Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks third among the most

prevalent diseases and is the second deadliest malignant disease

globally (1,2). In 2020, there were ~1.9 million newly

reported cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) globally, with

>900,000 deaths attributed to CRC (3). Key factors contributing to its high

mortality include challenges in early diagnosis, tumor

heterogeneity and the ineffectiveness of late-stage treatments

(4–6). Tumor heterogeneity encompasses both

cellular heterogeneity within the tumor and heterogeneity of the

tumor microenvironment (7,8). A growing body of research indicates

that the heterogeneity of CRC is among the most notable in

malignant tumors and exerts a profound influence on the prognosis

and treatment of the disease (5,9,10).

Moreover, previous studies leveraging bioinformatics analysis for

molecular classification and prognostic prediction of CRC have

emerged, indicating its considerable clinical promise (11–13).

However, due to its heterogeneity, CRC progression is a

multifactorial, multistage and dynamic process, which imposes

certain limitations on existing models. Consequently, it is

imperative to explore novel molecular subtypes and models of CRC

for prognostic evaluation.

Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1

(TIMP1), a member of the TIMP gene family, has been reported to

inhibit matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity (14). The TIMP1 gene is situated on human

chromosome Xp11.1-p11.4 and its mRNA codes for a protein composed

of 184 amino acids, exhibiting a molecular mass of 29–34 kDa

(15). Accumulating evidence

indicates that it interacts with several molecules to regulate

biological processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis and

differentiation, and it is implicated in the pathological

mechanisms of several diseases, particularly cancer (16,17). A

total of >35 independent clinical studies have reported that

high TIMP1 expression is positively associated with poor prognosis

across several cancer types, including lung, brain, prostate,

breast and colon cancer (14).

Moreover, the levels of TIMP1 are elevated in advanced-stage tumors

(14). Tian et al (18) reported that pancreatic cancer

cell-derived TIMP1 activates CD63/PI3K/AKT signaling to promote

perineural invasion by stimulating Schwann cells. Moreover, TIMP1

loss has been reported to alter the senescence-associated secretory

phenotype of senescent tumor cells and enhance prostate cancer

metastasis via MMP activation (19). However, the role of TIMP1 in CRC

remains poorly understood. Therefore, the present study aimed to

explore the clinical and prognostic significance of TIMP1 in

CRC.

Materials and methods

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

TCGA database (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) was the primary resource

for acquiring CRC mRNA expression data and clinical information.

The present study analyzed multi-omics patient data, which were

systematically organized across multiple databases, including the

original TCGA datasets (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Subsequent databases,

such as the University of Alabama at Birmingham CANcer data

analysis Portal (UALCAN) (20,21)

and Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA)

(22), provided comprehensive

insights into several aspects. The patient records from each

database were specifically utilized for diverse analyses.

Gene expression data processing

The UALCAN database (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) (20,21)

was used to analyze TIMP1 mRNA expression levels in pan-cancer and

in colon cancer samples (primary tumor, n=286; normal, n=41).

GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#general) (21) was used to assess TIMP1 expression in

TCGA tumors by matching TCGA normal and Genotype-Tissue Expression

project data for CRC (tumor, n=275; normal, n=349). The GSE24550

dataset was used to analyze TIMP1 mRNA expression levels in CRC

tissues (G2, n=77) and normal tissues (G1, n=13) (23). In addition, the Clinical Proteomic

Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) database within UALCAN was used

to evaluate TIMP1 protein expression in CRC (normal, n=100; primary

tumor, n=97).

CRC clinical pathological

parameters

STAR-counts data and the corresponding clinical

information for CRC tumors were downloaded from TCGA database

(24). The data in transcripts per

million (TPM) format were extracted and normalized using

log2(TPM+1) transformation. Following filtering of the

samples with both RNA sequencing (RNAseq) and clinical data, CRC

samples with high TIMP1 expression (top 25%, n=156) and low TIMP1

expression (top 25%, n=157) were selected for analysis (Table I). Statistical analysis was

performed using R software (version v4.0.3; The R Foundation).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

| Table I.Tissue inhibitor of matrix

metalloproteinase 1 expression and clinical features in 313 samples

from patients with colorectal cancer. |

Table I.

Tissue inhibitor of matrix

metalloproteinase 1 expression and clinical features in 313 samples

from patients with colorectal cancer.

|

| TIMP1 expression

level |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | High (n=156) | Low (n=157) | P-value |

|---|

| Status, n |

|

| 0.0019 |

|

Alive | 109 (34.8) | 133 (42.5) |

|

|

Dead | 47 (15.0) | 24 (7.7) |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

| Mean ±

SD | 66.7±12.8 | 64.9±13.4 | 0.4630 |

| Median

(min, max) | 68 (31, 90) | 66 (31, 90) | 0.2150 |

| Sex, n |

|

| 0.4978 |

|

Female | 77 (24.6) | 71 (22.7) |

|

|

Male | 79 (25.2) | 86 (27.5) |

|

|

Ethnicitya |

|

| 0.0404 |

|

American Indian | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

Asian | 4 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) |

|

|

Black | 12 (3.8) | 25 (8.0) |

|

|

White | 89 (28.4) | 69 (22.0) |

|

| pT

stagea |

|

| 0.1457 |

| T1 | 6 (1.9) | 6 (1.9) |

|

| T2 | 14 (4.5) | 26 (8.3) |

|

| T3 | 107 (34.2) | 109 (34.8) |

|

| T4 | 13 (4.2) | 9 (2.9) |

|

|

T4a | 12 (3.8) | 4 (1.3) |

|

|

T4b | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) |

|

|

Tis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

|

| pN

stagea |

|

| 0.1345 |

| N0 | 85 (27.2) | 103 (32.9) |

|

| N1 | 23 (7.3) | 22 (7.0) |

|

|

N1a | 6 (1.9) | 5 (1.6) |

|

|

N1b | 7 (2.2) | 2 (0.6) |

|

|

N1c | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

|

| N2 | 18 (5.8) | 19 (6.1) |

|

|

N2a | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) |

|

|

N2b | 11 (3.5) | 2 (0.6) |

|

| NX | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| pM

stagea |

|

| 0.1457 |

| M0 | 116 (37.1) | 114 (36.4) |

|

| M1 | 16 (5.1) | 17 (5.4) |

|

|

M1a | 6 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) |

|

| MX | 14 (4.5) | 22 (7.0) |

|

| pTNM

stagea |

|

| 0.2748 |

| I | 15 (4.8) | 27 (8.6) |

|

| II | 10 (3.2) | 9 (2.9) |

|

|

IIA | 56 (17.9) | 51 (16.3) |

|

|

IIB | 2 (0.6) | 7 (2.2) |

|

|

III | 2 (0.6) | 6 (1.9) |

|

|

IIIA | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) |

|

|

IIIB | 22 (7.0) | 19 (6.1) |

|

|

IIIC | 15 (4.8) | 12 (3.8) |

|

| IV | 15 (4.8) | 14 (4.5) |

|

|

IVA | 7 (2.2) | 4 (1.3) |

|

| IA | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

|

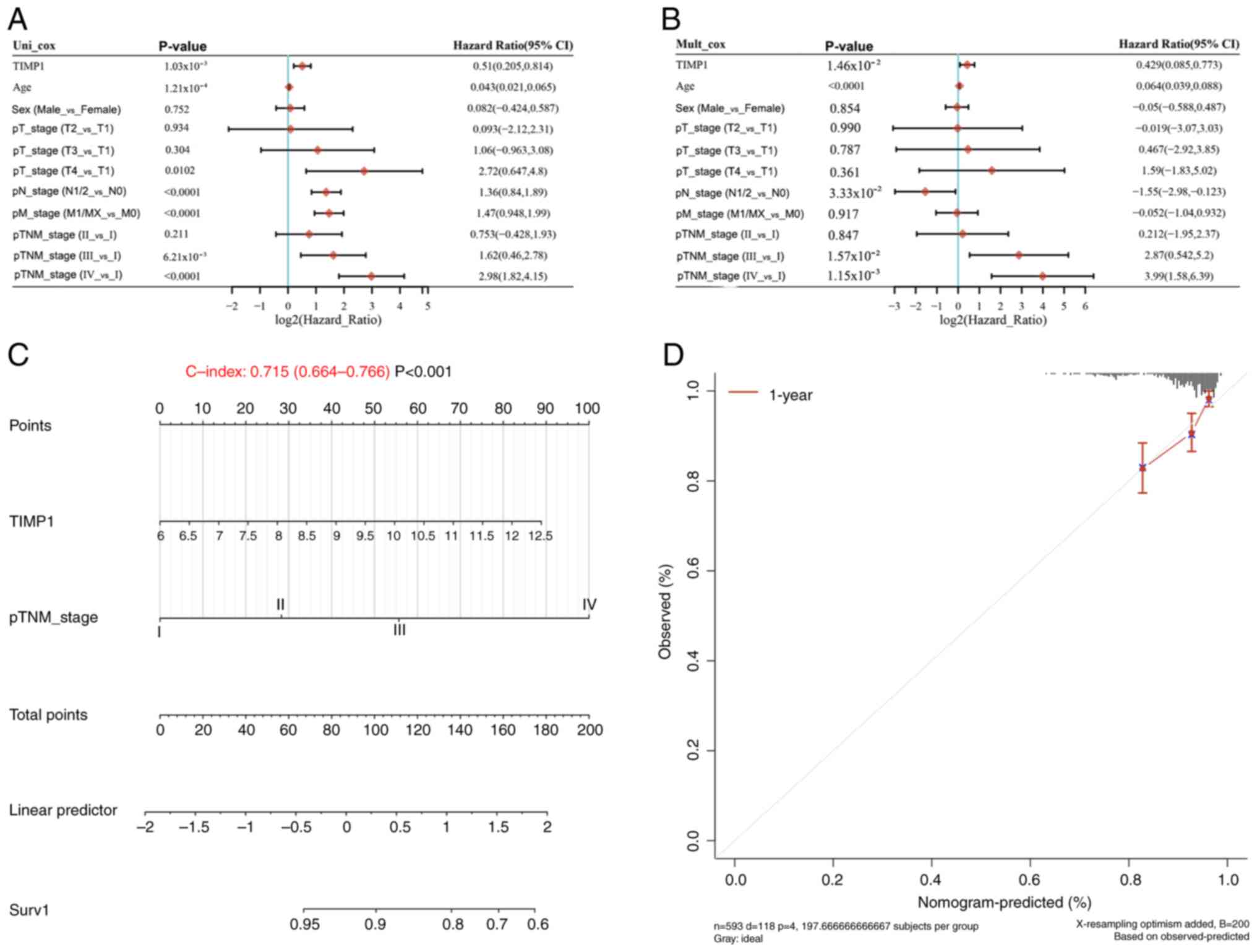

Survival prognosis analysis

The GEPIA2 database was used for the analysis of the

association between TIMP1 expression, overall survival and

disease-free survival in patients with CRC. In addition, the UALCAN

database was used for the analysis of the association between TIMP1

expression and overall survival. CRC samples with high TIMP1

expression (median, n=309) and low TIMP1 expression (median, n=310)

from TCGA database were used for further analysis. For survival

analysis, the log-rank test was employed to compare survival

differences between the two groups in the Kaplan-Meier analysis,

obtaining the P-value, hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence

interval (CI) using the log-rank test and univariate Cox

regression. To perform Cox regression analysis, univariate and

multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were

performed. The ‘forestplot’ package was used to visually present

the P-value, HR and 95% CI for each variable using a forest plot.

Subsequently, based on the multivariate Cox proportional hazard

model results, a Nomogram was constructed using the ‘rms’ package

to predict the total recurrence rate over X years. All statistical

analyses were performed using R software (v4.0.3).

Immune correlation analysis

To reliably evaluate immune scores in CRC,

‘immunedeconv’ was used, which is an R package (v4.1.3) that

combines two advanced algorithms, including Tumor IMune Estimation

Resource (TIMER) and Estimate the Proportion of Immune and Cancer

(EPIC), applied to TCGA CRC data (n=620) (25,26).

Each algorithm has been benchmarked for its unique strengths. For

result analysis and visualization, the R package ‘ggClusterNet’ was

employed. In addition, Spearman's correlation analysis was

performed to assess the relationship between TIMP1 and immune cells

(CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) in CRC using TCGA

data (n=620).

Association analysis of TIMP1

expression and tumor mutation burden (TMB)/microsatellite

instability (MSI)

RNAseq data and clinical information of CRC (n=620)

were obtained from TCGA database. Spearman's correlation analysis

was used to assess the correlation between TIMP1 and TMB/MSI

(25,26).

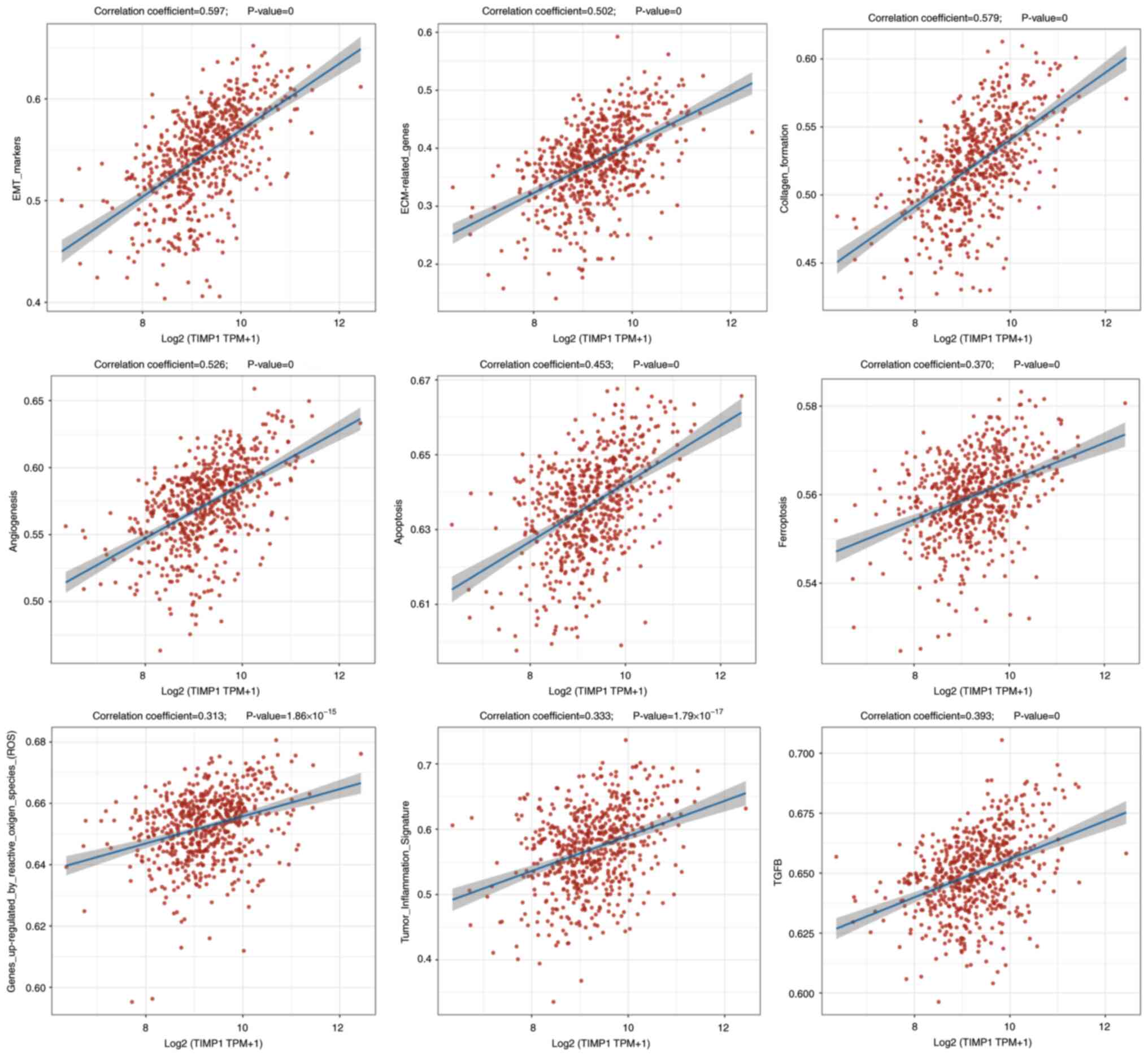

Association analysis of TIMP1

expression and pathway scores

CRC RNAseq data and the clinical information (n=620)

were retrieved from TCGA database. Following compilation of the

genes from the relevant pathways, the ‘GSVA’ package was used in R

software with the parameter method ‘ssgsea’ used to perform

single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA). Finally, the

correlation between gene expression and pathway scores was assessed

using Spearman's correlation analysis (27–29).

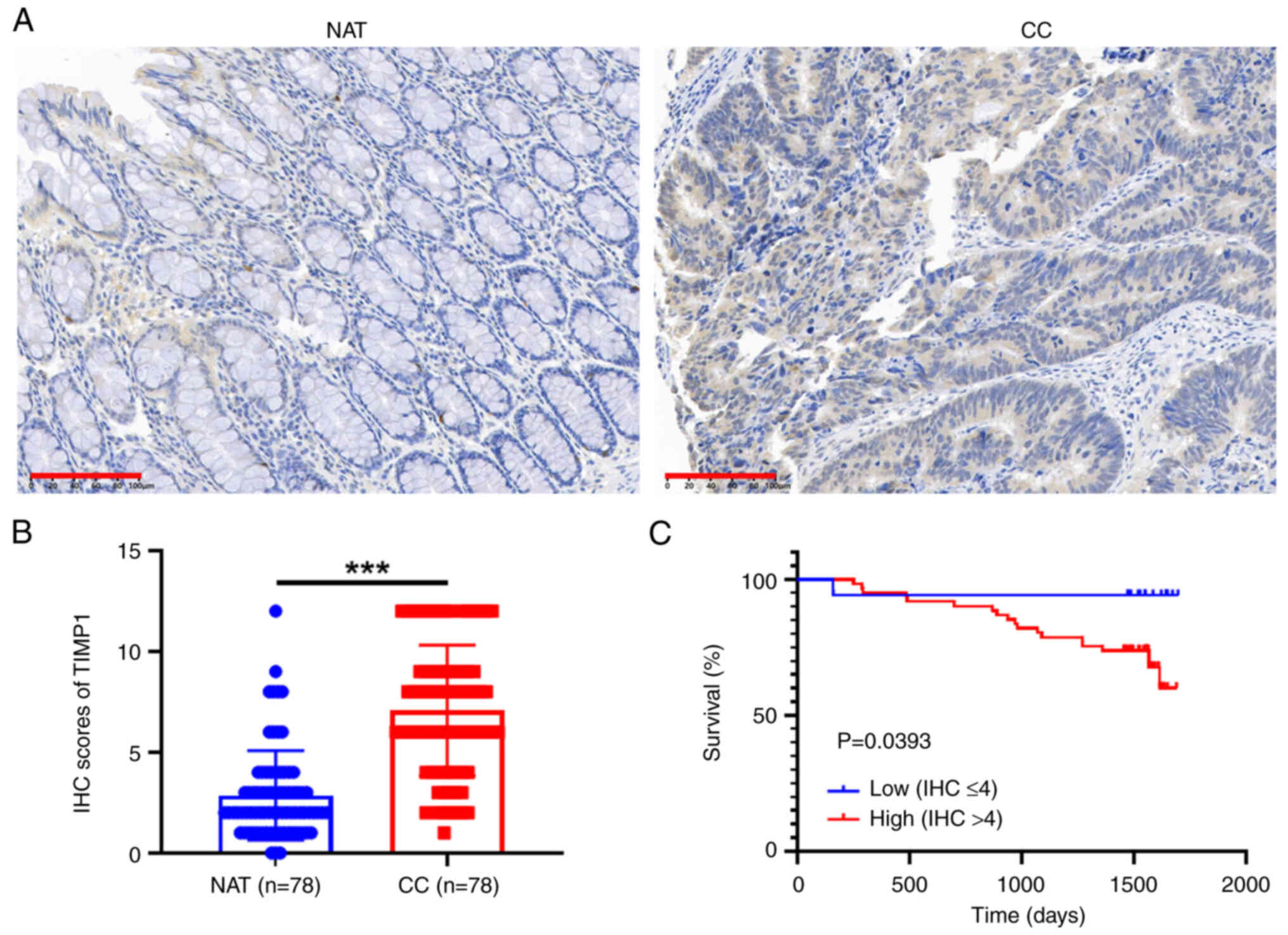

CRC specimens and immunohistochemical

(IHC) staining

A colon cancer tissue microarray (TMA) was purchased

from Hunan Aifang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., and the relevant

follow-up data were included. The TMA comprised 78 pairs of colon

cancer and normal tissues. The patient characteristics are

summarized in Table SI. The

present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of

Soochow University's First Affiliated Hospital (approval no.

2021-327).

IHC staining was performed as follows (30): Tissue samples were subjected to

fixation utilizing a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) maintained at an ambient temperature of

25°C for a duration of 24 h. Subsequently, the specimens were

processed for paraffin embedding. Sections, each with a thickness

of 5 µm, excised from the paraffin-embedded tissue blocks,

underwent deparaffinization and rehydration procedures. Following

antigen retrieval conducted with a 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH

6.0; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), the sections were

treated with a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution at room temperature

for 10 min to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity and to

mitigate non-specific protein interactions. The sections were then

incubated with anti-TIMP1 antibodies (1:300 dilution; cat. no.

16644-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) overnight at 4°C, succeeded by

incubation with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody

working solution (1:500 dilution; cat. no. SA1020; Boster

Biological Technology Co. Ltd.) at 37°C for 30 min. Immunodetection

was subsequently executed employing the Dako EnVision detection

system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The prepared slides were

examined and images were captured under a fluorescence microscope

(Leica Microsystems). The IHC score was determined by multiplying

the staining intensity (negative, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; and

strong, 3) by the percentage of the stained area (0%, 0; ≤25%, 1;

25–50%, 2; 50–75%, 3; and >75%, 4).

Statistical analysis

R software (version 4.0.3) and GraphPad Prism 8.0

(Dotmatics) were used for both data analysis and visualization. The

data are presented as the mean ± SD from a minimum of three

replicates. Differences between two groups were assessed using an

unpaired t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test or paired t-test, as

appropriate. Fisher's exact test or χ2 test were used to

analyze the associations between the expression of TIMP1 and

clinicopathological features. Spearman's correlation analysis was

performed to assess the correlation between TIMP1 and immune cells

(CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) in CRC using TCGA

data (n=620). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

TIMP1 is highly expressed in CRC

tissues

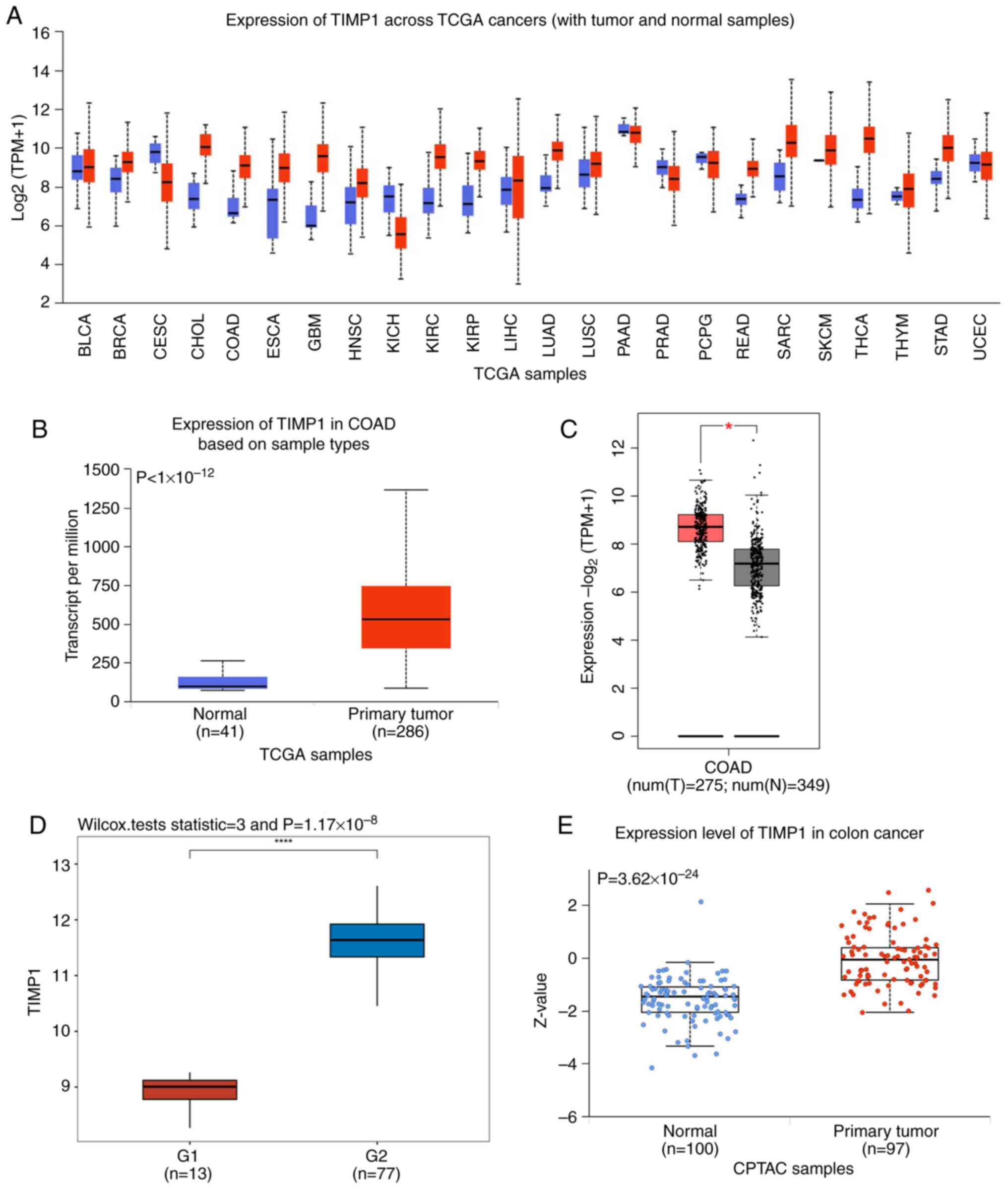

Using the UALCAN database, TIMP1 mRNA expression was

assessed across TCGA cancer tissues. The results indicated that,

compared with that in normal tissues, its expression was markedly

upregulated in several tumor types, including CRC. In 15/24 tumors,

TIMP1 was overexpressed (Fig. 1A).

Based on a database visualization website of UALCAN with TCGA, the

mRNA expression levels of TIMP1 were also significantly higher in

colon cancer samples compared with those in normal samples

(Fig. 1B). The GSE24550 dataset was

also evaluated, where the specimens of patients with colon cancer

exhibited high TIMP1 expression compared with those of normal

controls (Fig. 1C). Furthermore,

TCGA data analysis of GEPIA confirmed this result (Fig. 1D). Moreover, CPTAC data revealed

that the protein expression of TIMP1 exhibited significant

upregulation specifically in the tumor tissue, in comparison with

that in normal tissues (Fig.

1E).

Associations between TIMP1 and

clinicopathological features

To assess the association between TIMP1 expression

levels in CRC tissues and the clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with CRC, STAR-counts data and relevant clinical

information were obtained from TCGA database. The results revealed

that TIMP1 expression was significantly associated with survival

(P=0019) and ethnicity (P=0.0404); however, no significant

associations were noted between TIMP1 levels and age, sex,

pathological (p) tumor (T)-node (N)-metastasis (M) stage, pT stage,

pN stage or pM stage (Table I).

Association between TIMP1 expression

and prognosis

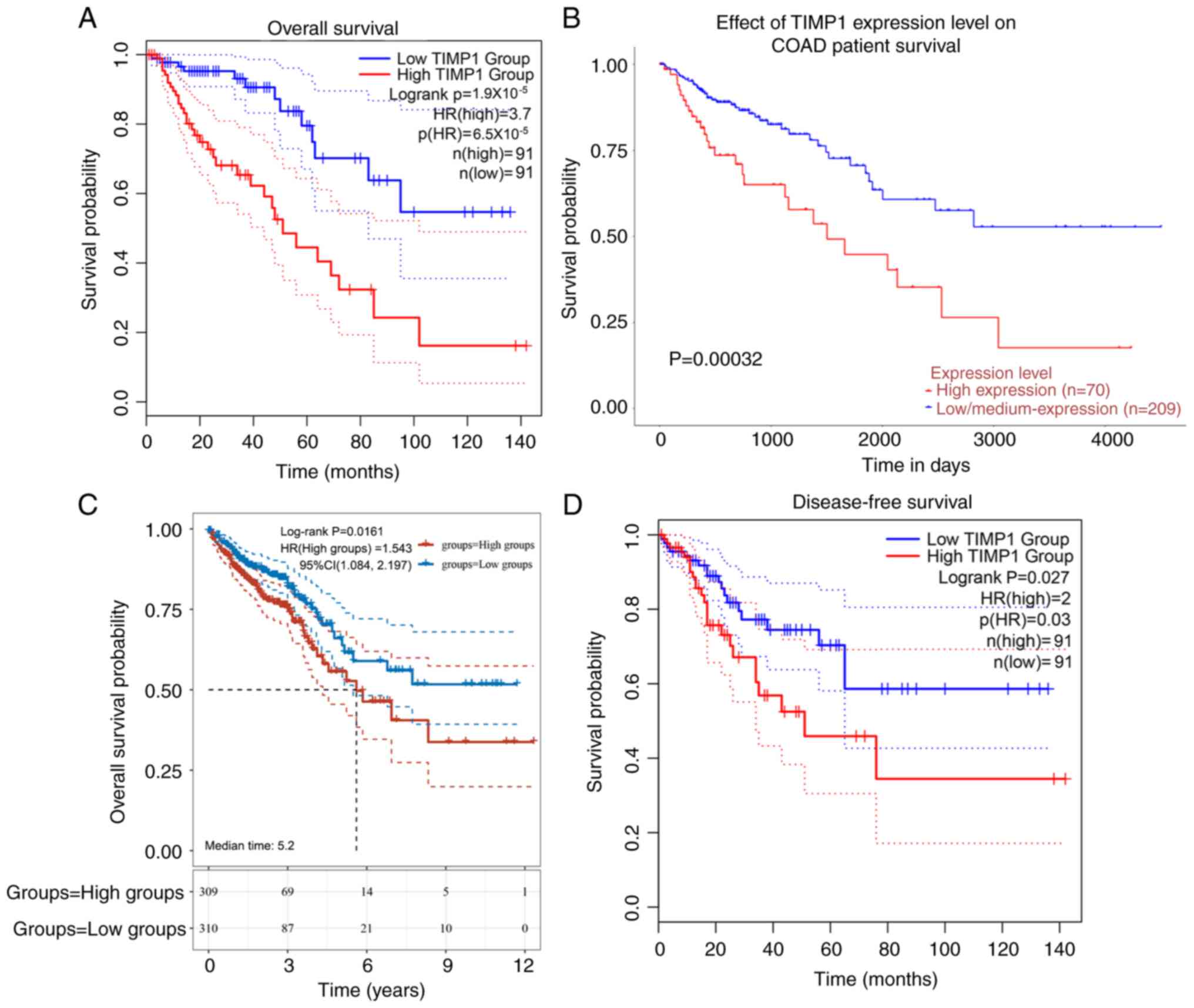

Patients with CRC and high TIMP1 expression

exhibited shorter overall survival compared with those with low

expression (Fig. 2A-C). Notably,

TIMP1 expression was significantly associated with disease-free

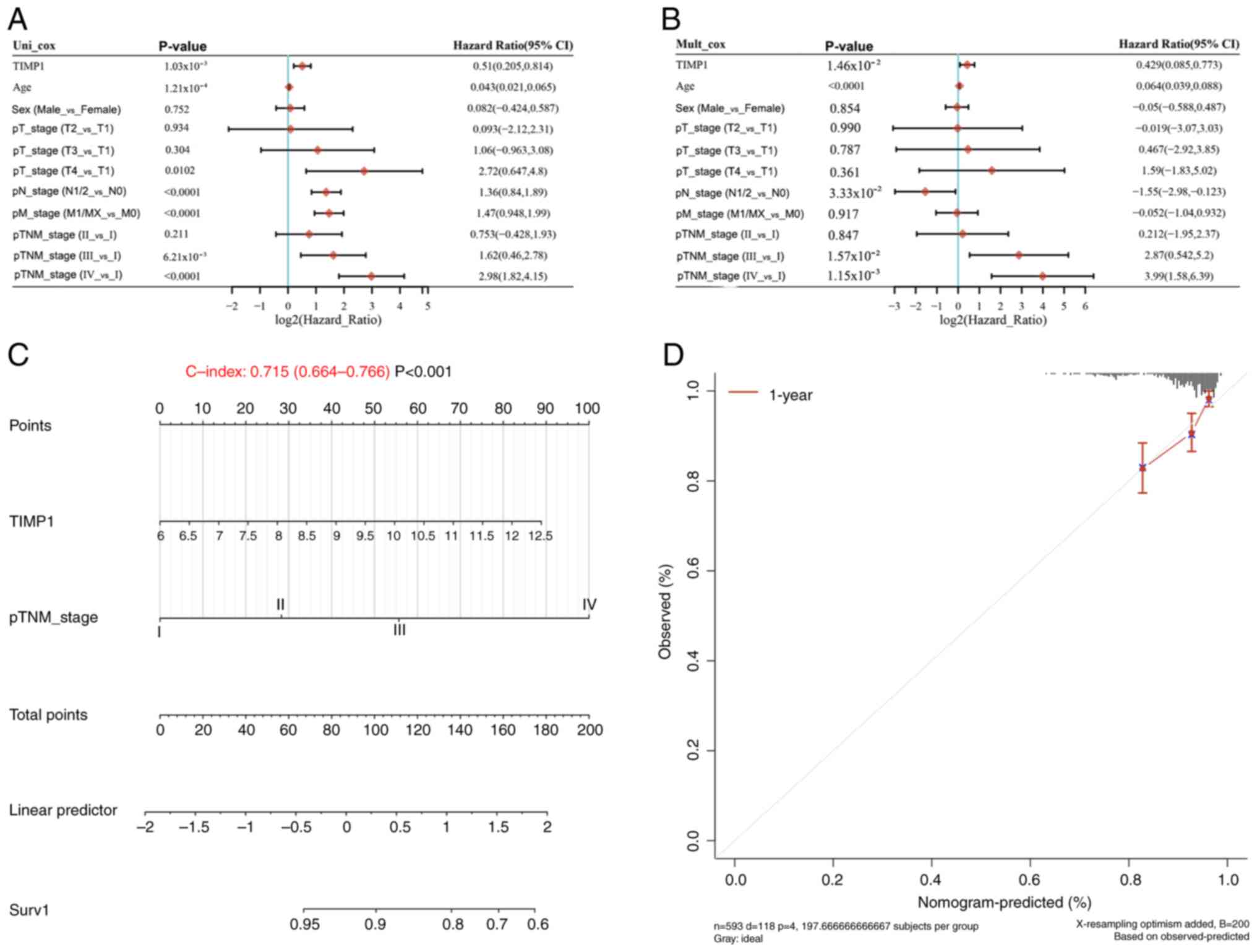

survival (Fig. 2D). Univariate Cox

regression analysis identified TIMP1 expression, age, pT stage (T4

vs. T1), pN stage (N1/2 vs. N0), pM stage (M1/X vs. M0) and pTNM

stage (III vs. I and IV vs. I) as significant predictors of overall

survival in patients with CRC (Fig.

3A). The results of multivariate Cox regression analysis

further confirmed that TIMP1 expression, age, pN stage (N1/2 vs.

N0) and pTNM stage (III vs. I, IV vs. I) were independent

prognostic factors for overall survival (Fig. 3B). Based on these factors, nomograms

were constructed using TCGA datasets to calculate prognostic scores

for patients with CRC, yielding a survival probability of 0.715

(Fig. 3C). The calibration curves

for TCGA cohorts were closely aligned with the 45-degree diagonal

line (Fig. 3D), indicating optimal

concordance between predicted and actual survival

probabilities.

| Figure 3.TIMP1 serves as a prognostic factor

for overall survival in CRC. (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate

Cox analyses of TCGA data of patients with CRC for TIMP1 expression

and clinical characteristics. (C) Nomogram formulated to predict

1-year overall survival for patients with CRC from TCGA data. (D)

Calibration curve for the overall survival nomogram model in the

discovery cohort, where the diagonal dashed line denotes the ideal

nomogram, and the red line represent the observed 1-year nomograms.

TIMP1, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1; CRC,

colorectal cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; HR, hazard ratio;

CI, confidence interval; p, pathological; T, tumor; N, node; M,

metastasis. |

Association between TIMP1 and

immunity

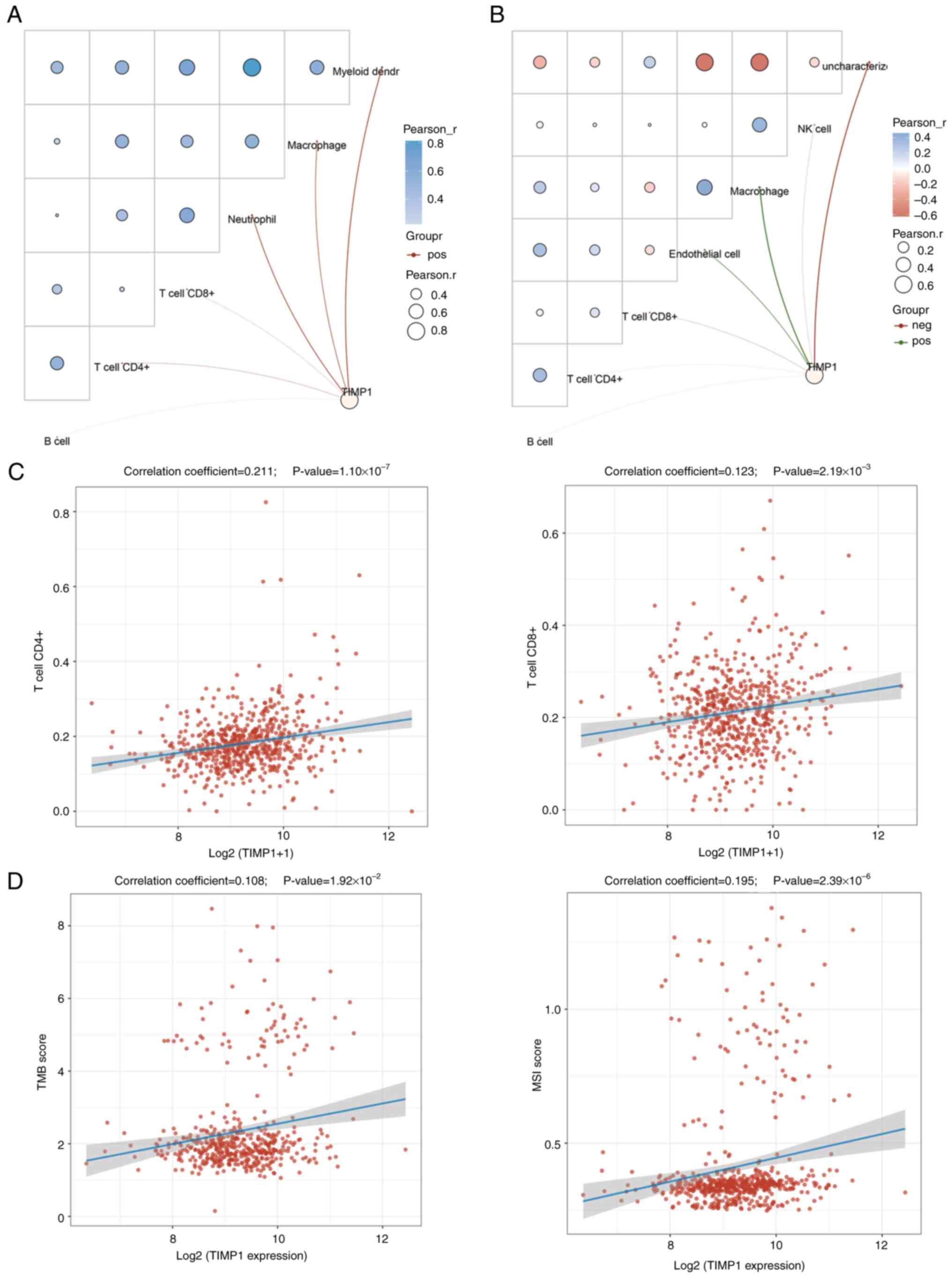

Subsequently, the role of TIMP1 in immunity was used

to evaluate its potential in CRC immunotherapy. Network connection

diagrams and heatmaps illustrated the link between TIMP1 expression

and immune scores, where red/blue intensity and ring size reflected

correlation strength (Fig. 4A and

B). Red lines indicate the positive correlations and green

lines the negative. Both TIMER and EPIC scores revealed the

positive correlation of TIMP1 with CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells. Spearman's correlation analysis using TCGA

CRC samples further confirmed this significant association

(Fig. 4C).

Previous studies have reported that TMB and MSI are

valuable biomarkers that provide insights into cancer prognosis and

treatment decisions (31–33). Both TMB and MSI serve roles in

cancer prognosis, treatment selection and immunotherapy development

(34). The findings of the present

study demonstrate a significant but weak positive correlation

between TIMP1 expression and TMB and MSI in CRC (Fig. 4D). This suggests that TIMP1 can

potentially serve as a biomarker to identify patients who may

benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly in tumors

where high TMB and MSI predict a favorable response to

immunotherapy.

TIMP1 and pathways

The ssGSEA algorithm was applied to compute the

enrichment fraction of each sample for specific pathways, thereby

exploring the sample-pathway relationship (27). The calculated fractions intuitively

reflected the interaction and association between samples and

pathways. The results indicated that in CRC, TIMP1 may be

positively correlated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

markers, extracellular matrix (ECM)-related genes, collagen

formation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, ferroptosis, the upregulation

of the expression levels of genes caused by reactive oxygen species

(ROS), tumor inflammation and the TGF-β signaling pathway (Fig. 5). Overall, these findings indicate

that TIMP1 may be associated with multiple pathways and may

regulate the progression of CRC.

TIMP1 protein expression in CRC

tissues and prognosis

The IHC assay indicated that the expression levels

of TIMP1 were significantly higher in colon cancer tissues than

those in adjacent normal tissues (Fig.

6A and B). Notably, individuals with high TIMP1 expression (IHC

score >4) exhibited a significantly reduced survival rate

compared with those with low TIMP1 expression (IHC score ≤4) in

colon cancer (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

Most patients with CRC are diagnosed at an advanced

stage, which contributes to the poor prognosis commonly noted in

this patient population (35,36).

However, previous research indicates that an early diagnosis of CRC

can markedly improve patient outcomes (37). As such, the identification of

effective biomarkers for early CRC detection is crucial, as they

can serve a pivotal role in enhancing the prognosis of patients

with CRC.

TIMP1 belongs to the TIMP family, which includes

other members such as TIMP2, TIMP3 and TIMP4 (14). Research has indicated that TIMP1

expression is upregulated across multiple tumor types and this

upregulation is associated with poor prognosis and reduced survival

in patients with cancer (16). For

example, TIMP1 expression has been associated with gastric cancer

differentiation and poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer

(38). Similarly, high TIMP1

expression in lung cancer tumors is associated with an unfavorable

prognosis (39). Macedo et

al (40) also reported that

elevated TIMP1 levels in patients with colon and gastric cancer are

associated with poor prognosis. These reports are consistent with

the findings of the present study, which revealed that both TIMP1

mRNA and protein levels were markedly elevated in CRC tissues, and

positively associated with worse overall and disease-free survival

in patients with CRC. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression

analyses further established high TIMP1 expression as an

independent prognostic indicator for overall survival in CRC. These

results indicate that TIMP1 expression is likely a predictor of CRC

prognosis.

Previous studies have established immunity as a

prognostic indicator for cancer progression (41–43).

Emerging mechanistic studies identify TIMP1 as a critical tumor

immune modulator (44,45). In thyroid cancer, TIMP1 promotes

cancer cell progression by inducing macrophage phenotypic

polarization via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (44). In glioblastoma, the expression of

TIMP1, induced by Sp1, is markedly elevated in tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes and is associated with cancer progression (45). Moreover, TIMP1 expression in gliomas

is associated with tumor immune infiltration and immune

checkpoint-related gene expression (46). Wang et al (47) reported that intracellular

TIMP-1-CD63 signaling directs immune escape and metastasis

evolution in KRAS-mutated pancreatic cancer cells. In the present

study, network connection diagrams and heatmaps visualized the

association between TIMP1 expression and immune scores. Notably,

TIMP1 indicated a significant but weak correlation with

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in CRC. Overall, these

findings suggest that TIMP1 may modulate the CRC tumor immune

environment by influencing CD4+ and CD8+ T

cell infiltration and function.

Immunotherapy, particularly the use of immune

checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has transformed cancer treatment by

leveraging the capacity of the immune system to combat tumors

(48). However, in contrast to

cancer types, such as non-small-cell lung cancer and melanoma,

which are known to be sensitive to immunotherapy, there is a lack

of reliable predictive biomarkers in multiple cancer types

(49). TMB and MSI serve as genomic

biomarkers to identify patients likely to benefit from ICIs, and

ICIs have shown promise in colon cancer treatment, notably in

patients with high TMB and MSI (34). The present study indicated a

significant association between TIMP1 expression and TMB and MSI in

CRC. This suggests that TIMP1 may be a potential predictive

biomarker for colon cancer immunotherapy.

Furthermore, previous studies have reported that

TIMP-1 can regulate tumor cell behavior by inducing signaling

pathways associated with cell growth, proliferation and survival

(14,16). For example, Song et al

(50) reported that inhibiting

TIMP1 expression reduced proliferation and metastasis, whilst

promoting apoptosis by targeting the FAK-PI3K/AKT and MAPK

pathways. The use of short hairpin RNA to knockdown TIMP1

expression was associated with a notable reduction in cell

proliferation and invasion in right-sided patient-derived organoids

from both left- and right-sided CRCs. This effect was achieved by

modulating the FAK/AKT signaling pathway (51). In the present study, the ssGSEA

algorithm revealed a positive correlation between TIMP1 expression

in CRC and multiple biological processes and pathways, including

EMT markers, ECM-related genes, collagen formation, angiogenesis,

apoptosis, ferroptosis, ROS-upregulated genes, tumor inflammation

signatures and the TGF-β pathway. Whilst further comprehensive

experimental validation is required to evaluate the pathways

associated with TIMP1, the existing data strongly suggest that

TIMP1 serves pivotal roles in driving CRC progression and

metastasis.

Moreover, whilst the present study highlights the

clinical significance of TIMP1, certain limitations are present.

Firstly, specific analyses rely on retrospective public-database

data; therefore, prospective studies are required to verify the

clinical relevance of the findings. Given the complexity of CRC and

the varied histological phenotypes, more detailed mechanistic and

clinical research is essential to explore the roles of TIMP1 across

CRC subtypes. In addition, the sample size of the present CRC

cohort is limited. In future work, the validation cohort will be

expanded by constructing a larger, multi-center TMA with balanced

representation of major CRC subtypes (such as CMS, MSI-H and

BRAF-mutant), on which subtype-stratified analyses will be

performed to determine if the role of TIMP1 is universal or

subtype-specific. Furthermore, comprehensive in vitro and

in vivo experiments are required to clarify the mechanistic

role of TIMP1 in tumor progression and its interaction with the

TME. Despite these limitations, the present study guides future

research, including clinical work and basic experiments, which will

be part of the subsequent research focus.

In conclusion, high TIMP1 expression in CRC is

associated with a poor prognosis for patients with CRC. TIMP1 may

also modulate the CRC immune microenvironment and facilitate CRC

progression and metastasis. The data suggest that TIMP1 represents

a promising diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for

CRC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Collaborative Custom

Development of RNA Probes (grant no. P112213323).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SX, DZ and TS contributed to the study conception

and design. JG contributed to performing experiments, acquisition

of data and interpretation of data. FC performed experiments. JG

and TS wrote the original manuscript. DZ and SX revised the

manuscript. JG and TS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was granted approval by the

Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of

Soochow University (Suzhou, China; approval no. 2021-327). Written

informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Abedizadeh R, Majidi F, Khorasani HR,

Abedi H and Sabour D: Colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review of

carcinogenesis, diagnosis, and novel strategies for classified

treatments. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43:729–753. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tao XY, Li QQ and Zeng Y: Clinical

application of liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer: Detection,

prediction, and treatment monitoring. Mol Cancer. 23:1452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mousavi SE, Ilaghi M, Hamidi Rad R and

Nejadghaderi SA: Epidemiology and socioeconomic correlates of

colorectal cancer in Asia in 2020 and its projection to 2040. Sci

Rep. 15:266392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang B, Li P and Zhao Y:

Methods and biomarkers for early detection, prediction, and

diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother.

163:1147862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mo S, Tang P, Luo W, Zhang L, Li Y, Hu X,

Ma X, Chen Y, Bao Y, He X, et al: Patient-derived organoids from

colorectal cancer with paired liver metastasis reveal tumor

heterogeneity and predict response to chemotherapy. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 9:e22040972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang W and Wang S: Relationships between

nutritional status and serum adipokine levels with chemotherapy

efficacy in late-stage colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal

Dis. 40:252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Prasetyanti PR and Medema JP: Intra-tumor

heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol Cancer.

16:412017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yu X, Liu R, Gao W, Wang X and Zhang Y:

Single-cell omics traces the heterogeneity of prostate cancer cells

and the tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 28:382023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Guo L, Wang Y, Yang W, Wang C, Guo T, Yang

J, Shao Z, Cai G, Cai S, Zhang L, et al: Molecular profiling

provides clinical insights into targeted and immunotherapies as

well as colorectal cancer prognosis. Gastroenterology.

165:414–428.e7. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Singh H, Sahgal P, Kapner K, Corsello SM,

Gupta H, Gujrathi R, Li YY, Cherniack AD, El Alam R, Kerfoot J, et

al: RAS/RAF Comutation and ERBB2 copy number modulates HER2

heterogeneity and responsiveness to HER2-directed therapy in

colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 30:1669–1684. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jalali P, Aliyari S, Etesami M, Saeedi

Niasar M, Taher S, Kavousi K, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E and Salehi

Z: GUCA2A dysregulation as a promising biomarker for accurate

diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Clin Exp Med.

24:2512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lu S, Sun X, Tang H, Yu J, Wang B, Xiao R,

Qu J, Sun F, Deng Z, Li C, et al: Colorectal cancer with low

SLC35A3 is associated with immune infiltrates and poor prognosis.

Sci Rep. 14:3292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Parisi E, Hidalgo I, Montal R, Pallise O,

Tarragona J, Sorolla A, Novell A, Campbell K, Sorolla MA, Casali A

and Salud A: PLA2G12A as a novel biomarker for colorectal cancer

with prognostic relevance. Int J Mol Sci. 24:108892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jackson HW, Defamie V, Waterhouse P and

Khokha R: TIMPs: Versatile extracellular regulators in cancer. Nat

Rev Cancer. 17:38–53. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Caterina NC, Windsor LJ, Bodden MK,

Yermovsky AE, Taylor KB, Birkedal-Hansen H and Engler JA:

Glycosylation and NH2-terminal domain mutants of the tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1). Biochim Biophys Acta.

1388:21–34. 1388. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Justo BL and Jasiulionis MG:

Characteristics of TIMP1, CD63, and β1-Integrin and the functional

impact of their interaction in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 22:93192021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Eckfeld C, Haussler D, Schoeps B, Hermann

CD and Kruger A: Functional disparities within the TIMP family in

cancer: Hints from molecular divergence. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

38:469–481. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tian Z, Ou G, Su M, Li R, Pan L, Lin X,

Zou J, Chen S, Li Y, Huang K and Chen Y: TIMP1 derived from

pancreatic cancer cells stimulates Schwann cells and promotes the

occurrence of perineural invasion. Cancer Let. 546:2158632022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Guccini I, Revandkar A, D'Ambrosio M,

Colucci M, Pasquini E, Mosole S, Troiani M, Brina D,

Sheibani-Tezerji R, Elia AR, et al: Senescence reprogramming by

TIMP1 deficiency promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell.

39:68–82.e9. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chandrashekar DS, Karthikeyan SK, Korla

PK, Patel H, Shovon AR, Athar M, Netto GJ, Qin ZS, Kumar S, Manne

U, et al: UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis

platform. Neoplasia. 25:18–27. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya

SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B and Varambally

S: UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression

and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 19:649–658. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:W556–W560. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sveen A, Agesen TH, Nesbakken A, Rognum

TO, Lothe RA and Skotheim RI: Transcriptome instability in

colorectal cancer identified by exon microarray analyses:

Associations with splicing factor expression levels and patient

survival. Genome Med. 3:322011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang Z, Wang Y, Peng M and Yi L: UBASH3B

is a novel prognostic biomarker and correlated with immune

infiltrates in prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 9:15172019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D,

Bortone DS, Ou Yang TH, Porta-Pardo E, Gao GF, Plaisier CL, Eddy

JA, et al: The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity.

48:812–830.e14. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, Miya J,

Wing MR, Chen HZ, Reeser JW, Yu L and Roychowdhury S: Landscape of

microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis

Oncol. 2017.PO.17.00073. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wei J, Huang K, Chen Z, Hu M, Bai Y, Lin S

and Du H: Characterization of glycolysis-associated molecules in

the tumor microenvironment revealed by pan-cancer tissues and lung

cancer single cell data. Cancers (Basel). 12:17882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hanzelmann S, Castelo R and Guinney J:

GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data.

BMC Bioinformatics. 14:72013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xiao Z, Dai Z and Locasale JW: Metabolic

landscape of the tumor microenvironment at single cell resolution.

Nat Commun. 10:37632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun L, Chen Y, Xia L, Wang J, Zhu J, Li J,

Wang K, Shen K, Zhang D, Zhang G, et al: TRIM69 suppressed the

anoikis resistance and metastasis of gastric cancer through

ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of PRKCD. Oncogene.

42:3619–3632. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kendre G, Murugesan K, Brummer T, Segatto

O, Saborowski A and Vogel A: Charting co-mutation patterns

associated with actionable drivers in intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 78:614–626. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Di Mauro A, Santorsola M, Savarese G,

Sirica R, Ianniello M, Cossu AM, Ceccarelli A, Sabbatino F,

Bocchetti M, Carratu AC, et al: High tumor mutational burden

assessed through next-generation sequencing predicts favorable

survival in microsatellite stable metastatic colon cancer patients.

J Transl Med. 22:11072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shi S, Wang Y, Wu J, Zha B, Li P, Liu Y,

Yang Y, Kong J, Gao S, Cui H, et al: Predictive value of PD-L1 and

TMB for short-term efficacy prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer

and construction of prediction models. Front Oncol. 14:13422622024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hou W, Yi C and Zhu H: Predictive

biomarkers of colon cancer immunotherapy: Present and future. Front

Immunol. 13:10323142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sasidharan Nair V, Saleh R, Taha RZ, Toor

SM, Murshed K, Ahmed AA, Kurer MA, Abu Nada M, Al Ejeh F and Elkord

E: Differential gene expression of tumor-infiltrating

CD4+ T cells in advanced versus early stage colorectal

cancer and identification of a gene signature of poor prognosis.

Oncoimmunology. 9:18251782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Garborg K: Colorectal cancer screening.

Surg Clin North Am. 95:979–989. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tonini V and Zanni M: Why is early

detection of colon cancer still not possible in 2023? World J

Gastroenterol. 30:211–224. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zheng M, Wang P, Wang Y, Jia Z, Gao J, Tan

X, Chen H and Zu G: Clinicopathological and prognostic significance

of TIMP1 expression in gastric cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 24:1169–1176. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dantas E, Murthy A, Ahmed T, Ahmed M,

Ramsamooj S, Hurd MA, Lam T, Malbari M, Agrusa C, Elemento O, et

al: TIMP1 is an early biomarker for detection and prognosis of lung

cancer. Clin Transl Med. 13:e13912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Macedo FC, Cunha N, Pereira TC, Soares RF,

Monteiro AR, Bonito N, Valido F and Sousa G: A prospective cohort

study of TIMP1 as prognostic biomarker in gastric and colon cancer.

Chin Clin Oncol. 11:432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zheng J, Peng L, Zhang S, Liao H, Hao J,

Wu S and Shen H: Preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index as

a prognostic indicator for patients with urothelial carcinoma.

Front Immunol. 14:12750332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xiong S, Dong L and Cheng L: Neutrophils

in cancer carcinogenesis and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol.

14:1732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liu R, Lu J, Liu J, Liao Y, Guo Y, Shi P,

Wang Z, Wang H and Lai J: Macrophages in prostate cancer: Dual

roles in tumor progression and immune evasion. J Transl Med.

23:6152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lin X, Zhao R, Bin Y, Huo R, Xue G and Wu

J: TIMP1 promotes thyroid cancer cell progression through

macrophage phenotypic polarization via the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway. Genomics. 116:1109142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Liu L, Yang S, Lin K, Yu X, Meng J, Ma C,

Wu Z, Hao Y, Chen N, Ge Q, et al: Sp1 induced gene TIMP1 is related

to immune cell infiltration in glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 12:111812022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Xu J, Wei C, Wang C, Li F, Wang Z, Xiong

J, Zhou Y, Li S, Liu X, Yang G, et al: TIMP1/CHI3L1 facilitates

glioma progression and immunosuppression via NF-kappaB activation.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1870:1670412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang CA, Hou YC, Hong YK, Tai YJ, Shen C,

Hou PC, Fu JL, Wu CL, Cheng SM, Hwang DY, et al: Intercellular

TIMP-1-CD63 signaling directs the evolution of immune escape and

metastasis in KRAS-mutated pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer.

24:252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Butterfield LH and Najjar YG:

Immunotherapy combination approaches: Mechanisms, biomarkers and

clinical observations. Nat Rev Immunol. 24:399–416. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bai R, Lv Z, Xu D and Cui J: Predictive

biomarkers for cancer immunotherapy with immune checkpoint

inhibitors. Biomark Res. 8:342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Song G, Xu S, Zhang H, Wang Y, Xiao C,

Jiang T, Wu L, Zhang T, Sun X, Zhong L, et al: TIMP1 is a

prognostic marker for the progression and metastasis of colon

cancer through FAK-PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 35:1482016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ma B, Ueda H, Okamoto K, Bando M, Fujimoto

S, Okada Y, Kawaguchi T, Wada H, Miyamoto H, Shimada M, et al:

TIMP1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion capability of

right-sided colon cancers via the FAK/Akt signaling pathway. Cancer

Sci. 113:4244–4257. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|