Introduction

Breast fat necrosis is a relatively uncommon benign

breast condition, with an overall incidence of ~0.6%, accounting

for 2.75% of all benign breast lesions (1). The pathogenesis of fat necrosis

includes a non-suppurative inflammatory process of adipose tissue,

fundamentally caused by aseptic fat saponification. Common causes

of fat necrosis include trauma, surgery, radiotherapy,

anticoagulant therapy or idiopathic factors (2). It is key to diagnose fat necrosis

because it often mimics breast cancer, which can lead to

unnecessary biopsies of breast lesions. Breast cancer is a

heterogeneous disease influenced by both genetic and environmental

factors. Key genetic factors involve high-penetrance mutations

(e.g., BRCA1/2) and family history, the latter conferring a

2–3-fold risk increase with an affected first-degree relative.

Modifiable risks encompass prolonged estrogen exposure, lifestyle

factors like postmenopausal obesity and alcohol use, and

reproductive history such as nulliparity and late first birth

(3). Globally, it is one of the

most common female cancers, representing 25% of new cases and

accounting for 2.1 million diagnoses in 2018 (3). Invasive breast cancer is the most

frequent subtype, with the main pathological types being invasive

ductal carcinoma (70–80%) and invasive lobular carcinoma (5–15%)

(3). The occurrence of massive

breast fat necrosis associated with a small focus of invasive

breast cancer is relatively uncommon, with, to the best of our

knowledge, only 5 cases reported in the literature, all including a

history of seatbelt trauma from road traffic accidents (4). The imaging differentiation between

breast fat necrosis and breast cancer presents notable diagnostic

challenges. Breast fat necrosis can mimic several imaging features

of breast cancer, such as spiculated margins due to fibrosis or

inflammatory reactions, calcification foci resulting from

saponification of necrotic cells and irregular enhancement patterns

on contrast-enhanced scans similar to those seen in malignant

tumors (5–7). This notable overlap in imaging

manifestations has led to breast fat necrosis being termed the

‘great mimicker’ (8,9). While current studies primarily focus

on differentiating between these two entities, the imaging

characteristics of their coexistence remain insufficiently explored

(10–12). The present study reported a case

primarily characterized by the relatively uncommon coexistence of

massive breast fat necrosis with invasive breast cancer,

emphasizing the key role of imaging findings in diagnosis to

prevent overlooking malignant foci hidden within benign

lesions.

Case report

A 74-year-old female patient was admitted to The

Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (The First

People's Hospital of Zunyi) (Zunyi, China) in March 2023 with a

2-month history of a palpable nodule in the left breast,

accompanied by intermittent swelling and self-perceived distending

pain. On physical examination, a mass measuring ~2.0×1.0 cm was

identified at the 2 o'clock position of the left breast, 4 cm from

the nipple. The mass was hard, had an irregular surface, poorly

defined margins and an irregular shape, with limited mobility and

no tenderness. When the patient and their family were queried

regarding a relevant medical history, the patient and their family

denied having a history of trauma, surgery, radiotherapy,

anticoagulant therapy or other relevant medical histories. No

notable abnormalities were identified in other examinations.

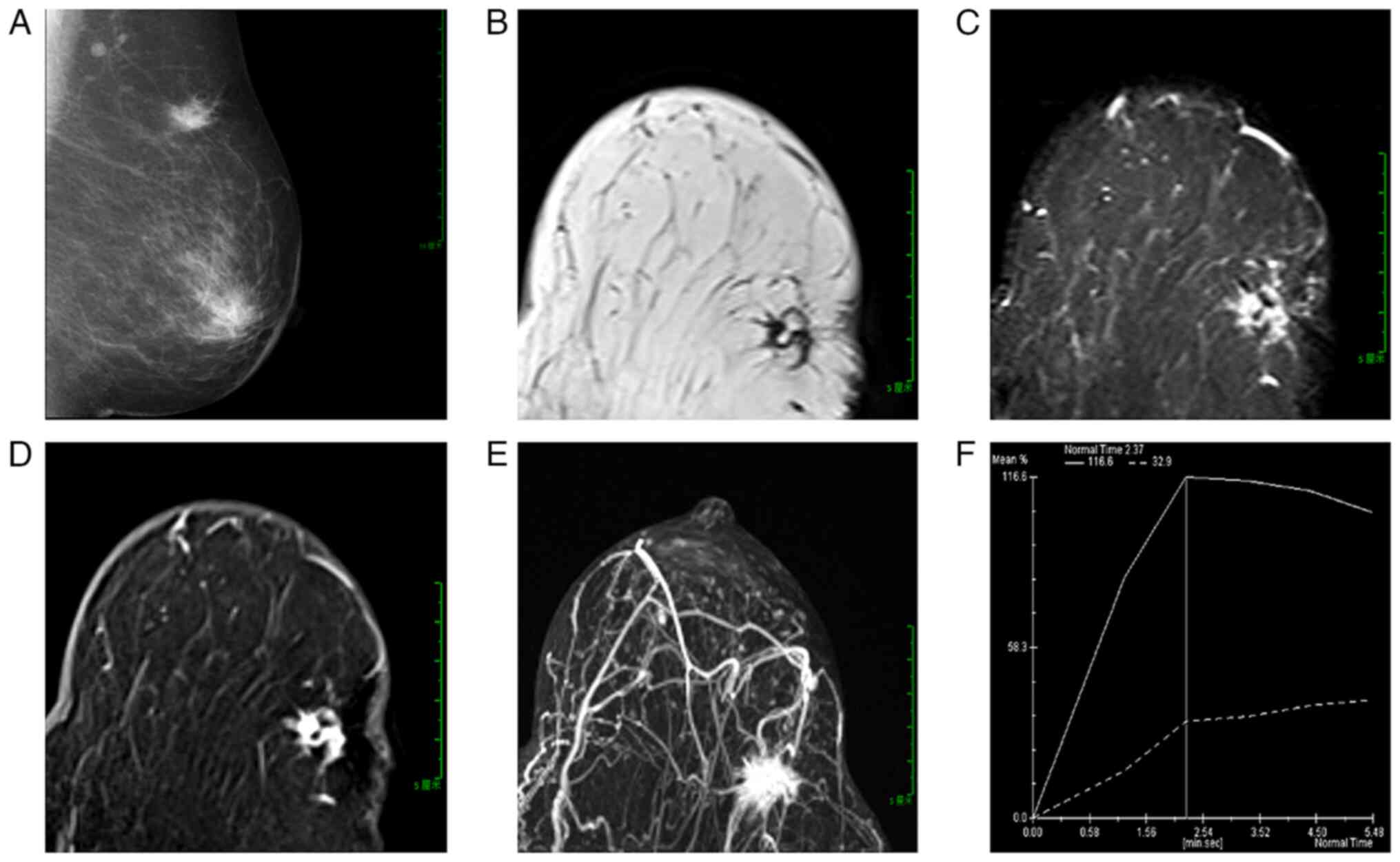

In March 2023, mammography revealed an irregular,

high-density mass in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast,

located 8.6 cm from the nipple, with a diameter of ~2.1 cm. The

lesion exhibited indistinct margins and spiculated edges (Fig. 1A). The mammographic findings

suggested a mass in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast,

highly suspicious for breast cancer.

In March 2023, MRI revealed an irregular lesion in

the upper outer quadrant of the left breast, 7.0 cm from the

nipple, measuring ~2.2×1.2×1.2 cm. The lesion had poorly defined

margins and spiculated edges. On T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), it

appeared hypointense with small focal areas of hyperintensity

(Fig. 1B). On fat-suppressed T1WI,

the focal areas appeared hypointense. On fat-suppressed T2WI, the

lesion exhibited slightly hyperintense signals with focal

hypointense areas that were lower in intensity compared with

surrounding fat, forming a ‘black hole sign’ (Fig. 1C). Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI)

revealed heterogeneous hyperintensity, while apparent diffusion

coefficient (ADC) mapping revealed hypointensity. A

contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrated marked heterogeneous enhancement

in the early phase, with patchy non-enhancing areas within the

lesion (Fig. 1E). The

time-intensity curve (TIC) displayed a washout pattern (Fig. 1D). Maximum intensity projection

images indicated a rich blood supply to the mass (Fig. 1F). Based on MRI findings, the lesion

in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast was considered

consistent with fat necrosis.

In March 2023, surgical excision of the mass and

surrounding normal glandular tissue (weighing 50 g) was performed.

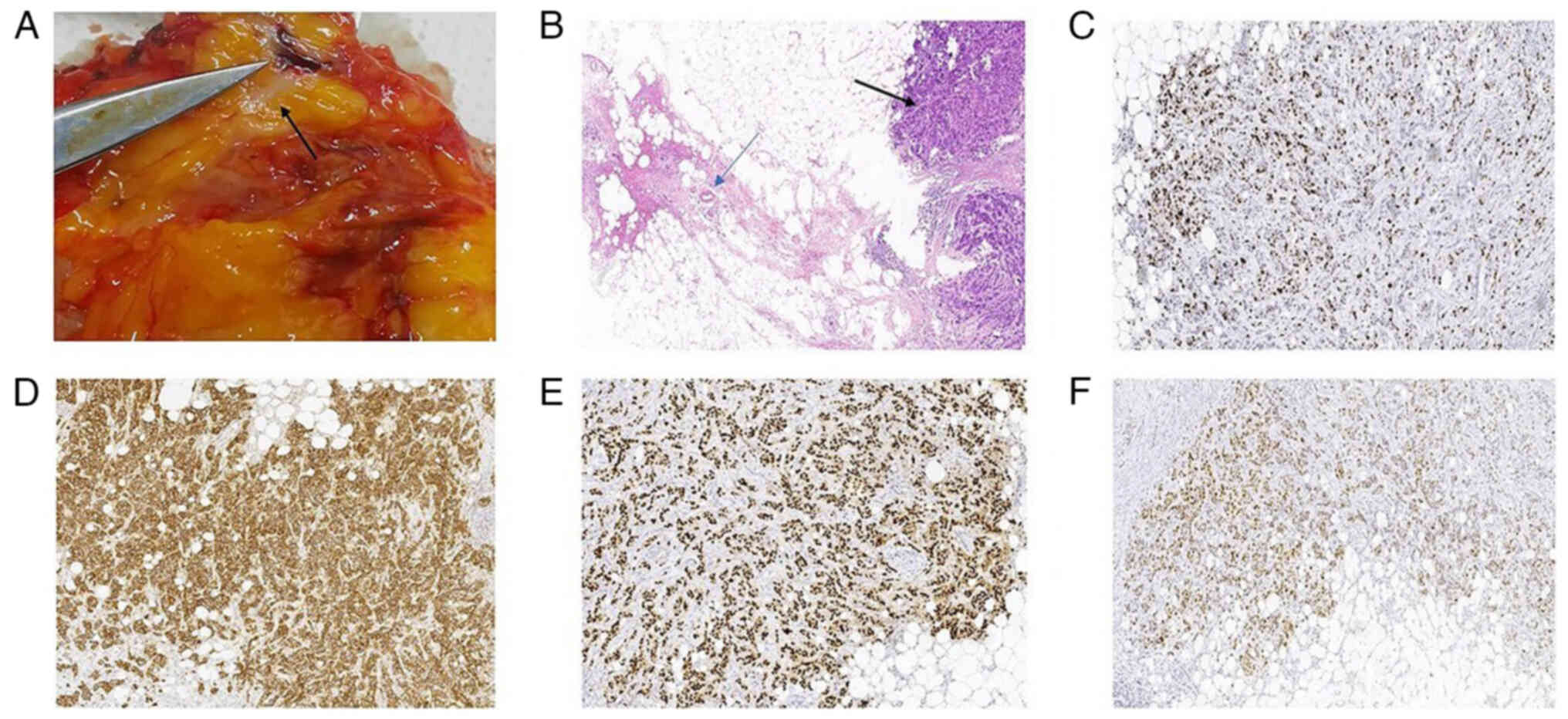

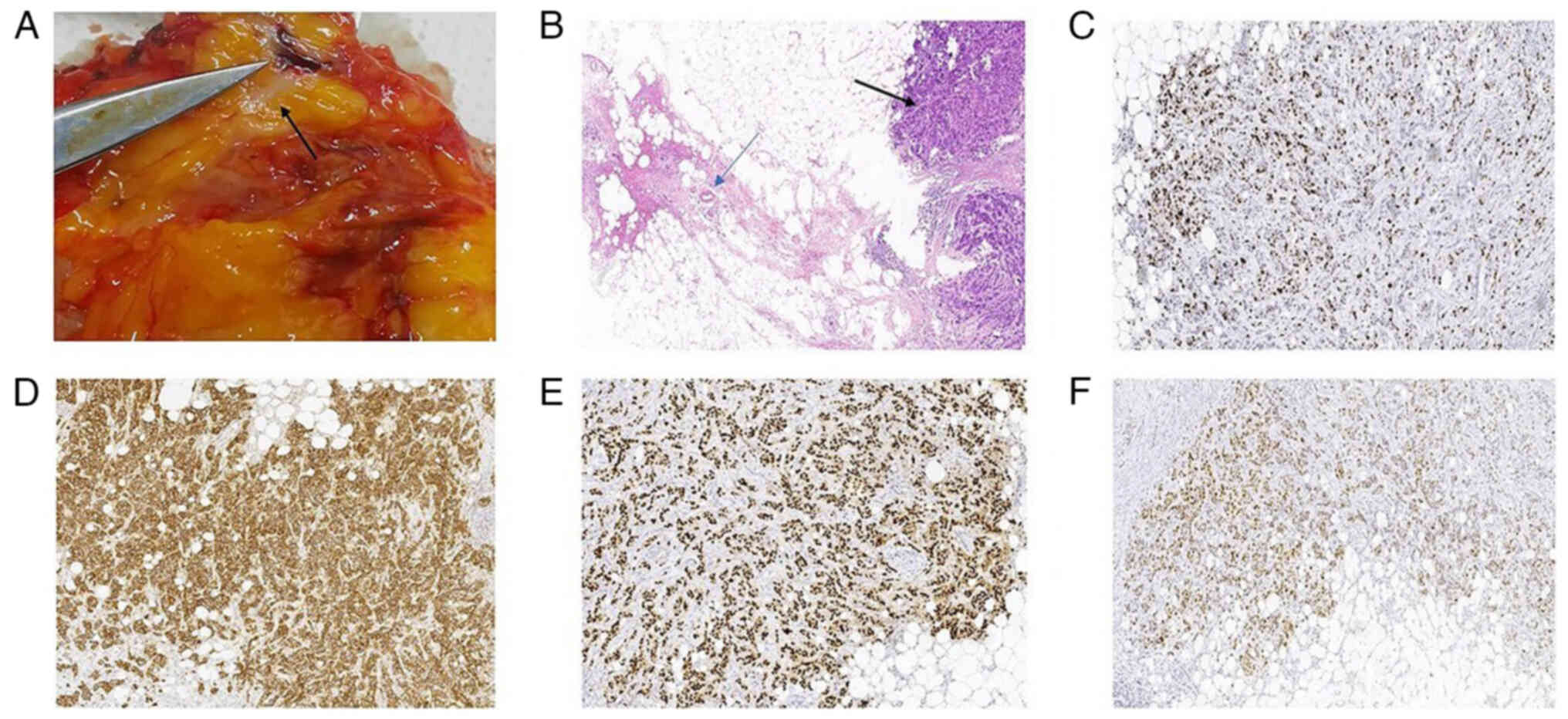

A gross examination of the specimen revealed extensive gray-yellow

necrotic fat interspersed with white, speckled cancerous foci

(Fig. 2A). The histopathological

analysis performed in March 2023 using hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E) staining (Fig. 2B)

confirmed invasive breast carcinoma with focal fat necrosis in the

surrounding tissue. For H&E staining, surgical specimens were

fixed in formalin at room temperature for 12 h, followed by

paraffin embedding and sectioning into 4-µm slices. The sections

were baked at 70°C for 1 h, deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated

through a graded alcohol series at room temperature. The sections

were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min and eosin for 1 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, the sections were dehydrated through a

graded alcohol series, cleared in xylene and mounted with neutral

balsam for examination under a DM750 light microscope (Leica

Microsystems). Immunohistochemical analysis was conducted manually

on 4-µm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. After

baking at 70°C for 1 h, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated through a graded alcohol series. Antigen retrieval was

performed under high pressure at 100°C using either EDTA (pH 9.0)

or citrate-based buffer (pH 6.0) according to the specific

requirements of each primary antibody (7 min at full pressure

followed by 5 min standing). Following cooling and PBS rinses,

endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3%

H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature. Sections

were then incubated with primary antibodies from Tongling

Biotechnology (50–100 µl/section) at 37°C for 1 h, all primary

antibodies were used at ready-to-use concentration including Ki-67

(cat. no. AM0241; EDTA pretreatment), erythroblastic oncogene B-2

receptor (c-erbB-2) (cat. no. AM0037; EDTA), non-metastatic protein

23 (nm 23) (cat. no. AM0382; EDTA), estrogen receptor (ER) (cat.

no. AR0710; CBS), progesterone receptor (PR) (cat. no. AR0711;

CBS), E-cadherin (cat. no. AR0240; EDTA), epidermal growth factor

receptor (EGFR) (cat. no. AR0251; EDTA), cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6)

(cat. no. AM0101; EDTA), p63 (cat. no. AM0186; EDTA), and p120

(cat. no. AM0268; EDTA). After PBS washes, sections were incubated

with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. DD13; Tongling

Biotechnology) at 37°C for 30 min, followed by DAB development

(cat. no. KS-005A/B; Tongling Biotechnology) for 5 min at room

temperature. Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin for 1

min at room temperature, followed by differentiation in 1%

hydrochloric acid-alcohol solution (1% HCl in 70% ethanol).

Finally, sections were dehydrated through graded alcohols,

air-dried and mounted for examination under a DM750 light

microscope (Leica Microsystems). In March 2023, immunohistochemical

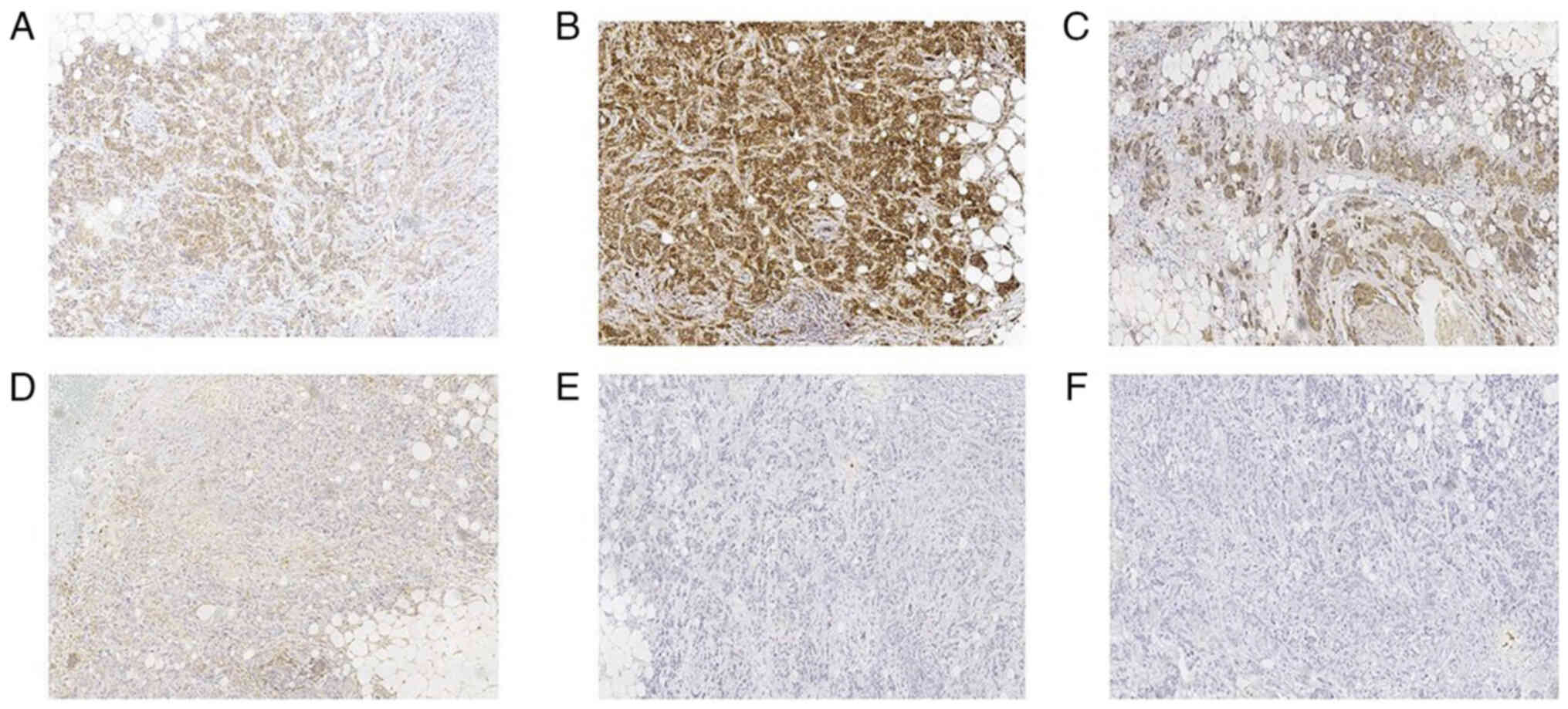

staining revealed positive expression of Ki-67 (+; ~45%) (Fig. 2C), E-cadherin (+) (Fig. 2D), ER (3+; ~90%) (Fig. 2E), PR (+; ~50%) (Fig. 2F), c-erbB-2 (+) (Fig. 3A), p120 (on the tumor cell membrane

+) (Fig. 3B) and nm23 (+) (Fig. 3C), while EGFR (Fig. 3D), CK5/6 (Fig. 3E) and p63 (Fig. 3F) were negative. The date of last

follow-up was September 2025, with annual telephone follow-ups

conducted.

| Figure 2.(A) The gross specimen exhibits

extensive gray-yellow necrotic fat with white spot-like cancer foci

(indicated by the black arrow). (B) Fat necrosis and invasive

breast cancer (H&E stain): The area indicated by the blue arrow

displays ruptured or disrupted adipocytes, with their normal round

structure destroyed. Macrophages are visible. The area indicated by

the black arrow displays highly heterogeneous cancer cell

morphology and size, with an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio.

The cancer cell cytoplasm stains light pink, and the cancer cells

infiltrate the surrounding fibrous stroma in a cord-like pattern

(magnification, ×5). (C) Invasive breast cancer (Ki-67):

Ki-67+ cells have brownish-yellow-stained nuclei. The

positive staining is confined to the cell nucleus, with no staining

in the cytoplasm. (D) Invasive breast cancer (E-cadherin):

E-cadherin(+) displays brownish-yellow positive staining on the

cancer cell membranes, with staining primarily localized to the

cell membrane, suggesting that the cancer cells still retain some

adhesive function. (E) Invasive breast cancer (ER): ER+

cells have brownish-yellow-stained nuclei. (F) Invasive breast

cancer (PR): PR+ cells have brownish-yellow-stained

nuclei (magnification, ×10). ER, estrogen receptor; PR,

progesterone receptor. |

Discussion

Breast fat necrosis is a common benign breast

condition with imaging features that often mimic breast cancer,

such as spiculated margins due to fibrosis or inflammatory

reactions, calcification foci resulting from saponification of

necrotic cells and irregular enhancement patterns on

contrast-enhanced scans similar to those seen in malignant tumors

(5–7). Breast fat necrosis is characterized by

granulomatous inflammation resulting from the enzymatic

liquefaction of necrotic tissue. The process of fat necrosis has

four stages: i) The hyperacute stage; ii) the acute inflammatory

stage; iii) the oil cyst formation stage; and iv) the chronic

granulomatous reaction stage. Each stage exhibits distinct imaging

characteristics. When the imaging findings resemble those of

malignancy, a pathological examination is required for a definitive

diagnosis (5,8). Invasive breast cancer is defined by

the penetration of cancer cells through the basement membrane into

the breast stroma, resulting in a higher degree of malignancy and

an increased risk of metastasis compared with non-invasive breast

cancer (13,14).

The patient was admitted to The Third Affiliated

Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (The First People's Hospital

of Zunyi); Zunyi, China) in March 2023 due to a palpable left

breast nodule for >2 months, accompanied by self-perceived

distending pain that occurred intermittently. Although the patient

reported no history of breast trauma or surgery, imaging

examinations are of notable necessity (15). This is because imaging examinations

can make up for the limitations of palpation, clearly display the

detailed characteristics of the nodule such as its size, shape,

boundary, internal echo, density or signal and whether it is

accompanied by calcification, and can even detect ‘occult or tiny

nodules’ that cannot be identified by palpation (16).

Breast fat necrosis and breast cancer can have

similar imaging appearances, which makes them difficult to

distinguish. On mammography, fat necrosis often presents as round

or oval low-density cysts with fat-fluid levels caused by the

separation of oil and serous fluid (17). As the condition progresses,

calcifications may develop (5). By

comparison, breast cancer appears on mammography as an irregular,

high-density mass with spiculated margins. The calcifications

associated with breast cancer are often described as clustered

microcalcifications or fine, irregular microcalcifications

(18). In the present case,

mammography revealed an irregular, high-density mass with unclear

borders and spiculated edges, features highly suggestive of breast

cancer. However, mammography has limited tissue-specific resolution

and previous reports have indicated that fat necrosis can mimic

malignant tumors (8,9,12).

Therefore, breast MRI is necessary, as it provides more detailed

information using multiparametric imaging techniques.

In breast MRI, fat necrosis often appears as a

hyperintense lesion on T1WI and T2WI, becoming hypointense on

fat-suppressed images, with a typically clear border. However,

fibrosis or inflammation may cause slight spiculation. On enhanced

scanning, it often exhibits no enhancement or only rim enhancement.

However, enhancing fat necrosis mimicking malignancy can exhibit

irregular mass enhancement (9),

with a varied TIC to a certain extent similar to breast cancer,

making differentiation difficult (5). Notably, on inversion recovery

sequences, most intracellular lipids, such as those in lipid-rich

mammary lesions (19) and the

triglyceride droplets of breast hamartomas (20) indicate marked signal reduction.

However, fat necrosis has a lower signal intensity compared with

surrounding normal fat, termed the ‘black hole’ sign, considered

specific for fat necrosis. This is because the necrotic fat is

replaced by fibrosis, calcification or fluid, with a narrower

distribution of T1 relaxation times around the inversion time (TI),

the specific time delay used in an MRI inversion recovery pulse

sequence, leading to more complete fat suppression at specific TI

times. The ‘black hole sign’ often presents in the oil cyst

formation stage (where the necrotic region undergoes cystic change

and liquefied fat is confined within the cyst cavity) and the

chronic granulomatous reaction stage (where the central necrotic

area is completely fibrotic, with or without calcification) of fat

necrosis. By contrast, breast cancer often lacks this sign

(19,21,22).

The ‘black hole’ sign seen in the breast MRI of the present case

suggested fat necrosis. However, apart from the characteristic

‘black hole’ sign of fat necrosis on MRI, other imaging features

were similar to those of breast cancer, making differentiation

difficult and prompting clinical vigilance and biopsy. The

histopathological analysis of the surgical specimen suggested that

the coexistence of massive mammary fat necrosis with invasive

breast cancer, which is a relatively uncommon clinical presentation

with only a few documented cases in the literature (4).

Previous studies have predominantly focused on

differentiating fat necrosis from breast cancer, yet they have

overlooked their imaging manifestations when they coexist (10–12).

In the present case, performing MRI after mammography was necessary

for accurate preoperative assessment of the lesion's size and

delineating the extent of the lesion. Firstly, mammography has

relatively weak tissue resolutions due to the interference of

breast glands (23,24), while the multi-parametric imaging

technology of MRI provides more detailed information, thus serving

a complementary role (25).

Furthermore, MRI can evaluate the condition of the contralateral

(healthy side) breast. It is worth noting that when mammography

suggests a malignant lesion, MRI becomes particularly key, as it

serves a key role in diagnosis and treatment (26). The present case highlighted that

even with the characteristic ‘black hole’ sign of fat necrosis on

MRI, if other imaging features resemble breast cancer and are

indistinguishable, the possibility of coexisting breast cancer

within fat necrosis should be considered.

Under the microscope, fat necrosis is characterized

by ruptured adipocytes, infiltration of inflammatory cells,

saponification of fat, formation of foam cells and fibrosis

(2,21,27,28).

The pathological features of invasive ductal carcinoma of the

breast include cellular atypia, loss of normal glandular

architecture (14,29), and immunohistochemical staining

results demonstrated negative expression for myoepithelial markers

CK5/6 and p63 and positive expression of p120 and E-cadherin. Fat

necrosis is a proliferative condition often induced by hypoxia

(27). Following ischemic injury,

adipocyte rupture alters the tumor microenvironment, creating

conditions that may promote cancer development (30).

The differential diagnosis between breast fat

necrosis and invasive breast cancer requires distinguishing it from

conditions such as breast sarcoma, inflammatory breast cancer (IBC)

and simple invasive breast cancer. Breast sarcoma often includes

the entire breast, with rare calcification and axillary

lymphadenopathy. On T1WI, it reveals isointensity or

hyperintensity, except in necrotic or cystic areas. The TIC of

breast sarcoma demonstrates washout, indicating slow enhancement

and heterogeneous signal intensity (SI) distribution (31). IBC presents with specific

mammography and MRI features, such as breast enlargement and

diffuse or nodular skin thickening. Lesions are often multifocal

and widespread, making accurate tumor size measurement challenging

(32). Pure infiltrating ductal

carcinoma generally appears on mammography as an irregular,

spiculated, dense mass with malignant calcification. On MRI, it

exhibits mixed T2WI signals, with SI dependent on internal

components. Enhancement can be homogeneous, heterogeneous or

rim-like, and TIC demonstrates washout. On DWI, it demonstrates

hyperintense and hypointense signals on ADC, indicating restricted

diffusion (33,34). Pure breast fat necrosis has distinct

imaging characteristics. The imaging presentation depends on the

stage of fat necrosis, the degree of inflammatory reaction, the

amount of liquefied fat, fibrosis and calcifications, as well as

the etiology of the fat necrosis. Therefore, knowledge of imaging

appearances of fat necrosis at different stages is essential for a

radiologist to make accurate interpretation and avoid unnecessary

invasive workup (35). Mammography

of fat necrosis often reveals well-defined, low-density oil cysts,

which may have coarse, ring-like or ‘eggshell’ calcifications. MRI

of fat necrosis often reveals hyperintensity on both T1WI and T2WI,

with clear margins. However, fibrosis or inflammation can cause

slight spiculation. The ‘black hole’ sign on T2WI fat-saturated

sequences is a specific marker for fat necrosis. Enhancement is

often absent or rim-like, with low restricted diffusion. In

summary, analyzing these imaging features can effectively

distinguish fat necrosis from invasive breast cancer and other

breast diseases, providing a reliable clinical diagnosis.

In conclusion, the present study reported a

relatively uncommon case of massive breast fat necrosis coexisting

with invasive breast cancer. Imaging findings reveal several

similarities between fat necrosis and breast cancer, often making

them difficult to differentiate. Although previous literature has

largely focused on the differential diagnosis between the two, the

present case highlighted the possibility of their concurrent

occurrence, with a minor focus on invasive breast cancer, which is

key for the improvement of diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the

present case provided additional evidence supporting the close

association between inflammation and cancer development, which

aligns with findings from previous related studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present case report was funded by Guizhou Provincial Natural

Science Foundation [grant no. Qian Ke He Jichu-ZK (2021) Yiban

479], Natural Science Foundation of Zunyi [grant no. Zun Shi Ke He

HZ Zi(2020) 143] and the First People's Hospital of Zunyi Yanjiu Yu

Shiyan Fazhan R&D [grant no. Yuan Ke Zi (2020) 9].

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures of this article.

Authors' contributions

AZ designed the present case report and wrote the

manuscript. LS, BT, YL, XY and XC performed all the experiments. GJ

provided data and preliminarily interpretated them. LJ performed

data analysis, conceptualization and critical review. GJ and LJ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Fat necrosis as a differential diagnosis

for recurrence in a treated case of breast cancer, . A case report

| Semantic Scholar.

|

|

2

|

Vasei N, Shishegar A, Ghalkhani F and

Darvishi M: Fat necrosis in the Breast: A systematic review of

clinical. Lipids Health Dis. 18:1392019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Houghton SC and Hankinson SE: Cancer

progress and priorities: Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers

Prev. 30:822–844. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Song CT, Teo I and Song C: Systematic

review of seat-belt trauma to the female breast: A new diagnosis

and management classification. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg.

68:382–389. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tayyab SJ, Adrada BE, Rauch GM and Yang

WT: A pictorial review: Multimodality imaging of benign and

suspicious features of fat necrosis in the breast. Br J Radiol.

91:201802132018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Taboada JL, Stephens TW, Krishnamurthy S,

Brandt KR and Whitman GJ: The many faces of fat necrosis in the

breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 192:815–825. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Daly CP, Jaeger B and Sill DS: Variable

appearances of fat necrosis on breast MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

191:1374–1380. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ganau S, Tortajada L, Escribano F, Andreu

X and Sentís M: The great mimicker: Fat necrosis of the

breast-magnetic resonance mammography approach. Curr Probl Diagn

Radiol. 38:189–197. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Guirguis MS, Adrada B, Santiago L,

Candelaria R and Arribas E: Mimickers of breast malignancy: Imaging

findings, pathologic concordance and clinical management. Insights

Imaging. 12:532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nguyen QD and Kharsa A: Magnetic resonance

imaging enhancement two years post lumpectomy: An unusual timing

for fat necrosis. Cureus. 13:e147942021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Parikh RP, Doren EL, Mooney B, Sun WV,

Laronga C and Smith PD: Differentiating fat necrosis from recurrent

malignancy in fat-grafted breasts: An imaging classification system

to guide management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 130:761–772. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Adejolu M, Huo L, Rohren E, Santiago L and

Yang WT: False-positive lesions mimicking breast cancer on FDG PET

and PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 198:W304–W314. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang L: Mammography with deep learning for

breast cancer detection. Front Oncol. 14:12819222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen W, Wang G and Zhang G: Insights into

the transition of ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive ductal

carcinoma: Morphology, molecular portraits, and the tumor

microenvironment. Cancer Biol Med. 19:1487–1495. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Genova R and Garza RF: Breast Fat

Necrosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL):

2025

|

|

16

|

Kolb TM, Lichy J and Newhouse JH:

Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical

examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence

them: An analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology.

225:165–175. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Upadhyaya VS, Uppoor R and Shetty L:

Mammographic and sonographic features of fat necrosis of the

breast. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 23:366–372. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pulappadi VP, Dhamija E, Baby A, Mathur S,

Pandey S, Gogia A and Deo SVS: Imaging features of breast cancer

subtypes on mammography and ultrasonography: An analysis of 479

patients. Indian J Surg Oncol. 13:931–938. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Trimboli RM, Carbonaro LA, Cartia F, Di

Leo G and Sardanelli F: MRI of fat necrosis of the breast: The

‘black hole’ sign at short tau inversion recovery. Eur J Radiol.

81:e573–579. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mohamed A: Breast hamartoma: Unusual

radiological presentation. Radiol Case Rep. 15:2714–2717. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kerridge WD, Kryvenko ON, Thompson A and

Shah BA: Fat necrosis of the breast: A pictorial review of the

mammographic, ultrasound, CT, and MRI findings with histopathologic

correlation. Radiol Res Pract. 2015:6131392015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hassan HHM, El Abd AM, Abdel Bary A and

Naguib NNN: Fat necrosis of the Breast: Magnetic resonance imaging

characteristics and pathologic correlation. Acad Radiol.

25:985–992. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Melnikow J, Fenton JJ, Whitlock EP,

Miglioretti DL, Weyrich MS, Thompson JH and Shah K: Supplemental

Screening for breast cancer in women with dense breasts: A

Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD):

2016

|

|

24

|

Nakamura N, Okafuji Y, Adachi S, Takahashi

K, Nakakuma T and Ueno S: Effect of different breast densities and

average glandular dose on contrast to noise ratios in Full-field

digital mammography: Simulation and phantom study. Radiol Res

Pract. 2018:61925942018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Raikhlin A, Curpen B, Warner E, Betel C,

Wright B and Jong R: Breast MRI as an adjunct to mammography for

breast cancer screening in high-risk patients: Retrospective

review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 204:889–897. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Debruhl ND, Lee SJ, Mahoney MC, Hanna L,

Tuite C, Gatsonis CA and Lehman C: MRI Evaluation of the

contralateral breast in women with recently diagnosed breast

cancer: 2-Year Follow-up. J Breast Imaging. 2:50–55. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Majithia J, Haria P, Popat P, Katdare A,

Chouhan S, Gala KB, Kulkarni S and Thakur M: Fat necrosis: A

consultant's conundrum. Front Oncol. 12:9263962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, Opaluwa AS,

Ravikumar KH, Chetty N, Kaplan V, Kelley CJ and Babu ED: Fat

necrosis of the breast-a review. Breast. 15:313–318. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Nasrazadani A, Li Y, Fang Y, Shah O,

Atkinson JM, Lee JS, McAuliffe PF, Bhargava R, Tseng G, Lee AV, et

al: Mixed invasive ductal lobular carcinoma is clinically and

pathologically more similar to invasive lobular than ductal

carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 128:1030–1039. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Greten FR and Grivennikov SI: Inflammation

and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity.

51:27–41. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu WH, Ji QL, Li ZZ, Wang QN, Liu SY and

Yu JF: Mammography and MRI manifestations of breast angiosarcoma.

BMC Womens Health. 19:732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Papalouka V and Gilbert FJ: Inflammatory

breast cancer-importance of breast imaging. Eur J Surg Oncol.

44:1135–1138. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Langman EL, Kuzmiak CM, Brader R, Thomas

SM, Alexander SL, Lee SS and Jordan SG: Breast cancer in young

women: Imaging and clinical course. Breast J. 27:657–663. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen R, Hu B, Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhao L,

Jiang Y and Xu Y: Differential diagnosis of plasma cell mastitis

and invasive ductal carcinoma using multiparametric MRI. Gland

Surg. 9:278–290. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chan PYL, Wong T, Chau CM, Fung WY, Lai

KB, Chan RLS, Wong WCW, Yung WT and Ma JKF: Fat necrosis in the

breast: A multimodality imaging review of its natural course with

different aetiologies. Clin Radiol. 78:323–332. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|