Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) ranks as the fourth most common

cancer worldwide (1). Persistent

infection of high-risk (hr)-human papillomavirus (HPV) is the

principal cause of CC, initiating carcinogenic processes that

involve the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes

(2).

Liquid biopsy (LB) has emerged as an innovative

cancer diagnosis and prognosis approach, offering a non-invasive

alternative to traditional tissue biopsies (3). By detecting circulating tumor

components such as circulating tumor cells, cell-free DNA,

cell-free RNA and exosomes in biological fluids (blood, urine,

feces and saliva), LB has demonstrated utility in early cancer

detection, personalized treatment decisions and prognostic

assessment (3,4). In CC, LB enables the detection of

molecular alterations associated with precursor lesions and disease

progression, potentially before morphological changes are evident

(5).

Identifying molecular markers at an early stage is

crucial to improving screening strategies and clinical outcomes

(6). Among the sample types used in

this context, liquid-based cytology (LBC), which contains

exfoliated cervical cells, is widely employed for conventional

cytological screening (Pap smear) (7). Whilst it is not traditionally

considered a LB, LBC offers a minimally invasive means to collect

cellular material and has proven useful for molecular analyses

(8).

Plasma is the most utilized specimen in LB research

for detecting biomarkers in several types of cancers due to its

easy accessibility (9). Although

several studies have focused on identifying biomarkers in LBC or

blood (9,10), urine can be easily self-collected

recurrently in relatively large volumes and it has greater patient

compliance, suggesting that it could be a promising non-invasive

alternative for CC screening and monitoring (11). However, technical limitations, such

as low RNA yield, concentration variability and enzymatic

degradation, may affect its analytical performance (12,13).

Given its non-invasive nature, LB using these types of specimens

allows the detection of molecular biomarkers, such as HPV DNA

(13–15), DNA methylation (12), circulating tumor cells (16) or dysregulated microRNAs

(miRNAs/miRs) (10,11), which may indicate cervical

carcinogenesis before the progression to high-grade lesions or

invasive cancer (5).

miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that serve

essential roles in regulating gene expression at the

post-transcriptional level by inhibiting mRNA translation or

promoting mRNA degradation (17).

They are stable and easily detected in LB samples, and certain

studies have demonstrated their role in several biological pathways

in CC (18,19). miRNAs identified in LBC (10), plasma (20,21) or

urine (11) samples have been

directly associated with the diagnosis, treatment monitoring and

progression of CC and its precursor lesions. However, most studies

have explored the expression of miRNAs in a single specimen using

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (11,20,21),

which has limitations such as low throughput, amplification bias

and complex normalization steps (22). This highlights the potential of

high-throughput digital platforms, such as the NanoString

nCounter® Analysis System, which enables comprehensive

miRNA profiling without amplification. It also offers high

sensitivity, even from degraded samples, such as those obtained

from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Such technologies

simultaneously facilitate detection of multiple targets, making

them valuable for large-scale biomarker studies (22). To date, only one study has employed

NanoString technology in this context, to the best of our knowledge

(10).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to

identify the most suitable specimen for miRNA-based detection of CC

precursor lesions using NanoString nCounter technology to compare

miRNA profiles across three specimen types, LBC, plasma and urine,

from women with and without high-grade cervical intraepithelial

neoplasia (CIN).

Materials and methods

Study population and sample

collection

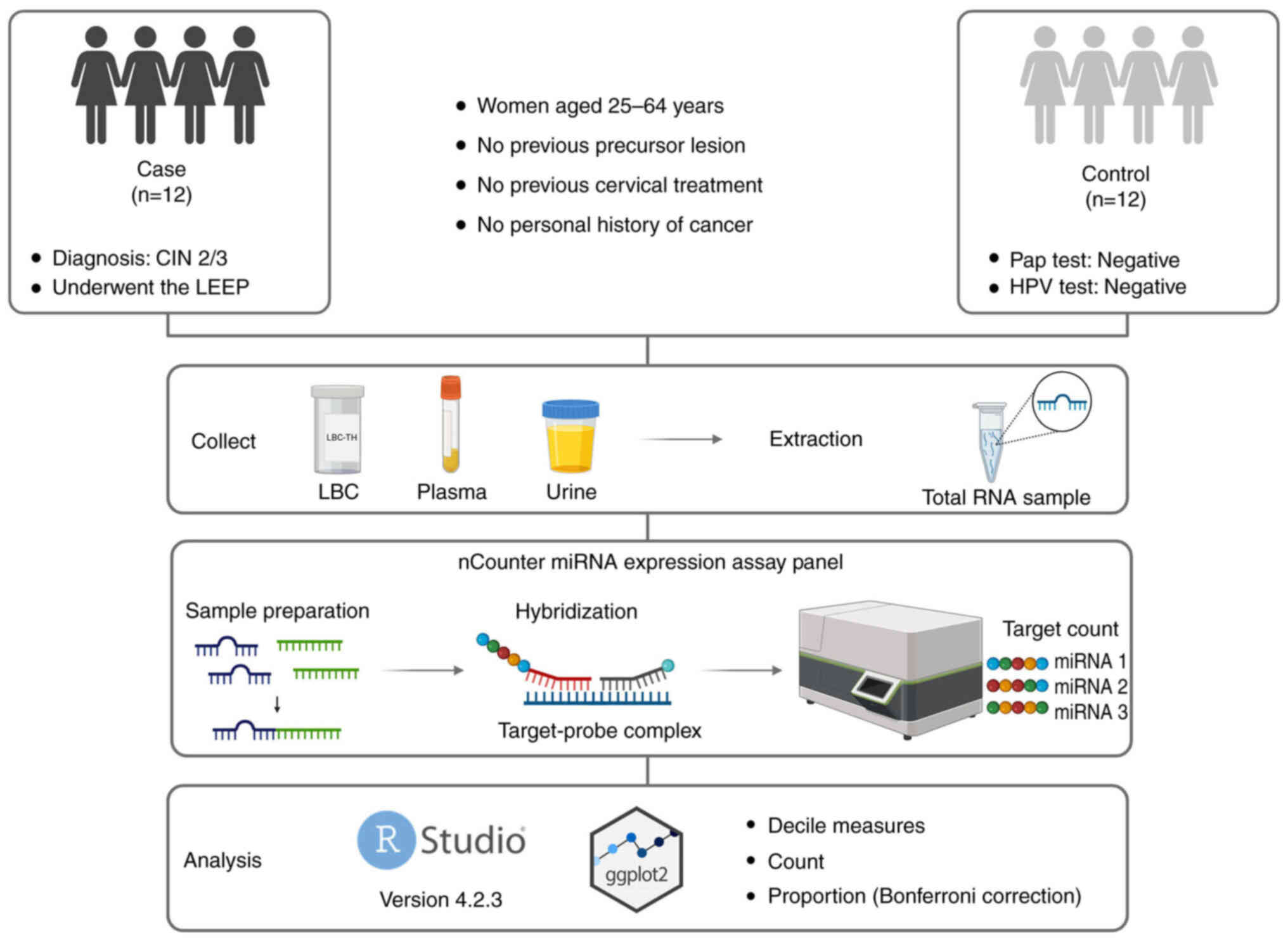

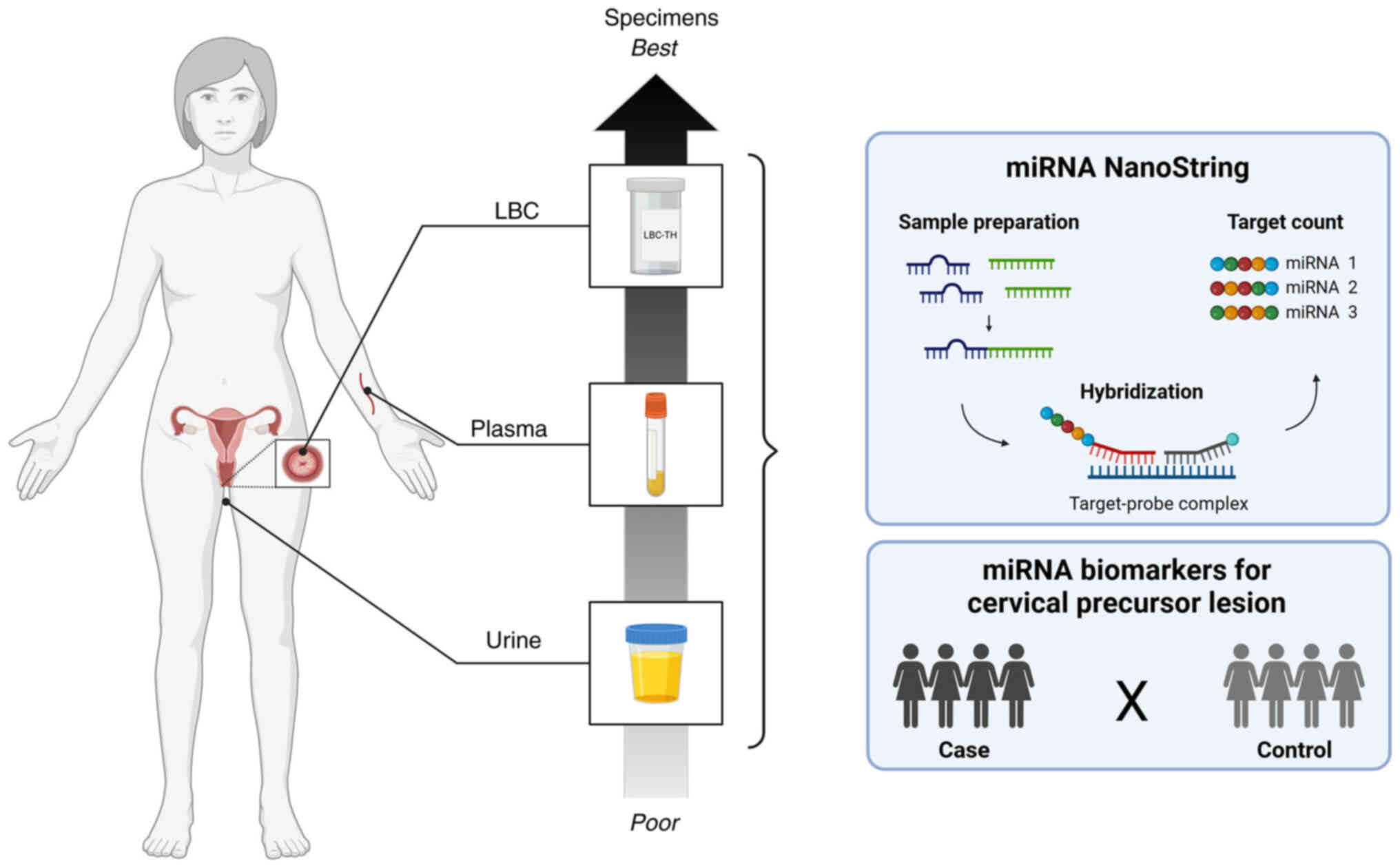

An overview of the methods and key steps of the

present study are presented in Fig.

1. The present study included 24 women, with paired LBC, plasma

and urine samples collected from each participant at the Prevention

Department of Barretos Cancer Hospital, Barretos, Brazil from June

2021 to November 2022. The present study was approved by the

Research Ethics Committee of the Barretos Cancer Hospital

(Barretos, Brazil; approval no. 3.926.525). All patients signed an

informed consent form for their samples to be used in the

research.

Eligible participants were between 25 and 64 years

old, with no history of cervical precursor lesions, no previous

cervical procedures or prior cancer diagnoses. The case group

included 12 women with histologically confirmed high-grade cervical

intraepithelial lesion (CIN 2/3) (23), confirmed by histopathological

examination of the excised tissue obtained through the Loop

Electrosurgical Excision Procedure (LEEP). All patients in the case

group were tested for hr-HPV. The control group also comprised 12

women, selected based on negative results for both Pap smear

cytology and high-risk HPV testing, performed using the Cobas ×480™

system (Roche Diagnostics) (24).

Patients were matched by age (±2 years). The epidemiological and

clinicopathological characteristics of the study participants are

summarized in Table I.

| Table I.Participant characteristics and

characteristics in case and control groups. |

Table I.

Participant characteristics and

characteristics in case and control groups.

| Characteristic | Case group

(n=12) | Control group

(n=12) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

| Mean

(SD) | 32.41 (7.02) | 32.91 (6.87) |

| Median

(min-max) | 29.00 (25–48) | 30.50 (25–48) |

| Smoking |

|

|

|

Yes | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0.00) |

| No | 10 (83.33) | 11 (91.67) |

| Former

smoker | 1 (8.33) | 1 (8.33) |

| Alcohol

consumption |

|

|

|

Yes | 10 (83.33) | 6 (50.00) |

| No | 1 (8.33) | 2 (16.67) |

| Former

consumption | 1 (8.33) | 4 (33.33) |

| Menopausal

status |

|

|

|

Pre-menopause | 11 (91.67) | 11 (91.67) |

|

Post-menopause | 1 (8.33) | 1 (8.33) |

| Use of hormonal

contraceptives |

|

|

|

Never | 0 (0.00) | 2 (16.67) |

|

Currently | 6 (50.00) | 5 (41.67) |

|

Former | 6 (50.00) | 5 (41.67) |

| HPV vaccine |

|

|

|

Yes | 0 (0.00) | 1 (8.33) |

| No | 12 (100.00) | 11 (91.67) |

| Cytology |

|

|

|

ASC-US | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0.00) |

|

ASC-H | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

|

LSIL | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

|

HSIL | 11 (91.67) | 0 (0.00) |

|

Negative | 0 (0.00) | 12 (100.00) |

| Consolidated

diagnosisa |

|

|

| CIN

2 | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0.00) |

| CIN

2/3 | 2 (16.67) | 0 (0.00) |

| CIN

3 | 9 (75.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| HPV status |

|

|

| HPV

16 | 5 (41.67) | 0 (0.00) |

| HPV

18 | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0.00) |

| Other

hr-HPV types | 6 (50.00) | 0 (0.00) |

LBC cervical samples were collected from each

participant immediately before the LEEP (case group) or Pap test

(control group). Samples from cervical cell scraping were collected

using the Cervex-Brush® (cat. no. 36825G; Rovers Medical

Devices B.V.). A total of two cervical smear samples were collected

from each participant: One sample was preserved in BD

SurePath™ Preservative Fluid (cat. no. 491337; Becton,

Dickinson and Company) for morphological and HPV tests, and the

other sample was preserved in ThinPrep® Pap test (cat.

no. 70097-001; Hologic, Inc.) for miRNA analysis. Blood samples for

plasma were collected in anticoagulant tubes, whilst urine samples

were collected without any restrictions on time or preparation. All

fluids were stored at Barretos Cancer Hospital Biobank (25).

Biological fluids RNA isolation

LBC, plasma and urine total RNA isolation were

performed using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (cat. no. 217004; Qiagen

GmbH), miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (cat. no. 217184; Qiagen GmbH) and

Urine Cell-Free Circulating RNA Purification Mini Kit (cat. no.

56900; Norgen Biotek Corp.), respectively, according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The total RNA extracted was stored at

−80°C until use. The total RNA concentration and purity of each

sample were measured using the NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c

Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

nCounter analysis assays

miRNA expression profiling was performed using the

nCounter miRNA Expression Assay Kit (cat. no. CSO-MIR3-12;

NanoString; Bruker Spatial Biology, Inc.), according to the

manufacturer's protocol, using the nCounter Human v3 miRNA that

evaluates 798 miRNAs. In summary, 100 ng total RNA was subjected to

tag binding and hybridization with the Reporter CodeSet and Capture

ProbeSet for 24 h at 65°C. Subsequently, the samples were processed

using the NanoString PrepStation and immobilized on the nCounter

cartridge, which was transferred to the nCounter Digital Analyzer

for image capture (555 field-of-views) and data acquisition.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R version

4.2.3 in RStudio 2023 (26), with

the ggplot2 library (27) for

constructing graphical analyses. Normalization was performed using

the NanoStringNorm R package (version 1.2.1) (28). Background correction and positive

control normalization were not applied. Sample content

normalization was based on the geometric mean of housekeeping

miRNAs, which were selected for their low coefficient of variation

(CV) across all samples, as detailed in Table SI. Log transformation was applied

to the normalized values. The CV was calculated as the ratio of the

standard deviation (SD) to the mean (CV=SD/mean), providing a

dimensionless measure of dispersion across datasets with different

scales. A reduction in CV after normalization indicated effective

removal of technical noise and improved reproducibility. As CV can

be sensitive to small means, the SD was also assessed as an

alternative dispersion metric (29).

For data exploration, miRNA deciles, counts and

proportions were evaluated. Low-count miRNAs were defined as those

with <10 counts in >50% of samples. Bonferroni correction was

applied to compare the proportions of low-count miRNAs between case

and control groups within each specimen type, as well as across

different specimen types.

As no differential expression analysis was

performed, and the aim was to assess general detection capacity

rather than evaluate specific miRNAs, statistical comparisons of

individual miRNAs between groups were not performed. Therefore, no

multiple testing correction was applied.

Results

NanoString technology comparison of

raw data counts

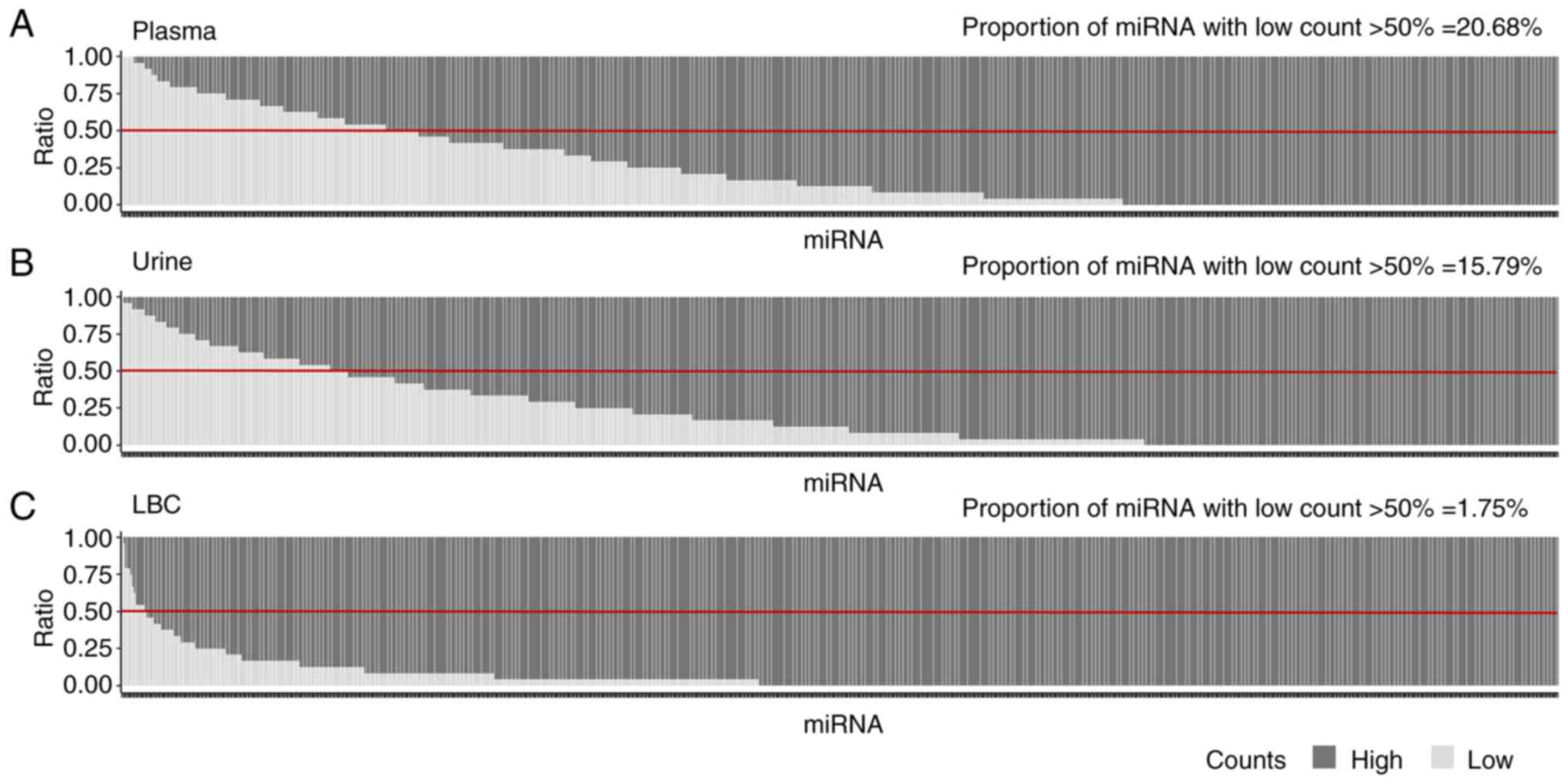

The distribution of the counts of 798 miRNAs across

LBC, plasma and urine samples was analyzed using the raw data.

Median miRNA counts were similar between the case and control

groups (Table SII, Table SIII, Table SIV).

In the raw data analysis, a cutoff was established

using the NanoStringNorm package to distinguish between low and

high counts. Counts <10 were defined as low, whilst those ≥10

were considered high. Initially, raw data counts were compared in

three specimens without stratifying by clinical group. Due to the

characteristics of the raw data, statistical tests were not applied

and the analysis remained descriptive. The detected miRNA counts in

plasma, urine and LBC were analyzed, which demonstrated that LBC

exhibited proportionally higher levels of detected miRNAs than

plasma and urine (Fig. 2). These

results suggest a greater abundance of miRNAs in LBC compared with

the other specimens. By contrast, the comparison between plasma and

urine revealed no notable difference in the proportions of high and

low counts of miRNAs, suggesting comparable levels of miRNA

detection between these two fluids.

The technical threshold was set at counts of <10,

which were defined as low. A miRNA was considered to have a low

count if its expression was <10 in >50% of samples. According

to this analysis, LBC revealed a lower percentage of detected

miRNAs with low counts (1.75%) compared with plasma (20.68%) and

urine (15.79%). This indicates a higher overall detection

efficiency of miRNAs in LBC compared with the other fluids.

Although plasma and urine demonstrated similar proportions of

low-count miRNAs, this indicates comparable levels of detectable

miRNAs in these fluids. However, further analysis is needed to

determine if similar miRNA species are being captured.

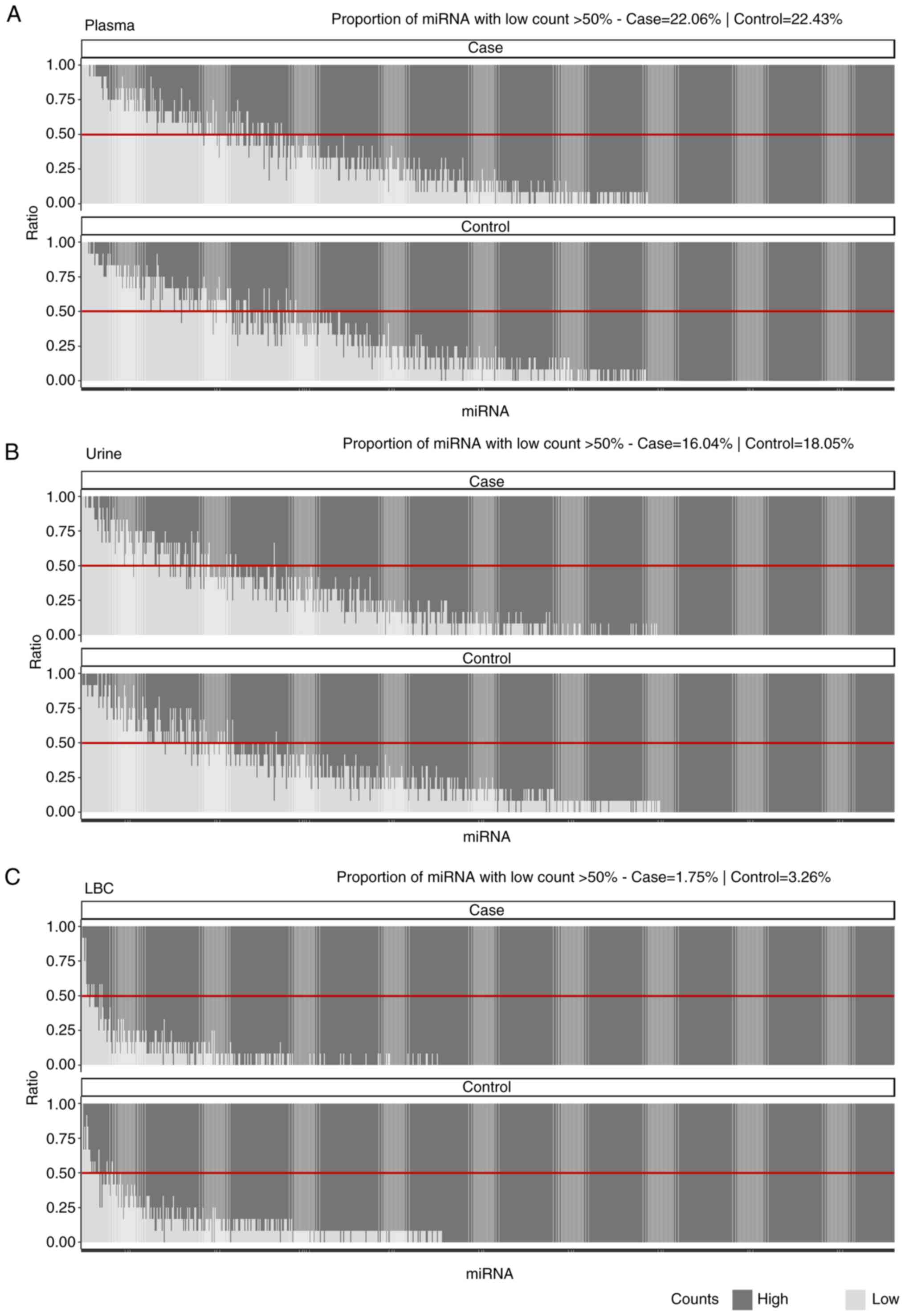

Comparison of raw data counts between

case and control groups

Additionally, a comparative assessment of raw data

counts between the case and control groups for each specimen type

was performed (Fig. 3). The results

demonstrated differences in the proportions of low-count miRNAs

between the case and control groups in LBC (case, 1.75%; control,

3.26%) and urine (case, 16.04%; control, 18.05%). This suggests

that certain miRNAs presented a higher abundance in the case group

compared with in the control group. However, in plasma, the

proportions were similar between the case (22.06%) and control

(22.43%) groups, indicating no difference in low-count miRNAs for

this specimen type.

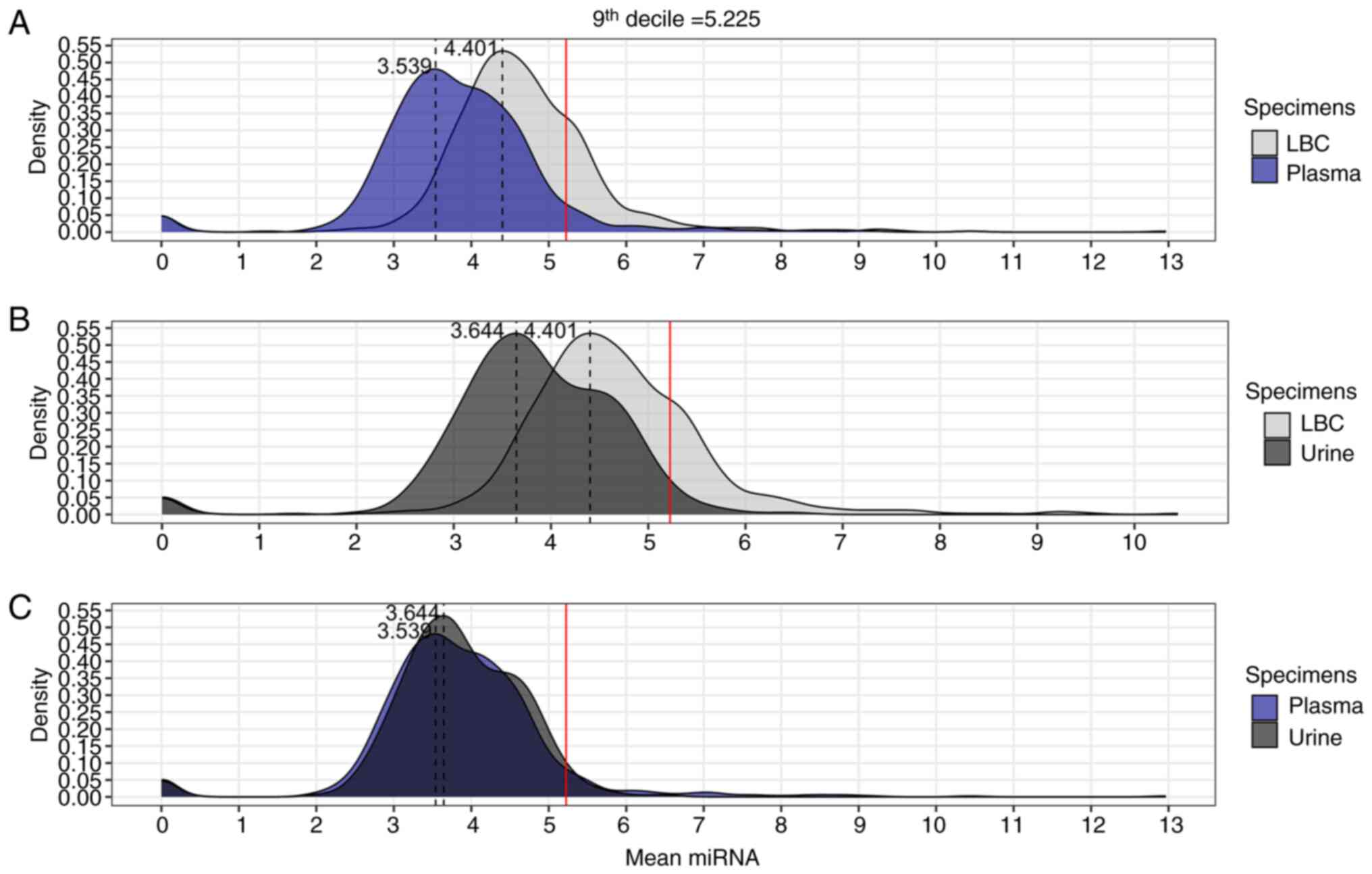

Comparison of normalized data

counts

The distribution of the counts of 798 miRNAs across

LBC, plasma and urine samples was analyzed, using the normalized

data. Median miRNA counts were similar between the case and control

groups (Table SIV, Table SV, Table SVI, Table SVII) and box plots demonstrated

variability across the sample types (Fig. S1).

Subsequently, the mean normalized counts of each

detected miRNA were compared across the three specimen types using

the normalized data (Fig. 4).

Density plots were generated to visualize the distribution of mean

miRNA counts in LBC, plasma and urine (Fig. 4). The 9th decile (5.225) was used as

a reference to identify regions with extreme values of mean miRNA

counts, allowing for a clear comparative analysis of miRNA count

distributions between the different specimens. This approach

highlighted differences and extreme values in the density plots,

facilitating the visualization of distinctive characteristics

between the analyzed fluids. Additionally, the proportions of miRNA

counts above the 9th decile were calculated for each specimen: LBC

vs. plasma, LBC vs. urine, and plasma vs. urine (Table II). The comparisons revealed that

LBC was superior to the other specimens, with a significantly

higher concentration of miRNAs with counts >9th decile (21.3%),

compared with plasma (5.89%) (P<0.01; Fig. 4A; Table

II) and urine (2.88%) (P<0.01; Fig. 4B; Table

II). Furthermore, the difference in miRNAs with high counts

>9th decile between plasma (5.89%) and urine (2.88%) was

significant (P<0.01; Fig. 4C;

Table II).

| Table II.Comparison of the proportions of

microRNA counts >9th decile between liquid-based cytology,

plasma and urine samples. |

Table II.

Comparison of the proportions of

microRNA counts >9th decile between liquid-based cytology,

plasma and urine samples.

| A, LBC vs.

plasma |

|---|

|

|---|

| Specimen | Count | Proportion, % | P-value |

|---|

| LBC | 170/798 | 21.3 | <0.01 |

| Plasma | 47/798 | 5.89 |

|

|

| B, LBC vs.

urine |

|

|

Specimen | Count | Proportion,

% | P-value |

|

| LBC | 170/798 | 21.3 | <0.01 |

| Urine | 23/798 | 2.88 |

|

|

| C, Plasma vs.

urine |

|

|

Specimen | Count | Proportion,

% | P-value |

|

| Plasma | 47/798 | 5.89 | <0.01 |

| Urine | 23/798 | 2.88 |

|

Discussion

The early detection of CC precursor lesions is

crucial for improving patient prognosis, as timely intervention can

markedly reduce progression to invasive cancer (5). LB provides a unique opportunity to

identify molecular changes at an early stage, even before

morphological alterations become evident in conventional cytology

or histopathology (6). In this

context, circulating miRNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers,

allowing the detection of early oncogenic alterations and enhancing

the sensitivity of current screening strategies (30,31).

However, selecting the most appropriate specimen for LB-based

diagnostics remains a critical challenge (32). Therefore, the present study

performed a comparative analysis of plasma, urine and LBC as

potential specimens for CC precursor lesions detection, using raw

and normalized counts of detected miRNAs.

The initial analysis revealed substantial

differences in the levels of detected miRNAs between plasma, urine

and LBC. LBC exhibited higher levels of detected miRNAs than plasma

and urine, suggesting its potential superiority in capturing miRNA

biomarkers for the detection of CC precursor lesions. This

observation is in-line with previous studies highlighting LBC as a

potential specimen for LB-based identification of CC precursor

lesions (10,33). By contrast, plasma and urine

demonstrated comparable levels of detected miRNAs, indicative of a

relative similarity between these two specimens. Although plasma

and urine demonstrated comparable levels of detected miRNAs, plasma

remains the preferred specimen for LB because it directly reflects

systemic processes and captures miRNAs released from circulating

cells (34).

Although there was no primary aim to compare

diagnostic groups in the present study, an exploratory analysis of

raw miRNA counts was performed to assess differences in detection

between the case and control groups. However, no differences were

observed, suggesting that interindividual variability, rather than

biological factors, may underlie the similar detection rates. This

is consistent with previous studies reporting that circulating

miRNA profiles are affected by factors such as cellular origin,

sample handling and inherent physiological variation between

individuals (35,36). Given the small sample size and early

stage of the disease, such variability is expected and has been

cited as a challenge in LB interpretation (37,38).

These findings are therefore complementary and do not support

differential expression analysis.

Data normalization provided more information about

the diagnostic utility of plasma and urine. Scatterplots

demonstrated uniformity and similarity in detected miRNA levels

between plasma and LBC, highlighting the potential of plasma as a

promising specimen for miRNA detection. By contrast, urine revealed

greater variability in miRNA levels, posing challenges to

diagnostic accuracy. Density plots accentuated the disparities

between plasma and urine, with plasma demonstrating a distribution

profile more similar to LBC. This observation underlines the

diagnostic superiority of plasma over urine, as the latter

exhibited notable differences with the standard specimen. Moreover,

the findings of the present study highlight the importance of

selecting the most appropriate specimen for LB-based diagnostics in

CC precursor lesions. Although LBC has emerged as a pioneer in

capturing miRNA biomarkers, plasma exhibited a comparable

performance, offering advantages in diagnostic accuracy and

clinical utility (39,40). The aforementioned observations align

with previous studies that emphasize the diagnostic potential of

plasma-derived miRNAs in CC and its precursor lesions (21,41).

The robustness of plasma as a specimen for LB can be attributed to

its direct reflection of systemic processes and release of miRNA

from circulating cells (4,42), making it a valuable resource for

early cancer detection and monitoring.

By contrast, urine, despite its non-invasive

collection method and potential usefulness in certain scenarios,

presents a challenge due to its inherent variability in miRNA

levels. This variability can be attributed to contamination and

compositional differences (43),

which need to be addressed when utilizing urine for LB-based

diagnosis. However, despite the aforementioned challenges of using

the NanoString technology in the present study, other studies have

reported the use of miRNAs as biomarkers in urine using

quantitative PCR. Aftab et al (11) identified a combination of

miR-145-5p, miR-218-5p and miR-34a-5p in urine that achieved

notable results. This combination showed 100% sensitivity and 92.8%

specificity in distinguishing between patients with pre-cancer and

cancer from healthy controls. Moreover, the levels of these miRNAs

in urine were associated with those observed in serum and tumor

tissues. Notably, the expression of miR-34a-5p and miR-218-5p

emerged as independent prognostic factors for the overall survival

of patients with CC (11).

Furthermore, the NanoString nCounter system served a

key role in improving the reliability of the findings in the

present study by delivering consistent and reproducible miRNA

quantification across all specimens. Its ability to handle multiple

samples simultaneously facilitated a comprehensive comparison of

miRNA profiles between LBC, plasma and urine. Additionally, the

sensitivity of the platform in detecting miRNAs, even from degraded

samples, allowed the generation of robust expression profiles,

supporting the exploration of miRNAs as potential biomarkers for CC

screening (44).

The present has several notable strengths,

particularly its comprehensive approach to evaluating multiple

specimens (LBC, plasma and urine) for miRNA detection in CC

precursor lesions. It provides valuable insight into identifying

the optimal medium for non-invasive CC screening. Moreover, the use

of NanoString technology to analyze a broad panel of 798 miRNAs

strengthens the reliability of the data by providing a

comprehensive assessment of miRNA expression levels across

specimens. However, despite the valuable insights gained from the

comparative analysis of specimens for CC precursor lesions

detection, several limitations restrict the interpretation and

generalization of the findings. For example, the present study did

not include groups with low-grade lesions (CIN 1) and CC. Their

inclusion would have enabled a more comprehensive analysis of miRNA

detection across disease stages. Without these groups, conclusions

on the effectiveness of LBC, plasma and urine as specimens are

limited. The modest sample size and inherent heterogeneity of the

study population may also limit the statistical power and

robustness of the conclusions. In addition, due to the limited

number of samples, no differential expression analysis was

performed to identify specific miRNAs between groups. This decision

was made to avoid generating potentially unreliable results without

adequate statistical power. Considering this, the present study

focused on evaluating the overall detection performance of

NanoString technology across different specimen types. Future

studies with larger cohorts will allow for robust differential

expression analyses to explore biomarker candidates with greater

statistical confidence. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design of

the study precludes the establishment of causal relationships, and

the biological variability inherent in circulating miRNA levels may

have confounded the results. Addressing these limitations through

large-scale studies with standardized protocols and comprehensive

biomarker panels will be critical to advancing the field of

LB-based diagnostics in CC and its precursor lesions.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

demonstrate the superiority of LBC, followed by plasma, over urine

when using NanoString technology to detect miRNA biomarkers in CC

precursor lesions and control groups (Fig. 5). The comparative analysis

highlights the diagnostic superiority of plasma over urine in

capturing miRNA biomarkers for CC precursor lesions detection,

whilst LBC stands out as the most effective specimen overall. These

findings provide valuable information for clinicians and

researchers in selecting the most appropriate specimen for LB-based

diagnostics, paving the way for greater diagnostic accuracy and

improved patient outcomes in treating CC and its precursor

lesions.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present research was funded by National Support Program for

Oncological Care (PRONON), Ministry of Health (grant no.

NUP-25000.023997.2018/34) entitled: ‘Identificação de biomarcadores

para screening e detecção precoce de tumores no contexto do Sistema

Único de Saúde (SUS)’, Barretos Cancer Hospital Research Incentive

Program (PAIP) (grant no. not applicable) and a scholarship from

the FAPESP process (grant no. 2022/12283-6).

Availability of data and materials

The raw and normalized NanoString data generated in

the present study may be found in the National Centre for

Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus under accession

number GSE302097 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE302097.

All other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SC and AJAF developed and led the study, performed

data reviews and analyses, and prepared the manuscript. JCPR helped

with the study design. RLC assisted with the NanoString

experiments. WH participated in the data analysis. RDR helped with

the study design and critically reviewed the manuscript. RMR helped

with the study design, provided advice during the study development

and critically reviewed the manuscript. MMCM conceived and guided

the development of the study and critically reviewed the

manuscript. SC and AJAF confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have substantially revised the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Research

Ethics Committee of the Barretos Cancer Hospital (approval no.

3.926.525). Each research participant provided written informed

consent for their samples to be used in the research. All

information that could be used to identify the study participants

was kept confidential and encrypted in a secure database to ensure

full confidentiality of clinical information, laboratory findings

and the anonymity of each participant.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

|

|

2

|

Albulescu A, Plesa A, Fudulu A, Iancu IV,

Anton G and Botezatu A: Epigenetic approaches for cervical

neoplasia screening (review). Exp Ther Med. 22:14812021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Poulet G, Massias J and Taly V: Liquid

biopsy: General concepts. Acta Cytologica. 63:449–455. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

De Rubis G, Rajeev Krishnan S and Bebawy

M: Liquid biopsies in cancer diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 40:172–186. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Dasari S, Wudayagiri R and Valluru L:

Cervical cancer: Biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment. Clin Chim

Acta. 445:7–11. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ma L, Guo H, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Wang C, Bu J,

Sun T and Wei J: Liquid biopsy in cancer current: Status,

challenges and future prospects. Sig Transduct Target Ther.

9:3362024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Strander B, Andersson-Ellström A, Milsom

I, Rådberg T and Ryd W: Liquid-based cytology versus conventional

Papanicolaou Smear in an organized screening program: A prospective

randomized study. Cancer. 111:285–291. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gibson J, Young S, Leng B, Zreik R and Rao

A: Molecular diagnostic testing of cytology specimens: Current

applications and future considerations. J Am Soc Cytopathol.

3:280–294. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Marrugo-Ramírez J, Mir M and Samitier J:

Blood-based cancer biomarkers in liquid biopsy: A promising

Non-invasive alternative to tissue biopsy. Int J Mol Sci.

19:28772018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Causin RL, da Silva LS, Evangelista AF,

Leal LF, Souza KCB, Pessôa-Pereira D, Matsushita GM, Reis RM,

Fregnani JHTG and Marques MMC: MicroRNA biomarkers of High-grade

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in liquid biopsy. Biomed Res

Int. 2021:66509662021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Aftab M, Poojary SS, Seshan V, Kumar S,

Agarwal P, Tandon S, Zutshi V and Das BC: Urine miRNA signature as

a potential Non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in

cervical cancer. Sci Rep. 11:103232021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

van den Helder R, Steenbergen RDM, van

Splunter AP, Mom CH, Tjiong MY, Martin I, Rosier-van Dunné FMF, van

der Avoort IAM, Bleeker MCG and van Trommel NE: HPV and DNA

methylation testing in urine for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

and cervical cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 28:2061–2068. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Poljak M, Cuschieri K, Alemany L and

Vorsters A: Testing for human papillomaviruses in urine, blood, and

oral specimens: An update for the laboratory. J Clin Microbiol.

61:e0140322013.

|

|

14

|

Jeannot E, Latouche A, Bonneau C,

Calméjane MA, Beaufort C, Ruigrok-Ritstier K, Bataillon G, Larbi

Chérif L, Dupain C, Lecerf C, et al: Circulating HPV DNA as a

marker for early detection of relapse in patients with cervical

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 27:5869–5877. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gothwal M, Nalwa A, Singh P, Yadav G,

Bhati M and Samriya N: Role of cervical cancer biomarkers p16 and

Ki67 in abnormal cervical cytological smear. J Obstet Gynaecol

India. 71:72–77. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Pan L, Yan G, Chen W, Sun L, Wang J and

Yang J: Distribution of circulating tumor cell phenotype in early

cervical cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 11:5531–5536. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Vishnoi A and Rani S: MiRNA Biogenesis and

Regulation of Diseases: An Overview. Rani S: MicroRNA Profiling.

Volume 1509. Springer New York, New York, NY, USA: pp. 1–10. 2017,

https://link.springer.com/protocol/10.1007/978-1-4939-6524-3_1March

28–2022 View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

He Y, Lin J, Ding Y, Liu G, Luo Y, Huang

M, Xu C, Kim TK, Etheridge A, Lin M, et al: A systematic study on

dysregulated microRNAs in cervical cancer development. Int J

Cancer. 138:1312–1327. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Causin RL, de Freitas AJA, Trovo Hidalgo

Filho CM, dos Reis R, Reis RM and Marques MMC: A systematic review

of MicroRNAs involved in cervical cancer progression. Cells.

10:6682021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wei H, Wen-Ming C and Jun-Bo J: Plasma

miR-145 as a novel biomarker for the diagnosis and radiosensitivity

prediction of human cervical cancer. J Int Med Res. 45:1054–1060.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ma G, Song G, Zou X, Shan X, Liu Q, Xia T,

Zhou X and Zhu W: Circulating plasma microRNA signature for the

diagnosis of cervical cancer. Cancer Biomark. 26:491–500. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Metcalf GAD: MicroRNAs: Circulating

biomarkers for the early detection of imperceptible cancers via

biosensor and Machine-learning advances. Oncogene. 43:2135–2142.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Khieu M and Butler SL: High-Grade Squamous

Intraepithelial Lesion of the Cervix. StatPearls Treasure Island

(FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430728/August

28–2025

|

|

24

|

Rao A, Young S, Erlich H, Boyle S,

Krevolin M, Sun R, Apple R and Behrens C: Development and

characterization of the cobas human papillomavirus test. J Clin

Microbiol. 51:1478–1484. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Neuber AC, Tostes CH, Ribeiro AG,

Marczynski GT, Komoto TT, Rogeri CD, da Silva VD, Mauad EC, Reis RM

and Marques MMC: The biobank of barretos cancer hospital: 14 years

of experience in cancer research. Cell Tissue Bank. 23:271–284.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

R: The R Project for Statistical

Computing. https://www.r-project.org/October

2–2024

|

|

27

|

Wickham H: ggplot2. Springer Cham; Cham,

Switzerland: pp. 24–129. 2016, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4October

2–2024

|

|

28

|

Waggott D, Chu K, Yin S, Wouters BG, Liu

FF and Boutros PC: NanoStringNorm: An extensible R package for the

pre-processing of NanoString mRNA and miRNA data. Bioinformatics.

28:1546–1548. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Deo A, Carlsson J and Lindlöf A: How to

choose a normalization strategy for miRNA quantitative real-time

(qPCR) arrays. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 9:795–812. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Laengsri V, Kerdpin U, Plabplueng C,

Treeratanapiboon L and Nuchnoi P: Cervical cancer markers:

Epigenetics and microRNAs. Lab Med. 49:97–111. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Freitas AJA, Causin RL, Varuzza MB, Calfa

S, Hidalgo Filho CMT, Komoto TT, Souza CP and Marques MMC: Liquid

biopsy as a tool for the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of

breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 23:99522022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Adhit KK, Wanjari A, Menon S and K S:

Liquid biopsy: An evolving paradigm for Non-invasive disease

diagnosis and monitoring in medicine. Cureus. 15:e501762023.

|

|

33

|

Xie H, Norman I, Hjerpe A, Vladic T,

Larsson C, Lui WO, Östensson E and Andersson S: Evaluation of

microRNA-205 expression as a potential triage marker for patients

with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Oncol Lett.

13:35862017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Martins I, Ribeiro IP, Jorge J, Gonçalves

AC, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, Melo JB and Carreira IM: Liquid biopsies:

Applications for cancer diagnosis and monitoring. Genes.

12:3492021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

McDonald JS, Milosevic D, Reddi HV, Grebe

SK and Algeciras-Schimnich A: Analysis of circulating microRNA:

Preanalytical and analytical challenges. Clin Chem. 57:833–840.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pritchard CC, Kroh E, Wood B, Arroyo JD,

Dougherty KJ, Miyaji MM, Tait JF and Tewari M: Blood cell origin of

circulating microRNAs: A cautionary note for cancer biomarker

studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 5:492–497. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Witwer KW: Circulating microRNA biomarker

studies: Pitfalls and potential solutions. Clin Chem. 61:56–63.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Moldovan L, Batte KE, Trgovcich J, Wisler

J, Marsh CB and Piper M: Methodological challenges in utilizing

miRNAs as circulating biomarkers. J Cell Mol Med. 18:371–390. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

You W, Wang Y and Zheng J: Plasma miR-127

and miR-218 might serve as potential biomarkers for cervical

cancer. Reprod Sci. 22:1037–1041. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wang H, Zhang D, Chen Q and Hong Y: Plasma

expression of miRNA-21, −214, −34a, and −200a in patients with

persistent HPV infection and cervical lesions. BMC Cancer.

19:9862019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Hoelzle CR, Arnoult S, Borém CRM, Ottone

M, Magalhães KCSF, da Silva IL and Simões RT: MicroRNA levels in

cervical cancer samples and relationship with lesion grade and HPV

Infection. Microrna. 10:139–145. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Cafforio P, Palmirotta R, Lovero D,

Cicinelli E, Cormio G, Silvestris E, Porta C and D'Oronzo S: Liquid

biopsy in cervical cancer: Hopes and pitfalls. Cancers (Basel).

13:39682021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, Huang DY,

Huang KH, Lee MJ, Galas DJ and Wang K: The MicroRNA spectrum in 12

body fluids. Clin Chem. 56:1733–1741. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Buus R, Szijgyarto Z, Schuster EF, Xiao H,

Haynes BP, Sestak I, Cuzick J, Paré L, Seguí E, Chic N, et al:

Development and validation for research assessment of Oncotype

DX® Breast Recurrence Score, EndoPredict® and

Prosigna®. NPJ Breast Cancer. 7:152021. View Article : Google Scholar

|