Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly

diagnosed cancer, with diagnoses made using clinical examination,

colonoscopy with biopsy, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

for local staging and computed tomography (CT) to detect distant

metastases (1,2). According to GLOBOCAN 2022, rectal

cancer accounted for 729,833 new cases globally, with an

age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) of 7.1/100,000, and caused

343,817 deaths, corresponding to an ASR of 3.1/100,000 (3,4). CRC)

represents 9–10% of all cancer diagnoses and ~9% of cancer-related

deaths worldwide (3). Established

risk factors for CRC include dietary and lifestyle exposures such

as high intake of processed and red meat, obesity and excess body

fat, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, low fiber intake, diets rich

in processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages, and physical

inactivity (5–7). Non-modifiable factors include advanced

age, family history of CRC, hereditary syndromes such as Lynch

syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) and familial

adenomatous polyposis (FAP), as well as inflammatory bowel

diseases, notably ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease (8). Prognosis depends on tumor stage, lymph

node involvement, metastatic spread, histological grade and

response to neoadjuvant therapy, with early-stage disease generally

associated with improved outcomes (9,10).

Treatment is stage-specific: Early tumors may be managed with

surgery alone, whereas locally advanced cases often require

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery (11,12).

Fluoropyrimidines, such as 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine, are

commonly used in chemoradiotherapy regimens; they exert their

antitumor effects primarily by inhibiting thymidylate synthase,

thereby disrupting DNA synthesis, and by incorporating into RNA and

DNA, leading to cytotoxicity in rapidly dividing tumor cells

(13–15).

Fluoropyrimidines are commonly used chemotherapeutic

agents for treating several types of solid tumor such as

gastrointestinal, head and neck, and breast cancers (16). These agents are primarily

metabolized by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) (17). Fluoropyrimidine-based regimens with

oxaliplatin or irinotecan are the standard treatment for colorectal

cancer. DPD is the key enzyme in fluoropyrimidine metabolism, with

DPYD gene variants causing DPD deficiency and increasing

toxicity risk (18). Complete DPD

deficiency is rare, occurring in 0.1–0.5% of the general population

(19,20). Partial DPD deficiency is more

common; heterozygous variant carrier rates have been reported in

3–8% of cases. Certain polymorphisms, particularly in the DPYD

gene, are associated with partial loss of enzyme activity (21,22).

Treatment-related mortality in patients with unrecognized DPD

deficiency who receive fluoropyrimidines has been reported to be

around 0.2–0.5% (19,23). The risk of fatal toxicity is

increased 5–10-fold, particularly in carriers of severe DPYD

variants (24). The presence of

DPYD variants was reported to be significantly associated

with increased treatment-related mortality [odds ratio, 34.86; 95%

confidence interval (CI), 13.96–87.05; P<0.05] (25).

The present study aimed to present a case of rectal

cancer treated with the CAPOX regimen (capecitabine and

oxaliplatin) and developing severe fluoropyrimidine toxicity due to

the DPYD mutation.

Case report

A mass was detected in the mid-rectum during a

colonoscopy performed on a 35-year-old male patient at Harran

University Medical Faculty Hospital (Sanliurfa, Turkey, in November

2023 due to rectal bleeding (Fig.

S1). The patient was admitted for advanced examination and

treatment with a preliminary diagnosis of rectal cancer. The biopsy

sample was fixed in 10% neutral formalin solution at room

temperature for 18–24 h, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a

thickness of 2.5 µm. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and

eosin using a Leica Autostainer XL. The preparations were examined

under a light microscope (Olympus BX43). Glandular structures

exhibiting cellular and structural atypia were observed, and the

findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma. Abdominal and pelvic

MRI and thoracic CT revealed locally advanced rectal cancer

(Fig. S2). Therefore, the patient

was started on neoadjuvant CAPOX chemotherapy (Oxaliplatin 130

mg/m2 IV on day 1 + capecitabine 1,000 mg/m2

orally twice daily on days 1–14, repeated every 21 days). By the

14th day of capecitabine treatment, the patient presented with a

fever (38.5°C), grade 3 oral mucositis, abdominal pain and grade 3

diarrhea. Laboratory findings revealed grade 3 neutropenia, grade 3

thrombocytopenia (according to Common Terminology Criteria for

Adverse Events v6.0) (26),

elevated international normalized ratio (INR) and grade 1

hyperbilirubinemia. Admission laboratory results are presented in

Table I. DPD enzyme deficiency was

suspected. Serological tests for hepatitis A, B, C, toxoplasmosis,

rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus and other agents, and

brucella were negative. Stool examination showed no parasitic

infections, and cultures were negative for rotavirus, adenovirus,

Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Shigella, Salmonella, E. coli, V.

cholerae, Y. enterocolitica, E. histolytica and C.

difficile toxins A/B. Blood, urine and stool cultures were

sterile.

| Table I.Laboratory test results. |

Table I.

Laboratory test results.

| Test | Result | Normal range |

|---|

| Leukocyte,

×103/µl | 2.6 | 4.0–10.0 |

| Neutrophil,

×103/µl | 1.0 | 1.6–6.9 |

| Lymphocyte,

×103/µl | 1.6 | 1.0–2.9 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 15.1 | 12.0–18.1 |

| Thrombocyte,

×103/ul | 67.0 | 142.0–424.0 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 113.0 | 74.0–106.0 |

| Urea, mg/dl | 38.5 | 19.0–50.0 |

| Creatinine,

mg/dl | 1.0 | 0.7–1.3 |

| ALT, U/l | 17.0 | 10.0–49.0 |

| AST, U/l | 21.0 | 0.0–34.0 |

| ALP, U/l | 43.0 | 46.0–116.0 |

| GGT, U/l | 16.0 | 0.0–73.0 |

| Total bilirubin,

mg/dl | 1.4 | 0.3–1.2 |

| Direct bilirubin,

mg/dl | 0.5 | 0.0–0.3 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 4.0 | 3.2–4.8 |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 133.0 | 132.0–146.0 |

| Potassium,

mmol/l | 3.7 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Calcium, mg/dl | 8.0 | 8.7–10.4 |

| Creatinine kinase,

U/l | 38.0 | 32.0–294.0 |

| Lactate

dehydrogenase, U/l | 209.0 | 120.0–246.0 |

| Serum reactive

protein, mg/dl | 0.3 | 0.0–0.5 |

| INR | 2.2 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Prothrombin time,

sec | 25.0 | 10.5–15.5 |

| Activated prothrombin

time, sec | 124.0 | 22.0–36.0 |

At admission, treatment included granulocyte

colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), piperacillin-tazobactam,

metronidazole, oral loperamide, glutamine and intravenous (IV) 0.9%

NaCl. On day 5 of hospitalization, severe diarrhea (>20

episodes/day) led to acute kidney injury (creatinine, 1.44 mg/dl),

electrolyte imbalances and hemodynamic instability, requiring ICU

transfer. Oral nystatin was started for suspected candidiasis.

Despite treatment, deep neutropenia and diarrhea persisted,

requiring continuous IV fluids, loperamide and octreotide infusion.

Furthermore, the cytopenia was closely followed. Grade 4

neutropenia (0.38×103/µl) presented on hospital day 2,

with a nadir of 0.002×103/µl by day 8. With daily

filgrastim, neutrophil counts normalized by day 17. Grade 4

thrombocytopenia (31×103/µl) developed by day 3,

reaching 5×103/µl on day 9 despite platelet

transfusions. Platelet counts recovered by day 24. Anemia

(hemoglobin, 10.5 g/dl) was detected on day 8 and a transfusion was

required. The recovery sequence was as follows: Neutropenia,

thrombocytopenia and finally, anemia. Moreover, by day 4, an

ongoing fever (38.4°C) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (36.8

mg/dl) prompted escalation to meropenem, linezolid and oral

vancomycin administration for suspected typhlitis, along with

fluconazole prophylaxis. Persistent fever and CRP elevation led to

caspofungin initiation on day 12. On day 14, herpetic lip lesions

were treated with ganciclovir. The patient received 18 units of

platelets, 8 units of fresh frozen plasma and 4 units of

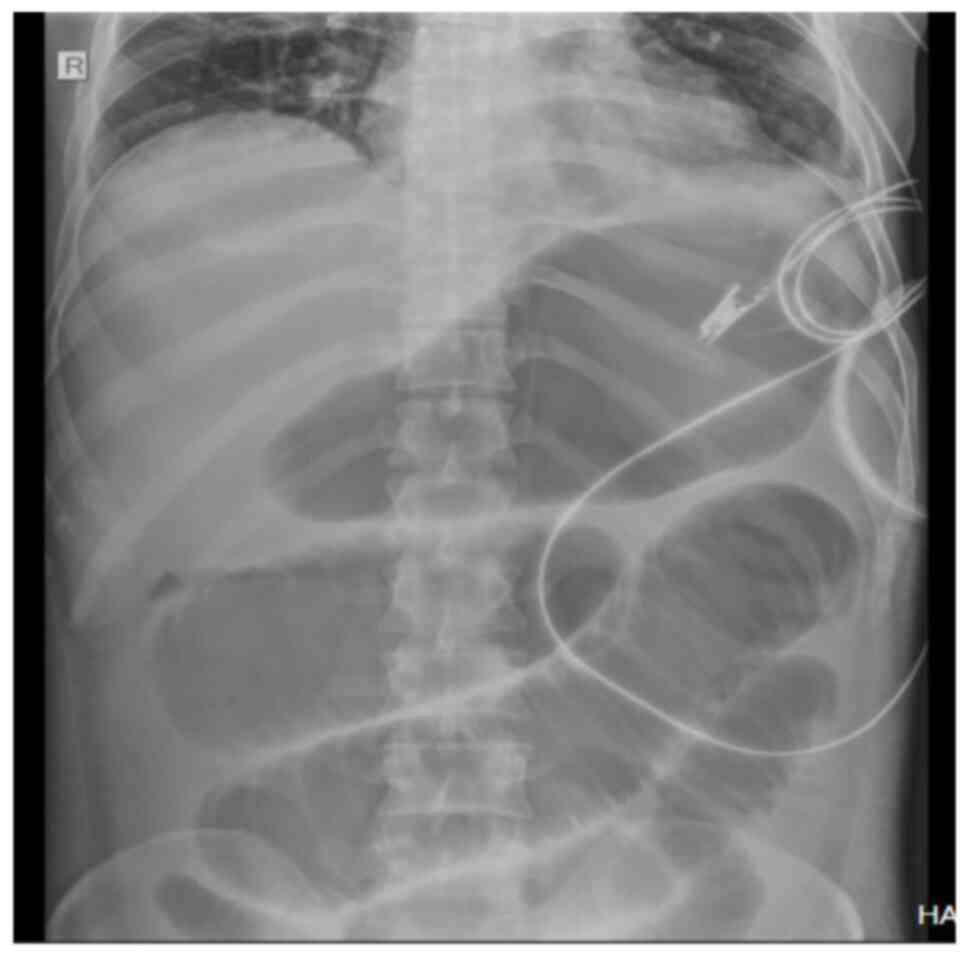

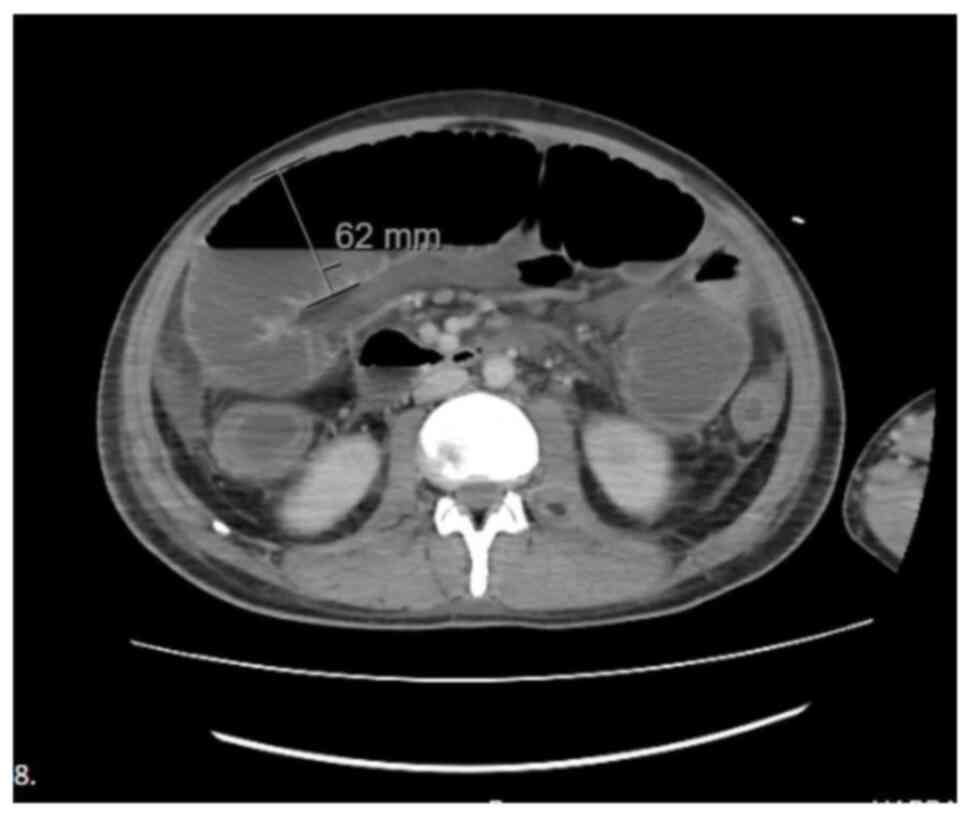

erythrocytes. Due to ongoing abdominal symptoms, imaging was

performed which revealed toxic megacolon (Figs. 1 and 2). Oral food intake was stopped, and

parenteral nutrition was initiated.

Genetic testing was performed using Sanger

sequencing to determine DPD deficiency, which was detected as

heterozygous c.2846A>T (p.Asp949Val) in Exon 22 (Fig. S3). The fever resolved by day 15,

diarrhea gradually subsided after day 20, and toxic megacolon

improved (Fig. S4). Neutropenia,

thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction, INR and bilirubin levels

normalized during follow-up. By day 28, all antibiotic, antifungal

and antiviral treatments were discontinued as infection markers

normalized. The patient achieved full clinical recovery and was

discharged. Laboratory follow-up results are presented in Table II.

| Table II.Laboratory results of the patient

during follow-up. |

Table II.

Laboratory results of the patient

during follow-up.

|

|

Day |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Test | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 30 |

|---|

| Leukocyte,

103/µl | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 9.9 | 11.5 | 12.9 | 12.2 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 4.9 |

| Neutrophil,

103/µl | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| Platelet,

103/µl | 67.0 | 58.0 | 31.0 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 38.0 | 25.0 | 15.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 20.0 | 22.0 | 19.0 | 50.0 | 31.0 | 25.0 | 49.0 | 59.0 | 50.0 | 98.0 | 144.0 | 192.0 | 285.0 | 381.0 |

| Hgb, g/dl | 15.0 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 15.5 | 15.0 | 13.2 | 12.1 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 10.2 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 10.5 |

| Creatinine,

mg/dl | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| ALT, U/l | 17.0 | 17.0 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 17.0 | 19.0 | 18.0 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 15.0 | 21.0 | 19.0 | 23.0 | 41.0 | 42.0 | 43.0 | 43.0 | 52.0 | 54.0 | 48.0 | 43.0 | 28.0 | 25.0 | 21.0 |

| Total bilirubin,

mg/dl | 1.4 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Direct bilirubin,

mg/dl | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 133.0 | 136.0 | 131.0 | 120.0 | 119.0 | 122.0 | 124.0 | 137.0 | 148.0 | 155.0 | 152.0 | 148.0 | 147.0 | 140.0 | 135.0 | 133.0 | 134.0 | 132.0 | 132.0 | 131.0 | 133.0 | 134.0 | 138.0 | 137.0 |

| Potassium,

mmol/l | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| LDH, U/l | 209.0 | 159.0 | 210.0 | 164.0 | 188.0 | 164.0 | 172.0 | 204.0 | 241.0 | 231.0 | 245.0 | 315.0 | 444.0 | 430.0 | 406.0 | 541.0 | 326.0 | 303.0 | 298.0 | 268.0 | 345.0 | 173.0 | 239.0 | 276.0 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 0.2 | 0.5 | 5.6 | 36.8 | 40.8 | 37.4 | 42.4 | 35.0 | 37.0 | 35.5 | 39.0 | 42.0 | 44.0 | 23.0 | 18.0 | 16.0 | 13.0 | 7.9 | 6.2 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.7 |

| INR | 2.1 | 1.0 | - | - | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | - | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.9 | - | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

|

|

| 1.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| PT, sec | 25.0 | 12.0 | - | - | 21.0 | 22.0 | 24.0 | - | 26.0 | 22.0 | 23.0 | - | 19.0 | 17.0 | 15.0 |

|

|

| 14.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

| APT, sec | 124.0 | 19.0 | - | - | 26.0 | 38.0 | 28.0 | - | 27.0 | 28.0 | 27.0 | - | 28.0 | 26.0 | 25.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In February 2024, a follow-up abdominal MRI revealed

a partial radiological response (Fig.

S5). Based on this finding, the multidisciplinary tumor board

recommended a low anterior resection, which was performed at the

Department of General Surgery, Koç University Hospital, Istanbul,

Turkey, Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen

confirmed a partial tumor response (data not shown). Adjuvant

chemotherapy was not administered due to the development of severe

DPD deficiency. The patient was followed up with abdominal MRI and

thoracic CT scans at 3-month intervals. The latest imaging

modalities revealed no evidence of disease recurrence as of June

2025 (Fig. S6).

Discussion

DPD deficiency is a life-threatening complication of

fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy (27). In a meta-analysis of eight cohort

studies (n=7,365), four DPYD variants [c.1905+1G>A,

c.2846A>T, c.1679T>G and c.1129–5923C>G (HapB3)] were

notably associated with severe fluoropyrimidine-associated

toxicity, with relative risks of 2.9 (95% CI, 1.8–4.6), 3.0 (95%

CI, 2.2–4.1), 4.4 (95% CI, 2.1–9.3) and 1.6 (95% CI, 1.3–2.0),

respectively (19). In a DPD

deficiency study, c.2846A>T (Asp949Val) was associated with

increased toxicity in 1.4% (30/2,116) of patients, who presented

with neutropenia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and infection

(28). Another study reported that

all 10 patients with the 2846A>T variant were heterozygous, and

6/10 experienced grade 3–4 toxicities within the first two cycles

(29). In the present case,

heterozygosity at c.2846A>T was identified, and the patient

developed grade 4 neutropenia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea during

the initial cycles of treatment, similar to previously reported

cases. These toxicities typically begin with nonspecific symptoms

such as neutropenic fever, mucositis and diarrhea (30), and in the patient in the present

case, these emerged by day 14 of therapy. Previous research

indicates that symptom onset generally occurs between days 10–24,

with gastrointestinal involvement being common (31). Clinically, oncologists should remain

vigilant for possible DPD deficiency in patients who present with

high-grade fluoropyrimidine-related toxicities, particularly in the

early phase of treatment.

As the patient in the present case received CAPOX,

we hypothesized that the clinical spectrum was attributable to

oxaliplatin toxicity; however, the patient did not exhibit any

neuropathy or cold paresthesias that could be associated with acute

oxaliplatin toxicity. There was no acute hemolytic anemia

associated with oxaliplatin due to predominance of direct

bilirubin. Similarly, no elevations in alanine aminotransferase or

aspartate aminotransferase were observed, suggesting acute liver

toxicity associated with oxaliplatin. Indeed, genetic testing

identified DPD deficiency, and the current clinical condition was

attributed to this deficiency.

The present patient demonstrated worsening of

symptoms despite aggressive treatment. The neutrophil count of the

patient in the present case declined from 950 to 50/µl by day 3,

reducing to 2/µl on day 8 despite G-CSF therapy. This profound

neutropenia necessitated early broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Therefore, piperacillin-tazobactam and metronidazole were

initiated, later escalating to meropenem, linezolid and antifungal

coverage. Despite extensive microbiological testing, no causative

pathogen was identified. A previous report indicated fatal

infection such as cytomegalovirus enterocolitis (32).

Severe diarrhea is another hallmark of severe

fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity. In the present case, the

patient's diarrhea symptoms progressed from grade 3 to 4, requiring

intensive care hospitalization. Despite loperamide and intravenous

hydration, symptoms persisted, requiring high-dose octreotide

infusion. This led to abdominal distension, ileus and toxic

megacolon, and the diarrhea continued. Octreotide was suspected to

contribute to these complications.

Furthermore, slight fluctuations in certain

laboratory parameters (leukocyte, neutrophil, platelet, total and

direct bilirubin) were observed; however, these were considered to

be minimal with no notable clinical impact as the variations were

within acceptable clinical and laboratory limits (Table II). The clinical condition of the

patient remained stable despite these changes. Additionally, a

search of the literature revealed no research specifically

addressing such fluctuations in laboratory values in patients with

DPD deficiency.

Currently, routine DPYD genetic testing is

not standard in several countries, including Turkey; however, the

European Medicines Agency recommends pre-treatment screening to

adjust dosing and prevent toxicity (24). In most regions, testing is performed

retrospectively, potentially underestimating mortality (33). According to Clinical

Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines,

fluoropyrimidine dosing should be based on DPD activity assessed by

uracil concentration and the dihydrouracil to uracil (UH2:Ura)

ratio. Standard dosing is appropriate for normal DPD activity

(uracil, <16 ng/ml;, UH2:Ura, >10). In partial DPD deficiency

(uracil, ≥16 ng/ml and/or UH2:Ura, <10), a 50% dose reduction is

recommended. In complete DPD deficiency, fluoropyrimidines should

be avoided due to high toxicity risk (20).

Despite having a heterozygous DPYD mutation, the

clinical course was severe, although severe diarrhea continued,

toxic megacolon developed, and the patient was discharged with full

recovery with long-term supportive treatment.

Moreover, there are certain limitations in the

present case. Firstly, DPD activity measurement was not performed

using the UH2:Ura ratio recommended for fluoropyrimidine dose

modification according to the CPIC guidelines, and therefore

adjuvant chemotherapy treatment was not administered. Secondly, a

single case cannot clearly establish causality, estimate risk

magnitude, or offer generalizable clinical recommendations based on

case series.

In conclusion, patients with suspected DPD

deficiency should be managed as immunosuppressed individuals, akin

to stem cell transplant recipients. Intensive monitoring,

broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, antifungals and aggressive

supportive care, including blood transfusions and ICU admission,

are crucial to improve outcomes in these high-risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ST was the major contributor to writing the

manuscript. ST and OK analysed the data and conceived and design of

the study. ST and OK confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of the present case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN), . Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Rectal Cancer.

Version 2.2024.

|

|

2

|

Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain

MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Dilawari RA, Engstrom

PF, et al: Rectal cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice

guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 20:1129–1161. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC), . Global cancer observatory: Cancer today. IARC;

Lyon: 2022

|

|

5

|

World cancer research fund/American

ınstitute for cancer research, . Diet, nutrition, physical activity

and colorectal cancer. Continuous Update Project Expert Report.

2018.

|

|

6

|

Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y,

Ghissassi FE, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Mattock H and Straif K;

International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working

Group, : Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat.

Lancet Oncol. 16:1599–1600. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Botteri E, Borroni E, Sloan EK, Bagnardi

V, Bosetti C, Peveri G, Santucci C, Specchia C, van den Brandt P,

Gallus S and Lugo A: Smoking and colorectal cancer risk: An overall

and dose-response meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 31:545–559. 2020.

|

|

8

|

Keum N and Giovannucci E: Global burden of

colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention

strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:713–732. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rödel C,

Wittekind C, Fietkau R, Martus P, Tschmelitsch J, Hager E, Hess CF,

et al: Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for

rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 351:1731–1740. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown

G, Rödel C, Cervantes A and Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee, :

Rectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis,

treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 28 (Suppl):iv22–iv40. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

van Gijn W, Marijnen CAM, Nagtegaal ID,

Kranenbarg EM, Putter H, Wiggers T, Rutten HJT, Påhlman L,

Glimelius B and van de Velde CJH; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group, :

Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision

for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre,

randomised Dutch TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 12:575–582. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L,

Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, Daban A, Bardet E, Beny A and Ollier

JC; EORTC Radiotherapy Group Trial 22921, : Chemotherapy with

preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med.

355:1114–1123. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Longley DB, Harkin DP and Johnston PG:

5-Fluorouracil: Mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat

Rev Cancer. 3:330–338. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Peters GJ, Backus HH, Freemantle S, van

Triest B, Codacci-Pisanelli G, van der Wilt CL, Smid K, Lunec J,

Calvert AH, Marsh S, et al: Induction of thymidylate synthase as a

5-fluorouracil resistance mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1587:194–205. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Houghton JA, Tillman DM and Harwood FG:

Ratio of 5-fluorouracil incorporation into RNA and DNA of human

colon carcinoma cells determines cytotoxicity. Cancer Res.

55:611–617. 1995.

|

|

16

|

Gross E, Busse B, Riemenschneider M,

Neubauer S, Seck K, Klein HG, Kiechle M, Lordick F and Meindl A:

Strong association of a common dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene

polymorphism with fluoropyrimidine-related toxicity in cancer

patients. PLoS One. 3:e40032008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Thorn CF, Marsh S, Carrillo MW, McLeod HL,

Klein TE and Altman RB: PharmGKB summary: Fluoropyrimidine

pathways. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 21:237–242. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Paulsen NH, Vojdeman F, Andersen SE,

Bergmann TK, Ewertz M, Plomgaard P, Hansen MR, Esbech PS, Pfeiffer

P, Qvortrup C and Damkier P: DPYD genotyping and dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase (DPD) phenotyping in clinical oncology. A clinically

focused minireview. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 131:325–346.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Meulendijks D, Henricks LM, Sonke GS,

Deenen MJ, Froehlich TK, Amstutz U, Largiadèr CR, Jennings BA,

Marinaki AM, Sanderson JD, et al: Clinical relevance of DPYD

variants c.1679T>G, c.1236G>A/HapB3, and c.1601G>A as

predictors of severe fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data.

Lancet Oncol. 16:1639–1650. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM,

Barbarino J, Schellens JHM, Swen JJ, Klein TE, McLeod HL, Caudle

KE, Diasio RB and Schwab M: Clinical pharmacogenetics

ımplementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase genotype and fluoropyrimidine dosing: 2017 update.

Clin Pharmacol Ther. 103:210–216. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Deenen MJ, Meulendijks D, Cats A,

Sechterberger MK, Severens JL, Boot H, Smits PH, Rosing H,

Mandigers CM, Soesan M, et al: Upfront genotyping of DPYD*2A to

individualize fluoropyrimidine therapy: A safety and cost analysis.

J Clin Oncol. 34:227–234. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lunenburg CATC, van der Wouden CH,

Nijenhuis M, Crommentuijn-van Rhenen MH, de Boer-Veger NJ, Buunk

AM, Houwink EJF, Mulder H, Rongen GA, van Schaik RHN, et al: Dutch

pharmacogenetics working group (DPWG) guideline for the gene-drug

interaction of DPYD and fluoropyrimidines. Eur J Hum Genet.

28:508–517. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM,

Meulendijks D, Frederix GWJ, Kienhuis E, Creemers GJ, Baars A,

Dezentjé VO, Imholz ALT, et al: DPYD genotype-guided dose

individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with

cancer: A prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol. 19:1459–1467.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

European Medicines Agency (EMA), .

Fluorouracil and fluorouracil-related substances (capecitabine,

tegafur and flucytosine): Direct healthcare professional

communication on pre-treatment testing to identify DPD-deficient

patients at increased risk of severe toxicity. EMA; Amsterdam:

2020

|

|

25

|

de Moraes FCA, de Almeida Barbosa AB, Sano

VKT, Kelly FA and Burbano RMR: Pharmacogenetics of DPYD and

treatment-related mortality on fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy for

cancer patients: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMC

Cancer. 24:12102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

National Cancer Institute (NCI), . Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version v6.0.U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services; 2025

|

|

27

|

Morel A, Boisdron-Celle M, Fey L,

Lainé-Cessac P and Gamelin E: Identification of a novel mutation in

the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene in a patient with a lethal

outcome following 5-fluorouracil administration and the

determination of its frequency in a population of 500 patients with

colorectal carcinoma. Clin Biochem. 40:11–17. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Morel A, Boisdron-Celle M, Fey L, Soulie

P, Craipeau MC, Traore S and Gamelin E: Clinical relevance of

different dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene single nucleotide

polymorphisms on 5-fluorouracil tolerance. Mol Cancer Ther.

5:2895–2904. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Madi A, Fisher D, Maughan ST, Colley JP,

Meade AM, Maynard J, Humphreys V, Wasan H, Adams RA, Idziaszczyk S,

et al: Pharmacogenetic analyses of 2183 patients with advanced

colorectal cancer; potential role for common dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase variants in toxicity to chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer.

102:31–39. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, Yoshino

T, Paul J, Taieb J, Souglakos J, Shi Q, Kerr R, Labianca R, et al:

Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N

Engl J Med. 378:1177–1188. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hagiwara Y, Yamamoto Y, Inagaki Y,

Tomisaki R, Tsuji M, Fukuda S, Fukuda S, Onoda T, Suzuki H, Niisato

Y, et al: Severe gastrointestinal disorder due to capecitabine

associated with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency: A case

report and literature review. Intern Med. 61:2449–2455. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Inoue F, Yano T, Nakahara M, Okuda H,

Amano H, Yonehara S and Noriyuki T: Cytomegalovirus enterocolitis

in a patient with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency after

capecitabine treatment: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep.

56:55–58. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ragia G, Maslarinou A, Atzemian N, Biziota

E, Koukaki T, Ioannou C, Balgkouranidou I, Kolios G, Kakolyris S,

Xenidis N, et al: Implementing pharmacogenetic testing in

fluoropyrimidine-treated cancer patients: DPYD genotyping to guide

chemotherapy dosing in Greece. Front Pharmacol. 14:12488982023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|