up beyond the fifth year was not mandatory. Progression-free

survival (PFS) was defined as the interval from the date of radical

nephrectomy to the date of tumor recurrence or last follow-up.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery to death

from any cause or last follow-up. The median follow-up duration was

67 months (range, 29–101 months), with the cutoff date of follow-up

in July 2024.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM

Corp.). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2

test or Fisher's exact text, depending on the expected count in the

contingency table. PFS was used as the primary survival endpoint in

the present study, as it captures the time from treatment to

disease progression, recurrence or death. Moreover, whilst OS is an

important outcome, the small number of deaths (n=16) in the present

study limited the ability to performed an extensive OS analysis.

Therefore, PFS was used as the main survival measure. Survival

analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and

differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test.

Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional

hazards model. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were

generated, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to

evaluate model performance. All tests were two-sided, and P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Variables with P<0.05 in the univariate analysis were

prioritized for multivariate modeling; however, tumor thrombus was

intentionally retained due to its clinical relevance despite its

nonsignificant multivariable P-value.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

A total of 180 pediatric patients with WT were

included in the present study, comprising 114 male (63.3%) and 66

female (36.7%) patients. A total of 74 patients (41.1%) were aged

≤2 years and 106 (58.9%) were aged >2 years. The median age of

the patients was 3.3 years, with an age range of 0.5–8.5 years.

Clinical manifestations included abdominal mass in 107 (59.4%)

cases, hematuria in 34 (18.9%) cases and other symptoms in 39

(21.7%) cases. Clinical staging revealed 62 (34.4%) patients in

stage I, 53 (29.4%) patients in stage II, 61 (33.9%) patients in

stage III and 4 (2.2%) patients in stage IV. Histologically, 158

patients (87.8%) had FH, whilst 22 patients (12.2%) had unfavorable

histology (UFH). Additional clinical details are presented in

Table I.

| Table I.Univariate analysis of prognostic

factors in patients with pediatric Wilms tumor. |

Table I.

Univariate analysis of prognostic

factors in patients with pediatric Wilms tumor.

| Variable | Cases, n (%) | Recurrence cases, n

(%) | Total recurrence

rate, % | HR (95% CI) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤2 | 74 (41.1) | 10 (40.0) | 13.5 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

>2 | 106 (58.9) | 15 (60.0) | 14.2 | 1.253

(0.527–3.657) | 0.190 | 0.663 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 114 (63.3) | 15 (60.0) | 13.2 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Female | 66 (36.7) | 10 (40.0) | 15.2 | 1.051

(0.489–3.527) | 0.008 | 0.929 |

| Clinical

presentation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal mass | 107 (59.4) | 15 (60.0) | 14.0 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Hematuria | 34 (18.9) | 8 (32.0) | 23.5 | 1.124

(0.639–4.021) |

|

|

|

Other | 39 (21.7) | 2 (8.0) | 5.1 | 1.405

(0.695–3.963) | - | 0.104a |

| Hypertension |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 136 (75.6) | 20 (80.0) | 14.7 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 44 (24.4) | 5 (20.0) | 11.4 | 1.090

(0.578–2.957) | 0.012 | 0.912 |

| Tumor

laterality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left | 86 (47.8) | 13 (52.0) | 15.1 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Right | 94 (52.2) | 12 (48.0) | 12.8 | 0.954

(0.698–4.538) | 0.292 | 0.589 |

| Clinical stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I–II | 115 (63.9) | 5 (20.0) | 4.4 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

III–IV | 65 (36.1) | 20 (80.0) | 30.8 | 4.981

(2.515–9.634) | 20.852 | <0.001 |

| Tumor diameter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤5

cm | 72 (40.0) | 9 (36.0) | 12.5 | 1.000 |

|

|

| >5

cm | 108 (60.0) | 16 (64.0) | 14.8 | 1.263

(0.602–3.451) | 0.378 | 0.539 |

| Tumor volume |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤1,000

ml | 121 (67.2) | 16 (64.0) | 13.2 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

>1,000 ml | 59 (32.8) | 9 (36.0) | 37.3 | 1.327

(0.581–3.036) | 0.508 | 0.476 |

| Tumor rupture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 166 (92.2) | 22 (88.0) | 1.8 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 14 (7.8) | 3 (12.0) | 7.1 | 1.871

(0.723–5.063) | - | 0.443a |

| Lymph node

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 172 (95.6) | 24 (96.0) | 14.0 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 8 (4.4) | 1 (4.0) | 12.5 | 1.682

(0.762–6.309) | - | 0.032a |

| Tumor thrombus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 173 (96.1) | 21 (84.0) | 12.1 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 7 (3.9) | 4 (16.0) | 57.1 | 5.332

(2.354–9.658) | - | 0.032a |

| Histological

type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FH | 158 (87.8) | 14 (56.0) | 8.9 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

UFH | 22 (12.2) | 11 (44.0) | 50.0 | 5.658

(3.064–10.325) | 34.221 | <0.001 |

| Number of lymph

nodes dissected |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<7 | 13 (7.2) | 2 (8.0) | 15.4 | 1.000 |

|

|

| ≥7 | 167 (92.8) | 23 (92.0) | 13.8 | 1.136

(0.581–4.964) | - | 0.795a |

| Postoperative

chemotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 4 (2.2) | 1 (4.0) | 25.0 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 176 (97.8) | 24 (96.0) | 13.6 | 0.857

(0.519–3.725) | - | 0.482a |

| Postoperative

radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 114 (63.3) | 15 (60.0) | 13.2 | 1.000 |

|

|

|

Yes | 66 (36.7) | 10 (40.0) | 15.2 | 0.986

(0.693–3.928) | 0.334 | 0.564 |

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of prognostic factors

To identify prognostic factors following radical

surgery, univariate analysis was performed which revealed that

clinical stage, lymph node metastasis, histological subtype and the

presence of tumor thrombus were significantly associated with

prognosis (P<0.05; Table I).

Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that

advanced clinical stage [stage III–IV; hazard ratio (HR), 4.151;

95% confidence interval (CI), 1.440–11.922; P=0.009] and UFH (HR,

3.842; 95% CI, 1.592–9.283; P=0.002) were independent risk factors

for adverse outcomes (Table II).

Notably, tumor thrombus demonstrated the highest univariate HR of

5.332 (P<0.001) among all variables, although its effect size

decreased after adjustment for stage and histology in the

multivariate analysis (P>0.05).

| Table II.Multivariate cox regression analysis

of prognostic factors in pediatric Wilms tumor. |

Table II.

Multivariate cox regression analysis

of prognostic factors in pediatric Wilms tumor.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Clinical stage

(III–IV vs. I–II | 4.151 | 1.440–11.922 | 0.009 |

| Histological type

(UFH vs. FH) | 3.842 | 1.592–9.283 | 0.002 |

| Tumor thrombus | 2.284 | 0.731–7.186 | 0.156 |

| Lymph node

metastasis | 1.568 | 0.624.681 | 0.339 |

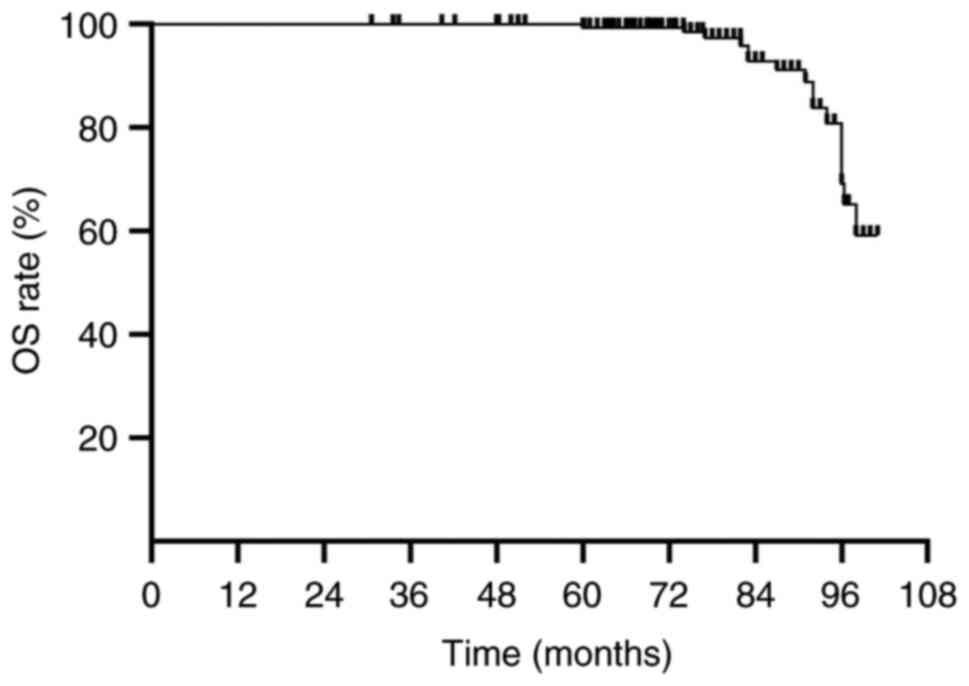

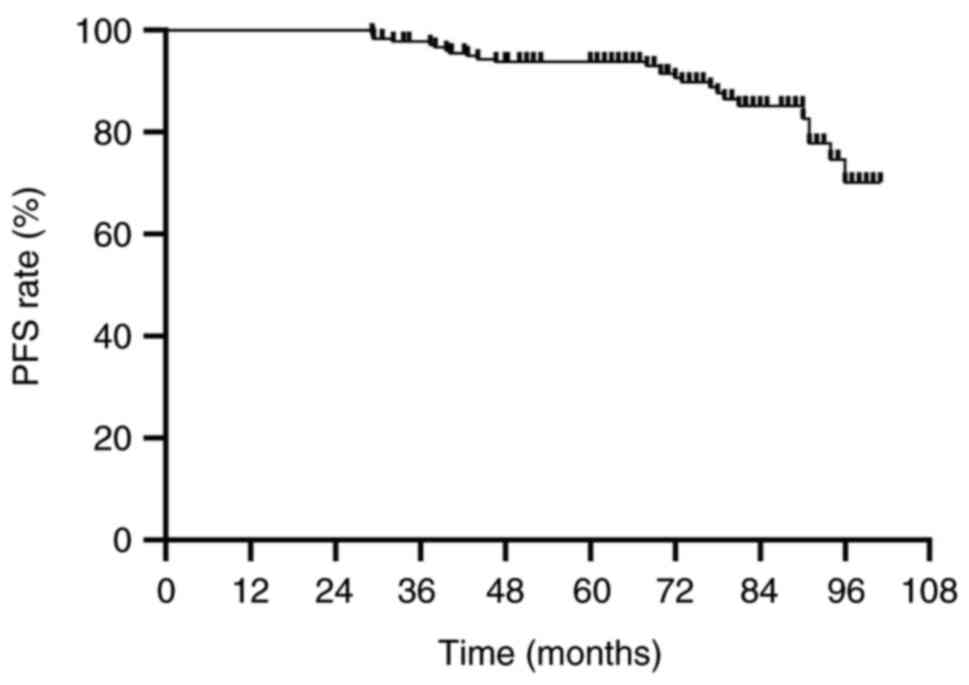

Prognostic outcomes

By the end of follow-up, 25 patients (13.9%)

experienced recurrence and 16 patients (8.9%) had died. The 5-year

OS rate was 99.6% and the 5-year PFS rate was 94.3%. The median OS

was 76.9 months (range, 30–101 months) and the median PFS was 75.5

months (range, 29–101 months) (Figs.

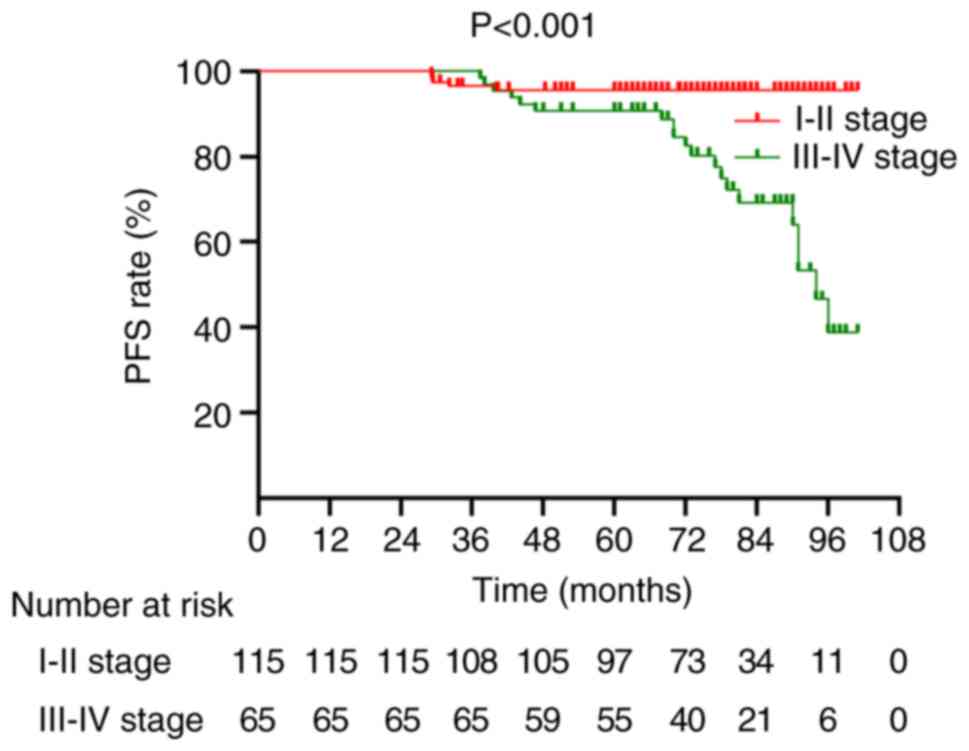

1 and 2). Further stratified

analysis revealed that patients with stage I–II WT had

significantly longer PFS than those with stage III–IV WT

(P<0.001; Fig. 3). Additionally,

despite more frequent follow-up in patients with advanced-stage

disease (stage III–IV), these patients still experienced

significantly lower PFS compared to those with early-stage disease

(P<0.001). This suggests that while increased surveillance may

facilitate earlier detection, it does not fully mitigate the impact

of more aggressive disease biology in advanced-stage Wilms tumor.

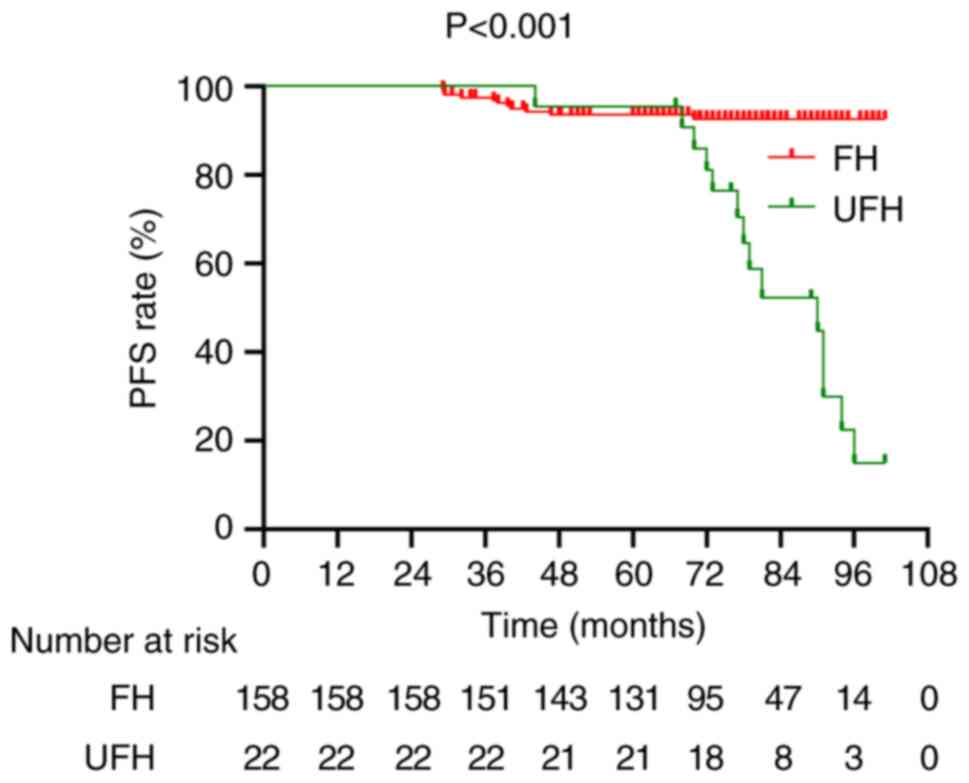

Similarly, patients with FH demonstrated significantly longer PFS

compared with those with UFH (P<0.001; Fig. 4).

Development of the predictive

model

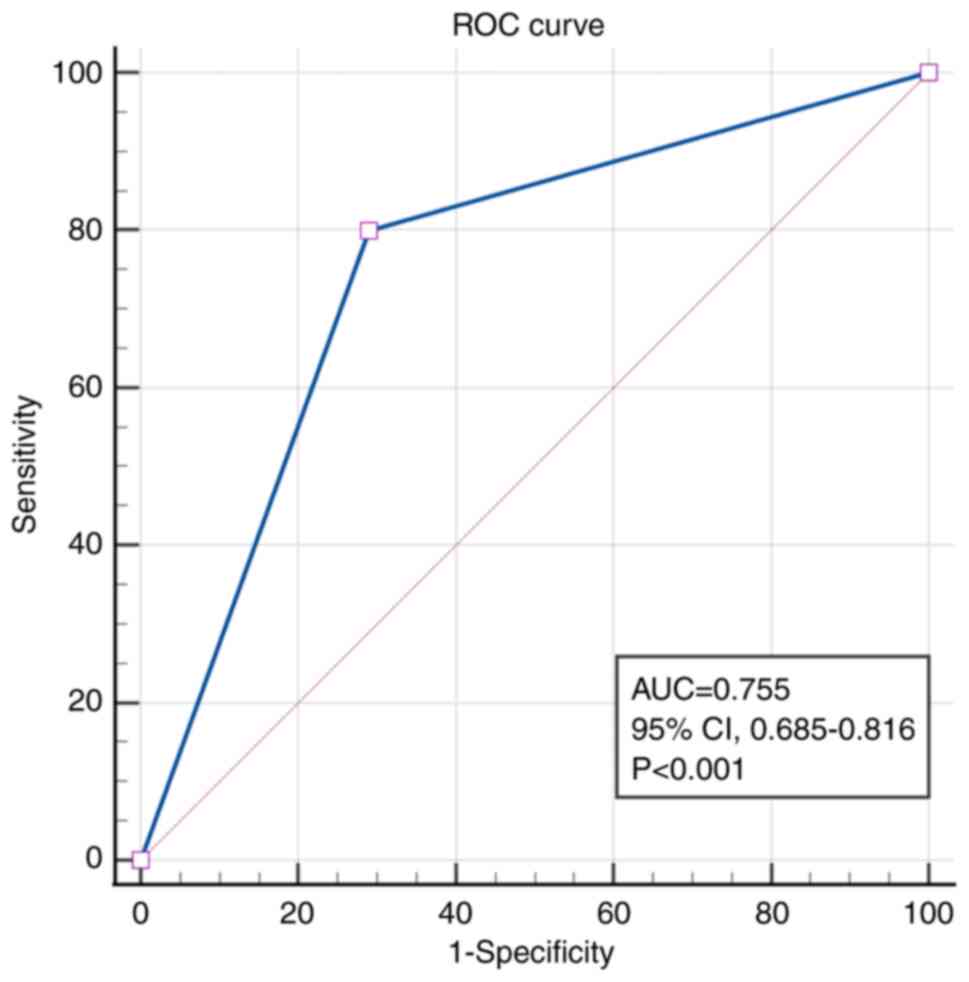

A prognostic model was developed based on clinical

stage and histological subtype. The discriminative performance of

the model was evaluated using ROC analysis, which yielded an AUC of

0.755 (95% CI, 0.685–0.816; P<0.001), indicating good predictive

accuracy (Fig. 5).

Discussion

WT is a common malignant renal tumor in children.

With the refinement of risk-adapted diagnostic and treatment

protocols developed by the COG and the International Society of

Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) (3,21),

long-term survival outcomes for WT have steadily improved, with

current 5-year OS rates reaching ~90% (6,22).

Nevertheless, ~15% of patients with FHWT still experience

recurrence or metastasis, leading to disease progression (13,23).

Accordingly, the present study aimed to analyze the clinical

characteristics and prognostic factors in patients with WT treated

at the Baoding Branch of Beijing Children's Hospital.

The present study primarily focused on PFS due to

its ability to comprehensively reflect disease progression,

recurrence, and death. The 5-year PFS rate was 94.3%, with a median

PFS of 75.5 months. Continued follow-up and expanded sample sizes

will be necessary to investigate factors influencing long-term

survival.

The selection of clinical stage and histological

subtype as core predictors was driven by three main criteria: i)

Statistical strength: Both factors demonstrated the highest HRs in

univariate analysis (stage III–IV HR, 4.981 and UFH HR, 5.658; both

P<0.001) and retained independence in multivariate modeling.

Other variables, such as tumor thrombus, became non-significant

when adjusted (adjusted P=0.154); ii) clinical feasibility: These

parameters are routinely confirmed within 48 h post-nephrectomy,

enabling rapid risk stratification according to COG/SIOP guidelines

(24); and iii) biological

relevance: Advanced stage reflects metastatic potential, whilst

anaplasia is associated with tumor protein P53-mediated treatment

resistance, which has been validated in prior studies (25–27).

Additionally, other clinical factors, such as tumor size and lymph

node involvement, were considered in the multivariate analysis.

Lymph node involvement showed statistical significance in the

univariate analysis and was therefore included in the multivariate

model. Whilst excluding these factors may limit the sensitivity of

the model in certain patient subgroups, focusing on clinically

relevant and easily obtainable variables allows for more practical

application in routine clinical settings.

In the present study, univariate factors

significantly associated with PFS included clinical stage,

histological subtype and tumor thrombus (P<0.05). Multivariate

Cox regression confirmed that stage III–IV disease (HR, 4.151; 95%

CI, 1.440–11.922; P=0.009) and UFH (HR, 3.842; 95% CI, 1.592–9.283;

P=0.002) were independent risk factors for PFS. However, as PFS was

the primary endpoint, competing risks, such as death from causes

other than WT or comorbid conditions, were did not explicitly

accounted for, which may affect survival outcomes. Whilst the small

number of deaths (n=16) limited the ability to perform detailed

competing risk analysis, it is acknowledged that such factors

should be considered in future studies. A more comprehensive

survival analysis, incorporating competing risks, would provide a

clearer picture of the influence of several factors on patient

survival and help refine prognostic models.

Tumor stage has been consistently identified as a

major prognostic determinant in WT. As all cases in the present

study underwent upfront surgery, clinical staging was defined

according to COG guidelines, where stage I–II is considered early

stage and stage III–IV as advanced stage. A national registry by

the Japan Wilms Tumor Study Group reported relapse-free survival

(RFS) rates of >90% for stages I–III but markedly worse outcomes

for stage IV (RFS, 66.2%) (28).

Similarly, combined analyses of the SIOP 93-01 and 2001 studies

reported that patients with stage III WT had a higher risk of

recurrence than those with stage I (29). In general, patients with

advanced-stage disease (III–IV) present with more extensive tumor

burden and consequently worse prognosis than those diagnosed at

earlier stages (30). Therefore,

early detection and accurate staging are critical to improving

outcomes in pediatric WT. Even in patients who undergo radical

nephrectomy, those with advanced-stage disease should receive

timely postoperative adjuvant therapy and close follow-up to

prevent recurrence. Whilst all patients in the present study

received standard postoperative therapy, treatment regimens varied

slightly based on individual patient characteristics, such as

disease stage, histological subtype and tumor size. Specifically,

patients with advanced-stage disease (stage III–IV) received the

more intensive DD4A regimen combined with radiotherapy, whereas

those with early-stage disease (stage I–II) were treated with the

EE4A regimen. These regimens differ in both the number of drugs and

the inclusion of radiotherapy, which was administered to

advanced-stage patients to address the higher risk of recurrence.

However, the potential impact of these differences on survival

outcomes was not fully analyzed in the present study. In future

studies, it would be valuable to explore how the interaction

between different treatment modalities (chemotherapy compared with

radiotherapy) and clinical variables, such as tumor size, stage or

histological subtype, influences survival outcomes. This could help

identify which patient subgroups benefit most from specific

treatment strategies and guide personalized treatment approaches.

Further analyses may also provide insight into whether certain

treatment regimens could be more effective for specific

histological types or tumor sizes, potentially improving patient

outcomes.

Histological subtype was also demonstrated to be a

crucial prognostic factor in the present study. Previous studies

have reported that patients with FHWT have notably improved

survival outcomes compared with those with UFH (31–33).

In the present study, patients with UFH had notably higher

recurrence and mortality rates. These tumors are typically more

aggressive and prone to relapse, potentially due to underlying

immunological and biochemical alterations such as oxidative and

glycoxidative stress responses (34).

In addition to histological factors, molecular

markers such as WT1 mutations and loss of heterozygosity at 1p/16q,

have emerged as notable prognostic indicators in WT. Although these

molecular data were not included in the present study due to data

limitations, future studies should explore their potential role in

refining prognostic models. The incorporation of genetic and

molecular data could enhance prognostic accuracy, provide a more

comprehensive understanding of tumor biology, and offer insights

into personalized treatment strategies. For example, WT1 mutations,

which are frequently associated with UFH and poor prognosis

(35), could serve as a powerful

predictor for treatment response and long-term outcomes. Therefore,

pathological assessment serves a pivotal role in risk

stratification and treatment planning.

Furthermore, individualized therapeutic approaches

based on histological subtype may improve patient outcomes. Whilst

the COG and SIOP risk stratification systems for WT are

well-established and widely used, the present study provided

important new insights that may enhance current risk stratification

and inform treatment strategies. Specifically, the following three

clinically actionable findings of the present study from a cohort

treated at a single center in China suggest the need for further

refinement of existing protocols. i) Higher incidence of stage III

disease: A total of 33.9% of patients presented with stage III

disease, compared with 28% reported in the SIOP 2001 trials

(36). This finding suggests

potential regional differences in disease aggressiveness, which may

influence the choice of treatment regimens and surveillance

strategies in different populations. ii) Tumor thrombus as a

prognostic factor: Although tumor thrombus was present in only 3.9%

of cases, it demonstrated a strong univariate association with

recurrence (57.1 vs. 12.1%; P<0.001). This highlights that the

presence of tumor thrombus, although rare, should be considered a

notable prognostic factor, particularly in cases of recurrence

risk. Whilst its prognostic significance was reduced after

adjusting for stage and histology, it still warrants consideration

in clinical decision-making. iii) Interaction between stage III–IV

and tumor thrombus: The data also suggested that the interaction

between stage III–IV disease and the presence of tumor thrombus

accounts for ~75% of thrombus-associated recurrences. This finding

indicates a synergistic risk escalation, suggesting that a more

personalized approach may be needed for patients with these

combined factors. These findings underscore the need for a more

nuanced approach to risk stratification for WT, one that considers

both regional differences in disease presentation and additional

prognostic factors not fully captured in existing models. Although

COG and SIOP provide robust guidelines, the findings from the

present study indicate that further refinements may be needed to

improve the accuracy of recurrence prediction and optimize

treatment strategies, particularly in populations with unique

disease patterns.

Based on clinical stage and histology, the present

study developed a predictive model for postoperative prognosis in

children with WT. The model demonstrated good discriminatory power,

with an area under the ROC curve of 0.755 (95% CI, 0.685–0.816;

P<0.001), supporting its clinical utility in forecasting

recurrence risk and guiding personalized management strategies.

From a clinical perspective, the predictive model based on clinical

stage and histological subtype offers a practical tool for early

postoperative risk stratification. Both variables are readily

available within 48–72 h following radical nephrectomy, allowing

clinicians to implement early decisions regarding surveillance

intensity and adjuvant treatment. For example, patients identified

as high-risk by the model (namely, stage III–IV and/or UFH) may

benefit from intensified imaging surveillance during the first 2

postoperative years, earlier initiation or escalation of

chemotherapy, or closer multidisciplinary follow-up. Notably, this

model complements, rather than replaces, existing risk

stratification systems such as those established by the COG. Whilst

COG guidelines provide protocol-driven treatment based on operative

and pathological findings, the model in the present study serves to

refine prognostic predictions post-surgery, particularly in

settings where clinical discretion is allowed (such as borderline

stage II/III cases or histologically ambiguous presentations).

Thus, integration of this model into routine clinical practice

could enhance individualized care by aligning early prognostic

assessment with standardized treatment protocols.

Further refinement of the model could include

additional clinical, molecular and genetic factors such as WT1

mutations, loss of heterozygosity at 1p/16q or other emerging

biomarkers. Incorporating these factors could potentially improve

the accuracy of the model and broaden its applicability,

particularly in genetically heterogeneous populations. Furthermore,

external validation was not performed using independent cohorts,

which is a crucial step to assess the robustness and

generalizability of the model in diverse clinical settings. Future

studies should aim to perform internal validation (such as

bootstrapping or k-fold cross-validation) as well as external

validation to refine and validate the predictive power of the model

in different clinical environments.

Moreover, the present study has several limitations.

First, it was a single-center retrospective analysis with a

relatively limited sample size, which may reduce the statistical

power and generalizability of the findings. An important

consideration for future studies is the potential impact of

postoperative complications, such as renal insufficiency,

infections or other treatment-related side effects. These

complications may negatively affect prognosis and overall survival

outcomes, particularly in children with WT who may experience

long-term treatment-related toxicities. Whilst these factors were

not specifically addressed in the current study due to data

limitations, future research should aim to evaluate the role of

postoperative complications in survival outcomes. Including such

factors in prognostic models could provide a more comprehensive

assessment of patient risk and guide individualized treatment

approaches. Whilst this approach ensures consistency in data

collection, the results may not fully reflect the broader pediatric

WT population, particularly with respect to regional or demographic

differences. For instance, variations in treatment protocols,

patient characteristics and disease prevalence across different

regions or institutions could influence outcomes. Therefore, the

external validity of these findings could be limited. To confirm

and validate the results of the present, future multicenter

studies, incorporating diverse patient populations from several

geographic regions, would be valuable. A larger and more

heterogeneous cohort would enhance the generalizability of the

model and improve its applicability to different clinical settings.

Second, the prognostic value of tumor thrombus requires cautious

interpretation due to small event numbers (n=7), although its

univariate significance aligns with emerging evidence from AREN03B2

trial sub-studies (37). Third, an

important aspect to consider in future studies is the use of

biomarkers in postoperative follow-up. Biomarkers such as

circulating tumor DNA, WT1 mutations, 1q gain and microRNAs have

shown promise as early indicators of recurrence or metastasis

(38,39). For example, 1q gain is associated

with more aggressive disease and worse prognosis in patients with

WT, making it an important biomarker for risk stratification

(40). Similarly, microRNA

expression changes can help predict disease progression and

outcomes (41,42). Additionally, prohibitin levels have

been reported to be associated with relapse in WT, highlighting its

potential as a non-invasive biomarker for monitoring recurrence

(43). Incorporating these

biomarkers into routine postoperative surveillance could improve

the accuracy of recurrence prediction and allow for more

personalized treatment strategies. Future research should focus on

validating the reliability and feasibility of these biomarkers in

clinical practice. Additionally, certain clinical variables, such

as tumor rupture timing and long-term treatment-related

complications (for example, cardiac or renal dysfunction), were not

fully captured. The reliance on a single data source may also

introduce selection and information biases, which are inherent in

retrospective studies and single-center data collection. Another

limitation is the potential for follow-up loss, as not all patients

could be consistently monitored for the entire follow-up period.

Additionally, variability in protocol adherence could affect the

consistency of treatment and outcomes. Furthermore, the study did

not incorporate genetic or molecular biomarkers, such as WT1,

1p/16q LOH and 1q gain, which have been identified as important

prognostic indicators in WT. The absence of these markers in the

current study was due to data limitations, including the

unavailability of genetic profiling for certain patients. Future

research should aim to include these molecular markers to improve

the prognostic accuracy of the model and improve the stratification

of patient risk. Finally, internal cross-validation (such as

bootstrapping or k-fold cross-validation) was not performed and

external validation cohorts were not used in the development of the

predictive model. This limitation may affect the robustness and

generalizability of the model. Future studies should incorporate

internal validation techniques and use independent cohorts to

enhance the accuracy and applicability of the model.

In conclusion, the present study primarily focused

on PFS as the key prognostic indicator, as it provides a useful

reflection of the risk of recurrence, progression and death in

patients with WT. Nevertheless, the findings of the present study

provide meaningful guidance for clinicians and offer a foundation

for future research. Future studies should incorporate additional

clinical and genetic factors to refine the predictive model

further. For instance, integrating molecular markers such as WT1

mutations, 1p/16q loss of heterozygosity or other genetic

alterations could markedly improve the accuracy of the model.

Furthermore, additional cohort studies, especially multicenter or

international studies, would help validate the findings of the

study and assess the robustness of the model across diverse

populations. Incorporating data from different clinical settings

and populations may enhance the generalizability of the model,

ensuring its applicability in routine clinical practice.

Furthermore, another important aspect that should be considered in

future studies is the assessment of long-term quality of life in

pediatric patients with WT. Whilst the present study focused on PFS

and OS, the impact of postoperative treatments, recurrence and

treatment-related side effects on the physical function, mental

health and social adaptation of patients is also crucial.

Incorporating quality of life assessments into future research

would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the treatment

impacts on the overall well-being of patients and help guide

personalized and holistic care. Through early diagnosis, accurate

staging, individualized treatment and comprehensive perioperative

management, the prognosis of children with WT can be substantially

improved. Moreover, the development of a multifactorial prognostic

model may facilitate more precise and evidence-based clinical

decision-making, ultimately enhancing survival and quality-of-life

in this patient population.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Baoding Municipal Science

and Technology Bureau (grant no. 2341ZF378).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HT and DM conceived and designed the study. HT

collected clinical data, performed the statistical analysis and

drafted the manuscript. BH, KS, HL, JW and JS contributed to data

interpretation and literature review. DM critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content and supervised the

overall project. HT and DM confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by

the Ethics Committee of the Baoding Branch of Beijing Children's

Hospital, Baoding Children's Hospital (approval no.

H-BDETKJ-SOP006-03-A/2). Written informed consent was obtained from

the legal guardians of all participating patients prior to

enrollment.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

WT

|

Wilms tumor

|

|

FH

|

favorable histology

|

|

UFH

|

unfavorable histology

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

RFS

|

relapse-free survival

|

|

HR

|

hazard ratio

|

|

CI

|

confidence interval

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

|

COG

|

Children's Oncology Group

|

|

SIOP

|

International Society of Paediatric

Oncology

|

|

CCCG

|

Chinese Children Cancer Group

|

|

EE4A

|

vincristine + actinomycin D

regimen

|

|

DD4A

|

vincristine + actinomycin D +

doxorubicin regimen

|

References

|

1

|

Doganis D, Panagopoulou P, Tragiannidis A,

Vichos T, Moschovi M, Polychronopoulou S, Rigatou E,

Papakonstantinou E, Stiakaki E, Dana H, et al: Survival and

mortality rates of Wilms tumour in Southern and Eastern European

countries: Socioeconomic differentials compared with the United

States of America. Eur J Cancer. 101:38–46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tan X, Wang J, Tang J, Tian X, Jin L, Li

M, Zhang Z and He D: A nomogram for predicting Cancer-specific

survival in children with wilms tumor: A study based on SEER

database and external validation in China. Front Public Health.

10:8298402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Vujanić GM, Gessler M, Ooms AHAG, Collini

P, Coulomb-l'Hermine A, D'Hooghe E, de Krijger RR, Perotti D,

Pritchard-Jones K, Vokuhl C, et al: The UMBRELLA SIOP-RTSG 2016

Wilms tumour pathology and molecular biology protocol. Nat Rev

Urol. 15:693–701. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Spreafico F, Fernandez CV, Brok J, Nakata

K, Vujanic G, Geller JI, Gessler M, Maschietto M, Behjati S,

Polanco A, et al: Wilms tumour. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 1:752021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jain J, Sutton KS and Hong AL: Progress

update in pediatric renal tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 23:332021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bahoush G and Saeedi E: Outcome of

Children with Wilms'tumor indeveloping countries. Med Life.

13:484–489. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chan CC, To KF, Yuen HL, Shing Chiang AK,

Ling SC, Li CH, Cheuk DK, Li CK and Shing MM: A 20-year prospective

study of Wilms tumor and other kidney tumors: A report from Hong

Kong pediatric hematology and oncology study group. J Pediatr

Hematol Oncol. 36:445–450. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Millar AJW, Cox S and Davidson A:

Management of bilateral Wilms tumours. Pediatr Surg Int.

33:737–745. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Dome JS, Graf N, Geller JI, Fernandez CV,

Mullen EA, Spreafico F, Van den Heuvel-Eibrink M and

Pritchard-Jones K: Advances in wilmstumor treatment and biology:

Progress Through In-ternational Collaboration. J Clin Oncol.

27:2999–3007. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Park JE, Noh OK, Lee Y, Choi HS, Han JW,

Hahn SM, Lyu CJ, Lee JW, Yoo KH, Koo HH, et al: Loss of

Heterozygosity at chromosome 16q is a negative prognostic factor in

Korean pediatric patients with favorable histology Wilms tumor: A

report of the Korean pediatric hematology oncology group (K-PHOG).

Cancer Res Treat. 52:438–445. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dix DB, Fernandez CV, Chi YY, Mullen EA,

Geller JI, Gratias EJ, Khanna G, Kalapurakal JA, Perlman EJ, Seibel

NL, et al: AREN0532 and AREN0533 study committees. Augmentation of

therapy for combined loss of heterozygosity 1p and 16q in favorable

histology wilms tumor: A Children's oncology group AREN0532 and

AREN0533 study report. J Clin Oncol. 30:2769–2777. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Li K, Zhang K, Yuan H and Fan C:

Prognostic role of primary tumor size in Wilms tumor. Oncol Lett.

27:1642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fernandez CV, Mullen EA, Chi YY, Ehrlich

PF, Perlman EJ, Kalapurakal JA, Khanna G, Paulino AC, Hamilton TE,

Gow KW, et al: Outcome and prognostic factors in stage III

Favorable-histology wilms tumor: A report from the Children's

oncology group study AREN0532. J Clin Oncol. 36:254–261. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dome JS, Mullen EA, Dix DB, Gratias EJ,

Ehrlich PF, Daw NC, Geller JI, Chintagumpala M, Khanna G,

Kalapurakal JA, et al: Impact of the first generation of Children's

oncology group clinical trials on clinical practice for wilms

tumor. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 19:978–985. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nelson MV, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Graf

N and Dome JS: New approaches to risk stratification for Wilms

tumor. Curr Opin Pediatr. 33:40–48. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Haruta M, Arai Y, Okita H, Tanaka Y,

Takimoto T, Sugino RP, Yamada Y, Kamijo T, Oue T, Fukuzawa M, et

al: Combined genetic and chromosomal characterization of wilms

tumors identifies chromosome 12 Gain as a potential new marker

predicting a favorable outcome. Neoplasia. 21:117–131. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yao W, Weng S, Li K, Shen J, Dong R and

Dong K: Bilateral Wilms tumor: 10-year experience from a single

center in China. Transl Cancer Res. 13:879–887. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tian XM, Ma W, Shi QL, Lu P, Liu X, Lin T,

He D and Wei G: Clinical analysis of 43 cases of Wilms tumor

treated with the CCCG-WT-2016 regimen. J Clin Pediatrics.

12:915–920. 2020.

|

|

19

|

Urology Group, Pediatric Surgery Society,

Chinese Medical Association, . Pediatric nephroblastoma diagnosis

and treatment expert consensus. Chin J Pediatr Surge. 7:585–590.

2020.

|

|

20

|

de Faria LL, Ponich Clementino C, Véras

FASE, Khalil DDC, Otto DY, Oranges Filho M, Suzuki L and Bedoya MA:

Staging and restaging pediatric abdominal and pelvic tumors: A

practical guide. Radiographics. 44:e2301752024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Geller JI, Hong AL, Vallance KL, Evageliou

N, Aldrink JH, Cost NG, Treece AL, Renfro LA and Mullen EA; COG

Renal Tumor Committee, : Children's oncology Group's 2023 blueprint

for research: Renal tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 70 (Suppl

6):e305862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dome JS, Graf N, Geller JI, Fernandez CV,

Mullen EA, Spreafico F, Van den Heuvel-Eibrink M and

Pritchard-Jones K: Advances in wilms tumor treatment and biology:

Progress through international collaboration. J Clin Oncol.

33:2999–3007. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wong KF, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Guha J,

Fidler MM, Kelly J, Lancashire ER, Pritchard-Jones K, Jenkinson HC,

Sugden E, et al: Risk of adverse healthand social outcomes up to 50

years after Wilms tumor: The British childhood cancer survivor

study. J Clin Oncol. 34:1772–1779. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Brok J, Mavinkurve-Groothuis AMC, Drost J,

Perotti D, Geller JI, Walz AL, Geoerger B, Pasqualini C, Verschuur

A, Polanco A, et al: Unmet needs for relapsed or refractory Wilms

tumour: Mapping the molecular features, exploring organoids and

designing early phase trials-A collaborative SIOP-RTSG, COG and

ITCC session at the first SIOPE meeting. Eur J Cancer. 144:113–122.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Luo X, Deng C, Liu F, Liu X, Lin T, He D

and Wei G: HnRNPL promotes Wilms tumor progression by regulating

the p53 and Bcl2 pathways. Onco Targets Ther. 12:4269–4279. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Phelps HM, Al-Jadiry MF, Corbitt NM,

Pierce JM, Li B, Wei Q, Flores RR, Correa H, Uccini S, Frangoul H,

et al: Molecular and epidemiologic characterization of Wilms tumor

from Baghdad, Iraq. World J Pediatr. 14:585–593. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang J, Lou S, Huang X, Mo Y, Wang Z, Zhu

J, Tian X, Shi J, Zhou H, He J and Ruan J: The association of

miR34b/c and TP53 gene polymorphisms with Wilms tumor risk in

Chinese children. Biosci Rep. 40:BSR201942022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Koshinaga T, Takimoto T, Oue T, Okita H,

Tanaka Y, Nozaki M, Tsuchiya K, Inoue E, Haruta M, Kaneko Y and

Fukuzawa M: Outcome of renal tumors registered in Japan Wilms Tumor

Study-2 (JWiTS-2): A report from the Japan Children's Cancer Group

(JCCG). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 65:e270562018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hol JA, Lopez-Yurda MI, Van Tinteren H,

Van Grotel M, Godzinski J, Vujanic G, Oldenburger F, De Camargo B,

Ramírez-Villar GL, Bergeron C, et al: Prognostic significance of

age in 5631 patients with Wilms tumour prospectively registered in

International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 93-01 and 2001.

PLoS One. 14:e02213732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chagtai T, Zill C, Dainese L, Wegert J,

Savola S, Popov S, Mifsud W, Vujanić G, Sebire N, Le Bouc Y, et al:

Gain of 1q as a prognostic biomarker in wilms tumors (WTs) treated

with preoperative chemotherapy in the international society of

paediatric oncology (SIOP) WT 2001 Trial: A SIOP renal tumours

biology consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 34:3195–3203. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ehrlich PF, Anderson JR, Ritchey ML, Dome

JS, Green DM, Grundy PE, Perlman EJ, Kalapurakal JA, Breslow NE and

Shamberger RC: Clinicopathologic findings predictive of relapse in

children with stage III favorable-histology Wilms tumor. J Clin

Oncol. 31:1196–1201. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Oue T, Koshinaga T, Takimoto T, Okita H,

Tanaka Y, Nozaki M, Haruta M, Kaneko Y and Fukuzawa M; Renal Tumor

Committee of the Japanese Children's Cancer Group, : Renal tumor

committee of the Japanese Children's cancer group. Anaplastic

histology Wilms' tumors registered to the Japan Wilms' Tumor study

group are less aggressive than that in the National Wilms' tumor

study 5. Pediatr Surg Int. 32:851–855. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Groenendijk A, Spreafico F, de Krijger RR,

Drost J, Brok J, Perotti D, van Tinteren H, Venkatramani R,

Godziński J, Rübe C, et al: Prognostic factors for wilms tumor

recurrence: A review of the literature. Cancers (Basel).

13:31422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Islam S, Moinuddin Mir AR, Raghav A, Habib

S, Alam K and Ali A: Glycation, oxidation and glycoxidation of IgG:

A biophysical, biochemical, immunological and hematological study.

J Biomol Struct Dyn. 36:2637–2653. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gadd S, Huff V, Walz AL, Ooms AHAG,

Armstrong AE, Gerhard DS, Smith MA, Guidry Auvil JM, Meerzaman D,

Chen QR, et al: A Children's oncology group and TARGET initiative

exploring the genetic landscape of Wilms tumor. Nat Genet.

49:1487–1494. 2017. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hol JA, Lopez-Yurda MI, Van Tinteren H,

Van Grotel M, Godzinski J, Vujanic G, Oldenburger F, De Camargo B,

Ramírez-Villar GL, Bergeron C, et al: Prognostic significance of

age in 5631 patients with Wilms tumour prospectively registered in

SIOP 93-01 and 2001. PLoS One. 14:e02213732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Dome JS, Perlman EJ and Graf N: Risk

stratification for wilms tumor: Current approach and future

directions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 215–223. 2014.doi:

10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.215. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Perotti D, Williams RD, Wegert J,

Brzezinski J, Maschietto M, Ciceri S, Gisselsson D, Gadd S, Walz

AL, Furtwaengler R, et al: Hallmark discoveries in the biology of

Wilms tumour. Nat Rev Urol. 21:158–180. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Madanat-Harjuoja LM, Renfro LA, Klega K,

Tornwall B, Thorner AR, Nag A, Dix D, Dome JS, Diller LR, Fernandez

CV, et al: Circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker in patients with

stage iii and iv Wilms tumor: Analysis from a Children's oncology

group trial, AREN0533. J Clin Oncol. 40:3047–3056. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gratias EJ, Dome JS, Jennings LJ, Chi YY,

Tian J, Anderson J, Grundy P, Mullen EA, Geller JI, Fernandez CV

and Perlman EJ: Association of chromosome 1q gain with inferior

survival in Favorable-histology wilms tumor: A report from the

Children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 34:3189–3194. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen Q, Chen J, Wang C, Chen X, Liu J,

Zhou L and Liu Y: MicroRNA-466o-3p mediates β-catenin-induced

podocyte injury by targeting Wilms tumor 1. FASEB J.

34:14424–14439. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Mohamed FS, Jalal D, Fadel YM, El-Mashtoly

SF, Khaled WZ, Sayed AA and Ghazy MA: Characterization and

comparative profiling of piRNAs in serum biopsies of pediatric

Wilms tumor patients. Cancer Cell Int. 25:1632025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ortiz MV, Ahmed S, Burns M, Henssen AG,

Hollmann TJ, MacArthur I, Gunasekera S, Gaewsky L, Bradwin G, Ryan

J, et al: Prohibitin is a prognostic marker and therapeutic target

to block chemotherapy resistance in Wilms' tumor. JCI Insight.

4:e1270982019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|