Introduction

Tube-ovarian cancer (OC) ranks eighth among

malignant neoplasms affecting females overall; however, it is the

fourth leading cancer in terms of mortality in patients of

childbearing age of <44 years (1,2).

Moreover, the incidence markedly increases in patients carrying

BRCA1/2 mutations (BRCA1mut and BRCA2mut), in whom the lifetime

breast cancer risk is >60%, with an OC risk of 40–60 and 15–30%

for those with BRCA1mut and BRCA2mut, respectively (3–5).

Inflammation has been implicated in ovarian carcinogenesis and a

history of pelvic inflammatory disease or endometriosis is

associated with an increased risk of epithelial OC (6–8).

Fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) can be proposed only

for patients with selected histotypes of OC at initial stages

apparently confined to the ovary, consisting of unilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy and peritoneal and lymph-node surgical

staging according to the histopathology of the primary tumor, and

preferably with a minimally invasive surgical approach (9,10).

However, it is unclear what the ideal FSS treatment is in case of

primary fallopian tube carcinoma, as there are no data regarding

ovarian preservation following salpingectomy, to the best of our

knowledge. Furthermore, available data regarding fertility

preservation (FP) in OC with oocytes retrieval are associated with

borderline ovarian tumors (BOTs) and non-epithelial ovarian tumors,

whilst there are no data regarding the safety of FP with oocyte

retrieval in case of invasive tube-ovarian epithelial carcinoma

(11). Additionally, the FP options

available to patients with OC are dependent on staging,

histological type, location and spread; and the options consist of

oocytes or embryos cryopreservation. FSS should be an option in

patients with early-stage OC, followed by close follow-up (1).

There are few retrospective studies and case reports

regarding assisted reproductive techniques (ART) in young patients

with OC (12,13). Moreover, there is not enough data to

provide an accurate estimate on the incidence of relapse, the

actual chance of pregnancy and its outcome. There is also currently

no data regarding FP techniques for patients with Fallopian tubes

cancer, to the best of our knowledge.

The present report describes the first case, to the

best of our knowledge, of a pregnancy with a healthy newborn using

vitrified oocytes after FSS in a young patient with a BRCA-2

mutation and invasive Fallopian tube cancer [International

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IC1] (14).

Case report

In September 2019, a 32-year-old female patient was

referred to Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the

Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS ‘Burlo Garofolo’

(Trieste, Italy) by an attending gynecologist due to suspected

bilateral hydrosalpinx identified with vaginal ultrasound. The

patient was actively seeking pregnancy and waiting to start ART.

The patient was nulliparous and did not report a family history of

gynecological cancers or other pathologies. The patient had no

prior history of symptoms indicative of pelvic inflammatory disease

or sexually transmitted infections, and denied experiencing

dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia or chronic pelvic pain. The patient had a

body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 and was a smoker.

During pre-operative checks, a diagnostic work-up

was performed, in which a second level transvaginal ultrasound

confirmed the hypothesis of a left 22×47 mm hydrosalpinx. Ovarian

tumor markers CA125, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 19.9 and

α-fetoprotein were negative. A total of 5 months later, the patient

underwent a laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy, in which

laparoscopic exploration showed both tubes congested and enlarged,

especially on the left side, attached to the ipsilateral ovarian

fossa, the posterior wall of the uterus and the omentum. The right

ovary showed an unilocular neoformation of 2 cm, with a

tight-elastic consistency. The left ovary was regular. There were

no signs of peritoneal carcinomatosis or suspicious peritoneal

nodularity. There was no pelvic or aortic lymph node enlargement.

During mobilization, a surgical spillage of the left tube occurred,

with the release of purulent, thick and brownish liquid that was

promptly aspirated (data not shown).

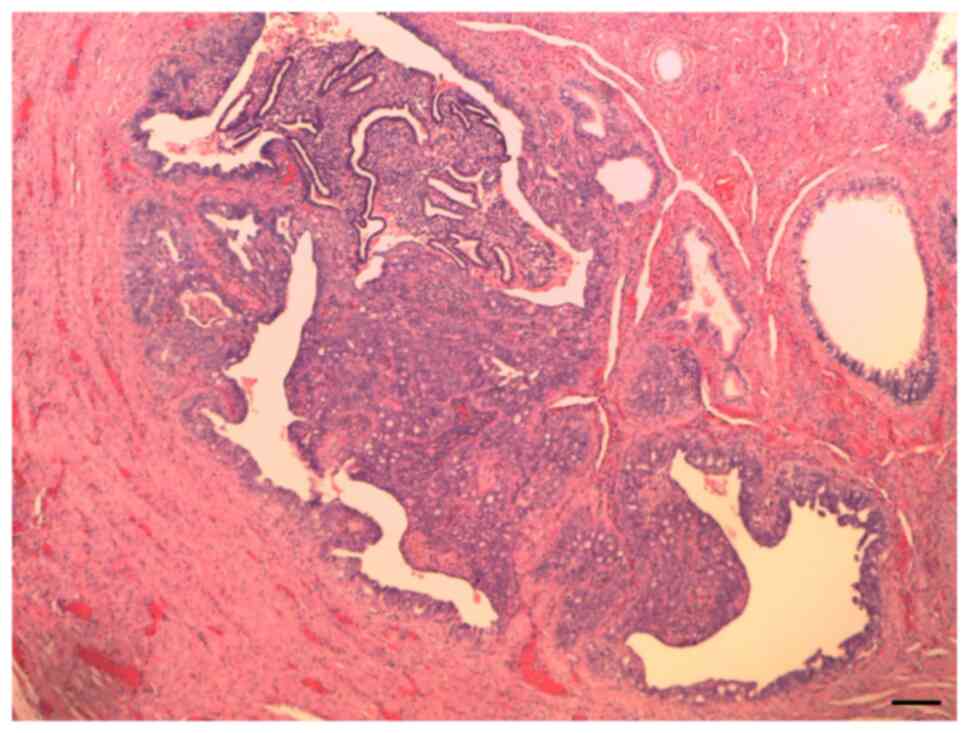

Histological examination revealed a primary

endometrioid carcinoma of the Fallopian tube, G2 (Fig. 1). Tissue samples were fixed in 4%

formaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h, embedded in paraffin,

sectioned at 4 µm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

using the HistoCore SPECTRA ST automated stainer (Leica Biosystems)

at room temperature, for ~1 h. Light microscopic evaluation was

carried out with the Aperio AT2 system (Leica Biosystems).

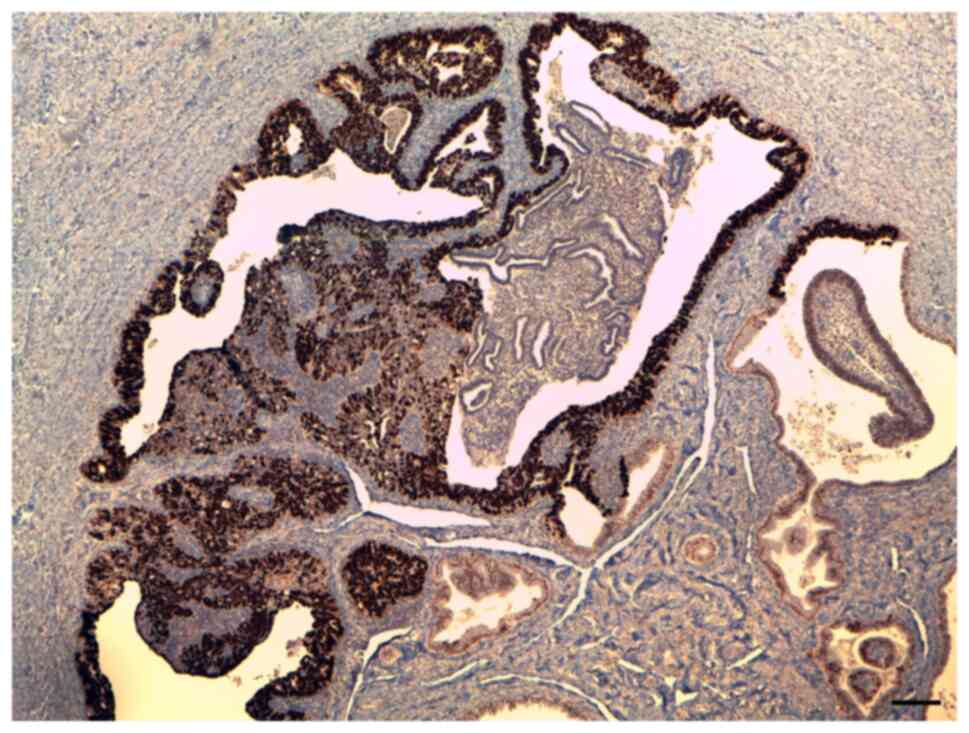

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated p53

positivity (Fig. 2) as well as

positive staining for ER and PR receptors. Representative IHC

images are not shown (the official pathology report is available

upon request). Tissue preparation followed the same fixation and

embedding protocol as aforementioned. All IHC procedures were

performed using the BenchMark ULTRA system (Roche Tissue

Diagnostics), strictly following the manufacturer's instructions.

For p53 staining, the CONFIRM anti-p53 (DO-7) Primary Antibody (REF

800–2912, Ventana, Roche) was used together with the OptiView DAB

IHC Detection Kit (REF 760–700, Ventana, Roche). Estrogen receptor

(ER) expression was assessed using the CONFIRM anti-ER (SP1) Rabbit

Monoclonal Primary Antibody (REF 790–4324, Ventana, Roche), while

progesterone receptor (PR) staining was performed with the CONFIRM

anti-PR (1E2) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (cat. no.

790-2223, Ventana, Roche). Detection of ER and PR was achieved

using the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (REF 760–500,

Ventana, Roche).

(Immunohistochemistry images of positive estrogen

and progesterone are not presented; however, an official report is

available on request.)

After the diagnosis of Fallopian tube cancer, the

patient was counselled about surgical restaging. Preoperative

work-up included chest-abdomen-pelvis PET/CT that was normal, and a

hysteroscopic endometrial biopsy that was negative for

neoplasia.

Before surgical restaging, the patient was referred

to an oncofertility consultant, considering the young age and the

strong reproductive desire of the patient. The patient underwent

oocyte preservation in July 2020. Anti-Müllerian hormone levels

were 2.08 ng/ml and ovarian stimulation was performed with 5 mg/day

letrozole + recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH) from

the second day of the menstrual cycle. On day 5 of rFSH

stimulation, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist was

administered to prevent a premature luteinizing hormone surge and

discontinued on the day of the trigger, which was achieved using a

GnRH agonist, triptorelin acetate (0.2 mg). After ovarian pick-up,

12 oocytes were cryopreserved.

In September 2020, the patient underwent

laparoscopic surgical restaging with a bilateral ovariectomy,

systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy, total omentectomy, multiple

peritoneal biopsies and peritoneal washing. Histological

examination of all the specimens was negative, and a cytological

examination of peritoneal washing did not show any cells suggestive

of malignancy. The final stage was IC1 (FIGO 2014). Furthermore,

post-surgery genetic counseling and next-generation sequencing

revealed a germinal BRCA-2 mutation in December 2020.

The present case was presented at a gynecological

oncology multidisciplinary meeting, and based on the

histopathological characteristics and tumor stage, two potential

management options were proposed: Adjuvant chemotherapy or close

surveillance. The patient expressed a strong preference against

chemotherapy and opted for a closely monitored gynecological and

breast follow-up approach. This included gynecological evaluation

with pelvic ultrasonography performed every 4 months, in addition

to an annual breast ultrasound examination.

After 3 years of negative clinical and radiological

follow-up, the patient decided to undergo embryo transfer. In July

2023, an oocyte intra cytoplasmatic sperm injection with partner

semen was performed, and a single blastocyst was transferred into

the uterus of the patient with success. Adequate endometrial

preparation was performed with oral administration of estradiol

valerate (4 mg administered on cycle days 1–3, then a dose increase

to 6 mg per day on days 10–13). After ultrasound revealed a regular

endometrium thickness, progesterone was orally administered for

adequate luteal phase support. A total of 11 days after embryo

transfer, a positive serum pregnancy test was achieved. Therefore,

the patient was administered oral estradiol and progesterone until

12 weeks.

Pregnancy was complicated by early fetal growth

restriction, for which the patient underwent amniocentesis. This

was negative with a normal karyotype 46XY at 18 weeks of gestation.

At 30 weeks of gestation, the patient developed preeclampsia and

was hospitalized for close monitoring with ultrasound and

cardiotocography. Due to a worsening of flowmetry, a caesarean

section was performed at 33 weeks and 5 days, with the birth of a

healthy male newborn of 1,152 g and Apgar of 5 and 8 at 1 and 5

min, respectively, an arterial pH of 7.33 and base excess, 5.4. The

baby was hospitalized for 1 month in neonatal intensive care due to

the gestational age and weight. The patient was discharged after 1

week with well-controlled blood pressure without puerperal

complications.

Following delivery, the patient regularly continued

gynecological and breast surveillance, consisting of clinical

evaluation and pelvic ultrasound every 6 months, and an annual

breast ultrasound. The most recent follow up was performed in

February 2025, in which the patient was asymptomatic, the

gynecological examination unremarkable and imaging studies were

within normal limits. The patient also underwent a recent breast

assessment, which was regular. The patient remains on a scheduled

follow up.

Literature review

A narrative review was performed by searching the

PubMed (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (scopus.com/), Web of

Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos/) and Google Scholar

(https://scholar.google.com/) databases

for articles published between 2000 to November 2024 involving

patients with fallopian tubes cancer and BRCA mutations that

underwent a FP with vitrified oocytes and FSS. Articles not

relevant to the present review or not written in English were

excluded, as well as cases with multiple tumors and those with

patients who underwent ex vivo oocyte retrieval or other

types of preservation techniques.

The following keywords were used for the search:

‘Fallopian tubes Cancer’, ‘BRCA mutation’, ‘Fertility sparing

treatment’ and ‘Fertility preservation’. Different combinations of

the terms were used. Due to the rarity of this pathology and

procedure, numerous case reports or case series of patients with OC

that underwent a fertility sparing treatment with vitrified oocytes

were identified, but no cases of fallopian tube cancer. For this

reason, the data is presented in a descriptive manner with the aim

to delve deeper into the topic through parallels with OC.

A total of 44 articles were identified through the

search of databases and references of the retrieved articles.

However, only two articles reported data on pregnancy with

vitrified oocytes after FSS, and they included 3 cases (15,16).

These articles included a case report on a birth of a healthy

newborn using vitrified-warmed oocytes in a young patient with

invasive mucinous ovarian carcinoma (stage IC) and two cases in two

patients with BOTs. All the pregnancies reached full term with

healthy babies, without disease recurrence during pregnancy and in

the immediate postpartum period (Table

I).

| Table I.Outcomes and characteristics of

patients in the literature. |

Table I.

Outcomes and characteristics of

patients in the literature.

| First author/s,

year | Age at diagnosis,

years | Site | Histo-type | FIGO 2014

stage | BRCA mutation | Surgical

treatment | Number of

oocytes | ART technique | Number of embryos

transferred | Age at pregnancy,

years | Type of

delivery | Gestational age at

delivery, weeks | Complications | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Alvarez et

al, 2014 | 28 | Ovaries | Invasive mucinous

ovarian carcinoma | IC | / | Bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, pelvic and aortic

lymphadenectomy, and-omentectomy | 14 | ICSI | 2 | 29 | Elective Caesarian

section | 38 | Cornual ectopic

pregnancy of 1 embryo after 18 days | (15) |

| Mayeur et

al, 2021 | 36 | Ovaries | Borderline ovarian

cancer | / | / | / | 15 | / | 2 | 37 | / | / | / | (16) |

|

| 26 | Ovaries | Borderline ovarian

cancer | / | / | / | 16 | / | 2 | 27 | / | / | / |

|

| Present case | 32 | Tubes | Endometrioid

G2 | IC1 | Yes | Bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, bilateral pelvic

linphade-nectomy, peritoneal biopsy and peritoneal washing | 12 | ICSI | 1 | 34 | Urgent Caesarian

section | 33 + 5 | Early FGR,

preecla-mpsia and flowmetry anomalies | - |

In case 1, the 28-year-old patient underwent two

cycles of ovarian stimulation, and 14 oocytes were vitrified before

FSS. A total of 1 year later, a transfer of two embryos was

performed, and 18 days after the transfer, the patient underwent a

laparotomy as a right cornual ectopic pregnancy in the uterus was

diagnosed. A wedge resection was performed, and an elective

Caesarean section was performed at week 38 of gestation, resulting

in the birth of a healthy male newborn, weighing 2,650 g.

In case 2, the two patients were 36 and 26 years

old, respectively, with BOTs. A total of 15 and 16 oocytes were

retrieved, respectively, and after 14 and 12 months, respectively,

embryo transfer was performed with two embryos. However, in this

article, the course of the pregnancies, the mode of delivery, and

the sex and birth weight of the newborns were not reported.

Discussion

Pregnancy following gynecological cancer is an

option that has only been considered and offered to patients in

recent years (17). For this

reason, very little data is available regarding ART after

gynecological cancer, particularly after FSS for OC.

According to international guidelines on ovarian and

fallopian tube cancer, conservative surgery can be proposed in

selected patients who are strongly motivated to preserve fertility,

and according to the histotype and stage disease (18,19).

FSS is feasible in patients with BOTs, non-epithelial tumors and

low-grade epithelial tumors (serous, endometrioid or mucinous

expansile sub-type) stage IA and selected IC1 stages (20). Moreover, FSS in OC presents an

acceptable overall recurrence rate of ~11%, comparable with

patients treated with radical surgery at initial stages (21). Following surgery, spontaneous

pregnancy seeking is recommended, although there is no established

timing. The spontaneous pregnancy rate following FSS for OC is high

at ~84% (22).

Conversely, data regarding ART in patients with OC

are extremely limited. Adequate evidence does not currently exist

to support the oncologic safety or harmfulness of ovarian

stimulation by pituitary gonadotropins after FSS for OC (23). In particular, an increased rate of

BOTs recurrence after stimulation is reported, ranging from

19.4–27.7%, but without an impact on mortality (24). Nevertheless, ovarian stimulation

after FSS for BOTs could be contraindicated in certain high-risk

cases, such as the presence of peritoneal implants, a

micropapillary pattern, the presence of microinvasion and in cases

of recurrence (25). Moreover,

regarding ART after invasive epithelial OC, there is limited data

from case reports and case series, which provide conflicting

information (26,27).

In patients with cancer, options for preservation of

fertility before gonadotoxic treatments include the following:

Cryopreservation (oocytes or embryos), ovarian transposition (if

pelvic irradiation is planned), pharmacological protection with

GnRH analogous and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC), and

transplantation. OTC or ovarian tissue transposition (OTT) are

options for patients with certain type of cancers (such as

hematological cancers); however, OTT cannot be considered for

patients with fallopian tube cancer (28–30).

Moreover, oocyte/embryo cryopreservation is recommended in

oncological patients if the initiation of chemotherapy can be

delayed. Due to the fewer number of oocytes expected to be

retrieved and limitations associated with preimplantation genetic

diagnosis (31,32), two consecutive stimulations should

be considered for those patients when feasible (31). However, for patients with cancer who

require radical surgery and have limited time available for FP,

controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) is not feasible. In these

cases, immature oocyte collection without COS, followed by in

vitro maturation (IVM) and oocyte freezing, represents an

alternative option. This technique has been used in conjunction

with ovarian tissue freezing. IVM is proposed as an additional

strategy to enhance the effectiveness of ovarian tissue freezing.

As antral follicles are devoid of cancer cell infiltration, oocytes

retrieved from these follicles provide a reliable option for

patients with cancer with a high risk of ovarian involvement or

in situ OC. This method offers a potential strategy for FP

in patients with recurrent disease, without the risk of cancer cell

spillage associated with standard transvaginal oocyte retrieval

(33).

Furthermore, there are issues associated with the

fertility of patients with a BRCA2 mutation. According to certain

studies, BRCA2 mutation-positive patients have lower levels of

anti-Müllerian hormone compared with patients who are BRCA-negative

and BRCA1 mutation-positive (34–37).

This may reflect a diminished oocyte reserve in these patients

(34–37). Among the patients who tried to

conceive, infertility was observed in 30.8% of those who were BRCA2

mutation-positive. Moreover, BRCA mutations result in defective DNA

repair, leading to oocyte damage with apoptotic cell death

(35,36). According to previous research, even

if patients with a BRCA2 mutation have lower levels of

anti-Müllerian hormone, this does not appear to have a negative

impact on reproductive outcome (34). Therefore, this should be considered

during onco-fertility counseling of these patients.

For the patient in the present case, after

multidisciplinary consultation with the oncologist and the

reproductive medicine consultant, adequate oncofertility counseling

was performed. Considering the risk-benefit ratio of FSS, the

low-grade histology of the tumor and the desire of the patient, it

was decided in the present case to perform in vivo oocyte

cryopreservation before restaging surgery. As there were no data

regarding the safety of ovarian preservation in early-stage primary

Fallopian tube carcinoma, the patient underwent bilateral

oophorectomy, preserving the uterus exclusively.

In vitro fertilization for oocyte

cryopreservation requires ovarian stimulation, which results in an

increased estrogen environment. For other hormone-sensitive tumors,

such as breast cancer, the safety of FP has now been established,

and indeed, controlled hormonal stimulation does not impact

progression free survival or and overall survival (38).

COS protocols have been enhanced by the

incorporation of aromatase inhibitors (39,40).

In the present case, letrozole was administered during the

stimulation phase to suppress the aromatization of androgens into

estrogens, thereby reducing circulating estrogen levels. Beyond its

role in limiting estrogen synthesis, letrozole also promotes an

increase in androgen levels, which has been associated with

improved ovarian responsiveness to stimulation (41).

Moreover, in the present case, all ultrasound

examinations performed during ovarian stimulation appeared normal,

with no evidence of cysts or suspicious areas. Before

cryopreservation, a hysteroscopy was performed in consideration of

the endometrial histotype of cancer. Rienzi et al (28) reported that, to achieve a successful

live birth through cryopreserving oocytes, ≥8 oocytes are required

for patients aged <38 years. In the present case, 12 oocytes

were cryopreserved. Additionally, the laparoscopic approach has

been described as a feasible technique by several authors (42–46).

Considering the negative thoracic-abdominal PET-CT scans in the

present case, complete laparoscopic surgical restaging with

bilateral ovariectomy was performed.

Embryo transfer was performed following hormonal

replacement therapy, initiated with oral estradiol (E2) on days 1–3

of the cycle to prepare the endometrium and inhibit spontaneous

follicular development. Estradiol was administered either at a

fixed daily dose (6 mg) or via a step-up regimen. Although no

randomized controlled trials have directly compared these

approaches, a large retrospective analysis of 8,254 oocyte donation

cycles reported similar live birth rates after a fixed daily dose

or after a step-up regimen (33.0 vs. 32.5%, respectively) (47). Furthermore, in the present case,

vaginal micronized progesterone was administrated (200 mg, ×3/day)

for adequate luteal phase support.

Regarding the fetal growth restriction and the

development of early preeclampsia in the present case, these were

complications associated with the BMI of the patient (30

kg/m2), nulliparity and smoking (48), as well as because it was >2 years

since the cancer diagnosis and the patient had not undergone

chemotherapy.

Pregnancies after gynecological cancer need to be

managed by different medical specialties; therefore, it is

desirable to have a close collaboration between consultants with an

expertise in oncology, reproductive medicine and high-risk

pregnancy in referral oncological centers.

The present case is the first case, to the best of

our knowledge, of ART after FSS for a primary Fallopian tube cancer

in a patient with BRCA2 mutation. However, there are certain

reflections to be made: On the one hand, the present report

presents the first case of the feasibility of FP with COS in case

of diagnosis of low-grade primary Fallopian tube cancer at initial

stage; whilst on the other hand, there was a fertility issue

regarding a germline pathogenic variant in the BRCA1/2 gene. In

fact, certain research suggests that the ovarian reserve of

patients with the BRCA1/2 mutation may be reduced (34). Therefore, we hypothesize a

practice-changing strategy: FP could be systematically offered to

healthy patients carrying a BRCA mutation who have not yet

completed the reproductive cycle, and then perform a risk-reducing

bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy after 35 years.

In conclusion, due to the limited reproductive

research in patients with Fallopian tube cancer, evaluating the

safety, efficacy and feasibility of FP, and post-diagnosis

pregnancy, should be considered a research priority. Reporting the

first case in the literature of pregnancy after epithelial primary

Fallopian tube cancer using conservative surgery and oocyte

freezing, to the best of our knowledge, the present report aims to

give impetus to further research in this field. Oocyte

cryopreservation appears to be a feasible method to preserve

fertility in selected cases of OC. FP by oocyte/embryo freezing

employing specific ovarian stimulation protocols could represent a

therapeutic option in young patients with BRCA1/BRCA 2 mutations

who have not completed their reproductive cycle within the 35

years, even if further evidence is needed for elucidation of the

role of BRCA mutations on fertility.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was supported by the Ministry of Health (Rome,

Italy), in collaboration with the Institute for Maternal and Child

Health IRCCS ‘Burlo Garofolo’ (Trieste, Italy).

Availability of data and materials

The next-generation sequencing data are not publicly

available as they contain information that could compromise the

privacy of research participants; however, they may be requested

from the corresponding author. All other data generated in the

present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

GS, SC, AV, GZ and GR conceived and designed the

study; AR and AM performed the experiments. GR, LN and AM performed

the analysis and interpretation of data. GS, AV, AR, GZ, SC and AM

wrote the manuscript. GS, AV, AR, AM, GZ and LN revised the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. GS

and AV confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures performed in the present study were

in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional

research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its

later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The present study

was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute for

Maternal and Child Heath IRCCS ‘Burlo Garofolo’ (approval no. RC

08/2022; April 15, 2022).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient to publish the present paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Santos ML, Pais AS and Almeida Santos T:

Fertility preservation in ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol

Endocrinol. 37:483–489. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

International Agency for Reaserch on

Cancer, Global Cancer Observatory, Cancer Today Globocan 2022, .

Ovary factsheet. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/25-ovary-fact-sheet.pdfFebruary

8–2024

|

|

3

|

Taylan E and Oktay K: Fertility

preservation in gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 155:522–529.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, .

Ovarian Cancer (Version1.2017). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/phys-ician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdfApril

15–2024

|

|

5

|

Arcieri M, Tius V, Andreetta C, Restaino

S, Biasioli A, Poletto E, Damante G, Ercoli A, Driul L, Fagotti A,

et al: How BRCA and homologous recombination deficiency change

therapeutic strategies in ovarian cancer: A review of literature.

Front Oncol. 14:13351962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rasmussen CB, Kjaer SK, Albieri V, Bandera

EV, Doherty JA, Høgdall E, Webb PM, Jordan SJ, Rossing MA, Wicklund

KG, et al: Pelvic inflammatory disease and the risk of ovarian

cancer and borderline ovarian tumors: A pooled analysis of 13

Case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 185:8–20. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

De Seta F, Banco R, Turrisi A, Airoud M,

De Leo R, Stabile G, Ceccarello M, Restaino S and De Santo D:

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) from Chlamydia trachomatis versus

PID from Neisseria gonorrhea: From clinical suspicion to therapy. G

Ital Dermatol Venereol. 147:423–430. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Barnard ME, Farland LV, Yan B, Wang J,

Trabert B, Doherty JA, Meeks HD, Madsen M, Guinto E, Collin LJ, et

al: Endometriosis typology and ovarian cancer risk. JAMA.

332:482–489. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim SY and Lee JR: Fertility preservation

option in young women with ovarian cancer. Future Oncol.

12:1695–1698. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lavoue V, Huchon C, Akladios C, Alfonsi P,

Bakrin N, Ballester M, Bendifallah S, Bolze PA, Bonnet F, Bourgin

C, et al: Management of epithelial cancer of the ovary, fallopian

tube, primary peritoneum. Long text of the joint French clinical

practice guidelines issued by FRANCOGYN, CNGOF, SFOG,

GINECO-ARCAGY, endorsed by INCa. (Part 2: Systemic, intraperitoneal

treatment, elderly patients, fertility preservation, follow-up). J

Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 48:379–386. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mangili G, Somigliana E, Giorgione V,

Martinelli F, Filippi F, Petrella MC, Candiani M and Peccatori F:

Fertility preservation in women with borderline ovarian tumours.

Cancer Treat Rev. 49:13–24. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tsonis O and Kopeika J: Fertility

preservation in patients with gynaecologic malignancy: Response to

ovarian stimulation and long-term outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol

Reprod Biol. 290:93–100. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Akel RA, Guo XM, Moravek MB, Confino R,

Smith KN, Lawson AK, Klock SC, Tanner Iii EJ and Pavone ME: Ovarian

stimulation is safe and effective for patients with gynecologic

cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 9:367–374. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, Kumar L and

Friedlander M: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum:

2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 155 (Suppl 1):S61–S85. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Alvarez M, Solé M, Devesa M, Fábregas R,

Boada M, Tur R, Coroleu B, Veiga A and Barri PN: Live birth using

vitrified-warmed oocytes in invasive ovarian cancer: Case report

and literature review. Reprod Biomed Online. 28:663–668. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mayeur A, Puy V, Windal V, Hesters L,

Gallot V, Benoit A, Grynberg M, Sonigo C and Frydman N: Live birth

rate after use of cryopreserved oocytes or embryos at the time of

cancer diagnosis in female survivors: A retrospective study of ten

years of experience. J Assist Reprod Genet. 38:1767–1775. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nitecki R, Clapp MA, Fu S, Lamiman K,

Melamed A, Brady PC, Kaimal A, Del Carmen MG, Woodard TL, Meyer LA,

et al: Outcomes of the first pregnancy after Fertility-sparing

surgery for Early-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol.

137:1109–1118. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ledermann JA, Matias-Guiu X, Amant F,

Concin N, Davidson B, Fotopoulou C, González-Martin A, Gourley C,

Leary A, Lorusso D, et al: ESGO-ESMO-ESP consensus conference

recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology

and early, advanced and recurrent disease. Ann Oncol. 35:248–266.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2024, . Ovarian

Cancer/Fallopian Tube Cancer/Primary Perit. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Backes FJ,

Bakkum-Gamez JN, Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A, Chen LM,

Chitiyo VC, Cristea M, et al: NCCN Guidelines® Insights:

Ovarian cancer, version 3.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 20:972–980.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bentivegna E, Gouy S, Maulard A, Pautier

P, Leary A, Colombo N and Morice P: Fertility-sparing surgery in

epithelial ovarian cancer: A systematic review of oncological

issues. Ann Oncol. 27:1994–2004. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zapardiel I, Cruz M, Diestro MD, Requena A

and Garcia-Velasco JA: Assisted reproductive techniques after

fertility-sparing treatments in gynaecological cancers. Hum Reprod

Update. 22:281–305. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tomao F, Di Pinto A, Sassu CM, Bardhi E,

Di Donato V, Muzii L, Petrella MC, Peccatori FA and Panici PB:

Fertility preservation in ovarian tumours. Ecancermedicalscience.

12:88520185PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Daraï E, Fauvet R, Uzan C, Gouy S,

Duvillard P and Morice P: Fertility and borderline ovarian tumor: A

systematic review of conservative management, risk of recurrence

and alternative options. Hum Reprod Update. 19:151–166. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Poulain M, Vandame J, Tran C, Koutchinsky

S, Pirtea P and Ayoubi JM: Fertility preservation in borderline

ovarian tumor patients and survivors. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig.

43:179–186. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Fortin A, Hazout A, Thoury A, Alvès K,

Bats AS, Dhainaut C and Madelenat P: Assistance médicale à la

procréation après traitement conservateur d'une tumeur de l'ovaire

invasive ou à la limite de la malignité Assisted reproductive

technologies after conservative management of borderline or

invasive ovarian tumours. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 33:488–4897. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zaami S, Melcarne R, Patrone R, Gullo G,

Negro F, Napoletano G, Monti M, Aceti V, Panarese A, Borcea MC, et

al: Oncofertility and reproductive counseling in patients with

breast cancer: A retrospective study. J Clin Med. 11:13112022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Rienzi L, Cobo A, Paffoni A, Scarduelli C,

Capalbo A, Vajta G, Remohí J, Ragni G and Ubaldi FM: Consistent and

predictable delivery rates after oocyte vitrification: An

observational longitudinal cohort multicentric study. Hum Reprod.

27:1606–1612. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

SHRE Guideline Group on Female Fertility

Preservation, . Anderson RA, Amant F, Braat D, D'Angelo A, Chuva de

Sousa Lopes SM, Demeestere I, Dwek S, Frith L, Lambertini M, et al:

ESHRE guideline: Female fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Open.

2020:hoaa0522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gullo G, Perino A and Cucinella G: Open vs

closed vitrification system: Which one is safer? Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 26:1065–1067. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Peccatori FA, Mangili G, Bergamini A,

Filippi F, Martinelli F, Ferrari F, Noli S, Rabaiotti E, Candiani M

and Somigliana E: Fertility preservation in women harboring

deleterious BRCA mutations: Ready for prime time? Hum Reprod.

33:181–187. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gullo G, Basile G, Cucinella G, Greco ME,

Perino A, Chiantera V and Marinelli S: Fresh vs. frozen embryo

transfer in assisted reproductive techniques: A single center

retrospective cohort study and Ethical-legal implications. Eur Rev

Med Pharmacol Sci. 27:6809–6823. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Park CW, Lee SH, Yang KM, Lee IH, Lim KT,

Lee KH and Kim TJ: Cryopreservation of in vitro matured oocytes

after ex vivo oocyte retrieval from gynecologic cancer patients

undergoing radical surgery. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 43:119–125. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ponce J, Fernandez-Gonzalez S, Calvo I,

Climent M, Peñafiel J, Feliubadaló L, Teulé A, Lázaro C, Brunet JM,

Candás-Estébanez B and Durán Retamal M: Assessment of ovarian

reserve and reproductive outcomes in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation

carriers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 30:83–88. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Oktay K, Kim JY, Barad D and Babayev SN:

Association of BRCA1 mutations with occult primary ovarian

insufficiency: A possible explanation for the link between

infertility and breast/ovarian cancer risks. J Clin Oncol.

28:240–204. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Oktay K, Turan V, Titus S, Stobezki R and

Liu L: BRCA mutations, DNA repair deficiency, and ovarian aging.

Biol Reprod. 93:672015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang ET, Pisarska MD, Bresee C, Chen YD,

Lester J, Afshar Y, Alexander C and Karlan BY: BRCA1 germline

mutations may be associated with reduced ovarian reserve. Fertil

Steril. 102:1723–1728. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kufel-Grabowska J, Podolak A, Maliszewski

D, Bartoszkiewicz M, Ramlau R and Lukaszuk K: Fertility counseling

in BRCA1/2-mutated women with breast cancer and healthy

individuals. J Clin Med. 11:39962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Marklund A, Lekberg T, Hedayati E,

Liljegren A, Bergh J, Lundberg FE and Rodriguez-Wallberg KA:

Relapse rates and Disease-specific mortality following procedures

for fertility preservation at time of breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA

Oncol. 8:1438–1446. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kim J, Turan V and Oktay K: Long-term

safety of letrozole and gonadotropin stimulation for fertility

preservation in women with breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

101:1364–1371. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Oktay K, Buyuk E, Libertella N, Akar M and

Rosenwaks Z: Fertility preservation in breast cancer patients: A

prospective controlled comparison of ovarian stimulation with

tamoxifen and letrozole for embryo cryopreservation. J Clin Oncol.

23:4347–4353. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Dias Nunes J, Demeestere I and Devos M:

BRCA mutations and fertility preservation. Int J Mol Sci.

25:2042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tomao F, Peccatori F, Del Pup L, Franchi

D, Zanagnolo V, Panici PB and Colombo N: Special issues in

fertility preservation for gynecologic malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 97:206–219. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Martinez A, Poilblanc M, Ferron G, De

Cuypere M, Jouve E and Querleu D: Fertility-preserving surgical

procedures, techniques. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

26:407–424. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bruno M, Ludovisi M, Ronsini C, Capanna G,

Stabile G and Guido M: Tertiary cytoreduction for isolated

lymphnode recurrence (ILNR) ovarian cancer in a BRCA2 mutated

patient: Our experience and prevalence of BRCA 1 or 2 genes

mutational status in ILNR. Medicina (Kaunas). 59:6062023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Restaino S, Finelli A, Pellecchia G,

Biasioli A, Mauro J, Ronsini C, Martina MD, Arcieri M, Della Corte

L, Sorrentino F, et al: Scar-free laparoscopy in BRCA-mutated

women. Medicina (Kaunas). 58:9432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Madero S, Rodriguez A, Vassena R and

Vernaeve V: Endometrial preparation: Effect of estrogen dose and

administration route on reproductive outcomes in oocyte donation

cycles with fresh embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 31:1755–1764. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL and Ray JG:

Clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia determined in early

pregnancy: Systematic review and Meta-analysis of large cohort

studies. BMJ. 353:i17532016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|