Introduction

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are

regulatory mechanisms that modulate protein function, serving roles

in cellular signaling and disease pathogenesis (1–4).

Chromatin is a dynamic nucleoprotein complex localized in cell

nuclei, consisting of DNA, histones, non-histone proteins and small

regulatory RNAs. It serves a role in essential nuclear processes,

including the regulation of gene expression, DNA replication and

repair and mitotic chromosome segregation (5–8). The

N-terminal tails of core histones represent the major sites for

post-translational chromatin modifications, which dynamically

regulate chromatin accessibility and function (9). Aberrant histone PTMs constitute a

fundamental epigenetic mechanism in oncogenesis that dysregulates

transcriptional networks, DNA repair fidelity and the fate of the

cell, which promotes tumor development and metastatic competence

(10–14).

Lactate is a key signaling molecule that mediates

intercellular communication, with protein lactylation, a novel PTM,

emerging as a central mechanism underlying lactate-dependent

regulation. This epigenetic modification promotes tumor progression

through lactate accumulation-dependent mechanisms and the

subsequent activation of specific lactylation-promoting

acyltransferases (15,16). First identified as a novel PTM in a

study by Zhang et al (17)

in 2019, histone lactylation is a ubiquitously present,

evolutionarily conserved and dynamically regulated lactate-mediated

epigenetic mark. Furthermore, it is preferentially enriched at gene

promoters and enhancers, serving as a potential indicator of

transcriptionally active chromatin (17,18).

As an epigenetic regulation, histone lactylation mediates

transcriptional control through lactyl group deposition on histone

lysines, which alters nucleosome dynamics and DNA-histone

interactions (19). Histone

lactylation serves a role in cancer progression and treatment

resistance, with aberrant histone lactylation levels serving as a

prognostic indicator for patients with cancer (20,21).

Targeting histone lactylation may potentially be used for precision

cancer therapy (22,23).

The present review discussed the current knowledge

on histone lactylation and emphasized its role as a pivotal

metabolic-epigenetic nexus in cancer. The present review described

its mechanistic contributions to tumor progression, immune evasion

and therapy resistance. Furthermore, the cascading interplay

between lactylation and other PTMs (histone acetylation and histone

methylation) were evaluated and emerging therapeutic strategies

targeting the lactylation axis were discussed.

Lactate metabolism and lactate

transport

During glycolysis, glucose undergoes sequential

enzymatic breakdown to yield pyruvate, which is subsequently

converted to lactate via NADH-dependent reduction. This process is

catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), resulting in lactate

accumulation (24). Lactate is

actively shuttled across cellular membranes via monocarboxylate

transporters (MCTs) (25). Under

conditions of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion and hypoxia,

oxidative phosphorylation is compromised, leading to suppression of

the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the upregulation of glycolytic

flux to maintain cellular ATP levels (26). During physiological stress, such as

intense exercise, skeletal muscle cells exhibit marked lactate

production. This metabolic byproduct contributes to an increase in

the carbon dioxide concentrations, which stimulates the respiratory

center to enhance pulmonary ventilation, thereby meeting the

increased oxygen demands (27).

During inflammation, lactate functions as a pleiotropic signaling

molecule that orchestrates immune cell responses during

inflammation (28).

The core function of mitochondria is to generate

energy through oxidative phosphorylation. Under normal

physiological conditions, pyruvate enters the mitochondria and is

metabolized, resulting in minimal lactate production. However,

during mitochondrial dysfunction, the transport of pyruvate into

mitochondria is impaired, resulting in cells being reliant on

glycolysis, which leads to lactate accumulation. Therefore, the

metabolic state of mitochondria determines the intracellular levels

of lactate (29–31). Abnormal lactate accumulation

promotes tumorigenesis and progression through histone lactylation

(25,32,33).

In the Warburg effect, glucose is preferentially converted into

lactate to facilitate rapid energy production, which is concomitant

with metabolic reprogramming that is characterized by enhanced

aerobic glycolysis, lactate accumulation, suppressed mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation and compromised mitochondrial function

(34,35).

Histone lactylation in tumor

progression

Histones are highly conserved, nuclear-encoded basic

proteins characterized by their abundance of positively charged

amino acids (lysine and arginine residues) (16). As the core structural components of

nucleosomes, they organize and compact eukaryotic DNA into

chromatin (36). In addition to

their architectural role, histones dynamically regulate essential

nuclear processes including transcriptional control, DNA damage

response and mitotic chromosome segregation (36). Histones are classified into two

categories, namely core and linker histones. The core histones

(H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) form the octameric structural scaffold of

nucleosomes, while the H1 linker histone binds to the

inter-nucleosomal DNA regions (16,37,38).

Histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation

(H3K18la) in tumor progression

Multiple histone lactylation sites are identified on

histone H3 and H4 (39,40). Since its initial identification,

H3K18la is the most studied histone lactylation site (17). Previous studies demonstrate that

H3K18la influences tumor initiation, progression and metastasis

through transcriptional regulation (41,42).

In uveal melanoma, H3K18la transcriptionally upregulates YTH

N6-methyladenosine RNA-binding protein F2 (YTHDF2), which promotes

uveal melanoma pathogenesis. Mechanistically, YTHDF2 recognizes and

binds to N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-modified period circadian

regulator 1 and TP53 mRNAs, which facilitates their degradation and

accelerates uveal melanoma tumorigenesis (43). In ocular melanoma, increased levels

of H3K18la epigenetically activates the transcription of

α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase homolog 3 (ALKBH3). ALKBH3

mediates the N1-methyladenosine demethylation of SP100A mRNA, which

promotes malignant transformation (44). In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

histone lactylation (H3K18la) and histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation

(H3K27ac) cooperatively regulate tumor progression through an

epigenetic cascade mechanism. H3K18la upregulates the expression of

the m6A reader protein YTH m6A RNA binding protein C1 (YTHDC1),

which stabilizes m6A-modified long non-coding RNA nuclear

paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1) and recruits histone

acetyltransferase p300 to the promoter region of the stearoyl-CoA

desaturase (SCD) gene. This leads to increased histone H3K27ac

levels, which activates the expression of SCD, induces fatty acid

metabolic reprogramming and promotes HCC progression (45). This exemplifies a complex cascade of

epigenetic modifications, in which histone lactylation (H3K18la)

acts as an upstream regulator that promotes downstream histone

acetylation (H3K27ac), and induces oncogenic metabolic

reprogramming. This exemplifies a complex cascade of epigenetic

modifications, in which histone lactylation acts as an upstream

regulator that directly promotes downstream histone acetylation,

thereby driving oncogenic metabolic reprogramming. It underscores

that histone PTMs do not function in isolation but can form a

hierarchical cascade, with upstream modifications dictating

downstream epigenetic events. In glioblastoma (GBM), the NF-κB

pathway promotes H3K18la via the Warburg effect, which enhances the

expression of the long non-coding RNA LINC01127. Subsequently,

LINC01127 activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

kinase kinase 4/JNK/NF-κB signaling axis, promoting self-renewal of

GBM stem cells (46).

Dysfunctional mitochondrial processes (including

impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and dysregulated

mitophagy) and proteins [such as sirtuin (SIRT), Parkin and Numb]

serve as central therapeutic targets in various diseases (such as

neurodegenerative diseases, cancer and metabolic disorders)

(47–55). Glycolysis and oxidative

phosphorylation are the primary pathways for cellular energy

production. When mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is

impaired, glycolysis is enhanced, leading to an increased

accumulation of lactic acid in cells, which further influences

histone lactylation (34). SIRT 4,

a member of the mitochondrial SIRT family, serves a key role in

regulating mitochondrial function. As a mitochondrial protein,

SIRT4 deacetylates glycolytic enzyme α-enolase at lysine 358. This

promotes a metabolic shift from mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation to glycolysis and enhances lactate production. The

accumulated lactate subsequently induces histone lactylation

(H3K18la and H3K9la), which activates stemness-related pathways via

epigenetic reprogramming, and enhances the stem-like properties of

pancreatic cancer (PCA) cells (52).

Mitophagy is a highly conserved and crucial cellular

self-cleaning process. Its function is to maintain intracellular

homeostasis by removing damaged mitochondria. This ensures that

there is an energy supply and prevents the release of pro-apoptotic

factors (such as cytochrome c and second mitochondria-derived

activator of caspases) and excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS)

that could lead to cellular damage or death (53,54).

The regulation of mitophagy influences cancer development (47). In prostate and lung cancer, the cell

fate determinant Numb binds to and promotes Parkin-mediated

mitophagy, which maintains mitochondrial stability. When the

Numb/Parkin axis is impaired, damaged mitochondria accumulate,

which triggers a metabolic reprogramming toward aerobic glycolysis.

This shift increases lactate production, which subsequently induces

epigenetic reprogramming via histone lactylation (H3K18la),

activating the transcription of neuroendocrine-related genes such

as synaptophysin, neural cell adhesion molecule-1 and

neuron-specific enolase. Ultimately, this process promotes the

transformation of cancer cells toward a neuroendocrine phenotype

and confers therapy resistance (55).

H3K18la also functions as a key epigenetic promoter

of metastatic progression in multiple types of cancer, such as HCC,

CRC, endometrial carcinoma and BC (33,41,42,56,57). A

study by Wang et al (56)

demonstrates using in vitro and in vivo experiments

that pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 (PYCR1) increases insulin

receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) expression levels by promoting H3K18la

at the IRS1 promoter region. This PYCR1/H3K18la/IRS1 axis

subsequently activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, which

promotes the proliferation and migration of HCC cells. H3K18la

promotes colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastasis (CRLM) by

upregulating the expression of cell division cycle 27.

Mechanistically, this is promoted by lactate accumulation, which

results from the ubiquitin-specific peptidase 3 (USP3)-antisense

RNA 1/USP3/MYC axis-mediated activation of the glycolytic pathway

(41). Bioinformatic analysis

reveals that histone lysine lactylation (Kla) serves as a poor

prognostic biomarker in breast cancer (BC), which under high

glycolytic flux promotes BC cell proliferation and migration by

increasing c-Myc expression levels, upregulating

serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 10 and consequently modulating

the alternative splicing of murine double minute 4 and Bcl-x

(33,57). In endometrial carcinoma, H3K18la

positively regulates the expression of USP39. Subsequently, USP39

activates the PI3K/AKT/hypoxia inducible factor 1α signaling

pathway, promoting lactate production, proliferation and metastasis

(42).

Histone lactylation at other

sites

In addition to the well-characterized H3K18la, other

known lactylation sites include H3K27la, H3K14la, H3K9la and

H3K56la on histone H3, as well as histone H4 lysine 5 lactylation

(H4K5la), H4K8la, H4K12la and H4K16la on histone H4 (39,40,58).

These modifications exhibit distinct regulatory roles in tumor

progression, with mechanisms that include: i) Inhibition of tumor

apoptosis (59,60); ii) regulation of tumor metastasis

and invasion (61,62); and iii) induction of cellular

senescence and telomerase inhibition (58).

Bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation

using clinical samples reveals H4K12la as a novel prognostic

biomarker for triple-negative BC (TNBC) (59). A study by Li et al (60) demonstrates that lactate mediates

H4K12la binding to the Schlafen 5 (SLFN5) promoter region, which

suppresses the transcription of SLFN5 and subsequently inhibits

apoptosis in TNBC. Hypoxia-induced H3K9la promotes migration and

invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) by

upregulating the expression of laminin subunit g 2 (LAMC2).

Mechanistic study further revealed that LAMC2 enhances the

expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by activating the

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (61).

In patients with neuroblastoma (NB), low expression

levels of DnaJ heat shock protein family member C12 (DNAJC12) is

associated with poor clinical outcomes. Functionally, DNAJC12

deficiency upregulates the expression of collagen type Iα1 through

H4K5la-mediated epigenetic regulation, which promotes NB cell

invasion and metastasis. Mechanistically, this process involves

DNAJC12 downregulation enhances the glycolytic pathway by

upregulating key enzymes such as hexokinase 2, pyruvate kinase

M1/M2 (PKM), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and LDHB. This

activation leads to lactate accumulation, which in turn promotes

H4K5la (62).

In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), liver kinase B1

regulates lactate metabolism to suppress H4K8la and H4K16la, which

inhibits telomerase reverse transcriptase gene expression and

represses telomerase activity, leading to senescence in LUAD cells

(58).

Histone lactylation, particularly H3K18la, promotes

oncogenesis across various types of cancer (such as HCC, CRC, BC,

GBM and LUAD) through epigenetic reprogramming, metabolic rewiring

and the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways (such as the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α signaling

pathway) by modulating chromatin architecture and transcriptional

regulation. Additional lactylation sites (H4K8la, H4K16la, H4K12la,

H3K9la, H4K5la) are implicated in tumor progression through diverse

mechanisms including apoptosis inhibition, metastasis promotion and

cellular senescence inhibition (Table

I). However, notable gaps in the knowledge remain regarding the

functional roles and specific downstream targets of H3K27la and

H3K56la in carcinogenesis. Furthermore, studies on histone

lactylation sites predominantly focus on a single type of cancer,

highlighting the need for systematic pan-cancer analyses (58–61).

| Table I.Effects of histone lactylation on

tumor cells. |

Table I.

Effects of histone lactylation on

tumor cells.

| First author,

year | Type of cancer | Lactylation

site | Downstream

targets | Associated

molecules or pathways | Effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhou et al,

2025 | CRC | H3K18la | CDC27 | Not mentioned | Liver

metastases | (41) |

| Wei et al,

2024 | EC | H3K18la | USP39 | PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α

signaling pathway | Proliferation and

metastasis | (42) |

| Yu et al,

2021 | Uveal melanoma | H3K18la | YTHDF2 | PER1 and TP53 | Oncogenesis | (43) |

| Gu et al,

2024 | Ocular

melanoma | H3K18la | ALKBH3 | SP100A | Progression | (44) |

| Du et al,

2024 | HCC | H3K18la | YTHDC1 | NEAT1, p300 and

H3K27ac | Progression | (45) |

| Li et al,

2023 | GBM | H3K18la | LINC01127 | MAP4K4/JNK/NF-κB

axis | Stem cells

self-renew | (46) |

| Wang et al,

2024 | HCC | H3K18la | IRS1 | PI3K/Akt/mTOR

signaling pathway | Proliferation and

migration | (56) |

| Pandkar et

al, 2023 | BC | H3K18la | c-Myc | SRSF10, MDM4 and

Bcl-x | Proliferation and

migration | (33) |

| Liu et al,

2024 | LUAD | H4K8la and

H4K16la | TERT | Not mentioned | Cellular

senescence | (58) |

| Li et al,

2024 | TNBC | H4K12la | SLFN5 | Not mentioned | Progression | (60) |

| Zang et al,

2024 | ESCC | H3K9la | Not mentioned | PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway and VEGFA | Migration and

invasion | (61) |

| Yang et al,

2025 | NB | H4K5la | COL1A1 | Not mentioned | Migration and

invasion | (62) |

Histone lactylation modulates tumor

progression by remodeling the tumor microenvironment (TME)

Tumor-associated macrophages

(TAMs)

First revealed in macrophage research, histone

lactylation promotes the expression of M2-like

macrophage-associated genes (17).

Further studies reveal that histone lactylation promotes tumor

progression by inducing M2 polarization of TAMs (21,63–66).

A study by Li et al (21) demonstrates that lactate derived from

CRC cells promotes tumorigenesis by inducing H3K18la in

macrophages, which suppresses the expression of retinoic acid

receptor γ and activates the TNF receptor associated factor

6-IL-6-STAT3 signaling axis.

In bladder cancer (BLCA), combining single-cell RNA

sequencing with computational biology and functional assays, a

study by Deng et al (63)

reveals that H3K18la epigenetically enhances parkin RBR E3

ubiquitin protein ligase transcription. This promotes both

mitochondrial autophagy and M2-like polarization in TAMs, which

forms an immunosuppressive microenvironment that increases BLCA

progression. Additionally, under hypoxic conditions, lactate

produced by glioma cells promotes M2 polarization of TAMs through

the MCT1/H3K18la/TNF superfamily member 9 axis (64). In addition, H3K18la in macrophages

upregulates the expression of nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1), which

promotes M2-like polarization through the suppression of ERK and

JNK signaling pathways. This NUPR1-mediated reprogramming increases

the levels of immune checkpoint molecules programmed death ligand 1

(PD-L1) and signal regulatory protein α, which induces

CD8+ T-cell dysfunction and compromises the efficacy of

immunotherapy (65). In PCA,

lactate-induced H3K18la activates acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2

(ACAT2) at the transcriptional level, establishing a positive

feedback loop of lactate/H3K18la/ACAT2/mitochondrial carrier

homolog 2, which impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation

and promotes lactate accumulation. In addition, ACAT2 facilitates

cholesterol transport via small extracellular vesicles, which

promotes the M2 polarization of TAMs (66).

In addition to its role in macrophage polarization,

histone lactylation can also regulate the phagocytic capacity of

macrophages. In PTEN/p53-deficient aggressive PCA, tumor-derived

lactate suppresses the phagocytic function of TAMs via H3K18la,

which promotes tumor progression (67). Elevated H3K18la levels in

tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells upregulates the expression of

methyltransferase-like 3, which increases the RNA m6A modification.

This subsequently increases the mRNA translation efficiency of

Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and activates the JAK1/STAT3 signaling

pathway, which amplifies the immunosuppressive function of

tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells in tumors (68).

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

(CAFs)

Functioning as critical microenvironmental

modulators, CAFs contribute to tumor pathogenesis (69). Lactate derived from lung cancer

cells promotes the expression of collagen triple helix

repeat-containing 1 (CTHRC1) in CAFs via H3K18la, which maintains

their CTHRC1+ CAF phenotype. These activated

CTHRC1+ CAFs subsequently upregulate the expression of

hexokinase 2 in tumor cells through the activation of TGF-β/Smad

signaling. This then induces a resistance to epidermal growth

factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and enhances glycolytic

metabolism in lung cancer cells (70).

Neutrophils

G protein-coupled receptor 37 promotes CRLM

progression through dual mechanisms: i) It activates the Hippo

signaling pathway to enhance tumor cell proliferation; and ii) it

upregulates the expression of chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)

1 and 5 via H3K18la, which promotes neutrophil accumulation in the

TME. These coordinated actions establish a pro-metastatic niche

that facilitates CRLM development (71). Hypoxia-induced glycolytic activation

in neutrophils increases lactate-dependent histone lactylation,

which transcriptionally activates arginase-1 to enhance

immunosuppression. Inhibition of this lactylation pathway reverses

neutrophil-mediated immune evasion and improves the response of

brain tumors to immunotherapy (72).

CD8+ T cells

Histone lactylation exhibits dual roles in

modulating CD8+ T cell function in the TME. Tumor

cell-intrinsic histone lactylation induces CD8+ T cell

exhaustion; however, CD8+ T cell-autonomous histone

lactylation enhances their antitumor immunity. In head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma, H3K9la upregulates the expression of IL-11

in tumor cells. This tumor-derived IL-11 then induces

CD8+ T cell exhaustion via the JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway (73). A study using the

MB49 tumor model demonstrates that combination therapy with

anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and anti-cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antibodies markedly

elevates the H3K18la and H3K9la levels in tumor-infiltrating

CD8+ T cells, which is associated with marked tumor

growth inhibition (74).

In summary, histone lactylation, particularly

H3K18la, is a pivotal epigenetic mechanism that orchestrates the

immunosuppressive TME through multifaceted pathways including

immune cell reprogramming, stromal cell activation and therapy

resistance. Mechanistically, histone lactylation mediates

immunosuppression by polarizing myeloid cells toward an M2-like

phenotype, promoting CD8+ T cell exhaustion and

enhancing neutrophil-mediated immunosuppression. Additionally,

CD8+ T cell-intrinsic histone lactylation exhibits

context-dependent effects, potentiating antitumor activity when

induced by immune checkpoint blockades (Table II).

| Table II.Effects of histone lactylation on the

tumor microenvironment. |

Table II.

Effects of histone lactylation on the

tumor microenvironment.

| First author,

year | Type of cancer | Cell type | Lactylation

site | Downstream

targets | Associated

molecules or pathways | Effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Li et al,

2024 | CRC | TAMs | H3K18la | RARγ |

TRAF6/IL-6/STAT3 | Oncogenesis | (21) |

| Deng et al,

2025 | BLCA | TAMs | H3K18la | PRKN | Not mentioned | Mitophagy and M2

polarization | (63) |

| Li et al,

2024 | GBM | TAMs | H3K18la | TNFSF9 | Not mentioned | M2

polarization | (64) |

| Cai et al,

2025 | HCC | TAMs | H3K18la | NUPR1 | ERK and JNK

signaling pathways | M2

polarization | (65) |

| Yang et al,

2025 | PCA | TAMs | H3K18la | ACAT2 | Not mentioned | M2

polarization | (66) |

| Chaudagar et

al, 2023 | Prostate

cancer | TAMs | H3K18la | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Inhibition of

phagocytosis in TAMs | (67) |

| Xiong et al,

2022 | CRC | TIMs | H3K18la | METTL3 | JAK1/STAT3 | Tumor immune

evasion | (68) |

| Zhang et al,

2025 | Lung cancer | CAFs | H3K18la | Cthrc1 | TGF-β/Smad | Resistance to

EGFR-TKI | (70) |

| Zhou et al,

2023 | CRC | Neutrophils | H3K18la | CXCL1 and 5 | Not mentioned |

Immunosuppression | (71) |

| Ugolini et

al, 2025 | Brain tumor | TIMs | Not mentione2 | ARG1 | Not mentioned |

Immunosuppression | (72) |

| Wang et al,

2024 | HNSCC | CD8+ T

cells | H3K9la | IL-11 | JAK2/STAT3 | Dysfunction of

CD8+ T cells | (73) |

| Raychaudhuri et

al, 2024 | BLCA | CD8+ T

cells | H3K18la and

H3K9la | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Tumor

suppression | (74) |

Histone lactylation and chemoresistance

Emerging evidence demonstrates that this epigenetic

modification regulates chemotherapeutic responses through multiple

molecular mechanisms, which contributes to chemoresistance in

malignant tumors.

Modulation of cellular autophagy

pathways

Compared with bevacizumab-sensitive patients, the

histone lactylation level is markedly higher in

bevacizumab-resistant patients with CRC. In patient-derived tumor

xenograft models and patient-derived organoids, the combination of

bevacizumab and histone lactylation inhibitor (oxamate) relieves

the bevacizumab resistance in CRC. Mechanistically, H3K18la

activates the transcription of the autophagy-enhancing gene

rubicon-like autophagy enhancer (RUBCNL). RUBCNL interacts with

Beclin 1 to mediate the recruitment and function of the class III

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex, which promotes autophagosome

maturation (75).

Regulation of transcriptional activity

and activation of proliferation-associated signaling pathways

In BLCA, H3K18la promotes cisplatin resistance by

facilitating the transcriptional induction of Y-Box binding protein

1 and Yin Yang 1 transcription factor (76). In HCC, H3K18la exacerbates

resistance to lenvatinib by promoting the transcription of the HECT

domain E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HECTD2) gene. HECTD2

acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for Kelch-like ECH associated

protein 1 (KEAP1), facilitating the degradation of KEAP1 protein

and activating the antioxidant response, which induces lenvatinib

resistance in HCC cells (77).

H3K14la promotes multi-drug (oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil)

resistance through neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally

downregulated protein 4 E3 ubiquitin protein ligase-mediated

phosphatase and PTEN ubiquitination and degradation, which leads to

the subsequent activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in

HCC (78). However, the suppression

of histone lactylation enhances the sensitivity of cancer to

chemotherapy.

In GBM, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

activates the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, which in turn upregulates

acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (ACOX1). ACOX1 suppresses lactate-mediated

H3K18la by promoting ROS-dependent downregulation of PKM2, which

enhances the sensitivity of GBM to temozolomide (TMZ) (79). Transfer RNA-derived small RNA

(tsRNA)-08614 enhances the sensitivity of CRC to oxaliplatin by

targeting aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A3 (ALDH1A3) to

inhibit glycolysis and histone lactylation modifications.

Mechanistically, tsRNA-08614 downregulates the expression of

ALDH1A3, which reduces lactate production and decreases the level

of H3K18la. The decreased H3K18la level suppresses the

transcriptional activity of EF-hand domain family member D2, which

promotes the sensitivity of CRC to oxaliplatin (80).

Inhibition of ferroptosis

H4K12la in CRC stem cells suppresses ferroptosis

signaling by upregulating the expression of glutamate-cysteine

ligase, which enhances oxaliplatin resistance. This epigenetic

modification is dynamically regulated by p300-mediated lactylation

and histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1-mediated delactylation (81). Lactate derived from CAFs promotes

doxorubicin resistance in TNBC cells by enhancing the expression of

zinc finger protein 64 through H3K18la-mediated epigenetic

regulation, which suppresses ferroptosis (82).

Modulation of DNA damage repair

pathways

In lung cancer brain metastasis, aldo-keto reductase

family 1 member B10 enhances lactate accumulation. Lactate-induced

H4K12la transcriptionally activates the cell cycle gene cyclin B1,

which promotes DNA replication and cell cycle progression, inducing

an acquired resistance to pemetrexed (83). In ovarian cancer (OC), H4K12la

activates super-enhancers to recruit the oncogenic transcription

factor MYC, which upregulates the expression of the nucleotide

excision repair-related gene radiation sensitive protein (RAD)23

homolog A, nucleotide excision repair protein (84). Additionally, general control

non-depressible 5 (GCN5) promotes cisplatin resistance in OC by

upregulating H3K9la and RAD51 Kla to enhance homologous

recombination repair (85). H3K9la

promotes the transcription of LUC7-like 2, pre-mRNA splicing factor

(LUC7L2). However, in GBM, LUC7L2 downregulation reduces the

expression of MLH1, which suppresses mismatch repair and leads to

TMZ resistance (86).

In summary, histone lactylation acts as a crucial

mediator in chemoresistance across various types of cancer. It

promotes chemoresistance through multiple mechanisms, including

activation of autophagy-related pathways, modulation of

transcription factor activity, regulation of DNA repair,

interference with apoptosis, reprogramming of cellular metabolism

and stimulation of proliferation-related signaling pathways

(Table III).

| Table III.An overview of the effects of histone

lactylation on chemotherapy. |

Table III.

An overview of the effects of histone

lactylation on chemotherapy.

| First author,

year | Type of cancer | Drug | Lactylation

site | Downstream

targets | Effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Li et al,

2024 | CRC | Bevacizumab | H3K18la | RUBCNL | Autophagosome

maturation | (75) |

| Li et al,

2024 | BLCA | Cisplatin | H3K18la | YBX1 and YY1 | Reduction in the

sensitivity of tumor cells to cisplatin | (76) |

| Dong et al,

2025 | HCC | Lenvatinib | H3K18la | HECTD2 | Reduction in the

sensitivity of tumor cells to lenvatinib | (77) |

| Zeng et al,

2025 | HCC | Oxaliplatin and

5-fluorouracil | H3K14la | The ubiquitin E3

ligase NEDD4 | Activation of

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | (78) |

| Wang et al,

2025 | GBM | Temozolomide | H3K18la | Not mentioned | Reduction in the

sensitivity of tumor cells to temozolomide | (79) |

| Chen et al,

2025 | CRC | Oxaliplatin | H3K18la | EFHD2 | Reduction in the

sensitivity of tumor cells to oxaliplatin | (80) |

| Deng et al,

2025 | CRC | Oxaliplatin | H4K12la | Glutamate-cysteine

ligase | Reduction in the

sensitivity of tumor cells to oxaliplatin | (81) |

| Zhang et al,

2025 | TNBC | Doxorubicin | H3K18la | ZFP64 | Reduction in

ferroptosis | (82) |

| Duan et al,

2023 | Lung cancer | Pemetrexed | H4K12la | CCNB1 | Increases in DNA

replication and the acceleration of the cell cycle | (83) |

| Lu et al,

2025 | Ovarian cancer | Niraparib | H4K12la | Super-enhancer | Increases in DNA

damage repair | (84) |

| Sun et al,

2025 | Ovarian cancer | Cisplatin | H3K9la | Not mentioned | Increases in

homologous recombination repair | (85) |

| Yue et al,

2024 | GBM | Temozolomide | H3K9la | LUC7L2 | Reductions in

mismatch repair | (86) |

Histone lactylation and immune checkpoint

inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as CTLA-4 and

PD-1, function by blocking immune checkpoints to restore the

ability of the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells

(87). Notable clinical success is

demonstrated with checkpoint proteins such as PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4

in cancer treatment (88). Emerging

evidence reveals histone lactylation-mediated immune evasion

mechanisms across various types of cancer (Table IV). In non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC), H3K18la activates pore membrane protein 121 transcription,

which facilitates MYC nuclear translocation. This enhances MYC

binding to the CD274 promoter, which upregulates the expression of

PD-L1 and promotes immune evasion (89). In acute myeloid leukemia,

STAT5-induced lactate accumulation promotes E3 binding protein

nuclear translocation, which increases H4K5la levels. H4K15la

further elevates the expression of PD-L1, which establishes a

metabolic-epigenetic cascade linking lactate metabolism to immune

escape (90).

| Table IV.An overview of the effects of histone

lactylation on immunotherapy. |

Table IV.

An overview of the effects of histone

lactylation on immunotherapy.

| First author,

year | Type of cancer | Lactylation

site | Downstream

targets | Immune

checkpoint | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhang et al,

2024 | Non-small cell lung

cancer | H3K18la | Pore membrane

protein 121 | PD-L1 | (89) |

| Huang et al,

2023 | Acute myeloid

leukemia | H4K5la | PD-L1 | PD-L1 | (90) |

| Li et al,

2024 | Gastric cancer | H3K18la | PD-L1 | PD-L1 | (91) |

| Chao et al,

2024 | Ovarian cancer | H3K18la | PD-L1 | PD-L1 | (92) |

| Ding et al,

2025 | HCC | H3K18la | PD-L1 | PD-L1 | (94) |

| Ma et al,

2025 | HCC | H3K18la | CD276 | CD276 | (95) |

| Wang et al,

2024 | Glioblastoma | Not mentioned | CD47 | CD47 | (98) |

CAF-derived lysyl oxidase activates the

TGF-β/insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling pathway to promote the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and glycolysis in GC. The

resulting lactate accumulation enhances the H3K18la-mediated

expression of PD-L1 (91). Elevated

H3K18la levels are associated with poor prognosis in OC (92). LDHB, a subunit of lactate LDH,

facilitates immune evasion in OC by modulating H3K18la at the PD-L1

promoter to upregulate the expression of PD-L1 (93). Protein arginine methyltransferase 3

methylates pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 1 at residues R363

and R368, which enhances its kinase activity to promote glycolysis

and the accumulation of lactate. The resulting lactate induces

H3K18la, which directly binds to the PD-L1 promoter to upregulate

its expression, which promotes immune evasion in HCC (94). Histone lactylation modulates the

expression of PD-L1, which impairs the immune system recognition

and attack of cancer cells (91,93,94).

However, the role of histone lactylation in regulating CTLA-4

during cancer therapy is yet to be fully elucidated, which may be

an avenue for future investigation.

In addition to PD-L1 and CTLA-4, new immune

checkpoints, including B7 homologue 3 (B7-H3), are being

investigated (88). Lactate

upregulates the expression of B7-H3/CD276 in HCC cells via histone

lactylation modifications, particularly H3K18la, which suppresses

the proportion and function of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T

cells and promotes tumor immune escape. Inhibiting lactate

metabolism reduces the expression of B7-H3 and synergizes with

anti-PD-1 therapy, which markedly suppresses tumor progression

(95).

CD47 (integrin-associated protein) is expressed on

the surface of various cell types, including tumor cells. Its

ligand, signal-regulatory protein α (SIRPα), is primarily expressed

on immune cells such as macrophages. When CD47 binds to SIRPα, a

signal is transmitted to macrophages, which inhibits their

phagocytic activity against the tumor cells (96,97).

In GBM stem cells, histone lactylation promotes the expression of

CD47, which inhibits the phagocytic activity of

microglia/macrophages against tumor cells and facilitates tumor

immune escape. Histone lactylation also enhances the substrate

specificity of histone acetyltransferase p300 for lactyl-CoA

through its interaction with heterochromatin protein chromobox

homolog 3 (CBX3), which further promotes the expression of

immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13) (98).

In summary, histone lactylation serves as a critical

epigenetic regulatory mechanism mediating tumor immune evasion.

This modification orchestrates the expression levels of immune

checkpoint molecules through multiple pathways, impairing immune

cell recognition and cytotoxic functions against tumor cells, which

leads to immune escape. Elucidating the precise mechanisms of

histone lactylation in tumor immune evasion may provide a

theoretical foundation for identifying novel immunotherapy targets

and may also facilitate the rational design of combination

therapies.

Current research status and future

directions of histone lactylation in cancer diagnosis or

treatment

Histone lactylation has the potential

to serve as a biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis

The levels of histone lactylation modification show

marked differences in various types of cancer and may be a

potential diagnostic biomarker (57,99).

Combined with multi-omics analysis techniques, genes modified by

histone lactylation may also serve as novel biomarkers for

predicting the prognosis of cancer or evaluating therapeutic

efficacy (100).

The study by Hou et al (20) first reveals an association between

H3K18la and both severity and prognosis in PCA. The aforementioned

study demonstrates an elevated expression of H3K18la in PCA

tissues, which shows notable associations with serum lactate levels

as well as tumor markers such as carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and

carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). These findings indicate that

H3K18la may be a promising novel biomarker for PCA diagnosis and

prognostic evaluation. A study by Zhu et al (99) performs a comprehensive evaluation of

the clinical significance of H4K5la in BC. The aforementioned study

demonstrates elevated H4K5la levels across multiple sample types,

including TNBC tissues, non-TNBC tissues and peripheral blood

mononuclear cells. Furthermore, the authors identify positive

associations between the expression of H4K5la and tumor progression

markers such as proliferation index Ki-67, CEA levels and lymph

node metastasis status. However, higher H4K5la expression levels

show a negative association with overall survival time, suggesting

its potential as both a prognostic indicator and therapeutic

monitoring marker in BC management. The study by He et al

(101) uses an integrated analysis

of transcriptomic and single-cell RNA sequencing data to identify

five histone lactylation-related prognostic genes (synuclein α

interacting protein, transmembrane protein 100, NLR family pyrin

domain containing 11, homeobox C11 and D10) in GBM. Based on these

molecular signatures, the aforementioned study presents a risk

prediction model that demonstrates robust prognostic performance in

patients with GBM.

Potential therapeutic strategies

targeting histone lactylation

Inhibition of histone lactylation through

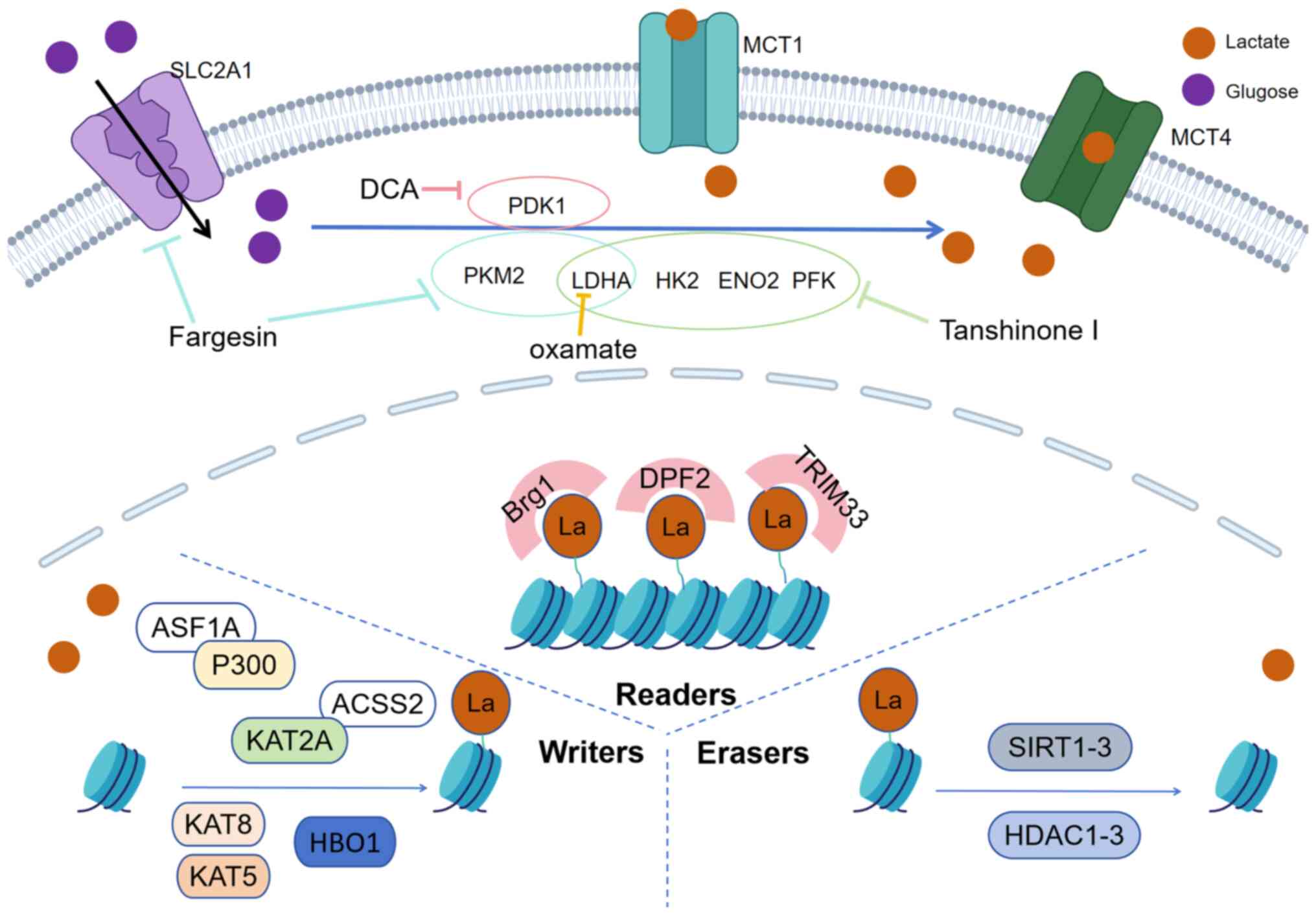

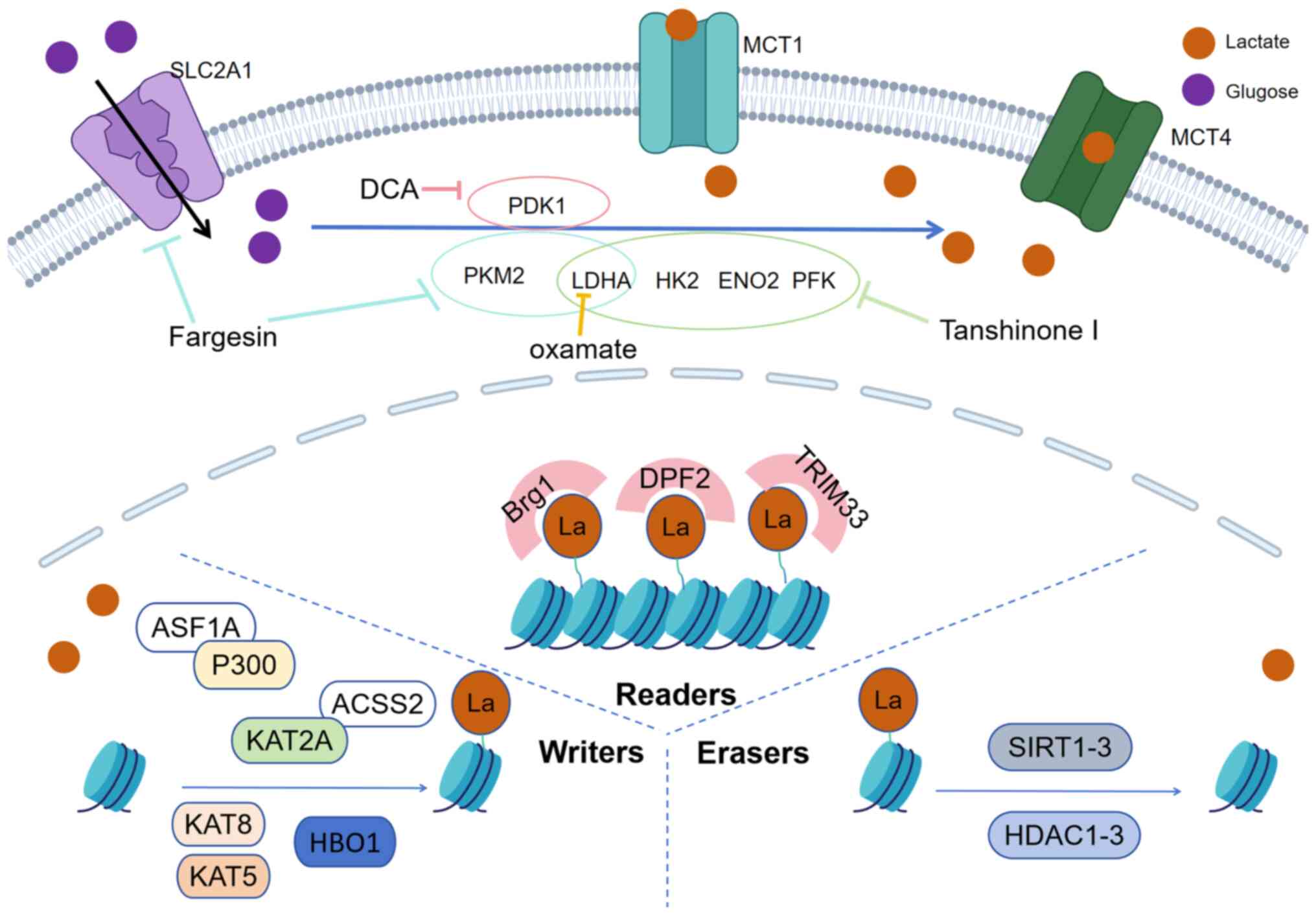

targeting lactate transportation and glycolysis

MCTs, particularly MCT1 and MCT4, are key lactate

transporters that maintain cellular metabolic balance. MCT1

mediates bidirectional lactate transport and MCT4 primarily

facilitates lactate efflux, especially in highly glycolytic cells

such as cancer cells and immune cells (102). The MCT1 inhibitor AZD3965 can

increase the accumulation of lactate (103). At present, AZD3965, as the

first-in-class drug targeting tumor lactate metabolism, has entered

phase I/II clinical trials for the treatment of diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma and neuroendocrine tumors (NCT01791595) (104). The effects of MCT1 inhibition on

histone lactylation exhibit notable cell-type specificity and

microenvironmental dependency (105).

Glycolysis, a central metabolic pathway that

converts glucose into pyruvate and lactate to generate ATP and key

intermediates, promotes lactate accumulation in cells with a

Warburg effect. This links cellular metabolic status to histone

lactylation modifications (106).

Inhibition of glycolysis-related genes reduces lactate production,

which decreases histone lactylation levels. LDHA inhibitors

suppress tumor growth and synergize with immunotherapy (107). A study by Guo et al

(23) demonstrates that Fargesin

inhibits aerobic glycolysis in NSCLC cell lines by targeting

glycolysis-related genes such as LDHA, solute carrier family 2

member 1, and PKM2. The aforementioned study also reveals that

Fargesin suppresses the lactylation of histone H3, which inhibits

the growth of NSCLC. Tanshinone I, a bioactive diterpenoid derived

from Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen), suppresses OC

progression by downregulating glycolysis-related genes and

subsequently reducing H3K18la levels (22). Additionally, administration of

sodium dichloroacetate, the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1

inhibitor, attenuates histone lactylation modifications (17).

Writers, erasers and readers of

histone lactylation

Histone lactylation is a dynamically regulated

process that is installed and removed by regulatory enzymes,

instead of being a spontaneous chemical reaction. It involves

‘writers’, ‘erasers’ and ‘readers’. These regulatory enzymes

regulate the dynamic balance of histone lactylation, which

influences gene expression levels and cellular functions (108–110).

The ‘writers’ refer to enzymes that add lactate

groups to lysine residues on histones. At present, known ‘writers’

for histone lactylation include acetyltransferase p300 (17,111),

GCN5 (also known as lysine acetyltransferase 2A), lysine

acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A) (81,112,113), histone acetyltransferase binding

to ORC1 (HBO1; also known as KAT7) (114), KAT5 and KAT8 (115). After histone lactylation was first

demonstrated in 2019, p300 emerged as a candidate ‘writer’

(17). Since identifying p300 as a

histone acetyltransferase, a key question is how it specifically

catalyzes histone lactylation without affecting histone

acetylation. In GBM, CBX3 enhances the specificity of p300 for

lactyl-CoA through their interaction, which specifically catalyzes

histone lactylation without affecting histone acetylation. This

promotes tumor progression (99).

In atherosclerosis, the histone chaperone protein anti-silencing

function 1A histone chaperone acts as a cofactor for p300, and

regulates the enrichment of H3K18la at the snail family

transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1) promoter region to activate the

transcription of SNAI. This in turn induces the

endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and the use of the p300

agonist cholera toxin B markedly enhances H3K18la levels (116).

A study by Niu et al (114) demonstrates that HBO1 functions as

a lactyltransferase that preferentially catalyzes H3K9la to enhance

malignant behaviors, including proliferation, migration and

invasion in various cancer cell lines [including HeLa, HepG2 (HCC),

U87MG (gliomas), KYSE-30 (ESCC), MDA-MB-231 (BC), HCT116 (CRC) and

H460 (NSCLC)]. In GBM, it is KAT2A, instead of p300, that is the

‘writer’ and it promotes endothelial growth factor-induced H3K14la

and H3K18la. In addition, acyl-CoA synthetase short chain family

member 2 (ACSS2) binds to KAT2A, which then acts as a

lactyltransferase to catalyze the lactylation of histone H3 at K14

and K18 residues. This regulates gene expression levels and

promotes the proliferation and immune evasion of GBM cells. KAT2A

carried out distinct histone acylation in different protein

complexes and the interaction between ACSS2 and KAT2A promotes the

catalytic activity of KAT2A toward histone lactylation instead of

acetylation (113). A study by Zou

et al (115) demonstrates

that KAT5 and KAT8 function synergistically as ‘writers’ to mediate

lactate-induced H4K12la in macrophages. The aforementioned study

demonstrates that H4K12la is not influenced by other ‘writers’,

such as p300 and KAT2A.

‘Erasers’ are enzymes that remove lactylation

modifications from histones. Previous studies indicate that a

number of deacetylases, such as HDAC1-3 and SIRT1-3, act as

‘erasers’ to remove lactyl modifications (109,110,117–120). A study by Moreno-Yruela et

al (110) reports that HDAC1-3

function as ‘erasers’ to remove histone lactylation modifications.

At the H3K9 and H4K12 sites, HDAC3 has greater delactylation

activity compared with its deacetylation activity. Additionally,

HDAC1 and HDAC3, but not HDAC2, appear to preferentially regulate

H4K5la. A study by Xu et al (121) demonstrates that HDAC2 and HDAC3

function as ‘erasers’ for H3 Kla, participating in the regulation

of H3K18la-mediated BC cell proliferation. However, the

aforementioned study, reveals that HDAC1 levels show no association

with H3K18la. SIRT1 acts as a histone delactylase, inhibiting the

oncogenic positive feedback loop of long non-coding RNA

H19-glycolysis-H3K18la. Moreover, the combined use of the

SIRT1-specific activator SRT2104 and the LDHA inhibitor oxamate

markedly suppresses the growth of GC cells, with limited effects on

normal GC cells; thus, potentially providing a novel strategy for

GC treatment (122). A study by

Yang et al (62) also

demonstrates that SIRT2 and p300/CBP act as the ‘eraser’ and

‘writer’ of H4K5la, respectively, to regulate the metastatic

phenotype of NB cells. In a study on esophageal cancer, SIRT3 is

found to act as a specific ‘eraser’ of H3K9la, which inhibits the

progression of ESCC cells (123).

In addition, a study by Fan et al (109) suggests that SIRT3 also acts as an

‘eraser’ for H4K16la. The development of small-molecule modulators

targeting erasers may potentially be useful in cancer therapy.

‘Readers’ are proteins that recognize and bind to

lactylated histones, regulating gene expression levels and other

cellular processes, such as chromatin remodeling and accessibility

regulation, cell survival and tumorigenesis, and gene transcription

program regulation. Known histone lactylation ‘readers’ include

brahma-related gene 1 (Brg1) (108), double plant homeodomain finger 2

(DPF2) (124) and tripartite motif

containing 33 (TRIM33) (125). In

2024, the study by Hu et al (108) first reports that Brg1 interacts

with H3K18la and functions as a ‘reader’ of H3K18la and is

potentially involved in facilitating the accessibility of chromatin

regions-thereby promoting an open chromatin state and enhancing

gene expression. DPF2 recognizes H3K14la and binds to it through

its DPF domain, which modulates gene transcription and cell

survival. In cervical cancer, the accumulation of lactate leads to

increased levels of H3K14la, and DPF2 promotes the expression of

oncogenes by recognizing H3K14la, which promotes tumorigenesis

(124). The bromodomain of TRIM33

specifically recognizes Kla on histones. It is demonstrated that

the bromodomain of TRIM33 selectively binds to Kla via a unique

glutamic acid residue (E981), establishing it as a Kla-specific

‘reader’ protein (125). However,

a previous study, focusing on H3K18la as the primary subject of

investigation, did not demonstrate direct evidence regarding

whether TRIM33 functions as a ‘reader’ at other histone sites

(125).

In summary, the primary strategies for targeting

histone lactylation include: i) Modulation of lactate transport;

ii) regulation of lactate production; and iii) inhibition or

activation of enzymes mediating histone lactylation modifications.

The present evidence regarding the ‘readers’, ‘erasers’ and

‘writers’ of histone lactylation is yet to be fully elucidated.

Further identification and validation of specific targets are

required to enhance therapeutic precision. Moreover, there may be a

potential for the development of small-molecule inhibitors and

activators targeting these regulatory proteins (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1.Potential therapeutic strategies

targeting histone lactylation. Key strategies to modulate histone

lactylation include: i) Downregulating lactate flux (via MCT1/4

inhibition); ii) inhibition of the expression of glycolytic genes

(such as HK2, LDHA, ENO2, PFK, PKM2, PDK1 and

SLC2A1); iii) blocking lactylation-recognizing ‘readers’

(e.g., Brg1, DPF2, TRIM33) and modifying ‘writers’ (e.g., P300,

KAT2A, KAT5, KAT8, HBO1); and iv) enhancing the enzymatic activity

of ‘erasers’ (e.g., SIRT1-3, HDAC1-3). ‘T’ shaped arrows denote the

inhibitions of the pathways. DCA, sodium dichloroacetate; SLC2A1,

solute carrier family 2 member 1; MCT1, monocarboxylate transporter

1; MCT4, monocarboxylate transporter 4; HK2, hexokinase 2; LDHA,

lactate dehydrogenase; ENO2, enolase 2; PFK, phosphofructokinase;

PKM2, pyruvate kinase isozyme type M2; PDK1, pyruvate dehydrogenase

kinase 1; HBO1, home box office 1; La, lactate; Brg1,

brahma-related gene 1; DPF2, double PHD fingers 2; TRIM33,

tripartite motif containing 33; ASF1A, anti-silencing function 1A

histone chaperone; P300, E1A-binding protein; ACSS2, acyl-CoA

synthetase short chain family member 2; KAT, lysine

acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; SIRT, sirtuin. |

Conclusions and research perspectives

Histone lactylation is an epigenetic modification

that links cellular metabolism with gene regulation, serving a role

in cancer initiation, progression, metastasis, drug resistance and

immune evasion. The present review highlighted several key

findings. Histone lactylation, particularly at H3K18la, regulates

oncogenic pathways and metabolic reprogramming. Other lactylation

sites (such as H4K12la, H3K9la and H4K5la) contribute to

tumorigenesis in a context-dependent manner, influencing apoptosis

suppression, immune evasion and therapy resistance.

Hypoxia and mitochondrial dysfunction often lead to

the accumulation of lactic acid within cells. By acting as a

metabolic ‘gatekeeper’ controlling lactate metabolism,

mitochondrial targets serve as upstream regulators of histone

lactylation. At present, it is indicated that SIRT4 enhances

histone lactylation by promoting a metabolic shift from

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, which

increases lactate accumulation (52). When the Numb/Parkin axis is

impaired, the accumulation of damaged mitochondria triggers

metabolic reprogramming toward aerobic glycolysis, which leads to

lactate accumulation and the promotion of histone lactylation

(55). In addition, histone

lactylation can also influence mitochondrial function, which

affects intracellular lactate accumulation and forms a positive

feedback loop. H3K18la disrupts mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation by promoting the transcriptional activation of

ACAT2, exacerbates lactate accumulation and forms a protumorigenic

positive feedback loop (66). In

Alzheimer's disease, the shift from oxidative phosphorylation to

glycolysis in microglia promotes proinflammatory activation. During

this process, the glycolysis/H4K12la/PKM2 positive feedback loop

exacerbates microglial dysfunction (126).

In the context of cancer, targeting mitochondria

with regards to histone lactylation is yet to be fully elucidated.

However, understanding its implications in non-cancer contexts

(such as inflammation and hypoxic pulmonary hypertension) may be

significant (127,128). In the context of inflammation,

mitochondrial fragmentation promotes a metabolic shift that

increases lactate, which in turn promotes histone lactylation,

enhancing macrophage phagocytosis and inflammation resolution

(127). Hypoxia-induced

mitochondrial ROS stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)

via inhibition of its hydroxylation, which upregulates pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinase 1/2 to promote glycolytic switching and

lactate accumulation in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells

(PASMCs). H3K18la, induced by accumulated lactate, activates HIF-1α

target genes, which facilitates PASMC proliferation and vascular

remodeling (128). Selenium

deficiency induces mitochondrial dysfunction via the ROS/HIF-1α

pathway, leading to enhanced glycolysis and lactate production. The

accumulated lactate promotes H3K18la, which activates the NLRP3

inflammasome promoter and induces pyroptosis and the release of

inflammatory factors (including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ) (129). Methyltransferase-like 15

deficiency impairs mitochondrial ribosome function, leading to

reduced oxidative phosphorylation, increased ROS and diminished

membrane potential. This promotes enhanced glycolysis and lactate

secretion, and leads to a notable increase in histone lactylation

at the H4K12 and H3K9 sites (130). In summary, mitochondrial

dysfunction is a key regulator of histone lactylation, primarily

through its impact on glycolysis and intracellular lactate levels.

Enhanced glycolysis fuels lactate production, which in turn

promotes histone lactylation by substrate provision. This

establishes a key mechanistic link through which mitochondrial

dysfunction influences histone lactylation (34,118,126,131).

The present review highlighted that histone PTMs do

not function in isolation. A key emerging concept is the cascading

interplay between lactylation and other PTMs, which regulate

oncogenic programs. For example, in HCC, H3K18la upregulates the

expression of YTHDC1, stabilizes NEAT1 RNA and recruits p300 to the

SCD gene promoter. This subsequently promotes H3K27ac, forming a

cascade of epigenetic modifications that promotes tumor progression

by activating fatty acid metabolic reprogramming (45). This ‘lactylation-acetylation axis’

links lactate metabolism to lipid metabolic reprogramming and tumor

progression. In addition to acetylation, the potential crosstalk

between lactylation and lysine methylation warrants further

investigation. A study by Yang et al (132) reveals that H3K18la upregulates the

expression of suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12), which enhances the

level of trimethylated histone H3 at K27 (H3K27me3). Subsequently,

SUZ12/H3K27me3 inhibits the transcription of Krüppel-like factor 4

(KLF4). The downregulation of KLF4 relieves its inhibitory effect

on LDHA, a key enzyme in glycolysis, leading to lactate production.

In turn, the accumulated lactate further promotes histone

lactylation, thus forming a self-amplifying positive feedback loop

that promotes the Warburg effect and malignant progression of

retinoblastoma. Elucidating these cascading interactions may be

important to understand the full scope of histone lactylation in

cancer and may contribute to clinical translation strategies from

single target to ‘PTM cascade’ targeting therapies.

Lactate-induced H3K18la in TAMs and myeloid cells

promotes an immunosuppressive TME via PD-L1 upregulation, M2

polarization and CD8+ T cell exhaustion. However,

CD8+ T cell-intrinsic lactylation may enhance antitumor

immunity after induction by immune checkpoint blockade, which

suggests a dual role in immunotherapy. Histone lactylation promotes

resistance to chemotherapy such as oxaliplatin, cisplatin,

lenvatinib and targeted therapies through autophagy activation, DNA

repair enhancement and ferroptosis suppression.

Lactylation-mediated immune checkpoint upregulation (such as via

PD-L1, CD47 and B7-H3) contributes to immunotherapy resistance,

which highlights the potential of combination strategies.

However, despite notable progress in associated

research, numerous questions are yet to be investigated. At

present, a hypothesis regarding the process of histone lactylation

is that lactate condenses with CoA within the cell to form lac-CoA.

Lac-CoA is then acted upon by a ‘writer’, which transfers the

lactyl group to lysine residues. Subsequently, the lactylated

histones are recognized by a ‘reader’, leading to changes in the

transcription levels of downstream genes. Finally, after the

modification is complete, an ‘eraser’ recognizes and removes the

lactyl group from the lysine residues, restoring the normal

chromatin structure (19). Previous

studies demonstrate direct experimental evidence for non-enzymatic

histone lactylation. Non-enzymatic Kla is experimentally

demonstrated on glycolytic enzymes in vitro (45,133).

The study by Zhang et al (17) provides evidence for its occurrence

on histones and demonstrate the modification after incubating

histones with sodium lactate in the absence of enzymes.

Subsequently, the study by Tan et al (134) demonstrates that lactoyl-CoA and

lactoylglutathione are the direct inducers of this spontaneous

reaction. It is hypothesized that in cellular environments with

high lactate and low pH (such as the TME), lactate accumulation may

promote histone lactylation through similar non-enzymatic

mechanisms (133,135,136). However, at present, it is

challenging for the majority of cellular studies to delineate

whether lactylation at a specific site arises from enzymatic

catalysis or non-enzymatic mechanisms, which is a notable

limitation in the field. Therefore, non-enzymatic modification

should be considered as a potential confounding factor when

interpreting associated physiological or pathological data. Future

studies should aim to resolve this by developing site-specific

probes or constructing enzyme-deficient models.

At present, multiple ‘writers’ of histone

lactylation (such as P300, GCN5, HBO1, KAT5 and KAT8) and ‘erasers’

(such as HDAC1-3 and SIRT1-3) are identified. Previous studies

suggest that HBO1 preferentially catalyzes H3K9la. Furthermore,

compared with HDAC2, HDAC1 and 3 more preferentially regulate

H4K5la. These findings indicate that future studies on histone

lactylation should select appropriate regulatory enzymes based on

specific sites. However, at present, studies on regulatory enzymes

for histone lactylation are limited. Therefore, further studies are

needed to provide evidence regarding whether these enzymes

specifically or preferentially regulate lactylation at particular

histone sites. In addition, the specific functions and mechanisms

of these enzymes in different types of cancer are yet to be fully

elucidated.

Additionally, studies on the ‘readers’ of histone

lactylation is limited, and their functions and regulatory

mechanisms in cancer still requires thorough investigation. Due to

the high degree of conservation and acetyl-lysine specificity of

bromodomain modules, and the structural, functional and

evolutionary parallels between histone lactylation and acetylation,

it is hypothesized that bromodomain-containing proteins may

function as ‘readers’ of histone lactylation (108,125). It is suggested that future studies

further identify and validate the specific targets of these enzymes

and possibly develop small-molecule inhibitors or modulators

targeting them to potentially achieve more precise cancer

therapy.

At present, the majority of studies are still in

the basic research stage, and further translational research is

required to verify the safety and efficacy of histone

lactylation-targeting therapeutic strategies in cancer. Histone

lactylation represents a dynamic link between metabolism and

epigenetics and may potentially offer novel insights into cancer

biology and therapy. Future studies may potentially investigate the

enzymatic regulation and functional outcomes of lactylation,

develop lactylation-targeted drugs and rational combinations, and

validate lactylation as a biomarker and therapeutic target in

clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Scientific Research

Foundation of Jilin province (grant no. 20240402001GH) and the

National Nature and Science Foundation of China (grant no.

82372690).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZJ and PG conceived and designed the present study.

ZJ, SL and ZW drafted the initial manuscript. ZJ prepared the

figures and tables. PG revised figures, tables and manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ACAT2

|

acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2

|

|

ACOX1

|

acyl-CoA oxidase 1

|

|

ACSS2

|

acyl-CoA synthetase short chain

family member 2

|

|

ALDH1A3

|

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family

member A3

|

|

BC

|

breast cancer BLCA, bladder

cancer

|

|

B7-H3

|

B7 homologue 3

|

|

Brg1

|

brahma-related gene 1

|

|

CEA

|

carcinoembryonic antigen

|

|

CRLM

|

colorectal cancer liver

metastasis

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

CAFs

|

cancer-associated fibroblasts

|

|

CXCL

|

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand

|

|

CBX3

|

chromobox homolog 3

|

|

CTHRC1

|

collagen triple helix

repeat-containing 1

|

|

DNAJC12

|

DnaJ heat shock protein family

(Hsp40) member C12

|

|

DPF2

|

double plant homeodomain finger 2

|

|

ESCC

|

esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma

|

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma

|

|

GCN5

|

general control non-depressible 5

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

H3K27ac

|

histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation

|

|

H3K18la

|

histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation

|

|

HECTD2

|

HECT domain E3 ubiquitin protein

ligase 2

|

|

HDAC

|

histone deacetylase

|

|

IRS1

|

insulin receptor substrate 1

|

|

Kla

|

lysine lactylation

|

|

KEAP1

|

Kelch-like ECH associated protein

1

|

|

KAT2A

|

lysine acetyltransferase 2A

|

|

LDH

|

lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

LAMC2

|

laminin subunit γ 2

|

|

MCTs

|

monocarboxylate transporters

|

|

NEAT1

|

nuclear paraspeckle assembly

transcript 1

|

|

NB

|

neuroblastoma

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

NUPR1

|

nuclear protein 1

|

|

OC

|

ovarian cancer

|

|

PTMs

|

post-translational modifications

|

|

PYCR1

|

pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase

1

|

|

PCA

|

pancreatic cancer

|

|

PKM2

|

pyruvate kinase M2

|

|

RUBCNL

|

rubicon-like autophagy enhancer

|

|

SCD

|

stearoyl-CoA desaturase

|

|

SLFN5

|

Schlafen 5

|

|

SIRT

|

sirtuin

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

TNBC

|

triple-negative breast cancer

|

|

TAMs

|

tumor-associated macrophages

|

|

TMZ

|

temozolomide

|

|

TRIM33

|

tripartite motif containing 33

|

|

USP

|

ubiquitin-specific peptidase

|

|

YTHDF2

|

YTH N6-methyladenosine

RNA-binding protein F2

|

References

|

1

|

Zhong Q, Xiao X, Qiu Y, Xu Z, Chen C,

Chong B, Zhao X, Hai S, Li S, An Z and Dai L: Protein

posttranslational modifications in health and diseases: Functions,

regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. MedComm

(2020). 4:e2612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lee JM, Hammaren HM, Savitski MM and Baek

SH: Control of protein stability by Post-translational

modifications. Nat Commun. 14:2012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shu F, Xiao H, Li QN, Ren XS, Liu ZG, Hu

BW, Wang HS, Wang H and Jiang GM: Epigenetic and Post-translational

modifications in autophagy: Biological functions and therapeutic

targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li Z, Chen J, Huang H, Zhan Q, Wang F,

Chen Z, Lu X and Sun G: Post-translational modifications in

diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e181582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Winston DJ, Pakrasi A and Busuttil RW:

Prophylactic fluconazole in liver transplant recipients. A

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med.

131:729–737. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Durrant JD, de Oliveira CA and McCammon

JA: POVME: An algorithm for measuring Binding-pocket volumes. J Mol

Graph Model. 29:773–776. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Silman I, Roth E, Paz A, Triquigneaux MM,

Ehrenshaft M, Xu Y, Shnyrov VL, Sussman JL, Deterding LJ, Ashani Y,

et al: The specific interaction of the photosensitizer methylene

blue with acetylcholinesterase provides a model system for studying

the molecular consequences of photodynamic therapy. Chem Biol

Interact. 203:63–66. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hanson G and Coller J: Codon optimality,

bias and usage in translation and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 19:20–30. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jenuwein T and Allis CD: Translating the

histone code. Science. 293:1074–1080. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mansour MR, Abraham BJ, Anders L,

Berezovskaya A, Gutierrez A, Durbin AD, Etchin J, Lawton L, Sallan

SE, Silverman LB, et al: Oncogene regulation. An oncogenic

super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding

intergenic element. Science. 346:1373–1377. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu XY, Guo CH, Xi ZY, Xu XQ, Zhao QY, Li

LS and Wang Y: Histone methylation in pancreatic cancer and its

clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 27:6004–6024. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Komar D and Juszczynski P: Rebelled

epigenome: Histone H3S10 phosphorylation and H3S10 kinases in

cancer biology and therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 12:1472020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tamburri S, Conway E and Pasini D:

Polycomb-dependent histone H2A ubiquitination links developmental

disorders with cancer. Trends Genet. 38:333–352. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Duan X, Xing Z, Qiao L, Qin S, Zhao X,

Gong Y and Li X: The role of histone post-translational

modifications in cancer and cancer immunity: Functions, mechanisms

and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 15:14952212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y,

Zou Y, Wang JX, Wang Z and Yu T: Lactate metabolism in human health

and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:3052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhao Y and Hong J: Purification of

recombinant histones and mononucleosome assembly. Curr Protoc.

5:e701552025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hu Y, He Z, Li Z, Wang Y, Wu N, Sun H,

Zhou Z, Hu Q and Cong X: Lactylation: The novel histone

modification influence on gene expression, protein function, and

disease. Clin Epigenetics. 16:722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yu X, Yang J, Xu J, Pan H, Wang W, Yu X

and Shi S: Histone lactylation: From tumor lactate metabolism to

epigenetic regulation. Int J Biol Sci. 20:1833–1854. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hou J, Guo M, Li Y and Liao Y: Lactylated

histone H3K18 as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and

prediction of the severity of pancreatic cancer. Clinics (Sao

Paulo). 80:1005442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li XM, Yang Y, Jiang FQ, Hu G, Wan S, Yan

WY, He XS, Xiao F, Yang XM, Guo X, et al: Histone lactylation

inhibits RARgamma expression in macrophages to promote colorectal

tumorigenesis through activation of TRAF6-IL-6-STAT3 signaling.

Cell Rep. 43:1136882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jin Z, Yun L and Cheng P: Tanshinone I

reprograms glycolysis metabolism to regulate histone H3 lysine 18

lactylation (H3K18la) and inhibits cancer cell growth in ovarian

cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 291:1390722025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Guo Z, Tang Y, Wang S, Huang Y, Chi Q, Xu

K and Xue L: Natural product fargesin interferes with H3 histone

lactylation via targeting PKM2 to inhibit non-small cell lung

cancer tumorigenesis. Biofactors. 50:592–607. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rabinowitz JD and Enerback S: Lactate: The

ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metabo. 2:566–571. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen S, Xu Y, Zhuo W and Zhang L: The

emerging role of lactate in tumor microenvironment and its clinical

relevance. Cancer Lett. 590:2168372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gatenby RA and Gillies RJ: Why do cancers

have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 4:891–899. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Brooks GA, Osmond AD, Arevalo JA, Duong

JJ, Curl CC, Moreno-Santillan DD and Leija RG: Lactate as a myokine

and exerkine: Drivers and signals of physiology and metabolism. J

Appl Physiol (1985). 134:529–548. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fang Y, Li Z, Yang L, Li W, Wang Y, Kong

Z, Miao J, Chen Y, Bian Y and Zeng L: Emerging roles of lactate in

acute and chronic inflammation. Cell Commun Signal. 22:2762024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chang X, Zhou S, Liu J, Wang Y, Guan X, Wu

Q, Liu Z and Liu R: Zishenhuoxue decoction-induced myocardial

protection against ischemic injury through TMBIM6-VDAC1-mediated

regulation of calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial quality

surveillance. Phytomedicine. 132:1553312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chang X, Zhang Q, Huang Y, Liu J, Wang Y,

Guan X, Wu Q, Liu Z and Liu R: Quercetin inhibits necroptosis in

cardiomyocytes after ischemia-reperfusion via

DNA-PKcs-SIRT5-orchestrated mitochondrial quality control.

Phytother Res. 38:2496–2517. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nedel WL and Portela LV: Lactate levels in

sepsis: Don't forget the mitochondria. Intensive Care Med.

50:1202–1203. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Paul S, Ghosh S and Kumar S: Tumor

glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer

Biol. 86:1216–1230. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pandkar MR, Sinha S, Samaiya A and Shukla

S: Oncometabolite lactate enhances breast cancer progression by

orchestrating histone lactylation-dependent c-Myc expression.

Transl Oncol. 37:1017582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ma F and Yu W: The roles of lactate and

lactylation in diseases related to mitochondrial dysfunction. Int J

Mol Sci. 26:71492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang Y and Patti GJ: The Warburg effect: A

signature of mitochondrial overload. Trends Cell Biol.

33:1014–1020. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shechter D, Dormann HL, Allis CD and Hake

SB: Extraction, purification and analysis of histones. Nat Protoc.

2:1445–1457. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Doenecke D, Albig W, Bode C, Drabent B,

Franke K, Gavenis K and Witt O: Histones: Genetic diversity and

Tissue-specific gene expression. Histochem Cell Biol. 107:1–10.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Crane-Robinson C: Linker histones: History

and current perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1859:431–435. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xu K, Zhang K, Wang Y and Gu Y:

Comprehensive review of histone lactylation: Structure, function,

and therapeutic targets. Biochem Pharmacol. 225:1163312024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li H, Sun L, Gao P and Hu H: Lactylation

in cancer: Current understanding and challenges. Cancer Cell.

42:1803–1807. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI