Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most diagnosed

cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death

worldwide for both sexes combined (1). In the U.S, it is the second most

common cancer in men under 50 years of age, with an estimated total

in 2023 of 153,020 diagnosed cases and 52,550 deaths, including

19,550 cases and 3,750 deaths in individuals younger than 50 years

(2). In the E.U., CRC accounts for

520,000 new cases (12.9% of all cancer diagnoses) and 250,000

deaths (12.6% of cancer-related mortality) (3). The management of metastatic CRC (mCRC)

has advanced, particularly with monoclonal antibodies targeting the

epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR mAb) combined with

5FU-based chemotherapy. Anti-EGFR mAb therapy requires the absence

of somatic mutations in exons 2, 3, and 4 of KRAS and NRAS genes

(4). BRAF gene mutations are

routinely assessed for their prognostic significance and their

association with new therapeutic strategies combining anti-EGFR

mAbs and BRAF kinase inhibitors (5).

Tissue-based biopsy remains the gold standard method

for molecular analysis of cancer, but its invasiveness and

potential complications limit its frequent use (6).

In France, somatic mutations in KRAS, NRAS,

and BRAF are primarily analysed on INCa (Institut National

du Cancer-French Cancer Institute) certified molecular genetics

platforms (INCa platform) using formalin-fixed paraffin embedded

(FFPE) tissue from biopsies of primary or secondary lesions or

surgically excised primary tumours (7). Given the limitations of tissue-based

biopsies and the dynamic genetic evolution of tumours, there is a

growing demand for a less invasive and more precise alternative

like liquid biopsy. In real-world settings, challenges such as

insufficient sample quantity or quality for genotyping, or the

inability to retrieve specimens from external centres, further

underscore this need. Monocentric prospective biomarker studies

have demonstrated the clinical utility of circulating tumour DNA

(ctDNA) as a valuable marker in first-line mCRC treatment (8) and in primary CRC at surgery and during

post-surgery follow-up (9).

However, without standardized workflows, liquid biopsy must be

validated against standard-of-care tissue testing in real-world

settings for routine tumour molecular profiling and identification

of treatment response biomarkers, such as KRAS, NRAS, and

BRAF mutations in CRC.

Several ctDNA analysis techniques exist, with

studies confirming the feasibility of liquid biopsy for KRAS and

BRAF genotyping (10,11). Yet, few prospective real-world

studies have been conducted. The BEAMing (Beads, Emulsion,

Amplification and Magnetics) technique, a reference method used in

re-analyses of historical trials like CRYSTAL (12) and OPUS (13), and studies, such as FIRE3 (14).

The ColoBEAM protocol evaluated the real-world

feasibility of liquid biopsy as a standard for detecting KRAS,

NRAS, and BRAF mutations, comparing genotyping results

from blood samples with those from routine FFPE tissue

specimens.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 278 patients, aged 18 or older, with

pathologically confirmed mCRC were enrolled in this study from

March 2016 to May 2017 at 8 medical centres (Institut de

Cancérologie de Lorraine, Vandœuvre-lès-Nancy, France; Polyclinique

de Gentilly, Nancy, France; Hôpital Belle-Isle-Metz, Metz, France;

Centre Paul Strauss, Strasbourg, France; CHU Reims Hôpital Robert

Debré, Reims, France; CH Auxerre, Auxerre, France; CH Chalon Sur

Saône-William Morey, Chalon sur Saône, France; CH Besançon-Hôpital

Jean Minjoz, Besançon, France). Eligible patients were adults (≥18

years) diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer. Inclusion

required that a molecular analysis of KRAS, NRAS, and

BRAF mutations be clinically indicated as part of routine

disease management. All participants provided written informed

consent prior to enrolment, and were covered by the French national

health insurance system. Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer

(mCRC) were eligible for inclusion if they had not received prior

anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy. This criterion was

established to ensure that the evaluation of RAS/BRAF mutational

status by BEAMing in plasma would reflect the untreated molecular

profile. As prior exposure to anti-EGFR agents may induce clonal

selection and alter the ctDNA landscape, excluding previously

treated patients was necessary to avoid potential confounding

effects on concordance analyses between tissue and liquid biopsy

results (15).

Exclusion criteria included non-metastatic CRC at

the time of initial tissue biopsy, local recurrence, exclusive

nodal metastases, contraindications to a 30 ml blood draw, receipt

of a blood transfusion within 15 days prior to blood collection,

other malignant tumours within the past 5 years, and pregnancy or

breastfeeding, and prior receipt of anti-EGFR therapy (n=4). Of the

included patients, 25 had no detectable metastases at the time of

blood sampling due to prior resection of metastatic lesions (e.g.

liver or lung metastases). Blood samples were collected without

strict timing constraints, including from patients who had received

chemotherapy or radiotherapy, to reflect real-world clinical

conditions.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics

Committee (CPP Est III, Nancy, France; number 15.09.09), and

written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The

protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02751177).

Procedures

DNA extracted from FFPE tissue, collected at the

time of the initial biopsy, was analysed for KRAS, NRAS and

BRAF mutations using PCR or next-generation sequencing (NGS)

assays at INCa platform, as per standard-of-care guidelines. At

inclusion, three 10 ml blood samples were collected in DNA BCT

tubes (Streck, La Vista, NE, USA). Sample collection lacked strict

timing constraints and, in some instances, occurred long after the

initial biopsy to reflect real-world conditions. The samples were

shipped at room temperature to the Biopathology Department of the

Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine for cell-free DNA (cfDNA)

extraction and centralized analysis, hereafter referred to as ‘ICL

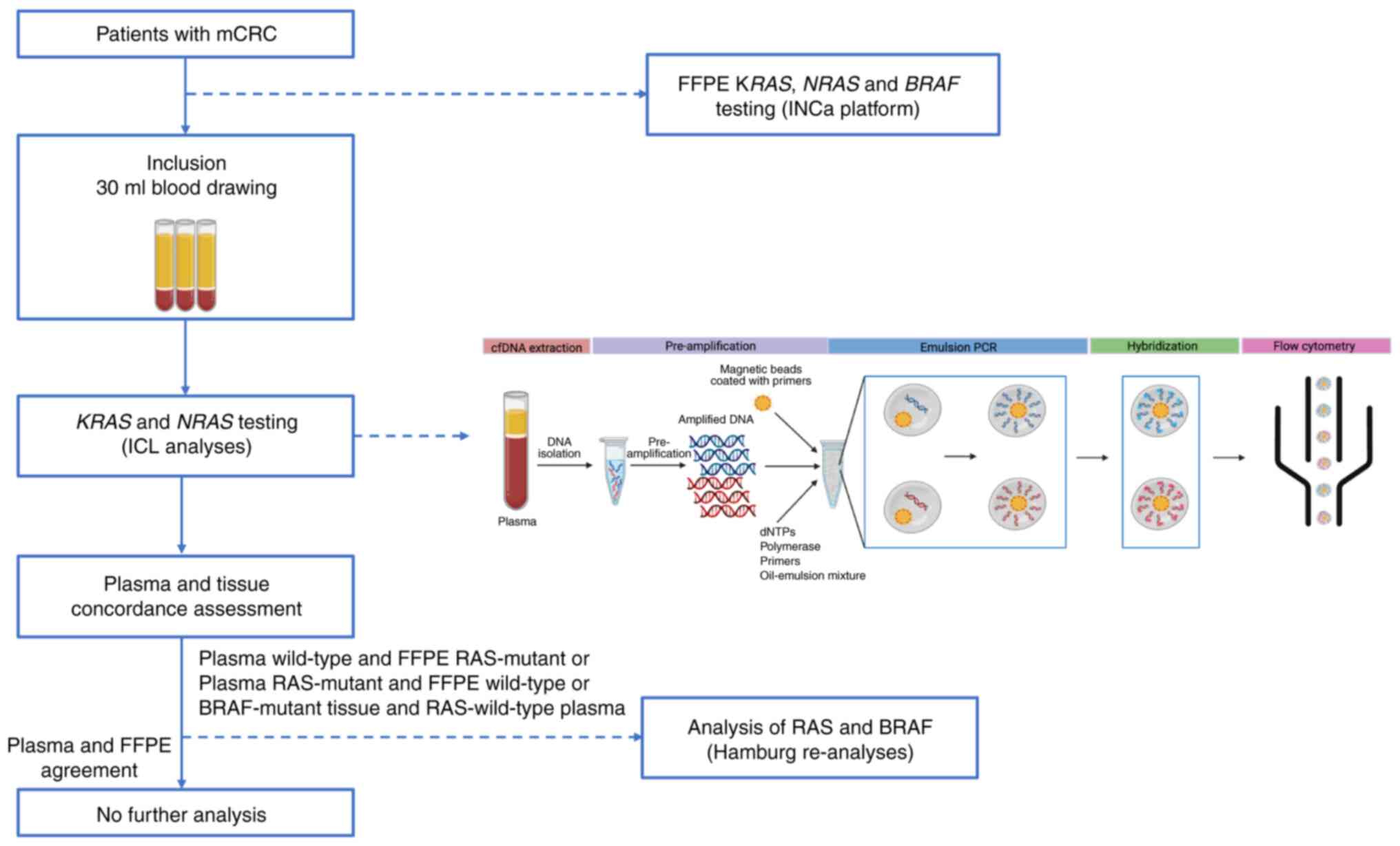

analyses’ (Fig. 1). Plasma was

obtained through double centrifugation (10 min at 1,600 × g,

followed by 10 min at 6,000 × g) and stored at −80°C until ctDNA

analysis. cfDNA was then extracted from 3–4 ml of plasma using the

QIAamp circulating nucleic acid kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and

analysed with the OncoBEAM™ assay (Sysmex, Norderstedt, Germany).

Plasma-derived RAS mutation results were then compared with

tissue-based results.

To ensure the robustness of mutational status

assignment and to resolve discordant cases, an independent blinded

re-analysis was conducted by the Sysmex service laboratory in

Hamburg-hereafter referred to as the ‘Hamburg re-analyses.’ This

laboratory served a dual role: it provided an external confirmation

of BRAF status (V600E mutation) for all relevant samples, and acted

as a fully blinded reference centre for the assessment of RAS

mutations, enabling an unbiased comparison with initial local

results. None of the named authors on the paper are affiliated with

Sysmex Inostics Inc., and the company did not have any input into

the planning or design of the experiments. The re-analysis focused

specifically on samples displaying discrepancies between tissue and

plasma results, including cases where i) the tumour tissue was

RAS-mutant but the corresponding plasma was wild-type (potential

false negatives), ii) the tumour was BRAF-mutant while plasma was

wild-type (potential false negatives), and iii) the tissue was RAS

wild-type but the plasma showed a RAS mutation (potential false

positives). For each of these cases, DNA was re-extracted from the

original FFPE tumour samples and ctDNA was isolated from a second

blood sample collected at the time of patient inclusion. Both DNA

sources were analysed in Hamburg using the BEAMing technology for

RAS and BRAF mutations. In the event of new discrepancies between

the initial analyses (‘ICL analyses’) and the Hamburg re-analyses,

the latter were considered the reference due to their blinded

nature and standardized quality procedures. The reconciled mutation

calls derived from this process were used as the final BEAMing

results in all statistical analyses, with FFPE tumour genotyping

from the INCa-certified platform consistently considered the gold

standard for tissue mutation status. This rigorous, multi-source

validation framework, based on blinded external testing with a

reference technology, ensured the reliability and clinical

relevance of the final dataset, particularly in evaluating the

performance of liquid biopsy in routine practice.

In accordance with routine clinical management of

metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), treatment response was

evaluated after three months using radiological imaging and

clinical assessment.

Data collection

All clinical and biological data at inclusion, along

with RAS and BRAF testing results, were recorded in

an electronic case report form (CleanWeb, Telemedicine

Technologies, Boulogne-Billancourt, France).

Samples analysis workflow

The sample analysis strategy is outlined in Fig. 1. All FFPE samples were analysed

using standard-of-care protocols established by INCa-certified

platforms, employing PCR-based or NGS-based assays (16–18).

RAS and BRAF results obtained from FFPE samples were

blinded to laboratory personnel during data analysis.

The BEAMing assay was used to analyse cfDNA samples,

targeting 34 mutations in codons 12, 13, 59, 61, 117, and 146 of

KRAS and NRAS gene. In brief, cfDNA underwent

pre-amplification, followed by emulsion PCR and hybridization, with

prepared samples analysed by flow cytometry per the manufacturer's

protocol.

Statistical analysis

Final BEAMing results for plasma samples were

determined after reconciling ICL analyses with Hamburg re-analyses.

FFPE tissue results from INCa-certified platforms served as the

gold standard. Mutation carriers were defined as patients with at

least one detected mutation in the KRAS, NRAS, or

BRAF genes. The sensitivity of the BEAMing test was

calculated as the proportion of mutation carriers identified by the

BEAMing test relative to those identified in FFPE samples, reported

with a 95% confidence interval.

Similarly, the specificity of the BEAMing assay was

calculated as the proportion of patients classified as non-mutation

carriers in plasma relative to those classified as non-mutation

carriers in FFPE samples, also reported with a 95% confidence

interval.

Results

Patient inclusion and sample

availability

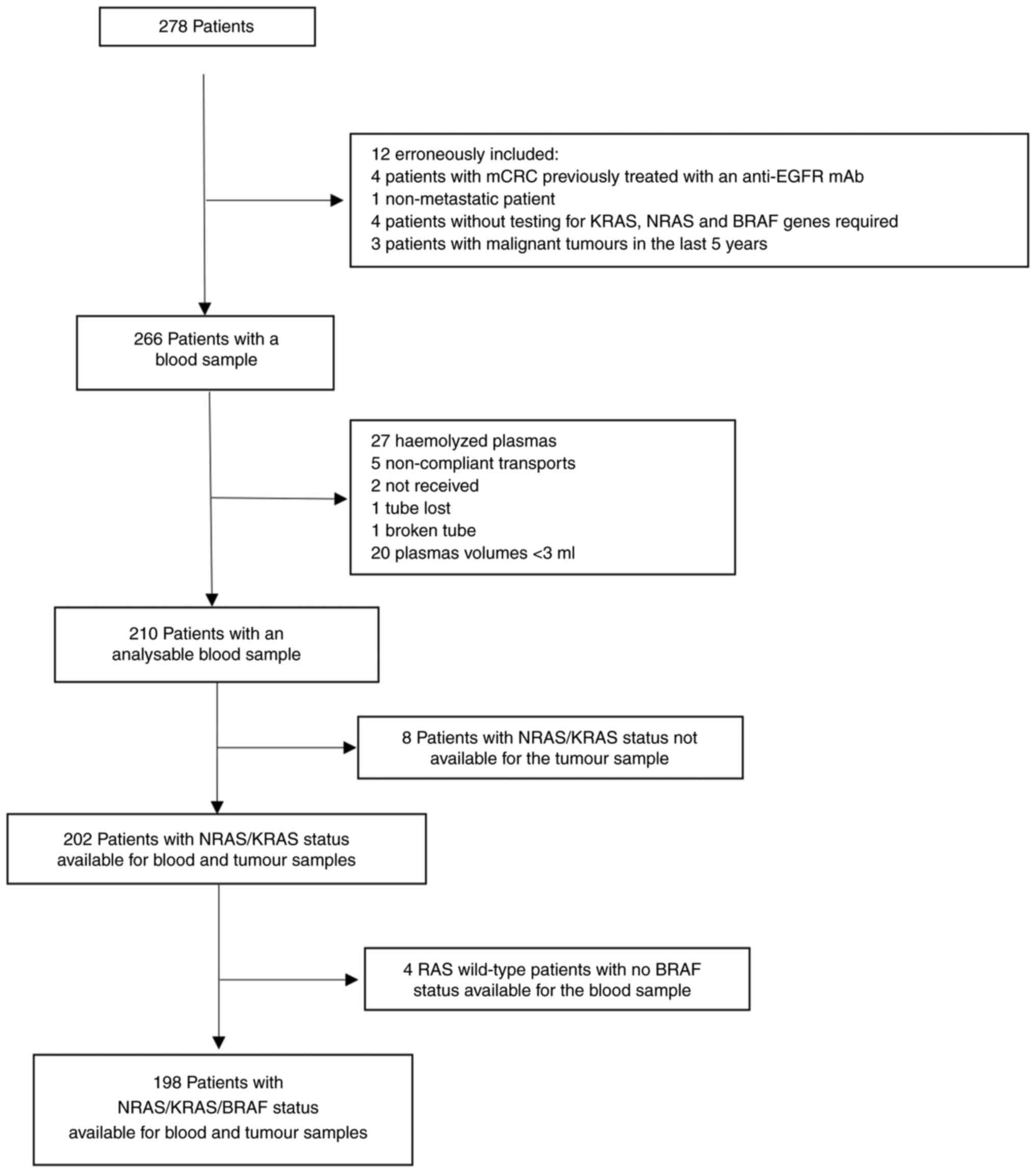

A total of 278 patients were initially enrolled in

the study. Twelve patients were excluded due to erroneous inclusion

(Fig. 2), resulting in a corrected

cohort of 266 patients. Among them, 56 blood samples were not

analysable due to failure to meet quality or processing criteria.

Of the remaining 210 patients with analysable blood samples,

KRAS/NRAS status from tumour tissue was unavailable in 8 cases.

Consequently, 202 patients had complete RAS genotyping data

available for both blood and tumour samples. Within this subgroup,

BRAF mutation status in plasma was unavailable for 4 patients,

resulting in 198 patients with complete RAS and BRAF data for both

sample types. In summary, 202 patients were included in the final

RAS concordance analysis and 198 patients in the combined RAS/BRAF

analysis (Fig. 2).

Discordant cases and external

re-analysis

After local testing (‘ICL analyses’), discordances

between plasma and tumour samples were identified in 50 patients

for NRAS status (refer to Data S1,

and Tables SI, SII and SIII). Among these, 46 patients had RAS

mutations detected in tumour tissue but classified as wild-type in

plasma (false negatives), and 4 patients had wild-type RAS in

tissue but were called mutated in plasma (false positives).

Additionally, 16 patients initially classified as RAS wild-type in

plasma by ICL were reclassified as RAS-mutated based on Hamburg

re-analyses.

Regarding the five BRAF-mutated tumour samples, BRAF

mutation status in plasma was confirmed in two cases, while data

were not available for two others (refer to Data S1).

Sample and tumour characteristics

Patient characteristics at the time of blood

sampling are detailed in Table I,

and the tumour sample availability is summarized in Table II. Among the 202 patients analysed,

the timing of blood collection relative to the initial tumour

biopsy was distributed as follows: 15.8% (n=32) within one month,

10.9% (n=22) between 1 and 3 months, 14.4% (n=29) between 3 months

and 1 year, 21.8% (n=44) between 1 and 2 years, 18.8% (n=38)

between 2 and 3 years, and 18.3% (n=37) three or more years after

biopsy.

| Table I.Study population characteristics at

the time of blood sampling of the 202 analysed patients. |

Table I.

Study population characteristics at

the time of blood sampling of the 202 analysed patients.

| Variable | Value |

|---|

| Median age,

yearsa | 67.0

(58.0–76.0) |

| Weight, kg

(median)a | 72.0

(62.0–83.0) |

|

Missing | 5 |

| Location, n

(%) |

|

|

Colon | 110 (54.5) |

|

Left | 18 (16.4) |

|

Right | 50 (45.5) |

|

Hinge | 34 (30.9) |

|

Transverse | 8 (7.3) |

|

Rectosigmoid junction | 30 (14.9) |

|

Rectum | 59 (29.2) |

|

Other | 3 (1.5) |

| Presence of

metastasis at the time of blood sampling, n (%) |

|

| No | 25 (12.4) |

|

Yes | 177 (87.6) |

| Number of

metastatic sites, n (%) |

|

| 0 | 25 (12.4) |

| 1 | 78 (38.6) |

|

>1 | 99 (49.0) |

| Metastasis location

(non-exclusive), n (%) (n=177) |

|

|

Liver | 127 (62.9) |

|

Pulmonary | 94 (46.5) |

|

Peritoneal | 45 (22.3) |

| Ganglionary | 36 (17.8) |

|

Bone | 10 (5.0) |

|

Brain | 3 (1.5) |

|

Other | 15 (7.4) |

|

Chemotherapyb, n (%) |

|

|

Naive | 59 (29.2) |

|

Undergoing | 94 (46.5) |

|

Finished | 49 (24.3) |

| Chemotherapy

administration, n (%) (n=143) |

|

| Within

15 days of blood collection | 29 (20.9) |

| >15

days from blood collection | 110 (79.1) |

|

Missing | 4 |

| Primary tumour, n

(%) |

|

|

Present | 70 (34.7) |

|

Eradicated after

treatment | 132 (65.3) |

| Table II.Tumour sample description

(n=202). |

Table II.

Tumour sample description

(n=202).

| Variable | Value |

|---|

| Nature of tissue, n

(%) |

|

|

Biopsy | 89 (44.1) |

| Surgery

specimen | 113 (55.9) |

| Tumour type, n

(%) |

|

| Primary

tumour | 164 (81.2) |

|

Metastasis | 38 (18.8) |

| Tumour cell

content, %a | 50 (30–70) |

| Routine results

from INCa platform, n (%) |

|

| Known

mutation status (FFPE tissue) | 202 (100) |

| KRAS

or NRAS gene mutation |

|

|

Mutated | 132 (65.4) |

|

Wild-type | 70 (34.6) |

|

BRAF gene mutation |

|

|

Mutated | 5 (2.5) |

|

Wild-type | 197 (97.5) |

|

KRAS/NRAS/BRAF gene mutation |

|

|

Mutated | 137 (67.8) |

|

Wild-type | 65 (32.2) |

Primary endpoint and overall

performance

The comparison of BEAMing plasma genotyping results

with tumour tissue genotyping from INCa-certified platforms is

presented in Table III. The

study's primary objective-evaluating the accuracy of BEAMing for

detecting KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations using tumour genotyping as

the reference-was achieved. For RAS mutation detection, the

sensitivity was 77.3%, specificity was 94.3%, and overall

concordance was 83.2%. For combined RAS and BRAF mutations,

sensitivity was 77.0%, specificity 93.7%, and concordance 82.3%.

Despite high specificity (>93%) across analyses, overall

sensitivity remained moderate when evaluating tumour vs. plasma

mutation status globally.

| Table III.KRAS, NRAS and BRAF

mutational status in plasma samples determined by beads emulsion

and magnetic digital PCR, compared with tumour genotyping performed

on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples at the French National

Cancer Institute platform, used as the reference standard. |

Table III.

KRAS, NRAS and BRAF

mutational status in plasma samples determined by beads emulsion

and magnetic digital PCR, compared with tumour genotyping performed

on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples at the French National

Cancer Institute platform, used as the reference standard.

| Mutations | No. of

patients | TP, n | TN, n | FN, n | FP, n | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Concordance, % | Kappa (95% CI) |

|---|

| RAS | 202 | 102 | 66 | 30 | 4 | 77.3 | 94.3 | 83.2 | 0.658

(0.557–0.759) |

| RAS +

BRAF | 198 | 104 | 59 | 31 | 4 | 77.0 | 93.7 | 82.3 | 0.634

(0.529–0.740) |

Subgroup analyses

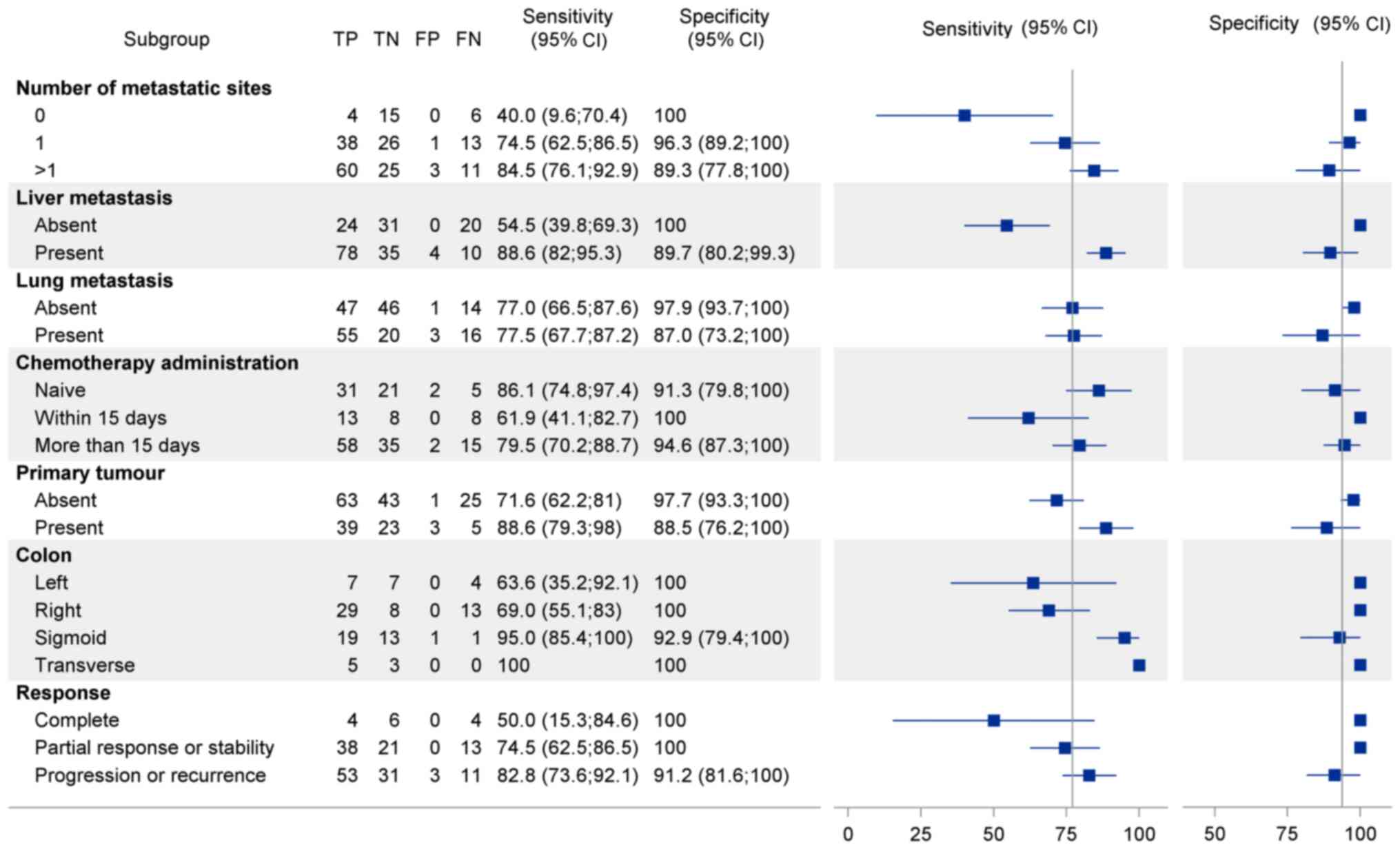

Subgroup analyses are shown in Fig. 3 and account for key clinical

parameters at the time of blood sampling, including tumour

presence, metastatic status and location, chemotherapy exposure,

and treatment response.

Metastatic status and tumour

presence

Sensitivity improved significantly in patients with

liver metastases (sensitivity, 88.6%; specificity, 89.7%) and in

those with a visible primary tumour (sensitivity, 88.6%;

specificity, 88.5%). In contrast, patients without metastases

showed limited sensitivity (50.0%), while those with metastases had

improved sensitivity (75.0%), which increased with the number of

metastatic sites. Metastatic site analysis revealed higher

sensitivity for liver metastases (~88%) than for pulmonary

metastases (77%).

Tumour location

Sensitivity also varied with primary tumour

location: 100% for transverse colon, 95% for sigmoid, 69% for left

colon, and 63% for right colon tumours.

Chemotherapy exposure

BEAMing sensitivity was highest in

chemotherapy-naive patients (sensitivity, 86.1%; specificity,

91.3%) and declined with recent chemotherapy. Sensitivity was

acceptable (79.0%) when chemotherapy was administered more than 15

days before sampling but dropped to 61.0% when treatment occurred

within 15 days.

Treatment response

Sensitivity was highest in patients with progressive

or recurrent disease (82.8%), intermediate in those with stable

disease or partial response (74.5%), and lowest in patients

achieving complete response (50.0%). Regardless of response status,

specificity remained excellent (91.2 to 100%).

Discussion

The ColoBEAM study was designed as a real-world

study to evaluate the feasibility of using liquid biopsy to detect

KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations in patients with mCRC,

potentially replacing tissue biopsy. Each patient underwent routine

tissue analysis, with plasma derived from whole blood analysed

using the OncoBEAMTM assay (19,20).

Compared to previous studies, such as the prospective multicentre

real-world comparison of OncoBEAM-based liquid biopsy and tissue

analysis for RAS mutations in mCRC (21), or a multi-institutional study

(22), the ColoBEAM study provides

additional insights by simultaneously assessing RAS and

BRAF mutations in ctDNA from mCRC patients.

Of the 278 enrolled patients, data from 202 patients

with RAS status and 198 patients with both RAS and

BRAF status were analysed (4 patients with wild-type

RAS lacked BRAF status in plasma samples, as shown in

Fig. 2) after exclusions. To assess

concordance, results were compared, with discordant cases sent to

Sysmex in Germany for blinded external re-analysis. Some samples

were excluded due to quality issues, such as haemolysis during

transport.

This study evaluated BEAMing for detecting KRAS,

NRAS, and BRAF mutations in plasma from 202 CRC patients, achieving

a sensitivity of 77.3%, specificity of 94.3%, and concordance of

83.2% for RAS mutations, with similar metrics for combined RAS/BRAF

analysis (sensitivity 77.0%, specificity 93.7%, concordance 82.3%).

Compared to studies using various liquid biopsy methods, our

sensitivity is slightly lower than Bettegowda et al

(23) at 87.2% with digital PCR in

CRC, likely due to our mixed cohort including non-metastatic cases,

and Thierry et al (24) at

85% in metastatic CRC (mCRC). Focusing on BEAMing-specific studies,

García-Foncillas et al (21)

reported 93.3% concordance for OncoBEAM RAS testing in mCRC, and

Vivancos et al (25) found

89% concordance (kappa 0.770) in 236 mCRC patients, with

re-analysis improving to 92%; our lower sensitivity in

non-metastatic cases (50.0%) and post-chemotherapy settings echoes

Grasselli et al (26) on

reduced BEAMing sensitivity with lower tumour burden. The ColoBEAM

study provides unique value by simultaneously evaluating KRAS,

NRAS, and BRAF mutations in a real-world setting with a

diverse patient cohort, including non-metastatic cases, which may

explain the slightly lower concordance (83.2% for RAS mutations)

compared to Vidal et al (27) (93%) and García-Foncillas et

al (21) (89%). These studies

primarily focused on metastatic patients, whereas our broader

inclusion criteria likely introduced variability in ctDNA shedding,

impacting sensitivity, as noted in our subgroup analyses (e.g.,

50.0% sensitivity in non-metastatic cases vs. 88.6% in patients

with liver metastases). The high specificity (>93%) supports

BEAMing's reliability for ruling out mutations, as seen in Bando

et al (28) with 90.4%

positive agreement, reinforcing its utility for guiding anti-EGFR

therapy in mCRC.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the presence of

metastases aligns with existing literature, which indicates that

patients with disease progression exhibit higher ctDNA levels,

enhancing the sensitivity and effectiveness of ctDNA detection

(29–31). In our study, the concordance between

KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutation status in ctDNA and FFPE

tissue was higher in patients with progressive disease or liver

metastases (sensitivity, 82.8%; specificity, 91.2%), consistent

with prior findings (21),

reporting greater concordance in patients with liver metastases

(94.5–94.8%) comparted to those without (83.8%; P=0.040). The ‘lung

metastasis’ subgroup, consisting of patients with unique lung

metastases only, showed the lowest concordance rate of 68.8%. The

inclusion of 25 patients with no detectable metastases at the time

of blood sampling, due to prior resection of metastatic lesions,

likely contributed to the lower overall concordance (83.2% for RAS

mutations) compared to studies focused exclusively on patients with

active metastases (27). These

patients exhibited a reduced sensitivity of 50.0% for detecting

KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations in plasma (Fig. 3), likely due to decreased

circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) shedding in the absence of

metastatic burden, as supported by prior studies (32). This finding highlights the influence

of metastatic status on the performance of liquid biopsy and

underscores the need to consider disease stage when implementing

the BEAMing assay in real-world clinical settings.

These findings have significant implications,

supporting the strategic timing of blood-based mutation testing,

ideally before treatment initiation as per current guidelines, to

maximize sensitivity and clinical utility. The differential

sensitivity in chemotherapy-naive patients vs. those receiving

chemotherapy suggests a dynamic interplay between treatment and

ctDNA release or clearance.

Although ctDNA offers high specificity, cfDNA

profiling has broader applications, reflecting diverse cellular

process in the body. This precision medicine strategy supports

liquid biopsy not only as a potential alternative to tissue biopsy

but also as a complementary tool that captures the temporal and

spatial heterogeneity of tumours. As demonstrated in lung and

breast cancer, ctDNA mutation tracking has proven effective for

guiding therapeutic adjustments throughout disease progression

(33,34).

Our findings are consistent highlighting the utility

of circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) as a highly specific biomarker

for cancer detection, disease progression monitoring, adjuvant

therapy guidance, and potentially reducing unnecessary toxicity

(35). Notably, studies such as

CIRCULATE-Japan have established a foundation for understanding

liquid biopsy in cancer treatment and recurrence monitoring

(36).

Despite the promising results, this study

acknowledges limitations, including the influence of recent

chemotherapy and metastatic burden on test sensitivity. Another

notable limitation of our study was the exclusion of 56 out of 266

blood samples (21%) due to preanalytical issues, such as haemolysis

or insufficient blood volume, despite the use of DNA BCT tubes

designed to stabilize cfDNA. These issues were likely exacerbated

by initial sample transport at room temperature and, in some

instances, accidental freezing during shipment, which compromised

sample integrity. These challenges, observed in our multicentre

real-world setting, highlight the critical need for standardized

preanalytical protocols, including controlled transport conditions

to prevent temperature fluctuations, to ensure reliable ctDNA

analysis. Future studies should prioritize optimized sample

collection, handling, and transport workflows to minimize such

issues and enhance the clinical applicability of liquid biopsy

techniques like the BEAMing assay.

A notable finding in our study was the

reclassification of 16 patients from RAS wild-type to RAS-mutated

in plasma following centralized re-analysis in Hamburg,

highlighting differences in sensitivity between local (ICL) and

centralized analyses. Several factors may explain this discrepancy.

First, the Hamburg laboratory, as a centralized facility with

extensive experience in OncoBEAM™ assay implementation, likely

benefited from optimized workflows and greater technical expertise,

enhancing mutation detection. Second, the Hamburg re-analysis may

not have strictly followed the same procedure as the local ICL

analyses, with potential differences in assay optimization or

quality control measures. These findings underscore the importance

of centralized laboratory expertise and standardized procedures to

maximize the sensitivity of ctDNA analysis in real-world settings.

Another limitation of our study is that only discrepant cases

underwent re-analysis using BEAMing. It is therefore possible that

additional discrepancies would have been identified if all samples

had been retested, particularly in cases classified as RAS

or BRAF wild-type in tissue. The higher sensitivity of

BEAMing may have revealed ultra-low frequency subclonal mutations,

potentially leading to a reclassification and further highlighting

the complexity of tumour heterogeneity.

The timing of blood collection relative to initial

tissue biopsy may also influence the concordance between plasma and

tissue-based mutation detection, as tumour evolution or changes in

circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) shedding could occur over time. In

our study, blood sampling occurred at varying intervals post-biopsy

(15.8% within one month, 21.8% between 1 and 2 years, and 18.3%

three or more years, as shown in Table

I), reflecting the real-world setting of the ColoBEAM study.

While we did not perform a specific statistical analysis of this

variable's impact, longer intervals may contribute to discordance

due to tumour heterogeneity or disease progression, particularly in

patients with mCRC. This observation aligns with prior studies

suggesting that temporal discrepancies between tissue and plasma

sampling can affect ctDNA detection (15). Future studies should quantify the

impact of sampling timing on concordance to optimize liquid biopsy

protocols, particularly in real-world clinical settings.

Integrating ctDNA analysis with other biomarkers,

such as microsatellite instability (MSI) status (6), could facilitate the development of

innovative checkpoint inhibitor therapies (37,38).

This synergy may advance the identification of a comprehensive set

of routine biomarkers to support personalized medicine.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that

blood-based testing for detecting mutations in patients with mCRC

is feasible. Although the test exhibited high accuracy in

identifying mutations compared to tissue biopsies, factors such as

recent chemotherapy and tumour location may reduce its sensitivity.

However, adherence to guideline recommendations (4), may mitigate these limitations, as

testing is ideally performed before treatment initiation to

minimize the impact of factors like recent chemotherapy. ctDNA

analysis is now included in guidelines for CRC progression after

therapy, at diagnosis in patients with limited access to tissue

biopsies, or when tissue specimens are inadequate due to

insufficient quantity or quality or are unavailable for molecular

analysis (39). Despite these

limitations, our results indicate that blood-based mutation testing

provides a less invasive and valuable option in real-world

settings.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Frederick S.

Jones and Dr Dan Edelstein from Sysmex Inostics Inc (Baltimore, MD,

USA) for their support in facilitating the contractual arrangements

and organizing the Hamburg re-analyses.

Funding

The present study was supported by a research collaboration

agreement between Sysmex Inostics Inc. and the Institut de

Cancérologie de Lorraine, under which kits were provided.

Additional support came from the private research fund of the

Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AH, AL and JLM wrote the original protocol, analysed

the data and wrote the manuscript. CG was the principal

investigator. CG, OB, MBA, JP, DS, AB, FG, ALV and CB were

investigators. CG, OB, MBA, JP, DS, AB, FG, ALV, CB and PG

contributed to data acquisition and critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. MR and MH analysed

the samples. JS analysed the data and all statistics. AH and JS

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All patients gave their informed and written consent

to participate. The study is registered under number NCT02751177

and has been approved by the ethical committee Comité de Protection

des Personnes Est (CHRU de Nancy, Hôpital de Brabois,

Vandoeuvre-Lès-Nancy, France) under the number 15.09.09, ID RCB

2015-A01272-47.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools (OpenAI Chat GPT 4.0) were used to improve the

readability and language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the

authors revised and edited the content produced by the artificial

intelligence tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BEAMing

|

beads emulsion and magnetics digital

PCR

|

|

cfDNA

|

cell-free DNA

|

|

ctDNA

|

circulating tumour DNA

|

|

FFPE

|

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

|

|

INCa

|

Institut National du Cancer (French

National Cancer Institute)

|

|

mCRC

|

metastatic colorectal cancer

|

|

NCT

|

National Clinical Trial

|

|

NGS

|

next-generation sequencing

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA

and Jemal A: Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin.

73:233–254. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dyba T, Randi G, Bray F, Martos C, Giusti

F, Nicholson N, Gavin A, Flego M, Neamtiu L, Dimitrova N, et al:

The European cancer burden in 2020: Incidence and mortality

estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers. Eur J Cancer.

157:308–347. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cervantes A, Adam R, Roselló S, Arnold D,

Normanno N, Taïeb J, Seligmann J, De Baere T, Osterlund P, Yoshino

T, et al: Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice

Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

34:10–32. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tabernero J, Grothey A, Van Cutsem E,

Yaeger R, Wasan H, Yoshino T, Desai J, Ciardiello F, Loupakis F,

Hong YS, et al: Encorafenib Plus Cetuximab as a new standard of

care for previously treated BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic colorectal

cancer: Updated survival results and subgroup analyses from the

BEACON study. J Clin Oncol. 39:273–284. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Santini D, Botticelli A, Galvano A,

Iuliani M, Incorvaia L, Gristina V, Taffon C, Foderaro S,

Paccagnella E, Simonetti S, et al: Network approach in liquidomics

landscape. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:1932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lièvre A, Merlin JL, Sabourin JC, Artru P,

Tong S, Libert L, Audhuy F, Gicquel C, Moureau-Zabotto L, Ossendza

RA, et al: RAS mutation testing in patients with metastatic

colorectal cancer in French clinical practice: A status report in

2014. Dig Liver Dis. 50:507–512. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Thomsen CB, Hansen TF, Andersen RF,

Lindebjerg J, Jensen LH and Jakobsen A: Monitoring the effect of

first line treatment in RAS/RAF mutated metastatic colorectal

cancer by serial analysis of tumor specific DNA in plasma. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 37:552018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Allegretti M, Cottone G, Carboni F,

Cotroneo E, Casini B, Giordani E, Amoreo CA, Buglioni S, Diodoro M,

Pescarmona E, et al: Cross-sectional analysis of circulating tumor

DNA in primary colorectal cancer at surgery and during post-surgery

follow-up by liquid biopsy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:692020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Taly V, Pekin D, Benhaim L, Kotsopoulos

SK, Le Corre D, Li X, Atochin I, Link DR, Griffiths AD, Pallier K,

et al: Multiplex picodroplet digital PCR to detect KRAS mutations

in circulating DNA from the plasma of colorectal cancer patients.

Clin Chem. 59:1722–1731. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Thierry AR, Mouliere F, El Messaoudi S,

Mollevi C, Lopez-Crapez E, Rolet F, Gillet B, Gongora C, Dechelotte

P, Robert B, et al: Clinical validation of the detection of KRAS

and BRAF mutations from circulating tumor DNA. Nat Med. 20:430–435.

2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Köhne CH, Heinemann

V, Tejpar S, Melezínek I, Beier F, Stroh C, Rougier P, van Krieken

JH and Ciardiello F: Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus

cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 33:692–700. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Hartmann JT, de

Braud F, Schuch G, Zubel A, Celik I, Schlichting M and Koralewski

P: Efficacy according to biomarker status of cetuximab plus

FOLFOX-4 as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer:

The OPUS study. Ann Oncol. 22:1535–1546. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T,

Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, Al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Lerchenmüller

C, Kahl C, Seipelt G, et al: FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI

plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with

metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): A randomised, open-label,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15:1065–1075. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S and

Bardelli A: Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of

cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:531–548. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Franczak C, Witz A, Geoffroy K, Demange J,

Rouyer M, Husson M, Massard V, Gavoille C, Lambert A, Gilson P, et

al: Evaluation of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations detection in plasma

using an automated system for patients with metastatic colorectal

cancer. PLoS One. 15:e02272942020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Franczak C, Dubouis L, Gilson P, Husson M,

Rouyer M, Demange J, Leroux A, Merlin JL and Harlé A: Integrated

routine workflow using next-generation sequencing and a

fully-automated platform for the detection of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF

mutations in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded samples with poor DNA

quality in patients with colorectal carcinoma. PLoS One.

14:e02128012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Witz A, Dardare J, Betz M, Gilson P,

Merlin JL and Harlé A: Tumor-derived cell-free DNA and circulating

tumor cells: Partners or rivals in metastasis formation? Clin Exp

Med. 24:22024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski

J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D'Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G,

et al: Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for

metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 360:1408–1417. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A,

Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G,

Stroh C, et al: Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and

without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:663–671. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

García-Foncillas J, Tabernero J, Élez E,

Aranda E, Benavides M, Camps C, Jantus-Lewintre E, López R,

Muinelo-Romay L, Montagut C, et al: Prospective multicenter

real-world RAS mutation comparison between OncoBEAM-based liquid

biopsy and tissue analysis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J

Cancer. 119:1464–1470. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Osumi H, Takashima A, Ooki A, Yoshinari Y,

Wakatsuki T, Hirano H, Nakayama I, Okita N, Sawada R, Ouchi K, et

al: A multi-institutional observational study evaluating the

incidence and the clinicopathological characteristics of NeoRAS

wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Transl Oncol.

35:1017182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I,

Wang Y, Agrawal N, Bartlett BR, Wang H, Luber B, Alani RM, et al:

Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human

malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 6:224ra242014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Thierry AR, El Messaoudi S, Mollevi C,

Raoul JL, Guimbaud R, Pezet D, Artru P, Assenat E, Borg C,

Mathonnet M, et al: Clinical utility of circulating DNA analysis

for rapid detection of actionable mutations to select metastatic

colorectal patients for anti-EGFR treatment. Ann Oncol.

28:2149–2159. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vivancos A, Aranda E, Benavides M, Élez E,

Gómez-España MA, Toledano M, Alvarez M, Parrado MRC,

García-Barberán V and Diaz-Rubio E: Comparison of the clinical

sensitivity of the Idylla platform and the OncoBEAM RAS CRC assay

for KRAS Mutation detection in liquid biopsy samples. Sci Rep.

9:89762019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Grasselli J, Elez E, Caratù G, Matito J,

Santos C, Macarulla T, Vidal J, Garcia M, Viéitez JM, Paéz D, et

al: Concordance of blood- and tumor-based detection of RAS

mutations to guide anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal

cancer. Ann Oncol. 28:1294–1301. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Vidal J, Muinelo L, Dalmases A, Jones F,

Edelstein D, Iglesias M, Orrillo M, Abalo A, Rodríguez C, Brozos E,

et al: Plasma ctDNA RAS mutation analysis for the diagnosis and

treatment monitoring of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann

Oncol. 28:1325–1332. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bando H, Kagawa Y, Kato T, Akagi K, Denda

T, Nishina T, Komatsu Y, Oki E, Kudo T, Kumamoto H, et al: A

multicentre, prospective study of plasma circulating tumour DNA

test for detecting RAS mutation in patients with metastatic

colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 120:982–986. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Velimirovic M, Juric D, Niemierko A,

Spring L, Vidula N, Wander SA, Medford A, Parikh A, Malvarosa G,

Yuen M, et al: Rising circulating tumor DNA as a molecular

biomarker of early disease progression in metastatic breast cancer.

JCO Precis Oncol. 4:1246–1262. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mauri G, Vitiello PP, Sogari A, Crisafulli

G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Marsoni S, Siena S and Bardelli A: Liquid

biopsies to monitor and direct cancer treatment in colorectal

cancer. Br J Cancer. 127:394–407. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Loupakis F, Sharma S, Derouazi M, Murgioni

S, Biason P, Rizzato MD, Rasola C, Renner D, Shchegrova S, Koyen

Malashevich A, et al: Detection of molecular residual disease using

personalized circulating tumor DNA assay in patients with

colorectal cancer undergoing resection of metastases. JCO Precis

Oncol. 5:PO.21.00101. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K,

Goodman S, Li M, Thornton K, Agrawal N, Sokoll L, Szabo SA, et al:

Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med.

14:985–990. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Turner NC, Swift C, Jenkins B, Kilburn L,

Coakley M, Beaney M, Fox L, Goddard K, Garcia-Murillas I, Proszek

P, et al: Results of the c-TRAK TN trial: A clinical trial

utilising ctDNA mutation tracking to detect molecular residual

disease and trigger intervention in patients with moderate- and

high-risk early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol.

34:200–211. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Powles T, Assaf ZJ, Davarpanah N,

Banchereau R, Szabados BE, Yuen KC, Grivas P, Hussain M, Oudard S,

Gschwend JE, et al: ctDNA guiding adjuvant immunotherapy in

urothelial carcinoma. Nature. 595:432–743. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tie J, Cohen JD, Lahouel K, Lo SN, Wang Y,

Kosmider S, Wong R, Shapiro J, Lee M, Harris S, et al: Circulating

tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon

cancer. N Engl J Med. 386:2261–2272. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Taniguchi H, Nakamura Y, Kotani D, Yukami

H, Mishima S, Sawada K, Shirasu H, Ebi H, Yamanaka T, Aleshin A, et

al: CIRCULATE-Japan: Circulating tumor DNA-guided adaptive platform

trials to refine adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. Cancer

Sci. 112:2915–2920. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

André T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, Jensen BV,

Jensen LH, Punt C, Smith D, Garcia-Carbonero R, Benavides M, Gibbs

P, et al: Pembrolizumab in microsatellite-instability-high advanced

colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 383:2207–2218. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR,

Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, et

al: PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl

J Med. 372:2509–2520. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pascual J, Attard G, Bidard FC, Curigliano

G, Mattos-Arruda LD, Diehn M, Italiano A, Lindberg J, Merker JD,

Montagut C, et al: ESMO recommendations on the use of circulating

tumour DNA assays for patients with cancer: A report from the ESMO

Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol. 33:750–768. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|