Introduction

Gastrointestinal malignancies account for >25% of

the global incidence of all tumors and 35% of tumor-related

mortality, which poses a notable threat to the health of

individuals worldwide (1,2). Based on histological features,

gastrointestinal malignancies can be classified into

adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma and

undifferentiated carcinoma (3,4). Among

them, switch/sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) related matrix

associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin sub-family A

member 4 (SMARCA4)-deficient undifferentiated carcinoma (DUC) of

the gastrointestinal tract is a subtype of gastrointestinal

undifferentiated carcinoma (4,5).

SMARCA4 deficiency is more commonly observed in

non-small cell lung cancer, with an incidence of 5–10%. However, it

is relatively rare in gastrointestinal cancer types, with limited

reports available (6). The absence

of SMARCA4 in primary tumors is associated with higher tumor

invasiveness and a poorer prognosis. Compared with common tumors,

there may be differences in clinical features, imaging

manifestations, pathological characteristics and treatment

responses (7,8). A previous study validated that in 436

cancer cell lines, tumors with low SMARCA4 expression demonstrated

markedly higher IC50 values for multiple

chemotherapeutic drugs compared with those with high SMARCA4

expression, which implied that SMARCA4 deficiency may be a key

reason for patient drug resistance (9). Another previous study indicated that

SMARCA4 deficiency induces chemoresistance in tumor cells and also

activates the EMT process, which thereby enhances tumor invasion

(10). Therefore, additional

studies and reports of cases of SMARCA4-deficient gastrointestinal

undifferentiated carcinoma may enhance the current understanding of

its biological behavior and potentially provide key insights for

clinical diagnosis, the formulation of treatment strategies and

prognosis assessment in the future.

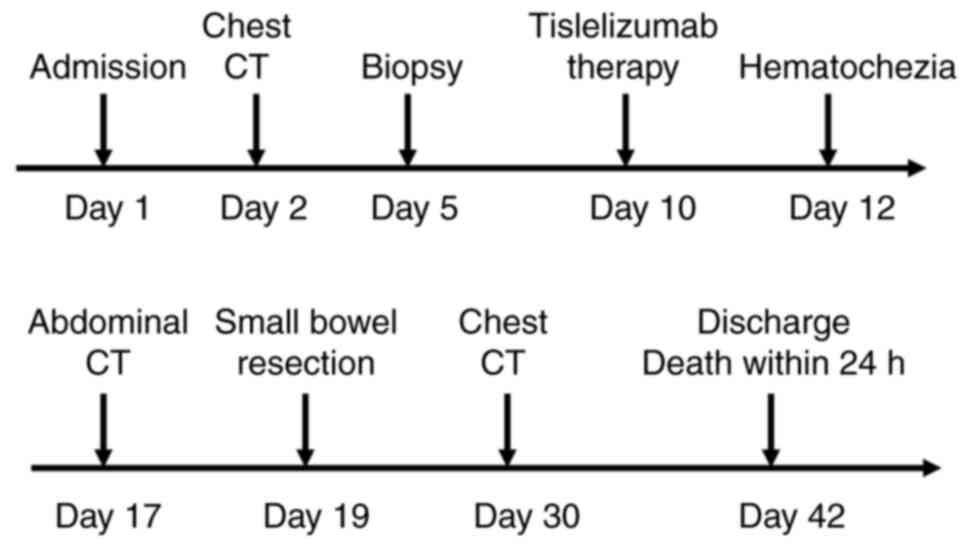

The present study aimed to report a rare case of

small intestinal SMARCA4-DUC. The patient presented with intestinal

intussusception and progression to metastasis in the lungs, liver,

spleen and skin. The condition of the patient deteriorated rapidly,

with death occurring 42 days following the initial detection of the

lesion. The present study aimed to provide a detailed description

of the clinical features, imaging manifestations, pathological

characteristics and molecular biological features of the present

case, to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of SMARCA4-deficient

gastrointestinal undifferentiated carcinoma.

Case report

A 69-year-old man with gastrointestinal discomfort

was admitted to Weifang No. 2 People's Hospital (Weifang, China) on

April, 2024 (day 1). The patient reported that they had suffered

from chronic gastritis and gastric ulcers for >10 years. The

mental health of the patient was poor at the time of admission,

with dyspnea and no other abnormalities.

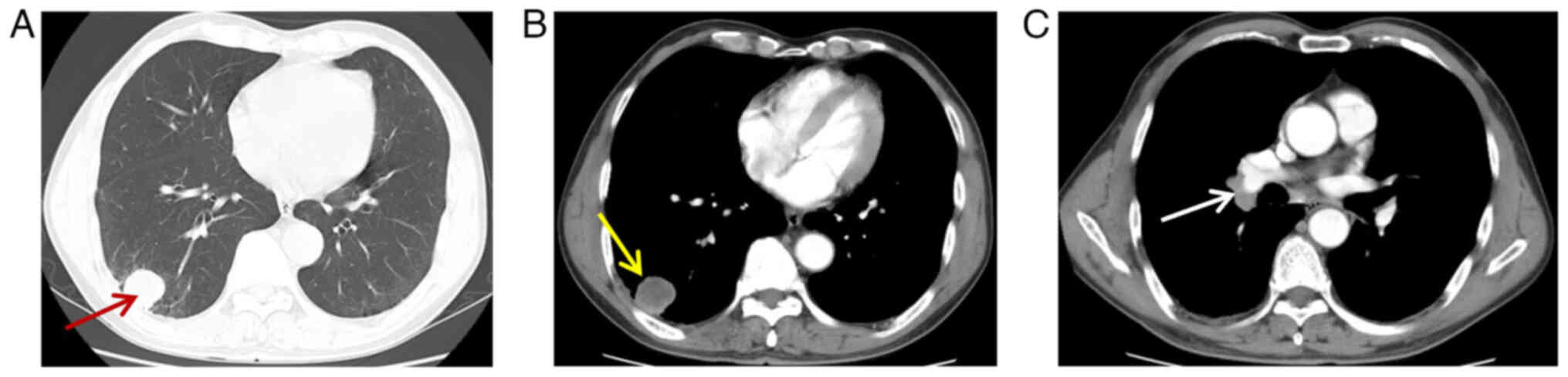

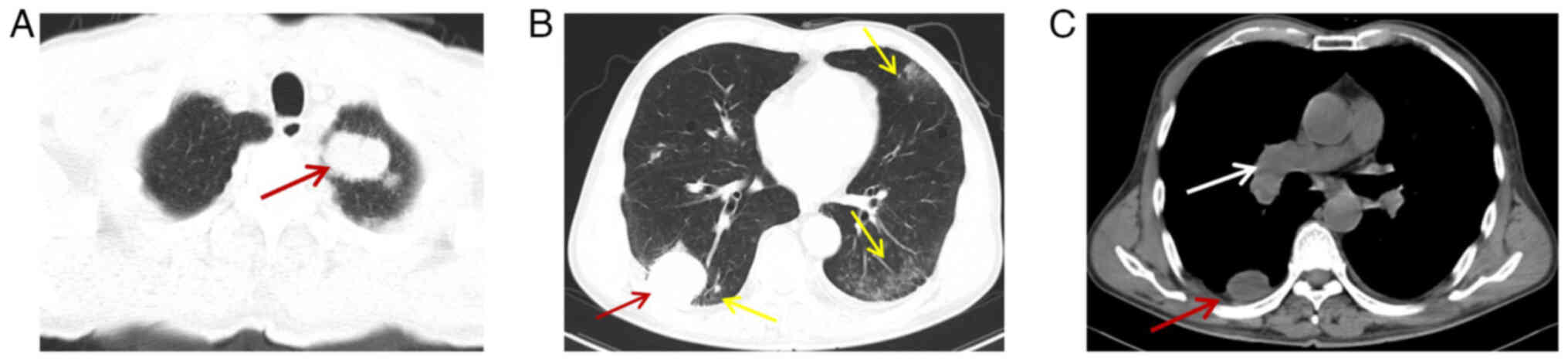

After the patient was admitted to the hospital, a

biochemical examination was conducted (Table I). Results of the examination

demonstrated carcinoembryonic antigen levels of 22.81 ng/ml

(reference value, 0–4.5 ng/ml), indicative of a malignant

neoplastic lesion. The medical team conducted a chest CT (Optima

CT660, GE HealthCare; 5-mm-layer-thickness; helical scanning;

Table II) with plain scanning and

enhancement examination. Results of the CT examination revealed

multiple nodules and masses in both lungs, with the largest mass

located in the right lower lobe of the lung in the outer basal

segment. The mass exhibited a diameter of ~31 mm, with an average

CT value of 19 Hounsfiled unit (HU), clear borders and smooth edges

(Fig. 1A). There was no notable

enhancement in the central area of the lesion on enhanced scanning

(double-phase enhancement CT values of 20 HU and 21 HU,

respectively), with circumferential enhancement around the edges

(Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the lymph

node in the right hilar region of the right lung was enlarged

(Fig. 1C), with a maximal short

diameter of ~15 mm. An abdominal CT scan (Optima CT660, Cytiva;

5-mm layer thickness; spiral scan) and enhanced examination

revealed multiple hypodense nodules in the liver, with the largest

nodule observed in the hepatic segment VIII (Fig. 2A). This nodule exhibited a diameter

of ~12 mm, a CT value of 20 HU on scanning and enhanced scans of 30

HU, 35 HU and 39 HU in hepatic arterial, portal and delayed phases,

respectively. A brain CT was also performed and indicated no

evidence of metastasis, hemorrhage or infarction.

| Table I.General examination and laboratory

test results on admission. |

Table I.

General examination and laboratory

test results on admission.

| A, General clinical

examination |

|---|

|

|---|

| Parameter | Value | Reference

range |

|---|

| Body temperature,

°C | 36.6 | 36.3-37.2 |

| Heart rate, beats

per min | 82 | 60-100 |

| Respiratory rate,

breaths per min | 18 | 15-20 |

| Blood pressure,

mmHg | 130/82 | 90/60-120/80 |

|

| B, ABG

analysis |

|

|

Parameter | Value | Reference

range |

|

| pCO2,

mmHg | 36.00 | 35-45 |

| pO2,

mmHg | 86.00 | 80-100 |

| HCO3,

mmol/l | 24.50 | 18-23 |

| TCO2,

mmol/l | 25.60 | 22-28 |

| SO2C,

% | 97.00 | 95-98 |

| A-aDO2,

mmHg | 20.00 | 15 |

| BE, mmol/l | 0.30 | −2-3 |

|

| C, Tumor marker

assays |

|

|

Parameter | Value | Reference

range |

|

| CEA, µg/l | 22.81 | 0-10 |

| CA125, U/ml | 28.62 | 0-35 |

| CA19-9, U/ml | 26.88 | 0-27 |

| CA72-4, U/ml | 2.97 | 0-6.9 |

| AFP, ng/ml | 1.85 | 0-20 |

|

| D, Pathogen

detection |

|

| G test,

pg/ml | 32.53 | <60 |

|

| CP-DNA test | Negative | Negative |

| MP-DNA test | Negative | Negative |

| GM ratio | 0.21 | <0.5 |

| Fungal smear

test | Negative | Negative |

| Table II.Summary of patient radiological

examination results. |

Table II.

Summary of patient radiological

examination results.

| Day | Radiological

examination | Results |

|---|

| Day 1 | Chest CT | Multiple nodules

and masses found in both lungs, enlargement of right hilar lymph

node in right lung |

|

| Abdominal CT | Multiple

low-density nodules in the liver, with larger nodules located in

segment VIII of the liver |

| Day 18 | Abdominal CT | Enlarged liver

metastases, new metastases in the spleen, intussusception in the

jejunal segment of the small intestine, intestinal obstruction |

| Day 31 | Chest CT | Enlarged lesions in

both lungs with new ground-glass shadows in the dorsal aspect of

both lungs |

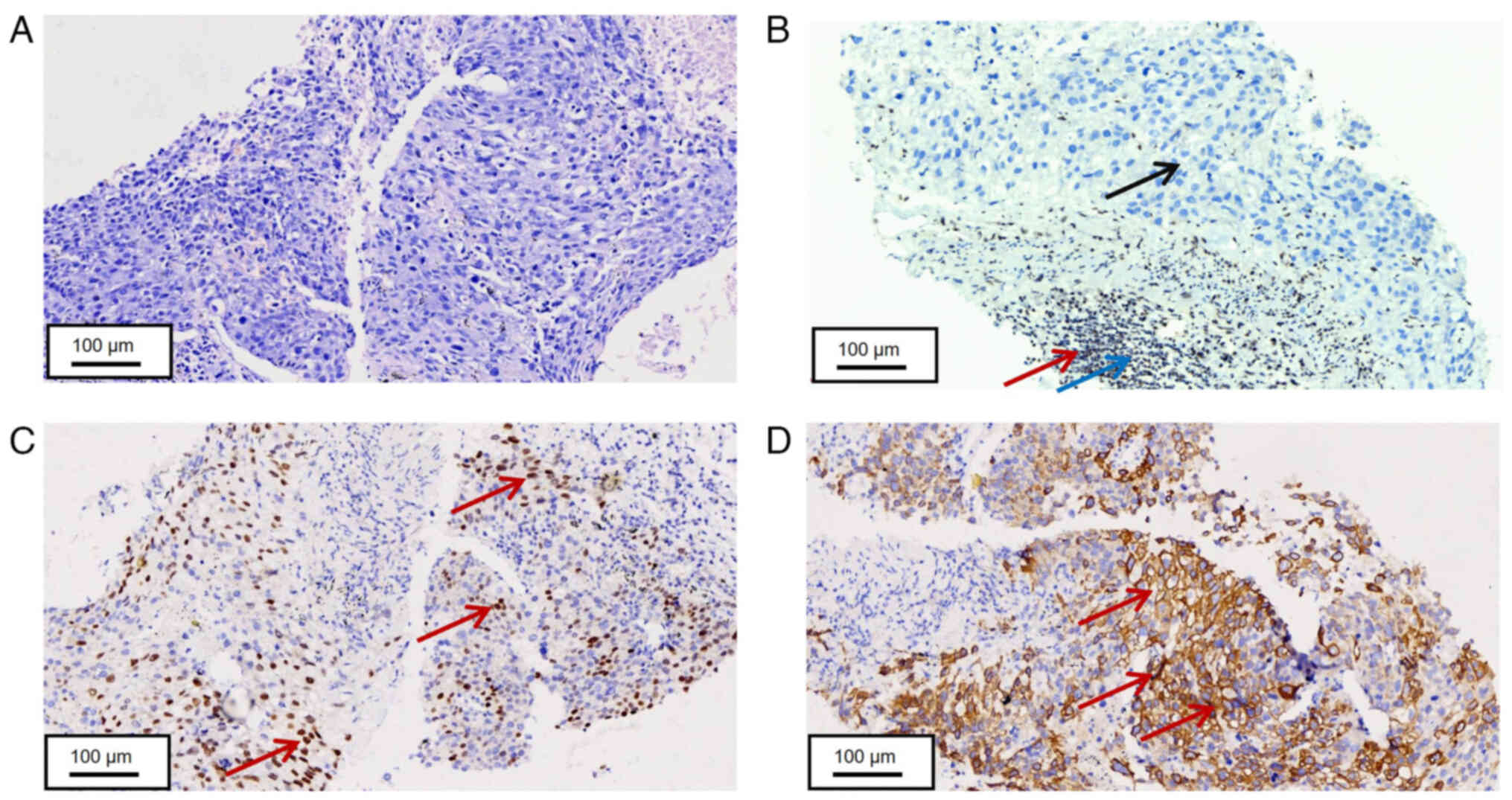

The clinical history of the patient, imaging and

laboratory findings were suggestive of a malignant neoplastic

lesion. On day 6, the patient underwent a puncture biopsy of a mass

in the extramedullary segment of the lower lobe of the right lung.

The puncture specimen was a greyish-white tissue of two strips with

a length of 0.8-1.0 cm and a diameter of 0.1 cm. The puncture

specimen was further examined using H&E staining. The tissue

sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature

for 30 min. The thickness of each section was 5 µm. Hematoxylin

staining was performed at room temperature for 7 min, followed by

eosin staining at room temperature for 1 min. The sections were

then observed under an light microscope. The fresh specimen was

dehydrated using alcohol in a room-temperature gradient, soaked in

xylene at room temperature and embedded in paraffin at 65°C.

Subsequently, the pathological tissue was cut into 5-µm slices and

soaked in room temperature xylene, anhydrous ethanol, 95% ethanol,

80% ethanol and H2O. The tissue sample was stained using

hematoxylin for 5 min and eosin for 1 min, followed by gradient

alcohol dehydration and neutral resin sealing. Tissue samples were

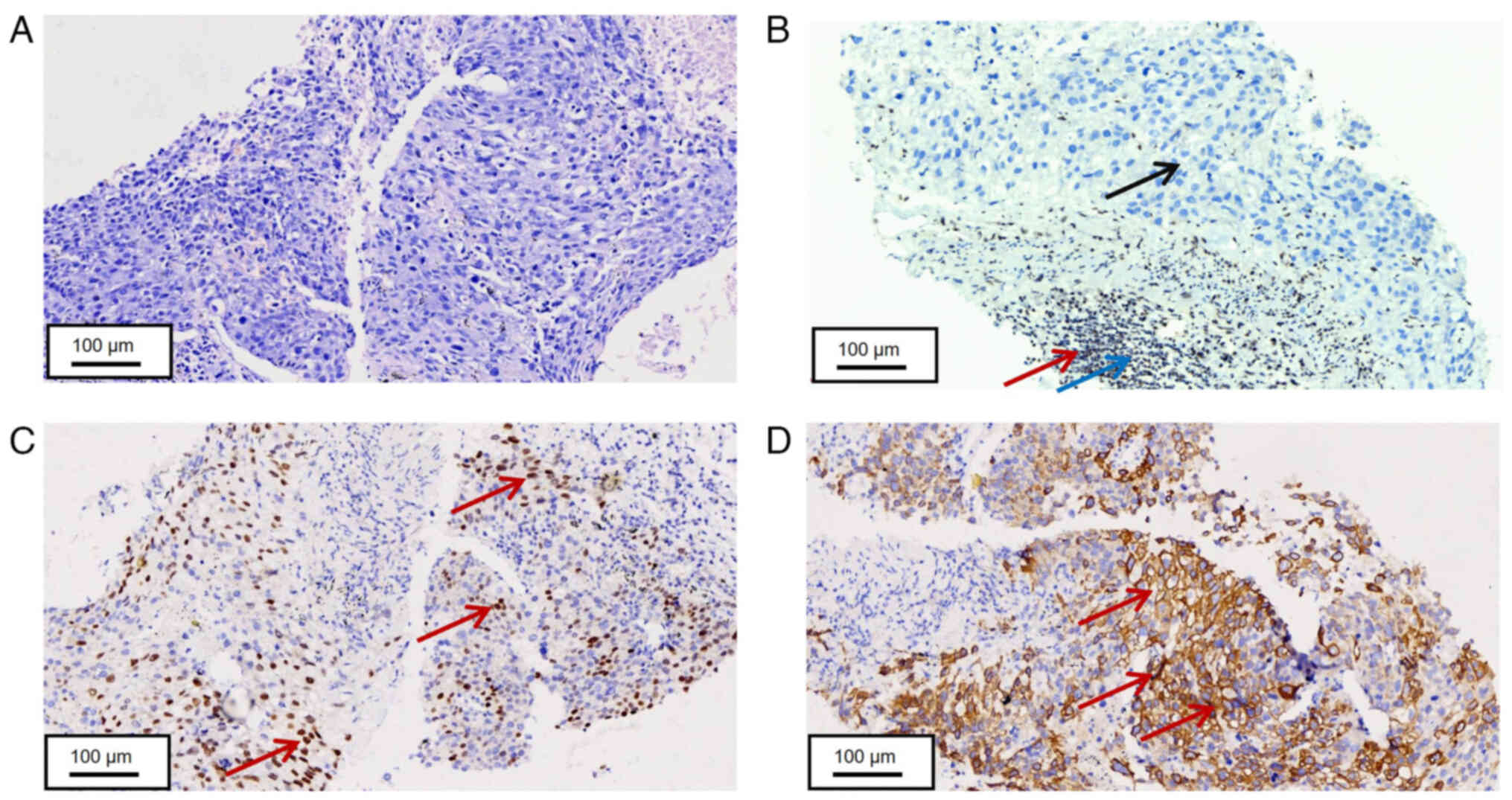

observed using a light microscope (scale bar, 200 µm). The tumor

cells in the punctured tissue of the patient were diffusely

distributed in the form of sheet nests. Furthermore, the tumor

cells exhibited unclear borders, the cytoplasm was weakly

basophilic or translucent, the nuclei were ovoid or short

spindle-shaped, the frequent mitotic figures was irregular and

small nucleoli were partially visible. Mitotic figures and a high

amount of necrosis were observed (Fig.

3A). Histopathological staining of the patient tissue sample

revealed negative expression of tumor markers for colorectal or

lung cancer, though there is focal expression of squamous cell

carcinoma markers. The tissue samples were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, and serial

sections were cut at a thickness of 5 µm. After blocking, the

sections were incubated with the primary antibody at 37°C for 30

min, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody at room

temperature for 8 min. To visualize the nuclei, the sections were

treated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogenic solution for 8 min

at room temperature and then counterstained with hematoxylin for 7

min at room temperature. Finally, the stained sections were

examined under a light microscope. However, the specific origin of

the tumor cannot be determined based solely on these findings.

Therefore, clinical manifestations must be taken into account. The

patient was admitted due to hematochezia and was found to have a

positive fecal occult blood test. No pulmonary symptoms were

observed. Imaging studies demonstrated tumors in the lungs and

liver, which were peripherally located and well-defined, which

suggested a higher possibility of metastatic tumors. Additionally,

the mass causing intussusception had already invaded the muscular

layer of the small intestine. Combining these clinical findings, it

was concluded that the systemic tumors in the patient most likely

originated from the small intestine.

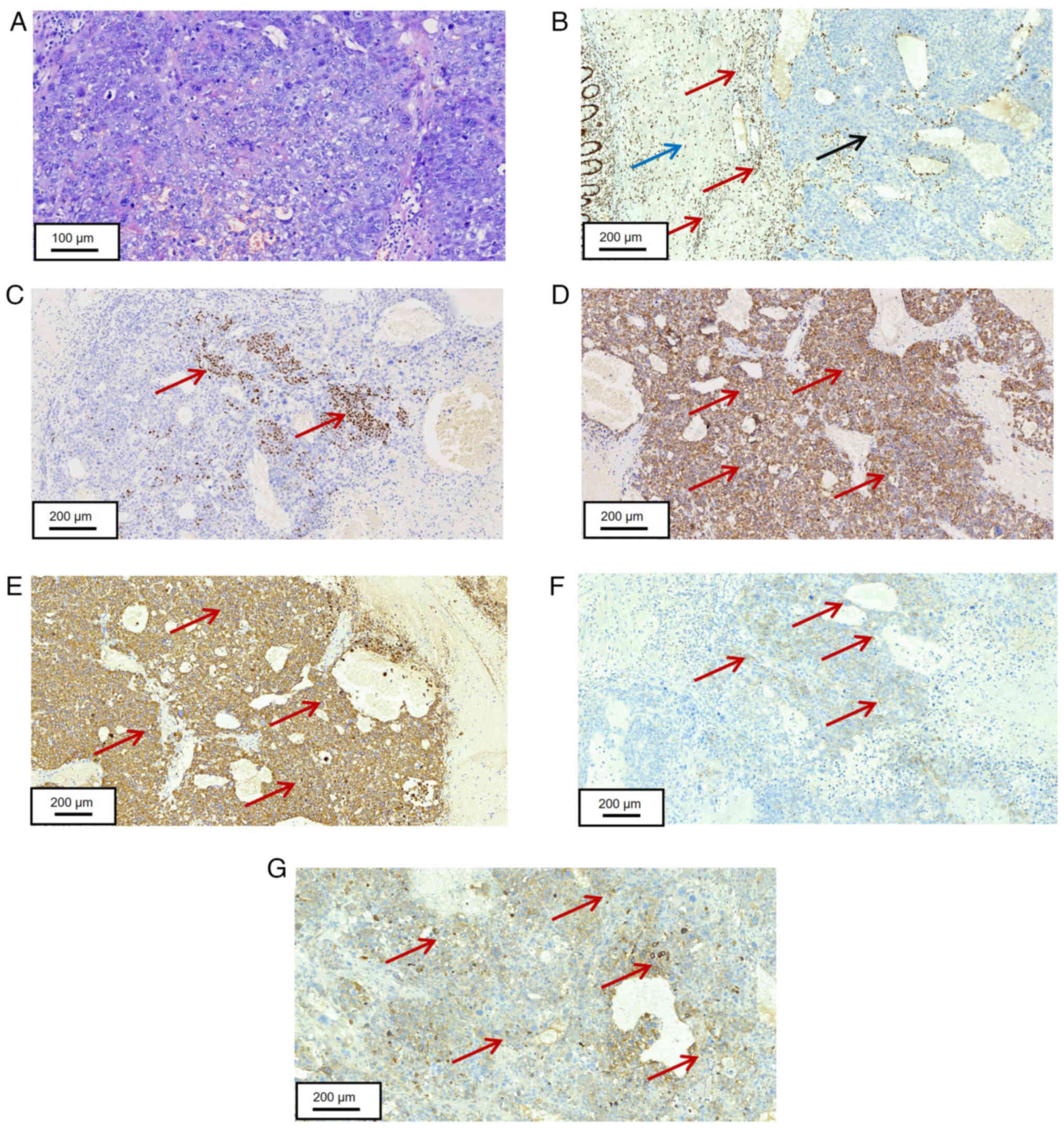

| Figure 3.Histopathological staining of lung

biopsy tissue. (A) Tumor cells in lung biopsy tissue were arranged

in solid sheets, with some cells exhibiting visible nucleoli

following H&E staining (scale bar, 100 µm). (B) Tumor cells

obtained from the lung biopsy tissue revealed negative expression

of SMARCA4 (Red arrows indicate SMARCA4-positive sites, blue arrows

indicate lymphoid regions, black arrows indicate tumor regions,

scale bar, 100 µm). (C) Partial positive expression of p40 in tumor

cells obtained from the lung biopsy tissue (Red arrows indicate

p40-positive sites, scale bar, 100 µm). (D) Positive expression of

CK7 in tumor cells obtained from the lung biopsy tissue (red arrows

indicate CK7-positive sites, scale bar, 100 µm). SMARCA4,

switch/sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) related matrix associated

actin-dependent regulator of chromatin sub-family A member 4; CK,

cytokeratin. |

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using

Benchmark GX (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). The tissue samples were

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min,

after which they were embedded in paraffin wax. Permeabilization

was performed by treating the sections with 0.1% Triton X-100 at

room temperature for 15 min. Each section was cut to a thickness of

5 µm. EDTA (pH, 8) was used for antigen repair and repair

parameters were set at 100°C for 30 min, according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Endogenous catalase was blocked using 3%

hydrogen peroxide for 5 min at room temperature. Tumor tissues were

incubated with monoclonal antibodies against thyroid transcription

factor-1 (TTF-1), NapsinA, cytokeratin (CK)5/6, synaptophysin

(Syn), CK7, p40 and SMARCA4 at 37°C for 30 min. Following primary

incubation, samples were incubated with the HRP-labeled secondary

antibodies (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) for 8 min at room temperature.

Subsequently, the nuclei were visualized using

3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogenic solution for 8 min at room

temperature and stained using hematoxylin for 7 min at room

temperature (Table III).

| Table III.Sources of reagents for patient

testing. |

Table III.

Sources of reagents for patient

testing.

| Reagent or

medicine | Manufacturer | Cat. no. | Dilution |

|---|

| EGFR-KRAS-ALK gene

mutation combination test kit | Shenzhen Huada Gene

Technology Co Ltd | RM0914 | Not applicable |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG

H&L (HRP) | Roche Diagnostics

GmbH | 760-500 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human NUT | Guangzhou Anbiping

Medical Technology | IR429 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

TTF-1 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0677 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

CK5/6 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0774 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human Syn | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0742 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

Villin | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0540 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

CK20 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0834 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

CDX2 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-1056 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

CD34 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-1076 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human CgA | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0707 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

INSMI | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-1017 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

MelanA | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-1033 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

S-100 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | Kit-0007 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

Myogenin | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0362 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

CD30 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0023 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human CK7 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0828 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human CK8 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-1002 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human p40 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | RMA-0815 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

CD56 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0743 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

SMARCA4 | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-1016 | 1:1 |

| Anti-human

NapsinA | Fuzhou Maixin

Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. | MAB-0704 | 1:1 |

Results of the present study demonstrated that the

tumor tissues obtained from the patient were negative for TTF-1,

NapsinA, CK5/6 and Syn, positive for CK7, partially positive for

p40 and negative for SMARCA4 (Fig.

3B-D; Table IV). The specimen

was pathologically examined and used the 7th edition American Joint

Committee on Cancer staging system for small bowel cancer (11). The tumor of the patient was stage

IV, T2NXM1. The NX staging was due to insufficient peritumoral

lymph nodes sampled during surgery. However, with distant

metastasis (M1), all T and N categories default to stage IV

(12). Results of the pathological

analysis demonstrated a SMARCA4-DUC with localized squamous

carcinoma expression (Table IV).

Given the low incidence of small intestine cancer and the lack of

specific clinical guidelines, the guidelines for gastrointestinal

tumors were referred to, which indicated that programmed cell death

protein-1 (PD-1) therapy as the first-line treatment for advanced

patients with SMARCA4-DUC (13).

Additionally, previous studies have reported that SMARCA4

deficiency can lead to resistance to platinum-based and other

traditional chemotherapeutic drugs (9,10,14).

Therefore, PD-1 therapy was chosen as the primary treatment without

employing a combination therapy regimen. Tislelizumab (200 mg,

intravenous; cat. no. BGB-A317; BeOne Medicines) was intravenously

administered to the patient in the clinic on day 11. Paclitaxel and

nedaplatin were suggested for the patient on day 13 but not

administered due to bleeding that occurred in the patient. The

patient was passing tarry stools; thus, a follow-up blood test was

performed. The results demonstrated hemoglobin levels of 57 g/l

(healthy range, 130–175 g/l). Gastrointestinal bleeding was

considered, chemotherapy was stopped and fasting, blood transfusion

(4 units) and nutritional support were advised. However, the

patient did not agree to the test because the results of the

immunotherapy did not meet the expectations of the patient and they

were not willing to continue with the immunotherapy.

| Table IV.Summary of patient IHC results. |

Table IV.

Summary of patient IHC results.

| Name | pH | Incubation time,

min | IHC result |

|---|

| NUT | 8 | 32 | - |

| TTF-1 | 8 | 32 | - |

| CD5/6 | 8 | 32 | - |

| Syn | 8 | 32 | - |

| Villin | 8 | 32 | - |

| CDX2 | 8 | 32 | - |

| CD34 | 8 | 32 | - |

| CgA | 8 | 32 | - |

| INSM1 | 8 | 32 | - |

| Myogenin | 8 | 32 | - |

| CD30 | 8 | 32 | - |

| CK7 | 8 | 32 | + |

| p40 | 8 | 32 | + |

| CD56 | 8 | 32 | + |

| SMARCA4 | 8 | 32 | - |

| NapsinA | 8 | 32 | - |

| MelanA | 8 | 28 | - |

| S-100 | 8 | 24 | - |

| CK8 | 8 | 24 | + |

| CD20 | 8 | 24 | - |

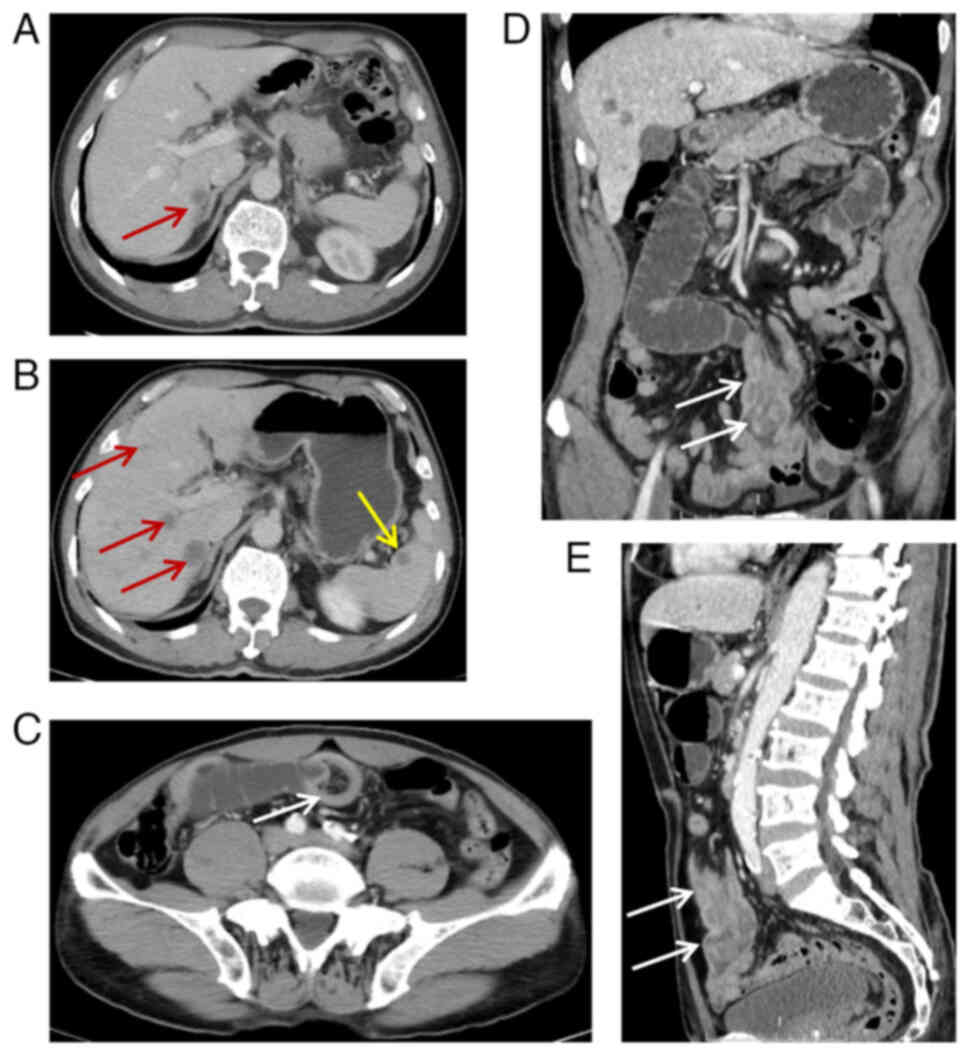

On day 18, the patient had not passed gas for 1 day.

A complete abdominal CT examination and enhanced examination

(Optima CT660, Cytiva; 5-mm layer thickness; helical scan) revealed

increased and enlarged liver metastases, novel metastases in the

spleen, intestinal intussusception in the jejunal segment of the

small intestine and intestinal obstruction (Fig. 2B-E). On day 20, a laparoscopic

partial resection of the small intestine was performed and observed

a resected small intestinal specimen of 8 cm in length in the lumen

of the lassoed area. A red elevated area was observed in the

intestinal lumen of the intestinal trocar, measuring 3.5×2.5×1.5

cm. This area exhibited an ulcerated vesiculated surface and the

cut surface was grayish-white and grayish-red with a moderate solid

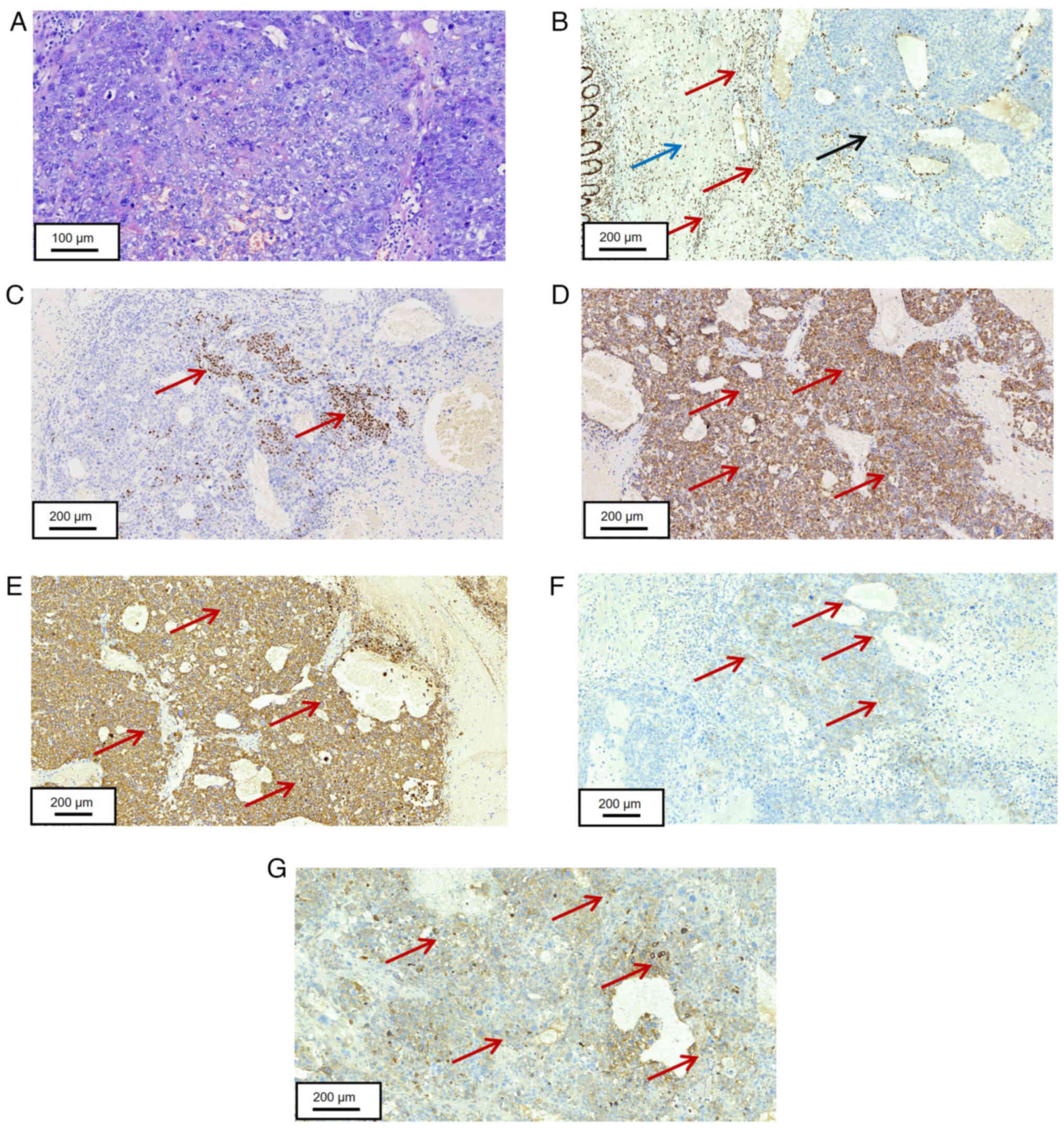

texture. H&E staining was performed using the previously

described protocol and light microscopy revealed that the tumor

cells were diffusely distributed in nests of sheets. In addition,

the tumor cells were large with unclear borders, weakly basophilic

or translucent cytoplasm and large, rounded or oval nuclei with

pronounced nuclear membranes. Multiple small nucleoli were observed

and nuclear schizophrenia was readily visible. There were numerous

hemorrhagic necroses within the lesion and small blood vessels in

the tumor interstitium were hyperplastic and partially dilated with

bruising (Fig. 4A).

Immunohistochemistry demonstrated lack of expression for TTF-1,

CK5/6, Syn, PSA, villin, CK20, caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX-2),

CD34, Syn, CgA, insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1), melanoma

antigen (MelanA), S100, myogenin, leukocyte common antigen and

CD30, and positive expression for CK7 and CK8. There were small

foci of p40 positive expression, partial positive expression of

glypican-3 and CD56, and lack of expression of SMARCA4 and nuclear

protein in the testis (Fig. 4B-D;

Table V). Small intestinal tumor

samples obtained from the patient were investigated for 50 genes

associated with lung cancer and 23 genes associated with intestinal

cancer using next-generation sequencing (NGS). High-throughput

sequencing was conducted on the MGISEQ-2000 platform. DNA libraries

were constructed with the EGFR-KRAS-ALK Gene Mutation Combination

Test kit (Cat. No. RM0914, Shenzhen Huada Gene Technology Co.,

Ltd.) to generate 150-bp paired-end reads. Library integrity was

validated using the Qsep1™ capillary electrophoresis

system (Product No. 100001, BiOptic Inc.) with the Standard

Cartridge kit (Cat. No. C105201, BiOptic Inc.). Final library

concentrations were quantified with the Equalbit 1× dsDNA HS Assay

Kit (Cat. No. EQ121-02, Vazyme) and adjusted to 10 pM for cluster

generation. Raw sequencing data were processed and analyzed using

HALOS software (v4.1.3, Shenzhen Huada Gene Technology Co., Ltd.),

and mutations in PTEN, TP53, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM),

ephrin type-A receptor 5 (EPHA5) and EGFR p.F997L were observed

(Table SI). The raw sequence data

reported in the present case report have been deposited in the

Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) in the National Genomics Data Center,

China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of

Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA-Human database;

accession no. HRA011751) that are publicly accessible at GSA for

Human (ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA011751) (15,16).

The genes tested include both those recommended for testing by Food

and Drug Administration, National Medical Products Administration

and National Comprehensive Cancer Network authoritative guidelines

and key genes associated with drug targets during clinical trials

and the development of diseases (17–27).

Pan-cancer studies have linked SMARCA4/PTEN loss to DNA repair

defects that may underlie the TP53, ATM, EPHA5 and EGFR mutations,

as unrepaired DNA damage can trigger oncogenic mutations (28–30).

Thus, the clinical features, imaging manifestations and

pathological features were indicative of undifferentiated carcinoma

with localized squamous carcinoma expression and intussusception in

SMARCA4-deficient small intestine, with metastasis to the lung,

liver and spleen. Although these mutations were detected, the

treatment plan could not be adjusted and optimized based on them

due to the rapid progression of the condition of the patient.

| Figure 4.Histopathological staining of tumor

tissue in the small intestine. (A) Tumor cells in the small

intestine were arranged in solid nests, with large, lightly stained

nuclei and one or more visible small nucleoli (scale bar, 100 µm).

(B) Negative SMARCA4 expression in tumor cells of the small

intestine (red arrows indicate SMARCA4-positive sites, blue arrows

indicate lymphoid regions, black arrows indicate tumor regions,

scale bar, 200 µm). (C) Partial positive expression of p40 in tumor

cells of the small intestine (red arrows indicate p40-positive

sites, scale bar, 200 µm). (D) Positive expression of CK7 in tumor

cells of the small intestine (Red arrows indicate CK7-positive

sites, scale bar, 200 µm). (E) Positive expression of CK8 in tumor

cells of lung biopsy tissue (Red arrows indicate CK8-positive

sites, scale bar, 200 µm). (F) Positive expression of CD56 in tumor

cells of lung biopsy tissue (red arrows indicate CD56-positive

sites, scale bar, 200 µm). (G) Positive expression of GPC-3 in

tumor cells of lung biopsy tissue (red arrows indicate

GPC-3-positive sites, scale bar, 200 µm). SMARCA4, switch/sucrose

non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) related matrix associated actin-dependent

regulator of chromatin sub-family A member 4; CK, cytokeratin;

GPC-3, glypican-3. |

| Table V.Immunohistochemistry of tumor tissues

from different sites in patients. |

Table V.

Immunohistochemistry of tumor tissues

from different sites in patients.

|

| Lung tumor | Small bowel

tumor |

|---|

| CK5/6 | - | - |

| p40 | + | + |

| CK7 | + | + |

| TTF-1 | - | - |

| NapsinA | - | Untested |

| Syn | - | Untested |

| CK8 | Untested | + |

| Villin | Untested | - |

On day 31, a CT examination of the chest was

performed. The patient exhibited enlarged and increased lesions in

both lungs (Fig. 5A-C) and new

ground-glass shadows in the dorsal aspect of both lungs, with no

evidence of infection, the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid

Tumors (RECIST) score was disease progression (31). Furthermore, immune-associated

pneumonia-non-specific interstitial pneumonitis was considered

(Fig. 5B) (32). Multiple new lesions were observed on

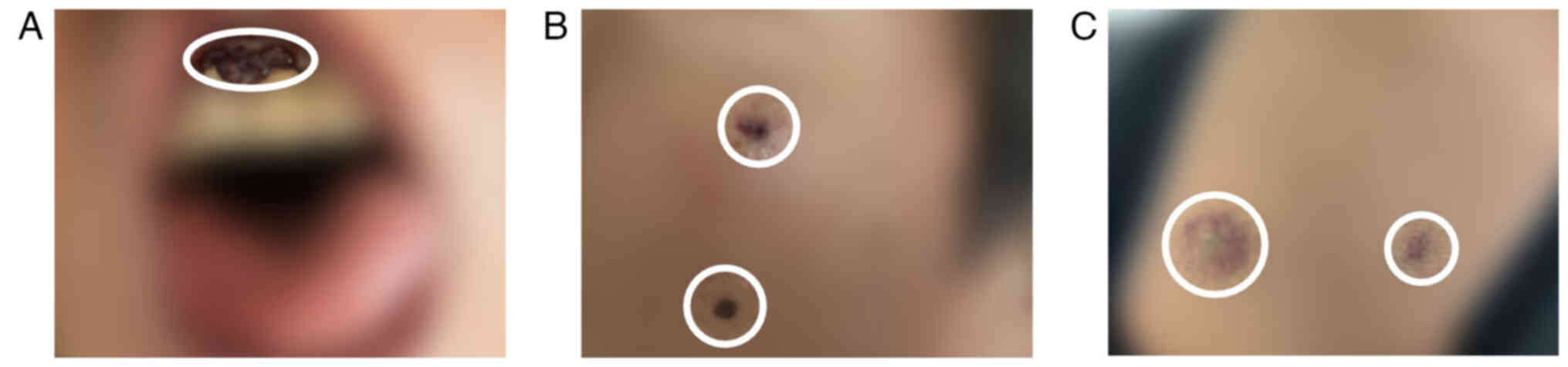

the skin and gingiva, indicative of metastasis (Fig. 6A-C). The patient presented with

persistent symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding and a decrease in

hemoglobin levels (69 g/l) and was therefore administered 9 units

of erythrocyte transfusions and posterior pituitary hormones (a

dilute acetic acid sterilized aqueous solution of posterior

pituitary powder containing posterior pituitary hormone) for

hemostasis (2 ml intravenously once daily), and was provided with

nutritional support. The family of the patient requested that the

patient be discharged from the hospital on day 42 and the patient

was discharged on the same day. Within 24 h of discharge, the

patient succumbed to the disease. The complete timeline is shown in

Fig. 7.

Discussion

The SMARCA4 gene subgroup belongs to the SWI/SNF

family, which serve a key role in chromatin remodeling and repair.

Results from previous studies demonstrated that SMARCA4 serves a

key role in developmental processes, transcriptional regulation,

DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, tumorigenesis and tumor

development. Furthermore, inactivating mutations in SMARCA4 lead to

a loss of protein expression in the nucleus, which result in

malignancies associated with SMARCA defects (33,34).

In non-small cell lung cancer, mutations in the SMARCA4 gene occur

in ~10% of cases. Notably, these mutations have been reported in

malignant tumors in alternative sites, including the ovaries,

esophagus, stomach, uterus and liver; however, the majority of

previous studies were case reports (35–39).

SMARCA4-DUC is a rare yet highly malignant tumor

that is aggressive and associated with poor prognosis (Table VI). Cases of SMARCA4-DUC in the

gastrointestinal tract predominantly affects elderly men and the

common sites of development include the stomach, colon, small

intestine and lower esophageal cardia, with few cases affecting the

ileum, rectum and pancreas (40,41).

In a study by Wang et al (42), it was noted that lung cancer cells

undergo SMARCA4 loss, which results in a reduced response to

anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which may be associated with a notable

reduction in the infiltration of dendritic cells and

CD4+ T cells into the tumor microenvironment (TME);

however, this study focused on cellular and animal experiments. The

results of previous studies examining the impact of SMARCA4 loss on

the response to PD-1 immunotherapy in lung cancer are conflicting

and these discrepancies may be associated with differences in study

models. As noted in a study of advanced undifferentiated carcinoma

of the duodenum, PD-1 therapy is effective in some patients with

SMARCA4 deficiency, which potentially provides an option for the

treatment of these highly malignant tumors (43). A clinical study reported that

partial SMARCA4 deletion may make patients with lung cancer more

sensitive to PD-1 monoclonal antibody drugs (27). However, this study primarily

included an animal model for its experiments and the underlying

mechanisms may be more complex in humans. Tumors are often located

within the muscular wall of the digestive tract and involve the

mucosa and may also form masses outside of the wall of the

digestive tract (38,44–47).

Few characteristic imaging features of SMARCA4-DUC lead to

complexities in diagnosis; however, the majority of these tumors

exhibit notable signs of malignancy, such as large foci that are

lobulated, which encircle blood vessels, invade adjacent tissues

and metastasis to mediastinal lymph nodes and distant organs

(5). In the present case, a chest

CT examination demonstrated multiple nodules and masses with clear

borders and smooth edges and enhanced CT examination demonstrated

that the majority of areas in the lesions did not exhibit notable

enhancement. Furthermore, the edges of the lesions were notably

enhanced, which was consistent with the manifestation of

bloodstream metastasis in both lungs. Enhanced abdominal CT

examination revealed localized condensation of the jejunal segment

of the small intestine, with edema and thickening of the tube wall.

In addition, multiple nodules in the liver and spleen were

observed, with moderate bulls-eye enhancement observed through

enhanced examination. These findings were consistent with the

manifestation of hematogenous metastasis in the liver and spleen.

The imaging manifestations of bilateral lung, liver and spleen

metastases were consistent with those reported in previous

literature (48–50); however, to the best of our

knowledge, the present study is the first to report the case of

intestinal intussusception caused by SMARCA4-DUC in the small

intestine.

| Table VI.Summary of key findings on SMARCA4

loss in various malignancies. |

Table VI.

Summary of key findings on SMARCA4

loss in various malignancies.

| First author,

year | Type of cancer | Key finding | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Witkowski et

al, 2023 | Ovarian | Associated with

tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis. | (35) |

| Yu et al,

2024 | Esophageal | Led to reduced

sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs. | (55) |

| Yu et al,

2024 | Gastric | Associated with

tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis. | (55) |

| Affandi et

al, 2018 | Endometrial | Associated with

tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis. | (57) |

| Garcia-Porrero

et al, 2024 | Liver | Associated with

tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis. | (58) |

| Xue et al,

2021; | Non-small cell | Reduced sensitivity

to chemotherapeutic drugs; activated | (9) |

| Kim et al,

2021 | lung cancer | EMT process and

enhanced tumor invasiveness | (10) |

The histology of SMARCA4-DUC is characterized by

rounded cells and epithelioid cell structures arranged in sheets,

nests or beams within the tumor tissue, which may be accompanied by

a loss of adherent growth. Furthermore, rhabdoid morphology, which

is defined as the presence of cells with large, eosinophilic

cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli and a vesicular chromatin pattern is

seen in focal areas in ~2/3 of the cases (34). Results from previous studies

revealed that tumor cells are often uniform. However, tumor cells

that were pleomorphic, contained spindle cell components or

exhibited pseudoadenoids or pseudoglandular structures were

observed in some cases (5,51). A previous study demonstrated that

undifferentiated carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract often

possess multifarious rhabdomyolysis features, accompanied by

deletion of SMARCB1, SMARCA2, SMARCA4 and AT-rich interaction

domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) (41). Notably, a deletion in SMARCA4 is

often present in conjunction with a deletion in SMARCA2, which

affects ~39.9% of cases. These deletions are often accompanied by

negative or reduced expression (<10% positivity) of epithelial

markers, including CKpan, CK7, CK20 and CDX2. In addition to

epithelial markers, tumor cell markers, such as Sox2, spalt-like

protein 4, p53, ARID1A and neuroendocrine markers, such as CgA,

Syn, CD56 and INSM1, may also be expressed to varying degrees in

SMARCA4-DUC (46,52–54).

In a previous study (36), it was

noted that SMARCA4 deletion and TP53 have similar mutation rates in

gastrointestinal tumors and that this mutation seems to occur more

often in the esophagus compared with the stomach or elsewhere,

which suggests a possible location of origin for gastrointestinal

tumors. The patient from the present case also demonstrated focal

expression of p40; however, SMARCA4 deletion was detected in small

bowel cancer in a study on SMARCA4 deletion in lung cancer, which

indicated that tumors with deletion of SMARCA4 were mostly

non-squamous cell carcinomas and the expression of p40 was mostly

negative or weakly positive at the focal level (34). This is similar to the expression of

p40 detected in the patient in the present case. Considering the

DNA repair function of SMARCA4, SMARCA4 deletion may lead to a

variety of morphological and immunophenotypic features of tumor

cells during differentiation and the focal expression of p40 may

reflect the partial squamous differentiation tendency of the

associated tumor cells (55).

According to previous studies, diffuse strong positivity of p40

expression in tumor tissue can be used to diagnose squamous cell

carcinoma. However, the present tumor tissue showed focal p40

expression, which did not meet the diagnostic criteria. Therefore,

the patient's treatment plan was based on the criteria for

undifferentiated carcinoma (56,57).

During clinical diagnosis, a combination of

histological and molecular pathological analyses is required to

distinguish SMARCA4-DUC from large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas

with rhabdomyosiform morphology, often accompanied by diffuse or

strong positive expression of neuroendocrine markers (58,59).

Notably, melanomas with rhabdomyosiform morphology often express

melanocyte markers, such as S100, MelanA and human melanoma

black-45 (60,61). Rhabdomyosarcoma with distinctive

rhabdomyosarcoma-like features often express muscle-specific

markers, such as myogenic differentiation antigen 1 and myogenin

(62,63). Cases of primary interstitial

large-cell lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract often include

large cells with a pronounced nucleolus and these may exhibit high

levels of expression of lymphocyte markers, such as CD30 and ALK

(64,65). Furthermore, proximal-type

epithelioid sarcoma with epithelioid morphology often express

epithelioid markers, such as CK and epithelial membrane antigen

(66,67), which aid in identification and

differentiation.

Genomic analysis of SMARCA4-DUC demonstrated that

common co-mutations included TP53, KRAS, serine/threonine kinase 11

(STK11) and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), with less

common co-mutations with common genes, such as EGFR, ROS

proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase and ALK (68,69).

The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, USA) reported that the

KRAS gene is the most commonly co-mutated gene in SMARCA4-DUC,

which accounts for 5–11% of gene mutations (70). Patients with SMARCA4-DUC often

present with a poor prognosis, with markedly shorter median

progression-free survival (4.1 vs. 1.4 months) and median overall

survival (15.1 vs. 3.0 months) compared with patients exhibiting

the SMARCA4/KRAS wild-type (71,72).

Treatment of SMARCA4-DUC is complex, due to its

unique physiological characteristics and low prevalence rates. In

addition, there are no unified treatment guidelines to follow, with

a lack of effective therapies used in clinical practice (73). Partial SMARCA4 deletion may make

patients with lung cancer more sensitive to PD-1 monoclonal

antibody drugs, which was noted in a clinical study (44). A previous case report demonstrated

that surgical resection may be an effective initial treatment

option for patients with SMARCA4-DUC with clinical staging

(74). However, the present case

report also demonstrated that 4 months following surgery, patients

with SMARCA4-DUC developed tumor recurrence with invasion to the

adjacent ribs. Results from a previous study revealed that patients

with SMARCA4-DUC may benefit from platinum-based chemotherapy and

the systemic effects of chemotherapy may control distal tumor

metastasis to some extent, due to the high aggressiveness and

metastatic nature of the disease (75). Furthermore, targeted drug therapies,

including anilotinib, sindilizumab and bevacizumab, may aid in

controlling the progression of SMARCA4-DUC (54,76).

In a previous case report, a patient with SMARCA4-DUC who developed

genetic mutations in STK11/KEAP1, KEAP1, PBRM1, SMARCA4 and STK11

received tirilizumab immunotherapy (77). However, rapid disease progression

was observed, with hepatic and pulmonary metastases within 1 month,

which ultimately led to the death of the patient. Findings from

previous studies revealed that STK11/KEAP1, KEAP1, PBRM1 and STK11

gene mutations may affect the tumor microenvironment of patients,

which weakens the tumor-killing effect of immune cells and

increases the risk of disease progression following immunotherapy

(78–80). Due to the high degree of

heterogeneity of tumor cells in patients with SMARCA4-DUC, NGS

technology is required for the development of personalized

treatment plans (81). The rapid

disease progression of the present patient after immunotherapy

suggested that there may be hyperprogression, although there is no

direct evidence that SMARCA4 may be an independent influence on

hyperprogression of immunotherapy in gastrointestinal patients. It

was noted in Han et al (82)

that environmental factors, especially the gut microbiome, can have

an impact on immunotherapy and it is possible that the

intussusception and gastrointestinal bleeding that the patient

suffered at a later stage would have led to an imbalance in the gut

microbiome, which could be an important cause of

hyperprogression.

In addition, the present patient tumor exhibited

partial squamous carcinoma and in a case report by Misra et

al (83), it was noted that

patients with SMARCA4 in the gastrointestinal tract exhibiting

focal squamous carcinoma differentiation can be resistant to a

variety of chemotherapeutic agents (cisplatin and docetaxel) and

lead to an increase in their invasiveness, which may also explain

the rapid progression of the patient in the present case (84,85).

Due to the highly heterogeneous nature of tumor cells in

SMARCA4-DUC patients, deep gene sequencing of SMARCA4-DUC patients

using NGS technology is of great importance for the development of

personalized treatment protocols, taking into account the impact of

different gene mutations on patient prognosis and the toxicity and

side effects of traditional chemotherapeutic agents (81,86).

In addition, some non-pharmacological interventions, such as

magnetic fields, exosomes, may also provide options for the

treatment of SMARCA4-DUC (87–89).

In the present case, the patient was administered tislelizumab once

following diagnosis and the disease was reassessed at 22-day

intervals. After 1 month of treatment, the symptoms of the patient

had worsened, with an increase in the number of metastatic lesions

in the lungs and liver, enlargement, novel metastases in the

spleen, the development of a CT pattern indicative of

immune-associated pneumonia-nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in

both lungs and a Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors score

of progressive disease (31).

Following intussusception surgery, gastrointestinal bleeding and

treatment for aggressive symptoms, the death of the patient

occurred after 12 days. Although the specific cause of death was

not determined via autopsy, it was considered that the highly

aggressive nature of SMARCA4-DUC, which led to multiple organ

metastasis was the main cause of death and the gastrointestinal

hemorrhage and immune-associated pneumonia caused by the

intussusception may have accelerated the deterioration of the

disease.

The present study exhibits numerous limitations. For

example, the present study included a retrospective analysis of

rare cases, with a lack of guideline support and inexperience. In

the present case, diagnosis and treatment were delayed, as it

remained unclear whether immunotherapy caused hyperprogression of

the disease. In addition, the specific cause of death in the

patient was not determined due to the absence of autopsy

confirmation.

In conclusion, the present study reported a rare

case of SMARCA4-DUC in the gastrointestinal tract, which provides a

theoretical basis for the clinical management of this disease.

SMARCA4-DUC often affects elderly male patients and imaging often

reveals large lesions, invasion of surrounding tissues and

metastasis to lymph nodes and distant organs. Definitive diagnosis

of the disease relies on pathological examination,

immunohistochemistry and molecular testing. A diagnosis of

SMARCA4-DUC should be considered following the observation of solid

high-grade undifferentiated morphology of cells and negative

expression of genes used for conventional staging. Thus,

appropriate immunohistochemical and molecular tests should be

carried out to aid in early diagnosis and effective treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Weifang Municipal Health

Commission Scientific Research Program (grant nos. WFWSJK-2022-090,

WFWSJK-2022-150 and WFWSJK-2024-200).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The raw sequence data

generated in the present study may be found in the Genome Sequence

Archive (GSA) (14) in National

Genomics Data Center (15), China

National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, under accession number (accession no.

HRA011751) or at the following URL:

ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA011751.

Authors' contributions

MQ, LL, BY, and YZ analyzed data. BY and XY designed

the study protocol. XC and SL were the primary care physicians of

the patient and developed and implemented the treatment plan. YW,

QG and ZC performed the literature review and analyzed and

interpreted the data in the paper. XY drafted the work and

critically revised intellectual content. BY and XY confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors commented on the

manuscript and agreed with the conclusions of the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present case report was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Weifang No. 2 People's Hospital (approval no.

KY2023-055-01; Weifang, China) and was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

The patient's family member provided written

informed consent for the publication of the manuscript including

any identifying images or data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

|

|

2

|

Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J,

Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA and Bray F: Global burden of 5 major

types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology.

159:335–349.e15. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhan T, Betge J, Schulte N, Dreikhausen L,

Hirth M, Li M, Weidner P, Leipertz A, Teufel A and Ebert MP:

Digestive cancers: Mechanisms, therapeutics and management. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 10:242025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis

V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F and Cree IA;

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, : The 2019 WHO

classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology.

76:182–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhu PP, Li XX, Liu JH, Du XL, Su HY and

Wang J: SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated carcinoma of the

gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathological and

immunohistochemical study of nine cases. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za

Zhi. 51:868–874. 2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

6

|

Tian Y, Xu L, Li X, Li H and Zhao M:

SMARCA4: Current status and future perspectives in non-small-cell

lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 554:2160222023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lombardi M, D'Ercole M, Midolo De Luca V,

Chiari M, Spaggiari L and Bertolaccini L: The impact of SMARCA4

loss in non-small cell lung cancer therapy. Heliyon. 11:e411282024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Shi M, Pang L, Zhou H, Mo S, Sheng J,

Zhang Y, Liu J, Sun D, Gong L, Wang J, et al: Rare

SMARCA4-deficient thoracic tumor: Insights into molecular

characterization and optimal therapeutics methods. Lung Cancer.

192:1078182024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Xue Y, Morris JL, Yang K, Fu Z, Zhu X,

Johnson F, Meehan B, Witkowski L, Yasmeen A, Golenar T, et al:

SMARCA4/2 loss inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis by

restricting IP3R3-mediated Ca2+ flux to mitochondria.

Nat Commun. 12:54042021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kim J, Jang G, Sim SH, Park IH, Kim K and

Park C: SMARCA4 depletion induces cisplatin resistance by

activating YAP1-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in

triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13:54742021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Edge SB and Compton CC: The American joint

committee on cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging

manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 17:1471–1474. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Locher C, Batumona B, Afchain P, Carrère

N, Samalin E, Cellier C, Aparicio T, Becouarn Y, Bedenne L, Michel

P, et al: Small bowel adenocarcinoma: French intergroup clinical

practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (SNFGE,

FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO). Dig Liver Dis.

50:15–19. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kelly RJ, Bever K, Chao J, Ciombor KK, Eng

C, Fakih M, Goyal L, Hubbard J, Iyer R, Kemberling HT, et al:

Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice

guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of gastrointestinal

cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 11:e0066582023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Liu H, Hong Q, Zheng S, Zhang M and Cai L:

Effective treatment strategies and key factors influencing

therapeutic efficacy in advanced SMARCA4-deficient non-small cell

lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 198:1080222024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chen T, Chen X, Zhang S, Zhu J, Tang B,

Wang A, Dong L, Zhang Z, Yu C, Sun Y, et al: The genome sequence

archive family: Toward explosive data growth and diverse data

types. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 19:578–583. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

CNCB-NGDC Members and Partners, . Database

resources of the national genomics data center, china national

center for bioinformation in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 50(D1):

D27–D38. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Saura C, Roda D, Roselló S, Oliveira M,

Macarulla T, Pérez-Fidalgo JA, Morales-Barrera R, Sanchis-García

JM, Musib L, Budha N, et al: A First-in-human phase I study of the

ATP-competitive AKT inhibitor ipatasertib demonstrates robust and

safe targeting of AKT in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Discov.

7:102–113. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK,

Henrichsen-Schnack T, Ladelund S and Nilbert M: The predictive

value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment

in metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 53:852–864. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang ZH, Gao QY and Fang JY: Loss of PTEN

expression as a predictor of resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal

therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: Evidence from

retrospective studies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 69:1647–1655.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Forster MD, Dedes KJ, Sandhu S, Frentzas

S, Kristeleit R, Ashworth A, Poole CJ, Weigelt B, Kaye SB and

Molife LR: Treatment with olaparib in a patient with PTEN-deficient

endometrioid endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 8:302–306.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Koehler K, Liebner D and Chen JL: TP53

mutational status is predictive of pazopanib response in advanced

sarcomas. Ann Oncol. 27:539–543. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chalhoub N and Baker SJ: PTEN and the

PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 4:127–150. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Milella M, Falcone I, Conciatori F, Cesta

Incani U, Del Curatolo A, Inzerilli N, Nuzzo CM, Vaccaro V, Vari S,

Cognetti F and Ciuffreda L: PTEN: Multiple functions in human

malignant tumors. Front Oncol. 5:242015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Seshacharyulu P, Ponnusamy MP, Haridas D,

Jain M, Ganti AK and Batra SK: Targeting the EGFR signaling pathway

in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 16:15–31. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sigismund S, Avanzato D and Lanzetti L:

Emerging functions of the EGFR in cancer. Mol Oncol. 12:3–20. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Bendell JC, Rodon J, Burris HA, de Jonge

M, Verweij J, Birle D, Demanse D, De Buck SS, Ru QC, Peters M, et

al: Phase I, dose-escalation study of BKM120, an oral pan-class I

PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin

Oncol. 30:282–290. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Weber J and McCormack PL: Panitumumab: In

metastatic colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS. BioDrugs.

22:403–411. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sørensen SG, Shrikhande A, Poulsgaard GA,

Christensen MH, Bertl J, Laursen BE, Hoffmann ER and Pedersen JS:

Pan-cancer association of DNA repair deficiencies with whole-genome

mutational patterns. Elife. 12:e812242023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kassem PH, Montasser IF, Mahmoud RM,

Ghorab RA, AbdelHakam DA, Fathi MESA, Wahed MAA, Mohey K, Ibrahim

M, Hadidi ME, et al: Genomic landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma

in Egyptian patients by whole exome sequencing. BMC Med Genomics.

17:2022024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Watanabe T, Semba S and Yokozaki H:

Regulation of PTEN expression by the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling

protein BRG1 in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer.

104:146–154. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Gouda MA, Janku F, Wahida A, Buschhorn L,

Schneeweiss A, Abdel Karim N, De Miguel Perez D, Del Re M, Russo A,

Curigliano G, et al: Liquid biopsy response evaluation criteria in

solid tumors (LB-RECIST). Ann Oncol. 35:267–275. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ebner L, Christodoulidis S, Stathopoulou

T, Geiser T, Stalder O, Limacher A, Heverhagen JT, Mougiakakou SG

and Christe A: Meta-analysis of the radiological and clinical

features of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) and nonspecific

interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). PLoS One. 15:e02260842020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zeng X, Yao B, Liu J, Gong GW, Liu M, Li

J, Pan HF, Li Q, Yang D, Lu P, et al: The SMARCA4R1157W

mutation facilitates chromatin remodeling and confers PRMT1/SMARCA4

inhibitors sensitivity in colorectal cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol.

7:282023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Liang X, Gao X, Wang F, Li S, Zhou Y, Guo

P, Meng Y and Lu T: Clinical characteristics and prognostic

analysis of SMARCA4-deficient non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer

Med. 12:14171–14182. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Witkowski L, Nichols KE, Jongmans M, van

Engelen N, de Krijger RR, Herrera-Mullar J, Tytgat L, Bahrami A,

Mar Fan H, Davidson AL, et al: Germline pathogenic SMARCA4 variants

in neuroblastoma. J Med Genet. 60:987–992. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Neil AJ, Zhao L, Isidro RA, Srivastava A,

Cleary JM and Dong F: SMARCA4 mutations in carcinomas of the

esophagus, esophagogastric junction, and stomach. Mod Pathol.

36:1001832023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Pors J, Devereaux KA, Hildebrandt D and

Longacre TA: Primary uterine synovial sarcoma with SMARCA4 loss.

Histopathology. 80:1135–1137. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Koyasu S, Sugimoto A, Matsubara J, Muto M

and Nakamoto Y: SMARCA4-deficient poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Clin Nucl Med. 49:688–689. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Akunuru S, James Zhai Q and Zheng Y:

Non-small cell lung cancer stem/progenitor cells are enriched in

multiple distinct phenotypic subpopulations and exhibit plasticity.

Cell Death Dis. 3:e3522012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Xu J and Chi Z: Esophageal carcinoma with

SMARCA4 mutation: A narrative review for this rare entity. Transl

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9:242024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chang B, Sheng W, Wang L, Zhu X, Tan C, Ni

S, Weng W, Huang D and Wang J: SWI/SNF complex-deficient

undifferentiated carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract:

Clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with an emphasis on variable

morphology, immune features, and the prognostic significance of

different SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 subunit deficiencies. Am J Surg

Pathol. 46:889–906. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Wang Y, Meraz IM, Qudratullah M, Kotagiri

S, Han Y, Xi Y, Wang J and Lissanu Y: SMARCA4 mutation induces

tumor cell-intrinsic defects in enhancer landscape and resistance

to immunotherapy. bioRxiv. Jun 22–2024.(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

43

|

Shi YN, Zhang XR, Ma WY, Lian J, Liu YF,

Li YF and Yang WH: PD-1 antibody in combination with chemotherapy

for the treatment of SMARCA4-deficient advanced undifferentiated

carcinoma of the duodenum: Two case reports. World J Clin Oncol.

15:456–463. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Schoenfeld AJ, Bandlamudi C, Lavery JA,

Montecalvo J, Namakydoust A, Rizvi H, Egger J, Concepcion CP, Paul

S, Arcila ME, et al: The genomic landscape of SMARCA4 alterations

and associations with outcomes in patients with lung cancer. Clin

Cancer. 26:5701–5708. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Agaimy A, Daum O, Märkl B, Lichtmannegger

I, Michal M and Hartmann A: SWI/SNF complex-deficient

undifferentiated/rhabdoid carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract:

A series of 13 cases highlighting mutually exclusive loss of

SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 and frequent co-inactivation of SMARCB1 and

SMARCA2. Am J Surg Pathol. 40:544–553. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Liu J, Song L and Wang J: Primary

SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated sarcomatoid tumor of the

gastroesophageal junction. Hum Pathol Case Rep. 22:2004322020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Wong AK, Shanahan F, Chen Y, Lian L, Ha P,

Hendricks K, Ghaffari S, Iliev D, Penn B, Woodland AM, et al: BRG1,

a component of the SWI-SNF complex, is mutated in multiple human

tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 60:6171–6177. 2000.

|

|

48

|

Ankoh K, Shinji S, Yamada T, Matsuda A,

Ohta R, Sonoda H, Hotta M, Takahashi G, Kaneya Y, Iwai T, et al: A

rapidly growing small-intestinal metastasis from lung cancer. J

Nippon Med Sch. 89:540–545. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Xu Y, Zhang B and Wang J: Gastrointestinal

stromal tumour with liver metastasis presenting as gastric cancer.

Diagnostics (Basel). 13:3762023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Altaf K, Mckernan G, Skaife P and Slawik

S: Splenic metastasis in colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol.

20:795–796. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Li X, Tian S, Shi H, Ta N, Ni X, Bai C,

Zhu Z, Chen Y, Shi D, Huang H, et al: The golden key to open

mystery boxes of SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated thoracic tumor:

Focusing immunotherapy, tumor microenvironment and epigenetic

regulation. Cancer Gene Ther. 31:687–697. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Kakkar A, Ashraf SF, Rathor A, Adhya AK,

Mani S, Sikka K and Jain D: SMARCA4/BRG1-deficient sinonasal

carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 146:1122–1130. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Nambirajan A, Singh V, Bhardwaj N, Mittal

S, Kumar S and Jain D: SMARCA4/BRG1-deficient non-small cell lung

carcinomas: A case series and review of the literature. Arch Pathol

Lab Med. 145:90–98. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zhou P, Fu Y and Wang W: Case report:

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma with SMARCA4 deficiency:

A clinicopathological report of two rare cases. Front Oncol.

13:12907172023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Yu L and Wu D: SMARCA2 and SMARCA4

participate in DNA damage repair. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed).

29:2622024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Berezowska S, Maillard M, Keyter M and

Bisig B: Pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoepithelial

carcinoma-morphology, molecular characteristics and differential

diagnosis. Histopathology. 84:32–49. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Affandi KA, Tizen NMS, Mustangin M and Zin

RRMRM: p40 immunohistochemistry is an excellent marker in primary

lung squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol Transl Med. 52:283–289.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Garcia-Porrero G, Wood F, Faria S, Kelly

PJ and McCluggage WG: ‘Aberrant’ expression of skeletal muscle

markers in neuroendocrine carcinomas: A significant diagnostic

pitfall. Virchows Arch. 485:625–629. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Vocino Trucco G, Righi L, Volante M and

Papotti M: Updates on lung neuroendocrine neoplasm classification.

Histopathology. 84:67–85. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Watter H, Milkins R, Chambers C and

O'Brien B: Melanoma with rhabdomyosarcomatous features: A potential

diagnostic pitfall. BMJ Case Rep. 16:e2564272023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Tran TAN, Linos K, de Abreu FB and Carlson

JA: Undifferentiated sarcoma as intermediate step in the

progression of malignant melanoma to rhabdomyosarcoma: Histologic,

histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular studies of a new

case of malignant melanoma with rhabdomyosarcomatous

differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 41:221–229. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Tuohy JL, Byer BJ, Royer S, Keller C,

Nagai-Singer MA, Regan DP and Seguin B: Evaluation of myogenin and

MyoD1 as immunohistochemical markers of canine rhabdomyosarcoma.

Vet Pathol. 58:516–526. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Agard H, Clark C, Massanyi E, Steele M and

McMahon D: Chemoradiotherapy-induced cytodifferentiation in

bladder/prostate rhabdomyosarcoma with genetic downregulation of

myogenin and MyoD1 gene expression: A case study and review of the

literature. Urology. 137:173–177. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Mishra P, Patra S, Srinivasan A, Padhi S,

Sable MN, Samal SC and Mohapatra S: Primary gastrointestinal

anaplastic large cell lymphoma: A critical reappraisal with a

systematic review of the world literature. J Cancer Res Ther.

17:1307–1313. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Radha S, Afroz T and Reddy R: Primary

anaplastic large cell lymphoma of caecum and ascending colon.

Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 64:168–170. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, Umeda T,

Yokoyama R and Hirohashi S: Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma: A

clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Mod Pathol. 14:655–663. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Echchaoui A, Sadrati Y, Elbir Y, Elktaibi

A, Benyachou M, Mazouz SE, Gharib NE and Abbassi A: Proximal-type

epithelioid sarcoma: A new case report and literature review. Pan

Afr Med J. 24:2382016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Quintanal-Villalonga Á, Costa E,

Wohlheiter C, Tischfield S, Redin E, Sridhar H, Funnel A, Poirier

JT, Hao Y, Kinyua D, et al: 228P SMARCA4 inactivation drives

aggressiveness in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant lung adenocarcinomas

through the induction of TGFβ signaling. ESMO Open. 9 (Suppl

3):S1028782024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

An HR, Kim HD, Ryu MH and Park YS:

SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated gastric carcinoma: A case series

and literature review. Gastric Cancer. 27:1147–1152. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Wilson BG and Roberts CWM: SWI/SNF

nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:481–492.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Liu L, Ahmed T, Petty WJ, Grant S, Ruiz J,

Lycan TW, Topaloglu U, Chou PC, Miller LD, Hawkins GA, et al:

SMARCA4 mutations in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma: A

multi-cohort analysis. Mol Oncol. 15:462–472. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Alessi JV, Ricciuti B, Spurr LF, Gupta H,

Li YY, Glass C, Nishino M, Cherniack AD, Lindsay J, Sharma B, et

al: SMARCA4 and other SWItch/sucrose nonfermentable family genomic

alterations in NSCLC: Clinicopathologic characteristics and

outcomes to immune checkpoint inhibition. J Thorac Oncol.

16:1176–1187. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Cui M, Lemmon K, Jin Z and Uboha NV:

Esophageal carcinoma with SMARCA4 mutation: Unique diagnostic

challenges. Pathol Res Pract. 248:1546922023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Yin C, Liu ZJ, He C and Yu HX: A case of

surgically treated non-metastatic SMARCA4-deficient

undifferentiated thoracic tumor: A case report and literature

review. Front Oncol. 14:13998682024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Bell EH, Chakraborty AR, Mo X, Liu Z,

Shilo K, Kirste S, Stegmaier P, McNulty M, Karachaliou N, Rosell R,

et al: SMARCA4/BRG1 is a novel prognostic biomarker predictive of

cisplatin-based chemotherapy outcomes in resected non-small cell

lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 22:2396–2404. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Dagogo-Jack I, Schrock AB, Kem M, Jessop

N, Lee J, Ali SM, Ross JS, Lennerz JK, Shaw AT and Mino-Kenudson M:

Clinicopathologic characteristics of BRG1-deficient NSCLC. J Thorac

Oncol. 15:766–776. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Naito T, Umemura S, Nakamura H, Zenke Y,

Udagawa H, Kirita K, Matsumoto S, Yoh K, Niho S, Motoi N, et al:

Successful treatment with nivolumab for SMARCA4-deficient non-small

cell lung carcinoma with a high tumor mutation burden: A case

report. Thorac Cancer. 10:1285–1288. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM,

Hellmann MD, Awad MM, Gainor JF, Schrock AB, Hartmaier RJ, Trabucco

SE, Gay L, et al: STK11/LKB1 mutations and PD-1 inhibitor

resistance in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov.

8:822–835. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Leinonen HM, Kansanen E, Pölönen P,

Heinäniemi M and Levonen AL: Dysregulation of the keap1-Nrf2

pathway in cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 43:645–649. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Gatalica Z, Xiu J, Swensen J and Vranic S:

Comprehensive analysis of cancers of unknown primary for the

biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Eur J

Cancer. 94:179–186. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Concepcion CP, Ma S, LaFave LM, Bhutkar A,

Liu M, DeAngelo LP, Kim JY, Del Priore I, Schoenfeld AJ, Miller M,

et al: Smarca4 inactivation promotes lineage-specific

transformation and early metastatic features in the lung. Cancer

Discov. 12:562–585. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Han XJ, Alu A, Xiao YN, Wei YQ and Wei XW:

Hyperprogression: A novel response pattern under immunotherapy.

Clin Transl Med. 10:e1672020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Misra S, Szeto W, Centeno L, Castillo D,

Rucker A, Rahmanuddin S and Mannan R: SMARCA4 deficient gastric

carcinoma with squamous differentiation in a young patient with

aggressive clinical course. Int J Surg Pathol. 33:1016–1021. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Bhat V, Koneru M, Knapp K, Joneja U,

Morrison J and Hong YK: Identification and treatment of SMARCA4

deficient poorly differentiated gastric carcinoma. Am Surg.

89:4987–4989. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Kido K, Nojima S, Motooka D, Nomura Y,

Kohara M, Sato K, Ohshima K, Tahara S, Kurashige M, Umeda D, et al:

Ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma cells with low SMARCA4

expression and high SMARCA2 expression contribute to platinum

resistance. J Pathol. 260:56–70. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Mokashi A and Bhatia NM: Integrated

network ethnopharmacology, molecular docking, and ADMET analysis

strategy for exploring the anti-breast cancer activity of ayurvedic

botanicals targeting the progesterone receptor. BIO Integr. 5:1–17.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Ji X, Tian X, Feng S, Zhang L, Wang J, Guo

R, Zhu Y, Yu X, Zhang Y, Du H, et al: Intermittent F-actin

perturbations by magnetic fields inhibit breast cancer metastasis.

Research (Wash DC). 6:00802023.

|

|

88

|

Guo XF, Gu SS, Wang J, Sun H, Zhang YJ, Yu

PF, Zhang JS and Jiang L: Protective effect of mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomal treatment of hippocampal neurons against

oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced injury. World J

Emerg Med. 13:46–53. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Luo Z, Mei J, Wang X, Wang R, He Z, Geffen

Y, Sun X, Zhang X, Xu J, Wan R, et al: Voluntary exercise

sensitizes cancer immunotherapy via the collagen

inhibition-orchestrated inflammatory tumor immune microenvironment.

Cell Rep. 43:1146972024. View Article : Google Scholar

|