In the past decades, the application of certain new

research methods and technologies have led to the proposal of new

treatments for cancer, mainly neoadjuvant chemotherapy and targeted

immunotherapy. Whilst they have often shown improved efficacy in

the initial clinical application, they are associated with drug

resistance and side effects (1).

Therefore, seeking complementary and alternative treatments from

traditional herbal medicine has become one new approach in the

treatment of cancer. For example, astragalin has attracted

widespread attention due to its wide availability, affordable cost,

potent anticancer activity and high safety profile. Moreover,

astragalin and its derivatives are considered to have definite

cytotoxicity (2).

Regarding the anticancer effects of astragalin,

previous studies have reported effects of astragalin on specific

cancers through in vitro and ex vivo experiments, or

network pharmacological analyses (16–18).

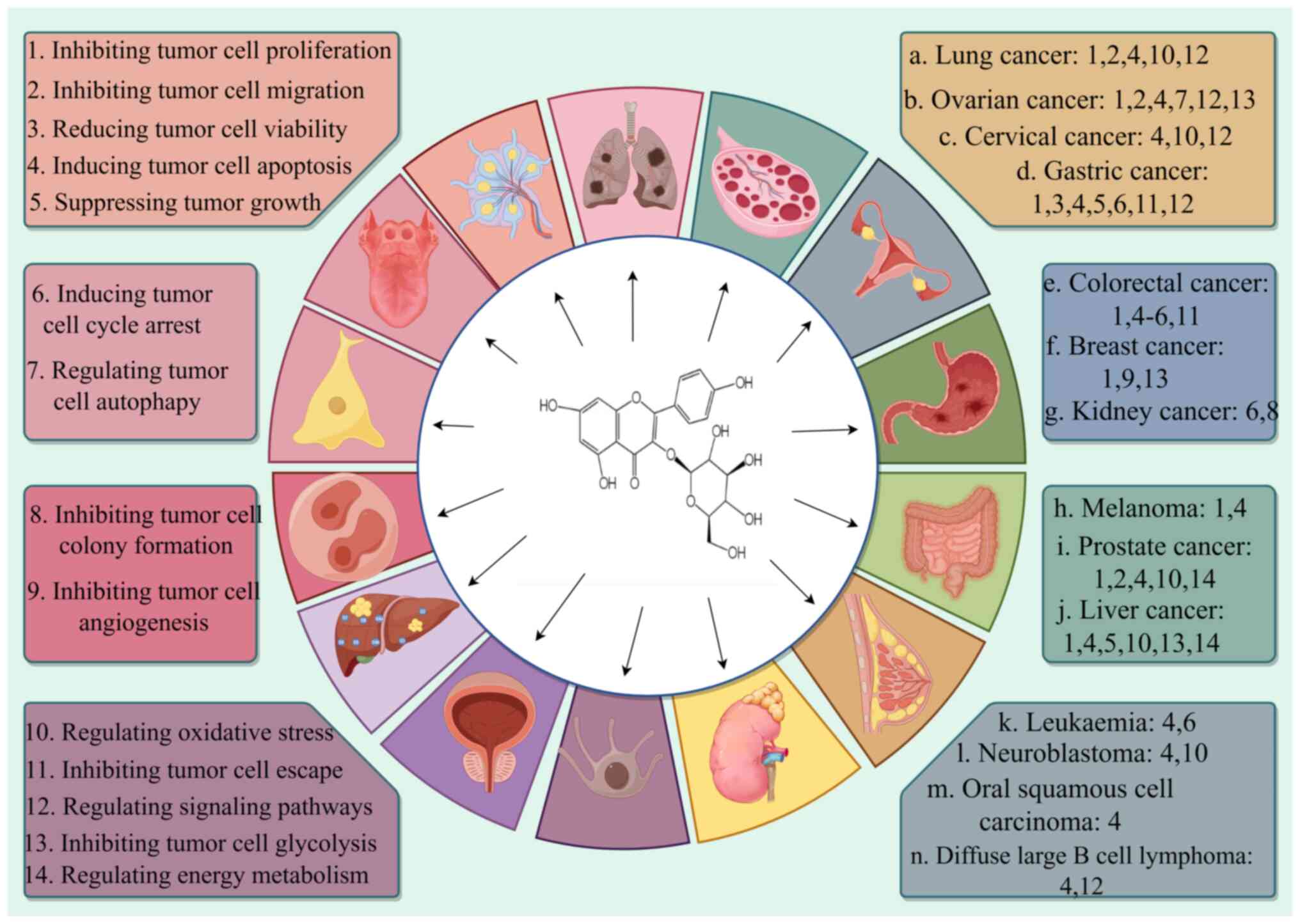

However, unlike previous literature reports on this topic, the

present paper summarizes the anticancer effects of the natural

compound Astragalin in several types of cancers, systematically

outlining the specific mechanisms of the cancer-inhibiting effects

of Astragalin, and suggesting future research directions for

Astragalin. The present paper presents a comprehensive and

systematic review of the mechanism of action of astragalin and its

derivatives in several cancers, with an in-depth exploration to

elucidate the potential and possibilities of astragalin for

anticancer use. Table I summarizes

the mechanism of action of astragalin on several cancers and

Fig. 2 presents the specific types

of anticancer mechanisms of astragalin.

Lung cancer poses a serious health and economic

burden to the global population, with the number of new lung cancer

cases expected to reach ~3.8 million by 2050 (19). Issues with current lung cancer

treatment include high morbidity and mortality rates, late

diagnosis, limited therapeutic options, restrictions on targeted

therapies, economic and resource constraints, tumor heterogeneity

and drug resistance (20),

nutritional and quality of life issues (21), and research and clinical

translational challenges (22).

Therefore, the option of developing novel therapeutic agents with

high safety margins may improve this situation.

Among the existing herbal medicine developments,

astragalin is expected to be a safe and reliable novel ingredient

due to its potent potency to inhibit the activity of lung cancer

cells, impede cell migration, proliferation, invasion and induce

apoptosis. Astragalin belongs to the class of lotus leaf flavonoids

(LLF), and in vitro studies (23,24)

have reported that high concentrations (500 µg/ml) of LLF can

notably induce apoptosis in human lung cancer A549 cells (25). LLF increases the content of reactive

oxygen species and the level of the oxidative end-product

malondialdehyde, and at the same time, reduces superoxide dismutase

activity. It upregulates several apoptotic factors including

caspase-3 and caspase-9, and inhibits the expression of related

factors [such as B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2], thereby achieving an anti-lung

cancer effect (25). Astragalin

acts on the JAK/STAT pathway to regulate the expression of

apoptotic factors and related genes in a dose-dependent manner,

causing damage to cellular DNA and augmenting reactive oxygen

species to promote apoptosis and inhibit migration and invasion

(26). Moreover, in vivo

studies (27,28) have reported that astragalin may

induce cell death via the aspartase, ERK-1/2, AKT and NF-κB

signaling pathways, a process that may be associated with an

increased Bax:Bcl-2 ratio (29).

Network pharmacological studies (30,31)

have also reported that astragalin treatment of lung adenocarcinoma

may exert its unique inhibitory effects on cell proliferation,

migration and apoptosis through the microRNA

(miRNA/miR)-140-3p/3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase 1

axis (32). Finally, astragalin has

been reported to act on the lung cancer A549 cell line with potent

cytotoxicity, activating effector caspase-3 and inducing apoptosis

(33).

Astragalin has been reported to inhibit cell

proliferation and migration and induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer

cells by regulating signaling pathways, affecting the expression of

specific cytokines and inhibiting the glycolytic pathway. This

effect is associated with the upregulation of prolyl hydroxylase

domain-containing protein 2 (PHD2) expression and inhibition of

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) (38,39).

PHD2 can act as an oxygen sensor and improve perfusion and

oxidization of tumor cells (40),

and participates in the programming of macrophage glycolysis

(41). HIF-1α is stabilized by

binding to hypoxia-responsive element in the anaerobic state,

activating key enzymes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1

(PDK1) and pyruvate kinase type M2, and inhibiting the

tricarboxylic acid cycle, thus shifting glucose metabolism from

oxidative phosphorylation to anaerobic glycolysis (42–44).

This metabolic reprogramming enhances cell survival. Astragalin

inhibits the phosphorylation of related proteins, whereas

3-methyladenine or bafilomycin A1, which act as autophagy

inhibitors, can reverse this process. Astragalin can also regulate

cellular autophagy by targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

(45), a classic signaling pathway

in ovarian cancer tumorigenesis, proliferation and progression

(46). Thus, astragalin may exert

its unique biological effects on ovarian cancer cells.

Cervical cancer ranks second among malignant

neoplastic diseases in women and has a high mortality rate

(47). Due to the high resistance

to platinum-based chemical drugs, this disease is now often treated

with radiotherapy (48); however,

this can cause damage to the mucosa of the vagina and urinary

tract, which can affect patient quality of life (49). Therefore, it is necessary to explore

new therapeutic methods with low toxicity and high safety.

It is conceivable that if astragalin is applied in

conjunction with radiotherapy drugs, it may be able to exert

neuroprotective effects locally, reduce the discomfort of vaginal

and urinary tract mucosa, and improve the quality of life of

patients. Astragalin inhibits cell proliferation and accelerates

the process of apoptosis in cervical cancer cells by regulating

signaling pathways and cellular oxygenation (50). Network pharmacological analysis has

reported that, in HeLa cells, astragalin can exert regulatory

effects on signaling proteins such as EGFR, STAT3 and cyclin D1,

affecting the ErbB and forkhead box protein O signaling pathways.

This induces an increase in reactive oxygen species and notably

inhibits the proliferation and promoting apoptosis in a manner that

is linearly associated with concentration (51). Moreover, astragalin, has been

reported to exhibit clear anti-cervical cancer activity (52).

Gastric cancer is a great challenge to global public

health with the fifth highest global incidence rate, the third

highest mortality rate and a high rate of metastasis (53). The molecular and phenotypic

heterogeneity of gastric cancer is particularly high (54), and >70% of patients with gastric

cancer are diagnosed at an intermediate-to-advanced stage, missing

the optimal time for treatment, with limited efficacy of

chemotherapy, targeted therapies and immunotherapy, and issues of

drug resistance and side effects (55,56).

Astragalin inhibits the activity of the drug

metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1

and, in vivo, it inhibits estradiolation to produce the

carcinogenic metabolite 4-hydroxy-estradiol (76). Furthermore, astragalin inhibits

breast cancer cell activity and proliferation and angiogenesis

(18,77). Astragalin can act on AKT, zinc

finger E-box binding homeobox 1, VEGF and matrix metallopeptidase

(MMP)9 targets to inhibit cell motility and exert anti-angiogenic

effects (18). It downregulates the

protein expression levels of glucose transporter protein (GLUT)-1,

lactate dehydrogenase A and hexokinase 2, activates AMP-activated

protein kinase (AMPK) and inhibits mTOR activity, reduces glucose

uptake, inhibits glycolysis, and inhibits cell proliferation

through the AMPK/mTOR pathway (77). Activation of the estrogen receptor

is associated with the development of >50% of invasive breast

cancers (78), and astragalin,

which exerts therapeutic effects comparable with those of hormones

with a high margin of safety, may offer new hope for clinical

application (79). Moreover,

astragalin may mainly interact with human estrogen receptor α

receptors to exert anticancer effects (80), and it can also bind to human

epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) and become a potential

inhibitor of HER2 (81). Astragalin

may also be an effective therapeutic agent for metastasized

advanced breast cancer, and this biological effect may be achieved

by reducing the expression of TNF-α, which impairs the expression

of MMP-9 (82,83).

Melanoma is an aggressive metastatic cancer, with a

5-year survival rate of only 4.6% (90). Global melanoma incidence and

mortality in 2040 will be >150% of what it was in 2020 (91). In recent years, immunotherapy and

targeted therapies have achieved a certain degree of efficacy as

the first-line recommended drugs (92); however, there is a substantial risk

of toxicity and drug resistance (93).

Astragalin is cytotoxic and capable of inducing

apoptosis. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1) is

an enzyme involved in several cancer processes, and in melanoma,

high levels of MSK1 are often accompanied by high expression of

CREB, and increased activity of the MSK1-CREB pathway promotes cell

proliferation and metastasis (94).

Astragalin directly binds to and inhibits p38 MAPK activity,

antagonizing MSK1 phosphorylation and high levels of γ-H2AX in a

time- and dose-dependent manner, thereby reducing precancerous skin

lesions (95). Astragalin has also

been reported to exert toxic effects on melanocytic tumor A375P and

SK-MEL-2 cells, increasing the levels of positive cells and sub-G1

populations, activating cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase,

inhibiting SRY-box transcription factor 10 signaling, acting on

cell cycle-related proteins and promoting apoptosis (96). Moreover, astragalin has been

reported to upregulate the expression of superoxide dismutase and

exhibit skin protection effects (97).

Astragalin has been reported to have notable

biological effects for the treatment of prostate cancer by

inhibiting cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and inducing

apoptosis (103). Astragaloside,

the most abundant component of Cyperus exaltatus var.

iwasakii (CE) secondary metabolites, modulates transcription

factors and inhibits the expression of MMP-9, thereby inhibiting

invasion, migration and proliferation of prostate cancer cells.

In vivo studies have also reported that in an allogeneic

model, CE inhibits tumor loading (104). Moreover, Jurinea

mesopotamica Hand.-Mazz. contains high levels of astragalin,

which can destroy cell organelles, promote the generation of

reactive oxygen species, increase apoptotic gene expression and

transcription, regulate energy metabolism, inhibit cell

proliferation and induce cell death (103).

Liver cancer is a common primary cancer and a

high-risk site for cancer metastasis (105). Emerging Yttrium 90 microsphere

therapy has been reported to have notable efficacy in patients with

advanced, non-surgical liver cancer (106); however, this method requires

strict pre-operative screening, is relatively expensive and

requires a high level of expertise to perform the surgery (107). By contrast, it is advantageous to

explore the development of Traditional Chinese Medicine herbal

active ingredients. For example, astragalin has been reported to

inhibit the activity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells, suppressing

their proliferation and inducing apoptosis through several

mechanisms (108–110).

With 58,903 deaths, China had the highest number of

leukemia deaths in the world in 2021 (114). Personalized treatment approaches

for leukemia have been developed; however, there are issues of

treatment resistance, long-term side effects and quality of life

(115). Several studies have

reported that Chinese herbal medicine has satisfactory therapeutic

effects on myelosuppression (116). For example, astragalin has been

reported to inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in leukemia cells

(117).

Certain researchers have isolated drug components

with anticancer activity and clarified that astragalin is its main

antileukemia component (118). The

flavonoid derivative astragalin heptaacetate (AHA) can induce cell

death through non-specific caspases. AHA has been reported to

concentrate and cleave cell chromatin under aerobic conditions,

block the cell cycle in the G0-G1 phase and affect the

mitochondrial membrane potential. It also has been reported to

regulate cytokine expression, activate MAPK, exhibit notable

cytotoxicity and induce apoptosis at the organelle level (117).

The development of NB may be associated with the

neural spine during embryonic development (119). The disease is highly malignant

(120), with >50% of patients

presenting with high-risk phenotypes (121) and a 5-year survival rate of

<50% (122). The immune

microenvironment of NB is complex, with low immunogenicity of

tumor-associated antigens and immunosuppressive factors (such as

TGF-β and IL-10), hindering the effectiveness of immunotherapy

(123). Moreover, the high

clinical behavioral heterogeneity of NB makes it more difficult to

develop standardized treatment protocols (124,125).

Previous research has reported that mutations

associated with the RAS/MAPK pathway are present in the majority of

recurrent NBs (126,127). Astragalin exhibits biological

effects on this pathway, inhibiting cell activity and inducing

apoptosis (128). Furthermore,

astragalin pretreatment reverses the cytoprotective effect, which

is associated with the inhibition of oxidative stress and

phosphorylation of MAPK, as shown by a reduction in the levels of

extracellular protein-regulated protein kinases, p38 and c-Jun

N-terminal kinase, exerting their cytotoxic effects and inducing

apoptosis in NB SK-N-SH cells (128).

Research has demonstrated that the Chinese herbal

formulation, FFBZL, composed of Scutellaria barbata D. Don,

Astragalus membranaceus and Ligusticum chuanxiong

Hort, may be used in the treatment of OSCC; therefore, its

molecular mechanisms warrant in-depth exploration. As a crucial

component, Astragalus membranaceus exhibits marked antitumor

activity in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma through its extract,

total flavonoids of Astragalus, suggesting the potential of its

active ingredients (138).

Astragalin, one of the key active components of Astragalus

membranaceus, currently lacks direct data demonstrating its

inhibitory effect on OSCC; however, network pharmacology combined

with bioinformatics analysis has revealed that six key ingredients

of FFBZL (including components from Astragalus membranaceus)

may interact with 820 potential target genes. These targets

intersect with OSCC-related target genes, generating 151 common

targets (139).

DLBCL is a common aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

that accounts for 30–40% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (140). The R-CHOP regimen (rituximab +

cyclophosphamide + adriamycin + vincristine + prednisone) is the

first-line standard of care for DLBCL. However, certain patients

still relapse after treatment or transition to refractory cases

(141).

Astragalin has been reported to induce apoptosis in

DLBCL cells by modulating cytokines (142). A previous study reported that

astragalin inhibits DLBCL OCI-LY8 cell viability and disrupts the

nucleus to promote the emergence of apoptotic vesicles by affecting

the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, upregulating the levels of p53,

caspase-3 and Bax, and inhibiting Bcl-2 expression (142).

Astragalin has notable anticancer effects in several

types of cancer. It also scavenges free radicals in the body

(143). Furthermore,

overexpression of GLUT5 has been reported to lead to marked changes

in glucose metabolism and enhance glycolysis, which is a prominent

manifestation of cancer cells. This protein is expected to be used

as a biomarker for the diagnosis of cancer and as a therapeutic

target (144). A derivative of

astragalin, astragalin-6-glucoside, has been reported to inhibit

GLUT5 (145). Certain studies

suggest that it is associated with glycolysis; however, the exact

mechanism of action is not clear (146).

Based on a review of the mechanisms of astragalin

and its derivatives against several malignant tumors, the

anticancer mechanisms of astragalin are summarized as follows: i)

Regulation of signaling pathways: Astragalin can regulate the

PI3K/AKT, MAPKs, JAK/STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways, miRNA

expression and the Notch1 pathway (27,147),

which inhibits tumor cell growth and survival (148); ii) induction of apoptosis:

Astragalin can cause loss of caspase activity, mutation of p53 gene

and imbalance in the regulation of Bcl2 protein, leading to reduced

activity and programmed death of cancer cells (149). It also affects mitochondrial

function, reduces mitochondrial membrane potential and increases

the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (150).

Notably, a study reported that astragalin ameliorated testicular

germ cell apoptosis in rats with varicocele by reducing the

expression of caspase 3 and the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (151). Moreover, astragalin reduced

intracellular oxidative stress, activated caspase 3, 7 and 9, and

promoted programmed cell death in cancer cells, whilst protecting

normal cells from oxidative damage, suggesting that it has a dual

effect on the human body (7); iii)

inhibition of cell proliferation and migration: Astragalin is

closely associated with several angiogenesis-related factors (such

as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, kinase insert domain

receptor and MMP9), revealing potential biological effects with

angiogenesis and suggesting new ideas for the treatment of tumors

in terms of reducing the number of blood vessels (152). Astragalin downregulates the

expression of specific protein factors, regulates miRNAs and

induces cell cycle arrest (26);

and iv) enhancement of drug sensitivity: In a previous study,

astragalin was administered with carboplatin and cisplatin over a

range of concentrations, and the results demonstrated that

astragalin was associated with an improved combined effect in

OVCAR-8 and SKOV-3 cells compared with carboplatin or cisplatin

alone (39). This indicates that

astragalin could enhance the accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs

in tumor cells and reverse resistance to chemotherapeutic

drugs.

Astragalin has a wide range of advantages in cancer

treatment, especially in the process of cooperating with

chemotherapeutic drugs to reduce toxicity and increase

efficiency.

For different cancer types, astragalin has varied

anticancer mechanisms of action, but there are also

cross-overlapping mechanisms of effect. In general, they include

reducing the growth activity of tumor cells, inhibiting tumor cell

angiogenesis, inducing apoptosis, blocking the cell growth cycle,

and reprogramming the metabolic process of tumor cells, affecting

the proliferation, migration and invasion of tumor cells (58). Moreover, several studies have

reported that astragalin does not cause harm to normal human cells

(8,153).

Astragalin has shown promising results in different

types of cancer. For example, radiotherapy may lead to

neurotoxicity (154),

cancer-caused fatigue (155) and

gastrointestinal impairment, and other therapeutic adverse effects

(156,157). However, previous research has

suggested that if astragalin is used in combination with

chemotherapeutic drugs, the neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant (158,159) and antibacterial effects of

astragalin could assist the action of the chemotherapeutic drugs

(160). Moreover, research has

reported that astragalin is involved in targeting cellular

resistance factors (89): It can

enhance the accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs in cells and

increase the sensitivity of cells to the drugs, thus reversing

cellular resistance (39). However,

at present, there is a lack of direct research data on the

application of astragalin and chemotherapeutic agents in other

cancers. Based on the collection of existing literature, we

hypothesize that astragalin can serve a direct inhibitory and

blocking role in the growth and metabolism of tumor cells,

hindering cell growth, proliferation, invasion and migration, and

inducing apoptosis through several mechanisms. At the same time, we

hypothesize that it can serve a unique toxicity-reducing and

synergistic effect in the standardized radiotherapy process. This

gives it the potential to be used as a complementary or alternative

treatment to first-line chemotherapeutic agents.

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and

toxicity model predictions have reported that astragalin is not

susceptible to acute hazards or systemic toxicity and, meeting drug

safety requirements, may reduce accumulation toxicity to normal

tissues through exocytosis mechanisms (153). In A549 lung cancer cells,

astragalin had an IC50 of 150 µM (after 72 h treatment)

and inhibited 85% of lung cancer cells; however, to the best of our

knowledge, at this dose, there is no evidence of toxicity to normal

lung bronchial epithelial cells and cell survival was markedly

higher compared with that of cancer cells (26). Moreover, the IC50 was

20–50 µM in A498 renal carcinoma cells and ≤110 µM in normal renal

cells, indicating that the toxicity to normal cells was notably

lower than that to cancer cells (89). Additionally, the IC50 of

astragalin-containing extract of Citrus × aurantium

was 23.26 µg/ml in colon cancer HCT-116 cells; however, the

toxicity in normal lung fibroblasts (WI-38) was low, with no marked

IC50 value reported. This suggests that astragalin may

have a selective effect on cancer and normal cells (161). Moreover, the aforementioned

findings indicate that astragalin has a wide therapeutic window and

exhibits notable anticancer activity with a high safety profile for

normal cells.

In summary, astragalin has potent antitumor

biological effects with little or no toxic effects on normal

tissues; however, this needs to be supported by further evidence

from numerous future clinical trials.

Previous research reported that the absolute oral

bioavailability of astragalin in rats was <5% (162). This is mainly due to its molecular

structure (higher molecular weight and worse water solubility)

(163) and its easy conversion by

metabolic enzymes [such as uridine

diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs)] in the liver and

intestine, which is characterized by rapid absorption and clearance

(8). However, improved processing

or structural optimization may enhance gastric absorption and delay

metabolism, thereby increasing bioavailability (164,165). UGT enzymes have been reported to

be key metabolizing enzymes of astragalin in vivo. They

include CtUGT3 (166) and

AtUGT78D2 (167). Moreover,

astragalin is distributed in several organs, with the highest

concentration in the gastrointestinal tract. It can also cross the

blood-brain barrier (168) and can

be detected in the liver, lungs and kidneys (169). However, although there are studies

that investigated the pharmacokinetics of astragalin (8,170,171), there is a lack of clinical

pharmacokinetic validation, and the pharmacological properties of

the metabolites, lower bioavailability and stability enhancement

need to be further optimized.

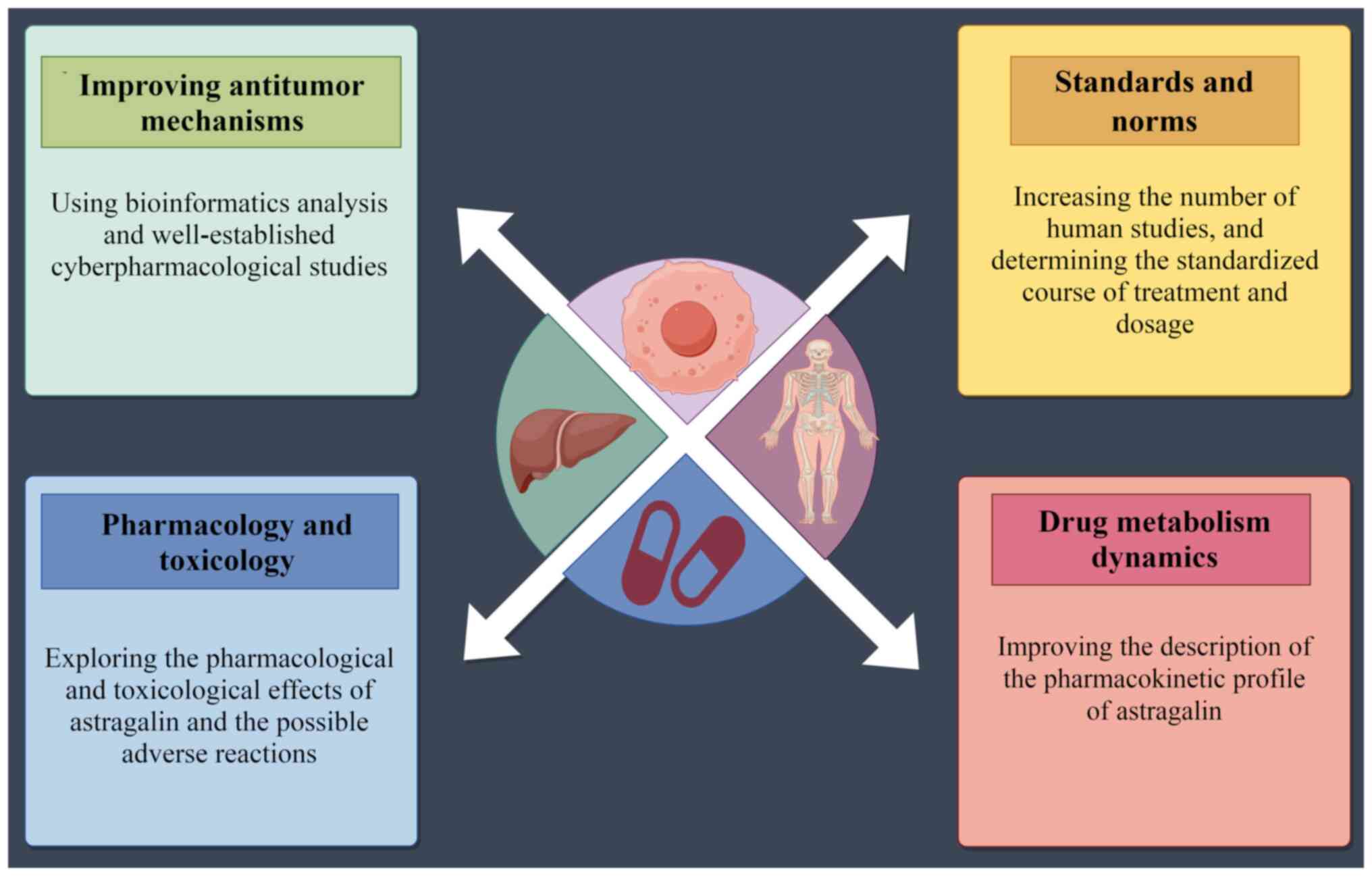

Therefore, future in-depth studies on astragalin

should focus on the advancement of data on the real drug

environment in the clinic, as well as data associated with drug

metabolism pathways and pharmacokinetics in a standardized manner,

with a view to providing an objective basis for the development of

new drugs and the update of therapeutic regimens.

In the research of malignant tumors, the

development and utilization of herbal medicines has become a major

topic. The results of the present review indicate that astragalin,

with its wide and natural sources, strong anticancer activity, high

safety value and low cost, has potential to be an alternative drug

with considerable efficacy in the prevention and treatment of

malignant tumors; however, further research is required. Although

astragalin has demonstrated promising antitumor effects, its

pharmacokinetic profile is incompletely defined, and its low oral

bioavailability limits its potential clinical application. Future

studies should investigate the bioavailability of astragalin

through systematic in vitro and animal experiments, and the

optimization of formulation processes for novel drug delivery

systems. With further research, astragalin has the potential to

become an alternative drug for cancer treatment in the future.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82274566).

Not applicable.

YFZ retrieved the data and participated in the

conceptualization and design of the article as well as the data

analysis; YQF wrote the original manuscript and made several

revisions with the assistance and editing of CL, DND and FYL. FJH

was involved in the design of the manuscript and the interpretation

of the data. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

contributed to the article and read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Nussinov R, Tsai CJ and Jang H: Anticancer

drug resistance: An update and perspective. Drug Resist Updat.

59:1007962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zilla MK, Nayak D, Amin H, Nalli Y, Rah B,

Chakraborty S, Kitchlu S, Goswami A and Ali A:

4′-Demethyl-deoxypodophyllotoxin glucoside isolated from

Podophyllum hexandrum exhibits potential anticancer activities by

altering Chk-2 signaling pathway in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Chem

Biol Interact. 224:100–107. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Martău GA, Bernadette-Emőke T, Odocheanu

R, Soporan DA, Bochiș M, Simon E and Vodnar DC: Vaccinium species

(Ericaceae): Phytochemistry and biological properties of medicinal

plants. Molecules. 28:15332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ruan J, Shi Z, Cao X, Dang Z, Zhang Q,

Zhang W, Wu L, Zhang Y and Wang T: Research progress on

anti-inflammatory effects and related mechanisms of astragalin. Int

J Mol Sci. 25:44762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Barge S, Deka B, Kashyap B, Bharadwaj S,

Kandimalla R, Ghosh A, Dutta PP, Samanta SK, Manna P, Borah JC and

Talukdar NC: Astragalin mediates the pharmacological effects of

Lysimachia candida Lindl on adipogenesis via downregulating PPARG

and FKBP51 signaling cascade. Phytother Res. 35:6990–7003. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mladenova SG, Vasileva LV, Savova MS,

Marchev AS, Tews D, Wabitsch M, Ferrante C, Orlando G and Georgiev

MI: Anti-Adipogenic effect of alchemilla monticola is mediated Via

PI3K/AKT signaling inhibition in human adipocytes. Front Pharmacol.

12:7075072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ceramella J, Loizzo MR, Iacopetta D,

Bonesi M, Sicari V, Pellicanò TM, Saturnino C, Malzert-Fréon A,

Tundis R, Sinicropi MS, et al: Anchusa azurea Mill. (Boraginaceae)

aerial parts methanol extract interfering with cytoskeleton

organization induces programmed cancer cells death. Food Funct.

10:4280–4290. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen J, Zhong K, Qin S, Jing Y, Liu S, Li

D and Peng C: Astragalin: A food-origin flavonoid with therapeutic

effect for multiple diseases. Front Pharmacol. 14:12659602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tao Y, Bao J, Zhu F, Pan M, Liu Q and Wang

P: Ethnopharmacology of Rubus idaeus Linnaeus: A critical review on

ethnobotany, processing methods, phytochemicals, pharmacology and

quality control. J Ethnopharmacol. 302:1158702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhao ZW, Zhang M, Wang G, Zou J, Gao JH,

Zhou L, Wan XJ, Zhang DW, Yu XH and Tang CK: Astragalin retards

atherosclerosis by promoting cholesterol efflux and inhibiting the

inflammatory response via upregulating ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression

in macrophages. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 77:217–227. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rajani V, Umadevi S and Raju CN: A review

on exploring the phytochemical and pharmacological significance of

Indigofera astragalina. Pharmacogn Mag. 20:363–371. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang N, Singh D and Wu Q: Astragalin

attenuates diabetic cataracts via inhibiting aldose reductase

activity in rats. Int J Ophthalmol. 16:1186–1195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bangar SP, Singh A, Chaudhary V, Sharma N

and Lorenzo JM: Beetroot as a novel ingredient for its versatile

food applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 63:8403–8427. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mohammed AE, Alghamdi SS, Shami A, Suliman

RS, Aabed K, Alotaibi MO and Rahman I: In silico prediction of

malvaviscus arboreus metabolites and green synthesis of silver

nanoparticles-opportunities for safer anti-bacterial and

anti-cancer precision medicine. Int J Nanomedicine. 18:2141–2162.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen SC, Xiang XY, Han WC, Chen MY and Xie

BC: Research progress on pharmacological properties and mechanism

of astragalin. Chin J Tradit Chin Med. 40:118–123+287. 2022.(In

Chinese).

|

|

16

|

Yang M, Li WY, Xie J, Wang ZL, Wen YL,

Zhao CC, Tao L, Li LF, Tian Y and Sheng J: Astragalin inhibits the

proliferation and migration of human colon cancer HCT116 cells by

regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol.

12:6392562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Z, Lv J, Li X and Lin Q: The

flavonoid Astragalin shows anti-tumor activity and inhibits

PI3K/AKT signaling in gastric cancer. Chem Biol Drug Des.

98:779–786. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tian S, Wei Y, Hu H and Zhao H: Mixed

computational-experimental study to reveal the anti-metastasis and

anti-angiogenesis effects of Astragalin in human breast cancer.

Comput Biol Med. 150:1061312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sharma R: Mapping of global, regional and

national incidence, mortality and mortality-to-incidence ratio of

lung cancer in 2020 and 2050. Int J Clin Oncol. 27:665–675. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rossi R, De Angelis ML, Xhelili E, Sette

G, Eramo A, De Maria R, Incani UC, Francescangeli F and Zeuner A:

Lung cancer organoids: The rough path to personalized medicine.

Cancers (Basel). 14:37032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Prete M, Ballarin G, Porciello G, Arianna

A, Luongo A, Belli V, Scalfi L and Celentano E: Bioelectrical

impedance analysis-derived phase angle (PhA) in lung cancer

patients: A systematic review. BMC Cancer. 24:6082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu S, Wei W, Wang J and Chen T:

Theranostic applications of selenium nanomedicines against lung

cancer. J Nanobiotechnology. 21:962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xi Chen and Jin Qi: Flavonoids and

Alkaloids in Lotus Leaves. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae. 211–214.

2015.

|

|

24

|

Wang D, Yu J, Cheng L, Hu X, Xiang M, Zhou

Y, Tao B, Liu C and Xia Y: Research Progress on Main Constituents

and Biological Activities of Lotus Leaves. Agricultural Technology

& Equipment. 71–72. 742021.(In Chinese).

|

|

25

|

Jia XB, Zhang Q, Xu L, Yao WJ and Wei L:

Lotus leaf flavonoids induce apoptosis of human lung cancer A549

cells through the ROS/p38 MAPK pathway. Biol Res. 54:72021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Xu G, Yu B, Wang R, Jiang J, Wen F and Shi

X: Astragalin flavonoid inhibits proliferation in human lung

carcinoma cells mediated via induction of caspase-dependent

intrinsic pathway, ROS production, cell migration and invasion

inhibition and targeting JAK/STAT signalling pathway. Cell Mol Biol

(Noisy-le-grand). 67:44–49. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Xiao D, Bai JC and Zhang B: Research

progress of signal pathways related to the anti-tumor effect of

Astragalin. J Pract Oncol. 38:62–66. 2024.

|

|

28

|

Liang Y and Chen W: Effect of Astragalin

on proliferation, migration, apoptosis and oxidative stress of lung

cancer A549 cells. Chin J Clin Pharmacol. 39:999–1003. 2023.(In

Chinese).

|

|

29

|

Chen M, Cai F, Zha D, Wang X, Zhang W, He

Y, Huang Q, Zhuang H and Hua ZC: Astragalin-induced cell death is

caspase-dependent and enhances the susceptibility of lung cancer

cells to tumor necrosis factor by inhibiting the NF-кB pathway.

Oncotarget. 8:26941–26958. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yan C, Pang X, Fan W, Dai W, Hu X, Mei Q

and Zeng C: Mechanism of leaves of Microcos paniculata

improving of dyspepsia based on network pharmacology and molecular

docking. Drugs & Clinic. 38:1335–1343. 2023.(In Chinese).

|

|

31

|

Li M, Zhao Z, Xuan J, Li Z and Ma T:

Advances in Studies on Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological

Effects of Lotus Leaves. Journal of Liaoning University of TCM.

22:135–138. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Bai J, Chen Y, Zhao G and Gui R: In vitro

and vivo experiments revealing astragalin inhibited lung

adenocarcinoma development via LINC00582/miR-140-3P/PDPK1. J

Biochem Mol Toxicol. 38:e700422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ribeiro V, Ferreres F, Macedo T,

Gil-Izquierdo Á, Oliveira AP, Gomes NGM, Araújo L, Pereira DM,

Andrade PB and Valentão P: Activation of caspase-3 in gastric

adenocarcinoma AGS cells by Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich.

fruit and characterization of its phenolic fingerprint by

HPLC-DAD-ESI(Ion Trap)-MSn and UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS2. Food Res Int.

141:1101212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Webb PM and Jordan SJ: Global epidemiology

of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 21:389–400. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yang C, Xia BR, Zhang ZC, Zhang YJ, Lou G

and Jin WL: Immunotherapy for ovarian cancer: Adjuvant,

combination, and neoadjuvant. Front Immunol. 11:5778692020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gu L, Du N, Jin Q, Li S, Xie L, Mo J, Shen

Z, Mao D, Ji J, et al: Magnitude of benefit of the addition of poly

ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors to therapy for malignant

tumor: A meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 147:1028882020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Song L and Fu Q: Study of the effect of

astragalin on proliferation of ovarian cancer cells by inhibiting

the glycolytic pathway induced Via HIF-1α. Pract Oncol J.

32:503–509. 2018.

|

|

39

|

Ling Song and Qiong Fu: Astragalin

inhibits hypoxia-induced proliferation and invasion of ovarian

cancer cells by up-regulating PHD2. J Pract Oncol. 33:407–414.

2019.

|

|

40

|

Mazzone M, Dettori D, de Oliveira RL,

Loges S, Schmidt T, Jonckx B, Tian YM, Lanahan AA, Pollard P, de

Almodovar CR, et al: Heterozygous deficiency of PHD2 restores tumor

oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization.

Cell. 136:839–851. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Guentsch A, Beneke A, Swain L, Farhat K,

Nagarajan S, Wielockx B, Raithatha K, Dudek J, Rehling P and

Zieseniss A: PHD2 is a regulator for glycolytic reprogramming in

macrophages. Mol Cell Biol. 37:e00236–e00216. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Mehla K and Singh PK: MUC1: A novel

metabolic master regulator. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1845:126–135.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Katayama Y, Uchino J, Chihara Y, Tamiya N,

Kaneko Y, Yamada T and Takayama K: Tumor neovascularization and

developments in therapeutics. Cancers (Basel). 11:3162019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li RL, He LY, Zhang Q, Liu J, Lu F, Duan

HX, Fan LH, Peng W, Huang YL and Wu CJ: HIF-1α is a potential

molecular target for herbal medicine to treat diseases. Drug Des

Devel Ther. 14:4915–4949. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang CZ, Wang SH, Zhang RH, Lin JH, Tian

YH, Yang YQ, Liu J and Ma YX: Neuroprotective effect of astragalin

via activating PI3K/Akt-mTOR-mediated autophagy on APP/PS1 mice.

Cell Death Discov. 9:152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ediriweera MK, Tennekoon KH and Samarakoon

SR: Role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in ovarian cancer:

Biological and therapeutic significance. Semin Cancer Biol.

59:147–160. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Shu-ping Qu, Chun-jun Liu and Ju-hua

Liang: Correlation between serum miR-410,miR-875 expression with

HPV infection in cervical cancer patients. J Path Biol.

19:1404–1407. 2024.

|

|

48

|

Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Arend R, Barber

E, Bradley K, Brooks R, Campos SM, Chino J, Chon HS, Crispens MA,

et al: NCCN Guidelines® insights: Cervical cancer,

version 1.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:1224–1233. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Raj S, Prasad RR and Ranjan A: Incidence

of vaginal toxicities following definitive chemoradiation in intact

cervical cancer: A meta-analysis. J Contemp Brachytherapy.

16:241–256. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zeng W and Chen L: Astragalin inhibits the

proliferation of high-risk HPV-positive cervical epithelial cells

and attenuates malignant cervical lesions. Cytotechnology.

77:802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

He M, Yasin K, Yu S, Li J and Xia L: Total

flavonoids in Artemisia absinthium L. and evaluation of its

anticancer activity. Int J Mol Sci. 24:163482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zerrouki S, Mezhoud S, Yilmaz MA,

Yaglioglu AS, Bakir D, Demirtas I and Mekkiou R: LC/MS-MS analyses

and in vitro anticancer activity of Tourneuxia variifolia

extracts. Nat Prod Res. 36:4506–4510. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xu X, Zhou N, Lan H, Yang F, Dong B and

Zhang X: The ferroptosis molecular subtype reveals characteristics

of the tumor microenvironment, immunotherapeutic response, and

prognosis in gastric cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 23:97672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Mamun TI, Younus S and Rahman MH: Gastric

cancer-Epidemiology, modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors,

challenges and opportunities: An updated review. Cancer Treat Res

Commun. 41:1008452024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang J, Du L and Chen X: Adenosine

signaling: Optimal target for gastric cancer immunotherapy. Front

Immunol. 13:10278382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu Y, Huang T, Wang L, Wang Y, Liu Y, Bai

J, Wen X, Li Y, Long K and Zhang H: Traditional Chinese medicine in

the treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis, precancerous lesions

and gastric cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 337:1188122025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Radziejewska I, Supruniuk K, Tomczyk M,

Izdebska W, Borzym-Kluczyk M, Bielawska A, Bielawski K and Galicka

A: p-Coumaric acid, Kaempferol, Astragalin and Tiliroside influence

the expression of glycoforms in AGS gastric cancer cells. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:86022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Chu ZH, He SY, Wang Y, Zhu RT, Gu YL and

Chen JY: Effects of Astragalin on apoptosis of undifferentiated

gastric cancer cells. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi.

38:520–524. 2022.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sharafutdinov I, Tegtmeyer N, Linz B,

Rohde M, Vieth M, Tay AC, Lamichhane B, Tuan VP, Fauzia KA, Sticht

H, et al: A single-nucleotide polymorphism in Helicobacter pylori

promotes gastric cancer development. Cell Host Microbe.

31:1345–1358.e6. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Tan A, Scortecci KC, De Medeiros NM,

Kukula-Koch W, Butler TJ, Smith SM and Boylan F: Plukenetia

volubilis leaves as source of anti-Helicobacter pylori agents.

Front Pharmacol. 15:14614472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Murphy CC and Zaki TA: Changing

epidemiology of colorectal cancer-birth cohort effects and emerging

risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21:25–34. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ebnudesita FR, Dienanta SB, Jannah AR and

I'tishom R: Potency of soursop leaf extract and curcumin with

magnetic and mucus-penetrating nanoparticle as colorectal cancer

alternative therapY. J Vocational Health Studies. 5:186–191. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Abedizadeh R, Majidi F, Khorasani HR,

Abedi H and Sabour D: Colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review of

carcinogenesis, diagnosis, and novel strategies for classified

treatments. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43:729–753. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Chen L, Chen C, Wang P and Song T:

Mechanisms of cellular effects directly induced by magnetic

nanoparticles under magnetic fields. J Nanomaterials. 2017:1–13.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Eng C, Yoshino T, Ruíz-García E, Mostafa

N, Cann CG, O'Brian B, Benny A, Perez RO and Cremolini C:

Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 404:294–310. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zou Y, Wang S, Zhang H, Gu Y, Chen H,

Huang Z, Yang F, Li W, Chen C, Men L, et al: The triangular

relationship between traditional Chinese medicines, intestinal

flora, and colorectal cancer. Med Res Rev. 44:539–567. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Augustynowicz D, Lemieszek MK, Strawa JW,

Wiater A and Tomczyk M: Anticancer potential of acetone extracts

from selected Potentilla species against human colorectal cancer

cells. Front Pharmacol. 13:10273152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhai Y, Sun J, Sun C, Zhao H, Li X, Yao J,

Su J, Xu X, Xu X, Hu J, et al: Total flavonoids from the dried root

of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg inhibit colorectal cancer

growth through PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Phytother Res.

36:4263–4277. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Tragulpakseerojn J, Yamaguchi N,

Pamonsinlapatham P, Wetwitayaklung P, Yoneyama T, Ishikawa N,

Ishibashi M and Apirakaramwong A: Anti-proliferative effect of

Moringa oleifera Lam (Moringaceae) leaf extract on human colon

cancer HCT116 cell line. Trop J Pharm Res. 16:371–378. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Chidambaram A, Prabhakaran R, Sivasamy S,

Kanagasabai T, Thekkumalai M, Singh A, Tyagi MS and Dhandayuthapani

S: Male breast cancer: Current scenario and future perspectives.

Technol Cancer Res Treat. 23:153303382412618362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Palmer BV, Walsh GA, McKinna JA and

Greening WP: Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Side effects

and quality of life. BMJ. 281:1594–1597. 1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Di Nardo P, Lisanti C, Garutti M, Buriolla

S, Alberti M, Mazzeo R and Puglisi F: Chemotherapy in patients with

early breast cancer: Clinical overview and management of long-term

side effects. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 21:1341–1355. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Kim SD, Kwag EB, Yang MX and Yoo HS:

Efficacy and safety of ginger on the side effects of chemotherapy

in breast cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int

J Mol Sci. 23:112672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Peeters NJMC, Kaplan ZLR, Clarijs ME,

Mureau MAM, Verhoef C, van Dalen T, Husson O and Koppert LB:

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after different axillary

treatments in women with breast cancer: A 1-year longitudinal

cohort study. Qual Life Res. 33:467–479. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Meng X, Zhang A, Wang X and Sun H: A

kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucoside, intervention effect of astragalin on

estradiol metabolism. Steroids. 149:1084132019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zeb A, Khan W, Ul Islam W, Khan F, Khan A,

Khan H, Khalid A, Rehman NU, Ullah A and Al-Harrasi A: Exploring

the anticancer potential of astragalin in triple negative breast

cancer cells by attenuating glycolytic pathway through AMPK/mTOR.

Curr Med Chem. Jul 25–2024.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Nunnery SE and Mayer IA: Targeting the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hormone-positive breast cancer. Drugs.

80:1685–1697. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Song X, Shen L, Contreras JM, Liu Z, Ma K,

Ma B, Liu X and Wang DO: New potential selective estrogen receptor

modulators in traditional Chinese medicine for treating menopausal

syndrome. Phytother Res. 38:4736–4756. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Huq AM, Stanslas J, Nizhum N, Uddin MN,

Maulidiani M, Roney M, Abas F and Jamal JA: Estrogenic

post-menopausal anti-osteoporotic mechanism of Achyranthes aspera

L.: Phytochemicals and network pharmacology approaches. Heliyon.

10:e387922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Bellai A, Deka S, Tag H, Bhattacharya K

and Hui PK: Integrated pharmacognostic and computational analysis

of Hydrocotyle javanica thunb. Phytochemicals as a potential

HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor in breast cancer. Pept Sci.

119:e243722024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Ahn S, Jung H, Jung Y, Lee J, Shin SY, Lim

Y and Lee Y: Identification of the active components inhibiting the

expression of matrix metallopeptidase-9 by TNFα in ethyl acetate

extract of Euphorbia humifusa Willd. J Appl Biol Chem. 62:367–374.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Shin SY, Kim CG, Jung YJ, Jung Y, Jung H,

Im J, Lim Y and Lee YH: Euphorbia humifusa Willd exerts inhibition

of breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis through inhibition of

TNFα-induced MMP-9 expression. BMC Complement Altern Med.

16:4132016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Cirillo L, Innocenti S and Becherucci F:

Global epidemiology of kidney cancer. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

39:920–928. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Young M, Jackson-Spence F, Beltran L, Day

E, Suarez C, Bex A, Powles T and Szabados B: Renal cell carcinoma.

Lancet. 404:476–491. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Imamura R, Tanaka R, Taniguchi A, Nakazawa

S, Kato T, Yamanaka K, Namba-Hamano T, Kakuta Y, Abe T, Tsutahara

K, et al: Everolimus reduces cancer incidence and improves patient

and graft survival rates after kidney transplantation: A

multi-center study. J Clin Med. 11:2492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Chen H: microRNA-Based cancer diagnosis

and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 25:2302024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Zhang W, Chan C, Zhang K, Qin H, Yu BY,

Xue Z, Zheng X and Tian J: Discovering a new drug against acute

kidney injury by using a tailored photoacoustic imaging probe. Adv

Mater. 36:e23113972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Zhu L, Zhu L, Chen J, Cui T and Liao W:

Astragalin induced selective kidney cancer cell death and these

effects are mediated via mitochondrial mediated cell apoptosis,

cell cycle arrest, and modulation of key tumor-suppressive miRNAs.

J BUON. 24:1245–1251. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Wu N, Li J and Tao J: Hot spots in

diagnosis of malignant melanoma. J Diagn Concepts Pract.

22:215–219. 2023.(In Chinese).

|

|

91

|

Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J,

Vaccarella S, Meheus F, Cust AE, de Vries E, Whiteman DC and Bray

F: Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to

2040. JAMA Dermatol. 158:495–503. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Swetter SM, Johnson D, Albertini MR,

Barker CA, Bateni S, Baumgartner J, Bhatia S, Bichakjian C, Boland

G, Chandra S, et al: NCCN Guidelines® insights:

Melanoma: Cutaneous, version 2.2024: Featured updates to the NCCN

guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 22:290–298. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Ernst M and Giubellino A: The current

state of treatment and future directions in cutaneous malignant

melanoma. Biomedicines. 10:8222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Li J, Liu X, Wang W, Li C and Li X: MSK1

promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in uveal melanoma by

phosphorylating CREB. Arch Med Sci. 16:1176–1188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Li N, Zhang K, Mu X, Tian Q, Liu W, Gao T,

Ma X and Zhang J: Astragalin attenuates UVB radiation-induced

actinic keratosis formation. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.

18:1001–1008. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

You OH, Shin EA, Lee H, Kim JH, Sim DY,

Kim JH, Kim Y, Khil JH, Baek NI and Kim SH: Apoptotic effect of

astragalin in melanoma skin cancers via activation of caspases and

inhibition of sry-related HMg-Box gene 10. Phytother Res.

31:1614–1620. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Wang J, Bian Y, Cheng Y, Sun R and Li G:

Effect of lemon peel flavonoids on UVB-induced skin damage in mice.

RSC Adv. 10:31470–31478. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Løvf M, Zhao S, Axcrona U, Johannessen B,

Bakken AC, Carm KT, Hoff AM, Myklebost O, Meza-Zepeda LA, Lie AK,

et al: multifocal primary prostate cancer exhibits high degree of

genomic heterogeneity. Eur Urol. 75:498–505. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Lafontaine ML and Kokorovic A:

Cardiometabolic side effects of androgen deprivation therapy in

prostate cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 16:216–222. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Moses KA, Sprenkle PC, Bahler C, Box G,

Carlsson SV, Catalona WJ, Dahl DM, Dall'Era M, Davis JW, Drake BF,

et al: NCCN Guidelines® insights: Prostate cancer early

detection, version 1.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:236–246.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Beer TM, Hotte SJ, Saad F, Alekseev B,

Matveev V, Fléchon A, Gravis G, Joly F, Chi KN, Malik Z, et al:

Custirsen (OGX-011) combined with cabazitaxel and prednisone versus

cabazitaxel and prednisone alone in patients with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer previously treated with

docetaxel (AFFINITY): A randomised, open-label, international,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18:1532–1542. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Shahab MRF and Shahab N: Recent advances

and future directions in the management of metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer asing androgen receptor

signaling inhibitors and poly-adipose polymerase inhibitors: A

literature review. International J Multidisciplinary Research.

6:22024.

|

|

103

|

Koyuncu I, Temiz E, Seker F, Balos MM,

Akkafa F, Yuksekdag O, Yılmaz MA and Zengin G: A mixed-apoptotic

effect of Jurinea mesopotamica extract on prostate cancer cells: A

promising source for natural chemotherapeutics. Chem Biodivers.

21:e2023017472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Kim H, Hwang B, Cho S, Kim WJ, Myung SC,

Choi YH, Kim WJ, Lee S and Moon SK: The ethanol extract of Cyperus

exaltatus var. iwasakii exhibits cell cycle dysregulation,

ERK1/2/p38 MAPK/AKT phosphorylation, and reduced MMP-9-mediated

metastatic capacity in prostate cancer models in vitro and in vivo.

Phytomedicine. 114:1547942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Li X, Ramadori P, Pfister D, Seehawer M,

Zender L and Heikenwalder M: The immunological and metabolic

landscape in primary and metastatic liver cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

21:541–557. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Chiang CL, Chiu KWH, Chan KSK, Lee FAS, Li

JCB, Wan CWS, Dai WC, Lam TC, Chen W, Wong NSM, et al: Sequential

transarterial chemoembolisation and stereotactic body radiotherapy

followed by immunotherapy as conversion therapy for patients with

locally advanced, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

(START-FIT): A single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 8:169–178. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Pennington B, Akehurst R, Wasan H, Sangro

B, Kennedy AS, Sennfält K and Bester L: Cost-effectiveness of

selective internal radiation therapy using yttrium-90 resin

microspheres in treating patients with inoperable colorectal liver

metastases in the UK. J Med Econ. 18:797–804. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Chen C, Chen F, Gu L, Jiang Y, Cai Z, Zhao

Y, Chen L, Zhu Z and Liu X: Discovery and validation of COX2 as a

target of flavonoids in Apocyni Veneti Folium: Implications for the

treatment of liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 326:1179192024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Li W, Hao J, Zhang L, Cheng Z, Deng X and

Shu G: Astragalin reduces hexokinase 2 through increasing miR-125b

to inhibit the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in

vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 65:5961–5972. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Hong Z, Lu Y, Ran C, Tang P, Huang J, Yang

Y, Duan X and Wu H: The bioactive ingredients in Actinidia

chinensis Planch. Inhibit liver cancer by inducing apoptosis. J

Ethnopharmacol. 281:1145532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Pirvu L, Stefaniu A, Neagu G, Albu B and

Pintilie L: In vitro cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Activity of

Cydonia oblonga flower petals, leaf and fruit pellet ethanolic

extracts. Docking simulation of the active flavonoids on

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. Open Chemistry. 16:591–604. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Kaidash OA, Kostikova VA, Udut EV, Shaykin

VV and Kashapov DR: Extracts of Spiraea hypericifolia L. and

Spiraea crenata L.: The phenolic profile and biological activities.

Plants. 11:27282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Zhou K, Xiao S, Cao S, Zhao C, Zhang M and

Fu Y: Improvement of glucolipid metabolism and oxidative stress via

modulating PI3K/Akt pathway in insulin resistance HepG2 cells by

chickpea flavonoids. Food Chem X. 23:1016302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Murray CJL: The global burden of disease

study at 30 years. Nat Med. 28:2019–2026. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Nadiminti KVG, Sahasrabudhe KD and Liu H:

Menin inhibitors for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia:

Challenges and opportunities ahead. J Hematol Oncol. 17:1132024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Lam CS, Peng LW, Yang LS, Chou HWJ, Li CK,

Zuo Z, Koon HK and Cheung YT: Examining patterns of traditional

Chinese medicine use in pediatric oncology: A systematic review,

meta-analysis and data-mining study. J Integr Med. 20:402–415.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Burmistrova O, Quintana J, Díaz JG and

Estévez F: Astragalin heptaacetate-induced cell death in human

leukemia cells is dependent on caspases and activates the MAPK

pathway. Cancer Lett. 309:71–77. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Lee KH, Tagahara K, Suzuki H, Wu RY,

Haruna M, Hall IH, Huang HC, Ito K, Iida T and Lai JS: Antitumor

agents. 49 tricin, kaempferol-3-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside and

(+)-nortrachelogenin, antileukemic principles from Wikstroemia

indica. J Nat Prod. 44:530–535. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Delloye-Bourgeois C and Castellani V:

Hijacking of embryonic programs by neural crest-derived

neuroblastoma: From physiological migration to metastatic

dissemination. Front Mol Neurosci. 12:522019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T,

Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J, Dimitrova N, Jakab Z, Kaatsch P, Lacour

B, et al: Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: Results of

EUROCARE-5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 15:35–47. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Kholodenko IV, Kalinovsky DV, Doronin II,

Deyev SM and Kholodenko RV: Neuroblastoma origin and therapeutic

targets for immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2018:73942682018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Berlanga P, Cañete A and Castel V:

Advances in emerging drugs for the treatment of neuroblastoma.

Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 22:63–75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Shekarian T and Valsesia-Wittmann S:

Considerations for the development of innovative therapies against

aggressive neuroblastoma: Immunotherapy and Twist1 targeting.

Neuroblastoma-Current State and Recent Updates. Gowda C: InTech;

2017, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Luksch R, Castellani MR, Collini P, De

Bernardi B, Conte M, Gambini C, Gandola L, Garaventa A, Biasoni D,

Podda M, et al: Neuroblastoma (Peripheral neuroblastic tumours).

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 107:163–181. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Lodrini M, Sprüssel A, Astrahantseff K,

Tiburtius D, Konschak R, Lode HN, Fischer M, Keilholz U, Eggert A

and Deubzer HE: Using droplet digital PCR to analyze MYCN and ALK

copy number in plasma from patients with neuroblastoma. Oncotarget.

8:85234–85251. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Johnsen JI, Dyberg C, Fransson S and

Wickström M: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets in

neuroblastoma. Pharmacol Res. 131:164–176. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Zafar A, Wang W, Liu G, Wang X, Xian W,

McKeon F, Foster J, Zhou J and Zhang R: Molecular targeting

therapies for neuroblastoma: Progress and challenges. Med Res Rev.

41:961–1021. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Chung MJ, Lee S, Park YI, Lee J and Kwon

KH: Neuroprotective effects of phytosterols and flavonoids from

Cirsium setidens and Aster scaber in human brain neuroblastoma

SK-N-SH cells. Life Sci. 148:173–182. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Chamoli A, Gosavi AS, Shirwadkar UP,

Wangdale KV, Behera SK, Kurrey NK, Kalia K and Mandoli A: Overview

of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Risk factors, mechanisms,

and diagnostics. Oral Oncol. 121:1054512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Tan Y, Wang Z, Xu M, Li B, Huang Z, Qin S,

Nice EC, Tang J and Huang C: Oral squamous cell carcinomas: State

of the field and emerging directions. Int J Oral Sci. 15:442023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Katirachi SK, Grønlund MP, Jakobsen KK,

Grønhøj C and von Buchwald C: The prevalence of HPV in oral cavity

squamous cell carcinoma. Viruses. 15:4512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Li H, Zhang Y, Xu M and Yang D: Current

trends of targeted therapy for oral squamous cell carcinoma. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 148:2169–2186. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Arboleda LPA, de Carvalho GB, Santos-Silva

AR, Fernandes GA, Vartanian JG, Conway DI, Virani S, Brennan P,

Kowalski LP and Curado MP: Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral

cavity, oropharynx, and larynx: A scoping review of treatment

guidelines worldwide. Cancers (Basel). 15:44052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Ma YX, Li XJ, Jin Q, Ji L and Qiao Q:

Application of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in locally advanced

squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat.

31:968–974. 2024.

|

|

135

|

Wang X, Li J, Chen R, Li T and Chen M:

Active ingredients from Chinese medicine for combination cancer

therapy. Int J Biol Sci. 19:3499–3525. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Zhang X, Qiu H, Li C, Cai P and Qi F: The

positive role of traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunctive

therapy for cancer. Biosci Trends. 15:283–298. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Miao K, Liu W, Xu J, Qian Z and Zhang Q:

Harnessing the power of traditional Chinese medicine monomers and

compound prescriptions to boost cancer immunotherapy. Front

Immunol. 14:12772432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Zhao S, Xiao S, Wang W, Dong X, Liu X,

Wang Q, Jiang Y and Wu W: Network pharmacology and transcriptomics

reveal the mechanisms of FFBZL in the treatment of oral squamous

cell carcinoma. Front Pharmacol. 15:14055962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Sun Y, Cai J, Ding S and Bao S: Network

Pharmacology Was Used to Predict the Active Components and

Prospective Targets of Paeoniae Radix Alba for Treatment in

Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 30:1103–1117. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Liu WL, Ji MW, Wang YY, Song LN, Jiang Y

and Shao YK: A case report of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with

brachial plexus nerve injury as the first symptom. J Apoplexy Nerv

Dis. 37:842–844. 2020.

|

|

141

|

Qi RL, Qiu MH, Zhang T, Zhao XZ, He GP,

Mei HW and Wang HQ: Progress in treatment of recurrent/refractory

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 27:758–763.

2022.

|

|

142

|

Wang Y, Zhu ML, He SY, Chen H and Chen JY:

Astragalin induces apoptosis of DLBCL cell line OCI-LY8. Chin J

Pathophysiol. 37:885–890. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

143

|

Lu Y, Wu N, Fang Y, Shaheen N and Wei Y:

An automatic on-line 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl-high performance

liquid chromatography method for high-throughput screening of

antioxidants from natural products. J Chromatogr A. 1521:100–109.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Hadzi-Petrushev N, Stojchevski R,

Jakimovska A, Stamenkovska M, Josifovska S, Stamatoski A, Sazdova

I, Sopi R, Kamkin A, Gagov H, et al: GLUT5-overexpression-related

tumorigenic implications. Mol Med. 30:1142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Thompson AM, Iancu CV, Nguyen TTH, Kim D

and Choe J: Inhibition of human GLUT1 and GLUT5 by plant

carbohydrate products; insights into transport specificity. Sci

Rep. 5:128042015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Ingram DK and Roth GS: Glycolytic

inhibition: An effective strategy for developing calorie

restriction mimetics. Geroscience. 43:1159–1169. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Harikrishnan H, Jantan I, Alagan A and

Haque MA: Modulation of cell signaling pathways by Phyllanthus

amarus and its major constituents: Potential role in the prevention

and treatment of inflammation and cancer. Inflammopharmacology.

28:1–18. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Devanaboyina M, Kaur J, Whiteley E, Lin L,

Einloth K, Morand S, Stanbery L, Hamouda D and Nemunaitis J: NF-κB

signaling in tumor pathways focusing on breast and ovarian cancer.

Oncol Rev. 16:105682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Adebayo IA, Balogun WG and Arsad H:

Moringa oleifera: An apoptosis inducer in cancer cells. Trop J

Pharm Res. 16:2289–2296. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

150

|

Yang F, Li AM, Zhang YW, Ma CM and Zhang

HR: Study on the effect of astragalin on apoptosis of human colon

cancer SW480 cells. Guo Ji Yi Yao Wei Sheng Dao Bao She.

26:3013–3017. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

151

|

Karna KK, Choi BR, You JH, Shin YS, Cui

WS, Lee SW, Kim JH, Kim CY, Kim HK and Park JK: The ameliorative

effect of monotropein, astragalin, and spiraeoside on oxidative

stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and mitochondrial signaling

pathway in varicocelized rats. BMC Complement Altern Med.

19:3332019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Yun W, Dan W, Liu J, Guo X, Li M and He Q:

Investigation of the mechanism of traditional Chinese medicines in

angiogenesis through network pharmacology and data mining. Evid

Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021:55399702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Riaz A, Rasul A, Hussain G, Zahoor MK,

Jabeen F, Subhani Z, Younis T, Ali M, Sarfraz I and Selamoglu Z:

Astragalin: A bioactive phytochemical with potential therapeutic

activities. Adv Phar Sc. 2018:1–15. 2018.

|

|

154

|

Lee JH, Saxena A and Giaccone G:

Advancements in small cell lung cancer. Semin Cancer Biol.

93:123–128. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Zhou SB and Chen GZ: Research overview and

reflection on the treatment of cancer-related fatigue in lung

cancer by traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Chin Med Pharm.

52:1–4. 2024.(In Chinese).

|

|

156

|

Adelstein DJ, Moon J, Hanna E, Giri PGS,

Mills GM, Wolf GT and Urba SG: Docetaxel, cisplatin, and

fluorouracil induction chemotherapy followed by accelerated

fractionation/concomitant boost radiation and concurrent cisplatin

in patients with advanced squamous cell head and neck cancer: A

Southwest oncology group phase II trial (S0216). Head Neck.

32:221–228. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

157

|

Andreyev HJN, Davidson SE, Gillespie C,

Allum WH and Swarbrick E; British Society of Gastroenterology;

Association of Colo-Proctology of Great Britain Ireland;

Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons; Faculty of Clinical

Oncology Section of the Royal College of Radiologists, : Practice

guidance on the management of acute and chronic gastrointestinal

problems arising as a result of treatment for cancer. Gut.

61:179–192. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

158

|

Bower JE: The role of neuro-immune

interactions in cancer-related fatigue: Biobehavioral risk factors

and mechanisms. Cancer. 125:353–364. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

159

|

de Raaf PJ, Sleijfer S, Lamers CHJ, Jager

A, Gratama JW and van der Rijt CCD: Inflammation and fatigue

dimensions in advanced cancer patients and cancer survivors: an

explorative study. Cancer. 118:6005–6011. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Wen YL, Li WY, Zhang N, Su RZ, Xia JR, Li

LF and Tian Y: The inhibitory effect of astragalin on escherichia

coli and its mechanism. J Yunnan Agricultural University.

37:471–477. 2022.

|

|

161

|

Oraibi AI, Dawood AH, Trabelsi G, Mahamat

OB, Chekir-Ghedira L and Kilani-Jaziri S: Antioxidant activity and

selective cytotoxicity in HCT-116 and WI-38 cell lines of LC-MS/MS

profiled extract from Capparis spinosa L. Front Chem.

13:15401742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

162

|

Yang X, Ma B, Zhang Q, Wu X, Gu G, Li J,

Sun J, Tang B, Zhu J, Qia H and Ying H: Comparative

pharmacokinetics with single substances and Semen Cuscutae extract

after oral administration and intravenous administration Semen

Cuscutae extract and single hyperoside and astragalin to rats. Anal

Methods. 6:72502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

163

|

Adamu UM, Renggasamy R, Stanslas J, Razis

AF, Fauzi F, Mulyani SW and Ramasamy R: In-silico prediction

analysis of polyphenolic contents of ethanolic extract of moringa

oleifera leaves. Malays J Med Health Sci. 19:9–15. 2023.

|

|

164

|

Liu J, Zou S, Liu W, Li J, Wang H, Hao J,

He J, Gao X, Liu E and Chang Y: An Established HPLC-MS/MS method

for evaluation of the influence of salt processing on

pharmacokinetics of six compounds in cuscutae semen. Molecules.

24:25022019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

165

|

Choung WJ, Hwang SH, Ko DS, Kim SB, Kim

SH, Jeon SH, Choi HD, Lim SS and Shim JH: Enzymatic synthesis of a

novel Kaempferol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-O-α-d-glucopyranoside

using cyclodextrin glucanotransferase and its inhibitory effects on

aldose reductase, inflammation, and oxidative stress. J Agric Food

Chem. 65:2760–2767. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

166

|

Ren C, Xi Z, Xian B, Chen C, Huang X,

Jiang H, Chen J, Peng C and Pei J: Identification and

characterization of CtUGT3 as the key player of astragalin

biosynthesis in Carthamus Tinctorius L. J Agric Food Chem.

71:16221–16232. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

167

|

Pei J, Dong P, Wu T, Zhao L, Fang X, Cao