Introduction

Lung cancer persists as the leading cause of

cancer-related mortality in men and ranks second in women worldwide

(1). Notably, ~70% of lung cancer

cases are diagnosed at advanced stages with metastatic

dissemination (2). The adrenal

glands constitute a frequent metastatic site in this population,

with reported incidence rates ranging from 18 to 42% across

studies. Notably, 2–4% of these patients present with isolated

adrenal metastases that may be amenable to curative interventions

(3–5). Emerging evidence has demonstrated that

aggressive local therapies, including surgical resection and

stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, can markedly improve survival

outcomes in patients with solitary adrenal metastases (6,7). These

findings underscore the critical need for accurate restaging of

solitary adrenal masses in lung cancer management.

Nevertheless, differentiating metastatic lesions

from benign adrenal lesions in patients with lung cancer remains

clinically challenging (8),

particularly for small lesions [long diameter (LD) ≤3 cm] with

hyperattenuating features [unenhanced computed tomography (CT)

values ≥10 HU] (9–11). Although conventional imaging

modalities offer diagnostic parameters such as CT attenuation

values, delayed contrast-enhanced CT patterns and magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) chemical-shift characteristics (12–14),

their clinical application faces three major limitations. First,

lesion-specific diagnostic thresholds may lack generalizability due

to heterogeneous tumor biology. Second, concurrent primary lung

malignancies can complicate radiological interpretation. Third,

practical challenges exist, including increased radiation exposure

from multiphase CT protocols, time-consuming MRI acquisitions that

disrupt clinical workflows and contraindications that compromise

image quality (such as motion artifacts or metallic implants)

(15,16).

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron

emission tomography (PET)/CT is an imaging modality that provides

both anatomical and metabolic information by assessing glucose

uptake. This technique has emerged as a reliable non-invasive tool

for evaluating adrenal masses (17,18).

However, its diagnostic accuracy is limited by two key factors: i)

Some benign adrenal lesions (for example, functional adenomas)

exhibit increased FDG uptake, potentially leading to

Tumor-Node-Metastasis stage overestimation (19,20);

and ii) certain adrenal metastases in patients with lung cancer may

remain undetected due to low FDG avidity (21). Additionally, previous studies have

primarily focused on individual metabolic parameters for

differentiating adrenal tumors (22,23),

while comprehensive PET/CT-based analyses of solitary small

hyperattenuating adrenal lesions in patients with lung cancer

remain scarce.

Support vector machine (SVM), a supervised machine

learning algorithm, is particularly effective for classification

tasks with limited sample sizes. SVM constructs an optimal decision

boundary by maximizing the margin between two classes in the

training dataset, thereby improving model generalizability

(24). SVM has shown promise in

classifying solitary pulmonary nodules and lymph nodes (25,26);

however, its application to solitary small hyperattenuating adrenal

lesions in lung cancer remains unexplored.

To address these gaps in the knowledge, the present

study aimed to develop an interpretable SVM-based classification

model to enhance the diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG

PET/CT in distinguishing between metastatic and benign solitary

small hyperattenuating adrenal lesions in patients with lung

cancer.

Patients and methods

Patients

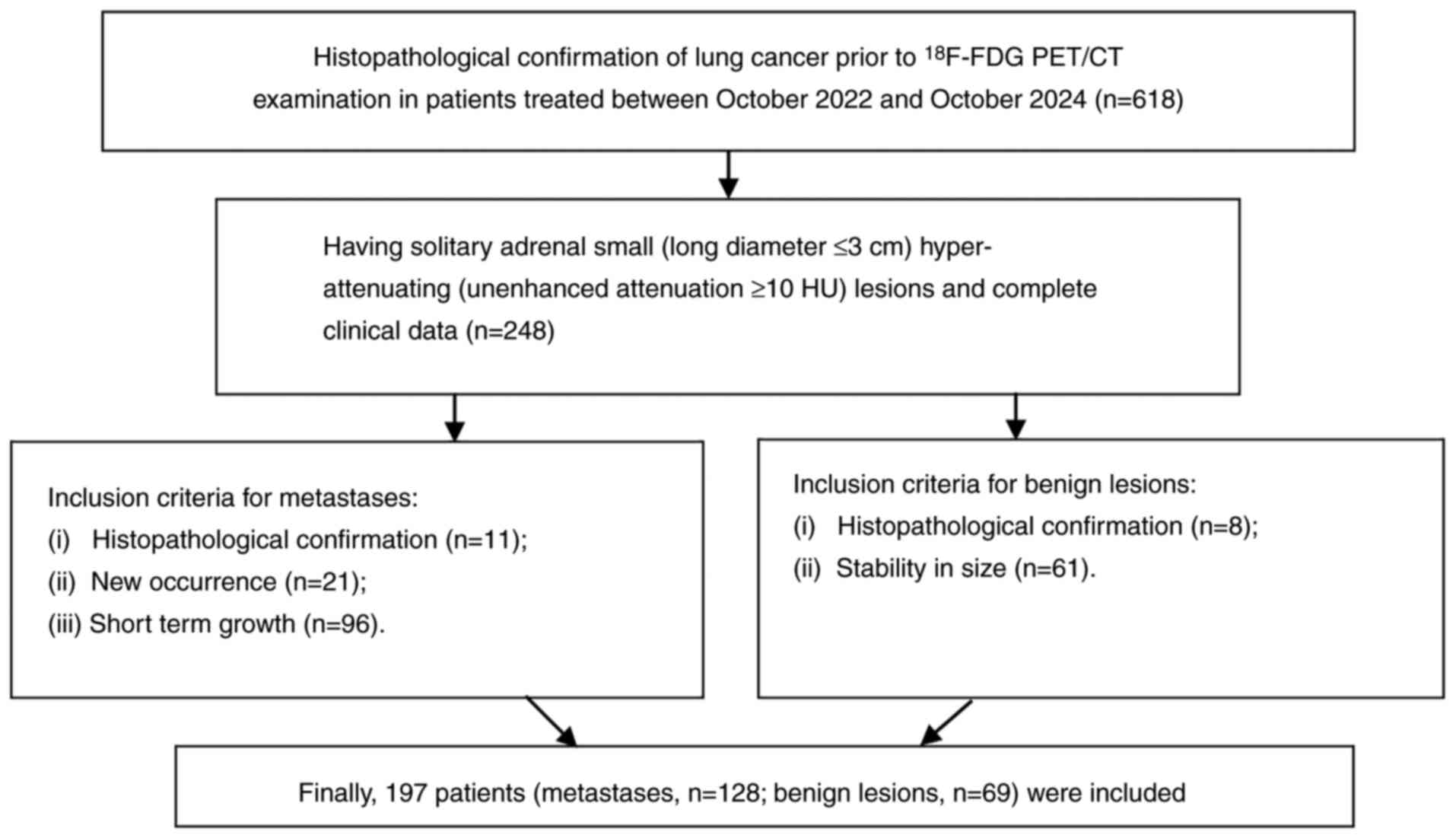

Patients treated in Tangshan People's Hospital

(Tangshan, China) between October 2022 and October 2024 were

retrospectively included in the present study if they met the

following criteria: i) Histopathologically confirmed lung cancer

prior to 18F-FDG PET/CT examination; and ii) the

presence of a solitary small (LD ≤3 cm) hyperattenuating

(unenhanced CT value ≥10 HU) adrenal lesion. The current study was

approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tangshan People's

Hospital (approval no. RMYY-LLKS-2023202). The requirement for

written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature

of the study. The diagnostic criteria for adrenal metastases were

as follows: i) Histopathological confirmation; or ii) interval

development of an adrenal mass on follow-up CT (compared with a

prior scan showing normal adrenal glands); or iii) short-term

interval growth [defined as a ≥20% increase in total tumor burden

within 6 months (27)]. The

diagnostic criteria for benign lesions were as follows: i)

Histopathological confirmation; or ii) stability in size (no

change) during ≥6 months of follow-up. A total of 197 patients (128

with metastases and 69 with benign lesions) were included to

develop and validate the models (Fig.

1).

18F-FDG PET/CT procedure. In the

present study, PET/CT imaging was performed using a Discovery MI

scanner (GE Healthcare). All patients received an intravenous

injection of 18F-FDG (4.2 MBq/kg), and imaging was

conducted ~60 min post-injection. Prior to the examination,

patients were required to fast for ≥6 h and to maintain blood

glucose levels at <11 mmol/l. Initially, unenhanced CT images

were acquired with the following parameters: 120 kV, 80 mAsec and a

slice thickness of 5 mm, covering the region from the skull vertex

to the mid-femur during tidal breathing. Subsequently, dedicated

full-ring PET images were obtained from the mid-thigh to the vertex

of the head during shallow breathing. Image reconstruction was

performed using an ordered-subset expectation maximization

algorithm with CT-based attenuation correction.

18F-FDG PET/CT image analysis. Two

nuclear medicine radiologists with 4 and 6 years of PET/CT

diagnostic experience, respectively, independently reviewed the

PET/CT images. Disagreements between the two radiologists were

settled by consensus. On the CT component, the following adrenal

nodule characteristics were assessed: i) Short diameter (SD) and

LD; ii) location (left or right); iii) homogeneity (homogeneous or

heterogeneous); iv) unenhanced CT value, measured by manually

placing a region of interest (ROI) covering two-thirds of the

largest transverse lesion section while avoiding adjacent fat

tissue. In addition, ROI measurements excluded areas with

calcification, hemorrhagic components, cystic degeneration or

necrosis. On the PET component, the maximum standardized uptake

value (SUVmax) was measured by drawing a circular-oval

ROI encompassing the entire adrenal nodule and primary lung cancer,

carefully avoiding adjacent FDG-avid structures. For reference, an

additional ROI was placed in the right posterior superior liver

segment. The following metabolic ratios were calculated:

Adrenal-to-liver SUVmax ratio

(SURadrenal/liver) and lung-to-liver SUVmax

ratio (SURlung/liver). Therefore, six key features were

analyzed for each case: i) Morphological characteristics: Size (SD

and LD), location, homogeneity and unenhanced CT value; and ii)

metabolic parameters: Adrenal nodules [SUVmax(adrenal

and SURadrenal/liver] and lung cancer

(SUVmax(lung) and SURlung/liver).

Statistical analysis and model

development

In the present study, the models were constructed

using an SVM with a linear kernel function and a regularization

parameter (C) set to 1. To enhance model interpretability, a single

feature from either the metabolic or size features of adrenal

lesions or the metabolic features of lung cancer was iteratively

selected, combining it with other feature types to build each

model. Using stratified random sampling, the study cohort was

divided into training (n=148; 96 metastases and 52 benign lesions)

and validation (n=49; 32 metastases and 17 benign lesions) subsets

maintaining a 3:1 allocation ratio. To mitigate sampling bias, this

sampling process was repeated 1,000 times. During this process, the

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values

and accuracies of the models in the validation subsets were used to

evaluate their performance. To assess whether the classification

accuracy exceeded chance level, a null distribution of accuracies

was generated by randomly shuffling the metastatic status labels of

adrenal lesions during classifier training, thereby eliminating any

predictive information. The P-value was calculated by comparing the

actual classification accuracy (derived from correctly labeled

data) against the null distribution, defined as the proportion of

null accuracies equal to or greater than the observed accuracy

(28). Permutation tests were

conducted for the best-performing SVM model (namely the models with

the highest accuracy). To further evaluate whether SVM was the

optimal method for metastasis prediction, its performance was

compared with random forest and k-nearest neighbor (KNN)

classifiers. Each algorithm was run 1,000 times under identical

conditions to ensure comparability, and the distributions of

accuracy and AUC were analyzed. For the random forest model, five

decision trees were used, with a minimum tree depth of 1 and the

number of features per tree set to the square root of the total

feature count. For KNN, k was set at 5. To enhance clinical

applicability, the model was simplified by scoring features based

on their weights and the distribution of continuous variables. The

final risk score was computed as the sum of each feature's score

multiplied by its mean weight. All analyses were performed using

Python (version 3.12; Python Software Foundation). The AUC and

accuracy of different models were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis

test with Dunn's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical characteristics and PET/CT

features

The clinical characteristics of patients in both

cohorts are summarized in Table I.

The retrospective dataset comprised 197 patients (age range, 28–85

years; males, 126; females, 71), including 128 metastatic lesions

and 69 benign adrenal lesions. Among the lung cancer cases,

adenocarcinoma represented the predominant histological subtype

(134/197, 68.0%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (48/197,

24.4%). Other histological variants included adenosquamous

carcinoma (7/197, 3.6%), large cell carcinoma (4/197, 2.0%),

sarcomatoid carcinoma (3/197, 1.5%) and pleomorphic carcinoma

(1/197, 0.5%). Table II summarizes

six key PET/CT features for both cohorts, including size (SD and

LD), metabolism (SUVmax(adrenal) and

SURadrenal/liver), unenhanced CT value, location and

homogeneity of adrenal nodules, and metabolism of lung cancer

(SUVmax(lung) and SURlung/liver).

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of

patients. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of

patients.

|

Characteristics | Distribution |

|---|

| Sex, n |

|

|

Male | 126 |

|

Female | 71 |

| Age, years |

|

|

Range | 28-85 |

| Mean ±

standard deviation | 62.71±8.99 |

|

Median | 63 |

| Histological

subtype of lung cancer, n |

|

|

Adenocarcinoma | 134 |

|

Squamous cell carcinoma | 48 |

| Other

types | 15 |

|

Adenosquamous

carcinoma | 7 |

|

Large cell

carcinoma | 4 |

|

Sarcomatoid

carcinoma | 3 |

|

Pleomorphic

carcinoma | 1 |

| Group, n |

|

|

Metastases | 128 |

| Benign

lesions | 69 |

| Table II.Positron emission tomography/CT

features of patients. |

Table II.

Positron emission tomography/CT

features of patients.

| Features | Metastases

(n=128) | Benign lesions

(n=69) |

|---|

| Size of adrenal

lesions, cma |

|

|

| SD | 1.39±0.41 | 1.23±0.33 |

| LD | 1.81±0.51 | 1.52±0.48 |

| Metabolism of

adrenal lesionsa |

|

|

|

SUVmax(adrenal),

g/m | 5.60±2.24 | 3.03±0.91 |

|

SURadrenal/liver | 1.74±0.69 | 1.02±0.26 |

|

Unenhanced CT value of adrenal

lesionsa | 35.97±6.40 | 28.99±6.48 |

| Location of adrenal

lesions, n |

|

|

|

Left | 83 | 48 |

|

Right | 45 | 21 |

| Homogeneity of

adrenal lesions, n |

|

|

|

Homogeneous | 108 | 54 |

|

Heterogeneous | 20 | 15 |

| Metabolism of lung

cancera |

|

|

|

SUVmax(lung),

g/m | 10.50±4.33 | 6.55±2.92 |

|

SURlung/liver | 3.27±1.35 | 2.25±1.06 |

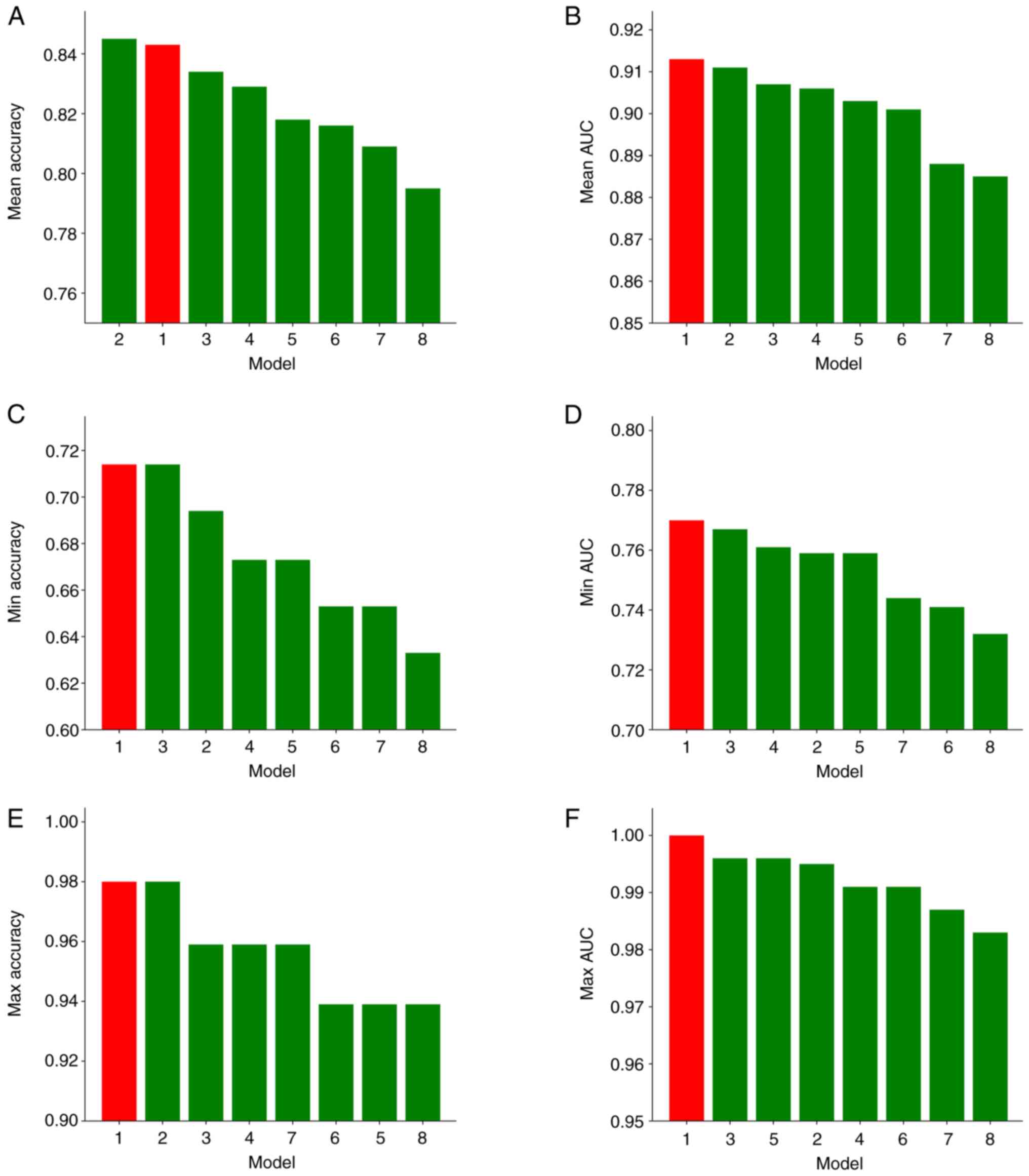

Comparison of different models

A total of eight distinct SVM models were developed

in the present study, with their respective feature compositions

detailed in Table III. For each

model, 1,000 iterations of sampling were performed to ensure robust

statistical evaluation. Model 1 emerged as the top-performing

model, demonstrating superior performance across multiple metrics,

including i) AUC: Maximum, 1.000; mean, 0.913; and minimum, 0.770;

and ii) accuracy: Maximum, 98.0% (95% CI, 93.9–100%); mean, 84.3%

(95% CI, 69.4–91.8%); and minimum, 71.4% (95% CI, 57.1–83.7%)

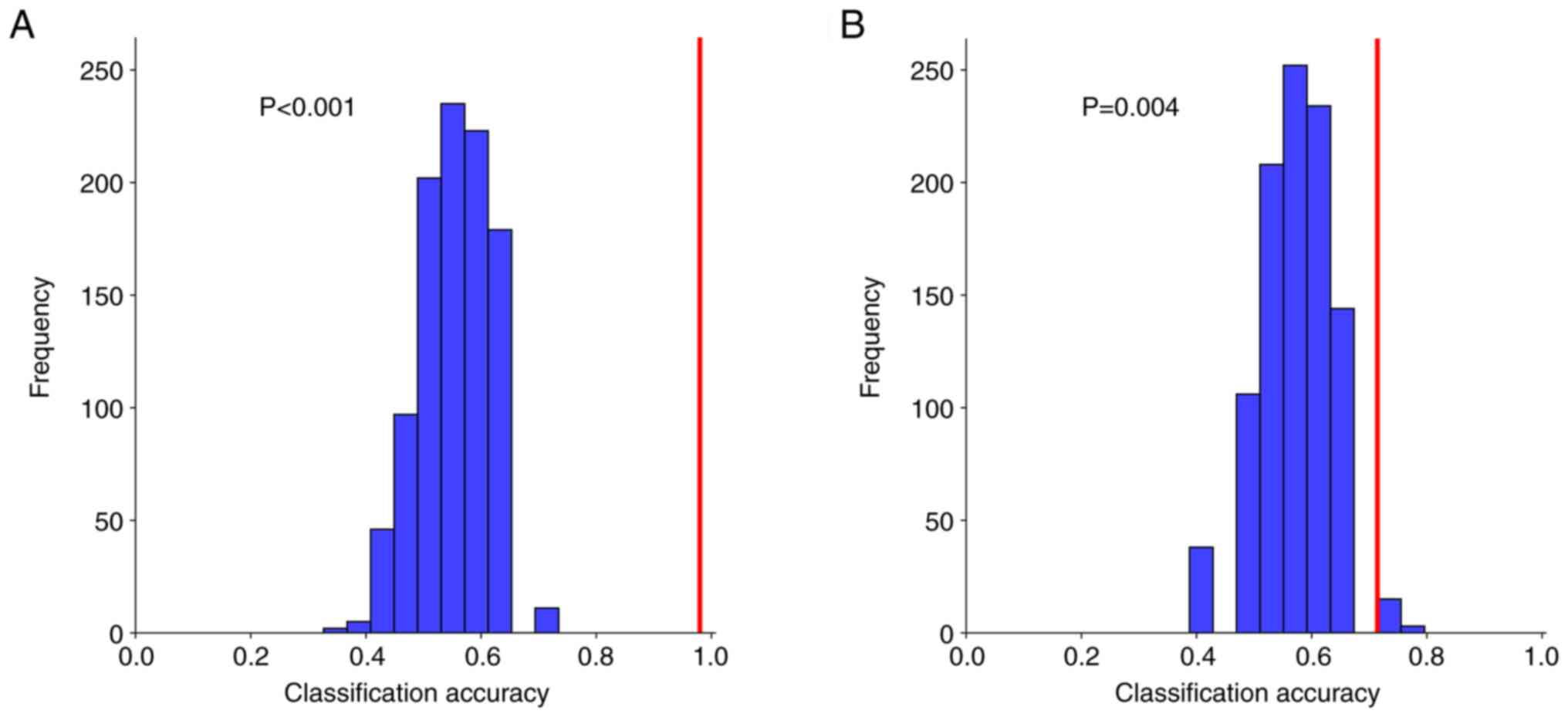

(Fig. 2). Permutation tests for

Model 1 yielded statistically significant results (P<0.001 for

the highest-accuracy iteration; P=0.004 for the lowest-accuracy

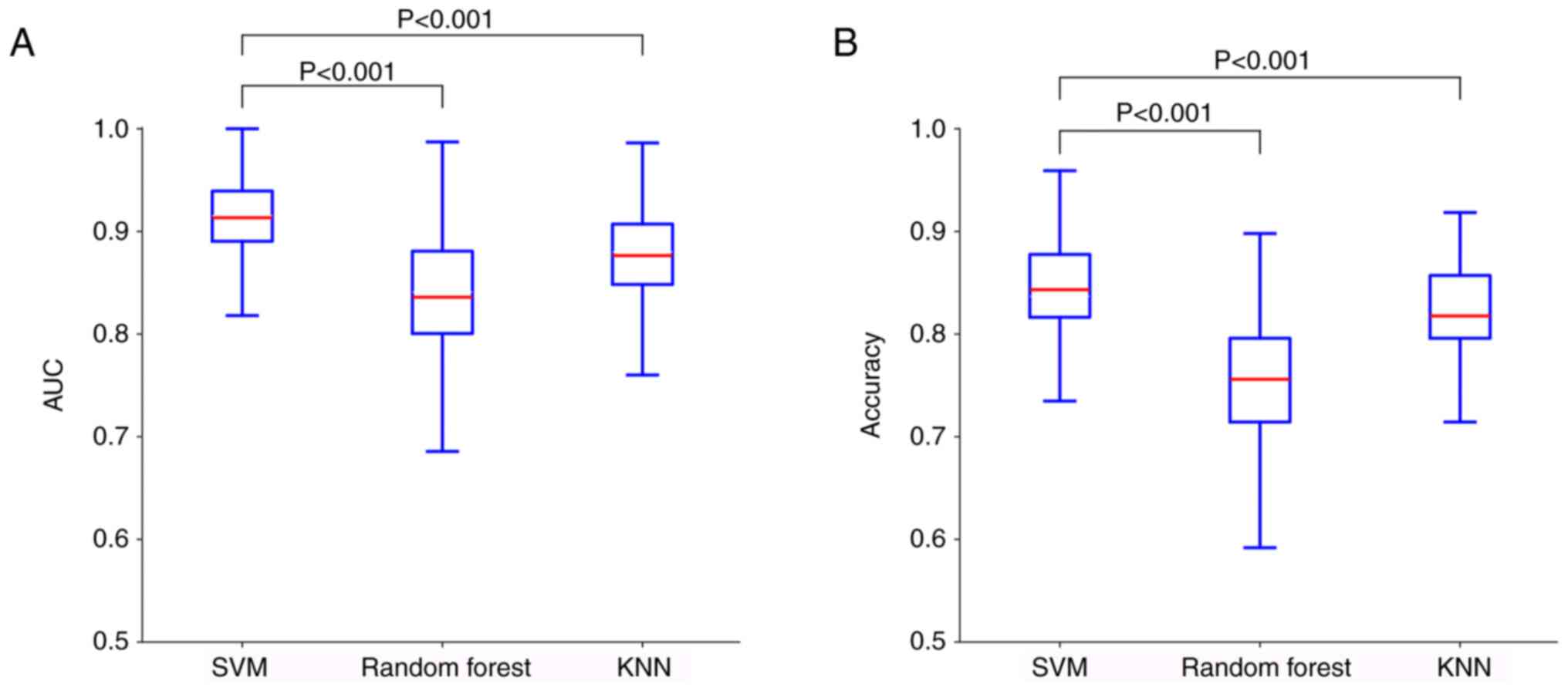

iteration) (Fig. 3). To validate

the predictive superiority of SVM, its performance was compared

against identically configured random forest and KNN models. SVM

significantly outperformed both alternatives in terms of accuracy

(both P<0.001) and AUC (both P<0.001) (Fig. 4).

| Table III.Combination of different types of

features. |

Table III.

Combination of different types of

features.

| Model number | Metabolism of

adrenal lesions | Size of adrenal

lesions | Metabolism of lung

cancers | Unenhanced CT value

of adrenal lesions | Location of adrenal

lesions | Homogeneity of

adrenal lesions |

|---|

| 1 |

SUVmax(adrenal) | LD |

SUVmax(lung) | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 2 | SUV

max(adrenal) | LD |

SURlung/liver | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 3 | SUV

max(adrenal) | SD | SUV

max(lung) | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 4 | SUV

max(adrenal) | SD |

SURlung/liver | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 5 |

SURadrenal/liver | LD | SUV

max(lung) | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 6 |

SURadrenal/liver | LD |

SURlung/liver | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 7 |

SURadrenal/liver | SD | SUV

max(lung) | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

| 8 |

SURadrenal/liver | SD |

SURlung/liver | Hounsfield

unit | Right/left | Yes/no |

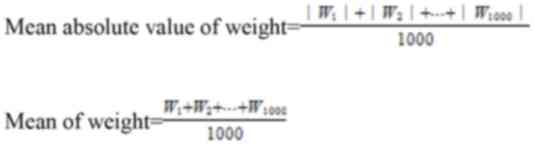

Feature weights of the best model

Table IV presents

the 18F-FDG PET/CT feature weights of Model 1. The mean

absolute value of weights and the mean of weight were calculated as

follows:

| Table IV.Weight of features for the best

model. |

Table IV.

Weight of features for the best

model.

|

Characteristics | Mean weight | Mean absolute value

of weight |

|---|

| Homogeneity of

adrenal lesions | −0.177±0.097 | 0.179±0.094 |

| Location of adrenal

lesions | −0.146±0.158 | 0.183±0.115 |

| Unenhanced CT value

of adrenal lesions | 0.702±0.114 | 0.702±0.114 |

| LD of adrenal

lesions | 0.443±0.112 | 0.443±0.112 |

|

SUVmax(adrenal) | 1.247±0.170 | 1.247±0.170 |

|

SUVmax(lung) | 0.709±0.137 | 0.709±0.137 |

The mean absolute weight reflects each feature's

relative importance in the model. A positive mean weight indicates

a positive association with metastases, whereas a negative value

suggests an inverse association. Key findings regarding feature

importance and association included: i) Homogeneity of adrenal

lesions had the lowest mean absolute value of weight; ii)

SUVmax(adrenal) had the highest mean absolute value of

weight; iii) homogeneity and location of adrenal lesions were

negatively correlated with metastases; and iv)

SUVmax(adrenal), SUVmax(lung), unenhanced CT

value and LD were positively correlated with metastases.

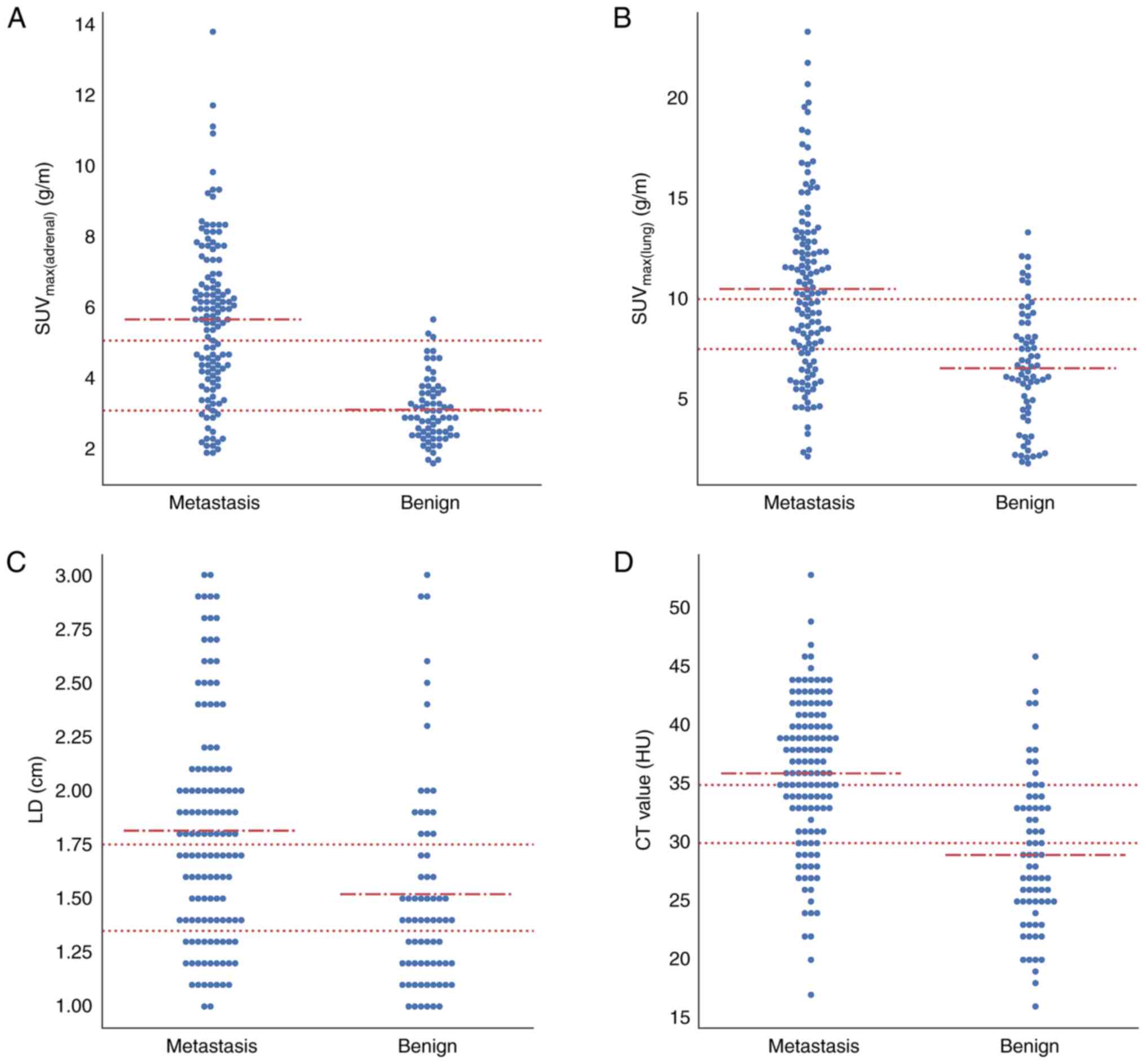

Adrenal metastasis scoring rule

Fig. 5 displays the

distributions of SUVmax(adrenal),

SUVmax(lung), LD and unenhanced CT value. To facilitate

subsequent model simplification, each continuous variable was

categorized using thresholds derived from the approximate mean

values of the metastatic and benign groups. The variables were

categorized as follows: SUVmax(adrenal) was separated

into <3, 3–5 and ≥5 g/m; SUVmax(lung) was separated

into <7.5, 7.5–10 and ≥10 g/m; LD was separated into <1.35,

1.35–1.75 and ≥1.75 cm; and unenhanced CT value was separated into

<30, 30–35 and ≥35 HU. The mean weights were used as feature

coefficients for scoring. Table V

presents the detailed scoring system based on these distributions

and coefficients, whereby each factor was assigned a score

according to predetermined thresholds, and the final risk score was

calculated as the sum of each factor's score multiplied by its mean

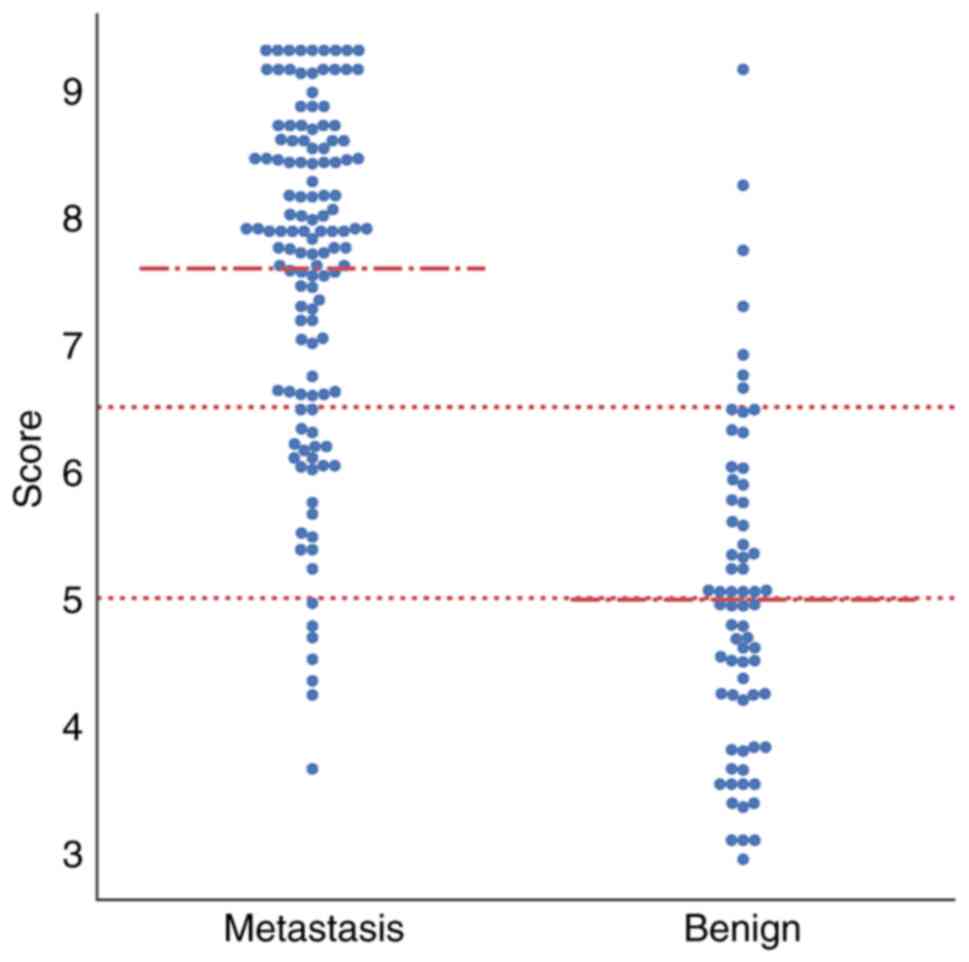

weighting coefficient. Fig. 6

illustrates the final score distribution. The final scores were as

follows: 56.5% (39/69) of adrenal benign lesions scored <5,

whereas only 7.03% (9/128) of adrenal metastases scored <5.

Furthermore, only 5.80% (4/69) of the final scores of benign

lesions were >6.5, but 68.8% (88/128) of those for metastases

were >6.5. Finally, the following diagnostic criteria were

established: Adrenal nodules with scores <5 were benign; those

with scores >6.5 were metastatic; and those with scores 5–6.5

were suspicious for metastasis.

| Table V.Final scoring rules for predicting

adrenal metastases. |

Table V.

Final scoring rules for predicting

adrenal metastases.

|

| SUVmax

(adrenal), g/m | SUVmax

(lung), g/m | LD, cm | Unenhanced CT

value, HU | Location | Homogeneity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factor | <3 | 3-5 | ≥5 | <7.5 | 7.5–10 | ≥10 | <1.35 | 1.35–1.75 | ≥1.75 | <30 | 30-35 | ≥35 | L | R | Yes | No |

|---|

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Coefficient | 1.25 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.70 | −0.15 | −0.18 |

Discussion

The adrenal gland is a frequent site of metastasis,

particularly in patients with lung cancer (29). However, differentiating metastatic

from benign adrenal lesions in these patients remains clinically

challenging due to the overlapping prevalence of neoplastic and

non-neoplastic adrenal masses (30,31).

Compared with conventional CT or MRI, 18F-FDG PET/CT

offers distinct advantages by providing both functional metabolic

data and anatomical information. This synergistic capability has

verified the use of PET/CT as an invaluable tool in the evaluation

of primary lung cancer and its metastatic spread, particularly in

characterizing rare soft-tissue masses (32) and indeterminate solitary

hyperattenuating adrenal lesions (33). In the current study, an SVM model

was developed using 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters that

demonstrated superior performance to both KNN and random forest

algorithms, achieving high predictive accuracy (AUC=0.913) for

identifying adrenal metastases. Among the predictive features,

SUVmax(adrenal) emerged as the most significant

contributor, with a mean absolute weight of 1.25 in the model. To

enhance clinical applicability, the model was subsequently

simplified into a practical scoring system. This streamlined

approach maintains diagnostic accuracy while facilitating

implementation in routine clinical practice.

Recent studies have demonstrated the promising

diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting

adrenal metastases in patients with lung cancer (23,34,35).

Evans et al (34) reported

that SUVmax exhibited marked diagnostic efficacy, with a

mean sensitivity of 91%, specificity of 81% and accuracy of 83% for

identifying adrenal metastases. Similarly, Orzechowski et al

(23) revealed that SUVs provided

reliable assessment of adrenal metastases, achieving an AUC of

0.83. Notably, Kim et al (35) demonstrated even higher diagnostic

accuracy using SURadrenal/liver (AUC, 0.933;

sensitivity, 87%; specificity, 100%) in patients with non-small

cell lung cancer. However, the small sample size of this previous

study (n=24 patients with suspicious adrenal masses) may limit the

generalizability of its findings. A critical limitation common to

these studies is their reliance on single metabolic parameters for

metastasis prediction. As established in the literature,

single-parameter approaches have inherent constraints: i) They

often demonstrate suboptimal diagnostic performance, and ii) they

cannot comprehensively characterize the multifaceted nature of

adrenal metastases. To enhance diagnostic accuracy, recent studies

have explored multi-parameter approaches for predicting adrenal

metastases (9,36,37).

Brady et al (9) demonstrated

that combining SUVmax >3.1 with mean attenuation

>10 HU achieved excellent diagnostic performance (sensitivity,

97.3%; specificity, 86.2%; accuracy, 90.5%). Similarly, Cho et

al (36) reported that an

adrenal-to-liver SUVmax ratio >1.3 combined with HU

>18 yielded a sensitivity of 97.7%, a specificity of 81.2% and

an accuracy of 93.4% in patients with lung cancer. Notably, Lu

et al (37) revealed that

integrating PET and CT features achieved optimal performance

(sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 98%; accuracy, 99%). These

findings collectively suggest that combining PET and CT parameters

may provide superior predictive value for adrenal metastases in

clinical practice. However, most previous studies included adrenal

masses of all sizes, limiting their applicability to solitary small

hyperattenuating lesions, a particularly challenging diagnostic

scenario where false-negative results frequently occur (1,19,34,35).

To address this limitation, the current study developed an SVM

model incorporating multiple clinically relevant PET and CT

features specifically for small adrenal lesions. The model

demonstrated robust performance, with a mean AUC of 0.913 and

accuracy of 84.3%. Notably, the clinical utility of the model was

enhanced by: i) Improving interpretability through feature

importance analysis, and ii) developing a simplified scoring system

to facilitate clinical staging decisions in patients with lung

cancer.

In the current linear SVM model, feature importance

was quantified by the mean absolute weight, where higher values

indicated stronger predictive contributions for adrenal metastases.

Among all features, SUVmax(adrenal) demonstrated the

weight of highest importance. This finding aligns with established

literature demonstrating the diagnostic value of metabolic

parameters such as SUVmax in detecting adrenal

metastases (18,20,38).

Koopman et al (38) reported

significantly higher SUVmax values in metastatic vs.

benign adrenal lesions, with optimal diagnostic performance (96%

sensitivity and specificity) at a cutoff of 3.7 for detecting

metastatic adrenal lesions in patients with lung cancer. The

biological basis for this observation relates to SUV being a

surrogate for Km (the absolute metabolic rate of glucose

consumption). Malignant lesions typically exhibit elevated Km

values due to their characteristically increased glucose metabolism

(39). The prominent weight of

SUVmax(adrenal) in the present model substantiates its

critical diagnostic role. Additionally, SUVmax(lung)

showed considerable predictive weight, suggesting that higher

metabolic activity in primary lung tumors may be associated with

greater metastatic potential. This association has been previously

documented (40,41): Zhang et al (40) identified primary tumor

SUVmax as a significant predictor of lymph node

metastasis and Zhu et al (41) similarly reported that elevated

SUVmax in non-small cell lung cancer is associated with

increased metastatic risk.

Multiple studies have established that while PET

features may yield false-negative results in cases of

micro-metastases, integrated PET/CT demonstrates superior

diagnostic accuracy for detecting adrenal metastases compared with

PET or CT alone (1,36,37).

This underscores the importance of incorporating CT features to

enhance diagnostic performance. The present analysis revealed that

unenhanced CT value served a corrective function in the model. This

finding aligns with the existing literature demonstrating that

adrenal metastases typically exhibit higher attenuation values than

benign lesions (36,42). For example, Cho et al

(36) reported significant

differences in unenhanced CT values between metastatic (29±8 HU)

and non-metastatic (9±13 HU) adrenal lesions, with a HU threshold

of >18 achieving an AUC of 0.925 (sensitivity, 86.7%;

specificity, 81.2%; accuracy, 85.2%). Chen et al (43) subsequently identified a pre-contrast

CT value of >30 HU as an independent predictor of metastases

(AUC, 0.766), a potentially more robust criterion. The underlying

pathophysiology relates to adipose tissue content, which serves as

a key diagnostic marker for adenomas (42). The present results corroborate these

established attenuation patterns. Furthermore, lesion size emerged

as another significant CT parameter, with metastases typically

demonstrating larger dimensions than benign lesions, which was

consistent with previous research (23,34).

Evans et al (34) documented

markedly larger metastatic lesions (mean, 3.0 cm; range, 1.0–9.2

cm) vs. benign lesions (mean, 1.9 cm; range, 0.7–5.3 cm). In

addition, Orzechowski et al (23) reported that a size threshold of

>25 mm yielded 83.33% sensitivity, 83.64% specificity and 83.49%

accuracy for metastasis detection.

The location and homogeneity of adrenal lesions also

contributed to the present predictive model. It was observed that

adrenal metastases demonstrated a left-sided predominance and more

heterogeneous appearance, consistent with prior studies (22,43).

However, the mean absolute weights for these features were markedly

lower than those of the four primary parameters

[SUVmax(adrenal), SUVmax(lung), unenhanced CT

value and size].

The current study has several limitations that

should be acknowledged. First, the subjective interpretation of

certain imaging features (particularly lesion homogeneity) may vary

between radiologists, with more experienced practitioners likely

demonstrating greater diagnostic accuracy. Future incorporation of

computer-assisted feature evaluation could enhance measurement

reproducibility and model stability. Second, as a single-center

study with a relatively small sample size, the findings may be

specific to the particular PET system, acquisition protocol and

reconstruction algorithm employed. Multi-center validation studies

with larger cohorts are needed to establish the generalizability of

the coefficients across different imaging platforms. Third, in the

21 patients with interval development of adrenal metastases, the

SUVmax of the primary lung cancer may have changed due

to tumor progression or recurrence. Future studies with larger

cohorts are warranted to systematically assess whether the change

in SUVmax has diagnostic value in differentiating

adrenal metastases and whether it affects the performance of the

model. Fourth, it is notable that some of the patients with lung

cancer included in the present study also had comorbid fatty liver.

Hepatic steatosis in patients with cancer may alter metabolic

activity and influence 18F-FDG uptake (44). Although the SUR was not a parameter

in the final model, further corrections should be considered in

future studies when the liver is used as a comparator for PET-CT

scans in patients with lung cancer.

In conclusion, the present study describes the

development of an interpretable SVM model using 18F-FDG

PET/CT features to predict adrenal metastases in patients with lung

cancer. The model identified SUVmax(adrenal) as the most

significant predictor, followed by SUVmax(lung),

unenhanced CT value, size, homogeneity and location. For clinical

implementation, the SVM model was simplified into a practical

scoring system that may facilitate staging decisions for patients

with lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study received funding from the Tangshan City Key Research

and Development Program (grant no. 24150216C).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LZ, HC, WZ, JL, YL and LC designed the study. ZL, CH

and ZW collected the patient images, performed the statistical

analysis and wrote the manuscript. CL, LJ and LY critically

reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and

have read and approved the final manuscript. CL and ZL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of Tangshan People's Hospital (Tangshan, China). The

requirement for informed consent was waived due to the

retrospective nature of the study, and the study was performed in

accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AUC

|

area under the receiver operating

characteristic curve

|

|

FDG

|

fluorodeoxyglucose

|

|

KNN

|

k-nearest neighbor

|

|

LD

|

long diameter

|

|

PET/CT

|

positron emission tomography/computed

tomography

|

|

ROI

|

region of interest

|

|

SVM

|

support vector machine

|

|

SD

|

short diameter

|

|

SUVmax

|

maximum standardized uptake value

|

|

SURadrenal/liver

|

adrenal-to-liver SUVmax

ratio

|

|

SURlung/liver

|

lung-to-liver SUVmax

ratio

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Besse B, Adjei A, Baas P, Meldgaard P,

Nicolson M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Smit EF, Syrigos K, Stahel R, et

al: 2nd ESMO consensus conference on lung cancer: Non-small-cell

lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in

advanced disease. Ann Oncol. 25:1475–1484. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Burt M, Heelan RT, Coit D, McCormack PM,

Bains MS, Martini N, Rusch V and Ginsberg RJ: Prospective

evaluation of unilateral adrenal masses in patients with operable

non-small-cell lung cancer. Impact of magnetic resonance imaging. J

Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 107:584–599. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kawai N, Tozawa K, Yasui T, Moritoki Y,

Sasaki H, Yano M, Fujii Y and Kohri K: Laparoscopic adrenalectomy

for solitary adrenal metastasis from lung cancer. JSLS.

18:e2014.00062. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Porte HL, Roumilhac D, Graziana JP, Eraldi

L, Cordonier C, Puech P and Wurtz AJ: Adrenalectomy for a solitary

adrenal metastasis from lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 65:331–335.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gao XL, Zhang KW, Tang MB, Zhang KJ, Fang

LN and Liu W: Pooled analysis for surgical treatment for isolated

adrenal metastasis and non-small cell lung cancer. Interact

Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 24:1–7. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Holy R, Piroth M, Pinkawa M and Eble MJ:

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for treatment of adrenal

gland metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Strahlenther

Onkol. 187:245–251. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cao L, Yang H, Yao D, Cai H, Wu H, Yu Y,

Zhu L, Xu W, Liu Y and Li J: Clinical-imaging-radiomic nomogram

based on unenhanced CT effectively predicts adrenal metastases in

patients with lung cancer with small hyperattenuating adrenal

incidentalomas. Oncol Lett. 28:3402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Brady MJ, Thomas J, Wong TZ, Franklin KM,

Ho LM and Paulson EK: Adrenal nodules at FDG PET/CT in patients

known to have or suspected of having lung cancer: A proposal for an

efficient diagnostic algorithm. Radiology. 250:523–530. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zeiger MA, Siegelman SS and Hamrahian AH:

Medical and surgical evaluation and treatment of adrenal

incidentalomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 96:2004–2015. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cao L, Yang H, Wu H, Zhong H, Cai H, Yu Y,

Zhu L, Liu Y and Li J: Adrenal indeterminate nodules: CT-based

radiomics analysis of different machine learning models for

predicting adrenal metastases in lung cancer patients. Front Oncol.

14:14112142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Caoili EM, Korobkin M, Francis IR, Cohan

RH, Platt JF, Dunnick NR and Raghupathi KI: Adrenal masses:

Characterization with combined unenhanced and delayed enhanced CT.

Radiology. 222:629–633. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fujiyoshi F, Nakajo M, Fukukura Y and

Tsuchimochi S: Characterization of adrenal tumors by chemical shift

fast low-angle shot MR imaging: Comparison of four methods of

quantitative evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 180:1649–1657. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mayo-Smith WW, Song JH, Boland GL, Francis

IR, Israel GM, Mazzaglia PJ, Berland LL and Pandharipande PV:

Management of incidental adrenal masses: A white paper of the ACR

incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 14:1038–1044.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Haider MA, Ghai S, Jhaveri K and Lockwood

G: Chemical shift MR imaging of hyperattenuating (>10 HU)

adrenal masses: Does it still have a role? Radiology. 231:711–716.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Koo HJ, Choi HJ, Kim HJ, Kim SO and Cho

KS: The value of 15-minute delayed contrast-enhanced CT to

differentiate hyperattenuating adrenal masses compared with

chemical shift MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 24:1410–1420. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hsiao R, Chow A, Kluijfhout WP, Bongers

PJ, Verzijl R, Metser U, Veit-Haibach P and Pasternak JD: The

clinical consequences of functional adrenal uptake in the absence

of cross-sectional mass on FDG-PET/CT in oncology patients.

Langenbecks Arch Surg. 407:1677–1684. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Arikan AE, Makay O, Teksoz S, Vatansever

S, Alptekin H, Albeniz G, Demir A, Ozpek A and Tunca F: Efficacy of

PET-CT in the prediction of metastatic adrenal masses that are

detected on follow-up of the patients with prior nonadrenal

malignancy: A nationwide multicenter case-control study. Medicine

(Baltimore). 101:e302142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lang BH, Cowling BJ, Li JY, Wong KP and

Wan KY: High false positivity in positron emission tomography is a

potential diagnostic pitfall in patients with suspected adrenal

metastasis. World J Surg. 39:1902–1908. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Detterbeck FC, Woodard GA, Bader AS, Dacic

S, Grant MJ, Park HS and Tanoue LT: The proposed ninth edition TNM

classification of lung cancer. Chest. 166:882–895. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Vos EL, Grewal RK, Russo AE, Reidy-Lagunes

D, Untch BR, Gavane SC, Boucai L, Geer E, Gopalan A, Chou JF, et

al: Predicting malignancy in patients with adrenal tumors using

18F-FDG-PET/CT SUVmax. J Surg Oncol. 122:1821–1826.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xu B, Gao J, Cui L, Wang H, Guan Z, Yao S,

Shen Z and Tian J: Characterization of adrenal metastatic cancer

using FDG PET/CT. Neoplasma. 59:92–99. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Orzechowski S, Gnass M, Czyżewski D,

Wojtacha J, Sudoł B, Pankowski J, Zajęcki W, Ćmiel A, Zieliński M

and Szlubowski A: Ultrasound predictors of left adrenal metastasis

in patients with lung cancer: A comparison of computed tomography,

positron emission tomography-computed tomography, and endoscopic

ultrasound using ultrasound bronchoscope. Pol Arch Intern Med.

132:161272022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Noble WS: What is a support vector

machine? Nat Biotechnol. 24:1565–1567. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yin G, Song Y, Li X, Zhu L, Su Q, Dai D

and Xu W: Prediction of mediastinal lymph node metastasis based on

18F-FDG PET/CT imaging using support vector machine in

non-small cell lung cancer. Eur Radiol. 31:3983–3992. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang R, Zhu L, Cai Z, Jiang W, Li J, Yang

C, Yu C, Jiang B, Wang W, Xu W, et al: Potential feature

exploration and model development based on 18F-FDG PET/CT images

for differentiating benign and malignant lung lesions. Eur J

Radiol. 121:1087352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH and

Van den Abbeele AD: Revised RECIST guideline version 1.1: What

oncologists want to know and what radiologists need to know. AJR Am

J Roentgenol. 195:281–289. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liang M, Su Q, Mouraux A and Iannetti GD:

Spatial patterns of brain activity preferentially reflecting

transient pain and stimulus intensity. Cereb Cortex. 29:2211–2227.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mendez AM, Petre EN, Ziv E, Ridouani F,

Solomon SB, Sotirchos V, Zhao K and Alexander ES: Safety and

efficacy of thermal ablation of adrenal metastases secondary to

lung cancer. Surg Oncol. 55:1021022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Andersen MB, Bodtger U, Andersen IR,

Thorup KS, Ganeshan B and Rasmussen F: Metastases or benign adrenal

lesions in patients with histopathological verification of lung

cancer: Can CT texture analysis distinguish? Eur J Radiol.

138:1096642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Al Fares HK, Abdullaj S, Gokden N and

Menon LP: Incidental, solitary, and unilateral adrenal metastasis

as the initial manifestation of lung adenocarcinoma. Cureus.

14:e326282022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hashimoto K, Nishimura S and Akagi M: Lung

adenocarcinoma presenting as a soft tissue metastasis to the

shoulder: A case report. Medicina (Kaunas). 57:1812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lococo F, Patricelli G, Galeone C and

Rapicetta C: eComment. Surgery for isolated adrenal metastasis from

non-small-cell lung cancer: The role of preoperative PET/CT scan'.

Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 24:72017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Evans PD, Miller CM, Marin D, Stinnett SS,

Wong TZ, Paulson EK and Ho LM: FDG-PET/CT characterization of

adrenal nodules: Diagnostic accuracy and interreader agreement

using quantitative and qualitative methods. Acad Radiol.

20:923–929. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kim BS, Lee JD and Kang WJ:

Differentiation of an adrenal mass in patients with non-small cell

lung cancer by means of a normal range of adrenal standardized

uptake values on FDG PET/CT. Ann Nucl Med. 29:276–283. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Cho AR, Lim I, Na II, Choe du H, Park JY,

Kim BI, Cheon GJ, Choi CW and Lim SM: Evaluation of adrenal masses

in lung cancer patients using F-18 FDG PET/CT. Nucl Med Mol

Imaging. 45:52–58. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lu Y, Xie D, Huang W, Gong H and Yu J:

18F-FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of adrenal masses in lung cancer

patients. Neoplasma. 57:129–134. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Koopman D, van Dalen JA, Stigt JA, Slump

CH, Knollema S and Jager PL: Current generation time-of-flight

(18)F-FDG PET/CT provides higher SUVs for normal adrenal glands,

while maintaining an accurate characterization of benign and

malignant glands. Ann Nucl Med. 30:145–152. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Smith TA: Facilitative glucose transporter

expression in human cancer tissue. Br J Biomed Sci. 56:285–292.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang S, Li S, Pei Y, Huang M, Lu F, Zheng

Q, Li N and Yang Y: Impact of maximum standardized uptake value of

non-small cell lung cancer on detecting lymph node involvement in

potential stereotactic body radiotherapy candidates. J Thorac Dis.

9:1023–1031. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhu SH, Zhang Y, Yu YH, Fu Z, Kong L, Han

DL, Fu L, Yu JM and Li J: FDG PET-CT in non-small cell lung cancer:

Relationship between primary tumor FDG uptake and extensional or

metastatic potential. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 14:2925–2929. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Sherlock M, Scarsbrook A, Abbas A, Fraser

S, Limumpornpetch P, Dineen R and Stewart PM: Adrenal

incidentaloma. Endocr Rev. 41:775–820. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen J, He Y, Zeng X, Zhu S and Li F:

Distinguishing between metastatic and benign adrenal masses in

patients with extra-adrenal malignancies. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:9787302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ali MA, El-Abd E, Morsi M, El Safwany MM

and El-Sayed MZ: The effect of hepatic steatosis on 18F-FDG uptake

in PET-CT examinations of cancer Egyptian patients. Eur J Hybrid

Imaging. 7:192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|