Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is a common endocrine malignancy

comprising anaplastic thyroid carcinomas (ATC), medullary thyroid

carcinoma and differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) (1). Globally, there are ~586,202 new cases

of TC and 43,646 deaths associated with it, ranking ninth in

incidence among all cancers. Furthermore, it is expected to

overtake colorectal cancer as the fourth most prevalent cancer in

the USA by 2030 (2,3). Among the subtypes of TC, DTC accounts

for ~95% of cases and generally has a favorable prognosis, whereas

ATC is rare but aggressive, with a median survival of <6 months

(4).

Radioactive iodine ablation continues to be the

primary treatment for TC (5);

however, it is ineffective in all ATC cases and in ~10% of DTC

cases (5). This is due to

resistance caused by changes in the MAPK and PI3K pathways, as well

as mutations or rearrangements in B-Raf proto-oncogene,

serine/threonine kinase, neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase,

telomerase reverse transcriptase, RAS proto-oncogene, GTPase,

anaplastic lymphoma kinase and ret proto-oncogene in ATC and DTC,

which serve as important diagnostic and prognostic markers for TC

(4,6). Targeted inhibitors against these

biomarkers, such as sorafenib, lenvatinib and vemurafenib, have

thus become promising strategies for treating ATC and DTC; however,

targeted therapies face challenges, including limited

effectiveness, drug resistance and serious side effects (4,6).

Therefore, further research into TC molecular mechanisms is

necessary to develop more effective targeted treatment

strategies.

Inducing tumor cell death is a fundamental aspect of

developing cancer treatments. For decades, apoptosis, pyroptosis

and necroptosis were regarded as separate cell death pathways. More

recently, PANoptosis has been described as an integrated

inflammatory cell death process involving crosstalk among

pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis, coordinated by multiprotein

complexes called PANoptosomes (7–11).

PANoptosis begins when pathogen- and damage-associated molecular

patterns activate the pattern recognition receptors Z-DNA-binding

protein 1 (ZBP1) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2). Once activated,

ZBP1 and AIM2 recruit adaptor proteins with protein-interaction

domains to form PANoptosomes, which contain key effectors of

apoptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis, including caspase

(CASP)1/3/8/9, dasdermin D, receptor interacting serine/threonine

kinase 3 (RIPK3) and mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase

(MLKL). Within these structures, the coordinated action of these

effectors causes rupture of the plasma membrane and organelle

membranes, initiating cascades of inflammatory and immune

responses. Notably, PANoptosis has been associated with several

malignancies, including esophageal cancer (12), melanoma (13), adrenocortical carcinoma (14) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(15). Specifically, sulconazole

has been reported to increase the radiosensitivity of esophageal

cancer by inducing PANoptosis (12). Adenosine deaminase RNA specific 1

and CDK1 also facilitate tumor burden in colorectal cancer,

melanoma and adrenocortical carcinoma by suppressing ZBP1-mediated

PANoptosis (13,14). Furthermore, suppression of SAM and

HD domain containing deoxynucleoside triphosphate

triphosphohydrolase 1 has been reported to stimulate PANoptosis by

activating stimulator of interferon response CGAMP interactor,

which effectively alleviates diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(15). Its role in influencing the

tumor immune microenvironment emphasizes its potential for therapy.

Nonetheless, the regulatory mechanisms and critical molecular

factors governing PANoptosis in TC are still unknown, marking a

substantial gap in current knowledge.

The transferrin receptor (TFRC) is a transmembrane

glycoprotein dimer widely expressed on the cell membrane and mainly

involved in cellular iron uptake (16). Due to its role in iron homeostasis,

TFRC has been reported to promote ferroptosis in several cancers,

including TC (17–19), endometrial carcinoma (20), colorectal carcinoma (21), hepatocellular carcinoma (22) and gastric carcinoma (23). For example, high TFRC expression has

been reported to predict a worse prognosis in patients with TC,

compared with low TFRC expression (17,18),

and it interacts with longevity assurance homolog 2 to promote

ferroptosis in TC (19). In

addition to ferroptosis, TFRC has been associated with numerous

cell death types such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, cuproptosis,

autophagy and necrosis (24–26).

Specifically, TFRC promotes PTEN induced kinase 1 (PINK1)-parkin

RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase-dependent mitochondrial autophagy

and apoptosis in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (24). Notably, TFRC-mediated cell death

displays features similar to PANoptosis. Overall, the

aforementioned studies imply that TFRC could serve as a molecular

regulator of PANoptosis.

The present study aimed to identify biomarkers

associated with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression in the TCGA-THCA cohort

and determine their prognostic value in TC. Furthermore, the

present study intended to investigate the utility of the prognostic

biomarker as a target in TC and of the expression of ZBP1 and AIM2

on PANoptosis using in vitro experiments and to characterize

the molecular mechanisms that may be involved with this target

using mRNA-seq. It aims to provide a new perspective and a solid

experimental basis for the development of therapeutic strategies

related to PANoptosis in TC.

Materials and methods

PANoptosis-related bioinformatics

analysis

The TCGA-THCA dataset was obtained from TCGA

(https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), which

includes 571 samples with clinical data from the study by Liu et

al (27). The dataset features

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) expression profiles (transcripts per

million format) of 59 paracancerous samples and 507 tumor samples.

Pearson correlation analysis identified coding genes associated

with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression across 571 RNA-seq datasets. Coding

genes with an adjusted P-value (P.adj) <0.05 were determined to

be significantly associated with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression. The

clusterProfiler package (v4.4.4) (28) in R was used to perform Gene Ontology

(GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment

analysis of these co-associated coding genes to assess their roles

in molecular composition, biological processes, molecular functions

and signaling pathways. The STRING database (29) and Cytoscape software (v3.7.2)

(30) were used to construct and

visualize the protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks of ZBP1-

and AIM2-associated coding genes, and the resulting PPIs were

analyzed using the Network Analysis and MCODE (31) apps within Cytoscape software.

Finally, the survival package (v3.3.1) (32) in R software was used to performed

log-rank tests and univariate and multivariate Cox regression

analyses to assess the associations between ZBP1- and

AIM2-associated coding genes and patient prognosis in TC.

Culture and transfection of TC

cells

Normal human thyroid cells (Nthy) and TC cell lines

(K1, TPC-1 and BCPAP) were purchased from Procell Life Science

& Technology Co., Ltd. and Wuhan SAIOS Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

All cell lines underwent DNA amplification using the 21-short

tandem repeat (STR) profiling protocol, followed by detection of

STR loci and the sex-determining gene Amelogenin on a

SeqStudio™ Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). DNA profiles of Nthy, K1, TPC-1 and BCPAP cells matched

reference profiles of cell lines in the ExPASy database (https://www.expasy.org/), with accession numbers

CVCL-2659, CVCL-2537, CVCL-6298 and CVCL-0153, respectively.

Nthy, TPC-1 and BCPAP cells were cultured in RPMI

1640 medium (cat. no. 61870-127; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 1% double antibodies (cat. no. PB180120;

Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and 10% FBS (cat.

no. 12003C; Merck KGaA) at 5% CO2 and 37°C, whereas K1

cells were maintained in Ham's F-12K medium (cat. no. 21127-022;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 5% CO2 and

37°C.

For genetic manipulation, Genomeditech (Shanghai)

Co., Ltd. synthesized short hairpin (sh)RNA constructs targeting

TFRC for knockdown and provided the

PGMLV-CMV-MCS-EF1-ZsGreen1-T2A-Puro plasmid for overexpression of

TFRC. The shRNA sequences targeting TFRC used were as

follows: 5′-CGTGAATTTAAACTCAGCAAA-3′ (shRNA sense #1);

5′-TTTGCTGAGTTTAAATTCACG-3′ (shRNA antisense #1);

5′-GCCAGCTTTACTGGAGAACTT-3′ (shRNA sense #2);

5′-AAGTTCTCCAGTAAAGCTGGC-3′ (shRNA antisense #2);

5′-GCTGGTCAGTTCGTGATTAAA-3′ (shRNA sense #3);

5′-TTTAATCACGAACTGACCAGC-3′ (shRNA antisense #3);

5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′ [negative control (NC) sense]; and

5′-ACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAA-3′ (NC antisense). BCPAP cells were

randomized into overexpression control (OV-NC) and overexpression

of TFRC (OV-TFRC) groups, whilst K1 cells were randomized into

knockdown control (KD-NC) and knockdown of TFRC (KD-TFRC) groups.

Transfections were performed using Lipo8000™

transfection reagent (cat. no. C0533-7.5 ml; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), with BCPAP cells transfected with TFRC

overexpression plasmid or its NC (blank

PGMLV-CMV-MCS-EF1-ZsGreen1-T2A-Puro plasmid) and K1 cells

transfected with TFRC shRNA or its NC (oligo control).

Cellular PANoptosis-related staining

assays

The PI/Calcein-AM Double Staining Kit (cat. no.

CA1630; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and

Apoptosis and Necrosis Detection Kit with YO-PRO-1 and PI Kit (cat.

no. C1075S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were used to

assess PANoptosis in BCPAP and K1 cells. For PI/Calcein-AM

staining, BCPAP and K1 cells were adjusted to a concentration of

1×105 cells/ml using 1X assay buffer and incubated with

Calcein-AM for 25 min at 37°C, followed by PI for 5 min at 37°C.

For YO-PRO-1/PI staining, PBS-washed BCPAP and K1 cells

(5×104 cells/ml) were inoculated in 24-well plates, and

100 µl YO-PRO-1 and PI staining was added to each well for 20 min

at 37°C. Representative images of PI/Calcein-AM and YO-PRO-1/PI

staining were captured using a BX53 fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corp.). Excitation filters were set at 535 nm for PI

(red), 495 nm for Calcein-AM (green) and 491 nm for YO-PRO-1

(green), enabling the detection of apoptosis/necroptosis, viable

cells and necroptosis/pyroptosis, respectively.

Western blot assay for PANoptosis

markers

Total proteins were extracted from BCPAP and K1

cells using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. C500005; Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd.). Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA

Protein Colorimetric Assay Kit (cat. no. E-BC-K318-M;

Elabscience®; Elabscience Bionovation Inc.), separated

using a 5 and 10% SDS-PAGE gel kit (cat. no. P1200; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and transferred onto

PVDF membranes (cat. no. 88520; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The mass of protein loaded per lane was 20 µg. Membranes were

blocked with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h and

incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C:

Vinculin mouse mAb (1:50,000; cat. no. 66305-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), CASP3 mouse mAb (1:2,000; cat. no. bsm-33284M;

BIOSS), cleaved-CASP3 mouse mAb (1:2,000; cat. no. bsm-33199M;

BIOSS), CASP1 rabbit pAb (1:2,000; cat. no. 22915-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), cleaved-CASP1 rabbit pAb (1:3,000; cat. no.

PA5-77886; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), phospho-(p)MLKL rabbit

pAb (1:2,000; cat. no. PA5-105677; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

total-(t)MLKL mouse mAb (1:50,000; cat. no. 66675-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) and tRIPK3 rabbit pAb (1:10,000; cat. no. 29080-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.). Membranes were incubated with the

following secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h: Goat

anti-mouse IgG HRP (1:4,000; cat. no. M21001L; Abmart, Inc.) and

goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP (1:4,000; cat. no. M21002L; Abmart, Inc.).

After visualization with an ECL detection kit (cat. no. 34580;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), images of membranes were captured

using the GelDoc Go Gel Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.), and band intensities were semi-quantified using ImageJ 1.0

software (National Institutes of Health).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) assay for TFRC and hub genes

Total RNA was extracted from BCPAP and K1 cells

using TRIzol™ lysis buffer (cat. no. 15596018CN;

Invitrogen™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

chloroform, followed by RNA concentration measurement using a

NanoDrop™ 8000 Spectrophotometer (cat. no. ND-8000-GL;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reverse transcription of RNA and

amplification of the target gene were performed using the FastKing

RT Kit (cat. no. KR116; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and Taq Pro

Universal SYBR qPCR Master Kit (cat. no. Q712; Vazyme Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) on a 7500 PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

conditions for reverse transcription were as follows: Incubation at

42°C for 15 min, followed by heating at 95°C for 3 min. The thermal

cycling conditions for qPCR were as follows: Denaturation at 95°C

for 10 min, followed by annealing and extension at 95°C for 15 sec

and at 60°C for 30 sec, with 45 cycles. The relative expression

level of the target gene relative to GAPDH is calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (33). The

following primer sequences were used: 5′-TTGCCCTCAACGACCACTTT-3′

[GAPDH-forward (F)]; 5′-TGGTCCAGGGGTCTTACTCC-3′ [GAPDH-reverse

(R)]; 5′-ATCTTGCGTTGTATGTTG-3′ (TFRC-F); 5′-AGTCTACCGTTCTTATCAA-3′

(TFRC-R); 5′-TCTACCTCTGTGATAACCT-3′ (CD34-F);

5′-TGAACACTGTGCTGATTA-3′ (CD34-R); 5′-GATGATGTCTTCCTTAGTGTT-3′

[lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA)-F]; 5′-AGTCAGAGTCACCTTCAC-3′

(LDHA-R); 5′-GAAGAACTGGCGGCTTAA-3′ [low-density lipoprotein

receptor (LDLR)-F]; 5′-CCTCATCCTCTGTGGTCT-3′ (LDLR-R);

5′-TAAGACAATAGAGGTATTCTG-3′ [adaptor related protein complex 1

subunit µ 2 (AP1M2-F]; 5′-GTAGACGATGACAAAGTT-3′ (AP1M2-R);

5′-CAGAATGATGATATTGGAAGTAGA-3′ [diaphanous related formin 3

(DIAPH3)-F]; 5′-CAGGTTCACATAAGTTGCTAT-3′ (DIAPH3-R);

5′-AGATGCTGCCAATAACTATG-3′ [tubulin α 1b (TUBA1B)-F];

5′-AATTCGGTCCAACACAAG-3′ (TUBA1B-R); 5′-AACAACATTCGTAACTCTC-3′

[citron ρ-interacting serine/threonine kinase (CIT)-F];

5′-TTCTTCTCTGGTTCATCA-3′ (CIT-R); 5′-CAACCTCGTAGACTCCTA-3′ [dynamin

3 (DNM3)-F]; 5′-TCCTCTGAAGAATACAACTG-3′ (DNM3-R);

5′-CGAAGAGGAATTGAGAACTACTAT-3′ [tetraspanin 15 (TSPAN15)-F];

5′-GCCACAGCACTTGAACTT-3′ (TSPAN15-R); 5′-GATTACTATGGTCACTTG-3′ [DEP

domain containing 1B (DEPDC1B)-F]; 5′-CATCATCCTCATCAATAG-3′

(DEPDC1B-R); 5′-GACCACTACCTAACTCAG-3′ [IQ motif containing GTPase

activating protein 3 (IQGAP3)-F]; 5′-GCATCATCAACAACTTCTA-3′

(IQGAP3-R); 5′-AACAACAACTGGAACTTCAA-3′ (CD24-F);

5′-CTTGGTGGTGGCATTAGT-3′ (CD24-R); 5′-ATTAACCACTATCACCAT-3′

[phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 3 (PIK3R3)-F]; and

5′-TATTCTTCATACAGCCTAT-3′ (PIK3R3-R).

TFRC-related mRNA-seq and

bioinformatics analysis

Shanghai OE Biotech Co., Ltd performed sequencing of

K1 cells from the KD-NC and KD-TFRC groups, including total RNA

extraction, quality control, library construction, mRNA-seq on a

sequencing platform (NovaSeq 6000; Illumina, Inc.) and subsequent

bioinformatics analysis. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol

reagent (15596026CN; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA purity

and quantification were evaluated using a spectrophotometer

(NanoDrop 2000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA integrity was

assessed using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100; Agilent, Inc.). The

libraries were then constructed using the VAHTS Universal V6

RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (NR616; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The

libraries were sequenced on a Novaseq 6000 sequencing platform and

150 bp paired-end reads were generated. For quality control, RseQC

(v4.0.0) (34), fastp (v0.20.1)

(35), hisat2 (v2.1.0) (36) and htseq-count (v0.11.2) (37) were applied to perform RNA integrity

assessment, raw read quality filtering, base-level quality control,

genome alignment and gene quantification, respectively. A total of

41.70 G clean data was generated from six K1 cell samples, with Q30

base range from 93.99–94.24%. Clean reads were mapped to the

GRCh38.p13 reference genome with alignment rates of 97.81–98.13%.

For downstream analysis, DESeq2 (v1.22.2) (38) was used to identify TFRC-associated

differentially expressed (DE)-mRNAs; clusterProfiler (v4.4.4)

(28) for GO, KEGG and gene set

enrichment analysis (GSEA) enrichment analyses; ggplot (v3.3.6)

(39) for data visualization; and

the Network Analysis and MCODE (31) apps within Cytoscape software

(v3.7.2) for PPI network construction and analysis. The shared

genes between the ZBP1-related and the AIM2-related coding genes

were obtained using the jvenn Web (https://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/example.html).

Statistical analyses

All data were replicated at least three times, and

GraphPad Prism 9.0.0 software (Dotmatics) was used for statistical

analyses, including Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test and

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's highly-significant differences

post-hoc test or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's

post-hoc test, as well as data visualization. Data were expressed

as mean ± standard deviation. Pearson correlation analysis was used

to identify coding genes associated with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression

in the TCGA-THCA dataset. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Identification and enrichment analysis

of ZBP1- and AIM2-related coding genes

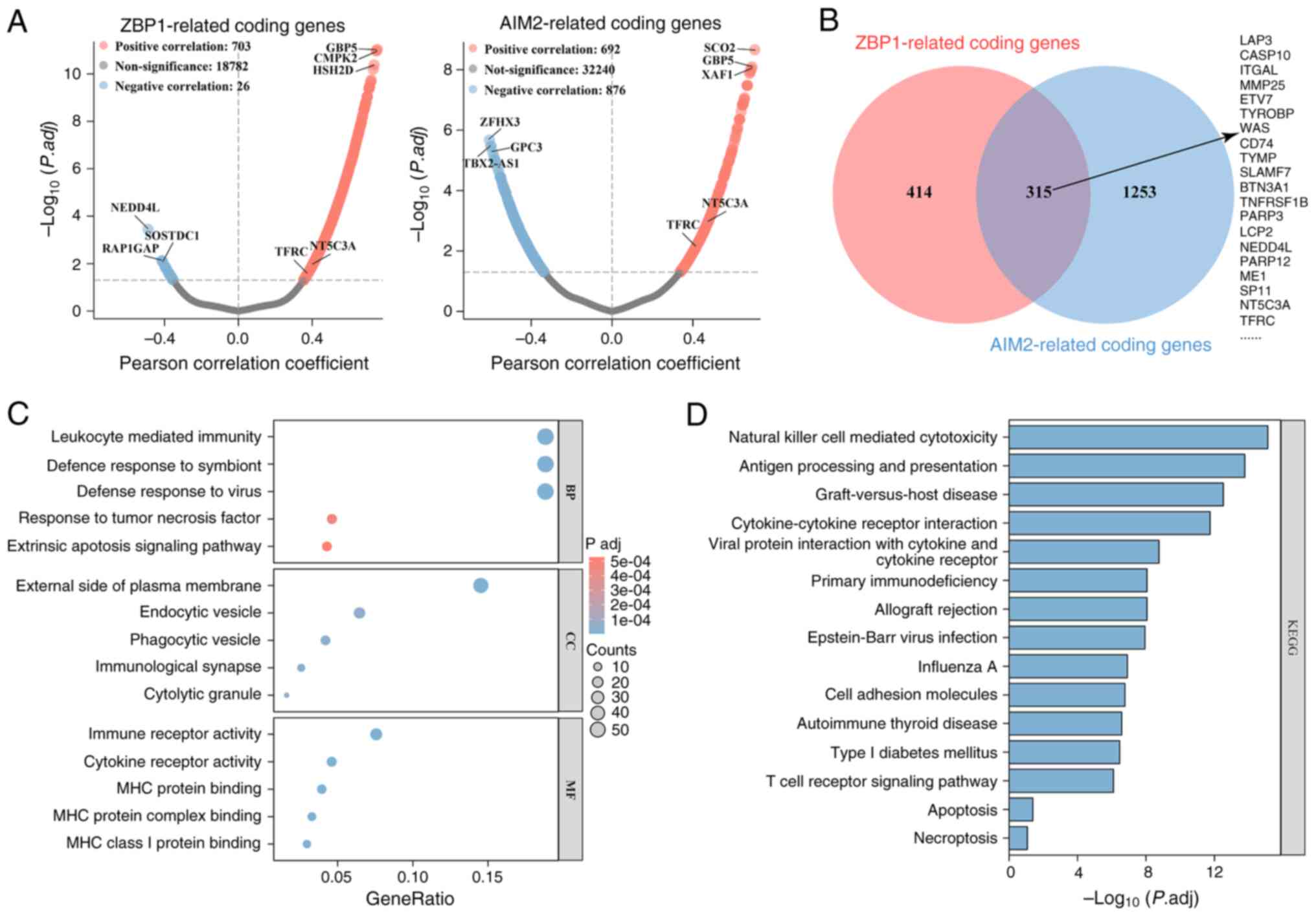

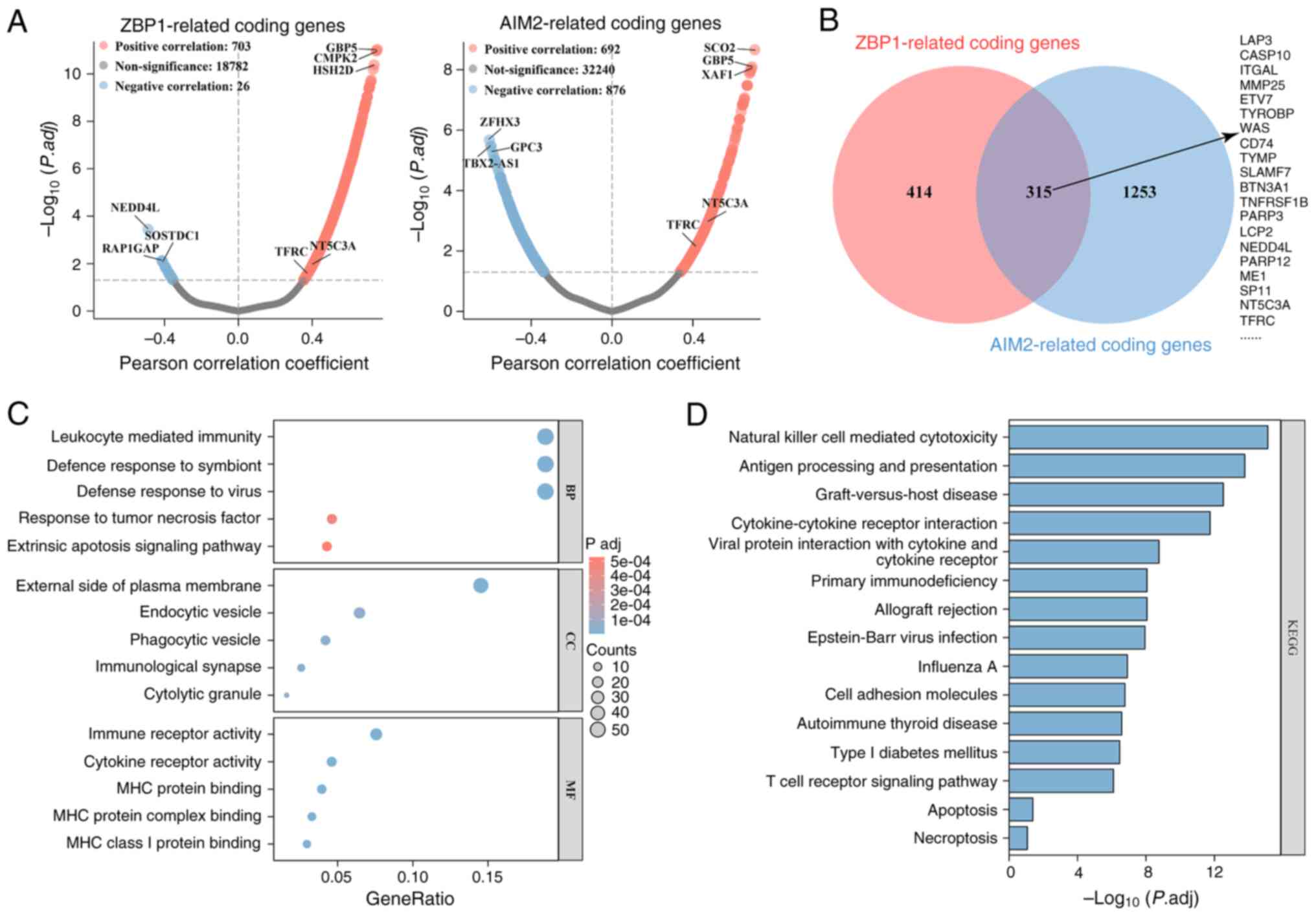

ZBP1 and AIM2 are well-established sensors of

PANoptosis (7–11). To identify potential regulators of

this process in TC, the present study analyzed protein-coding genes

correlated with ZBP-1 and AIM2 expression in the TCGA-THCA cohort.

A total of 729 and 1,568 genes were demonstrated to be

significantly correlated with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression,

respectively (P.adj <0.05; Fig.

1A). Venn diagram analysis revealed that there were 315 shared

genes, including leucine aminopeptidase 3, CASP10, integrin subunit

α L, 5′-nucleotidase cytosolic IIIA (NT5C3A) and TFRC

(Fig. 1B). Functional enrichment

analysis indicated that these genes were enriched in membrane- and

vesicle-associated proteins, and were associated with ‘leukocyte

mediated immunity’, ‘response to tumor necrosis factor’, ‘extrinsic

apoptotic signaling pathway’, ‘immune receptor activity’ and ‘tumor

necrosis factor’ (Fig. 1C). They

were also enriched in pathways associated with ‘natural killer cell

mediated cytotoxicity’, ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’,

‘cell adhesion molecules’, ‘autoimmune thyroid disease’,

‘apoptosis’ and ‘necroptosis’ (Fig.

1D). Collectively, these findings suggest that, in TC, coding

genes associated with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression are primarily

involved in immunity processes, apoptosis, necroptosis and

cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction.

| Figure 1.Identification and enrichment

analysis of ZBP1- and AIM2-related coding genes. (A) Coding genes

associated with ZBP1 and AIM2 expression in The Cancer Genome

Atlas-Thyroid Cancer cohort were identified using Person

correlation analysis. The volcano plots exhibit the results, with

blue and red dots representing genes negatively and positively

correlated with ZBP1 or AIM2, respectively. (B) Overlap and union

of ZBP1- and AIM2-related coding genes, visualized using the jvenn

Web (https://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/example.html).

(C) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of ZBP1- and AIM2-associated

coding genes. The bubble plot presents the top five terms for BP,

CC and MF. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of ZBP1- and

AIM2-related coding genes. The bar chart depicts the top 15

pathways ranked by-log10(P.adj). ZBP1, Z-DNA-binding

protein 1; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; BP, biological process; CC,

cellular component; MF, molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. |

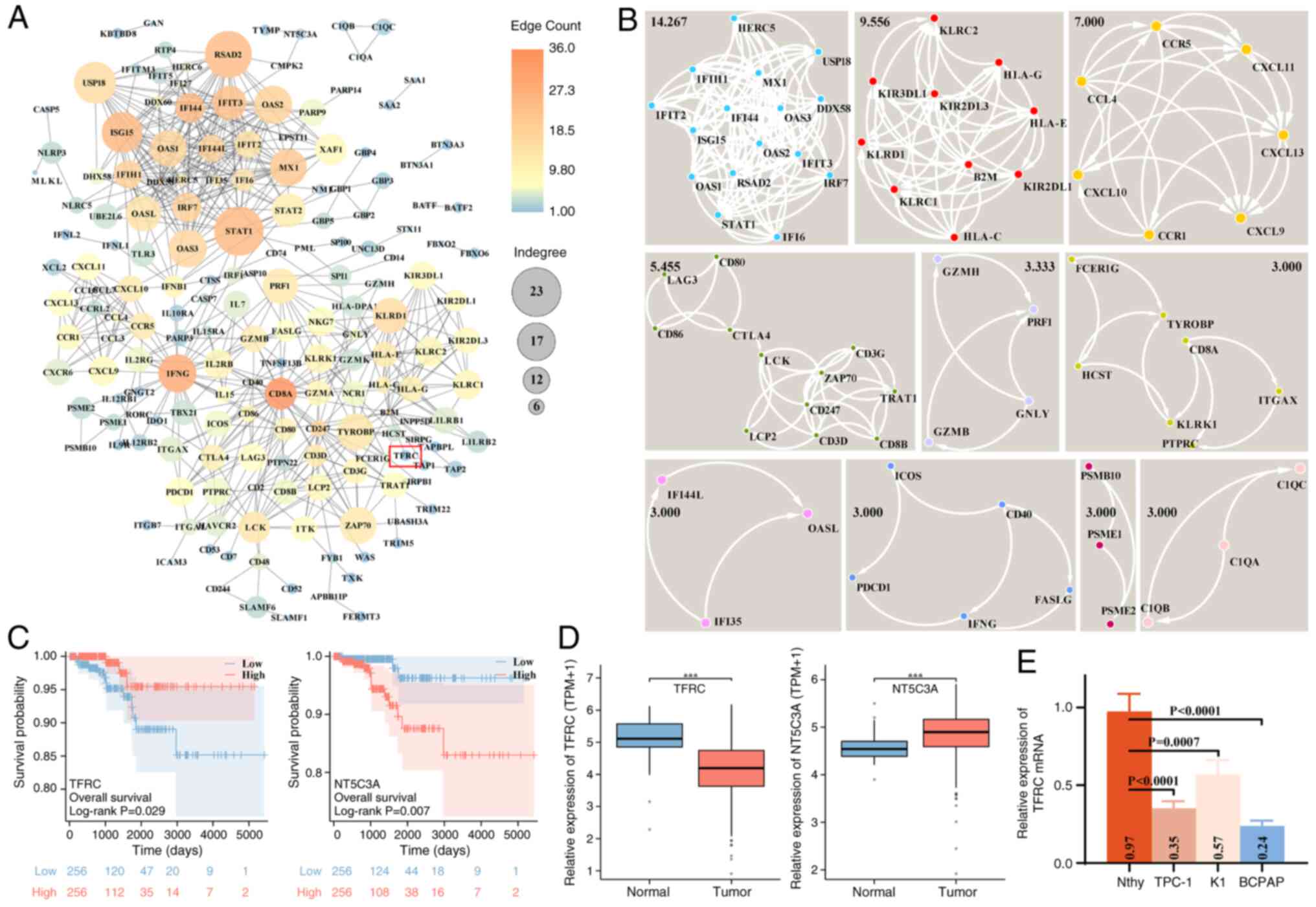

TFRC is associated with the prognosis

of TC

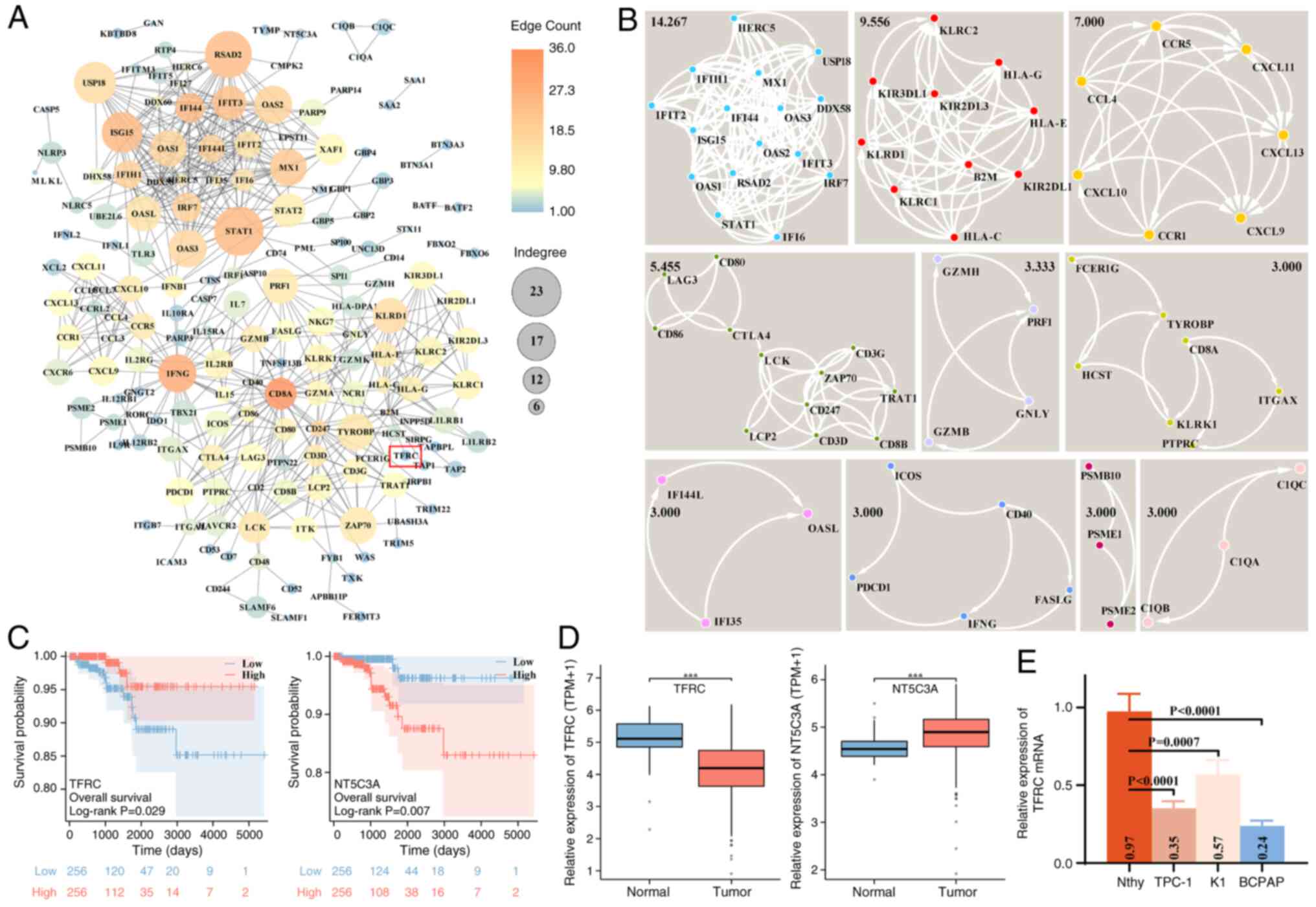

To further identify hub genes associated with ZBP-1

and AIM2 expression in TC, a PPI network of 315 coding genes was

constructed. This network contained 178 genes (nodes) and 608

relationship pairs (edges), using a minimum required interaction

score of 0.9 in the STRING database (Fig. 2A). Network analysis revealed that

the top five genes ranked by edge count were CD8A, interferon γ

(IFNG), interferon induced protein 44, signal transducer and

activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and interferon-induced

15 KDa protein (ISG15), whereas the top five ranked by

indegree were STAT1, radical S-adenosyl methionine domain

containing 2, ubiquitin specific peptidase 18, ISG15 and

IFNG. To identify the key sub-networks, MCODE analysis was

performed, and 10 clusters (clustering score ≥3) were detected

(Fig. 2B). The sub-network with the

highest clustering score (14.267) contained 16 genes (nodes) and

107 relationship pairs (edges), and was enriched in biological

processes such as inflammatory response, apoptosis, oxidative

stress and immune response, as well as pathways such as Toll-like

receptor, retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like receptor and

cytosolic DNA-sensing. Moreover, the present study screened the

genes associated with TC prognosis in this PPI network (178

genes/nodes). Univariate Cox analysis suggested that 15 coding

genes were significantly associated with the prognosis of patients

with TC. Furthermore, multivariate Cox analysis identified two

independent risk factors, including TFRC and NT5C3A (Table I). Log-rank analysis demonstrated

that low TFRC expression and high NT5C3A expression predicted

reduced overall survival in patients with TC within 5,000 days

(Fig. 2C). Consistently, TCGA-THCA

expression data revealed that TFRC was downregulated and NT5C3A

upregulated in TC tissues, compared with in normal tissues

(Fig. 2D). Notably, the expression

of TFRC and NT5C3A correlated positively with ZBP-1 and AIM2

(Fig. 1A). Although NT5C3A also

demonstrated significant association with patient survival, the

present study subsequently focused on TFRC due to its established

evidence across multiple cell death pathways, indicating greater

potential for mechanism exploration. For experimental validation,

TFRC expression was reduced in TC cell lines (TPC-1, K1 and BCPAP),

with the lowest expression observed in BCPAP cells (Fig. 2E), consistent with TCGA-THCA

profiles. Collectively, these findings suggest that TFRC functions

as a prognostic factor and a potential regulator of PANoptosis in

TC.

| Figure 2.PPI network construction of ZBP1- and

AIM2-related coding genes and prognostic analysis of hub genes in

TC. (A) PPI networks of ZBP1 and AIM2 co-associated genes,

constructed using the STRING database and visualized using

Cytoscape software. Node color and size indicate edge counts and

indegree, respectively. (B) Sub-networks within the PPI network

were identified using the MCODE app in Cytoscape software. Black

numbers denote the clustering scores of each sub-network. (C)

Prognostic significance of TFRC and NT5C3A expression in patients

with TC, evaluated using log-rank analysis in the TCGA-THCA cohort.

(D) Differential expression of TFRC and NT5C3A in the TCGA-THCA

cohort. (E) Relative TFRC mRNA expression in Nthy and TC cells

(TPC-1, K1 and BCPAP), assessed using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR assay. ***P<0.001. PPI,

protein-protein interaction; ZBP1, Z-DNA-binding protein 1; AIM2,

absent in melanoma 2; TC, thyroid cancer; TFRC, transferrin

receptor; NT5C3A, 5′-nucleotidase cytosolic IIIA; TCGA-THCA, The

Cancer Genome Atlas-Thryoid Cancer; Nthy, normal human thyroid

epithelial; TPM, transcripts per million. |

| Table I.Cox regression analysis of

Z-DNA-binding protein 1 and absent in melanoma 2 expression-related

coding genes in thyroid cancer. |

Table I.

Cox regression analysis of

Z-DNA-binding protein 1 and absent in melanoma 2 expression-related

coding genes in thyroid cancer.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gene (low vs. high

expression) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| ISG15 | 0.305

(0.098–0.949) | 0.040 | 1.339

(0.249–7.211) | 0.734 |

| IL2RB | 0.208

(0.059–0.732) | 0.014 | 0.521

(0.077–3.542) | 0.505 |

| PARP9 | 0.318

(0.102–0.988) | 0.048 | 0.723

(0.136–3.839) | 0.704 |

| IFIT2 | 0.320

(0.103–0.992) | 0.048 | 1.480

(0.305–7.176) | 0.626 |

| CXCL10 | 0.304

(0.098–0.942) | 0.039 | 1.062

(0.195–5.765) | 0.945 |

| CD8B | 0.318

(0.103–0.987) | 0.047 | 0.798

(0.193–3.300) | 0.755 |

| HLA-G | 0.215

(0.061–0.755) | 0.016 | 0.289

(0.055–1.525) | 0.143 |

| PSME2 | 0.246

(0.070–0.866) | 0.029 | 2.505

(0.350–17.920) | 0.360 |

| PSME1 | 0.073

(0.010–0.554) | 0.011 | 0.119

(0.010–1.416) | 0.092 |

| RTP4 | 0.144

(0.033–0.636) | 0.011 | 0.434

(0.063–3.006) | 0.398 |

| GBP2 | 0.279

(0.089–0.869) | 0.028 | 0.701

(0.147–3.350) | 0.656 |

| HERC6 | 0.280

(0.090–0.872) | 0.028 | 1.246

(0.255–6.082) | 0.786 |

| TFRC | 1.270

(1.077–1.949) | 0.041 | 1.146

(1.035–1.618) | 0.019 |

| NT5C3A | 4.773

(1.359–16.759) | 0.015 | 7.464

(1.387–40.175) | 0.009 |

| PARP14 | 0.206

(0.059–0.724) | 0.014 | 0.466

(0.078–2.781) | 0.402 |

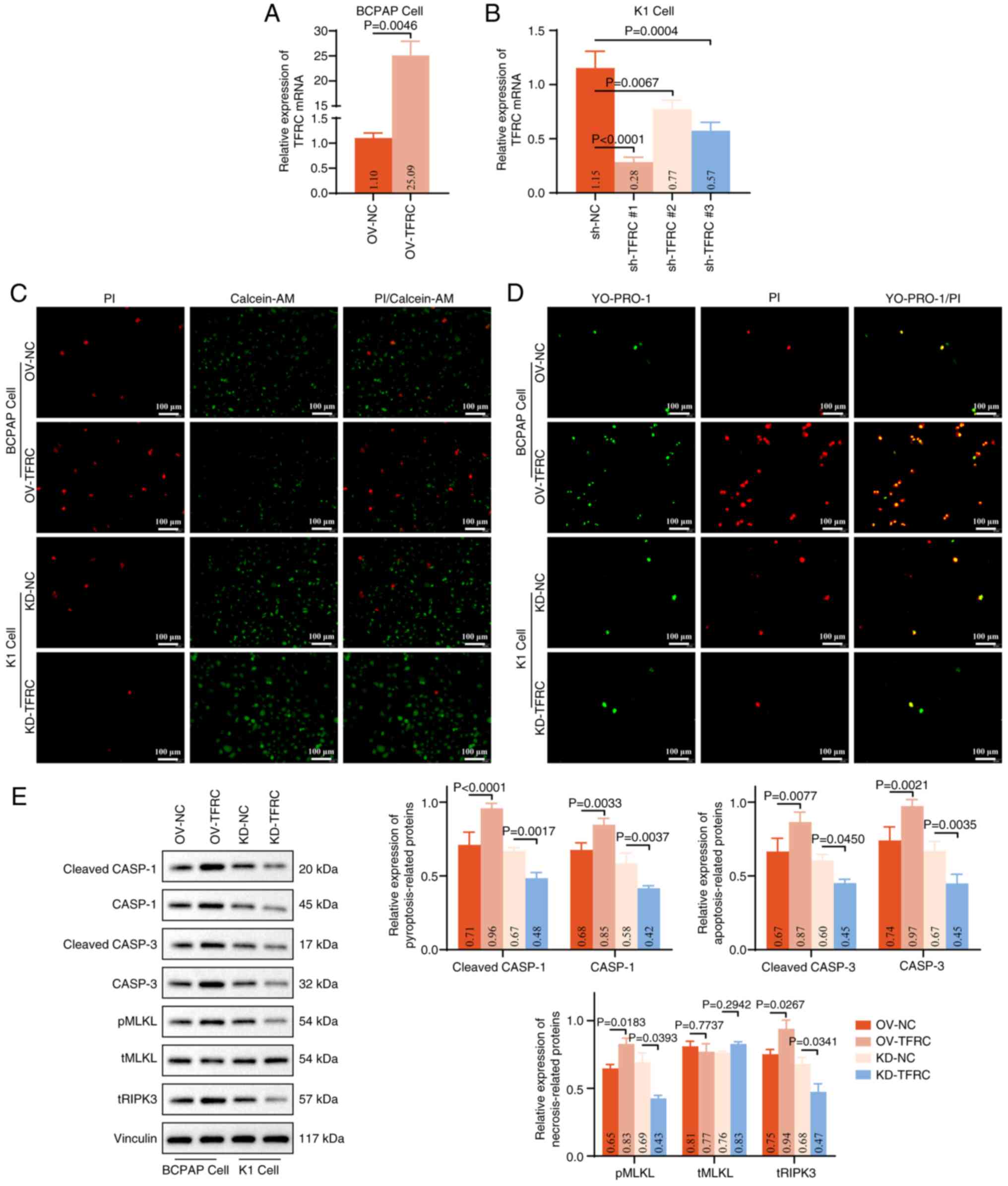

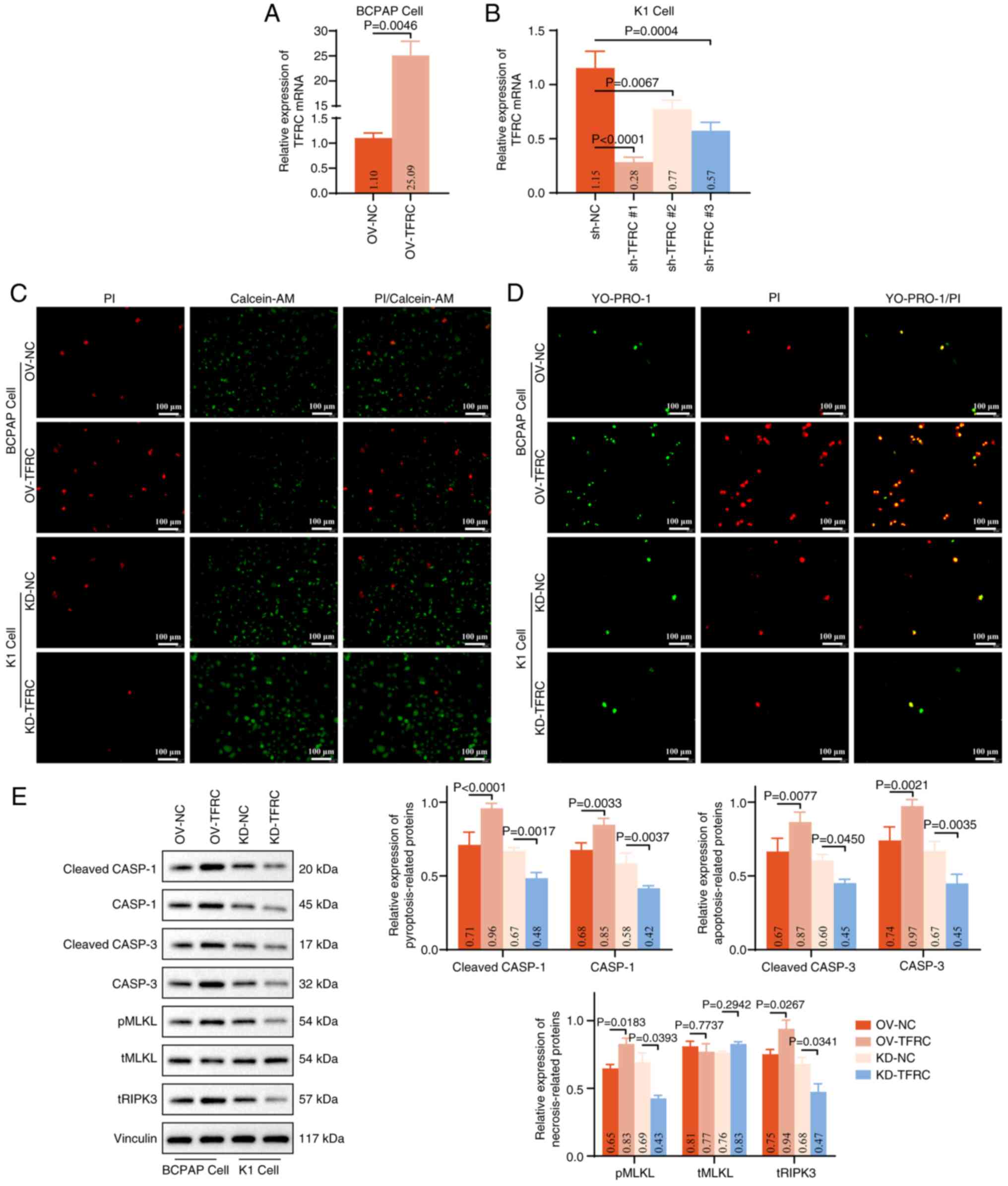

TFRC facilitates PANoptosis for

TC

To further investigate the role of TFRC in

regulating PANoptosis in TC cells in vitro, the present

study performed in vitro functional experiments. TFRC was

overexpressed in BCPAP cells, which exhibit relatively low

endogenous TFRC expression, and silenced in K1 cells, which express

higher TFRC levels. RT-qPCR demonstrated that

PGMLV-CMV-MCS-EF1-ZsGreen1-T2A-Puro and shRNA effectively regulated

the level of TFRC mRNA in BCPAP and K1 cells (Fig. 3A and B). Calcein-AM/PI staining

revealed a marked increase in PI+ BCPAP cells in the

OV-TFRC group, whereas a notable decrease in PI+ K1

cells was observed in the KD-TFRC group, compared with their

respective controls (Fig. 3C).

These results indicate that TFRC facilitates TC cell death.

| Figure 3.TFRC contributes to PANoptosis in TC

cells. Effects of (A) PGMLV-CMV-MCS-EF1-ZsGreen1-T2A-Puro and (B)

shRNA transfection on the expression of TFRC mRNA in BCPAP

and K1 cells, assessed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

assay. (C) PI/Calcein-AM staining was performed to assess the

effect of TFRC on cell death in BCPAP (OV-NC and OV-TFRC groups)

and K1 (KD-NC and KD-TFRC groups) cells. PI (red) and Calcein-AM

(green) label dead and viable cells, respectively. (D) YO-PRO-1/PI

staining was performed to evaluate pyroptosis, apoptosis and

necroptosis in BCPAP and K1 cells following exogenous modulation of

TFRC expression. YO-PRO-1 (green) indicates apoptotic or

necroptotic cells, whereas PI (red) labels necroptotic or

pyroptotic cells. (E) Western blot analysis of markers associated

with pyroptosis (cleaved-CASP1/CASP1), apoptosis

(cleaved-CASP3/CASP3) and necroptosis (pMLKL/tMLKL and tRIPK3),

with corresponding quantitative analyses. TFRC, transferrin

receptor; sh, short hairpin; OV, overexpression; NC, negative

control; KD, knockdown; CASP; caspase; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase

domain like pseudokinase; pMLKL, phospho-MLKL; tMLKL, total-MLKL;

tRIPK3, total receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 3. |

To further distinguish the mode of cell death,

YO-PRO-1/PI staining was performed. Overexpression of TFRC notably

increased the proportion of YO-PRO-1-positive cells

(apoptosis/necroptosis) and PI-positive cells

(necroptosis/pyroptosis) in BCPAP cells, whereas the opposite trend

was observed following TFRC knockdown (Fig. 3D). These findings suggest that TFRC

promotes multiple forms of regulated cell death, including

pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis, in TC cells. Consistent with

these observations, western blot analysis revealed that, compared

with in the OV-NC or KD-NC groups, the expression levels of

cleaved-CASP1, CASP1, cleaved-CASP3, CASP3, pMLKL and tRIPK3

proteins were significantly augmented in BCPAP cells overexpressing

TFRC, but reduced in K1 cells with TFRC knockdown (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these results

indicate that overexpression of TFRC drives PANoptosis in TC

cells.

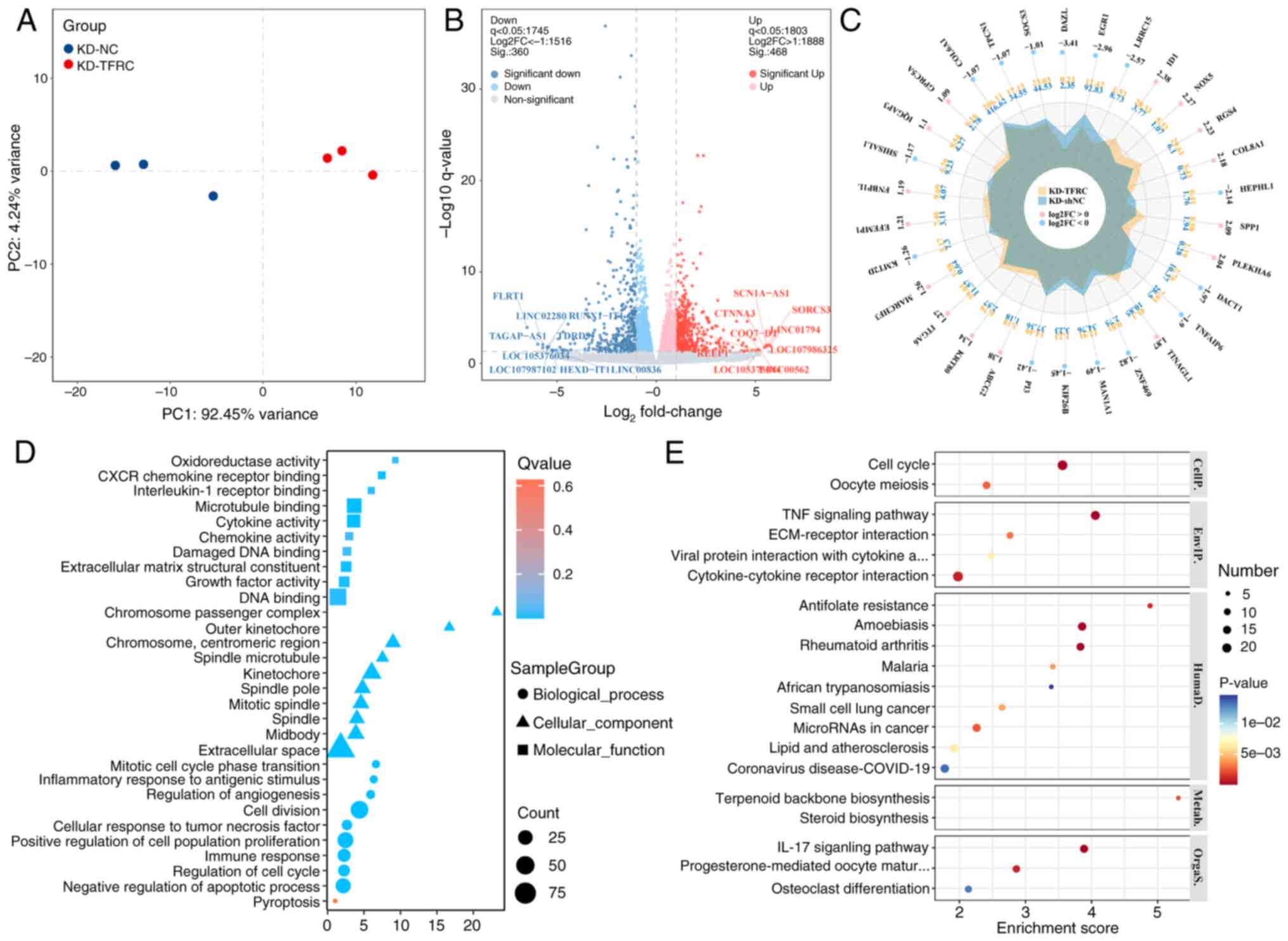

Identification and enrichment analysis

of TFRC-associated DE-mRNAs

To explore the potential mechanism underlying

TFRC-associated PANoptosis in TC cells, mRNA-seq was performed on

K1 cells from the KD-NC and KD-TFRC groups. The results

demonstrated that mRNA expression profiles clustered tightly within

groups, but were clearly separated between groups, indicating

distinct gene expression patterns (Fig.

4A). Compared with the KD-NC group, the KD-TFRC group exhibited

360 significantly downregulated DE-mRNAs and 468 significantly

upregulated DE-mRNAs (Fig. 4B).

Radar plots highlighted the top 30 DE-mRNAs ranked by

|log2FoldChange (FC)|, with inhibitor of DNA binding 1,

NADPH oxidase 5, regulator of G protein signaling 4, collagen type

VIII α1 chain and secreted phosphoprotein 1 among the most

upregulated, and deleted in azoospermia like, early growth response

1, leucine rich repeat containing 15, hephaestin like 1 and

dishevelled binding antagonist of β catenin 1 among the most

downregulated (Fig. 4C). GO

enrichment analysis indicated that TFRC-associated DE-mRNAs were

predominantly localized to the extracellular matrix and enriched in

processes such as ‘pyroptosis’, ‘negative regulation of apoptotic

process’, ‘immune response’ and ‘cellular response to tumor

necrosis factor’ (Fig. 4D). KEGG

enrichment analysis further demonstrated enrichment in ‘cell

cycle’, ‘TNF signaling pathway’, ‘ECM-receptor interaction’,

‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ and ‘IL-17 signaling

pathway’ (Fig. 4E). Consistently,

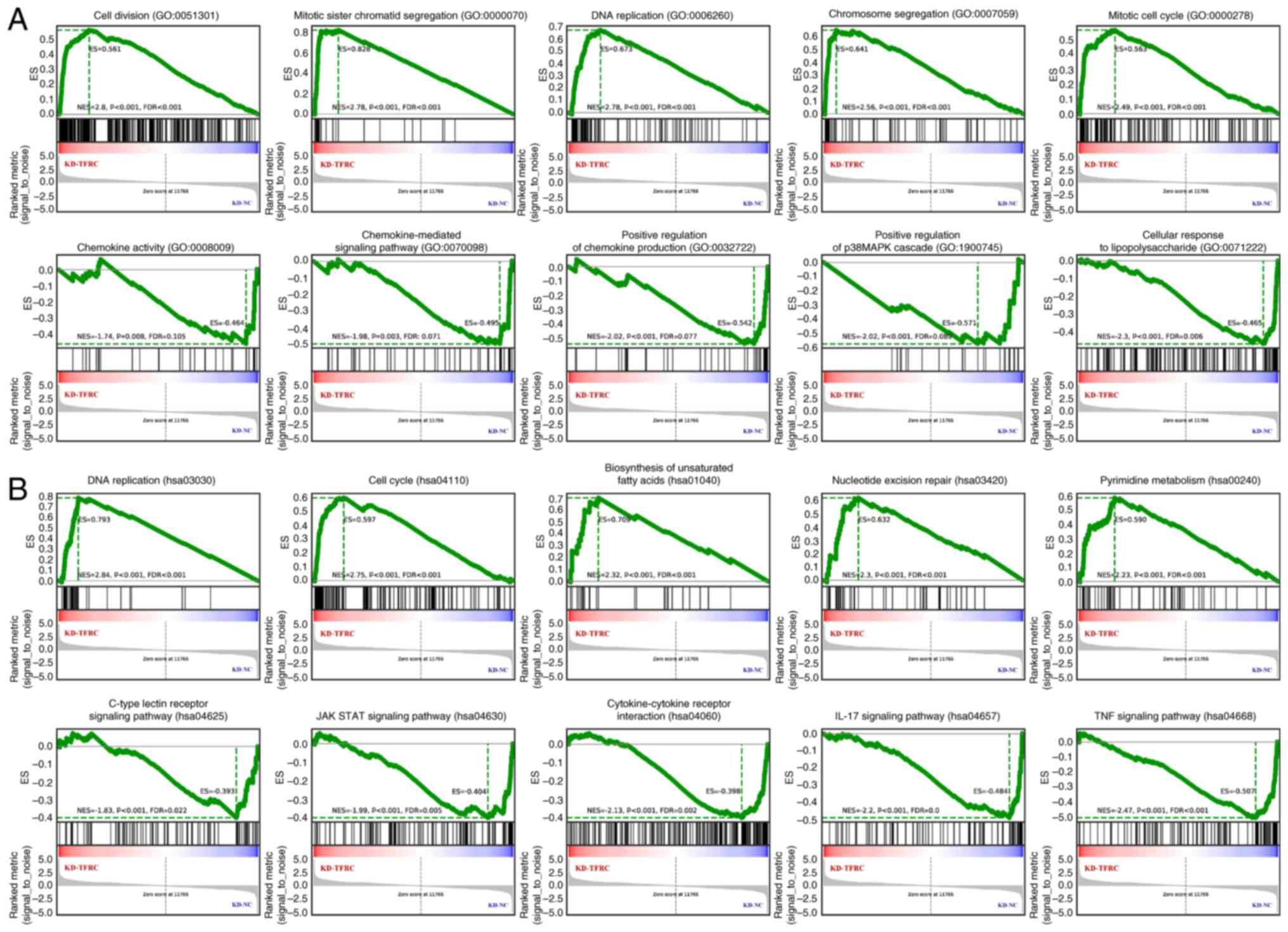

GSEA analysis revealed that knockdown of TFRC was associated with

cell proliferation, unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis and

pyrimidine metabolism, whilst suppressing immune-related processes

(Fig. 5). Collectively, these

findings suggest that TFRC-associated DE-mRNAs are mainly involved

in regulating the cell cycle, apoptosis, necrotic apoptosis,

pyroptosis, angiogenesis, oxidative stress and immunity, thereby

reflecting the molecular mechanisms of TFRC-mediated PANoptosis in

TC cells.

Identification of hub genes for

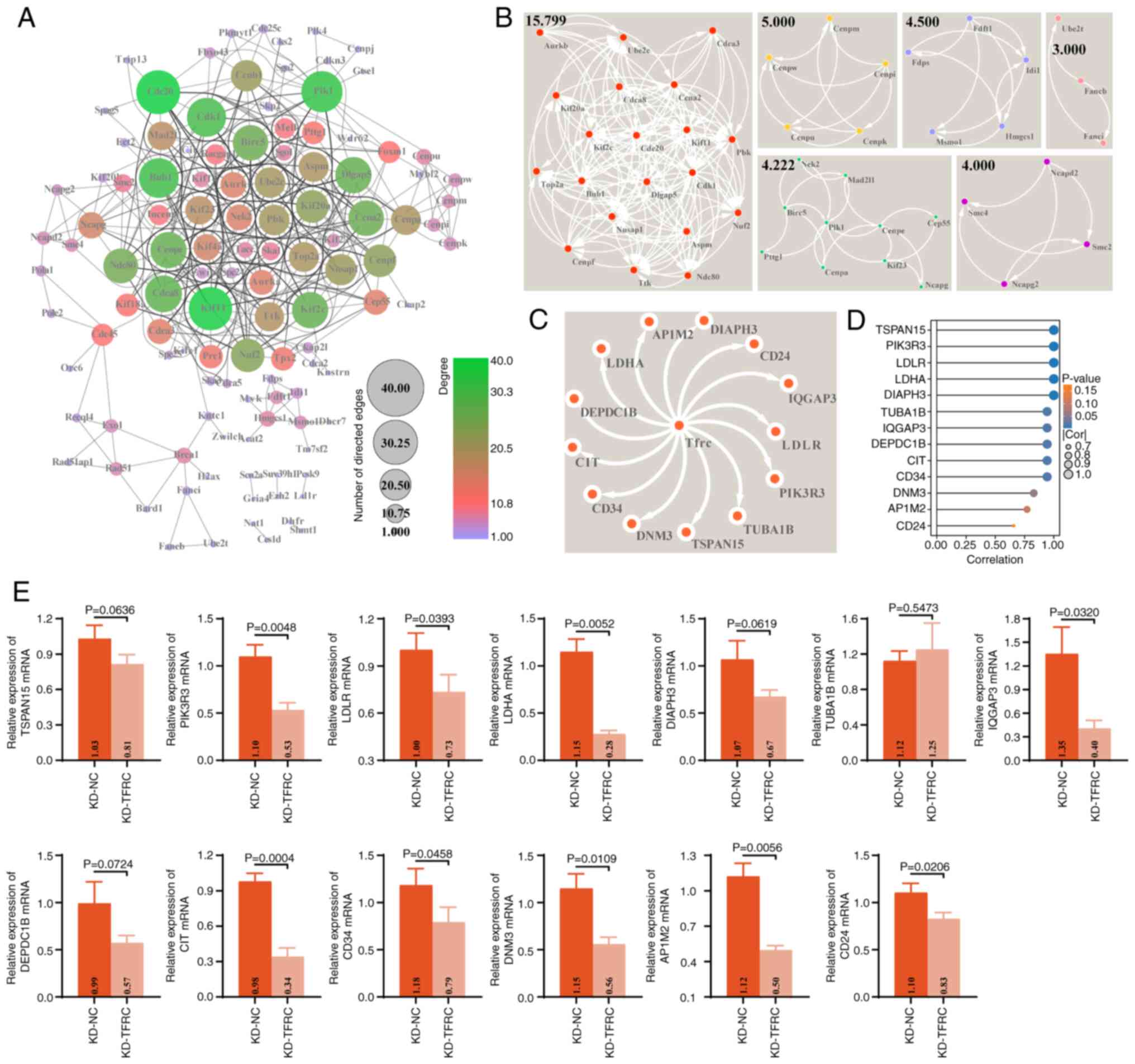

TFRC-associated DE-mRNAs

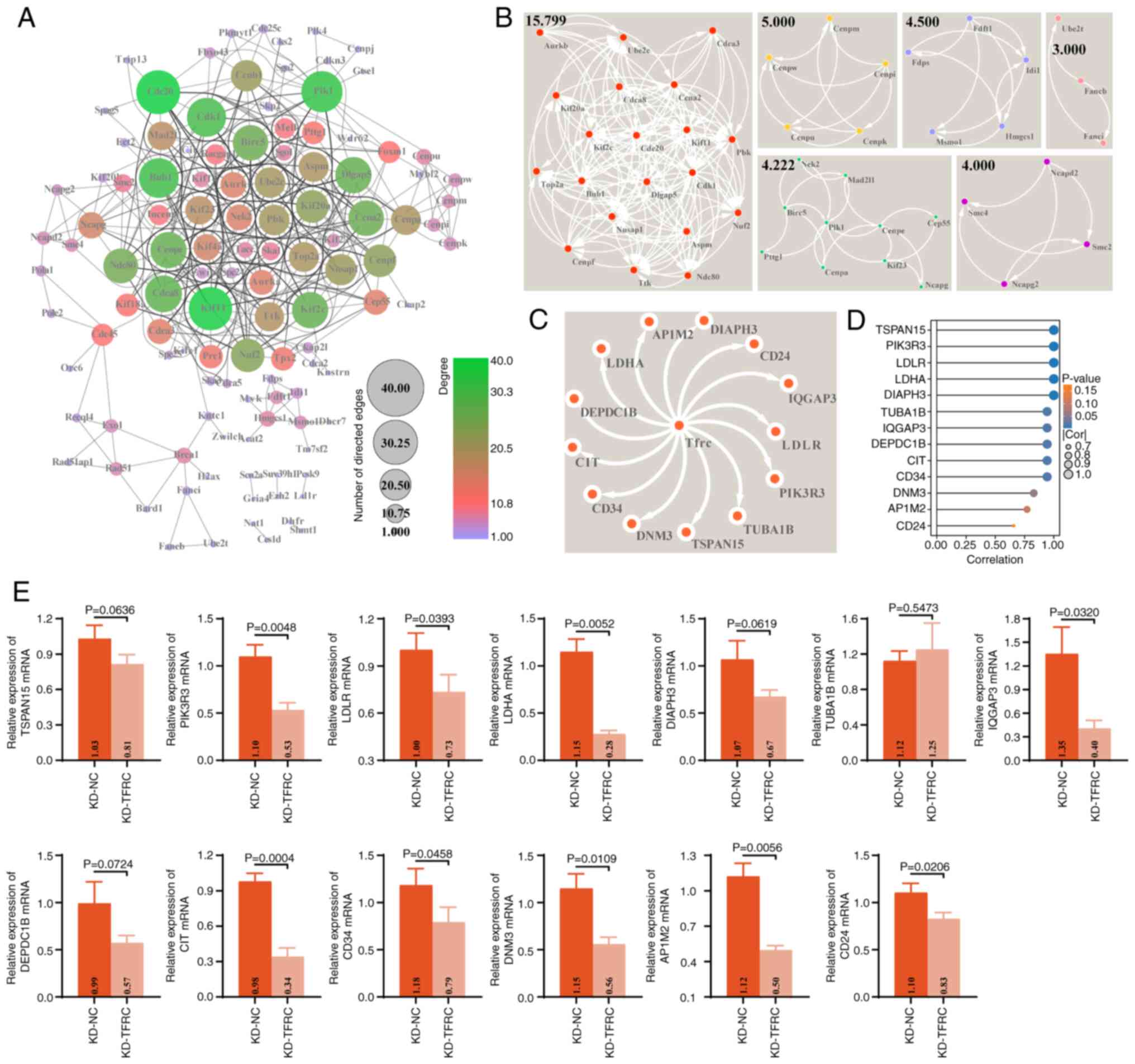

The present study further constructed a PPI network

comprising 828 TFRC expression-associated DE-mRNAs. This PPI

network consisted of 122 genes and 535 interrelationship pairs,

with the top five hub genes ranked by degree centrality being

CDC20, kinesin family member 11, polo like kinase 1, budding

uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 (yeast homolog) and CDK1

(Fig. 6A). MCODE analysis further

identified six sub-networks (clustering scores ≥3) (Fig. 6B). The most notable sub-network,

with a clustering score of 15.789, contained 20 genes and 150

interaction pairs, including assembly factor for spindle

microtubule, aurora kinase B, cell division cycle-associated

protein 1 and centromere protein f and kinesin family

member 2C, which are primarily involved in regulating the cell

cycle and immunity (40–44). Notably, the STRING database

predicted potential interactions between TFRC and 13 genes, namely

CD34, LDHA, LDLR, AP1M2, DIAPH3, TUBA1B, CIT, DNM3, TSPAN15,

DEPDC1B, IQGAP3, CD24 and PIK3R3 (Fig. 6C). Consistently, mRNA expression

profile of K1 cells revealed a strong positive correlation between

TFRC expression and the mRNAs levels of these genes (Fig. 6D). RT-qPCR revealed that TFRC

knockdown led to significant reductions in the mRNA levels of

PIK3R3, LDLR, LDHA, IQGAP3, CIT, CD34, DNM3, AP1M2 and

CD24 in K1 cells, compared with controls (Fig. 6E), which was consistent with the

results of the correlation analysis (Fig. 6D). Collectively, these findings

suggest that the pro-PANoptotic role of TFRC in TC may be mediated,

at least in part, through its association with these 13 genes.

| Figure 6.PPI network of TFRC-associated

DE-mRNAs in thyroid cancer. (A) PPI network of TFRC-associated

DE-mRNAs constructed and visualized in Cytoscape software. Node

color and size represent degree and indegree, respectively. (B)

Sub-networks within the PPI network identified using the MCODE app

in Cytoscape software. (C) Predicted TFRC-interacting genes

obtained from the STRING database (minimum required interaction

score, 0.4). (D) Lollipop plot showing the correlation between TFRC

and the expression of CD34, LDHA, LDLR, AP1M2, DIAPH3, TUBA1B,

CIT, DNM3, TSPAN15, DEPDC1B, IQGAP3, CD24 and PIK3R3 in

the mRNA expression profiles of K1 cells (KD-NC and KD-TFRC

groups). (E) Effects of TFRC knockdown on the mRNA expressions of

CD34, LDHA, LDLR, AP1M2, DIAPH3, TUBA1B, CIT, DNM3, TSPAN15,

DEPDC1B, IQGAP3, CD24 and PIK3R3 in K1 cells, assessed

using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. PPI, protein-protein

interaction; DE-mRNAs, differentially expressed mRNAs; TFRC,

transferrin receptor; KD, knockdown; NC, negative control; LDHA,

lactate dehydrogenase A; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor;

AP1M2, adaptor related protein complex 1 subunit µ 2; DIAPH3,

diaphanous related formin 3; TUBA1B, tubulin α 1b; CIT, citron

ρ-interacting serine/threonine kinase; DNM3, dynamin 3; TSPAN15,

tetraspanin 15; DEPDC1B, DEP domain containing 1B; IQGAP3, IQ motif

containing GTPase activating protein 3; PIK3R3,

phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 3. |

Discussion

The present study identified 315 coding genes

associated with ZBP-1 and AIM2 expression, among which TFRC and

NT5C3A emerged as significantly associated with the prognosis of

patients with TC. Although NT5C3A also demonstrated a significant

association with patient survival and represents a promising

candidate for future studies, the present study subsequently

focused on TFRC due to its established evidence across multiple

cell death pathways, indicating greater potential for mechanism

exploration in the context of PANoptosis. Notably, TFRC mRNA was

expressed at low levels in TC cells (TPC-1, K1 and BCPAP) yet

facilitated PANoptosis process. Notably, in TFRC-related

experiments, inducers were not employed to trigger PANoptosis in TC

cells. Since Malireddi et al (45) first proposed PANoptosis,

PANoptosis-related studies have not utilized induction agents, to

the best of our knowledge (46–53).

This may be due to the lack of specific PANoptosis inducers.

Therefore, in subsequent experiments in the present study, an

inducer for treatment was not used.

TFRC has previously been implicated in the

regulation of cell death. Earlier studies reported that TFRC

primarily promotes ferroptosis, as reported in endometrial cancer

(54), sepsis-associated

encephalopathy (55) and colorectal

cancer (21). In addition, TFRC has

been reported to regulate apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma

cells (56), pyroptosis in sheep

hepatocytes and hepatocytes (57),

and necroptosis in placenta (58).

However, its role in TC has remained unexplored, despite

bioinformatics analyses suggesting TFRC as a ferroptosis-related

feature predictive of TC prognosis (17,18).

Therefore, the present study refined the understanding of

TFRC-mediated cell death and demonstrated, for the first time to

the best of our knowledge, its involvement in PANoptosis process in

TC.

Furthermore, to elucidate the molecular mechanism

underlying TFRC regulation of PANoptosis, the present study

performed mRNA-seq and identified 828 TFRC-associated DE-mRNAs

enriched in biological processes and pathways including cell cycle,

apoptosis, necrotic apoptosis, pyroptosis, angiogenesis, oxidative

stress and immunity. Among these, 13 DE-mRNAs (CD34, LDHA, LDLR,

AP1M2, DIAPH3, TUBA1B, CIT, DNM3, TSPAN15, DEPDC1B, IQGAP3,

CD24 and PIK3R3) were predicted to interact with TFRC

and displayed a positive correlation with its expression in TC.

Notably, these DE-mRNAs are implicated in the progression of TC

process and functionally associated with apoptosis, necroptosis and

pyroptosis. CD34, LDHA, and LDLR are well-established markers of

angiogenesis, glycolysis and cholesterol metabolism, respectively,

in malignant tumors, and have also been associated with apoptotic

and pyroptotic pathways (59–61).

Moreover, DNM3 has been reported to be markedly downregulated in

TCs, where it facilitates tumor cell death (62). DIAPH3, DEPDC1B, CD24 and PIK3R3 have

each been implicated in the regulation of tumor cell death

(63,64). Notably, the present study

demonstrated that TFRC expression was positively correlated with

these DE-mRNAs, and its knockdown effectively reduced the levels of

PIK3R3, LDLR, LDHA, IQGAP3, CIT, CD34, DNM3, AP1M2h and CD24.

However, although the present study identified 13 TFRC-interacting

DE-mRNAs, none have been directly established as core regulators of

PANoptosis in existing literature. Instead, these genes are

primarily associated with distinct biological processes such as

angiogenesis (CD34), cholesterol metabolism (LDLR)

and cytoskeletal organization (DIAPH3). Several, including

DIAPH3, DEPDC1B, CD24 and PIK3R3, have been

associated with apoptosis or other forms of regulated cell death,

but not to the integrated PANoptosis pathway (59–64).

This suggests that TFRC may orchestrate PANoptosis, not through

direct engagement of these DE-mRNAs as PANoptosis-specific

effectors, but by modulating broader networks involving immunity,

metabolism and stress response.

Among these, the interaction between TFRC and LDHA

may link glycolysis and lactylation modification to the PANoptosis

process. LDHA is the key enzyme catalyzing the final step of

glycolysis, converting pyruvate into lactate. This process provides

efficient ATP for rapid tumor cell proliferation and supplies an

abundant lactate pool for lactate modification (65,66).

Previous study has reported that the PANoptosis process is mediated

by glycolysis during radiotherapy for esophageal cancer (12). Simultaneously, lactylation

modification induced by lactic acid accumulation regulates the

PANoptosis process through multiple signaling cascades, including

the Arg1/Mic10/voltage dependent anion channel 1 axis, the cold

inducible RNA binding/toll like receptor 4/ZBP1/tripartite motif

containing 32/RIPK3 axis and the proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase

14/pyruvate kinase M1/2/PINK1 axis (67–69).

Notably, lactate efflux via monocarboxylate transporters acidifies

the tumor microenvironment (TME), triggering damage-associated

molecular patterns (DAMPs) that induce stress signals leading to

inflammatory cell death in adjacent immune cells and cancer cells

(70). Furthermore, lactylation

activates downstream inflammatory cascades (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and

IL-12) by regulating S100 and high mobility group box 1 in DAMPs

(71,72). Notably, DAMP is one of the pathways

that trigger PANoptosis (7–11). The present study revealed that the

expression of TFRC and LDHA was positively associated during the

PANoptosis process in TC, and TFRC knockdown inhibited LDHA

expression in K1 cells. Therefore, we hypothesize that the

interaction between TFRC and LDHA may accelerate glycolysis and

lactate production. Further, accumulated lactic acid serves as a

substrate to induce lactylation of DAMP-associated proteins,

thereby regulating pro-inflammatory gene expression. Meanwhile,

lactic acid triggers inflammatory death through stress signals in

an acidic TME. These pathways together activate the PANoptosome

complex, ultimately synergistically triggering PANoptosis.

Therefore, the TFRC-LDHA-lactylation pathway may provide a novel

mechanism linking tumor glycolysis to PANoptosis. Collectively,

these findings suggest the occurrence of PANoptosis in TC may be an

outcome of TFRC interactions with these DE-mRNAs.

Although the present study proposes a potential

mechanism by which TFRC regulates PANoptosis in TC, the precise

mode of action remains unclear and requires further validation. In

particular, it is not yet known at which molecular level (protein,

RNA or DNA) and through what mechanisms TFRC interacts with the

identified DE-mRNAs. These issues warrant investigation using

approaches such as chromatin immunoprecipitation, pull down,

co-immunoprecipitation and RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation.

Moreover, the potential interactions of TFRC with the PANoptosis

sensors, ZBP1 and AIM2, also require verification. Finally, the

absence of in vivo experiments in the present study limits

direct evidence for TFRC-mediated regulation of PANoptosis in TC.

The findings suggest a potential association between TFRC and LDHA

expression, which may indirectly implicate glycolytic and

lactylation pathways in PANoptosis regulation. However, direct

experimental validation of LDHA function and lactate metabolism

remains to be investigated in future studies. Subsequently,

experiments such as LDHA knockdown/overexpression, lactate

measurement and histone lactylation detection need be performed to

further verify whether this pathway is indeed involved in

TFRC-mediated PANoptosis.

In conclusion, the present study provides the first

evidence, to the best of our knowledge, that TFRC contributes to

PANoptosis process in TC and delineates a potential regulatory

pathway using mRNA-seq. The findings not only advance the

understanding of PANoptosis in TC but also hold promise for

informing future therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway. To

exploit TFRC for TC treatment, several strategies could be

considered to increase its expression or activity in tumor cells.

Small molecule agonists or transcriptional activators that enhance

TFRC expression could be developed. Additionally,

nanoparticle-based delivery systems could be designed to deliver

TFRC-expressing plasmids or mRNA directly into tumor cells, thereby

restoring TFRC function and inducing PANoptosis. Future studies

should focus on validating these strategies in preclinical models

and ultimately in clinical trials to translate TFRC-based

PANoptosis induction into a viable therapeutic option for patients

with TC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Yunnan Provincial Health

Commission ‘Medical Leading Talents’ Training Program (grant no.

L-2018015) and Yunnan Province ‘Ten Thousand People Plan’ Special

Medical Talents (grant no. 2019-35).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE280138

(Secure Token: ctgxycgmjrazxob) or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE280138.

All other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SM and ZM conceived and designed the experiments;

SM, JS, HL, HY, YH and SY performed the experiments; SM and JS

analyzed and interpreted the data; HL, HY, YH and SY sourced the

reagents, materials and analysis tools; SM wrote original draft;

and ZM, JS, HL, HY, YH and SY reviewed and edited the manuscript

draft. SM, ZM, JS, HL, HY, YH and SY checked and confirmed the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chen DW, Lang BHH, McLeod DSA, Newbold K

and Haymart MR: Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 401:1531–1544. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig

AB, Fleshman JM and Matrisian LM: Projecting cancer incidence and

deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and

pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 74:2913–2921.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang L, Feng Q, Wang J, Tan Z, Li Q and

Ge M: Molecular basis and targeted therapy in thyroid cancer:

Progress and opportunities. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1878:1889282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Laha D, Nilubol N and Boufraqech M: New

therapies for advanced thyroid cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

11:822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shen H, Zhu R, Liu Y, Hong Y, Ge J, Xuan

J, Niu W, Yu X, Qin JJ and Li Q: Radioiodine-refractory

differentiated thyroid cancer: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic

strategies for radioiodine resistance. Drug Resist Updat.

72:1010132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pandian N and Kanneganti TD: PANoptosis: A

unique innate immune inflammatory cell death modality. J Immunol.

209:1625–1633. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Samir P, Malireddi RKS and Kanneganti TD:

The PANoptosome: A deadly protein complex driving pyroptosis,

apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis). Front Cell Infect

Microbiol. 10:2382020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Karki R and Kanneganti TD: PANoptosome

signaling and therapeutic implications in infection: Central role

for ZBP1 to activate the inflammasome and PANoptosis. Curr Opin

Immunol. 83:1023482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nozaki K, Li L and Miao EA: Innate sensors

trigger regulated cell death to combat intracellular infection.

Annu Rev Immunol. 40:469–498. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lee S, Karki R, Wang Y, Nguyen LN,

Kalathur RC and Kanneganti TD: AIM2 forms a complex with pyrin and

ZBP1 to drive PANoptosis and host defence. Nature. 597:415–419.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu LX, Heng JH, Deng DX, Zhao H, Zheng

ZY, Liao LD, Lin W, Xu XE, Li EM and Xu LY: Sulconazole induces

PANoptosis by triggering oxidative stress and inhibiting glycolysis

to increase radiosensitivity in esophageal cancer. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 22:1005512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Karki R, Sundaram B, Sharma BR, Lee S,

Malireddi RKS, Nguyen LN, Christgen S, Zheng M, Wang Y, Samir P, et

al: ADAR1 restricts ZBP1-mediated immune response and PANoptosis to

promote tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 37:1098582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ren L, Yang Y, Li W, Zheng X, Liu J, Li S,

Yang H, Zhang Y, Ge B, Zhang S, et al: CDK1 serves as a therapeutic

target of adrenocortical carcinoma via regulating

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, G2/M phase transition, and

PANoptosis. J Transl Med. 20:4442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cai Y, Chen X, Lu T, Fang X, Ding M, Yu Z,

Hu S, Liu J, Zhou X and Wang X: Activation of STING by SAMHD1

deficiency promotes PANoptosis and enhances efficacy of PD-L1

blockade in diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Biol Sci.

19:4627–4643. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Karbakhsh Ravari F, Ghasemi Gorji M and

Rafiei A: From iron-driven cell death to clot formation: The

emerging role of ferroptosis in thrombogenesis. Biomed

Pharmacother. 189:1183282025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shi J, Wu P, Sheng L, Sun W and Zhang H:

Ferroptosis-related gene signature predicts the prognosis of

papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 21:6692021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yang D, Wang J, Li C, Shi L and Zhang M:

Ferroptosis-related gene model to predict overall survival of

papillary thyroid carcinoma. Am J Otolaryngol. 42:1031632021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang Y, Du J, Li D, He W, Liu Z, Liu L,

Yang X, Cheng X, Chen R and Yang Y: LASS2 suppresses metastasis in

multiple cancers by regulating the ferroptosis signalling pathway

through interaction with TFRC. Cancer Cell Int. 24:872024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhou X, Nie M, Xin X, Hua T, Zhang J, Shi

R, Dong K, Shu W, Yan B and Wang H: RAB17 promotes endometrial

cancer progression by inhibiting TFRC-dependent ferroptosis. Cell

Death Dis. 15:6552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang X, Zhou Y, Ning L, Chen J, Chen H and

Li X: Knockdown of ANXA10 induces ferroptosis by inhibiting

autophagy-mediated TFRC degradation in colorectal cancer. Cell

Death Dis. 14:5882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Guo S, Chen Y, Xue X, Yang Y, Wang Y, Qiu

S, Cui J, Zhang X, Ma L, Qiao Y and Wang J: TRIB2 desensitizes

ferroptosis via βTrCP-mediated TFRC ubiquitiantion in liver cancer

cells. Cell Death Discov. 7:1962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lin Z, Zhong C, Shi M, Long Q, Jing L, Yu

Y, Chou J, Chen M, Lan M and Long F: Circular RNA TFRC/SCD1 mRNA

interaction regulates ferroptosis and metastasis in gastric cancer.

Cell Death Dis. 16:4362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang WT, Duan ZW, Xing TY, Hua W, Du KX,

Shang CY, Wu YF, Wang L, Li JY, Gao R, et al: PTPN2 inhibition

disrupts mitochondrial renewal and blocks TFRC-Mediated mitophagy

to exert Anti-Tumor activities in ALK-Positive anaplastic large

cell lymphoma. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e142822025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang K, Shi X, Lin H, Xu T and Xu S:

Selenium deficiency exacerbates ROS/ER stress mediated pyroptosis

and ferroptosis induced by bisphenol A in chickens thymus. J

Environ Sci (China). 148:13–26. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang X, Xu W, Wang Z, Liu J, Gong H and

Zou W: Cross-talk between cuproptosis and ferroptosis to identify

immune landscape in cervical cancer for mRNA vaccines development.

Eur J Med Res. 29:6022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, Poisson

LM, Lazar AJ, Cherniack AD, Kovatich AJ, Benz CC, Levine DA, Lee

AV, et al: An Integrated TCGA Pan-cancer clinical data resource to

drive High-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell.

173:400–416.e11. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2:1001412021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A,

Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork

P, et al: STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with

increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide

experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:D607–D613. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Otasek D, Morris JH, Bouças J, Pico AR and

Demchak B: Cytoscape Automation: Empowering workflow-based network

analysis. Genome Biol. 20:1852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bader GD and Hogue CW: An automated method

for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction

networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 4:22003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin H and Zelterman DJT: Modeling Survival

Data: Extending the Cox Model. Technometrics. 44:85–86. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang L, Wang S and Li W: RSeQC: Quality

control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 28:2184–2185. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y and Gu J: fastp: An

ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics.

34:i884–i890. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim D, Langmead B and Salzberg SL: HISAT:

A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods.

12:357–360. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Anders S, Pyl PT and Huber W: HTSeq-a

Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data.

Bioinformatics. 31:166–169. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ginestet C: ggplot2: Elegant graphics for

data analysis. J Royal Stat Soc Series A Statistics Soc.

174:245–246. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wan Z, Wen M, Zheng C, Sun Y, Zhou Y, Tian

Y, Xin S, Wang X, Ji X, Yang J, et al: Centromere protein F in

tumor biology: Cancer's Achilles heel. Cancer Med. 14:e709492025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li RQ, Yang Y, Qiao L, Yang L, Shen DD and

Zhao XJ: KIF2C: An important factor involved in signaling pathways,

immune infiltration, and DNA damage repair in tumorigenesis. Biomed

Pharmacother. 171:1161732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Burns M and Borgal L: Asp/ASPM

phospho-regulation throughout the cell cycle. Genome. 68:1–10.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Marima R, Hull R, Penny C and Dlamini Z:

Mitotic syndicates Aurora Kinase B (AURKB) and mitotic arrest

deficient 2 like 2 (MAD2L2) in cohorts of DNA damage response (DDR)

and tumorigenesis. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 787:1083762021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tokuzumi A, Fukushima S, Miyashita A,

Nakahara S, Kubo Y, Yamashita J, Harada M, Nakamura K, Kajihara I,

Jinnin M and Ihn H: Cell division cycle-associated protein 1 as a

new melanoma-associated antigen. J Dermatol. 43:1399–1405. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Malireddi RKS, Kesavardhana S and

Kanneganti TD: ZBP1 and TAK1: Master regulators of NLRP3

Inflammasome/Pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PAN-optosis).

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 9:4062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lin JF, Hu PS, Wang YY, Tan YT, Yu K, Liao

K, Wu QN, Li T, Meng Q, Lin JZ, et al: Phosphorylated NFS1 weakens

oxaliplatin-based chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer by

preventing PANoptosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:542022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lin C, Lin P, Yao H, Liu S, Lin X, He R,

Teng Z, Zuo X, Li Y, Ye J and Zhu G: Modulation of YBX1-mediated

PANoptosis inhibition by PPM1B and USP10 confers chemoresistance to

oxaliplatin in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 587:2167122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tan YT, Li T, Wang RB, Liu ZK, Ma MY,

Huang RZ, Mo HY, Luo SY, Lin JF, Xu RH and Ju HQ: WTAP weakens

oxaliplatin chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer by preventing

PANoptosis. Cancer Lett. 604:2172542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Qi H, Li X, Ma J, Sun J, Liu Y, Wang X,

Fan K, Shu C and Wang C: Fullerenols hijack lysosomes to disrupt

inter-organellar crosstalk and block autophagy pre-activated by

mTOR inhibitors for cancer cell PANoptosis. Sci Bull (Beijing).

70:1275–1294. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Luo Y, Linghu M, Luo X, Li D, Wang J, Peng

S and Ma Y: Remodeling tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment

through dual activation of immunogenic panoptosis and ferroptosis

by H2S-amplified nanoformulation to enhance cancer immunotherapy.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 15:1242–1254. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang J, Chen Y, Xu Y, Zhang J, Yang S,

Zhou Y, Lei J, Ren R, Chen Y, Zhao H, et al: DNASE1L3-mediated

PANoptosis enhances the efficacy of combination therapy for

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 14:6798–6817.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang S, Song A, Xie J, Wang YY, Wang WD,

Zhang MJ, Wu ZZ, Yang QC, Li H, Zhang J and Sun ZJ: Fn-OMV

potentiates ZBP1-mediated PANoptosis triggered by oncolytic HSV-1

to fuel antitumor immunity. Nat Commun. 15:36692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Xing J, Ma X, Yu Y, Xiao Y, Chen L, Yuan

W, Wang Y, Liu K, Guo Z, Tang H, et al: A Cardiac-targeting and

anchoring bimetallic cluster nanozyme alleviates

Chemotherapy-induced cardiac ferroptosis and PANoptosis. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24055972025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang J, Chen S, Wei S, Cheng S, Shi R,

Zhao R, Zhang W, Zhang Q, Hua T, Feng D, et al: CircRAPGEF5

interacts with RBFOX2 to confer ferroptosis resistance by

modulating alternative splicing of TFRC in endometrial cancer.

Redox Biol. 57:1024932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wei XB, Jiang WQ, Zeng JH, Huang LQ, Ding

HG, Jing YW, Han YL, Li YC and Chen SL: Exosome-derived lncRNA

NEAT1 exacerbates Sepsis-associated encephalopathy by promoting

ferroptosis through Regulating miR-9-5p/TFRC and GOT1 axis. Mol

Neurobiol. 59:1954–1969. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Feng G, Arima Y, Midorikawa K, Kobayashi

H, Oikawa S, Zhao W, Zhang Z, Takeuchi K and Murata M: Knockdown of

TFRC suppressed the progression of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by

downregulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Cancer Cell Int.

23:1852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mu Y, Sun J, Li Z, Zhang W, Liu Z, Li C,

Peng C, Cui G, Shao H and Du Z: Activation of pyroptosis and

ferroptosis is involved in the hepatotoxicity induced by

polystyrene microplastics in mice. Chemosphere. 291:1329442022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang Y, Hu M, Jia W, Liu G, Zhang J, Wang

B, Li J, Cui P, Li X, Lager S, et al: Hyperandrogenism and insulin

resistance modulate gravid uterine and placental ferroptosis in

PCOS-like rats. J Endocrinol. 246:247–263. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Urbańska K and Orzechowski A:

Unappreciated role of LDHA and LDHB to control apoptosis and

autophagy in tumor cells. Int J Mol Sci. 20:20852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Shi X, Chen Y, Liu Q, Mei X, Liu J, Tang

Y, Luo R, Sun D, Ma Y, Wu W, et al: LDLR dysfunction induces LDL

accumulation and promotes pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Transl Med.

12:e7112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yao X and Li C: Lactate dehydrogenase A

mediated histone lactylation induced the pyroptosis through

targeting HMGB1. Metab Brain Dis. 38:1543–1553. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lin S, Tan L, Luo D, Peng X, Zhu Y and Li

H: Linc01278 inhibits the development of papillary thyroid

carcinoma by regulating miR-376c-3p/DNM3 axis. Cancer Manag Res.

11:8557–8569. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Rong Y, Gao J, Kuang T, Chen J, Li JA,

Huang Y, Xin H, Fang Y, Han X, Sun LQ, et al: DIAPH3 promotes

pancreatic cancer progression by activating selenoprotein

TrxR1-mediated antioxidant effects. J Cell Mol Med. 25:2163–2175.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Han F, Cheng C, Xu Q, Chen J, Yang Z and

Liu J: DEPDC1B promotes colorectal cancer via facilitating cell

proliferation and migration while inhibiting apoptosis. Cell Cycle.

22:131–143. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Li C, Liu Z, Kong D, Li Z and Li L:

Lactylation: A novel driver of drug resistance in the tumor

microenvironment. Cancer Drug Resist. 8:392025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Yang Y, Wu Y, Chen H, Xu Z, Lu R, Zhang S,

Zhan R, Xi Q and Jin Y: Research progress on the interaction

between glucose metabolic reprogramming and lactylation in tumors.

Front Immunol. 16:15951622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

She H, Zheng J, Zhao G, Du Y, Tan L, Chen

ZS, Wu Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Sun Y, et al: Arginase 1 drives

mitochondrial cristae remodeling and PANoptosis in

ischemia/hypoxia-induced vascular dysfunction. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 10:1672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gong T, Wang QD, Loughran PA, Li YH, Scott

MJ, Billiar TR, Liu YT and Fan J: Mechanism of lactic

acidemia-promoted pulmonary endothelial cells death in sepsis: Role

for CIRP-ZBP1-PANoptosis pathway. Mil Med Res. 11:712024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Xu L, Ye Y, Gu W, Xu X, Chen N, Zhang L,

Cai W, Hu J, Wang T, Chao H, et al: Histone lactylation stimulated

upregulation of PSMD14 alleviates neuron PANoptosis through

deubiquitinating PKM2 to activate PINK1-mediated mitophagy after

traumatic brain injury. Autophagy. 21:1473–1491. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Peng X, He Z, Yuan D, Liu Z and Rong P:

Lactic acid: The culprit behind the immunosuppressive

microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta

Rev Cancer. 1879:1891642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Mi K, Chen Z, He J, Jiang C, Xia Y and

Peng J: P300-Mediated ARRB1 lactylation promotes mitochondrial

dysfunction and neuronal apoptosis in subarachnoid hemorrhage via

upregulating S100A9. Neurochem Res. 50:1742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Du S, Zhang X, Jia Y, Peng P, Kong Q,

Jiang S, Li Y, Li C, Ding Z and Liu L: Hepatocyte HSPA12A inhibits

macrophage chemotaxis and activation to attenuate liver

ischemia/reperfusion injury via suppressing glycolysis-mediated

HMGB1 lactylation and secretion of hepatocytes. Theranostics.

13:3856–3871. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|