Introduction

Castleman disease (CD) is a rare lymphoproliferative

disorder. It was first described by Benjamin Castleman in 1954

(1), with an estimated incidence of

~2 per 100,000 individuals in the US (2). CD is classified into unicentric CD

(UCD) and multicentric CD (MCD) types based on the extent of lymph

node involvement. A 2024 systematic review of articles published in

1995–2021 on ≥5 cases of CD reported that UCD was slightly more

frequent in women (53.7%), whereas idiopathic MCD (iMCD; 59.1%) and

human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)+ MCD (88.5%) were predominant in men

(3). The diagnosis of CD primarily

relies on complete excisional biopsy of the affected lymph nodes

and subsequent histological examination, with pathological features

such as hyaline-vascular, plasma-cell or mixed type serving as the

diagnostic gold standard. Simultaneously, it is key to exclude

other diseases that can produce CD-like changes in lymph nodes

(e.g., lymphoma, tuberculosis and immunological disorders)

(4,5). Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) and

follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS) are closely associated

with CD. It has been reported that 10–32% of patients with CD

develop PNP (6–8), while 7–10% of FDCS cases are

associated with hyaline-vascular CD (9). However, the coexistence of CD with

both PNP and FDCS remains exceedingly uncommon. Herein, we describe

a rare case of pelvic unicentric CD complicated by concurrent PNP

and low- to intermediate-grade FDCS, emphasizing the diagnostic

challenges and clinical implications of this unique

association.

Case report

A 67-year-old woman was admitted to HuiYa Hospital

of The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University

(Huizhou, China) in July 2024 with an oral ulcer and systemic

purple skin spots that had persisted for 1 month and a pelvic mass

that had persisted for 5 days. The patient had presented with

bilateral conjunctival hyperemia 1 month earlier, which gradually

progressed to systemic purple skin spots and oral ulcers. The

condition of the patient worsened: Ulcers developed on the lips and

external genitalia, prompting the patient to seek medical

attention. The patient had a 10-year history of type 2 diabetes.

The latest hypoglycemic regimen is: miglitol (50 mg once daily) and

liraglutide. The starting date for liraglutide treatment is July

2024 and the treatment dose is 0.6 mg once daily, and it will be

gradually increased to 1.2 mg once daily. Marriage and childbearing

history were unremarkable and there were no patients with similar

diseases in the family.

Physical examination (July 2024)

A general physical examination on admission revealed

no abnormalities plus a pulse oxygen saturation of 98% on room air.

Palpation revealed no superficial lymphadenopathy. Cardiovascular,

pulmonary and abdominal examination results were normal. A

dermatological evaluation revealed that the skin lesions were

predominantly located in the mucosal areas. The oral mucosa

exhibited erosions with white exudates, while the perioral region

exhibited erosions, ulcerations and crusting with a noticeable

mouth-opening limitation (Fig. 1A).

An examination of the external genitalia revealed erosive and

ulcerative lesions (Fig. 1B).

Furthermore, multiple purple skin spots with variable morphologies

and well-defined borders were noted throughout the body (Fig. 1C).

Laboratory and imaging findings

Laboratory findings (July 2024) were as follows:

Blood glucose, 10.49 mmol/l (normal range, 3.9-6.1 mmol/l);

fibrinogen, 4.05 g/l (normal range, 2.0-4.0 g/l); serum albumin,

36.0 g/l (normal range, 35–50 g/l); neutrophils,

6.65×109/l (normal range, 1.8-6.3×109/l);

normal white blood cells (normal range, 3.5-9.5×109/l),

red blood cells (normal range, 3.8-5.1×109/l); platelet

counts (normal range, 125–350×109/l); hemoglobin, 137

g/l (normal range, 115–150 g/l); and C-reactive protein, 25.96 mg/l

(normal range, 0.0-10.0 mg/l). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate

was normal (normal range, 0–20 mm/h). The creatinine level (normal

range, 53–115 µmol/l) and estimated glomerular filtration rate were

normal (normal range, 90–120 ml/min/1.73 m2) and the

urine protein levels were negative. The human chorionic

gonadotropin (normal range, 0–6.00 mIU/ml) and estradiol levels

were normal (normal range, ≤138 pg/ml). Human papillomavirus

analysis (July 2024; PCR) was positive for the high-risk PV56

genotype. HIV, hepatitis virus antibodies and syphilis-specific

antibodies were negative. The tumor marker levels were within

normal limits [carcinoembryonic antigen, <5.00 ng/ml;

α-fetoprotein, <20.00 ng/ml; carbohydrate antigen (CA)15-3,

<35.00 KU/l; CA199, 0–35.00 U/ml; CA125, 0–35.00 U/ml; CA72-4,

0–6.9 U/ml; cytokeratin 19 fragment, 0–3.30 ng/ml; neuron-specific

enolase, 0–13.00 ng/ml]. Screening for pemphigus-related

autoantibodies, including anti-bullous pemphigoid antigen (BP)180,

BP230, desmoglein (Dsg)1 and Dsg3, exhibited anti-desmoplakin 3,

anti-desmoplakin 1 and anti-BP230 antibody positivity. Antinuclear

antibodies and specific autoantibodies (ANA, anti-double-stranded

DNA antibody, anti-nRNP/Sm, anti-Sm, anti-SSA, anti-Ro-52,

anti-SSB, anti-Scl-70, anti-J0-1) associated with connective tissue

diseases were absent. IL-10 levels were 27.81 pg/ml (normal range,

0–10 pg/ml) and parathyroid hormone levels were 87.41 pg/ml (normal

range, 15–60 pg/ml), while normal levels were obtained for IL-6

(normal range, 0–7 pg/ml), C3 (normal range, 0.5-2.8 g/l)/C4

(normal range, 0.1-0.4 g/l)/IgM (normal range, 0.3-2.2 g/l)/IgG

(normal range, 8.6-17.4 g/l)/IgA (normal range, 1–4.2 g/l) and

anti-Müllerian hormone (normal range, 0–0.39 ng/ml).

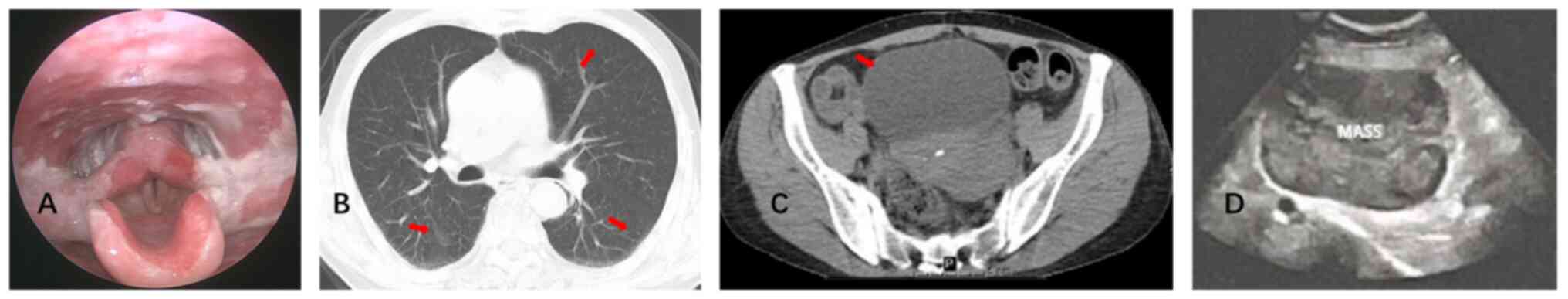

Laryngoscopy (July 2024) revealed erosions and white

pseudomembranous exudates (Fig.

2A). Chest CT (July 2024) revealed bronchitis and bilateral

mild bronchial dilation (Fig. 2B).

No enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes were observed. Pelvic CT (July

2024) (plain and contrast-enhanced) revealed a solitary mass

measuring ~114×96×116 mm in the left pelvic region. The lesion had

iso- to low-density characteristics with heterogeneous enhancement

and contained multiple patchy and non-enhancing necrotic areas

(Fig. 2C). The venous drainage of

the lesion converged into the left ovarian vein without enlarged

lymph nodes. The liver and spleen were normal in size. Transvaginal

ultrasonography (July 2024) revealed a hypoechoic mass measuring

~114×86×118 mm in the anterosuperior aspect of the left side of the

uterus (Fig. 2D).

Pathology and immunohistochemistry

(pelvic mass)

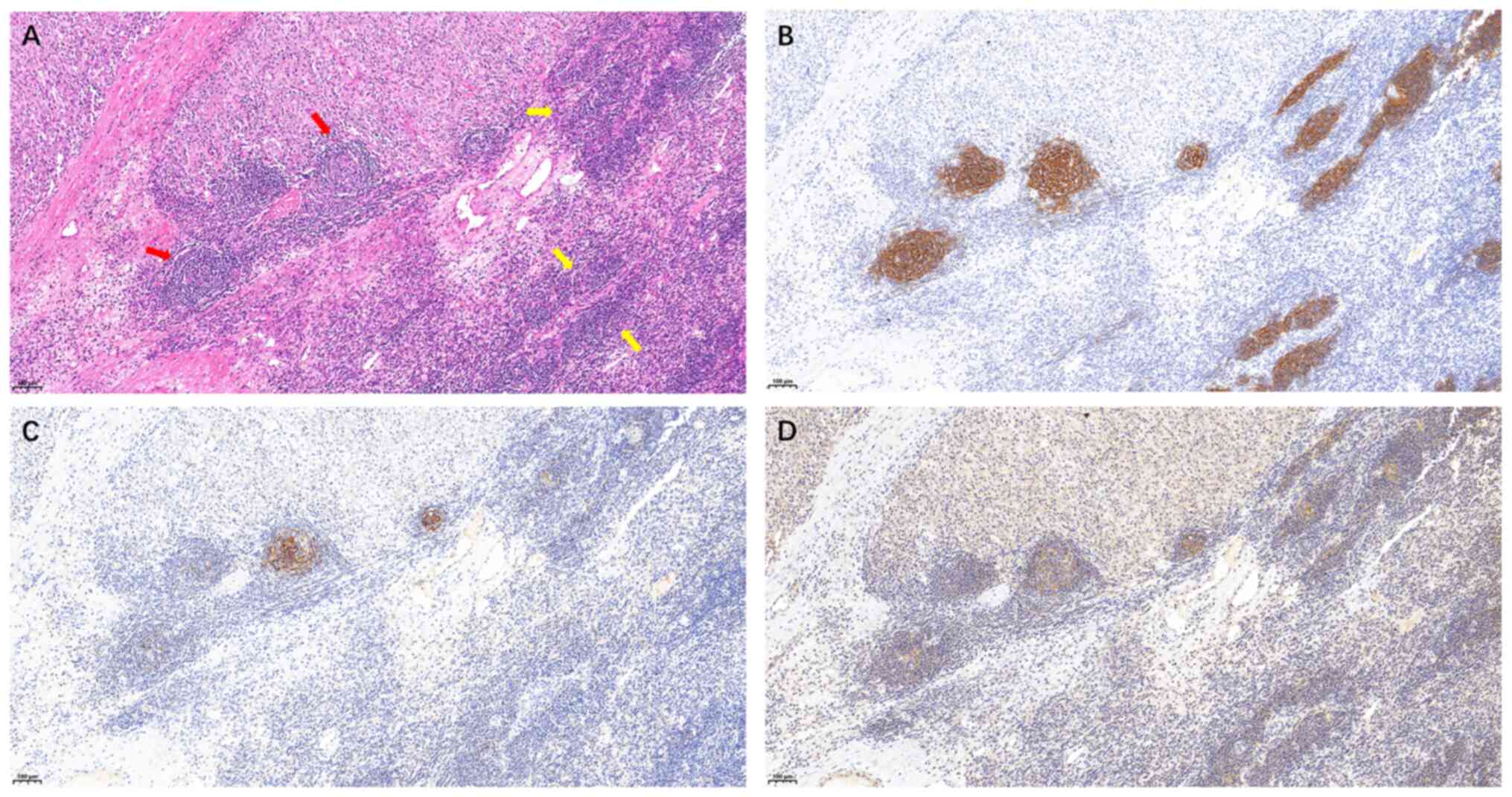

The findings of a histopathological examination of

the pelvic mass were consistent with CD with focal progression to

low- to intermediate-grade FDCS. H&E staining revealed the left

side exhibited a concentric (‘onion-skin’) configuration with

attenuation of lymphoid follicles, whereas the right side revealed

effacement of the normal follicular architecture with replacement

by a compressive mass consistent with progression to an FDC tumor

(Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemical

staining revealed the following (August 2024): Positive (focal or

scattered) for CD21, CD23, CD35, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13

(data not shown) and CD68 (scattered; data not shown); negative for

podoplanin, somatostatin receptor 2, CD20, CD3, CD1a, anaplastic

lymphoma kinase, CD30, S-100, smooth muscle actin, CD117, melanin

A, human melanoma black 45, CD34, cytokeratin, desmin and

Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs; and a Ki-67 proliferation index of

~10% (data not shown). The results described in this paper are

based on the pathological reports. Some immunohistochemical results

are non-accessible image files, such as CXCL13, CD68 and Ki-67,

etc. The immunohistochemical results suggested the focal

progression to low- to intermediate-grade FDCS (Fig. 3B-D). The specific experimental

materials and procedures can be found in the supplementary methods

and Tables SI and SII..

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed in August 2024 with

unicentric CD (UCD; hyaline-vascular) with PNP and FDCS (7). CT evaluation of the patient revealed a

solitary large mass within the pelvic region, with no evidence of

additional masses or lymphadenopathy elsewhere. Histopathological

examination was consistent with CD, fulfilling diagnostic criteria

for involvement confined to a single lymph node station. Based on

H&E staining features, the lesion was classified as the

hyaline-vascular variant. In the diagnostic workup for PNP,

infectious, metabolic, and primary neurological disorders were

initially excluded. The detection of pemphigus-associated

autoantibodies served as a key diagnostic indicator, and in

conjunction with the identified tumor, confirmed the diagnosis. The

diagnosis of FDCS was established primarily based on

histopathological characteristics observed on H&E staining,

supported by positive immunohistochemical staining for CD21, CD25

and CD35.

Treatment

After admission, the patient was treated with

intravenous methylprednisolone succinate (40 mg/dose once daily,

intravenous drip), Human immunoglobulin (pH4) [20 g/dose once daily

for a 4-day treatment course, intravenous drip (July 2024)] and

thalidomide tablets (50 mg/evening, orally administered). Following

the aforementioned treatments, a slight improvement was noted in

the mucosal ulceration with reduced trismus severity. In July 2024,

the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, pelvic tumor

resection, adhesiolysis of the abdominal cavity and pelvic

adhesiolysis. Postoperatively, the patient received antibiotic

therapy (cefuroxime sodium for injection 1.5 g, twice a day,

lasting for 2 days) and continued corticosteroid treatment

(intravenous methylprednisolone succinate, 40 mg/dose once daily,

lasting for 18 days) along with supportive care. A tacrolimus

ointment (0.1%, twice a day) was applied to the lips. Postoperative

complications included hypoalbuminemia (albumin level, 22.4 g/l),

which was managed with an intravenous human albumin infusion (10

g/dose twice daily for 6 days). Upon the confirmation of CD through

a pathological examination of the pelvic tumor, the treatment was

as follows: Thalidomide 100 mg orally once nightly,

cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 orally once a week and

prednisone 1 mg/kg orally twice a week.

Outcomes

After treatment (August 13th, 2024), the neutrophil

count of the patient (5.12×109/l), and C-reactive

protein (9.15 mg/l) and albumin levels (39.6 g/l) normalized. The

generalized purple skin spots markedly subsided compared with that

at admission and the oral and vulvar ulcers improved, although the

erosions and pain persisted (Fig.

1D). The surgical incision healed well with normotension,

reduced facial edema and decreased lip crusting. Despite the

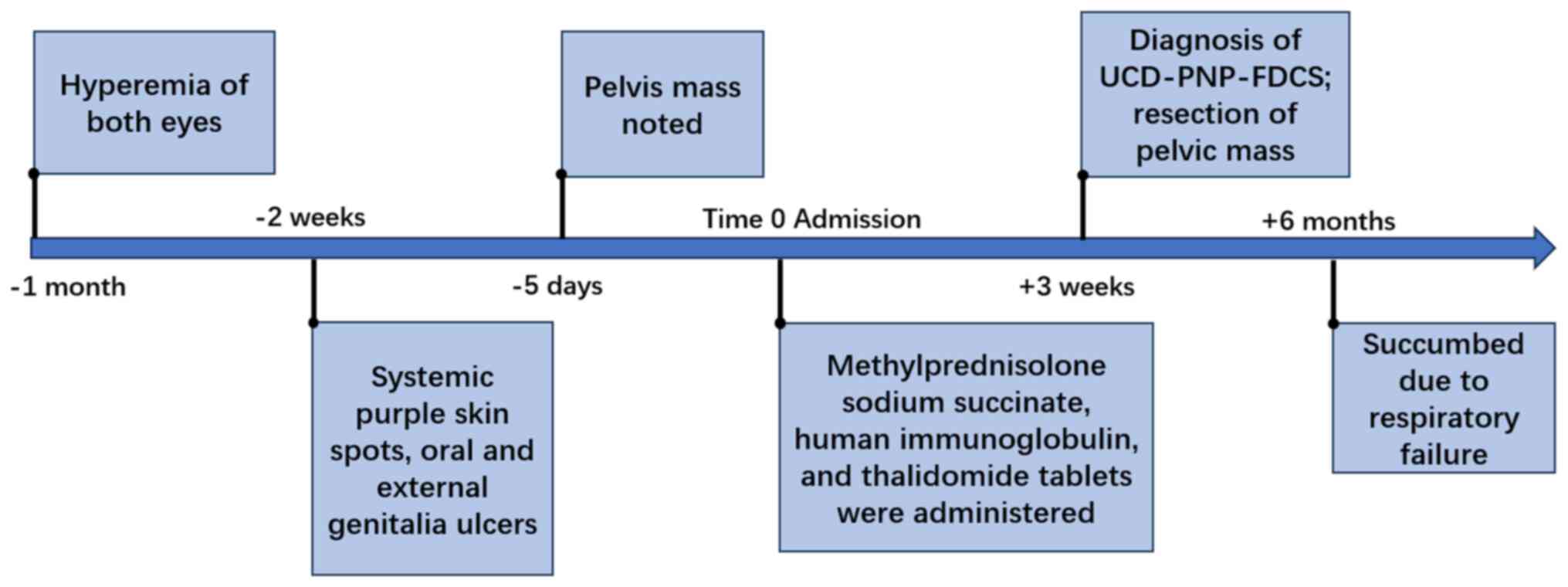

initial postoperative improvements, subsequent telephone follow-up

(January 20th, 2025) revealed that the patient had ultimately

succumbed due to respiratory failure. The timeline of the condition

of the patient is shown in Fig.

4.

Discussion

UCD typically involves a single lymph node and often

presents without systemic symptoms. UCD most commonly occurs in the

mediastinum, accounting for ~29% of all cases, followed by single

lymph nodes or nodal regions in the cervical, abdominal and

retroperitoneal areas (10). UCD

also arises in rare sites such as the adrenal gland, liver,

paravertebral region and breast (11–14).

UCD is generally asymptomatic; however, when lesions are large or

located in sensitive regions, patients may develop mass-effect

symptoms such as dysphagia or localized pain and a minority may

exhibit systemic manifestations including fever, night sweats,

weight loss or anemia (15). MCD is

characterized by lymphadenopathy in multiple regions and is further

subdivided into HHV-8+ and HHV-8−

(idiopathic) types. Unlike those with UCD, patients with MCD

exhibit lymphadenopathy and commonly present with systemic

manifestations such as fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss,

anemia, hepatic dysfunction, renal impairment and volume overload

(for example, generalized edema, pleural effusion and ascites)

(16). Both UCD and MCD can be

complicated by PNP and bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), which are

associated with a poor prognosis (7,10,17).

PNP is a severe autoimmune blistering disease that

primarily involves the oral mucosa and skin, and often initially

presents as persistent oral ulcers or erosions. Other mucosal

sites, such as the conjunctiva and nasal passages, may also be

affected along with the skin, where polymorphic bullae and erythema

are common (18). The respiratory

system is frequently involved, with ~54% of patients exhibiting

respiratory symptoms, including pulmonary dysfunction and, in

certain cases, respiratory failure (18). FDCS is a rare low- to

intermediate-grade sarcoma that typically presents as a

slow-growing, painless and localized mass (9). Most patients are asymptomatic and

local symptoms usually arise only when the tumor compresses the

adjacent structures. Respiratory system involvement is rare. On

H&E staining, the tumor cells of FDCS displayed abundant pale

to eosinophilic cytoplasm, oval to elongated spindle-shaped nuclei,

occasional cytoplasmic vacuolation and small nucleoli.

Immunohistochemically, FDCS typically expresses follicular

dendritic cell markers including CD21, CD23 and CD35; the diagnosis

is established by associating these characteristic morphologic

features with a supportive immunophenotype (9,19,20).

The present study further reviewed case reports and

meta-analyses of UCD coexisting with FDCS and PNP. These findings

suggested that adults with UCD as well as FDCS or PNP generally do

not present with notable laboratory abnormalities and that CD

complicated by PNP may not exhibit positive pemphigus-related

autoantibodies. Due to the complexity and difficulty of diagnosing

CD, international evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment

guidelines were promulgated in previous years (7,10,16).

The diagnosis of CD and its associated complications depends

primarily on a biopsy and histopathological examination (3,21).

Furthermore, these guidelines advocate comprehensive laboratory and

imaging evaluations to exclude conditions that may produce CD-like

changes such as infections, lymphomas and polyneuropathy,

organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein and skin changes

syndrome (10).

Surgical resection, the treatment of choice for UCD,

is often curative. Surgical intervention not only enables complete

excision of the CD lesion, but it also mitigates the associated

hyperinflammatory state (10,22).

In patients with UCD and marked inflammation whose lesions are

initially unresectable, treatment regimens extrapolated from iMCD,

such as siltuximab in combination with glucocorticoids or the

thalidomide-cyclophosphamide-prednisone protocol, may be employed

(22). Surgical excision should be

performed if medical therapy induces sufficient lesion regression

for complete removal (10).

However, patients with UCD and concomitant PNP and BO tend to have

a worse prognosis. In cases of UCD associated with PNP,

international consensus and guidelines recommend surgical resection

(7,10). Nonetheless, even when the primary

lesion is controlled, PNP frequently leads to respiratory

complications (for example, BO), which may result in fatal

respiratory failure in certain patients (7,23).

Timely intervention is necessary and lung transplantation is an

option. Complete surgical resection is the preferred treatment

option for patients with FDCS. In cases that cannot be cured or

show recurrence, adjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy and targeted

immunotherapy may be considered; however, large-scale evidence to

support these treatment methods is currently lacking (9).

Due to the rarity of CD coexisting with FDCS,

survival outcomes are referenced from FDCS cases, which report a

median progression-free survival of ~21 months and median overall

survival (OS) of ~50 months (24).

CD with concomitant PNP is associated with a poor prognosis;

patients with PNP have 1- and 3-year OS rates of 76.9 and 57.6%,

respectively, compared with 98.6 and 88.3% in those without PNP

(P<0.001) (8). The development

of BO is the key adverse prognostic factor in PNP (8,25).

According to the Consensus Statements of

Deployment-Related Respiratory Disease and Chinese Guidelines for

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus, patients with CD should undergo regular

pulmonary function testing (PFTs). A decline in diffusing capacity

warrants further evaluation using high-resolution chest CT and, if

indicated, a lung biopsy to confirm or exclude BO (26,27).

The European Guidelines further advise complete PFTs (including

diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide),

inspiratory-expiratory high-resolution CT, 6-min pulmonary walk

test or cardiopulmonary exercise examination (when available) and

arterial blood gas analysis at diagnosis (27). For patients with active disease or

progressive respiratory symptoms, symptom review and spirometry

every 3 months are recommended, with repeat high-resolution CT or

additional examinations (for example, cardiopulmonary exercise

examination or surgical biopsy) if a rapid forced expiratory volume

in 1 sec decline or worsening symptoms occur. In clinically stable

patients, PFT intervals may be extended to every 6 months; in

long-term stable cases, it can be extended to 6–12 months (28). These observations underscore the

importance of guideline-directed dynamic surveillance for BO in

patients with confirmed CD and/or PNP.

The present case represents a rare instance of CD

associated with PNP and FDCS. Upon admission, the patient was

treated with methylprednisolone, thalidomide and immunoglobulin to

alleviate the inflammation along with mucosal care of the lips and

perineum. Surgical resection was performed after the oral mucosal

condition of the patient was deemed tolerable for intubation. Upon

the confirmation of CD through a pathological examination of the

pelvic tumor, the treatment was as follows: Thalidomide 100 mg

orally once nightly, cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 orally

once a week and prednisone 1 mg/kg orally twice a week. However,

during subsequent follow-up, the patient succumbed due to

respiratory failure and obstructive bronchiolitis was included in

the mortality diagnosis as reported by the family.

In conclusion, CD is a key cause of PNP and BO.

Complete surgical resection of the enlarged lymph nodes is the key

treatment for patients with UCD and PNP. Therefore, monitoring for

postoperative BO is necessary. If a patient is further diagnosed

with BO, a lung transplantation can restore lung function and

improve the prognosis. Several previous studies have demonstrated

that patients experienced pulmonary function normalizing following

surgery, with nearly complete resolution of oral mucosal lesions

and marked improvement in health-related quality of life (21,29).

In addition, patients who underwent a lung transplantation achieved

a notable survival benefit compared with non-transplant with a

5-year survival rate of ~62.5% and no recurrence of CD was observed

after transplantation. Although postoperative infection remained

the predominant complication, the overall findings support lung

transplantation as an effective therapeutic option for patients

with end-stage disease (30,31).

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the 2024 Huizhou Key Project of

Science and Technology (grant no. 2024CZ010004) in the field of

health care (self-financing).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YL and FZ obtained and analyzed the information of

the patient and wrote the manuscript. ZW, GZ and QZ obtained and

analyzed the information of the patient and reviewed the discussion

part of the clinical diagnosis and treatment. QZ partially revised

the article and generated the figures, and confirmed the

authenticity of all the raw data. YL and FZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present case report was approved by The HuiYa

Hospital of The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University

(Huizhou, China; approval no. 2025-0519-001).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish the present case

information and accompanying images was obtained from the patient

and their family.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Castleman B and Towne VW: Case records of

the Massachusetts general hospital: Case No. 40231. N Engl J Med.

250:1001–1005. 1954.

|

|

2

|

Simpson D: Epidemiology of castleman

disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 32:1–10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hoffmann C, Oksenhendler E, Littler S,

Grant L, Kanhai K and Fajgenbaum DC: The clinical picture of

Castleman disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood

Adv. 8:4924–4935. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Dispenzieri A and Fajgenbaum DC: Overview

of castleman disease. Blood. 135:1353–1364. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Carbone A, Borok M, Damania B, Gloghini A,

Polizzotto MN, Jayanthan RK, Fajgenbaum DC and Bower M: Castleman

disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:842021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nikolskaia OV, Nousari CH and Anhalt GJ:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus in association with Castleman's disease.

Br J Dermatol. 149:1143–1151. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Hematology Committee of Chinese Medical

Association; Hematological Oncology Committee of China Anti-Cancer

Association; China Castleman Disease Network (CCDN), . The

consensus of the diagnosis and treatment of Castleman disease in

China (2021). Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 42:529–534. 2021.(In

Chinese).

|

|

8

|

Dong Y, Wang M, Nong L, Wang L, Cen X, Liu

W, Zhu S, Sun Y, Liang Z, Li Y, et al: Clinical and laboratory

characterization of 114 cases of Castleman disease patients from a

single centre: Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an unfavourable

prognostic factor. Br J Haematol. 169:834–842. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Facchetti F, Simbeni M and Lorenzi L:

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Pathologica. 113:316–329. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

van Rhee F, Oksenhendler E, Srkalovic G,

Voorhees P, Lim M, Dispenzieri A, Ide M, Parente S, Schey S,

Streetly M, et al: International evidence-based consensus

diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman

disease. Blood Adv. 4:6039–6050. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Raja A, Malik K and Mahalingam S: Adrenal

castleman's disease: Case report and review of literature. J Indian

Assoc Pediatr Surg. 27:109–111. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chen H, Pang X, Li J, Xu B and Liu Y: Case

Report: A rare case of primary hepatic Castleman's disease

mimicking a liver tumor. Front Oncol. 12:9742632022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Chen HY, Wu SH, Chew FY and Lee SY:

Mediastinal castleman disease presenting as a paraspinal mass

causing back pain and shortness of breath in a young adult.

Heliyon. 10:e407922024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Parra-Medina R, Guio JI and López-Correa

P: Localized castleman's disease in the breast in a young woman.

Case Rep Pathol. 2016:84139872016.

|

|

15

|

Boutboul D, Fadlallah J, Chawki S, Fieschi

C, Malphettes M, Dossier A, Gérard L, Mordant P, Meignin V,

Oksenhendler E and Galicier L: Treatment and outcome of unicentric

castleman disease: A retrospective analysis of 71 cases. Br J

Haematol. 186:269–273. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Fajgenbaum DC, Uldrick TS, Bagg A, Frank

D, Wu D, Srkalovic G, Simpson D, Liu AY, Menke D, Chandrakasan S,

et al: International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria

for HHV-8-negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease.

Blood. 129:1646–1657. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu AY, Nabel CS, Finkelman BS, Ruth JR,

Kurzrock R, van Rhee F, Krymskaya VP, Kelleher D, Rubenstein AH and

Fajgenbaum DC: Idiopathic multicentric Castleman's disease: A

systematic literature review. Lancet Haematol. 3:e163–e175. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zou M, Zhan K, Zhang Y, Li L, Li J, Gao J,

Liu X and Li W: A systematic review of paraneoplastic pemphigus and

paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: Clinical features

and prognostic factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 92:307–310. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chen T and Gopal P: Follicular dendritic

cell sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 141:596–599. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Díaz Del Arco C and

Adrados M: A cytological review of follicular dendritic

cell-derived tumors with emphasis on follicular dendritic cell

sarcoma and unicentric castleman disease. Diagnostics (Basel).

12:4062022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chen R, Teng Y, Xiao Y, Zhang L, Han X,

Wang W, Lu Z and Tian X: Constrictive bronchiolitis and

paraneoplastic pemphigus caused by unicentric Castleman disease in

a young woman: A case report. Front Med (Lausanne). 11:14682512024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zhang MY, Jia MN, Chen J, Feng J, Cao XX,

Zhou DB, Fajgenbaum DC, Zhang L and Li J: UCD with MCD-like

inflammatory state: Surgical excision is highly effective. Blood

Adv. 5:122–128. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kaur S, Singh C, Bal A and Jain A:

Unicentric Castleman disease-associated paraneoplastic pemphigus

successfully managed with surgical resection and rituximab. BMJ

Case Rep. 18:e2632752025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Jain P, Milgrom SA, Patel KP, Nastoupil L,

Fayad L, Wang M, Pinnix CC, Dabaja BS, Smith GL, Yu J, et al:

Characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients with

follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Br J Haematol. 178:403–412.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Irrera M, Bozzola E, Cardoni A, DeVito R,

Diociaiuti A, El Hachem M, Girardi K, Marchesi A and Villani A:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus and Castleman's disease: A case report and

a revision of the literature. Ital J Pediatr. 49:332023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Chinese Society of Dermatology CDA,

Dermatology Branch of China International Exchange, Promotive

Association for Medical and Health Care, Rare Skin Diseases

Committee, China Alliance for Rare Diseases, National Clinical

Research Center for Dermatologic and Immunologic Diseases, . Expert

consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of paraneoplastic

pemphigus in China (2025 version). Chin J Dermatol. 58:289–296.

2025.(In Chinese).

|

|

27

|

Falvo MJ, Sotolongo AM, Osterholzer JJ,

Robertson MW, Kazerooni EA, Amorosa JK, Garshick E, Jones KD,

Galvin JR, Kreiss K, et al: Consensus statements on

deployment-related respiratory disease, inclusive of constrictive

bronchiolitis. Chest. 163:599–609. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Antiga E, Bech R, Maglie R, Genovese G,

Borradori L, Bockle B, Caproni M, Caux F, Chandran NS, Corrà A, et

al: S2k guidelines on the management of paraneoplastic

pemphigus/paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome initiated

by the European academy of dermatology and venereology (EADV). J

Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 37:1118–1134. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen W, Zhao L, Guo L, Zhao L, Niu H, Lian

H, Dai H, Chen J and Wang C: Clinical and pathological features of

bronchiolitis obliterans requiring lung transplantation in

paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman disease. Clin

Respir J. 16:173–181. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liu YT, Zhen JF, Gao YH, Li SY, Dang Y, Xu

HY, Zhang L and Li J: Unicentric Castleman disease complicated with

bronchiolitis obliterans: A single-centre retrospective study from

China. Br J Haematol. 206:1129–1135. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Yue B, Huang J, Jing L, Yu H, Wei D, Zhang

J, Chen W and Chen J: Bilateral lung transplantation for Castleman

disease with end-stage bronchiolitis obliterans. Clin Transplant.

36:e144962022. View Article : Google Scholar

|