Introduction

Lung cancer, a type of cancer with the highest

incidence rate worldwide (accounting for 12.4% of all types of

cancer), is the leading cause of cancer-associated mortality

(accounting for 18.7% of all types of cancer) worldwide (1). With the increasing popularity of

low-dose computed tomography in lung cancer screening, the

detection rate of lung cancer has increased substantially (2). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a

major type of lung cancer that accounts for ~85% of lung cancer

cases, and >40% of patients diagnosed with NSCLC have

unresecTable disease that requires chemotherapy (3,4).

Platinum-based systemic chemotherapy is the cornerstone of adjuvant

or neoadjuvant therapy for patients with NSCLC (5). It is also an essential component of

comprehensive treatment for patients with locally advanced tumors.

Moreover, with advancements in immunotherapy, the combination of

platinum-based chemotherapy and immunotherapy can markedly increase

patient survival rates; thus, platinum-based chemotherapy will

continue to serve as the core therapeutic option in the future

(6–9).

A previous study has focused on enhancing the

efficacy of chemotherapy have suggested that factors such as

chemotherapeutic agents, regimens, cycles, drug species and

platinum drugs do not affect the long-term prognosis of patients

(10). However, multicenter

clinical-controlled studies focusing on the adverse effects (AEs)

of chemotherapy have not been performed. Although preventing

chemotherapy resistance in patients is clinically important,

mitigating AEs is equally important for safeguarding patient

efficacy and benefits; thus, more studies should explore AE

mitigation. Chemotherapy-associated AEs or side effects of

chemotherapy refer to the subjective discomfort and harmful and

undesired reactions observed in various body organ systems that

occur during the treatment or recovery period of patients with

cancer receiving normal doses of chemotherapeutic agents. Adverse

drug reactions occur in more than half of patients receiving

systemic anticancer treatments such as chemotherapy, and ~20% of

patients with cancer are readmitted to the hospital because of AEs

(11). Owing to the unpredicTable

occurrence timing and the delayed nature of chemotherapy-associated

AEs, clinicians can be passive in managing these severe side

effects, which affects systemic chemotherapy cycles, and patients

are likely to be affected by the interruption of chemotherapy,

ultimately affecting treatment efficacy. Therefore, predicting AEs

as early as possible will greatly contribute to overcoming the

aforementioned clinical problems.

Several existing studies have predicted adverse drug

reactions on the basis of genomics or drug databases; nevertheless,

these predictions have not been translated into clinical

applications (12–14). Real-world data can accurately

reflect the current state of cancer clinics and aid in addressing

clinical problems (15). With the

commissioning of electronic health record (EHR) systems and the

development of deep learning technology, predicting specific AEs is

possible (16,17). Moreover, deep learning models can be

used to accurately assess disease prognosis in numerous fields,

assisting clinicians in predicting AEs to intervene in advance

(18–20). To predict drug side effects,

numerous scholars have integrated various drug databases, drug

structural properties and protein-binding features, combined with

tumor- or drug-related human gene expression profiles and other

information, to train machine learning (ML) models, and their

performance has comprehensively surpassed that of traditional

methods (12–14,21).

In the present study, real-world data on

hematological indicators, chemotherapy-associated AEs and

interventions in patients with lung cancer before and after each

chemotherapy cycle was extracted from EHRs used and ML models were

used to develop predictive models for identifying common

chemotherapy-associated AEs. Finally, the performance of the

developed ML models was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Patients

The information of lung cancer patients admitted to

the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of

Medicine (Hangzhou, China) who received 2–4 cycles (3 weeks per

cycle) of adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy between January 2016

and February 2020 was extracted from a single-center EHR system in

December 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) A clear

pathological diagnosis of NSCLC; ii) a detailed medical history;

iii) regular chemotherapy cycles; iv) detailed hematological

indicators; and v) detailed records of interventions in patients

with NSCLC with AEs. A total of 403 patients were ultimately

included, totaling 2,062 admissions. The patient cohorts consisted

of 310 men and 93 women with a median age of 62 years (age range,

32–78 years). The final cohort comprised 1,659 single chemotherapy

cycles, of which 1,224 experienced grade ≥1 adverse events [Common

Terminology Criteria for AEs (CTCAE version 5.0)]. And 45

characteristics potentially associated with chemotherapy-associated

AEs were incorporated into the model. This yielded

events-per-variable (EPV)=1,224/45=27.2, markedly above the

traditional logistic-regression threshold of EPV and within the

recommended range of EPV for moderate-complexity algorithms such as

random forest (RF). The present study integrated multi-level data

(2,062 patient characteristic records +1,659 chemotherapy session

records). The use of longitudinal data analysis methods enhanced

statistical power, with this intensive measurement design partially

compensating for patient number limitations.

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

(RECIST; version 1.1) were used to evaluate the clinical efficacy

of chemotherapy. Follow-up was performed to evaluate AEs before

each cycle of chemotherapy. The survival of patients who completed

neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent surgery was followed up for

3 years by telephone and clinical re-examination, follow-up was

performed every 3 months. All procedures in the present

retrospective study involving human participants were performed in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

The patients were informed that the clinical information was stored

by the hospital and potentially used for scientific research, and

the need to obtain signed informed consent was waived by the Ethics

Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine,

Zhejiang University, (Hangzhou, China). All patient cohorts

included in the present retrospective study underwent standardized

testing and treatment protocols. The relevant features and adverse

reaction data were uniformly recorded in the EHR system. For the

very few instances where data were incomplete, a complete-case

analysis was performed and these patients were excluded from the

study to maintain the integrity and robustness of the dataset.

Features

ML algorithms were used to predict AEs in real-world

patients with NSCLC who were receiving chemotherapy. The primary

task for the algorithms was to predict the probability of the next

severe AEs based on data from the present or previous chemotherapy

characterization. The targeted AEs predicted in the present study

were myelosuppression, low albumin (ALB) and hepatic impairment,

with the judgment criteria based on the CTCAE (v5.0), published by

the U.S. Department of Health and Human services.

The following chemotherapy-associated AE

characteristics were extracted as potential predictors for risk

prediction: i) Patient baseline characteristics [age, sex, history

of hypertension, diabetes and tumor history, family tumor history,

smoking status, drinking status, weight loss and body mass index

(BMI)]; ii) tumor-related features (tumor location, tumor size,

histology, grade and stage after surgery); iii)

chemotherapy-related features (first-line treatment,

chemotherapeutic agents and dose); iv) hematological indicators

[white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes,

hemoglobin (Hb), platelet (PLT), total protein (ToP), ALB, alanine

aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine,

uric acid, triglyceride and cholesterol]; and v) clinical

intervention characteristics (recombinant-human granulocyte colony

stimulating factor, thymosin and reduced glutathione).

Identification of significant

features

The original dataset included 45 features generated

during hospitalization. A forward stepwise regression approach was

employed based on logistic regression (LR) for feature selection.

Specifically, at the beginning, univariate analysis was performed

for each feature, and feature A with the best predictive

performance for the outcome was selected and incorporated into the

model. Multivariate analysis involving two features was

subsequently performed on the basis of feature A and each of the

remaining features, and feature B, included in the combination with

the best predictive performance, was selected and added to the

model. This process was repeated step by step to incorporate

predictive factors until the model performance converged, at which

point the addition of factors was stopped, resulting in a set of

features beneficial for predicting AEs. The Shapley Additive

Explanation (SHAP) methodology was used to evaluate the

interpretability of the prediction models. Feature ranking was

achieved through the calculation of SHAP values, with features

being prioritized based on the mean absolute SHAP value for each.

The integration of machine learning techniques with SHAP offers a

clear and explicit interpretation of efficacy predictions.

Statistical algorithms

ML is a general term for a class of methods that

includes multiple algorithms with different technical principles,

each of which may have different performance on a particular task.

To select the optimal model, representative models of common ML

algorithms were used, namely, RF, multilayer perceptron (MLP) and

AdaBoost. For comparison, LR was also used, which is commonly used

in clinical medical research, as a benchmark for performance

comparison. The experiment was performed with five-fold

cross-validation, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curve, area under the ROC curve (AUC) value and calibration curve

were used to evaluate the performance of the model.

RF

An RF model is an integrated learning model that

comprises a number of independent decision trees (also referred to

as weak classifiers), each of which is trained on separate training

data; thus, each tree independently predicts the type of a new

sample. RF subsequently counts the results on the basis of the

predictions of each decision tree and ultimately determines the

specific type of a new sample and its corresponding probability on

the basis of the majority vote classification and mean. The

inclusion of numerous decision trees is the reason for the word

‘forest’ in the name. To avoid the lack of variability in the

trained decision trees due to the inclusion of the same training

data, RF uses a randomized strategy for selecting the training

data. Specifically, for an ‘N’ number of samples of the original

data, the model uses put-back sampling to randomly sample a set of

‘N’ from the original data to train a decision tree. The put-back

sampling strategy ensures that the generated sample will cover ~63%

of the original data; thus, the training data of each decision tree

differ, and there is no significant homogeneity among the resulting

decision trees.

MLP

An MLP is a type of basic neural network that can be

divided into input, hidden and output layers according to its

structure. The layers can be interconnected or not connected. After

data are input into an MLP through the input layer, each node in

the input layer inputs feature values in the data to the nodes in

the next layer with specific weights. The input strength of the

corresponding nodes in the next layer is the cumulative sum of the

output nodes in the previous layer, which is then processed by a

non-linear transformation function to continue to transfer

information to the next layer. These steps are repeated until the

prediction result is finally output at the output layer.

AdaBoost

AdaBoost is an ensemble learning model, similar to

an RF, that also uses numerous decision trees to complete

classification tasks. The decision trees used by AdaBoost are not

independent but are interrelated. Specifically, after the model has

trained the first decision tree, the second decision tree focuses

on the samples misclassified by the first decision tree, thus

ensuring classification accuracy. The third decision tree focuses

on samples misclassified by the former two decision trees. In the

testing phase, after new samples are accepted, AdaBoost runs all

the decision trees simultaneously and then calculates the average

of their outputs with specific weights to obtain the final

prediction results.

Building and environment

All the models used in the present study were

provided by sklearn (22), and

relevant statistical analysis was performed through SciPy (23). The specific experimental environment

was conducted on a Lenovo computer (Lenovo) including an Intel Xeon

E2520 (Mountain View; Intel Corporation), 32 GB of memory and two

Nvidia Titan V graphics cards (NVIDIA Corporation). All original

code has been deposited at GitHub (github.com/ZJU-BMI/cancer). Data

are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with

written permission; following the requirements of data supervision

regulations, these data were not uploaded to a public platform.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of categorical data between

chemotherapy-related AEs in patients and clinical response to

chemotherapy were performed using χ2 or Fisher's exact

test. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method

and analyzed using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was

performed using Prism 10.3 (GraphPad; Dotmatics) and SPSS software

25.0 (IBM Corp.), and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Impact of multi-AEs on patients with

NSCLC receiving chemotherapy

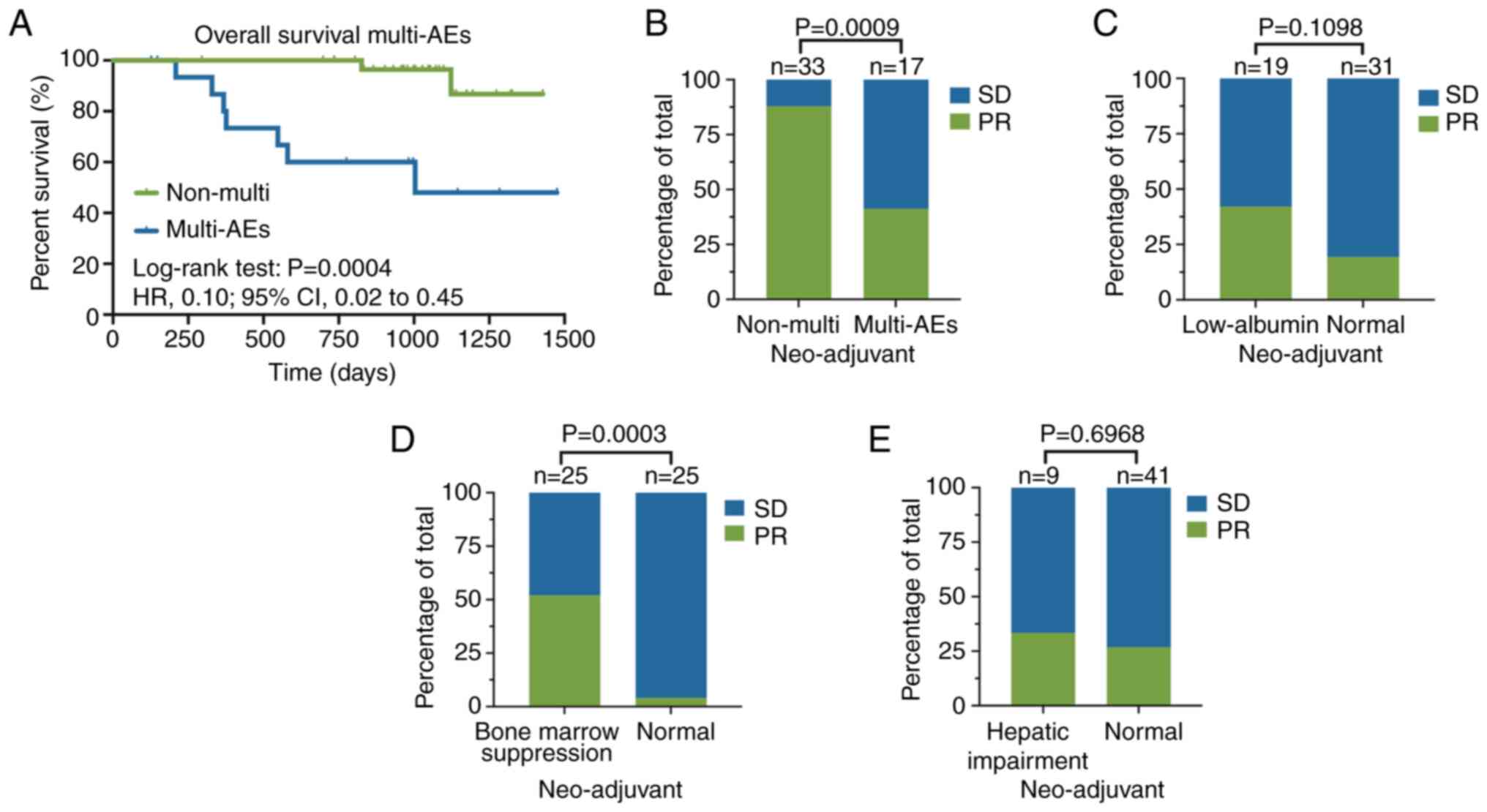

A total of 50 patients with NSCLC who completed

neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent surgery were analyzed. CTCAE

v5.0 was used to determine the extent of AEs in neoadjuvant

patients. All the AEs were found to be grade 1 or 2. Our previous

study revealed that clinical responses according to RECIST v1.1

could predict survival outcomes and an improved objective response

was notably associated with improved overall survival (OS)

(24). Patients who did not

experience multi-AEs (two or more adverse events) had improved OS

compared with those who experienced multi-AEs throughout the

chemotherapy period (hazard ratio, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.45;

Fig. 1A). Furthermore, multi-AEs

were significantly associated with the efficacy of neoadjuvant

chemotherapy (Fig. 1B). However,

there was no significant association between the single AEs,

including low ALB levels and hepatic impairment, and the objective

response (Fig. 1C and E; Table SI).

Evaluation of the predictive

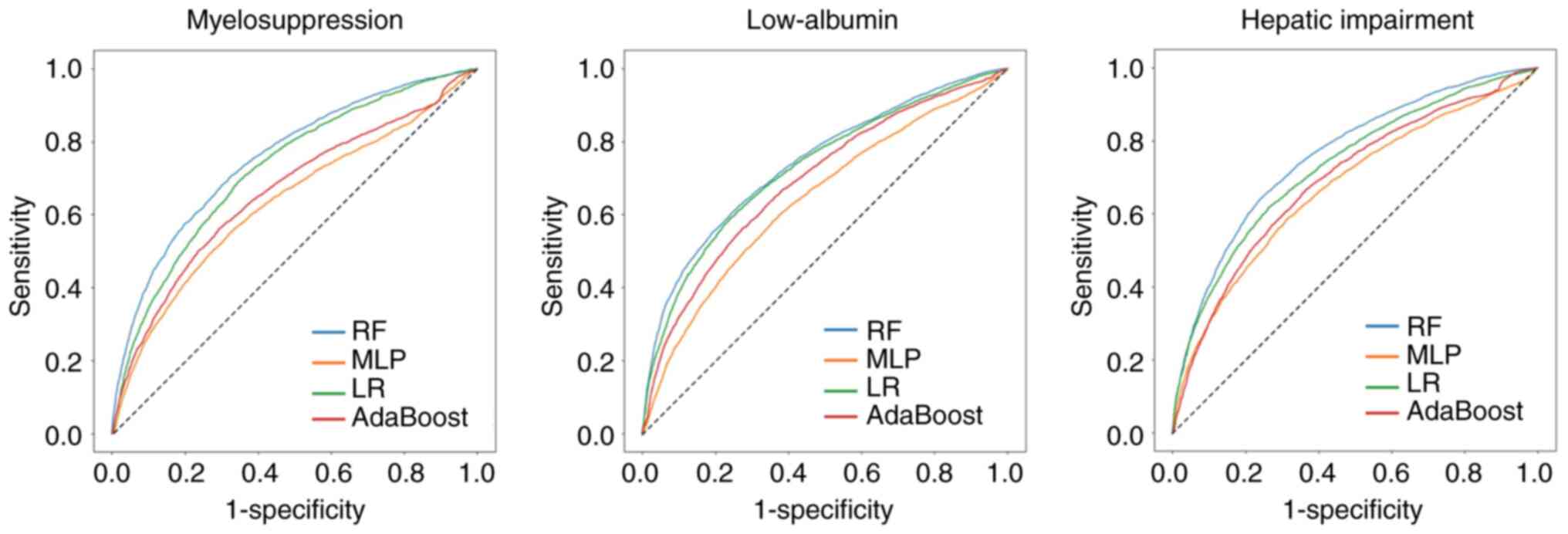

performance of the models

The characteristics of the single chemotherapy

treatments in the dataset are shown in Table I, and the baseline characteristics

of the patients in the experimental dataset are shown in Table II. A total of four independent

prediction models were developed and the performance of all models

were evaluated and compared using ROC curves and AUCs. Among the

proposed models, the RF model exhibited the best performance in

both AE prediction tasks, followed by the LR model, and AdaBoost

outperformed the MLP (Table III).

When comparing the AUC, accuracy and precision between RF and the

other three models, RF outperformed other models. The ROC curves

exhibited a similar trend (Fig. 2),

and the ROC curves of the RF model were consistently higher

compared with those of the other three models for all three

prediction tasks, implying that at any cutoff point, the RF model

demonstrated improved results in terms of the true-positive rate

and false-positive rate simultaneously. With respect to specific

classification performance metrics, the accuracy, precision and

recall rates of the RF model were consistently higher compared with

those of the LR model.

| Table I.Characteristics of single

chemotherapy treatment in data set. |

Table I.

Characteristics of single

chemotherapy treatment in data set.

|

Characteristics | No. of single

treatments (n=1,659) |

|---|

| First-line

treatment, n (mean dose, mg) |

|

| doc/cis

(DP) | 420 (114/41) |

| doc/lob

(DL) | 89 (116/16) |

| doc/oxa

(DOCOX) | 83 (99/64) |

| eto/cis

(EP) | 189 (171/65) |

| eto/lob

(EL) | 23 (155/14) |

| pem/cis

(PP) | 322 (834/46) |

|

pem/carbo (PC) | 52 (820/539) |

| pem/lob

(PL) | 194 (789/13) |

| pem/oxa

(POX) | 95 (758/123) |

| tax/cis

(TP) | 155 (315/33) |

| tax/lob

(TL) | 37 (313/15) |

| Blood test, mean

(unit) |

|

|

WBC | 6.12

(×109/l) |

|

NEU | 4.26

(×109/l) |

|

NEU% | 67.01 (%) |

|

LYM | 1.51

(×109/l) |

|

LYM% | 26.00 (%) |

| MO | 0.44

(×109/l) |

|

MO% | 5.89 (%) |

| Hb | 119.87 (g/l) |

|

PLT | 207.40

(×109/l) |

|

ToP | 65.91 (g/l) |

|

ALB | 42.99 (g/l) |

|

ALT | 28.48 (U/l) |

|

AST | 28.30 (U/l) |

| Cr | 70.11 (µmol/l) |

| UA | 289.29

(µmol/l) |

| TG | 2.27 (mmol/l) |

|

CHOL | 5.14 (mmol/l) |

| Adverse reactions,

n (%) |

|

| Bone

marrow suppression | 304 (18.3%) |

|

Cachexy | 543 (32.7%) |

| Liver

injury | 377 (22.7%) |

| Interventions, n

(%) |

|

|

rhG-CSF | 485 (29.2%) |

|

Thymosin | 168 (10.1%) |

| Reduced

glutathione | 1356 (81.7%) |

| Table II.Baseline characteristics of patients

in experimental dataset. |

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of patients

in experimental dataset.

|

Characteristics | No. of patients

(n=403) |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

Male | 310 (77.3) |

|

Female | 93 (22.7) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 60.95 (8.26) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.58 (2.88) |

| History of present

illness, n (%) |

|

|

Hypertension | 121 (30.0) |

|

Diabetes mellitus | 33 (8.2) |

| History

of other cancer | 20 (5.0) |

| Weight

loss | 48 (11.9) |

| Personal history, n

(%) |

|

|

Smoking | 252 (62.5) |

|

Drinking | 139 (34.5) |

| Family tumor

history, n (%) | 83 (20.6) |

| Lung cancer Stage,

n (%) |

|

| Early

stage (stage I to II) | 191 (47.4) |

|

Advanced stage (stage III to

IV) | 212 (52.6) |

| Histology, n

(%) |

|

|

NSCLC | 367 (91.1) |

|

SCLC | 36 (8.9) |

| Grade, n (%) |

|

| High

(G1 and G2) | 91 (22.6) |

| Low (G3

and missing) | 312 (77.4) |

| Tumor location, n

(%) |

|

|

Left | 179 (44.4) |

|

Right | 224 (55.6) |

| Table III.Performance of machine learning

models for AEs prediction. |

Table III.

Performance of machine learning

models for AEs prediction.

| Task | Model | AUC | ACC | Precision | Recall |

|---|

|

Myelosuppressive | RF | 0.754±0.037 | 0.709±0.065 | 0.365±0.076 | 0.699±0.102 |

|

| MLP | 0.663±0.047 | 0.683±0.097 | 0.316±0.079 | 0.558±0.195 |

|

| LR | 0.733±0.039 | 0.690±0.074 | 0.344±0.063 | 0.691±0.118 |

|

| AdaBoost | 0.671±0.051 | 0.689±0.074 | 0.326±0.081 | 0.569±0.136 |

| Low-ALB | RF | 0.742±0.026 | 0.721±0.036 | 0.583±0.080 | 0.608±0.093 |

|

| MLP | 0.645±0.043 | 0.659±0.044 | 0.495±0.068 | 0.553±0.128 |

|

| LR | 0.725±0.035 | 0.712±0.034 | 0.563±0.069 | 0.614±0.097 |

|

| AdaBoost | 0.691±0.037 | 0.649±0.052 | 0.495±0.085 | 0.617±0.144 |

| Hepatic

impairment | RF | 0.762±0.034 | 0.724±0.051 | 0.443±0.071 | 0.692±0.089 |

|

| MLP | 0.680±0.044 | 0.653±0.088 | 0.371±0.067 | 0.656±0.099 |

|

| LR | 0.732±0.043 | 0.712±0.069 | 0.431±0.074 | 0.650±0.102 |

|

| AdaBoost | 0.694±0.046 | 0.674±0.069 | 0.386±0.077 | 0.611±0.138 |

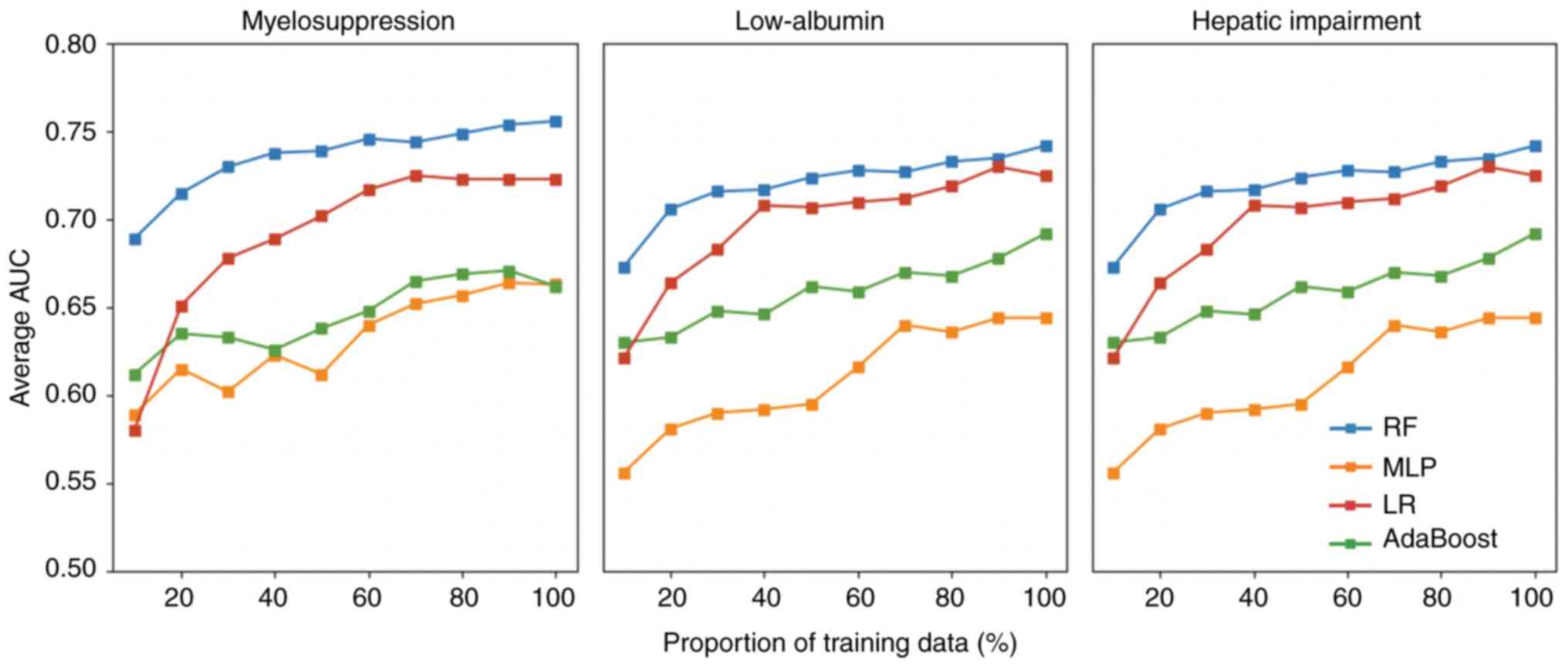

Effect of the number of training sets

on prediction model performance

As shown in Fig. 3,

each model included in the present study exhibited several

instances of performance degradation when the volume of training

data increased in each prediction task; however, overall, a more

pronounced performance of the four models was observed for the

three prediction tasks after increasing the training data volume.

With the exception of the LR model, no significant performance

convergence was observed, indicating performance saturation for

myelosuppression and liver impairment. Thus, we hypothesized that

if more patient data were used, the models could achieve higher

prediction accuracies. Again, the RF model exhibited the best

performance among all four models in any training environment.

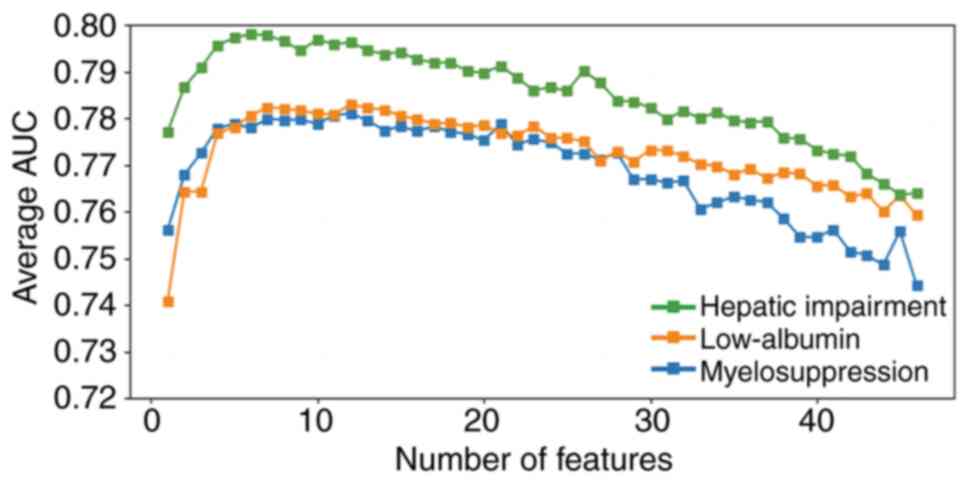

Effect of the number of incorporated

features on the predictive performance of the models

The effect of the number of incorporated features on

the predictive performance of the models was assessed by

individually selecting and overlaying the number of features. Each

feature was numbered from 0 to 45, these and their corresponding

meanings are shown in Table IV.

The results revealed that ≤10 features (Table SII) significantly improved the

performance (Fig. 4). With an

increasing number of incorporated features, the models exhibited

noTable overfitting (25),

resulting in a decreased average AUC. The features in each

predictive model of AEs were ranked based on importance as follows:

i) Myelosuppression: 27, 35, 18, 44, 36, 4, 14, 34, 23, 17, 2, 45,

41, 40, 25, 39, 33, 11, 19, 30, 31, 21, 10, 38, 29, 6, 12, 0, 15,

7, 3, 5, 32, 8, 26, 20, 43, 13, 42, 9, 16, 37, 28, 22, 24, 1, 2;

ii) low-ALB: 36, 23, 1, 26, 10, 30, 31, 35, 45, 34, 37, 9, 28, 29,

39, 6, 42, 19, 18, 20, 16, 4, 5, 21, 41, 33, 12, 40, 0, 15, 3, 7,

38, 43, 27, 44, 32, 17, 25, 13, 24, 2, 11, 22, 8, 14, 3; and iii)

hepatic impairment: 38, 21, 16, 10, 25, 20, 12, 24, 17, 1, 22, 2,

43, 31, 6, 29, 4, 18, 9, 34, 14, 0, 32, 26, 37, 39, 36, 8, 23, 13,

45, 15, 28, 27, 44, 33, 5, 7, 30, 3, 42, 19, 35, 41, 11, 40.

| Table IV.Meaning of feature number. |

Table IV.

Meaning of feature number.

| Number | Feature |

|---|

| 0 | Sex |

| 1 | Age |

| 2 | History of

hypertension |

| 3 | History of

diabetes |

| 4 | Tumor history |

| 5 | Family tumor

history |

| 6 | Smoking |

| 7 | Drinking |

| 8 | Weight loss |

| 9 | Tumor location |

| 10 | Tumor

histology |

| 11 | Tumor grade |

| 12 | Tumor stage |

| 13 | Treatment

interval |

| 14 | doc/lob (DL) |

| 15 | doc/oxa

(DOCOX) |

| 16 | doc/cis (DP) |

| 17 | eto/lob (EL) |

| 18 | eto/cis (EP) |

| 19 | pem/carbo (PC) |

| 20 | pem/lob (PL) |

| 21 | pem/oxa (POX) |

| 22 | pem/cis (PP) |

| 23 | Non-complete

cycle |

| 24 | tax/lob (TL) |

| 25 | tax/cis (TP) |

| 26 | Body mass

index |

| 27 | WBC |

| 28 | NEU |

| 29 | NEU% |

| 30 | LYM |

| 31 | LYM% |

| 32 | MO |

| 33 | MO% |

| 34 | Hb |

| 35 | PLT |

| 36 | ToP |

| 37 | ALB |

| 38 | ALT |

| 39 | AST |

| 40 | Cr |

| 41 | UA |

| 42 | TG |

| 43 | CHOL |

| 44 | Weight (kg) |

| 45 | Clinical

interventions (associated with particular tasks) |

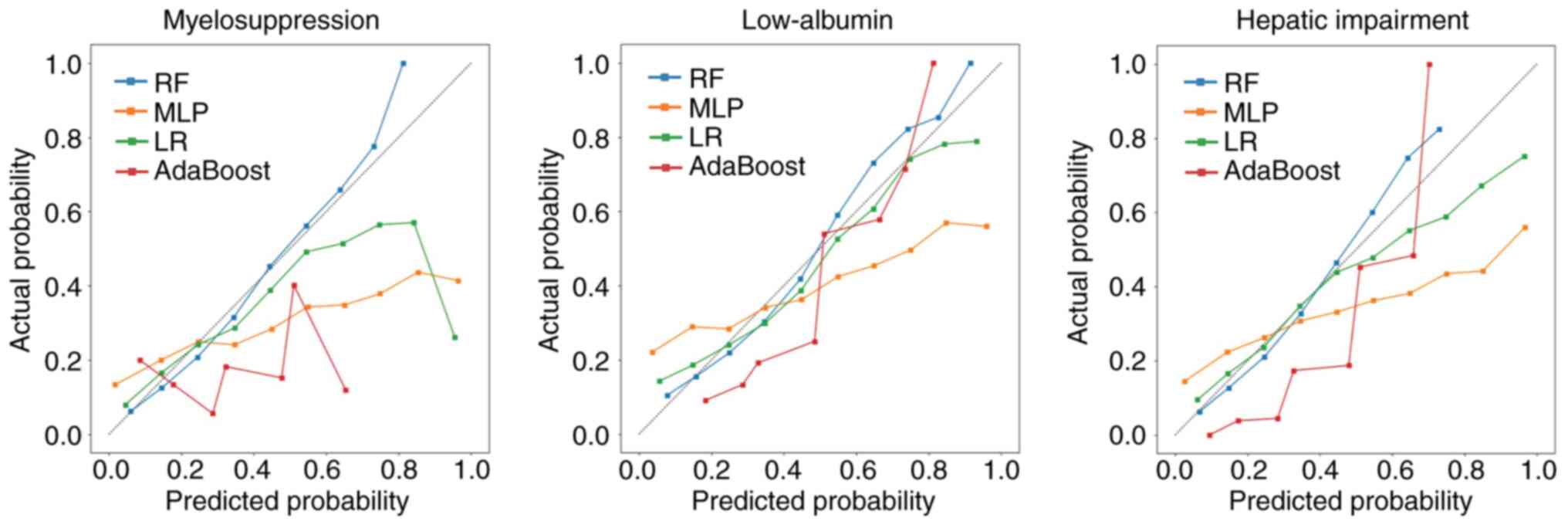

Calibration curve for the predictive

performance of the models

Metric calibration is crucial for evaluating the

accuracy of a model in predicting the probability of an AE

occurring in an individual in the future. This reflects the extent

to which the theoretical risk predicted by a model agrees with the

observed risk. Issues were observed in the MLP and AdaBoost model

calibrations because their calibration curves for predicting

myelosuppression, low ALB levels and hepatic impairment differed

markedly from the optimal values (Fig.

5). Comparatively, the calibration and optimization curves of

the RF model had improved fit for the three prediction tasks,

indicating that the probability of predicting the risk of side

effects in patients suggested by the RF model represented the true

value to a considerable extent. Conversely, the LR model was

significantly under-calibrated for the myelosuppression side

effect, whereas the other two models exhibited calibration degrees

that were similar to that of the RF model.

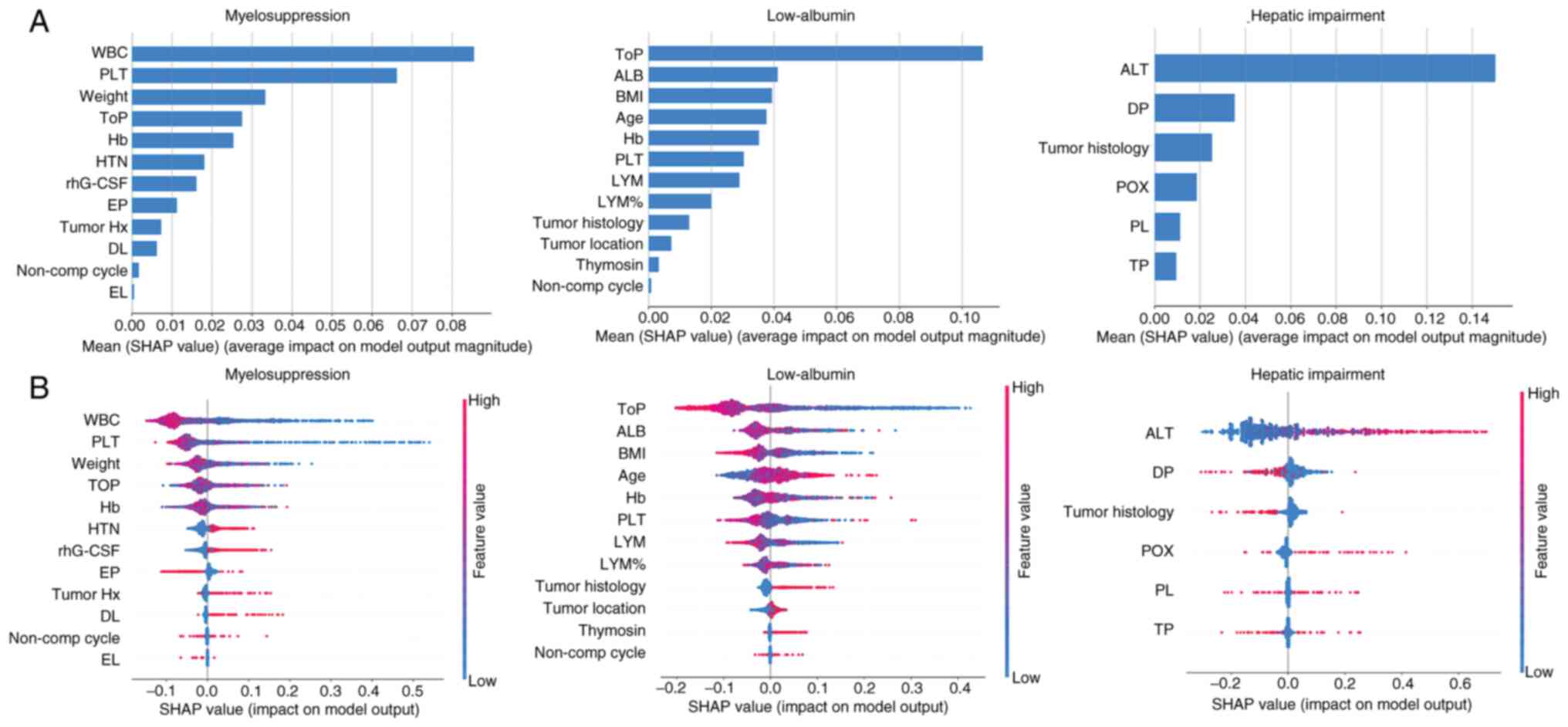

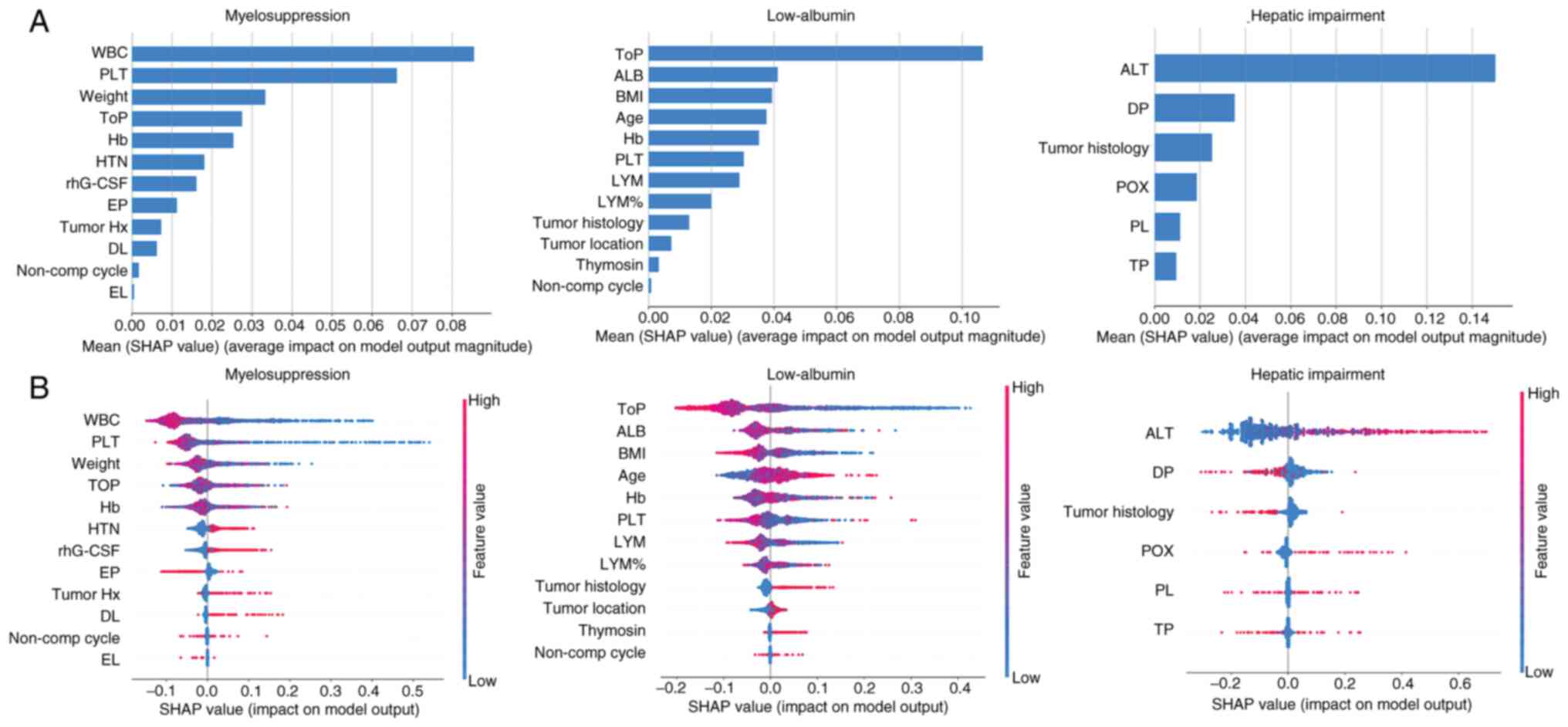

Explanation of predictive models with

SHAP values

To improve the transparency and interpretability of

the model, the SHAP algorithm was used to elucidate the model's

output. The SHAP value of each of the most important features on RF

model output was calculated (Fig.

6). Based on the importance ranking derived from the average

absolute SHAP values, the top five features (WBC, PLT, Weight, ToP,

Hb) were identified as the most significant variables for

predicting myelosuppression. It was demonstrated that ‘ToP’, ‘ALB’,

‘BMI’, ‘Age’ and ‘Hb’ were the five most influential features in

predicting low-ALB. Additionally, ‘ALT’ was identified as the most

significant variable for predicting hepatic impairment. Fig. 6B presents a violin plot for each

feature, illustrating the association between the feature values

and their corresponding SHAP values. The horizontal position

indicates whether a particular feature value contributes to a

higher or lower model prediction. The color gradient reflects

whether the variable value is high (red) or low (blue) for a given

observation. A larger absolute SHAP value indicates a stronger

influence of that feature on the predictions of the RF-based model.

Lower WBC and lower PLT were associated with a higher predicted

probability of myelosuppression. And lower ToP were associated with

a higher predicted probability of low-ALB. It was also observed

that increases in the ALT had a positive influence, directing the

prediction toward hepatic impairment. The SHAP algorithm was also

used to elucidate the other model's output. (Fig. S1, Fig.

S2, Fig. S3). For predictive

tasks assessed using the LR model, ‘WBC’ and ‘PLT’ were found to be

the two most important features in predicting myelosuppression,

‘ToP’ was the most important feature in predicting low-ALB and

‘ALT’ was identified as the most significant variable for

predicting hepatic impairment (Fig.

S1). For predictive tasks using AdaBoost, ‘WBC’, ‘ToP’ or ‘ALT’

were the most influential features in predicting myelosuppression,

low-ALB and hepatic impairment, respectively (Fig. S2). For predictive tasks using MLP,

‘PLT’, ‘WBC’, ‘Hb’, ‘Top’, ‘Weight’ and ‘HTN’ were the six most

influential features in predicting myelosuppression. It was also

demonstrated that ‘ToP’, ‘ALB’, ‘BMI’, ‘Age’, ‘Hb’, ‘PLT’, ‘LYM’

and ‘LYM%’ were the eight most influential features in predicting

low-ALB. Additionally, ‘ALT’, ‘DP’ and ‘Tumor histology’ were

identified as the most significant variable for predicting hepatic

impairment (Fig. S3).

| Figure 6.SHAP values and feature interaction

scores in machine learning-based prediction. (A) The most important

features for the prediction of chemotherapy-associated adverse

effects (ranked from most to least important). (B) The distribution

of the impacts of each of the most important features on model

output. The horizontal location shows whether the effect of that

value is associated with a higher or lower prediction. The colors

represent the feature values: Red for larger values and blue for

smaller values. SHAP, Shapley Additive Explanation; WBC, white

blood cell; PLT, platelet; ToP, total protein; Hb, hemoglobin; HTN,

hypertension; rhG-CSF, recombinant-human granulocyte colony

stimulating factor; EP, etoposide/cisplatin; Tumor Hx, tumor

history; DL, docetaxel/lobaplatin; non-comp, non-complete; EL,

etoposide/lobaplatin; ALB, albumin; BMI, body mass index; LYM,

lymphocytes; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DP,

docetaxel/cisplatin; POX, pemetrexed/oxaliplatin; PL,

pemetrexed/lobaplatin; TP, paclitaxel/ cisplatin. |

Discussion

Chemotherapy-associated side effects are among the

major concerns for clinicians, in addition to the efficacy of

treatment. The AEs of chemotherapy agents for lung cancer involve

numerous organ systems (11). The

AEs of chemotherapeutic drugs are complex, their side effects vary

from person to person, and their side effects do not occur

immediately after taking the drugs. Untimely and incomplete

interventions worsen common AEs, thereby affecting the routine

chemotherapy cycle of patients and aggravating socioeconomic

burdens on patients. Therefore, developing an effective method for

predicting chemotherapy-associated AEs to guide clinicians to

intervene in patients promptly is imperative, and the importance

and necessity of an effective and accurate tool for predicting the

side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs are clear.

It is difficult to predict AEs promptly with

traditional statistical techniques, and it is feasible to use

genomics and biomarkers to identify individuals who are susceptible

to AEs (26). However, late-stage

prognosis prediction may be less accurate due to the tumor

heterogeneity induced by chemotherapy. At present, several scholars

are employing data mining, ML or artificial intelligence (AI)

methods to predict potential adverse drug reactions. Numerous

scholars integrate the indications, known adverse drug reactions,

chemical structures and biological properties of drugs in various

drug databases, combined with tumor- or drug-related human gene

expression features, and use ML algorithms to predict the potential

side effects of drugs, which is helpful for guiding drug clinical

trials and monitoring the AEs of existing commercial drugs

(12–14). Among the emerging novel methods, ML

methods have comprehensively outperformed traditional methods in

predicting the side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs. Predictive

models developed for drugs, targets and AEs using deep learning

techniques, knowledge graphs and biomedicine outperform traditional

methods. However, databases developed for accumulating information

on drug side effects contain complex, limited and unauthorized

information.

In general, few studies have investigated the

prediction of AEs of chemotherapy (27,28).

Dranitsaris et al (29)

performed a study specifically focused on chemotherapy-induced

nausea and vomiting. Boudali and Messaoud (30) developed ML models to predict

chemotherapy-related toxicity. Most studies use limited variables

that are not closely related to clinical work. Chemotherapeutic

drugs have been used for a long time, and the types of adverse

reactions associated with them are almost universally known.

However, accurately predicting AEs that may occur in patients

during chemotherapy is impossible in the clinical setting.

Recently, Shandong University researchers developed four ML models

using 11 clinical variables that predicted chemotherapy-associated

AEs with an overall AUC of 0.88 and greater accuracy for specific

toxicities in patients with colorectal cancer (31). Additionally, some common AEs,

including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anaphylaxis, kidney injury

and liver injury, despite timely intervention, cannot be

effectively avoided, and in some cases, they can be aggravated

during chemotherapy. On the other hand, the potential of ML for

accurate prediction is often compromised by inherent discrepancies

between training data and real-world clinical environments

(32).

While AI models may demonstrate strong statistical

performance, they frequently fall short in practical clinical

applications (33). Thus, the use

of real-world clinical data can accurately reflect the current

clinical situation and help address clinical problems (15). Thus, in the present study, the

characteristic information of patients with lung cancer were fully

incorporated, including baseline features, lung cancer features,

chemotherapeutic agent features, blood marker features and adverse

reaction interventions. An ML-based prediction model for

chemotherapy-associated AEs was constructed and the AEs of patients

with lung cancer during several cycles of chemotherapy were

monitored. Clinical data and ML methods were used to solve the

aforementioned clinical issues, providing novel insights into

chemotherapy-associated research on lung cancer. ML was

demonstrated to be an important method to solve the clinical

problems in the future. Compared with classical statistical

regression models, ML techniques are capable of capturing complex

nonlinear relationships among predictors, handling high-dimensional

data with intricate interactions and providing accurate

personalized predictions.

In addition to the LR model, the present study

employed several ML algorithms, including RF, MLP and AdaBoost, to

predict chemotherapy-associated AEs in patients with lung cancer.

The results demonstrated that the RF model outperformed the other

models, exhibiting the highest stability and alignment with

clinical intuition. Current research has evolved from exploring

single data sources and simple models to integrating multi-modal

data and complex model architectures, continuously improving

prediction performance and gradually enhancing interpretability.

However, challenges such as model generalization ability,

interpretability and ethical compliance still exist and require

multidisciplinary cooperation to resolve. We hypothesize that the

future trend will be the integration of multi-modal data, such as

unified database combining EHR, imaging, pathology, genomics and

real-time monitoring data processed by Transformer or graph-based

architectures to capture cross-modal interactions (34,35).

At the same time, successful clinical integration needs to be

clinical needs-oriented and seamlessly embedded into workflows.

At present, numerous hospitals have implemented

IT-based system, such as computerized physician order entry systems

or unreasonable medical orders monitoring system, to reduce

prescribing errors. ML is gradually being implemented in clinical

practice within the field of cardiovascular diseases (36). The integration of these innovative

models holds noTable promise for predicting the severity of atrial

fibrillation substrates and in-hospital mortality (37). The chemotherapy-associated AEs

prediction model could be automatically triggered when a physician

enters chemotherapy orders into the system, which is called

pre-chemotherapy planning monitoring. For multi-cycle chemotherapy,

the condition of a patient may evolve over time. Prior to each new

cycle, the system could re-run the model using the most up-to-date

clinical data to update risk predictions and assist oncologists in

making informed treatment adjustments. ML models could stratify

patients into high- and medium-risk categories, proactively

initiating appropriate follow-up actions and additional laboratory

tests. These interventions align with authoritative guidelines such

as those from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, enabling

timely and appropriate responses to potential side effects.

Furthermore, close collaboration with hospital IT departments and

EHR vendors is essential to overcome technical challenges,

including data standardization and system integration. We

hypothesize that the ML-based prediction model will help clinicians

in everyday practice manage patients treated with chemotherapy.

Nevertheless, ML is neither an omnipotent tool nor

the perfect solution. Ideally, an appropriate method should be

selected according to the problems to be addressed. Moreover,

inputting high raw medical data volumes into ML algorithms without

analysis cannot yield the expected results (38). Instead, more attention should be

paid to cross-disciplinary research, fully integrating the

knowledge of multiple disciplines and selecting appropriate

algorithms to improve algorithms to advance future AI-assisted

clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Zhejiang Province

Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Plan Project

(grant no. 2026ZL0474), ‘Leading Goose’ Research and Development

Program of Zhejiang (grant no. 2025C02057) and the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82372773).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The original code and data

have been deposited at GitHub (https://github.com/ZJU-BMI/cancer).

Authors' contributions

SH, ZFH, ZXH and JH conceptualized and deigned the

present study. SH and ZJS wrote the original draft of the

manuscript and were involved in graph drawing. SH and ZWH designed

and performed the critical additional experiments and revised the

manuscript. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by TAX, ZXH and

ZFH. JH was responsible for raw data collection, critical revision

of the manuscript, supervision and project administration.

Provision of study materials or patients was performed by SH, ZJS

and TAX. Data collection and assembly were performed by XYZ and SL.

ZJS, TAX and ZXH were involved in data analysis and interpretation.

JH and ZFH confirm the authenticity of all raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Clinical

Research Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, School

of Medicine, Zhejiang University (approval no. IIT20200016A).

Patients were informed that the clinical information were stored by

the hospital and potentially used for scientific research, and

signed informed consent to participants was waived by the Ethics

Committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AEs

|

adverse effects

|

|

ALB

|

albumin

|

|

ALT

|

alanine aminotransferase

|

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

|

AI

|

artificial intelligence

|

|

BMI

|

body mass index

|

|

EHR

|

electronic health record

|

|

EPV

|

events-per-variable

|

|

Hb

|

hemoglobin

|

|

LR

|

logistic regression

|

|

ML

|

machine learning

|

|

MLP

|

multi-layer perceptron

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

PLT

|

platelet

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

curve

|

|

RECIST

|

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid

Tumors

|

|

RF

|

random forest

|

|

ToP

|

total protein

|

|

WBC

|

white blood cells

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng

H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ and He J: Cancer statistics in China,

2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 66:115–132. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cao M and Chen W: Epidemiology of lung

cancer in China. Thorac Cancer. 10:3–7. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Asamura H, Nishimura KK, Giroux DJ,

Chansky K, Hoering A, Rusch V and Rami-Porta R; Members of the

IASLC Staging, Prognostic Factors Committee of the Advisory Boards,

Participating Institutions, : IASLC Lung cancer staging project:

The new database to inform revisions in the ninth edition of the

TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 18:564–575.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pirker R: Chemotherapy remains a

cornerstone in the treatment of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr

Opin Oncol. 32:63–67. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Powell SF, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Langer CJ,

Tafreshi A, Paz-Ares L, Kopp HG, Rodríguez-Cid J, Kowalski DM,

Cheng Y, Kurata T, et al: Outcomes with pembrolizumab plus

platinum-based chemotherapy for patients with NSCLC, sTable brain

metastases: Pooled analysis of KEYNOTE-021, −189, and −407. J

Thorac Oncol. 16:1883–1892. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M,

Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, Felip E, Broderick SR, Brahmer JR, Swanson

SJ, et al: Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resecTable

lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 386:1973–1985. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang C, Qiao W, Jiang Y, Zhu M, Shao J,

Wang T, Liu D and Li W: The landscape of immune checkpoint

inhibitor plus chemotherapy versus immunotherapy for advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Cell Physiol. 235:4913–4927. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jiang J, Wang Y, Gao Y, Sugimura H,

Minervini F, Uchino J, Halmos B, Yendamuri S, Velotta JB and Li M:

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy in non-small cell

lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Lung

Cancer Res. 11:277–294. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

NSCLC Meta-analysis Collaborative Group, .

Preoperative chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data.

Lancet. 383:1561–1571. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lavan AH, O'Mahony D, Buckley M, O'Mahony

D and Gallagher P: Adverse drug reactions in an oncological

population: Prevalence, predictability, and preventability.

Oncologist. 24:e968–e977. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu M, Wu Y, Chen Y, Sun J, Zhao Z, Chen

XW, Matheny ME and Xu H: Large-scale prediction of adverse drug

reactions using chemical, biological, and phenotypic properties of

drugs. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 19:e28–e35. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang Z, Clark NR and Ma'ayan A:

Drug-induced adverse events prediction with the LINCS L1000 data.

Bioinformatics. 32:2338–2345. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Luo H, Fokoue-Nkoutche A, Singh N, Yang L,

Hu J and Zhang P: Molecular docking for prediction and

interpretation of adverse drug reactions. Comb Chem High Throughput

Screen. 21:314–322. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, Meizinger C

and Skolnik NS: Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical

data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 35:1763–1774. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shickel B, Tighe PJ, Bihorac A and Rashidi

P: Deep EHR: A survey of recent advances in deep learning

techniques for Electronic Health Record (EHR) analysis. IEEE J

Biomed Health Inform. 22:1589–1604. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Rajkomar A, Oren E, Chen K, Dai AM, Hajaj

N, Hardt M, Liu PJ, Liu X, Marcus J, Sun M, et al: Scalable and

accurate deep learning with electronic health records. NPJ Digit

Med. 1:182018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Choi E, Schuetz A, Stewart WF and Sun J:

Using recurrent neural network models for early detection of heart

failure onset. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 24:361–370. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bernardini M, Romeo L, Misericordia P and

Frontoni E: Discovering the type 2 diabetes in electronic health

records using the sparse balanced support vector machine. IEEE J

Biomed Health Inform. 24:235–246. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tseng PY, Chen YT, Wang CH, Chiu KM, Peng

YS, Hsu SP, Chen KL, Yang CY and Lee OK: Prediction of the

development of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery by

machine learning. Crit Care. 24:4782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu X, Zheng D, Zhong Y, Xia Z, Luo H and

Weng Z: Machine-learning prediction of oral drug-induced liver

injury (DILI) via multiple features and endpoints. Biomed Res Int.

2020:47951402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A,

Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R,

Dubourg V, et al: Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J Mach

Learn Res. 12:2825–2830. 2011.

|

|

23

|

Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE,

Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, Burovski E, Peterson P,

Weckesser W, Bright J, et al: Author correction: SciPy 1.0:

Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nat

Methods. 17:3522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Huang S, He T, Yang S, Sheng H, Tang X,

Bao F, Wang Y, Lin X, Yu W, Cheng F, et al: Metformin reverses

chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer via accelerating

ubiquitination-mediated degradation of Nrf2. Transl Lung Cancer

Res. 9:2337–2355. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Murphy KP: Machine learning: A

probabilistic perspective. The MIT Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts:

2012

|

|

26

|

Carr DF and Pirmohamed M: Biomarkers of

adverse drug reactions. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 243:291–299. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kheifetz Y and Scholz M: Individual

prediction of thrombocytopenia at next chemotherapy cycle:

Evaluation of dynamic model performances. Br J Clin Pharmacol.

87:3127–3138. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang Y, Zhang R, Shen Y, Su L, Dong B and

Hao Q: Prediction of chemotherapy adverse reactions and mortality

in older patients with primary lung cancer through frailty index

based on routine laboratory data. Clin Interv Aging. 14:1187–1197.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Dranitsaris G, Molassiotis A, Clemons M,

Roeland E, Schwartzberg L, Dielenseger P, Jordan K, Young A and

Aapro M: The development of a prediction tool to identify cancer

patients at high risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Ann Oncol. 28:1260–1267. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Boudali I and Messaoud IB: Machine

learning models for toxicity prediction in chemotherapy.

Intelligent Systems Design and Applications. Springer Nature

Switzerland Cham; pp. 350–364. 2023, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wu Y, Zhao W, Zhang L, Wang Y, Wen Y and

Liu L: Machine learning models for predicting chemotherapy-induced

adverse drug reactions in colorectal cancer patients. Dig Liver

Dis. 57:1845–1852. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Polevikov S: Advancing AI in healthcare: A

comprehensive review of best practices. Clin Chim Acta.

548:1175192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Adlung L, Cohen Y, Mor U and Elinav E:

Machine learning in clinical decision making. Med. 2:642–665. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kline A, Wang H, Li Y, Dennis S, Hutch M,

Xu Z, Wang F, Cheng F and Luo Y: Multimodal machine learning in

precision health: A scoping review. NPJ Digit Med. 5:1712022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zheng S, Zhu Z, Liu Z, Guo Z, Liu Y, Yang

Y and Zhao Y: Multi-modal graph learning for disease prediction.

IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 41:2207–2216. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Luscher TF, Wenzl FA, D'Ascenzo F,

Friedman PA and Antoniades C: Artificial intelligence in

cardiovascular medicine: Clinical applications. Eur Heart J.

45:4291–4304. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Petzl AM, Jabbour G, Cadrin-Tourigny J,

Pürerfellner H, Macle L, Khairy P, Avram R and Tadros R: Innovative

approaches to atrial fibrillation prediction: Should polygenic

scores and machine learning be implemented in clinical practice?

Europace. 26:euae2012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Couckuyt A, Seurinck R, Emmaneel A,

Quintelier K, Novak D, Van Gassen S and Saeys Y: Challenges in

translational machine learning. Human Genetics. 141:1451–1466.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|