Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of

cancer-related mortality worldwide, accounting for 18.7% of all

cancer deaths, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprising

~85% of cases (1). For patients

with early-stage NSCLC, surgical resection offers the best chance

for long-term survival (2).

However, recurrence after curative surgery remains a major

challenge (3). Emerging evidence

highlights the prognostic importance of a pathological feature

known as spread through air spaces (STAS), a pattern of invasion

where tumor cells disseminate into alveolar spaces beyond the tumor

margin, occurring in ~50% of resected NSCLC cases (4,5). The

presence of STAS has been associated with early recurrence and poor

survival, with 5-year recurrence-free and overall survival rates

nearly halved compared with STAS-negative cases, particularly in

patients undergoing limited resections (6). This suggests that lobectomy or wider

surgical margins may be more appropriate for patients with STAS to

reduce the risk of recurrence. However, its identification

currently relies entirely on postoperative pathological examination

of resected specimens, which remains the standard for STAS

diagnosis (7). This creates a key

gap in preoperative planning, as STAS status is unknown when

deciding surgical extent or resection margin.

Due to this limitation, accurately predicting STAS

preoperatively would aid thoracic surgeons in selecting surgical

strategies, planning lymph node dissection and counseling patients

about recurrence risks. Although several studies (8,9) have

developed prediction models for STAS, most of them rely on

radiomics features extracted from high-resolution CT images, which

necessitate advanced image segmentation, texture analysis and

specialized computational tools. These requirements limit the

feasibility of such models in routine clinical workflows,

particularly in community hospitals or resource-limited settings.

Therefore, there is a clear need for accessible and generalizable

models that use only routinely available clinical features.

Artificial intelligence, particularly in machine

learning (ML), has created novel opportunities to improve

predictive modeling in clinical research. Unlike traditional

statistical methods, ML algorithms can capture complex and

non-linear interactions among high-dimensional variables and have

demonstrated notably increased performance in a range of medical

applications, including pulmonary nodule characterization and lung

cancer risk prediction (10–12).

Despite these advantages, the limited interpretability of ML models

has hindered their widespread clinical adoption. To address this

concern, explainable artificial intelligence techniques such as

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) have been introduced to

improve model transparency. SHAP assigns interpretable contribution

scores to individual features, offering both global insights into

overall feature importance and local explanations for individual

predictions (13,14).

The present study aimed to develop a practical and

explainable ML model to predict STAS using only standard

preoperative data, without relying on radiomics. The present study

trained and compared five supervised ML algorithms based on

routinely available clinical, radiological and serological

variables to identify the optimal predictive model. Furthermore,

SHAP analysis was applied to interpret feature contributions and

visualize the decision-making process of the model. This

explainable, data-driven model is intended to support personalized

surgical planning and potentially improve preoperative risk

stratification in patients with NSCLC in the future.

Patients and methods

Study population

The present study was a retrospective, single-center

study that included patients aged ≥18 years who underwent

curative-intent pulmonary resection for NSCLC at Anqing Municipal

Hospital (Anqing, China) between January 2021 and December 2023.

Patients were identified using the electronic medical records.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Histopathologically confirmed NSCLC after surgical resection; and

ii) resectable NSCLC staged retrospectively according to the 9th

edition of the TNM classification (International Association for

the Study of Lung Cancer, 2024) (15), which was applied during data

analysis to ensure consistency with the most recent staging

standards. The re-staging process was performed based on available

pathological and imaging data by two thoracic surgeons to ensure

accuracy and reproducibility. Exclusion criteria were as follows:

i) Receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy

or targeted therapy prior to surgery; ii) history of other

malignancies; iii) multiple primary tumors in the same lobe of the

lung; and iv) incomplete clinical, radiological or pathological

data.

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Anqing Municipal Hospital (approval no. 2025-152). The

committee confirmed that the study design met ethical standards and

that written informed consent was obtained from all participants

prior to inclusion. No formal sample-size calculation was performed

due to the retrospective nature of the present study and all

eligible patients within the study period were included. Patients

with missing data on any included variables were excluded from the

analysis.

Data collection

Variables for STAS included: Age, sex, smoking

history, lesion location and pathological tumor (T) stage

(categorized as T0, T1 or T2 according to the 9th edition of the

TNM classification).

Radiological features based on preoperative chest CT

included nodule types [pure ground-glass opacity (pGGO), part-solid

or solid], presence of lobulation, spiculation and vacuole sign.

Due to the absence of universally standardized criteria for nodule

classification, nodule types were defined according to widely

accepted radiological principles to minimize inter-observer

variability and ensure reproducibility (16). The nodule types were as follows: i)

pGGO: A lesion indicating homogeneous increased attenuation of the

lung parenchyma without any solid component obscuring the

underlying lung architecture; ii) part-solid: A lesion containing

both ground-glass and solid components, with the solid portion

partially obscuring the lung parenchymal markings; and iii) solid:

A lesion in which the underlying lung architecture is completely

obscured by soft-tissue attenuation. All CT images were reviewed by

two experienced radiologists blinded to the outcome.

Serum tumor markers included squamous cell carcinoma

antigen (SCC), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin 19

fragment (CYFRA21-1), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and ferritin.

Continuous variables such as tumor marker levels and nodule

diameter were transformed into categorical variables: CEA (≤5.0

ng/ml as normal), CYFRA21-1 (≤3.3 ng/ml), NSE (≤17.0 ng/ml), SCC

(≤1.5 ng/ml) and ferritin (21.8-274.6 ng/ml for men, 13.0-150.0

ng/ml for women). All variable categorizations were predefined and

applied consistently across training and test sets.

Outcome definition

The primary outcome of the present study was the

presence of STAS. STAS was defined in accordance with the 2021

World Health Organization Classification of Thoracic Tumors

(7). According to this definition,

STAS is identified when free tumor cells are identified within

alveolar spaces beyond the main tumor edge, with a minimum distance

of at least two alveolar septa from the tumor margin.

All specimens were obtained from surgical resections

and independently evaluated by experienced pulmonary pathologists

blinded to clinical and imaging information. STAS+

status was assessed on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained

sections, which were prepared according to routine standardized

histopathological protocols (17),

by two experienced pulmonary pathologists using light microscopy

and was assigned only when detached tumor clusters (micropapillary,

solid nests or single cells) were clearly visible beyond the tumor

edge.

Statistical analysis and model

development

Baseline characteristics were summarized as median

and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as

counts with percentages (n; %) for categorical variables. To

develop a predictive model for STAS, five supervised ML algorithms

were used: Logistic regression, random forest, eXtreme Gradient

Boosting (XGBoost), support vector machine (SVM) and naïve Bayes

(18–22).

The dataset was randomly divided into a training and

a test set in an 8:2 ratio. Model training and evaluation were

performed using 5-fold cross-validation on the training set to

reduce random variability and prevent overfitting. Model

performance was assessed using accuracy, sensitivity, specificity

and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

(AUC). Calibration performance was quantified using the Brier score

(23), which measures the mean

squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual

outcomes, with lower values indicating improved probability

calibration. Mean ROC curves were computed by averaging across

folds. Decision curve analysis was conducted to assess the net

clinical benefit across various threshold probabilities. To

comprehensively assess model consistency, a Taylor diagram was

generated to evaluate the correlation coefficient, standard

deviation and root mean square error between predicted

probabilities and observed outcomes across models.

To optimize model performance, grid search with

5-fold cross-validation was applied to tune hyperparameters for all

five models on the training dataset. The complete parameter search

spaces and optimal settings for each model are summarized in

Table SI.

The optimal model was selected based on the highest

AUC in the test set. No feature selection techniques were applied

prior to model training. All categorical variables, including sex,

smoking history and radiological features, were converted into

dummy variables using one-hot encoding. Continuous variables such

as tumor marker levels had already been transformed into

categorical variables and therefore no additional normalization or

scaling was required. The model outputs were treated as continuous

probability scores and no fixed cut-off thresholds or predefined

risk categories were used.

To enhance interpretability, global SHapley Additive

exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was performed for the best-performing

model, which was selected based on the highest AUC in the test set

and further validated against using DeLong's test. Following

established methodological practices reported in recent oncology

and radiology research (24,25),

the SHAP analysis quantified the overall contribution of each

feature across the entire dataset. Summary and dependence plots

were then generated to visualize feature importance, effect

direction and potential interaction patterns.

All analyses were performed using Python (version

3.9), with implementation via the scikit-learn (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/index.html) and

XGBoost libraries (https://xgboost.ai/).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 584 patients with resected NSCLC were

included, among whom 259 (44.4%) were classified as

STAS+ and 325 (55.6%) as STAS−. The median

age was 62 years (IQR, 55–69). Of the patients, 318 (54.5%) were

women and 133 (22.8%) reported a history of smoking. Most patients

were classified as T1 stage (n=467, 80.0%), with fewer at T2

(n=112, 19.1%) and T3 stages (n=5, 0.9%). Common radiological signs

included lobulation (n=353, 60.5%), spicule sign (n=334, 57.2%) and

vacuolar sign (n=84, 14.4%). Nodule types were primarily subsolid

(n=326, 55.8%), followed by solid (n=199, 34.1%) and pure

ground-glass nodules (n=59, 10.1%). The most frequent tumor

locations were the right upper (n=207, 35.4%) and left upper lobes

(n=153, 26.2%). Abnormal levels of tumor markers were present in a

minority of patients: CYFRA21-1 (n=113, 19.4%), NSE (n=42, 7.2%),

CEA (n=53, 9.1%), SCC (n=20, 3.4%) and ferritin (n=93, 15.9%).

Detailed baseline characteristics are summarized in Table I.

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the

present study population (n=584). |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the

present study population (n=584).

| Variable | Patients |

|---|

| Age, years

(range) | 62 (55–69) |

| Sex |

|

|

Female | 318 (54.5) |

| Male | 266 (45.5) |

| Smoking history

(Yes) | 133 (22.8) |

| T staging |

|

| T1 | 467 (80.0) |

| T2 | 112 (19.1) |

| T3 | 5 (0.9) |

| Lobulation

(Yes) | 353 (60.5) |

| Spicule sign

(Yes) | 334 (57.2) |

| Vacuolar sign

(Yes) | 84 (14.4) |

| Tumor location |

|

| Right

lower lung | 103 (17.6) |

| Right

upper lung | 207 (35.5) |

| Right

middle lung | 32 (5.5) |

| Left

lower lung | 89 (15.2) |

| Left

upper lung | 153 (26.2) |

| Nodule type |

|

|

Subsolid | 326 (55.8) |

|

Solid | 199 (34.1) |

|

Ground-glass | 59 (10.1) |

| SCC |

|

|

Abnormal | 20 (3.4) |

|

Normal | 564 (96.6) |

| CEA |

|

|

Abnormal | 53 (9.1) |

|

Normal | 531 (90.9) |

| CYFRA21-1 |

|

|

Abnormal | 113 (19.4) |

|

Normal | 471 (80.6) |

| NSE |

|

|

Abnormal | 42 (7.2) |

|

Normal | 542 (92.8) |

| Ferritin |

|

|

Abnormal | 93 (15.9) |

|

Normal | 491 (84.1) |

| STAS |

|

|

Positive | 259 (44.4) |

|

Negative | 325 (55.6) |

Model performance evaluation

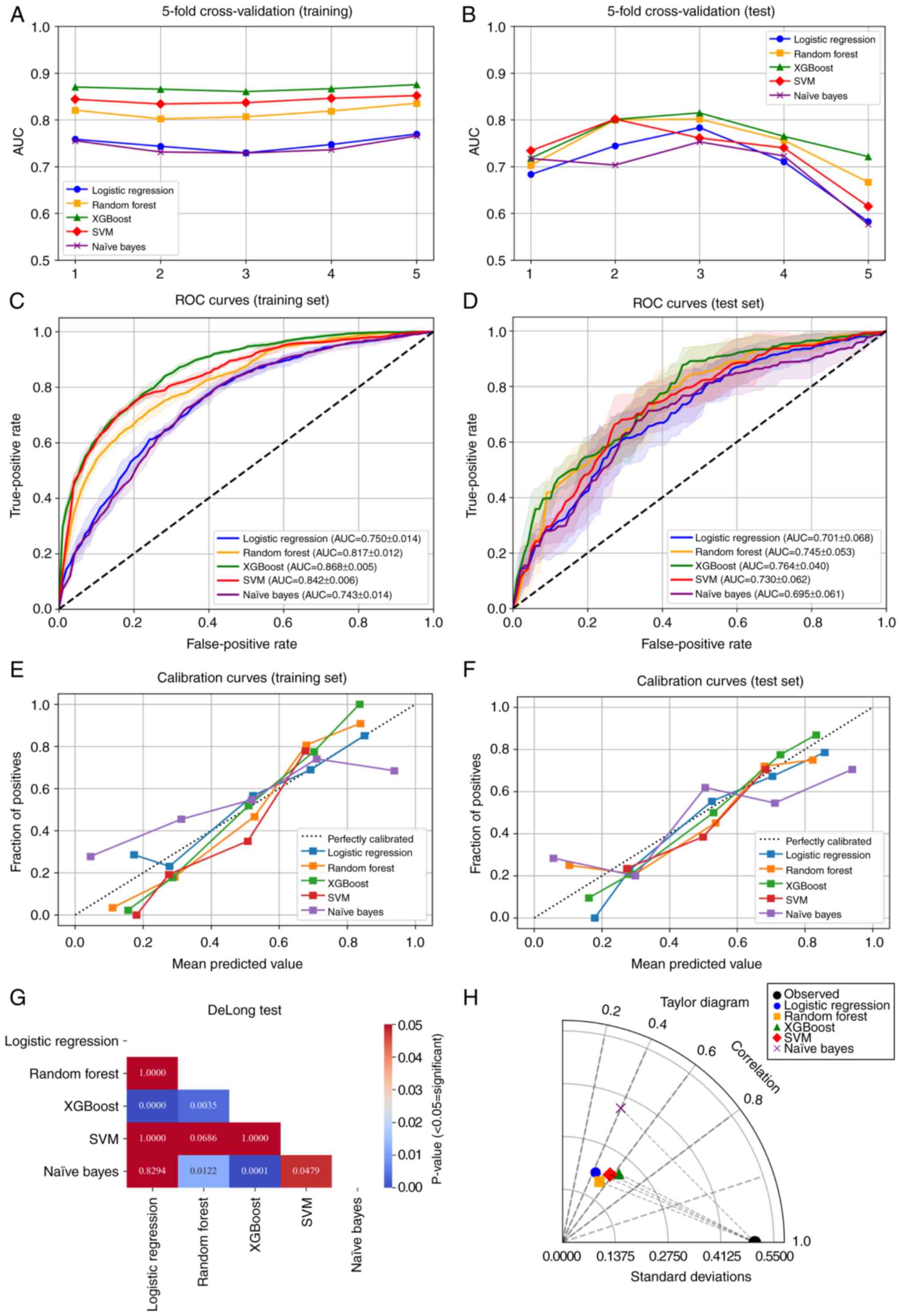

In the training set, 5-fold cross-validation

demonstrated stable performance (Fig.

1A) and the model generalized well to the test set (Fig. 1B). Among the five algorithms,

XGBoost demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving the

highest mean AUC across five cross-validation folds in the training

set (0.868; 95% CI, 0.860-0.875; Fig.

1C) and maintaining robust performance in the test set (mean

AUC =0.764; 95% CI, 0.718-0.815; Fig.

1D). In addition to the highest AUC, XGBoost exhibited balanced

accuracy, sensitivity and specificity and achieved the lowest Brier

scores (0.158 in the training set and 0.197 in the test set),

indicating notably increased discrimination and calibration among

the tested models (Table II).

| Table II.Performance of machine learning

models. |

Table II.

Performance of machine learning

models.

| Model | Dataset | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC (95% CI) | Brier score |

|---|

| Logistic

regression | Training | 0.685 | 0.724 | 0.647 | 0.750

(0.729-0.770) | 0.203 |

|

| Test | 0.638 | 0.677 | 0.600 | 0.701

(0.582-0.783) | 0.223 |

| Random forest | Training | 0.726 | 0.774 | 0.677 | 0.817

(0.802-0.835) | 0.182 |

|

| Test | 0.680 | 0.733 | 0.630 | 0.745

(0.667-0.802) | 0.206 |

| XGBoost | Training | 0.775 | 0.743 | 0.808 | 0.868

(0.860-0.875) | 0.157 |

|

| Test | 0.680 | 0.657 | 0.700 | 0.764

(0.718-0.815) | 0.197 |

| Support vector

machine | Training | 0.751 | 0.819 | 0.682 | 0.842

(0.834-0.852) | 0.173 |

|

| Test | 0.669 | 0.751 | 0.588 | 0.730

(0.615-0.801) | 0.212 |

| Naïve Bayes | Training | 0.677 | 0.636 | 0.718 | 0.743

(0.729-0.766) | 0.240 |

|

| Test | 0.660 | 0.621 | 0.700 | 0.695

(0.576-0.753) | 0.269 |

DeLong's tests demonstrated that XGBoost yielded

significantly higher AUCs compared with logistic regression, naïve

Bayes and random forest (all P<0.05), whereas its difference

with SVM did not reach statistical significance (P>0.05;

Fig. 1G). Calibration curves

(Fig. 1E and F) further

demonstrated closer agreement between predicted probabilities and

observed outcomes for XGBoost. The Taylor diagram demonstrated that

the XGBoost model was positioned closest to the reference point,

indicating the highest overall agreement with the observed data

among all algorithms (Fig. 1H).

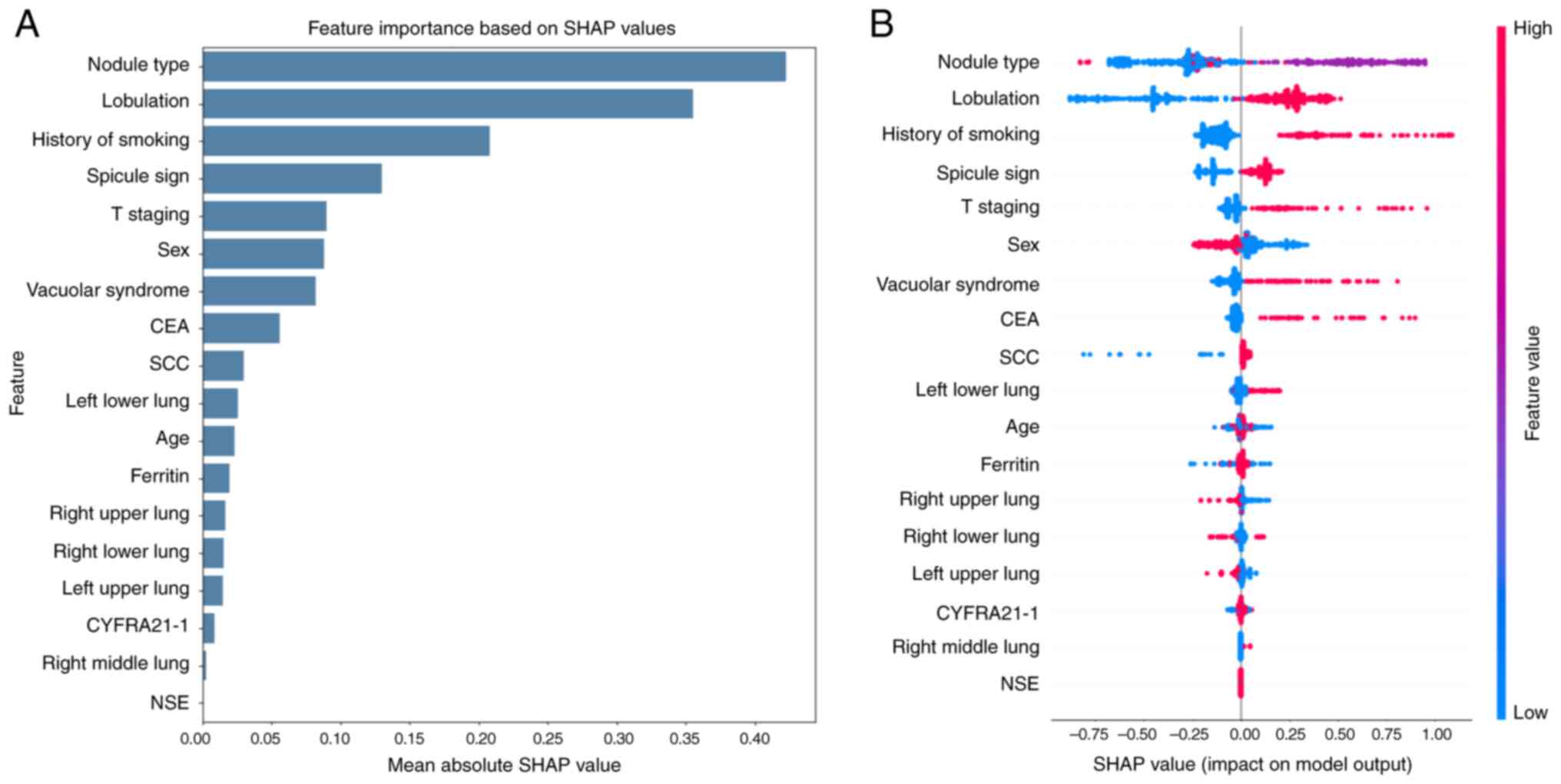

Feature importance analysis

To enhance model interpretability, the present study

employed SHAP to analyze the contribution of individual features in

the XGBoost model. The feature importance plot (Fig. 2A) demonstrated that the nodule type,

lobulation and smoking history were the top three predictors

contributing most to the decision-making of the model. The Beeswarm

plot (Fig. 2B) further illustrated

the direction and magnitude of the effect of each feature. For

example, solid nodule types and presence of lobulation positively

contributed to STAS prediction. The history of smoking was also

associated with higher predicted risk. By contrast, features such

as NSE and CYFRA21-1 exhibited minimal contribution.

Discussion

In the present study, an XGBoost-based model was

developed using real-world preoperative data to predict STAS in

surgically resectable NSCLC. Unlike previous approaches that rely

on postoperative pathology or advanced imaging techniques, the

present study model enables early, non-invasive prediction of STAS

and provides thoracic surgeons with a valuable decision-support

tool to optimize preoperative surgical planning.

Methodologically, to enhance model robustness,

reduce selection bias and determine the most appropriate algorithm

for STAS prediction under real-world clinical constraints, the

present study evaluated five distinct ML models. Among them,

XGBoost consistently outperformed the others on both the training

(AUC=0.868) and test (AUC=0.764) sets. As a gradient boosting

framework, XGBoost is particularly adept at capturing complex

non-linear relationships and feature interactions, and has

demonstrated robust performance across a wide range of clinical

diagnostic and prognostic tasks (26–28).

These prior findings were consistent with the present study

results, further supporting the suitability of XGBoost in the

context of oncology. Therefore, the present study ultimately

selected XGBoost as the final model for STAS prediction in this

study.

In terms of predictive findings, the present study

confirmed and extended existing knowledge regarding radiological

and clinical associations of STAS, while offering improved

generalizability and clinical practicality. Several prior studies

have investigated the association between STAS and radiological or

pathological features. For example, radiomics-based models have

achieved high AUCs by incorporating handcrafted features and

clinical data, but often suffer from limited generalizability due

to complex processing pipelines (29). Large retrospective analyses have

also associated STAS with programmed cell death-ligand 1

expression, spiculation and lobulated margins, yet these features

alone provide inconsistent predictive power (30). A recent study using an XGBoost and

SHAP framework in lung adenocarcinoma reported higher AUCs and

identified similar predictive features, such as nodule type and

lobulation, but relied heavily on radiomic features and was

restricted to a single histological subtype (31). By contrast, the present study model

offers broader applicability across NSCLC subtypes and requires

only routinely collected variables, making it more feasible for

real-world deployment.

Building on the performance of the model, the

contribution of individual features to STAS prediction was further

explored. The strong predictive value of nodule type and lobulation

aligns with prior studies that have consistently associated these

semantic imaging features with histological patterns associated

with STAS. Specifically, previous studies have reported that solid

and part-solid nodules, compared with pure ground-glass nodules,

are more frequently associated with aggressive histological

subtypes such as micropapillary and solid patterns (32,33).

These lesions typically reflect higher tumor cellularity and

invasiveness, making them more prone to tumor cell dissemination

into peripheral airspaces (34).

Lobulation, another key predictive feature, similarly corresponds

with biological plausibility. Radiologically, lobulated tumor

margins indicate an irregular and heterogeneous tumor-stromal

interface, which may reflect underlying extracellular matrix

remodeling, neoangiogenesis and disrupted cell adhesion at the

invasive front. These alterations facilitate tumor cell detachment

and alveolar spread, thereby elevating STAS risk (35–37).

This interpretation is supported by multiple histopathological

studies that have associated lobulated tumors with increased

invasiveness and worse clinical outcomes (38,39).

Smoking history was also identified as a key

predictor in the present study model. A recent predictive modeling

study involving 1,212 patients with clinical stage IA lung

adenocarcinoma (15) reported that

smoking history was a consistent and independent predictor of STAS

in both logistic regression models, with one achieving an AUC of

0.807 (40). Biologically, smoking

contributes to NSCLC pathogenesis through mechanisms such as

genomic instability (for example, TP53 mutations), chronic

inflammation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (41–43),

all of which promote tumor invasiveness and may facilitate airspace

spread. These findings reinforce the interpretability and clinical

relevance of the present study model. Furthermore, smoking history

is easily obtainable in routine preoperative evaluations, further

supporting its utility as a practical feature in STAS risk

prediction.

In contrast to the strong predictive signals from

imaging and clinical factors, conventional serum tumor markers

including CEA, CYFRA21-1 and NSE, contributed minimally to STAS

prediction in the present study model. This finding aligns with

previous studies, some of which included CEA in their models but

reported non-significant associations with STAS status (P=0.359) or

low odds ratios, suggesting limited discriminatory power (44,45).

Although one study identified CEA as part of a combined

clinical-radiological nomogram, its individual predictive value was

relatively weak compared with radiological features such as density

type and the distal ribbon sign (35). From a biological perspective, these

serum markers primarily reflect systemic tumor burden rather than

specific patterns of local invasion such as STAS (46). Furthermore, their serum levels are

subject to variation due to non-tumoral factors and often lack

specificity in early-stage disease. The present study findings thus

reinforce the utility of readily accessible imaging features and

clinical variables over traditional tumor markers for the

preoperative risk assessment of STAS.

Despite these promising findings, several

limitations should be acknowledged. First, this was a retrospective

study based on a single-center cohort, which may limit the

generalizability of the present study model. External validation

using multicenter datasets with broader population diversity is

necessary to confirm its robustness. Second, although the present

study selected clinically accessible features, the interpretation

of certain CT signs (for example, lobulation) may be subject to

inter-observer variability. Future research incorporating automated

image analysis or radiomics-based augmentation may further enhance

reproducibility. Third, while SHAP plots improved model

transparency, the current model still lacks direct histological

validation of the features associated with STAS, which would be

valuable for biological interpretability. Lastly, the present study

dataset did not include genomic or molecular data, which might

contribute additional predictive value and deserves exploration in

future studies.

In conclusion, the present study developed an

interpretable XGBoost model using routinely available preoperative

clinical and semantic CT features to predict STAS in surgically

resectable NSCLC. The model demonstrated favorable predictive

performance and identified clinically notable features such as

nodule type, lobulation and smoking history. By enabling early,

non-invasive risk stratification, this approach may assist thoracic

surgeons in tailoring surgical strategies prior to resection.

Future prospective and multicenter studies are warranted to

externally validate the model and facilitate its potential

integration into clinical workflows.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CY and YY conceived and designed the study. CY

collected and analyzed the data. GD, BZ, LX and FC contributed to

data interpretation and key revision of the manuscript. CY drafted

the initial manuscript. YY supervised the study and revised the

manuscript for key intellectual content. CY and YY confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Anqing Municipal Hospital (approval no. 2025-152;

Anqing, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants prior to data collection and all patient data were

anonymized before analysis to protect privacy.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hendriks LEL, Remon J, Faivre-Finn C,

Garassino MC, Heymach JV, Kerr KM, Tan DSW, Veronesi G and Reck M:

Non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 10:712024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Rathore K, Weightman W, Palmer K, Hird K

and Joshi P: Survival analysis of early-stage NSCLC patients

following lobectomy: Impact of surgical techniques and other

variables on long-term outcomes. Heart Lung Circ. 34:639–646. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lou F, Sima CS, Rusch VW, Jones DR and

Huang J: Differences in patterns of recurrence in early-stage

versus locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac

Surg. 98:1755–1761. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Xie H, Su H, Zhu E, Gu C, Zhao S, She Y,

Ren Y, Xie D, Zheng H, Wu C, et al: Morphological subtypes of tumor

spread through air spaces in non-small cell lung cancer: Prognostic

heterogeneity and its underlying mechanism. Front Oncol.

11:6083532021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Han YB, Kim H, Mino-Kenudson M, Cho S,

Kwon HJ, Lee KR, Kwon S, Lee J, Kim K, Jheon S, et al: Tumor spread

through air spaces (STAS): Prognostic significance of grading in

non-small cell lung cancer. Mod Pathol. 34:549–561. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kutlay C, Gülhan SŞE, Acar LN, Aslan M and

Tanrıkulu FB: Impact of spread through air spaces (STAS) and

lymphovascular invasion (LVI) on prognosis in NSCLC: A

comprehensive pathological evaluation. Updates Surg. 77:1205–1213.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, Borczuk

AC, Brambilla E, Cooper WA, Dacic S, Jain D, Kerr KM, Lantuejoul S,

et al: The 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors: Impact of

advances since 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 17:362–387. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu C, Meng A, Xue XQ, Wang YF, Jia C, Yao

DP, Wu YJ, Huang Q, Gong P and Li XF: Prediction of early lung

adenocarcinoma spread through air spaces by machine learning

radiomics: A cross-center cohort study. Transl Lung Cancer Res.

13:3443–3459. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang X, Ma C, Jiang Q, Zheng X, Xie J, He

C, Gu P, Wu Y, Xiao Y and Liu S: Performance of deep learning model

and radiomics model for preoperative prediction of spread through

air spaces in the surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma: A

two-center comparative study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 13:3486–3499.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Swanson K, Wu E, Zhang A, Alizadeh AA and

Zou J: From patterns to patients: Advances in clinical machine

learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell.

186:1772–1791. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhang B, Shi H and Wang H: Machine

learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment

selection: A critical approach. J Multidiscip Healthc.

16:1779–1791. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zou Y, Mao Q, Zhao Z, Zhou X, Pan Y, Zuo Z

and Zhang W: Intratumoural and peritumoural CT-based radiomics for

diagnosing lepidic-predominant adenocarcinoma in patients with pure

ground-glass nodules: A machine learning approach. Clin Radiol.

79:e211–e218. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Parisineni SRA and Pal M: Enhancing trust

and interpretability of complex machine learning models using local

interpretable model agnostic shap explanations. Int J Data Sci

Anal. 18:457–466. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Li Y, Ding J, Wu K, Qi W, Lin S, Chen G

and Zuo Z: Ensemble machine learning classifiers combining CT

radiomics and clinical-radiological features for preoperative

prediction of pathological invasiveness in lung adenocarcinoma

presenting as part-solid nodules: A multicenter retrospective

study. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 24:153303382513513652025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fong KM, Rosenthal A, Giroux DJ, Nishimura

KK, Erasmus J, Lievens Y, Marino M, Marom EM, Putora PM, Singh N,

et al: The international association for the study of lung cancer

staging project for lung cancer: Proposals for the revision of the

M descriptors in the forthcoming ninth edition of the TNM

classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 19:786–802. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zuo Z, Wang P, Zeng W, Qi W and Zhang W:

Measuring pure ground-glass nodules on computed tomography:

Assessing agreement between a commercially available deep learning

algorithm and radiologists' readings. Acta Radiol. 64:1422–1430.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dunn C, Brettle D, Cockroft M, Keating E,

Revie C and Treanor D: Quantitative assessment of H&E staining

for pathology: Development and clinical evaluation of a novel

system. Diagn Pathol. 19:422024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Christodoulou E, Ma J, Collins GS,

Steyerberg EW, Verbakel JY and van Calster B: A systematic review

shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic

regression for clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol.

110:12–22. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Venkat V, Clark K, Jeng XJ, Yao TC, Tsai

HJ, Lu TP, Hsiao TH, Lin CH, Holloway S, Hoyo C, et al: Exploring

random forest in genetic risk score construction. Genet Epidemiol.

49:e700222025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kim KS, Yoon TJ, Ahn J and Ryu JA:

Development and validation of a machine learning model for early

prediction of acute kidney injury in neurocritical care: A

comparative analysis of XGBoost, GBM, and random forest algorithms.

Diagnostics (Basel). 15:20612025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Byvatov E and Schneider G: Support vector

machine applications in bioinformatics. Appl Bioinformatics.

2:67–77. 2003.

|

|

22

|

Zhang J, Hao L, Xu Q and Gao F: Radiomics

and clinical characters based gaussian naive bayes (GNB) model for

preoperative differentiation of pulmonary pure invasive mucinous

adenocarcinoma from mixed mucinous adenocarcinoma. Technol Cancer

Res Treat. 23:153303382412584152024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Yang W, Jiang J, Schnellinger EM, Kimmel

SE and Guo W: Modified Brier score for evaluating prediction

accuracy for binary outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res. 31:2287–2296.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ling T, Zuo Z, Huang M, Wu L, Ma J, Huang

X and Tang W: Prediction of mucinous adenocarcinoma in colorectal

cancer with mucinous components detected in preoperative biopsy

diagnosis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 50:2794–2805. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ling T, Zuo Z, Huang M, Ma J and Wu L:

Stacking classifiers based on integrated machine learning model:

Fusion of CT radiomics and clinical biomarkers to predict lymph

node metastasis in locally advanced gastric cancer patients after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 25:8342025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhou Y, Zhao J, Zou F, Tan Y, Zeng W,

Jiang J, Hu J, Zeng Q, Gong L, Liu L and Zhong L: Interpretable

machine learning models based on body composition and inflammatory

nutritional index (BCINI) to predict early postoperative recurrence

of colorectal cancer: Multi-center study. Comput Methods Programs

Biomed. 269:1088742025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yang M, Chen Y, Zhou X, Yu R, Huang N and

Chen J: Machine learning models for prediction of NPVR ≥80% with

HIFU ablation for uterine fibroids. Int J Hyperthermia.

42:24737542025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lü X, Wang C, Tang M, Li J, Xia Z, Fan S,

Jin Y and Yang Z: Pinpointing potent hits for cancer immunotherapy

targeting the TIGIT/PVR pathway using the XGBoost model,

centroid-based virtual screening, and MD simulation. Comput Biol

Chem. 118:1084502025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen S, Wang X, Lin X, Li Q, Xu S, Sun H,

Xiao Y, Fan L and Liu S: CT-based radiomics predictive model for

spread through air space of IA stage lung adenocarcinoma. Acta

Radiol. 66:477–486. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang S, Xu M, Liu Y, Hou X, Gao Z, Sun J

and Shen L: PD-L1 expression and its association with

clinicopathological and computed tomography features in surgically

resected non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective cohort study.

Sci Rep. 15:243232025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wang P, Cui J, Du H, Qian Z, Zhan H, Zhang

H, Ye W, Meng W and Bai R: Preoperative prediction of STAS risk in

primary lung adenocarcinoma using machine learning: An

interpretable model with SHAP analysis. Acad Radiol. 32:4266–4277.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Su Y, Tao J, Lan X, Liang C, Huang X,

Zhang J, Li K and Chen L: CT-based intratumoral and peritumoral

radiomics nomogram to predict spread through air spaces in lung

adenocarcinoma with diameter ≤ 3 cm: A multicenter study. Eur J

Radiol Open. 14:1006302025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Xie M, Gao J, Ma X, Wu C, Zang X, Wang Y,

Deng H, Yao J, Sun T, Yu Z, et al: Consolidation radiographic

morphology can be an indicator of the pathological basis and

prognosis of partially solid nodules. BMC Pulm Med. 22:3692022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhang X, Qiao W, Shen J, Jiang Q, Pan C,

Wang Y, Bidzińska J, Dai F and Zhang L: Clinical, pathological, and

computed tomography morphological features of lung cancer with

spread through air spaces. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 13:2802–2812.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wang Y, Lyu D, Zhang D, Hu L, Wu J, Tu W,

Xiao Y, Fan L and Liu S: Nomogram based on clinical characteristics

and radiological features for the preoperative prediction of spread

through air spaces in patients with clinical stage IA non-small

cell lung cancer: A multicenter study. Diagn Interv Radiol.

29:771–785. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Liu X, Ding Y, Ren J, Li J, Wang K, Sun S,

Zhang W, Xu M, Jing Y, Gao G, et al: Analysis of factors affecting

the diagnostic efficacy of frozen sections for tumor spread through

air spaces in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 17:21682025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Qi L, Li X, He L, Cheng G, Cai Y, Xue K

and Li M: Comparison of diagnostic performance of spread through

airspaces of lung adenocarcinoma based on morphological analysis

and perinodular and intranodular radiomic features on chest CT

images. Front Oncol. 11:6544132021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Warth A, Muley T, Kossakowski CA, Goeppert

B, Schirmacher P, Dienemann H and Weichert W: Prognostic impact of

intra-alveolar tumor spread in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg

Pathol. 39:793–801. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Shi J, Xu K, Liu X, Shi M, Ji C and Ye B:

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and tumor spread through

air spaces is associated with worse clinical outcomes for resected

stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Lung Cancer.

S1525-7304(25)00222-0. 2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Huang G, Wang L, Zhao Z, Wang Y, Li B,

Huang Z, Yu X, Liang N and Li S: Development and internal

validation of predictive models for spread through air spaces in

clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.

Apr 28–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Fu H, Liu K, Zheng Y, Zhao J, Xie T and

Ding Y: Upregulation of ARHGAP18 by miR-613 inhibits cigarette

smoke extract-induced apoptosis and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in bronchial epithelial cells. Int J Chron Obstruct

Pulmon Dis. 20:2525–2537. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Díaz-Gay M, Zhang T, Hoang PH, Leduc C,

Baine MK, Travis WD, Sholl LM, Joubert P, Khandekar A, Zhao W, et

al: The mutagenic forces shaping the genomes of lung cancer in

never smokers. Nature. 644:133–144. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang W, Chen B, Zhao C, Yang D, Shima M,

Fan W, Yoda Y, Li S, Guo C, Chen Y, et al: Personal exposure to

PM2.5 and O3 induced heterogeneous

inflammatory responses and modifying effects of smoking: A

prospective panel study in COPD patients. J Hazard Mater.

494:1384712025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wang J, Yao Y, Tang D and Gao W: An

individualized nomogram for predicting and validating spread

through air space (STAS) in surgically resected lung

adenocarcinoma: A single center retrospective analysis. J

Cardiothorac Surg. 18:3372023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Yang Y, Li L, Hu H, Zhou C, Huang Q, Zhao

J, Duan Y, Li W, Luo J, Jiang J, et al: A nomogram integrating the

clinical and CT imaging characteristics for assessing spread

through air spaces in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. Front

Immunol. 16:15197662025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

van den Heuvel M, Holdenrieder S,

Schuurbiers M, Cigoianu D, Trulson I, van Rossum H and Lang D:

Serum tumor markers for response prediction and monitoring of

advanced lung cancer: A review focusing on immunotherapy and

targeted therapies. Tumour Biol. 46((S1)): S233–S268. 2023.

|