Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is one of the most common primary

malignant bone tumors in children and young adults, and its

occurrence and development are influenced by various factors. In

recent years, advancements in the understanding of OS and the

refinement of therapeutic approaches have led to an increase in the

5-year survival rate for patients with tumors, now ranging from 60

to 80% (1). Nevertheless, the

mortality rate associated with OS remains elevated compared with

other malignant bone tumors, particularly among patients with

metastatic or recurrent OS, where the long-term survival rate

frequently falls below 30% (2).

OS tumors develop within a multifaceted and

dynamically evolving tumor microenvironment (TME) that encompasses

bone cells, stromal cells, vascular cells, immune cells and a

mineralized extracellular matrix (ECM). The intricate interactions

between OS cells and their surrounding microenvironment are

critical in influencing various aspects of tumor biology, including

progression, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis and

responses to therapeutic interventions (3). The TME is not a passive bystander but

an active participant in oncogenesis; it provides critical support

for tumor cell growth and dissemination and promotes the

maintenance of the malignant phenotype through key mechanisms such

as immune evasion, induction of angiogenesis and metabolic

reprogramming (4).

Specific components of the OS TME, including

osteocytes, tumor-associated immune cells, bone marrow (BM)

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and the ECM, interact to create a

hypoxic and vascularized niche conducive to proliferation and

metastasis (5). Recognition of the

pivotal role of the TME has driven the development of novel

therapeutic strategies. For instance, inhibitors targeting

immunosuppressive cells or immune checkpoints have achieved

breakthroughs in certain solid tumors and are being explored in OS

clinical trials (6). Additionally,

approaches such as targeting cytokines secreted by

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) or blocking abnormal

angiogenesis are under investigation as potential combination

therapies to enhance traditional treatment efficacy (7). Although still in the early stages,

these TME-targeted therapies hold promise to overcome

chemoresistance and improve survival.

The present review addresses the multiple roles of

the TME in OS development, examining how its various components

influence tumor proliferation, metastasis and treatment response;

it also discusses the emerging paradigm of targeting the TME,

highlighting the need for further research into its heterogeneity

to disrupt the pro-tumorigenic cycle and offer new hope for

patients with OS.

TME of OS

OS tumors arise within a complex and dynamic

microenvironment that comprises both cellular and non-cellular

components. This environment consists of a heterogeneous population

of bone cells, which includes osteoblasts (OBs), osteoclasts and

osteocytes, alongside stromal cells such as MSCs and fibroblasts.

Furthermore, it encompasses vascular cells, including endothelial

cells and pericytes, as well as immune cells, which comprise BM

cells and lymphocytes, in addition to a mineralized ECM (8).

Under typical physiological conditions, the

interactions among bone, vascular and stromal cells occur through

paracrine signaling and cellular communication, which are essential

for maintaining bone homeostasis (8). BM cells represent the primary cell

type within TME of OS (8). Recent

single-cell analyses have uncovered a multitude of ligand-receptor

interactions among OS tumors, BM and OBs, leading to the

identification of 21 ligand-receptor gene pairs that exhibit a

significant correlation with survival outcomes (9). The TME not only fosters a conducive

environment for the proliferation of tumor cells but also secretes

various factors, including cytokines, chemokines and growth

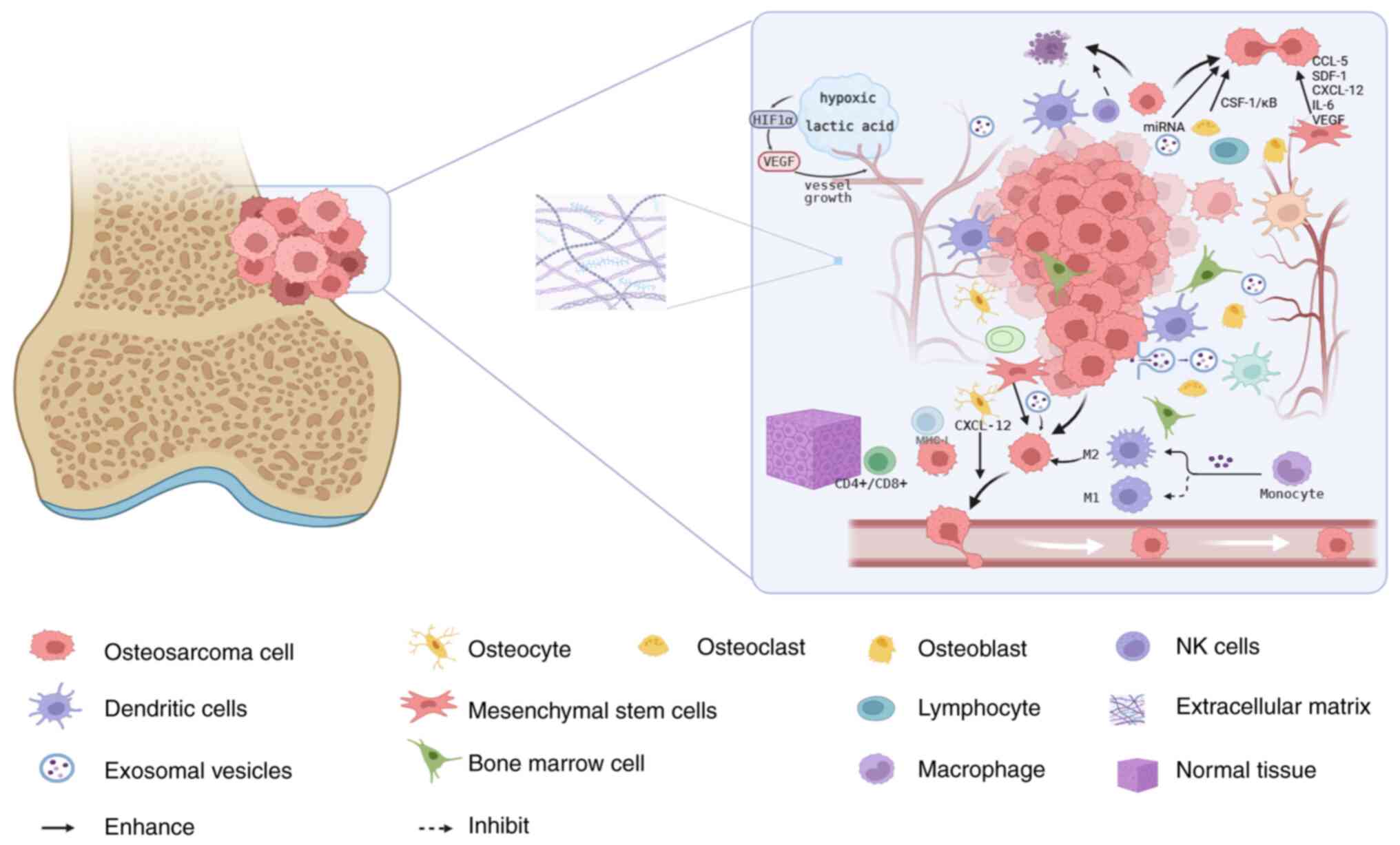

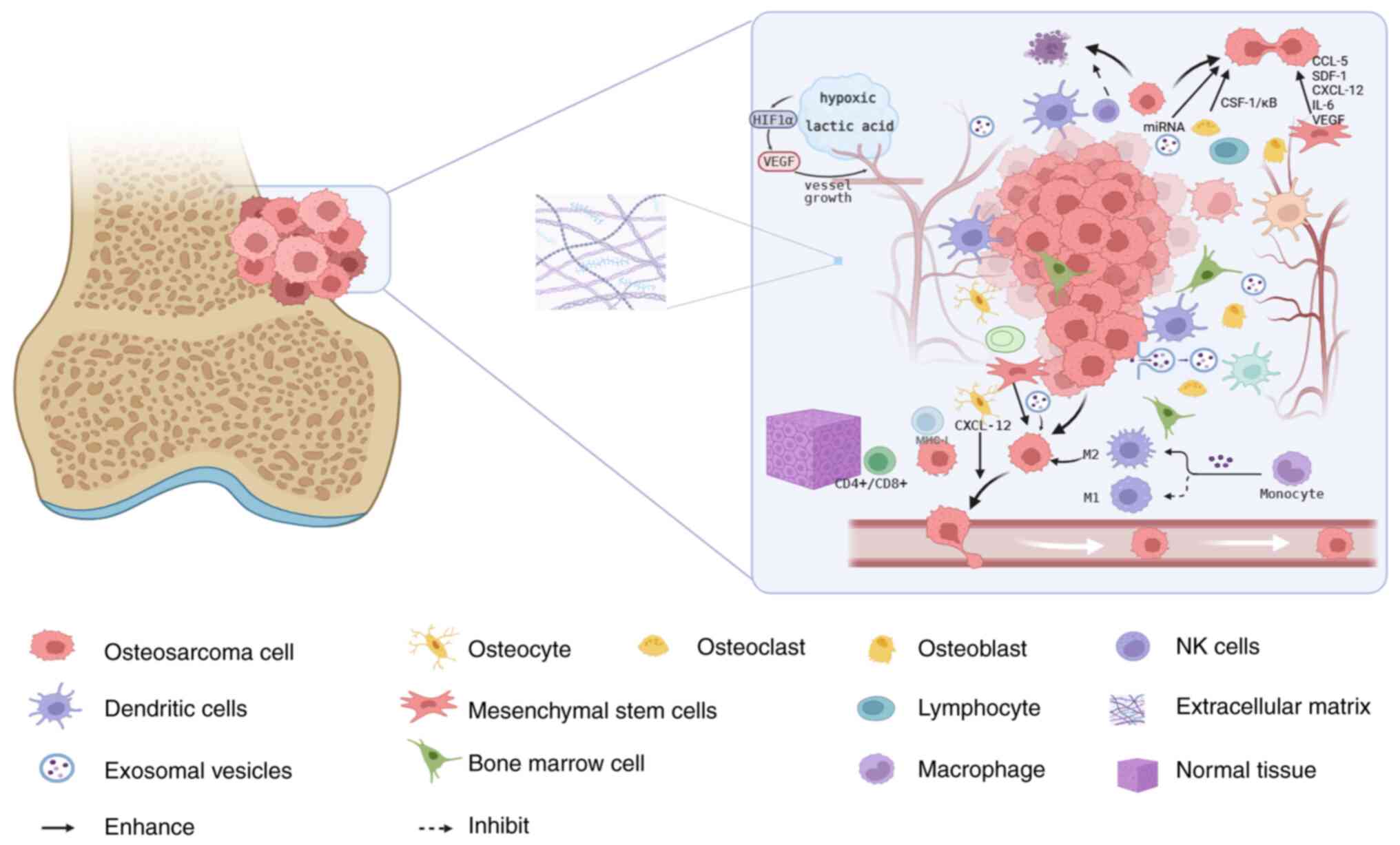

factors, which facilitate tumor cell metastasis (8). Fig. 1

illustrates the complex composition of the OS TME, encompassing

major cellular components such as osteocytes, stromal cells and

immune cells, alongside non-cellular elements including the ECM,

vascular networks and hypoxic conditions; it also depicts

interactions between tumor cells and select components within the

OS TME.

| Figure 1.Microenvironment of osteosarcoma is

composed of cellular and non-cellular components, including bone

cells (osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes), stromal cells

(mesenchymal stem cells and fibroblasts), immune cells (bone marrow

and lymphocytes), mineralized ECM, rich microcirculation vessels

and a hypoxic environment. Other components include CTCs, EVs and

various signaling molecules. The tumor microenvironment not only

provides a favorable growth environment for tumor cells, but also

secretes various factors, including various cytokines, chemokines

and growth factors, promoting tumor cell metastasis. The figure was

created by BioRender. OSc, osteosarcoma cell; Ocytes, osteocyte;

OCs, osteoclast; OBs, osteoblast; TAMs, tumor-associated

macrophages; DCs, dendritic cells; MST, mesenchymal stem cell;

Lymph, lymphocyte; ECM, extracellular matrix; EV, exosomal

vesicles; BMC, bone marrow cell; NT, normal tissue; MSC,

multipotent stem cell; CTCs, circulating tumor cells. |

Osteocytes

Osteocytes constitute an essential element of the

bone microenvironment, which encompasses three principal categories

of bone cells: OBs, osteoclasts and osteocytes. These cells

interact with stromal and immune cells by secreting a variety of

cytokines and chemokines that facilitate tumor growth, invasion and

metastasis. OBs originate from multipotent MSCs, and their

development can be augmented by particular cytokines, including

interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-13 (8). Conversely, their function may be

inhibited by factors including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α,

TNF-β, IL-1, IFN-α, IL-4 and IL-7 (10). OBs also have a notable role in

influencing the formation, differentiation or apoptosis of

osteoclasts through various signaling pathways, including the

osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

(RANKL)/receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK),

RANKL/leucine-rich repeats containing G protein-coupled receptor

4/RANK, Ephrin 2/ephB4 and Fas/FasL pathways (11). Osteocytes can secrete a variety of

soluble factors, including growth differentiation factor 15, TGF-β,

chemokines CXC-motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 1 and CXCL2, as well

as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). They additionally

synthesize RANKL, colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1),

high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and IL-11, all of which promote

osteoclastogenesis and the process of bone resorption (12). In OS, osteocytes activate the

CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling axis by producing CXCL12, which is linked to

tumor metastasis. Osteoclasts are integral to the initiation and

metastasis of OS (13). Among the

cytokines involved, CSF-1 and soluble RANKL are crucial for the

differentiation and activation of OBs). CSF-1 is responsible for

the regulation of both the proliferation and survival of

pre-osteoclasts (14). By contrast,

RANKL, which is synthesized by OBs and various other bone cells

(15), interacts with its receptor

RANK located on the surface of osteoclast precursors (16). This interaction regulates the

differentiation and maturation of osteoclast precursors via

paracrine signaling mechanisms. In the context of OS, heightened

osteoclast activity plays a significant role in the proliferation

of OS cells and the degradation of bone tissue. This mechanism

leads to the liberation of pro-tumorigenic factors, such as

insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and from the bone matrix,

thereby promoting tumor proliferation and metastasis (17).

Tumor-associated immune cells

Within the microenvironment of OS, monocytes and

macrophages constitute 70–80% of the total BM cell population

(18). Various cell types,

including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), T cells, B cells,

natural killer (NK) cells and BM MSCs, present in the tumor immune

microenvironment significantly influence tumor development,

invasion and metastasis. Recent investigations into TAMs have

emerged as a focal point of research.

TAMs constitute the most prevalent immune cell

population within the OS microenvironment, and account for >50%

of all infiltrating immune cells, alongside other cell types

including dendritic cells (DCs), lymphocytes and myeloid-derived

cells. Collectively, these cells form the primary components of the

OS immune microenvironment (19).

Research indicates that TAMs are prevalent in most high-grade OS

biopsy specimens, and an increase in TAMs is associated with

reduced metastasis and extended survival (20); however, the underlying mechanisms

remain unclear. Immune cells within the TME can either promote or

inhibit OS, contingent upon the immune environment and the specific

cell types involved (21). For

instance, certain immune cells, including T cells, B cells and NK

cells, can exert antitumor effects, while others, such as

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), M2 macrophages and

regulatory T cells (Tregs), may facilitate tumor growth and

metastasis. Consequently, elucidating the intricate mechanisms of

interaction between OS and immune cells is essential for advancing

research into novel immunotherapies (17).

TAMs

TAMs originate from peripheral monocytes and are

recruited to the tumor site by various chemokines and cytokines,

including C-C motif ligand 2, CSF-1 and VEGF. Upon entering the

tumor, TAMs can exhibit two primary phenotypes: The

pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and the immunosuppressive M2

phenotype. The M1 phenotype is associated with protective responses

and is typically linked to a favorable prognosis in patients with

OS (22). Conversely, the M2

phenotype can be induced by various stimuli within the immune

microenvironment, particularly through cytokines IL-4 and IL-13

that signal via the signal transducer and activator of the

transcription 6 (STAT6) pathway, as well as IL-10 and

glucocorticoids. M2-type TAMs secrete a range of cytokines that

promote the migration and invasion of OS cells while inhibiting the

immune function of T lymphocytes (23). M1 and M2 TAMs can undergo

interconversion under the influence of key cytokines and signaling

pathways, such as the Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) via the STAT6

pathway, as well as IL-10 and TGF-β. This macrophage polarization

is dynamic. Research has demonstrated that polarized M2-type TAMs

play a significant role in the proliferation and metastasis of OS.

For example, M2-type TAMs can facilitate the migration and invasion

of OS cells by triggering an autocrine signaling loop that

activates HMGB1 expression within the tumor cells. Furthermore,

HMGB1 has been shown to encourage the polarization of M1-type TAMs

into M2-type TAMs, thereby establishing a positive feedback

mechanism that exacerbates the development and progression of OS

(24).

T cells

T cells are integral to both cellular and humoral

immunity and comprise a wide array of functionally specialized

subsets, including T helper cells (Th1, Th2, Th9, Th17, Th22 and

follicular helper T cells), cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and

Tregs. This diversity is crucial for orchestrating the antitumor

immune response in OS, with the composition and balance of these

infiltrating T cell subsets determining the immunological outcome.

In OS, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are predominantly located in

areas expressing human leukocyte antigen class I, while

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells primarily aggregate at

the interface between lung metastases and normal tissue (25). Studies have indicated that the

density of T cells in metastatic lesions is significantly greater

than that in primary and recurrent lesions, suggesting that T cells

may also serve as potential prognostic indicators (26,27).

Analysis of biopsy tissues and peripheral blood from patients with

primary OS has revealed that T cell levels in biopsy specimens

exceed those in peripheral blood, suggesting that the immune

microenvironment within tumor lesions is suppressive, potentially

inhibiting T cell immune activity through TAMs, further suggesting

that T cells may serve as an auxiliary biomarker for clinical

diagnosis (28). Furthermore, the

depletion of CD163+ macrophages, a hallmark

immunosuppressive subset in the OS TME, has been shown to enhance T

cell growth and pro-inflammatory factor production in vitro.

Therefore, targeting these cells represents a promising approach to

reprogram the immunosuppressive OS TME and potentiate antitumor

immunity (28). The prognostic

value of T cells is well-established across various cancer types,

with studies confirming that specific T-cell signatures, such as

the CD8 T-cell signature, are robust predictors of patient survival

(29,30). Furthermore, prognostic models based

on T-cell-related genes have been successfully constructed for

cancer types such as hepatocellular carcinoma (29,30).

B cells

B cells can be classified into three categories:

Naive B cells, memory B cells and effector B cells/plasma cells,

with the latter being the primary source of antibodies. Regulatory

B cells, a subset of B cells, exert immunosuppressive effects by

inhibiting CD4+ T cells, CTLs, macrophages and DCs

through the secretion of inhibitory cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β

and IL-35, as well as the expression of membrane surface regulatory

molecules such as FasL and CD1d (31). Regulatory B cells also promote the

conversion of T cells into T lymphocytes, thereby diminishing the

antitumor immune response (32)].

Current research on B cells in OS remains limited; however, a

recent pan-cancer immune-infiltration analysis showed that patients

with high B-cell abundance exhibit a significantly improved overall

survival, and the proportion of activated B cells

(CD19+CD27+) correlates positively with

metastasis-free survival in OS (33). Thus, the presence of effector B

cells may serve as a favorable prognostic indicator. Antibodies

play a crucial role in the regulation of tumor growth and

metastasis through various mechanisms, including antibody-dependent

cell-mediated cytotoxicity, regulatory effects, complement

activation, tumor cell receptor blockade and alterations in tumor

cell adhesion (34,35). Nonetheless, some studies have also

indicated that certain antibodies may bind to antigens on the

surface of tumor cells, thereby obstructing their cytotoxic effects

(32,36).

NK cells

NK cells are a type of innate lymphocyte

characterized by the expression of the intracellular transcription

factor E4 BP 4+ and are identified as CD3−

CD19− CD56+ CD16+. NK cells have

been shown to not only directly eliminate tumor cells but also

regulate tumor progression and metastasis (37,38).

They can induce tumor cell death in the TME by releasing perforin,

granzyme and TNF-α, as well as expressing FasL (39). The programmed cell death protein-1

(PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) axis plays a role in

modulating the antitumor effects of NK cells. Research has

demonstrated that blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 axis with PD-L1

antibodies enhances the cytotoxic activity of NK cells against

human OS cells by inhibiting NK cell toxicity through the secretion

of granzyme B (40). Comprehensive

analyses of immune infiltration in the OS microenvironment have

revealed that male patients exhibit a higher presence of NK cells

compared with female patients (41). Additionally, it has been observed

that NK cells are suppressed in the OS microenvironment, with

increased expression of TGF-β (42). This suppression may involve the

inhibition of the activating receptor natural killer group 2 member

D and a reduction in perforin release by NK cells, thereby

promoting angiogenesis, bone remodeling and cellular migration.

BM MSCs

BM MSCs are classified as multipotent stem cells

that significantly contribute to the development of OS tumors

through the modulation of immune responses and the facilitation of

cell fusion and differentiation (43). MSCs and OBs are regarded as

potential precursors to OS cells (33). Research suggests that MSCs play a

crucial role in mediating the bidirectional crosstalk between OS

tumor cells and the TME through the secretion of a variety of

cytokines, chemokines, ILs and other signaling molecules (44). MSCs are actively involved in the

paracrine signaling mechanisms of OS tumor cells, influencing

multiple facets of tumor behavior, such as angiogenesis,

proliferation, invasion, metastasis, immune modulation and

resistance to chemotherapy (45).

Furthermore, MSCs facilitate the growth, metastasis, and

angiogenesis of OS by releasing an array of chemokines, including

CCL5, stromal-derived factor 1, CXCL12, IL-6 and VEGF (45).

MSC-derived extracellular vesicles have been shown

to enhance the proliferation, invasion and migration of OS cells

via the metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript

1/microRNA (miR)-143/Neurensin-2/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway,

as well as through miR-655-mediated β-catenin signaling (46). Research indicates that TGF-β is

significantly upregulated in patients with OS (47). Furthermore, OS cells enhance the

secretion of extracellular vesicles that contain TGF-β. This

process subsequently stimulates the release of IL-6, which is

activated by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

(STAT3) from MSCs, thereby facilitating lung metastasis (48). Additionally, single-cell RNA

sequencing has uncovered a considerable heterogeneity among MSCs

associated with OS (18).

MSCs facilitate the proliferation and metastasis of

OS cells through two primary non-immune mechanisms. First, the

interaction between OS cells and MSCs is mediated by IL-8 and

aquaporin 1. Second, aberrant gene expression, including

retinoblastoma, c-Myc, TP53, KRas and Indian Hedgehog, contributes

to the transformation of MSCs into OS cells (49). Furthermore, studies have

demonstrated that when MSCs are located within the microenvironment

of OS cells, they have the capacity to differentiate into CAFs

(50,51). This differentiation notably

contributes to the increased proliferation, migration and invasion

of OS cells. Under the influence of MSCs, OS cells are capable of

inducing the migration and invasion of endothelial cells, which in

turn promotes angiogenesis (52).

From an immunological perspective, MSCs secrete anti-inflammatory

factors and inhibit pro-inflammatory substances, thereby assisting

OS cells in evading immune surveillance, particularly through

autocrine or paracrine exosomal mechanisms. Lagerwei et al

(53) demonstrated that MSCs

suppress T cell proliferation and immune responses by releasing

exosomal vesicles (EVs) containing miRNA/RNA and proteins.

Additionally, Zhang et al (54) reported that MSC-derived EVs express

TGF-β and TGF-β1. Moreover, MSC-derived exosomes can enhance OS

tumorigenesis and metastasis through the induction of autophagy, as

supported by evidence from other studies (55,56).

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs)

OS cells are present not only within the tumor

tissue but also in the bloodstream, where they are identified as

CTCs (57). CTCs demonstrate the

capacity to circumvent localized therapeutic approaches, including

surgical resection and radiation therapy, and can remain present in

small numbers during systemic treatments. This persistence

ultimately facilitates the metastasis and recurrence of OS

(57,58). Current research suggests that CTCs

play a unique role within the immune microenvironment associated

with OS. For instance, Zhang et al (59) demonstrated that the inhibition of

IL-6 can suppress the proliferation of OS cells and decrease the

presence of CTCs. In vitro studies revealed that IL-6

activates the Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT3 and mitogen-activated

protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2)

signaling pathways. While both pathways facilitate the

proliferation of OS cells, only the JAK/STAT3 pathway is implicated

in promoting cell migration (59–61). A

clinical study has shown that the level of IL-6 in OS samples is

significantly upregulated compared with normal bone tissue,

indicating that IL-6 plays an important role in the progression of

OS (62). Furthermore, MSCs have

been shown to enhance OS proliferation and metastasis through the

secretion of IL-6 (63,64). Liu et al (65) further identified that IL-8 also

contributes to the progression of OS. Their research involved

isolating and culturing CTCs from patients, revealing that IL-8

promotes tumor growth and lung metastasis in both in vitro

and in vivo models, indicating that targeting IL-8 may yield

antitumor effects. Although the precise mechanisms governing the

interaction between CTCs and tumor immunity remain unclear, CTCs

may represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention and

serve as biomarkers for predicting clinical outcomes.

Exosomes

Exosomes are a key subtype of EVs. EVs are

membrane-bound structures that are released into the ECM following

the fusion of intracellular multivesicular bodies with the cell

membrane. These vesicles encapsulate a diverse array of

biomolecules, including long non-coding RNAs, miRNAs, proteins,

lipids and metabolites. Notably, cancer cells tend to produce a

greater quantity of exosomes compared with normal cells, and these

exosomes are implicated in various aspects of tumor biology,

including tumor initiation, progression, immune evasion and drug

resistance (66). Evidence suggests

that EVs play a critical role in the onset, advancement and

metastasis of OS (15).

Specifically, exosomes can facilitate tumor growth by influencing

endothelial cells to enhance angiogenesis, while also mediating

intercellular interactions and participating in the regulation of

cellular functions and the transmission of biological information,

which in turn affects the expression and secretion of specific

cytokines (67,68). Furthermore, exosomes can modify

signaling pathways in recipient cells, thereby promoting the

metastasis of cancer cells (69).

Concurrently, exosomes can activate multiple signaling pathways

that lead to the development of drug resistance in previously

drug-sensitive cells or assist cancer cells in expelling cytotoxic

agents (70). Research has also

indicated that exosomes play a role in modulating the immune

response, aiding tumor cells in evading immune surveillance and

facilitating cancer metastasis. For instance, exosomes have been

shown to promote lung metastasis in OS by releasing PD-L1 (9). Recent studies have advanced our

understanding of the role of exosomal miRNAs in OS (71,72).

For instance, in the context of OS, it has been demonstrated that

exosomal miRNAs, such as miR-148a-3p, can stimulate the release of

pro-angiogenic factors and induce angiogenesis by influencing the

activity of osteoclasts and endothelial cells (73). Additionally, exosomes can enhance

the invasiveness of OS through immune modulation; the surface of

exosomes is adorned with tumor-associated antigens that interact

with antigen-presenting cells, thereby inducing tumor-specific

cytotoxic T cell immune responses (74). Moreover, it has been observed that

exosomes secreted by metastatic OS cells can induce M2 polarization

via TGF-β2, further promoting tumor invasion and metastasis

(75). In a study, Shimbo et

al (76) encapsulated synthetic

therapeutic miRNA-143 within exosomes and administered it into the

OS microenvironment, resulting in a significant reduction in OS

cell migration. The investigation of exosomes has emerged as a

prominent area of research and ongoing advancements in this field

have the potential to yield novel breakthroughs in the clinical

management of OS.

ECM

The ECM is a complex, mesh-like structure comprised

of collagen, proteoglycans, glycoproteins and glycosaminoglycans,

including hyaluronic acid. This matrix not only supplies essential

nutrients and structural support to tumor cells but also plays a

critical role in the construction and remodeling of the ECM,

thereby influencing the physical and chemical characteristics of

the TME (77). Cytokines and the

ECM serve as pivotal mediators within this microenvironment,

capable of modulating various biological behaviors of tumor cells,

including proliferation, apoptosis, invasion and metastasis

(78). OS is known to produce a

large amount of ECM, which significantly impacts tumor invasiveness

and the response to therapeutic interventions (66). Specific ECM components, such as

collagen, fibronectin and laminin, are implicated in aberrant

signaling pathways and structural irregularities that facilitate

sarcoma growth and metastasis through diverse mechanisms, including

integrin-mediated signaling activation, the promotion of EMT and

the enhancement of cell migration and invasion (79). Furthermore, the ECM has the capacity

to regulate the IGF axis, which is instrumental in modulating OS

growth and conferring resistance to conventional chemotherapy

agents (66). Targeting the ECM in

the treatment of OS presents promising potential; for instance,

ECM-like hydrogels can be utilized for the delivery of therapeutic

agents, thereby offering a novel platform for OS treatment and bone

regeneration (80). Additionally,

ECM-associated factors, such as neurotrophic EGF-like molecule 1,

have emerged as promising candidates for novel therapeutic

strategies aimed at impeding OS progression (20). Evidence suggests that the

invasiveness of OS can be mitigated by targeting the underlying

mechanisms of ECM degradation and angiogenesis (14,81).

Therapeutic strategies include suppressing key enzymes such as

matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs; including MMP-2 and MMP-9) to

prevent ECM breakdown and employing monoclonal antibodies or

small-molecule inhibitors against pro-angiogenic factors such as

VEGF to block new blood vessel formation (14,81).

The interplay between the ECM and CAFs is also known to foster the

development of OS (82). This

cooperative relationship drives disease progression by creating a

stiffened, pro-fibrotic microenvironment that supports tumor cell

survival, proliferation and invasion. The critical nature of this

interplay is evidenced by studies showing that therapeutic

strategies designed to destroy CAFs and disrupt the ECM can

effectively suppress OS tumor growth (82). Moreover, ECM components, including

EVs, hold potential as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis

of OS (83). Engineered AttIL 12-T

cells, which are tumor-specific T cells with IL-12 anchored to

their cell membrane, have demonstrated enhanced efficacy by

targeting CAFs within the ECM, disrupting the tumor stroma and

promoting T cell infiltration, indicating promising avenues for

future research (82). This

engineering approach involves uniformly tethering the IL-12

cytokine onto the surface of the adoptively transferred T cells,

which allows for dose-controlled and localized delivery of IL-12

directly to the tumor site (82).

In conclusion, the significant role of the ECM in OS is

increasingly becoming a focal point for therapeutic strategies.

Vascular microenvironment

Tumor-associated blood vessels constitute a critical

element of the TME. The establishment of a robust vascular network

is critical for the growth and metastasis of tumors, as it provides

essential oxygen and nutrients while also facilitating the spread

of cancer cells. The presence of environmental stressors, such as

hypoxia and acidosis, disrupts the balance between pro-angiogenic

and anti-angiogenic factors, resulting in an increased expression

of pro-angiogenic elements, including hypoxia-inducible factors

(HIF) and VEGF, which together enhance tumor angiogenesis (84). Although the specific mechanisms

governing neovascularization in OS are not yet fully understood, it

is noteworthy that OS typically develops near the epiphyseal

regions of long bones, where H-type endothelial cells known to

promote angiogenesis are abundant (85). This suggests a potential involvement

of these cells in the neovascularization process associated with

OS. VEGF is crucial in modulating the growth, differentiation and

development of new blood vessels within endothelial cells, which in

turn has a notable impact on tumor proliferation and migration

(86). By enhancing tumor

angiogenesis, VEGF guarantees the supply of vital oxygen and

nutrients to tumor cells, thereby supporting the processes of tumor

initiation and progression (86,87).

Notably, VEGF expression, particularly its isoform VEGF-A, is

correlated with advanced tumor stages and metastatic potential

(88). Compared with normal bone

tissue, the expression of its receptor, VEGFR-2, is markedly

elevated in OS, with high levels of VEGFR-2 expression associated

with unfavorable prognostic outcomes (89). Gene amplification of VEGF,

especially VEGF-A, has been documented in patients with OS and

corroborated at the protein level. Empirical research has

established a positive association between increased expression of

VEGF and both tumor stage and the occurrence of metastasis

(90). Consequently, a significant

increase in vascular density may serve as a biomarker

distinguishing primary OS tumors in patients with metastasis from

those with non-metastatic disease. Furthermore, tumor-derived

exosomes facilitate intercellular communication and angiogenesis by

transporting pro-angiogenic factors and angiogenesis-related miRNAs

(91). Tumor vascular endothelial

cells have consistently been recognized as a vital target for

anticancer therapies. Therefore, the application of anti-angiogenic

agents, particularly those directed against VEGF, has the potential

to selectively inhibit neovascularization and enhance

progression-free survival in patients with cancer (92). Bevacizumab, an antibody targeting

VEGF, has demonstrated notable efficacy in clinical settings when

administered in conjunction with chemotherapy agents or immune

checkpoint inhibitors (93,94). Research indicates that the VEGFR-2

tyrosine kinase inhibitor Apatinib can attenuate the activity of

the Y chromosome sex-determining region box transcription factor-2

via the STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby mitigating

doxorubicin-induced chemoresistance in OS (95). However, prolonged anti-angiogenic

treatment may induce tumor hypoxia and promote invasive behavior,

potentially leading to therapeutic resistance (96).

Hypoxia and the TME of OS

The rapid expansion of tumors beyond the oxygen

supply capacity of surrounding blood vessels results in localized

hypoxia, which is characterized by diminished oxygen levels and

elevated lactate concentrations within the TME (97). This hypoxic and acidic milieu

fosters the expression of angiogenic factors, enabling invasive OS

cells to utilize vascular mimicry for the formation of angiogenic

microchannels (98). Hypoxia

triggers a range of cellular mechanisms, primarily governed by the

transcription factor HIF-1α. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α

undergoes rapid degradation; however, in hypoxic environments, it

remains active, facilitating processes such as tumor growth,

invasiveness, angiogenesis, metastasis and resistance to therapy

(99,100). Empirical studies have demonstrated

that in rapidly proliferating tumor tissues, HIF-1 facilitates a

metabolic shift in hypoxic tumor cells from the more efficient

oxidative phosphorylation to the less efficient glycolytic pathway,

thereby sustaining energy production (101). This metabolic adaptation, referred

to as the Warburg effect, leads to an increased production of

lactate, which modifies the TME and promotes the proliferation,

invasion and migration of tumor cells (102).

Research has indicated a direct correlation between

lactate levels in tumors and the incidence of distant metastasis,

suggesting that lactate accumulation may serve as a predictive

biomarker for tumor metastasis and patient survival rates (103). Beyond being a mere metabolic

byproduct, lactate functions as a signaling molecule. Zhang et

al (104) identified

lactylation as a significant epigenetic modification capable of

regulating the transcription of numerous oncogenes and tumor

suppressor genes, thereby revealing a universal mechanism of

metabolic regulation that broadly influences tumor progression.

Additionally, Lee et al (105) discovered a hypoxia-regulated

protein, N-myc downstream regulated gene-3 (NDRG-3), which operates

independently of HIF-1α. In the TME, reduced oxygen availability

and hypoxia-induced glycolysis, which results in lactate

production, can enhance the expression of NDRG-3 protein through

the activation of the Raf/ERK signaling pathway. This process

subsequently facilitates tumor angiogenesis and cellular

proliferation.

Subsequent research has demonstrated that hypoxic

conditions can expedite tumor progression by influencing the immune

response, cytokine production, growth factors and ILs, thereby

promoting tumor immune evasion (106). Specifically, in hypoxic

environments, immune responses are diminished due to a decrease in

the infiltration and functionality of CD8+ T cells, as

well as the impaired maturation and activity of DCs and NK cells.

Additionally, there is an induction of M2 polarization in TAM,

along with an increase in the activity of Tregs and MDSCs (107). Furthermore, lactic acid plays a

role in tumor immune resistance by facilitating M2 polarization,

enhancing the activity of CD8+ T cells and elevating

PD-1 expression in Tregs (108,109).

He et al (110) demonstrated the inhibition of OS

metastasis through the application of nanomaterials designed to

deliver oxidants that degrade β-catenin within the

HIF-1α/Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa interacting protein

3/LC3B-mediated mitochondrial autophagy pathway. Zheng et al

(111) found that hypoxia

significantly influences metabolic reprogramming; their research

indicated that the inhibition of long non-coding RNA DLGAP 1-AS 2

can suppress aerobic glycolysis via the miR-451a/hexokinase 2 axis,

thereby impeding OS progression. In conclusion, the hypoxic

microenvironment in OS is garnering increasing attention for its

pivotal role in orchestrating tumor progression, metastasis, immune

regulation, metabolic alterations and therapeutic responses.

Comprehensive research into its complexities presents promising

opportunities for the development of innovative treatment

strategies for OS.

Translational challenges and future

directions in OS TME research

Despite extensive research regarding TME

heterogeneity, including insights gained from animal models

(112) and findings from in

vitro experiments (113,114), effectively translating these

findings into clinical practice remains challenging. First, studies

have shown that the TME of OS exhibits high heterogeneity, with

significant variations observed across patients, subtypes and even

different regions within the same tumor, rendering a

one-size-fits-all targeted strategy impractical (21,112).

This heterogeneity extends to the dynamic nature of the TME,

demanding therapeutic approaches capable of adapting to evolving

tumor characteristics over time (21). Furthermore, there is a current lack

of preclinical models that accurately mimic the human OS TME

(112). Traditional animal

xenograft models, along with cell line cultures, often fail to

reproduce the full complexity of human-specific cell-cell

interactions and the immune microenvironment, limiting the

translational potential of laboratory discoveries (115,116).

Moreover, therapies targeting the TME may induce

unintended systemic toxicity or immune-related adverse events. This

necessitates particularly cautious evaluation in adolescent and

pediatric patients, as this predominant OS patient population is

especially vulnerable due to their ongoing physical development,

which can affect organ function, drug metabolism and the long-term

impact of treatments on growth and fertility (117). Existing clinical trials primarily

focus on single-target therapies, overlooking the synergistic

effects of multi-signaling networks within the TME, which may limit

therapeutic efficacy. The potential for developing resistance to

targeted therapies poses another significant challenge, as cancer

cells can adapt and find alternative pathways for survival.

Furthermore, the complexity of TME interactions means targeting one

component may have unintended effects on others, potentially

leading to treatment resistance or other adverse reactions

(21). Developing reliable

biomarkers to monitor the TME and predict treatment response

remains an active research area. Identifying these biomarkers is

crucial for achieving more personalized and effective treatment

regimens.

In summary, while the TME presents a promising

target for OS therapy, addressing its heterogeneity, developing

accurate preclinical models, managing potential toxicity and

overcoming resistance mechanisms are key challenges that must be

overcome to successfully translate these insights into clinical

practice. Future efforts must prioritize multi-omics integration

analyses, develop humanized organoids or patient-derived xenograft

models and advance personalized therapeutic strategies targeting

both the TME and tumor cells simultaneously. Only through such a

comprehensive approach can true lab-to-bedside translation be

achieved.

In conclusion, the TME represents a highly intricate

network system characterized by the coexistence and interaction of

various cellular and non-cellular components, which are integral to

the proliferation, invasion and metastasis processes in OS. Within

the TME, diverse cell types, including TAMs, MSCs and

immunosuppressive T cells, contribute to the invasive progression

of OS through the secretion of numerous cytokines and the

activation of associated signaling pathways. Concurrently, the high

metabolic activity, extensive vascular network and hypoxic

conditions of the tumor further intensify its invasiveness and

metastatic capabilities. At present, the treatment of OS has

encountered significant challenges, primarily the limited

improvement in survival outcomes for patients with metastatic or

recurrent disease, the high degree of inter- and intra-tumoral

heterogeneity that complicates targeted therapy and the plateaued

efficacy of conventional chemotherapy regimens (118). Future advancements are anticipated

to involve the application of single-cell sequencing and spatial

transcriptomics to conduct in-depth analyses of TME heterogeneity,

thereby elucidating critical regulatory mechanisms (119,120). Moreover, the development of

targeted therapies and immunotherapeutic strategies that

specifically address the TME is a promising avenue for research

(121,122). Additionally, the integration of

artificial intelligence and multi-omics data analysis is expected

to yield innovative approaches for the personalized treatment of OS

(123). Through interdisciplinary

collaboration, efforts to disrupt the malignant cycle perpetuated

by the TME may offer new therapeutic prospects for patients with

OS.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a project of the Department of

Education of Yunnan Province (grant no. 2025J0346) and an

intramural project of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming

Medical University (grant no. 2022yk05).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

TS, JK and QW designed the study. TS, JK and JS

performed the literature search and analysis. TS and JK wrote the

draft; TS and JS prepared the figure. QW, JS and XH critically

revised the manuscript. XH conceived the intellectual framework.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhao X, Wu Q, Gong X, Liu J and Ma Y:

Osteosarcoma: A review of current and future therapeutic

approaches. Biomed Eng Online. 20:242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Moukengue B, Lallier M, Marchandet L,

Baud'huin M, Verrecchia F, Ory B and Lamoureux F: Origin and

therapies of osteosarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 14:35032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tsagozis P, Gonzalez-Molina J, Georgoudaki

AM, Lehti K, Carlson J, Lundqvist A, Haglund F and Ehnman M:

Sarcoma tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1296:319–348.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wei L and Wang J: Tumor-associated

macrophages promote pre-metastatic niche formation in ovarian

cancer. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 40:1138–1145. 2024.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fang J, Lu Y, Zheng J, Jiang X, Shen H,

Shang X, Lu Y and Fu P: Exploring the crosstalk between endothelial

cells, immune cells, and immune checkpoints in the tumor

microenvironment: new insights and therapeutic implications. Cell

Death Dis. 14:5862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Devaraji M and Varghese Cheriyan B:

Immune-based cancer therapies: Mechanistic insights, clinical

progress, and future directions. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 37:622025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Malone MK, Smrekar K, Park S, Blakely B,

Walter A, Nasta N, Park J, Considine M, Danilova LV, Pandey NB, et

al: Cytokines secreted by stromal cells in TNBC microenvironment as

potential targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 21:560–569.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zeng J, Peng Y, Wang D, Ayesha K and Chen

S: The interaction between osteosarcoma and other cells in the bone

microenvironment: From mechanism to clinical applications. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 11:11230652023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chen F, Liu J, Yang T, Sun J, He X, Fu X,

Qiao S, An J and Yang J: Analysis of intercellular communication in

the osteosarcoma microenvironment based on single cell sequencing

data. J Bone Oncol. 41:1004932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Amarasekara DS, Kim S and Rho J:

Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by cytokine networks. Int

J Mol Sci. 22:28512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen X, Wang Z, Duan N, Zhu G, Schwarz EM

and Xie C: Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect Tissue Res.

59:99–107. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Anloague A and Delgado-Calle J:

Osteocytes: New kids on the block for cancer in bone therapy.

Cancers(Basel). 15:26452023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Behzatoglu K: Osteoclasts in tumor

biology: Metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal-myeloid transition.

Pathol Oncol Res. 27:6094722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang Q, Liu J, Wu B, Wang X, Jiang Y and

Zhu D: Role of extracellular vesicles in osteosarcoma. Int J Med

Sci. 19:1216–1226. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jerez S, Araya H, Hevia D, Irarrázaval CE,

Thaler R, van Wijnen AJ and Galindo M: Extracellular vesicles from

osteosarcoma cell lines contain miRNAs associated with cell

adhesion and apoptosis. Gene. 710:246–257. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Feng X and Teitelbaum SL: Osteoclasts: New

insights. Bone Res. 1:11–26. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang G, Jian A, Zhang Y and Zhang X: A

New signature of sarcoma based on the tumor microenvironment

benefits prognostic prediction. Int J Mol Sci. 24:29612023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhou Y, Yang D, Yang Q, Lv X, Huang W,

Zhou Z, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Yuan T, Ding X, et al: Single-cell RNA

landscape of intratumoral heterogeneity and immunosuppressive

microenvironment in advanced osteosarcoma. Nat Commun. 11:63222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cersosimo F, Lonardi S, Bernardini G,

Telfer B, Mandelli GE, Santucci A, Vermi W and Giurisato E:

Tumor-associated macrophages in osteosarcoma: From mechanisms to

therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 21:52072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Qin Q, Gomez-Salazar M, Tower RJ, Chang L,

Morris CD, McCarthy EF, Ting K, Zhang X and James AW: NELL1

regulates the matrisome to promote osteosarcoma progression. Cancer

Res. 82:2734–2747. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhu T, Han J, Yang L, Cai Z, Sun W, Hua Y

and Xu J: Immune microenvironment in osteosarcoma: Components,

therapeutic strategies and clinical applications. Front Immunol.

13:9075502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xu J, Ding L, Mei J, Hu Y, Kong X, Dai S,

Bu T, Xiao Q and Ding K: Dual roles and therapeutic targeting of

tumor-associated macrophages in tumor microenvironments. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 10:2682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang Q, Liang X, Ren T, Huang Y, Zhang H,

Yu Y, Chen C, Wang W, Niu J, Lou J and Guo W: The role of

tumor-associated macrophages in osteosarcoma

progression-therapeutic implications. Cell Oncol (Dordr).

44:525–539. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hou C, Lu M, Lei Z, Dai S, Chen W, Du S,

Jin Q, Zhou Z and Li H: HMGB1 positive feedback loop between cancer

cells and tumor-associated macrophages promotes osteosarcoma

migration and invasion. Lab Invest. 103:1000542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ligon JA, Choi W, Cojocaru G, Fu W, Hsiue

EH, Oke TF, Siegel N, Fong MH, Ladle B, Pratilas CA, et al:

Pathways of immune exclusion in metastatic osteosarcoma are

associated with inferior patient outcomes. J Immunother Cancer.

9:e0017722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Judge SJ, Darrow MA, Thorpe SW, Gingrich

AA, O'Donnell EF, Bellini AR, Sturgill IR, Vick LV, Dunai C,

Stoffel KM, et al: Analysis of tumor-infiltrating NK and T cells

highlights IL-15 stimulation and TIGIT blockade as a combination

immunotherapy strategy for soft tissue sarcomas. J Immunother

Cancer. 8:e0013552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kleinberger M, Çifçi D, Paiato C, Tomasich

E, Mair MJ, Steindl A, Spiró Z, Carrero ZI, Berchtold L,

Hainfellner J, et al: Density and entropy of immune cells within

the tumor microenvironment of primary tumors and matched brain

metastases. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 13:342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lu X, Liu M, Yang J, Que Y and Zhang X:

Panobinostat enhances NK cell cytotoxicity in soft tissue sarcoma.

Clin Exp Immunol. 209:127–139. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shigehara K, Kawai N, Shirosaki T, Ebihara

Y, Murai A, Takaya A, Tokita S, Sasaki K, Shijubou N, Kubo T, et

al: The size of CD8+ infiltrating T cells is a prognostic marker

for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 15:266382025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen L, Huang H, Huang Z, Chen J, Liu Y,

Wu Y, Li A, Ge J, Fang Z, Xu B, et al: Prognostic values of

tissue-resident CD8+T cells in human hepatocellular

carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol.

21:1242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Noy R and Pollard JW: Tumor-associated

macrophages: From mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 41:49–61. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kinker GS, Vitiello GAF, Ferreira WAS,

Chaves AS, Cordeiro de Lima VC and Medina TDS: B cell orchestration

of anti-tumor immune responses: A matter of cell localization and

communication. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6781272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cao Y, Kong L, Zhai Y, Hou W, Wang J, Liu

Y, Wang C, Zhao W, Ji H and He P: Comprehensive analysis of

TRIM56′s prognostic value and immune infiltration in pan-cancer.

Sci Rep. 15:136732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lo Nigro C, Macagno M, Sangiolo D,

Bertolaccini L, Aglietta M and Merlano MC: NK-mediated

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity in solid tumors:

Biological evidence and clinical perspectives. Ann Transl Med.

7:1052019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Capuano C, Pighi C, Battella S, De

Federicis D, Galandrini R and Palmieri G: Harnessing CD16-mediated

NK cell functions to enhance therapeutic efficacy of

tumor-targeting mAbs. Cancers (Basel). 13:25002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Rodríguez-Nava C, Ortuño-Pineda C,

Illades-Aguiar B, Flores-Alfaro E, Leyva-Vázquez MA, Parra-Rojas I,

Del Moral-Hernández O, Vences-Velázquez A, Cortés-Sarabia K and

Alarcón-Romero LDC: Mechanisms of action and limitations of

monoclonal antibodies and single chain fragment variable (scFv) in

the treatment of cancer. Biomedicines. 11:16102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Khodayari H, Khodayari S, Ebrahimi E,

Hadjilooei F, Vesovic M, Mahmoodzadeh H, Saric T, Stücker W, Van

Gool S, Hescheler J and Nayernia K: Stem cells-derived natural

killer cells for cancer immunotherapy: Current protocols,

feasibility, and benefits of ex vivo generated natural killer cells

in treatment of advanced solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

70:3369–3395. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shin E, Bak SH, Park T, Kim JW, Yoon SR,

Jung H and Noh JY: Understanding NK cell biology for harnessing NK

cell therapies: Targeting cancer and beyond. Front Immunol.

14:11929072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Prager I and Watzl C: Mechanisms of

natural killer cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity. J Leukoc Biol.

105:1319–29. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang ML, Chen L, Li YJ and Kong DL:

PD-L1/PD-1 axis serves an important role in natural killer

cell-induced cytotoxicity in osteosarcoma. Oncol Rep. 42:2049–2056.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yang H, Zhao L, Zhang Y and Li FF: A

comprehensive analysis of immune infiltration in the tumor

microenvironment of osteosarcoma. Cancer Med. 10:5696–5711. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lazarova M and Steinle A: Impairment of

NKG2D-mediated tumor immunity by TGF-β. Front Immunol. 10:26892019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chang X, Ma Z, Zhu G, Lu Y and Yang J: New

perspective into mesenchymal stem cells: Molecular mechanisms

regulating osteosarcoma. J Bone Oncol. 29:1003722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Antoon R, Overdevest N, Saleh AH and

Keating A: Mesenchymal stromal cells as cancer promoters. Oncogene.

43:3545–3555. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zheng Y, Wang G, Chen R, Hua Y and Cai Z:

Mesenchymal stem cells in the osteosarcoma microenvironment: Their

biological properties, influence on tumor growth, and therapeutic

implications. Stem Cell Res Ther. 9:222018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhu G, Xia Y, Zhao Z, Li A, Li H and Xiao

T: LncRNA XIST from the bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell derived

exosome promotes osteosarcoma growth and metastasis through

miR-655/ACLY signal. Cancer Cell Int. 22:3302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen C, Xie L, Ren T, Huang Y, Xu J and

Guo W: Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma: Fundamental mechanism,

rationale, and recent breakthroughs. Cancer Lett. 500:1–10. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tu B, Du L, Fan QM, Tang Z and Tang TT:

STAT3 activation by IL-6 from mesenchymal stem cells promotes the

proliferation and metastasis of osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett.

325:80–88. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Deng Q, Li P, Che M, Liu J, Biswas S, Ma

G, He L, Wei Z, Zhang Z, Yang Y, et al: Activation of hedgehog

signaling in mesenchymal stem cells induces cartilage and bone

tumor formation via Wnt/β-catenin. Elife. 8:e502082019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Feng L, Chen Y and Jin W: Research

progress on cancer-associated fibroblasts in osteosarcoma. Oncol

Res. 33:1091–1103. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Duan W, Niu X, Liu Y and Tian W:

Rab27b-mediated CAFs derived exosomal miR-22-3p suppresses

ferroptosis and promotes cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma. Cell

Signal. Sep 17–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Lin L, Huang K, Guo W, Zhou C, Wang G and

Zhao Q: Conditioned medium of the osteosarcoma cell line U2OS

induces hBMSCs to exhibit characteristics of carcinoma-associated

fibroblasts via activation of IL-6/STAT3 signalling. J Biochem.

168:265–271. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lagerweij T, Pérez-Lanzón M and Baglio SR:

A preclinical mouse model of osteosarcoma to define the

extracellular vesicle-mediated communication between tumor and

mesenchymal stem cells. J Vis Exp. 569322018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang Q, Fu L, Liang Y, Guo Z, Wang L, Ma

C and Wang H: Exosomes originating from MSCs stimulated with TGF-β

and IFN-γ promote Treg differentiation. J Cell Physiol.

233:6832–6840. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ruksha T and Palkina N: Role of exosomes

in transforming growth factor-β-mediated cancer cell plasticity and

drug resistance. Explor Target Antitumor Thery. 6:10023222025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Su Z, Fang X and Duan H: The paradoxical

role of stem cells in osteosarcoma: From pathogenesis to

therapeutic breakthroughs. Front Oncol. 15:16434912025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yang C, Liu C, Xia C and Fu L: Clinical

applications of circulating tumor cells in metastasis and therapy.

J Hematol Oncol. 18:802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Fu Y, Xu Y, Liu W, Zhang J, Wang F, Jian

Q, Huang G, Zou C, Xie X, Kim AH, et al: Tumor-informed deep

sequencing of ctDNA detects minimal residual disease and predicts

relapse in osteosarcoma. EClinicalMedicine. 73:1026972024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhang Y, Ma Q, Liu T, Guan G, Zhang K,

Chen J, Jia N, Yan S, Chen G, Liu S, et al: Interleukin-6

suppression reduces tumour self-seeding by circulating tumour cells

in a human osteosarcoma nude mouse model. Oncotarget. 7:446–458.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Tian H, Cao J, Li B, Nice EC, Mao H, Zhang

Y and Huang C: Managing the immune microenvironment of

osteosarcoma: The outlook for osteosarcoma treatment. Bone Res.

11:112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Thuya WL, Cao Y, Ho PC, Wong AL, Wang L,

Zhou J, Nicot C and Goh BC: Insights into IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling

in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer therapy.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 85:26–42. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Dou B, Chen T, Chu Q, Zhang G and Meng Z:

The roles of metastasis-related proteins in the development of

giant cell tumor of bone, osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma. Technol

Health Care. 29:91–101. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Paino F, La Noce M, Di Nucci D, Nicoletti

GF, Salzillo R, De Rosa A, Ferraro GA, Papaccio G, Desiderio V and

Tirino V: Human adipose stem cell differentiation is highly

affected by cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo: Implication for

autologous fat grafting. Cell Death Dis. 8:e25682017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Perrot P, Rousseau J, Bouffaut AL, Rédini

F, Cassagnau E, Deschaseaux F, Heymann MF, Heymann D, Duteille F,

Trichet V and Gouin F: Safety concern between autologous fat graft,

mesenchymal stem cell and osteosarcoma recurrence. PLoS One.

5:e109992010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu T, Ma Q, Zhang Y, Wang X, Xu K, Yan K,

Dong W, Fan Q, Zhang Y and Qiu X: Self-seeding circulating tumor

cells promote the proliferation and metastasis of human

osteosarcoma by upregulating interleukin-8. Cell Death Dis.

10:5752019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Tzanakakis GN, Giatagana EM, Berdiaki A,

Spyridaki I, Hida K, Neagu M, Tsatsakis AM and Nikitovic D: The

role of IGF/IGF-IR-signaling and extracellular matrix effectors in

bone sarcoma pathogenesis. Cancers (Basel). 13:24782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Duan SL, Fu WJ, Jiang YK, Peng LS, Ousmane

D, Zhang ZJ and Wang JP: Emerging role of exosome-derived

non-coding RNAs in tumor-associated angiogenesis of tumor

microenvironment. Front Mol Biosci. 10:12201932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Li Y, Jiang D, Zhang ZX, Zhang JJ, He HY,

Liu JL, Wang T, Yang XX, Liu BD, Yang LL, et al: Colorectal cancer

cell-secreted exosomal miRNA N-72 promotes tumor angiogenesis by

targeting CLDN18. Am J Cancer Res. 13:3482–3499. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ning XY, Ma JH, He W and Ma JT: Role of

exosomes in metastasis and therapeutic resistance in esophageal

cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 29:5699–5715. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Pan W, Miao Q, Yin W, Li X, Ye W, Zhang D,

Deng L, Zhang J and Chen M: The role and clinical applications of

exosomes in cancer drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist.

7:432024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Tian W, Niu X, Feng F, Wang X, Wang J, Yao

W and Zhang P: The promising roles of exosomal microRNAs in

osteosarcoma: A new insight into the clinical therapy. Biomed

Pharmacother. 163:1147712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Chen CC and Benavente CA: Exploring the

impact of exosomal cargos on osteosarcoma progression: Insights

into therapeutic potential. Int J Mol Sci. 25:5682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Li X, Rong K, Huang Y, Zhao Z, Xu C, Lin

L, Zhang Y, Yan Y, Huang W, Zhang Y, et al: Suppression of

miR-148a-3p can promote bone healing by enhancing

angiogenesis-osteogenesis coupling through the PI3K/Akt pathway.

FASEB J. 39:e709302025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Pu F, Chen F, Zhang Z, Liu J and Shao Z:

Information transfer and biological significance of neoplastic

exosomes in the tumor microenvironment of osteosarcoma. Onco

Targets Ther. 13:8931–8940. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wolf-Dennen K, Gordon N and Kleinerman ES:

Exosomal communication by metastatic osteosarcoma cells modulates

alveolar macrophages to an M2 tumor-promoting phenotype and

inhibits tumoricidal functions. Oncoimmunology. 9:17476772020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Shimbo K, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Kato Y,

Kubo T, Shimose S and Ochi M: Exosome-formed synthetic microRNA-143

is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and inhibits their migration.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 445:381–387. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Hu Q, Zhu Y, Mei J, Liu Y and Zhou G:

Extracellular matrix dynamics in tumor immunoregulation: From tumor

microenvironment to immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 18:652025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Pattabiram S, Gangadaran P, Dhayalan S,

Chatterjee G, Reyaz D, Prakash K, Arun R, Rajendran RL, Ahn BC and

Aruljothi KN: Decoding the tumor microenvironment: Insights and new

targets from single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics.

Curr Issues Mol Biol. 47:7302025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Cui J, Dean D, Hornicek FJ, Chen Z and

Duan Z: The role of extracelluar matrix in osteosarcoma progression

and metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:1782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Tian H, Wu R, Feng N, Zhang J and Zuo J:

Recent advances in hydrogels-based osteosarcoma therapy. Front

Bioeng Biotechnol. 10:10426252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Yu Y, Li K, Peng Y, Zhang Z, Pu F, Shao Z

and Wu W: Tumor microenvironment in osteosarcoma: From cellular

mechanism to clinical therapy. Genes Dis. 12:1015692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Hu J, Lazar AJ, Ingram D, Wang WL, Zhang

W, Jia Z, Ragoonanan D, Wang J, Xia X, Mahadeo K, et al: Cell

membrane-anchored and tumor-targeted IL-12 T-cell therapy destroys

cancer-associated fibroblasts and disrupts extracellular matrix in

heterogenous osteosarcoma xenograft models. J Immunother Cancer.

12:e0069912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Loi G, Stucchi G, Scocozza F, Cansolino L,

Cadamuro F, Delgrosso E, Riva F, Ferrari C, Russo L and Conti M:

Characterization of a bioink combining extracellular matrix-like

hydrogel with osteosarcoma cells: Preliminary results. Gels.

9:1292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Fan J, Xie Y, Liu D, Cui R, Zhang W, Shen

M and Cao L: Crosstalk between H-type vascular endothelial cells

and macrophages: A potential regulator of bone homeostasis. J

Inflamm Res. 18:2743–2765. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lee C, Kim MJ, Kumar A, Lee HW, Yang Y and

Kim Y: Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in health and

disease: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic perspectives.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 10:1702025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Shah FH, Nam YS, Bang JY, Hwang IS, Kim

DH, Ki M and Lee HW: Targeting vascular endothelial growth

receptor-2 (VEGFR-2): Structural biology, functional insights, and

therapeutic resistance. Arch Pharm Res. 48:404–425. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Corre I, Verrecchia F, Crenn V, Redini F

and Trichet V: The osteosarcoma microenvironment: A complex but

targetable ecosystem. Cells. 9:9762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Liu K, Ren T, Huang Y, Sun K, Bao X, Wang

S, Zheng B and Guo W: Apatinib promotes autophagy and apoptosis

through VEGFR2/STAT3/BCL-2 signaling in osteosarcoma. Cell Death

Dis. 8:e30152017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Lammli J, Fan M, Rosenthal HG, Patni M,

Rinehart E, Vergara G, Ablah E, Wooley PH, Lucas G and Yang SY:

Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor correlates with

the advance of clinical osteosarcoma. Int Orthop. 36:2307–2313.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Li Y, Lin S, Xie X, Zhu H, Fan T and Wang

S: Highly enriched exosomal lncRNA OIP5-AS1 regulates osteosarcoma

tumor angiogenesis and autophagy through miR-153 and ATG5. Am J

Transl Res. 13:4211–4223. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Assi T, Watson S, Samra B, Rassy E, Le

Cesne A, Italiano A and Mir O: Targeting the VEGF pathway in

osteosarcoma. Cells. 10:12402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Wang C, Duan L, Zhao Y, Wang Y and Li Y:

Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab combined with temozolomide in

the treatment of glioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

clinical trials. World Neurosurg. 193:447–460. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Han X, Qin S, Liu S and Li Z:

Intracavitary perfusion with bevacizumab plus cisplatin versus

cisplatin alone for malignant pleural effusion in lung cancer

patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J

Surg Oncol. 23:2782025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Lowery CD, Blosser W, Dowless M, Renschler

M, Perez LV, Stephens J, Pytowski B, Wasserstrom H, Stancato LF and

Falcon B: Anti-VEGFR2 therapy delays growth of preclinical

pediatric tumor models and enhances anti-tumor activity of

chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 10:5523–5533. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Haibe Y, Kreidieh M, El Hajj H, Khalifeh

I, Mukherji D, Temraz S and Shamseddine A: Resistance mechanisms to

anti-angiogenic therapies in cancer. Front Oncol. 10:2212020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Zhou J, Lan F, Liu M, Wang F, Ning X, Yang

H and Sun H: Hypoxia inducible factor-1α as a potential therapeutic

target for osteosarcoma metastasis. Front Pharmacol.

15:13501872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Ren K, Zhang J, Gu X, Wu S, Shi X, Ni Y,

Chen Y, Lu J, Gao Z, Wang C and Yao N: Migration-inducing gene-7

independently predicts poor prognosis of human osteosarcoma and is

associated with vasculogenic mimicry. Exp Cell Res. 369:80–89.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Zhang QJ, Liu CH, Wang K, Mao XY, Dong Y,

Zang MY, Zhang W, Yu QS and Hao L: Hypoxia-induced HIF-1α/VASN

promotes bladder cancer progression. Sci Rep. 15:216352025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zeng X, Liu S, Yang H, Jia M, Liu W and

Zhu W: Synergistic anti-tumour activity of ginsenoside Rg3 and

doxorubicin on proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis in

osteosarcoma by modulating mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF and EMT signalling

pathways. J Pharm Pharmacol. 75:1405–1417. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Vander Heiden MG and DeBerardinis RJ:

Understanding the intersections between metabolism and cancer

biology. Cell. 168:657–669. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Huang Y, Fan H and Ti H: Tumor

microenvironment reprogramming by nanomedicine to enhance the

effect of tumor immunotherapy. Asian J Pharm Sci.

19:1009022024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Zhu L, Lin Z, Wang K, Gu J, Chen X, Chen

R, Wang L and Cheng X: A lactate metabolism-related signature

predicting patient prognosis and immune microenvironment in ovarian

cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15:13724132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Lee DC, Sohn HA, Park ZY, Oh S, Kang YK,

Lee KM, Kang M, Jang YJ, Yang SJ, Hong YK, et al: A lactate-induced

response to hypoxia. Cell. 161:595–609. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Wu Q, You L, Nepovimova E, Heger Z, Wu W,

Kuca K and Adam V: Hypoxia-inducible factors: Master regulators of

hypoxic tumor immune escape. J Hematol Oncol. 15:772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Mortezaee K and Majidpoor J: The impact of

hypoxia on immune state in cancer. Life Sci. 286:1200572021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Feng Q, Liu Z, Yu X, Huang T, Chen J, Wang

J, Wilhelm J, Li S, Song J, Li W, et al: Lactate increases stemness

of CD8 + T cells to augment anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun.

13:49812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K,

Tanegashima T, Lin YT, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Irie T, Okumura G, Kono

H, et al: Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T

cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell.

40:201–218.e9. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

He G, Nie JJ, Liu X, Ding Z, Luo P, Liu Y,

Zhang BW, Wang R, Liu X, Hai Y and Chen DF: Zinc oxide

nanoparticles inhibit osteosarcoma metastasis by downregulating

β-catenin via HIF-1α/BNIP3/LC3B-mediated mitophagy pathway. Bioact

Mater. 19:690–702. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Zheng C, Li R, Zheng S, Fang H, Xu M and

Zhong L: The knockdown of lncRNA DLGAP1-AS2 suppresses osteosarcoma

progression by inhibiting aerobic glycolysis via the miR-451a/HK2

axis. Cancer Sci. 114:4747–4762. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Wang Z, Ma L, Xu J and Jiang C: Editorial:

Genetic and cellular heterogeneity in tumors. Front Cell Dev Biol.

12:15195392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Oh JM, Park Y, Lee J and Shen K:

Microfabricated organ-specific models of tumor microenvironments.

Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 27:307–333. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Yu Z, Gan Z, Wu W, Sun X, Cheng X, Chen C,

Cao B, Sun Z and Tian J: Photothermal-triggered extracellular

matrix clearance and dendritic cell maturation for enhanced

osteosarcoma immunotherapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces.

16:67225–67234. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Rodrigues J, Sarmento B and Pereira CL:

Osteosarcoma tumor microenvironment: The key for the successful

development of biologically relevant 3D in vitro models. In Vitro

Model. 1:5–27. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Liu X, Fang J, Huang S, Wu X, Xie X, Wang

J, Liu F, Zhang M, Peng Z and Hu N: Tumor-on-a-chip: From

bioinspired design to biomedical application. Microsyst Nanoeng.

7:502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Spalato M and Italiano A: The safety of

current pharmacotherapeutic strategies for osteosarcoma. Expert

Opin Drug Saf. 20:427–438. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Lu J, Tang H, Chen L, Huang N, Hu G, Li C,

Luo K, Li F, Liu S, Liao S, et al: Association of survivin positive

circulating tumor cell levels with immune escape and prognosis of

osteosarcoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:13741–13751. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Nasir I, McGuinness C, Poh AR, Ernst M,

Darcy PK and Britt KL: Tumor macrophage functional heterogeneity

can inform the development of novel cancer therapies. Trends

Immunol. 44:971–985. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Sharma A, Raut SS, Shukla A, Gupta S,

Mishra A and Singh A: From tissue architecture to clinical

insights: Spatial transcriptomics in solid tumor studies. Semin

Oncol. 52:1523892025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Alnaqbi H, Becker LM, Mousa M, Alshamsi F,

Azzam SK, Emini Veseli B, Hymel LA, Alhosani K, Alhusain M, Mazzone