Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of

cancer-associated morbidity and mortality globally, with ~2.1

million new cases and 800,000 mortalities annually (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

accounts for ~85% of all lung cancer cases (2). Despite recent advancements in early

detection techniques (low-dose computed tomography screening) and

treatment options, survival rates have only slightly improved and

the overall prognosis for patients with metastatic lung cancer

remains poor (3–6). Brain metastases (BM) are a common

metastatic pattern in lung cancer; at initial diagnosis, 10% of

patients with lung cancer present with BM and during the course of

the disease, 40–60% of patients with lung adenocarcinoma will

develop BM (7). BM poses a notable

clinical challenge, as it often leads to rapid neurological

deterioration and markedly impacts the quality of life of patients

(8). The presence of BM in patients

with lung adenocarcinoma markedly complicates treatment decisions

and therapeutic outcomes.

Patients with epidermal growth factor receptor

(EGFR) mutations are at a cumulative risk of BM as high as 70%

(9). This risk is particularly

pronounced in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma, where resistance to

first- and second-generation EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs;

such as gefitinib/erlotinib and afatinib/dacomitinib, respectively)

often results in disease progression and the development of BM. The

molecular mechanisms underlying this progression are not fully

understood; however, they are considered to involve a combination

of tumor heterogeneity, blood-brain barrier penetration and changes

in treatment response (10–12).

BM markedly impacts both quality of life and

prognosis. Common symptoms, including headaches, seizures,

cognitive dysfunction and motor deficits, complicate symptom

management and survival prediction (13,14).

The present study aimed to stratify the prognosis of patients with

lung cancer with BM and compare the predictive accuracy of various

prognostic models in a specific cohort: Patients with locally

advanced lung adenocarcinoma, EGFR mutations and BM development

following radical radiotherapy. In this cohort, accurate prediction

of patient outcomes is key to tailoring treatment plans and

improving survival rates. The use of prognostic models

incorporating clinical, molecular and radiological factors can

potentially guide clinical decisions and enhance patient care in

the future.

Patients and methods

Patients

A retrospective analysis was performed on patients

with lung adenocarcinoma with BM admitted to Cangzhou Hospital of

Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine-Hebei Province

(Cangzhou, China), between January 2016 and December 2022. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Pathologically confirmed

lung adenocarcinoma; ii) locally advanced stage (inoperable or

surgery-intolerant at diagnosis, re-staged according to the 8th

edition of the AJCC TNM, IIIA, IIIB, IIIC) with initial treatment

consisting of radical radiotherapy (either synchronous or

sequential) (15); iii) BM

diagnosed via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, with

the brain as the first site of distant metastasis recurrence after

completion of radical radiotherapy. At initial diagnosis (prior to

radical treatment), no evidence of distant metastasis (M0 stage)

was present in any patient (16);

iv) exon 19 deletion (19DEL) or exon 21 point mutation (L858R

mutation) identified by genetic testing; and v) complete medical

records. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients lost

to follow-up; and ii) Patients with other primary malignant tumors.

A total of 340 patients with lung adenocarcinoma and BM were

initially screened for eligibility during the present study period.

The patient selection process is detailed in Fig. S1. Briefly, 80 patients were

excluded for the following reasons: i) 32 had other EGFR mutation

types or were EGFR wild-type; ii) 25 had other primary malignant

tumors; iii) 15 had incomplete medical records or were lost to

follow-up; and iv) 8 did not receive radical radiotherapy as

initial treatment. In total, 260 patients met all inclusion

criteria and constituted the present study cohort for analysis.

Definition of key variables and

molecular testing

Synchronous and metachronous BM

BM detected at the initial diagnosis of lung

adenocarcinoma or within 6 months thereafter were classified as

synchronous. BM developing >6 months after the initial diagnosis

were classified as metachronous (17).

Adjudication of primary tumor

control

‘Primary tumor control’ was defined as the absence

of progression (for example, complete response, partial response or

stable disease) at the primary pulmonary site, assessed via

contrast-enhanced CT of the chest. This assessment was performed at

the time of BM diagnosis, referencing baseline imaging obtained

prior to the initiation of radical radiotherapy (18).

Determination of EGFR mutation

status

EGFR mutation status (19DEL and exon 21 L858R point

mutation) was determined from tumor tissue samples obtained via

biopsy at initial diagnosis. Mutations were identified using a

commercially available and clinically validated Amplification

Refractory Mutation System PCR kit (AmoyDx® EGFR

Mutation Detection Kit). All genetic testing was performed in the

central laboratory of Cangzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional

Chinese and Western Medicine-Hebei Province (Cangzhou, China) prior

to the administration of any EGFR-TKI therapy.

Timing of EGFR-TKI therapy associated

with BM

The majority of patients (95%) initiated EGFR-TKI

therapy after BM diagnosis. The timing of TKI initiation (before or

after BM diagnosis) was recorded and included as a binary covariate

in the initial univariate survival analysis. As it was not

significantly associated with overall survival (OS; P>0.1), it

was not included in the final multivariable model.

Classification of EGFR-TKIs

In the present study, EGFR-TKIs were categorized by

generation. First-generation TKIs included gefitinib and erlotinib,

second-generation TKIs included afatinib and third-generation TKIs

referred to osimertinib. The term ‘first- or second-generation

TKIs’ refers to the group of patients who did not receive

third-generation TKI as part of their initial treatment regimen.

The timing of TKI therapy associated with cranial radiotherapy was

categorized. Concurrent therapy was defined as TKI initiation

within 30 days before or after the start of radiotherapy.

Brain metastasis scoring system

model

The recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) scoring

system (19) classifies patients

into three groups: i) Grade I for patients ≤65 years old, with a

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score ≥70, controlled primary

tumor and no extracranial metastases (20); ii) grade III for patients with a KPS

score <70; and iii) grade II for all others. The basic score for

BM (BSBM) system (21) utilizes

three prognostic factors: KPS score (50–70 and 70–100), primary

tumor control and presence or absence of extracranial metastases,

assigning values of 1 and 0, respectively. The total score ranges

from 0 (worst) to 3 (best). The Diagnosis-Specific Graded

Prognostic Assessment (DS-GPA) system (22) incorporates four factors: Age

(>60, 50–60 and <60), KPS score (<70, 70–80 and >80),

extracranial metastases (present and absent) and number of BM

(>3, 2–3 and 1), with values assigned as 0, 0.5 and 1,

respectively, yielding a total score between 0 and 4. The lung

cancer-associated molecular (Lung-mol) GPA system (23) includes five factors: i) Age (≥70 and

<70 years); ii) KPS score (<70, 80 and 90–100); iii)

extracranial metastases (present and absent); iv) number of BM

(>4 and 1–4); and v) genetic status (EGFR/anaplastic lymphoma

kinase (ALK)−, EGFR/ALK+). These factors are

assigned values of 0, 0.5 and 1, respectively, with total scores

ranging from 0 to 4. All 260 patients were scored using the RPA,

BSBM, DS-GPA and Lung-mol GPA systems, followed by survival

comparisons to evaluate the predictive accuracy of each model.

Treatment after brain metastasis

Upon diagnosis of BM, treatment strategies were

individualized based on a multidisciplinary team discussion. The

primary approach involved systemic therapy with EGFR-TKIs and local

intracranial treatment. Local treatment for BM included

stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for patients with limited (1–4)

metastases or whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) for those with more

extensive or diffuse metastases. Supportive care, including

corticosteroids for peritumoral edema, was administered as

clinically indicated. The use of corticosteroids (primarily

dexamethasone) adhered to a standardized institutional protocol to

manage symptomatic BM or notable peritumoral edema, with a rapid

tapering strategy following clinical and radiological improvement

(24). The KPS score used in all

analyses was assessed after the initial stabilization of cerebral

edema and neurological symptoms, typically at the first planned

follow-up visit (4–6 weeks after BM diagnosis), to best reflect the

baseline functional status of the patient independent of acute

interventions. Following progression on first-line EGFR-TKIs,

subsequent treatment lines were administered at the discretion of

the physician, which could include switching to a third-generation

EGFR-TKI (if not initially used) based on repeat genetic testing,

combination chemotherapy or continued local therapy for new

lesions. Data on the type of intracranial radiotherapy (SRS vs.

WBRT) and subsequent systemic therapy lines were collected and

analyzed. In the present study cohort, the majority of patients

(177/260, 68.1%) received concurrent EGFR-TKI therapy and cranial

radiotherapy (Table I).

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the

present study cohort (n=260). |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the

present study cohort (n=260).

| Characteristic | Number of patients

(%) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

<60 | 152 (58.5) |

|

≥60 | 108 (41.5) |

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 122 (46.9) |

|

Female | 138 (53.1) |

| KPS |

|

|

<80 | 98 (37.7) |

|

≥80 | 162 (62.3) |

| Smoking

history |

|

| No | 140 (53.8) |

|

Yes | 120 (46.2) |

| EGFR mutation

type |

|

| Exon 19

deletion | 139 (53.5) |

|

L858R | 121 (46.5) |

|

EGFR-TKIs |

|

| Generation

I/II | 136 (52.3) |

| Generation III | 124 (47.7) |

| BM, n |

|

|

1-3 | 188 (72.3) |

|

>3 | 72 (27.7) |

| Extracerebral

metastasis |

|

| No | 162 (62.3) |

|

Yes | 98 (37.7) |

| Primary tumor

control |

|

| No | 172 (66.2) |

|

Yes | 88 (33.8) |

| Cranial RT |

|

| No | 41 (15.8) |

|

Yes | 219 (84.2) |

Follow-up and evaluation

Patients were followed up via telephone or

outpatient review from August 1, 2023. Follow-up occurred every 3

months for the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. At each

visit, patients underwent neurological assessments, brain MRI and

routine blood tests to monitor disease progression and

treatment-related side effects (such as rash, diarrhea, fatigue and

radionecrosis). OS was recorded from the diagnosis of BM to

mortality or the follow-up cut-off. Progression-free survival (PFS)

was also assessed, with a focus on changes in BM and extracranial

progression.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

(version 27.0; IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0;

Dotmatics), with AUC comparisons for each scoring system performed

using MedCalc software (version 23.0; MedCalc Software Ltd.). The

present study endpoint was OS, defined as the time from BM

diagnosis to mortality from any cause. The median follow-up time

was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method (25). Survival analysis was performed using

the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Categorical data are

presented as frequencies (percentages), and continuous data were

presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile

range). Variables for the multivariable Cox regression model were

selected based on two criteria: i) Established clinical relevance

as prognostic factors in lung cancer with BM, and ii) a

significance level of P<0.1 in the univariate analysis. This

approach aimed to minimize the risk of overfitting while reducing

the omission of potential clinical confounders. The candidate

variables meeting these criteria were age, KPS score, EGFR-TKI

generation, presence of extracranial metastases and primary tumor

control.

The ‘Enter’ method was used, wherein all selected

variables were simultaneously entered into the model to avoid the

instability associated with stepwise selection. Multicollinearity

among the included variables was assessed using the variance

inflation factor (VIF), with all VIF values being <2.0,

indicating no significant collinearity. The proportional hazards

(PH) assumption for all variables in the final model was analyzed

using Schoenfeld residuals (global test P=0.124). Furthermore, the

scaled Schoenfeld residuals for each variable were visually

inspected and indicated no clear pattern over time, confirming that

the PH assumption was not violated. Therefore, no corrective

measures, such as stratification or time-dependent covariates, were

necessary.

Due to the retrospective nature of the present

study, a pre-hoc sample size calculation was not performed and the

cohort included all consecutive eligible patients during the

present study period. However, a post hoc power analysis was

conducted using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich Heine

University) for the primary multivariable Cox model. With a sample

size of 260, α level of 0.05 and the observed hazard ratio (HR) for

EGFR-TKI generation (HR=7.155), the achieved statistical power was

>99%, indicating sufficient power to detect this clinically

significant effect. The Cox proportional hazards regression model

was used for multifactorial analysis to identify statistically

significant prognostic factors. The AUC for each scoring system was

derived from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The

predictive capabilities of the four scoring systems for survival

were compared at 1, 2 and 3 years in patients with BM. Statistical

significance of differences in the AUC between the Lung-mol GPA and

other models was analyzed using the DeLong test. The calibration of

the prognostic models was assessed with calibration plots and

quantitatively using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test

(26). To quantify the incremental

predictive benefit of the Lung-mol GPA over other models, the

present study calculated the Continuous Net Reclassification

Improvement (NRI) (27).

Between-group comparisons of categorical baseline characteristics

in Table SI were performed using

χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical characterization

The present study included 260 patients, with 108

aged ≥60 years and 152 aged <60 years. Of these, 122 were men

and 138 were women. The basic characteristics of the 260 patients

are detailed in Table I.

Baseline characteristics stratified by

first-line TKI generation

To assess the comparability of key patient groups,

baseline characteristics were stratified according to the

generation of the first-line EGFR-TKI administered. As detailed in

Table SI, the 136 patients who

received first- or second-generation TKIs and the 124 patients who

received third-generation TKIs were well balanced across all

recorded prognostic factors, including age, sex, KPS score, smoking

history, EGFR mutation type, number of BM, presence of extracranial

metastases, primary tumor control status and receipt of cranial

radiotherapy (all P>0.05). This balance strengthens the validity

of comparing outcomes between these treatment strategies.

Analysis of factors influencing

prognosis

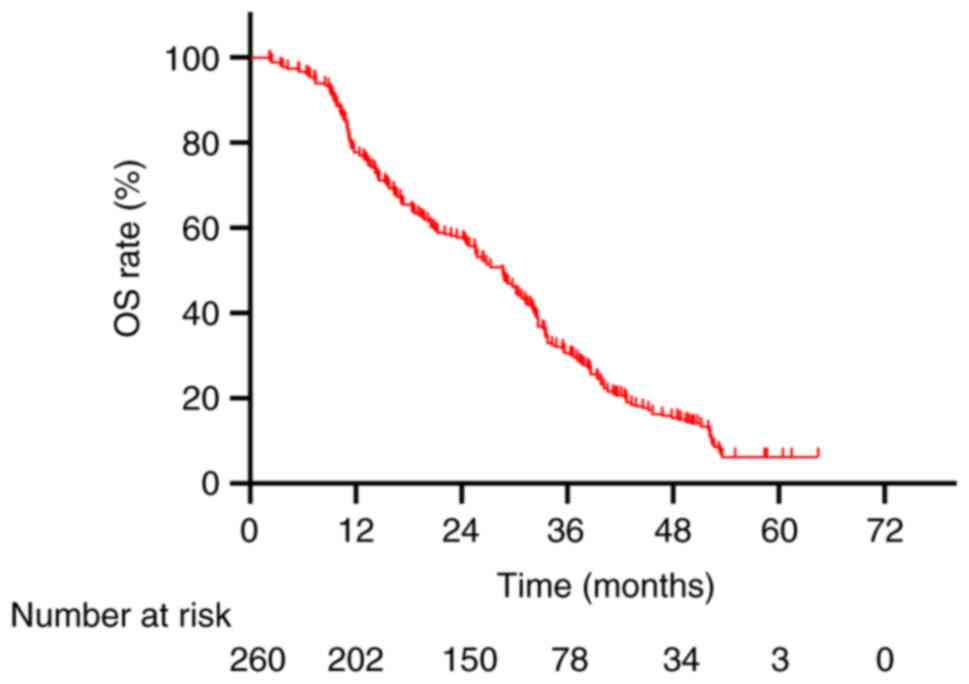

As of the follow-up cut-off date, the median

follow-up time for the entire cohort, calculated using the reverse

Kaplan-Meier method, was 58.0 months (95% CI, 54.2–61.8). The

median OS for the 260 patients was 28.7 months (95% CI, 26.0–31.4).

The 1-, 2- and 3-year OS rates were 77.7, 57.7 and 30.0%,

respectively (Fig. 1). Univariate

analysis demonstrated that age, KPS score, type of EGFR-TKIs used,

presence of extracranial metastasis and primary tumor control were

significantly associated with patient prognosis (P<0.05;

Table II). The multivariate Cox

analysis identified a KPS score <80, treatment with first- or

second-generation EGFR-TKIs and the presence of extracranial

metastases as independent prognostic risk factors for patients with

BM secondary to radical radiotherapy for EGFR-mutated lung

adenocarcinoma (Table II).

| Table II.Univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analysis for overall survival. |

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate Cox

regression analysis for overall survival.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multifactorial Cox

analysis |

|---|

|

Characteristica | Number of patients

(%) |

|

|

|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<60 | 152 (58.5) | 1.000 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

≥60 | 108 (41.5) | 1.614 | 1.238–2.104 |

<0.001b | 1.154 | 0.854–1.557 | 0.351 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 122 (46.9) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Female | 138 (53.1) | 1.002 | 0.773–1.299 | 0.986 | - | - | - |

| KPS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥80 | 162 (62.3) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

<80 | 98 (37.7) | 6.845 | 4.967–9.434 |

<0.001b | 2.706 | 1.825–4.012 |

<0.001b |

| Smoking

history |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 140 (53.8) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Yes | 120 (46.2) | 1.11 | 0.857–1.439 | 0.429 | - | - | - |

| EGFR mutation

type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Exon 19

deletion | 139 (53.5) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

L858R | 121 (46.5) | 1.129 | 0.871–1.463 | 0.364 | - | - | - |

| EGFR-TKIs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Generation III | 124 (47.7) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

Generation I/II | 136 (52.3) | 10.277 | 7.407–14.258 |

<0.001b | 7.155 | 4.950–10.344 |

<0.001b |

| BM, n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1-3 | 188 (72.3) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

>3 | 72 (27.7) | 1.283 | 0.950–1.734 | 0.104 | - | - | - |

| Extracerebral

metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No | 162 (62.3) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

Yes | 98 (37.7) | 6.436 | 4.644–8.920 |

<0.001b | 2.296 | 1.543–3.418 |

<0.001b |

| Primary tumor

control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 88 (33.8) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| No | 172 (66.2) | 1.45 | 1.093–1.923 | 0.01b | 1.021 | 0.757–1.378 | 0.889 |

| Cranial RT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 219 (84.2) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| No | 41 (15.8) | 1.068 | 0.753–1.515 | 0.711 | - | - | - |

| Radiotherapy

type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SRS | 158 (60.8) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

WBRT | 61 (23.4) | 1.228 | 0.865–1.908 | 0.137 | - | - | - |

| Receipt of any

subsequent systemic therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes | 201 (77.3) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| No | 59 (22.7) | 1.196 | 0.769–2.014 | 0.283 | - | - | - |

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses for

post-BM treatments

Acknowledging that subsequent therapies may

influence survival analysis, additional statistical evaluations

were performed. First, a sensitivity analysis was performed by

incorporating ‘Radiotherapy_type’ (SRS vs. WBRT) as a covariate

into the primary multivariable Cox model for the entire cohort. The

results confirmed that the three key independent prognostic

factors: KPS <80 (HR, 2.706; 95% CI, 1.825–4.012; P<0.001),

presence of extracranial metastasis (HR, 2.296; 95% CI,

1.543–3.418; P<0.001) and use of first-/second-generation

EGFR-TKIs (HR, 7.155; 95% CI, 4.950–10.344; P<0.001) remained

highly significant, with minimal change in their HRs (Table II). Second, to isolate the

prognostic effect of clinical factors from the influence of

first-line third-generation TKI use, a subgroup analysis was

performed. A separate multivariable Cox regression was performed

exclusively for the 136 patients treated with

first-/second-generation TKIs. As shown in Table III, within this subgroup, KPS

<80 (HR, 5.415; 95% CI, 1.269–9.640; P<0.001) and presence of

extracranial metastasis (HR, 3.484; 95% CI, 0.813–5.747;

P<0.001) remained strong independent predictors of worse

survival, whereas the number of BM and age were not retained in the

final model. Recognizing that subsequent treatment lines could

confound the survival analysis, the patterns of subsequent systemic

therapy between the first-/second-generation and third-generation

TKI groups were compared. Patients in the first-/second-generation

TKI group received a greater median number of subsequent therapy

lines (2 vs. 1) and were more likely to receive at least one

subsequent line of treatment (85.3 vs. 68.5%; P<0.001), with the

majority (71.3%) receiving a third-generation TKI upon progression

(Supplementary Table SII). A

sensitivity analysis adjusting for ‘Receipt of any subsequent

systemic therapy’ in the multivariable Cox model confirmed that the

association between first-line TKI generation and OS remained

robust.

| Table III.Multivariable Cox regression analysis

of overall survival in the subgroup of patients receiving first- or

second-generation EGFR-TKIs as first-line therapy (n=136). |

Table III.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis

of overall survival in the subgroup of patients receiving first- or

second-generation EGFR-TKIs as first-line therapy (n=136).

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multifactorial Cox

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

<60 | 1.000 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

≥60 | 1.502 | 1.022–2.207 | 0.038a | 1.101 | 0.873–1.938 | 0.598 |

| KPS | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

≥80 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

<80 | 7.298 | 2.195–14.455 |

<0.001a | 5.415 | 1.269–9.640 |

<0.001a |

| Extracranial

metastasis | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

Yes | 6.351 | 2.229–13.539 |

<0.001a | 3.484 | 0.813–5.747 |

<0.001a |

| Number of brain

metastases | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

1-3 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

|

>3 | 1.521 | 1.021–2.266 | 0.039a | 1.132 | 0.869–2.042 | 0.485 |

| Primary tumor

control | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Yes | 1.000 | - | - | 1.000 | - | - |

| No | 1.802 | 0.542–2.886 | 0.006a | 1.324 | 0.427–2.368 | 0.157 |

Predictive role of brain metastasis

scoring systems

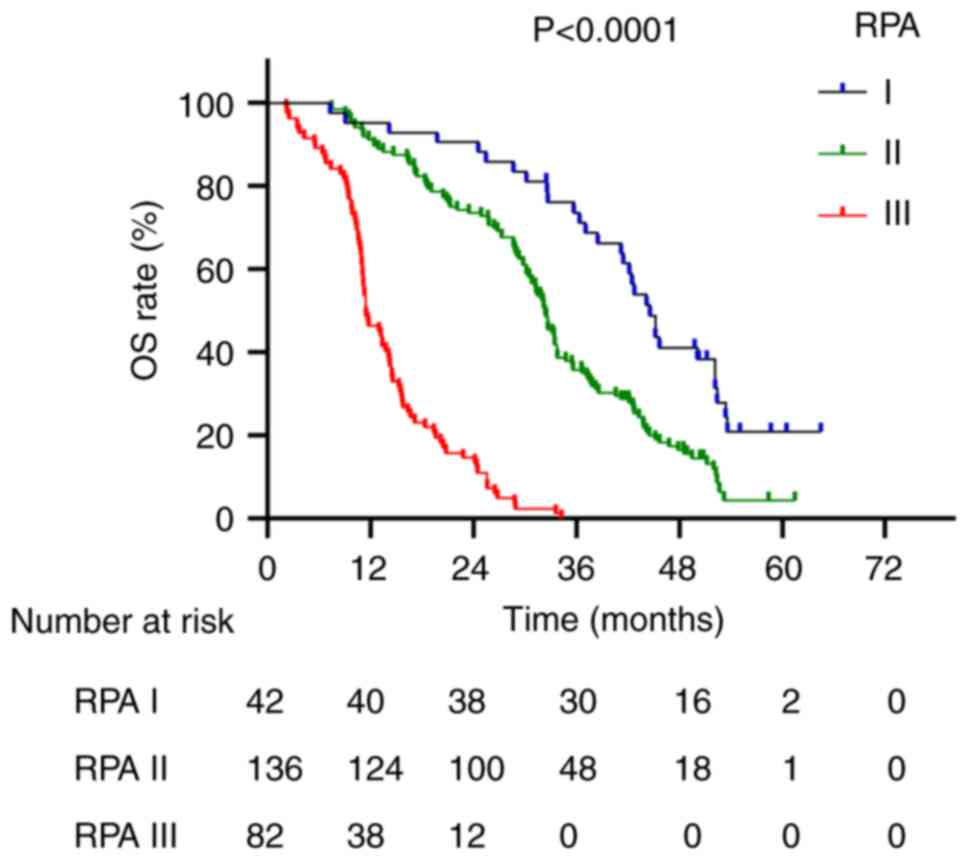

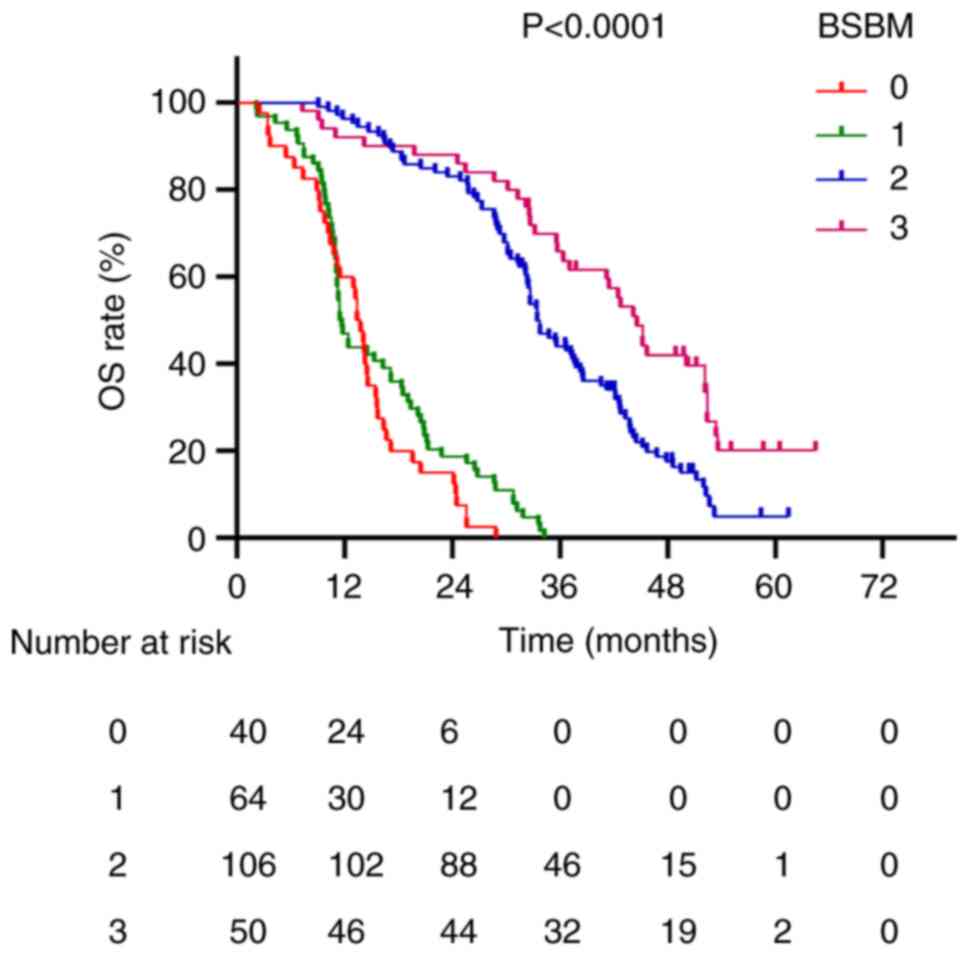

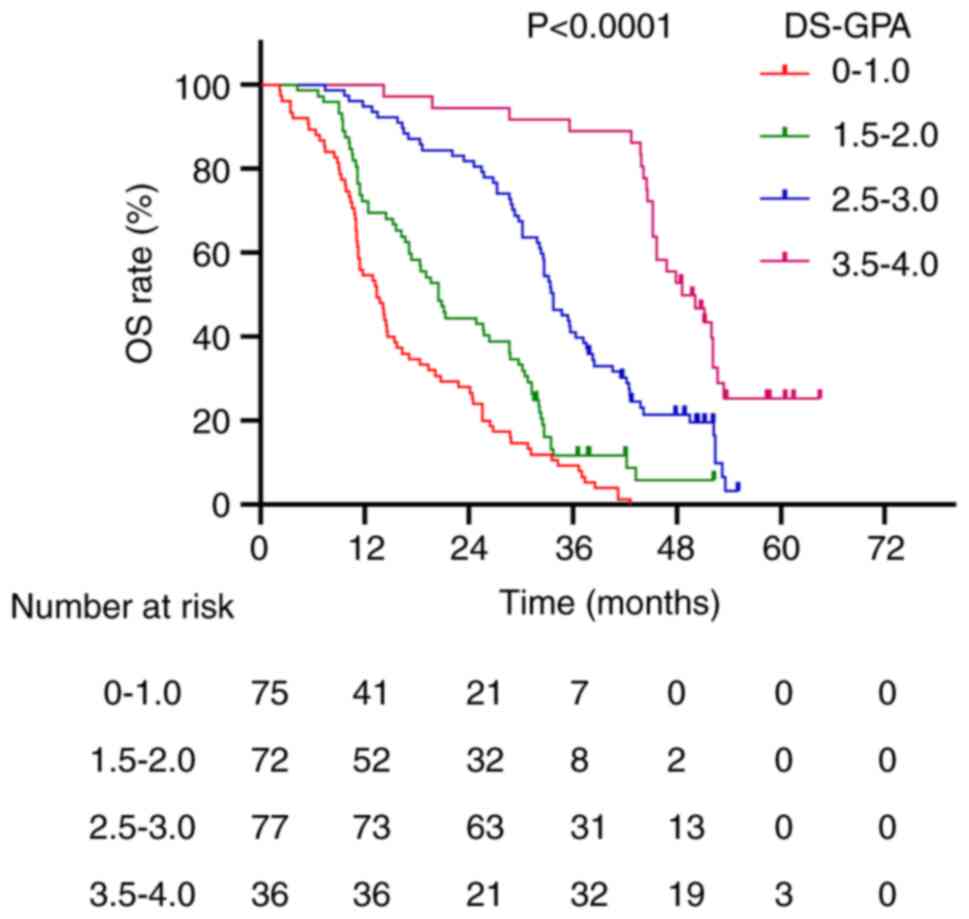

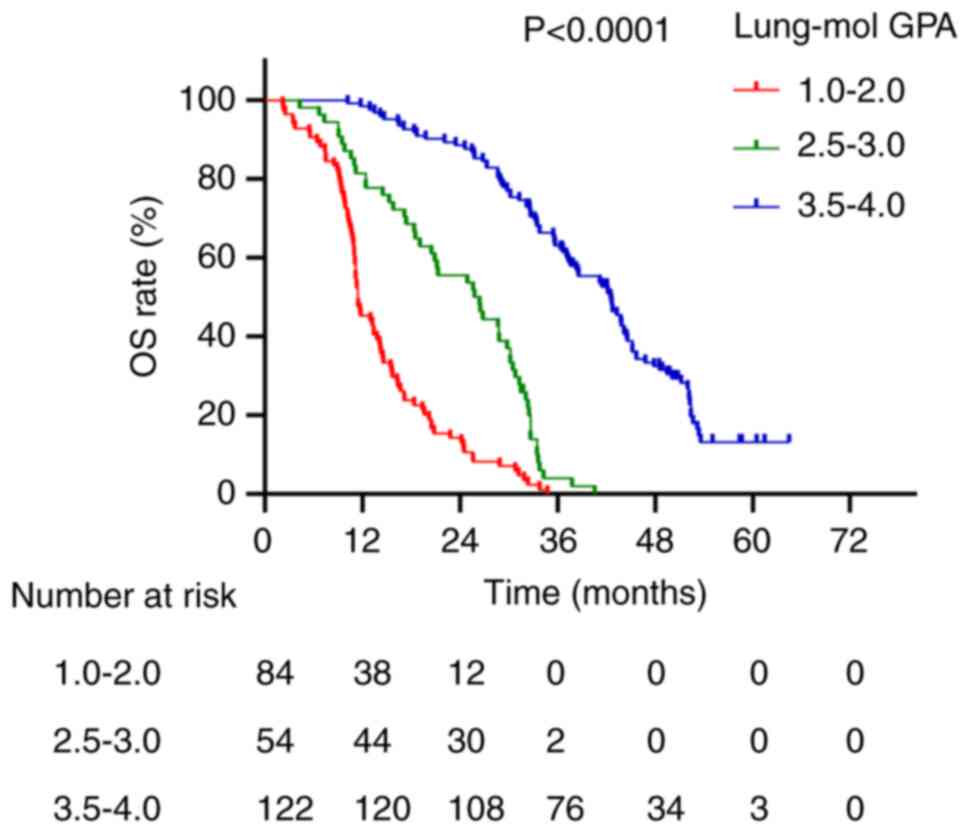

Survival curves for the four scoring systems are

presented in Figs. 2, Fig. 3, Fig.

4, Fig. 5. The median survival

times for patients with RPA grades I, II and III were 44.6, 32.4

and 11.5 months, respectively (P<0.0001; Fig. 2). For the BSBM scoring system,

median survival times for scores of 0, 1, 2 and 3 were 13.6, 11.6,

33.5 and 44.6 months, respectively (P<0.0001; Fig. 3). Patients with DS-GPA scores of

0–1.0, 1.5–2.0, 2.5–3.0 and 3.5–4.0 had median survival times of

13.4, 20.5, 33.8 and 48.6 months, respectively (P<0.0001;

Fig. 4). For the Lung-mol GPA

system, median survival times for scores of 1.0–2.0, 2.5–3.0 and

3.5–4.0 were 11.5, 26.4 and 42.5 months, respectively (P<0.0001;

Fig. 5).

Comparison of the predictive power of

brain metastasis scoring systems

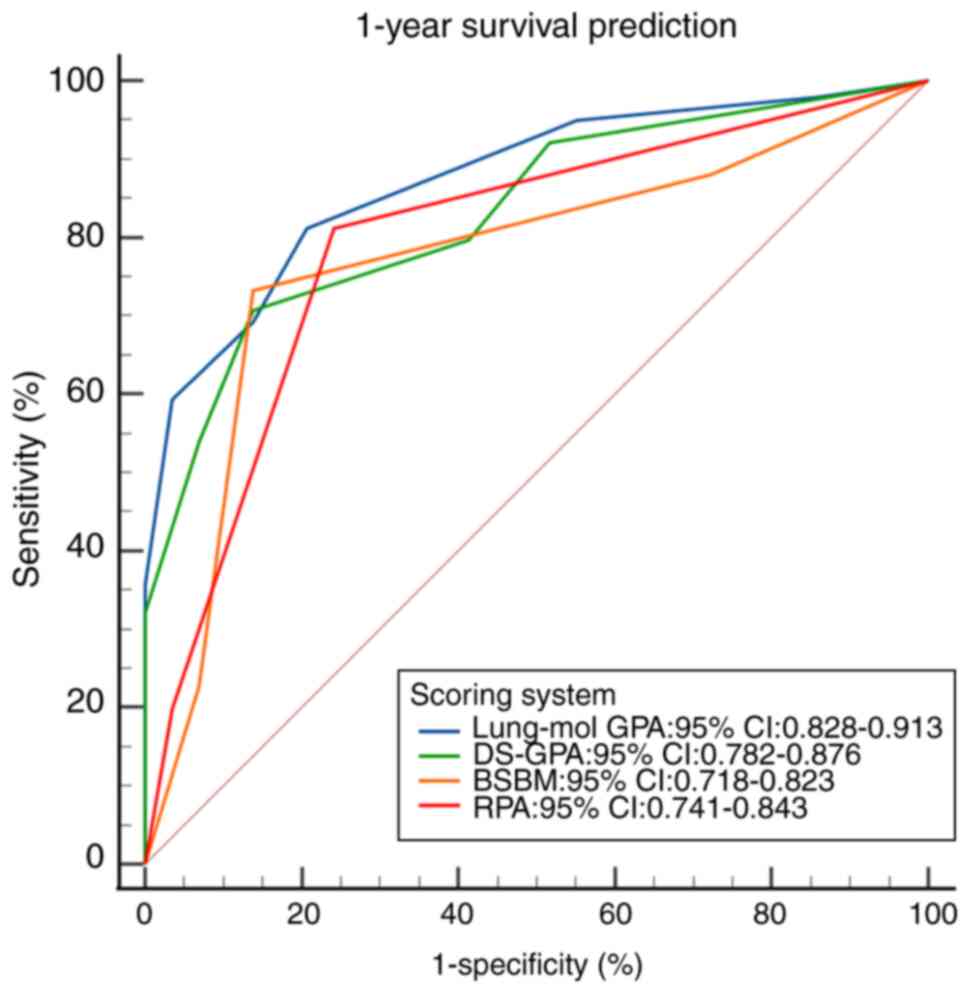

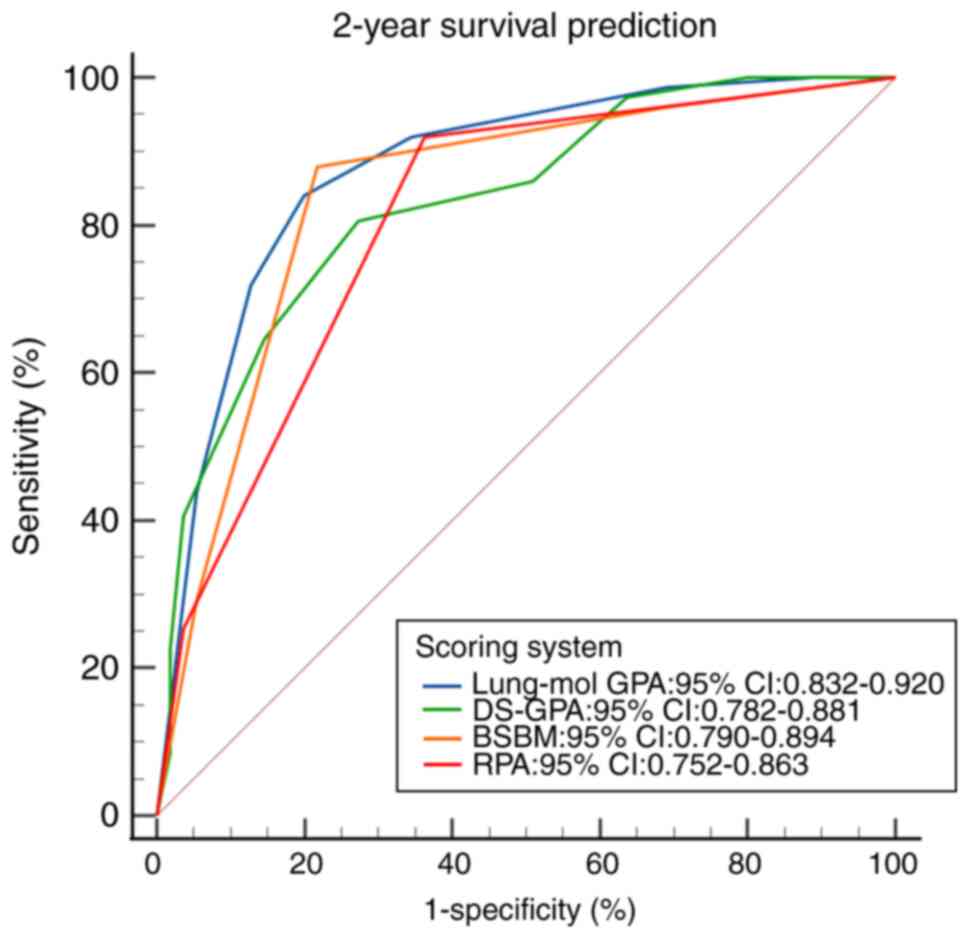

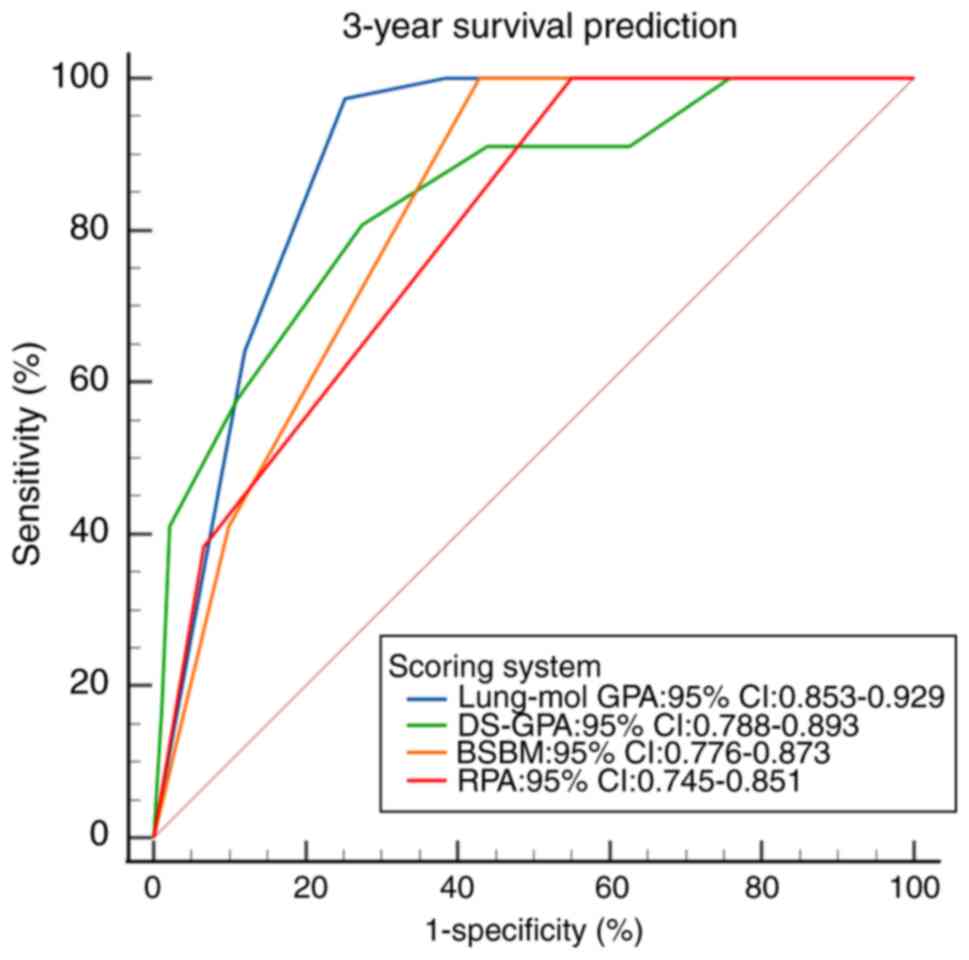

The ROC curves for the four scoring systems

predicting 1-, 2- and 3-year survival demonstrated statistical

significance (all P<0.001; Fig.

6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8). The area under the ROC curve (AUC)

comparison revealed that the Lung-mol GPA system exhibited the

highest AUC values: 0.875 (95% CI, 0.828–0.913; P<0.001), 0.876

(95% CI, 0.832–0.920; P<0.001) and 0.891 (95% CI, 0.853–0.929;

P<0.001). These values were significantly higher compared with

those of the other three scoring systems, with a statistically

significant difference (P<0.05; Table IV).

| Table IV.Prognostic performance of the scoring

systems for 1-, 2- and 3-year OS. |

Table IV.

Prognostic performance of the scoring

systems for 1-, 2- and 3-year OS.

|

| 1-year OS | 2-year OS | 3-year OS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Model | AUC | 95% CI | P-value | AUC | 95% CI | P-value | AUC | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Lung-mol GPA | 0.875 | 0.828–0.913 |

<0.001a | 0.876 | 0.832–0.920 | <0.001 | 0.891 | 0.853–0.929 |

<0.001a |

| DS-GPA | 0.833 | 0.782–0.876 |

<0.001a | 0.832 | 0.782–0.881 | <0.001 | 0.841 | 0.788–0.893 |

<0.001a |

| BSBM | 0.773 | 0.718–0.823 |

<0.001a | 0.842 | 0.790–0.894 | <0.001 | 0.824 | 0.776–0.873 |

<0.001a |

| RPA | 0.795 | 0.741–0.843 |

<0.001a | 0.808 | 0.752–0.863 | <0.001 | 0.798 | 0.745–0.851 |

<0.001a |

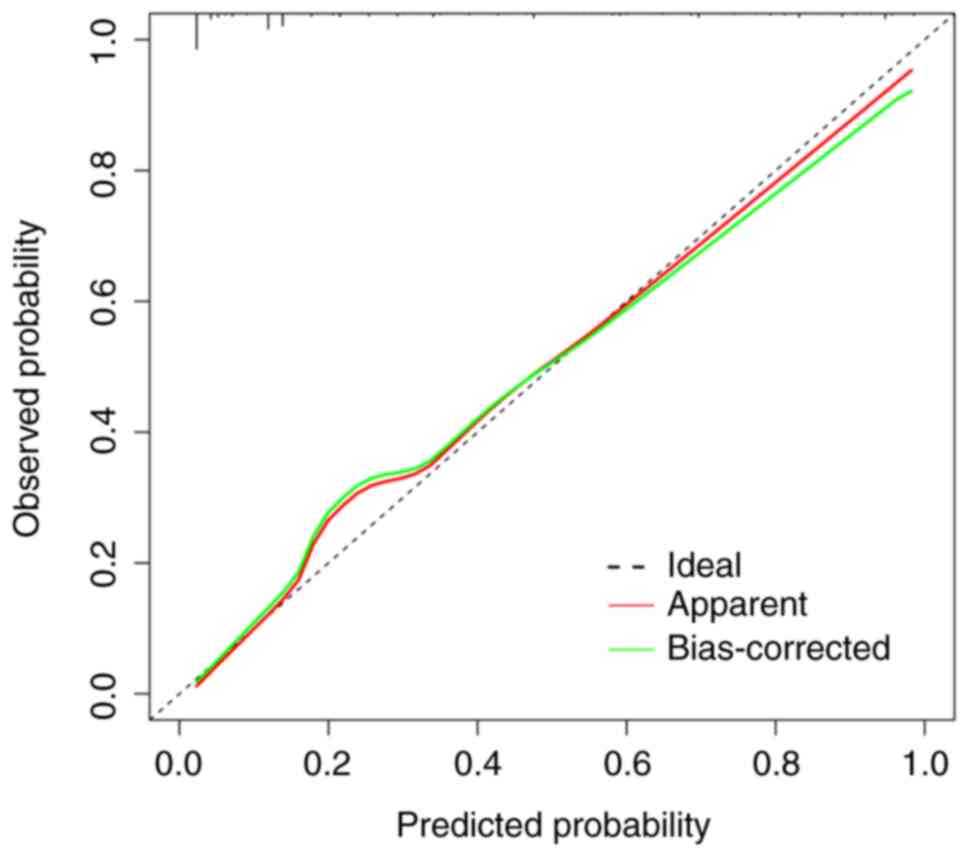

Comprehensive comparison of prognostic

models

The comparison of AUC values for predicting 1-, 2-

and 3-year survival, along with the results of the DeLong test, is

shown in Table V. The Lung-mol GPA

model consistently demonstrated significantly increased

discriminatory ability compared with the other three models across

all time points (all P<0.05). The calibration plot for the

Lung-mol GPA model at 2 years is presented in Fig. 9. Visual inspection revealed strong

agreement between predicted and observed outcomes, which was

quantitatively supported by a non-significant Hosmer-Lemeshow test

(χ2=6.952; P=0.443; Table

SIII), indicating no statistically significant deviation from

perfect calibration. NRI analysis was performed to assess the

improvement provided by the Lung-mol GPA. For 2-year survival

prediction, the NRI for upgrading to the Lung-mol GPA model from

the DS-GPA model was 0.325 (95% CI, 0.152–0.498; P<0.001;

Table SIII), indicating a

significant and clinically relevant improvement in the accurate

reclassification of patient risk.

| Table V.Pairwise comparison of the Lung-mol

GPA model with other prognostic systems using the DeLong test. |

Table V.

Pairwise comparison of the Lung-mol

GPA model with other prognostic systems using the DeLong test.

| Comparison | Time point,

year | AUC (Lung-mol

GPA) | AUC (other

model) | AUC difference | 95% CI for

difference | Z statistic | P-value |

|---|

| Lung-mol GPA

vs. | 1 | 0.875 | 0.833 | 0.042 | 0.007–0.076 | 2.373 | 0.018a |

| DS-GPA | 2 | 0.876 | 0.832 | 0.044 | 0.009–0.079 | 2.461 | 0.014a |

|

| 3 | 0.891 | 0.841 | 0.050 | 0.002–0.097 | 2.062 | 0.039a |

| Lung-mol GPA

vs. | 1 | 0.875 | 0.773 | 0.102 | 0.059–0.143 | 4.766 |

<0.001a |

| BSBM | 2 | 0.876 | 0.842 | 0.034 | 0.000–0.068 | 1.970 | 0.049a |

|

| 3 | 0.891 | 0.824 | 0.067 | 0.022–0.111 | 2.944 | 0.003a |

| Lung-mol GPA

vs. | 1 | 0.875 | 0.795 | 0.080 | 0.030–0.129 | 3.194 | 0.001a |

| RPA | 2 | 0.876 | 0.808 | 0.068 | 0.027–0.109 | 3.281 | 0.001a |

|

| 3 | 0.891 | 0.798 | 0.093 | 0.046–0.139 | 3.951 |

<0.001a |

Discussion

The prognosis for patients with BM from lung cancer

remains poor, despite advances in diagnostic and therapeutic

techniques that have improved the detection of BM and extended

survival (28,29). Previous studies investigating

prognostic factors and validating scoring systems for NSCLC BM

included a heterogeneous patient population (30–32),

encompassing those who received multiple treatments, such as

surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, before the development of

BM, as well as those diagnosed with BM at initial presentation who

did not undergo treatment. The varied prognoses at different

treatment stages and the inclusion of these diverse patient groups

may have introduced notable biases into the study outcomes. To

address this, the present study specifically focused on patients

with inoperable, locally advanced lung adenocarcinoma secondary to

BM following radical radiotherapy at initial diagnosis and EGFR

mutation, thereby eliminating potential confounding factors.

The present study retrospectively analyzed the

prognostic factors of patients with BM secondary to radical

radiotherapy for EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma and evaluated the

effectiveness of the RPA, DS-GPA, BSBM and Lung-mol GPA scoring

systems. The median OS for the 260 patients in the present study

was 28.7 months. This contrasts with the findings of Li et

al (33), who applied the same

scoring systems to Chinese patients with BM from EGFR-mutated lung

cancer, reporting a median survival time of 24.0 months. It is key

to note that the associations identified in the present

retrospective analysis, while robust within the present study

cohort, should be interpreted as observational and do not imply

causality. The findings require validation in prospective,

multi-institutional settings to establish their generalizability.

In the present study, prognostic factors influencing patient

outcomes were analyzed and demonstrated that the KPS score, the

presence of extracranial metastases and the type of EGFR-TKIs used

were independently significant in the multivariable Cox analysis.

The KPS score and the presence of extracranial metastases, key

indices in prior prognostic models (19,21–23),

were also independently significant in the present study. Lower KPS

scores were associated with worse patient outcomes. Zhang et

al (34) indicated that

patients with KPS scores of 80–100 had improved OS compared with

those patients with KPS <80. To the best of our knowledge, all

BM prediction models have associated KPS with survival duration

(35,36). The present study findings aligned

with the established role of KPS and further supported that a KPS

<80 is an independent prognostic risk factor for patients with

BM from EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma.

Patients with concurrent extracranial metastases

often have a larger tumor burden, higher malignancy and worse

therapeutic outcomes, typically indicating a worse prognosis

(37,38). Higaki et al (39) identified concurrent extracranial

metastases as an independent risk factor affecting prognosis in a

study of 294 patients with BM from EGFR-mutated NSCLC. This finding

supported the inclusion of extracranial metastasis as a criterion

in multiple prediction models (40). Furthermore, in the present study

cohort, the use of third-generation EGFR-TKIs was associated with

significantly improved patient survival and emerged as an

independent prognostic factor in the present study model. In the

FLAURA study, first-line treatment with osimertinib in patients

with EGFR gene-sensitive mutation-positive NSCLC BM demonstrated a

median PFS markedly increased to that of first-generation

EGFR-TKIs. The domestic AENEAS and FURLONG studies also reported

that third-generation EGFR-TKIs provided a notable PFS advantage

over first/second-generation treatments (41–43).

Beyond its prognostic accuracy, the Lung-mol GPA

model holds considerable potential in guiding clinical

decision-making in the future. The present study findings suggested

that risk stratification using this model could potentially inform

the tailoring of therapeutic strategies. For example, patients

classified into the most favorable prognostic group (Lung-mol GPA

3.5–4.0) have a median survival >40 months. In the Lung-mol GPA

3.5–4.0 group, there is strong justification to implement

aggressive local control strategies, such as SRS, aimed at

achieving long-term intracranial disease control while minimizing

neurocognitive toxicity. By contrast, for patients in the poorest

prognostic group (Lung-mol GPA 1.0–2.0), with a median survival of

<12 months, clinical focus may justifiably shift towards

optimizing systemic therapy, ensuring optimal symptom control and

discussing goals of care, as the potential benefits of intensive

local interventions may be limited, to the best of our knowledge.

Thus, the Lung-mol GPA scoring system can potentially serve as a

valuable tool in adjusting treatment intensity according to

individual patient prognosis in the future.

The validation of the RPA, DS-GPA, BSBM and Lung-mol

GPA brain metastasis scoring systems was conducted in the present

study. Survival curve analysis of these systems indicated that all

four models effectively differentiate patient prognostic outcomes.

However, no significant difference in prognosis was observed

between patients scoring 0 and 1 in the BSBM system. This may be

attributed to the relatively small number of cases with scores of 0

and 1, which were insufficient to demonstrate a significant

difference. By contrast, significant prognostic differences were

observed in the remaining scoring systems when compared within

their respective groups. Further comparison of the prognostic

predictive ability of the four scoring systems was performed using

ROC curves, which revealed that the AUC of the Lung-mol GPA model

was the highest, significantly surpassing the other three models.

This suggested that the Lung-mol GPA model may be the most accurate

prognostic prediction tool for this specific patient population in

the present study. Li et al (33) also compared prognostic scoring

systems in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer with BM and

concluded that the Lung-mol GPA model was notably enhanced compared

with the other three systems.

The present study had several limitations inherent

to its retrospective and single-center design. First, the lack of

systematically collected data on patient-reported outcomes,

neurocognitive function and treatment-related adverse events (for

example, as graded by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events) precludes a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis of the

treatment strategies. Similarly, the absence of a centralized

neuroradiological review to determine intracranial objective

response rates prevented an analysis of how the depth of

intracranial response associates with survival. Second, although

efforts were made to control for confounding factors using

sensitivity and subgroup analyses, residual bias due to unmeasured

or imperfectly adjusted factors cannot be excluded. Notably, while

the present study accounted for the receipt of subsequent therapy,

data on the precise timing, sequence and efficacy of subsequent

treatment lines were not fully available. Furthermore, although

corticosteroid use was similar between groups at baseline,

unmeasured variations in the total duration and tapering schedules

of corticosteroids may potentially influence both performance

status and survival. Third, the generalizability of the present

study findings may be limited by the exclusive focus on patients

with lung adenocarcinoma with a specific disease trajectory (brain

as the first site of metastasis after radical radiotherapy). Thus,

the results may not be directly applicable to other NSCLC

histological subtypes or patients with different patterns of

disease recurrence. Lastly, the present study was designed to

validate composite prognostic models rather than to assess the

individual prognostic weight of each potential variable. Therefore,

the present analysis was not powered to explore the specific roles

of factors such as the number of BM or the EGFR mutation subtype

(19DEL vs. L858R), which warrant investigation in future,

larger-scale studies.

In summary, within a well-defined cohort of patients

with EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma and BM, the present

retrospective analysis identified that a lower KPS score, the

presence of extracranial metastases and the use of

earlier-generation EGFR-TKIs were independently associated with

worse OS. Among the prognostic models assessed, the Lung-mol GPA

scoring system exhibited notably increased predictive accuracy for

survival in this patient population. These findings suggested that

the Lung-mol GPA model may potentially enhance prognostic

stratification in this clinical context. However, due to the

inherent limitations of the retrospective design, the present study

results should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating regarding

prognostic associations rather than as evidence of causality. The

external validity of the present study conclusions requires

validation in larger, prospective, multi-institutional studies

incorporating patient-centered endpoints, such as quality of life

and neurocognitive function, alongside survival in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Self-funded Project under

the Key Research and Development Program of Cangzhou City (grant

no. 23244102170).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JM completed the data analysis and paper writing. XY

was responsible for the research design and guided the revision of

the paper. JH contributed to the present study design and provided

essential data analysis support. YZ and LG recruited the enrolled

cases and contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of the

data. JM and XY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics

Committee of the Cangzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional

Chinese and Western Medicine-Hebei Province (approval no.

CZX2024180; Cangzhou, China). Each patient provided written

informed consent for participation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

|

BM

|

brain metastases

|

|

BSBM

|

basic score for BM

|

|

DS-GPA

|

diagnosis-specific graded prognostic

assessment

|

|

EGFR

|

epidermal growth factor receptor

|

|

TKIs

|

tyrosine kinase inhibitors

|

|

KPS

|

Karnofsky Performance Status

|

|

Lung-mol GPA

|

lung cancer-associated molecular

graded prognostic assessment

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

RPA

|

recursive partitioning analysis

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang B, Guo H, Xu H, Yu H, Chen Y and Zhao

G: Research progress and challenges in the treatment of central

nervous system metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Cells.

10:26202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mulshine JL, Pyenson B, Healton C, Aldige

C, Avila RS, Blum T, Cham M, de Koning HJ, Fain SB, Field JK, et

al: Paradigm shift in early detection: Lung cancer screening to

comprehensive CT screening. Eur J Cancer. 218:1152642025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li Y, Yan B and He S: Advances and

challenges in the treatment of lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother.

169:1158912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lahiri A, Maji A, Potdar PD, Singh N,

Parikh P, Bisht B, Mukherjee A and Paul MK: Lung cancer

immunotherapy: Progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol Cancer.

22:402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

McLouth LE, Gabbard J, Levine BJ, Golden

SL, Lycan TW, Petty WJ and Weaver KE: Prognostic awareness,

palliative care use, and barriers to palliative care in patients

undergoing immunotherapy or chemo-immunotherapy for metastatic lung

cancer. J Palliat Med. 26:831–836. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Seute T, Leffers P, ten Velde GP and

Twijnstra A: Neurologic disorders in 432 consecutive patients with

small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 100:801–806. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Maldonado F, Gonzalez-Ling A, Oñate-Ocaña

LF, Cabrera-Miranda LA, Zatarain-Barrón ZL, Turcott JG,

Flores-Estrada D, Lozano-Ruiz F, Cacho-Díaz B and Arrieta O:

Prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with high-risk

metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: Quality of life and

neurocognitive analysis of a randomized phase II study. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 111:81–92. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rangachari D, Yamaguchi N, VanderLaan PA,

Folch E, Mahadevan A, Floyd SR, Uhlmann EJ, Wong ET, Dahlberg SE,

Huberman MS and Costa DB: Brain metastases in patients with

EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancers. Lung

Cancer. 88:108–111. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wu F, Fan J, He Y, Xiong A, Yu J, Li Y,

Zhang Y, Zhao W, Zhou F, Li W, et al: Single-cell profiling of

tumor heterogeneity and the microenvironment in advanced non-small

cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 12:25402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lim ZF and Ma PC: Emerging insights of

tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance mechanisms in lung cancer

targeted therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 12:1342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pan K, Concannon K, Li J, Zhang J, Heymach

JV and Le X: Emerging therapeutics and evolving assessment criteria

for intracranial metastases in patients with oncogene-driven

non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:716–732. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pike LRG, Miao E, Boe LA, Patil T, Imber

BS, Myall NJ, Pollom EL, Hui C, Qu V, Langston J, et al: Tyrosine

kinase inhibitors with and without up-front stereotactic

radiosurgery for brain metastases from EGFR and ALK oncogene-driven

non-small cell lung cancer (TURBO-NSCLC). J Clin Oncol.

42:3606–3617. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jünger ST, Schödel P, Ruess D, Ruge M,

Brand JS, Wittersheim M, Eich ML, Schmidt NO, Goldbrunner R, Grau S

and Proescholdt M: Timing of development of symptomatic brain

metastases from non-small cell lung cancer: Impact on symptoms,

treatment, and survival in the era of molecular treatments. Cancers

(Basel). 12:36182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lancia A, Merizzoli E and Filippi AR: The

8th UICC/AJCC TNM edition for non-small cell lung cancer staging:

Getting off to a flying start? Ann Transl Med. 7 (Suppl

6):S2052019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Moon SW, Choi SY and Moon MH: Effect of

invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma on lung cancer-specific survival

after surgical resection: A population-based study. J Thorac Dis.

10:3595–3608. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li J, Zhang X, Wang Y, Jin Y, Song Y and

Wang T: Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of

synchronous brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer

compared with metachronous brain metastases. Front Oncol.

14:14007922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Williams TM, Miller E, Welliver M,

Brownstein J, Otterson G, Owen D, Haglund K, Shields P, Bertino E,

Presley C, et al: A phase 2 trial of primary tumor stereotactic

body radiation therapy boost before concurrent chemoradiation for

locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys. 120:681–694. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, Asbell S,

Phillips T, Wasserman T, McKenna WG and Byhardt R: Recursive

partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three

radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) brain metastases trials.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 37:745–751. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Frappaz D, Bonneville-Levard A, Ricard D,

Carrie S, Schiffler C, Xuan KH and Weller M: Assessment of

Karnofsky (KPS) and WHO (WHO-PS) performance scores in brain tumour

patients: The role of clinician bias. Support Care Cancer.

29:1883–1891. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lorenzoni J, Devriendt D, Massager N,

David P, Ruíz S, Vanderlinden B, Van Houtte P, Brotchi J and

Levivier M: Radiosurgery for treatment of brain metastases:

Estimation of patient eligibility using three stratification

systems. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 60:218–224. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sperduto PW, Kased N, Roberge D, Xu Z,

Shanley R, Luo X, Sneed PK, Chao ST, Weil RJ, Suh J, et al: Summary

report on the graded prognostic assessment: An accurate and facile

diagnosis-specific tool to estimate survival for patients with

brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 30:419–425. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sperduto PW, Yang TJ, Beal K, Pan H, Brown

PD, Bangdiwala A, Shanley R, Yeh N, Gaspar LE, Braunstein S, et al:

Estimating survival in patients with lung cancer and brain

metastases: An update of the graded prognostic assessment for lung

cancer using molecular markers (lung-molGPA). JAMA Oncol.

3:827–831. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cho A, Gatterbauer B, Chen Y, Jankowski T,

Haider L, Tögl S, Kapfhammer I, Schreder M, Kirchbacher K,

Zöchbauer-Müller S, et al: Effect of cumulative dexamethasone dose

on the outcome of patients with radiosurgically treated brain

metastases in the era of modern oncological therapy. J Neurosurg.

143:384–395. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gillespie BW, Chen Q, Reichert H,

Franzblau A, Hedgeman E, Lepkowski J, Adriaens P, Demond A,

Luksemburg W and Garabrant DH: Estimating population distributions

when some data are below a limit of detection by using a reverse

Kaplan-Meier estimator. Epidemiology. 21 (Suppl 4):S64–S70. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Surjanovic N, Lockhart RA and Loughin TM:

A generalized Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for a family of

generalized linear models. Test (Madr). 33:589–608. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Jewell ES, Maile MD, Engoren M and Elliott

M: Net reclassification improvement. Anesth Analg. 122:818–824.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Schröder C, Windisch P, Lütscher J,

Zwahlen DR and Förster R: Validation and discussion of clinical

practicability of the 2022 graded prognostic assessment for NSCLC

adenocarcinoma patients with brain metastases in a routine clinical

cohort. Front Oncol. 13:10425482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chinese Association for Clinical

Oncologists; Medical Oncology Branch of Chinese International

Exchange and Promotion Association for Medical and Healthcare, .

Clinical practice guideline for brain metastases of lung cancer in

China (2021 version). Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 43:269–281.

2021.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rades D, Hansen HC, Schild SE and Janssen

S: A new diagnosis-specific survival score for patients to be

irradiated for brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung. 197:321–326. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sperduto PW, De B, Li J, Carpenter D,

Kirkpatrick J, Milligan M, Shih HA, Kutuk T, Kotecha R, Higaki H,

et al: Graded prognostic assessment (GPA) for patients with lung

cancer and brain metastases: Initial report of the small cell lung

cancer GPA and update of the non-small cell lung cancer GPA

including the effect of programmed death ligand 1 and other

prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol. 114:60–74. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J, Cagney D,

Aizer A, Lin NU, Nesbit E, Kruser TJ, Chan J, Braunstein S, et al:

Survival in patients with brain metastases: Summary report on the

updated diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment and

definition of the eligibility quotient. J Clin Oncol. 38:3773–3784.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li R, Zhang SR, Liu XF, Zhang JW, Zhao JY,

Bai P and Zhang XC: Prognostic factors for non-small cell lung

cancer patients with central nervous system metastasis with

positive driver genes. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 103:1202–1209.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang M, Tong J, Ma W, Luo C, Liu H, Jiang

Y, Qin L, Wang X, Yuan L, Zhang J, et al: Predictors of lung

adenocarcinoma with leptomeningeal metastases: A 2022

targeted-therapy-assisted molGPA model. Front Oncol. 12:9038512022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mulvenna PM, Holt T and Stephens R:

Response to ‘Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and

treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain

metastases: A multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients’. (Int

J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010:77:655-661). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 81:11942011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yamamoto M, Kawabe T, Higuchi Y, Sato Y,

Barfod BE, Kasuya H and Urakawa Y: Validity of three recently

proposed prognostic grading indexes for breast cancer patients with

radiosurgically treated brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 84:1110–1115. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Winslow N, Boyle J, Miller W, Wang Y,

Geoffroy F and Tsung AJ: Development of brain metastases in

non-small-cell lung cancer: High-risk features. CNS Oncol.

13:23958042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Schmid S, Garcia M, Zhan L, Cheng S, Khan

K, Chowdhury M, Sabouhanian A, Herman J, Walia P, Strom E, et al:

Outcomes with non-small cell lung cancer and brain-only metastasis.

Heliyon. 10:e370822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Higaki H, Nishioka K, Otsuka M, Nishikawa

N, Shido M, Minatogawa H, Nishikawa Y, Takashina R, Hashimoto T,

Katoh N, et al: Brain metastases in Japanese NSCLC patients:

Prognostic assessment and the use of osimertinib and immune

checkpoint inhibitors-retrospective study. Radiat Oncol. 18:252023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liang L, Wang Z, Duan H, He Z, Lu J, Jiang

X, Hu H, Li C, Yu C, Zhong S, et al: Survival benefits of

radiotherapy and surgery in lung cancer brain metastases with poor

prognosis factors. Curr Oncol. 30:2227–2236. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ohe Y, Imamura F, Nogami N, Okamoto I,

Kurata T, Kato T, Sugawara S, Ramalingam SS, Uchida H, Hodge R, et

al: Osimertinib versus standard-of-care EGFR-TKI as first-line

treatment for EGFRm advanced NSCLC: FLAURA Japanese subset. Jpn J

Clin Oncol. 49:29–36. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lu S, Dong X, Jian H, Chen J, Chen G, Sun

Y, Ji Y, Wang Z, Shi J, Lu J, et al: AENEAS: A randomized phase III

trial of aumolertinib versus gefitinib as first-line therapy for

locally advanced or metastaticnon-small-cell lung cancer with EGFR

exon 19 deletion or L858R mutations. J Clin Oncol. 40:3162–3171.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Shi Y, Chen G, Wang X, Liu Y, Wu L, Hao Y,

Liu C, Zhu S, Zhang X, Li Y, et al: Central nervous system efficacy

of furmonertinib (AST2818) versus gefitinib as first-line treatment

for EGFR-mutated NSCLC: Results from the FURLONG study. J Thorac

Oncol. 17:1297–1305. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|