Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the seventh most common

malignancy worldwide and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related

mortality. The incidence and mortality rates of EC in Eastern Asia

are significantly higher than the global average (1,2). EC is

highly invasive and associated with a poor prognosis. The two major

histological subtypes of EC are squamous cell carcinoma and

adenocarcinoma, with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)

accounting for ~90% of cases in China. Due to the lack of obvious

early symptoms, most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage,

leading to a 5-year survival rate of <30% (3), and only 25–35% of patients are

eligible for curative surgery. For patients with locally advanced

disease, poor surgical tolerance or unresectable tumors, radical

radiotherapy remains the initial treatment option (4).

Patients with EC frequently experience malnutrition

due to dysphagia, and muscle loss worsens with aging (5,6).

Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to sarcopenia, and

studies have demonstrated that muscle nutritional status is closely

associated with the prognosis of various malignancies, including EC

(7–9). Therefore, selecting appropriate

clinical indicators to quantify muscle nutritional status is

crucial for the prognostic evaluation of EC. Imaging modalities

such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging are

considered the gold standard for non-invasive muscle mass

assessment (10,11). The skeletal muscle index (SMI) (a

planar index that describes the area of skeletal muscle)

(cm2/m2) is a widely accepted parameter for

quantifying muscle mass and is calculated as SMI=skeletal muscle

area (cm2)/height2 (m2). SMI at

the third lumbar vertebra (L3) level best reflects overall skeletal

muscle status (9). However, as EC

is a thoracic malignancy, imaging evaluations primarily involve

chest CT scans. Therefore, using radiotherapy planning CT scans to

assess thoracic skeletal muscle parameters, such as the skeletal

muscle volume index (SMVI) (a three-dimensional index that

describes the volume of skeletal muscle), may provide a convenient

and standardized method to quantify muscle nutritional status.

The present study utilized CT-based quantification

of skeletal muscle volume at the 10th thoracic vertebra (T10)

level, combined with hematological nutritional indices, to

investigate prognostic factors in elderly patients with ESCC.

Additionally, the study proposes a clinically feasible method for

quantifying muscle nutritional status to provide a reference for

nutritional intervention and prognostic assessment.

Patients and methods

Study participants

The present study was a retrospective analysis of

data from 123 elderly patients with ESCC treated with radiotherapy

in the Department of Radiotherapy of The Affiliated Hospital of

Xuzhou Medical University (Xuzhou, China) between October 2018 and

October 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Elderly

patients aged 60–89 years; ii) a diagnosis of ESCC confirmed

through histology or cytology records; iii) stage II–IVa disease

[American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition] (12); and iv) complete medical records

before and after treatment. Exclusion criteria: i) Patients

receiving resection; ii) patients with a second primary tumor; iii)

patients with serious underlying disease affecting the tumor

treatment; iv) patients with distant metastasis; and v) patients

missing clinical data or lost to follow-up before and after

treatment. Patients were followed up by telephone and by follow-up

visits until October 2024. The observed endpoints were overall

survival (OS) (defined as the time from the diagnosis to the death

due to any cause) and progression-free survival (PFS) (defined as

the time from diagnosis to tumor progression or death from any

cause). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (approval no.

XYFY2025-KL215-01).

Collection of clinical data

General clinical data were collected from patient

records, including sex, age, height, weight, tumor location, lesion

length, gross tumor volume (GTV), Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) stage

(AJCC 8th edition), initial treatment, application of immunotherapy

(immunotherapy before PFS or OS), radiotherapy dose and ECOG score.

Hematological data included routine blood test results and albumin

levels in a morning examination within 2 weeks of primary

radiotherapy. Imaging data included radiotherapy localization

CT.

Research nutrition-related

indicators

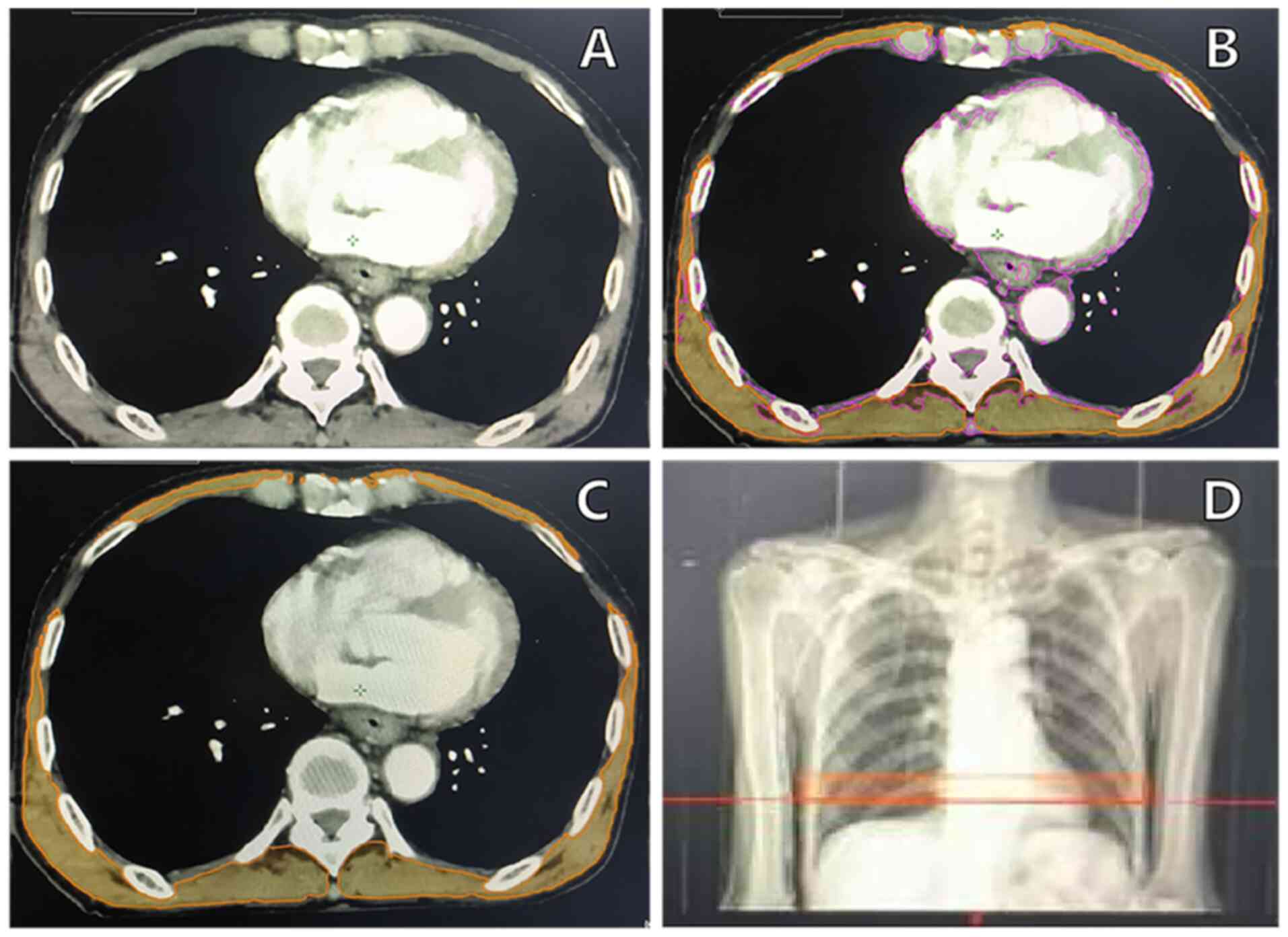

In the thoracic region, the T10 region is located at

the junction of the thoracic and abdominal regions, and contains

both thoracic and abdominal skeletal muscles, making it a

comprehensive indicator of skeletal muscle status (13). Tissue with a CT attenuation value

between −29 and 150 Hounsfield Units (HU) is classified as skeletal

muscle (10). In the CT soft-tissue

window of the Varian radiotherapy system (Siemens Healthineers),

T10 was identified between the upper and lower intervertebral

discs, with an automated delineation of tissue within the −29 to

150 HU range, followed by manual layer-by-layer modifications to

accurately outline all skeletal muscles in this segment. As shown

in Fig. 1, the skeletal muscle

volume (cm3) was measured and normalized by height

(m2) to assess skeletal muscle nutritional status,

calculated using the T10 SMVI as follows: T10 SMVI

(cm3/m2)=T10 skeletal muscle volume

(cm3)/height2 (m2). The Prognostic

Nutritional Index (PNI) and the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index

(GNRI) were used as representative hematological nutritional

markers (14). PNI has been

extensively studied as a prognostic factor for multiple solid

tumors, including those of the digestive system (14–17),

while GNRI reflects the nutritional status of elderly patients and

has been validated in multiple disease studies as an effective

predictor of prognosis (18,19).

PNI was calculated as PNI=serum albumin (g/l) + 5 × blood

lymphocyte count (/l), while GNRI was calculated as GNRI=1.489 ×

serum albumin (g/l) + 41.7 × (weight/ideal weight), with ideal

weight determined using the Lorentz formula [22 ×

height2 (m2)]. GNRI risk classification was

divided into four categories: Normal (GNRI >98), low risk

(92≤GNRI≤98), moderate risk (82≤GNRI<92) and high risk (GNRI

<82). In this study, a GNRI score of 98 was used as the cutoff

to classify patients into a GNRI normal group (GNRI >98; n=84)

and a GNRI risk group (GNRI ≤98; n=39) (17).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and data visualization were

conducted using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp.) and RStudio 4.2.0 (RStudio

Inc.). The optimal cutoff values for T10 SMVI, PNI and GTV were

determined using X-tile 3.6.1 (Yale University School of Medicine).

Quantitative variables following a normal distribution are

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s) and were

compared between groups using an independent sample t-test.

Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages,

and were analyzed using the χ2 test for between-group

comparisons. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for

survival analysis, and the log-rank test was used to assess

differences in survival outcomes between subgroups. The receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to calculate the area

under the curve to evaluate the predictive performance of PNI, GNRI

and T10 SMVI for survival outcomes in elderly patients with ESCC.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox

proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Comparison of general clinical

characteristics in elderly patients with ESCC undergoing

radiotherapy

A total of 85 male and 38 female patients were

included in this study. The optimal cutoff values for T10 SMVI were

determined as 52.1 cm3/m2 for males and 45.5

cm3/m2 for females, and patients were

stratified into two groups: The T10 sarcopenia group (below the

cutoff value) and the T10 non-sarcopenia group (above the cutoff

value). Patients in the T10 sarcopenia group were more likely to be

older (≥75 years), with a lower BMI, tumors located in the lower

thoracic region and advanced TNM stage, and were more likely to

have received radiotherapy alone (all P<0.05). Additionally, the

T10 sarcopenia group had a significantly lower hemoglobin level,

GNRI and serum albumin level compared with the T10 non-sarcopenia

group (all P<0.05), as shown in Tables I and II.

| Table I.Comparison of general clinical

characteristics in elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy [n (%)] classified by the T10

skeletal muscle volume index. |

Table I.

Comparison of general clinical

characteristics in elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy [n (%)] classified by the T10

skeletal muscle volume index.

| Clinical

features | T10

sarcopenia (n=59) | T10

non-sarcopenia (n=64) | Total (n=123) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

| 2.727 | 0.099 |

| Male | 45 (76.3) | 40 (62.5) | 85 (69.1) |

|

|

|

Female | 14 (23.7) | 24 (37.5) | 38 (30.9) |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

| 8.836 | 0.003 |

|

60-74 | 30 (50.8) | 49 (76.6) | 79 (64.2) |

|

|

|

75-89 | 29 (49.2) | 15 (23.4) | 44 (35.8) |

|

|

| BMI,

kg/m2 |

|

|

| 13.063 | 0.001 |

|

<18.5 | 11 (18.6) | 1 (1.6) | 12 (9.8) |

|

|

|

18.5-24 | 39 (66.1) | 42 (65.6) | 81 (65.9) |

|

|

|

≥24 | 9 (15.3) | 21 (32.8) | 30 (24.4) |

|

|

| Tumor location |

|

|

| 7.322 | 0.026 |

|

Upper | 13 (22.0) | 27 (42.2) | 40 (32.5) |

|

|

|

Middle | 26 (44.1) | 26 (40.6) | 52 (42.3) |

|

|

|

Lower | 20 (33.9) | 11 (17.2) | 31 (25.2) |

|

|

| TNM stage |

|

|

| 12.267 | 0.002 |

| II | 2 (3.4) | 14 (21.9) | 16 (13.0) |

|

|

|

III | 37 (62.7) | 40 (62.5) | 77 (62.6) |

|

|

|

IVa | 20 (33.9) | 10 (15.6) | 30 (24.4) |

|

|

| Lesion length,

cm |

|

|

| 0.016 | 0.898 |

| ≤7 | 39 (66.1) | 43 (67.2) | 45 (36.6) |

|

|

|

>7 | 20 (33.9) | 21 (32.8) | 41 (33.3) |

|

|

| GTV,

cm3 |

|

|

| 0.098 | 0.755 |

|

≤22.9 | 26 (44.1) | 30 (46.9) | 56 (45.5) |

|

|

|

>22.9 | 33 (55.9) | 34 (53.1) | 67 (54.5) |

|

|

| Initial

treatment |

|

|

| 8.016 | 0.018 |

| RT | 26 (44.1) | 13 (20.3) | 39 (31.7) |

|

|

|

CCRT | 25 (42.4) | 38 (59.4) | 63 (51.2) |

|

|

|

RT-AIC | 8 (13.6) | 13 (20.3) | 21 (17.1) |

|

|

| Table II.Comparison of hematological

indicators in elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy (mean ± standard deviation). |

Table II.

Comparison of hematological

indicators in elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy (mean ± standard deviation).

| Hematological

indicator | T10

sarcopenia (n=59) | T10

non-sarcopenia (n=64) | T | P-value |

|---|

| HB, g/l | 126.47±14.28 | 131.50±11.61 | 2.149 | 0.034 |

| Albumin, g/l | 39.63±3.64 | 40.99±3.46 | 2.128 | 0.035 |

| PNI | 47.77±4.52 | 48.91±4.92 | 1.334 | 0.185 |

| GNRI | 98.99±7.70 | 105.44±8.11 | 4.514 | <0.001 |

Association between T10 SMVI and

survival prognosis in elderly patients with ESCC

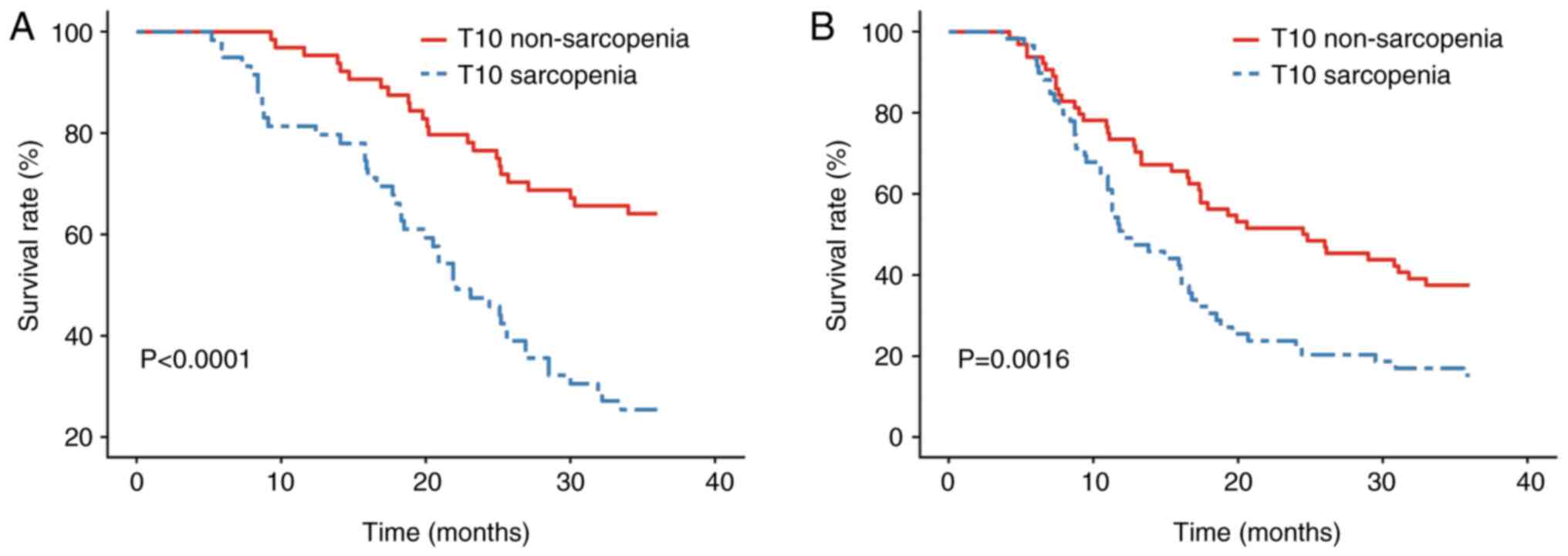

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis (Fig. 2A and B) and the log-rank test

demonstrated that OS and PFS times were significantly lower in the

T10 sarcopenia group than in the T10 non-sarcopenia group

(P<0.05), indicating a worse prognosis in patients with reduced

skeletal muscle volume. All patients were followed up for 36

months, during which 44 patients in the T10 sarcopenia group and 23

patients in the T10 non-sarcopenia group succumbed to the disease.

The 1-, 2- and 3-year OS rates were 81.4 vs. 95.3%, 47.5 vs. 76.6%

and 25.4 vs. 64.1%, respectively, for the T10 sarcopenia group and

T10 non-sarcopenia group. The median OS time in the T10 sarcopenia

group was 22.1 months, whereas the median OS time in the T10

non-sarcopenia group was not reached. A significant difference in

OS survival curves was observed between the two groups

(P<0.001), as shown in Fig. 2,

classified by T10 SMVI. The PFS rates in the T10 sarcopenia group

compared with those in the T10 non-sarcopenia group were 50.8 vs.

73.4%, 23.7 vs. 51.6% and 15.3 vs. 37.5% at 1, 2, and 3 years,

respectively, with a median PFS time of 12.0 vs. 24.7 months. The

PFS rate in the T10 sarcopenia group was significantly lower than

that in the T10 non-sarcopenia group (P=0.0016), as shown in

Fig. 2B.

T10 SMVI and the predictive value of

hematological nutritional indicators (PNI and GNRI) for survival

prognosis in elderly patients with ESCC

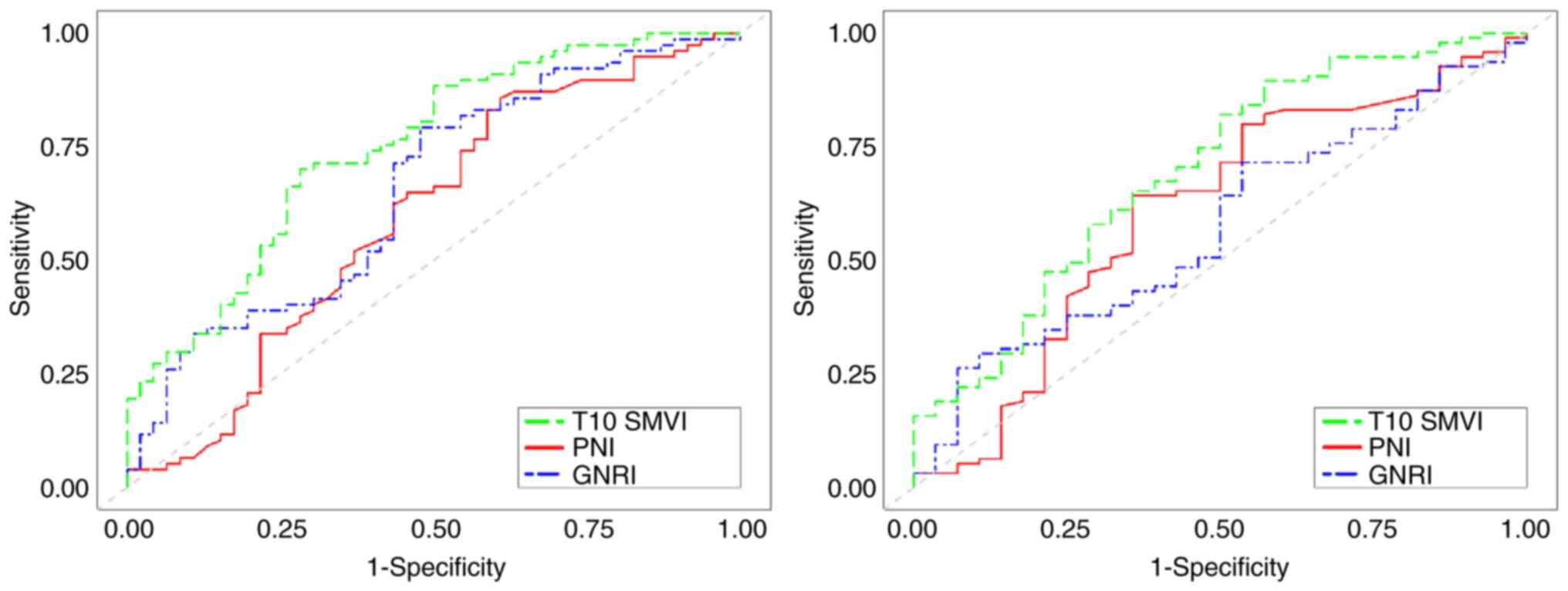

ROC curves were generated for T10 SMVI, PNI and

GNRI, as shown in Fig. 3. The

results demonstrated that T10 SMVI, PNI and GNRI were all

significant predictors of long-term survival in elderly patients

with ESCC (P<0.05), with T10 SMVI exhibiting superior predictive

value compared with PNI and GNRI, as shown in Table III.

| Table III.Receiver operating characteristic

curve analysis of three nutritional indicators for predicting

long-term survival (OS and PFS). |

Table III.

Receiver operating characteristic

curve analysis of three nutritional indicators for predicting

long-term survival (OS and PFS).

|

| OS | PFS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Indicator | AUC | 95% CI | P-value | AUC | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| T10 SMVI | 0.746 | 0.659-0.833 | <0.001 | 0.690 | 0.582-0.798 | 0.001 |

| PNI | 0.629 | 0.528-0.730 | 0.014 | 0.618 | 0.501-0.736 | 0.045 |

| GNRI | 0.690 | 0.596-0.784 | <0.001 | 0.624 | 0.516-0.733 | 0.035 |

Cox single-and multivariate regression

analysis

Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression

analysis of the 123 elderly patients with ESCC demonstrated that

BMI, TNM stage, GTV, initial treatment, T10 SMVI, PNI, GNRI and

immunotherapy were significantly associated with PFS and OS

(P<0.05). Further multivariate analysis identified TNM stage,

GTV, initial treatment, T10 SMVI and PNI as independent risk

factors for OS (P<0.05), while TNM stage, GTV, and initial

treatment were independent risk factors for PFS (P<0.05), as

shown in Tables IV and V. Additionally, late-stage radiotherapy

alone, advanced TNM stage, high GTV, low T10 SMVI and low PNI were

identified as independent risk factors for a shorter survival

time.

| Table IV.Univariate and multivariate analyses

of overall survival. |

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of overall survival.

|

| Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 0.847 | 0.512-1.404 | 0.520 |

|

|

|

| Age (≥75 vs. <75

years) | 1.604 | 0.991-2.596 | 0.054 |

|

|

|

| BMI (≥18.5 vs.

<18.5 kg/m2) | 0.307 | 0.156-0.604 | 0.001 | 0.866 | 0.378-1.980 | 0.732 |

| Tumor location

(upper vs. middle-lower neck) | 0.932 | 0.552-1.574 | 0.973 |

|

|

|

| TNM stage (IVa vs.

II/III) | 3.729 | 2.246-6.190 | <0.001 | 2.996 | 1.692-5.306 | <0.001 |

| Lesion length

(>7 vs. ≤7 cm) | 0.838 | 0.500-1.404 | 0.501 |

|

|

|

| GTV (>22.9 vs.

≤22.9 cm3) | 1.833 | 1.116-3.011 | 0.017 | 1.943 | 1.114-3.388 | 0.019 |

| Initial treatment

(non-RT only vs. RT only) | 0.388 | 0.239-0.629 | <0.001 | 0.527 | 0.304-0.916 | 0.023 |

| Immunotherapy (yes

vs. no) | 0.364 | 0.190-0.696 | 0.002 | 0.595 | 0.294-1.203 | 0.148 |

| Radiation dose (≥60

vs. <60 Gy) | 1.416 | 0.875-2.293 | 0.157 |

|

|

|

| T10 non-sarcopenia

group vs. T10 sarcopenia group | 0.332 | 0.200-0.552 | <0.001 | 0.467 | 0.263-0.831 | 0.010 |

| PNI (>52.0 vs.

≤52.0) | 0.357 | 0.170-0.748 | 0.006 | 0.389 | 0.178-0.848 | 0.018 |

| GNRI (>98 vs.

≤98) | 0.443 | 0.272-0.720 | 0.001 | 0.830 | 0.458-1.504 | 0.538 |

| Table V.Univariate and multivariate analyses

of progression-free survival. |

Table V.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of progression-free survival.

|

| Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 0.890 | 0.572-1.386 | 0.607 |

|

|

|

| Age (≥75 vs. <75

years) | 1.492 | 0.981-2.270 | 0.062 |

|

|

|

| BMI (≥18.5 vs.

<18.5 kg/m2) | 0.478 | 0.253-0.903 | 0.023 | 0.956 | 0.439-2.081 | 0.909 |

| Tumor location

(upper vs. middle-lower neck) | 0.999 | 0.639-1.564 | 0.998 |

|

|

|

| TNM stage (IVa vs.

II/III) | 2.684 | 1.685-4.275 | <0.001 | 2.037 | 1.240-3.346 | 0.005 |

| Lesion length

(>7 vs. ≤7 cm) | 0.739 | 0.471-1.161 | 0.190 |

|

|

|

| GTV (>22.9 vs.

≤22.9 cm3) | 1.624 | 1.065-2.475 | 0.024 | 1.786 | 1.144-2.790 | 0.011 |

| Initial treatment

(non-RT only vs. RT only) | 0.437 | 0.283-0.673 | <0.001 | 0.602 | 0.371-0.979 | 0.041 |

| Immunotherapy (yes

vs. no) | 0.410 | 0.218-0.773 | 0.006 | 0.592 | 0.300-1.168 | 0.130 |

| Radiation dose (≥60

vs. <60 Gy) | 1.156 | 0.765-1.749 | 0.491 |

|

|

|

| T10 non-sarcopenia

group vs. T10 sarcopenia group | 0.514 | 0.338-0.783 | 0.002 | 0.692 | 0.433-1.106 | 0.124 |

| PNI (>52.0 vs.

≤52.0) | 0.482 | 0.277-0.842 | 0.010 | 0.559 | 0.312-1.004 | 0.051 |

| GNRI (>98 vs.

≤98) | 0.559 | 0.362-0.862 | 0.008 | 0.854 | 0.511-1.427 | 0.547 |

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that T10

SMVI, as an indicator to quantify the nutritional status of T10

segments, can effectively predict the prognosis of elderly patients

with ESCC and has higher predictive efficacy than the hematological

nutritional indicators PNI and GNRI. Specifically, the T10 SMVI

threshold value used was 52.1 cm3/m2 in men

and 45.5 cm3/m2 in women. Although there are

ethnic, regional and measurement site differences in SMI, there are

no uniform criteria or reference values across studies. The samples

in the present study are from East China and align with the L3 SMI

diagnostic reference values [40.8 cm2/m2 for

men and 34.9 cm2/m2 for women, proposed by

Zhuang et al (20) in

Shanghai]. Previous SMI studies have mostly focused on

cross-sectional area, but the present study has explored muscle

volume in depth (9–11). Compared with plane studies, volume

studies are more comprehensive and holistic.

Radiotherapy localized planning CT, as a routine

examination method for radiotherapy patients, has the advantages of

being simple, non-invasive and economical to operate, so it has

high clinical application value. Although the cross-sectional area

of muscles at the lumbar 3 level has a high correlation with the

whole body muscle level and has become the common standard for SMI

assessment (9), since CT scans in

patients with EC do not always contain the third lumbar spine,

additional abdominal CT scans not only increase radiation exposure

but also increase the economic burden on patients. Unlike prior

studies using L3-level muscle index (requiring additional abdominal

CT) (9,20), the present study innovatively

leveraged routine radiotherapy planning CT to quantify thoracic

muscle volume (T10 SMVI), eliminating extra scans and reducing

radiation and economic burdens, thus enhancing clinical utility.

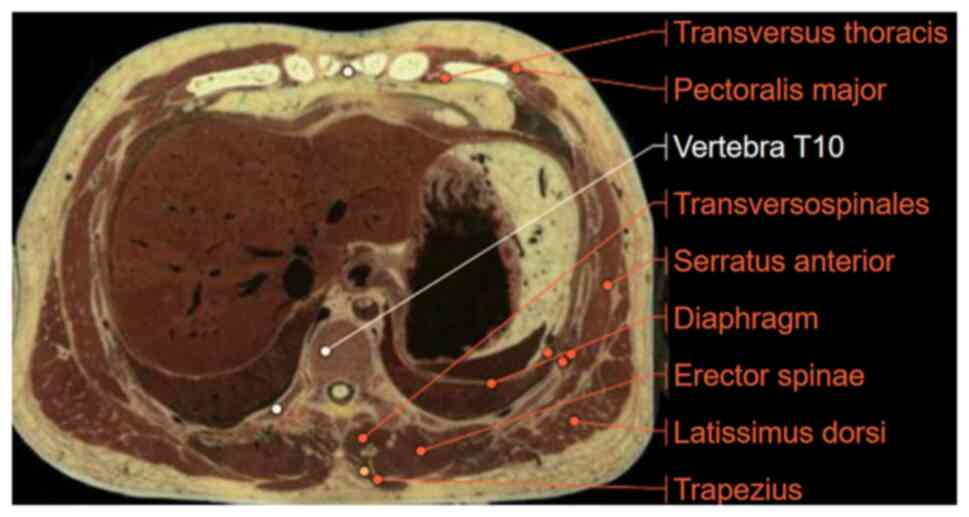

Therefore, the T10 segment was chosen as the anatomical region for

skeletal muscle quality assessment. This segment is located at the

thoracoabdominal junction and contains several key skeletal muscle

groups such as the erector spinal, latissimus dorsi, trapezius,

external abdominis, rectus abdominis and transverse

thoracoabdominal muscles (Fig. 4).

Among these, the erector spinal muscle is essential for spinal

support and serves as an early indicator reflecting whole-body

muscle wasting. Therefore, the T10 segment can comprehensively and

accurately reflect muscle mass, becoming the ideal region (13,21)

for assessing muscle nutritional status in the present study.

EC, as a chronic wasting disease, often leads to

sarcopenia in elderly patients, and is more common in male patients

>60 years old (22). The causes

of skeletal muscular dystrophy in patients with EC include: i)

Insufficient nutritional intake due to dysphagia (23). ii) Chronic inflammation promotes

protein and energy expenditure through multiple signaling pathways,

keeping the body in a negative nitrogen balance (24). iii) Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

increases the risk of sarcopenia in patients with EC, which may

cause apoptosis during chemoradiotherapy to cause inflammatory

response, and activate inflammatory factors to promote muscle

breakdown or stress response (25).

iv) Patients with EC, after long-term release and chemotherapy,

often need long-term bed rest due to physical decline, being easily

fatigued, poor spirit and a lack of moderate muscle exercise

(26). Therefore, assessing the

muscle nutritional status of patients and providing corresponding

nutritional intervention and treatment programs are crucial for

patient prognosis.

In the present study, the T10 sarcopenia group had a

significantly poorer long-term prognosis compared with the T10

non-sarcopenia group. Multivariate analysis showed that T10 SMVI

was an independent risk factor for OS in elderly patients with ESCC

who underwent radiotherapy. Despite baseline differences,

multivariate analysis confirmed the independent prognostic value of

T10 SMVI after adjusting for confounders. Further analysis found

that T10 sarcopenia group patients were mostly of an advanced

prognosis, with low BMI, late TNM stage and undergoing combined

radiotherapy rather than antitumor therapy. These characteristics

further support the association between skeletal sarcopenia and a

poor prognosis, which is consistent with the association between

sarcopenia and tumor prognosis in previous studies (9,20).

Patients with sarcopenia often show malnutrition, decreased muscle

strength and reduced quality of life, the factors that may

influence prognosis by influencing patient tolerance to treatment

and tumor biological behavior. The results of the present study

suggest that muscle nutritional status not only directly affects

the prognosis, but also may indirectly influence the survival

benefit of patients by influencing treatment choice and tolerance.

Combined treatment of EC can significantly improve OS compared with

radiotherapy alone (27). In recent

years, the application of immunotherapy in EC has gradually

increased, and it has been shown to bring marked survival benefits.

The results of the present study also show that either receiving

immunotherapy in the initial treatment stage or adding

immunotherapy after progression and relapse can improve the

long-term prognosis. Although immunotherapy was statistically

significant in the univariate analyses of PFS and OS, it did not

become an independent influence in the multivariate analysis, which

may be related to differences in the sample size and treatment

regimen of the patients.

The SMI is related to the toxicity of cancer

chemotherapy, and patients with EC and a low SMI are more likely to

have acute adverse reactions above grade 3 after chemotherapy

(28). Therefore, patients in the

T10 sarcopenia group are mostly treated with radiotherapy alone,

compared with the non-sarcopenia group with chemoradiotherapy. For

patients with EC, the SMI is measured before and during treatment,

and the muscle nutritional status is assessed, which can help guide

the treatment plan and dosage, and avoid acute adverse reactions.

Good nutritional status and muscle reserve help patients better

tolerate concurrent chemotherapy and immunotherapy, thus prolonging

survival. Clinically, for patients with skeletal muscle dystrophy,

personalized nutritional support and skeletal muscle exercise can

be provided to enhance treatment tolerance and improve survival

benefits (29,30).

In conclusion, the present study quantified the

muscle nutrition status of the T10 segment and introduced the T10

SMVI to predict the prognosis of elderly patients with ESCC. The

predictive efficacy of the T10 SMVI was higher than that of the

hematological nutrition indexes PNI and GNRI. In addition, T10 SMVI

has the advantages of being economically viable, rapid to check and

standardized, and can provide a new perspective for the prognostic

evaluation of elderly patients with ESCC undergoing radiotherapy,

with potential clinical application value. Specific values are

obtained from this study, which can provide a reference for the

clinical prognosis, diagnosis and treatment plan, and nutritional

intervention. However, the present study is a single-center study

with a limited sample size, and the reference values need to be

optimized through a multi-center, large-sample survey. Future

multi-center studies should validate T10 SMVI cutoff

generalizability and explore integrated models with hematological

indices, such as PNI. Investigations on nutrition and exercise

interventions to reverse sarcopenia and improve survival outcomes

are warranted.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

GL was the guarantor of integrity of the entire

study. SL and GL were responsible for the study concept and confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. SL and DP performed

literature research. SL, QL and DL designed the study and analyzed

the data. Data acquisition was performed by SL, QL and DL.

Statistical analysis and manuscript preparation were performed by

SL, DL, CJ and DP. The manuscript was edited by SL, QL, DL and CJ,

and reviewed by SL, QL and DL. All authors have read and approved

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Clinical Research

Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical

University (Xuzhou, China; approval no. XYFY2025-KL215-01). All

patients provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chen R, Zheng R, Zhang S, Wang S, Sun K,

Zeng H, Li L, Wei W and He J: Patterns and trends in esophageal

cancer incidence and mortality in China: An analysis based on

cancer registry data. J Natl Cancer Cent. 3:21–27. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

He J, Chen WQ, Li ZS, Li N, Ren JS, Tian

JH, Tian WJ, Hu FL, Peng J; Expert Group of China Guideline for the

Screening, ; et al: China guideline for the screening, early

detection and early treatment of esophageal cancer (2022, Beijing).

Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 44:491–522. 2022.(InChinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Guo Y, Wang T, Liu Y, Gu D, Li H, Liu Y,

Zhang Z, Shi H, Wang Q, Zhang R, et al: Comparison of

immunochemotherapy followed by surgery or chemoradiotherapy in

locally advanced esophageal squamous cell cancer. Int

Immunopharmacol. 141:1129392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, Assantachai P,

Auyeung TW, Bahyah KS, Chou MY, Chen LY, Hsu PS, Krairit O, et al:

Sarcopenia in Asia: Consensus report of the Asian working group for

Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 15:95–101. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Baracos V, Caserotti P, Earthman CP,

Fields D, Gallagher D, Hall KD, Heymsfield SB, Müller MJ, Rosen AN,

Pichard C, et al: Advances in the science and application of body

composition measurement. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 36:96–107.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xiao L, Liu Y, Zhang X, Nie X, Bai H, Lyu

J and Li T: Prognostic value of sarcopenia and inflammatory indices

synergy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

undergoing chemoradiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 24:8602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yamamoto M, Ozawa S, Koyanagi K, Kazuno A,

Ninomiya Y, Yatabe K, Higuchi T, Kanamori K and Tajima K:

Usefulness of skeletal muscle measurement by computed tomography in

patients with esophageal cancer: Changes in skeletal muscle mass

due to neoadjuvant therapy and the effect on the prognosis. Surg

Today. 53:692–701. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zheng K, Liu X, Li Y, Cui J and Li W:

CT-based muscle and adipose measurements predict prognosis in

patients with digestive system malignancy. Sci Rep. 14:130362024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhou H, Yu D, Yan X, Dong W, Chen W and Yu

Z: The effect of low muscle mass as measured on CT scans on

clinical outcome in elderly gastric cancer patients with

nutritional risks. Parenteral & Enteral Nutrition. 28:129–134.

2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

11

|

Kazemi-Bajestani SM, Mazurak VC and

Baracos V: Computed tomography-defined muscle and fat wasting are

associated with cancer clinical outcomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol.

54:2–10. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen M, Li X, Chen Y, Liu P, Chen Z, Shen

M, Liu X, Lin Y, Yang R, Ni W, et al: Proposed revision of the 8th

edition AJCC clinical staging system for esophageal squamous cell

cancer treated with definitive chemo-IMRT based on CT imaging.

Radiat Oncol. 14:542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jiang Z, Lu Y, Huang J, Shao J, Gao Z, Zhi

H, Shen Q and Shen X: The application of thoracic vertebral cross

section skeletal muscle index in the diagnosis and prognosis of

sarcopenia in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Journal of

Wenzhou Medical University. 53:868–874. 2023.(In Chinese).

|

|

14

|

Tsukagoshi M, Araki K, Igarashi T, Ishii

N, Kawai S, Hagiwara K, Hoshino K, Seki T, Okuyama T, Fukushima R,

et al: Lower geriatric nutritional risk index and prognostic

nutritional index predict postoperative prognosis in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma. Nutrients. 16:9402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang X and Wang Y: The prognostic

nutritional index is prognostic factor of gynecological cancer: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 67:79–86. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang L, Ma W, Qiu Z, Kuang T, Wang K, Hu

B and Wang W: Prognostic nutritional index as a prognostic

biomarker for gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 14:12199292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shi J, Liu T, Ge Y, Liu C, Zhang Q, Xie H,

Ruan G, Lin S, Zheng X, Chen Y, et al: Cholesterol-modified

prognostic nutritional index (CPNI) as an effective tool for

assessing the nutrition status and predicting survival in patients

with breast cancer. BMC Med. 21:5122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bouillanne O, Morineau G, Dupont C,

Coulombel I, Vincent JP, Nicolis I, Benazeth S, Cynober L and

Aussel C: Geriatric nutritional risk index: A new index for

evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am J Clin Nutr.

82:777–783. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Qiu X, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Yang M and

Tao L: Geriatric nutritional risk index and mortality from

all-cause, cancer, and non-cancer in US cancer survivors: NHANES

2001–2018. Front Oncol. 14:13999572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhuang CL, Huang DD, Pang WY, Zhou CJ,

Wang SL, Lou N, Ma LL, Yu Z and Shen X: Sarcopenia is an

independent predictor of severe postoperative complications and

long-term survival after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer:

Analysis from a large-scale cohort. Medicine (Baltimore).

95:e31642016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Derstine BA, Holcombe SA, Ross BE, Wang

NC, Su GL and Wang SC: Skeletal muscle cutoff values for sarcopenia

diagnosis using T10 to L5 measurements in a healthy US population.

Sci Rep. 8:113692018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hai S, Cao L, Wang H, Zhou J, Liu P, Yang

Y, Hao Q and Dong B: Association between sarcopenia and nutritional

status and physical activity among community-dwelling Chinese

adults aged 60 years and older. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 17:1959–1966.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Meza-Valderrama D, Marco E, Dávalos-Yerovi

V, Muns MD, Tejero-Sánchez M, Duarte E and Sánchez-Rodríguez D:

Sarcopenia, malnutrition, and cachexia: Adapting definitions and

terminology of nutritional disorders in older people with cancer.

Nutrients. 13:7612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Pan L, Xie W, Fu X, Lu W, Jin H, Lai J,

Zhang A, Yu Y, Li Y and Xiao W: Inflammation and sarcopenia: A

focus on circulating inflammatory cytokines. Exp Gerontol.

154:1115442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li S, Xie K, Xiao X, Xu P, Tang M and Li

D: Correlation between sarcopenia and esophageal cancer: A

narrative review. World J Surg Oncol. 22:272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chang YL, Tsai YF, Hsu CL, Chao YK, Hsu CC

and Lin KC: The effectiveness of a nurse-led exercise and health

education informatics program on exercise capacity and quality of

life among cancer survivors after esophagectomy: A randomized

controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 101:1034182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, Macdonald

JS, Martenson JA Jr, Al-Sarraf M, Byhardt R, Russell AH, Beitler

JJ, Spencer S, et al: Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced

esophageal cancer: Long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized

trial (RTOG 85-01). Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. JAMA.

281:1623–1627. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen X, Wang F and Liu C: Sarcopenia

Before Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy May DevelopSevere Adverse

Reactions in Patients with Esophageal Squamous CelCarcinoma. Cancer

Research on Prevention and Treatment. 50:1203–1208. 2023.(In

Chinese).

|

|

29

|

Jordan T, Mastnak DM, Palamar N and Kozjek

NR: Nutritional therapy for patients with esophageal cancer. Nutr

Cancer. 70:23–29. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zitvogel L, Pietrocola F and Kroemer G:

Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat Immunol. 18:843–850. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|